Abstract

Coastal “blue carbon” ecosystems are increasingly targeted for carbon finance, yet persistent gaps in market integrity, governance, and long-term stewardship limit their contribution to climate goals. This review examines how ecosystem-based adaptive management (EAM) can be used as an operational bridge between blue-carbon ecology and carbon trading mechanisms, with a particular focus on China’s emerging market. We synthesize international standards and methodologies, analyse governance archetypes from Kenya, Australia, the United States, and Japan, and review recent Chinese methodologies and pilot projects across mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows. On this basis, we map core EAM functions—iterative planning, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment—onto key carbon-market integrity requirements (additionality, permanence, Monitoring–Reporting–Verification, and leakage control) and onto investor needs such as risk assessment, buffers, and co-benefit recognition. The analysis identifies common integrity challenges for blue-carbon crediting, ecosystem-specific financial and technical constraints, and a set of transferable remedies, including digital and stratified monitoring, dynamic buffers and insurance, and participatory safeguards and benefit-sharing. Building on these insights, we develop a finance-aware integration framework and an operational roadmap for China that links adaptive indicators and thresholds to methodology design, verification cadence, issuance logic, buffer management, registry transparency, and performance-linked financing. The framework clarifies how embedding EAM in blue-carbon standards and trading architecture can reduce uncertainty, raise credit quality, and support premium pricing while sustaining ecological performance and delivering coastal protection, biodiversity, and livelihood co-benefits under China’s “30·60” climate targets.

1 Introduction

The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (2019a) concludes that oceans and coasts are already being significantly affected by sea-level rise, ocean warming, marine heatwaves, changing storm regimes, and increasing extremes. At the same time, many coastal zones face intense anthropogenic pressures, including land reclamation and hard shoreline protection, aquaculture and agricultural expansion, pollution and eutrophication, and unsustainable resource extraction. Within these settings, “blue carbon” ecosystems—mangroves, tidal marshes, and seagrass meadows—are recognized for their high rates of carbon sequestration and long-term storage (Meng et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023; Bertram et al., 2021; Alongi, 2020), as well as for providing shoreline stabilization (Duarte et al., 2013; IPCC, 2019a; Zhu and Yan, 2022), nursery habitat for fisheries (Mcleod et al., 2011; Duarte et al., 2013), and buffers against climate-related disturbances (IPCC, 2019a; Seddon et al., 2020). Yet the same climatic and anthropogenic drivers that motivate policy interest in blue carbon also threaten ecosystem extent and condition, and thus the stability of the carbon they store.

For blue carbon initiatives seeking to access carbon markets, these coupled pressures translate into specific challenges for market integrity and financeability. Sea-level rise, subsidence, and changing storm regimes increase the probability of erosion, dieback, and other forms of carbon-stock reversal, raising questions about permanence (Kirwan and Megonigal, 2013; Schuerch et al., 2018; Syvitski et al., 2009; Wahl et al., 2015; Seneviratne et al., 2023; IPCC, 2019a). Coastal squeeze from reclamation and hard infrastructure destabilizes baselines and project boundaries (Pontee, 2013; Spencer et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2025). Technically demanding Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV)—requiring detailed habitat mapping, sediment coring, bulk-density and carbon-fraction analysis, and long-term monitoring—elevates per-ton costs, particularly for subtidal seagrass meadows and sediment-focused marsh projects (Howard et al., 2014; Macreadie et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024). In many jurisdictions, including China, unclear tenure, overlapping mandates, and fragmented trading architecture complicate carbon-rights attribution, slow permitting, and weaken the business case for long-duration stewardship (Li and Miao, 2022; Xu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). These financial and technical constraints make it difficult to satisfy core carbon-market requirements—additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control—at scale, even as compliance and voluntary schemes show growing interest in coastal ecosystems.

Ecosystem-based adaptive management (EAM) offers a promising way to address these intertwined ecological, institutional, and financial risks. Building on the adaptive management literature (Holling, 1978; Walters, 1986; Williams et al., 2009, 2014) and work on ecosystem-based management and nature-based solutions (Norberg and Cumming, 2008; Seddon et al., 2020; Vanderklift et al., 2022), EAM treats management interventions as iterative experiments. It emphasizes explicit objectives, monitoring of key ecological and social indicators, stakeholder participation, and feedback rules to adjust actions under uncertainty. Applied to blue carbon ecosystems, EAM can, in principle, translate climate and anthropogenic pressures into adaptive indicators, thresholds, and corrective measures that directly underpin additionality tests (e.g., counterfactual land- or sea-use trajectories), permanence management (e.g., reversal-risk triggers and buffers), MRV design (e.g., stratified sampling and digital tools), and leakage control (e.g., monitoring of displaced activities) (Herr et al., 2015; Emmer et al., 2015; Simpson and Smart, 2024; ORRAA and CI, 2022). Internationally, emerging standards and schemes—such as Verra’s VM0033 Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration, Australia’s tidal restoration method under the Emissions Reduction Fund, the Andalusian Blue Carbon Standard, and Japan’s J-Blue Credit system—demonstrate that blue carbon can be integrated into both voluntary and compliance markets (Verra, 2023; Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022a; Regional Government of Andalusia, 2023; Kuwae et al., 2022a; JBE, 2025). However, most of this work has not explicitly framed EAM as the operational interface between blue carbon governance, carbon-credit accreditation, and financing or rating practices.

This paper aims to fill that gap by treating EAM as the linking mechanism between blue carbon ecosystem management and carbon trading mechanisms, with a particular focus on China’s emerging blue carbon market. Specifically, we argue that linking EAM and carbon trading can (i) reduce key integrity risks in blue carbon projects by aligning iterative, evidence-based management with core carbon-market requirements, and (ii) provide a practical pathway for China to mobilize sustained finance for coastal restoration while strengthening long-term stewardship of mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrasses. To operationalize this argument, we ask three questions: (1) how EAM functions—iterative planning, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment—can be mapped onto key integrity dimensions in blue carbon markets (additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control); (2) which governance, MRV, and financing innovations from international blue carbon practice (e.g., digital MRV, dynamic buffers and insurance, co-benefit labeling and stacking, jurisdictional nesting) are most relevant to China’s evolving methodologies and trading architecture; and (3) what an actionable, finance-aware roadmap looks like for scaling high-integrity, adaptively managed blue carbon projects in China.

Our contribution is threefold. First, we provide a cross-context synthesis of how EAM has been, or could be, coupled with blue carbon crediting and finance across community-based projects, regional pilots, and national schemes in countries such as Kenya, Australia, the United States, Japan, and China. Rather than offering generic project descriptions, we analyze these case studies through a common EAM–market lens, identifying where adaptive indicators, decision rules, and governance arrangements already support market integrity and co-benefit delivery. Second, we propose a conceptual framework that explicitly links EAM indicators and decision rules to accreditation processes (under leading standards such as VM0033 and ACCU methods), credit issuance profiles, permanence and leakage management, and investor or rating-agency decision-making. Third, we derive a China-focused operational roadmap that aligns methodologies, registry and verification processes, and benefit-sharing arrangements with EAM principles, consolidating fragmented discussions of policy, technical constraints, and pilot projects into a coherent sequence from global lessons to Chinese application. The remainder of the paper introduces the theoretical basis of EAM, then reviews blue carbon trading and market-integrity challenges and existing standards, analyzes international and Chinese cases through the EAM–market lens, and finally develops the integration framework and roadmap for embedding EAM in China’s blue carbon governance.

2 Theoretical basis of EAM

The concept of adaptive management emerged in the late 1970s as a response to the complexity and uncertainty inherent in ecological systems. Holling (1978) introduced the idea of adaptive environmental assessment and management, emphasizing that management should be treated as an experimental process in which policies are continually tested, monitored, and adjusted in response to system feedbacks. Building on this foundation, Walters (1986) developed a more structured framework in Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources, defining adaptive management as “a structured process of learning by doing,” where scientific hypotheses are explicitly tested through management interventions and revised according to observed outcomes.

Subsequent scholars have further clarified the theoretical characteristics of adaptive management. Lee (1999) described adaptive management as a process of “learning while doing,” which is particularly suited to situations where ecological and social systems are highly complex and uncertain. Williams et al. (2009, 2014), in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Adaptive Management Guide, identified essential components of the approach, including setting clear objectives, developing predictive models, implementing management actions, monitoring outcomes, and using the results to adjust future decisions. Building on these foundations, Armitage et al. (2009) introduced the concept of adaptive co-management, which integrates the iterative learning of adaptive management with the collaborative features of participatory governance. This approach is particularly suited to contexts of social–ecological complexity, where multiple stakeholders and objectives must be reconciled. Similarly, Norberg and Cumming (2008) emphasized that adaptive management provides institutional flexibility to address uncertainty, and that achieving sustainability requires integrating ecological, economic, and social perspectives within governance frameworks.

Applying this approach to blue carbon ecosystems is particularly relevant given their exposure to climate-related stressors. Friess et al. (2019) highlighted that mangrove forests, for instance, face pressures from sea-level rise, storms, and anthropogenic disturbances, and their long-term sustainability depends on adaptive management strategies that enhance ecosystem resilience. By incorporating adaptive feedbacks and multi-level governance, EAM provides a pathway to maintaining the carbon sequestration capacity of mangroves, tidal marshes, and seagrasses under changing environmental conditions.

3 Blue carbon trading and market integrity challenges

3.1 Positioning blue carbon within compliance and voluntary markets

Carbon trading has evolved along two main pathways: compliance (mandatory) markets and voluntary markets. Compliance schemes—such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and national or subnational cap-and-trade programs—operate under legally binding caps on emissions, allocate or auction allowances, and allow entities to trade units so that mitigation occurs where it is most cost-effective (Ellerman et al., 2010; World Bank, 2019).

In parallel, voluntary carbon markets have expanded rapidly since the early 2000s. Standards such as Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), Gold Standard, and the American Carbon Registry (ACR) provide methodologies for nature-based solutions and community-scale projects outside compliance schemes, driven largely by corporate net-zero commitments and investor demand for high-quality offsets (Peters-Stanley and Yin, 2013; World Bank, 2019). Credit prices in voluntary systems are determined by project quality, transparency, and verified co-benefits rather than statutory limits.

Within this architecture, blue carbon ecosystems are not a separate market category, but a subset of land-use and land-use change activities that can be credited where methodologies exist and integrity criteria are met. The key question for this review is therefore not whether carbon markets exist, but how well existing compliance and voluntary mechanisms can accommodate the specific ecological, governance, and MRV features of blue carbon, and what this implies for the role of EAM. A concise comparison of key structural and functional differences between compliance and voluntary markets, together with blue-carbon-specific insights for each aspect, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Aspect | Compliance markets (e.g., EU ETS, ERF/ACCUs) | Voluntary markets (e.g., Verra, Gold Standard, ACR) | Blue carbon insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | Legally binding under national or regional law; crediting rules embedded in statutes or regulations and overseen by public authorities. | Managed by independent standards and registries with non-state governance; participation is discretionary and driven by net-zero and ESG commitments. | Blue-carbon projects often enter voluntary schemes first, where governance is more flexible, and later migrate into compliance systems once legal and regulatory frameworks are established. |

| Crediting approach | Project-based or sectoral crediting layered onto a capped system; additionality and leakage are addressed through statutory eligibility rules, standardized baselines, conservative default factors, and, in some cases, sector-wide caps or limits on offset use. | Methodology-defined additionality tests (e.g., barrier, investment, and performance-standard benchmarks) and explicit project-level leakage assessments; broader project types and co-benefit focus, but greater variation across standards and methodologies. | Blue-carbon crediting has so far been pioneered mainly in voluntary standards (e.g., VM0033), where additionality and leakage tests can be tailored to dynamic coastal settings; once methods are proven, compliance schemes such as Australia’s tidal-restoration method provide more stable, regulated demand. |

| MRV | Periodic, regulator-supervised MRV with strict compliance auditing; verification requirements and sampling designs are prescribed in regulation or approved methodologies. | MRV requirements are set by standards but may allow more flexible cycles, third-party verifiers, and use of digital tools and remote sensing; enforcement depends on registry rules and market discipline. | High MRV costs for mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows are a barrier in both systems; combining compliance-grade protocols with digital MRV innovations piloted in voluntary markets can lower unit costs for blue carbon while maintaining integrity. |

| Pricing drivers | Prices are primarily determined by regulatory cap-and-trade dynamics, allowance supply, and compliance demand; offset units may trade at a discount to allowances and are often subject to quantitative limits. | Prices are influenced by project quality, transparency, perceived integrity, and documented co-benefits; labels and ratings can create strong differentiation between projects. | Blue-carbon projects with robust MRV and verified co-benefits (e.g., storm protection, biodiversity, livelihoods) can command significant price premia in voluntary markets, while future inclusion in compliance systems could provide more predictable but potentially lower baseline prices. |

| Recent innovations | Integration with Article 6 mechanisms and national ETS frameworks; emerging experimentation with nature-based solutions, dynamic buffers, and insurance within some compliance programs. | Rapid innovation in digital MRV, dynamic buffer design, insurance products, and co-benefit stacking or bundling, often tested first at project scale. | Blue-carbon pilots are already using tools such as dynamic buffers, habitat-condition triggers, and insurance (e.g., storm-index products), which can inform the design of future blue-carbon methods in both voluntary and compliance markets. |

| Key challenges | Limited and slow inclusion of nature-based solutions; conservative eligibility rules and political risk can restrict blue-carbon categories; administrative complexity can deter smaller projects. | Ongoing critiques of additionality, permanence, and leakage; heterogeneous standards and variable project quality create reputational risk and potential over-crediting concerns. | For blue carbon, unresolved questions on baselines, permanence, and leakage are central in both systems. EAM-based monitoring and transparent indicators offer a pathway to demonstrate integrity and address rating-agency and investor concerns over credit quality. |

Comparison of compliance and voluntary carbon markets and blue carbon insights.

3.2 Blue-carbon-specific standards and schemes

Over the past 15–20 years, several standards have created explicit pathways for coastal ecosystems to generate credits. Under the UNFCCC’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), early afforestation/reforestation methodologies—AR-AMS0003 (small-scale, 2007) and AR-AM0014 (large-scale, 2011)—enabled mangrove planting on degraded wetlands to be credited as A/R projects. These instruments largely treated mangroves analogously to terrestrial forests, with limited attention to tidal dynamics and sediment processes.

A major conceptual step occurred when Verra introduced VM0033: Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration in 2015, later updated to Version 2.1 (Verra, 2015, 2023). VM0033 provides a standardized framework for quantifying greenhouse gas benefits from tidal wetland and seagrass projects, including:

-

project boundary definitions that account for hydrological connectivity;

-

baseline and additionality tests in dynamic coastal settings;

-

guidance on belowground biomass and soil organic carbon pools; and

-

explicit treatment of methane and nitrous oxide fluxes.

At the national level, the Australian Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative—Tidal Restoration of Blue Carbon Ecosystems) Methodology Determination 2022 allows tidal re-introduction projects to earn Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) under the Emissions Reduction Fund (Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022a, 2022b). The Determination prescribes eligibility conditions, hydrological restoration requirements, a 25-year crediting period, and site-specific MRV obligations, effectively embedding blue carbon within a compliance framework.

Regionally, the Andalusian Blue Carbon Standard for Certification of Blue Carbon Credits defines rules for seagrass and salt marsh restoration projects in southern Spain, including additionality criteria, monitoring protocols, and a Guarantee Fund to manage reversal risk (Regional Government of Andalusia, 2023). In East Asia, Japan’s emerging J-Blue Credit system, developed under the Japan Blue Economy Association with government support, certifies carbon removals from seagrass and seaweed projects and explicitly promotes co-benefits such as fisheries enhancement and coastal protection (Kuwae et al., 2022b; Okano, 2024; QPINTEL, 2025).

Collectively, these schemes demonstrate that blue carbon can be integrated into both voluntary and compliance markets where methodologies are robust. They also provide real-world laboratories for understanding how integrity principles—additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control—must be interpreted in coastal settings, and how EAM can help operationalize these principles.

3.3 Integrity challenges specific to blue carbon

Despite methodological advances, blue carbon projects face distinct integrity challenges that differ from many terrestrial land-use activities. These challenges arise from physical dynamics (e.g., tides, storms, sea-level rise), biogeochemical complexity (e.g., sediment carbon, allochthonous inputs), and governance conditions (e.g., tenure in intertidal zones). Four dimensions are particularly salient.

Additionality and baselines. In highly dynamic coastal environments, counterfactual scenarios are difficult to define. Tidal wetland and seagrass baselines must account for sea-level rise, sediment supply, upstream land-use change, and coastal protection policies (IPCC, 2013, 2019b; Howard et al., 2014). Mis-specified baselines risk either over-crediting (if natural recovery is underestimated) or under-crediting (if degradation pressures are ignored). VM0033 and the Australian tidal restoration method both address this by requiring credible evidence of degradation and specifying conservative baseline assumptions, but project developers still face substantial analytical burdens in data-poor settings (Verra, 2023; Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022a).

Permanence and reversal risk. Blue carbon stocks, particularly in soils and sediments, can be vulnerable to extreme events (storms, marine heatwaves), chronic erosion, or renewed human disturbance (e.g., renewed reclamation, dredging). Managing these risks requires a combination of:

-

conservative buffer pools and, in some cases, insurance or other financial instruments;

-

early-warning indicators (e.g., vegetation loss, shoreline retreat, elevation change); and

-

clear rules for reversal accounting (Lovelock and Duarte, 2025; Menéndez et al., 2020; Narayan et al., 2016).

MRV complexity and cost. Compared to many terrestrial projects, blue carbon MRV must incorporate submerged or water-logged soils, tidal gradients, and, for seagrass, sub-tidal mapping. Sediment coring, bulk-density and carbon-fraction analyses, and source apportionment (autochthonous vs. allochthonous carbon) all increase technical complexity and unit costs (Howard et al., 2014; Kennedy et al., 2010; Oreska et al., 2018, 2020; Macreadie et al., 2019). Emerging digital and remote-sensing tools offer partial solutions but are not yet evenly accessible across regions (Pham et al., 2019; Malerba et al., 2023). In practice, methodologies such as VM0033 illustrate these trade-offs clearly: while methodological clarity and comprehensive treatment of soil and biomass pools enable crediting, the intensity of sediment sampling, source apportionment and long-term monitoring substantially increases MRV cost and verification demands (Verra, 2023; Howard et al., 2014; Oreska et al., 2018, 2020).

Leakage and safeguards. In many coastal zones, restoration or protection of mangroves, salt marshes, or seagrass meadows interacts with fisheries, aquaculture, and coastal development. Without careful design, restoration may displace activities (e.g., fishing effort, small-scale aquaculture, or informal harvesting) to other areas, undermining net mitigation or social legitimacy (World Bank, 2019; Seddon et al., 2020). Standards increasingly require social and environmental safeguards, but implementation often depends on local governance capacity and stakeholder trust.

These challenges are not purely technical; they directly affect how rating agencies, investors, and regulators assess credit quality. Importantly, they also align closely with the information and decision needs that EAM is designed to address: defining indicators, monitoring responses, learning about system dynamics, and adjusting management.

3.4 Implications for the EAM–market integration framework

From an EAM perspective, the integrity challenges above can be recast as design questions:

-

Which ecological and social indicators should be monitored to inform additionality, permanence, MRV reliability, and leakage control?

-

What thresholds or triggers should prompt corrective action (e.g., buffer adjustments, management changes, or issuance delays)?

-

How can monitoring be structured to both satisfy standards (VM0033, ACCU, Andalusian, J-Blue, etc.) and generate learning about system behavior under climate and human pressures?

-

How should project-level data be aggregated to inform national or regional policy and financing decisions?

Answering these questions requires the kind of iterative, participatory, and evidence-driven management cycle that lies at the core of EAM (Holling, 1978; Walters, 1986; Williams et al., 2009, 2014; Norberg and Cumming, 2008). In the remainder of the paper, we therefore treat the standards and schemes outlined above as boundary conditions, and analyze how EAM can be used to design projects and governance arrangements that:

-

satisfy the integrity requirements of leading blue carbon methodologies;

-

reduce perceived risks for investors and rating agencies; and

-

support scalable, long-term stewardship of blue carbon ecosystems in countries such as China.

In summary, the convergence of compliance rigor and voluntary innovation is reshaping carbon market governance. For blue carbon, integrating EAM across both systems provides a pathway to achieve higher-quality credits, attract sustainable finance, and align ecosystem restoration with global climate and biodiversity objectives. Sections 4 and 5 draw on international and Chinese cases to illustrate these linkages in practice, while Section 6 develops a conceptual framework and operational roadmap that embed EAM into blue carbon trading mechanisms and financing structures.

4 International case studies

Different governance approaches around the world provide practical examples of how EAM can be integrated with carbon trading to enhance blue carbon outcomes. In line with our conceptual framework (Section 6 and Figure 1), the international cases reviewed here are not presented as generic project narratives, but as governance archetypes that illustrate how EAM functions—iterative planning, monitoring, adjustment, and stakeholder participation—support market integrity requirements (additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control) and co-benefit delivery. The selected examples from Kenya, Australia, the United States, and Japan correspond broadly to community-led, policy-driven, experimental, and multi-stakeholder models, respectively, and highlight transferable lessons for China’s emerging blue carbon market (Herr and Landis, 2016; Vanderklift et al., 2022; Kuwae et al., 2022b; Farahmand et al., 2025).

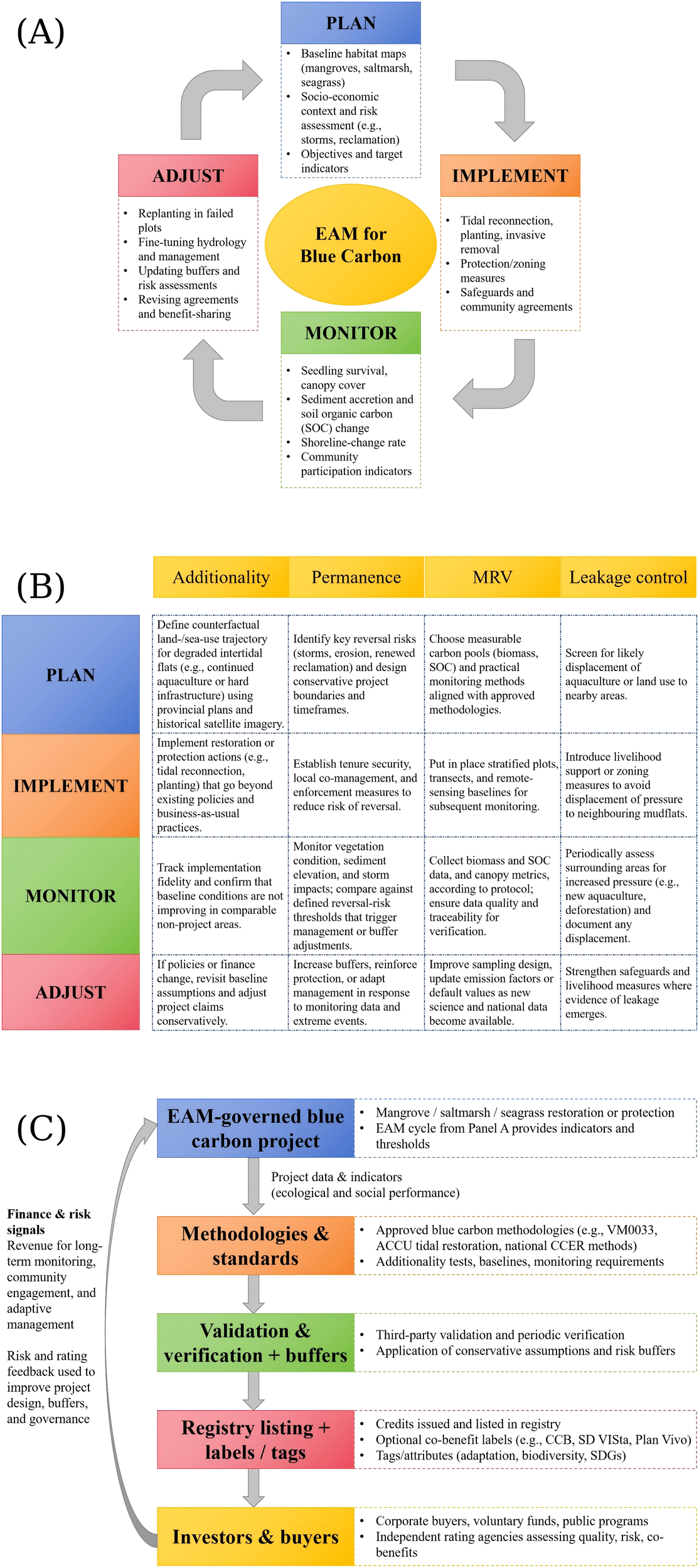

Figure 1

EAM–market integration framework for blue carbon projects. (A) EAM cycle tailored to coastal blue carbon ecosystems, showing iterative planning, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment steps and example indicators (e.g., seedling survival, canopy cover, sediment accretion, soil organic carbon change, shoreline-change rate, community participation). (B) Mapping of EAM functions onto core carbon-market integrity dimensions—additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control—using a stylised mangrove restoration project in coastal China as a worked example. For each dimension, the panel illustrates how EAM generates evidence (e.g., counterfactual baselines, reversal-risk triggers, stratified sampling, leakage screening) that can be used in accreditation. (C) EAM-informed credit-issuance and finance pipeline: project-level EAM data flow through methodologies and standards to validation, verification, and credit issuance with buffers; credits are then priced and, where relevant, rated by markets and investors, with revenues and risk signals feeding back to support long-term monitoring, community engagement, and adaptive ecosystem interventions. The outer enabling environment (laws, policies, institutional coordination, community co-management) shapes both EAM practice and market design.

Among these, we deliberately treat Mikoko Pamoja as a worked example to illustrate how the EAM cycle (plan–implement–monitor–adjust), associated MRV, and finance and risk signals unfold over time in a community-based blue carbon project. In contrast, the subsequent cases in Australia, the United States, and Japan focus more on regional and national schemes that embed EAM principles in approved methodologies and standards, validation and verification with buffers, and registry-based trading architecture.

4.1 Community-based initiative: Mikoko Pamoja in Kenya

Kenya’s Mikoko Pamoja project is widely recognized as the world’s first community-based mangrove carbon credit initiative. Launched in 2013 in Gazi Bay, the project engages local communities in the conservation and reforestation of 117 hectares of mangroves, with villagers serving as forest stewards and planters. Through a Plan Vivo-certified scheme, Mikoko Pamoja generates approximately 3,000 metric tons of CO2-equivalent in emissions reductions per year from avoided mangrove loss and new planting (UNDP, 2020; Wylie et al., 2016). These certified reductions are sold as carbon credits on voluntary markets, providing an annual revenue of around US$12,000 for the community.

What makes this project exemplary is its strong EAM approach – high levels of local participation, adaptive governance, and co-benefit sharing. In fact, over 30% of the carbon revenue is reinvested in local development priorities such as education, clean water infrastructure, and livelihood diversification (UNDP, 2020). For example, the community has used funds to install water pumps for thousands of residents and to supply school materials for children (UNDP, 2020). The project also planted alternative timber woodlots to relieve pressure on mangroves, an adaptive measure to address community needs (UNDP, 2020).

Wylie et al. (2016) report that Mikoko Pamoja’s success in delivering both climate mitigation and socio-economic benefits is tied to this inclusive, ecosystem-based management model where local stakeholders actively guide resource use and adjust practices over time. The result is a virtuous cycle: healthier mangrove ecosystems sequester carbon and bolster coastal protection, while the community receives direct incentives to sustain conservation. Mikoko Pamoja demonstrates that a well-designed, community-driven EAM approach can generate verified carbon offsets and direct the proceeds toward local resilience – effectively integrating blue carbon into a payment for ecosystem services model that benefits both people and nature (Wylie et al., 2016). This Kenyan case provides a blueprint for how grassroots initiatives can harness carbon finance for ecosystem stewardship, and indeed it has inspired similar projects (e.g. the Vanga Blue Forest in Kenya) following the same model of adaptive co-management and carbon credit sales to fund community development.

Viewed through our EAM–market framework, Mikoko Pamoja exemplifies a community-led EAM model in which local institutions set objectives, monitor ecological and social indicators, and adjust management in response to feedback (Wylie et al., 2016; Huxham et al., 2015). These adaptive arrangements underpin additionality and permanence in the voluntary standard, while participatory monitoring and benefit-sharing strengthen safeguards and recognition of co-benefits such as livelihoods and education (UNDP, 2020; Herr and Landis, 2016).

From a temporal perspective, Mikoko Pamoja follows an EAM-like sequence: initial feasibility assessment and community consultations feeding into project design and Plan Vivo registration; an early phase of baseline monitoring and restoration; and repeated plan–implement–monitor–adjust cycles, whose ecological and social indicators are fed through approved methodologies into third-party validation and verification, conservative risk buffers, and registry listing of issued credits (Wylie et al., 2016; Plan Vivo Foundation, 2019; UNDP, 2020). For China, this suggests that blue carbon projects adopting an EAM approach will need to align local consultation and monitoring cycles with the timing of CCER methodology approval, third-party validation and verification, registry listing/credit issuance, and the reinvestment of revenues into further restoration and community priorities, rather than treating community engagement and MRV as one-off steps.

4.2 National policy framework: blue carbon credits in Australia

At the national level, Australia provides a leading example of policy-led integration of blue carbon ecosystems into a formal carbon market. In 2022, the Australian Government’s Clean Energy Regulator issued the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative—Tidal Restoration of Blue Carbon Ecosystems) Methodology Determination 2022, the first methodology under the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) that allows coastal wetland restoration projects to generate compliance carbon credits (ACCUs) (Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022a). Eligible projects include those that reintroduce tidal flow to degraded wetlands by removing or modifying tidal barriers and restoring natural hydrology. The methodology quantifies abatement from carbon sequestered in biomass and soils, as well as avoided greenhouse gas emissions (including methane and nitrous oxide) from improved water management.

The Determination sets a 25-year crediting period and requires proponents to demonstrate that tidal exchange has been restored and can be maintained over time. It also prescribes ongoing monitoring and reporting to verify that abatement is real and measurable. Project activities may include hydrological assessments, management of acid sulfate soils, and control of invasive species, ensuring that ecological processes are restored alongside carbon sequestration. While the official requirements are framed in technical terms, these conditions embed elements of EAM by obliging project developers to monitor ecological outcomes and adjust site management accordingly.

The Australian case illustrates how government policy can mainstream blue carbon by establishing clear methodologies and governance for ecosystem-derived carbon credits. By bringing tidal wetland restoration into a regulated carbon market, Australia demonstrates that adaptive ecosystem management and carbon trading can be mutually reinforcing: robust, science-based methods safeguard environmental integrity, while the revenue from ACCUs provides an incentive for sustained long-term management.

In our framework, Australia represents a policy-driven EAM model embedded in a compliance scheme. The tidal restoration methodology under the Australian Carbon Credit Unit (ACCU) program explicitly links ecological monitoring (e.g., hydrological status, vegetation condition) to eligibility, ongoing verification, and a defined crediting period (Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022a, 2022b). These rules effectively codify EAM functions—indicators, thresholds, and corrective actions—within MRV and buffer requirements, showing how national regulation can mainstream EAM principles into blue carbon crediting (Vanderklift et al., 2022; World Bank, 2023).

4.3 Regional pilot programs: coastal wetlands in U.S. carbon markets

In the United States, efforts to link coastal wetland conservation with carbon markets remain exploratory but have gained momentum at the subnational level. California has long evaluated whether tidal marsh and seagrass restoration could be integrated into its cap-and-trade system. Yet as of 2025, compliance offset protocols remain confined to categories such as forestry, ozone depleting substances, livestock methane, mine methane, and rice cultivation, with wetlands not formally included (CARB, 2025; State of Washington, 2025). Similarly, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) operates an offsets program, but coastal wetlands have not been added as an eligible category (RGGI, 2025).

At the same time, scientific research and pilot projects in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Bay have shown that re-wetting drained peatlands and restoring tidal marshes can reduce CO2 emissions, reverse subsidence, and sequester carbon (Deverel et al., 2020; Windham-Myers et al., 2023). These initiatives function as learning laboratories where developers, scientists, and regulators refine carbon estimation models, monitor long-term burial rates, and address issues such as permanence in the face of sea-level rise or disturbance.

In parallel, the voluntary carbon market has advanced more quickly. The American Carbon Registry has released a methodology specifically for California Delta and coastal wetland restoration, creating a localized pathway for crediting (ACR, 2017). However, the methodology was made inactive by ACR on December 31, 2022, as it relied on a performance standard additionality test that must be re-assessed every five years under ACR’s requirements.

Importantly, these initiatives demonstrate the potential to integrate carbon trading with EAM. In California’s pilot projects, adaptive measures have been applied to refine carbon accounting and mitigate land subsidence, while highlighting the broader climate and ecological functions of tidal wetlands (Windham-Myers et al., 2023; Mcleod et al., 2011). Such integration strengthens scientific credibility, builds stakeholder confidence, and supports the long-term inclusion of coastal blue carbon within carbon market mechanisms.

From an EAM–market perspective, these U.S. tidal-wetland pilots function as experimental EAM laboratories. Managers test restoration configurations, carbon models and monitoring protocols, then revise practices and assumptions based on observed subsidence reversal and carbon burial (Deverel et al., 2020; Windham-Myers et al., 2023). This learning-by-doing directly informs baseline setting, MRV design and reversal-risk management, laying the groundwork for future inclusion of coastal wetlands in compliance-oriented carbon schemes.

4.4 Multi-stakeholder model: Japan’s blue carbon and co-benefits approach

Japan provides a distinctive model for integrating ecosystem-based management with emerging blue carbon finance, one that emphasizes stakeholder engagement and ecosystem co-benefits alongside carbon sequestration. The Yokohama Blue Carbon Project, centered on eelgrass restoration, has involved municipal authorities, scientists, and local volunteers in planting and monitoring activities, and is regarded as one of Japan’s flagship pilot efforts (Reuters, 2024). Similar initiatives have been launched in other coastal cities such as Fukuoka, where local governments, fishery cooperatives, and businesses collaborate to manage restoration and funding mechanisms, demonstrating adaptive financing and participatory governance (Kuwae et al., 2022b). These projects reflect EAM principles, as they integrate scientific monitoring, stakeholder engagement, and flexible institutional arrangements into project design.

Institutionally, Japan has moved to formalize blue carbon into climate and economic policy through the development of the J-Blue Credit system, administered by the Japan Blue Economy Association with government authorization (QPINTEL, 2025). J-Blue Credits certify carbon removals from seagrass and seaweed restoration projects, and are explicitly promoted as delivering multiple co-benefits such as improved fisheries habitat, biodiversity conservation, and coastal protection (Okano Shohei, 2024). By early 2025, three Japanese blue carbon projects had been registered internationally, reflecting both the country’s scientific engagement and its institutional commitment to mainstreaming blue carbon in East Asia (Farahmand et al., 2025).

Japan’s approach demonstrates how embedding EAM into blue carbon projects can generate broader societal recognition and market interest. Community participation, local financing models, and continuous ecological monitoring have strengthened project legitimacy and resilience. This model underscores that projects framed around biodiversity, fisheries, and community resilience may attract greater policy and financial support than those focusing solely on carbon credit volumes.

In our framework, Japan illustrates a multi-stakeholder, co-benefits-oriented EAM model. Municipal authorities, scientists and communities jointly define objectives (carbon, fisheries, coastal protection), monitor indicators such as seagrass cover and habitat quality, and adapt restoration techniques and financing mechanisms over time (Kuwae et al., 2022b; JBE, 2025). The J-Blue Credit system then uses this adaptive evidence base to certify removals and market co-benefits, linking EAM cycles directly to credit quality, price premia and investor confidence (Farahmand et al., 2025).

4.5 Lessons from diverse governance models

Collectively, international cases illustrate diverse governance pathways for integrating EAM with carbon trading in blue carbon sustainability (Table 2).

Table 2

| Country/region | Governance model | Key features | EAM elements | Carbon trading mechanism | Lessons/implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | Community-led (bottom-up) | Mikoko Pamoja project; local community manages mangroves and shares benefits | Strong local stewardship; participatory governance | Plan Vivo certification; voluntary credits sold internationally | Community ownership and equitable benefit-sharing build legitimacy and sustainability |

| Australia | Policy-driven (top-down) | National “Blue Carbon Method” (2022) under Emissions Reduction Fund | Government monitoring and strict oversight | Integrated into compliance market (ERF/ACCUs) | Embedding blue carbon in national carbon markets can scale restoration with credibility |

| United States | Experimental, regional | Pilot projects in California Delta & Suisun Bay; science-focused | Adaptive monitoring; methodological innovation | Voluntary market methodologies (Verra, ACR) in use; no compliance credits yet | Regional pilots act as laboratories for refining methods and building pathways to compliance |

| Japan | Multi-stakeholder, co-benefit model | Yokohama Blue Carbon Project; municipal, scientific, and community collaboration | Participatory governance; ecological monitoring | J-Blue Credit system certifies carbon + co-benefits (fisheries, coastal protection) | Framing credits around ecosystem services and resilience increases legitimacy and market appeal |

Governance models of blue carbon integration.

In Kenya, the Mikoko Pamoja project represents a bottom-up, community-led model. Local residents manage mangroves, reinvest carbon revenues in social priorities, and ensure equitable benefit-sharing. The project’s credibility rests on stewardship, transparency, and co-benefits, highlighting how local ownership can secure long-term success (Wylie et al., 2016; Ocean Panel, 2023).

In Australia, the government has taken a top-down approach. The 2022 “Blue Carbon Method” under the Emissions Reduction Fund created a regulated pathway for tidal wetlands and seagrass projects to generate ACCUs. This demonstrates how strong national leadership and compliance integration can scale restoration while ensuring accountability (Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator, 2022b).

In the United States, regional pilot programs function as experimental platforms. Projects in California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta test methods for carbon burial and subsidence reversal while applying adaptive monitoring. Although wetlands are not yet part of compliance markets, voluntary standards provide a basis for future integration and policy learning (Herr and Landis, 2016; Windham-Myers et al., 2023).

In Japan, a multi-stakeholder and co-benefit model has emerged. The Yokohama Blue Carbon Project engages municipal authorities, scientists, and local communities in restoration and monitoring. Japan’s J-Blue Credit system certifies carbon removals from seagrass and seaweed restoration while marketing co-benefits such as fisheries enhancement and coastal protection, illustrating how EAM principles can raise legitimacy and market appeal (Reuters, 2024; Kuwae et al., 2022b; QPINTEL, 2025; Farahmand et al., 2025).

Despite their differences, these cases share a consistent lesson: treating blue carbon ecosystems not only as carbon sinks but as living systems—adaptively managed with stakeholder participation and multiple co-benefits—enhances both the credibility and sustainability of climate mitigation.

In terms of our integration framework (Section 6 and Figure 1), these cases can be interpreted as four governance archetypes—community-led, policy-driven, experimental, and multi-stakeholder—that operationalize EAM functions in different institutional settings. Each archetype couples specific adaptive indicators and decision rules to market mechanisms (e.g., performance-based issuance, dynamic buffers, co-benefit tagging), offering concrete design options for China as it builds a high-integrity blue carbon market. Section 6.7 explicitly draws on these archetypes to structure an operational roadmap for embedding EAM in Chinese methodologies, registries and financing instruments (Vanderklift et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023; World Bank, 2023).

5 Chinese practices and challenges

5.1 Emerging blue carbon methodologies and standards in China

China has made notable progress in developing methodologies and technical standards for blue carbon. At the national level, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) in October 2023 issued its first certified methodology for blue carbon ecosystems – Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Mangrove Afforestation (CCER-14-002-V01). This officially brings mangrove carbon sink projects into China’s CCER program (MEE, 2023). Building on this, in December 2025 the MEE issued two additional blue-carbon methodologies – Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Coastal Salt Marsh Vegetation Restoration (CCER-14-003-V01) and Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Seagrass Bed Vegetation Restoration (CCER-14-004-V01) – thereby expanding the scope of blue carbon covered by the national carbon market and creating standardized pathways for mangrove, salt marsh, and seagrass projects to generate CCERs (MEE, 2025a, b). Complementing this, the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) has focused on science-based accounting standards. Notably, a comprehensive industry standard Accounting methods for ocean carbon sink (HY/T 0349-2022) took effect in January 2023, defining accounting approaches for mangroves, salt marshes, seagrasses and other marine biota (MNR, 2022). In May 2023, MNR released a suite of six technical guidelines covering carbon stock assessment and monitoring methods for mangroves, coastal salt marshes, and seagrass beds, after pilot-testing these methods in key areas like the Yellow River Delta in Shandong Province and Caofeidian in Hebei Province (MNR, 2023). These guidelines, aligned with IPCC approaches and Chinese ecosystem data, fill a methodological gap by standardizing how blue carbon is measured and verified nationally.

At sub-national levels, several provinces and institutions have pioneered their own methodologies to kick-start blue carbon projects. Shenzhen broke new ground by publishing the nation’s first municipal-level methodology focused on mangrove conservation. The Methodology for Carbon Sequestration in Mangrove Protection Projects (Trial), issued in May 2023, provides a technical basis to quantify carbon benefits of protecting existing mangroves while also accounting for biodiversity co-benefits. This filled a gap for conservation-based carbon projects, which differ from afforestation projects (Shenzhen Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, 2023). Fujian Province has similarly developed a regional methodology: the Methodology for Mangrove Restoration Carbon Sink Projects in Fujian (V01) was filed in May 2023 under the provincial voluntary offset program (Fujian Forest Certified Emission Reduction, FFCER). Built on two decades of local mangrove research and international best practices, Fujian’s methodology provides a MRV-compliant protocol for projects like intertidal afforestation, pond-to-wetland conversion, and removal of invasive Spartina followed by replanting. It ensures that carbon sequestered by restored mangroves is measurable, reportable and verifiable, thereby enabling carbon credit generation while highlighting ecosystem service gains (Fujian Provincial Carbon Emissions Trading Working Coordination Office, 2023). Guangdong advanced provincial innovation with the Methodology for Mangrove Carbon Inclusive Projects (2023 Edition), issued by the Department of Ecology and Environment. Designed under the province’s “Carbon Inclusive” program, it standardizes accounting for mangrove protection and restoration, lowering entry barriers for smaller projects while recognizing co-benefits such as biodiversity and coastal resilience (Guangdong Provincial Department of Ecology and Environment, 2023). Shanghai introduced the Carbon Inclusive Methodology for Coastal Salt Marsh Wetland Restoration (SHCER01030012024I) in 2024, the first city-level protocol nationwide targeting salt marsh ecosystems. It establishes technical rules for quantifying carbon gains from marsh revegetation and hydrological rehabilitation, embedding salt marsh restoration into the city’s carbon inclusive framework (Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Ecology and Environment, 2024). Shandong released the Methodology for Seagrass Bed Carbon Sink Carbon Inclusive Projects in 2025, jointly issued by the provincial Departments of Ecology and Environment and Oceanic Administration. As China’s first provincial seagrass methodology, it provides MRV-based guidance for conservation and restoration, enabling seagrass carbon sinks to generate credits while highlighting fisheries and water quality co-benefits (Shandong Provincial Department of Ecology and Environment and Shandong Provincial Ocean Administration, 2025).

Collectively, the emergence of national and sub-national methodologies reflects an evolving multi-tiered framework (Li et al., 2024; Wei and Wang, 2024). It lays technical groundwork to bring mangrove, salt marsh, and seagrass projects into carbon trading, while emphasizing robust MRV to support adaptive management of these ecosystems (Table 3).

Table 3

| Region/authority | Methodology (Year) | Ecosystem focus | Level | Core features | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEE | Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Mangrove Afforestation (CCER-14-002-V01), 2023 | Mangrove afforestation | National | Defines MRV framework for new mangrove planting and long-term carbon storage | First set of national CCER methodologies covering mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass beds; provides a unified technical basis for blue-carbon projects to generate CCERs. | |

| Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Coastal Salt Marsh Vegetation Restoration (CCER-14-003-V01), 2025 | Coastal Salt Marsh Vegetation Restoration | National | Defines MRV framework for new salt marsh vegetation planting and long-term carbon storage | |||

| Methodology for GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Projects: Seagrass Bed Vegetation Restoration (CCER-14-004-V01), 2025 | Seagrass Bed Vegetation Restoration | National | Defines MRV framework for new seagrass bed vegetation planting and long-term carbon storage | |||

| Shenzhen | Methodology for Carbon Sequestration in Mangrove Protection Projects (Trial), 2023 | Mangrove conservation | Municipal | Provides MRV framework to quantify carbon benefits of mangrove protection; includes biodiversity co-benefits | First municipal-level methodology; fills gap for conservation-based projects beyond afforestation | |

| Fujian Province | Methodology for Mangrove Restoration Carbon Sink Projects (V01), 2023 | Mangrove restoration | Provincial | Covers intertidal afforestation, pond-to-wetland conversion, invasive Spartina removal and replanting | Based on two decades of research; underpins provincial FFCER scheme | |

| Guangdong Province | Methodology for Mangrove Carbon Inclusive Projects (2023 Edition) | Mangrove protection and restoration | Provincial | Carbon inclusive framework; standardized accounting with simplified access for small-scale projects | Expands participation through low barriers; aligns with provincial carbon inclusive trading | |

| Shanghai | Carbon Inclusive Methodology for Coastal Salt Marsh Wetland Restoration (SHCER01030012024I), 2024 | Salt marsh restoration | Municipal | First methodology for salt marsh ecosystems; rules for revegetation and hydrological rehabilitation | Embeds salt marsh into city-wide carbon inclusive mechanism | |

| Shandong Province | Methodology for Seagrass Bed Carbon Sink Carbon Inclusive Projects, 2025 | Seagrass conservation and restoration | Provincial | Provides MRV-based accounting for seagrass protection and planting; highlights fisheries and water quality | China’s first provincial seagrass methodology; opens pathway for seagrass credits | |

National and sub-national methodologies for blue carbon accounting in China.

5.2 Blue carbon pilot projects, trading initiatives and adaptive management

On-the-ground pilot projects across China’s coasts are translating these methodologies into practice – generating tradable blue carbon credits and linking ecosystem management with market finance. Guangdong Province was an early mover. In 2021, the Zhanjiang Mangrove Afforestation Project became China’s first blue carbon project to transact credits. Using an approved CDM methodology for mangrove reforestation, the project involved planting 380 hectares of mangroves in degraded coastal areas of the Zhanjiang Mangrove National Nature Reserve. It achieved dual validation under Verra’s VCS and Climate, Community & Biodiversity (CCB) standards, marking it as the first Chinese blue carbon project registered to international carbon standards. In June 2021, a landmark deal was struck: the Beijing Entrepreneurs Environmental Foundation purchased the first batch of 5,880 tons of CO2 reductions at ¥66/ton, with proceeds supporting local mangrove protection, restoration and community co-management. This Zhanjiang case demonstrated how carbon trading can incentivize ecosystem-based management – the funds not only offset the buyer’s footprint but were reinvested in resilience of the mangrove reserve (e.g. restoration and community programs), embodying a win-win for climate and coastal livelihoods (SEE Foundation, 2023; China Daily, 2022; Li et al., 2024). It set a precedent that inspired other regions to explore blue carbon finance.

Following Zhanjiang’s lead, diverse market mechanisms for blue carbon have emerged nationwide. Xiamen City established the country’s first dedicated marine carbon trading platform in mid-2021. Shortly after its launch, the platform completed China’s first ocean carbon credit trade in September 2021 – the Quanzhou Luoyang River Mangrove Restoration Project sold 2,000 tons of mangrove-generated carbon credits via the Xiamen Exchange (Paulson Institute, 2021; Wei and Wang, 2024; Li et al., 2024). Uniquely, this project combined invasive Spartina removal with native mangrove replanting, yielding multiple co-benefits: enhanced carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery, water quality improvement, and reduced siltation. The transaction’s success was underpinned by the Xiamen-developed mangrove methodology, and it achieved “synergistic gains in carbon sink function and biodiversity protection” as well as community development benefits. Xiamen’s initiative exemplifies EAM in action – scientists and local officials monitor the restored wetland’s growth and adjust practices (e.g. controlling invasives, optimizing planting density) to maximize long-term carbon uptake and ecological health, while the carbon credits provide revenue to fund these ongoing efforts. By early 2022, Xiamen’s blue carbon platform had facilitated additional innovative trades, including a 15,000 ton credit deal from a marine aquaculture carbon sink project (the nation’s first “blue carbon fishery” trade) and a mangrove restoration credit purchase by a major green finance fund. These pilots, backed by partnerships between the exchange, research teams, and buyers like Industrial Bank, illustrate how carbon finance can be leveraged to support adaptive marine ecosystem management and new “blue finance” products (e.g. Xiamen’s Blue Carbon Fund).

Other coastal provinces have also launched notable blue carbon projects, often integrating universities and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) for scientific support. Hainan, with its extensive mangroves and seagrass beds, completed its first blue carbon deal in May 2022. The Haikou Sanjiang Mangrove Restoration Project transferred over 3,000 tons of CO2 credits (accumulated over 5 years) to a private company, representing a breakthrough in monetizing Hainan’s mangrove conservation efforts (CGTN, 2025; China Green Carbon Foundation, 2022). Meanwhile, Hainan’s Lingshui county, in partnership with the China Green Carbon Foundation and Conservation International, developed a mangrove carbon project under VCS – by March 2022 it had finished project design, monitoring, and third-party validation, positioning it as Hainan’s first international mangrove carbon offset project (Carbonstop Research Institute, 2023; Irvine-Broque, 2022). Shenzhen has pursued a high-profile model focused on conserving an existing mangrove ecosystem. In September 2023, the Shenzhen Mangrove Nature Reserve (Futian) hosted China’s first auction of mangrove carbon credits derived from protecting standing forests. With an opening price of ¥183/ton, intense bidding drove the final price to ¥485/ton for the credits – far above typical domestic carbon allowance prices (Shenzhen Daily, 2023; IMC, 2025). The record-high price reflects not only the carbon value but also the significant ecological and social value co-generated by the Futian mangroves (habitat for endangered species, coastal protection, etc.). Shenzhen’s Planning and Natural Resources Bureau had earlier issued a tailored methodology for such protection projects, ensuring the auctioned credits were grounded in solid monitoring of the mangroves’ carbon uptake. The revenue from this sale is channeled back into the reserve’s management and community education, exemplifying how adaptive conservation (patrolling, replanting degraded spots, public engagement) is being financed through carbon markets. Shenzhen’s experiment, under the city’s new status as host of the International Mangrove Center, is viewed as a replicable model to turn ecosystem services into economic assets.

Crucially, pilot projects have expanded beyond mangroves to other blue carbon ecosystems, often under the guidance of academic experts. In September 2023, Jiangsu Province achieved China’s first salt marsh carbon credit transaction. At the Global Coastal Forum in Yancheng, the Yancheng Rare Birds National Nature Reserve signed an agreement to sell carbon credits generated from a coastal salt marsh restoration project to Tencent, a leading tech company. The project’s net carbon sequestration since 2018 was quantified using Xiamen University’s salt marsh methodology, and the deal marked a “zero-to-one breakthrough” for salt marsh blue carbon trading. This salt marsh project is notable for its strong adaptive management dimension: it was implemented in phases (the second phase credits were sold in 2024) and accompanied by continuous ecological monitoring in the Yancheng wetland (a UNESCO World Heritage site). Researchers track vegetation recovery, soil carbon changes, and hydrology in the restored marsh, feeding back findings to improve restoration techniques and validate carbon gains (Yancheng Municipal People’s Government, 2023). Similarly, seagrass bed restoration has entered China’s nascent blue carbon market. In June 2024, the media-reported first seagrass carbon credit purchase was publicly signed: Tencent agreed to buy all carbon credits produced since 2018 by a 28.12 ha seagrass restoration in Guangxi’s Hepu Dugong National Reserve. This seagrass project was part of the BLUE-CARE program led by Xiamen University, which provided a science-based methodology for measuring seagrass carbon sequestration and guided the restoration process. Notably, at the same ceremony, a second tranche of salt marsh credits from Yancheng’s project was also sold to Tencent, reinforcing the trend of corporations partnering with conservation authorities and researchers to invest in blue carbon (UNDP, 2023; Tencent, 2023).

Across these cases – from Guangdong’s mangroves to Jiangsu’s coastal salt marshes – the principles of EAM are increasingly intertwined with carbon trading. Each pilot involves setting up long-term monitoring of carbon sequestration and ecological health, and using feedback to adjust management. For example, the mangrove projects in Zhanjiang and Quanzhou engaged local communities in monitoring survival and growth of plantings, allowing timely interventions (replanting, hydrological tuning) to ensure carbon targets are met. The salt marsh and seagrass projects were initiated as scientific experiments, where restoration methods were iteratively refined (e.g. transplant techniques, nutrient management) based on periodic evaluations of carbon accumulation and habitat recovery. In turn, the carbon market provides a financial incentive and feedback loop: higher credit prices (such as Shenzhen’s auction or the Ningbo macroalgae auction at ¥106/ton) signal the value of healthy, well-managed ecosystems, encouraging local governments to adapt and upscale such projects (China Daily, 2023). Many pilots also use carbon revenue to fund ongoing stewardship – for instance, the foundation buying Zhanjiang’s credits invested additional ¥7.8 million into mangrove patrols, restoration and community co-management, and Xiamen’s Blue Carbon Fund reinvests proceeds into new restoration projects and research (IUCN, 2024). This integration of adaptive ecosystem management with carbon finance is helping to address some key challenges noted by scholars. It provides steady funding for long-term monitoring (mitigating data scarcity), encourages the refinement of carbon estimates (reducing uncertainties in sequestration rates), and forges stronger links to carbon markets that can sustain projects beyond initial pilot phases. Nevertheless, fragmented governance and unclear property rights remain major hurdles in China’s blue carbon development (Xu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024), while the immaturity of accounting standards continues to constrain large-scale implementation (Liu et al., 2024). The Chinese experience to date suggests that combining ecosystem-based approaches with carbon trading—anchored in robust MRV, pilot demonstrations, and policy/legal support—offers a promising pathway to scale blue carbon while safeguarding ecosystem resilience (Xu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; World Bank, 2023; Li and Liu, 2024).

5.3 Ecosystem-specific financial and technical constraints and EAM-aligned responses in China

Although China has made rapid progress in blue carbon methodologies and pilot projects, ecosystem-specific financial and technical constraints still shape how mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows can participate in emerging markets. Mangrove projects are furthest advanced because they combine relatively clear jurisdiction and protection baselines, visible above-ground biomass, and more mature accounting methods (e.g., CCER-14-002-V01). These features lower MRV costs per ton and make it easier to support monitoring with remote sensing. By contrast, salt marsh and seagrass projects face higher unit costs and longer data-maturation curves. Key challenges include seasonal or sub-tidal habitat dynamics that complicate mapping, sediment-focused MRV that depends on coring, bulk-density and carbon-fraction analyses, greater exposure to storms and erosion, and more complex tenure or usage rights in submerged lands. Together, these factors increase uncertainty around additionality, permanence, and delivery, and therefore weaken the business case for private co-investment despite strong ecological potential.

From a market-integrity perspective, these ecosystem-specific constraints translate directly into how easily projects can demonstrate additionality, permanence, robust MRV, and limited leakage. In data-poor seagrass and salt marsh contexts, baseline trajectories are harder to specify, and source apportionment between autochthonous and allochthonous sediment organic carbon remains uncertain. In such settings, conservative accounting practices—such as applying transparent allochthonous discounts with sensitivity tests and documenting plans for progressive refinement—can reduce the risk of over-crediting but may also depress expected credit volumes. For example, building on isotopic constraints reported by Kennedy et al. (2010) and operational guidance in Howard et al. (2014), subsequent syntheses indicate that non-seagrass (allochthonous) sources account for roughly 50% of sediment organic carbon in many seagrass meadows (Oreska et al., 2018, 2020). In the absence of site-specific partitioning, a conservative 50% allochthonous discount has therefore been used in some pilots, combined with sensitivity analysis and transparent uncertainty reporting. Similarly, higher exposure to storms and erosion in some salt marsh and seagrass settings requires larger buffer contributions or insurance-type arrangements to manage reversal risk, which directly affects net revenues and perceived financeability.

EAM provides a unifying lens to turn these constraints into design parameters rather than vetoes. For seagrass and salt marsh, EAM encourages projects to treat conservative interim assumptions (e.g., for allochthonous carbon fractions) as hypotheses to be tested and updated through adaptive monitoring—for instance, by combining remote-sensing–based habitat baselines with stratified field sampling, targeted sediment coring, and, where capacity allows, δ¹³C or biomarker analysis. Monitoring cadences can be explicitly synchronized with verification windows, and reversal-risk triggers (e.g., canopy loss thresholds, storm intensity indicators, or shoreline-change rates) can be linked to dynamic buffer adjustments and corrective management actions. For mangroves, EAM can guide decisions about planting densities, hydrological reconnection, invasive removal, and post-storm recovery interventions in ways that maintain both carbon stocks and co-benefits over time, while generating the data needed to support verification and rating assessments.

These ecosystem-specific financial and technical constraints thus form a critical bridge between China’s practical experience and the integration framework developed in Section 6. They help to specify which indicators, thresholds, and decision rules are most relevant for different blue carbon ecosystems, and how these should be linked to issuance logic, buffer design, and financing instruments. A consolidated summary of ecosystem-specific constraints, their associated market barriers, and EAM-aligned remedies for mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows in China is presented in Table 4.

Table 4

| Ecosystem | Typical constraints | Market barriers | Practical remedies (EAM-aligned) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mangroves | Tenure overlaps; storm damage risk | Permanence risk and permitting delays | Remote sensing + plot MRV; storm triggers ↔ buffer; co-management agreements |

| Salt marsh | Mapping seasonality; sediment coring cost | High MRV cost per unit and delivery uncertainty | Stratified sampling; digital MRV; phased issuance with adaptive thresholds |

| Seagrass | Sub-tidal mapping; source apportionment | Accounting uncertainty and limited laboratory capacity | 50% allochthonous proxy with sensitivity tests; δ13C/bio-markers as capacity grows; RS habitat baselines |

Key constraints, market barriers, and EAM-aligned remedies across China’s blue-carbon ecosystems.

Building on the ecosystem-specific constraints and remedies summarized in Table 4 and the pilot experiences above, Table 5 synthesizes the key market and governance barriers, near-term opportunities, and actionable recommendations for scaling high-integrity blue carbon in China.

Table 5

| Domain | Key barriers (China-specific) | Near-term opportunities | Actionable recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance & tenure | Overlapping agency mandates across sea-area, wetlands, forestry, and ecology; unclear tenure/carbon ownership in intertidal/subtidal zones; sequential permits slow implementation. | The 2022 Wetland Protection Law and growing inter-ministerial coordination; local “carbon-inclusive/blue-carbon” pilots generating experience. | Issue joint guidance clarifying use rights and carbon ownership for intertidal/subtidal areas; establish one-stop approvals for tidal reconnection/invasive removal; standardize stewardship obligations in project documents. |

| Methodologies & MRV | Newly issued methods for seagrass and salt marsh still rely heavily on conservative default factors and limited monitoring data, constraining site-specific calibration and uncertainty reduction. | National and provincial methodologies now cover mangroves, salt marsh, and seagrass; early CCER and carbon-inclusive pilots, together with improving remote-sensing and digital MRV tools, provide a platform to test and refine default factors. | Treat current default factors for seagrass and salt marsh as conservative interim values; explicitly document uncertainty ranges and sensitivity tests; channel data from pilots and sentinel sites into scheduled methodology revisions, aligning monitoring indicators and cadences with these update cycles. |

| Market architecture & finance | Blue-carbon credits now have a defined pathway into the unified national carbon market and its price discovery mechanisms, but there is still no nationally endorsed framework to differentiate blue carbon or grant it a systematic price premium, which weakens incentives for long-term ecosystem restoration investment. | Municipal pilots (e.g., Shenzhen, Xiamen, Yancheng) and dedicated funds; rising corporate net-zero demand for high-quality nature-based credits. | Establish a nationally endorsed blue-carbon label and registry/auction function within the existing market; publish issuance calendars tied to verification cycles; pilot performance-linked finance and insurance with dynamic buffers for reversal risk. |

| Data & capacity | Fragmented parameter/factor libraries; weak cross-province comparability; uneven third-party lab capacity. | Industry standards and technical guidelines issued; continued pilots in priority regions. | Build a national open factor library (Tier 2/3) for all three ecosystems; conduct inter-calibration across labs; fund longer time series at sentinel sites. |

| Community & safeguards | Inconsistent co-management, benefit-sharing, and grievance mechanisms; social co-benefits hard to translate into price. | Demonstration projects (e.g., mangrove protection auctions) show premium potential. | Require participatory monitoring & benefit-sharing in design; enable labels/tags for verified co-benefits to support price premia; allow stacked.instruments where separate methodologies exist (avoid double counting). |

| International alignment | Unclear alignment with Article 6 and national inventory accounting; project-to-inventory nesting rules not explicit. | NDC, national inventory work, and local pilots are advancing in parallel. | Publish nesting guidance (project → provincial/national inventory); prepare Article 6 compatibility notes; harmonize project MRV with HY/T and IPCC guidelines. |

China’s blue-carbon market: barriers, opportunities, and recommendations.

6 A conceptual framework for integration

6.1 Foundations of EAM

Building on the theoretical discussion in Section 2, we now position EAM explicitly as the left-hand side of our integration framework. EAM is treated here as a structured, iterative cycle of planning, implementation, monitoring, and adjustment under uncertainty (Holling, 1978; Walters, 1986; Williams et al., 2009, 2014). In blue-carbon contexts, this cycle is organized around jointly defined ecological and social objectives (e.g., carbon stocks, shoreline stability, biodiversity, livelihoods), measurable indicators, and decision rules that specify how management actions change when thresholds are crossed. Figure 1A summarizes this EAM cycle for blue carbon ecosystems, highlighting the four core steps (plan, implement, monitor, adjust) and typical ecological and social indicators that can be tracked in mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows.

Rather than re-stating the full theory, the purpose of this section is to clarify which components of the EAM cycle can serve as inputs to carbon-market accreditation and financing decisions. In the paragraphs that follow, we therefore link these EAM elements directly to core integrity requirements (additionality, permanence, MRV, leakage control) and to the investment and rating needs that ultimately determine whether blue-carbon projects can scale.

6.2 Carbon market integrity: requirements and methodologies

As summarized in Sections 3.1–3.3, carbon market mechanisms provide the financial and methodological infrastructure to transform ecological outcomes into tradable climate units. According to World Bank (2019), projects must satisfy four key conditions: additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control. These criteria are embedded in international standards such as Verra’s VM0033 Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration, and in compliance markets such as Australia’s Carbon Credits (Tidal Restoration of Blue Carbon Ecosystems) Determination 2022, which allows tidal reintroduction projects to generate ACCUs.

6.3 EAM–market integration: finance, accreditation, and the feedback loop

Building on the EAM foundations in Section 2 and the integrity requirements outlined in Sections 3.2–3.3, this subsection develops the core logic of our integration framework. Figure 1B schematically maps the same EAM functions to the four key integrity dimensions—additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage—using a stylized mangrove restoration project in coastal China as a worked example, while Figure 1C extends this logic from project design to the full project–credit–finance chain: EAM-governed projects supply indicators and data to methodologies, validation and verification; this, in turn, informs issuance schedules, buffers, labels and ratings, which shape credit prices and investor decisions; capital and risk signals then feed back into long-term monitoring, community engagement, and adaptive interventions. Beyond ecological performance, EAM directly enhances the financial credibility of blue carbon projects. Iterative monitoring and transparent data feedback reduce ecological and operational uncertainty, enabling investors to assess risk-adjusted returns more accurately and lowering the cost of capital over time (Smith et al., 2024; WWF-Canada, 2022; Brasil-Leigh et al., 2024). Periodic performance reviews, early-warning triggers, and corrective actions embedded in EAM help mitigate delivery and reversal risks—two core drivers of credit downgrades—thereby facilitating blended finance structures and performance-linked instruments (Badgley et al., 2022; Balmford et al., 2023; Payne Institute for Public Policy, 2022; OECD, 2023).

EAM also complements accreditation processes across leading standards (e.g., Verra’s VCS, Australia’s ACCU) by operationalizing additionality, permanence, MRV, and leakage control through adaptive indicators and decision rules. Participatory monitoring and co-management clarify social safeguards and benefit-sharing, strengthening the evidentiary basis for validation and verification and improving the likelihood of favorable assessments by credit rating agencies.

Building on these linkages between adaptive governance, accreditation, and finance, the integration of EAM and carbon markets is best conceptualized as a feedback loop that connects ecological indicators to market integrity and investment decisions. Through this loop, adaptive management strengthens the ecological credibility and resilience of blue carbon projects, ensuring that sequestration outcomes are real and durable (Friess et al., 2019). In turn, carbon markets mobilize financing for long-term monitoring, community engagement, and adaptive ecosystem interventions—activities that are often unaffordable without dedicated instruments such as blue carbon credits (IFC, 2023b). This reciprocal dynamic aligns with the broader principles of nature-based solutions (NbS): well-designed interventions should deliver climate benefits, biodiversity gains, and human well-being (Seddon et al., 2020).

In China, the emerging “Shenzhen model” around the Futian Mangrove Nature Reserve already illustrates both the opportunities and current limitations of such an EAM–market feedback loop (Sun et al., 2025a). Conservation activities on about 126 ha of mangroves have generated roughly 38,745 t CO2 of verified conservation credits for the period 2010–2020, a portion of which was sold in 2023 through the country’s first mangrove carbon-sink auction at a record clearing price of around 485 CNY·t-1, complemented by an index-based insurance product that pays out when storms or other hazards trigger pre-defined ecological thresholds. Yet the underlying monitoring framework still relies mainly on area and canopy metrics, with sediment processes, biodiversity co-benefits, and social safeguards only partially reflected in issuance rules. From an EAM perspective, this implies that the feedback loop is still weighted toward short-term credit delivery, and that a more diversified indicator set, explicit decision rules for adjusting buffers and management, and transparent disclosure of performance data would be needed to fully align finance, accreditation, and adaptive management in such schemes.