Abstract

Coastal sediment ecosystems function as dynamic interfaces for land-sea interactions, harboring highly complex microbial communities which support vital ecological functions. However, the mechanisms governing microbial diversity maintenance and cross-trophic community assembly at large spatial scales remain poorly explored. In this study, a high-throughput sequencing approach was employed to analyze the bacterial, fungal and protistan communities in surface sediments of the China Seas. As indicated by higher values across most indices, bacterial communities generally exhibited greater richness and alpha diversity compared to fungal and protistan communities. Beta diversity decomposition revealed that species turnover dominated community variations across all three trophic levels, with the highest contribution in bacteria. The neutral community model revealed that stochastic processes exerted a stronger influence on bacterial assembly relative to fungi and protists. Moreover, null model analyses demonstrated that bacterial communities were primarily structured by dispersal limitation, fungal communities by ecological drift, while protistan communities co-regulated by homogeneous selection and homogenizing dispersal. Furthermore, similar latitude-dependent patterns in the α- and β- diversity were observed in bacteria and protists, yet such patterns were distinct for fungi. Finally, based on the correlations between community variations with their assembly mechanisms, regional species pools exerted the strongest influence on bacterial β-diversity, whereas local assembly processes dominated fungal β-diversity. The present study elucidates the trophic-level-dependent assembly rules of coastal microbiomes, thereby establishing a mechanistic foundation for predicting ecosystem responses to global change and informing evidence-based conservation of coastal ecosystems.

1 Introduction

Coastal sediment ecosystems, as dynamic interfaces of land-sea interactions, host highly complex microbial communities that drive key biogeochemical processes (e.g., organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling) in coastal zones. Driven by freshwater input, tidal dynamics, and sediment transport, these regions develop steep environmental gradients (e.g., salinity clines, nutrient enrichment zones) that foster heterogeneous habitats for multitrophic coexistence (Barbier et al., 2011). However, these vulnerable interfaces are increasingly subjected to escalating pressures from compounded stressors: terrestrial pollutants, coastal development activities, and phenological shifts induced by climate change, collectively driving habitat fragmentation and biodiversity loss (Cloern et al., 2016). Particularly in estuarine zones with drastic hydrological fluctuations, spatiotemporal variations in physicochemical parameters not only reshape biogeographic patterns of species but also threaten critical ecosystem services through cascading effects (Lu et al., 2018). Elucidating the composition, assembly, and maintenance mechanisms of biotic communities in these regions has emerged as a frontier challenge in ecological research.

Coastal microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and protists, serve as fundamental pillars of material cycling and energy flow. Different microbial groups exhibit specialized ecological functions and habitat preferences (Fierer, 2017). Bacteria dominate organic matter mineralization and nutrient transformation, fungi regulate carbon pool dynamics through lignin decomposition, and protists act as keystone regulators of population balances within microbial food webs (Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Moran, 2015). The sensitivity of these microbial communities to environmental stressors positions them as “early-warning indicators” of ecosystem health (Lozupone and Knight, 2007; Wu et al., 2018). Consequently, deciphering the assembly mechanisms of multitrophic microorganisms not only advances biogeographic theory but also identifies strategic intervention targets for ecological restoration, thereby refining integrated coastal management frameworks.

The assembly mechanisms of microbial communities represent a central question in ecological research, shaped by the interplay of deterministic and stochastic processes (Nemergut et al., 2013). Their relative importance depends not only on the strength of selective forces and the rate of stochastic dispersal but also on the taxonomic identity and functional traits of microbial groups (Cottenie, 2005; Padial et al., 2014; Ragon et al., 2012). Deterministic processes are primarily driven by environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, salinity) and biotic interactions (e.g., competition, predation, symbiosis), which govern community composition, structure, and species fitness. Conversely, stochastic processes, including birth, death, dispersal, and ecological drift, introduce unpredictability into community assembly. Previous studies have demonstrated that variable selection predominantly shapes bacterial communities in estuarine systems, while stochastic drift governs protistan community assembly (Aguilar and Sommaruga, 2020; Cottenie, 2005; Padial et al., 2014; Ragon et al., 2012; Zhou and Ning, 2017). This reflects the heightened sensitivity of bacteria to environmental gradients and the inherently stochastic nature of protistan population dynamics. Nevertheless, systematic quantification remains lacking for microbial community assembly patterns across spatial scales, underlying assembly mechanisms, and their linkages to regional species pools.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding revolutionizes biodiversity assessment by enabling high-throughput, standardized detection of genetic traces from multitrophic organisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, protists) (Logares et al., 2012). This approach transcends the limitations of traditional culturing methods and facilitates simultaneous sequencing of multiple genetic markers (e.g., 16S rRNA, ITS, 18S rRNA), allowing quantitative dissection of deterministic processes (environmental filtering, resource competition) and stochastic processes (dispersal limitation, ecological drift) in community assembly (Wu et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2022b). Such technological innovation shifts biological monitoring from descriptive diversity profiling to mechanistic ecological analysis, providing molecular-scale insights for resilience assessment and adaptive management of coastal ecosystems.

Microbial communities play pivotal roles in sustaining material and energy fluxes in coastal ecosystems, where their multitrophic assembly mechanisms critically underpin functional stability (Zhao et al., 2022b). While previous studies have focused on single taxonomic groups or static diversity patterns (Breyer et al., 2022; Kraemer et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2018; Singer et al., 2021), they often fail to disentangle the compound effects of environmental filtering, dispersal limitation, and biotic interactions on community assembly, particularly lacking quantitative assessments of regional species pools and local community linkages. Leveraging high-throughput sequencing and phylogenetic ecological models, this study conducts an integrated multitrophic analysis of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities across China’s coastal gradients. By combining unweighted (UniFrac) and weighted (Weighted UniFrac) distance metrics, we quantify the impacts of regional species pools and abundance distributions on microbial β-diversity and phylogenetic structure. Furthermore, null model analyses dissect the relative contributions of deterministic (homogeneous/heterogeneous selection) and stochastic (dispersal limitation, drift) processes, elucidating latitude-dependent assembly mechanisms. Our findings not only unravel microbial-mediated ecological regulation in coastal environments but also enhance understanding of microbial adaptation to global change, offering a scientific foundation for evidence-based coastal ecosystem management.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and sampling

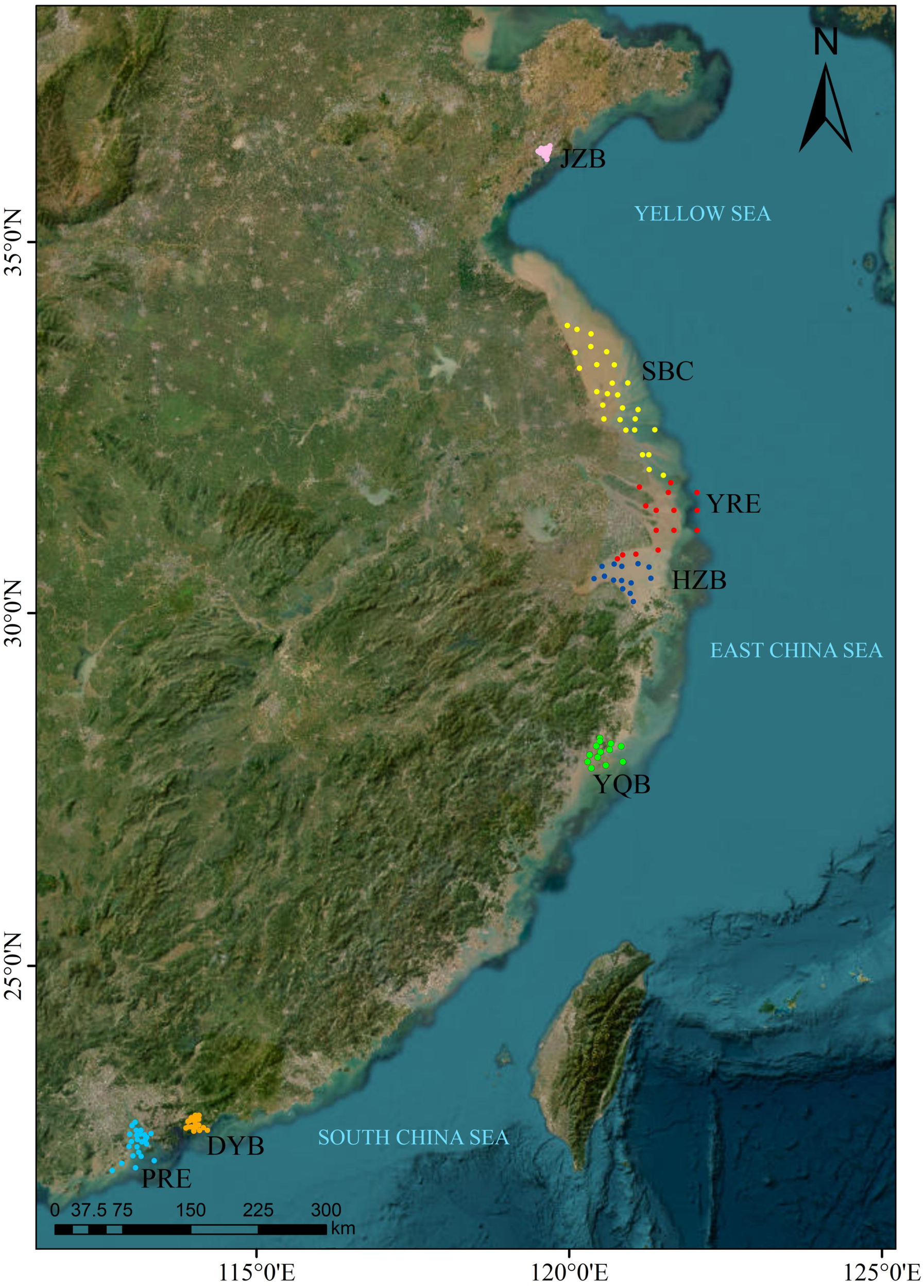

This study encompassed seven coastal and estuarine regions spanning from northern to southern China (Figure 1), including Jiaozhou Bay (JZB, n = 14), Subei Coast (SBC, n = 27), Yangtze River Estuary (YRE, n = 15), Hangzhou Bay (HZB, n = 14), Yueqing Bay (YQB, n = 13), Daya Bay (DYB, n = 18), and Pearl River Estuary (PRE, n = 24), totaling 125 sampling stations. Surface sediment samples were collected at each station in the summer of 2023 (July to August) using a stainless steel grab sampler (0.1 m2). Approximately 500 g of sediment from the top 5 cm was subsampled and immediately placed on ice for transport to the laboratory within 24 hours. All samples were stored at -80 °C until DNA extraction, which was completed within 24 hours of collection to minimize degradation.

Figure 1

Map of the study area in the coastal sediments of China, showing the sampling sites of seven coastal and estuarine regions. JZB, Jiaozhou Bay; SBC, Subei Coast; YRE, Yangtze River Estuary; HZB, Hangzhou Bay; YQB, Yueqing Bay; DYB, Daya Bay; PRE, Pearl River Estuary.

2.2 eDNA metabarcoding sequencing and data processing

DNA was extracted from sediment samples using the FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA integrity was verified via 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and purity was assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, USA). Samples with A260/A280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 were retained for downstream analyses. To investigate bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, the V3-V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA genes, the ITS1 region of fungal ITS genes, and the V9 region of eukaryotic 18S rRNA genes were amplified from microbial DNA using primer pairs 341F-806R (GCCTCCCTCGCGCCATCAGCAGTAGACGT and GCCTTGCCAGCCCGCTCAG; Zakrzewski et al., 2012), ITS1-ITS2 (TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG and GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC; Zhang et al., 2010), and 1380F-1510R (TCCCTGCCHTTTGTACACAC and CCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC; Stoeck et al., 2009), respectively. PCR were performed in 20 µL volumes containing 4 µL 5× FastPfu Buffer, 2 µL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.4 µL FastPfu polymerase, and 10 ng template DNA. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products from each sample were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified PCR products were quantified using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Invitrogen) and pooled in equimolar amounts. Amplicon libraries were constructed using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit from NEB (Massachusetts, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Library quality was evaluated using the QuantiFluor dsDNA System (Promega, USA) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 System (Agilent, USA). Finally, libraries were sequenced on the MGI-G99 platform at BIOZERON Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Paired-end reads were demultiplexed based on unique barcodes and subjected to quality filtering using the DADA2 package in R v4.2.2 (Callahan et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2024), with truncation at Q < 20 and removal of ambiguous bases. Overlapping paired reads were merged to reconstruct full-length sequences. Chimeric sequences were removed using the QIIME2 pipeline (Bokulich et al., 2018), and amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated. Taxonomic classification was performed against the SILVA v138.2 database (Glöckner et al., 2017) for bacteria, UNITE v8.3 (Nilsson et al., 2019) for fungi, and PR2 v4.12.0 for protists. Non-fungal ITS ASVs and protistan 18S ASVs assigned to metazoans, embryophytes, or non-target taxa were excluded. Singleton ASVs (total read count = 1 across all samples) were removed to mitigate sequencing artifacts. All the above operations were consistent with our previous research (Zhao et al., 2022a, 2022b).

2.3 Statistical analysis

α-diversity indices for bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, including Chao1, Shannon, Pielou’s evenness, and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (Fatih’s PD), were calculated using the “vegan” package (Oksanen et al., 2025). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to test for differences in α- and β-diversity between two communities. β-diversity distances were decomposed into species nestedness and turnover components via Betapart analysis using the “betapart” package (Baselga et al., 2025). Additionally, changes in community composition for bacteria, fungi, and protists were evaluated based on UniFrac and Weighted UniFrac distances using the “GUniFrac” package (Chen et al., 2023). All statistical analyses were performed in R software 4.2.2.

To analyze how regional species pools and species abundance distributions affect microbial communities, linear regression was used. It assessed the relationship between shared species counts and β-diversity distances between any two samples. UniFrac distance, focusing on species composition, helped determine local species pool impacts. Weighted UniFrac distance, which includes both composition and relative abundance, evaluated how species abundance distribution influences community assembly (Lozupone et al., 2011).

Neutral models were applied to explore the assembly mechanisms of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities (Stegen et al., 2013). First, the β-NTI between sample pairs was calculated. |β-NTI| > 2 indicates deterministic processes dominate community assembly, whereas |β-NTI| ≤ 2 suggests more influence from stochastic processes. Meanwhile, the Raup-Crick metric based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was used to classify communities based on five ecological processes: homogeneous selection, heterogeneous selection, homogeneous dispersal, dispersal limitation, and drift. Euclidean and geographic distances between sample pairs were computed using the “vegan” and “geosphere” packages, respectively (Hijmans, 2024; Oksanen et al., 2025). Linear regression analysis, based on Weighted UniFrac and UniFrac distances, compared bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities (Wu et al., 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Community diversity and composition

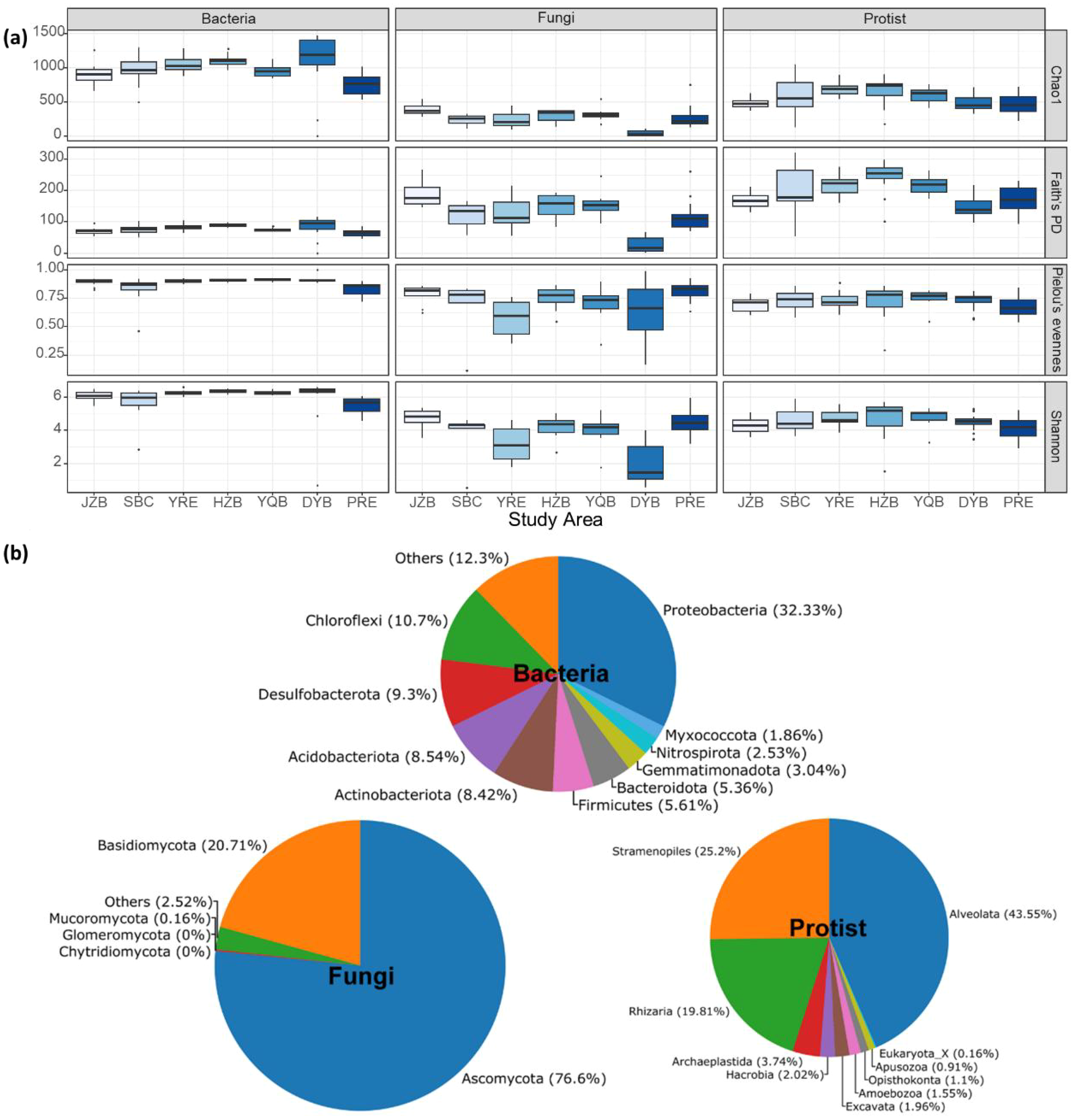

α-diversity analysis revealed significant differences among bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities across a latitudinal gradient spanning seven coastal and estuarine regions in China. Bacterial communities generally exhibited higher richness and diversity than fungal and protistan communities, with higher values across most indices. While diversity levels varied among regions, no consistent spatial trend was observed along the latitude gradient. Notably, bacterial diversity was relatively high in Daya Bay, whereas fungal diversity was lower in the same area. In contrast, protistan diversity was higher in Hangzhou Bay (Figure 2A). These findings suggest that the α-diversity patterns of different microbial groups are influenced by regional environmental factors in a group-specific manner. Regarding taxonomic composition, Proteobacteria was the dominant bacterial phylum, followed by Chloroflexi, Dsulfobacterota, Acidobacteriota, and Actinobacteriota. In fungi, Ascomycota was the predominant phylum, with Basidiomycota as the second most abundant. Among protists, Alveolata was the dominant group, followed by Stramenopiles and Rhizaria (Figure 2B).

Figure 2

α-diversity indexes (Chao1, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, Shannon, and Pielou’s evenness) for the bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities in seven coastal and estuarine regions spanning from northern to southern China (A). Relative abundances of bacteria, fungi and protist at the phylum level (B). JZB, Jiaozhou Bay; SBC, Subei Coast; YRE, Yangtze River Estuary; HZB, Hangzhou Bay; YQB, Yueqing Bay; DYB, Daya Bay; PRE, Pearl River Estuary.

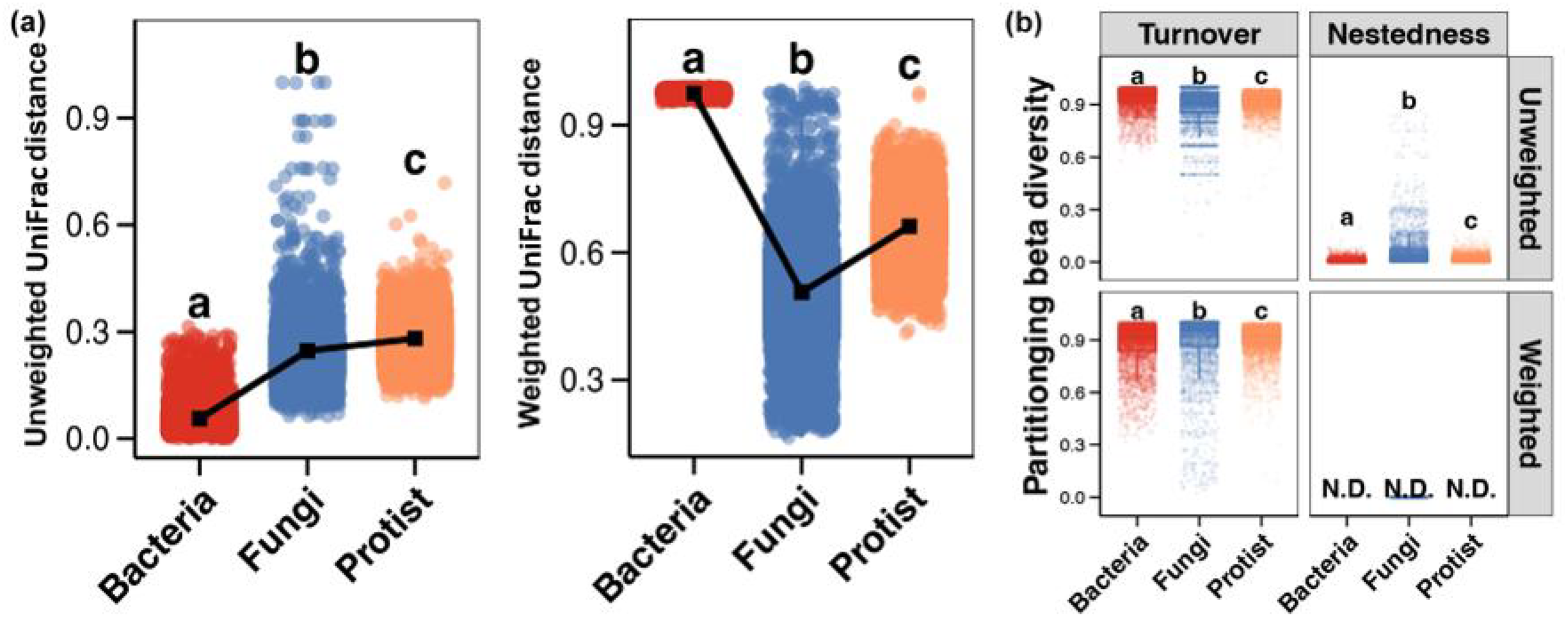

Based on UniFrac distance, protist communities showed the greatest change, followed by fungi, with bacteria showing the least. Based on Weighted UniFrac distance, bacterial communities showed the greatest change, followed by protists, and fungi showed the least (Figure 3A). According to the betapart analysis, species turnover was the main driver of change for all three trophic groups. Compared to Weighted UniFrac distance, species nestedness contributed more to changes based on UniFrac distance (Figure 3B). Species turnover contributed most to bacterial community changes, followed by protists, and least to fungal changes. In contrast, species nestedness contributed most to fungal community changes.

Figure 3

β-diversity of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities based on UniFrac and Weighted UniFrac distances. (A) and differences in the species turnover and nestedness of β-diversity patterns (B) Different lowercase letters above each box in the same subfigure represent significant differences between groups (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05).

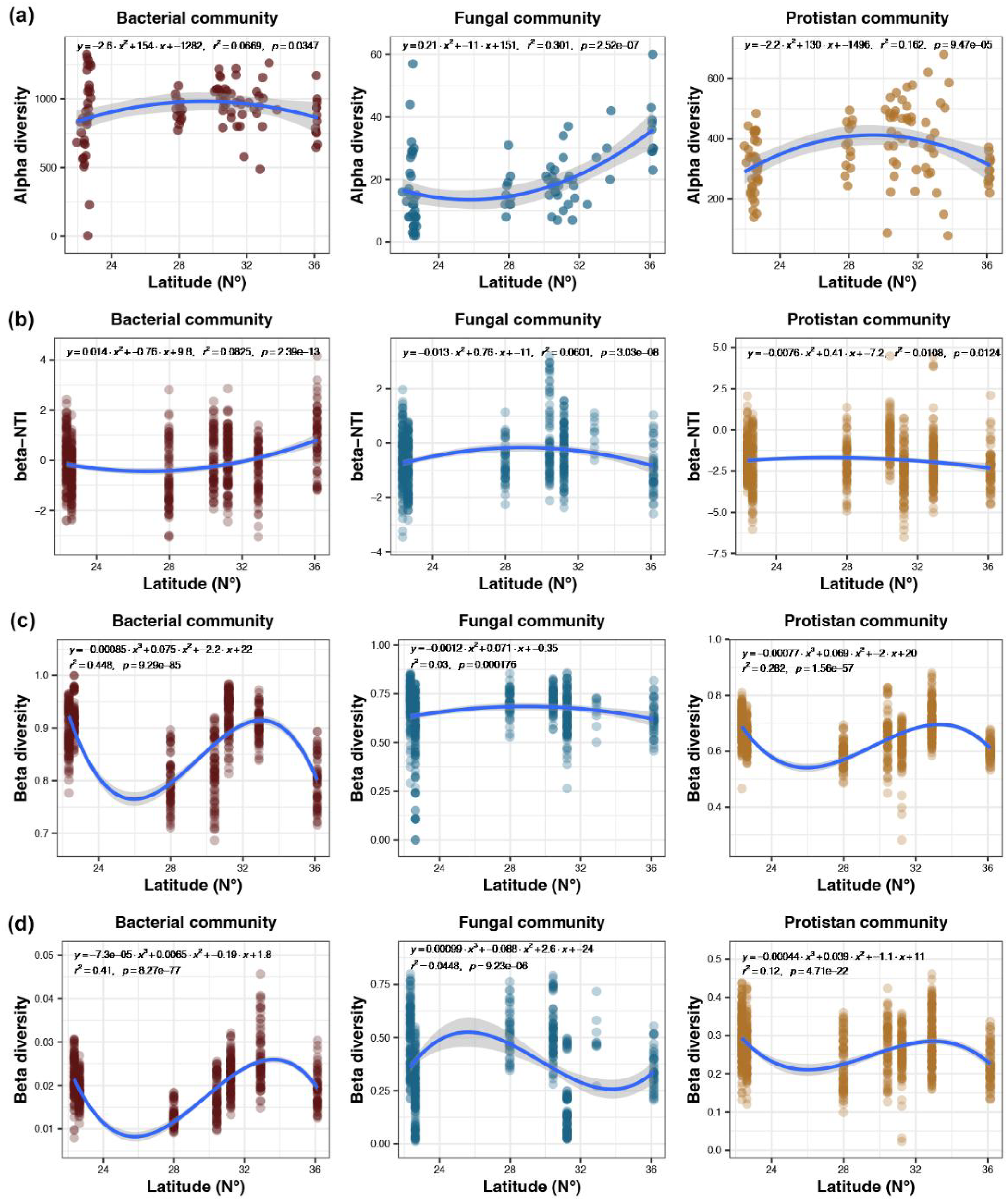

As latitude increases, the α- diversity of bacterial communities follows a bimodal distribution, initially increasing until around 30°N before declining. Fungal α-diversity also shows a bimodal pattern but decreases first until around 26°N before increasing. Protistan α-diversity increases to around 30°N and then decreases, exhibiting a similar bimodal trend (Figure 4A). With increasing latitude, the β-NTI of bacterial communities displays a bimodal distribution, decreasing until around 27°N and then increasing. Fungal β-NTI increases until approximately 29°N and then decreases, following a bimodal pattern. Protistan β-NTI also shows a bimodal distribution, peaking around 27°N (Figure 4B). The β-diversity of bacterial communities varies with latitude in a bimodal pattern: it first decreases, then increases, and decreases again. Fungal β-diversity follows a bimodal distribution, rising until around 29°N and then falling. Protistan β-diversity exhibits a bimodal pattern similar to bacteria, with initial decrease, followed by increase and then decrease again (Figure 4C). In terms of latitude-dependent β-diversity changes, bacterial communities show a bimodal trend of first decreasing, increasing, and then decreasing. Fungal communities display a bimodal pattern of initial increase, subsequent decrease, and final increase. Protistan communities also follow a bimodal trend of decrease, increase, and then decrease (Figure 4D).

Figure 4

Latitude-dependent changes in microbial communities. α-diversity changes (A); local community assembly changes (B); β-diversity changes based on UniFrac distance (C) and Weighted UniFrac distance (D).

3.2 Community assembly and environmental adaptability

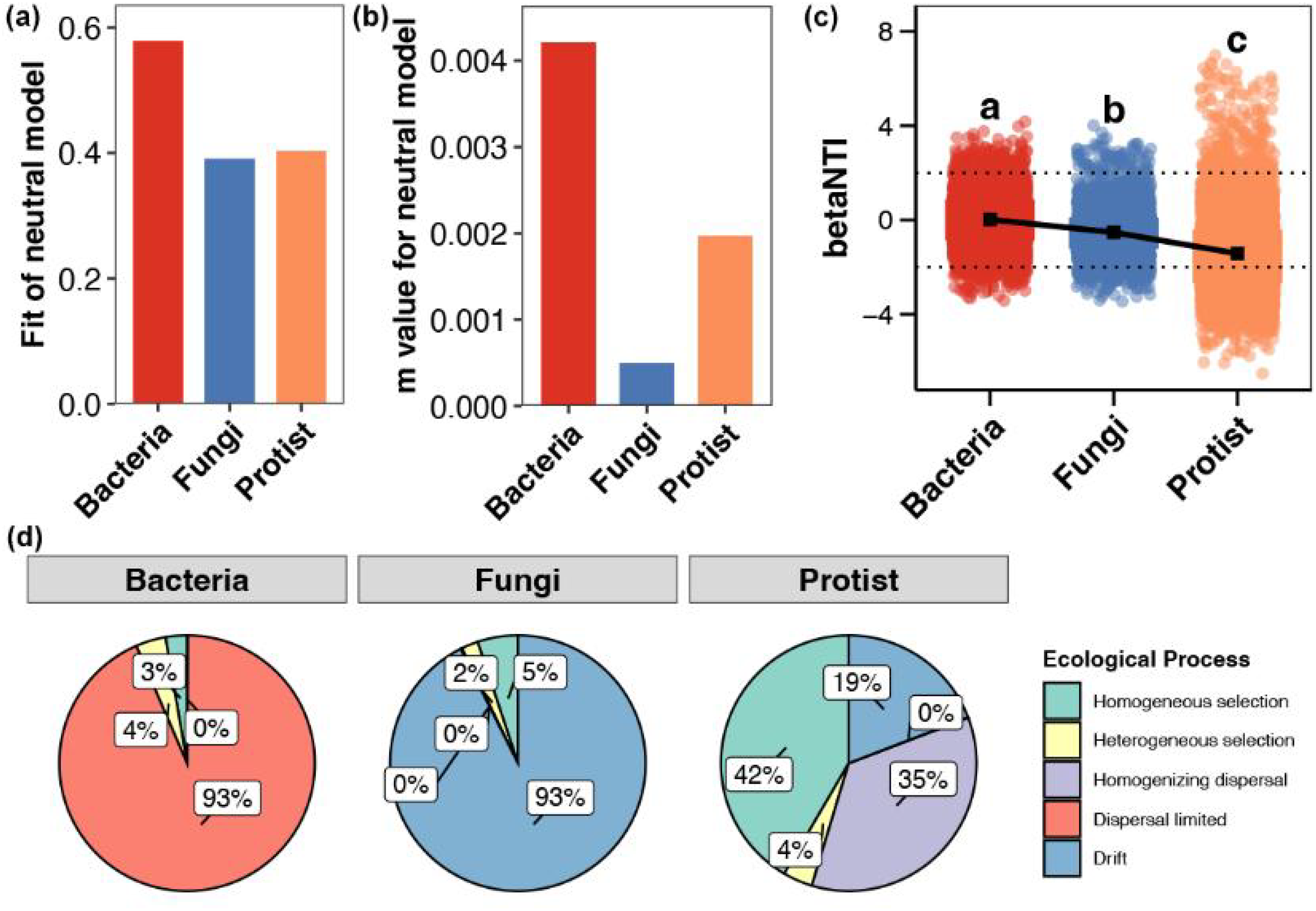

Neutral models revealed that stochastic processes contributed more to bacterial community assembly than to fungal and protistan communities (Figure 5A). They also indicated that bacterial communities had the highest dispersal ability, followed by protists, with fungal communities having the lowest (Figure 5B). Consistently, betaNTI results showed that stochastic processes had the strongest influence on bacterial community assembly and the weakest on protistan assembly (Figure 5C). Further null model analyses demonstrated that bacterial community assembly was primarily governed by dispersal limitation, while fungal assembly was mainly controlled by ecological drift. In contrast, protistan community assembly was more complex, being regulated by both homogeneous selection and homogeneous dispersal (Figure 5D).

Figure 5

Community assembly processes of multitrophic microbial groups. (A) Contribution of stochastic processes to community assembly. (B) Dispersal ability of communities. (C) Differences in the betaNTI between bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities. Each point represents a pair of samples, with the dotted lines indicating the thresholds of 2 and −2, which separate deterministic processes from random processes. (D) Relative importance of ecological processes (i.e., homogeneous selection, heterogeneous selection, homogeneous dispersal, dispersal limitation, and drift) in structuring the aggregation of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities. Different lowercase letters above each box in the same subfigure represent significant differences between groups (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05).

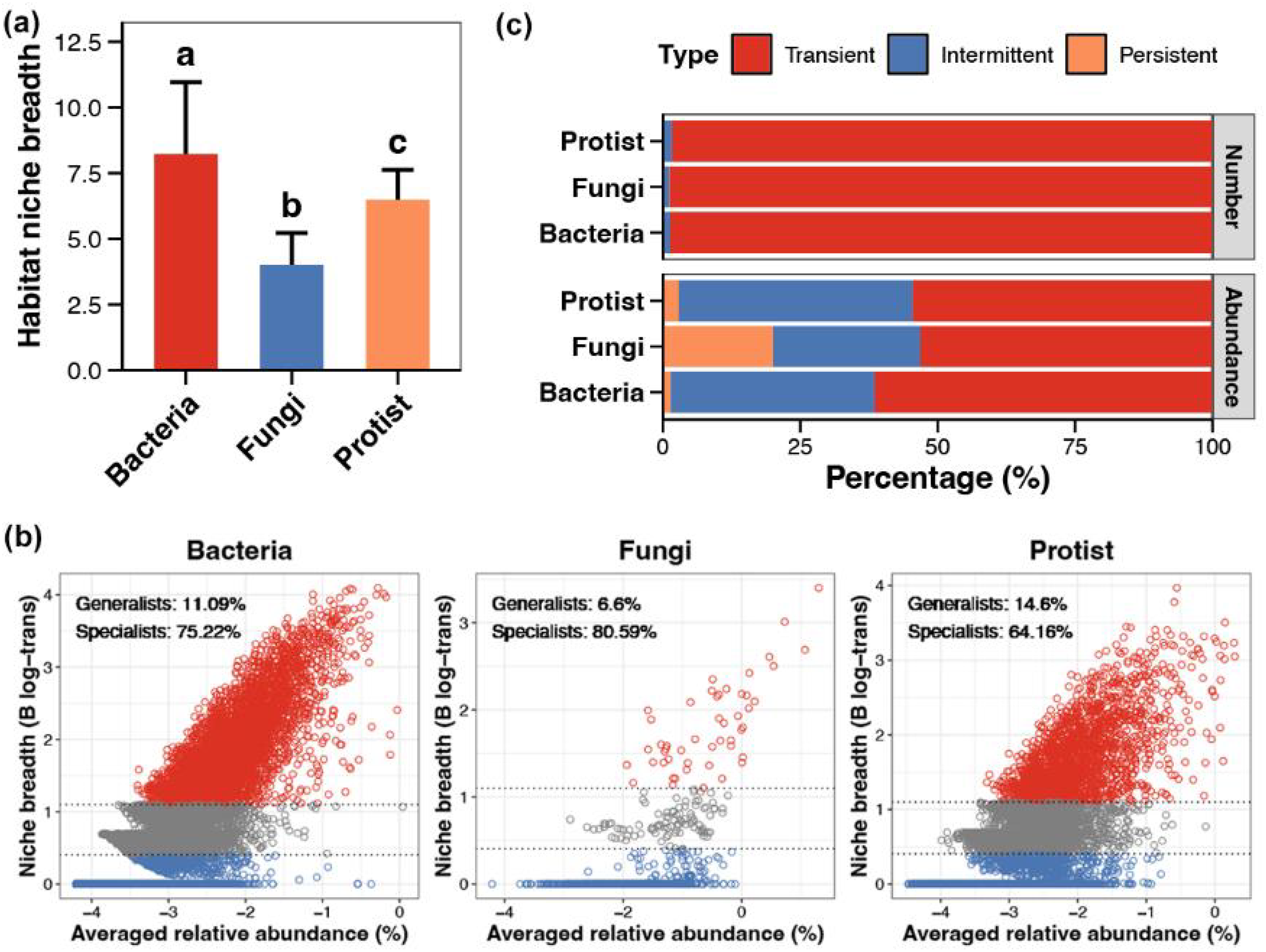

In terms of environmental adaptability, bacterial communities have the highest habitat niche breadth, followed by protists and fungi(Figure 6A). In bacterial communities, 11.09% of species are generalists and 75.22% are specialists. In fungal communities, 6.60% are generalists and 80.59% are specialists. In protistan communities,14.60% are generalists and 64.16% are specialists (Figure 6B). Most species in the three trophic levels are transient species. Bacterial communities have a slightly higher proportion of transient species, while protistan communities have a slightly lower proportion. Bacterial communities also have the highest abundance of transient species. In fungal communities, a significant portion of the abundance is attributed to persistent species (Figure 6C). Overall, bacterial communities show the strongest environmental adaptability, while fungal communities show the weakest.

Figure 6

Environmental adaptability of microbial communities. (A) Habitat niche breadth of bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities based on the Levins’ niche breadth index. (B) Relationship between species’ average relative abundance and niche breadth. (C) Persistence types (transient, intermittent, and persistent) of species in different biological groups. Different lowercase letters above each box in the same subfigure represent significant differences between groups (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05).

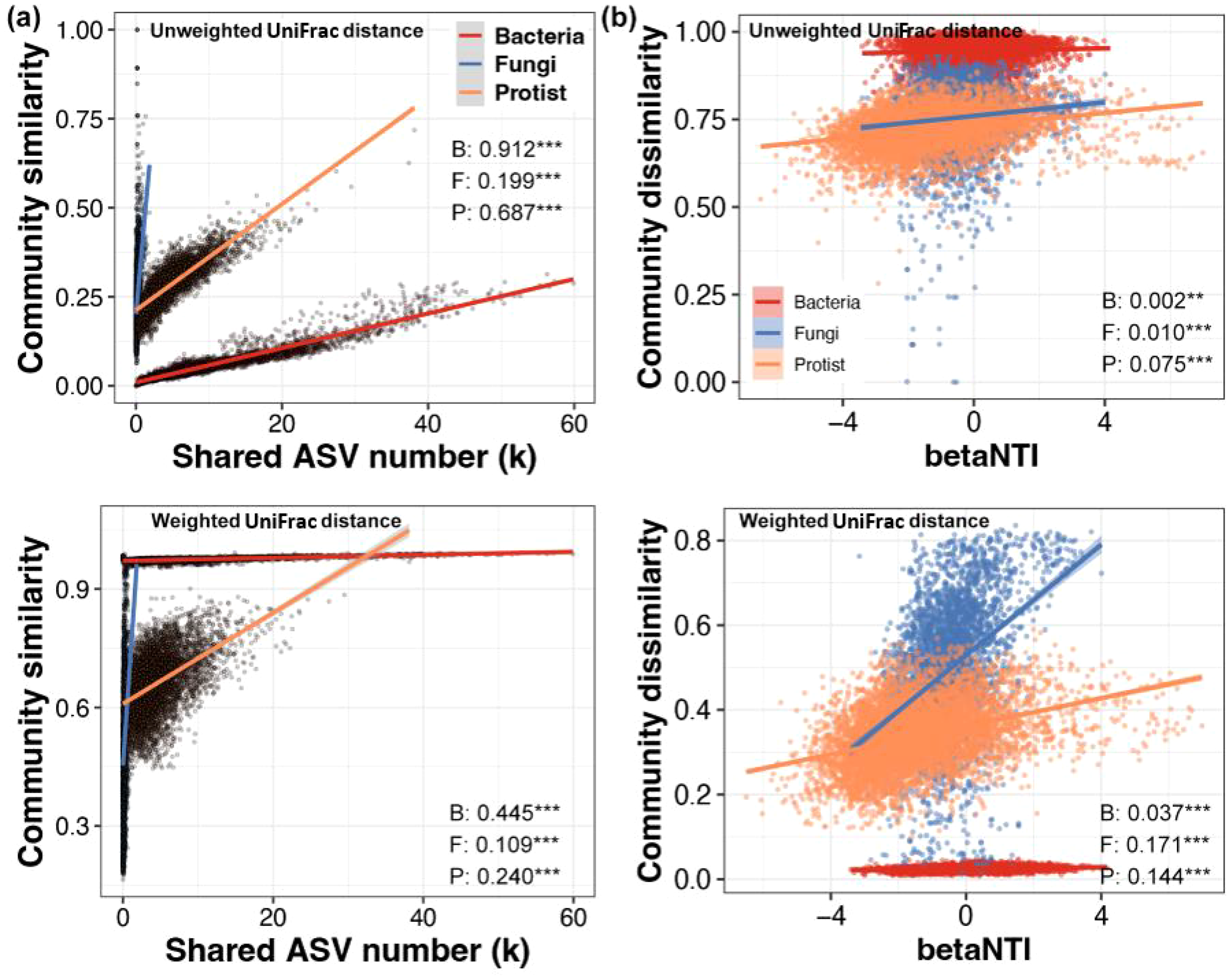

Bacterial β-diversity was predominantly shaped by local species pools, showing the strongest correlation among all groups for both Unweighted (R2 = 0.912, p < 0.001) and Weighted UniFrac (R2 = 0.445, p < 0.001). In contrast, the link to local assembly (βNTI) was the weakest (R2 = 0.037, p < 0.001). Fungal communities showed the opposite pattern. They were the least influenced by local species pools (Unweighted: R2 = 0.199, p < 0.001; Weighted: R2 = 0.109, p < 0.001) but were most strongly associated with local assembly mechanisms (βNTI; R2 = 0.171, p < 0.001). Protists exhibited an intermediate response, with a moderate influence from both local species pools (Unweighted: R2 = 0.687, p < 0.001; Weighted: R2 = 0.240, p < 0.001) and local assembly (βNTI; R2 = 0.144, p < 0.001). Furthermore, shifting from presence-absence (Unweighted UniFrac) to abundance-based (Weighted UniFrac) metrics consistently reduced the role of species pools and enhanced the apparent role of local assembly across all groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Relative contributions of regional species pools and local assembly processes to β-diversity of bacterial, fungal, and protistan Communities. (A) Linear regression analysis of the number of shared ASVs between different samples and their corresponding β-diversity distance based on UniFrac (upper) and Weighted (lower) UniFrac distances. (B) Linear regression analysis of the betaNTI between different samples and their corresponding β-diversity distance based on UniFrac (upper) and Weighted (lower) UniFrac distances. B, Bacteria; F, Fungi; P, Protist. Values are R² (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

In terms of microbial community composition, Proteobacteria emerged as the dominant bacterial phylum, accounting for 32.33% of the total bacterial population. This phylum is ubiquitously distributed across diverse ecosystems and plays pivotal roles in biogeochemical cycles and energy transformations. Notably, many Proteobacteria species actively participate in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling, which are essential for sustaining ecosystem functionality (Delmont et al., 2018). Other bacterial phyla, including Chloroflexi, Desulfobacterota, Acidobacteriota, and Actinobacteriota, collectively contributed to functional diversity within the bacterial community. Among fungi, Ascomycota predominated (76.6%), reflecting their ecological dominance in saprotrophic and symbiotic niches, particularly through decomposition of complex organic matter and mutualistic nutrient exchange with phytoplankton (Comeau et al., 2016). Basidiomycota, as the second-largest fungal phylum, further facilitated organic decomposition and nutrient cycling. Within protistan communities, Alveolata constituted the largest proportion (43.55%), with their motility and predatory behaviors significantly influencing microbial community dynamics in aquatic ecosystems. Stramenopiles (25.2%) and Rhizaria (19.81%) occupied distinct ecological niches, contributing to photosynthesis, organic decomposition, and benthic predation, thereby driving energy transfer and nutrient cycling.

α-diversity metrics (Chao1, Shannon, and Pielou’s evenness) revealed significantly higher species richness and community evenness in bacteria compared to fungi and protists. This disparity likely stems from bacterial adaptability and rapid reproductive rates, enabling colonization across heterogeneous habitats (Fierer et al., 2012). Intriguingly, protists exhibited the highest Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (Faith’s PD), suggesting phylogenetically distinct lineages shaped by evolutionary processes, potentially through predation-mediated regulation of microbial community structure (Geisen et al., 2018). Conversely, the lower α-diversity observed in fungi may relate to their substrate-specific decomposition strategies (e.g., lignin and chitin degradation), which intensify competitive exclusion (Tedersoo et al., 2014).

β-diversity patterns and their drivers exhibited pronounced trophic-level differentiation. UniFrac distance analysis indicated the highest β-diversity in protists, followed by fungi and bacteria. This hierarchy may reflect differences in dispersal capacity and niche breadth: Protists, constrained by larger body sizes and limited motility (Finlay, 2002), demonstrate dispersal limitation and strong dependence on localized prey heterogeneity (Geisen et al., 2018). In contrast, bacteria maintain relatively homogeneous communities across environments due to efficient dispersal and metabolic versatility (e.g., multifunctional pathways in Proteobacteria) (Hanson et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2023). However, Weighted UniFrac analysis revealed the highest bacterial β-diversity, indicating sensitivity of dominant taxa (e.g., Chloroflexi) to environmental gradients (e.g., carbon availability, pH), while fungal and protistan communities showed lower weighted UniFrac distances (as indicated in Figure 3), implying a lesser degree of change in community composition along the spatial/environmental gradients. This contrast implies stronger environmental filtering on bacteria versus greater influences of dispersal limitation or biotic interactions (e.g., competition, predation) on fungi and protists (Sun et al., 2022).

Mechanistically, microbial community assembly exhibited trophic-level functional linkages. Our results show bacteria have the highest habitat niche breadth (Figure 6A) and dispersal ability (Figure 5B) among the three groups, consistent with their adaptability to heterogeneous sediment environments. This allows bacteria to rapidly colonize and utilize variable resources in coastal sediments (Jetschke and Hubbell, 2002; Wan et al., 2023). Fungi, dominated by Ascomycota (76.6% relative abundance, Figure 2B), a phylum well-documented for decomposing recalcitrant organic matter, showed high specialization: 80.59% of fungal species were identified as specialists (Figure 6B), indicating their strong dependence on specific microhabitats (Peay et al., 2016; Tedersoo et al., 2014). Protists, as consumers in sediment microbial food webs, exhibited dual assembly controls (homogeneous selection: 28%; homogenizing dispersal: 31%, Figure 5D), a pattern aligning with their key ecological roles in top-down bacterial community shaping via predation and adaptation to environmental gradients. Notably, our analysis of UniFrac and Weighted UniFrac metrics further clarified these trophic differences. UniFrac emphasized regional species pool influences (especially for bacteria), while Weighted UniFrac highlighted local resource sensitivity (particularly for fungi) (Fierer et al., 2012; Stegen et al., 2013). These patterns reflect divergent ecological strategies: bacteria maintain cross-habitat adaptability through functional redundancy and dispersal, fungi stabilize decomposition via substrate specialization, and protists modulate network complexity through predator-mediated cascades (Grossmann et al., 2016; Wagg et al., 2019). Our findings support the “dispersal-niche” continuum in microbial ecology and inform ecosystem management—preserving bacterial diversity requires enhancing habitat connectivity, whereas fungal conservation necessitates microhabitat protection (e.g., humus layers). Future studies should integrate multi-omics approaches across environmental gradients to elucidate linkages between assembly mechanisms and ecosystem functions under global change.

Species turnover emerged as the primary driver of β-diversity across bacterial, fungal, and protistan communities, though the relative contributions of turnover varied significantly among these groups. For bacteria, the predominance of species turnover points to a community structure shaped primarily by niche-based processes. The distinct environmental conditions present at different sites (e.g., in oxygen levels and organic matter composition) selectively favor different sets of bacterial taxa. Consequently, spatial variation in community composition arises chiefly from the sorting and replacement of habitat-specialist species, as illustrated by the distribution of dominant phyla like Proteobacteria, rather than from simple nested subsets of a core community. In contrast, fungal β-diversity exhibited the highest nestedness contribution, likely linked to their strong reliance on specialized resources (e.g., lignin decomposition, mycorrhizal symbiosis). Under resource heterogeneity or disturbances (e.g., disrupted organic matter inputs), stochastic loss of substrate-dependent fungal taxa (e.g., Ascomycota saprotrophs) may generate nested community structures (Peay et al., 2016). Protistan communities displayed intermediate species turnover contributions between bacteria and fungi, suggesting dual regulation of their assembly processes: predation pressure driving species replacement and habitat fragmentation promoting nestedness (Lentendu et al., 2018).

This study revealed distinct latitudinal patterns in α-diversity across microbial groups. Bacterial and protistan communities exhibited unimodal trends, peaking around 30°N, likely due to moderate temperatures and resource heterogeneity in mid-latitudes that promote niche differentiation and species coexistence (Bahram et al., 2018). In contrast, fungal α-diversity followed a unimodal pattern, with the lowest values near 26°N, suggesting dual regulation by intense resource competition at low latitudes and low-temperature constraints on metabolic activity at high latitudes (Tedersoo et al., 2014). These patterns are consistent with our regional observations—for instance, higher bacterial diversity in Daya Bay but lower fungal diversity in the same region, and higher protistan diversity in Hangzhou Bay—supporting the notion that α-diversity is shaped by regional environmental factors in a taxon-specific manner. Community assembly mechanisms also diverged markedly across taxa. Bacterial β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) showed a unimodal distribution, with the lowest values near 27°N, indicating that stochastic dispersal dominated assembly in mid-latitudes, while environmental filtering (e.g., temperature selection) intensified at both low and high latitudes. Conversely, the assembly of fungal and protistan communities, indicated by βNTI, showed significant non-linear responses to latitude. The influence of deterministic processes peaked at intermediate latitudes (~29°N and ~27°N, respectively), forming a unimodal pattern. We hypothesize that these mid-latitude peaks may correspond to transitional zones where shifts in factors known to structure microbial communities—such as substrate specificity for saprotrophic fungi or predation pressure within the microbial food web—are most pronounced, thereby intensifying deterministic selection (Geisen et al., 2018; Heino et al., 2015; Peay et al., 2016).

Latitudinal patterns of β-diversity further highlighted the complexity of multi-factor interactions. Bacterial and protistan β-diversity followed bimodal distributions—initially decreasing, then increasing, and subsequently decreasing with latitude—suggesting sequential regulation by competitive homogenization in low latitudes, environmental heterogeneity-driven differentiation in mid-latitudes, and strong environmental filtering in high latitudes. Fungal β-diversity, however, exhibited a multi-peak response pattern (rising, declining, then rising again) across the latitudinal gradient. This non-monotonic pattern suggests the influence of multiple, interacting environmental factors with nonlinear relationships. While the specific drivers require further validation, we speculate that known nonlinear drivers of fungal community composition, such as threshold effects of lignin accumulation and seasonal succession driven by temperature fluctuations, could contribute to generating such a complex spatial pattern (Peay et al., 2016; Tedersoo et al., 2014). Notably, the coincident α-diversity peaks of bacteria and protists at 30°N imply potential functional coupling between these groups. Specifically, protists may regulate bacterial community structure via predation (top-down effects), while bacterial resource competition reciprocally shapes protistan composition (bottom-up effects), forming a bidirectional regulatory network (Grossmann et al., 2016). In contrast, the independent latitudinal response of fungal diversity may stem from allelopathic interactions mediated by secondary metabolites, which decouple direct associations between environmental selection and diversity (Wagg et al., 2019).

Stochastic processes contributed most significantly to bacterial community assembly, while exerting the weakest influence on protistan communities. Our finding that bacterial communities exhibited the widest niche breadth and the strongest signal of stochastic processes aligns with the broader ecological principle that body size influences dispersal and environmental sensitivity (Xu et al., 2024). Smaller organisms, like bacteria, generally have higher population densities and greater metabolic plasticity, which can enhance their dispersal potential and survival in suboptimal habitats. This biological reality may underpin the greater relative importance of stochastic assembly (e.g., ecological drift and dispersal limitation) we observed in bacterioplankton, as their small size could buffer them from strict environmental filtering. In contrast, protistan community assembly was primarily co-driven by homogeneous selection and dispersal, suggesting their adaptation to homogenized environments through phenotypic plasticity or conserved niche requirements (An et al., 2023). Fungal communities, meanwhile, were predominantly shaped by ecological drift, likely due to their limited dispersal efficiency and strong dependency on specific microhabitats (e.g., humus layers, mycorrhizal networks) (Peay et al., 2016). These trophic-level-specific assembly patterns highlight distinct ecological strategies among microbial groups in coastal ecosystems: Bacteria, as “stochastic-dominant” taxa, achieve broad distribution via high dispersal capacity; fungi, as “drift-sensitive” taxa, are vulnerable to localized environmental fluctuations; and protists, as “selection-dispersal trade-off” taxa, balance environmental filtering and dispersal limitation.

Bacterial communities in coastal sediments exhibited the strongest environmental adaptability. Although generalist species constituted only 11.09% of their composition, their high dispersal capacity likely sustains functional redundancy through rapid species turnover of transient taxa (e.g., opportunistic decomposers). This adaptability is closely tied to bacterial metabolic diversity and functional plasticity. For instance, generalist phyla like Proteobacteria can adjust metabolic pathways to adapt to redox gradients (Delmont et al., 2018). In contrast, fungal communities were dominated by specialist taxa (80.59%), with persistent species occupying high relative abundances, indicating that their stability relies on long-term colonization by key functional groups (e.g., Ascomycota lignin degraders). This specialization may increase their vulnerability to resource depletion or disturbances (Wagg et al., 2019). Protistan environmental adaptability fell between bacteria and fungi, with a higher proportion of generalists (14.6%) potentially linked to flexible predation strategies (e.g., Alveolata’s broad prey spectrum). However, dispersal limitation still constrains their cross-habitat adaptability (Geisen et al., 2018). From an ecosystem function perspective, the stochastic assembly and dominance of transient species in bacteria may enhance functional resilience, enabling rapid post-disturbance recovery of metabolic activity through species replacement (Zou et al., 2021). Conversely, fungal reliance on specialists and narrow environmental niches underscores the critical need to protect specific microhabitats (e.g., organic matter layers) to sustain decomposition functions. As “intermediate regulators”, protists’ selection-dispersal trade-offs may cascade through microbial network stability via combined top-down (predation pressure) and bottom-up (resource competition) effects (Grossmann et al., 2016).

While this study offers valuable insights into latitudinal diversity patterns, two key limitations should be considered. First, the observed latitudinal trends were not examined across a fully continuous and uniform geographic gradient. The sampling sites were clustered within distinct regions, including the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, and South China Sea, which may introduce confounding regional effects and limit our ability to disentangle latitudinal influences from other region-specific environmental factors. Second, the snapshot sampling design used in this study captures spatial variation but does not account for temporal dynamics, such as seasonal succession, that may influence community assembly. To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the drivers behind these biogeographic patterns, future studies should adopt continuous and extensive spatial sampling, along with temporal monitoring and experimental manipulations, to better elucidate the causal mechanisms at play.

Statements

Data availability statement

16S, ITS and 18S rDNA amplicon and shotgun sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information short reads archive (SRA) database under BioProject numbers PRJNA815376, PRJNA815462, PRJNA1277792, PRJNA1277579, PRJNA1277593, PRJNA1277700 and PRJNA1277794.

Author contributions

YZ: Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XG: Writing – original draft, Visualization. ZS: Methodology, Writing – original draft. YS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. ZZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation. HL: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. JY: Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0607600), Liaoning Province Natural Science Foundation Program (doctoral research project) (2024-BS-301) and Key Laboratory of Coastal Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Ecology and Environment (20240106).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aguilar P. Sommaruga R. (2020). The balance between deterministic and stochastic processes in structuring lake bacterioplankton community over time. Mol. Ecol.29, 3117–3130. doi: 10.1111/mec.15538

2

An R. Liu Y. Pan C. Da Z. Zhang P. Qiao N. (2023). Water quality determines protist taxonomic and functional group composition in a high-altitude wetland of international importance. Sci. Total Environ.880, 163308. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163308

3

Azam F. Malfatti F. (2007). Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.5, 782–791. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747

4

Bahram M. Hildebrand F. Forslund S. K. Anderson J. L. Soudzilovskaia N. A. Bodegom P. M. et al . (2018). Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature.560, 233–237. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6

5

Barbier E. B. Hacker S. D. Kennedy C. Koch E. W. Stier A. C. Silliman B. R. (2011). The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr.81, 169–193. doi: 10.1890/10-1510.1

6

Baselga A. Orme D. Villeger S. Bortoli. J. Leprieur F. Logez M. et al . (2025). betapart: Partitioning Beta Diversity into Turnover and Nestedness Components ( R package version 1.6.1). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=betapart (Accessed June 15, 2025).

7

Bokulich N. A. Kaehler B. D. Rideout J. R. Dillon M. Bolyen E. Knight R. et al . (2018). Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome.6, 90. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z

8

Breyer E. Zhao Z. Herndl G. J. Baltar F. (2022). Global contribution of pelagic fungi to protein degradation in the ocean. Microbiome.10, 143. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01329-5

9

Callahan B. J. McMurdie P. J. Rosen M. J. Han A. W. Johnson A. J. A. Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods.13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

10

Chen J. Zhang X. Yang L. Zhang L. (2023). GUniFrac: Generalized UniFrac Distances, Distance-Based Multivariate Methods and Feature-Based Univariate Methods for Microbiome Data Analysis ( R package version 1.8). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GUniFrac (Accessed August 22, 2023).

11

Cloern J. E. Abreu P. C. Carstensen J. Chauvaud L. Elmgren R. Grall J. et al . (2016). Human activities and climate variability drive fast-paced change across the world’s estuarine–coastal ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol.22, 513–529. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13059

12

Comeau A. M. Vincent W. F. Bernier L. Lovejoy C. (2016). Novel chytrid lineages dominate fungal sequences in diverse marine and freshwater habitats. Sci. Rep.6, 30120. doi: 10.1038/srep30120

13

Cottenie K. (2005). Integrating environmental and spatial processes in ecological community dynamics. Ecol. Lett.8, 1175–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00820.x

14

Delmont T. O. Quince C. Shaiber A. Esen Ö.C. Lee S. T. Rappé M. S. et al . (2018). Nitrogen-fixing populations of Planctomycetes and Proteobacteria are abundant in surface ocean metagenomes. Nat. Microbiol.3, 804–813. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0176-9

15

Fierer N. (2017). Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.15, 579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.87

16

Fierer N. Leff J. W. Adams B. J. Nielsen U. N. Bates S. T. Lauber C. L. et al . (2012). Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.109, 21390–21395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215210110

17

Finlay B. J. (2002). Global dispersal of free-living microbial eukaryote species. Science.296, 1061–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.1070710

18

Geisen S. Mitchell E. A. D. Adl S. Bonkowski M. Dunthorn M. Ekelund F. et al . (2018). Soil protists: a fertile frontier in soil biology research. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.42, 293–323. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy006

19

Glöckner F. O. Yilmaz P. Quast C. Gerken J. Beccati A. Ciuprina A. et al . (2017). 25 years of serving the community with ribosomal RNA gene reference databases and tools. J. Biotechnol.261, 169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.06.1198

20

Grossmann L. Jensen M. Heider D. Jost S. Glücksman E. Hartikainen H. et al . (2016). Protistan community analysis: key findings of a large-scale molecular sampling. ISME J.10, 2269–2279. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.10

21

Hanson C. A. Fuhrman J. A. Horner-Devine M. C. Martiny J. B. H. (2012). Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.10, 497–506. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2795

22

Heino J. Melo A. S. Siqueira T. Soininen J. Valanko S. Bini L. M. (2015). Metacommunity organisation, spatial extent and dispersal in aquatic systems: patterns, processes and prospects. Freshw. Biol.60, 845–869. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12533

23

Hijmans R. (2024). geosphere: spherical trigonometry ( R package version 1.5-20). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=geosphere (Accessed March 10, 2024).

24

Jetschke G. Hubbell S. P. (2002). The unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography. Ecology.83, 1771. doi: 10.2307/3071998

25

Kraemer S. Ramachandran A. Colatriano D. Lovejoy C. Walsh D. A. (2020). Diversity and biogeography of SAR11 bacteria from the Arctic Ocean. ISME J.14, 79–90. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0499-4

26

Lentendu G. Mahé F. Bass D. Rueckert S. Stoeck T. Dunthorn M. (2018). Consistent patterns of high alpha and low beta diversity in tropical parasitic and free-living protists. Mol. Ecol.27, 2846–2857. doi: 10.1111/mec.14731

27

Lin L. Ma H. Zhang J. Yang H. Zhang J. Zhang L. et al . (2024). Lignocellulolytic microbiomes orchestrating degradation cascades in the rumen of dairy cattle and their diet-influenced key degradation phases. Anim. Adv.1, e002. doi: 10.48130/animadv-0024-0002

28

Logares R. Haverkamp T. H. A. Kumar S. Lanzén A. Nederbragt A. J. Quince C. et al . (2012). Environmental microbiology through the lens of high-throughput DNA sequencing: Synopsis of current platforms and bioinformatics approaches. J. Microbiol. Methods.91, 106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.07.017

29

Lozupone C. A. Knight R. (2007). Global patterns in bacterial diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.104, 11436–11440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611525104

30

Lozupone C. Lladser M. E. Knights D. Stombaugh J. Knight R. (2011). UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J.5, 169–172. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.133

31

Lu Y. Yuan J. Lu X. Su C. Zhang Y. Wang C. et al . (2018). Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. pollut.239, 670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.016

32

Moran M. A. (2015). The global ocean microbiome. Science80, 350. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8455

33

Nemergut D. R. Schmidt S. K. Fukami T. O’Neill S. P. Bilinski T. M. Stanish L. F. et al . (2013). Patterns and processes of microbial community assembly. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.77, 342–356. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00051-12

34

Nilsson R. H. Larsson K. H. Taylor A. F. S. Bengtsson-Palme J. Jeppesen T. S. Schigel D. et al . (2019). The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 259–264. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1022

35

Oksanen J. Simpson G. Blanchet F. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. et al . (2025). vegan: Community Ecology Package ( R package version 2.6-10). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (Accessed April 3, 2025).

36

Padial A. A. Ceschin F. Declerck S. A. J. De Meester L. Bonecker C. C. Lansac-Tôha F. A. et al . (2014). Dispersal ability determines the role of environmental, spatial and temporal drivers of metacommunity structure. PloS One.9, e111227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111227

37

Peay K. G. Kennedy P. G. Talbot J. M. (2016). Dimensions of biodiversity in the Earth mycobiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.14, 434–447. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.59

38

Qian G. Wang J. Kan J. Zhang X. Xia Z. Zhang X. et al . (2018). Diversity and distribution of anammox bacteria in water column and sediments of the Eastern Indian Ocean. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation.133, 52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.05.015

39

Ragon M. Fontaine M. C. Moreira D. López-García P. (2012). Different biogeographic patterns of prokaryotes and microbial eukaryotes in epilithic biofilms. Mol. Ecol.21, 3852–3868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05659.x

40

Singer D. Seppey C. V. W. Lentendu G. Dunthorn M. Bass D. Belbahri L. et al . (2021). Protist taxonomic and functional diversity in soil, freshwater and marine ecosystems. Environ. Int.146, 106262. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106262

41

Stegen J. C. Lin X. Fredrickson J. K. Chen X. Kennedy D. W. Murray C. J. et al . (2013). Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J.7, 2069–2079. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.93

42

Stoeck T. Behnke A. Christen R. Amaral-Zettler L. Rodriguez-Mora M. J. Chistoserdov A. et al . (2009). Massively parallel tag sequencing reveals the complexity of anaerobic marine protistan communities. BMC Biol.7, 72. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-72

43

Sun P. Wang Y. Huang X. Huang B. Wang L. (2022). Water masses and their associated temperature and cross-domain biotic factors co-shape upwelling microbial communities. Water Res.215, 118274. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118274

44

Tedersoo L. Bahram M. Põlme S. Kõljalg U. Yorou N. S. Wijesundera R. et al . (2014). Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science.80, 346. doi: 10.1126/science.1256688

45

Wagg C. Schlaeppi K. Banerjee S. Kuramae E. E. van der Heijden M. G. A. (2019). Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun.10, 4841. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12798-y

46

Wan W. Gadd G. M. Gu J. Liu W. Chen P. Zhang Q. et al . (2023). Beyond biogeographic patterns: Processes shaping the microbial landscape in soils and sediments along the Yangtze River. mLife.2, 89–100. doi: 10.1002/mlf2.12062

47

Wu W. Lu H. P. Sastri A. Yeh Y. C. Gong G. C. Chou W. C. et al . (2018). Contrasting the relative importance of species sorting and dispersal limitation in shaping marine bacterial versus protist communities. ISME J.12, 485–494. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.183

48

Wu L. Ning D. Zhang B. Li Y. Zhang P. Shan X. et al . (2019). Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Microbiol.4, 1183–1195. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0426-5

49

Xu Y. Chen X. Graco-Roza C. Soininen J. (2024). Scale dependency of community assembly differs between coastal marine bacteria and fungi. Ecography.2024, e06863. doi: 10.1111/ecog.06863

50

Xu X. Yuan Y. Wang Z. Zheng T. Cai H. Yi M. et al . (2023). Environmental DNA metabarcoding reveals the impacts of anthropogenic pollution on multitrophic aquatic communities across an urban river of western China. Environ. Res.216, 114512. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114512

51

Zakrzewski M. Goesmann A. Jaenicke S. Jünemann S. Eikmeyer F. Szczepanowski R. et al . (2012). Profiling of the metabolically active community from a production-scale biogas plant by means of high-throughput metatranscriptome sequencing. J. Biotechnol.158, 248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.01.020

52

Zhang Y. J. Zhang S. Liu X. Z. Wen H. A. Wang M. (2010). A simple method of genomic DNA extraction suitable for analysis of bulk fungal strains. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 114–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02867.x

53

Zhao Z. Li H. Sun Y. Shao K. Wang X. Ma X. et al . (2022a). How habitat heterogeneity shapes bacterial and protistan communities in temperate coastal areas near estuaries. Environ. Microbiol.24, 1775–1789. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15892

54

Zhao Z. Li H. Sun Y. Zhan A. Lan W. Woo S. P. et al . (2022b). Bacteria versus fungi for predicting anthropogenic pollution in subtropical coastal sediments: Assembly process and environmental response. Ecol. Indic.134, 108484. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108484

55

Zhou J. Ning D. (2017). Stochastic community assembly: does it matter in microbial ecology? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.81, e00002-17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00002-17

56

Zou K. Wang R. Xu S. Li Z. Liu L. Li M. et al . (2021). Changes in protist communities in drainages across the Pearl River Delta under anthropogenic influence. Water Res.200, 117294. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117294

Summary

Keywords

bacteria, community assembly, diversity, fungi, latitude pattern, protists

Citation

Zhang Y, Gao X, Shao Z, Sun Y, Zhang Z, Li H and Ye J (2025) Latitude-dependent diversity and assembly processes of coastal microbial communities across multiple trophic levels in the China Seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1714451. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1714451

Received

27 September 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

15 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Qiu-Ning Liu, Yancheng Teachers University, China

Reviewed by

Wenxue Wu, Hainan University, China

Khaled Mohammed Geba, Menoufia University, Egypt

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Gao, Shao, Sun, Zhang, Li and Ye.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinqing Ye, jqye@nmemc.org.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.