Abstract

Rhizostomeae (Scyphozoa) jellyfishes are widespread in neritic waters and include species of commercial importance in Asia. This group comprises jellyfish taxa that host endosymbiotic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae, which provide autotrophic benefits. Despite their value, limited molecular data for Japanese rhizostome taxa has hinder accurate taxonomic classification and interpretation of novel traits. This study combines molecular methods to provide the most complete understanding of molecular phylogenetic relations of Rhizostomeae jellyfishes while assessing the number of Symbiodiniaceae taxa that can be hosted in each species at the medusa level through a new method developed herein for tandem amplification of symbionts and host, validated with microscopy. We also evaluate which rhizostomes produce cassiosomes and whether Symbiodiniaceae are found in the core. Phylogenetic analysis of host mitochondrial (16S rRNA, COI) and nuclear (28S) gene regions of 18 medusae from five genera revealed: (1) Mastigias in Japanese waters corresponds to M. albipunctata; (2) Cassiopea from Kagoshima likely represents an undescribed species, though Cassiopea xamachana may have been introduced; (3) Two cepheid species - Cephea cephea and Netrostoma setouchianum - occur in Japan; (4) Rhopilema esculentum, a commonly harvested species, is endemic to western Japan. Symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 analysis identified three dominant genera (Symbiodinium, Cladocopium, and Durusdinium). More than one genus among these was found to be hosted in samples of the genera Mastigias and Cassiopea, indicating plasticity in symbiont association at both the taxon and individual medusa level. Microscopy confirmed cassiosome production exclusively in species examined of the suborder Kolpophorae: Cassiopea sp., N. setouchianum, and M. albipunctata, though absent in a juvenile M. albipunctata sample. Conversely, R. esculentum hosts Symbiodiniaceae but appears to lack the ability to produce cassiosomes. Overall, findings support the distinctive evolution of Symbiodiniaceae–Rhizostomeae symbiosis, the monophyly of the suborder Kolpophorae, and the synapomorphy of cassiosome production in Kolpophorae with onset likely influenced by developmental stage. Broader taxon sampling, especially within Dactyliophorae, will provide further clues on the functional evolution and cellular organization underlying photoendosymbiosis and cassiosome production in these medusozoans.

1 Introduction

Jellyfishes are generally considered nuisance marine organisms due to their reputation for causing sudden blooms and stings. However, jellyfishes of the order Rhizostomeae Cuvier, 1800 (Cnidaria; Scyphozoa) are also of commercial importance, particularly in China and Southeast Asia (Omori, 1982; Kingsford et al., 2000; Hsieh et al., 2001; Omori and Nakano, 2001). Out of the 91 species of rhizostomes (Jarms and Morandini, 2023; Collins et al., 2025) approximately 24 species are edible (Brotz, 2016), with Rhopilema esculentum, Kishinouye, 1891, Rhopilema hispidum (Vanhöffen, 1888) and Stomolophus meleagrisAgassiz, 1860 being the most consumed worldwide (Hsieh et al., 2001; Omori and Nakano, 2001; Raposo et al., 2022). Additionally, rhizostomes are well noted among the species that cause jellyfish blooms (Fernández-Alías et al., 2020) with Nemopilema nomuraiKishinouye, 1922 being the largest among them weighing up to 200 kg (Uye, 2008; Kitamura and Omori, 2010). Species of this order of jellyfish have significant ecological and economic roles, some beneficial and some detrimental, in recreation, fisheries, and aquaculture (Daryanabard and Dawson, 2008; Uye, 2008; Purcell, 2012; Falkenhaug, 2014; Fernández-Alías et al., 2020; Syazwan et al., 2020). As such, a deeper understanding is needed of rhizostome novel adaptive mechanisms and functional evolution, such as photoendosymbiosis and cassiosome production causing stinging water syndrome, amidst the backdrop of changing marine ecosystems for sustainable coastal management.

Rhizostomeae medusae (jellyfishes), in contrast to typical jellyfishes, are characterized by the lack of marginal tentacles and the presence of eight branched, frilly oral arms, and typically inhabit tropical to subtropical waters, although temperate species also exist. Symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae taxa has been reported in two species of the order Coronatae and 11 Scyphozoa genera, primarily of the order Rhizostomeae, particularly of the suborder Kolpophorae (Djeghri et al., 2019; Nitschke et al., 2022) making the order the best model in which to study jellyfish-algae (protist) coevolution. Rhizostomeae has been divided into two suborders Kolpophorae and Dactyliophorae based mainly on medusa morphological differences (Stiasny, 1921; Kramp, 1961). Molecular analyses later confirmed the monophyly of Kolpophorae but not Dactyliophorae, which is often recovered as paraphyletic or unresolved (Bayha et al., 2010; Helm, 2018; Tan et al., 2024). Molecular sequences of Rhizostomeae species are disproportionately represented in NCBI GenBank, with the fishery and aquaculture targets, such as R. hispidum and the model species for jellyfish endosymbiosis, Cassiopea xamachanaBigelow, 1892 (Ohdera et al., 2018; Medina et al., 2021) best represented. Some species, especially taxa from Japan, have few to no reference sequences in the public domain. It is estimated that nine genera inhabit Japanese waters (Jarms and Morandini, 2023), and of them five are typically exhibited in public aquariums drawing large crowds due to their unique appearance and rhythmic pulsing behavior. In addition to these morphological distinctions, Rhizostomeae taxa have also evolved the capability to host endosymbiotic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae (formerly zooxanthellae) (LaJeunesse et al., 2018; Djeghri et al., 2019; Nitschke et al., 2022) acquired horizontally from the environment. Cnidarian coevolution with these dinoflagellates, traditionally dubbed “Symbiodinium” or “Zooxanthellae” (Djeghri et al., 2019), is well-studied in anthozoan counterparts, such as corals and some anemones but remains poorly understood in jellyfishes beyond the model rhizostome C. xamachana. Some studies suggest that the endosymbiotic relationship emerged within the suborder Kolpophorae exclusively, but molecular phylogenetic findings are unresolved on the monophyly of each of the suborders Kolpophorae and Dactyliophorae (Bayha et al., 2010).

Initially, “zooxanthellae” were classified into Symbiodinium clades A to G based on the results of molecular analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 2 region (LaJeunesse, 2001). Later, additional analysis of ITS and morphological traits for all clades revealed the presence of 15 separate genera within the thereafter established family Symbiodiniaceae (LaJeunesse et al., 2018, 2022; Nitschke et al., 2020, 2022; Davies et al., 2023). Among these, five genera — Symbiodinium, Durusdinium, Breviolum, Cladocopium, and Philozoon — are endosymbiotic with rhizostome jellyfish taxa (Muscatine et al., 1986; Santos et al., 2002; LaJeunesse et al., 2018, 2022; Dall’Olio et al., 2022; Enrique-Navarro et al., 2022). Rhizostomes are known to acquire nutritional benefits from these photosynthetic endosymbionts, and in some species, symbiont uptake during the asexual polyp stage can trigger or enhance strobilation (Sugiura, 1964; Ohdera et al., 2018). In C. xamachana, Mastigias papua (Lesson, 1830) and Cotylorhiza tuberculata (Macri, 1778), this uptake is required to initiate metamorphosis (Sugiura, 1964; Kikinger, 1992; Ohdera et al., 2018), whereas in Cephea cephea (Forskål, 1775) it appears to enhance but not determine strobilation (Sugiura, 1969). However, studies have primarily focus on the model C. xamachana; demonstrating plasticity in Symbiodiniaceae uptake by polyps (Thornhill et al., 2006; Newkirk et al., 2020; Sharp et al., 2024);. However, the mechanisms of host recognition and symbiont selection, or the relevance of these factors on their reciprocal durability and ultimate survival, remain largely unexplored.

Some jellyfishes are known to produce mucus, but the function and constituents are little studied (reviewed in Camacho-Pacheco et al., 2022), despite its potential importance on the ecosystem’s C:N nutrient exchange and carbon cycle (Jufri, 2019; Savoca et al., 2022). Mucus emitted by rhizostomes may aid in defense and predation if it contains cassiosomes—autonomous structures that function as ‘mucus grenades’ that were first found in the mucus of C. xamachana and in four other rhizostome genera (Ames et al., 2020). The discovery of cassiosomes resolved the long-held mystery behind the phenomenon of “stinging water” in which bathers experience envenomation on exposed skin despite having no direct contact with a jellyfish (Muffett et al., 2021). The ability to cause stinging water, also called “contactless stings” appears to be unique to Rhizostomeae, as it has not been reported in other scyphozoans, including the sister suborder Semaeostomeae which includes Aurelia aurita (moon jellyfish) (Muffett et al., 2021).

Like many jellyfish species over time, Rhizostomeae taxa in Japan have undergone taxonomic revisions since their original descriptions: Netrostoma setouchianum (Kishinouye, 1902), Rhopilema esculentum, Mastigias papua, Cephea cephea (Supplementary Table S1). Uchida’s, 1954 checklist includes nine rhizostome genera present in Japan and its adjacent waters. However, it was not until the early 2000s that Cassiopea was documented in the warm straits of Japan in the south of Kagoshima (Namikawa and Soyama, 2000) and in Sukumo Bay, Shikoku, Western Japan (Toshino, 2018). Despite the persistence of impressive jellyfish exhibits of Rhizostomeae species at public aquariums, comprehensive molecular phylogenetics studies to uncover the coevolutionary history of Symbiodiniaceae associations are few for Japanese species.

This study focuses on Rhizostomeae genera found in Japanese waters, employing a complementary molecular and microscopy approach to validate: (1) Species-level identifications of rhizostome jellyfish collected for display in public aquariums; (2) Genus-level identifications of respective dominant Symbiodiniaceae endosymbionts; and (3) Validation of cassiosome production capability of species in each rhizostome suborder. Overall, our novel approach of concurrent amplification of gene targets of both the host and symbiont yielded findings that provide a baseline reconstruction of Rhizostomeae-Symbiodiniaceae coevolution, support the monophyly of Kolpophorae but not Dactyliophorae, and corroborate the emergence of cassiosomes in Kolpophorae as a novel Cnidaria defense mechanism for mixotrophic jellyfishes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

Samples for this study were obtained via either aquarium stock or collection from the wild. Due to the seasonal and often unpredictable availability of Rhizostomeae jellyfish in the wild, specimens were sourced through collaboration with public aquariums. Some samples, particularly those labelled as from “Kamo Aquarium,” were reared in aquarium tanks from wild-collected stock, while others were collected from the wild shortly before shipment (e.g. from Kagoshima, Amami, Nagasaki). Original collection localities, when known, are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1

| Species | Accession | Origin | Specimen ID | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | COI | 28S | |||

| Cassiopea sp. | OR702596 | OR701841 | PP352698 | Kamo Aquarium | KMC1 |

| Cassiopea sp. | OR702601 | Kamo Aquarium | KMC2 | ||

| Cassiopea sp. | OR702608 | PP352693 | Chosuiro,Yojiro, Kagoshima, Japan | KSC1 | |

| Cassiopea sp. | OR702605 | OR701846 | PP352692 | Chosuiro,Yojiro, Kagoshima, Japan | KSC2 |

| Cassiopea sp. | OR702606 | OR701845 | PP352691 | Chosuiro,Yojiro, Kagoshima, Japan | SCS |

| Cassiopea sp. | PV534090 | PV539585 | PV536777 | Amami, Kagoshima, Japan | KSC6 |

| Cassiopea sp. | PV534091 | PV539586 | PV536778 | Amami, Kagoshima, Japan | KSC7 |

| Mastigias albipunctata | OR702597 | OR701843 | PP352700 | Chosuiro,Yojiro, Kagoshima, Japan | SMP |

| Mastigias albipunctata | OR702598 | OR701844 | PP352697 | Chosuiro,Yojiro, Kagoshima, Japan | KMP |

| Mastigias albipunctata | OR702602 | OR701842 | PP352696 | Kamo Aquarium | KMPA |

| Mastigias albipunctata | PV534092 | PV539587 | PV536779 | Nonogushi Port, Nagasaki, Japan | NSM1 |

| Rhopilema esculentum | OR702599 | PP411204 | PP352695 | Kamo Aquarium | KRE7 |

| Rhopilema esculentum | OR702604 | OR698877 | PP352694 | Kamo Aquarium | KREA |

| Netrostoma setouchianum | OR702603 | Kamo Aquarium | KNS | ||

| Netrostoma setouchianum | PP421577 | Kamo Aquarium | KNS2 | ||

| Cephea cephea | OR702600 | PP352699 | Kamo Aquarium | KCCA | |

| Cephea cephea | OR702607 | Kamo Aquarium | KCCB | ||

GenBank accession numbers corresponding to sequences generated in this study.

The “origin” of samples reared in an aquarium environment before tissue subsampling was conducted for this study is stated as the aquarium name.

At Kamo Aquarium (Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture) two on-site sample collections occurred and, additionally, live medusae were shipped to Tohoku University from both Kamo Aquarium and Kagoshima City Aquarium (Kagoshima Prefecture) (details provided in Supplementary Table S2). The first collection on October 17, 2021, included Mastigias albipunctataStiasny, 1920, Rhopilema esculentum, and Cassiopea sp. medusae. The second collection on October 11, 2022, included M. albipunctata, Netrostoma setouchianum, R. esculentum medusae, and Cephea cephea polyps. For medusae, umbrella diameters were measured, and then jellyfish tissue subsampled from the oral arms and exumbrella was preserved in 1.5 ml Lobind Eppendorf tubes containing either 99.5% ethanol for molecular analysis or 5-8% formalin solution for morphological study (Supplementary Table S2). Tissue samples were returned in an insulated cooler to the Laboratory of International Marine Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University (IMS). Ethanol samples were frozen at -30°C until DNA was extracted, while formalin specimens were kept at room temperature.

Live medusae of Cassiopea sp. and M. albipunctata collected by Kagoshima City Aquarium staff in Yojiro, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima Prefecture were shipped in sealed bags by courier to the IMS Aquaroom on July 10, 2022, June 28, 2024 and October 19, 2024. Separately, two Cassiopea sp. medusae collected at Amami Oshima, the largest island in the Amami archipelago, collected on June 24, 2024 were also shipped live to the IMS facility. Additional live shipments from Kamo Aquarium included two live medusae each of M. albipunctata, N. setouchianum, and R. esculentum species from aquarium cultures on July 5, 2023, and three live M. albipunctata specimens collected from Nagasaki on August 24, 2024. Samples from a total of 28 medusae and 2 polyps across five genera were obtained for this study of which 18 samples were used for molecular barcoding (refer to Table 1; Supplementary Table S2 for a list of individuals and subsampled tissues used in molecular analysis).

2.2 DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and quantified with a either a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA or Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, USA) using the reagent for high sensitivity double stranded DNA assays. A ~550 bp fragment of the mitochondrial ribosomal 16S rRNA gene (Lawley et al., 2016), ~650 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (Geller et al., 2013), and a 550–600 bp fragment of the nuclear ribosomal 28S gene region (Chombard et al., 1997) of the jellyfish were amplified using either a BentoLab portable thermal cycler (BentoLab, UK, London) or Veriti 96-well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan). Each 50 μL reaction contained 25 μL Ex Taq DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) 10 μL template DNA, 11 μL nuclease free water, and 2 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM). DNA extracted from rhizostome jellyfish was also used to amplify the Symbiodiniaceae-specific internal transcribed spacer 2 region (Hume et al., 2018) using the same reagents in 10 μL reaction volumes (5 μL Ex Taq mix, 1.5 μL template, 2.7 μL water, 0.4 μL each primer). Details of primer sequences and cycling conditions are provided in Supplementary Figure S1. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel and purified with ExoSap-IT PCR Product Cleanup kit (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan) or AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Sanger sequencing was carried out on-site at Onagawa Field Centre (Tohoku University) or outsourced at Eurofins Genomics K.K. (Tokyo, Japan).

2.3 Phylogenetic reconstruction

Nucleotide sequences obtained were manually checked and edited in 4Peaks (Griekspoor and Groothuis, 2006). Consensus sequences were generated using Seaview5 (Gouy et al., 2021) and sequence similarity with previously published rhizostome species was confirmed using BLASTn (Altschul et al., 1990). The new sequences were deposited into GenBank (see Table 1 for list of accession numbers). Additional 16S, COI and 28S Rhizostomeae sequences and outgroups from the sister order Semaeostomeae were acquired from NCBI GenBank (accessed June 2024, Supplementary Tables S3, S4, S5). For Symbiodiniaceae tree construction, the ITS2 dataset for phylogenetic analysis included 69 sequences (20 new sequences from this study and 49 sequences from GenBank) for the genera Symbiodinium, Philozoon, Breviolum, Cladocopium, Durusdinium, Effrenium, Fugacium, Freudenthalidium, and clade H. The sequences selected include Symbiodiniaceae type species (LaJeunesse et al., 2018; Pochon and LaJeunesse, 2021), sequences from Dall’Olio et al., 2022 and most similar sequences from BLASTn (see Supplementary Table S6). Polarella glacialis (JN558110) a free-living cold-adapted dinoflagellate of the Suessiaceae family was used as the outgroup as, like Symbiodiniaceae, it belongs to the order Suessiales.

Sequences were aligned using the G-INS-i algorithm in MAFFT (ver. 7.520, https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/; (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Alignments were trimmed at selected regions based on options for a less stringent selection using Gblocks in Seaview5, which were used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree. The substitution models were selected for low AIC scores from Model selection in IQ-TREE (16S: TMI2+F+G+I, COI: GTR+F+I+G4, 28S: TIM3+F+I+G4, Symbiodiniaceae ITS2: GTR+F+G4) (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were reconstructed in IQ-TREE (Trifinopoulos et al., 2016) with support assessed using Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH)-aLRT and ultrafast bootstrapping (Hoang et al., 2018), with 1000 replicates. Trees were visualized and edited in FigTree v1.4.4 (Rambaut, 2018) or iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2024), and Inkscape software (https://inkscape.org/release/inkscape-0.92.4/). Mean evolutionary divergence between major clades of Cassiopea, Mastigias and Cepheidae for the 16S rRNA dataset were estimated in MEGA 11 (Stecher et al., 2020; Tamura et al., 2021) using the Jukes-Cantor (Jukes and Cantor, 1969) substitution model with uniform rates and 1,000 bootstraps replicates. All ambiguous positions were removed by the pairwise-deletion option.

During 28S region amplification of rhizostome jellyfish samples, gel electrophoresis consistently produced double bands, one at approximately 550 bp and the other at 250 bp (Supplementary Figure S2). To rule-out possible contamination issues and to validate the 28S region of symbionts for phylogenetic analysis, sets of double bands were excised separately and in-gel extractions were conducted for each using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). Resulting sequences (methods above) from the shorter amplicons were validated through BLASTn against the GenBank nucleotide database as belonging to Symbiodiniaceae taxa. Subsequently, a 28S Symbiodiniaceae maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using 64 sequences (11 partial sequences from this study, 53 from GenBank; see Supplementary Table S7) comprising Symbiodinium, Philozoon, Breviolum, Cladocopium, Durusdinium, and other clades, with P. glacialis as the outgroup.

2.4 Morphological analyses

To detect the presence of cassiosomes in different taxa during the second on-site collection event at Kamo Aquarium, live medusae were gently agitated separately in beakers for 5 minutes. Subsequently, mucus from each medusa was collected and observed under a LEICA5 stereo microscope, (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at magnification up to 4X. Cassiosomes, when present, were isolated from the mucus and examined at higher magnification, and videos and photos were taken at scale. The appendages of the jellyfish were also examined for the presence of vesicular appendages, the structures wherein cassiosome production occurs and which bear distinct “cassiosome nests” (Ames et al., 2020). Specimens preserved in 5–8% formalin were observed under phase contrast at 10×, 20×, and 100× (oil immersion) objective lens magnification of a Nikon Eclipse Ni-U upright light microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to confirm the presence or absence of endosymbiotic Symbiodiniaceae.

3 Results

3.1 Genus-specific findings

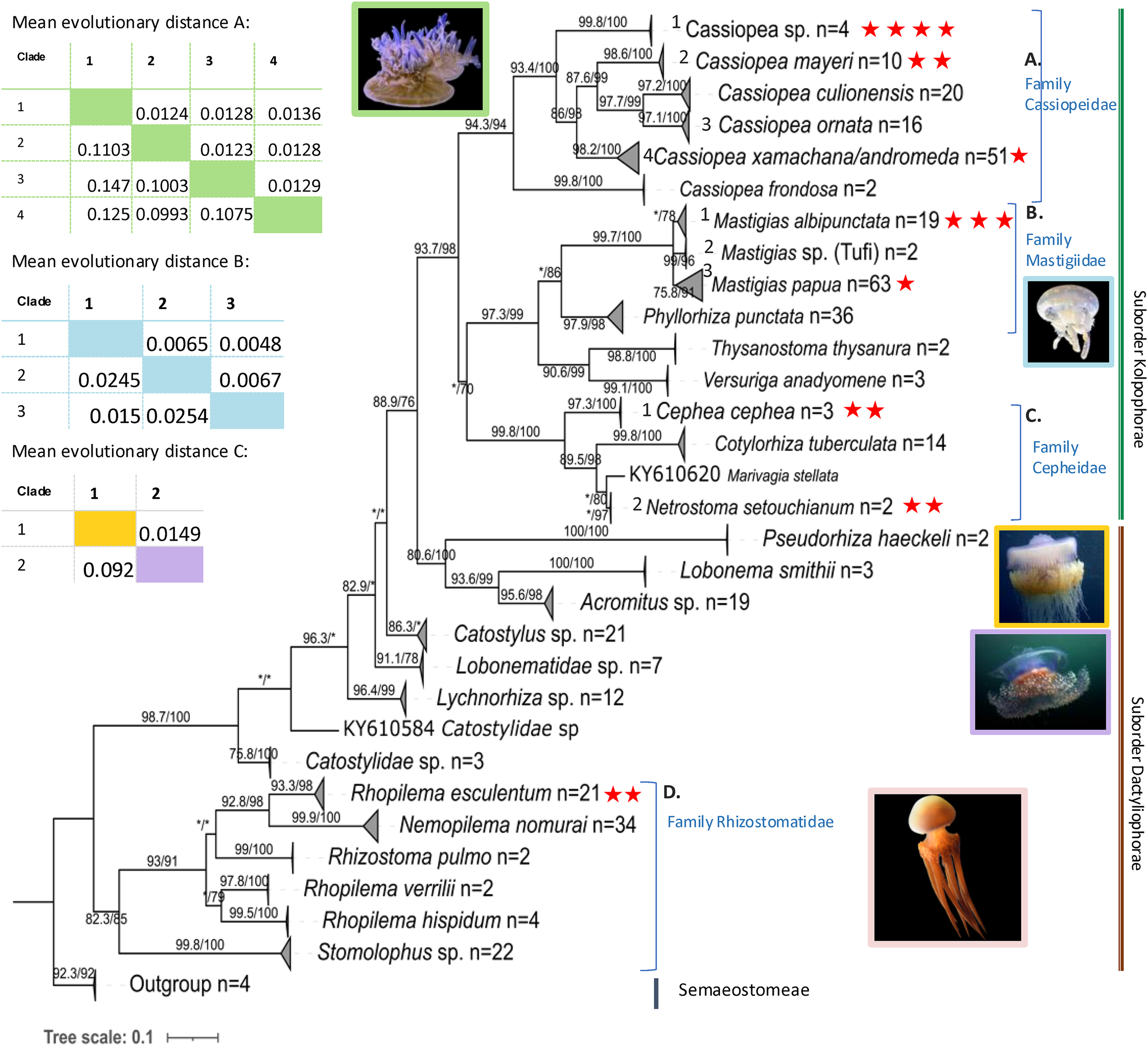

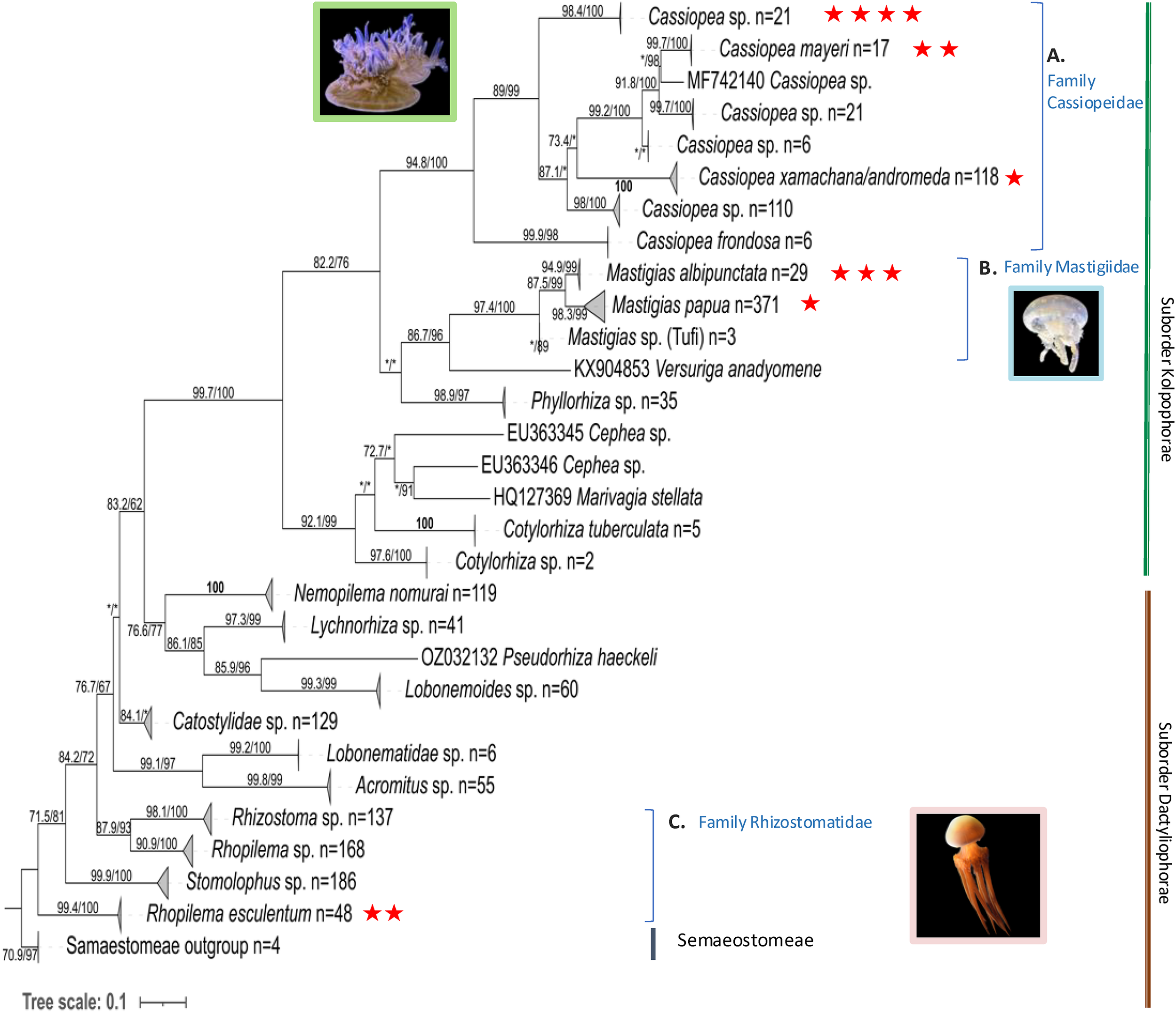

Phylogenetic analyses on both 16S (Figure 1) and COI (Figure 2) markers provide strong support for the monophyly of the suborder Kolpophorae emerging from within Dactyliophorae, with 16S showing 93.7% SH-aLRT and 98% bootstrap support and COI showing 99.7% SH-aLRT and 100% bootstrap support. All analyzed sequences of Cassiopea sp., Mastigias albipunctata, Rhopilema esculentum and Cephea cephea clustered with their corresponding clade in the tree reconstructed with GenBank sequences.

Figure 1

Maximum likelihood 16S rRNA tree with SH-aLRT support/ultrafast bootstrap support (%) using IQtree (TIM2+F+I+G). Tree reconstructed using samples sequenced in this study (red stars, n = 17) with additional sequences from NCBI GenBank, n = 384) and outgroups from the sister order Semaeostomeae (n=4) (see Supplementary Table S3 for accession numbers). Clades were collapsed, and number of sequences per clade given after n=. Asterisk (*) represents under 70 (aLRT and bootstrap) support. The accompanying tables show the estimates of evolutionary divergence over sequence pairs between groups (number of base substitutions per site from averaging over all sequence pairs between groups and standard error estimate(s) above the diagonal) calculated in MEGA 11. Photo sources: Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima, Mastigias albipunctata and Rhopilema esculentum photographed by coauthors at Kamo Aquarium (Tsuruoka, Japan in 2022), Netrostoma setouchianum photographed by Hiroyuki Ozawa 2022 from a seagrass bed (Okinawa 2022), Cephea cephea by CORDENOS Thierry, 2020 (photos under CC-BY-NC licenses) as a ‘Research Grade’ assigned taxon by iNaturalist (inaturalist.org accessed on 4 February 2024).

Figure 2

Maximum likelihood COI tree with SH-aLRT support/ultrafast bootstrap support (%) using IQtree (GTR+F+I+G). Tree reconstructed using samples sequenced in this study (red stars, n = 13) with additional sequences from NCBI GenBank, n = 1791) and outgroups from Semaeostomeae (n=4) (accession numbers in Supplementary Table S4). Clades were collapsed and number of sequences per clade given after n=. Asterisk (*) represents under 70 (aLRT and bootstrap) support. COI for Cepheidae samples is not available, as amplification was unsuccessful. Photo sources: Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima, Mastigias albipunctata and Rhopilema esculentum photographed by coauthors at Kamo Aquarium (Tsuruoka, Japan in 2022).

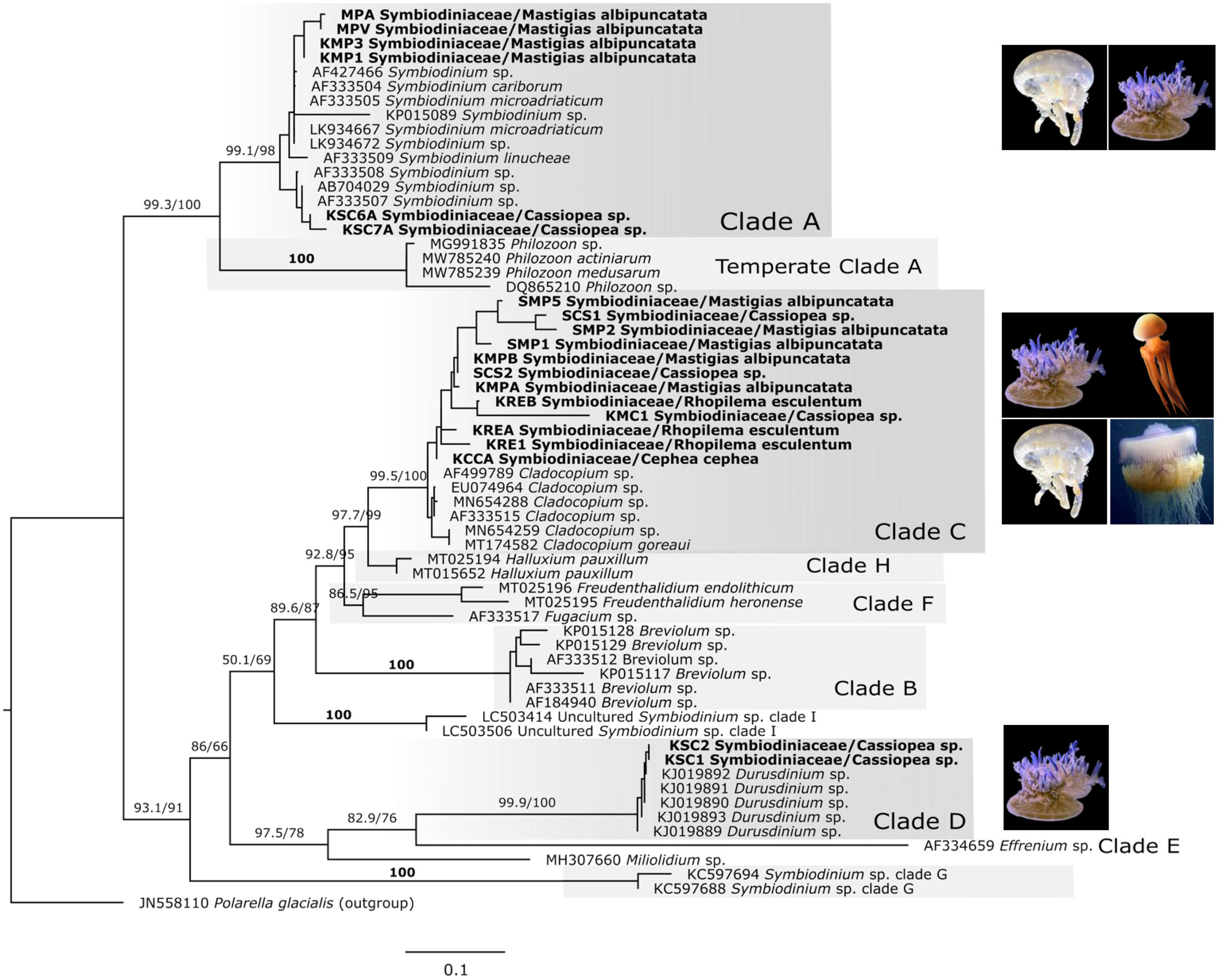

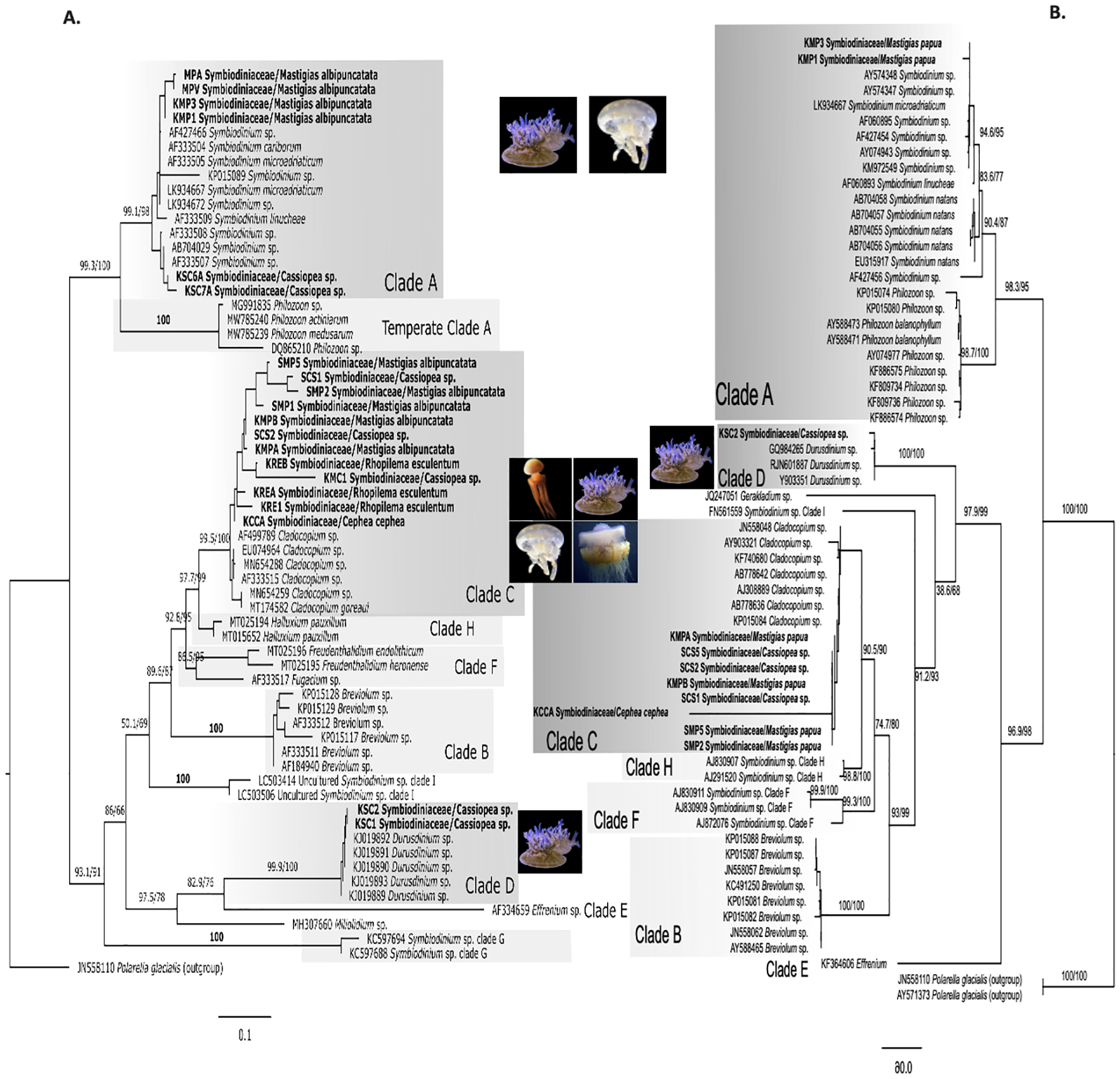

Phylogenetic analysis of the ITS2 region (Figure 3) revealed that individual medusae of the same species sometimes harbored a different dominant Symbiodiniaceae genus: Cladocopium was detected in C. cephea, R. esculentum, M. albipunctata and Cassiopea sp., Symbiodinium was associated with both M. albipunctata and Cassiopea sp., while Durusdinium was found exclusively in Cassiopea sp. Microscopy of host tissues revealed subcellular Symbiodiniaceae, thereby supporting molecular findings suggesting all rhizostome taxa studied herein host these endosymbionts.

Figure 3

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Symbiodiniaceae based on specific ITS2 gene region, including dinoflagellate sequences amplified from rhizostome jellyfishes in this study (n = 20) and from NCBI GenBank (n = 49). Polarella glacialis is used as outgroup (n=1) (accession numbers in Supplementary Table S6). Bold labels are samples from this study. GTR+F+G model was used, and numbers represent SH-aLRT/Ultrafast bootstrap support (%). Clade names (A–E) indicate those previously assigned to Symbiodinium. Photo sources: Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima, Mastigias albipunctata and Rhopilema esculentum photographed by coauthors at Kamo Aquarium (Tsuruoka, Japan in 2022), Netrostoma setouchianum photographed by Hiroyuki Ozawa 2022 from a seagrass bed (Okinawa 2022), Cephea cephea by CORDENOS Thierry, 2020 (photos under CC-BY-NC licenses) as a ‘Research Grade’ assigned taxon by iNaturalist (inaturalist.org accessed on 4 February 2024).

3.1.1 Cassiopeidae

The rhizostome 16S phylogenetic tree (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S3) places Cassiopea samples from this study into three separate clades sister to Cassiopea frondosa (Panama) – comprising the family Cassiopeidae. Four of our Cassiopea samples from Kagoshima form a well-supported clade (SH-aLRT: 99.8%, bootstrap: 100%) that is sister to a clade comprising Cassiopea mayeri (Philippines and Okinawa), Cassioepa culionensis (Philippines), and Cassiopea ornata (Guam, Singapore and Palau). Furthermore, Amami Oshima Cassiopea samples (PV534090, PV534091) cluster with C. mayeri. Unexpectedly, one sample that was collected from Kagoshima but reared in Kamo Aquarium (OR702605) clustered with sequences labelled Cassiopea xamachana and/or Cassiopea andromeda (Florida Keys and Mexico) suggesting possible introduction to Japan from its typical habitat in the Southeast Atlantic Ocean. The mean divergence between the clade comprising uniquely Kagoshima main island Cassiopea samples (n = 4) and the other clades were estimated as follows: 0.1075 (S.E. 0.0129) between the C. xamachana/andromeda clade, 0.1227 (S.E. 0.0136) between C. ornata clade, and 0.1003 (S.E. 0.0124) between the C. mayeri clade. Similarly, COI (Figure 2) and 28S trees (Supplementary Figure S4), both indicate the Kagoshima wild-caught Cassiopea is a unique yet unidentified species. Mean COI divergence was not calculated because public datasets contain inconsistently labeled entries and unresolved lineages, and individual COI clades cannot be confidently assigned to specific species; such comparisons could therefore overstate or misrepresent relationships.

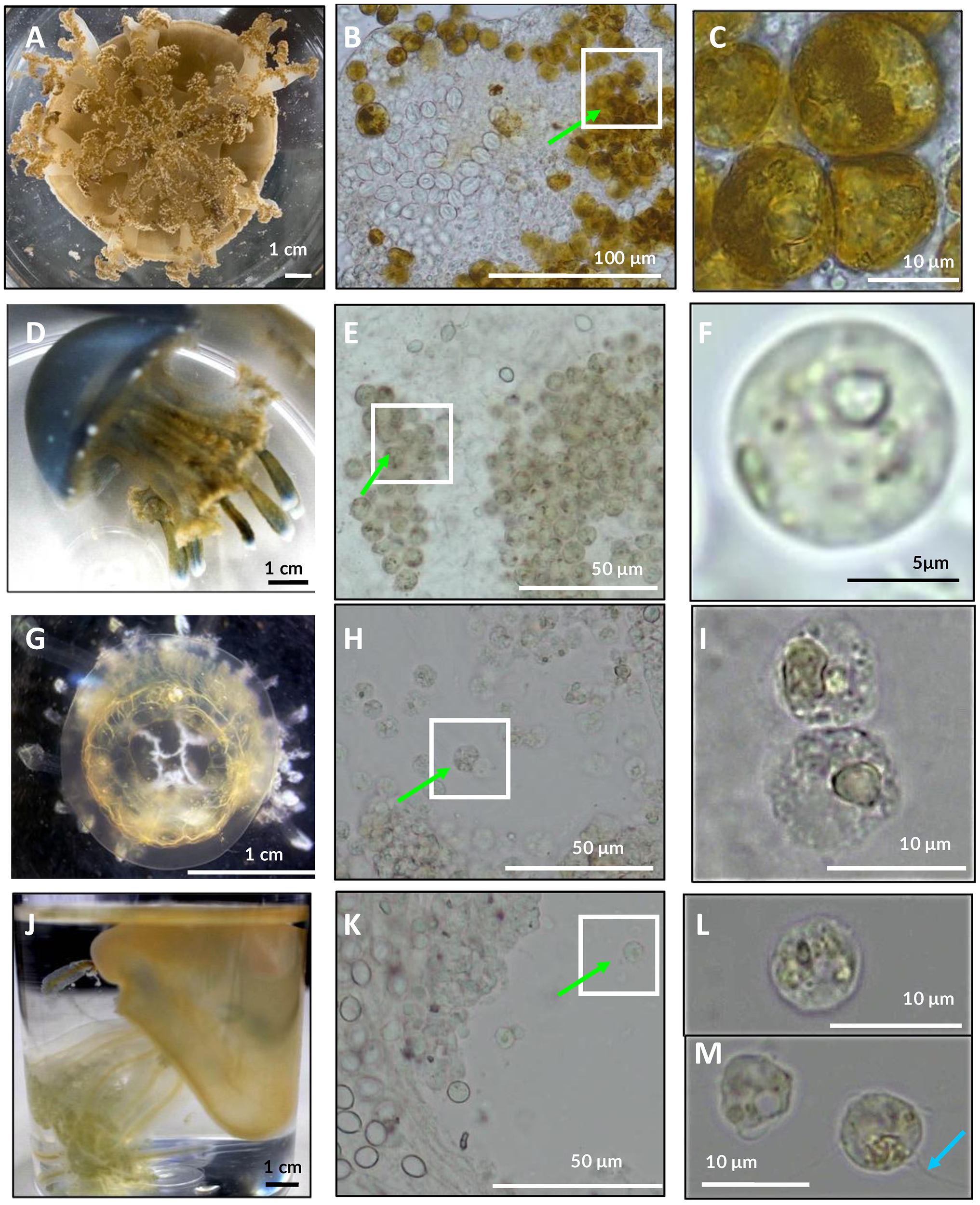

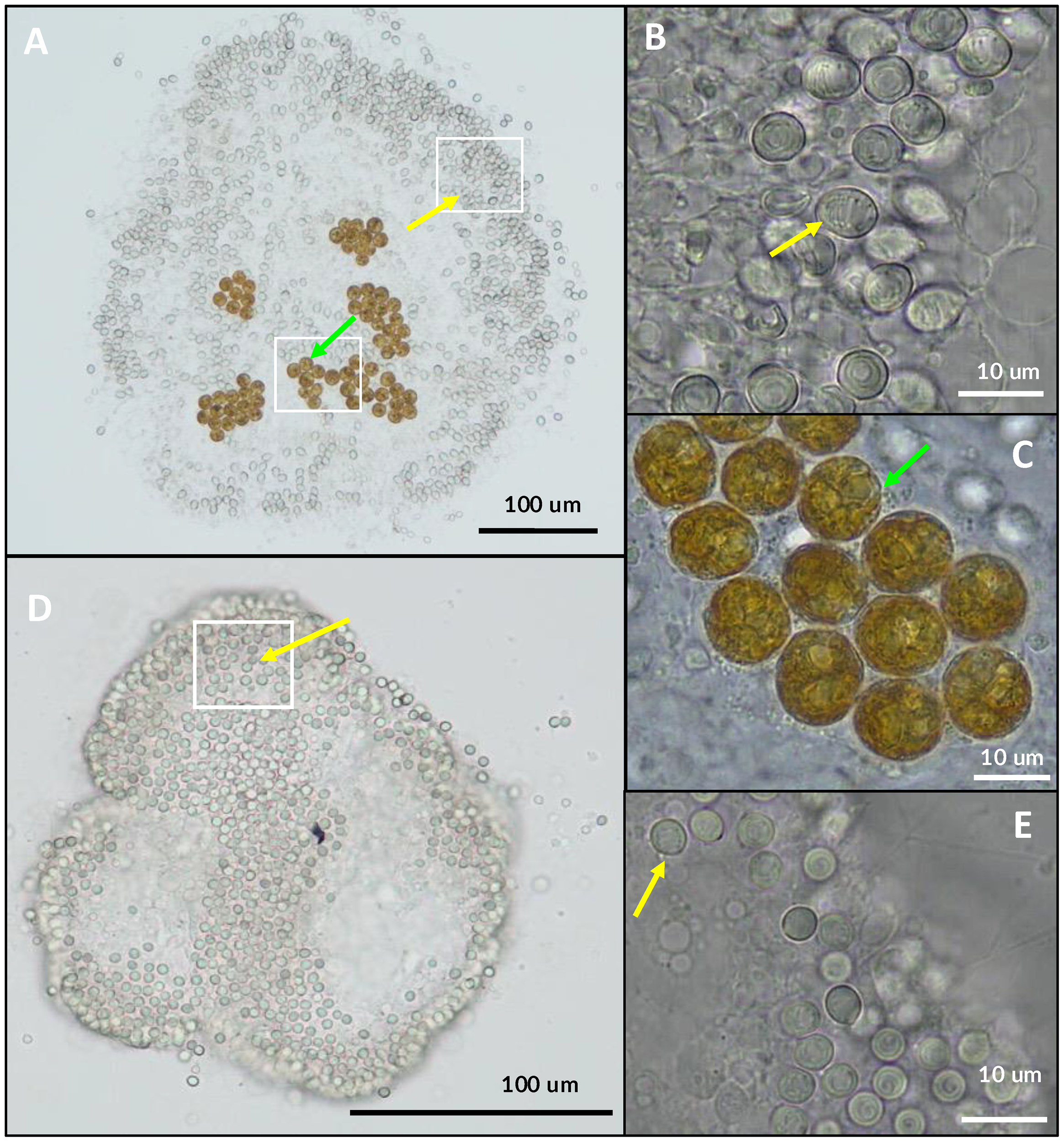

Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 ML phylogenetic analyses (Figure 3) revealed the presence of one of three taxa, Symbiodinium, Cladocopium and Durusdinium, as dominant within either the oral arms or umbrella tissue of each of the Cassiopea samples. Accordingly, formalin-preserved tissue samples of Cassiopea sp. from Kagoshima examined with light microscopy (Figures 4A–C) revealed densely packed darkly pigmented coccoid Symbiodiniaceae with an average diameter of 15.1 µm (Table 2).

Figure 4

Examination of tissue types of several rhizostome jellyfishes under light microscope (B, C, E, F, H, I, K–M). Presence of Symbiodiniaceae coccoid cells (green arrows) observed in all taxa examined herein (n=4). (A–C)Cassiopea sp. live medusae from Kamo aquarium observed under light microscopy (A). (D–F)Mastigias albipunctata, live immature medusae from Kamo aquarium (D). (G–I)Netrostoma setouchianum live medusae from Kamo aquarium (G). (J–M)Rhopilema esculentum live medusae from Kamo aquarium (J). Some Symbiodiniaceae associated with R. esculentum bore flagella (cyan arrow) suggesting free-living stages contaminated sample.

Table 2

| Species | Bell diameter of medusae (cm) | Average symbiodiniaceae diameter (µm) | Standard deviation (3 s.f.) | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cassiopea sp. | 7.5 | 15.1 | 1.660 | 50 |

| Mastigias albipunctata | 5 | 8.4 | 0.870 | 50 |

| Netrostoma setouchianum | 2 | 9.1 | 0.819 | 39 |

| Rhopilema esculentum | 4 | 7.4 | 1.114 | 16 |

Bell diameter of medusae and average cell size of associated Symbiodiniaceae from observations of four rhizostome jellyfish species.

Measurements conducted under light microscopy.

3.1.2 Mastigiidae

Mastigias 16S sequences (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S3) clustered into three clades as previously described (Souza and Dawson, 2018): ‘Mastigias papua’ (bootstrap: 78%), ‘M. albipunctata’ (91%) and ‘Mastigias sp. from Tufi’ (96%). Samples from this study fell into two separate clades, a clade with OR702602 comprising M. papua of Palau and China and the clade with OR702597, OR702598 and PV534092 comprising M. albipunctata of Japan, Indonesia, USA, and Papua New Guinea. The result was similar in the COI tree (Figure 2) with three strongly supported monophyletic clades: (M. papua: 98.3/99; M. albipunctata; 94.9/99; Tufi: */89), and the mean divergence between the M. papua and M. albipunctata clades estimated at 0.0904 (S.E. 0.0138) in MEGA 11. Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3) revealed M. albipunctata samples hosted dominant symbionts of either Cladocopium or Symbiodinium; tissue samples contained light colored Symbiodiniaceae cells with average diameter of 8.4 µm (Figures 4D–F, Table 2).

3.1.3 Cepheidae

Phylogenetic analyses of available cepheid sequences from NCBI (n=16) showed limited resolution with only a single sequence available each for Cephea cephea and Marivagia stellata and Cotylorhiza tuberculata comprising the majority (n=14) (Figure 1). Despite low sample coverage C. cephea exhibited high divergence (>0.09 mean evolutionary distance) from other cepheids, while Netrostoma setouchianum and M. stellata were more closely related (mean distance 0.029) based on Jukes-Cantor modeling and the rate variation among sites modelled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1). Albeit the availability of only C. cephea polyps for this study, Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 amplification confirmed Symbiodiniaceae presence in both cepheid species from Japan (Figure 3), and tree reconstruction placed their dominant endosymbionts within Cladocopium. Microscopy of N. setouchianum medusae tissue only revealed endosymbiotic Symbiodiniaceae with an average diameter of 9.1 µm (Figures 4G–I, Table 2).

3.1.4 Rhizostomatidae

Both Rhopilema esculentum samples from this study clustered within a well-supported clade comprising individuals from China, Korea, and Japan (Figures 1, 2). Medusae measured roughly 4 cm in bell diameter and harbored endosymbionts with an average diameter of 7.4 µm (Figures 4J–M; Table 2). Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 phylogenetics (Figure 3) revealed Cladocopium as the sole dominant symbiont genus of R. esculentum in this study, Symbiodiniaceae presence was validated with microscopy to have an average diameter of 7.4 µm (Table 2).

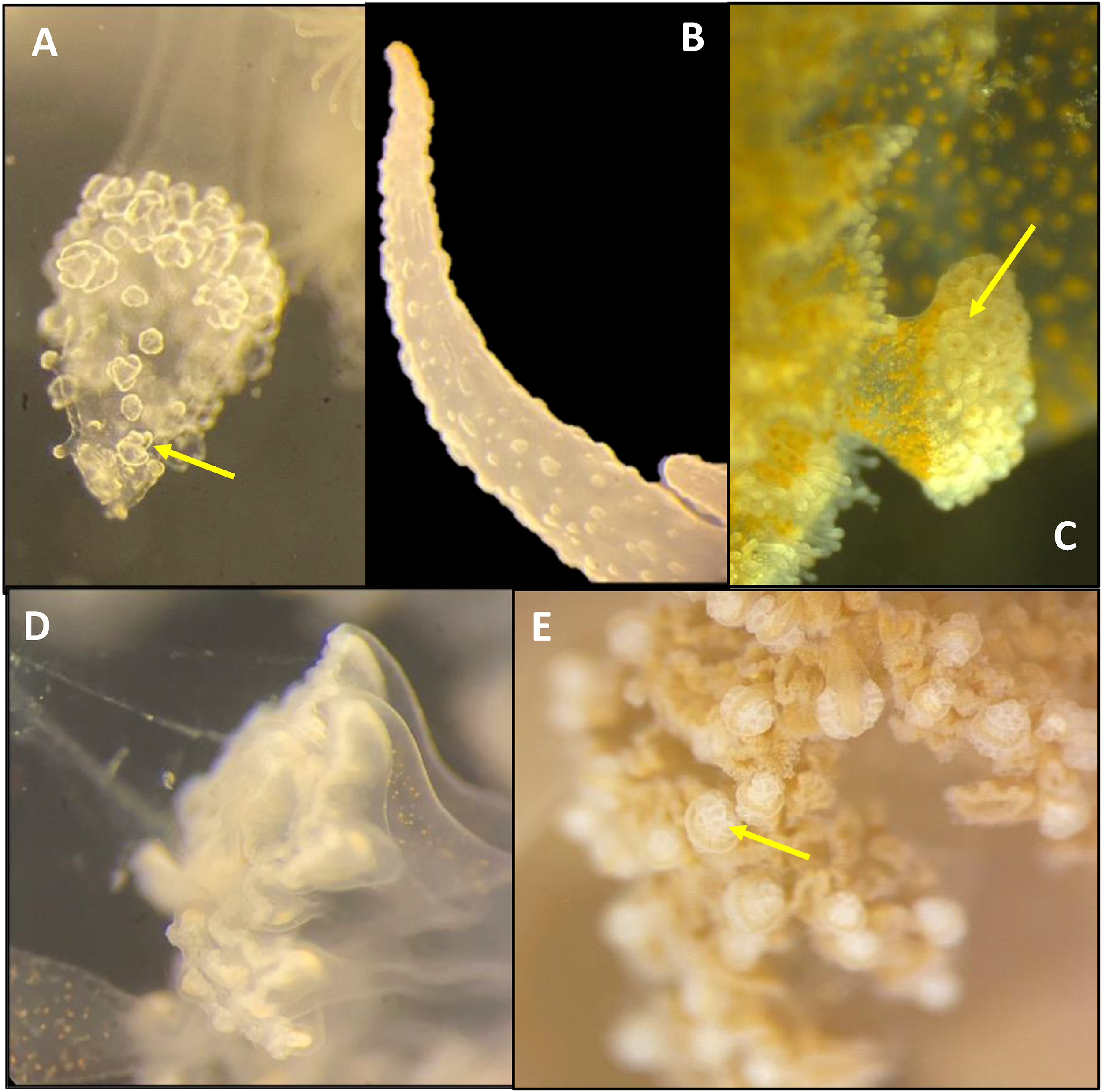

3.2 Cassiosome production

To confirm the presence of symbionts within the core of cassiosomes (Ames et al., 2020), a trait that is variable even within a single Cassiopea species (see Anthony et al., 2022), individual cassiosomes were isolated from mucus of respective rhizostome species using 3 mL pipettes and examined under a light microscope. Observations at 100× magnification identified the cell clusters as numerous nematocysts (Figure 5). In Cassiopea sp. from Kagoshima, cassiosomes contained Symbiodiniaceae cells within the mesoglea center surrounded by nematocysts (Figures 5A–C), whereas cassiosomes from N. setouchianum lacked these symbiotic dinoflagellates (Figures 5D, E). The bell diameter of Cassiopea sp. from Kagoshima measured 9 cm, while the other medusae, M. albipunctata, N. setouchianum, and R. esculentum, were smaller, ranging from 1.4 to 3.5 cm. After agitation, large amounts of mucus were secreted by all rhizostome medusae in this study. Analysis of under stereo microscope showed the presence of cassiosome in the mucus of N. setouchianum and Cassiopea from Kagoshima (Figure 5). Interestingly, though juvenile Mastigias samples from Kamo aquarium produced no cassiosomes, while larger specimens from Nagasaki, with bell diameters exceeding 7.5 cm, were confirmed to produce cassiosomes.

Figure 5

Microscopy of cassiosomes within the mucus expelled by two rhizostome jellyfishes. (A–C)Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima comprising oval isorhizas nematocysts (yellow arrows) in the periphery and conspicuous Symbiodiniaceae (green arrows) within the core, and (D, E)Netrostoma setouchianum comprising isorhiza nematocysts but lacking Symbiodiniaceae.

Examination of the oral arms revealed the presence of cassiosome-bearing structures, known as vesicular appendages, with “cassiosome nests” in N. setouchianum and Cassiopea sp. from Kagoshima, but not in R. esculentum or juvenile M. albipunctata from Kamo aquarium. (Figure 6). However, observation of oral arms of M. albipunctata from Nagasaki (bell diameter > 7.5 cm) showed the presence of cassiosome nests. This finding provides a hint at understanding cassiosome production patterns during medusa development, suggesting that the development of vesicular appendages on the oral arms is a prerequisite for cassiosome formation. The presence of cassiosomes in larger Mastigias specimens from Nagasaki raises questions about whether cassiosome production is restricted to certain life stages or size in this genus and requires further investigation.

Figure 6

Microscopy of medusa oral arms of four rhizostome taxa (A)Netrostoma setouchianum, (B)Rhopilema esculentum, (C) Nagasaki Mastigias albipunctata, (D) Kamo Mastigias albipunctata juvenile medusae and (E)Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima, examined under 4.0× magnification using stereo microscopy. Cassiosome nests (yellow arrow) are present only in N. setouchianum, Cassiopea sp. and Nagasaki M. albipunctata.

4 Discussion

This study sheds light on the hidden diversity, symbiotic capacities, and defense-related traits of a group of jellyfish species commonly displayed in public Aquariums, revealing novel phylogenetic lineages, previously undocumented symbiont–host interactions, and confirming cassiosome production in taxa for which prior reports were limited. These findings challenge existing assumptions about taxa previously dubbed “azooxanthellate” – believed not to bear Symbiodiniaceae – and provides a new framework for understanding the evolution of jellyfish-Symbiodiniaceae associations and the functional role of these symbionts in cassiosomes.

4.1 Phylogenetic analyses

Our phylogenetic analysis comprises genera found in Japanese aquariums includes previously described and undescribed lineages.

Cassiopea sp., specimens from Kagoshima fell into three separate clades across all gene trees, suggesting sympatric distribution of multiple species in the region. The high divergence and strong support for a unique phylogenetic clade suggests a potentially novel Cassiopea taxon originating in Kagoshima. In both the 16S and 28S trees, Kagoshima Cassiopea samples formed a distinct clade, while COI sequences grouped with an undescribed Cassiopea species from Australia, French Polynesia, Hawaii, and Papua New Guinea. Given the cryptic diversity within Cassiopea (Gamero-Mora et al., 2022; Muffett and Miglietta, 2023; Stampar et al., 2020), further integrative studies combining morphology, molecular markers, and other traits are needed to clarify the taxonomic status of Kagoshima populations. Additionally, one sample (OR702605) clustered closely with Cassiopea xamachana from Florida (Supplementary Figure S3), raising the possibility of an invasion possibly via anthropogenic introduction.

The genus MastigiasAgassiz, 1862 has historically been classified into eight species (Kramp, 1961) based on morphology, with Mastigias papua (Lesson, 1830) as the type species. Recent molecular studies (Swift et al., 2016; Souza and Dawson, 2018) indicate that Mastigias can be separated into three distinct clades based on both genetic and geographic factors. The earliest record of Mastigias in Japan (Kishinouye, 1895) originally described it as a new species, though past literature lacked molecular evidence causing confusion regarding proper assignment of Japanese Mastigias with M. papua or M. albipunctata (Uchida, 1926; Hamaguchi et al., 2021). The COI phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) in our study aligns with previous findings (Souza and Dawson, 2018) confirming that Japanese Mastigias belong to the M. albipunctata clade. This is further supported by recent mitogenomic analyses showing that a specimen previously labeled as M. papua (OZ025288) is more closely related to M. albipunctata than to other M. papua samples (Tan et al., 2024), highlighting potential misidentifications and reinforcing the genetic distinctiveness of the M. albipunctata lineage. In contrast, the 16S tree (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S3) showed lower resolution and smaller evolutionary divergence values, possibly reflecting slower gene evolution in the 16S rRNA region, albeit distinct clades. We note that, one specimen from Kamo aquarium (OR702602) grouped with M. papua, which may reflect of inter-aquarium animal exchanges in which individuals from separate lineages may have been introduced. It is important to note, however, given that the aquarium trade is subject to a high degree of specimen sharing at a global scale, inter-species crosses, and contamination of cultures is not entirely avoidable. More extensive sampling of Japanese wild populations will help solve this enigma.

Phylogenetic analyses revealed additional Kamo aquarium samples corresponded to Cephea cephea, Netrostoma setouchianum, and Rhopilema esculentum. For R. esculentum, phylogenetic pattern matches previous records of its distribution in East Asia and supports the reliability of our molecular identification. The consistent grouping across gene regions also adds confidence in its placement within current Rhizostomeae phylogenies. However, the classification of the suborder Cepheidae remains unresolved due to limited sample numbers; COI was not successfully amplified. Despite this limitation, the strong branch support for the 16S region (100% bootstrap) is consistent with existing classifications (Galil et al., 2010, 2017; Gershwin and Zeidler, 2008; Gul et al., 2015; Yap and Ong, 2012), reinforcing that Cepheidae consists of at least four distinct genera.

The results contribute to ongoing efforts to refine Scyphozoa taxonomy using molecular tools and highlight the need for combining different approaches to better understand cryptic diversity in widely distributed taxa. These findings may also be useful for public aquaria, conservation work, and studies on jellyfish evolution.

4.2 Symbiodiniaceae identification

The 28S phylogenetic tree (Figure 7) constructed from DNA sequenced from excised gel mirrored ITS2 analyses, confirming the reliability of the method for quick symbiont identification. Specifically, M. albipunctata sequences clustered within Cladocopium and Symbiodinium, Cassiopea sp. from Kagoshima grouped with Cladocopium and Durusdinium, while C. cephea associated exclusively with Cladocopium.

Figure 7

Comparison of ML phylogenetic trees for Symbiodiniaceae based on (A) the ITS2 region and (B) the 28S gene region. The 28S tree includes sequences generated in this study (n = 11) using broad metazoan 28S region primers and reference data from NCBI GenBank (total n = 53). Polarella glacialis is used as outgroup (n=2). Bold labels are samples from this study. Numbers represent SH-aLRT/Ultrafast bootstrap support (%). Clade names (A–E) correspond to Symbiodinium lineages now recognized as separate genera. Photo sources: Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima, Mastigias albipunctata and Rhopilema esculentum photographed by coauthors at Kamo Aquarium (Tsuruoka, Japan in 2022), Netrostoma setouchianum photographed by Hiroyuki Ozawa 2022 from a seagrass bed (Okinawa 2022), Cephea cephea by CORDENOS Thierry, 2020 (photos under CC-BY-NC licenses) as a ‘Research Grade’ assigned taxon by iNaturalist (inaturalist.org accessed on 4 February 2024).

Sequences analyzed were consistent with previously identified Symbiodiniaceae genera in Cassiopea and Mastigias (Dall’Olio et al., 2022; Ohdera et al., 2018; Muscatine et al., 1986; Santos et al., 2002; Thornhill et al., 2006; Vega de Luna et al., 2019; Verde and McCloskey, 1998). N. setouchianum did not yield successful ITS2 amplification of Symbiodiniaceae genera, although the presence of Symbiodiniaceae was confirmed with microscopy, suggesting low symbiont densities or potential release of endosymbionts after the polyp stage (reported in C. cephea). For Netrostoma and Cephea, Symbiodiniaceae presence was reported in ephyrae in previous studies (Sugiura, 1969; Straehler-Pohl and Jarms, 2010) while in R. esculentum Symbiodiniaceae was previously unreported, and little information is available on the species’ ability to host Symbiodiniaceae. In this study, we present the first combined molecular and microscopic evidence of Symbiodiniaceae in R. esculentum. Samples were identified as hosting Cladocopium based on ITS2 sequences, and light microscopy revealed symbiont-like cells around 7.4 µm in diameter. Although this is an interesting finding, it does not confirm whether the association is truly facultative or a temporal necessity. Given the small sample size and lack of histological confirmation, it remains unclear whether R. esculentum forms a stable, permanent symbiosis with these dinoflagellates. Still, our observations suggest the possibility of facultative symbiosis and that jellyfish species previously thought to be azooxanthellate might have a greater capacity for symbiotic association than expected.

All aquarium-reared samples exclusively harbored Cladocopium, whereas wild-caught specimens exhibited variation in their symbiont composition, suggesting potential environmental or developmental influences on symbiont acquisition. Our results suggest that host specificity, symbiont availability, and physiological requirements play key roles in Symbiodiniaceae-jellyfish interactions. Further studies should focus on histological analyses and metabarcoding to understand the gamut and mechanisms of symbiont association across rhizostome taxa.

The tandem PCR approach developed herein provides a rapid and efficient method to detect both the host rhizostome jellyfish and its dominant Symbiodiniaceae present, allowing simultaneous amplification and separation of both organisms in a single PCR reaction. This method offers a streamlined alternative for identifying dominant Symbiodiniaceae association at the genus level in rhizostomes. Going forward, additional refinements to amplification protocols may improve detection sensitivity, particularly in species with possible variable symbiont loads or developmental-stage-specific associations (Djeghri et al., 2019).

4.3 Cassiosome production

This study provides confirmation of cassiosome production in N. setouchianum using microscopy, corroborating previous observations from citizen science reports (Ames et al., 2020). Cassiosomes from Cassiopea sp. Kagoshima contained Symbiodiniaceae, which were absent from N. setouchianum (Figure 5), despite both species possessing Symbiodiniaceae within their tissue (Figures 4A–C, G–I), suggesting N. setouchianum may lose their endosymbionts at maturity (Djeghri et al., 2019).

Cassiosomes were observed in larger Mastigias specimens suggesting that cassiosome production in Mastigias may be size- or maturity-dependent, i.e., based on when vesicular appendages appear, as cassiosomes were observed in Mastigias specimens from Nagasaki with bell diameters > 7.5 cm and previously documented in Mastigias medusae that were bigger (Ames et al., 2020). Notably, Rhopilema specimens showed no sign of cassiosome production. However, future studies focusing on the onset of cassiosome-producing structures may provide a better estimate across the clade.

5 Conclusion

This study evaluated rhizostome jellyfishes species and their symbionts commonly cultured in Japanese aquariums using molecular analyses and information on cassiosome production. We also present herein our novel tandem PCR-based method for rapid detection of dominant Symbiodiniaceae in rhizostome hosts. Our results confirm four of the five species successfully reared in captivity displayed cassiosome production, however, the onset of cassiosomes production has not been well-defined. These rhizostome species are ubiquitous in Japanese aquarium exhibits and, as such, accurate identification and communication to the public are essential. Surprisingly, amplicons sequenced of one Cassiopea medusa corresponded to C. xamachana, which is normally endemic to the Florida Keys in U.S. A., suggests it may have been introduced into Japanese waters. Therefore, caution is needed before assigning species names in the absence of morphological examination.

Our findings contribute to the broader understanding of rhizostome diversity in Japan, as well as to the evolution of jellyfish-Symbiodiniaceae symbioses and cnidarian defense mechanisms. Future research should expand sampling across developmental stages and geographic ranges, including rhizostome populations outside of Japan, to clarify the role of Symbiodiniaceae plasticity in the host medusa’s adaptation and evolution, and the ecological function of cassiosomes. Long-term studies incorporating time-series observations may provide insight into how Symbiodiniaceae composition shifts in host jellyfish taxa over time and the onset of cassiosome production across rhizostome species.

Statements

Data availability statement

Jellyfish and Symbiodiniaceae DNA sequence data generated in this study have been deposited into GenBank (Table 1). Additional materials, including phylogenetic tree files, sequence alignments, and supplementary figures and tables, are available through Zenodo at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18251398.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because All jellyfish specimens used in this study are not endangered or protected species. Therefore, ethical approval or permission was not necessary.

Author contributions

KT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SI: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. RT: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. KO: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MC: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. GN: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MI: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) AIMEC, MEXT, Japan (CLA). KT was funded by the K. Matsushita Foundation (KMMF) Scholarship for her master’s studies. The article processing charge (APC) for this publication was supported by Tohoku University through the 2025 Open Access Promotion APC Support Program.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the kind assistance of staff at all aquariums mentioned herein, Dr. Hiroyuki Ozawa for providing a photo of Netrostoma setouchianum. We are grateful to the two reviewers whose expertise and guidance facilitated the improvement of this manuscript and to the editor for careful handling of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1679299/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Agassiz L. (1860). Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America Vol. 3 (Cambridge: Little, Brown & Co), 1–301.

2

Agassiz L. (1862). Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America. Little, Brown, Boston. 4: 1–380, pls 1-19.

3

Altschul S. F. Gish W. Miller W. Myers E. W. Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol.215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

4

Ames C. L. Klompen A. M. L. Badhiwala K. Muffett K. Reft A. J. Kumar M. et al . (2020). Cassiosomes are stinging-cell structures in the mucus of the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana. Commun. Biol.3, 67. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0777-8

5

Anthony C. J. Heagy M. Bentlage B. (2022). Phenotypic plasticity in Cassiopea ornata (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) suggests environmentally driven morphology. Zoomorphology141, 115–131. doi: 10.1007/s00435-022-00558-4

6

Bayha K. M. Dawson M. N. Collins A. G. Barbeitos M. S. Haddock S. H. D. (2010). Evolutionary relationships among scyphozoan jellyfish families based on complete taxon sampling and phylogenetic analyses of 18S and 28S ribosomal DNA. Integr. Comp. Biol.50, 436–455. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq074

7

Bigelow R. P. (1892). On a new species of Cassiopea from Jamaica. Zoologischer Anzeiger15, 212–214.

8

Brotz L. (2016). Jellyfish fisheries of the world (Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia). Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/2429/60243 (Accessed May 15, 2023).

9

Camacho-Pacheco A. V. Gómez-Salinas L. C. Cisneros-Mata M.Á. Rodríguez-Félix D. Díaz-Tenorio L. M. Unzueta-Bustamante M. L. (2022). Feeding behavior, shrinking, and the role of mucus in the cannonball jellyfish Stomolophus sp. 2 in captivity. Diversity14 (2), 103. doi: 10.3390/d14020103

10

Chombard C. Boury-Esnault N. Tillier A. Vacelet J. (1997). Polyphyly of “Sclerosponges” (Porifera, demospongiae) supported by 28S ribosomal sequences. Biol. Bull.193, 359–367. doi: 10.2307/1542938

11

Collins A. G. Morandini A. Cartwright P. (2025). World List of Scyphozoa (version 2025-07-01) ( Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species). doi: 10.48580/dgrrq-3fz

12

Cuvier G. (1800). Mémoire sur l’organisation de quelques méduses. Bull. Des. Sciences Société Philomathique Paris2, 69.

13

Dall’Olio L. R. Beran A. Flander-Putrle V. Malej A. Ramšak A. (2022). Diversity of dinoflagellate symbionts in scyphozoan hosts from shallow environments: The Mediterranean Sea and Cabo Frio (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.867554

14

Daryanabard R. Dawson M. N. (2008). Jellyfish blooms: Crambionella orsini (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in the Gulf of Oman, Iran 2002–2003. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom88, 477–483. doi: 10.1017/S0025315408000945

15

Davies S. W. Gamache M. H. Howe-Kerr L. I. Kriefall N. G. Baker A. C. Banaszak A. T. et al . (2023). Building consensus around the assessment and interpretation of Symbiodiniaceae diversity. PeerJ11, e15023. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15023

16

Djeghri N. Pondaven P. Stibor H. Dawson M. N. (2019). Review of the diversity, traits, and ecology of zooxanthellate jellyfishes. Mar. Biol.166, 147. doi: 10.1007/s00227-019-3581-6

17

Enrique-Navarro A. Huertas E. Flander-Putrle V. Bartual A. Navarro G. Ruiz J. et al . (2022). Living inside a jellyfish: The symbiosis case study of host-specialized dinoflagellates, “zooxanthellae”, and the scyphozoan Cotylorhiza tuberculata. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.817312

18

Falkenhaug T. (2014). Review of jellyfish blooms in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Mar. Biol. Res.10, 1038–1039. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2014.880790

19

Fernández-Alías A. Marcos C. Quispe J. I. Sabah S. Pérez-Ruzafa A. (2020). Population dynamics and growth in three scyphozoan jellyfishes, and their relationship with environmental conditions in a coastal lagoon. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.243, 106901. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2020.106901

20

Forskål P. (1775). Descriptiones Animalium, Avium, Amphibiorum, Piscium, Insectorum, Vermium; quae in Itinere Orientali Observavit Petrus Forskål (Hafniae [Copenhagen]: Post mortem auctoris edidit Carsten Niebuhr. Adjuncta est Materia Medica Kahirina. Mölleri), 164 pp. Hafniae. 19 + xxxiv.

21

Galil B. Gershwin L.-A. Douek J. Rinkevich B. (2010). Marivagia stellata gen. et sp. nov. (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae: Cepheidae), another alien jellyfish from the Mediterranean coast of Israel. AI5, 331–340. doi: 10.3391/ai.2010.5.4.01

22

Galil B. S. Gershwin L.-A. Zorea M. Rahav A. Rothman S. B.-S. Fine M. et al . (2017). Cotylorhiza erythraea Stiasny 1920 (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae: Cepheidae), yet another erythraean jellyfish from the Mediterranean coast of Israel. Mar. Biodiversity47, 229–235. doi: 10.1007/s12526-016-0449-6

23

Gamero-Mora E. Collins A. G. Boco S. R. Geson S. M. Morandini A. C. (2022). Revealing hidden diversity among upside-down jellyfishes (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae: Cassiopea): distinct evidence allows the change of status of a neglected variety and the description of a new species. Invert. Systematics36, 63–89. doi: 10.1071/IS21002

24

Geller J. Meyer C. Parker M. Hawk H. (2013). Redesign of PCR primers for mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I for marine invertebrates and application in all-taxa biotic surveys. Mol. Ecol. Resour.13, 851–861. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12138

25

Gershwin L.-A. Zeidler W. (2008). Two new jellyfishes (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) from tropical Australian waters. Zootaxa1764, 41–52. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.1764.1.4

26

Gouy M. Tannier E. Comte N. Parsons D. P. (2021). “ “Seaview version 5: A multiplatform software for multiple sequence alignment, molecular phylogenetic analyses, and tree reconciliation,” in Multiple Sequence Alignment: Methods and Protocols. Ed. KatohK. ( Springer US, New York, NY), 241–260. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1036-7_15

27

Griekspoor A. Groothuis T. (2006). 4Peaks. Available online at: https://nucleobytes.com (Accessed May 15, 2023).

28

Gul S. Mohammad Moazzam M. Morandini A. C. (2015). Crowned jellyfish (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae: Cepheidae) from waters off the coast of Pakistan, northern Arabian Sea. cl11, 1551. doi: 10.15560/11.1.1551

29

Hamaguchi Y. Iida A. Nishikawa J. Hirose E. (2021). Umbrella of Mastigias papua (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae: Mastigiidae): hardness and cytomorphology with remarks on colors. Plankton Benthos Res.16, 221–227. doi: 10.3800/pbr.16.221

30

Helm R. R. (2018). Evolution and development of scyphozoan jellyfish. Biol. Rev.93, 1228–1250. doi: 10.1111/brv.12393

31

Hoang D. T. Chernomor O. von Haeseler A. Minh B. Q. Vinh L. S. (2018). UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281

32

Hsieh Y.-H. P. Leong F.-M. Rudloe J. (2001). “ Jellyfish as food,” in Jellyfish Blooms: Ecological and Societal Importance. Eds. PurcellJ. E.GrahamW. M.DumontH. J. ( Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 11–17.

33

Hume B. C. C. Ziegler M. Poulain J. Pochon X. Romac S. Boissin E. et al . (2018). An improved primer set and amplification protocol with increased specificity and sensitivity targeting the Symbiodinium ITS2 region. PeerJ6, e4816. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4816

34

Jarms G. Morandini A. C. (2023). World Atlas of Jellyfish. (Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz Verlag).

35

Jufri A. W. (2019). Contributions of the medusae of phyllorhiza punctata (Scyphozoa: rhizostomae) in production of dissolved organic carbon (DOC). Biota : Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu-Ilmu Hayati10, 17–23. doi: 10.24002/biota.v10i1.2794

36

Jukes T. H. Cantor C. R. (1969). “ Evolution of protein molecules,” in Mammalian Protein Metabolism. Ed. MunroH. N. ( Academic Press, New York, NY), 21–132.

37

Kalyaanamoorthy S. Minh B. Q. Wong T. K. F. von Haeseler A. Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods14, 587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285

38

Katoh K. Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010

39

Kikinger R. (1992). Cotylorhiza tuberculata (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) – Life history of a stationary population. Mar. Ecol.13, 333–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1992.tb00359.x

40

Kingsford M. Pitt K. A. Gillanders B. M. (2000). Management of jellyfish fisheries, with special reference to the order Rhizostomeae. Oceanography Mar. Biol.28, 85–156.

41

Kishinouye K. (1891). Bizen kurage. Zoological Magazine (Dobutsugaku Zasshi)3, 53.

42

Kishinouye K. (1895). Description of a new Rhizostoma Mastigias physophora, nov. spec. Zoological magazine (Dobutsugaku zasshi). 7(78): 86–88.

43

Kishinouye K. (1902). Some new scyphomedusae of Japan. J. Coll. Science Tokyo Imperial Univ.17, 1–17.

44

Kishinouye K. (1922). Echizen kurage. Zoological magazine (Dobutsugaku zasshi). 34:343–346.

45

Kitamura M. Omori M. (2010). Synopsis of edible jellyfishes collected from Southeast Asia, with notes on jellyfish fisheries. Plankton Benthos Res.5, 106–118. doi: 10.3800/pbr.5.106

46

Kramp P. L. (1961). Synopsis of the medusae of the world. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom40, 7–382. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400007347

47

LaJeunesse T. C. (2001). Investigating the biodiversity, ecology, and phylogeny of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium using the ITS region: In search of a “species level marker. J. Phycology37, 866–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.01031.x

48

LaJeunesse T. C. Parkinson J. E. Gabrielson P. W. Jeong H. J. Reimer J. D. Voolstra C. R. et al . (2018). Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol.28, 2570–2580.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008

49

LaJeunesse T. C. Wiedenmann J. Casado-Amezúa P. D’Ambra I. Turnham K. E. Nitschke M. R. et al . (2022). Revival of Philozoon geddes for host-specialized dinoflagellates, ‘zooxanthellae’, in animals from coastal temperate zones of northern and southern hemispheres. Eur. J. Phycology57, 166–180. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2021.1914863

50

Lawley J. W. Ames C. L. Bentlage B. Yanagihara A. Goodwill R. Kayal E. et al . (2016). Box jellyfish alatina alata has a circumtropical distribution. Biol. Bull.231, 152–169. doi: 10.1086/690095

51

Lesson R. P. (1830). Voyage autour du monde, exécuté par ordre du Roi, sur la corvette de Sa Majesté, La Coquille, pendant les années 1822, 1823, 1824 et 1825. Zoologie, 2(1), 1–471 [pp. 1–24, pls 1–9 (1830); 25–471, pls 10–16 (1831)]. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. pp. 122–123, pl. XI.

52

Letunic I. Bork P. (2024). Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res.52, W78–W82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae268

53

Macri S. (1778). Nuove osservazioni intorno la storia naturale del Polmone marino degli antichi. Naples. Available online at: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=SmKhhoTo1QAC&ots=wstxnPMaPm&lr&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

54

Medina M. Sharp V. Ohdera A. Bellantuono A. Dalrymple J. Gamero-Mora E. et al . (2021). “ The upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana as an emerging model system to study cnidarian–algal symbiosis,” in Handbook of Marine Model Organisms in Experimental Biology: Established and Emerging (Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press), 149–171. doi: 10.1201/9781003217503-9

55

Muffett K. M. Klompen A. M. L. Collins A. G. Lewis Ames C. (2021). Raising awareness of the severity of “contactless stings” by Cassiopea jellyfish and kin. Animals11, 3357. doi: 10.3390/ani11123357

56

Muffett K. Miglietta M. P. (2023). Demystifying Cassiopea species identity in the Florida Keys: Cassiopea xamachana and Cassiopea andromeda coexist in shallow waters. PLoS One18, e0283441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283441

57

Muscatine L. Wilkerson F. McCloskey L. (1986). Regulation of population density of symbiotic algae in a tropical marine jellyfish (Mastigias sp.). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.32, 279–290. doi: 10.3354/meps032279

58

Namikawa H. Soyama I. (2000). クラゲガイドブッ: Jellyfish in Japanese waters [Kurage gaidobukku: Jellyfish in Japanese waters] (Tokyo: TBS Britannica).

59

Newkirk C. R. Frazer T. K. Martindale M. Q. Schnitzler C. E. (2020). Adaptation to bleaching: are thermotolerant symbiodiniaceae strains more successful than other strains under elevated temperatures in a model symbiotic cnidarian? Front. Microbiol.11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00822

60

Nitschke M. R. Craveiro S. C. Brandão C. Fidalgo C. Serôdio J. Calado A. J. et al . (2020). Description of Freudenthalidium gen. nov. and Halluxium gen. nov. to formally recognize clades Fr3 and H as genera in the family Symbiodiniaceae (Dinophyceae). J. Phycology56, 923–940. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12999

61

Nitschke M. R. Rosset S. L. Oakley C. A. Gardner S. G. Camp E. F. Suggett D. J. et al . (2022). The diversity and ecology of Symbiodiniaceae: A traits-based review. Adv. Mar. Biol.92, 55–127. doi: 10.1016/bs.amb.2022.07.001

62

Ohdera A. H. Abrams M. J. Ames C. L. Baker D. M. Suescún-Bolívar L. P. Collins A. G. et al . (2018). Upside-down but headed in the right direction: Review of the highly versatile Cassiopea xamachana system. Front. Ecol. Evol.6. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00035

63

Omori M. (1982). Edible jellyfish (Scyphomedusae: Rhizostomeae) in the Far East [Sea] waters: A brief review of the biology and fishery 1981. Bull. Plankton Soc. Japan28, 1–11.

64

Omori M. Nakano E. (2001). “ Jellyfish fisheries in Southeast Asia,” in Jellyfish Blooms: Ecological and Societal Importance. Eds. PurcellJ. E.GrahamW. M.DumontH. J. ( Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 19–26.

65

Pochon X. LaJeunesse T. C. (2021). Miliolidium n. gen, a new symbiodiniacean genus whose members associate with soritid foraminifera or are free-living. J. Eukaryotic Microbiol.68, e12856. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12856

66

Purcell J. E. (2012). Jellyfish and ctenophore blooms coincide with human proliferations and environmental perturbations. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.4, 209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142751

67

Rambaut A. (2018). FigTree software. Available online at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (Accessed May 15, 2023).

68

Raposo A. Alasqah I. Alfheeaid H. A. Alsharari Z. D. Alturki H. A. Raheem D. (2022). Jellyfish as food: A narrative review. Foods11, 2773. doi: 10.3390/foods11182773

69

Santos S. R. Taylor D. J. Kinzie I. Robert A. Hidaka M. Sakai K. et al . (2002). Molecular phylogeny of symbiotic dinoflagellates inferred from partial chloroplast large subunit (23S)-rDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.23, 97–111. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00010-6

70

Savoca S. Di Fresco D. Alesci A. Capillo G. Spanò N. (2022). Mucus secretions in Cnidarian, an ecological, adaptive and evolutive tool. Adv. Ocean Limnol13, 11054. doi: 10.4081/aiol.2022.11054

71

Sharp V. Kerwin A. H. Mammone M. Avila-Magana V. Turnham K. Ohdera A. et al . (2024). Host–symbiont plasticity in the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana: strobilation across symbiont genera. Front. Ecol. Evol.12. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2024.1333028

72

Souza M. R. D. Dawson M. N. (2018). Redescription of Mastigias papua (Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae) with designation of a neotype and recognition of two additional species. Zootaxa4457. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4457.4.2

73

Stampar S. N. Gamero-Mora E. Maronna M. M. Fritscher J. M. Oliveira B. S. P. Sampaio C. L. S. et al . (2020). The puzzling occurrence of the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) along the Brazilian coast: a result of several invasion events? Zoologia37, 1–10. doi: 10.3897/zoologia.37.e50834

74

Stecher G. Tamura K. Kumar S. (2020). Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Mol. Biol. Evol.37, 1237–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz312

75

Stiasny G. (1920). Die scyphomedusen-sammlung des naturhistorischen reichsmuseums in leiden: III. Rhizostomae. Zoologische Mededelingen5.

76

Stiasny G. (1921). Studien über rhizostomeen mit besonderer berücksichtigung der fauna des Malaiischen archipels nebst einer revision des systems. Available online at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/43974 (Accessed May 15, 2023).

77

Straehler-Pohl I. Jarms G. (2010). Identification key for young ephyrae: a first step for early detection of jellyfish blooms. Hydrobiologia645, 3–21. doi: 10.1007/s10750-010-0226-7

78

Sugiura Y. (1964). On the life-history of rhizostome medusae II. Indispensability of zooxanthellae for strobilation in Mastigias papua. Embryologia8, 223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.1964.tb00200.x

79

Sugiura Y. (1969). On the life-history of rhizostome medusae V. On the relation between zooxanthellae and the strobilation of Cephea cephea. Bull. Mar. Biol. Station Asamushi13, 227–232.

80

Swift H. F. Gómez Daglio L. Dawson M. N. (2016). Three routes to crypsis: Stasis, convergence, and parallelism in the Mastigias species complex (Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.99, 103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.02.013

81

Syazwan W. M. Rizman-Idid M. Low L. B. Then A. Y.-H. Chong V. C. (2020). Assessment of scyphozoan diversity, distribution and blooms: Implications of jellyfish outbreaks to the environment and human welfare in Malaysia. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci.39, 101444. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2020.101444

82

Tamura K. Stecher G. Kumar S. (2021). MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol.38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

83

Tan K. C. Ames C. L. Collins A. G. (2024). Complete linear mitochondrial genomes for Cephea cephea and Mastigias albipunctata (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae), with an analysis of phylogenetic relationships. Mitochondrial DNA Part B9, 1544–1548. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2024.2429644

84

Thornhill D. J. Daniel M. W. LaJeunesse T. C. Schmidt G. W. Fitt W. K. (2006). Natural infections of aposymbiotic Cassiopea xamachana scyphistomae from environmental pools of Symbiodinium. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.338, 50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2006.06.032

85

Toshino S. (2018). New record of upside-down jellyfish, Cassiopea sp. (Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae), from Sukumo Bay, Shikoku, western Japan. Bulletin of the Biogeographical Society of Japan72, 200–203.

86

Trifinopoulos J. Nguyen L.-T. von Haeseler A. Minh B. Q. (2016). W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.44, W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256

87

Uchida T. (1926).

88

Uchida T. (1954). Distribution of Scyphomedusae in Japanese and its adjacent waters (With 2 text-figures). J. Faculty Science Hokkaido University. Ser. 6 Zoology12, 202–219.

89

Uye S. (2008). Blooms of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai: A threat to the fisheries sustainability of the East Asian Marginal Seas. Plankton Benthos Res.3, 125–131. doi: 10.3800/pbr.3.125

90

Vanhöffen E. (1888). Untersuchungen über semäostome und rhizostome Medusen. Bibliotheca Zoologica1, 1–52.

91

Vega de Luna F. Dang K.-V. Cardol M. Roberty S. Cardol P. (2019). Photosynthetic capacity of the endosymbiotic dinoflagellate Cladocopium sp. is preserved during digestion of its jellyfish host Mastigias papua by the anemone Entacmaea medusivora. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.95, fiz141. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz141

92

Verde E. A. McCloskey L. R. (1998). Production, respiration, and photophysiology of the mangrove jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana symbiotic with zooxanthellae: effect of jellyfish size and season. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.168, 147–162. doi: 10.3354/meps168147

93

Yap N. W. L. Ong O. J. (2012). A survey of jellyfish (Cnidaria) around St John’s Island in the Singapore Straits. Contributions to Mar. Sci.2012, 57–74.

Summary

Keywords

mixotrophic jellyfishes, photoendosymbiosis, microscopy, synapomorphic trait, fisheries and aquaculture, tandem host-symbiont amplification

Citation

Tan KC, Chikuchishin M, Ikeda S, Tamada R, Okuizumi K, Nishitani G, Ikeda M and Ames CL (2026) A comparative molecular study of rhizostome jellyfishes (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae) from Japan reveals variability in Symbiodiniaceae taxon associations and cassiosome production. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1679299. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1679299

Received

04 August 2025

Revised

01 November 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

30 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ciro Rico, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Reviewed by

Mbaye Tine, Gaston Berger University, Senegal

Edgar Gamero-Mora, National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Tan, Chikuchishin, Ikeda, Tamada, Okuizumi, Nishitani, Ikeda and Ames.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kei Chloe Tan, tan.kei.chloe.e2@tohoku.ac.jp; Cheryl Lewis Ames, ames.cheryl.lynn.a1@tohoku.ac.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.