Abstract

Marine ecosystems are increasingly affected by climate-driven disturbances such as sea-level rise, marine heatwaves, ocean acidification, and pollution. Monitoring sentinel species is essential for detecting long-term environmental changes and informing evidence-based management. The California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) serves as a sentinel because its population dynamics and health reflect both environmental anomalies and anthropogenic stressors. This systematic review synthesizes nearly a century of research on factors affecting California sea lion health. Following PRISMA guidelines, 244 studies published between 1929 and 2024 were included, representing 284,627 individuals and 298,607 documented health-related occurrences. Environmental anomalies (external factors) accounted for 88.21% of all disorders, followed by nutritional and metabolic disorders (3.70%), infectious and parasitic diseases (3.17%), trauma and entanglements (2.38%), and toxins or contaminants (1.89%). Sex and age were frequently unreported, with 50.80% of individuals lacking sex identification and 61.4% lacking age classification, reflecting the limitations of stranding-based data. Geographically, 89.88% of individuals were reported from the United States and 10.12% from Mexico. Despite these biases, the synthesis reveals consistent patterns indicating that climate anomalies, particularly marine warming events, are the predominant drivers of adverse health outcomes. This review provides a comprehensive baseline to date for understanding health threats to California sea lions and offers critical insights for future monitoring and conservation strategies.

1 Introduction

Marine ecosystems are currently facing disruptions driven by climate change, including sea-level rise, marine heatwaves, ocean acidification, and pollution (Ainsworth et al., 2019; UN, 2023). Assessing marine environmental quality is essential to detect long-term changes, evaluate conservation effectiveness, and support evidence-based management (Rombouts et al., 2013; Bal et al., 2018; Hazen et al., 2019; Marneweck et al., 2022).

One effective approach for such assessments is the monitoring of sentinel species, which are organisms sensitive to environmental degradation (Clark-Wolf et al., 2024). The responses of marine sentinel species, like marine mammals, to environmental changes can be measured through their demography, behavior, diet changes, and alterations in trophic networks (Godínez-Reyes et al., 2006; Koch et al., 2018; Hazen et al., 2019; Clark-Wolf et al., 2024).

The California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) is considered a sentinel species for coastal ecosystems (Godínez-Reyes et al., 2006; Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021). This species breeds from the California Channel Islands in the United States to the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico, including the Gulf of California (Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021). Their colonies, often near coastal human settlements, facilitate continuous monitoring but also increase exposure to anthropogenic threats, including entanglement in fishing nets, transmision of diseases from domestic animals and exposure to contaminants and industrial waste (Gulland, 1999; Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021).

In United States, the California sea lion population increased at an annual rate of 3% between 1964 and 2014 (Pozas-Franco, 2022; Laake et al., 2018; Valenzuela-Toro et al., 2023). By 2014, the estimated population was approximately 257,606 individuals, representing 80% of the global population (Laake et al., 2018; Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021; United States Department of the Navy, 2024). The remaining 20% of the population is found along the coasts of Mexico, with 14% located in the Baja California Peninsula and 6% in the Gulf of California (Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021; United States Department of the Navy, 2024).

During the 2010 reproductive season, populations were estimated at 52,846–54,482 individuals along the Baja California coast and 16,705–22,117 in the Gulf of California (Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021). Most of the colonies in Mexico have experienced population declines (Pelayo-González et al., 2021b). Since 1978, the sea lion population has decreased at an annual rate of 4% and 1% in the northern and central regions of the Gulf of California, respectively, while the southern population has increased at an annual rate of 3% (Pelayo-González et al., 2021b). These population declines have been linked to marine warming events that reduce prey availability and quality (Adame et al., 2020; Pelayo-González et al., 2021a). Despite the importance of health as a key component of population viability, research on this topic remains limited. Only a few studies have directly analyzed the health status of California sea lions focusing on indicators such as body condition, stress biomarkers, heavy metals exposure, and changes in foraging habits, among others (Melin et al., 2010; Banuet-Martínez et al., 2017; Gulland et al., 2020). Therefore, monitoring health parameters can provide valuable insights into ecosystem alterations associated with pollution, the emergence of infectious pathogens, and the effects of climate variability.

California sea lions in the United States have experienced sustained population growth since the 1970s; however, episodic declines in abundance have been documented in association with changes in the abundance and distribution of prey linked to warm-water events (Laake et al., 2018; McClatchie et al. 2016; Lowry et al. 2021). This trend is largely attributed to strong legal protections under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, a flexible diet that includes a wide range of prey species whose composition varies with availability, and the population’s capacity to recover after anomalous climatic events (Laake et al., 2018). In contrast, almost all reproductive colonies in the Gulf of California have declined, with some losing up to 65% of their numbers over recent decades. These declines have been associated with extreme climatic events, reduced prey availability, and a less diverse diet compared with colonies from other regions (Adame et al., 2020; Pelayo-González et al. 2021a, b). However, a notable exception is the small Los Islotes colony, the southernmost reproductive colony in the Gulf of California, which has shown a steady increase in abundance over the past decades due to highly productive area throughout the year due to a seasonal mesoscale gyre that likely provides more stable prey availability and strong conservation measures (Hernández-Camacho et al., 2021; Adame et al., 2020).

The traditional biomedical model defines health as the statistical normality of biological functions, considering disease as an abnormal state that reduces the organism’s functional capacities (Boorse, 1977; Tyreman, 2006; Boorse, 2011). This approach focuses on biological and physical factors, including genetic predispositions, pathogenic agents, carcinogenic agents, and other elements interacting with internal biological states (Boorse, 1977; Tyreman, 2006; Havelka et al., 2009; Boorse, 2011). On the other hand, the biopsychosocial model proposed by Engel (1977) broadens the definition by including psychological, social, and environmental factors that are external to the individual. While these factors do not directly cause disease, they influence its development, aggravation, or conditioning.

Whereas biomedical health relies on individual-based indicators, ecosystem condition is assessed using diverse diagnostic approaches that recognize balanced functioning as the result of complex interactions across multiple dimensions (Costanza and Mageau, 1999; Tabor and Aguirre, 2004; Costanza, 2012).

Sentinel species represent a key diagnostic tool for evaluating ecosystem attributes such as organization, vigor, and resilience, parameters that reflect overall ecological health (Boesch, 2000; Bonde et al., 2004; Costanza, 2012).

Changes in these parameters can reveal ecosystem disturbances and, when analyzed at the population level, facilitate the interpretation of broader ecosystem status (Costanza, 2012; Mallick et al., 2021; Clark-Wolf et al., 2024). Some evidence linking ocean health to the deteriorating condition of California sea lions is reflected in reduced body condition and population declines (Elorriaga-Verplancken et al., 2016; McClatchie et al., 2016; Banuet-Martínez et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2018; Adame et al., 2020; Pelayo-González et al., 2021b; Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2024). These decreases, particularly in populations from the Channel Islands in the United States, as well as from the Gulf of California and the San Benito Archipelago on the Pacific coast of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico, have been documented over the past three to four decades and are primarily driven by dietary shifts resulting from reduced prey availability. The most severe impacts have been observed in pups and breeding females (Elorriaga-Verplancken et al., 2016; McClatchie et al., 2016; Banuet-Martínez et al., 2017; Laake et al., 2018; Adame et al., 2020; Pelayo-González et al., 2021b; Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2024).

The shortage of prey has been associated with anomalous ocean-warming events that disrupt marine ecosystems and directly affect the trophic chains on which these animals depend (McClatchie et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2018; Adame et al., 2020).

In relation to rising sea surface temperature (SST), low birth rates in the Gulf of California have been linked to a +1°C increase in SST in northern and central regions (Pelayo-González et al. 2021b). Along the Pacific Coast, similar patterns have been documented: population growth stabilizes at approximately +1°C and begins to decline beyond this threshold. The decline becomes more pronounced when SST anomalies reach +2°C (Melin et al., 2012; Laake et al., 2018). Additionally, increased strandings have historically been considered a predictor of the rising presence of polluting agents such as domoic acid, a neurotoxin produced by harmful algal blooms (Smith et al., 2023). Recently, the prevalence of urogenital cancer has been associated to the presence of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and otarine herpesvirus (OtHV-1) detected in tissues of California sea lions (Adame et al., 2020; Gulland et al., 2020; McClain et al., 2023).

Although previous research has examined demography, trophic ecology, and isolated health studies, no comprehensive synthesis has yet integrated historical data on a full range of factors and agents affecting the health of the California sea lion. This information is critical for future management and conservation planning of the species. In this context, our objective was to conduct an exhaustive literature review integrating studies on biological and chemical agents (pathogens and contaminants), nutritional factors, physical impacts (e.g. entanglements and trauma), and external stressors (climate anomalies and human disturbances). Through this approach, we aim to identify the principal factors affecting California sea lion health and assess their ecological and conservation implications.

2 Methods

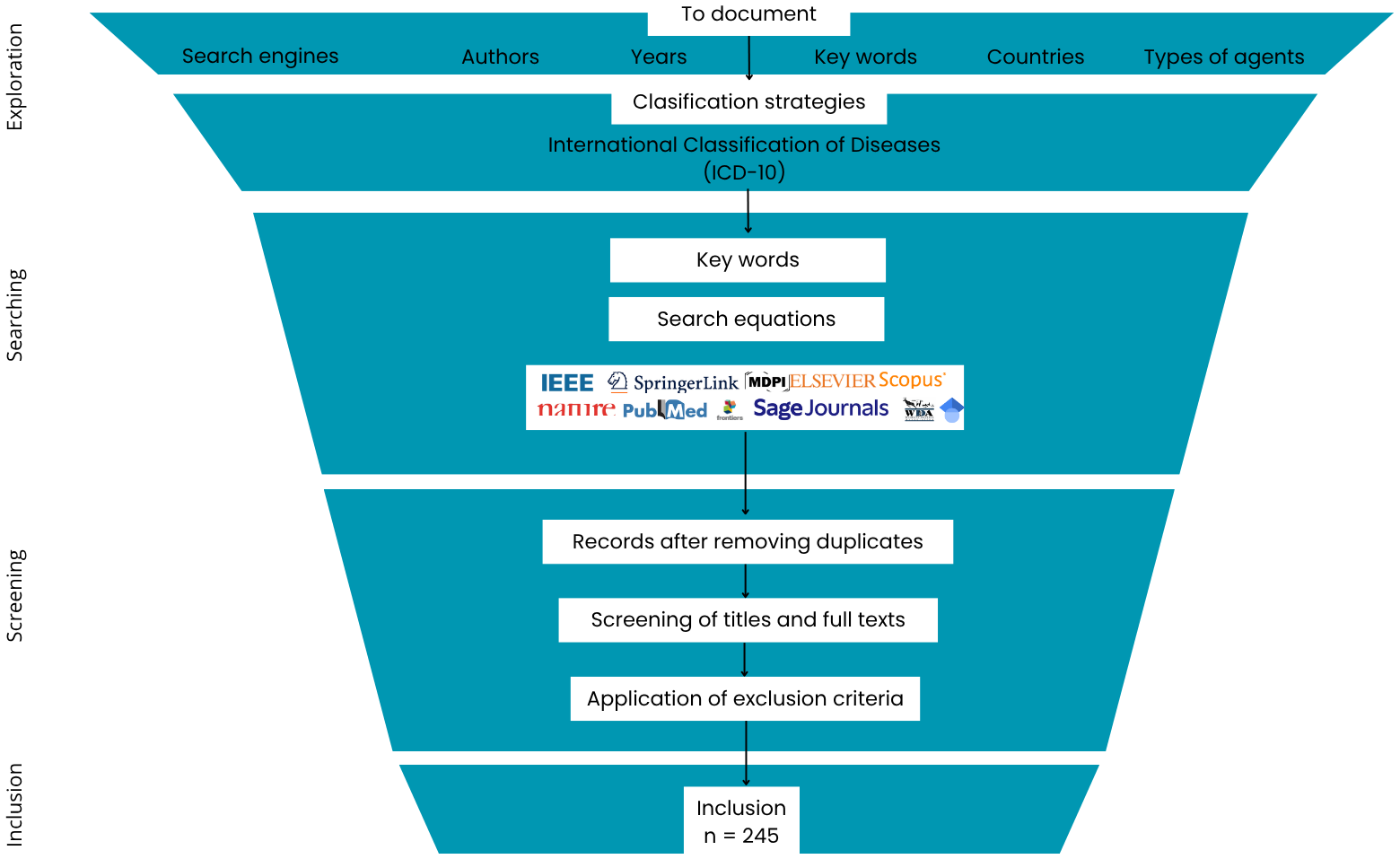

The PRISMA method was selected. The methodology consists of three phases: Identification (Exploration and Search in this review), Screening, and Inclusion (Manrique-Escobar et al., 2022) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Search and recovery process of literature (PRISMA method adaptation) about agents and factors affecting California sea lion health.

In the Exploration phase, the nature of the available evidence on the factors and agents affecting the California sea lion’s health was generally explored. Frequent search engines, authors, keywords, and types of factors or agents were documented. Subsequently, in the Search phase, academic search engines such as Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed, IEEE Explorer, JSTOR, Dialnet, and ScienceDirect, among others, were used with multiple combinations of keywords (Table 1).

Table 1

| Object | Predictive variables | Expected response variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zalophus californianus | Viral | Plastics | Illness | Trauma |

| Zalophus | Bacteria | Toxins | Infectious disease | Death |

| Sea lion | Fungi | Fishing gear | Diseases | Injuries |

| Marine mammals | Helminths | Contaminants | Effects | Abortion |

| Pinnipeds | Protozoa | Entanglement | Behavioral | Intoxication |

| Otarine | Pollutants | PCB, DDT, POPs | changesMalnutrition | Defects |

Word combinations used for online literature searches related to agents and factors affecting the health of the California sea lion.

Search expressions were constructed by generating all possible combinations among three sets of terms: one corresponding to the target/object, another to the predictive variables, and a third to the expected response variables. Each term from the target set was systematically combined with all predictive variables and with each expected response variable. The Boolean operator AND was inserted between the terms in every resulting combination, yielding search expressions structured as: Object and Predictive variable and Expected response variable.

In the Screening phase, publications were selected when their title contained at least one word from each of the following categories: target (species), predicting variables, and expected response variables (type of effect/observed behavior). Publications were excluded if they were incomplete or failed to identify a specific factor or agent. For the selected publications, data were documented on the type of factor or agent, number of affected individuals, sex, age class, year of disease occurrence, country, region, and publication reference. When age class was reported in years, it was categorized according to Greig et al. (2005): pups (0–2 years), juvenile males (2–4 years), subadult males (4–8 years), juvenile or subadults (2–5 years), adult males (≥8 years). Pups that were only a few days old were referred to as neonates. If the total sample size was not explicitly stated, it was estimated from available details (indices or percentages) and noted in the summary table. Individuals reported as unknown sex or age retained that classification. All reported factors and agents were classified through an adaptation of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) for the sea lion (Figure 2; Table 2; Supplementary Table S1).

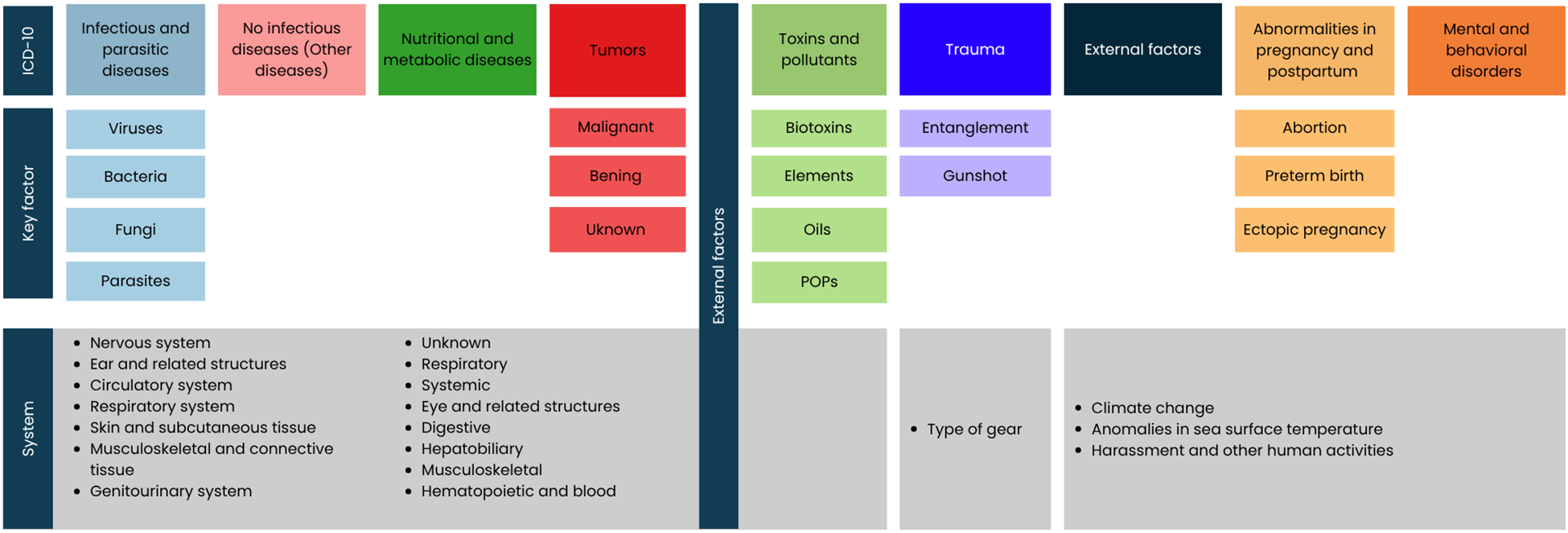

Figure 2

Classification of diseases, agents, and factors that impact the California sea lion's health. The following ICD-10 categories were used: Infectious and parasitic diseases, Non-infectious diseases (in this work referred to as “Other diseases”), Nutritional and metabolic diseases (NMD), Tumors, Toxins (in this work referred to as “Toxins and contaminants”), Trauma, Pregnancy, parturition, and puerperium abnormalities and External factors.

Table 2

| Classification according to the ICD-10 | Classification in this review | System affected |

|---|---|---|

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | Infectious diseases | Nervous system Eye and related structures Ear and related structures Circulatory system Respiratory system Digestive system Musculoskeletal and connective tissue Genitourinary system Skin and subcutaneous tissue Hematopoietic and blood Systemic |

| Parasitic diseases | ||

| Neoplasms or tumors | Tumors | |

| Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | Toxins and pollutants | |

| Trauma | Type of gear | |

| Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | Nutritional and metabolic diseases | |

| Mental and behavioural disorders | Behavioural disorders | |

| Various* | External factors | Climate change Anomalies in sea surface temperature Harassment and other human activities |

Adapted ICD-10–based classification of factors and health conditions affecting California sea lions.

*Within the ICD-10, categories such as Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes, External causes of morbidity and mortality, and Factors influencing health status and contact with health services are included. Although these categories encompass events such as injuries, accidents, assaults, and the effects of foreign objects in the body, none explicitly address the impacts of climate change. Therefore, introducing the External factors category was necessary.

Infectious and parasitic diseases were classified according to the ICD-10, which incorporates the International Nomenclature of Infectious Diseases (IND) and classifies them by origin (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic) (ICD-10). When the infectious disease was not identified, it was classified as Unknown. For each individual, the system, disease, and infectious or parasitic agent were recorded; for diseases, the disease name was recorded; for agents, the species was recorded when mentioned. Data on agents and diseases with fewer than 45 individuals were grouped under “Other”.

Trauma or entanglement was classified according to the specification in the information source. Gunshots, dart wounds, boat collisions, and shark bites were categorized as Trauma. Documented entanglement gear was categorized adapting the Allyn and Scordino (2020) classification, resulting in the following categories: fishing gear (monofilaments, hooks, and lines, flash fishing gear), nets, marine debris, packing materials (strapping bands, rubber packing bands), diving equipment, and entanglement scars. Unspecified entanglement gear was classified as unknown.

Biotoxins, elements, POPs, plastics, and oil were documented even when no apparent signs of intoxication were present. The results presented here were interpreted as a register of occurrence in the species rather than a sign of intoxication, except for domoic acid. Malnutrition and emaciation were grouped under the malnutrition category, following the ICD-10 classification, and were thus kept together. Other nutritional or metabolic disorders and diseases were assigned to their respective categories according to the same classification. Tumors were classified as malignant, benign, or unknown type. Then, they were further classified by the body system in which the tumor was found. When mentioned, the name of the tumor was documented. Pregnancy, parturition, and puerperium disorders were classified as premature birth, abortion, and ectopic pregnancy. For all categories, the mother and lost pup were considered as one individual. Diseases that did not fall into any of the previous classifications were classified as Other Diseases and organized according to the body system in which they were found.

Research on the implications of external factors on health included diverse data types (case studies, population studies, cohort studies, etc.). To document the maximum amount of information on external factors affecting California sea lions’ health, a descriptive section was included to report these findings, and they were organized into the subcategories of external factors: “Climate anomalies” and “Human disturbances”.

Individuals quantified for a given external factor were further classified according to whether the factor referred to a climatic anomaly in sea surface temperature (e.g., during climatic phenomena such as El Niño) (CA), unusual mortality events (UME), or sustained warming (SC), among others. To estimate the number of affected individuals, the population decline during marine warmings such as El Niño and marine heatwaves (linked to mass mortality events UMEs) was analyzed. Population data to obtain the estimates were taken from Laake et al. (2018). The quantifiable anthropogenic external factors are found in the appendix (Supplementary Table S1) of this review under the legend “Other external factors”, which include harassment, lethal removal permits by the government, and scientific research. Finally, individuals under human care were analyzed separately, and their factors and agents were documented under the same classification. The category “Unrelated to external factors” was created for cases in which no cause for the anomaly in behavior was reported. Most of these are sightings obtained from databases that only reported the incident, and we were unable to find any subsequent study analyzing the cause, so these remain unknown if they are related or not to external factors.

3 Results

A total of 244 studies documenting factors or agents affecting California sea lion health were included from 1929 to 2024. This study collection includes open-access databases from NOAA as well as peer-reviewed articles.

The total number of registered individuals in this review was 284,593, documenting 298,573 occurrences of factors or agents affecting California sea lion health. Of these individuals, 23.18% were females, 26.01% were males, and 50.80% were unidentified by sex. Age classification was also documented, with 30.87% classified as pups, 5.77% as juveniles, 0.68% as subadults, 1% as adults, 61.4% as indeterminate, and 836 (0.28%) as neonates.

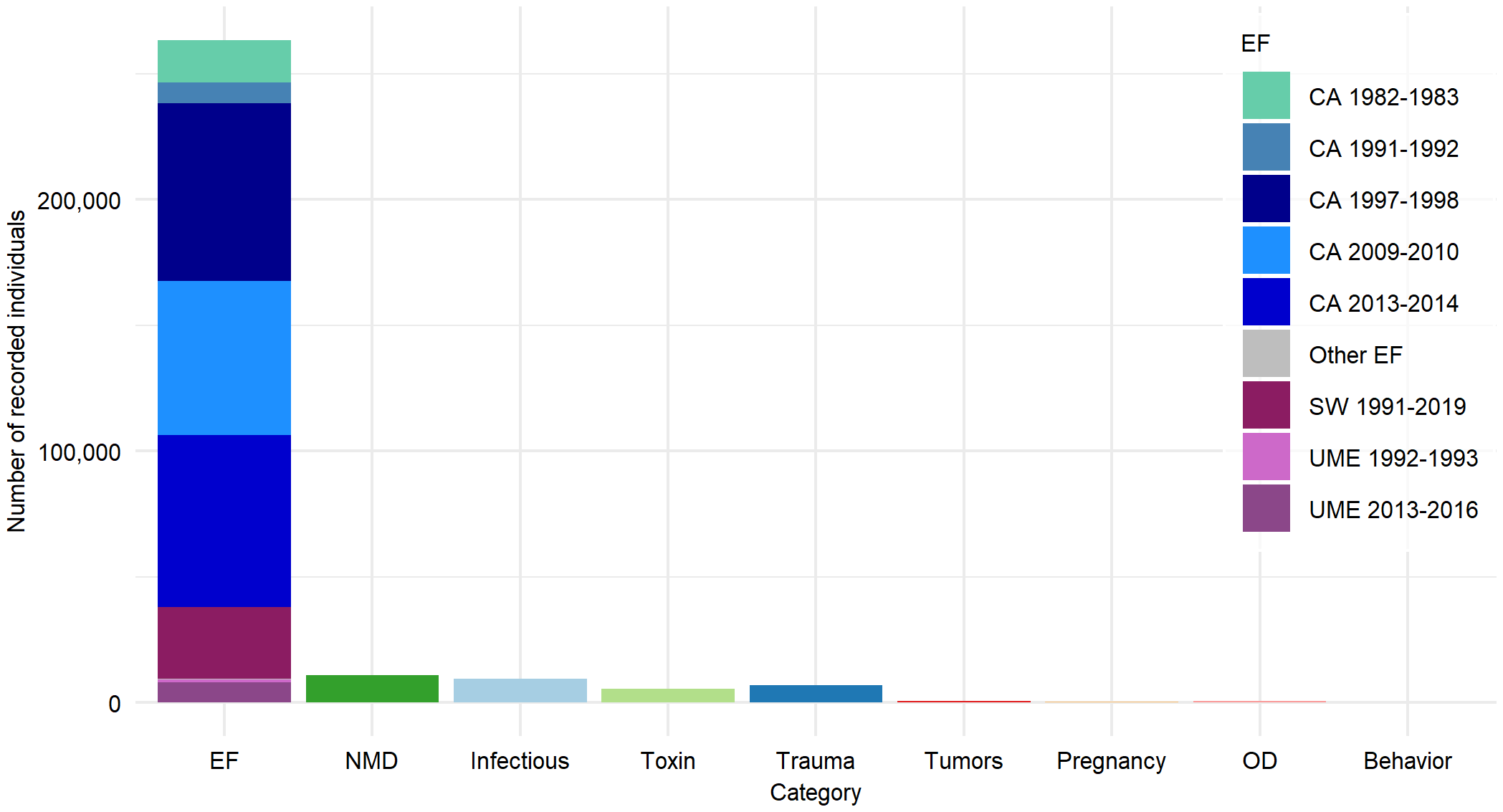

Of the 298,573 disorders, 88.21% corresponded to external factors, 3.70% nutritional and metabolic disorders (NMD), 3.17% infectious and parasitic agents, 2.37% trauma and entanglements, 1.89% toxins and other contaminants, 0.25% other diseases (OD), 0.22% tumors, 0.17% pregnancy, and 0.004% behavioral anomalies (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Number of individuals by category: External Factors (EF) (climate anomalies (CA), sustained warming (SW), unusual mortality events (UME), and other EF (see Supplementary Table S1); Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases (NMD); Infectious and parasitic diseases (Infectious); Toxins and contaminants (Toxin); Tumors; Pregnancy, parturition and puerperium disorders (Pregnancy); Other Diseases (OD); and behavioral anomalies unrelated to EF (Behavior).

Regarding the total number of registered individuals, 89.88% belong to the United States and 10.12% to Mexico. In the United States, 268,378 factors and agents were recorded, distributed as follows: 87.51% external factors, 4.11% NMD, 3.41% infectious or parasitic diseases, 2.40% trauma, 1.85% toxins and contaminants, 0.28% OD, 0.25% tumors, 0.18% pregnancy-related conditions, and 0.003% behavioral anomalies. For Mexico, 30,195 factors and agents were documented, with 94.56% corresponding to external factors, 2.27% to toxins and contaminants, 2.08% to trauma, 1.06% to infectious or parasitic diseases, 0.01%to OD, 0.01to NMD, 0.007% to tumors, and 0.007% to behavioral anomalies.

3.1 Nutritional and metabolic diseases

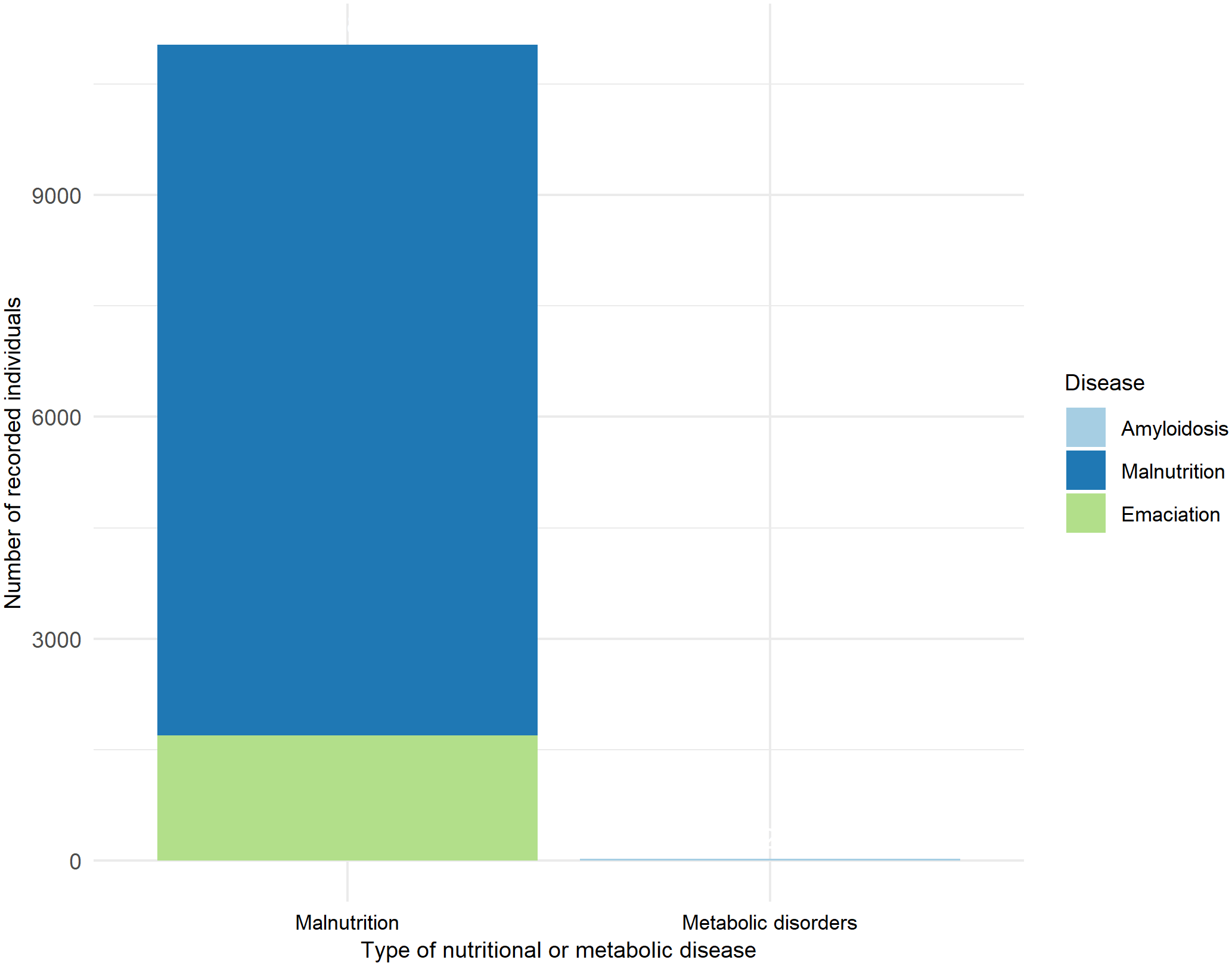

A total of 11,057 individuals with nutritional or metabolic disorders were identified. Of these, 5.28% were females, 5.75% were males, and 88.97% were unidentified by sex. Regarding age class distribution, 20.90% were pups, 73.48% were juveniles, 1.60% were subadults, 0.59% were adults, and 1.43% were unclassified. Among the recorded individuals, 0.24% presented amyloidosis, categorized as a metabolic disorder. The remaining 11,030 individuals were classified under malnutrition (99.76%), subdivided into malnutrition (84.63%) and emaciation (15.37%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Recorded individuals with nutritional or metabolic disease.

3.2 Infectious and parasitic diseases

A total of 9,464 individuals showed diseases or infectious agents, 16.48% males, 6.57% females, and 76.94% unspecified. Regarding their age class, 65.15% were unspecified, 10.21% were subadults, 14.29% were pups, 5.2% were juveniles, 4.17% were adults, and 0.98% were neonates.

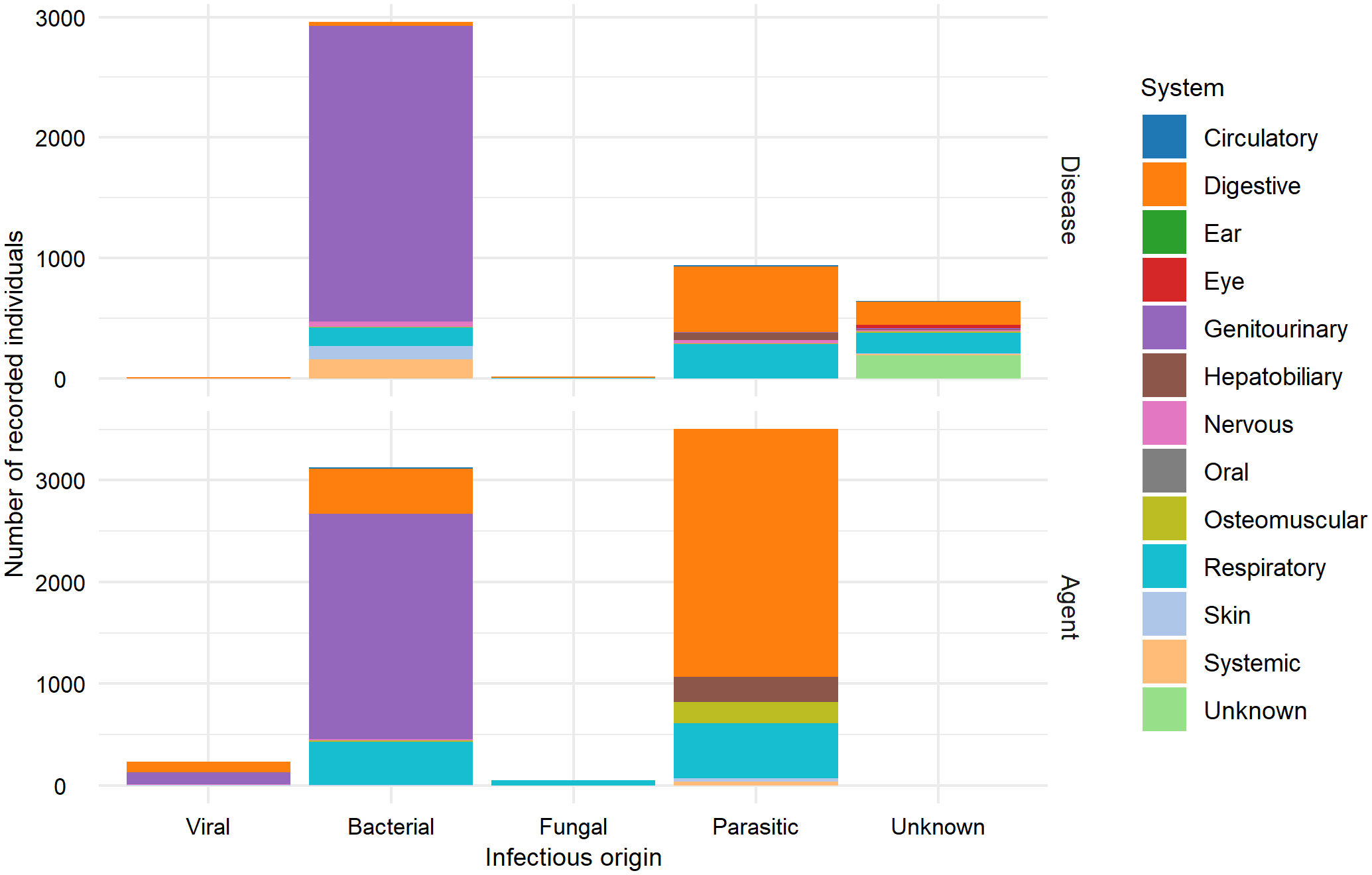

Of the bacterial diseases and agents, 76.65% (4,664 individuals) were linked to the genitourinary system, followed by 9.53% in the respiratory system and 7.81% in the digestive system. For the parasitic diseases and agents, 67.22% (2,984 individuals) were associated with the digestive system, 18.72% with the respiratory system, and 6.89% with the hepatobiliary system. Viral diseases and agents were distributed as 50.62% (123 individuals) in the genitourinary system, 45.68% in the digestive system, and 1.65% in the respiratory system. Finally, 82.81% (53 individuals) of fungal diseases and agents affected the respiratory system, while 17.19% were linked to the digestive system (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Number of recorded individuals with infectious diseases and the origin of the infectious agent (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and unknown) by affected body system. Top: Number of individuals recorded with a disease categorized by pathogenic agent origin (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and unknown) and affected body system. Bottom: Number of identified pathogens (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic) and affected body system.

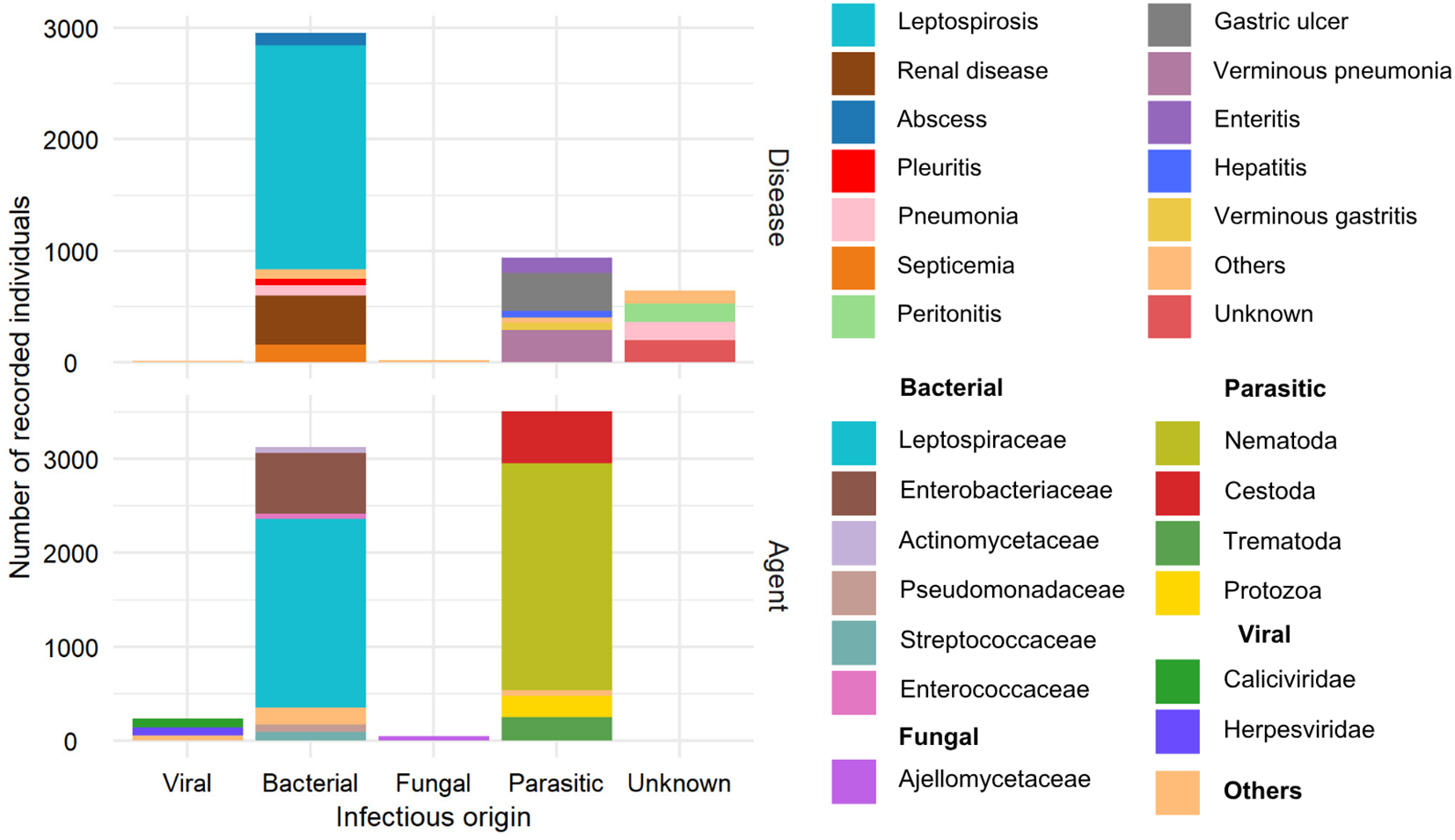

In total, 4,563 diseases cases and 6,912 infectious and parasitic agents were documented. Based on the infectious origin, 53.03% were bacterial diseases and agents, 38.68% were parasitic, 2.12% were viral, 0.56% were fungal, and 5.61% had an undocumented origin (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Number of recorded individuals with infectious diseases and origin of the infectious agent (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and unknown). Top: Number of infected individuals by pathogenic origin and diagnosis. Bottom: Number of pathogens (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic) by taxonomic classification of the pathogen.

Of the 6,912 documented agents, 45.24% were bacterial, 50.66% were parasitic, 3.39% were viral, and 0.69% were fungal. For viral agents, Caliciviridae (93 individuals) and Herpesviridae (84 individuals) were the most prevalent. For bacterial agents, Leptospiraceae (2,011 individuals) were most prevalent, followed by Enterobacteriaceae (645 individuals). The Ajellomycetaceae family was most frequently recorded among fungal agents (45 individuals). Nematodes of the Anisakidae family were the most documented (1,116 individuals).

A total of 4,563 diseases were recorded, with 64.82% of bacterial origin, 20.53% parasitic, 14.11% of unknown origin, 0.35% fungal, and 0.17% viral. The most frequently documented bacterial disease was leptospirosis, with 2,011 individuals, followed by renal disease (436) and septicemia (158). Gastric ulcer disease, verminous pneumonia, and parasitic enteritis were the most prevalent parasitic diseases, affecting 339, 287, and 140 individuals, respectively. Regarding viral infectious diseases, five cases of vesicular disease were documented, caused by viruses from Caliciviridae family, specifically San Miguel sea lion virus types 6 and 13 (Smith et al., 1979; Berry et al., 1990). Two cases of viral hepatitis were also recorded: one was caused by a mastadenovirus (OtAdv-1) from the Adenoviridae family (Goldstein et al., 2011), and the other was identified as an adenovirus based on morphological classification (Dierauf et al., 1981). Peritonitis of fungal origin was recorded in 11 individuals and pleuritis in 5. Among diseases of unknown origin, 192 were non-described, 168 were peritonitis cases, and 166 were pneumonias (Figures 5, 6).

3.3 Trauma

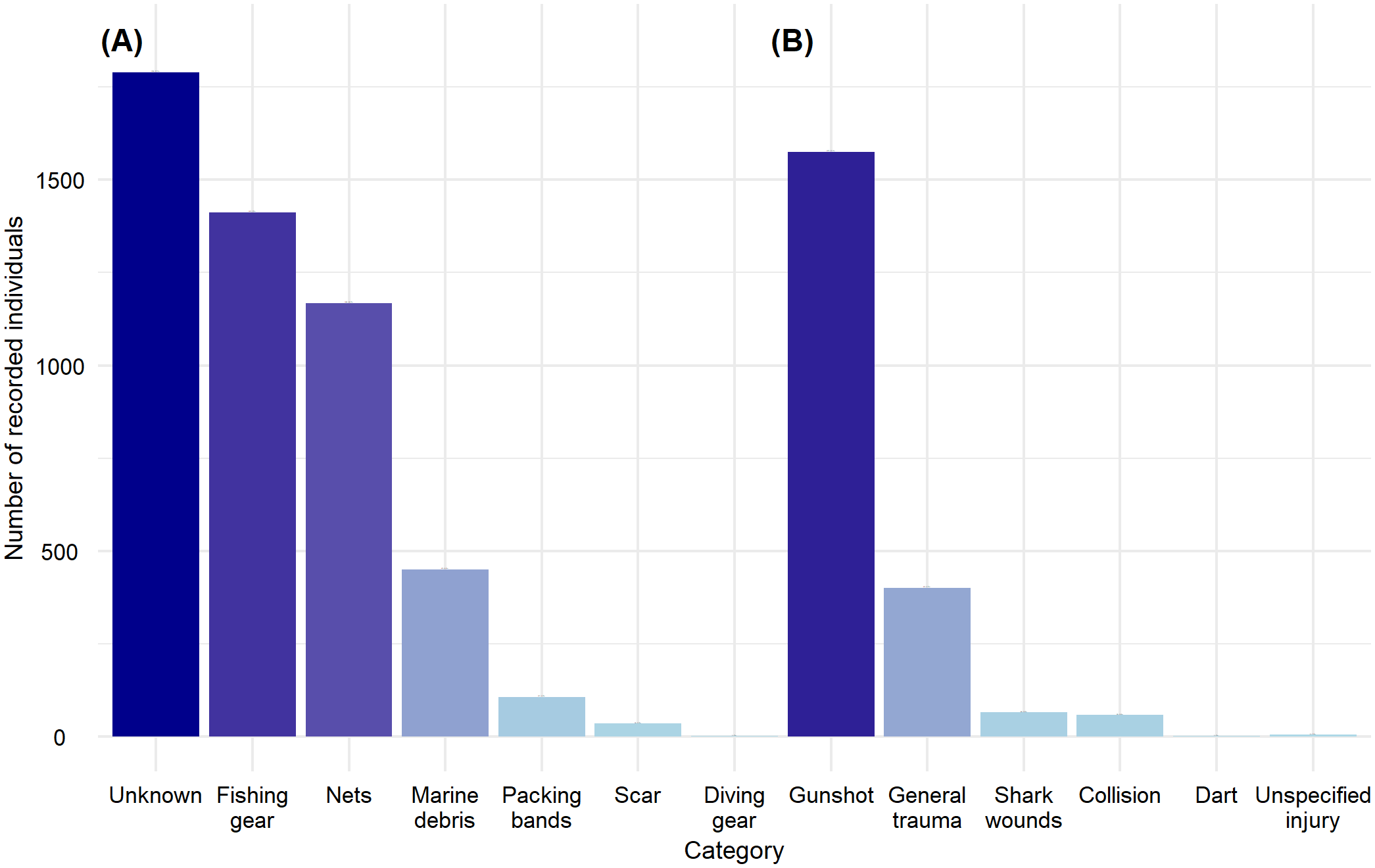

A total of 7,074 individuals with trauma or entanglement were recorded. Of these, 85.60% had unknown sex, 8.51% were males, and 5.89% were females. Regarding their age class, 82.20% were unclassified, 6.96% were adults, 4.11% were pups, 3.87% were juveniles, and 2.86% were subadults.

Of the total individuals, 70.19% showed evidence of entanglement, while the remaining 29.81% exhibited trauma. The most frequent causes of entanglement were undocumented in 36.03% of cases, followed by fishing gear like lines and hooks at 28.44%, and nets at 24.52%. Other trauma reported 74.68% gunshot wounds, 19.01% generalized trauma, and 3.13% shark bites (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Recorded individuals for the Trauma category. (A) Individuals with documented or apparent entanglement marks; (B) Individuals with documented or apparent wounds or trauma marks.

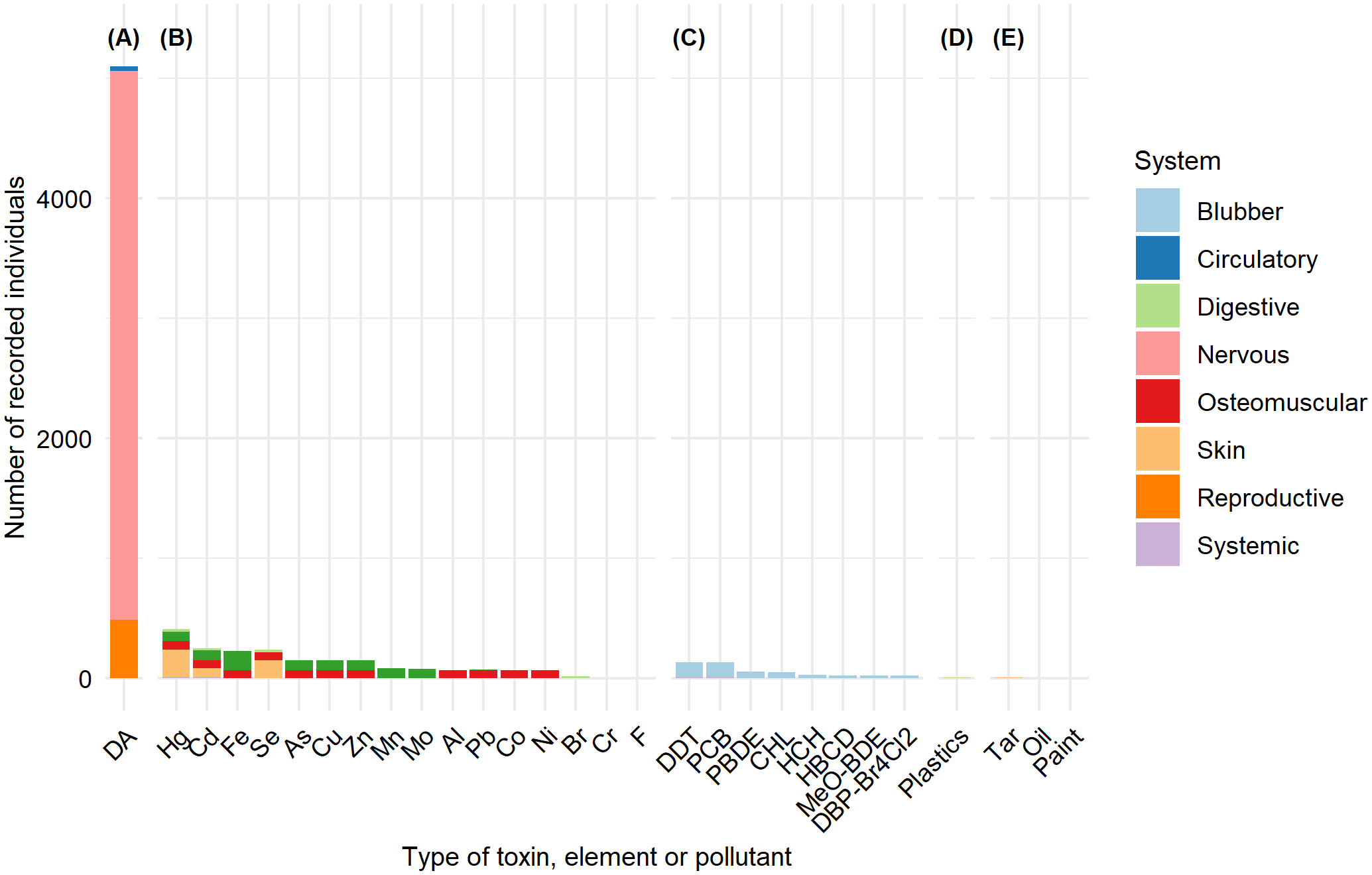

3.4 Toxins and other contaminants

A total of 5,643 individuals were recorded with presence of toxins, elements, or other types of contaminants. Of these, 47.69% were females, 21.85% were males, and 30.46% were of undetermined sex. From the total records, 3.37% were juveniles, 4.52% were pups, 4.89% were neonates, 11.09% were subadults, 25.93% were adults, and 50.2% were of undetermined age. Domoic acid was the only biotoxin recorded, with a total of 5,096 individuals representing 66.75% of cases. This biotoxin was primarily detected in the nervous system, representing 89.68% of cases, followed by the reproductive system in 9.54% of cases.

The presence of persistent organic contaminants was recorded in fat samples from 461 individuals and 20 samples from various origins. The most frequently documented persistent contaminants in research studies were DDT and PCB. A total of 2,036 individuals were recorded with elements of potential anthropogenic origin, with samples obtained from the osteomuscular system in 34.91% of cases and from the digestive/renal system in 35.41% of cases.

Ingestion of macroplastics was documented in 9 individuals. In one case, it was not possible to determine the number of affected individuals because the analysis was performed on fecal matter; this case was not included. A total of 13 cases of California sea lions were recorded with oils or other substances adhered to their fur, including tar, paint, or unidentified substances (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Recorded individuals and the body system or tissue affected by the toxin or contaminant. (A) Biotoxins (domoic acid); (B) heavy metals and other elements; (C) Organic contaminants including: Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE), chlordane, hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), methoxylated diphenyl brominated ether (MeO-DBE), and dibromophenyl ether with four bromine atoms and two chlorine atoms (DBP-Br4Cl2); (D) Plastics; (E) Other contaminants.

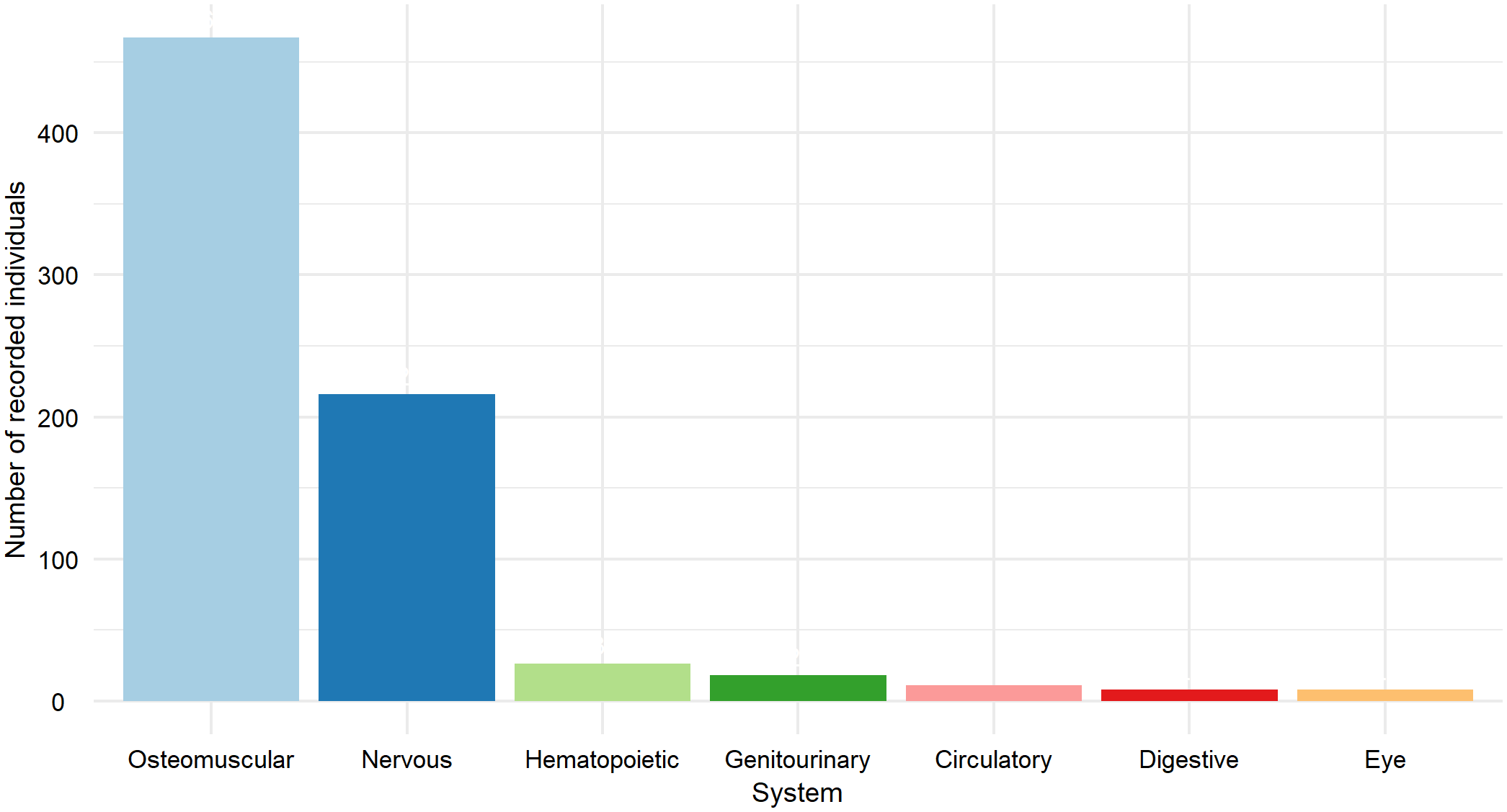

3.5 Other diseases

A total of 754 individuals were recorded in the “Other Diseases” category. Of these, 1.86% were females, 1.46% were males, and 96.68% were unidentified. Regarding age distribution, 4.77% were pups, 0.53% were juveniles, 0.66% were subadults, 2.39% were adults, and 91.64% were not categorized into any specific age group. The diseases were categorized according to the affected body system (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Recorded individuals for the other diseases (OD) category, grouped by affected body system.

There were 11 records of circulatory system diseases, of which 8 (72.73%) were cardiomyopathies, while ventricular septal defect, heart failure, and myocardiopathy each had 1 record (9.09%). For the digestive system, 8 individuals were recorded, of which 6 (75%) had volvulus.

Among the 18 individuals recorded with genitourinary system disorders, 10 (55.56%) had renal failure, and 3 (16.67%) had hydronephrosis. The hematopoietic system recorded 26 individuals, all of which were California sea lions with anemia. The nervous system accounted for 216 records, with 166 cases (76.85%) of epilepsy likely due to domoic acid intoxication and 49 cases (22.69%) of seizures. For ocular disorders, 8 individuals were recorded: 4 with blindness and 4 with eye injuries. Finally, the system with the highest number of records was the osteomuscular system, including 467 individuals, which represents 61.94% of all “other diseases” cases. These included 147 individuals with rhabdomyolysis and 319 individuals with temporomandibular osteoarthritis, the latter being the most frequently recorded, representing 42.31% of all cases.

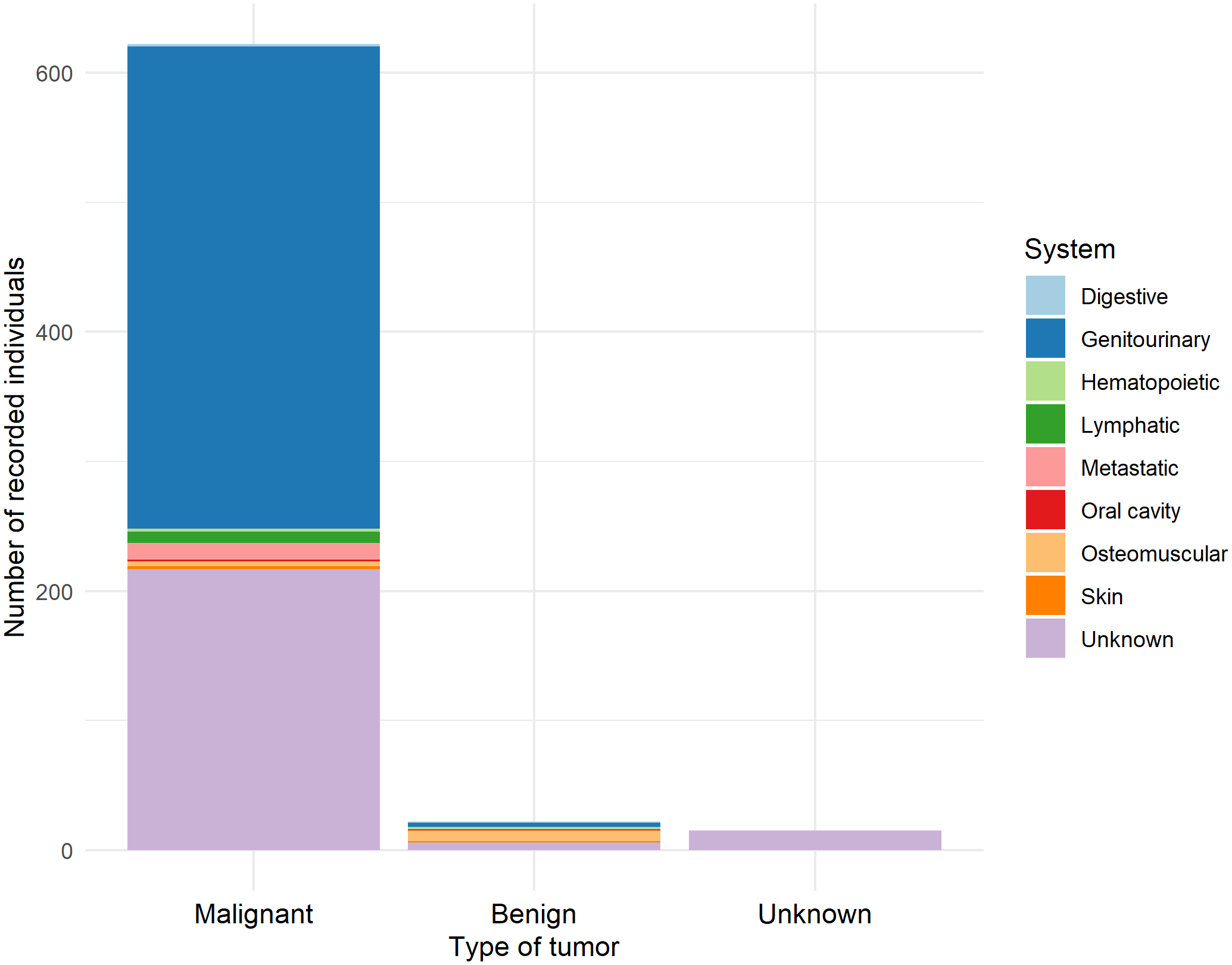

3.6 Tumors

A total of 659 tumor records were documented. Of these, 54.32% were females, 25.19% were males, and 20.49% were of undetermined sex. Regarding age classes, 77.39% were adults, 15.93% were undetermined, 4.55% were subadults, 1.67% were juveniles, and 0.46% were pups. Among the records, 94% of cases (622) reported malignant tumors, 3.34% were benign tumors, and 2.28% were of unknown type.

Malignant tumors in the genitourinary system represented 59.81% of all malignant tumor cases, followed by non-specified malignant tumors (cancer) at 34.89%, and metastatic tumors at 2.9%. Among the malignant tumors of the genitourinary system, 335 were located in the urogenital area, while only 36 were found in the renal area (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Recorded individuals categorized by the body systems in which the tumor was found.

Benign tumors were predominantly recorded in the smooth muscle system, representing 36.36% of cases, followed by tumors in unspecified systems (27.27%) and the genitourinary system (13.64%). Within the benign smooth muscle tumors, all were classified as leiomyomas; those of unknown origin corresponded to unspecified adenomas, while those in the genitourinary system were localized in the urogenital area. All unknown tumors were noted as neoplasms.

3.7 Pregnancy, parturition, and puerperium abnormalities

For this category, a total of 510 pregnant females were recorded, along with 510 lost neonates. The anomalies were classified into three categories: premature birth was the most frequent cause with 334 cases (65.49%), followed by unspecified abortions with 175 cases (34.32%). Of these, abortion represented 65.71% of cases, intrauterine death 29.71%, and post-mortem evidence of pregnancy 4.57%. It is important to highlight that all pregnancy cases were related to domoic acid exposure. One isolated case of ectopic pregnancy was recorded (0.2%).

3.8 Behavioral abnormalities unrelated to external factors

A total of 11 California sea lions were recorded, 3 were females, 2 were males, and 6 were of unrecorded sex. Of these, 3 were pups, 2 were adults, and 6 had no age recorded. The anomalies were classified into two groups: aggression, with 6 cases of human bites and 1 case of generalized aggression recorded; and abnormal behavior, with 2 individuals found outside their distribution range and 2 exhibiting other abnormal behaviors.

4 Discussion

According to this review of factors and agents affecting California sea lion health, external factors, especially environmental anomalies, had the greatest impact on the species’ health (Masper, 2019; Adame et al., 2020). Supporting evidence includes the mass mortality events recorded along the Pacific Coast between 2013 and 2015, as well as a 65% population decline in the Gulf of California (Elorriaga-Verplancken et al., 2015; Adame et al., 2020; NOAA Fisheries, 2022).

A relationship exists between sea surface temperature (SST) and the survival of sea lion populations (Laake et al., 2018). In the Pacific, when SST anomalies increase by +1°C, population growth begins to stall, and at +2°C, the decline becomes evident and more pronounced. However, negative effects such as reduced pup survival and halted population growth are already noticeable at +1°C. Meanwhile, in the Gulf of California, some models suggest that population declines occur when SST anomalies exceed 0.5°C in the northern region and 1°C in the central region (Laake et al., 2018; Pelayo-González, 2018; Adame et al., 2020). However, the long-term implications of sustained warming increases remain unclear (Melin et al., 2012; Laake et al., 2018; Adame et al., 2020).

Although the California sea lion population of the California Channel Islands in the United States, continues to grow, evidence suggests that this species employs diverse survival strategies when confronted with challenges such as prey depletion and marine heatwave events (Robinson et al., 2018). The consequences of the prey scarcity during El Niño events are typically quantified 2–3 years after the climatic anomaly (Trillmich and Limberger, 1985; Aurioles and Le Boeuf, 1991). However, abrupt SST changes have been linked to mass mortality events in different marine mammals (Crisci et al., 2011; Cavole et al., 2016; Sanderson and Alexander, 2020). This could explain the lack of data in other categories (infectious diseases, other diseases, toxicity, tumors, trauma, and pregnancy) since not all carcasses are documented, and this bias cannot be corrected (Carretta et al., 2017; Laake et al., 2018). Despite this, malnutrition has been directly associated with climatic events due to their impact on primary production, which leads to changes in prey availability, affecting sea lion feeding and body condition (Melin et al., 2010; Banuet-Martínez et al., 2017; DeRango et al., 2019). Malnutrition can be estimated and assessed using stranded individuals (Shuert et al., 2015), whereas other categories like diseases, intoxication, tumors, or trauma require a detailed examination. Detection rates for these categories depend on human effort, research objectives, and accessibility to stranded animals. These factors vary significantly and could be influenced by the reported counts compiled in this review (Van Heckereen and Skoch, 1987; Gulland, 1999; Greig et al., 2005; Masper, 2019).

Far from the decline numbers caused by climatic anomalies and their association with malnutrition (Melin et al., 2010; Banuet-Martínez et al., 2017; DeRango et al., 2019), the next most prevalent health issue was infectious diseases. The data presented in this review do not represent the overall population, as they primarily come from stranded animals, which represent minimum counts since not all carcasses are documented. This is because detection rates depend on human effort, special permits, and accessibility to animals, which can greatly vary. Additionally, these cases are not ideal representatives because they are not a random sample of the free-living population, as they are more likely to be unhealthy (Van Heckereen and Skoch, 1987; Gulland, 1999; Greig et al., 2005; Carretta et al., 2017; Laake et al., 2018; Masper, 2019).

Leptospirosis was the most frequently documented infectious disease and the second most common etiology associated with sea lion strandings (Neely et al., 2018). Leptospirosis is primarily contracted through contaminated waters such as runoff; another transmission mechanism involves contact with domestic animals in parks with elevated populations of carrier dogs, although zoonotic reservoirs such as bats or rats have also been suggested as transmission sources (Gulland et al., 1996; Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2003; Cameron et al., 2008; Norman et al., 2008). Young male migrations play a crucial role in the geographic spread of disease, as outbreaks often coincide with their movements, suggesting that agent transmission is facilitated by their movement patterns (Zuerner et al., 2009). This disease often goes undetected, given its asymptomatic nature, but long-term effects include chronic kidney disease, renal failure, and death (Prager et al., 2013; Avalos-Téllez et al., 2016), which could explain the high prevalence of genitourinary disorders. Leptospirosis epizootics in 1984, 1988, and 1994 occurred in autumn after El Niño events (1982-83; 1986-87; 1991-93) in coast of California; past studies suggested a temporal relation between Leptospira sp. survival and climate changes; it has also been suggested that environmental changes alter the host population susceptibility to other pathogens instead; thus disease outbreaks result from weakened host immunity rather than increased pathogen availability (Gulland et al., 1996).

On the other hand, parasitic diseases represent a turning factor in the regulation of marine mammal populations, both on an ecological and evolutionary scale (Raga et al., 1997; Hrabar et al., 2021). Nematodes are the parasite group most frequently associated with gastrointestinal tract infections, ranging from minor ulcerations to peritonitis and gastric wall perforations (Hrabar et al., 2021). Many identified concurrent inflammatory diseases, such as cholecystitis, gastritis, and enterocolitis, are common findings in wild sea lions and are often linked to parasitism (Dailey, 2001; Colegrove et al., 2009).

California sea lions are exposed to a wide variety of pathogenic agents and remain susceptible to these infections (Sweeney and Gilmartin, 1974). Since most California sea lions documented with multiple lesions are stranded, in rehabilitation, or post-mortem condition, opportunistic pathogen invasion increases significantly. This poses a challenge in diagnosis, as the relationship between some cases and pathogenic agents is often unclear and depends on the individual’s condition (Sweeney and Gilmartin, 1974; Thorthon et al., 1998; Hrabar et al., 2021; Zavala-Norzagaray et al., 2022). It has been suggested that in combination with pollution, climate change, domoic acid poisoning events, seasonal malnutrition during El Niño, and other pathogens, nematode parasite infections may negatively impact pinniped health and increase mortality, although such effects would not typically occur under normal circumstances (Hrabar et al., 2021). However, this hypothesis requires further validation.

Wounds caused by trauma and entanglements have been identified as a factor that could increase susceptibility to infections (Carretta et al., 2017) due to the breakdown of the epithelial barrier, which can serve as an entry route for pathogens (Haulena et al., 2006). The implications of increased entanglements during anomalous warming events have been explored in relation to food scarcity. California sea lions tend to forage farther from the coast during these events (Weise et al., 2006), increasing their likelihood of becoming entangled in abandoned or active fishing gear (Carretta et al., 2011; Keledjian, 2013). Additionally, during El Niño conditions, these individuals are more likely to prey on fish within nets (Greig et al., 2005).

Our current knowledge indicates that most fishing gear, such as nets, monofilament lines, ropes, and packing materials that can be recovered consist of or are derived from plastics and other synthetic materials (Stewart and Yochem, 1987; Hanni and Pyle, 2000; Butterworth, 2016; IMMP, 2022). These materials may exert lethal or sublethal pollution pressure on marine megafauna, although the scope and magnitude of the impact on the population remain largely unknown and could exceed the current estimates (Jepsen and de Bruyn, 2019; Allyn and Scordino, 2020; Senko et al., 2020).

Other contaminants recorded in smaller quantities were POPs, heavy metals and elements, oils, and paints. The data collected for this review do not reflect severe intoxication in individuals, as none showed clinical signs of poisoning. Instead, these findings presented reports of contaminant presence in various organs or tissues, potential health associations, or regional exposure patterns (Harper et al., 2007; Blasius and Goodmanlowe, 2008; Randhawa et al., 2015; McHuron et al., 2016). These contaminants enter the ocean through agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition, and municipal wastewater treatment plants, reaching the sea lions via biomagnification (Bay et al., 2003; Ylitalo et al., 2005; McHuron et al., 2016; Szteren et al., 2023).

The presence of other contaminants like heavy metals and POPs could influence the individual’s response during an intoxication period with domoic acid, affecting other organs like the liver, kidneys, and general body condition (Harper et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2008). Correlations have been observed between animals dying from suspected domoic acid poisoning and significantly higher cadmium concentrations in their liver and kidney tissues, compared to those dying from infectious diseases or trauma, whose liver mercury concentrations were significantly higher (Harper et al., 2007). Other associations indicate that individuals regularly exposed to domoic acid experience body mass loss. This situation was associated with higher POP concentrations in fat, while mass gain resulted in a decrease in POP levels, suggesting a dynamic fluctuation of contaminants during physiological changes (Hall et al., 2008).

Though not a contaminant, domoic acid is the leading cause of California sea lions strandings due to intoxication (Mancia et al., 2012), provoking both morbidity and mortality, with acute and chronic cases which represent 63.5% and 36.5% of incidents, respectively (McClain et al., 2023). California sea lions are frequently exposed to domoic acid through the consumption of contaminated prey in their diet, like sardines and anchovies (Scholin et al., 2000). This exposure triggers both acute and chronic effects (Gulland et al., 2002; Mancia et al., 2012; Ghosh et al., 2024), affecting mainly the nervous system, causing persistent seizures, ataxia, reduced olfactory and auditory responsiveness, compulsive scratching, and sometimes aggressiveness after exposure (Gulland et al., 2002; Cook et al., 2011; De Maio et al., 2018; McClain et al., 2023). Domoic acid can also be the cause of reproductive failures, such as abortions and cardiomyopathies (Silvagni et al., 2005; Brodie et al., 2006; Zabka et al., 2009). These cases were documented in this review and presented as pregnancy anomalies and other nervous, circulatory, or hematopoietic system disorders.

Some studies have found that POPs have implications for sea lion health by being linked to increased cancer and other infectious diseases (Harper et al., 2007; Gulland et al., 2020; Deming et al., 2021). In 2007, Harper et al. observed that individuals with infectious diseases had higher molybdenum and zinc concentrations in liver tissues compared to animals that died from other causes. Harper et al. (2007) argue this could be the result of physiological stress and fasting, which often accompany disease processes. This can alter metabolic activity and induce the migration of cellular substances such as heavy metals (Harper et al., 2007). In addition, Deming et al. (2021) and Gulland et al. (2020) provide evidence that herpesvirus infection (OtHV1) plays a critical role in the likelihood of carcinoma occurrence, and that higher blubber contaminant concentrations are associated with increased odds of cancer (Gulland et al., 2020). This relationship between contaminant burden and carcinoma occurrence may arise because certain chemicals can induce neoplasia directly through DNA damage, act as tumor promoters, or cause immune suppression that facilitates infection with oncogenic viruses (Robertson and Hansen, 2020; Gulland et al., 2020).

California sea lions have been established as a model for cancer research due to the high prevalence of the disease in their population (Browning et al., 2015). The most prevalent cancer, according to our records, is urogenital cancer, which is the most commonly known cancer in California sea lions (Gulland et al., 2020; Pereida-Aguilar et al., 2023). The discovery of the association between the OtHV1 virus and urogenital cancer is relatively recent (Gulland et al., 2020), so we cannot rule out its influence in past cases where cancer was documented but the virus was not tested. It is well known that poor nutritional status can increase susceptibility to contracting a viral infection (Kelly et al., 2005). And also is known that some contaminants like PCBs have been linked to immune suppression in marine mammals (Williams et al., 2020) and also are recognized as carcinogens (Gulland et al., 2020).

Among other diseases, temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJ-OA) showed the highest prevalence. This condition is highly prevalent in sea lions and can play a significant role in their morbidity and mortality (Arzi et al., 2015a, 2015b). Although its exact causes are still unclear (Rickert et al., 2021), potential contributing factors have been suggested to include trauma, abnormal morphology, acute or chronic overloading, changes in chewing patterns, or genetic influences (Arzi et al., 2015b).

Physiological condition and nutritional status influence the susceptibility of marine mammals to stressful environmental factors (including pathogens, pollutants, and harmful algal bloom toxins), which can lead to mortality through various immediate causes such as infectious diseases, intraspecific aggression, intoxication, and other pathological conditions (Carretta et al., 2017). The interplay between these causal factors and external drivers is complex and not yet fully understood. Our current findings demonstrate significant relationships between external factors (like climate change and fisheries) and California sea lion health. These factors contribute to the increasing disease prevalence, such as leptospirosis, frequency of HABs, and UMEs, among others. However, further research is needed to explore these connections fully.

Stranding data are inherently biased because they primarily represent individuals that are sick, injured, dead, or weak enough to wash ashore, and therefore do not offer a representative sample of the wild population. This bias skews the apparent prevalence of different health conditions and can lead to an overrepresentation of visibly debilitating conditions, such as malnutrition, which is often the proximate cause of stranding. Practical limitations, including mass strandings, remote locations, limited personnel, time restrictions, logistical challenges, and rapid carcass decomposition, frequently prevent comprehensive necropsies or further diagnostic investigation, resulting in many cases being reported only with Level A data, which cover basic publicly available information but do not include analytical results. Consequently, the most apparent condition may be recorded as the primary cause of stranding or death, even if underlying diseases remain undetected. Conversely, this same bias causes an underrepresentation of conditions less likely to lead to strandings, such as internal tumors or sublethal toxicosis, which may go unnoticed without systematic examinations or may never reach the shore. These limitations can ultimately distort the perceived health status of the population (Jauniaux et al., 2019; NOAA Fisheries, 2020, 2023).

The literature review revealed that the health of California sea lions is affected by a complex interaction of physiological, nutritional, and environmental factors. What remains to be explored is how climatic anomalies influence sea lion susceptibility to acquiring an infectious disease, the effect of contaminants, and the prevalence of other diseases not directly related to climate variability. Although these reports provide valuable insights, these health outcomes may also be influenced by other social, economic, or political factors that have yet to be considered.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Data obtained from published articles and public databases.

Author contributions

YR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. LP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Spatial Analysis Laboratory (Laboratorio de Análisis Espaciales) of the Institute of Biology, UNAM (Instituto de Biología, UNAM), the Faculty of Sciences, UNAM (Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM), and the National Polytechnic Institute (Instituto Politécnico Nacional, IPN).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1694768/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Acevedo-Whitehouse K. de la Cueva H. Gulland F. M. Aurioles-Gamboa D. Arellano-Carbajal F. Suarez-Güemes F. et al (2003). Evidence of Leptospira interrogans infection in California sea lion pups from the Gulf of California. J. Wildl. Dis.39, 145–151. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-39.1.145

2

Adame K. Elorriaga-Verplancken F. R. Beier E. Acevedo-Whitehouse K. A. Pardo M. A. (2020). The demographic decline of a sea lion population followed multi-decadal sea surface warming. Sci. Rep.10, 67534. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67534-0

3

Ainsworth T. D. Hurd C. L. Gates R. D. Boyd P. W. (2019). How do we overcome abrupt degradation of marine ecosystems and meet the challenge of heat waves and climate extremes? Glob. Change Biol.26, 343–354. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14901

4

Allyn E. M. Scordino J. J. (2020). Entanglement rates and haulout abundance trends of Steller (Eumetopias jubatus) and California (Zalophus californianus) sea lions on the north coast of Washington State. PloS One15, e0237178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237178

5

Arzi B. Murphy M. K. Leale D. M. Vapniarsky-Arzi N. Verstraete F. J. M. (2015a). The temporomandibular joint of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): Part 2 – osteoarthritic changes. Arch. Oral. Biol.60, 216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.09.005

6

Arzi B. Leale D. M. Sinai N. L. Kass P. H. Lin A. Verstraete F. J. M. et al . (2015b). The temporomandibular joint of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): Part 1 – characterisation in health and disease. Arch. Oral. Biol.60, 208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.09.004

7

Aurioles D. Le Boeuf B. J. (1991). “ Effects of the El Niño 1982–83 on California sea lions in Mexico,” in Ecological Studies ( Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg), 112–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76398-4_12

8

Avalos-Téllez R. Carrillo-Casas E. M. Atilano-López D. Godínez-Reyes C. R. Díaz-Aparicio E. Ramírez-Delgado D. et al . (2016). Pathogenic Leptospira serovars in free-living sea lions in the Gulf of California and along the Baja California coast of Mexico. J. Wildl. Dis.52, 199–208. doi: 10.7589/2015-06-133

9

Bal P. Tulloch A. I. Addison P. F. McDonald-Madden E. Rhodes J. R. (2018). Selecting indicator species for biodiversity management. Front. Ecol. Environ.16, 589–598. doi: 10.1002/fee.1972

10

Banuet-Martínez M. Aquino E. Elorriaga-Verplancken F. Flores-Morán A. García O. Camacho M. et al (2017). Climatic anomaly affects the immune competence of California sea lions. PloS One12, e0179359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179359

11

Bay S. M. Zeng E. Y. Lorenson T. D. Tran K. Alexander C. (2003). Temporal and spatial distributions of contaminants in sediments of Santa Monica Bay, California. Mar. Environ. Res.56, 255–276. doi: 10.1016/S0141-1136(02)00334-3

12

Berry E. S. Skilling D. E. Barlough J. E. Vedros N. A. Gage L. J. Smith A. W. (1990). New marine calicivirus serotype infective for swine. Am. J. Vet. Res.51 (8), 1184–1187. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.1990.51.08.1184

13

Blasius M. E. Goodmanlowe G. D. (2008). Contaminants still high in top-level carnivores in the Southern California Bight: Levels of DDT and PCBs in resident and transient pinnipeds. Mar. pollut. Bull.56, 1973–1982. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.08.011

14

Boesch D. F. (2000). Measuring the health of the Chesapeake Bay: Toward integration and prediction. Environ. Res.82, 134–142. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1999.4010

15

Bonde R. K. Aguirre A. A. Powell J. (2004). Manatees as sentinels of marine ecosystem health: Are they the 2000-pound canaries? EcoHealth1, 255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10393-004-0095-5

16

Boorse C. (1977). Health as a theoretical concept. Philos. Sci.44, 542–573. doi: 10.1086/288768

17

Boorse C. (2011). “ Concepts of health and disease,” in Handbook of the Philosophy of Medicine. Eds. SchrammeT.EdwardsS. ( Elsevier, Amsterdam), 13–64. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-51787-6.50002-7

18

Brodie E. C. Gulland F. M. Greig D. J. Hunter M. Jaakola J. Leger J. St et al . (2006). Domoic acid causes reproductive failure in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). Mar. Mamm. Sci.22, 700–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00045.x

19

Browning H. M. Gulland F. M. D. Hammond J. A. Colegrove K. M. Hall A. J. (2015). Common cancer in a wild animal: The California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) as an emerging model for carcinogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B Biol. Sci.370, 20140228. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0228

20

Butterworth A. (2016). A review of the welfare impact on pinnipeds of plastic marine debris. Front. Mar. Sci.3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00149

21

Cameron C. E. Zuerner R. L. Raverty S. Colegrove K. M. Norman S. A. Lambourn D. M. et al . (2008). Detection of pathogenic Leptospira bacteria in pinniped populations via PCR and identification of a source of transmission for zoonotic leptospirosis in the marine environment. J. Clin. Microbiol.46, 1728–1733. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02022-07

22

Carretta J. V. Oleson E. M. Lang A. R. Weller D. W. Baker J. D. Muto M. et al . (2017). U.S. Pacific marine mammal stock assessments: 2016. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-SWFSC-577 (Washington, DC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). doi: 10.7289/V5/TM-SWFSC-577

23

Cavole L. Demko A. Diner R. Giddings A. Koester I. Pagniello C. et al . (2016). Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the Northeast Pacific: Winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography29, 273–285. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2016.32

24

Clark‐Wolf T. J. Holt K. A. Johansson E. Nisi A. C. Rafiq K. West L. et al . (2024). The capacity of sentinel species to detect changes in environmental conditions and ecosystem structure. J. Appl. Ecol.61, 1638–1648. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.14669

25

Colegrove K. M. Gulland F. M. D. Harr K. Naydan D. K. Lowenstine L. J. (2009). Pathological features of amyloidosis in stranded California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). J. Comp. Pathol.140, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2008.08.003

26

Cook P. Reichmuth C. Gulland F. (2011). Rapid behavioural diagnosis of domoic acid toxicosis in California sea lions. Biol. Lett.7, 536–538. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0127

27

Costanza R. (2012). Ecosystem health and ecological engineering. Ecol. Eng.45, 24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.03.023

28

Costanza R. Mageau M. (1999). What is a healthy ecosystem? Aquat. Ecol.33, 105–115. doi: 10.1023/A:1009930313242

29

Crisci C. Bensoussan N. Romano J. Garrabou J. (2011). Temperature anomalies and mortality events in marine communities: Insights on factors behind differential mortality impacts in the NW Mediterranean. PloS One6, e23814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023814

30

Dailey M. D. (2001). “ Parasitic diseases,” in CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine, 2nd ed. Eds. DieraufL. A.GullandF. M. D. ( CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL), 357–379.

31

De Maio L. M. Cook P. F. Reichmuth C. Gulland F. M. (2018). The evaluation of olfaction in stranded California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) and its relevance to domoic acid toxicosis. Aquat. Mamm.44, 231–238. doi: 10.1578/AM.44.3.2018.231

32

Deming A. C. Wellehan J. F. X. Colegrove K. M. Hall A. Luff J. Lowenstine L. et al . (2021). ‘Unlocking the role of a genital herpesvirus, Otarine herpesvirus 1, in California Sea Lion Cervical Cancer’. Animals11, 491. doi: 10.3390/ani11020491

33

DeRango E. Prager K. Greig D. Hooper A. Crocker D. (2019). Climate variability and life history impact stress, thyroid, and immune markers in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) during El Niño conditions. Conserv. Physiol.7, coz010. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coz010

34

Dierauf L. A. Lowenstine L. J. Jerome C. (1981). Viral hepatitis (adenovirus) in California sea lion. J. Am. Veterinary Med. Assoc.179, 1194–1197. doi: 10.2460/javma.1981.179.11.1194

35

Elorriaga-Verplancken F. Sierra-Rodríguez G. Rosales‐Nanduca H. Acevedo-Whitehouse K. Sandoval-Sierra J. (2016). Impact of the 2015 El Niño–Southern Oscillation on the abundance and foraging habits of Guadalupe fur seals and California sea lions from the San Benito Archipelago, Mexico. PloS One11, e0155034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155034

36

Elorriaga-Verplancken F. R. Ferretto G. Angell O. C. (2015). Current status of the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) and the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) at the San Benito Archipelago, Mexico. Cienc. Mar.41, 269–281. doi: 10.7773/cm.v41i4.2545

37

Engel G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science196, 129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

38

Ghosh G. Neely B. Bland A. Whitmer E. Field C. Duignan P. et al . (2024). Identification of candidate protein biomarkers associated with domoic acid toxicosis in cerebrospinal fluid of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). J. Proteome Res.23, 2419–2430. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c00103

39

Godínez Reyes C. Santos del Prado Gasca K. Zepeda López H. Aguirre A. Anderson D. W. Parás González A. et al . (2006). Condición de salud de aves marinas y lobos marinos en islas del norte del Golfo de California, México. Gac. Ecol.81, 31–45.

40

Goldstein T. Colegrove K. M. Hanson M. Gulland F. M. (2011). Isolation of a novel adenovirus from California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Dis. Aquat. Organisms94, 243–248. doi: 10.3354/dao02321

41

Greig D. J. Gulland F. M. Kreuder C. (2005). A decade of live California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) strandings along the central California coast: Causes and trends 1991–2000. Aquat. Mamm.31, 11–22. doi: 10.1578/AM.31.1.2005.11

42

Gulland F. M. (1999). Stranded seals: Important sentinels. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc.214, 1191–1192.

43

Gulland F. M. Koski M. Lowenstine L. J. Colagross A. Morgan L. Spraker T. (1996). Leptospirosis in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) stranded along the central California coast 1981–1994. J. Wildl. Dis.32, 572–580. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-32.4.572

44

Gulland F. M. Haulena M. Fauquier D. Langlois G. Lander M. E. Zabka T. et al . (2002). Domoic acid toxicity in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): Clinical signs, treatment and survival. Vet. Rec.150, 475–480. doi: 10.1136/vr.150.15.475

45

Gulland F. M. Hall A. J. Ylitalo G. M. Colegrove K. M. Norris T. Duignan P. J. et al . (2020). Persistent contaminants and herpesvirus OTHV1 are positively associated with cancer in wild California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.602565

46

Hall A. J. Gulland F. M. D. Ames J. A. Zabka T. S. Colegrove K. M. (2008). Changes in blubber contaminant concentrations in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) associated with weight loss and gain during rehabilitation. Environ. Sci. Technol.42, 4181–4187. doi: 10.1021/es702685p

47

Hanni K. D. Pyle P. (2000). Entanglement of pinnipeds in synthetic materials at South-East Farallon Island, California 1976–1998. Mar. pollut. Bull.40, 1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(00)00050-3

48

Harper E. R. DeLong R. L. Gulland F. M. D. Shapiro D. B. Becker P. R. (2007). Tissue heavy metal concentrations of stranded California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) in Southern California. Environ. pollut.147, 677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.09.013

49

Haulena M. Gulland F. M. D. Hammond J. Colagross-Schouten A. Spraker T. R. (2006). Lesions associated with a novel Mycoplasma sp. in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) undergoing rehabilitation. J. Wildl. Dis.42, 40–45. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-42.1.40

50

Havelka M. Lucanin J. D. Lucanin D. (2009). Biopsychosocial model—the integrated approach to health and disease. Collegium Antropol.33, 303–310.

51

Hazen E. L. Abrahms B. Brodie S. Carroll G. Jacox M. G. Savoca M. S. et al . (2019). Marine top predators as climate and ecosystem sentinels. Front. Ecol. Environ.17, 565–574. doi: 10.1002/fee.2125

52

Hernández-Camacho C. Pelayo-González L. Rosas-Hernández M. (2021). “ California sea lion (Zalophus californianus),” in Ecology and Conservation of Pinnipeds in Latin America. Eds. HeckelG.SchrammY. ( Springer, Cham), 121–123.

53

Hrabar J. Smodlaka H. Rasouli-Dogaheh S. Petrić M. Trumbić Ž. Palmer L. et al . (2021). Phylogeny and pathology of anisakids parasitizing stranded California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) in Southern California. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.636626

54

International Marine Mammal Project (2022). The plastics plague. Marine mammals and our oceans in peril (California: Earth Island Institute). Available online at: https://www.earthisland.org/immp/assets/IMMP-Plastics-Report-Digital.pdf (Accessed November 18, 2025).

55

Jauniaux T. André M. Dabin W. (2019). Marine Mammals Stranding: Guidelines for post-mortem investigations of Cetaceans & Pinnipeds, & 13rd Cetacean Necropsy Workshop: Special Issue on Necropsy and samplings (Liège 2019) (Liège: Presses de la Faculté de Médecine vétérinaire de l’Université de Liège).

56

Jepsen E. M. de Bruyn P. J. N. (2019). Pinniped entanglement in oceanic plastic pollution: A global review. Mar. pollut. Bull.145, 295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.05.042

57

Keledjian A. (2013). The impacts of El Niño conditions on California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) fisheries interactions: Predicting spatial and temporal hotspots along the California coast. Aquat. Mamm.39, 221–232. doi: 10.1578/am.39.3.2013.221

58

Kelly T. R. Gulland F. M. D. Miller M. A. (2005). Metastrongyloid nematode (Otostrongylus circumlitus) infection in a stranded California sea lion (Zalophus californianus)—a new host-parasite association. J. Wildl. Dis.41, 593–598. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-41.3.593

59

Koch M. S. Silva V. D. Bracarense A. P. Domit C. (2018). Aspectos ambientais e infecciosos relacionados à imunossupressão em cetáceos: Uma breve revisão. Semina Ciênc Agrárias39, 2897–2917. doi: 10.5433/1679-0359.2018v39n6p2897

60

Laake J. L. Lowry M. S. DeLong R. L. Melin S. R. Carretta J. V. (2018). Population growth and status of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). J. Wildl. Manag.82, 583–595. doi: 10.1002/jwmg.21405

61

Lowry M. S. Jaime E. M. Moore J. E. (2021). Abundance and distribution of pinnipeds at the Channel Islands in southern California, central and northern California, and southern Oregon during summer 2016–2019. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-656. doi: 10.25923/6qhf-0z55

62

Mallick J. AlQadhi S. Talukdar S. Pradhan B. Bindajam A. Islam A. et al . (2021). A novel technique for modeling ecosystem health condition: A case study in Saudi Arabia. Remote Sens.13, 2632. doi: 10.3390/rs13132632

63

Mancia A. Ryan J. C. Chapman R. W. Wu Q. Warr G. W. Gulland F. M. D. et al . (2012). Health status, infection and disease in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) studied using a canine microarray platform and machine-learning approaches. Dev. Comp. Immunol.36, 629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.10.011

64

Manrique-Escobar C. A. Pappalardo C. M. Guida D. (2022). On the analytical and computational methodologies for modelling two-wheeled vehicles within the multibody dynamics framework: a systematic literature review. J. Appl. Comput. Mechanics.8 (1), 153–181. doi: 10.22055/jacm.2021.37935.3118

65

Marneweck C. J. Loveridge A. J. Macdonald D. W. (2022). Middle-out ecology: Small carnivores as sentinels of global change. Mamm. Rev.52, 471–479. doi: 10.1111/mam.12300

66

Masper A. (2019). Review of California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) abundance, and population dynamics in the Gulf of California. Rev. Biol. Trop.67, 833–849. doi: 10.15517/rbt.v67i4.35965

67

McClain A. M. Field C. L. Norris T. A. Borremans B. Duignan P. J. Johnson S. P. et al . (2023). The symptomatology and diagnosis of domoic acid toxicosis in stranded California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): A review and evaluation of 20 years of cases to guide prognosis. Front. Vet. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1245864

68

McClatchie S. Field J. Thompson A. R. Gerrodette T. Lowry M. (2016). Food limitation of sea lion pups and the decline of forage off central and Southern California. R Soc. Open Sci.3, 150628. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150628

69

McHuron E. A. Robinson P. W. Simmons S. E. Kuhn C. E. Fowler M. Costa D. P. (2016). Foraging strategies of a generalist marine predator inhabiting a dynamic environment. Oecologia182, 995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3732-0

70

Melin S. R. Orr A. J. Harris J. D. Laake J. L. DeLong R. L. (2012). California sea lions: An indicator for integrated ecosystem assessment. Calif. Coop Ocean Fish Investig. Rep.53, 140–152.

71

Melin S. Orr A. J. Harris J. D. Laake J. L. DeLong R. L. Gulland F. M. D. et al . (2010). Unprecedented mortality of California sea lion pups associated with anomalous oceanographic conditions along the central California coast in 2009. Calif. Coop Ocean Fish Investig. Rep.53, 182–194.

72

Neely B. A. Prager K. C. Bland A. M. Fontaine C. Gulland F. M. Janech M. G. (2018). Proteomic analysis of urine from California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): A resource for urinary biomarker discovery. J. Proteome Res.17, 3281–3291. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00416

73

NOAA Fisheries (2022). 2013–2016 California Sea Lion Unusual Mortality Event ( NOAA). Available online at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/frequent-questions-2013-2016-california-sea-lion-unusual-mortality:~:text=(SWFSC)%20conducted%20an%20annual%20mid,weaning%20weights%20of%20their%20pups (Accessed October 13, 2024).

74

NOAA Fisheries (2023). Frequent questions-necropsies (animal autopsies) of marine mammals ( NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA). Available online at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/frequent-questions-necropsies-animal-autopsies-marine-mammals (Accessed September 22, 2024).

75

NOOA Fisheries (2020). Marine Mammal Stranding Report - Level A. Examiners Guide 2020 Revision (United States: NOOA: Silver Spring, MD, USA). Available online at: https://media.fisheries.noaa.gov/dam-migration/examiners_guide_2023.pdf.

76

Norman S. A. DiGiacomo R. F. Gulland F. M. Meschke J. S. Lowry M. S. (2008). Risk factors for an outbreak of leptospirosis in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) in Californi. J. Wildl. Dis.44, 837–844. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.4.837

77

Pelayo-González L. (2018). Efecto de variables ambientales en el número de nacimientos de lobo marino de California (Zalophus californianus) en el Golfo de California. Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas CICIMAR-IPN.

78

Pelayo-González L. González-Rodríguez E. Ramos-Rodríguez A. Hernández-Camacho C. J. (2021a). California sea lion population decline at the southern limit of its distribution during warm regimes in the Pacific Ocean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.48, 102040. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2021.102040

79

Pelayo‐González L. Hernández‐Camacho C. J. Aurioles‐Gamboa D. Gallo‐Reynoso J. P. Barba‐Acuña I. D. Godínez‐Reyes C. (2021b). Effect of environmental variables on the number of births at California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) rookeries throughout the Gulf of California, Mexico. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.31, 1730–1748. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3545

80

Pereida-Aguilar J. C. Barragán-Vargas C. Domínguez-Sánchez C. Álvarez-Martínez R. C. Acevedo-Whitehouse K. A. (2023). Bacterial dysbiosis and epithelial status of the California Sea Lion (Zalophus californianus) in the Gulf of California. Infection, Genetics and Evolution113, 105474. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2023.105474

81

Pozas-Franco A. L. (2022). The influence of diet quality on the divergent population trends of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) in the Channel Islands and the Gulf of California. University of British Columbia. Available online at: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0422139.

82

Prager K. Greig D. Alt D. Galloway R. Hornsby R. Palmer L. et al . (2013). Asymptomatic and chronic carriage of Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). Vet. Microbiol.164, 177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.01.032

83

Raga J. A. Balbuena J. A. Aznar J. Fernández M. (1997). The impact of parasites on marine mammals: a review. Parassitologia39, 293–296.

84

Randhawa N. Gulland F. Ylitalo G. M. DeLong R. Mazet J. A. K. (2015). Sentinel California sea lions provide insight into legacy organochlorine exposure trends and their association with cancer and infectious disease. One Health1, 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.08.003

85

Rickert S. S. Kass P. H. Verstraete F. J. (2021). Temporomandibular joint pathology of wild carnivores in the Western USA. Front. Vet. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.657381

86

Robertson L. W. Hansen L. (Eds.) (2020). PCBs: Recent Advances in Environmental Toxicology and Health Effects: Medicine and Health Sciences, 2 Edn (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press), 8.

87

Robinson H. Thayer J. Sydeman W. J. Weise M. (2018). Changes in California sea lion diet during a period of substantial climate variability. Mar. Biol.165, 10. doi: 10.1007/s00227-018-3424-x

88

Rodríguez-Martínez M. I. Moreno-Sánchez X. G. Moncayo-Estrada R. Elorriaga-Verplancken F. R. (2024). Impact of anomalous ocean warming on the abundance and foraging habits of the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) from the San Benito Archipelago in the Mexican Pacific. J. Mammal.106, 72–84. doi: 10.1093/jmammal/gyae122

89

Rombouts I. Beaugrand G. Artigas L. F. Dauvin J.-C. Gevaert F. Goberville E. et al . (2013). Evaluating marine ecosystem health: Case studies of indicators using direct observations and modelling methods. Ecol. Indic.24, 353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.07.001

90

Sanderson C. E. Alexander K. A. (2020). Unchartered waters: Climate change likely to intensify infectious disease outbreaks causing mass mortality events in marine mammals. Glob. Change Biol.26, 4284–4301. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15163

91

Scholin C. A. Gulland F. Doucette G. J. Benson S. Busman M. Chavez F. P. et al . (2000). Mortality of sea lions along the central California coast linked to a toxic diatom bloom. Nature403, 80–84. doi: 10.1038/47481

92

Senko J. Nelms S. Reavis J. Witherington B. Godley B. Wallace B. (2020). Understanding individual and population-level effects of plastic pollution on marine megafauna. Endang. Species Res.43, 234–252. doi: 10.3354/esr01064

93

Shuert C. R. Skinner J. P. Mellish J. E. (2015). Weighing our measures: Approach-appropriate modeling of body composition in juvenile Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus). Can. J. Zool.93, 177–180. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2014-0174

94

Silvagni P. A. Lowenstine L. J. Spraker T. Lipscomb T. P. Gulland F. M. (2005). Pathology of domoic acid toxicity in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). Vet. Pathol.42, 184–191. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-2-184

95

Smith A. W. Akers T. G. Latham A. B. Skilling D. E. Bray H. L . (1979). A new calicivirus isolated from a Marine Mammal. Archives Virol.61 (3), 255–259. doi: 10.1007/bf01318061

96

Smith J. Cram J. A. Berndt M. P. Hoard V. Shultz D. Deming A. C. (2023). Quantifying the linkages between California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) strandings and particulate domoic acid concentrations at piers across Southern California. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1278293

97

Stewart B. S. Yochem P. K. (1987). Entanglement of pinnipeds in synthetic debris and fishing net and line fragments at San Nicolas and San Miguel Islands, California 1978–1986. Mar. pollut. Bull.18, 336–339. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(87)80021-8

98

Sweeney J. C. Gilmartin W. G. (1974). Survey of diseases in free-living California sea lions. J. Wildl. Dis.10, 370–376. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-10.4.370

99

Szteren D. Aurioles-Gamboa D. Campos-Villegas L. E. Alava J. J. (2023). Metal-specific biomagnification and trophic dilution in the coastal foodweb of the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) off Bahía Magdalena, Mexico: The role of the benthic-pelagic foodweb in the trophic transfer of trace and toxic metals. Mar. pollut. Bull.194, 115263. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115263

100

Tabor G. Aguirre A. A. (2004). Ecosystem health and sentinel species: Adding an ecological element to the proverbial “Canary in the mineshaft”? EcoHealth1, 226–228. doi: 10.1007/s10393-004-0092-8

101

Thorthon S. M. Nolan S. Gulland F. M. D. (1998). Bacterial isolates from California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), and northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) admitted to a rehabilitation center along the central California coast 1994–1995. J. Zoo Wildl. Med.29, 171–176. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20095741. October 01 2025

102

Trillmich F. Limberger D. (1985). Drastic effects of El Niño on Galapagos pinnipeds. Oecologia67, 19–22. doi: 10.1007/bf00378445

103

Tyreman S. (2006). Causes of illness in clinical practice: A conceptual exploration. Med. Health Care Philos.9, 3. doi: 10.1007/s11019-006-9006-6

104

UN (2023). How is climate change impacting the world’s ocean ( United Nations). Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/ocean-impacts.

105

U.S. Pacific Fleet Environmental Readiness Division (2024). U.S. Navy Marine Species Density Database Phase IV for the Hawaii-California Training and Testing Study Area (Pearl Harbor, HI: U.S. Department of the Navy), 320.

106