Abstract

While viruses affect the flow of elements and energy at a planet-wide scale through lysis, gene transfer, and metabolic reprogramming, they are yet to be included in planetary-scale models of ecosystem function and nutrient cycling. Here, we review recent advances incorporating viruses into ocean models and ask: what barriers remain? To address these challenges, we argue for a new generation of ocean models that are fully representative of the multifaceted influences of viruses across scales of organization. We describe ways to achieve this by integration of existing models built across scales, from molecules to ecosystems and the Earth System. To accelerate these advances, we emphasize the need for systematic, intercalibrated datasets for diverse experimental virus-host systems, wider application of new technologies to monitor in situ viral infections, and new software to integrate models across scales. Resolution of viruses within multi-scale models will open the door to assessing current biological uncertainties related to the impact of viral infection on nutrient retention in the surface ocean, carbon sequestration to depth, and the sensitivity of these processes to climate change.

Introduction: viruses and their relevance in the marine ecosystem

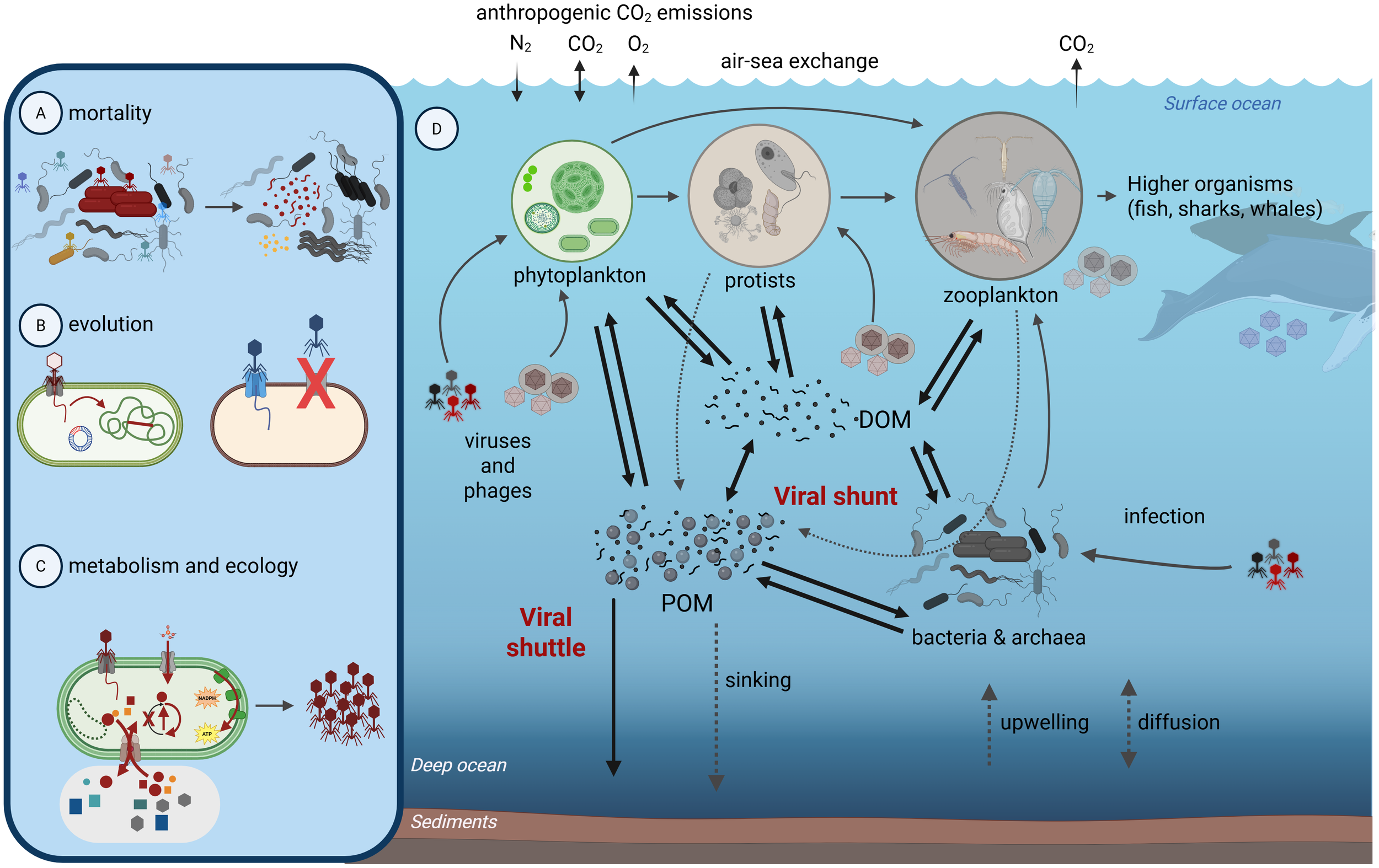

On average, one in three cells in the ocean are thought to be infected by viruses (Suttle, 2005). Viruses therefore stand at the center of marine food webs, with pre- and post-lysis impacts (Figure 1). Post-lysis impacts include mortality and the release of organic matter. Pre-lysis, viruses influence microbial taxonomic composition, genetics, and functions (Winter et al., 2010; Thingstad et al., 2014) through gene transfer, and metabolic reprogramming (Suttle, 2007; Breitbart et al., 2018; Warwick-Dugdale et al., 2019; Zimmerman et al., 2019).

Figure 1

Importance and impacts of marine viruses. Viruses impact microbial (A) diversity and abundance through mortality, (B) evolution through gene transfer and resistance, (C) metabolism and ecosystem footprints through reprogramming host cells and (D) cell lysis to have altered biomolecule pools and interactions with the environment. These cellular-scale virus-host interactions alter the larger marine microbial food web in ways that influence the fate of carbon and key nutrients in the oceans. For example, viral lysis produces mixes of dissolved (DOM) or particulate (POM) organic matter pools that are substrates for bacterial and archaeal activity, themselves subject to virus infection. If viruses shift the balance of organic matter towards DOM or POM, then this is termed the viral shunt or shuttle, respectively. This figure was made with www.Biorender.com.

Post-lysis, the ecosystem impacts of virus infection are likely large as they result in both “shunt” and “shuttle” effects on nutrient cycling (Figure 1). In the viral shunt, lysis products are consumed by microbes, which release inorganic and organic nutrients for phytoplankton and bacteria, thus accelerating the microbial loop (Azam et al., 1983) and carbon cycling in the surface ocean (Fuhrman, 1992, Fuhrman, 1999; Wilhelm and Suttle, 1999). In the viral shuttle, infected cells lyse, which results in sticky exopolymeric substances that can promote the aggregation of particles that sink to the ocean interior (Weinbauer, 2004; Burd and Jackson, 2009; Weitz and Wilhelm, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2017; Laber et al., 2018). These processes of remineralization to shunt carbon and aggregation to shuttle carbon also apply to other key elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron (Fuhrman, 1999; Jover et al., 2014; Bonnain et al., 2016). To date, marine viruses are thought to modulate the largest carbon flux in the oceans, at ~150 Gt/year (Suttle, 2007; Lara et al., 2017). Further, machine learning and statistical modeling approaches on global oceans datasets have shown that (i) virus abundances are the best predictors of global ocean carbon flux, even more so than prokaryotic or eukaryotic abundances, and (ii) within the whole virus communities specific “VIPs” can be identified as the viruses that most impact the predictive capacity for features of interest (Guidi et al., 2016; Gregory et al., 2019; Zayed et al., 2022).

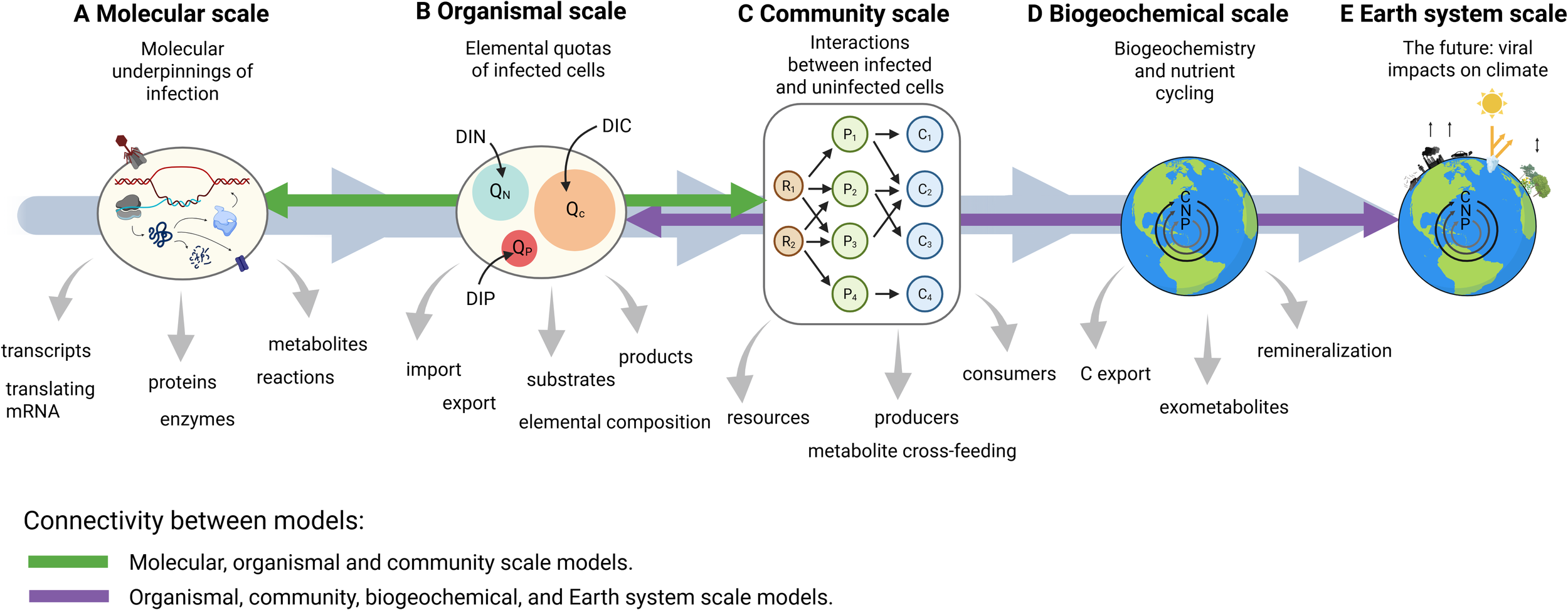

We posit that, though viruses are mainly absent from multi-scale models, they offer an ideal case study for scalable incorporation into models across vast scales, including molecular, organismal, populations or communities, biogeochemical, and planetary or Earth System scales. In Figure 2, we present a summary of the scales that we will consider here, and their connectedness in models. At the molecular scale, virus-specific models could, for example, assess how biomolecules (transcripts, proteins, metabolites) intersect with enzyme kinetics to distinguish a virally infected cell from an uninfected cell. At the organismal scale, the physiology of a virally infected cell can be modeled without necessarily understanding its complex molecular underpinnings. Community-scale models could be developed to better understand how viruses affect microbial diversity and mortality. At the biogeochemical scale, models could be developed to understand whether virally mediated exometabolite production contributes to aggregate formation and carbon export (Nissimov et al., 2018) or nutrient regeneration and retention in the surface ocean (Wilhelm and Suttle, 1999). At the Earth System scale, models could be developed to understand viral impacts on atmospheric CO2 concentration through changes in air-sea gas exchange associated with viral mediated carbon export from the surface ocean.

Figure 2

Modeling viruses across scales. Gray arrows indicate potential for connectivity across scales. Green arrows indicate existing models that include molecular processes (including viral infection). Purple arrows indicate models that are focused on organismal through to Earth system scales. A literature review listing publications with models that connect these data types is provided in Table 1.

Table 1

Examples of data types and models they are compatible with.

Purple shading indicates models that do not include either viral infection of molecular processes, orange shading indicates models that include molecular processes but not viral infection, green shading indicates models that include viral infection or molecular processes.

In the following, we review prominent models at the scales depicted in Figure 2 and provide more detailed suggestions for incorporating viruses at each scale. Here, we focus on whether viruses are considered in models across scales, remaining agnostic to modes of infection and replication strategies. We refer readers to excellent reviews of the roles of viruses in determining cell fate through programmed cell death (PCD) (Bidle, 2015; Durand et al., 2016) and replication strategy (e.g., lysogenic, temperate, and lytic) (Zimmerman et al., 2019). Furthermore, we recognize that many innovative solutions to multi-scale modeling are yet to be invented, and our goal is not to provide a concrete roadmap. Instead, our motivation is to communicate core concepts for interdisciplinary researchers working at the virus-modeling interface to build upon. We conclude by proposing several approaches to cross-scale modeling to best assess viral impacts across the vast scales in which they operate.

Molecular scale

The most common large-scale molecular simulation is flux-balance analysis (FBA), in which the metabolic network’s behavior is modeled as an optimization problem in which the flow through all reactions is assumed to have reached a quasi-steady state (Varma and Palsson, 1994; Sher et al., 2024; Scott and Segrè, 2025). FBA has been applied to many cells and organisms, for example, in the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 to better understand how it responds to environmental changes in salinity and light (Vijayakumar et al., 2020), as well as in the model algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and ocean diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum to compare mixotrophic, autotrophic, and heterotrophic growth (Boyle and Morgan, 2009; Kim et al., 2016), and Prochlorococcus to explore controls on intracellular carbon allocation and exudation (Ofaim et al., 2021). Ocean models are beginning to include FBA representations of metabolism (Casey et al., 2022; Régimbeau et al., 2022, Régimbeau et al., 2025). Beyond FBA and metabolism, “whole-cell” models have now been demonstrated to predict cellular phenotypes based on the interconnected molecular workings within the cell (Karr et al., 2012). Such models are significantly more complicated to build and run, but are also able to include much more data, and make more sophisticated predictions about cellular behavior (Macklin et al., 2020; Ahn-Horst et al., 2022).

Viral infections can be viewed as a series of molecular processes. There have been diverse studies measuring temporal dynamics of such processes, including transcript, protein, and metabolite dynamics (Ankrah et al., 2014; Doron et al., 2016; Rosenwasser et al., 2016; Howard-Varona et al., 2018, Howard-Varona et al., 2020, Howard-Varona et al., 2022, Howard-Varona et al., 2024; Waldbauer et al., 2019; Ku et al., 2020); such measurements could, in principle, be directly incorporated into the models at this scale. Such integration has not been demonstrated in marine bacteria yet. Still, a model of phage T7-infected E. coli has been shown to predict virion production from the infection’s environmental context, shed insight on the interplay between host and virus during the infection process, and generated specific hypotheses that were validated experimentally (Birch et al., 2012). The framework used to enable this infection model could be applied to modeling molecular dynamics of viral infection in marine bacterial hosts and in the context of an ocean environment (Casey et al., 2022; Régimbeau et al., 2022, Régimbeau et al., 2025). Other tools are being developed to enable metabolic simulations of diverse microbial communities (Harcombe et al., 2014; Budinich et al., 2017; Dukovski et al., 2021), and whole-cell modeling has also recently moved to the “whole-colony” scale, where simulations of hundreds to thousands of cells, each cell running the detailed E. coli model, interact with one another in a shared dynamic environment (Skalnik et al., 2023). These advances open the possibility of a marine modeling framework which brings detailed simulation of individual virions and microbes together in the same shared environment.

Organismal scale

Organismal-scale models provide mathematical representations of cellular physiology and its sensitivity to environmental conditions (Figure 2B). These models describe phenotypic behavior in a phenomenological manner, which distinguishes them from molecular-scale models discussed in the previous section. Among the simplest and widely used organismal models are the Monod model (Monod, 1949) and the Droop cell quota model (Droop, 1968). The Monod model was formulated independently in bacterial physiology (Monod, 1949), enzyme kinetics (Michaelis and Menten, 1913; Johnson and Goody, 2011), and predator foraging theory (Holling, 1959, Holling, 1965). More sophisticated representations of phytoplankton cell physiology were developed in the 1960s and 1970s (Droop, 1968; Caperon and Meyer, 1972a, CaperonMeyer, 1972b). A subset of these more sophisticated models appeared in both community scale and in ocean biogeochemical models around the year 2000 (Litchman et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2004; Passarge et al., 2006).

Models quantifying the impact of viruses on cell fitness began around the late 2000s (Bragg and Chisholm, 2008; Hellweger, 2009), and later studies explored the influence of viral infection on algal physiology (Thamatrakoln et al., 2019). More widespread application of organismal models could help establish cross-kingdom rules governing the phenotypes of virally infected cells. Progress in this direction will require the development of organismal models in concert with laboratory experiments quantifying nutrient uptake rates, photosynthesis, growth rates, and elemental composition in virally infected cells across a range of environmentally relevant conditions. Existing organismal models can readily be repurposed for such applications and could be combined with efforts to quantify traits from genomes taking inspiration from recent terrestrial modeling advances (Sokol et al., 2022).

Community scale

To better characterize biotic interactions, models explore dynamics and structure of interacting microbial communities (Figure 2C). The models at this scale trace their origins to the mathematical study of population dynamics in the 19th (Malthus, 1978) and early 20th centuries, including Lotka-Volterra (Lotka, 1920; Volterra, 1928; Wangersky, 1978). The ‘kill the winner’ hypothesis - which states that microbial diversity is enriched by viral control of otherwise dominant organisms (Winter et al., 2010) - has formed a central part of our understanding of viral control on microbial community composition. However, empirical support for the hypothesis that phages drive community composition has been questioned (Castledine and Buckling, 2024), pressing the need for measurement technologies that can be tested against contrasting model predictions. Models demonstrating that viral infection promotes diversity among bacterial prey (Thingstad and Lignell, 1997; Thingstad, 2000) typically do not resolve the intracellular stage and therefore are not directly compatible with a new class of measurement technologies that measure the host’s infected state. Fortunately, linking newly discovered virus genomes (via metagenomics) to their hosts can be predicted in silico (Roux et al., 2023) and, where carefully applied, experimentally measured at scale through proximity ligation (Shatadru et al., 2025). Thus, there is an opportunity to develop a new class of community models that can directly quantify the dynamics of hosts infected with viruses, and the impact of this on community interactions. Such models could explore the impact of viruses on the production of dissolved organic compounds (either through cell lysis or excretion) and subsequent effects on biodiversity, though whether interaction properties scale linearly from single virus-host measured traits or not is an open question.

Methods for characterizing population dynamics of host populations infected with viruses have may be informed by a range of complementary measurements. For Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, single-cell measurements of viral DNA have been detected by PCR and validated with metagenomics (Baran et al., 2018; Mruwat et al., 2021). For Emiliania huxleyi, there are host lipids with specific viral properties (glyocosphingolopids, Vardi et al., 2009) and genes coding for the enzymes that synthesize them (Nissimov et al., 2019). Importantly, virally modified host lipids are being used as biomarkers of viral infection, even distinguishing between resistant and susceptible phenotypes (Schleyer et al., 2023). Single-cell transcriptomics for diatoms (Hevroni et al., 2023) and Emiliania huxleyi (Ku et al., 2020) are also promising. Extending these approaches to more diverse experimental systems, paired with continued in situ deployment of these measurement technologies, will provide critical data for evaluating virus-explicit community models. Combining these new measurement technologies with ongoing efforts to predict infection networks from genomic data (Wang et al., 2020), potentially utilizing new knowledge of phage defense and antiphage-defense genes to pair viruses and hosts (Doron et al., 2018) or carefully applied proximity ligation data (Shatadru et al., 2025), would be a major advance toward accurate representation of infection dynamics in natural systems.

Existing models with explicit representations of viral infection have been connected with a subset of these measurement technologies. For example, simulations of viral ecotypes competing to infect Emiliania huxleyi in the North Atlantic were compared with amplicon sequences of genes coding for serine palmitoyltransferase enzymes that synthesize lipid markers of viral infection (Nissimov et al., 2019), and a similar study compared models with single-cell measurements of cyanophage DNA in the Red Sea (Maidanik et al., 2022). These are ready to be deployed more broadly. A critical link between models and data is the quantification of life-history traits, including virus adsorption rates, burst sizes, cell-specific infection rates, host and virus elemental quotas, and rates of viral lysis and decay. Many of these traits are routinely measured in culture and they directly inform model parameter values (Brussaard, 2004; Holmfeldt et al., 2016; Record et al., 2016; Duhaime et al., 2017; Talmy et al., 2019; Edwards et al., 2021; Hinson et al., 2023), though where measured for single viruses at population scales, via Viral Tag and Grow approaches, such trait values can be quite spread (Bin et al., 2022). Historically, trait modelers have identified correlated life-history traits and used this knowledge to reduce model complexity and the number of parameters that must be quantified. For example, due to strong correlations, knowing an organism’s size provides information about its nutrient uptake, respiration, and growth rates (Banse, 1976; Tang, 1995; Litchman et al., 2007). In the presence of clear, quantitative patterns connecting traits, one avoids measuring all of them, allowing models to be fully parameterized with the consequential subset of measurable traits. This dimensionality reduction provides an important foundation for representations of diversity in community models (Barton et al., 2013). Given the astonishing diversity of viruses, analysis of life-history traits across diverse organisms will be critical for establishing predictive models that quantify the impact of viral infection on microbial community composition and function.

Biogeochemical scale

The biogeochemical scale includes ocean biogeochemical models, which combine physical influences on water movement with biological conversions to predict the spatial distribution and movement of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other elements (Figure 2D) (Fennel et al., 2022; Levine et al., 2025). Biological components of modern ocean biogeochemical models were introduced in the 1940s (Riley, 1946; Riley and Bumpus, 1946), but became more complex due to advances in computing power in the 1980s and 1990s (Fasham et al., 1990). Whilst simple biologically, these models proved useful in predicting nutrient cycling on regional and global scales (Friedrichs et al., 2007). Later studies expanded to include representations of phytoplankton and zooplankton functional groups, each with distinct biogeochemical signatures (Blackford et al., 2004; Le Quéré et al., 2005). Nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are one example, but others exist, including silica-consuming diatoms and mixotrophic dinoflagellates capable of photosynthesis and phagotrophy (Ward and Follows, 2016).

At the biogeochemical scale, viruses have unquantified impacts on elemental flows. For example, infected cells release exometabolites, some of which promote particle aggregation and carbon export (Laber et al., 2018; Nissimov et al., 2018), others play a role in the remineralization of organic matter during particle sinking (Mari et al., 2017), and even cells that resist viruses likely do so in ways that alter cellular growth rates, exometabolites released, and sinking rates (Urvoy, 2025). Many biogeochemical models likely simulate the effects of viruses without explicitly resolving them. This occurs because many of the biogeochemical pathways in which viruses are implicated (Figure 1) are poorly constrained by available environmental and laboratory data, even when viral infection is not represented. For example, the shunt and shuttle hypotheses essentially partition the products of phytoplankton mortality between pools of dissolved and particulate organic matter (DOM and POM, respectively). Parameters controlling mortality and POM-DOM partitioning are, in general, very poorly understood. Biogeochemical modelers often use ad hoc assumptions that are not directly informed by data, but that lead to plausible spatial patterns of, e.g., chlorophyll and POM. To understand viral impacts on these pathways, models must be developed that encapsulate the imprint of infection on biological transformations of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements.

Some biogeochemical models have resolved viruses on limited spatial scales (Nissimov et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2022; Krishna et al., 2024), but none have simulated virus impacts on biogeochemical cycles globally. If viruses have essential roles in ocean ecology and biogeochemistry, why haven’t models been developed to quantify their impacts? A fundamental issue is that biogeochemical models quantify fluxes for deducing concentrations of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements (Levine et al., 2025). Despite vast progress in our understanding of viral function and diversity from sequencing data, very few of those data provide quantitative constraints on viral mediated elemental flow. In other words, there is a fundamental mismatch between the phenomena that are central to biogeochemical models (i.e., quantitative measurements such as rates of carbon and nitrogen fixation, carbon flux to the ocean interior, and dissolved organic matter cycling), and the nature of data that are most prevalent in shaping our understanding of viral function (semi-quantitative measurements of viral genomic composition, virus abundance, occurrence of auxiliary metabolic genes, and virally infected cells).

A major advance would be quantifying the densities of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus associated with viral particles across the ocean (Jover et al., 2014). Doing so would require knowledge of viral abundances and elemental quotas of C, N, and P. Given that large-scale genomic sequencing has mapped hundreds of thousands of DNA viruses that largely infect prokaryotes (Gregory et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2024), the following strategy might take us one step closer to foundational biogeochemical virus particle data. SYBR stains (Chen et al., 2001; Patel et al., 2007) could be used to convert relative abundance genomic data to absolute virus abundances. Experimental approaches could then be used to measure C, N, and P quotas of a subset of abundant viruses with cultivated representatives. Such an effort could also be done community-wide on a per-sample basis to compensate for the lack of cultivated representation likely to be hindering. Because such an effort would apply only to double-stranded DNA viruses for which SYBR stains work well (Holmfeldt et al., 2012), it may be prudent to limit initial model-data comparisons to systems dominated by a subset of host-virus pairs that are well represented in sample collections. More broadly, a Click or tap here to enter text.global map of viral elemental densities would open the door for a community of biogeochemical modelers to begin assessing viral activity within their models, as it would provide a directly comparable dataset.

Earth system scale

Earth System Models (ESMs) seek to place biogeochemical processes into the physicochemical context of global atmospheric and ocean circulation (Figure 2E). The principal goal of Earth system models is to understand past and future trajectories of Earth’s environment. They do so by incorporating multiple processes, including anthropogenic fossil-fuel emissions, land-atmosphere carbon exchange, sea-ice dynamics, and ocean-atmosphere carbon exchange. Models of ocean and atmosphere circulation were developed in the 1960s (Bryan, 1969; Manabe, 1969a; Manabe, 1969a) (Bryan, 1969; Manabe, 1969a; Manabe, 1969b) and were coupled with the global carbon cycle in the 2000s (Cox et al., 2000; Friedlingstein et al., 2001). Earth system models provide the foundation for the International Panel on Climate Change’s evaluation of future climate change scenarios (Zhou, 2021). There is increasing recognition that microbial activity—which includes viruses—must be incorporated into Earth system models for better climate prediction (Tagliabue, 2023; Lennon et al., 2024). Doing so would enable, for example, the assessment of the impact of virally mediated transformations of carbon on air-sea gas exchange and, ultimately, atmospheric temperature.

None of the Earth System Models that were part of the sixth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) (Séférian et al., 2020) resolved impacts of viral infection. The biogeochemical components of these models typically resolve interactions among a handful of representative phytoplankton and zooplankton communities, without a clear consensus on plankton food-web structure between ESMs (Rohr et al., 2023). Pools of DOM and POM – the pools viruses are thought to modulate – are usually regenerated to inorganic material without influence by microbial communities. Increases in model complexity tend to increase model uncertainty since each new process or pathway must be constrained. Therefore, before being included in ESMs, viral processes must be extremely well understood and constrained within models. To this end, it seems most reasonable to use community and biogeochemical models as sandboxes to test viral processes before including them in ESMs. Here, the sensitivity of global carbon fixation and export to viral infection would be an important determinant of whether their inclusion in ESMs is warranted. Once virus-explicit models have been defined at the community and biogeochemical scales, they can be included in ESMs, provided the viral impacts are shown to be appreciable drivers of carbon export and storage.

Discussion: modeling viruses across scales and linking those models

As essential drivers of ecosystem dynamics and structure (Bergh et al., 1989; Bratbak et al., 1990; Suttle et al., 1991), viruses impact Earth system functions (Locke et al., 2022) but have not been assessed in biogeochemical models. Models with viral infection have been implemented at community scales and downward, but large-scale assessment of viruses on elemental cycles and, ultimately, the Earth system, is not yet possible with any of the existing models (Figure 2). What steps can be taken to represent viruses in biogeochemical and, eventually, Earth system models? A critical advance will be to develop reliable conversions from relative viral abundance to carbon density. Mapping viral elemental inventories will provide datasets immediately comparable to biogeochemical and Earth system model output. Additional data for model parameterization will come from ecologically and biogeochemically relevant laboratory experimental systems. Existing efforts to quantify life-history traits among these systems provide direct constraints on model parameter values. Expanding these efforts to diverse taxa and across environmental gradients in light, temperature, and nutrient availability, as well as establishing more scalable approaches to capture these trait values, would open the door to applying the trait approach to model viruses in a biogeochemical context. New technologies monitoring viral infection rates at the single cell level using DNA (Carlson et al., 2022), transcripts (Ku et al., 2020; Hevroni et al., 2023), and lipids (Vardi et al., 2009) are critical links from lab to ocean, particularly when considering the continuum of infection possibilities and likely high preponderance of suboptimal infections (Correa et al., 2021). These advances open the door to constraining the envelope of possible viral impacts on population dynamics and material cycling on regional and global scales. Still, their insight will be limited to phenotypic properties and a subset of new data describing virus biogeography and composition. Viral impacts on host metabolism occur at subcellular scales, and new modeling paradigms will be necessary to assess these impacts and leverage the expanded set of molecular data now available.

On the modeling side, inherent trade-offs between expanding model complexity and tractability need to be weighed. For example, modeling the tens of thousands of molecular-scale processes at the biogeochemical scale, where the most biologically sophisticated models describe hundreds of simulated organisms (Dutkiewicz et al., 2020), is computationally intractable. Moreover, each new parameter introduced into a model must be quantified, and uncertainty in its value can propagate throughout the model’s predictions. At the molecular scale, whole-cell models have been shown to predict growth rates better, suggesting that greater complexity can lead to better predictive power (Sanghvi et al., 2013). However, increased complexity and realism in biogeochemical models do not necessarily lead to performance gains over simpler models (Kwiatkowski et al., 2014), and within simpler models, there is uncertainty about how best to formulate simple planktonic ecosystem descriptions (Rohr et al., 2023).

One way forward might be to distill molecular-scale (i.e., genomic) complexity into fundamental traits that could be handed off to larger-scale models. Examples in terrestrial modeling are starting to appear and include growing lists of genome-inferable traits (e.g. Sokol et al., 2022). The trait approach has arguably been the most successful way to represent biological complexity and diversity in community and biogeochemical models, and we anticipate that extending the trait approach to molecular scales (Mock et al., 2016) will enable representation of virally infected cell metabolism and physiology in models without exploding model uncertainty. This effort will entail the broader application of molecular modeling approaches across diverse host-virus systems, along with meta-analyses of these models’ predictions. Just as a trait modeler looks for patterns in microbial growth rates and nutrient affinities, modelers will need to explore patterns in metabolic and physiological rates to establish generalities among diverse organisms infected with viruses. If reliable patterns can be established, this will help limit the number of new biological parameters required to embed molecular processes within models, thereby reducing the uncertainty introduced into the model with each new process.

Finally, there are also pragmatic challenges to multi-scale modeling “handoffs” between scales. For example, implementing molecular-scale models in software will require significant integration, not only across time and length scales but also across the modeling approaches used at each scale. One codebase developed to address this problem is Vivarium, a systems biology software for multi-scale connectedness (Agmon et al., 2022). Vivarium facilitates the integration of independently created models, enabling each model to be encapsulated and linked into a composite model via shared input and output streams. Thus, models at different scales serve as modules that provide inputs and outputs for passing between scales. In an ocean context, this might mean, for example, that rates of nutrient uptake and viral-mediated lysis are determined from a subcomponent describing the molecular sensitivity of these processes to ambient light, temperature, and nutrient conditions. Such an endeavor would be inherently interdisciplinary and require modelers to ‘trust’ models at different scales. It may also require a fundamental rebuilding of existing modeling paradigms. Rather than working from the ‘top down’; modifying models on an ad hoc basis, a new system may need to be built from the bottom up and designed to explicitly consider compatibility between scales as a fundamental requirement of the model implementation.

Taken together, there are many obstacles to be overcome in modeling virus impacts from the molecular to the planetary scale. However, it is critical and now timely that life scientists blaze ways forward to bring viruses to light as the nanoscale entities that conduct many of the Earth’s most beautiful biological symphonies. We hope this review provides some inspiration and direction for those seeking it.

Statements

Author contributions

DT: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH-V: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DE: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. DT recognizes support from the Simons Foundation (690671) and the National Science Foundation (OCE-2023680). MS and CH-V acknowledge support from the NSF EMERGE Biology Integration Institute (#29640), DOE Systems Biology (DE-SC0023307), and the NSF C-CoMP Science and Technology Center (OCE-2019589). MC acknowledges support from the NSF C-CoMP Science and Technology Center (OCE-2019589), and DE acknowledges support from the European Union (GA#101059915 -BIOcean5D).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Agmon E. Spangler R. K. Skalnik C. J. Poole W. Peirce S. M. Morrison J. H. et al . (2022). Vivarium: An interface and engine for integrative multiscale modeling in computational biology. Bioinformatics38, 1972–1979. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac049

2

Ahn-Horst T. A. Mille L. S. Sun G. Morrison J. H. Covert M. W. (2022). An expanded whole-cell model of E. coli links cellular physiology with mechanisms of growth rate control. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl.8. doi: 10.1038/s41540-022-00242-9

3

Ankrah N. Y. D. May A. L. Middleton J. L. Jones D. R. Hadden M. K. Gooding J. R et al . (2014). Phage infection of an environmentally relevant marine bacterium alters host metabolism and lysate composition. ISME J.8, 1089–1100. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.216

4

Azam F. Fenchel T. Field J. G. Gray J. S. Meyer-Reil L. A. Thingstad F. (1983). The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series10, 257–263. doi: 10.3354/meps010257

5

Banse K. (1976). Rates of growth, respiration and photosynthesis of unicellular algae as related to cell size - a review. J. Phycol.12, 135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1976.tb00490.x

6

Baran N. Goldin S. Maidanik I. Lindell D. (2018). Quantification of diverse virus populations in the environment using the polony method. Nat. Microbiol.3, 62–72. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0045-y

7

Barange M. Butenschön M. Yool A. Beaumont N. Fernandes J. A. Martin A. P. et al . (2017). The cost of reducing the North Atlantic Ocean biological carbon pump. Front. Mar. Sci.3. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2016.00290

8

Barton A. D. Pershing A. J. Litchman E. Record N. R. Edwards K. F. Finkel Z. V. et al . (2013). The biogeography of marine plankton traits. Ecol. Lett.16, 522–534. doi: 10.1111/ele.12063

9

Bergh O. Borsheim K. Y. Bratbak G. Heldal M. (1989). High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments. Nature340, 467–468. doi: 10.1038/340467a0

10

Bidle K. D. (2015). The molecular ecophysiology of programmed cell death in marine phytoplankton. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci.7, 341–375. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-MARINE-010213-135014/CITE/REFWORKS

11

Bin J. H. Chittick L. Li Y.-F. Zablocki O. Sanderson C. M. Carrillo A. et al . (2022). Viral tag and grow: a scalable approach to capture and characterize infectious virus–host pairs. ISME Commun.2, 12. doi: 10.1038/s43705-022-00093-9

12

Birch E. W. Ruggero N. A. Covert M. W. (2012). Determining host metabolic limitations on viral replication via integrated modeling and experimental perturbation. PloS Comput. Biol.8, e1002746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002746

13

Blackford J. C. Allen J. I. Gilbert F. J. (2004). Ecosystem dynamics at six contrasting sites: A generic modelling study. J. Mar. Syst.52, 191–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2004.02.004

14

Bonachela J. A. Klausmeier C. A. Edwards K. F. Litchman E. Levin S. A. (2016). The role of phytoplankton diversity in the emergent oceanic stoichiometry. J. Plankt. Res.38, 1021–1035. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbv087

15

Bonnain C. Breitbart M. Buck K. N. (2016). The Ferrojan horse hypothesis: Iron-virus interactions in the ocean. Front. Mar. Sci.3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00082

16

Boyle N. R. Morgan J. A. (2009). Flux balance analysis of primary metabolism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BMC Syst. Biol.3. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-4

17

Bragg J. G. Chisholm S. W. (2008). Modeling the fitness consequences of a cyanophage-encoded photosynthesis gene. PloS One3, e3550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003550

18

Bratbak G. Heldal M. Norland S. Frede Thingstad T. (1990). Viruses as partners in spring bloom microbial trophodynamics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.56, 1400–1405. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1400-1405.1990

19

Breitbart M. Bonnain C. Malki K. Sawaya N. A. (2018). Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm. Nat. Microbiol.3, 754–766. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0166-y

20

Brussaard C. P. D. (2004). Viral control of phytoplankton populations - A review. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.51, 125–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00537.x

21

Bryan K. (1969). Climate and the ocean circulation III. ocean. Model. Mon. Weath. Rev.97, 806–827. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1969)097<0806:CATOC>2.3.CO;2

22

Budinich M. Bourdon J. Larhlimi A. Eveillard D. (2017). A multi-objective constraint-based approach for modeling genome-scale microbial ecosystems. PloS One12, e0171744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171744

23

Burd A. B. Jackson G. A. (2009). Particle aggregation. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci.1, 65–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163904

24

Button D. K. (1985). Kinetics of nutrient-limited transport and microbial growth. Microbiol. Rev.49 (3), 270–297.

25

Caperon J. Meyer J. (1972a). Nitrogen-limited growth of marine phytoplanktonmH. Uptake kinetics and their role in nutrient limited growth of phytoplankton. Deep. Sea. Res. Oceanogr. Abstr.19, 619–632. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(72)90090-3

26

Caperon J. Meyer J. (1972b). Nitrogen-limited growth of marine phytoplankton-I. Changes in population characteristics with steady-state growth rate. Deep. Sea. Res. Oceanogr. Abstr.19, 618. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(72)90089-7

27

Carlson M. C. G. Ribalet F. Maidanik I. Durham B. P. Hulata Y. Ferrón S. et al . (2022). Viruses affect picocyanobacterial abundance and biogeography in the North Pacific Ocean. Nat. Microbiol.7, 570–580. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01088-x

28

Casey J. R. Boiteau R. M. Engqvist M. K. M. Finkel Z. V. Li G. Liefer J. et al . (2022). Basin-scale biogeography of marine phytoplankton reflects cellular-scale optimization of metabolism and physiology. Sci. Adv.8, 4930. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4477905

29

Castledine M. Buckling A. (2024). Critically evaluating the relative importance of phage in shaping microbial community composition. Trends Microbiol32, 957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2024.02.014

30

Chen F. Lu J. R. Binder B. J. Liu Y. C. Hodson R. E. (2001). Application of digital image analysis and flow cytometry to enumerate marine viruses stained with SYBR Gold. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.67, 539–545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.539-545.2001

31

Clark J. R. Daines S. J. Lenton T. M. Watson A. J. Williams H. T. P. (2011). Individual-based modelling of adaptation in marine microbial populations using genetically defined physiological parameters. Ecol. Mod.222, 3823–3837. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.10.001

32

Coles V. J. Stukel M. R. Brooks M. T. Burd A. Crump B. C. Moran M. A. et al . (2017). Ocean biogeochemistry modeled with emergent trait-based genomics Downloaded from. Science358, 1149–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5712

33

Connolly S. R. Keith S. A. Colwell R. K. Rahbek C. (2017). Process, mechanism, and modeling in macroecology. Trends Ecol. Evol.32, 835–844. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.08.011

34

Correa A. M. S. Howard-Varona C. Coy S. R. Buchan A. Sullivan M. B. Weitz J. S. (2021). Revisiting the rules of life for viruses of microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 501–513. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00530-x

35

Cox P. Betts R. Jones C. Spall S. Totterdell I. (2000). Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature408, 184–187. doi: 10.1038/35041539

36

Daines S. J. Clark J. R. Lenton T. M. (2014). Multiple environmental controls on phytoplankton growth strategies determine adaptive responses of the N:P ratio. Ecol. Lett.17, 414–425. doi: 10.1111/ele.12239

37

Doron S. Fedida A. Hernndez-Prieto M. A. Sabehi G. Karunker I. Stazic D. et al . (2016). Transcriptome dynamics of a broad host-range cyanophage and its hosts. ISME J.10, 1437–1455. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.210

38

Doron S. Melamed S. Ofir G. Leavitt A. Lopatina A. Keren M. et al . (2018). Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science359, eaar4120. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4120

39

Droop M. R. (1968). Vitamin B12 and marine ecology. IV. The kinetics of uptake, growth and inhibition in Monochrysis lutheri. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. Unt. Kingd.48, 689–733. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400019238

40

Duhaime M. B. Solonenko N. Roux S. Verberkmoes N. C. Wichels A. Sullivan M. B. (2017). Comparative omics and trait analyses of marine Pseudoalteromonas phages advance the phage OTU concept. Front. Microbiol.8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01241

41

Dukovski I. Bajić D. Chacón J. M. Quintin M. Vila J. C. C. Sulheim S. et al . (2021). A metabolic modeling platform for the computation of microbial ecosystems in time and space (COMETS). Nat. Protoc.16, 5030–5082. doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00593-3

42

Durand P. M. Sym S. Michod R. E. (2016). Programmed cell death and complexity in microbial systems. Curr. Biol.26, R587–R593. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.057

43

Dutkiewicz S. Cermeno P. Jahn O. Follows M. J. Hickman A. A. Taniguchi D. A. A. et al . (2020). Dimensions of marine phytoplankton diversity. Biogeosciences17, 609–634. doi: 10.5194/bg-17-609-2020

44

Edwards K. F. Steward G. F. Schvarcz C. R. (2021). Making sense of virus size and the tradeoffs shaping viral fitness. Ecol. Lett.24, 363–373. doi: 10.1111/ele.13630

45

Fasham M. Ducklow H. McKelvie S. (1990). A nitrogen-based model of plankton dynamics in the oceanic mixed layer. J. Mar. Res.48, 591–639. doi: 10.1357/002224090784984678

46

Fennel K. Mattern J. P. Doney S. C. Bopp L. Moore A. M. Wang B. et al . (2022). Ocean biogeochemical modelling. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers2. doi: 10.1038/s43586-022-00154-2

47

Flato G. M. (2011). Earth system models: An overview. Wiley. Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change2, 783–800. doi: 10.1002/wcc.148

48

Forterre P. (2013). The virocell concept and environmental microbiology The great virus comeback. ISME J.7, 233–236. doi: 10.1038/ismej

49

Friedlingstein P. Bopp L. Ciais P. Dufresne J. L. Fairhead L. LeTreut H. et al . (2001). Positive feedback between future climate change and the carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett.28, 1543–1546. doi: 10.1029/2000GL012015

50

Friedrichs M. A. M. Dusenberry J. A. Anderson L. A. Armstrong R. A. Chai F. Christian J. R. et al . (2007). Assessment of skill and portability in regional marine biogeochemical models: Role of multiple planktonic groups. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean.112, C08001. doi: 10.1029/2006JC003852

51

Fu H. Uchimiya M. Gore J. Moran M. A. (2020). Ecological drivers of bacterial community assembly in synthetic phycospheres. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences117, 3656–3662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917265117/-/DCSupplemental

52

Fuhrman J. (1992). “ Bacterioplankton roles in cycling of organic matter: the microbial food web,” in Primary productivity and biogeochemical cycles in the sea (Boston, MA: Springer US), 361–383. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0762-2_20

53

Fuhrman J. A. (1999). Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature399, 541–548. doi: 10.1038/21119

54

Geider R. MacIntyre H. L. Kana T. M. (1998). A dynamic regulatory model of phytoplanktonic acclimation to light, nutrients, and temperature. Limnol. Oceanogr.43, 679–694. doi: 10.4319/lo.1998.43.4.0679

55

Gregory A. C. Zayed A. A. Conceição-Neto N. Temperton B. Bolduc B. Alberti A. et al . (2019). Marine DNA viral macro- and microdiversity from pole to pole. Cell177, 1109–1123.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.040

56

Guidi L. Chaffron S. Bittner L. Eveillard D. Larhlimi A. Roux S. et al . (2016). Plankton networks driving carbon export in the oligotrophic ocean. Nature532, 465–470. doi: 10.1038/nature16942

57

Harcombe W. R. Riehl W. J. Dukovski I. Granger B. R. Betts A. Lang A. H. et al . (2014). Metabolic resource allocation in individual microbes determines ecosystem interactions and spatial dynamics. Cell Rep.7, 1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.070

58

Hellweger F. L. (2009). Carrying photosynthesis genes increases ecological fitness of cyanophage in silico. Environ. Microbiol.11, 1386–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01866.x

59

Hevroni G. Vincent F. Ku|| C. Sheyn U. Vardi A. (2023). Daily turnover of active giant virus infection during algal blooms revealed by single-cell transcriptomics. Sci. Adv.9, eadf7971. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adf797

60

Hinson A. Papoulis S. Fiet L. Knight M. Cho P. Szeltner B. et al . (2023). A model of algal-virus population dynamics reveals underlying controls on material transfer. Limnol. Oceanogr.68, 165–180. doi: 10.1002/lno.12256

61

Holling C. S. (1959). The components of predation as revealed by a study of small-mammal predation of the European Pine Sawfly. Can. Entomol.91, 293–320. doi: 10.4039/Ent91293-5

62

Holling C. S. (1965). The functional response of predators to prey density and its role in mimicry and population regulation. Memoirs. Entomol. Soc. CA.97, 5–60. doi: 10.4039/entm9745fv

63

Holmfeldt K. Odić D. Sullivan M. B. Middelboe M. Riemann L. (2012). Cultivated single-stranded DNA phages that infect marine bacteroidetes prove difficult to detect with DNA-binding stains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.78, 892–894. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06580-11

64

Holmfeldt K. Solonenko N. Howard-Varona C. Moreno M. Malmstrom R. R. Blow M. J. et al . (2016). Large-scale maps of variable infection efficiencies in aquatic Bacteroidetes phage-host model systems. Environ. Microbiol.18, 3949–3961. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13392

65

Howard-Varona C. Hargreaves K. R. Solonenko N. E. Markillie L. M. White R. A. Brewer H. M. et al . (2018). Multiple mechanisms drive phage infection efficiency in nearly identical hosts. ISME J.12, 1605–1618. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0099-8

66

Howard-Varona C. Lindback M. M. Bastien G. E. Solonenko N. Zayed A. A. Jang H. B. et al . (2020). Phage-specific metabolic reprogramming of virocells. ISME J.14, 881–895. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0580-z

67

Howard-Varona C. Roux S. Bowen B. P. Silva L. P. Lau R. Schwenck S. M. et al . (2022). Protist impacts on marine cyanovirocell metabolism. ISME Commun.2. doi: 10.1038/s43705-022-00169-6

68

Howard-Varona C. Lindbackb M. M. Fudymac J. D. Krongauzd A. Solonenkoa N. E. Zayeda A. A. et al . (2024). Environment-specific virocell metabolic reprogramming Ecology of nutrient-limited, phage-infected cells. ISME J.18, wrae055. doi: 10.1093/ismejo/wrae055

69

Inomura K. Omta A. W. Talmy D. Bragg J. Deutsch C. Follows M. J. (2020). A mechanistic model of macromolecular allocation, elemental stoichiometry, and growth rate in phytoplankton. Front. Microbiol.11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00086

70

Johnson K. A. Goody R. S. (2011). The original Michaelis constant: Translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten Paper. Biochemistry50, 8264–8269. doi: 10.1021/bi201284u

71

Jover L. F. Effler T. C. Buchan A. Wilhelm S. W. Weitz J. S. (2014). The elemental composition of virus particles: Implications for marine biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.12, 519–528. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3289

72

Karr J. R. Sanghvi J. C. MacKlin D. N. Gutschow M. V. Jacobs J. M. Bolival B. et al . (2012). A whole-cell computational model predicts phenotype from genotype. Cell150, 389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.044

73

Kim J. Fabris M. Baart G. Kim M. K. Goossens A. Vyverman W. et al . (2016). Flux balance analysis of primary metabolism in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant J.85, 161–176. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13081

74

Koelling J. Atamanchuk D. Wallace D. W. R. Karstensen J. (2023). Decadal variability of oxygen uptake, export, and storage in the Labrador Sea from observations and CMIP6 models. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1202299

75

Krishna S. Peterson V. Listmann L. Hinners J. (2024). Interactive effects of viral lysis and warming in a coastal ocean identified from an idealized ecosystem model. Ecol. Mod.487. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110550

76

Ku C. Sheyn U. Sebé-Pedrós A. Ben-Dor S. Schatz D. Tanay A. et al . (2020). A single-cell view on alga-virus interactions reveals sequential transcriptional programs and infection states. Sci. Adv.6, eava4137. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba41

77

Kwiatkowski L. Yool A. Allen J. I. Anderson T. R. Barciela R. Buitenhuis E. T. et al . (2014). IMarNet: An ocean biogeochemistry model intercomparison project within a common physical ocean modelling framework. Biogeosciences11, 7291–7304. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-7291-2014

78

Kwon E. Y. Primeau F. Sarmiento J. L. (2009). The impact of remineralization depth on the air-sea carbon balance. Nat. Geosci.2, 630–635. doi: 10.1038/ngeo612

79

Laber C. P. Hunter J. E. Carvalho F. Collins J. R. Hunter E. J. Schieler B. M. et al . (2018). Coccolithovirus facilitation of carbon export in the North Atlantic. Nat. Microbiol.3, 537–547. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0128-4

80

Lara E. Vaqué D. Sà E. L. Boras J. A. Gomes A. Borrull E. et al . (2017). Unveiling the role and life strategies of viruses from the surface to the dark ocean. Sci. Adv.3, e1602565. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.160256

81

Lauderdale J. M. Dutkiewicz S. Williams R. G. Follows M. J. (2016). Quantifying the drivers of ocean-atmosphere CO2 fluxes. Global Biogeochem. Cycle.30, 983–999. doi: 10.1002/2016GB005400

82

Lennon J. T. Abramoff R. Z. Allison S. D. Burckhardt R. M. DeAngelis K. M. Dunne J. P. et al . (2024). Priorities, opportunities, and challenges for integrating microorganisms into Earth system models for climate change prediction. mBio15, e00455–24. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00455-24

83

Le Quéré C. Harrison S. P. Prentice I. C. Buitenhuis E. T. Aumont O. Bopp L. et al . (2005). Ecosystem dynamics based on plankton functional types for global ocean biogeochemistry models. Glob. Chang. Biol.11, 2016–2040. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2486.2005.1004.X

84

Letscher R. T. Moore J. K. Teng Y. C. Primeau F. (2015). Variable C: N: P stoichiometry of dissolved organic matter cycling in the Community Earth System Model. Biogeosciences12, 209–221. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-209-2015

85

Levine N. M. Alexander H. Bertrand E. M. Coles V. J. Dutkiewicz S. Leles S. G. et al . (2025). Microbial ecology to ocean carbon cycling: from genomes to numerical models. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci.53, 595–624. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-EARTH-040523-020630

86

Litchman E. Klausmeier C. A. Bossard P. (2004). Phytoplankton nutrient competition under dynamic light regimes. Limnol. Oceanogr.49, 1457–1462. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.4_part_2.1457

87

Litchman E. Klausmeier C. A. Miller J. R. Schofield O. M. Falkowski P. G. (2006). Multi-nutrient, multi-group model of present and future oceanic phytoplankton communities. Biogeosciences3, 585–606. doi: 10.5194/bg-3-585-2006

88

Litchman E. Klausmeier C. A. Schofield O. M. Falkowski P. G. (2007). The role of functional traits and trade-offs in structuring phytoplankton communities: Scaling from cellular to ecosystem level. Ecol. Lett.10, 1170–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01117.x

89

Locke H. Bidle K. D. Thamatrakoln K. Johns C. T. Bonachela J. A. Ferrell B. D. et al . (2022). “ Marine viruses and climate change: Virioplankton, the carbon cycle, and our future ocean,” in Advances in virus research ( Academic Press Inc), 67–146. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2022.09.001

90

Lotka A. J. (1920). Undamped oscillations derived from the law of mass action. J. Am. Chem. Soc.42, 1595–1599. doi: 10.1021/JA01453A010

91

Macklin D. N. Ahn-Horst T. A. Choi H. Ruggero N. A. Carrera J. Mason J. C. et al . (2020). Simultaneous cross-evaluation of heterogeneous E. coli datasets via mechanistic simulation. Science369, eaav3751. doi: 10.1126/science.aav3751

92

Maidanik I. Kirzner S. Pekarski I. Arsenieff L. Tahan R. Carlson M. C. G. et al . (2022). Cyanophages from a less virulent clade dominate over their sister clade in global oceans. ISME J.16, 2169–2180. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01259-y

93

Maltby L. (2001). “ Linking individual-level responses and population-level consequences,” in Ecological variability: separating natural from anthropogenic causes. Eds. BairdD. J.BurtonG. A. ( Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (Setac). doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3046

94

Malthus (1978). An essay on the principle of population (London, UK: J. Johnson).

95

Manabe S. (1969a). Climate and the ocean circulation: I. The atmospheric circulation and the hydrology of the earth’s surface. Mon. Weath. Rev.97, 739–774. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1969)097<0739:CATOC>2.3.CO;2

96

Manabe S. (1969b). Climate and the ocean circulation: II. The atmospheric circulation and the effect of heat transfer by ocean currents. Mon. Weath. Rev.97, 1. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1969)097<0775:CATOC>2.3.CO;2

97

Mari X. Passow U. Migon C. Burd A. B. Legendre L. (2017). Transparent exopolymer particles: Effects on carbon cycling in the ocean. Prog. Oceanogr.151, 13–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2016.11.002

98

McCain J. S. P. Tagliabue A. Susko E. Achterberg E. P. Allen A. E. Bertrand E. M. (2021). Cellular costs underpin micronutrient limitation in phytoplankton. Sci. Adv.7, eabg6501. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg6501

99

Michaelis L. Menten M. L. (1913). Die kinetik der invertinwirkung. Biochem. Z.352, 333–369. doi: 10.1021/bi201284u

100

Miki T. Yokokawa T. Nagata T. Yamamura N. (2008). Immigration of prokaryotes to local environments enhances remineralization efficiency of sinking particles: A metacommunity model. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.366, 1–14. doi: 10.3354/meps07597

101

Mock T. Daines S. J. Geider R. Collins S. Metodiev M. Millar A. J. et al . (2016). Bridging the gap between omics and earth system science to better understand how environmental change impacts marine microbes. Glob. Chang. Biol.22, 61–75. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12983

102

Mongin M. Nelson D. M. Pondaven P. Tréguer P. (2006). Simulation of upper-ocean biogeochemistry with a flexible-composition phytoplankton model: C, N and Si cycling and Fe limitation in the Southern Ocean. Deep. Sea. Res. 2. Top. Stud. Oceanogr.53, 601–619. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.01.021

103

Monod J. (1949). The growth of bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.3, 371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.03.100149.002103

104

Moore J. K. Doney S. C. Lindsay K. (2004). Upper ocean ecosystem dynamics and iron cycling in a global three-dimensional model. Global Biogeochem. Cycle.18, 1–21. doi: 10.1029/2004GB002220

105

Mruwat N. Carlson M. C. G. Goldin S. Ribalet F. Kirzner S. Hulata Y. et al . (2021). A single-cell polony method reveals low levels of infected Prochlorococcus in oligotrophic waters despite high cyanophage abundances. ISME J.15, 41–54. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00752-6

106

Nissimov J. I. Talmy D. Haramaty L. Fredricks H. F. Zelzion E. Knowles B. et al . (2019). Biochemical diversity of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis as a driver of Coccolithovirus competitive ecology. Environ. Microbiol.21, 2182–2197. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14633

107

Nissimov J. I. Vandzura R. Johns C. T. Natale F. Haramaty L. Bidle K. D. (2018). Dynamics of transparent exopolymer particle production and aggregation during viral infection of the coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi. Environ. Microbiol.20, 2880–2897. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14261

108

Ofaim S. Sulheim S. Almaas E. Sher D. Segrè D. (2021). Dynamic allocation of carbon storage and nutrient-dependent exudation in a revised genome-scale model of prochlorococcus. Front. Genet.12. doi: 10.3389/FGENE.2021.586293/PDF

109

Passarge J. Hol S. Escher M. Huisman J. (2006). Competition for nutrients and light: Stable coexistence, alternative stable states, or competitive exclusion? Ecol. Monogr.76, 57–72. doi: 10.1890/04-1824

110

Patel A. Noble R. T. Steele J. A. Schwalbach M. S. Hewson I. Fuhrman J. A. (2007). Virus and prokaryote enumeration from planktonic aquatic environments by epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I. Nat. Protoc.2, 269–276. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.6

111

Record N. R. Talmy D. Våge S. (2016). Quantifying tradeoffs for marine viruses. Front. Mar. Sci.3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00251

112

Reed D. C. Algar C. K. Huber J. A. Dick G. J. (2014). Gene-centric approach to integrating environmental genomics and biogeochemical models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111, 1879–1884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313713111

113

Régimbeau A. Aumont O. Bowler C. Guidi L. Jackson G. A. Karsenti E. et al . (2025). Unveiling the link between phytoplankton molecular physiology and biogeochemical cycling via genome-scale modeling. Sci. Adv.11, eadq3593. doi: 10.1126/SCIADV.ADQ3593

114

Régimbeau A. Budinich M. Larhlimi A. Pierella Karlusich J. J. Aumont O. Memery L. et al . (2022). Contribution of genome-scale metabolic modelling to niche theory. Ecol. Lett.25, 1352–1364. doi: 10.1111/ele.13954

115

Riley G. A. (1946). Factors controlling phytoplankton populations on Georges Bank. J. Mar. Res.6, 54–73.

116

Riley G. A. Bumpus D. F. (1946). Phytoplankton-zooplankton relationships on georges bank. J. Mar. Res.6, 33–47. Available online at: www.journalofmarineresearch.org.

117

Rohr T. Richardson A. J. Lenton A. Chamberlain M. A. Shadwick E. H. (2023). Zooplankton grazing is the largest source of uncertainty for marine carbon cycling in CMIP6 models. Commun. Earth Environ.4. doi: 10.1038/s43247-023-00871-w

118

Rosenwasser S. Ziv C. van Creveld S. G. Vardi A. (2016). Virocell metabolism: metabolic innovations during host–virus interactions in the ocean. Trends Microbiol.24, 821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.006

119

Ross O. N. Geider R. J. (2009). New cell-based model of photosynthesis and photo-acclimation: accumulation and mobilisation of energy reserves in phytoplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.383, 53–71. doi: 10.3354/meps07961

120

Roux S. Camargo A. P. Coutinho F. H. Dabdoub S. M. Dutilh B. E. Nayfach S. et al . (2023). iPHoP: An integrated machine learning framework to maximize host prediction for metagenome-derived viruses of archaea and bacteria. PloS Biol.21, e3002083. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3002083

121

Sanghvi J. C. Regot S. Carrasco S. Karr J. R. Gutschow M. V. Bolival B. et al . (2013). Accelerated discovery via a whole-cell model. Nat. Methods10, 1192–1195. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2724

122

Schleyer G. Kuhlisch C. Ziv C. Ben-Dor S. Malitsky S. Schatz D. et al . (2023). Lipid biomarkers for algal resistance to viral infection in the ocean. PNAS120, e2217121120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217121120

123

Schlogelhofer H. L. Peaudecerf F. J. Bunbury F. Whitehouse M. J. Foster R. A. Smith A. G. et al . (2021). Combining SIMS and mechanistic modelling to reveal nutrient kinetics in an algal-bacterial mutualism. PloS One16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251643

124

Scott H. Segrè D. (2025). Metabolic flux modeling in marine ecosystems. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci.17, 593–620. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-MARINE-032123-033718

125

Séférian R. Berthet S. Yool A. Palmiéri J. Bopp L. Tagliabue A. et al . (2020). Tracking improvement in simulated marine biogeochemistry between CMIP5 and CMIP6. Curr. Clim. Change Rep.6, 95–119. doi: 10.1007/s40641-020-00160-0

126

Shatadru R. N. Solonenko N. E. Sun C. L. Sullivan M. B. (2025). Synthetic community Hi-C benchmarking provides a baseline for virus-host inferences. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2025.02.12.637985

127

Sher D. Segrè D. Follows M. J. (2024). Quantitative principles of microbial metabolism shared across scales. Nat. Microbiol.9, 1940–1953. doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01764-0

128

Skalnik C. J. Cheah S. Y. Yang M. Y. Wolff M. B. Spangler R. K. Talman L. et al . (2023). Whole-cell modeling of E. coli colonies enables quantification of single-cell heterogeneity in antibiotic responses. PloS Comput. Biol.19, e1011232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011232

129

Sokol N. W. Slessarev E. Marschmann G. L. Nicolas A. Blazewicz S. J. Brodie E. L. et al . (2022). Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.20, 415–430. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00695-z

130

Stock C. A. Dunne J. P. Fan S. Ginoux P. John J. Krasting J. P. et al . (2020). Ocean biogeochemistry in GFDL’s earth system model 4.1 and its response to increasing atmospheric CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst.12, e2019MS002043. doi: 10.1029/2019MS002043

131

Sullivan M. B. Weitz J. S. Wilhelm S. (2017). Viral ecology comes of age. Environ. Microbiol. Rep.9, 33–35. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12504

132

Suttle C. A. (2005). Viruses in the sea. Nature437, 356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160

133

Suttle C. A. (2007). Marine viruses - Major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.5, 801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750

134

Suttle C. A. Chan A. M. Cottrell M. T. (1991). Use of ultrafiltration to isolate viruses from seawater which are pathogens of marine phytoplanktont. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.57, 721–726. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.3.721-726.1991

135

Tagliabue A. (2023). Oceans are hugely complex”: modelling marine microbes is key to climate forecasts. Naure623, 250–252. doi: 10.1101/2023.06.27.546656

136

Talmy D. Beckett S. J. Zhang A. B. Taniguchi D. A. A. Weitz J. S. Follows M. J. (2019). Contrasting controls on microzooplankton grazing and viral infection of microbial prey. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00182

137

Tang E. P. Y. (1995). The allometry of algal growth rates. J. Plankt. Res.17, 1325–1335. doi: 10.1093/PLANKT/17.6.1325

138

Teng Y. C. Primeau F. W. Moore J. K. Lomas M. W. Martiny A. C. (2014). Global-scale variations of the ratios of carbon to phosphorus in exported marine organic matter. Nat. Geosci.7, 895–898. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2303

139

Thamatrakoln K. Talmy D. Haramaty L. Maniscalco C. Latham J. R. Knowles B. et al . (2019). Light regulation of coccolithophore host–virus interactions. New Phytol.221, 1289–1302. doi: 10.1111/nph.15459

140

Thingstad T. F. (2000). Elements of a theory for the mechanisms controlling abundance, diversity, and biogeochemical role of lytic bacterial viruses in aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr.45, 1320–1328. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.6.1320

141

Thingstad T. F. Havskum H. Zweifel U. L. Berdalet E. Sala M. M. Peters F. et al . (2007). Ability of a “minimum” microbial food web model to reproduce response patterns observed in mesocosms manipulated with N and P, glucose, and Si. J. Mar. Syst.64, 15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.02.009

142

Thingstad T. F. Lignell R. (1997). Theoretical models for the control of bacterial growth rate, abundance, diversity and carbon demand. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.13, 19–27. doi: 10.3354/AME013019

143

Thingstad T. F. Vage S. Storesund J. E. Sandaa R. A. Giske J. (2014). A theoretical analysis of how strain-specific viruses can control microbial species diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111, 7813–7818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400909111

144

Tian F. Wainaina J. M. Howard-Varona C. Domínguez-Huerta G. Bolduc B. Gazitúa M. C. et al . (2024). Prokaryotic-virus-encoded auxiliary metabolic genes throughout the global oceans. . Microbiome12, 159. doi: 10.1186/S40168-024-01876-Z

145

Urvoy M. (2025). Phage resistance mutations in a marine bacterium impact biogeochemically-relevant cellular processesNat Microbiol ( in press).

146

Vardi A. Van Mooy B. A. S. Fredricks H. F. Popendorf K. J. Ossolinski J. E. Haramaty L. et al . (2009). Viral glycosphingolipids induce lytic infection and cell death in marine phytoplankton. Science326, 861–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1177322

147

Varma A. Palsson B. O. (1994). Stoichiometric flux balance models quantitatively predict growth and metabolic by-product secretion in wild-type Escherichia coli W3110. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.60, 3724–3731. doi: 10.1128/AEM.60.10.3724-3731.1994

148

Vijayakumar S. Rahman P. K. S. M. Angione C. (2020). A hybrid flux balance analysis and machine learning pipeline elucidates metabolic adaptation in cyanobacteria. iScience23. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101818

149

Volterra V. (1928). Variations and fluctuations of the number of individuals in animal species living together. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 3, 3–51. doi: 10.1093/ICESJMS/3.1.3

150

Waldbauer J. R. Coleman M. L. Rizzo A. I. Campbell K. L. Lotus J. Zhang L. (2019). Nitrogen sourcing during viral infection of marine cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.116, 15590–15595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901856116

151

Wang W. Ren J. Tang K. Dart E. Ignacio-Espinoza J. C. Fuhrman J. A. et al . (2020). A network-based integrated framework for predicting virus–prokaryote interactions. NAR. Genom. Bioinform.2. doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqaa044

152

Wangersky P. J. (1978). Lotka-volterra populaton models. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst.9, 189–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.09.110178.001201

153

Ward B. A. Dutkiewicz S. Moore C. M. Follows M. J. (2013). Iron, phosphorus, and nitrogen supply ratios define the biogeography of nitrogen fixation. Limnol. Oceanogr.58, 2059–2075. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.6.2059

154

Ward B. A. Follows M. J. (2016). Marine mixotrophy increases trophic transfer efficiency, mean organism size, and vertical carbon flux. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.113, 2958–2963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517118113

155

Warwick-Dugdale J. Buchholz H. H. Allen M. J. Temperton B. (2019). Host-hijacking and planktonic piracy: How phages command the microbial high seas. Virol. J.16. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1120-1

156

Weinbauer M. G. (2004). Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.28, 127–181. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001

157

Weitz J. S. Wilhelm S. W. (2012). Ocean viruses and their effects on microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles. F1000. Biol. Rep.4. doi: 10.3410/B4-17

158

Wilhelm S. W. Suttle C. A. (1999). Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea. Bioscience49, 781–788. doi: 10.2307/1313569

159

Wilson J. D. Andrews O. Katavouta A. De Melo Viríssimo F. Death R. M. Adloff M. et al . (2022). The biological carbon pump in CMIP6 models: 21st century trends and uncertainties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences119, e2204369119. doi: 10.1073/pnas

160

Winter C. Bouvier T. Weinbauer M. G. Thingstad T. F. (2010). Trade-offs between competition and defense specialists among unicellular planktonic organisms: the “Killing the winner” Hypothesis revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.74, 42–57. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00034-09

161

Wu Z. Dutkiewicz S. Jahn O. Sher D. White A. Follows M. J. (2021). Modeling photosynthesis and exudation in subtropical oceans. Global Biogeochem. Cycle.35, e2021GB006941. doi: 10.1029/2021GB006941

162

Xie L. Zhang R. Luo Y. W. (2022). Assessment of explicit representation of dynamic viral processes in regional marine ecological models. Viruses14. doi: 10.3390/v14071448

163

Zakharova L. Meyer K. M. Seifan M. (2019). Trait-based modelling in ecology: A review of two decades of research. Ecol. Mod.407. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2019.05.008

164

Zayed A. A. Wainaina J. M. Dominguez-Huerta G. Pelletier E. Guo J. Mohssen M. et al . (2022). Cryptic and abundant marine viruses at the evolutionary origins of Earth’s RNA virome. Science376, 156–162. doi: 10.1126/science.abm5847

165

Zhou T. (2021). New physical science behind climate change: What does IPCC AR6 tell us? Innovation2. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100173

166

Zimmerman A. E. Howard-Varona C. Needham D. M. John S. G. Worden A. Z. Sullivan M. B. et al . (2019). Metabolic and biogeochemical consequences of viral infection in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol18, 21–34. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0270-x

Glossary of terms

Modeling terms

Climate model. Also known as general circulation models (GCMs) explore interactions among energy and matter in different parts of the ocean, atmosphere, and land.

Earth system model. Climate models with explicit representation of biogeochemical processes that interact with the physical climate, impacting its response to forcing (Flato, 2011).

Process based model. Characterization of changes in the state of a system as explicit functions of events that drive those changes (Connolly et al., 2017).

Mechanism based model. Characterization of the state of a system explicitly with regard to interactions among component parts (Connolly et al., 2017).

Statistical model. Descriptive models of relationships between variables based on assumptions about data sampled (Zakharova et al., 2019). Also referred to as ‘descriptive’, ‘correlative’, ‘phenomenological’ and ‘purely descriptive’ models (Connolly et al., 2017).

Population model. Mechanism based models that relate individual level responses to changes in population density and structure (Maltby, 2001).

Trait based model. Characterization of effects of organismal traits on community and ecosystem properties

Parameter. Environmental scientists often use this term to refer to environmental properties, like light intensity or temperature. In the context of biological models, the term refers to numbers that are held constant and control model behavior. Growth rates, nutrient affinities, and burst sizes are examples of model parameters.

Variable. A property of a model that changes during a simulation. Community scale model variables are typically abundances or biomass densities. Some organismal and many molecular scale models resolve macromolecules as variables.

Trait. Any measurable property of an organism

Life-history trait. A trait that directly influences organismal growth or decline. In this context, life-history traits can also be thought of as model parameters.

Virus terms

Viral shunt. Movement of material from cells to dissolved and particulate forms that are subsequently consumed by bacteria, leading to the release of inorganic nutrients (Fuhrman, 1992, Fuhrman, 1999; Wilhelm and Suttle, 1999)

Viral shuttle. Carbon that is moved to the deep ocean via formation of particles that form due to viral lysis (Weinbauer, 2004; Sullivan et al., 2017).

Auxiliary metabolic gene (AMG). Virus genes that support the metabolic activity of hosts during infection.

Burst size. The number of viruses released by a cell upon viral lysis.

Virocell. A virus-infected cell infected; I.e. the “live” stage of a virus (Forterre, 2013).

Summary

Keywords

viruses, oceanography, biogeochemistry, microbial ecology, modeling

Citation

Talmy D, Howard-Varona C, Eveillard D, Covert M and Sullivan MB (2025) Viruses in multi-scale ocean models: challenges and opportunities. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1717845. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1717845

Received

02 October 2025

Revised

14 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

11 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Yongyu Zhang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Yida Gao, Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, United States

Wei Wei, Wuhan Institute of Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Talmy, Howard-Varona, Eveillard, Covert and Sullivan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Talmy, dtalmy@utk.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.