Abstract

Small-scale fisheries play an essential role in supporting food security and economic resilience in Madagascar’s coastal communities. These fisheries are diverse, ranging from offshore net and line fishing, often dominated by men, to nearshore gleaning and hand-held spearfishing, frequently practiced by women. Despite their importance, they remain underrepresented in official statistics, and women’s contributions are often underreported. Few studies have examined how gender, gear type, and regional context interact to shape catch composition and productivity across ecological and social settings. To address this gap, we analyzed catch-per-unit-effort data from 9,068 fishing trips conducted in 2023–2024 across 17 villages in two coastal regions of Madagascar: Diana in the north and Atsimo-Andrefana in the southwest. We examined how gear use, catch composition, and productivity varied by gender and region, complemented by social surveys documenting fishers’ habitats, access modes (e.g., walking, sailboat), and key organisms harvested. Framed within a coupled human-natural systems perspective, our approach recognizes reciprocal links between ecological conditions, fishing practices, and socio-economic contexts. Gamma GLMs showed that catch-per-unit-effort was consistently higher in Diana, consistent with healthier reefs and greater access to efficient gears. Spearguns, predominantly used by men, yielded the highest predicted catch-per-unit-effort (3.00 kg fisher-1 h-1 in Diana; 1.23 in Atsimo-Andrefana). Hand-held spears also performed well, particularly in Diana, where women had slightly higher catch-per-unit-effort than men (2.13 vs. 1.85 kg fisher-1 h-1), reflecting shorter, targeted trips for octopus and fish. In contrast, fishers in Atsimo-Andrefana operated in habitats characterized as more degraded and used less advanced gear, resulting in lower overall catch-per-unit-effort and greater diversification, especially among women harvesting invertebrates. All catch-per-unit-effort values were calculated using total trip duration, and some catch weights were imputed from average species weights. Despite uneven sampling effort, sensitivity analyses confirmed these factors did not alter conclusions. This analysis provides a quantitative baseline for future work tracking how coupled social and ecological dynamics in these fisheries evolve over time. Our results highlight how ecological conditions, gear access, and gendered practices shape fishing strategies, emphasizing the need for management approaches addressing both environmental change and the social realities of communities dependent on marine resources.

1 Introduction

Small-scale fisheries (SSF) sustain the livelihoods of over 100 million people worldwide and are critical for food security, cultural identity, and economic resilience, particularly in regions where alternative livelihoods are limited (Béné, 2006; FAO, 2022). They are also classic examples of coupled natural and human (CNH) systems, where ecological processes and human activities are tightly interlinked through reciprocal feedbacks (Cinner et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2007, 2021). Across diverse contexts, fishing effort, gear choice, and catch composition shift in response to changing habitat conditions and species availability, which in turn interact with human values and governance systems, collectively determining ecosystem health, resource availability, and long-term resilience of these social-ecological systems (Bahri et al., 2021; Kittinger et al., 2015; Ojea et al., 2020; Quezada-Escalona et al., 2025). Gender is a central dimension of these systems: women participate in harvesting, post-harvest processing, and trade, and their contributions are shaped by cultural norms and access to resources, as well as local ecological conditions (Harper et al., 2013; Kleiber et al., 2014a). Men and women frequently face different constraints and opportunities in fishing, creating distinct vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities (Fröcklin et al., 2014). These patterns vary not only between countries but also within them, as differences in habitat type, infrastructure, and market access can produce significant intra-regional variation in fishing practices and outcomes (Cinner et al., 2009; Harper et al., 2020).

In Madagascar, small-scale fisheries can contribute over 80% of household income (Barnes-Mauthe et al., 2013) and account for roughly 72% of the country’s domestic fish catch (Le Manach et al., 2012). Fishing strategies range from offshore net and line fishing to nearshore gleaning and spearfishing, reflecting the ecological and cultural diversity of coastal communities. Yet, these fisheries remain underrepresented in official statistics. For example, reconstructed catch estimates suggest that Madagascar’s actual harvest is at least double that reported to the FAO, largely due to the exclusion of subsistence fisheries (Le Manach et al., 2011). At the same time, foreign industrial fishing, which is often poorly monitored, operates extensively within Madagascar’s Exclusive Economic Zone and even encroaches on nearshore areas, threatening the sustainability of local fisheries and undermining community-led management (White et al., 2021). These pressures interact with local ecological conditions and governance structures, creating feedbacks that influence where, how, and what people fish. Regional differences in target species, gear use, and habitat conditions further shape catch dynamics and fishing effort (Laroche et al., 1997; Farquhar et al., 2022). With reports of declining catches, smaller fish sizes, and habitat degradation, particularly in southwestern Madagascar (Gough et al., 2020; Ranaivomanana et al., 2023), understanding how these coupled ecological and social drivers vary across regions is essential.

Gender dynamics strongly influence small-scale fisheries, yet they remain underacknowledged in policy. In Madagascar, men and women tend to fish in different habitats using distinct gear types to target various species. Men often fish offshore using nets, lines, and boats, while women tend to fish nearshore on foot, particularly harvesting benthic invertebrates with hand-held tools (Westerman and Benbow, 2013; Baker-Médard, 2024). Despite women’s substantial contributions, their labor remains underreported in national statistics and management plans (Baker-Médard, 2017; Chambon et al., 2024). Where gendered analyses have been conducted, findings show that women often have lower catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) than men, largely due to differences in gear type and fishing effort. However, in certain invertebrate fisheries, women’s CPUE is comparable to, or even exceeds, that of men (Kleiber et al., 2014b). A persistent lack of gender-disaggregated data limits the development of equitable and effective fisheries policies (Harper et al., 2020).

At the same time, regional variation in fishing practices, infrastructure, and habitat conditions shape catch composition and effort. In the north, fishers tend to operate with better access to motorized boats and benefit from stronger infrastructure, including better roads, more reliable electricity and proximity to tourism and export markets that support more diversified livelihoods (Gough et al., 2020; Maire et al., 2020). In contrast, many fishing communities in the southwest, such as those in Atsimo-Andrefana, are more geographically isolated, have inadequate infrastructure, and rely more heavily on small, non-motorized vessels and foot-based gleaning (Westerman and Benbow, 2013; Benbow et al., 2014). These contrasts illustrate how ecological conditions and infrastructure interact with social roles to shape fishing strategies and outcomes within Madagascar’s coastal systems. Although ecological indicators such as coral cover or substrate composition were not measured here, they likely differ between regions and help contextualize the observed variation in catch and fishing practices. Recognizing these linkages allows the study to situate regional differences in fishing outcomes within broader coupled dynamics without inferring direct causal feedbacks.

Research on catch in Madagascar has largely been region-specific, examining the effects of temporary octopus fishery closures in the southwest (Benbow et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2024; Wulfing et al., 2024), the impacts of marine reserves on coral reef assemblages in the northeast and northwest (Randrianarivo et al., 2022), gendered fishing participation in the southwest (Westerman and Benbow, 2013), gear efficiency in reef and nearshore fisheries in the northeast (Doukakis et al., 2007) and southwest (Davies et al., 2009; Ranaivomanana et al., 2023), and the influence of market access on fishing pressure and CPUE in the northwest (Maire et al., 2020) and southeast (Long et al., 2021). While these studies offer valuable insights, few have examined how gender, gear type, and regional context interact to shape catch across different ecological and social settings.

To address this gap, we integrate fisheries-dependent indicators (CPUE, gear efficiency) with human dimensions of fishing (gendered roles, gear preferences, and access to fishing grounds) to examine Madagascar’s coastal fisheries as a coupled natural and human system. We compare CPUE across two coastal regions of Madagascar, Diana in the north and Atsimo-Andrefana in the southwest, that differ in ecological conditions, gear use, and gendered fishing practices. We analyze how gender, gear types, and regional context influence CPUE. This analysis provides a quantitative baseline for future work tracking how coupled social and ecological dynamics in Madagascar’s small-scale fisheries evolve over time. We hypothesize that (1) CPUE will differ between regions due to differences in ecological conditions and fishing practices (Randrianarivo et al., 2022); (2) gear type will significantly influence CPUE, with active gears such as spearguns generally expected to have higher efficiency (Davies et al., 2009; Doukakis et al., 2007; Ranaivomanana et al., 2023); and (3) gendered fishing patterns will be reflected in CPUE, with women predominantly engaging in active harvesting (e.g., hand-held spears), and men using a mix of active (spearguns and hand-held spears) and passive (lines and nets) gear types (Westerman and Benbow, 2013; Kleiber et al., 2014b).

2 Methods

2.1 Study area and sampling strategy

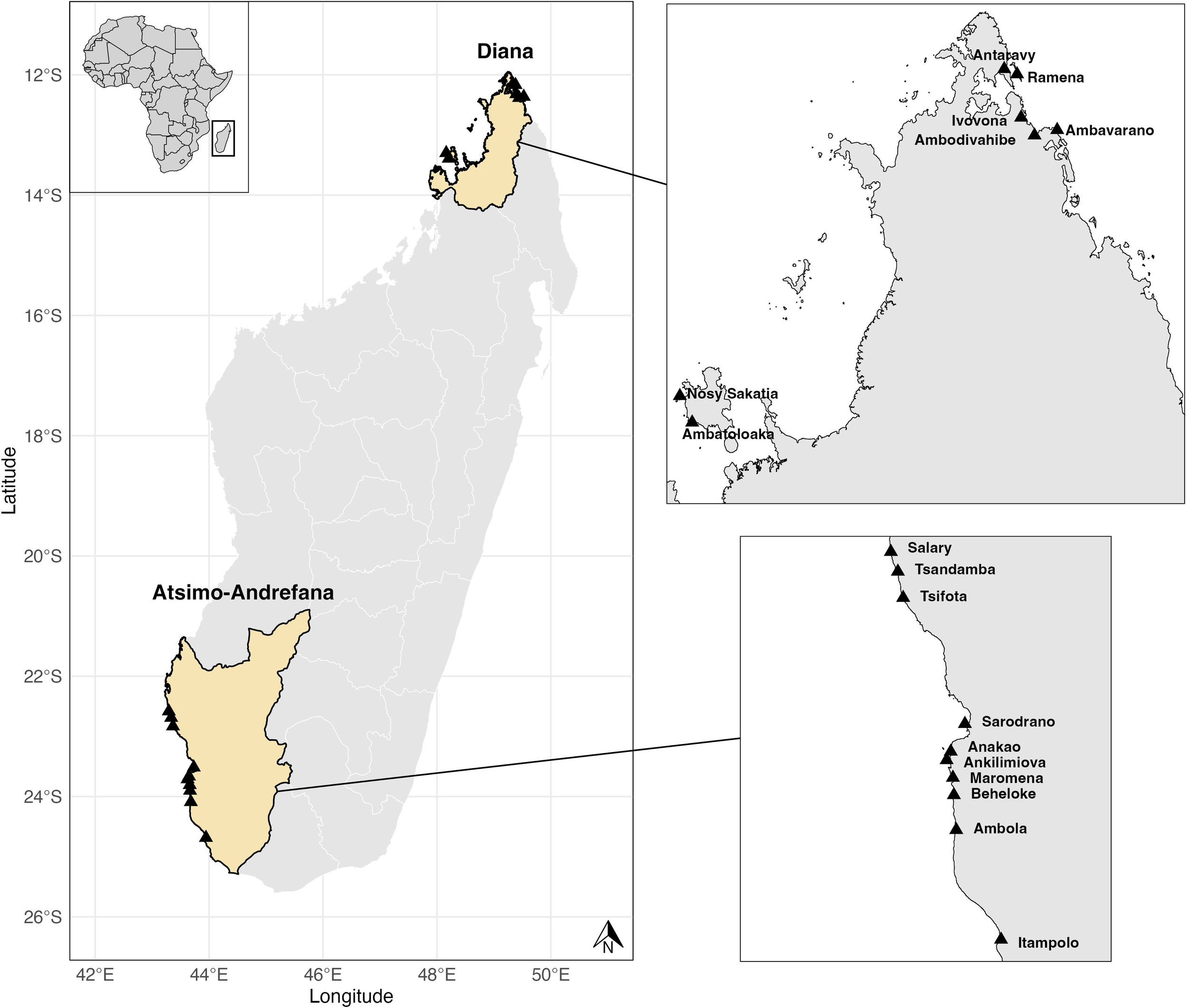

For this study, we used data collected by trained local fish collectors, covering 9,068 fishing trips across 17 fishing villages in two regions of Madagascar: Diana in the north and Atsimo-Andrefana in the southwest (Figure 1). Data was collected from January 2023 to July 2024 in Atsimo-Andrefana, and from July 2023 to July 2024 in Diana.

Figure 1

Study sites are shown across two regions: the Diana Region (North) and the Atsimo-Andrefana Region (Southwest). Inset maps provide zoomed views of village locations within each region. Source: Administrative boundaries were obtained from GADM (v4.1) and Natural Earth. Maps created using shape files from GADM. Licensed under (GADM v4.1 administrative boundaries for Madagascar and Natural Earth country boundaries).

Villages were selected to be representative of their respective coastal regions. Within each village, data collectors were chosen based on their established role as local fish collectors who regularly purchase or record catches from community fishers. We prioritized collectors who worked with the largest number of fishers in each village to ensure broad coverage of local fishing activity. While a few larger villages had two collectors, most villages had only one. As a result, our dataset represents a subset of total daily catch in larger villages, though it remains fairly comprehensive for smaller sites where only one collector operates.

We developed a digital survey using KoboCollect to systematically record fisheries harvest data in coastal Madagascar. The survey was designed in KoboToolbox and deployed on Android devices, enabling offline data collection in remote field sites. Structured to capture key variables such as gear type, species caught, catch volume (kilograms and number of individuals), and effort (e.g., number of fishers, time spent fishing), the form also included the specific harvest location. Local fish collectors were trained in survey administration and data entry protocols to ensure consistency and reliability across sites. Collectors recorded catch data twice per week on predetermined days. On each sampling day, they obtained data from every fisher they encountered, rather than from a systematic subset (e.g., every third fisher), to maximize sample completeness. In smaller villages with a single collector, this approach provided near-comprehensive coverage of all active fishers on those days. Although collectors typically approached or called over fishers who were not directly selling to them, some individuals landing farther down the beach were not reached. Consequently, a small subset of fishers—particularly those not selling catch through the local collector—are underrepresented in the dataset. This introduces a bias toward male fishers and catch destined for commercial sale or export, and an underrepresentation of women fishers and catch intended for home consumption.

For each village, we summarized temporal coverage and sampling intensity, including the first and last sampling dates, number of active collectors, total trips recorded, number of active months, and the median number of trips per month (Table 1). “Intensive sampling months” were defined as those within the top 20% of monthly trip counts for that village, ensuring that at least one month was included per site even for shorter time series. These periods correspond closely to peaks in monthly sampling effort shown in Supplementary Figure S2, which depicts the number of recorded trips per month for each village between January 2023 and July 2024. Additional contextual information for each village, including approximate population size and cold-chain export capacity, is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1

| Village | First date | Last date | Active months (n) | Trips (n) | Collectors (n) | Trips/month (median [IQR]) | Intensive sampling months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atsimo-Andrefana | |||||||

| Ambola | 10 Jan 2023 | 01 Jun 2024 | 13 | 206 | 8 | 13 [5–28] | Jul–Aug 2023, Oct 2023 |

| Anakao | 02 Feb 2023 | 01 Jul 2024 | 13 | 573 | 2 | 56 [20–70] | May 2023, Jul 2023, May–Jun 2024 |

| Ankilimiova | 09 Jan 2023 | 13 Jul 2024 | 16 | 967 | 1 | 62 [27–92] | Dec 2023, Feb 2024, Apr 2024, Jun 2024 |

| Beheloke | 21 Mar 2024 | 12 Jul 2024 | 5 | 131 | 1 | 25 [15–28] | May 2024 |

| Itampolo | 27 Feb 2023 | 09 Feb 2024 | 7 | 154 | 2 | 28 [2–33] | Dec 2023, Jan 2024 |

| Maromena | 05 Jun 2023 | 08 Jul 2024 | 6 | 56 | 3 | 4 [3–6] | May–Jun 2024 |

| Salary | 13 Jan 2023 | 24 Jul 2024 | 19 | 2098 | 4 | 109 [82–143] | May 2023, Apr–Jun 2024 |

| Sarodrano | 10 Jan 2023 | 13 Jul 2024 | 15 | 606 | 2 | 37 [30–52] | Jun–Jul 2023, May 2024 |

| Tsandamba | 19 Jan 2023 | 14 Jul 2024 | 19 | 2722 | 7 | 137 [127–168] | Apr–Jun 2023, Aug 2023 |

| Tsifota | 03 Apr 2023 | 03 Jul 2024 | 16 | 725 | 2 | 46 [32–60] | May–Jul 2023, May–Jun 2024 |

| Diana | |||||||

| Ambatoloaka | 24 Jul 2023 | 02 Oct 2023 | 3 | 18 | 2 | 8 [4–8] | Jul 2023 |

| Ambavarano | 01 Aug 2023 | 06 May 2024 | 10 | 323 | 4 | 26 [15–47] | Aug 2023, Dec 2023 |

| Ambodivahibe | 05 Aug 2023 | 08 Jul 2024 | 12 | 184 | 6 | 16 [11–19] | Feb 2024, May–Jun 2024 |

| Antaravy | 01 Feb 2024 | 30 Jun 2024 | 5 | 44 | 3 | 3 [2–7] | Feb 2024 |

| Ivovona | 30 Jan 2024 | 06 Jul 2024 | 7 | 205 | 2 | 25 [12–46] | Feb 2024, Apr 2024 |

| Nosy Sakatia | 23 Jul 2023 | 15 Oct 2023 | 4 | 14 | 2 | 3 [3–4] | Jul 2023 |

| Ramena | 01 Feb 2024 | 05 Jul 2024 | 6 | 42 | 2 | 8 [7–8] | Feb–Mar 2024, May–Jun 2024 |

Summary of fishing-trip sampling effort across villages in Atsimo-Andrefana and Diana regions, Madagascar, between January 2023 and July 2024.

The table reports the first and last sampling dates, number of months with active data collection, total trips and collectors per village, and the median number of trips per month with interquartile range (IQR). Intensive sampling months refer to months in which trip numbers ranked within the upper 20% for each village.

2.2 Gear types

To reduce complexity and ensure consistency, 13 original gear types were consolidated into four categories based on their primary fishing mechanism: lines, nets, spearguns, and hand-held spears. This grouping addressed inconsistencies in naming and classification across villages and regions, where the same gear was often referred to differently, or similar names described slightly different practices. Final groupings were verified using regional knowledge to reflect local fishing practices accurately. Lines included handlines and longlines. Nets included beach seines, ZZ nets, gill nets, handnets with handles, shark nets, simple nets, and dam blocks. Spearguns and hand-held spears were retained as separate categories due to distinct gear mechanics, target species, and gendered patterns of use across regions.

2.3 CPUE calculation

Catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) was calculated for each fishing trip as:

where CPUE is expressed in kilograms per fisher per hour (kg fisher-1 h-1). Trip duration was estimated from reported departure and return times and therefore includes travel, preparation, and other non-fishing activities. Consequently, CPUE based on total trip duration represents a conservative index of fishing efficiency. In Atsimo-Andrefana, some catch data, primarily for sea cucumbers, were reported without corresponding weights, requiring imputation for CPUE calculation. To address missing sea cucumber weights in Atsimo-Andrefana, we applied a single average weight derived from 124 individuals directly weighed in two villages north of Toliara: Tsifota (n=74) and Tsandamba (n=50). In Tsifota, the weighed samples included five locally identified species: Zanga dorolisy (n=3), Zanga fotitsetsake (n=16), Zanga jomaly (n=3), Zanga tarike (n=8), and Zanga tsonkena (n=44). In Tsandamba, eight species were recorded: Zanga fotitsetsake (n=10), Zanga foty (n=1), Zanga hebotse (n=1), Zanga jomaly (n=11), Zanga tarike (n=11), Zanga tongolo (n=2), Zanga tsonkena (n=13), and Zanga mbato (n=1). This pooled average of 216.8g was then used as a representative weight for imputing all unweighed sea cucumber records in the dataset. For all other taxa that may be missing weight data, average weights were calculated from trips with available weight data. These estimates were used to fill missing values, allowing for CPUE calculations while minimizing data loss.

Because many fishing trips involved multiple gears, and gear use was reported at the organism level (e.g., “fish,” “octopus”) rather than linked to individual species or their recorded weights, it was not possible to determine precisely how much of the observed or imputed biomass was captured by each gear. To approximate these proportions, we calculated, for each trip, the difference between the total observed (weighed) catch and the total catch after imputation, then distributed imputed weights proportionally among the gears used in that trip according to their relative catch shares in the dataset. This approach preserves total trip biomass while providing a conservative estimate of the contribution of imputed weights across region × gear combinations (Supplementary Table S4). Following initial data screening, we excluded 1,341 trips (12.8% of all reported) due to invalid, inconsistent or missing data entries. This included illogical time stamps, invalid village names, missing departure and return times, or species listed without corresponding catch quantities. We also removed 77 trips with unrealistic values (0.7% of all reported trips), such as fishing durations under one hour (0.17% of all trips) or total catch over 300 kg, based on ecological knowledge and field experience. In a few cases, mismatches between gear, organism, and reported weight likely due to entry error (e.g., 42 kg of shrimp from 12 individuals using a hand-held spear) also led to exclusion. These thresholds were established through visual inspection of the dataset and informed by observations of local fishing practices and constraints. Among the 10,486 initial fishing trips recorded in KoboToolbox, we retained 9,068 for our analyses (Supplementary Figure S1).

While we initially calculated gear-adjusted and gender-adjusted CPUE values to account for multi-gear and mixed-gender trips, these were not used in final analyses to avoid introducing assumptions about how effort and catch were distributed across gear types or fishers. Instead, CPUE analyses were restricted to single-gear fishing trips (which made up 86.6% of all trips) when comparing gear efficiency, and to single-gender trips (97.5% of all trips) when examining gendered differences in catch rates. This restriction likely results in conservative CPUE estimates, as multi-gear trips tended to yield higher catches than single-gear trips. Across all fishing trips, 92.9% were conducted by men only, 4.6% by women only, and 2.5% by mixed-gender groups. Gender composition was determined based on the total crew recorded per trip: ‘men-only’ and ‘women-only’ trips included only fishers of that gender, while ‘mixed-gender’ trips included both men and women. In the Diana region, women-only trips were recorded at only three of the seven study sites, Ivovona, Ambodivahibe, and Ambavarano, so gender-specific analyses for this region are constrained to these villages. Overall, 79.1% of trips involved a single fisher.

2.4 Data analysis

To evaluate regional variation in CPUE across Madagascar’s small-scale fisheries, we fit two generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Gamma error distribution, as CPUE values were continuous, strictly positive, and right skewed. CPUE was the response variable in both models. Both models used a log link and included gear type or gender, region, and their interaction as fixed effects. For the gear-based CPUE model, we used only single-gear fishing trips to isolate the effect of each gear type; for the gender-based CPUE model, we used only single-gender trips to ensure clear gender attribution. Model-predicted mean CPUE values were estimated using the emmeans package (Lenth, 2024), which calculates estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals, allowing for standardized comparisons across groups while accounting for unequal sample sizes and variability. Model diagnostics included checks for overdispersion using Pearson residuals, with values near one indicating acceptable dispersion, and inspection of residuals versus fitted values and quantile-quantile (QQ) plots of deviance residuals (Supplementary Figure S3). All analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2024). To account for potential non-independence of trips within villages and among data collectors, we re-fit both CPUE models as generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with a Gamma distribution and log link using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). Each model included a random intercept for Village to capture village-level clustering (ICC = 0.31 for the gear model; ICC = 0.24 for the gender model), and we additionally tested models including Collector ID as a second random intercept. Models were fit using the “bobyqa” optimizer, and clustering was quantified using intra-class correlation coefficients from the performance package (Lüdecke et al., 2021). In the gear model, the Collector term explained negligible variance (Var = 0.05 vs. 0.44 for Village) and did not substantially improve model fit (ΔAIC = 2.1). In the gender model, the Collector variance was larger (Var = 0.72 vs. 0.05 for Village) and reduced AIC (ΔAIC = 163) but produced near-identifiability warnings due to strong nesting of collectors within villages. Because collectors represent observer rather than ecological effects, the simpler Village-only model was retained for interpretation. Fixed-effect estimates and emmeans-based pairwise contrasts were compared between GLMs and GLMMs to confirm the robustness of all main conclusions (Supplementary Tables S9, S10).

We further conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of CPUE estimates to the method used for calculating fishing effort and to the inclusion of imputed weights. First, we re-fit both GLMs using only trips with fully weighed catches, excluding all imputed values (Supplementary Tables S5, S6). Because imputation occurred exclusively in Atsimo-Andrefana, results for Diana were identical between models. The direction and significance of regional and gear effects remained consistent, confirming that imputations did not alter conclusions. Second, we re-fit both models after excluding long trips (retaining only trips ≤ 7.7 h; median + 1 IQR), to assess whether including total trip duration (travel + fishing time) influenced CPUE estimates (Supplementary Tables S7, S8). The overall rank and significance of regional and gear effects were stable, with only minor, non-significant reordering among intermediate gears in Diana. In the gender model, a reversal occurred in Diana, with men showing slightly higher predicted CPUE than women under the short-trip filter, but this difference was not statistically significant. Although the short-trip and no-imputation models showed slightly improved fit and lower dispersion, these changes did not meaningfully alter the direction or strength of the main effects, supporting the robustness of results from the full models used for interpretation.

We also explored marine organism composition by gender, gear type, and region. For these analyses, we focused on single-gender trips to ensure clear gender attribution while retaining multi-gear trips, as each organism-gear association was analyzed separately. For multi-gear trips, CPUE was computed at the organism level and linked to the gear reported for that organism in the Kobo interview. To ensure meaningful comparisons, we included only combinations of organism × gear × gender × region that occurred in at least 10 fishing trips. Across the full dataset, 69 unique combinations were tested, of which 34 met this ≥10-trip threshold and were retained for analysis. This filtering step excluded sparse categories while maintaining representative coverage of the dominant fishing strategies within each region and gender group. CPUE was then aggregated by organism type and expressed as the proportion of total CPUE per gear type, within each gender and region.

Finally, we integrated complementary social survey data collected in 2023 and 2024 from 371 respondents across 17 villages. Via Kobo Toolbox, we surveyed local fishers regarding gear use, targeted species, participation in marine management, perceptions of ecological change, and strategies for adapting to those changes. 51.5% of respondents were men and 48.5% were women. Data were used descriptively to contextualize observed CPUE patterns and inform discussion of adaptive responses and management implications.

2.5 Declaration of generative AI technologies in the writing process

Parts of the manuscript originally written in French were translated and refined into English with the assistance of ChatGPT (GPT-4o, OpenAI). All translations were then reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final text.

3 Results

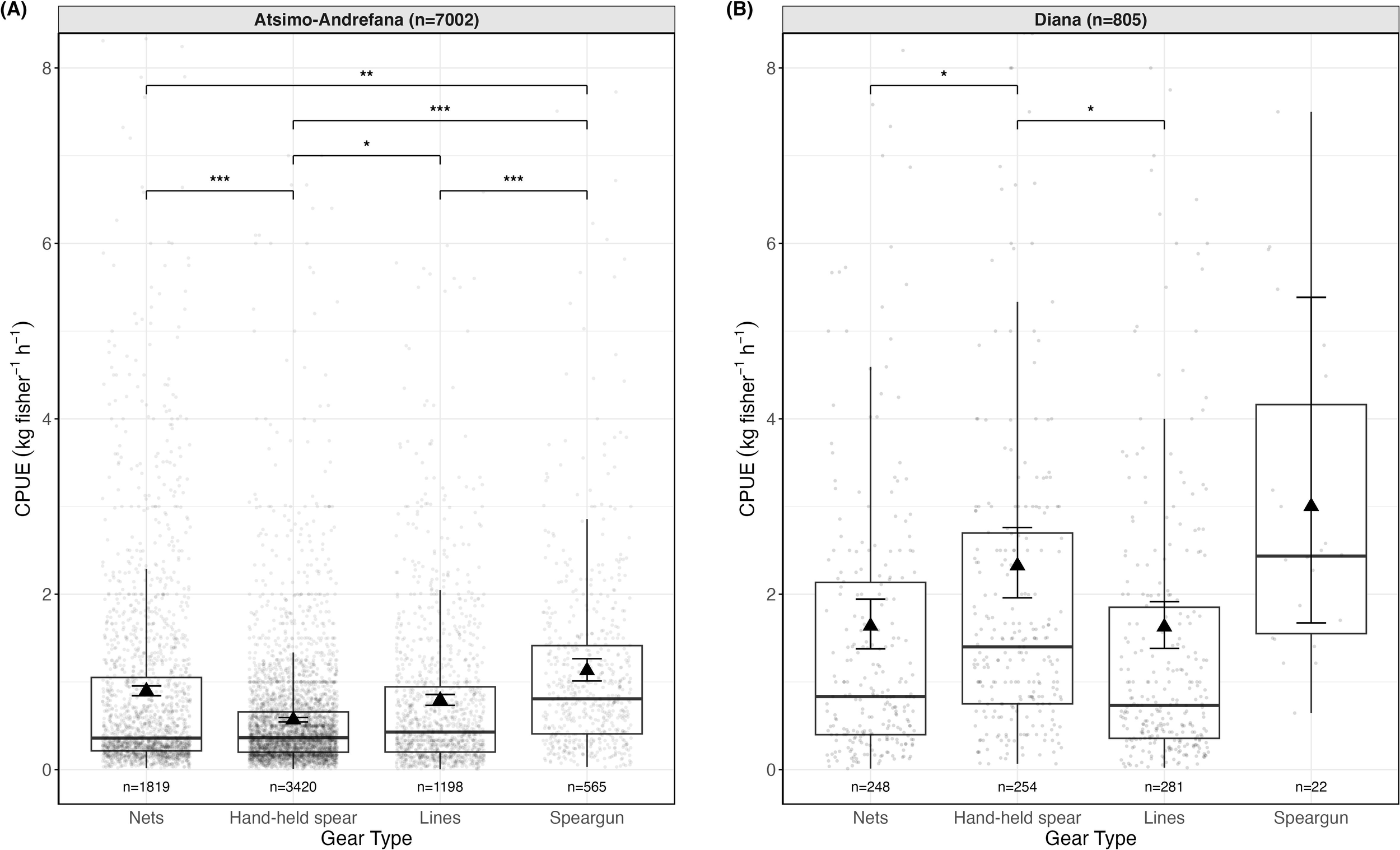

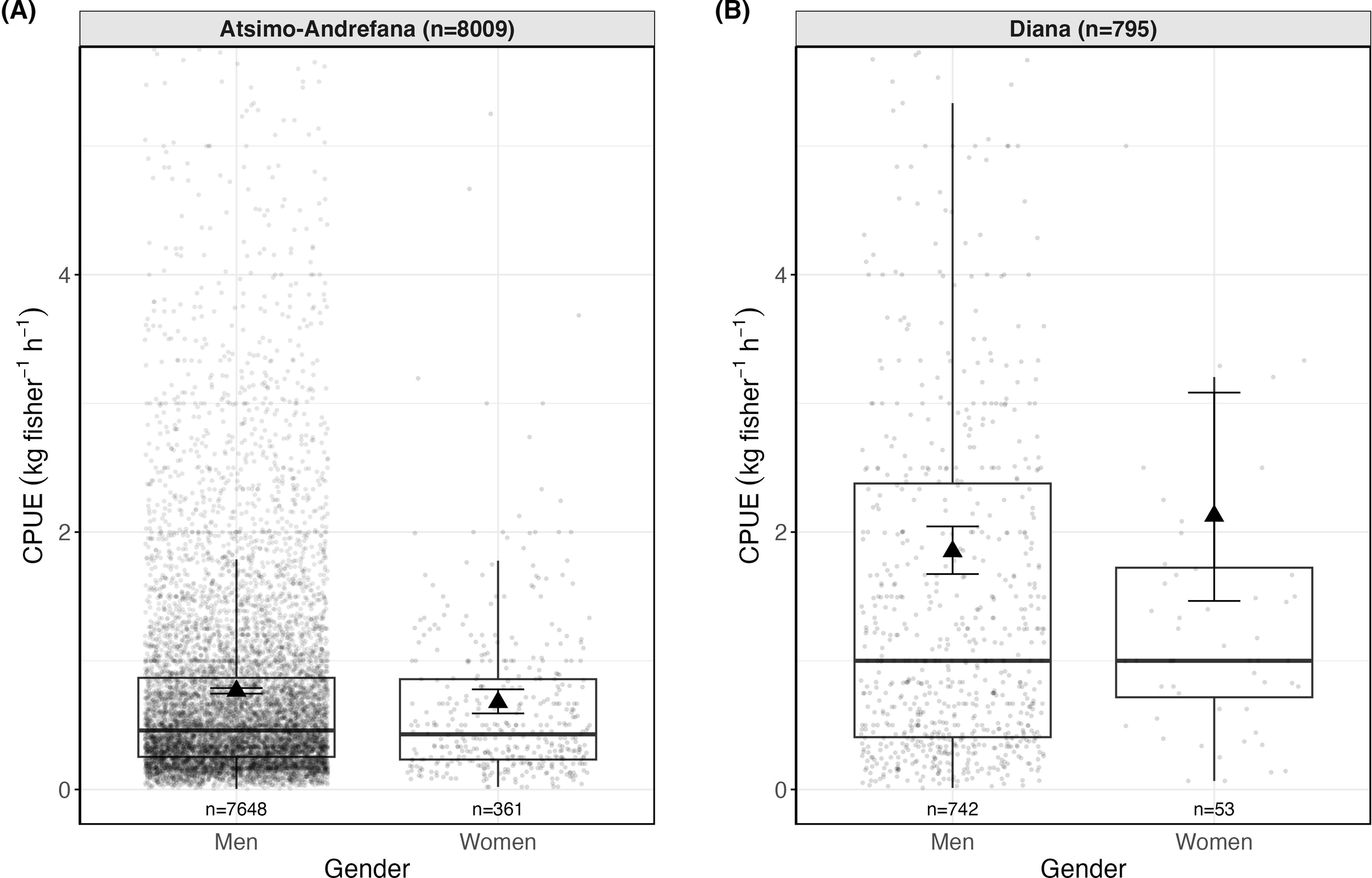

CPUE was consistently higher in the Diana region compared to Atsimo-Andrefana across all fishing trips. This regional difference was apparent regardless of gear type or gender (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2

Observed and model-predicted CPUE (kg fisher-1 h-1) by gear type and region for single-gear trips with CPUE > 0 in Atsimo-Andrefana (A) and Diana (B). Boxplots show observed CPUE values across trips. Each point represents the observed CPUE from an individual fishing trip. Triangles indicate model-predicted mean CPUE from a Gamma GLM with log link, and vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Numbers beneath each box indicate the number of unique trips per gear x region combination, and panel headers show total trips per region. Brackets with asterisks indicate statistically significant pairwise differences in predicted CPUE between gear types within each region (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 3

Observed and model-predicted CPUE (kg fisher-1 h-1) by gender and region for single-gender trips with CPUE > 0 in Atsimo-Andrefana (A) and Diana (B). Boxplots show observed CPUE values across trips. Each point represents the observed CPUE from an individual fishing trip. Triangles indicate model-predicted mean CPUE from a Gamma GLM with log link, and vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Numbers beneath each box indicate number of unique trips per gender x region combination, and panel headers show total trips per region.

3.1 Gear-specific patterns in CPUE

CPUE differed significantly by both gear type and region (Figure 2). In Atsimo-Andrefana (n=7002 trips), model-predicted mean CPUE ranged from 0.72 kg fisher-1 h-1 (95% CI 0.69–0.76, n=3420) for hand-held spears to 1.23 (95% CI 1.09–1.39, n=565) for spearguns, with nets (0.95 kg fisher-1 h-1; 95% CI 0.89–1.01, n=1819) and lines (0.83 kg fisher-1 h-1; 95% CI 0.77–0.91, n=1198) in between. Spearguns were therefore 1.7 times more efficient than hand-held spears and 1.3 times more efficient than lines (Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001 for both), corresponding to an additional 0.5–0.7 kg fisher-1 h-1 of catch on average. In Diana (n=805 trips), spearguns yielded the highest model-predicted mean CPUE at 3.00 kg fisher-1 h-1 (95% CI 1.62–5.56, n=22), followed by hand-held spears (2.33 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 1.94–2.79, n=254), nets (1.64 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 1.36–1.96, n=248), and lines (1.63 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 1.37–1.93, n=281). Although only the contrasts between hand-held spears and lines (p = 0.026) and between hand-held spears and nets (p = 0.037) were statistically significant, spearguns were 1.3× more efficient than hand-held spears and 1.8× more efficient than nets or lines, corresponding to an additional 0.7–1.4 kg fisher-1 h-1of catch on average.

Across regions, CPUE was consistently higher in Diana for all gears. For example, hand-held spears in Diana (2.33 kg fisher-1 h-1) yielded 3.2× higher CPUE than in Atsimo-Andrefana (0.72 kg fisher-1 h-1, p < 0.001). Lines showed a similar pattern, with their CPUE 1.95 times higher in Diana, (1.63 vs 0.83 kg fisher-1 h-1; ratio = 1.95), while nets and spearguns were 1.7× and 2.4× more efficient in Diana than in Atsimo-Andrefana, respectively (all p < 0.001).

Sensitivity analyses confirmed that these patterns were robust. Re-estimating the models using shorter trips only (Supplementary Table S7) and re-fitting them as hierarchical GLMMs with Village as a random effect (Supplementary Table S9) yielded nearly identical results. Likewise, excluding all imputed weights had no effect on model outcomes (Supplementary Table S5). Together, these tests confirm that our main conclusions are robust to assumptions about trip duration, clustering, and imputation.

3.2 Gender-specific patterns in CPUE

Men accounted for the majority of recorded fishing trips in both regions (Supplementary Table S2). Women’s trips were generally shorter in duration (mean 4.7 h in Atsimo-Andrefana and 6.1 h in Diana) than those of men (7.9 h and 10.3 h, respectively). Women’s median CPUE was comparable to or slightly higher than men’s within each region (Supplementary Table S2).

In Diana (n=795 trips), women had a higher model-predicted mean CPUE (2.13 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 1.47–3.08, n=53) than men (1.85 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 1.67–2.04, n=742) (Figure 3). This difference was not statistically significant (ratio = 1.15; Tukey-adjusted p = 0.48). The wide confidence intervals indicate uncertainty due to the smaller number of women-only trips (n=53 vs. 742 men-only). In Atsimo-Andrefana (n=8009 trips), men recorded slightly higher mean CPUE (0.77 kg fisher-1 h-1, 95% CI 0.75–0.79, n=7648) than women (0.68 kg fisher-1 h-1, 0.59–0.78, n=361). Men’s CPUE was 1.13× higher (p = 0.09), corresponding to a small difference of 0.1 kg fisher-1 h-1, but again this was not significant.

Across regions, both men and women in Diana showed significantly higher CPUE than their counterparts in Atsimo-Andrefana. Men’s CPUE was 2.4× higher in Diana (1.85 vs. 0.77 kg fisher-1 h-1; p < 0.001) and women’s was 3.1× higher (2.13 vs. 0.68; p < 0.001), equivalent to a difference of 1–1.5 kg fisher-1 h-1 on average between regions.

Sensitivity analyses confirmed that these patterns were robust. When re-estimating the model using shorter trips only, predicted CPUE values increased slightly for both genders, and the direction of the gender effect in Diana reversed (men > women), but this difference remained statistically non-significant (Supplementary Table S8). Re-fitting the model as a hierarchical GLMM with Village as a random intercept produced nearly identical fixed-effect estimates and emmeans-based predictions (Supplementary Table S10). Likewise, excluding all imputed weights had no effect on model outcomes (Supplementary Table S6).

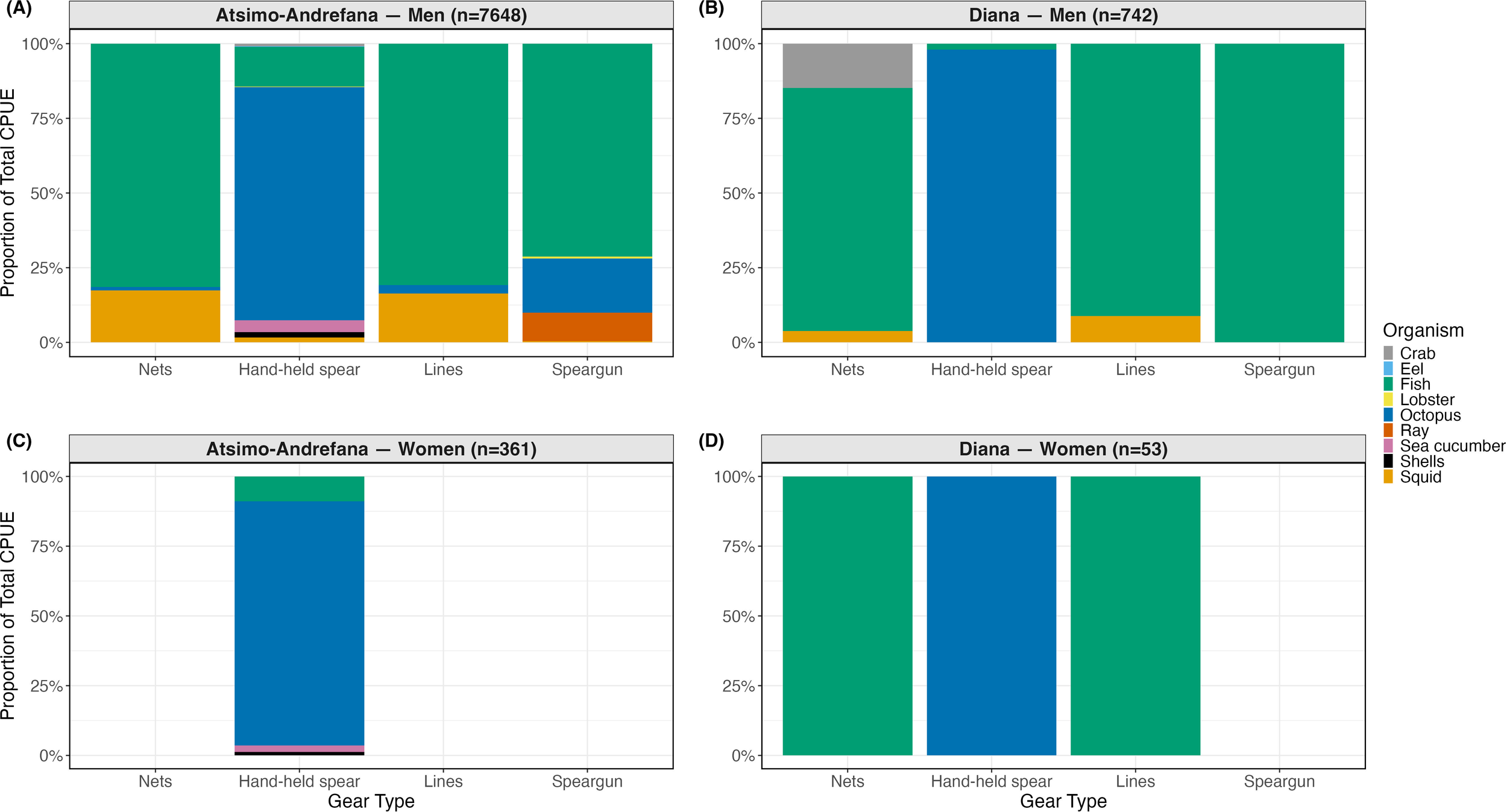

3.3 Regional catch composition by gear and gender

Catch composition varied strongly across gear types, genders, and regions (Figure 4, Supplementary Tables S11, S12). To ensure that comparisons were based on reliable sample sizes, only gear × gender × region × organism combinations represented by at least ten fishing trips were included in the analysis and visualization; combinations with fewer than ten trips were omitted.

Figure 4

Observed proportional contribution of organism types to total CPUE (kg fisher-1 h-1) by gear type, gender, and region, based on single-gender fishing. Panels (A–D) show patterns for (A) Atsimo-Andrefana – Men, (B) Diana – Men, (C) Atsimo-Andrefana – Women, and (D) Diana – Women. This figure represents the subset of 8,804 total single-gender trips with non-zero CPUE and complete information on region, gear, and organism type. Panel headers show number of total trips per region x gender combination. Organism types are shown only if they occurred in at least 10 fishing trips within a given gear × gender × region combination. Multi-gear trips were retained, as CPUE values were calculated separately for each organism and linked to their associated gear. A total of 69 organism × gear × gender × region combinations were tested, of which 34 combinations met the ≥10-trip threshold and are displayed.

In Diana, observed catch data showed that men’s trips using nets, lines, and spearguns consisted overwhelmingly of fish (81.3%, 91.2%, and 100%, respectively). Observed median CPUEs for these gears ranged from 0.82 to 2.42 kg fisher-1 h-1 (Supplementary Table S11). Women’s line and net fishing also yielded exclusively fish (100%), with similar observed median CPUEs of 1.00 and 1.18 kg fisher-1 h-1, respectively. For hand-held spears, women harvested octopus exclusively (100%), while men’s catches were also overwhelmingly octopus (98%), with nearly identical median CPUEs of 1.49 and 1.50.

In Atsimo-Andrefana, catch composition was more taxonomically diverse (Supplementary Table S12). Among men, hand-held spears yielded octopus (78.1%), fish (13.4%), sea cucumbers (3.9%), and squid (1.6%). Lines and nets were again fish-dominated (80.8% and 81.4%) but also included squid (16.4% and 17.4%). Women using hand-held spears similarly targeted octopus (87.5%), with smaller contributions from sea cucumbers (2.3%).

Despite these gendered patterns, Wilcoxon tests revealed only one statistically significant difference: in Atsimo-Andrefana, men using hand-held spears had significantly higher observed median CPUEs for sea cucumbers than women (p = 0.0013) (Supplementary Tables S11, S12). No other significant gender differences in CPUE were found for other organism–gear combinations after filtering out low-frequency combinations (<10 trips).

In Diana, men most often used lines (36% of trips) and hand-held spears (31%), and nets (29%) while women primarily used nets (40%) and hand-held spears (38%). In Atsimo-Andrefana, 46% of men’s trips involved hand-held spears and 22% used spearguns, whereas 93% of women’s trips used hand-held spears. While men used all four gear types across both regions, women’s fishing was heavily focused on hand-held spear use, particularly in Atsimo-Andrefana (Supplementary Table S2).

Although our analysis did not display any women using nets or lines in Atsimo-Andrefana, this reflects the filtering criteria applied for Figure 4 (only organism types harvested in ≥10 trips per gear × gender × region combination). Such trips were recorded in the dataset, but in low numbers. Field observations and local knowledge suggest that while some women do fish with nets and lines in this region, these cases are less frequent compared to spear fishing.

4 Discussion

By examining regional patterns in catch, we were able to identify context-specific drivers of fishing effort and catch composition. These patterns reflect the coupled nature of Madagascar’s small-scale fisheries, where ecological conditions influence fishing strategies, gear performance, and target organisms, while human decisions feed back to shape resource availability, habitat quality, and governance outcomes. Recognizing these reciprocal dynamics is crucial for informing adaptive management strategies that reflect ecological and social realities, rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions. Specifically, regional comparisons allow us to explore how gendered fishing roles and gear efficiency vary across distinct coastal settings.

4.1 Regional differences in CPUE

CPUE was significantly higher in the Diana region than in the Atsimo-Andrefana region, across gear types and gender groups (Figures 2, 3). These patterns are consistent with differences in reef condition, habitat complexity, and species availability between regions. Coral reefs in the southwest are considered in relatively poor ecological condition, characterized by low coral diversity and a dominance of algae (Gough et al., 2009; McClanahan et al., 2009; Randrianarivo et al., 2022; Botosoamananto et al., 2024). Fringing reefs in the region support lower standing stocks of fish, likely reflecting their accessibility and thus higher fishing pressure, combined with the impacts of warmer water and recurring bleaching events due to climate change (Bruggemann et al., 2012; McClanahan et al., 2009; Weiskopf et al., 2021). The Grand Récif of Toliara in the southwest, for instance, has experienced extensive coral habitat loss, with an estimated 65% decline on the outer reef flat (Andréfouët et al., 2013). Similarly, in the Andavadoaka region of southwest Madagascar, herbivorous fish biomass and abundance declined significantly with proximity to fishing villages, reflecting the combined impacts of fishing pressure and reef degradation (Vincent et al., 2011). In contrast, Madagascar’s northern coast supports healthier coral assemblages, with greater coral diversity, habitat complexity, and fish biomass (Obura and Oliver, 2009; Randrianarivo et al., 2022; Harding et al., 2006). Although our study did not include independent ecological sampling, these previously documented differences in reef condition provide a plausible ecological context for the lower CPUE observed in Atsimo-Andrefana. These regional contrasts are also shaped by broader patterns of fisher mobility. Seasonal migrations from Atsimo-Andrefana toward the north-western coast have been documented among Vezo fishers seeking more productive fishing grounds as nearshore resources decline (Cripps and Gardner, 2016). Although these movements do not typically extend as far north as our Diana study sites, they highlight the growing connectivity among Madagascar’s coastal fisheries and the need for management approaches that account for mobility and shifting fishing pressure along the western coast.

4.2 Gear-specific drivers of catch composition

The Diana region exhibited consistently higher CPUE values across gear types than Atsimo-Andrefana, with particularly strong differences observed for selective gears such as spearguns and hand-held spears (Figure 2). In contrast, CPUE in Atsimo-Andrefana was lower and relatively uniform across gears. These patterns are consistent with a combination of ecological and socio-economic factors. Selective gears perform best in favorable environmental conditions such as high water clarity, complex reefs, and high fish biomass. The more degraded reef structures and reduced fish biomass in the southwest may reduce gear performance (Harding et al., 2006; Brenier et al., 2011; McClanahan et al., 2009). Access to equipment likely also contributes to the regional differences. Fishers in Diana more often use commercially manufactured spearguns and motorized boats, whereas those in Atsimo-Andrefana frequently rely on locally made, lower-efficiency gear, which may affect catch efficiency. The higher CPUE observed for spearguns in Diana may reflect both more favorable reef conditions and access to more effective gear. However, given the small number of speargun-only trips in our dataset (n=22 in Diana), this result should be interpreted cautiously.

Gear type also strongly influenced catch composition, with clear patterns emerging across regions (Figure 4). Hand-held spears were primarily used for invertebrates such as octopus, sea cucumber and squid, while spearguns, lines, and nets more often targeted fish. These associations reflect ecological specialization: hand-held spears are well-suited for harvesting benthic, cryptic species in shallow reef flats (Benbow et al., 2014), whereas spearguns are better suited for targeting larger, mobile fish in clear water (Pavlowich and Kapuscinski, 2017). Nets, although treated as a single category in this study, span a range of designs and selectivity levels, but are generally effective for catching schooling species. These results align with studies showing that gear type strongly influences catch composition, size structure, and the resulting ecological impacts (McClanahan and Mangi, 2004).

However, catch composition within each gear type varied markedly between regions. In Atsimo-Andrefana, hand-held spear users harvested a broader range of invertebrates, including octopus, squid, sea cucumbers, lobsters, and shells, whereas in Diana, this gear was used almost exclusively to catch octopus. This broader range in the southwest likely reflects both ecological and economic drivers. Sea cucumbers and octopus are both important export commodities: Madagascar is one of the world’s largest sea cucumber exporters (Rothamel et al., 2023), and octopus fisheries contribute approximately 70% of the value of commercial marine resources in the southwest (Raberinary and Andrisoa, 2024). In Diana, tourism likely favors the targeting of larger fish, while alternative income from cash crops may reduce incentives to harvest lower-value invertebrate species. These market dynamics suggest that fishers in the southwest may diversify their invertebrate harvests in response to both local availability and economic incentives. Exploring how CPUE patterns align with species prices could yield valuable insights into these dynamics and offers an opportunity for future research.

Our results follow the same general pattern as Davies et al. (2009), who found that spears had the lowest catch per fisher compared to beach seines, nets, and lines, although their study reported catch per fisher rather than effort-standardized CPUE. However, their analysis focused predominantly on fish catches and excluded invertebrates such as octopus, which constituted a major component of hand-held spear harvests in our dataset across both regions. Additionally, the fifteen-year difference between studies may also reflect changes in resource availability and a potential trophic shift in what is targeted and harvested (Essington et al., 2006).

Shifts in policy and fishery pressure over the past 15 years may also have contributed to changes in gear use and harvesting strategies. In particular, the use of beach seines, previously a common gear type in nearshore areas, has been the focus of conservation campaigns and formally banned since 2015 due to their destructive impact on juvenile fish and benthic habitats (Ranaivomanana et al., 2023). This ban likely led some fishers to adopt alternative gears such as lines or nets to target finfish. These transitions may reflect the influence of regulatory changes on fishing practices and gear composition, contributing to the diversification observed across Madagascar’s coastal regions. Finally, while lines, nets, and spearguns were generally used to target fish, their catch composition varied regionally. In Diana, these gears were strongly specialized toward fish, consistent with healthier reef conditions and greater fish availability. In contrast, in Atsimo-Andrefana, lines and nets were used more flexibly, with some capturing squid as well. This shift likely reflects lower standing stocks of reef fish in the southwest (Bruggemann et al., 2012) and ecosystem changes associated with reef degradation, which tend to favor opportunistic species like squid (Bellwood et al., 2004). Therefore, the greater reliance on squid in the southwest may represent an adaptive harvest strategy in response to ecological change, with fishers adjusting their practices to match shifting species assemblages.

These findings highlight the importance of understanding how gear use interacts with ecological conditions to shape catch composition. Incorporating gear-specific and regionally disaggregated data into fisheries monitoring can help managers design more nuanced policies, such as targeted gear regulations, spatial closures, or species-specific harvest controls, that account for local ecological realities and fishing practices. As fishing pressures and ecological conditions continue to shift, such context-sensitive management will be essential for balancing sustainability goals with the livelihoods of diverse fishing communities.

4.3 Gender differences in fishing outcomes

Gendered differences in fishing outcomes were relatively modest overall but varied by region and gear type. In the Diana Region, women had a slightly higher, though not significant model-predicted mean CPUE than men (Figure 3). This is despite spending fewer hours fishing per trip (6.1 vs. 10.3 hours; Supplementary Table S2). Rather than indicating lower effort, this may indicate greater efficiency among women, likely driven by shorter, targeted trips focused on high-yield species. Women’s catches in Diana were narrowly specialized, entirely composed of fish (71%) and octopus (29%), two organisms with higher observed median CPUEs in Diana than in Atsimo-Andrefana (Supplementary Table S2). Their gear use was also relatively streamlined, primarily relying on hand-held spears and lines, with no speargun use. In contrast, men in Diana used a wider variety of gears and caught a more diverse range of taxa, potentially reducing overall efficiency compared to the more specialized approach taken by women.

Gender also shapes how fishers access fishing grounds. Our social survey data revealed that in both regions, women were more likely to fish on foot, while men more often relied on sailboats and paddleboats, and in Diana, motorboats (Supplementary Table S13). These differences in mobility influence habitat access. Women predominantly fished in nearshore environments such as beaches, intertidal zones, reef flats, and reef crests—with the reef crest being the most frequently reported habitat by women in the southwest. Men also used reef-associated habitats, but more commonly fished in deeper waters (Supplementary Table S13). These differences in access to productive fishing grounds help explain observed gender differences in catch composition and CPUE and highlight the importance of considering access constraints in management planning.

Building on these differences in habitat use, gendered patterns in Atsimo-Andrefana reveal a distinct dynamic. Despite lower CPUE overall, women exhibited greater taxonomic diversification in their catches than women in Diana, particularly through their use of hand-held spears to harvest a wide range of invertebrates, including sea cucumbers, lobsters, octopus, and squid (Figure 4). This aligns with prior studies showing that women often specialize in cryptic, benthic taxa accessible in reef flats and intertidal zones (Fröcklin et al., 2014).

Our results also revealed strong participation of men in hand-held spear octopus fishing in the southwest. The high proportion of men using hand-held spears to harvest octopus (78.1%) suggests that this fishery is no longer dominated by women, aligning with observations of growing participation by men in nearshore octopus harvesting (Langley, 2006; Rocliffe and Harris, 2016). This shift may be driven by wealth (e.g., access to boats and gear) (Baker-Médard et al., 2021), changing market incentives, and campaigns by conservation organizations to orient fishers towards harvesting species that respond well to temporary rotational marine reserves (Benbow et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2024; Wulfing et al., 2024). Historically, gleaning was practiced by both men and women, and participation has evolved in response to economic and ecological pressures (Langley, 2006; Rocliffe and Harris, 2016).

In our dataset, sea cucumbers were harvested slightly more frequently by men than by women in Atsimo-Andrefana (Figure 4), a pattern that may partly reflect sampling bias, as collectors sometimes prioritized interviewing fishers involved in export-oriented fisheries, particularly men, and catch taken directly home, bypassing collectors, were sometimes absent from our dataset. This underrepresentation of women fishers likely reduced the recorded contribution of invertebrates they frequently harvest.

Sea cucumbers were harvested more frequently by fishers in Atsimo-Andrefana than in Diana, consistent with earlier research documenting the commercial importance of sea cucumber fisheries in the southwest, where favorable reef flats and high market demand have supported extensive harvest (McVean et al., 2005; Rothamel et al., 2023). In Diana, while large, high-value sea cucumbers may be occasionally targeted by specialized fishers, they tend to occur in deeper habitats that are less accessible due to the limited fringing reef. Moreover, in many northern sites, fishers have access to alternative livelihoods and tend to discard smaller, low-value sea cucumber species, choosing to retain only the largest individuals. Fishers in the southwest rely almost exclusively on the sea for their income and food security, whereas fishers in the north have historically maintained and continue to have more diversified livelihoods, reducing dependence on fishing (Davies et al., 2009; Baker-Médard et al., 2021). This regional difference highlights how both ecological availability and economic incentives shape fishing strategies. However, sea cucumber populations in Madagascar have faced increasing harvest pressures, especially in the southwest, leading to localized stock declines and raising concerns about the sustainability of invertebrate-focused fisheries (Rothamel et al., 2023). As high-value benthic resources become depleted, fishers—particularly women, who often rely on these taxa—may be driven to diversify their catches, shifting effort toward other benthic or opportunistic species to sustain household incomes.

These findings highlight how gendered fishing strategies are shaped not just by ecological conditions but also by access to boats, gear, and fishing grounds. Invertebrate catches, which are central to many women’s livelihoods, have historically been underreported in Madagascar’s official statistics, with studies estimating underreporting rates of up to 40% in recent decades (Le Manach et al., 2011). Better inclusion of small-scale and invertebrate fisheries is essential for ensuring equitable representation in management frameworks and for the sustainable use of coastal resources. Improving the inclusion of small-scale and invertebrate fisheries in data collection is essential not only for equitable representation in management frameworks but also for the sustainable use of coastal resources. Without accounting for the full extent of these contributions, management strategies may fail to detect early signs of resource depletion or introduce regulations that effectively protect these habitats.

Inclusive conservation strategies must recognize these gendered dynamics. Marine Protected Areas and Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs) should explicitly incorporate the roles, needs, and constraints of women fishers. Supporting access to selective, low-impact gear and recognizing women’s knowledge and labor is essential to ensure both social equity and ecological sustainability. As Madagascar expands its MPA network, integrating gender and regional differences will be critical for effective, community-led fisheries governance.

4.4 Limitations and future research

While this study highlighted important regional and gendered patterns in catch composition and gear use, several limitations should be acknowledged. Uneven sampling effort across regions and gender groups may have influenced some comparisons, particularly in the Diana region and for women overall, where sample sizes were significantly smaller. Our harvest data collection started earlier in the Atsimo-Andrefana region of Madagascar, and there were overall more trips in this region as well. Additionally, to ensure consistency in analysis, fishing methods were grouped into broad gear categories. However, this may have masked finer distinctions in efficiency and selectivity between gear subtypes—for example, between gill nets and simple nets. In some cases, catch weights—particularly for sea cucumbers—were not recorded and had to be estimated using average species weights. This introduced uncertainty, as individual wet sea cucumber weight can vary widely, from roughly 250 grams to over 2,500 grams depending on the species (Purcell et al., 2023; Rothamel et al., 2023). CPUE values were calculated using total trip duration, which included travel and preparation time, rather than isolating only active fishing effort. This approach led to a modest underestimation of true fishing productivity, particularly for fishers traveling longer distances or engaging in multiple fishing phases. Sensitivity analyses using only short-duration trips (≤ median + 1 IQR) showed that CPUE values were slightly higher overall and that the relative differences between regions, gears, and genders remained consistent, with only small, non-significant shifts in some comparisons. Therefore, the bias introduced by using total trip time is minor and does not significantly alter the study’s main conclusions.

Another challenge stemmed from the collaborative nature of fishing in many communities. Catch data was often reported at the group level, and in some cases, gear use was attributed to the individual surveyed, even if other crew members contributed using different gear types. This made it difficult to precisely link specific gear to specific catch portions or individual fishers and may bias comparisons of gear efficiency. Finally, although data collectors received standardized training, some biases may have shaped who was interviewed. In certain cases, collectors prioritized fishers involved in export, particularly men, resulting in underrepresentation of women and the invertebrates they frequently harvest. This reflects both methodological bias and underlying structural patterns: across villages, there were fewer women actively engaged in fishing than men, particularly in offshore or motorized fisheries. As a result, the ecological importance of taxa targeted by women, such as sea urchins, shells, and algae, was underestimated in our dataset. For example, in Atsimo-Andrefana, 28% of women cited urchins among their top two harvested organisms in our social survey (Supplementary Table S14), despite the near absence of urchins in our recorded catch data. Women fishers may thus head from shore to home, bypassing our local collectors. Future research could conduct targeted surveys specifically on women’s catch to help address this deficit in the data.

Future research could build on this study by examining how fishers perceive and engage with marine conservation efforts, particularly marine reserves. Complementary social data collected at the village level will allow for analysis of fisher participation in decision-making, enforcement, and monitoring, helping clarify the social and institutional drivers behind regional differences in fishing outcomes. Additionally, future work could disaggregate catch data to the species level to assess species-specific selectivity, fisher specialization, and potential shifts in target taxa under changing environmental conditions. Analyzing species-level catch trends over time could also reveal subtle shifts in composition that are masked at broader taxonomic levels, offering insight into how fishers adapt to habitat degradation or evolving demand. In addition, linking CPUE and catch composition data with independent ecological surveys, such as baited remote underwater videos (BRUVs) and benthic quadrats, would enable a more robust understanding of how habitat structure and reef condition influence fishing patterns and harvest outcomes. Finally, future work could also extend this approach along the western coastline to examine CPUE patterns in relation to fisher mobility and migration dynamics, identifying potential fishery hotspots and management priorities across regions.

5 Conclusion

This study reveals how regional and gendered differences in fishing outcomes across a country are shaped by the relationship between ecological conditions, gear access, and social roles. Higher CPUE in the northern region was consistent with healthier reef systems and greater access to efficient gear, while fishers in the south operated in relatively more degraded habitats with simpler equipment, leading to overall lower productivity and greater diversification of target organisms. Although ecological degradation cannot be directly confirmed from our dataset, these patterns align with previous studies documenting lower coral cover and fish biomass in the southwest. Importantly, fishers are not passive observers of change; they demonstrate resilience by adjusting their fishing strategies in response to shifting ecological conditions and resource availability.

Recognizing these patterns is critical for designing management strategies that reflect both environmental realities and social diversity. Underrepresenting women’s fishing activities is not just a matter of equity—it can lead to the underestimation of total harvest pressure on potentially vulnerable benthic organisms such as octopus and sea cucumbers. Strengthening inclusive, place-based governance that accounts for both ecological context and local knowledge is essential to sustaining small-scale fisheries in Madagascar and beyond.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://github.com/QuantMarineEcoLab/madagascar-ssf-gender-region.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Middlebury College Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EW: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (grants #2409030 and #1923707).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the collectors in Madagascar and the fishers that made this work possible. This work would also not be possible without the coordination and terrific help of Bemahafaly Randriamanantsoa, Ravelo Vololonavalona, Charlotte Nagnisaha Lahiko, Miza Razafindravelo, Herdinand Haidodiado, Anirà Rakotonirina, Yvonne Mariette, Hortensia Rasoanandrasana, Frederic Sambison, and Abdou M’tsounga. We are also grateful to WCS, WWF, CI and MNP for their accommodation and logistical support. Additionally, we would also like to thank Ruscena Wiederholt, Joanna Gyory, and members of the Quantitative Marine Ecology Lab at UNH for their input on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used Generative AI (ChatGPT, version GPT-4o, OpenAI) to assist with the translation and refinement of selected sections from French into English. All text was then reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1684707/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Andréfouët S. Guillaume M. M. M. Delval A. Rasoamanendrika F. M. A. Blanchot J. Bruggemann J. H. (2013). Fifty years of changes in reef flat habitats of the Grand Récif of Toliara (SW Madagascar) and the impact of gleaning. Coral Reefs32, 757–768. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1026-0

2

Bahri T. Vasconcellos M. Welch D. J. Johnson J. Perry R. I. Ma X. et al . (2021). “ Adaptive management of fisheries in response to climate change,” in FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 667 ( FAO, Rome). doi: 10.4060/cb3095en

3

Baker-Médard M. (2017). Gendering marine conservation: the politics of marine protected areas and fisheries access. Soc. Natural Resour.30, 723–737. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1257078

4

Baker-Médard M. (2024). Feminist conservation: Politics and power in Madagascar’s marine commons (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press).

5

Baker-Médard M. Gantt C. White E. R. (2021). Classed conservation: Socio-economic drivers of participation in marine resource management. Environ. Sci. Policy124, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.06.007

6

Barnes-Mauthe M. Oleson K. L. L. Zafindrasilivonona B. (2013). The total economic value of small-scale fisheries with a characterization of post-landing trends: An application in Madagascar with global relevance. Fisheries Res.147, 175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2013.05.011

7

Bates D. Maechler M. Bolker B. Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Software67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

8

Bellwood D. R. Hughes T. P. Folke C. Nyström M. (2004). Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature429, 827–833. doi: 10.1038/nature02691

9

Benbow S. Humber F. Oliver T. Oleson K. Raberinary D. Nadon M. et al . (2014). Lessons learnt from experimental temporary octopus fishing closures in south-west Madagascar: Benefits of concurrent closures. Afr. J. Mar. Sci.36, 31–37. doi: 10.2989/1814232X.2014.893256

10

Béné C. (2006). “ Small-scale fisheries: assessing their contribution to rural livelihoods in developing countries,” in FAO Fisheries Circular. No. 1008 (Rome: FAO), 46p.

11

Botosoamananto R. L. Todinanahary G. Gasimandova L. M. Randrianarivo M. Guilhaumon F. Penin L. et al . (2024). Coral recruitment in the Toliara region of southwest Madagascar: Spatio-temporal variability and implications for reef conservation. Mar. Ecol.45, e12794. doi: 10.1111/maec.12794

12

Brenier A. Ferraris J. Mahafina J. (2011). Participatory assessment of the Toliara Bay reef fishery, southwest Madagascar. Madagascar Conserv. Dev.6, 60–67. doi: 10.4314/mcd.v6i2.4

13

Bruggemann J. H. Rodier M. Guillaume M. M. M. Andréfouët S. Arfi R. Cinner J. E. et al . (2012). Wicked social-ecological problems forcing unprecedented change on the latitudinal margins of coral reefs: the case of southwest Madagascar. Ecol. Soc.17. doi: 10.5751/ES-05300-170447

14

Chambon M. Miñarro S. Alvarez Fernandez S. Porcher V. Reyes-Garcia V. Tonalli Drouet H. et al . (2024). A synthesis of women’s participation in small-scale fisheries management: Why women’s voices matter. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries34, 43–63. doi: 10.1007/s11160-023-09806-2

15

Cinner J. E. McClanahan T. R. Daw T. M. Graham N. A. J. Maina J. Wilson S. K. et al . (2009). Linking social and ecological systems to sustain coral reef fisheries. Curr. Biol.19, 206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.055

16

Cripps G. Gardner C. J. (2016). Human migration and marine protected areas: Insights from Vezo fishers Madagascar. Geoforum74, 49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.010

17

Davies T. E. Beanjara N. Tregenza T. (2009). A socio-economic perspective on gear-based management in an artisanal fishery in south-west Madagascar. Fisheries Manage. Ecol.16, 279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2009.00665.x

18

Doukakis P. Jonahson M. Ramahery V. De Dieu Randriamanantsoa B. J. Harding S. (2007). Traditional fisheries of Antongil Bay, Madagascar. Western Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci.6, 175–181. doi: 10.4314/wiojms.v6i2.48237

19

Essington T. E. Beaudreau A. H. Wiedenmann J. (2006). Fishing through marine food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.103, 3171–3175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510964103

20

FAO (2022). “ The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2022,” in Towards Blue Transformation ( FAO, Rome). doi: 10.4060/cc0461en

21

Farquhar S. Nirindrainy A. F. Heck N. Saldarriaga M. G. Xu Y. (2022). The impacts of long-term changes in weather on small-scale fishers’ available fishing hours in Nosy Barren, Madagascar. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.841048

22

Fröcklin S. de la Torre-Castro M. Håkansson E. Carlsson A. Magnusson M. Jiddawi N. S. (2014). Towards improved management of tropical invertebrate fisheries: including time series and gender. PloS One9, e91161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091161

23

Gough C. L. A. Dewar K. M. Godley B. J. Zafindranosy E. Broderick A. C. (2020). Evidence of overfishing in small-scale fisheries in Madagascar. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00317

24

Gough C. L. A. Harris A. Humber F. Roy R. (2009). “ Biodiversity and health of coral reefs at pilot sites south of Toliara: WWF Southern Toliara Marine Natural Resource Management Project MG0910.01.,” in Blue Ventures Conservation Report. (London: Blue Ventures).

25

Harding S. Randriamanantsoa B. Hardy T. Curd A. (2006). “ Coral Reef Monitoring and Biodiversity Assessment to support the planning of a proposed MPA at Andavadoaka,” in Blue Ventures Conservation Report. (London: Blue Ventures).

26

Harper S. Adshade M. Lam V. W. Y. Pauly D. Sumaila U. R. (2020). Valuing invisible catches: Estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production. PloS One15, e0228912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228912

27

Harper S. Zeller D. Hauzer M. Pauly D. Sumaila U. R. (2013). Women and fisheries: Contribution to food security and local economies. Mar. Policy39, 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.10.018

28

Kittinger J. N. Teneva L. T. Koike H. Stamoulis K. A. Kittinger D. S. Oleson K. L. L. et al . (2015). From reef to table: social and ecological factors affecting coral reef fisheries, artisanal seafood supply chains, and seafood security. PloS One10, e0123856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123856

29

Kleiber D. Harris L. M. Vincent A. C. J. (2014a). Gender and small‐scale fisheries: A case for counting women and beyond. Fish Fisheries16, 547–562. doi: 10.1111/faf.12075

30

Kleiber D. Harris L. M. Vincent A. C. J. (2014b). Improving fisheries estimates by including women’s catch in the Central Philippines. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci.71, 656–664. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2013-0177

31

Langley J. M. (2006). “ Vezo knowledge: traditional ecological knowledge in Andavadoaka, southwest Madagascar,” in Blue Ventures Conservation Report. (London: Blue Ventures).

32

Laroche J. Razanoelisoa J. Fauroux E. Rabenevanana M. W. (1997). The reef fisheries surrounding the south‐west coastal cities of Madagascar. Fisheries Manage. Ecol.4, 285–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2400.1997.00051.x

33

Le Manach F. Gough C. Harris A. Humber F. Harper S. Zeller D. (2012). Unreported fishing, hungry people and political turmoil: The recipe for a food security crisis in Madagascar. Mar. Policy36, 564. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.08.008

34

Le Manach F. Gough C. Humber F. Harper S. Zeller D. (2011). “ Reconstruction of total marine fisheries catches for Madagascar, (1950-2008),” in Fisheries Catch Reconstructions: Islands, Part II. Fisheries Centre Research Reports, Eds. HarperS.ZellerD. (Vancouver, BC: Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia) vol. 19, 21–37.

35

Lenth R. (2024). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.10.5. (Vienna: Comprehensive R Archive Network).

36

Liu J. Dietz T. Carpenter S. R. Folke C. Alberti M. Redman C. et al . (2007). Coupled human and natural systems. Ambio36, 639–649. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[639:CHANS]2.0.CO;2

37

Liu J. Dietz T. Carpenter S. R. Taylor W. W. Alberti M. Deadman P. et al . (2021). Coupled human and natural systems: The evolution and applications of an integrated framework: This article belongs to Ambio’s 50th Anniversary Collection. Theme: Anthropocene. Ambio50, 1778–1783. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01488-5

38

Long S. Thurlow G. Jones P. J. S. Turner A. Randrianantenaina S. M. Gammage T. et al . (2021). Critical analysis of the governance of the Sainte Luce Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA), southeast Madagascar. Mar. Policy127, 103691. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103691

39

Lüdecke D. Ben-Shachar M. S. Patil I. Waggoner P. Makowski D. (2021). performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Software6, 3139. doi: 10.21105/joss.03139

40

Maire E. D’agata S. Aliaume C. Mouillot D. Darling E. S. Ramahery V. et al . (2020). Disentangling the complex roles of markets on coral reefs in northwest Madagascar. Ecol. Soc.25. doi: 10.5751/ES-11595-250323

41

McCabe M. K. Mudge L. Randrianjafimanana T. Rasolofoarivony N. Vessaz F. Rakotonirainy R. et al . (2024). Impacts of locally managed periodic octopus fishery closures in Comoros and Madagascar: Short-term benefits amidst long-term decline. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1358111

42

McClanahan T. Ateweberhan M. Omukoto J. Pearson L. (2009). Recent seawater temperature histories, status, and predictions for Madagascar’s coral reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.380, 117–128. doi: 10.3354/meps07879

43

McClanahan T. R. Mangi S. C. (2004). Gear‐based management of a tropical artisanal fishery based on species selectivity and capture size. Fisheries Manage. Ecol.11, 51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2004.00358.x

44

McVean A. R. Hemery G. Walker R. C. J. (2005). “ Traditional sea cucumber fisheries in southwest Madagascar: A case-study of two villages in 2002,” in SPC Beche-de-Mer Information Bulletin 21. (Nouméa: Secretariat of the Pacific Community).

45

Obura D. Oliver T. (2009). “ Coral reef health and status,” in A Rapid Marine Biodiversity Assessment of the Coral Reefs of Northeast Madagascar. Eds. McKennaS. A.AllenG. R. (Arlington, VA: Conservation International). doi: 10.1896/054.061.0108

46

Ojea E. Lester S. E. Salgueiro-Otero D. (2020). Adaptation of fishing communities to climate-driven shifts in target species. One Earth2, 544–556. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.012

47

Pavlowich T. Kapuscinski A. R. (2017). Understanding spearfishing in a coral reef fishery: Fishers’ opportunities, constraints, and decision-making. PloS One12, e0181617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181617

48

Purcell S. W. Lovatelli A. González-Wangüemert M. Solís-Marín F. A. Samyn Y. Conand C. (2023). “ Commercially important sea cucumbers of the world—Second edition,” in FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 6, Rev. 1 ( FAO, Rome). doi: 10.4060/cc5230en

49

Quezada-Escalona F. J. Tommasi D. Kaplan I. C. Hernvann P.-Y. Frawley T. H. Garcia D. et al . (2025). Socio-economic impacts and responses of the fishing industry and fishery managers to changes in small pelagic fish distribution and abundance. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries35, 1063–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11160-025-09949-4

50

Raberinary D. Andrisoa A. (2024). Assessing stock of reef octopus Octopus cyanea in southwest Madagascar using age-based population modelling. Aquat. Living Resour.37, 13. doi: 10.1051/alr/2024011

51

Ranaivomanana H. S. Jaquemet S. Ponton D. Behivoke F. Randriatsar R. D. Mahafina J. et al . (2023). Intense pressure on small and juvenile coral reef fishes threatens fishery production in Madagascar. Fisheries Manage. Ecol.30, 494–506. doi: 10.1111/fme.12637

52

Randrianarivo M. Guilhaumon F. Tsilavonarivo J. Razakandrainy A. Philippe J. Botosoamananto R. L. et al . (2022). A contemporary baseline of Madagascar’s coral assemblages: Reefs with high coral diversity, abundance, and function associated with marine protected areas. PLoS One17, e0275017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275017

53

R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_ (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed November 4, 2025).

54

Rocliffe S. Harris A. (2016). “ The status of octopus fisheries in the Western Indian Ocean.” in Blue Ventures technical report. (London: Blue Ventures).

55

Rothamel E. Borgerson C. Rajaona D. Razafindrapaoly B. N. Rasolofoniaina B. J. R. Feehan C. (2023). Wild sea cucumber trade in rural Madagascar: Consequences for conservation and human welfare. Conserv. Sci. Pract.5, e13033. doi: 10.1111/csp2.13033

56

Vincent I. V. Hincksman C. M. Tibbetts I. R. Harris A. (2011). Biomass and abundance of herbivorous fishes on coral reefs off Andavadoaka, western Madagascar. Western Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci.10, 83–99.

57

Weiskopf S. R. Cushing J. A. Morelli T. L. Myers B. J. E. (2021). Climate change risks and adaptation options for Madagascar. Ecol. Soc.26. doi: 10.5751/ES-12816-260436

58

Westerman K. Benbow S. (2013). The role of women in community-based small-scale fisheries management: the case of the south west Madagascar octopus fishery. Western Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci.12, 119–132.

59

White E. R. Baker-Médard M. Vakhitova V. Farquhar S. Ramaharitra T. T. (2021). Distant water industrial fishing in developing countries: A case study of Madagascar. Ocean Coast. Manage.216, 105925. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105925

60

Wulfing S. Kadba A. Baker-Médard M. White E. R. (2024). Assessing the need for temporary fishing closures to support sustainability for a small-scale octopus fishery. Fisheries Res.276, 107045. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2024.107045

Summary

Keywords

catch-per-unit-effort, gender, gear efficiency, management, Madagascar, small-scale fisheries

Citation

Fortunato-Jackson O, Baker-Médard M and White ER (2026) Regional and gendered patterns in Madagascar’s small-scale fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1684707. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1684707

Received

12 August 2025

Revised

04 November 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

03 February 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Raleigh Robert Hood, University of Maryland, United States

Reviewed by

Taner Yildiz, Istanbul University, Türkiye

Samantha Farquhar, United States Coast Guard Academy, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Fortunato-Jackson, Baker-Médard and White.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivia Fortunato-Jackson, oliviajackson06@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.