Abstract

Introduction:

A group of brown algae, known as rockweeds, influence rocky shore ecosystems as ‘foundation species’ by increasing habitat complexity and ameliorating environmental stressors for other species. Rocky shore habitats shaped by foundational canopy-forming rockweed species are threatened by human disturbance and climate change impacts. Thus, it is of pressing conservation concern to understand how changes in rockweed densities lead to shifts in associated community structure.

Methods:

Here, we tested the hypothesis that higher cover of rockweed canopy correlates with higher cover, richness, and stability of understory communities, using the unique study system of California’s coast, where several species of rockweed co-occur within the mid-to-high intertidal and are experiencing severe declines. With restoration approaches being tested across taxa, we compared the role of three dominant Californian rockweed species (Silvetia compressa, Fucus distichus, Pelvetiopsis limitata) on understory composition and stability. We analyzed eleven-year time-series data across 37 sites throughout California, with plots consistently sampling both benthic and canopy communities.

Results:

We found a positive impact of rockweed cover on total benthic community cover for all three rockweed taxa. There was also a positive impact of rockweed cover on benthic richness, diversity, and stability, although this relationship was only significant for certain rockweed species. All three rockweed taxa showed a positive association with non-coralline crusts, otherwise there were species-specific positive associations with benthic taxa such as limpets, barnacles, and red turf algae.

Discussion:

Our findings provide evidence of Californian rockweed species playing a foundational role in the rocky intertidal as their canopy changes benthic community structure. The positive impact of rockweed cover was most pronounced in S. compressa and P. limitata, which suggests that these species offer greater protection against physical stresses as they exist at higher tidal elevations and lower latitudes where desiccation stress may be stronger. As restoration efforts continue to aid declining Californian rockweed populations, these findings can inform conservation management to target sites and species to have the largest benefits to ecosystems and coastal resilience.

Introduction

Within the complex mosaic of interactions in marine ecosystems, some species are recognized as having disproportionately large roles in determining the structure of the community. Termed ‘foundation species’, these habitat-forming organisms modify the physical environment via their abundance and physical structure (Dayton, 1975; Angelini et al., 2011). Particularly important within the marine environment (Wernberg et al., 2024), examples of marine foundation species include corals, oysters, seagrasses, mangroves, and kelps (Smith et al., 2024). Foundation species have newfound importance as they may be able to mitigate negative climate change impacts (Miner et al., 2021; van der Heide et al., 2021). However, marine foundation species themselves are experiencing declines due to climate change drivers as well as other anthropogenic threats (Wernberg et al., 2024). Thus, foundation species are of conservation concern and increasingly targeted for restoration efforts (Heineke et al., 2023).

Within the rocky intertidal zone, foundation species such as mussels or canopy-forming macroalgae often reduce environmental stress and increase habitat and resource availability to surrounding species (Lilley and Schiel, 2006; Bustamante et al., 2017; Jurgens and Gaylord, 2018; Bittick et al., 2019). In addition, foundation species also shape community composition (i.e., which species are present and their relative abundances) through energy provisioning and increasing the productivity of the ecosystem (Carr, 1994; Graham et al., 2016). The shelter and habitat provided by intertidal foundational macroalgae alters biotic interactions by creating an environment in which certain species, such as obligatory epifauna and desiccation-intolerant species, can survive (Lilley and Schiel, 2006; Monteiro et al., 2019). Thus, foundational macroalgae may facilitate the presence of long-lived taxa over opportunistic species, which should increase understory community stability and resilience (Eriksson et al., 2006; Lilley and Schiel, 2006; Montero-Serra et al., 2018; Thomsen et al., 2024).

While central to the definition of a foundation species (Dayton, 1972), the potential contribution of intertidal foundational macroalgae to community stability has yet to be explicitly examined. Studies have shown that foundation species in other systems can increase community stability either by their own stability allowing the associated community to persist (Stachowicz, 2001; Canion and Heck, 2009; Lamy et al., 2020), or by enhancing species richness (which leads to fluctuations in individual species more likely to be averaged out across the community, i.e., the ‘portfolio effect’; Ives et al., 2000). A common definition of community stability is the product of the stability of individual species and the degree of asynchronous fluctuations among species, commonly measured as the mean divided by the standard deviation of total community biomass or other aggregate abundance metric (µ/, Tilman, 1999). Temporal community stability is often expressed as the inverse of the coefficient of variation in total species cover/abundance (Tilman, 1999). Community stability has been shown to be positively influenced by species richness, termed the diversity-stability relationship (DSR; Tilman and Downing, 1994; Ives and Carpenter, 2007; Thibaut and Connolly, 2013; Cusson et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2023). However, this relationship is not consistently found in nature (Campbell et al., 2011; Houlahan et al., 2018), possibly due to the dominance of abiotic factors outweighing compensatory dynamics among species (Houlahan et al., 2007), or due to diverse communities not responding differentially to ecological variability (McCann, 2000). As foundational species can greatly reduce the abiotic stress species experience, they have the potential to enhance the stability of individual species, as well as to decrease negative interactions between species (Houlahan et al., 2007; Valone and Barber, 2008; Yakovis et al., 2008). This has been shown in subtidal marine ecosystems where the stability of giant kelp, Macosystis pyrifera, positively influences the stability of benthic algae and sessile invertebrate communities through its positive effect on benthic species richness (Lamy et al., 2020). Additionally, Bulleri et al. (2012) found that the experimental removal of rocky intertidal macroalgal canopies led to lower community stability, albeit only within lower latitude sites within Europe.

Due to the natural variability of rocky intertidal systems, there is a clear need for long-term monitoring programs to compliment experimental approaches to assess the impacts of macroalgal foundation species declines on community composition (Hartnoll and Hawkins, 1980; Thompson et al., 2002). Most studies on intertidal foundation species use treatments where the dominant species is removed or transplanted (Melville and Connell, 2001; Stachowicz et al., 2008; Crowe et al., 2013; Fales and Smith, 2022; Viejo et al., 2024), which do not fully capture the natural spatiotemporal variability of these systems, and may undermine the role of biotic and abiotic fluctuations in determining community composition. Many coastal habitat-forming macroalgae have high inter-annual variability in abundance (Altieri and Witman, 2006; Mieszkowska et al., 2020; Giraldo-Ospina et al., 2025), and thus their impact on the stability of associated communities (and importance as a foundation species) may be limited in natural settings over long timescales. Assessing the impacts of canopy-forming macroalgae cover on rocky intertidal community composition through long-term surveys can better capture the direct species interactions and the indirect effects of environmental variability (Steinbeck et al., 2005), but such survey data is often lacking. Furthermore, macroalgal taxa are one of the least studied foundational marine species, with a scarcity of long-term studies characterizing their impacts on rocky intertidal biodiversity (Whitaker et al., 2023; Wernberg et al., 2024).

One group of marine foundation species worthy of more research and conservation attention are brown seaweeds (Phaeophyceae) in the order Fucales (Fucoids), known as rockweeds (Abbott et al., 1992). Rockweeds are canopy-forming macroalgae that can maintain air temperatures up to 16 °C lower and moisture levels up to 3000% higher under rockweed canopy compared to exposed rock surfaces (Beermann et al., 2013), thereby providing shelter from desiccation to other species within the upper intertidal zone (Brawley and Johnson, 1991; Bertness et al., 1999). Canopy-forming macroalgae shape community dynamics and coastal trophic food webs, providing food for a variety of herbivores (Cameron et al., 2024; Kahma et al., 2023). Rockweeds are also highly productive, with Fucus beds accounting for up to 97% of carbon dioxide flux (Bordeyne et al., 2015), and contributing to carbon sequestration (Buck-Wiese et al., 2023). Studies worldwide report lower species diversity, community stability, biomass, and primary productivity following the loss/removal of rockweed (Schiel and Lilley, 2011; Tait and Schiel, 2011; Bulleri et al., 2012). Rockweeds often harbor a diverse community of epifaunal and benthic species and facilitate the presence of long-lived taxa over opportunistic species, both of which should increase the stability and resilience of the community (Sapper and Murray, 2003; Fredriksen et al., 2005; Eriksson et al., 2006; Lilley and Schiel, 2006; Schiel and Lilley, 2011; Lanari et al., 2022).

Globally rockweeds and other macroalgae are in decline (Duarte et al., 2022), often due to unknown causes, but likely a culmination of threats such as urbanization, pollution, habitat loss, harvesting, human trampling, invasive species, and climate change (reviewed in Orfanidis et al., 2021 and Whitaker et al., 2023) In addition to these anthropogenic threats, desiccation at low tides is a prominent natural stressor that can further the declines of rockweed populations (Whitaker et al., 2024; Pereira et al., 2025a, Pereira et al., 2025b; Gljušćić et al., 2025). Of the eastern Pacific rockweed taxa which co-occur in California, Silvetia compressa (Agardh, 1824), Fucus distichus Linnaeus, and several Pelvetiopsis species, all have experienced dramatic declines and extirpations (Whitaker et al., 2023) in association with oil spills (Driskell et al., 2001), desiccating wind events (Whitaker et al., 2024), and unknown impacts (Fales and Smith, 2022). These declines likely have large impacts on rocky intertidal communities, as rockweeds harbor diverse understories. For example, Sapper and Murray (2003) found over 100 species associated with S. compressa in southern California. In addition, Fales and Smith (2022) found that plots with Pelvetiopsis californica cover had significantly more total seaweed cover and higher species richness, compared to adjacent plots lacking P. californica at a site in southern California. These case studies in southern California are noteworthy considering a large proportion of rockweed losses have occurred in this region due to anthropogenic and environmental stressors (Fales and Smith, 2022; Whitaker et al., 2024). While these studies provide insight into the foundational role of certain rockweed species at specific sites, a broad examination of associations between rockweed cover and benthic biodiversity and stability across California’s bioregions and rockweed taxa has never been done.

Due to their importance to rocky shore biodiversity, recent declines, and limited ability for natural recovery (Perkol-Finkel and Airoldi, 2010; Bianchelli et al., 2023; Verdura et al., 2023), rockweeds are candidates for coastal restoration. Rockweed restoration is largely still in its preliminary phase (Waltham et al., 2020). Non-destructive restoration approaches have recently been explored for Mediterranean rockweed species (reviewed in Cebrian et al., 2021), leading to successes such as self-sustaining populations of Cystoseira barbata of roughly 25m2 with densities and size-structure distributions similar to natural reference populations (Verdura et al., 2018). While some restoration efforts have seen positive results in rockweed density and understory biodiversity, it often takes multiple years to see the full recovery of the habitat and ecosystem functioning (Whitaker et al., 2023; Bianchelli et al., 2023). Restoration efforts in California have mainly consisted of transplanting adult plants from donor to recipient sites, resulting in variable survival rates ranging from ~75% (Whitaker et al., 2010; Tronske, 2020) to 0% (Miller et al., 2024). Assessing the effectiveness of these restoration efforts and their ramifications for ecosystem functioning requires a deeper understanding of how rockweed cover influences benthic community composition and stability. This study aims to identify which benthic species are found in association with the different rockweed species along California, which can offer insights into which species will benefit from restoration efforts, as well as nursery species that could facilitate rockweed recruitment and survivorship.

Overall, this study aim is to assess the foundational role of Californian rockweed species and identify species most strongly impacted by rockweed canopy loss using long-term ecological monitoring data consisting of canopy and benthic species cover. More specifically, we examine the following three questions for each rockweed taxa: 1) Does higher rockweed canopy cover lead to higher benthic richness, diversity, and cover? 2) Does having higher rockweed cover or higher stability of rockweed cover lead to higher benthic community stability? 3) How does rockweed canopy loss impact benthic community composition and which species are most impacted by rockweed declines? These questions are compared across three co-distributed rockweed taxa (Silvetia compressa, Fucus distichus, and Pelvetiopsis limitata), but also across bioregions within each rockweed’s distribution, as we expect that the foundational role of rockweeds may differ across species and biogeography. By addressing these questions, we offer explicit tests of the foundational role of Californian rockweeds encompassing natural spatiotemporal variation of intertidal communities. Furthermore, this work provides scientific guidance for future restoration efforts, highlighting species and regions that can be targeted for conservation intervention.

Materials and methods

Data collection

We analyzed data collected by the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe; www.pacificrockyintertidal.org) monitoring program. MARINe is a consortium of government agencies, private organizations, non-profits, and academic institutions which collect long-term ecological data along the Pacific coast of North America. The monitoring program extends from Alaska, USA to Baja, MEX, but we only used data from California (CA), consisting of 37 sites spanning a gradient of environmental conditions. We lack formal metadata on other anthropogenic variables such as visitation, harvesting, nutrient run-off, but the sites do span a range of degree of access, proximity to human built environment (Gleason et al., 2023), as well as marine protection within each ecoregion (see Supplementary Table S1 for protection levels per site). The MARINe sites span well-known biogeographic provinces of California (i.e., ecoregions originally defined by Blanchette et al., 2008), and we kept the MARINe site groupings for our analyses, herewith referred to as the following ‘regions’: ‘CA North’ (Oregon to San Francisco), ‘CA Central’ (San Francisco to Point Conception), and ‘CA South’ (Point Conception to San Diego; Figure 1a). MARINe long-term fixed plots (50 cm × 75 cm) were established at each site, located within common and ecologically important target species assemblages across intertidal zonations. As the location of long-term plots were initially determined based on target species assemblages, they account for between-site differences in tidal zonation, driven by differences in wave exposure and tidal amplitude, allowing for comparisons between similar biological assemblages across sites. Plots were initially placed in areas with maximal abundance of each target species, thus percent cover would initially decrease over time then vary around a long-term mean. We analyzed the ‘layered’ survey data (described below) within these established sites, which began in 2013 (non-layered data goes back to 1999 at some sites). Each site typically contains 3–5 target assemblages, with five replicate plots within each assemblage.

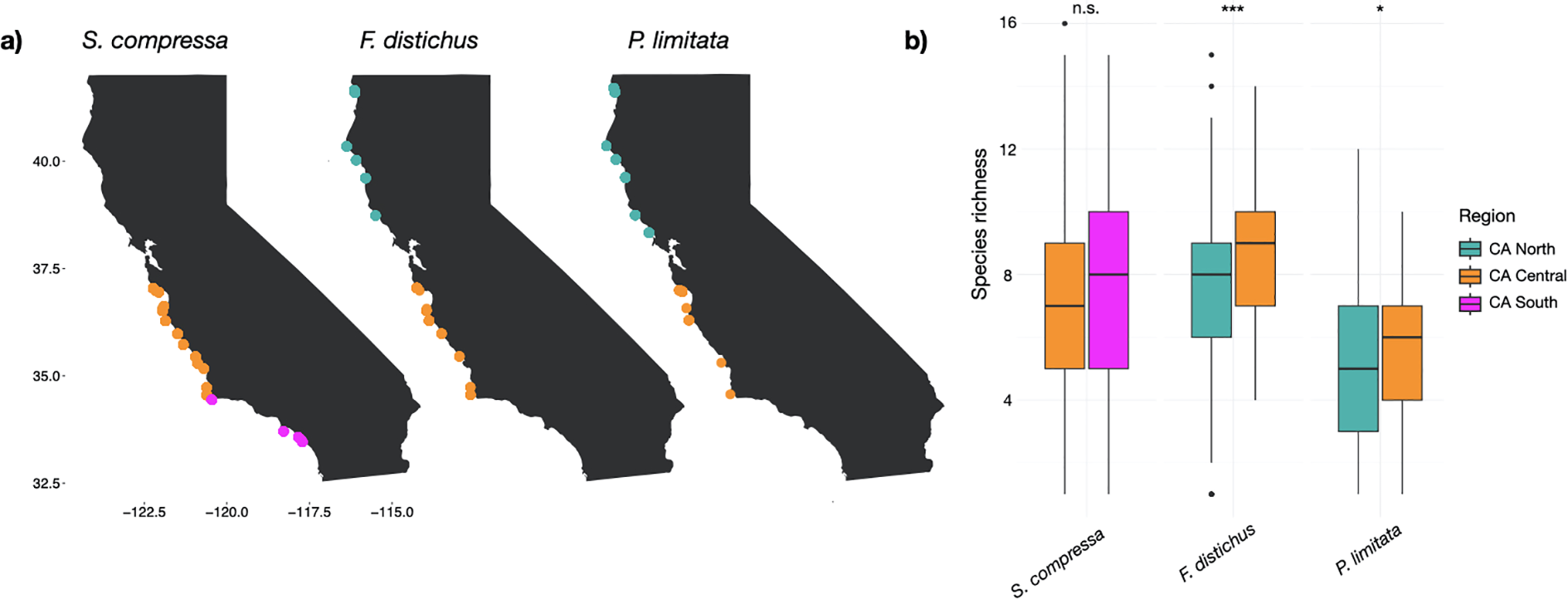

Figure 1

The sample site locations of the MARINe surveys for the three target rockweed species (Silvetia compressa, Fucus distichus, Pelvetiopsis limitata) colored by region (a; see Supplementary Table S1 for site coordinates; data downloaded from https://marine.ucsc.edu/explore-the-data/data-requests/). Mean benthic species richness for survey plots associated with each rockweed species are shown per region, with boxes representing the quartile range, horizontal lines representing the median, whiskers representing the range of values that aren’t outliers, and the dots representing outliers (b). Significance in mean benthic species richness between regions is shown as: ‘n.s.’: p > 0.05, *: p<= 0.05, **: p<= 0.01, ****: p<= 0.0001.

Point-contact surveys were conducted semi-annually (1–2 times per year), from 2013–2023 to record the canopy and benthic communities using a rectangular quadrat grid of 100 uniformly spaced points. As the data spans 11 years, it captures interannual variability, and also captures oscillations such as the 2014–2016 El Niño/Marine Heatwaves (Di Lorenzo and Mantua, 2016), making these long-term data suitable to characterize natural temporal variation in canopy and benthic community composition. Sites varied in the number of years they were sampled within this period ranging from 4 to 11 (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S1). The surveys consisted of recordings of the top-most organisms/substrate (i.e., directly under the quadrat points), while benthic percent cover was the bottom-most species/substrate under each point (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S1). Across all sites, data collection was completed in the field, unless conditions made it impossible.

Bare rock, sand, or tar under canopy species (i.e. the top-most organism) were also recorded. If sand was present, but a species could positively be identified under a thin layer of sand, the species or substrate was recorded. Dead species were also recorded separately with a ‘DEAD’ identifier. The surveys originally included motile species, but an internal analysis by the MARINe group found that their inclusion did not add much additional information (< 1% of explained variation in community composition), and thus was not worth the added effort that it took to survey motile species (pers. comm. Pete Raimondi). If a motile species occurred under a quadrat point, then the organism/substrate underneath them was recorded instead. Sedentary motile invertebrates, such as chitons and limpets, were recorded. Organisms that were difficult to identify to species level were lumped into higher taxonomic groupings. If there were greater than two biological layers, only the non-ephemeral uppermost and lowermost species were recorded.

Data wrangling

The data described above was downloaded and edited in RStudio (Posit team, 2025). Given our focus on rockweeds as foundational canopy, we refer to the recorded top layer as ‘canopy species’ (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S1). Species recorded in the bottom layer are referred to as ‘benthic species’, keeping nomenclature consistent with other studies assessing the influence of fucoid canopy cover on species living beneath it (Bertness et al., 1999; Schiel and Lilley, 2007; Watt and Scrosati, 2013; see Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S2 for full list of benthic species). If there was only a single layer (i.e., a species attached directly to rock), then the bottom layer was recorded in the surveys as NONE. In these cases, we edited the top layer column to be “NONE” and the bottom layer column to be the species identifier. Thus, in the example of a mussel attached to a rock with nothing on top of it, the bottom layer would be the mussel species, and the top layer would be NONE. The exception was when there was a single rockweed species under a quadrat point, we kept the species record as a top layer and retained the bottom layer as NONE. Rockweeds could only be part of the benthos if separate species were reported in the top and bottom layers. Thus, in the example of a single species rockweed canopy over rockweed holdfast, the canopy would be rockweed and the benthic layer would be NONE. Calculations of benthic richness, diversity, and stability excluded all rows with non-living bottom layer records.

We calculated percent cover for each of canopy and benthic species per plot by dividing the number of times the species was recorded under the 100 point quadrat by 100. We filtered the data to only include plots from the vertical range limits that may support rockweed assemblages, which consisted predominantly of three taxa: Silvetia compressa, Fucus distichus, and Pelvetiopsis limitata. We excluded Pelvetiopsis californica plots due to insufficient sampling. Silvetia compressa is found from Humbolt County California to Baja California, F. distichus is distributed from Alaska to central California, and P. limitata is found from British Columbia to central California. Pelvetiopsis species and S. compressa co-occur within the high intertidal, and Pevlevitopsis generally occupies higher tidal elevations than S. compressa (Fales and Smith, 2022). By comparison, F. distichus is found at lower tidal elevations, occupying the upper mid-intertidal (Elsberry and Bracken, 2021). We calculated mean tidal height per species and region and ran one-way ANOVAs with a Tukey post-hoc tests to test if mean tidal height differed between the species per region.

Statistical analyses

We assessed the community composition underneath each rockweed taxa by calculating the average percent cover of each benthic species across plots targeting S. compressa, F. distichus, and P. limitata. To understand how distributional ranges influence understory- overstory relationships, we calculated species presence/absence spanning all plots from all sites, and used the Jaccard similarity index to quantify the similarity in rockweed and benthic species presences (e.g., distributional overlap). The Jaccard similarity index quantifies how alike binary data sets are by comparing the shared values to the total unique values, making it suitable to assess which species have similar presence/absences across sample sites with the three rockweed taxa (Real and Vargas, 1996; Chung et al., 2019).

For each plot we computed species richness and diversity (exponential of Shannon–Wiener diversity index; H’). We ran one-way ANOVAs with a Tukey post-hoc test of multiple groups to test if there are significant differences in species richness and H’ between the three rockweed benthic assemblages. For each of the three rockweed species, we tested whether rockweed canopy (% cover of rockweed in canopy) influences total benthic cover, as well as richness and diversity using linear regressions. Percent cover was calculated per quadrat, site, and year for each of the three rockweed species. Models included species richness, H’, and total benthic percent cover as response variables which allowed us to examine total diversity (i.e., species richness) and proportion-weighted diversity (i.e., H’).

To assess the effects of rockweed canopy cover on benthic cover, richness, and diversity we ran linear mixed-effect models, including rockweed percent cover, region, and the interaction between rockweed cover and region as fixed effects, with spatial variables nested from largest to smallest scale (site/quadrat) as random effects. All models were run separately for each rockweed species, due to the unbalanced sampling as the three species occupy different regions and tidal heights, which would interfere with interpretations of species comparisons. We addressed temporal autocorrelation by initially including ‘correlation=corAR1()’ into the model, which assumes that the correlation between two points in time decreases as the time between them increases (Pickle, 2000). Incorporating an autocorrelation structure did not significantly improve model fit (ANOVA p > 0.05) and thus was left out of the final models. Checking for normality showed that species richness and H’ were normally distributed (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S2), and thus we used a Gaussian distribution. As benthic cover is proportional (values between 0 and 1), these models used a beta distribution with log link. As beta models do not allow for values of 0 and 1, response variable data were transformed using (y * (n − 1) + 0.5)/n; where y is the value of 0 or 1 and n is the sample size (Smithson and Verkuilen, 2006). We ran model diagnostics and visualized goodness-of-fit with Q-Q and residual plots with the simulateResiduals function of the DHARMa R package (Hartig and Hartig, 2017). All models were fitted using the glmmTMB R package (Brooks et al., 2017) with optimal models identified through a backwards selection using the stepAIC function of the MASS R package (Ripley et al., 2013).

We tested the effect of stability of rockweed canopy cover on the stability of total benthic cover with generalized mixed models. In addition to rockweed cover stability, we also tested the effect of the temporal mean of rockweed canopy cover and benthic species richness on benthic cover stability. For the stability models, we further filtered the data to only include sites with seven or more years of layered data collection, which excluded the southern California sites (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S1). All sites included in the stability analyses were sampled during the 2014–2016 marine heatwaves (Gentemann et al., 2017).

Using the R package codyn (Hallett et al., 2016), we calculated community stability as the temporal mean divided by the temporal standard deviation of total percent cover summed across all benthic species (µ/ơ or ȳ/s; Tilman, 1999). As benthic stability is positive continuous data, we ran generalized mixed models using a Gamma distribution with a log link function (as with Gamma distribution variance is proportional to the square of the mean, and the log link function ensures that predicted values remain positive, making it suitable for modeling non-negative data; Dunn and Smyth, 2018). Models included the same random effect terms as above, but now compared the following predictors of benthic stability using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and AIC (Akaike, 1974; Schwarz, 1978): stability in rockweed canopy cover, the temporal mean of rockweed percent cover, and temporal mean of benthic species richness.

To identify rockweed-associated benthic species that might be impacted by loss in rockweed cover, we ran linear models regressing each rockweed species’ percent cover with each individual benthic species’ percent cover. The regressions were plotted for benthic species with significant relationships with rockweed percent cover, after Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing (adj p< 0.05). We tested differences in benthic community composition between plots with varying rockweed cover with a permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA; Anderson, 2017). The PERMANOVA was based on 999 random permutations constrained by site of an untransformed Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index, with the following predictors: Region (CA North, CA Central, & CA South), rockweed canopy percent cover, the interaction between rockweed percent cover and region. The SIMPER procedure was used to identify the contribution of different benthic taxa to the dissimilarities between plots with low and high rockweed cover. As SIMPER analyses compare the average abundances to examine the contribution of each species to the dissimilarity between groups, we classified each quadrat data point as having either ‘high’ or ‘low’ rockweed cover. If percent cover of rockweed canopy was within the first quartile (<25th percentile of total rockweed cover values for the species) then it was classified as ‘low’ cover, and if it was in the third quartile (>75th percentile) then it was classified as ‘high’ cover. The SIMPER analyses could then compare our two a priori groups, to assess which species contribute the most to benthic communities under ‘low’ and ‘high’ rockweed cover. We set a threshold of reporting species with an average contribution of >1%, to focus on benthic species which are driving community changes and how their percent cover differs between plots with ‘high’ vs. ‘low’ rockweed canopy cover (Clarke, 1993). We plotted the difference in average percent cover between the pre-defined ‘high’ and ‘low’ rockweed cover groups for species which had an average contribution of > 1% from the SIMPER analysis. We created Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) plots using the R package vegan (Oksanen et al., 2001) to visualize associations between dominant benthic species and rockweed canopy cover. We filtered benthic species (full list in Supplementary Materials Supplementary Table S2) to those having >5% mean percent cover under each rockweed species to concentrate on rockweed associated species, reduce noise in the Bray-Curtis distance calculations, and best visualize how this community is affected by changes in rockweed cover (Clarke and Green, 1988). For each rockweed species, we ran a NMDS on the percent cover matrix with metaMDS function, using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and ‘try’ value of 100.

Results

A high diversity of species was found in association with the three rockweed taxa. A total of 74 benthic taxa were recorded across all rockweed plots (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S2), and the total number of taxa varying between the three main rockweed assemblages, with 69, 48, and 39 taxa recorded for S. compressa, F. distichus, and P. limitata assemblages, respectively. Most benthic taxa had a mean percent cover lower than 10% (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S2). Certain benthic species had high distributional overlap with the rockweed taxa (i.e., similar presence/absence across sites), with S. compressa having high distributional overlap with Cyanoplax species, Phragmatopoma species, and Mazzaella affinis, F. distichus having high overlap with Mazzaella species, Microcladia borealis, and Pyropia species, and P. limitata having high overlap with Neorhodomela oregona, Cryptosiphonia woodii, and Mazzaella species (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Table S2). The ANOVA reported significant differences between rockweed assemblages in mean benthic species richness (F2,1542 = 104, p<0.05) and diversity (F2,1542 = 79, p<0.05); both were greater within F. distichus plots, followed by S. compressa, and P. limitata (Figure 1b, Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S3, Supplementary Table S3). Within the MARINe data, we found that F. distichus had a mean tidal height of 1.7m, S. compressa had a mean tidal height of 1.9m, and P. limitata had a mean tidal height of 2.2m. Pelvetiopsis limitata had significantly higher tidal height than F. distichus in the CA North region (F1,6521 = 2830, p<0.05), and there were significant differences in tidal height within the CA Central region, with mean heights decreasing from P. limitata, S. compressa, and F. distichus (F2,5928 = 336, p<0.05).

Broadly, the models show that rockweed canopy cover increases benthic cover, richness, and diversity, although this varies on the rockweed taxa and region, and much of the variance is explained by random site effects. We found a significant positive effect of rockweed cover on total understory percent cover (calculated as sum across all individual species % cover) for all three taxa (p<0.05; Table 1). There was also a significant interaction between percent cover of F. distichus and region, with F. distichus cover having a higher positive impact on understory cover within Northern California (Table 1). The models explained a moderate proportion of variance in benthic cover for each species (Marginal R2/Conditional R2: S. compressa = 0.303/0.803; F. distichus = 0.128/0.642; P. limitata = 0.095/0.552), indicating that random effects contribute substantially to the overall model fits. Percent rockweed cover had a significant effect on understory richness for S. compressa and P. limitata (p<0.05), but not for F. distichus (Table 2). Fucus distichus again showed a significant interaction between percent cover and region, with Northern California having higher richness under high F. distichus cover compared to Central California (Table 2). Pelvetiopsis limitata had the opposite relationship, with Central California regions having higher richness under high rockweed canopy cover (Table 2). The richness models also explained a moderate proportion of variance for each species (Marginal R2/Conditional R2: S. compressa = 0.112/0.475; F. distichus = 0.047/0.357; P. limitata = 0.145/0.469), thus random effects contribute substantially to the overall model fits. Silvetia compressa and F. distichus cover had a significant effect of percent cover on benthic diversity (Supplementary Table S4), although fixed effects only explained a small portion of the variance (Marginal R2/Conditional R2: S. compressa = 0.016/0.513; F. distichus = 0.019/0.419), meaning that random effect accounted for most of the models’ explanatory power.

Table 1

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. compressa (Df=757) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory cover ~ rockweed cover + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 0.20 | [0.15 – 0.26] | <0.001 |

| Rockweed cover | 0.90 | [0.88 – 0.92] | <0.001 |

| σ2 | 0.32 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.303/0.803 | ||

| F. distichus (Df=461) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory cover ~ rockweed cover * region + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 0.38 | [0.24 – 0.46] | 0.131 |

| RW cover | 0.73 | [0.60 – 0.83] | <0.001 |

| Region [CA North] | 0.39 | [0.19-0.63] | 0.386 |

| Rockweed cover × Region [CA North] | 0.32 | [0.52-0.81] | 0.031 |

| σ2 | 0.6 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.128/0.642 | ||

| P. limitata (Df=405) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory cover ~ rockweed cover + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 0.24 | [0.15 – 0.51] | <0.001 |

| RW cover | 0.83 | [0.76 – 0.87] | <0.001 |

| σ2 | 0.88 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.095/0.552 | ||

Testing the effect of percent rockweed canopy cover of each rockweed taxa on total benthic percent cover.

Results from generalized mixed-models are shown, with the estimates, Confidence Intervals (CI), and p-values for the fixed effects (Rockweed cover and Region), as well as the residual variance (σ2) and marginal and conditional R2 values.

Bolded values are those that are significant (p < 0.05).

Table 2

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. compressa (Df=757) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory richness ~ rockweed cover + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 6.65 | [6.01 – 7.29] | <0.001 |

| Rockweed cover | 3.56 | [2.63 – 4.49] | <0.001 |

| σ2 | 3.99 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.112/0.475 | ||

| F. distichus (Df=461) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory richness ~ rockweed cover * region + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 8.47 | [7.54 – 9.41] | <0.001 |

| Rockweed cover | -0.53 | [-2.57 – 1.51] | 0.611 |

| Region [CA North] | -1.85 | [-3.20 – -0.49] | 0.008 |

| Rockweed cover × Region [CA North] | 4.36 | [1.99 – 6.73] | <0.001 |

| σ2 | 4.19 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.047/0.357 | ||

| P. limitata (Df=405) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory richness ~ rockweed cover * region + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 6.81 | [5.44 – 8.18] | <0.001 |

| RW cover | 6.64 | [2.33 – 10.95] | 0.003 |

| Region [CA North] | -1.59 | [-3.28 – 0.11] | 0.066 |

| Rockweed cover × Region [CA North] | -5.58 | [-10.10 – -1.06] | 0.015 |

| σ2 | 3.57 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.145/0.469 | ||

Testing the effect of percent rockweed canopy cover of each rockweed taxa on total benthic species richness.

Results from generalized mixed-models are shown, with the estimates, Confidence Intervals (CI), and p-values for the fixed effects (Rockweed cover and Region), as well as the residual variance (σ2) and marginal and conditional R2 values.

Bolded values are those that are significant (p < 0.05).

We found that higher mean rockweed cover is correlated with higher benthic stability for S. compressa and P. limitata (Table 3) The best fitting model explaining stability in benthic cover for S. compressa included mean rockweed cover as a predictor, which was significant (Table 3), with a moderate portion of the variance explained by fixed effect (Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.221/0.710). Mean rockweed cover, stability of rockweed cover, and average benthic species richness all had no significant effect on benthic stability in F. distichus models (Table 3). The best fitting model for P. limitata also included mean rockweed cover (Table 3) as well as the interaction between rockweed and region, but a small portion of the variance was explained by the fixed effects (Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.071/0.792).

Table 3

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. compressa (Df=70) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory stability ~ Mean rockweed cover + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 5.37 | [4.01 – 7.19] | <0.001 |

| Mean rockweed cover | 3.71 | [2.14 – 6.43] | <0.001 |

| σ2 | 0.12 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.221/0.710 | ||

| F. distichus (Df=78) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory stability ~ Mean understory richness + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 5.66 | [3.77 – 8.49] | <0.001 |

| Mean SR | 1.02 | [0.99 – 1.05] | 0.276 |

| σ2 | 0.06 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.003/0.858 | ||

| P. limitata (Df=72) | |||

| best fitting model | Understory stability ~ Mean rockweed cover + (1 | site/quadrat) | ||

| (Intercept) | 4.83 | [3.48 – 6.72] | <0.001 |

| Mean rockweed cover | 2.7 | [2.70 – 6.53] | 0.028 |

| σ2 | 0.08 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.097/0.728 | ||

Testing the effect of average rockweed cover, stability of rockweed cover, and average understory species richness on the stability of total benthic cover.

Results from generalized mixed-models are shown, with the estimates, Confidence Intervals (CI), and p-values for the fixed effects (Rockweed cover and Region), as well as the residual variance (σ2) and marginal and conditional R2 values.

Bolded values are those that are significant (p < 0.05).

The significant (adj. p< 0.05) species-specific linear regressions identified positive relationships between benthic non-coralline crustose algae cover and S. compressa and P limitata rockweed canopy cover (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S4). All three rockweed species had negative relationships with Mytilus californianus and Chthamalus species (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S4). Many of the species relationships were unique to each rockweed canopy species (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S4). Further, we found mixed relationships between rockweeds, with a positive association between F. distichus and S. compressa but a negative relationship between P. limitata and S. compressa (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S4).

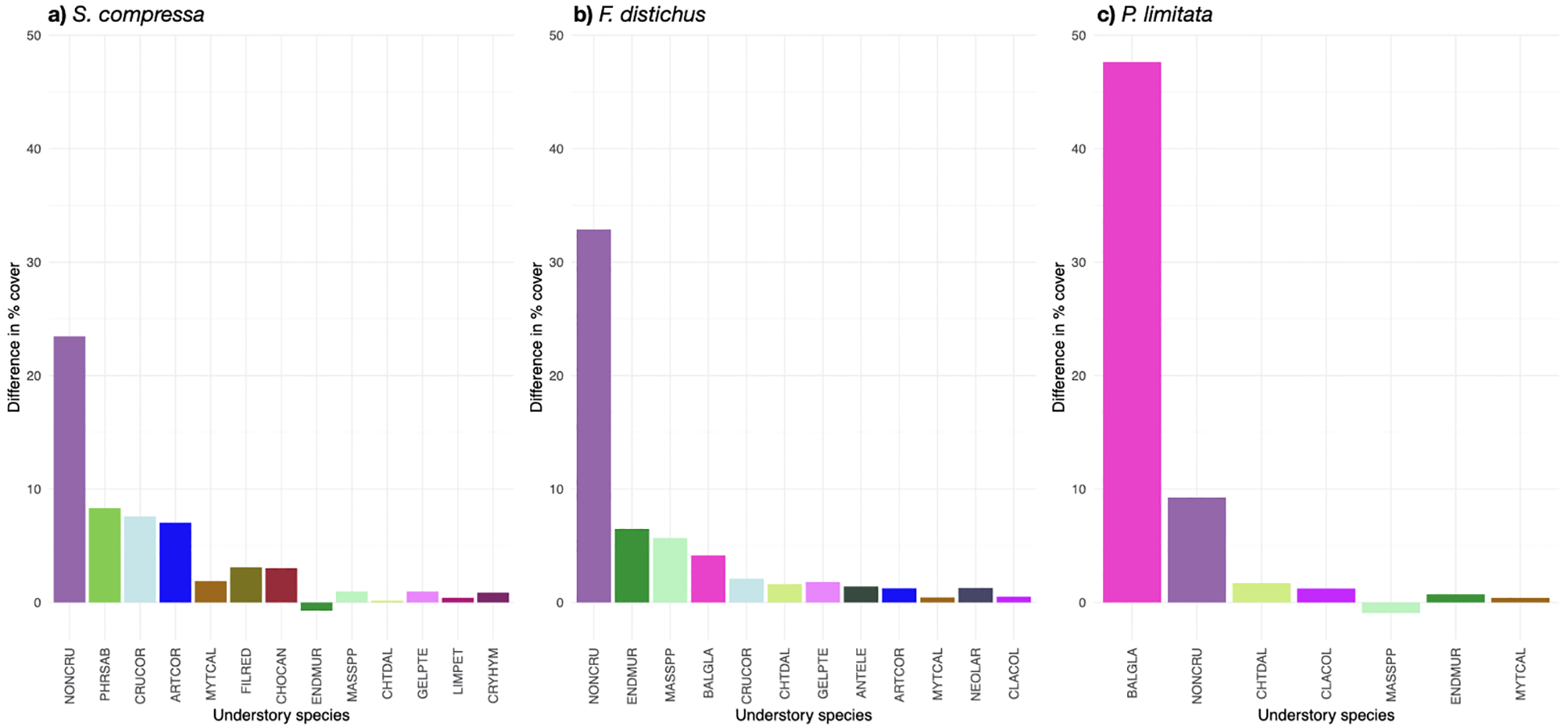

Rockweed cover had a significant effect on benthic community composition, mainly positively impacting non-coralline crusts and invertebrate cover. The PERMANOVA results suggest significant differences in benthic cover with changes in rockweed canopy cover and across regions for each rockweed taxa (Table 4). The SIMPER analyses indicated important species contributing to the differences in benthic communities between ‘high’ and ‘low’ rockweed canopy cover (Figure 2). Most species with SIMPER contributions to benthic community differences >1% had higher cover under ‘high’ rockweed cover (Figure 2). For each rockweed taxa, non-coralline crusts displayed higher cover under ‘high’ compared to ‘low’ rockweed cover. Other than non-coralline crusts, we found unique species contributing the most to benthic community differences between ‘high’ and ‘low’ rockweed cover across the three taxa (Figure 2).

Table 4

| Df | MS | R2 | F | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silvetia compressa | |||||

| Rockweed cover | 1 | 32.232 | 0.150 | 131.425 | 0.001 |

| Region | 1 | 5.888 | 0.027 | 24.006 | 0.001 |

| Rockweed cover X Region | 1 | 2.750 | 0.012 | 11.214 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 707 | 173.391 | 0.809 | ||

| Total | 710 | 214.260 | 1 | ||

| Fucus distichus | |||||

| Rockweed cover | 1 | 13.934 | 0.151 | 62.992 | 0.001 |

| Region | 1 | 3.166 | 0.034 | 14.314 | 0.001 |

| Rockweed cover X Region | 1 | 1.434 | 0.015 | 6.484 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 334 | 73.880 | 0.799 | ||

| Total | 337 | 92.414 | 1 | ||

| Pelvetiopsis limitata | |||||

| Rockweed cover | 1 | 18.919 | 0.181 | 86.548 | 0.001 |

| Region | 1 | 8.959 | 0.085 | 40.986 | 0.001 |

| Rockweed cover X Region | 1 | 1.918 | 0.018 | 8.776 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 343 | 74.976 | 0.716 | ||

| Total | 346 | 104.772 | 1 | ||

Summary of PERMANOVA results for benthic community assemblage differences between plots with varying percent cover of rockweed canopy, region, their interaction, with quadrat nested within site as random terms is shown for S. compressa, F. distichus and P. limitata.

The following outputs are shown for each PERMANOVA: Df (Degrees of Freedom), MS (Mean Sum of Squares), R2 (Coefficient of Determination), F (Pseudo-F Statistic), and Pr(>F) (P-value).

Bolded values are those that are significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 2

Bar plots displaying the difference in average percent cover for species driving community differences (>1% contribution from SIMPER analysis) between two a prior groups: ‘high’ (>75th percentile) vs. ‘low’ (<25th percentile) rockweed cover for S. compressa(a), F distichus(b), and P. limitata(c). See Supplementary Table S2 for species abbreviations.

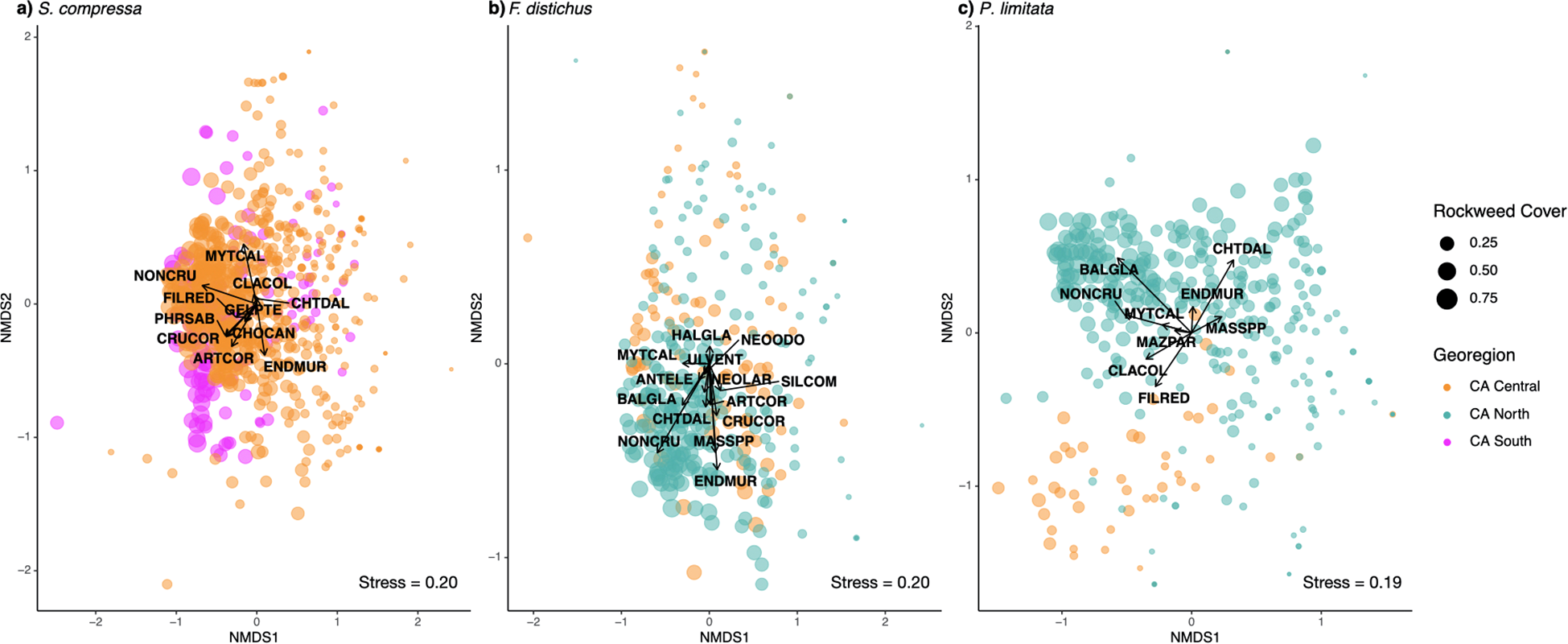

NMDS analyses suggest the composition of dominant benthic species is altered with a change in rockweed canopy cover (Figure 3). All three rockweed taxa showed higher percent cover of non-coralline crusts in plots/years with higher rockweed cover (Figure 3). Other benthic species associated with higher percent cover of S. compressa include filamentous red algae, Phragmatopoma species, and crustose and articulated corallines (Figure 3a). Species associated with higher cover of F. distichus include E. muricata, Mastocarpus species, Chthamalus species, Balanus glandula, and crustose and articulated corallines (Figure 3b). There was a more distinct separation in benthic assemblages by region for P. limitata compared to the other two rockweeds (Figure 3), with filamentous red algae and Cladophora columbiana being associated with high P. limitata cover in Central California and species such as Balanus glandula and Mytilus californianus being associated with high P. limitata cover in Northern California (Figure 3c).

Figure 3

NMDS plots show shifts in dominant community benthic assemblages (i.e., taxa with mean cover > 5% per rockweed) with varying degrees of rockweed canopy percent cover of S. compressa(a), F) distichus(b), and P. limitata(c). Each point is a quadrat per site, per time sampled, colored by region, and sized by rockweed percent cover. The arrows indicate the relationship and strength of each dominant benthic species with rockweed cover (see Supplementary Table S2 for species abbreviations).

Discussion

Understanding how foundation species shape community composition and stability is crucial to gain a better mechanistic understanding of climate change vulnerability and subsequent conservation management decisions. We found that broadly, rockweed cover is positively associated with total benthic cover, richness, and diversity, although these relationships vary among rockweed taxa and region. We also found that higher mean rockweed cover is more important in driving benthic stability than the stability of rockweed cover, although the positive impact of rockweed cover on benthic stability was only found for S. compressa and P. limitata (compared to F. distichus where mean understory species richness best explained stability, although this was not significant; p = 0.276). Thirdly, we found that non-coralline crust benthic cover is positively associated with canopy cover of all three rockweed species, alongside several other positive associations of benthic species unique to each rockweed taxa. Our findings provide support for conservation investment to restore rockweed species in California and highlight how conservation management of these foundation species should be targeted to specific regions and taxa to achieve the greatest biodiversity and coastal resilience benefits.

Rockweed cover influences benthic community richness, diversity, and cover

Higher benthic cover is associated with higher rockweed canopy cover for all three rockweed taxa, and higher benthic richness for S. compressa and P. limitata. Our work corroborates several studies highlighting the role of foundational macroalgae species in shaping rocky intertidal communities. For example, Schiel and Lilley (2007) found that species richness and community stability decreased following the loss of the New Zealand canopy-forming algae, Hormosira banksii. Within California, Fales and Smith (2022) found that richness and diversity were significantly higher when P. californica was present (compared to sites where it was removed). Several studies report community changes following the removal of canopy-forming macroalgae (Airoldi, 1998; Benedetti-Cecchi et al., 2001; Lilley and Schiel, 2006; Schiel and Lilley, 2011), yet our findings are novel in that they provide empirical evidence of rockweed dynamics altering community composition from naturally occurring long-term trends, including interannual variation over a decade across multiple sites. By providing a refuge from abiotic stresses as well as habitat complexity for understory species, rockweeds play a critical role in the resilience of rocky intertidal systems to anthropogenic and environmental threats (Eriksson et al., 2006; Lilley and Schiel, 2006). It is also likely that benthic community richness plays an important role in driving rockweed canopy cover, as Boyer et al. (2009) found that benthic richness increases macroalgal stability and productivity.

Our results suggest that both species and ecoregion are important to consider within rockweed conservation efforts. Rockweed cover has a greater impact on benthic cover and richness in Northern California for F. distichus, on richness within Central California for P. limitata, on all community metrics across regions equally for S. compressa, and region was significant in the PERMANOVA for all three rockweed species. Generally, wave exposure and tidal amplitude increase from south to north along California’s coast (Jay, 2009; O’Reilly et al., 2016), and while we lack these metadata for many of the survey sites, we can infer that differences in these habitat characteristics might be driving the influence of region on rockweed canopy-benthic community relationships. Other studies report similar effects of region/latitudes, finding that the loss of canopy-forming algae leads to declines in cover and stability of understory algae (Bulleri et al., 2012) and richness and abundance of motile invertebrates (Elsberry and Bracken, 2021), but only in the southernmost sites across Europe and North America, respectively. As rockweed cover provides a refuge from heat, irradiance, and water loss (Bertness et al., 1999; Bulleri et al., 2002; Lilley and Schiel, 2006), rockweed canopy likely has a larger impact on understory persistence at warmer equatorial sites.

Rockweed cover leads to higher stability of benthic cover in S. compressa and P. limitata communities

Rockweed cover has a positive effect on the stability of total percent cover of benthic species under S. compressa and P. limitata canopies. Compared to F. distichus, these two species typically occur at higher tidal zonations and S. compressa is more southernly distributed, thus they might play a greater role in ameliorating desiccation stress leading to their significant relationship with benthic stability. Silvetia compressa also does not contain the phenolic compounds found in F. distichus and P. limitata that deter grazer and epifaunal organisms (Brunyer et al., 2024), which might be why S. compressa has the strongest positive associations with benthic richness, cover, and stability of the three rockweed taxa. The physical attributes of rockweeds, including frond density and thickness, may increase microhabitat availability and allow more species to coexist (Bulleri et al., 2016; Kay et al., 2016a). Plant morphology is also controlled by wave intensity, with wave-swept organisms tending to be smaller in size (Blanchette, 1997) which might lead to rockweeds in the more wave-intense northern California region (O’Reilly et al., 2016) providing less canopy cover due to smaller frond lengths. Frond size and structure also influences the rate that rockweeds dislodge organisms via whiplash (Dayton, 1971), possibly driving the interspecific differences in rockweed effects on benthic community dynamics. Traits such as branch length, density, and circumference, as well as intraspecific genetic differences, can all influence the effect of rockweed canopy on benthic community assemblages (Kay et al., 2016a; Jormalainen et al., 2017).

Our findings suggest that rockweed cover has less impact on benthic community diversity compared to benthic cover and richness (shown by the smaller Marginal R2 values of the diversity models). Similar to our findings, Sapper (1999), found that the benthic assemblages of S. compressa within southern California have low diversity but high richness in seaweed and macroinvertebrate species. Other studies report a positive relationship between rockweed canopies and benthic diversity which is dependent on habitat/physical variables, such as only within high and mid-intertidal zones (Watt and Scrosati, 2013), or only within boulder patches (Maggi et al., 2012). We found that while benthic richness was increased under S. compressa and P. limitata, the species associations of these two rockweeds were largely unique and dominated by a few species, similar to Kimbro and Grosholz (2006) finding that the presence of rockweeds disproportionately increases the abundance of a few common species. Rockweeds provide habitat with low light penetration and high whiplash, which can have a positive influence on algal species that prefer these conditions, and negative impacts on other benthic algae (Maggi et al., 2012). For example, Westerbom and Koivisto (2022) found that Fucus species had a negative effect on filamentous algae, owing to the whiplash from rockweeds decreasing establishment of other algal species, whereas Kim (2002) found that the shading effect of F. distichus reduced the biomass of the turf red alga Mazzaellla parksii.

Impact of rockweed canopy cover on associated benthic species

Our investigations of species-specific relationships show turf algae (Endocladia and Mazzaella species), non-coralline crusts, and the acorn barnacle Chthamalus spp, having relatively high percent cover under all rockweed taxa, otherwise each rockweed has uniquely associated benthic species. These positive associations with benthic species cover are unlikely to be driven by distributional overlaps (shown by Jaccard similarities in species presences; Supplementary Table S2), with for example, limpets having relatively similar presence/absence as non-coralline crusts, but non-coralline crusts having much higher average percent cover under rockweed canopy. Our analyses are limited using percent cover as a proxy for species abundances, with the upper limit of variance being constrained at 100%. However, several studies show that percent cover correlates with biomass (Donohue et al., 2013; Mrowicki et al., 2016; White et al., 2020) and that percent cover and biomass of dominant species are associated with community stability across a range of ecosystems (Valencia et al., 2020). Thus, percent cover is a suitable proxy for the abundance of sessile species and is informative of ecological interactions such as competition for space or responses to disturbance within the rocky shore (Stachowicz et al., 2008; Valdivia et al., 2021). Our percent cover data are also focused on sessile species, yet other studies have shown that higher rockweed canopy cover is associated with high diversity and/or abundance of motile invertebrates (Sapper and Murray, 2003; Kay et al., 2016b; Umanzor et al., 2017; Elsberry and Bracken, 2021; Fales and Smith, 2022).

Our results show a positive relationship between percent cover of all three rockweed taxa and non-coralline crustose algae, possibly due to rockweeds creating an environment where crusts can outcompete foliose algae (Airoldi, 2000). Several studies suggest that the low light intensity and protection against desiccation that rockweed canopies provide allow encrusting and corticated red algae to proliferate (Jenkins et al., 1999; Connell, 2005; Irving and Connell, 2006; Álvarez-Losada et al., 2020). Alternatively, the loss of rockweed canopies is associated with an increase in ephemeral and epiphytic algal turfs (Connell et al., 2014; Fernández, 2016). Similarly, Fales and Smith (2022) found that plots with high Pevletiopsis californica cover had significantly more total seaweed cover, especially the brown encrusting alga Pseudolithoderma. Crustose and articulated coralline algae have previously been found in association with S. compressa (Sapper, 1999) which is likely due to these brown encrusting algal species being able to withstand the high abundance of grazers, low light penetration, and high whiplash associated with rockweed canopies (Hawkins and Hartnoll, 1980; Kiirikki, 1996; Raffaelli and Hawkins, 1996). Non-coralline crusts play an important ecological role within the rocky intertidal zone, as they represent a critical life history stage for algae with heteromorphic generations (Lubchenco and Cubit, 1980; John, 1994). While the crustose life stage is thought to be more resilient to disturbance compared to erect phases, growth at this stage is slow (Dethier, 1994). Thus, having rockweed canopies to eliminate other algal forms might be critical to the growth and survival of encrusting algal phases (Anderson et al., 2008), and site-level population viability of these algal species. Crustose and cespitose algal species can have a positive biodiversity impact as they themselves form complex habitats which aid attachment of other species to the substrate (Dijkstra et al., 2017). For example, non-coralline crusts are important for recruitment of sessile invertebrate species (Paull, 1998), such as Hildenbrandia dawsonii inducing the larval settlement of abalone (O’Leary et al., 2017). By supporting a limiting life stage of these algal species which also disproportionately support other species, the benefits of rockweeds maintaining biodiversity and resilience are compounded.

Rockweed cover also has a positive association with benthic sessile invertebrate abundances. We found that barnacle species often had higher percent cover in plots/years with higher mean rockweed cover, especially Balanus within P. limitata plots. Previous work suggests that Balanus barnacles help facilitate P. limitata recruitment (Farrell, 1991; Worden, 2015). Chthamalus barnacles were shown to have no effect on Pelvetiopsis recruitment (Farrell, 1991), and Fales and Smith (2022) found that plots lacking P. californica had higher cover of Chthamalus. Sapper and Murray (2003) report that barnacle abundances were reduced beneath S. compressa canopy, which the authors attribute to the whiplash of the rockweed fronds dislodging newly settled barnacle larvae. Our results also suggest positive impacts of rockweed cover on abundances of Phragmatopoma species (Figure 3), which has been previously noted for S. compressa (Sapper and Murray, 2003). Mussels displayed higher average cover in plots with high rockweed cover (Figure 3) for all three rockweed taxa. Sapper and Murray (2003) found that M. californianus was one of the dominant understory species of S. compressa within southern California, and a Californian restoration project (Raimondi et al., 2016), reported M. californianus disproportionately recruiting under fucoid algae. Mussels are another important foundation species, as high mussel cover is associated with higher stability within Californian rocky shore communities, particularly in southern California where mussel abundances have seen the largest declines over the past few decades (Miner et al., 2021). Future investigations into the relationship between trends and interactions of Fucoids and mussels within California could lead to important conservation insights of these intertidal foundation species.

Conservation implications for rockweed restoration

A better understanding of the foundational role that rockweeds play in maintaining community stability and biodiversity and how those relationships vary by species, region, and tidal zone is needed to help direct conservation, restoration, and research actions. Our results suggest that restoration efforts should be spatially tailored to each species, prioritizing Northern California for F. distichus, Central California for P. limitata, and the entire California distribution for S. compressa. In addition to ecoregion, considerations of tidal zonation are also important as rockweed restoration efforts continue. High shore communities are generally less diverse due to the harsh environmental conditions (potentially why F. distichus benthic communities show higher diversity compared to the other two rockweeds; Denny and Gaines, 2007) and having canopy cover provided by rockweeds not only allows for more species to exist within this zone, but also for the persistence of species that are locally adapted to the upper intertidal habitat. We also found that benthic cover of S. compressa had a negative relationship with P. limitata canopy cover (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that restoring a single rockweed species may not benefit other rockweed taxa, possibly due to separate tidal niches. While we found evidence of different tidal niches between the three species, it is important to consider how microhabitat factors such as aspect, wave exposure, and coastal armoring may lead to fine-scale variation of intertidal zonation of rockweeds (Cacabelos et al., 2010). The impact of rockweed cover is likely heightened within the upper intertidal where its stress-ameliorating role is stronger (Roberts and Bracken, 2021), as well as in sites that experience stronger wind events, less wave action, and higher tidal amplitude. Yet, rockweed canopies might play an equally important stress-ameliorating role in wave-swept shores that experience less overall heat and desiccation stress, as these sites might be more vulnerable to these stressors during climate anomalies such as marine heatwaves (Buckley and Kingsolver, 2021). The importance of rockweed canopies in buffering heat/UV stress will also be dependent on the abundance functionally equivalent species. For example, Elsberry and Bracken (2021) found that the loss of Pelvetiopsis spp. and S. compressa led to a decline in motile invertebrates in southern California, but not in northern and central California sites where alternative algal taxa (i.e., Mastocarpus, Mazzaella, Corallina, and Endocladia) co-exist with rockweeds and buffer the system against their loss. We found that P. limitata and S. compressa had higher influence on benthic stability than F. distichus, potentially owed to these species typically inhabiting higher tidal zonations and having more southernly distributions. As such, conservation efforts that aim to enhance benthic stability via the restoration of rockweed taxa should prioritize areas where rockweeds are the dominant high-shore species with low functional redundancy. Furthermore, Readdie (2004) found significant shifts in the upper limits of S. compressa from 1992-2002, attributed to ecological succession, and Kaplanis et al. (2024) report S. compressa having a significant negative relationship with lunar declination (the fluctuation in tidal exposure on ~19 year cycle), highlighting how the natural variation in the rocky intertidal should be considered within restoration efforts.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that rockweeds are foundational to the rocky intertidal communities, increasing benthic cover, richness, and stability, as well as the abundance of non-coralline crusts and other associated species. This foundational role varies per species and region with stronger foundational roles demonstrated by species found in more stressful environments of higher intertidal and southerly regions. Our results show that efforts to restore rockweed species will have disproportionately high benefits to maintaining species richness and community stability. Our study shows that rockweed cover plays a strong role in increasing benthic richness and stability in southern California sites. This knowledge could be valuable in prioritizing sites in southern California for restoration. Southern California also has the largest declines in S. compressa, driven by the desiccation stress of Santa Ana Winds (Whitaker et al., 2024), further warranting the need for restoration in this region. It was also shown that desiccation caused brittle thalli in F. distichus, decreasing the wave force needed to dislodge algae during the spring and summer months when low tides fall during midday (Haring et al., 2002), highlighting the potential of including treatments to increase the desiccation resilience in restoration efforts to improve the longevity of outplanted populations (Jueterbock et al., 2021). Sea level rise is also predicted to impact rockweeds with anticipated increases in adult mortality as availability of suitable habitat lessens (Skene, 2009). As several studies suggest shifts in benthic community assemblages are primarily affected by climate-mediated loss of rockweed canopy rather than direct impacts of climate change (Álvarez-Losada et al., 2020; Truong et al., 2024), it is imperative that restoration efforts focus on reinforcing rockweed cover in these systems to have knock-on benefits to understory communities.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://marine.ucsc.edu/explore-the-data/contact/index.htmlhttps://github.com/esnielsen/Rockweed_community_ecology.

Author contributions

EN: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization. WH: Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. PR: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MR: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors would like to thank the LaFetra Foundation, Jack and Laura Dangermond Conservation Foundation, and Zegar Family Foundation for their philanthropic financial support for the LaFetra Fellowship, Point Conception Institute, and The Nature Conservancy’s research on coastal conservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge those involved in data collection and management within the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), as well as those that fund MARINe (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans, National Parks Service, California Ocean Protection Council). We would like to acknowledge the UC Natural Reserve System, California State Parks, Cabrillo National Monument, Hopkins Marine Station, Greater Farallones and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuaries, The Nature Conservancy, and Vandenberg Space Force Base for access to field sites for MARINe data collection. The authors acknowledge the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve (https://doi.org/10.25497/D7159W), the Point Conception Institute, LaFetra Foundation, and the Nature Conservancy for their support of this research. We thank Melissa Miner for comments on early drafts of the manuscript and help with data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1699335/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abbott I. A. Isabella A. Hollenberg G. J. (1992). Marine algae of california (Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press).

2

Agardh C. A. (1824). Systema algarum (Lund, Sweden: Literis Berlingianis).

3

Airoldi L. (1998). Roles of disturbance, sediment stress, and substratum retention on spatial dominance in algal turf. Ecology79, 2759–2770. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2759:RODSSA]2.0.CO;2

4

Airoldi L. (2000). Effects of disturbance, life histories, and overgrowth on coexistence of algal crusts and turfs. Ecology81, 798–814. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0798:EODLHA]2.0.CO;2

5

Akaike H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automatic Control19, 716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

6

Altieri A. H. Witman J. D. (2006). Local extinction of a foundation species in a hypoxic estuary: Integrating individuals to ecosystem. Ecology87, 717–730. doi: 10.1890/05-0226

7

Álvarez-Losada Ó. Arrontes J. Martínez B. Fernández C. Viejo R. M. (2020). A regime shift in intertidal assemblages triggered by loss of algal canopies: A multidecadal survey. Mar. Environ. Res.160, 104981. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.104981

8

Anderson M. J. (2017). “ Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA),” in Wiley statsRef: statistics reference online, 1st ed.n. Ed. KenettR. S. (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley), 1–15.

9

Anderson R. J. Anderson D. R. Anderson J. S. (2008). Survival of sand-burial by seaweeds with crustose bases or life-history stages structures the biotic community on an intertidal rocky shore. Bot. Mar.51, 10–20. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2008.006

10

Angelini C. Altieri A. H. Silliman B. R. Bertness M. D. (2011). Interactions among foundation species and their consequences for community organization, biodiversity, and onservation. BioScience61, 782–789. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.10.8

11

Beermann A. J. Ellrich J. A. Molis M. Scrosati R. A. (2013). Effects of seaweed canopies and adult barnacles on barnacle recruitment: The interplay of positive and negative influences. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.448, 162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.07.001

12

Benedetti-Cecchi L. Pannacciulli F. Bulleri F. Moschella P. Airoldi L. Relini G. et al . (2001). Predicting the consequences of anthropogenic disturbance: large-scale effects of loss of canopy algae on rocky shores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.214, 137–150. doi: 10.3354/meps214137

13

Bertness M. D. Leonard G. H. Levine J. M. Schmidt P. R. Ingraham A. O. (1999). Testing the relative contribution of positive and negative interactions in rocky intertidal communities. Ecology80, 2711–2726. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[2711:TTRCOP]2.0.CO;2

14

Bianchelli S. Fraschetti S. Martini F. Lo Martire M. Nepote E. Ippoliti D. et al . (2023). Macroalgal forest restoration: the effect of the foundation species. Front. Mar. Sci.10, 1213184. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1213184

15

Bittick S. J. Clausing R. J. Fong C. R. Scoma S. R. Fong P. (2019). A Rapidly Expanding macroalga acts as a foundational species providing trophic support and habitat in the South Pacific. Ecosystems22, 165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10021-018-0261-1

16

Blanchette C. A. (1997). Size and survival of intertidal plants in response to wave action: A case study with Fucus gardneri. Ecology78, 1563–1578. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1563:SASOIP]2.0.CO;2

17

Blanchette C. A. Melissa Miner C. Raimondi P. T. Lohse D. Heady K. E. K. Broitman B. R. (2008). Biogeographical patterns of rocky intertidal communities along the Pacific coast of North America. J. Biogeogr.35, 1593–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01913.x

18

Bordeyne F. Migné A. Davoult D. (2015). Metabolic activity of intertidal Fucus spp. communities: evidence for high aerial carbon fluxes displaying seasonal variability. Mar. Biol.162, 2119–2129. doi: 10.1007/s00227-015-2741-6

19

Boyer K. E. Kertesz J. S. Bruno J. F. (2009). Biodiversity effects on productivity and stability of marine macroalgal communities: the role of environmental context. Oikos118, 1062–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17252.x

20

Brawley S. H. Johnson L. E. (1991). Survival of Fucoid embryos in the intertidal zone depends upon developmental stage and microhabitat. J. Phycol.27, 179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1991.00179.x

21

Brooks M. ,. E. Kristensen K. Benthem K. ,. J. van Magnusson A. Berg C.W. Nielsen A. et al . (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J.9, 378. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066

22

Brunyer M. Pfitzmann S. Scudder M. Wahba K. (2024). The effect of wave action and rockweed host species on intertidal epifaunal distribution, Vol. 8Ed WongK. (Santa Barbara, California).

23

Buckley L. B. Kingsolver J. G. (2021). Evolution of thermal sensitivity in changing and variable climates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.52, 563–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011521-102856

24

Buck-Wiese H. Andskog M. A. Nguyen N. P. Bligh M. Asmala E. Vidal-Melgosa S. et al . (2023). Fucoid brown algae inject fucoidan carbon into the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.120, e2210561119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210561119

25

Bulleri F. Benedetti-Cecchi L. Acunto S. Cinelli F. Hawkins S. J. (2002). The influence of canopy algae on vertical patterns of distribution of low-shore assemblages on rocky coasts in the northwest Mediterranean. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.267, 89–106. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00361-6

26

Bulleri F. Benedetti-Cecchi L. Cusson M. Maggi E. Arenas F. Aspden R. et al . (2012). Temporal stability of European rocky shore assemblages: variation across a latitudinal gradient and the role of habitat-formers. Oikos121, 1801–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19967.x

27

Bulleri F. Bruno J. F. Silliman B. R. Stachowicz J. J. (2016). Facilitation and the niche: implications for coexistence, range shifts and ecosystem functioning. Funct. Ecol.30, 70–78. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12528

28

Bustamante M. Tajadura J. Díez I. Saiz-Salinas J. I. (2017). The potential role of habitat-forming seaweeds in modeling benthic ecosystem properties. J. Sea. Res.130, 123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2017.02.004

29

Cacabelos E. Olabarria C. Incera M. Troncoso J. S. (2010). Effects of habitat structure and tidal height on epifaunal assemblages associated with macroalgae. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.89, 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.05.012

30

Cameron N. M. Scrosati R. A. Valdivia N. (2024). Structural and functional properties of foundation species (mussels vs. seaweeds) predict functional aspects of the associated communities. Com. Ecol.25, 65–74. doi: 10.1007/s42974-023-00171-5

31

Campbell V. Murphy G. Romanuk T. N. (2011). Experimental design and the outcome and interpretation of diversity–stability relations. Oikos120, 399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.18768.x

32

Canion C. Heck K. (2009). Effect of habitat complexity on predation success: re-evaluating the current paradigm in seagrass beds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.393, 37–46. doi: 10.3354/meps08272

33

Carr M. H. (1994). Effects of macroalgal dynamics on recruitment of a temperate reef fish. Ecology75, 1320–1333. doi: 10.2307/1937457

34

Cebrian E. Tamburello L. Verdura J. Guarnieri G. Medrano A. Linares C. et al . (2021). A roadmap for the restoration of Mediterranean macroalgal forests. Front. Mar. Sci.8, 709219. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.709219

35

Chung N. C. Miasojedow B. Startek M. Gambin A. (2019). Jaccard/Tanimoto similarity test and estimation methods for biological presence-absence data. BMC Bioinf.20, 644. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3118-5

36

Clarke K. R. (1993). Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol.18, 117–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x

37

Clarke K. R. Green R. H. (1988). Statistical design and analysis for a “biological effects. study. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.46, 213–226. doi: 10.3354/meps046213

38

Connell S. (2005). Assembly and maintenance of subtidal habitat heterogeneity: synergistic effects of light penetration and sedimentation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.289, 53–61. doi: 10.3354/meps289053

39

Connell S. Foster M. Airoldi L. (2014). What are algal turfs? Towards better description turfs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.495, 299–307. doi: 10.3354/meps10513

40

Crowe T. P. Cusson M. Bulleri F. Davoult D. Arenas F. Aspden R. et al . (2013). Large-scale variation in combined impacts of canopy loss and disturbance on community structure and ecosystem functioning (M O’Connor, Ed.). PloS One8, e66238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066238

41

Cusson M. Crowe T. P. Araújo R. Arenas F. Aspden R. Bulleri F. et al . (2015). Relationships between biodiversity and the stability of marine ecosystems: Comparisons at a European scale using meta-analysis. J. Sea Res.98, 5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2014.08.004

42

Dayton P. K. (1971). Competition, disturbance, and community organization: The provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky intertidal community. Ecol. Monogr.41, 351–389. doi: 10.2307/1948498

43

Dayton P. K. (1972). “ Toward an understanding of community resilience and the potential effects of enrichments to the benthos at McMurdo Sound, Antarctica,” in Proceedings of the colloquium on conservation problems in Antarctica, (Lawrence, Kansas), 81–96.

44

Dayton P. K. (1975). Experimental evaluation of ecological dominance in a rocky intertidal algal community. Ecol. Monogr.45, 137–159. doi: 10.2307/1942404

45

Denny M. W. Gaines S. (2007). Encyclopedia of tidepools and rocky shores (Berkeley California: University of california press).

46

Dethier M. N. (1994). The ecology of intertidal algal crusts: variation within a functional group. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.177, 37–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(94)90143-0

47

Dijkstra J. A. Harris L. G. Mello K. Litterer A. Wells C. Ware C. (2017). Invasive seaweeds transform habitat structure and increase biodiversity of associated species (AR Hughes, Ed.). J. Ecol.105, 1668–1678. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12775

48

Di Lorenzo E. Mantua N. (2016). Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change6, 1042–1047. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3082

49

Donohue I. Petchey O. L. Montoya J. M. Jackson A. L. McNally L. Viana M. et al . (2013). On the dimensionality of ecological stability. Ecol. Lett.16, 421–429. doi: 10.1111/ele.12086

50

Driskell W. B. Ruesink J. L. Lees D. C. Houghton J. P. Lindstrom S. C. (2001). Long-term signal of disturbance: Fucus gardneri after the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Ecol. Appl.11, 815–827. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2001)011[0815:LTSODF]2.0.CO;2

51

Duarte C. M. Gattuso J. Hancke K. Gundersen H. Filbee-Dexter K. Pedersen M. F. et al . (2022). Global estimates of the extent and production of macroalgal forests. Global Ecol. Biogeogr.31, 1422–1439. doi: 10.1111/geb.13515

52

Dunn P. K. Smyth G. K. (2018). “ Chapter 11: Positive continuous Data: Gamma and nverse Gaussian GLMs,” in Generalized linear models with examples in R. Eds. DunnP. K.Smyth (New York, New York: Springer), 425–456.

53

Elsberry L. A. Bracken M. E. S. (2021). Functional redundancy buffers mobile invertebrates against the loss of foundation species on rocky shores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.673, 43–54. doi: 10.3354/meps13795

54

Eriksson B. K. Rubach A. Hillebrand H. (2006). Biotic habitat complexity controls species diversity and nutrient effects on net biomass production. Ecology87, 246–254. doi: 10.1890/05-0090

55