Abstract

The fishing industry has historically relied on the use of expanded polystyrene (EPS) and, sometimes, on wooden boxes for fish transport. However, these materials pose significant environmental and hygienic challenges, particularly due to the persistence of polystyrene in marine ecosystems and the porosity of wood, which undermines food safety. This study investigates the adoption of polypropylene-based eco-sustainable boxes, assessing the economic viability by a scenario simulation approach applied to a total of six case studies from the Italian fishing fleet. The findings indicate that the transition to polypropylene (PP) eco-boxes improves profitability across all fishing fleets with large scale fisheries (trawling and purse seine fleets) achieving increases in gross profit never below +21%. Smaller or less intensive fleets (longliners) see more modest average gains (in gross profit terms) between of +2.5% over the long-term horizon. So, although initial investments are higher, PP eco-boxes lead to cost savings over time, enhanced profitability and compliance with environmental and food safety standards. Furthermore, these initiatives have the potential to facilitate traceability and valorization of fish products, thereby increasing the overall benefits deriving from the utilization of eco-sustainable boxes. The study concludes that eco-sustainable boxes represent a feasible and beneficial innovation for the Italian fishing sector, with scalability potential across the Mediterranean.

1 Introduction

Expanded polystyrene (EPS), commonly known as “Styrofoam”, represents one of the most widespread marine litter components, both at sea and along coastlines (GreenReport, 2021). EPS is extensively employed in the fisheries sector as the primary material for fish storage and transport boxes, which are widely used in Italian fishing fleets. Recent estimates indicate that more than 50 million EPS boxes are used annually in Italy’s fishing industry, many of which end up at sea and fragment into microplastics, with severe implications for marine ecosystems (Marevivo, 2025). Similarly, WWF highlights that Italy alone consumes approximately 14,000 tonnes of EPS fish boxes annually, with minimal recycling rates, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable alternatives (WWF Italia, 2024). The main environmental concern lies in the fact that EPS is non-biodegradable and therefore extremely persistent. Ingestion of EPS has been documented across a variety of marine organisms, particularly surface feeders and species that use it as a habitat, leading to gastrointestinal injuries and related disorders (Turner, 2020). Once in the marine environment, EPS progressively fragments into large quantities of microplastics that are not visible to the naked eye, are ingested by microorganisms, and transfer trophically through the food web, ultimately reaching humans (Cózar et al., 2015; Marevivo, 2025). In response to these concerns, alternative solutions for the transport of fish are increasingly being explored, such as the use of alternative polymers as polyethylene (PE), polyurethane (PUR), (Ceballos-Santos et al., 2014; Hilmarsdóttir et al., 2024), or polypropylene (PP) distribution boxes (Hansen et al., 2012; Marevivo, 2025) Among them, PP boxes appear particularly promising from an environmental sustainability perspective. PP is an elastic polymer that can be reused multiple times and is fully recyclable. This option offers significant environmental benefits due to its reusability and recyclability. Drawing on EU case evidence, scaling recycling-oriented solutions for PP fish boxes could halve the fraction landfilled in Italy over a 3–5-year horizon (European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform, n.d.). Concurrently, the high reuse potential of PP containers is expected to reduce operating costs by spreading acquisition expenses over multiple use cycles, an effect likely to be most pronounced among large-scale fishing enterprises with large-scale production, for which packaging constitutes a substantial share of daily expenditures Marevivo, 2025). The use of fish boxes spans the entire supply chain, from on-board storage to wholesale and retail, since fish is typically placed in packaging units immediately after landing and transported in the same units to the final point of sale.

By providing qualitative and quantitative evidence on the costs and benefits associated with the adoption of PP boxes in Italian fisheries, the aim of the study has been to assess, on a preliminary basis, if economic benefits can drive the shift from EPS to PP boxes while cutting down the environmental footprint of fish transport.

Based on the main PP fish boxes currently available on the market, case studies were developed to quantify the evolving impacts of adopting eco-sustainable PP solutions on key economic performance indicators of six selected Italian fishing fleets characterized by higher production volumes, i.e. trawlers, purse seiners, pelagic pair trawlers, and longliners. A qualitative analysis was also conducted to examine the main benefits and/or challenges observed in fishing communities where PP boxes have already been adopted, with consideration of the implications for the broader supply chain.

For most case studies (trawlers, purse seiners, and pelagic pair trawlers), the analysis simulated the replacement of polystyrene boxes, with the primary goal of reducing reliance on a material that is both environmentally unsustainable and subject to rising costs due to increases in raw material prices. In contrast, longlines’ catches are predominantly transported in wooden boxes, which are generally larger than standard polystyrene ones and are often reused multiple times. A common question that arises is why replace a natural material such as wood with plastic—in this case, polypropylene? Although wood is a natural material, it is not considered optimal for fish transport for several reasons, particularly when boxes are reused. Wood is porous, retains residues, and promotes microbial growth, which compromises freshness and food safety, making it unsuitable for reuse in fish transport (Myers, 1981). In contrast, polypropylene (PP) boxes comply with EU hygiene legislation (Regulation EC 852/2004) as they can be washed and disinfected at controlled temperatures, ensuring HACCP compatibility and reducing cross-contamination risks throughout the supply chain (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 2020). Although a technical overview of materials used for fish boxes was not under the objective of this paper and full life-cycle carbon footprint was not developed in this study, available technical data have been gathered from the literature. Data indicate that PP multiuse boxes emit 1.2–1.6 kg CO2-eq per use cycle, compared to 3.5–4.0 kg CO2-eq for single-use EPS boxes (Almeida et al., 2022; Ceballos-Santos et al., 2024; Baltrocchi et al., 2025), suggesting that reuse can cut emissions by more than half when supported by efficient washing and reverse logistics. PP boxes also outperform EPS and wood in environmental impact: they are fully recyclable, reusable hundreds of times, and generate less waste and microplastic pollution. EPS, though good insulating, fragments into persistent microplastics, while wooden boxes deteriorate quickly, producing organic waste.

Recent findings from the NEPTUNUS project further suggest that while plastics often carry a lower climate footprint compared to alternative packaging such as aluminium or glass, the real environmental benefit is achieved when recyclability, eco-design, and improved recovery rates are ensured (Raugei et al., 2022). Overall, PP eco-boxes support circular economy goals and contribute to decarbonizing seafood supply chains in line with the EU Green Deal (Hilmarsdóttir et al., 2024; Turner, 2020).

2 Material and methods

2.1 Data collection

Input data for the subsequent analysis were obtained through complementary approaches: (i) aggregated economic data for the targeted fleet segments; (ii) a structured survey and (iii) market survey on plastic fish boxes.

Aggregated economic data included fleet size (number of vessels), employment (FTE and crew), revenues (landing values, other revenues, and subsidies), and costs (operational, fixed, and capital) for the years 2019–2021. These data were obtained from the Italian National Data Collection Programme, with authorization from the Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies (MASAF, 26/06/2023).

To complement these data, a sample of 25 vessels (12% of the target fleet) was selected based on their availability to reply but trying to ensure a certain representativeness across fleet segments; to ensure this, the vessels’ population was stratified by main fishing technique and vessel length.

The survey was conducted between 2021 and 2022 using structured questionnaires. The survey collected vessel-level information on box usage, fishing effort, commercial expenses, and related operational parameters. The fleet segments analyzed included: trawlers (DTS, 18–24 m and >24 m), purse seiners (PS, >12 m), pelagic pair trawlers (TM, >12 m), and longliners (HOK, >12 m) (Table 1). The survey was conducted in different ports in Adriatic and Ionian seas.

Table 1

| Segment | Gear | Area (GSA) | Vessel length | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTS1824 | Trawl | GSA18 | 18–24 m | 6 |

| DTS2440 | Trawl | GSA18 | >24 m | 1 |

| PS2440 | Purse seine | GSA17–18 | >24 m | 2 |

| TM1840 | Pair trawl | GSA17–18 | >18 m | 10 |

| HOK1218 | Longline | GSA19 | 12–18 m | 4 |

| HOK1824 | Longline | GSA19 | 18–24 m | 2 |

Fleet segments surveyed.

GSA17, Central-Northern Adriatic; GSA18, Southern Adriatic; GSA19, Western Ionian Sea.

Baseline information on box types currently used was collected prior to questionnaire administration. Standard 30×50 cm polystyrene EPS fish boxes were employed for trawlers, purse seiners, and pelagic pair trawlers, whereas longliners in GSA19 typically used 40×60 cm wooden boxes for medium-sized catches. For each surveyed vessel and year (2021–2022), collected data included vessel identifiers (EU registration number, registration office), commercial expenses (expressed in euros, both total and itemized), number and size of boxes used, fishing days, landing volumes, and the average box allocation per haul by size. The detailed questionnaire utilized for data collection is provided in Supplementary material/Annex I.

The data collected provided insights into the average share of expenditure for the purchase of boxes in relation to total commercial costs. These are defined as variable costs that depend on landing volumes and/or vessel operations (e.g., boxes, ice, transport), and are distinct from labor, fuel, and maintenance costs.

In the case of trawlers (DTS), the average incidence is around 30% (calculated across vessel length classes and reference years). The highest values are observed for purse seine and pelagic pair trawl fisheries, which are characterized by large landing volumes and, consequently, a substantial demand for boxes, resulting in higher annual expenditures. For longline fisheries, the incidence ranges between 56% and 60% of total commercial costs, primarily due to the use of wooden boxes, which have a higher unit cost – Table 2.

Table 2

| Share (%) of fish boxes costs over total commercial costs | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| HOK1218 | 56% | 62% |

| HOK1824 | 62% | 63% |

| DTS 1824 | 32% | 35% |

| DTS 2440 | 21% | 28% |

| TM1840 | 88% | 87% |

Percentage incidence of box costs/total commercial costs, 2021-2022.

The incidence for purse seine fisheries was estimated, as in practice the cost of boxes is borne by the intermediary/wholesaler, who deducts it from the transaction value.

To complete the input needs for the analysis phase, qualitative and quantitative information were collected on plastic fish boxes, commonly made of polypropylene (PP) or polyethylene (PE), which are intended to potentially replace polystyrene EPS boxes in most case studies, as well as wooden boxes used in longline fisheries. This information was obtained through a market survey targeting the main products currently available. During the survey, information was collected for three different small box products and one large box product (anonymized for confidentiality of the manufacturers), as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Type | Product ID | Key features | Material | Dimensions (cm) | Capacity (L/kg) | Maximum Price (€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | A | Stackable; with/without drainage holes | Polypropylene (PP) | n.a. (b) | 13 L | 2.70 |

| Small | B | Stackable; with/without drainage holes | High-density polyethylene (HDPE) | 52 × 36 × 12 | 13 L/up to 16 kg | 4.00 |

| Small | C (a) | Stackable; optional drainage holes; removable/drainable bottom; optional lid; RFID traceability; compatible with washing machine and sanitization system at +55°C | Polypropylene (PP) | 50 × 30 × 11 | 10–12 L/10–12 kg | 6.50 |

| Large | D(a) | 60 × 40 × 16 | 25–30 kg | price of C + 30%(c) |

Characteristics of surveyed plastic (PP and PE) fish boxes.

a) Products C and D include advanced features such as RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) traceability and compatibility with sanitization systems. b) It is assumed, based on the description, that the fish boxes have standard dimensions of approximately 30 × 50 × 12 cm. c) Not yet available but estimated at +30% compared to the smaller size (product C). For type D, the technical specifications are reported in italics as this product has not yet been introduced to the market.

As shown in Table 3, small boxes are broadly similar in dimensions and carrying capacity; however, substantial differences are observed in unit price, which primarily reflect variations in technical features. For small boxes, differences concern the material type (ranging from polyethylene to higher or lower-quality polypropylene) and product attributes, such as the presence of drainage holes. Depending on the species being transported, these holes may serve to retain or drain liquids.

Products C and D display a wider range of attributes, including standard drainage holes, a drainable bottom, the option to use a lid, and the most advanced feature: an RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) chip for traceability. Moreover, these products are designed to operate within a complex washing and sanitization system at +55°C, which further justifies their higher unit price. For these products, durability data were also collected, enabling assumptions to be made for short-, medium-, and extended usage periods. Considering all the technical elements described in Table 2 and that simulations using the highest-priced box can represent a “upper-bound scenario” to measure economic impacts, simulations were conducted using product C for the small box category, as it offers the best combination of technical features, durability, and traceability. Product D was the only option identified for the large box category and was employed in simulations for the two case studies related to longline fisheries.

2.2 Scenario simulation approach

The economic analysis was performed by defining a set of scenarios regarding the adoption of new plastic fish boxes, differentiated across the selected case studies according to the fishing technique. For each case study, a Status quo scenario was simulated by projecting the economic indicators of the representative vessel’s profit and loss account over the period 2022–2035, under the assumption that no changes occur in the procurement of fish boxes. Alternative scenarios involved the introduction of “eco” boxes, specifically type C or D depending on the fishery (with type D considered only for longliners, HOK). For purse seiners and longliners, the adoption of a washing machine was also simulated, either at the individual vessel level (purse seiners and pelagic trawlers) or collectively (longliners). The latter option reflects the organizational setting of Eastern Sicilian coast, where a Producers’ Organization (PO) is active and could realistically support joint investments, thereby generating economies of scale in the purchase and use of boxes and washing equipment. For trawlers (DTS), an additional scenario was developed to test whether the introduction of eco-friendly boxes with traceability functions could be leveraged to increase the market value of landings through sustainability-oriented labelling strategies. The assumptions behind this scenario are based on literature exploring consumers’ Willingness To Pay (WTP) for sustainable seafood (Breidert et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2011; Onofri et al., 2018; Zander and Feucht, 2019; Zander et al., 2021). Indeed, while no studies currently assess WTP for products transported with environmentally friendlier packaging, results from recent studies highlight that Italian consumers are generally sensitive to sustainability concerns, with positive WTP estimates ranging between 14% (Onofri et al., 2018) and up to 17% (up to 43% for the most sensitive consumers) (Zander and Feucht, 2019). More recent findings confirm that sustainable packaging has become a significant determinant of purchasing behavior: 73% of European consumers are unwilling to switch to cheaper, less sustainable alternatives, and 82% are willing to pay a premium of up to 29% (Trivium Packaging, 2023). On this basis, the scenarios reported in Table 4 were defined and simulated.

Table 4

| Scenario no. | Scenario description | Fleet segments |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 0 | Baseline (Status Quo). Continued use of expanded polystyrene (EPS) or wood boxes. | All segments |

| Scenario 1 | Replacement with polypropylene (PP) boxes equipped with traceability “chip” (without lid), purchased individually by vessel. | DTS; HOK |

| Scenario 1_bis | Same as Scenario 1, with an additional price premium on catches due to potential valorization of traceability (RFDI) and sustainability attributes (eco-labelling). | DTS |

| Scenario 2 | Replacement with PP boxes with traceability “chip” (without lid), including individual vessel-level purchase of boxes and washing machines (for fleets with high daily box turnover). | PS; TM |

| Scenario 2_bis | Same as Scenario 2, with an additional price premium on catches due to potential valorization of traceability (RFDI) and sustainability attributes (eco-labelling). | PS; TM |

| Scenario 3 | Replacement with PP boxes with traceability “chip” (without lid), with collective purchase of boxes and washing machines at fleet-segment level (only HOK fleets organized in POs). | HOK |

Description of simulated scenarios for the adoption of polypropylene (PP) traceability boxes.

The economic modelling simulated the adoption of eco-sustainable (PP) fish boxes by applying an approach adapted from existing Mediterranean fisheries. Specifically, it represents an adaptation of the methodology adopted by the STECF for the projections included in the Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (AER) (Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF), 2020), itself based on the bio-economic models BEMTOOL (Lembo et al., 2012; Accadia et al., 2013) and MEFISTO (Lleonart et al., 1999). Input data covered revenues, operating costs, labor, and capital, with particular attention to variable costs such as fuel, ice, and boxes. The model relied on a set of key assumptions, including constant fishing effort across the simulation period, stable market demand, and gradual diffusion of polypropylene (PP) boxes as replacements for expanded polystyrene (EPS). It was further assumed that PP boxes would have a significantly longer lifespan, lower replacement frequency, compared to EPS, thereby enhancing both economic returns and environmental performance. This framework enabled the assessment of economic sustainability and the potential benefits of replacing EPS with reusable PP boxes over time.

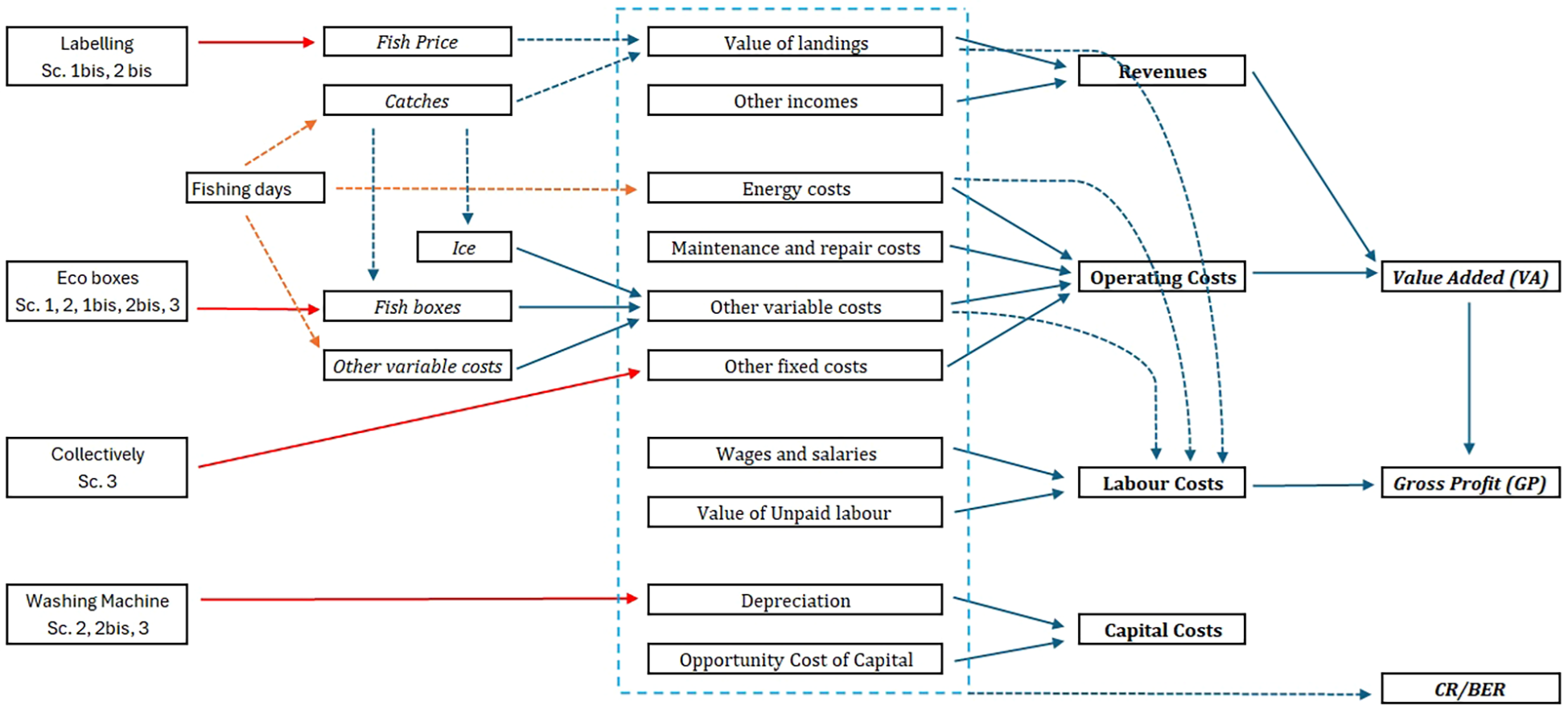

As outlined above, the alternative scenarios are characterized by the activation of four distinct modalities: the introduction of eco-boxes; the adoption of a washing machine system - implemented either at the individual vessel level or collectively; and the deployment of labelling strategies. A schematic diagram of the modelling framework, including the direct effects of these modalities on the model variables, is provided in the flow chart reported in Figure 1.

The introduction of eco-boxes across all alternative scenarios affects both the number of fish boxes used and their associated costs, which are accounted for under “other variable costs” in the income statement of the fisheries sector (see Table 1 in the Supplementary Material). The adoption of the washing machine, under Scenarios 2, 2bis, and 3, influences depreciation costs, as its purchase price (61,000 euros, including installation) is assumed to be depreciated over an eight-year period (7,625 euros per year). When the washing machine is acquired collectively under Scenario 3, however, the share attributed to each vessel, given by the annual cost divided by the number of vessels, is treated as an annual fixed cost and allocated to the corresponding cost category within the model. Finally, the labelling strategy is expected to affect the average fish price, generating a 15% increase in the value of landings.

The details of the internal relationships among the cost and revenue components of the modelling framework, as well as the equations employed to compute the economic performance indicators, are described in the Supplementary material/Annex II.

Annual values of the economic performance indicators, VA and GP, estimated for the period 2022–2035, were discounted using the most recent real interest rate available, namely the 2022 value. The sum of the discounted values was then used to compare the different scenarios. The discount rate for 2022, obtained from the 2023 Annual Economic Report (AER) of the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF, 2023), was –5.10%. This negative value reflects the high inflation recorded in that year relative to the nominal interest rate of Italian ten-year government bonds. To address the uncertainty inherent in selecting an appropriate discount rate, additional analyses were conducted using positive discount rates (1%, 3%, and 5%), which confirmed that the results of the assessment remain broadly consistent. Projections were developed for a representative “average vessel” over the period 2022–2035 under different scenarios, estimating key indicators such as the Value Added (VA) and the Gross Profit (GP) and the Current Revenues to Break-Even Revenues ratio (CR/BER) applied in the key literature for the sector (STECF, 2021). The CR/BER ratio measures the economic capacity required to remain in business. A CR/BER ≥ 1 indicates profitability and potential under-capitalization. A CR/BER slightly below 1 (0.9–1) suggests an acceptable but non-profitable condition, with possible over-capitalization. A CR/BER far below 1 is a signal of insufficient profitability, while negative values imply that even variable costs exceed current revenues. Details on specific assumptions are provided in Supplementary material/Annex II while Table 5 reports the main assumptions related to the use of PP boxes.

Table 5

| Parameter | Assumption | Justification/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Unit cost (purchase price) | €6–7 per box (type C, 6–7 kg capacity); €10–12 per box (type D, 24–25 kg capacity) | Market survey and supplier quotations (2022) |

| Average lifespan | 8–13 years | Based on durability tests and stakeholder feedback (existing fleets using PP boxes) |

| Reuse rate | 200–250 cycles per box before replacement | Manufacturer specifications and industry practice |

| Washing cost | €0.05–0.08 per box per cycle (water, detergent, energy) | Estimated from cooperative washing facilities in Italian ports |

| Washing infrastructure | Shared facilities for >20 vessels; individual washing units for smaller fleets | Interviews with stakeholders; economies of scale considered |

| Logistics (collection/return) | Managed at cooperative/auction level, negligible incremental cost | Reported by ports already using PP boxes |

| Loss rate (breakage, loss at sea) | 3–5% annually | Based supplier data |

| Residual value (end-of-life) | €0.50–1.00 per box (recycling credit) | Recycling industry quotations |

| Traceability option (RFID) | Additional €1.50 per box; useful life aligned with box | Supplier estimate; included in Scenario 1-bis and 2-bis |

Parameters and assumptions for the use of polypropylene (PP) boxes in the simulation model.

2.3 SWOT analysis

Complementary qualitative insights were collected from interviews with stakeholders in ports where PP boxes are already in use. The SWOT analysis identified strengths, weaknesses (inherent to the system) as well as opportunities and threats (arising from the external environment) associated with PP boxes adoption across the supply chain.

PP boxes, in particular type C, are currently employed in both Adriatic and Tyrrhenian ports and by vessels active on a variety of fishing techniques. To ensure relevance for the present study, only operators engaged in fisheries comparable to those under investigation were selected, while small-scale fisheries were excluded. In fact, both the demand for boxes and their distribution through the supply chain differ considerably between small-scale and large-scale fishing.

A structured set of questions was designed to capture operators’ perceptions regarding internal factors (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (opportunities and threats).

Interviews were conducted in three ports: two vessel owners (trawl fisheries) were interviewed - one operating in Santa Maria di Castellabate (Salerno, Campania region) and one in Mola di Bari (Bari, Apulia region). In addition, two experts who have monitored the use of eco-boxes in the area, and who also acted as key consultants in obtaining the PDO designation for the “colatura di alici” of Cetara, provided insights regarding the application of PP boxes in purse seine fisheries in Cetara (Salerno, Campania region).

The SWOT analysis was developed from qualitative field notes collected during semi-structured interviews (n = 4) across the three sites. As full interview transcripts were not available, a qualitative weighting approach was applied based on the conceptual prominence of themes recorded in the notes. Each SWOT point was first assigned an initial weight based on its perceived importance and then distributed among individual items according to their relative emphasis. To enhance representativeness, each item was linked to the locality where it emerged, and the recurrence of similar themes across sites was used as a proxy for cross-context relevance. Recurrent items were assigned proportionally higher weights, while unique or site-specific ones received lower weights. All weights were normalized to 100% for comparability. The detailed questionnaire is available in the Supplementary material/Annex III.

3 Results

3.1 Results from simulations

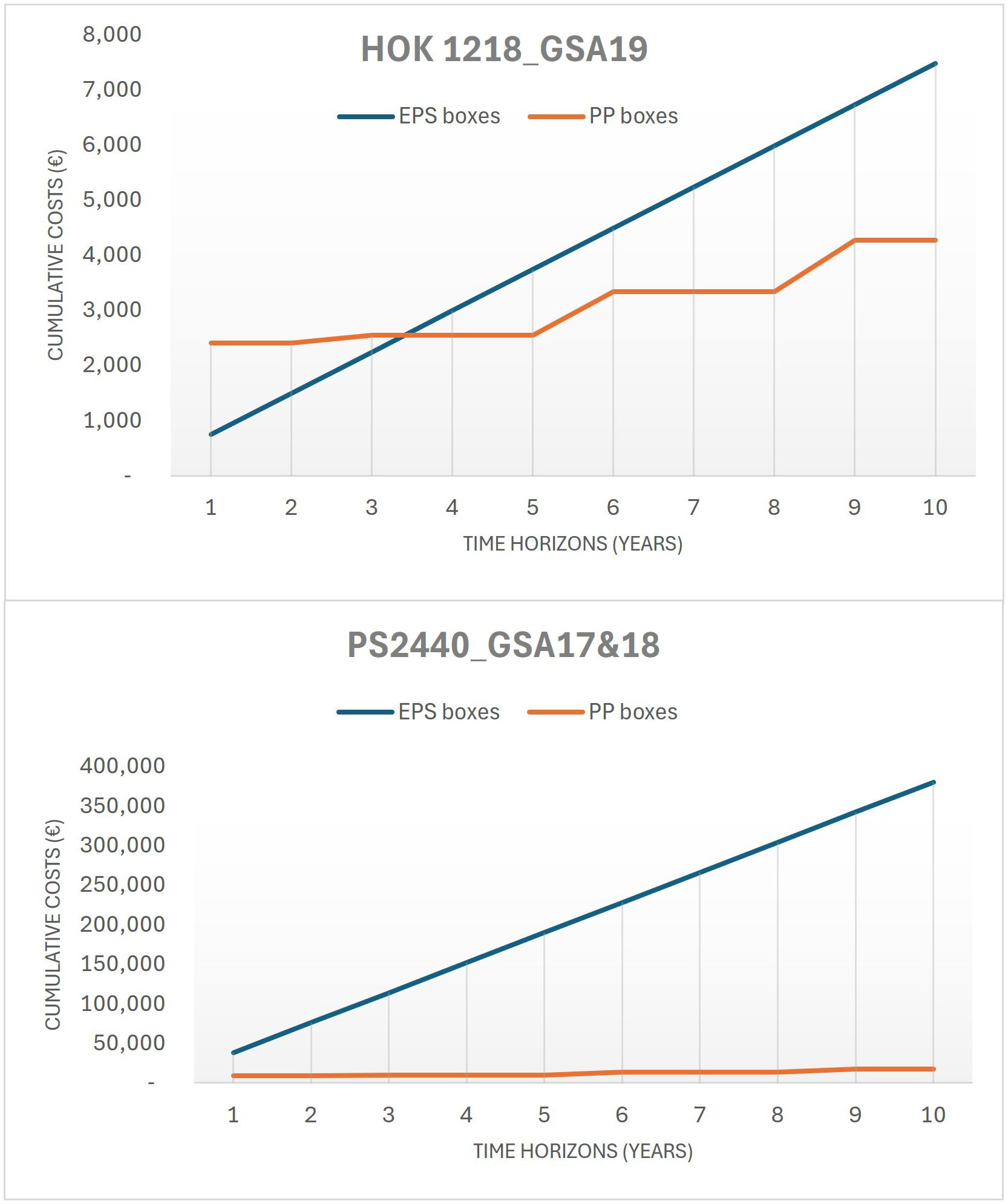

The results indicate that, over a ten-year period, cumulative costs diverge when comparing the use of PP and EPS fish boxes. For low-use fishing vessels (e.g., longliners), EPS boxes present lower initial purchase costs but rapidly accumulate replacement and disposal expenses. Conversely, although PP boxes require higher upfront investment, their cumulative costs increase at a slower rate. The case of HOK1218 shows that the cost curves intersect between the third and fourth year, marking the break-even point. By the tenth year, PP boxes yield substantial cost savings compared to EPS (Figure 1). For high-use fishing vessels (e.g., pelagic fisheries), economic advantages emerge from the first year. The case of PS2440 illustrates that the cost curves never intersect, with PP boxes consistently generating much lower cumulative costs than EPS and an expanding cost differential over the ten-year horizon (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Modelling framework structure focused on the impacts of scenarios on economic variables.

Figure 2

Comparative life-cycle cost of EPS vs PP boxes (cumulative costs, 10-year horizon for selected fleet segments).

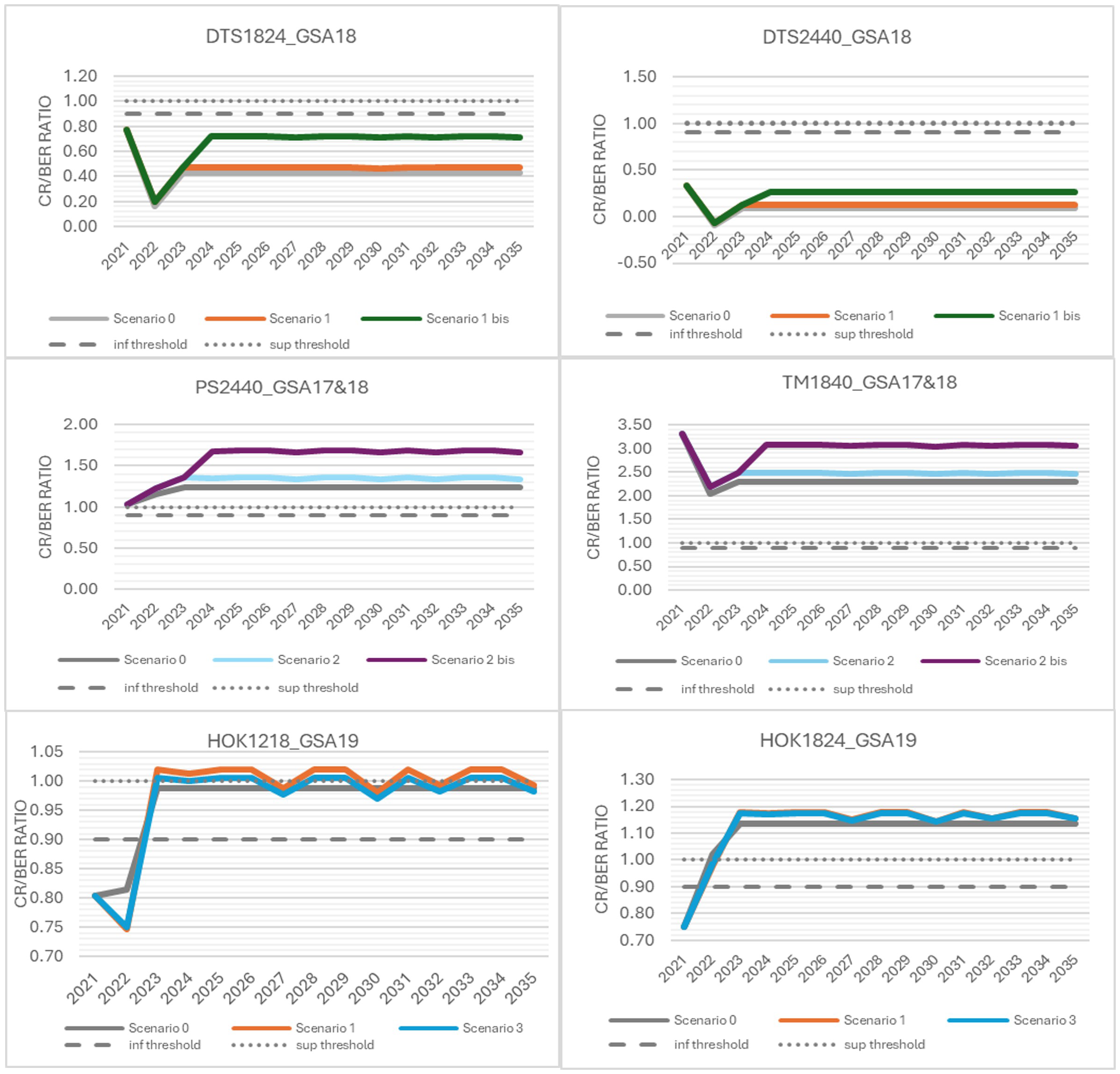

Profitability projections, expressed in terms of CR/BER ratio, indicate that under the status quo scenario, trawlers approach but do not consistently maintain profitability thresholds. Scenario 1 shows moderate improvements due to cost savings, while Scenario 1-bis demonstrates the highest profitability gains, suggesting that consumer-driven valorization mechanisms can significantly enhance long-term viability (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3

CR/BER evolution across scenarios and fleet segments (2021–2035).

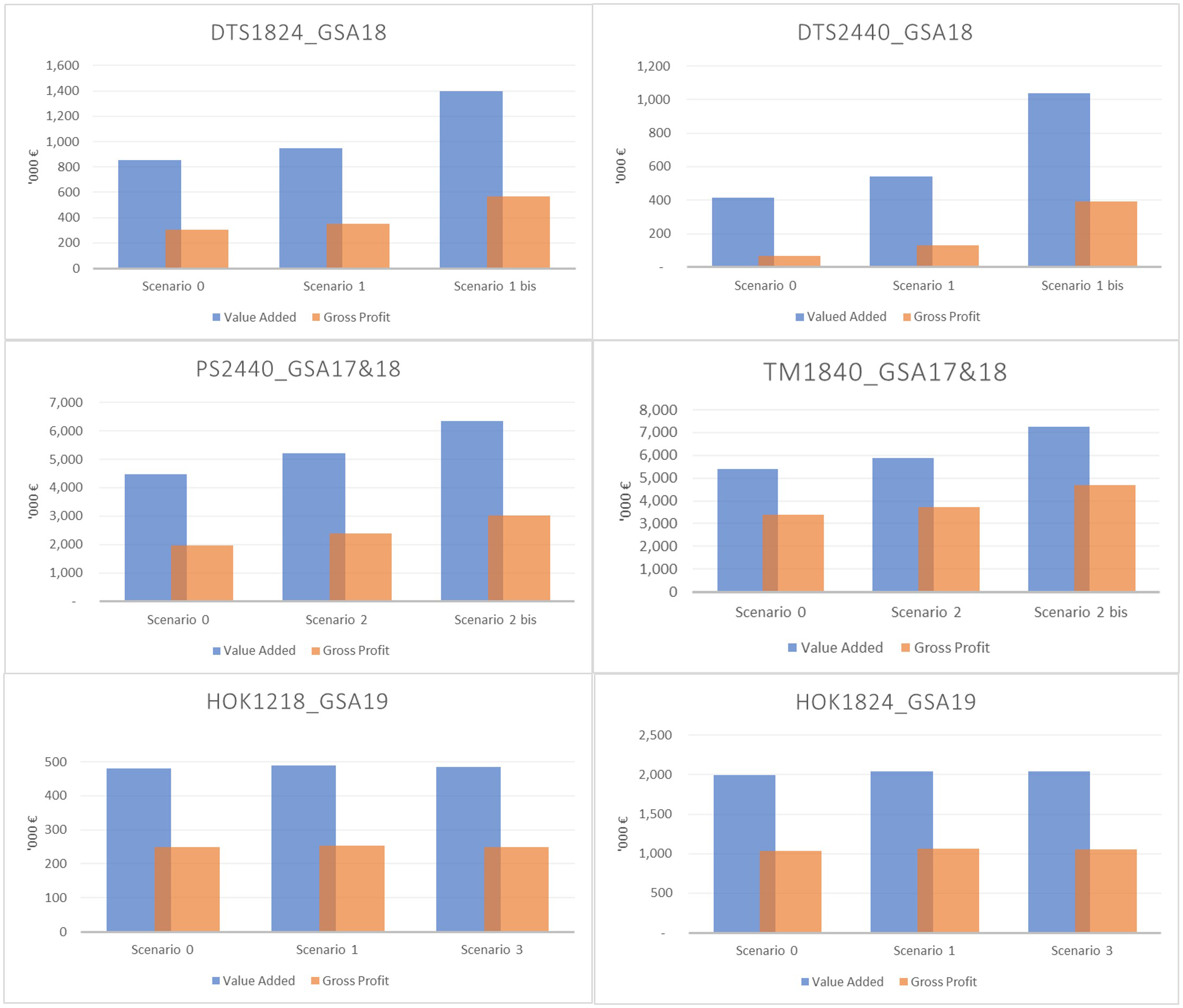

Figure 4

Discounted value of VA and GP across scenarios and fleet segments.

Clear benefits are observed in terms of Value Added (VA) and Gross Profit (GP) over the long term, based on the discounted projections to 2035. Across all case studies, improvements are evident relative to the Status Quo, although with varying degrees of intensity. Particularly positive variations are recorded for trawling (DTS) and purse seine (PS) fisheries, with increases never below +21% in scenarios simulating higher market prices for landings – Figures 3, 4. More moderate, though still positive, variations (ranging between +1% and +3%) are observed in the case studies of longline fisheries (HOK) in Eastern Sicily.

The simulation results reveal distinct profitability trends across fishing techniques when transitioning from traditional boxes (EPS or wood) to polypropylene (PP) eco-boxes. A summary of the results by fishing technique is provided below:

-

DTS 18–24 m and >24 m: under Scenario 1 (PP box adoption), both vessel classes show moderate gains in gross profit. However, Scenario 1-bis, which includes valorization through traceability and eco-labeling, yields substantial improvements—up to +87% for DTS1824 and +490% for DTS2440 compared to the baseline. This suggests that market-driven incentives significantly enhance economic viability for trawling fleets.

-

PS2440: these vessels demonstrate strong profitability even under the baseline scenario. The adoption of PP boxes (Scenario 2) increases gross profit by +21%, while Scenario 2-bis, which includes price premiums, boosts it by +54%. The high turnover of boxes and centralized washing infrastructure make this segment particularly well-suited for eco-box integration.

-

TM1840: this segment shows the highest absolute gross profit values across all scenarios. Scenario 2-bis leads to an increase of +35% over the baseline, confirming that fleets with large landing volumes and frequent box usage benefit most from reusable packaging systems.

-

HOK1218 and HOK1824: profitability gains are more modest. Scenario 1 and Scenario 3 (collective investment) yield improvements of +2% to +3%. These fleets, characterized by lower box turnover and higher unit costs for wooden boxes, reach break-even later but still benefit from cost savings and improved hygiene over time.

The comparative analysis of fishing techniques reveals that high-volume fleets, such as purse seiners (PS) and pelagic pair trawlers (TM), experience the most immediate and substantial economic advantages following the adoption of polypropylene (PP) boxes. These benefits are particularly pronounced when supported by traceability systems and eco-labeling strategies, which enhance product value and market appeal. Trawlers also show positive economic outcomes, although the extent of these gains is influenced by vessel size, with larger units generally achieving more significant improvements. In contrast, longliners face structural limitations due to lower box turnover and higher initial costs. For these fleets, meaningful profitability gains are contingent upon the implementation of collective investment models, which help distribute costs and optimize resource use across operators. This differentiation underscores the need for tailored policy and financial mechanisms that reflect the operational characteristics of each fleet segment.

3.2 SWOT findings

The adoption of eco-sustainable boxes in Italian fisheries remains largely pilot-scale or localized, with notable initiatives distributing several hundred to a few thousand boxes. An example is the initiative “BlueFishers” which distributed over 2,300 PP boxes to 70 fishers/58 vessels in Viareggio, Tuscany. Or, where, a regional project funded by the Campania Region providing 500 reusable polypropylene boxes to local fishermen in Cetara (Amalfi Coast). Or the experience in San Benedetto del Tronto, an Adriatic marineria which adopted PP boxes as part of an ecosustainability transition, thanks to a financed project by the regional authorities that awarded €56,000 under a fisheries and aquaculture fund to promote sustainable practices in the local fishing sector. However, beside these initiative and adoption of PP boxes on single operator basis, the full-scale adoption in Italy is still limited.

According to the SWOT analysis, the adoption of eco-sustainable boxes in Italian fisheries demonstrates clear benefits in terms of durability, hygiene, and environmental sustainability, but also highlights operational and financial challenges. In Santa Maria di Castellabate (trawling), eco-boxes have been used since 2023, mainly for direct sales during the summer (60 - 70% of the catch), receiving positive consumer feedback. However, local fry shops prefer polystyrene for convenience, and in winter approximately 80% of the catch is sold to wholesale markets using disposable polystyrene due to the absence of a functional return system. The operator suggested involving retailers in the purchase of eco-boxes to establish a local reuse circuit. In Mola di Bari (trawling), the operator, with three years of experience using eco-boxes, successfully supplied local fishmongers (up to 100 boxes per landing), but reverted to polystyrene after sales shifted to wholesalers, who supply boxes directly and deduct costs from invoices. A deposit system was proposed to incentivize box returns. In Cetara (purse seining), experts emphasized the environmental, quality, economic, and logistical benefits of eco-boxes, yet adoption remains limited, hindered by the lack of legal restrictions on polystyrene and insufficient systemic uptake. RFID-enabled traceability was identified as a promising opportunity, feasible only at larger scales.

The SWOT analysis applied in the study has also tried to quantify observations across the three locations (see the methodological section for details). Looking at the respondents perceived importance of the SWOT macro-categories, internal factors account for around 77% (Strengths 39%, Weaknesses 38%) while external ones for the remainder 33% (Opportunities 13%, and Threats 10%). This pattern likely reflects that actors are more able to identify strengths and weaknesses, which are internal factors of the PP eco-boxes system, grounded in current practices and tangible experience, whereas opportunities and threats concern external factors impacting future scenarios and are therefore more uncertain. Among strengths, “Durable and reusable” (23%) and “Hygienic and HACCP compliant” (10%) were most prominent, directly supporting food safety, circular economy objectives, and sustainability. In contrast, weaknesses such as “Logistic complexity” (13%) and “Need for washing infrastructure” (12%) outweigh threats, underscoring that practical and cost-related constraints constitute the main barriers, while market and coordination challenges are comparatively less significant.

Overall, these findings provide a quantitative and qualitative overview of the key factors influencing adoption, showing that eco-box uptake is primarily driven by durability, hygiene, and environmental benefits, whereas operational and financial considerations represent the main limitations.

A synthetical overview of the SWOT results is reported in Table 6:

Table 6

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Durable and reusable (23%) | High upfront investment (10%) |

| Hygienic and HACCP compliant (10%) | Need for washing infrastructure (12%) |

| Reduced plastic waste (3%) | Logistic complexity (13%) |

| Economic and space savings (1%) | Dependence on consumer compliance (2%) |

| Traceability/chip integration (1%) | Seasonal variability in use (1%) |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| Valorization via eco-labeling (2%) | Markt resistance (4%) |

| Consumer WTP for sustainability (2%) | Coordination challenges (3%) |

| Scalability across fleets (6%) | Dependence on supply chain (1%) |

| Local initiatives/incentive schemes (2%) | Lack of standardization (1%) |

| Potential for policy support (1%) | Intermediaries/wholesalers practices favoring EPS (1%) |

SWOT results for fish eco-boxes adoption.

4 Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the replacement of expanded polystyrene (EPS) with polypropylene (PP) boxes in the Italian fishing sector generates both economic and environmental benefits over the long term. The life-cycle cost simulations show that, despite higher initial investment costs, PP boxes become more advantageous from the third year onwards due to their durability and reusability. This finding is consistent with previous analyses of circular economy practices in the fisheries sector, which underline the role of durable packaging solutions in reducing operating costs and mitigating environmental externalities (European Commission, 2020; Baltrocchi et al., 2025) as well with finding of other previous research that has demonstrated the efficacy of reusable plastic containers in outperforming single-use packaging under conditions of high utilization and effective reverse and washing logistics (Ceballos-Santos et al., 2024; Almeida et al., 2022).

From an operational perspective, the shift from disposable to reusable boxes requires the establishment of efficient logistics systems. Unlike EPS, which is discarded after a single use, PP boxes must circulate across the distribution chain and return to a defined base for washing and reuse. This implies the creation of dedicated collection and management centers, capable of handling procurement, sanitization, recovery and redistribution. As highlighted by field evidence from fishing communities already experimenting with eco-boxes, such systems need time to become effective and require strong coordination among stakeholders. Producer organizations (POs) are particularly well-positioned to facilitate this transition. By aggregating supply and centralizing logistics, POs can exploit economies of scale, reducing per-unit costs and improving access to the high initial investment needed, especially relevant when considering the complete system integrated with the washing infrastructure. Moreover, aggregation plays a critical role in enhancing the valorization of catches in a sector undergoing structural downsizing due to landing restrictions and increased fuel and energy costs (Malvarosa, 2022). Similar conclusions are reported in studies of cooperative management in fisheries, where collective solutions have been shown to mitigate individual costs and enhance bargaining power (FAO, 2012; Malvarosa et al., 2024).

Another significant dimension is product valorization through traceability, considered under one of the simulated scenarios of the present study. The integration of RFID chips in PP boxes enables digital traceability along the supply chain, responding to consumer demand for sustainable and transparent seafood products. Previous research underscores the importance of labeling policies that guarantee traceability, since the product’s origin significantly influences consumer purchasing decisions (Mauracher et al., 2013). Specifically, consumers’ willingness to buy eco-labeled fish strongly relies on clear and transparent information about the product’s source, highlighting the critical role of traceability for building trust (Brécard et al., 2012).

The consideration of the traceability scenario is aligned with broader evidence showing that RFID-based traceability systems improve supply chain efficiency, customer retention, and product differentiation, even if the costs tend to be borne by processors while the benefits accrue downstream (Mai et al., 2010). Global adoption of RFID in fisheries supply chain management further highlights its dual role in ensuring food safety and promoting sustainability, particularly when combined with renewable energy and recyclable materials (Rahman et al., 2021). This study highlights that RFID technology enhances traceability, safety, and sustainability in the fishery supply chain, but its adoption faces challenges such as high costs and system integration issues. Effective implementation requires an integrated approach to ensure reliability and consumer trust. Recent studies conceptualize traceability not only as a record-keeping tool but also as a form of informational governance, fostering transparency, accountability, and sustainable market practices, though equity and inclusion challenges for small-scale producers remain (Kadfak et al., 2025).

The findings of the present analysis are consistent with previous research demonstrating the capacity of reusable plastic containers to outperform single-use packaging when utilization is high and reverse logistics and washing operations are effectively implemented (Ceballos-Santos et al., 2024; Almeida et al., 2022). Notably, these studies also emphasize that the initial cost of fish boxes is an inadequate indicator of the total cost of ownership when replacement rates, breakage, and end-of-life management are considered. Employing a life-cycle cost perspective on Italian fisheries, the present analysis plots cumulative – as opposed to annual – costs to inform investment decisions and quantifies an economic benefit for higher use vessel (e.g. pelagic fisheries) since the first year or a break-even point, for lower use vessels (e.g. longliners), of approximately three years under assumptions regarding daily box demand, rotation, and washing tools. Future studies should aim to quantify real loss and breakage on a port-by-port basis, while also capturing the costs of washing (water, energy, labor). Moreover, these future investigations should encompass the development of a model to address return logistics (e.g. back-hauling, pooling, deposits), alongside testing sensitivity to discount rate, inflation and energy mix.

While the shift from single-use EPS to reusable PP boxes represents a significant improvement in waste prevention and circularity, it is important to acknowledge that polypropylene production entails higher energy demand and associated carbon emissions per unit of material compared to EPS. However, life-cycle studies (WWF Italia, 2024) indicate that these impacts are largely offset over multiple reuse cycles, particularly when efficient washing and logistics systems are in place. The overall life-cycle footprint of PP decreases sharply after the first few uses, making its environmental performance superior to that of EPS when considered on a functional basis (per use cycle). Nevertheless, such results are mainly derived from medium-to-large fishing fleets or cooperatives capable of managing centralized washing and pooling systems. The direct transferability of these findings to small-scale fisheries remains uncertain, as operational constraints, infrastructure gaps, and limited access to collective investment may reduce the achievable number of reuse cycles and thus the net environmental gains.

The findings of the paper highlight that the adoption of PP boxes is particularly advantageous for purse seiners and trawlers, where box turnover is high, while longliners benefit more from collective investment strategies. However, adoption barriers remain significant. The main constraints identified are high upfront investment costs, the absence of adequate washing infrastructure, and the need to modify current logistic practices. These challenges are not unique to Italy; similar barriers have been reported in other European contexts attempting to replace EPS with reusable alternatives (European Commission, 2020). To overcome these obstacles, public support is essential. Funding opportunities from the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) and its successor, the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF), have already been mobilized in regions such as Marche and Campania, where specific calls have supported projects for replacing EPS boxes with reusable alternatives.

5 Conclusions

Eco-sustainable PP boxes require higher upfront investment but yield long-term gains in profitability, compliance, and environmental performance. By reducing EPS waste, microplastic leakage, and ancillary costs such as ice use, reusable PP boxes offer both operational and ecological advantages. Their adoption should be viewed as a systemic innovation, not merely a technological replacement. Success depends on coordinated logistics, cooperative management, consumer engagement, and consistent policy support. Under these conditions, eco-boxes can strengthen environmental protection, economic efficiency, and social sustainability across Mediterranean fisheries.

Statements

Author’s note

FEDERPESCA – Federazione Nazionale delle Imprese di Pesca has authorized the use of the material contained in the report edited by Nisea for Federpesca: The Nisea Press 2023–46 p. ISBN 978-88-941553-6–5 Copyright © 2023 Federpesca (available at https://www.nisea.eu/dir/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/FP_Analisi-Cassette-Eco-Sostenibili.pdf).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision. PA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft. MC: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. CP: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. RS: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The financial support to this study has been provided by FEDERPESCA – Federazione Nazionale delle Imprese di Pesca for the research project “Analisi costi benefici dell’utilizzo di cassette eco-sostenibili (riutilizzabili e riciclabili) per il trasporto del pescato.”.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the fishers and their representatives, producers’ organizations, and the DuWo Srl representative for providing essential information on the PP boxes. Sincere thanks are also extended to the audience of the 43rd CIESM Congress for their constructive feedback on the presentation “Cost-Benefit Analysis of the use of eco (reusable and recyclable) boxes for the transport of fish” by Malvarosa et al. (2024). Finally, authors sincerely thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback, which greatly contributed to enhancing this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT for some translations.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1704176/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Accadia P. Bitetto I. Facchini M. T. Gambino M. Kavadas S. Lembo G. et al . (2013). BEMTOOL Deliverable D10: BEMTOOL Final Report (Tender DG-MARE 2009/05/Lot1, MAREA Framework Contract). European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE), Brussels.

2

Almeida C. Loubet P. da Costa T. P. Quinteiro P. Laso J. Baptista de Sousa D. et al . (2022). Packaging environmental impact on seafood supply chains: A review of life cycle assessment studies. J. Ind. Ecol.26, 1961–1978. doi: 10.1111/jiec.13189

3

Baltrocchi G. Pellegrini M. Rossi F. (2025). Improving environmental sustainability of food-contact polypropylene packaging production. Packaging7, 70. doi: 10.3390/packaging7030070

4

Brécard D. Hlaimi B. Lucas S. Perraudeau Y. Salladarré F. (2012). Determinants of demand for green products: An application to eco-label demand for fish in Europe. Ecol. Econ69, 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.07.017

5

Breidert C. Hahsler M. Reutterer T. (2006). A review of methods for measuring willingness-to-pay. Innov Marketi2, 8–32.

6

Ceballos-Santos S. Baptista de Sousa D. González García P. Laso J. Margallo M. Aldaco R. (2024). Exploring the environmental impacts of plastic packaging: A comprehensive life cycle analysis for seafood distribution crates. Sci. Total Environ.951, 175452. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175452

7

Cózar A. Sanz-Martín M. Martí E. González-Gordillo J. I. Ubeda B. Gálvez J.Á. et al . (2015). Plastic accumulation in the Mediterranean Sea. PloS One10, e0121762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121762

8

European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (n.d.) (2025). Overcoming the challenges to recycle EPS fish boxes into new food-grade packaging ( European Commission). Available online at: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/good-practices/overcoming-challenges-recycle-eps-fish-boxes-new-food-grade-packaging (Accessed December 15, 2023).

9

European Commission (2020). A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe (Brussels: European Commission).

10

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (2020). Scientific opinion on the safety assessment of the process used to recycle polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) food contact materials. EFSA J.18, 6204. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6204

11

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . (2012). Cooperatives in small-scale fisheries: Enabling successes through community empowerment (Issue Brief). FAO. Available at: https://www.fao.org/4/ap408e/ap408e.pdf (Accessed July, 2025).

12

GreenReport (2021). Polystyrene and marine litter: A growing environmental concern. Available online at: https://www.greenreport.it (Accessed December 15, 2023).

13

Hansen A.Å. Svanes E. Hanssen O. J. Void Mie Rotabakk B. T. (2012). “ Advances in bulk packaging for the transport of fresh fish,” in Advances in Meat, Poultry and Seafood Packaging. Ed. KerryJ. P. (Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition), 248–260. doi: 10.1533/9780857095718.2.248

14

Hilmarsdóttir G. S. Margeirsson B. Spierling S. Ögmundarson Ó. (2024). Environmental impacts of different single-use and multi-use packaging systems for fresh fish export. Journal of Cleaner Production447, 141427. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141427

15

Kadfak A. Hanh T. T. H. Widengård M. (2025). The impact of state-led traceability on fisheries sustainability. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 27 (2), 95–107. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2024.2422825

16

Lembo G. Accadia P. Bitetto I. Facchini M. T. Melià P. Rossetto M. et al . (2012). BEMTOOL Deliverable D2: A comprehensive description of the new bio-economic model for Mediterranean fisheries (Tender DG-MARE 2009/05/Lot1, MAREA Framework Contract). European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE), Brussels.

17

Lleonart J. Maynou F. Franquesa R. (1999). A bioeconomic model for Mediterranean fisheries. Fish Econ Newslett.48, 1–16.

18

Mai N. Bogason S. G. Arason S. Árnason S. V. Matthíasson T. G. (2010). Benefits of traceability in fish supply chains: Case studies. Br. Food J.112, 976–1002. doi: 10.1108/00070701011074354

19

Malvarosa L. (2022). La catena del valore e il consumo consapevole di prodotti ittici sostenibili come strategie per fronteggiare la crisi del settore ittico ( Sintesi dell’intervento al Blue Sea Land). NISEA Note. http://www.nisea.eu/dir/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Nisea-Note-2021_1_BlueSealand_2.pdf.

20

Malvarosa L. Accadia P. Cozzolino M. Gambino M. Sabatella R. F. (2024). Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit. Available online at: https://ciesm.org/Congresses/Palermo/CIESM_Congress_Volume_43_UTD_HQ.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2023).

21

Malvarosa L. Gambino M. Cozzolino M. . (2024). Strengths, weaknesses, and upgrading strategies of the pink shrimp fishery value chain in Southern Adriatic [Presentation]. Antalya, Türkiye: FAO GFCM Fish Forum 2024. Available at: https://www.nisea.eu/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Malvarosa-Fish-Forum-2024.pdf (Accessed July, 2025).

22

Marevivo (2025). BlueFishers: Closing the loop of polystyrene fish boxes in the fishing industry ( Marevivo Onlus). Available online at: https://marevivo.it/en/activities/pollution/bluefishers/ (Accessed December 15, 2023).

23

Mauracher C. Tempesta T. Vecchiato D. (2013). Consumer preferences regarding the introduction of new organic products: The case of Mediterranean sea bass in Italy. Appetite63, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.12.010

24

Miller K. M. Hofstetter R. Krohmer H. Zhang J. Z. (2011). How should consumers’ willingness to pay be measured? An empirical comparison of state-of-the-art approaches. J. Marketi Res. 48 (1), 172–184. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.48.1.172

25

Myers M. (1981). Planning and Engineering Data: Fresh Fish Handling (FAO Fisheries Circular No. 735) (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

26

Onofri L. Accadia P. Ubeda P. Gutiérrez M. J. Sabatella E. Maynou F. (2018). On the economic nature of consumers’ willingness to pay for a selective and sustainable fishery: A comparative empirical study. Sci Marina82, 91–96. doi: 10.3989/scimar.04737.10A

27

Rahman L. F. Alam L. Marufuzzaman M. Sumaila U. R. (2021). Traceability of sustainability and safety in fishery supply chain management systems using radio frequency identification technology. Foods10, 2265. doi: 10.3390/foods10102265

28

Raugei M. Benveniste G. Ardente F. Mathieux F. (2022). Environmental sustainability of fishery product packaging: Insights from the NEPTUNUS project. Sustainability14, 3054. doi: 10.3390/su14053054

29

Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) (2023). The 2023 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF 23-07) Annex. Eds. PrellezoR.SabatellaE.VirtanenJ.Tardy MartorellM.GuillenJ. (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union). JRC135182. doi: 10.2760/423534

30

Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) (2020). The 2020Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF 20-06), EUR 28359 EN (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union). doi: 10.2760/500525,JRC123089

31

Trivium Packaging (2023).Buying Green Report 2023. Trivium Packaging.https://www.triviumpackaging.com

32

Turner A. (2020). The impacts of polystyrene microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Mar. pollut. Bull.161, 111729. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111729

33

WWF Italia (2024). Soluzioni di imballaggio innovative e sostenibili per ridurre la dispersione di plastica in mare: Analisi delle cassette per il pesce alternative al polistirolo vergine monouso (Roma: WWF Italia). Available online at: https://www.wwf.it (Accessed December 15, 2023).

34

Zander K. Daurès F. Feucht Y. Malvarosa L. Pirrone C. Le Gallic B. (2021). Consumer perspectives regarding coastal fisheries and product labelling in France and Italy. Fish Res.246, 106168. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2021.106168

35

Zander K. Feucht Y. (2019). Consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable seafood made in Europe. J. Int. Food Agribusiness Marketi30, 251–275. 10.1080/08974438.2017.1413611 (Accessed December 15, 2023).

Summary

Keywords

polystyrene, polypropylene, fish boxes, environmental benefits, economic viability, profitability

Citation

Malvarosa L, Accadia P, Cozzolino M, Paolucci C and Sabatella RF (2026) Can economic benefits foster sustainability? A preliminary study on the transition from polystyrene to polypropylene boxes in selected Italian fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1704176. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1704176

Received

12 September 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

29 November 2025

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ioannis A. Giantsis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Reviewed by

Dimitra Bobori, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Suvarna Devi, University of Kerala, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Malvarosa, Accadia, Cozzolino, Paolucci and Sabatella.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Loretta Malvarosa, malvarosa@nisea.eu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.