Abstract

For many decades, white band disease (WB) and white pox disease (WPX) have been severely impacting populations of the reef building corals Acropora palmata and A. cervicornis throughout the Caribbean region. Even after the major outbreaks in the 1990s and early 2000s, these diseases still occur annually in certain regions of the Caribbean, including in the United States Virgin Islands (USVI). Given the high virulence and infection rates of WB and WPX, mitigation treatments should be explored. It is highly suspected both diseases have bacterial pathogens, even though Henle-Koch’s postulates have not been fulfilled to determine the causative agent for WB nor WPX observed in the USVI. A specialized antibiotic paste utilizing amoxicillin trihydrate has successfully been used in situ to mitigate another disease impacting stony corals, stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD). Considering the past success of this topical paste, this study aimed to determine if this treatment could be used on A. palmata and A. cervicornis to treat WPX and WB, respectively. The topical antibiotic paste did not significantly halt disease lesion expansion, nor stop new lesions from forming. Therefore, other mitigation treatments for WB and WPX should be considered.

1 Introduction

Infectious coral disease outbreaks are becoming a primary threat to coral reef ecosystems, affecting their viability, structure, and functions (Bruckner, 2015; MacKnight et al., 2022). One of the most notable examples of disease altering coral community structure within the Caribbean is the white band disease (WB) epidemic affecting the Acropora genus (Bruckner, 2015). This disease was first described from St. Croix, United States Virgin Islands (USVI) in the 1970s (Gladfelter, 1982). WB is characterized by a band of necrotic tissue that exposes the bare skeleton encircling the base to mid-section of the branch progressing toward the tip at a rate of a few mm to several cm d-1 (Gladfelter, 1982). The extent of mortality caused by the WB epidemic was not quantified at the time, but it did cause notable declines in the A. palmata and A. cervicornis populations and structural changes to shallow reef habitats (Aronson and Precht, 2001; Carpenter et al., 2008). Currently, both species are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (NOAA, 2014). WB continues to threaten the low native Acropora populations within the USVI as the disease is now endemic (Smith et al., 2014; Ewen, 2022).

A couple decades after WB emerged, another acroporid disease called white pox disease (WPX) was described within the A. palmata population off Key West, Florida in 1996 (Holden, 1996). This disease was distinguished from WB based on gross appearance of focal to multifocal expanding lesions that appeared anywhere on the colony, exposing the underlying coral skeleton. In some cases, lesions expanded to cause total mortality of the colony (Patterson et al., 2002). WPX is highly host specific, only affecting A. palmata and is responsible for the loss of up to 85% of living acroporid cover within the Florida Keys (Holden, 1996; Patterson et al., 2002). Since the initial description, similar signs have been identified across the Caribbean including in the USVI (Polson et al., 2008; Lesser & Jarett, 2014).

The etiology for both diseases is still relatively unknown, but it is thought that they are caused by bacterial agents or an imbalance within the coral holobiont (Schul et al., 2023; Vollmer et al., 2023; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015; Patterson et al., 2002; Polson et al., 2008; Sutherland et al., 2016; Selwyn et al., 2025). While the causative agent for both diseases remains unknown, WB has been associated with three bacterial families: Vibrionales, Flavobacteriales, and Rickettsailes (Sweet et al., 2014; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015). WPX etiology is more complicated. WPX signs in Florida, was demonstrated to be caused by the bacterium Serratia marcescens, and was therefore named acroporid serratiosis (Sutherland et al., 2011; Polson et al., 2008). However, this bacterium is not associated with WPX in the U.S. Virgin Islands, suggesting an alternate pathogen for the signs of WPX observed here (Polson et al., 2008). This alternate pathogen is still largely thought to be bacterial due to the connection with acroporid serratiosis (Polson et al., 2008).

Another part of the basis for these etiological theories is the successful prevention ampicillin exhibited against WB transmission in an ex situ experiment, suggesting that a bacterial agent may be involved in its transmission and etiology (Kline and Vollmer, 2011; Selwyn et al., 2025). Additionally, antibacterial baths have been effective in halting WB lesion progression. Both ampicillin and paromomycin baths were observed to stop the growth of active WB on A. cervicornis (Sweet et al., 2014). Similarly, prophylactic use of ampicillin and tetracycline were found to reduce WB infection rates (Selwyn et al., 2025). While there is no literature of antibiotics tested against WPX, one study found microorganisms associated with A. palmata perform antibacterial activities against WPX associated bacteria (Wijayanti et al., 2020). The use of antibiotics, either inorganically or organically occurring, reinforces the working theory that WB and WPX are bacterially driven.

For in situ treatment of coral disease, the only developed regimen is an amoxicillin treatment named CoralCure Ointment Base2B (hereafter referred to as Base2B), developed to treat stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) by Ocean Alchemists LLC. SCTLD is a disease with unknown etiology, similar to WPX and WB. While they have not been identified to be the causative agent, eight bacterial families have been associated with SCTLD, the majority being gram-negative (Zhao et al., 2022; Alauzet et al., 2014; Milena et al., 2022; Waśkiewicz and Irzykowska, 2014; Pujalte et al., 2014; Løbner-Olesen et al., 2005; Mittal et al., 2023; Choma et al., 2017; Perez-Perez and Blaser, 1996). This proprietary paste is a silicone-based paste designed to be mixed with amoxicillin trihydrate and applied directly onto wild corals infected with SCTLD. The paste sticks to coral skeleton and not the coral tissue so it can be applied to lesion margins. Polymers within the paste mimic coral mucus consistency ensuring the amoxicillin is only released into the coral tissue at a fixed dosage rate over approximately three days (Ocean Alchemist LLC; Neely et al., 2021). Base2B mixed with amoxicillin is highly and unilaterally effective in halting SCTLD lesion progression across multiple different species (Neely et al., 2021). Furthermore, colonies that were regularly treated exhibited progressively improved health over time (Neely et al., 2021). The short -and long- term effectiveness of Base2B across multiple species against SCTLD, a disease of unknown etiology, suggests it could be effective in halting other coral disease lesions of unknown etiology, particularly given that WPX and WB are possibly bacterial driven. However, acroporids do not appear to be susceptible to SCTLD (Hawthorn et al., 2024) and Base2B has not been, to our knowledge, tested on diseases of acroporid species. Base2B has been tested on black band disease (BBD) but was found ineffective due to lack of adhesion given the nature of black band disease not leaving exposed skeleton for anchorage (Eaton et al., 2022).

Prior to the development of Ocean Alchemists ointments, in situ treatments were limited and mostly pertained to creating physical barriers between the diseased lesion and the healthy tissue on the coral (Dalton et al., 2010; Aeby et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2014). Some of the earliest records of intervention occurred in Florida when researchers used a vacuum pump to remove black band bacterial mats from colonies followed by the application of modeling clay over affected areas (Hudson, 2000). Amputation and trenching are physical methods that have been used in attempts to halt disease lesion progression, but these methods are damaging to corals, not always effective, and extremely labor intensive (Shilling et al., 2021; Aeby et al., 2015; Walton et al., 2018; Dalton et al., 2010). Additionally, other topical treatments consisted of smothering or applying chemicals. For example, modeling clay and putty were applied to infected areas (Bruckner and Bruckner, 1998), chlorinated epoxy was also tested (Aeby et al., 2015). However, these early topical treatments did not have high rates of halting lesion progression (Aeby et al., 2015; Lee Hing et al., 2022; Neely et al., 2020).

Currently, Base2B is the only antibiotic treatment that has been specifically developed to be applied to wild diseased corals. Given the treatment’s proven effectiveness and its design for in situ application against diseases of unknown etiology, there is an opportunity to test the treatment on diseased acroporids. The use of amoxicillin as the antibiotic against WB and WPX is supported by amoxicillin’s near identical properties to ampicillin which was effective against WB (Kline and Vollmer, 2011; Sweet et al., 2014). This study therefore aimed to test the effectiveness of the Base2B treatment on WPX and WB.

2 Materials and methods

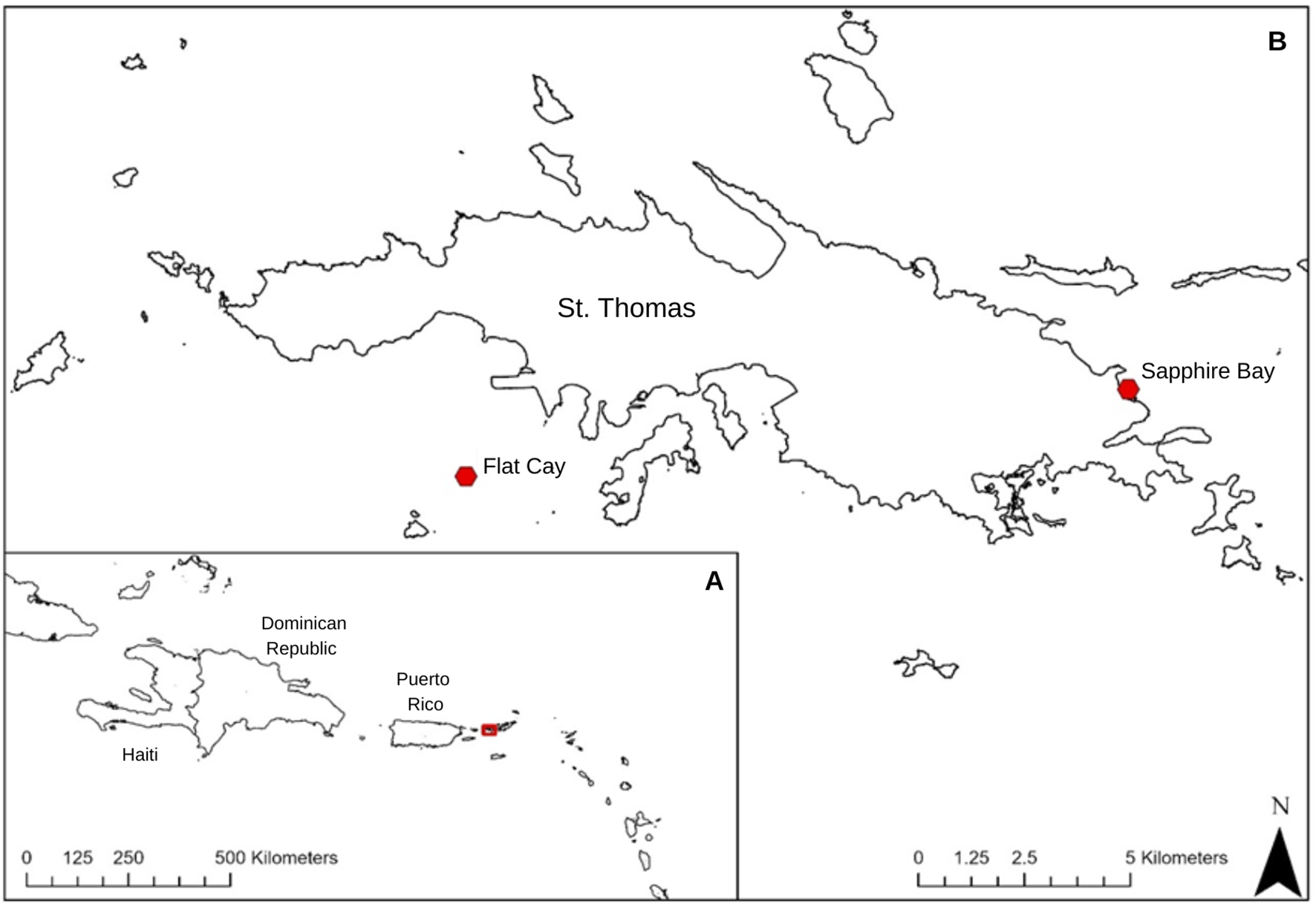

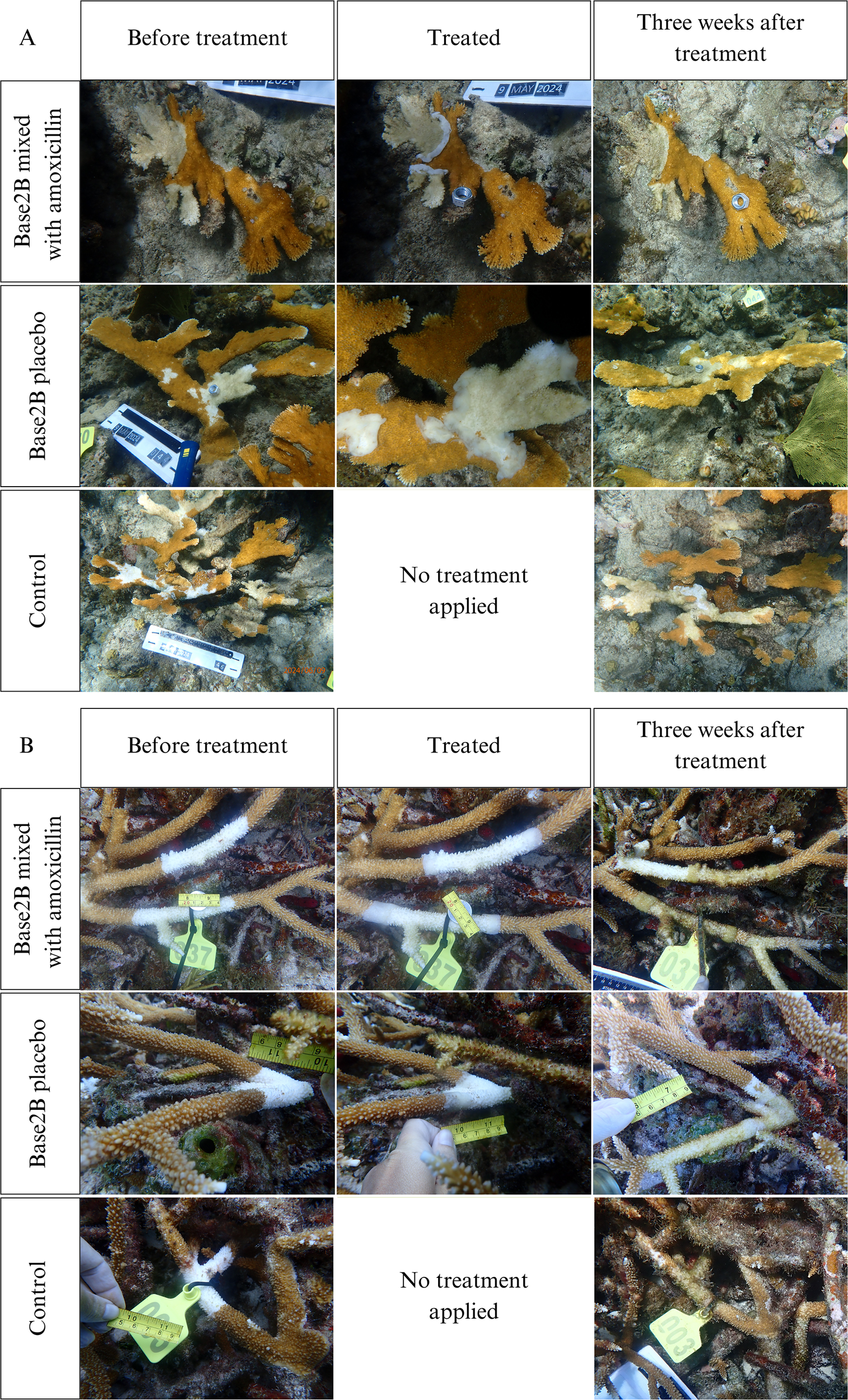

Three experiments were conducted around St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands in 2023 and 2024. A. palmata colonies (n = 19) affected with WPX were selected at Sapphire Bay (18.335063, -64.850235) in June 2024 and two sets of A. cervicornis colonies affected by WB were selected at Flat Cay (18.317148, -64.989223), the first in August 2023 (n = 18) and the second in July 2024 (n = 15) (Figure 1). The diseases were identified by the gross morphologies of the lesions which were consistent with previous descriptions in literature (Gladfelter, 1982; Patterson et al., 2002). WB was identified by progressing bands of exposed skeleton encircling the base to mid sections of A. cervicornis branches that created distinct lines with the living tissue. WPX was identified by multi-focal expanding lesions on the top of A. palmata branches bearing exposed skeleton larger than 5 cm in diameter and creating distinct lines with the living tissue (Figure 2). Each colony had between one to three active diseased lesions for their respective diseases. A total of 34 lesions were treated during the WPX experiment, 24 during the 2023 WB experiment, and 15 during the 2024 WB experiment (Table 1). All three experiments tested the same three treatment levels: 1) amoxicillin trihydrate mixed with Base2B at a ratio of 1:8 by weight, 2) Base2B with no amoxicillin trihydrate to act as a placebo, and 3) controls where no treatments were applied but the colonies and lesions were marked and followed through time. All treatments involving antibiotics were prepared less than six hours before application and kept on ice until use to ensure the amoxicillin did not undergo any degradation. Both the Base2B with amoxicillin and the Base2B placebo treatments were packed into labeled 60cc catheter syringes for application.

Figure 1

Study area map showing (A) the regional context of the study location and (B) the sites in St. Thomas the experiments took places denoted with red dots.

Figure 2

Examples of treatments applied to lesions: (A) white pox lesions, (B) white band lesions. Photos show the corals immediately before treatment was applied, immediately after treatment was applied, and two to three weeks after treatment was applied. (A) Lesions were measured in mm by their maximum length and the perpendicular width of the denuded skeleton area. (B) Lesion lengths were only measured in mm if they did not have a continuous connected branch like the one shown in the top row. If a continuous connected branch did exist like the one shown on the bottom row, then one branch was measured in mm for length and the connecting branch lesions was measured in mm as width.

Table 1

| Treatment | White band | White pox |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 12 | 13 |

| Base2B placebo | 14 | 8 |

| Control | 13 | 13 |

The number of lesions per treatment level within each disease.

Flat Cay was chosen for WB surveys due to its naturally large A. cervicornis population which roughly covers a 5,542 m2 area and Sapphire Bay for WPX surveys due to its large A. palmata population which roughly covers a 1,492 m2 area. During each survey, colonies with signs of the respective disease were chosen at random but each selected colony was ensured to be at least two meters away from any other selected colony. Different colonies were selected between the 2023 and 2024 WB experiments to ensure each trial was independent. Each colony was tagged, and a GPS location taken so that it could be relocated. Before treatment was applied, scaled ariel photos of the whole colony were taken in addition to scaled high magnification photos of all disease lesions. If there were multiple lesions on a colony, each lesion on the same colony was treated with the same treatment. Treatments were applied to colonies assigned paste-based treatments by hand along the lesion borders in a band approximately one cm wide, with a half cm of the treatment anchored onto the dead skeleton and a half cm of the treatment covering the live tissue (Figure 2). Once treated, scaled aerial and magnified photos were taken again. The corals during the 2024 WB experiment and the corals during the WPX experiment were revisited after two weeks. The corals in 2023 WB experiment were supposed to be revisited after two weeks, but weather conditions delayed revisitation by an additional week. During each revisitation, the same aerial and high magnification photos were taken of each colony and lesion. No more treatment was applied to the corals after the initial application, even if the lesions remained active.

The photos were analyzed in TagLab (v.2023.5.17) (Pavoni et al., 2022) to track any changes in lesion size after treatment. Given the WB lesions on A. cervicornis wrapped completely around the affected branch and primarily progressed linearly along the branch, the lesion lengths were measured in mm. If the lesion progressed continuously to a connected branch in a perpendicular fashion, then the secondary branch was measured in mm and considered the width, as seen in the bottom row of photos in Figure 2B. WPX lesions were predominantly irregular patches surrounded by live tissue; the maximum length and the perpendicular width of the denuded skeleton area were measured to determine size. Once measured, the change in lesion length was ascertained by subtracting the final lesion length from the initial lesion length plus the final lesion width subtracted by the initial lesion width divided by two.

This method of quantifying tissue loss was used because the average of multiple linear measurements is proven to provide an accurate and precise assessment of tissue loss, while still ensuring comparability between different time points (Neely, 2024). All lesions treated with a paste were reduced by five mm to account for the live tissue that was covered by the treatment. Rates of lesion expansion were also calculated by dividing the change in lesion size by the number of days between surveys.

All lesions were considered independent of one another for statistical analysis even if they occurred on the same colony. This decision was based on evidence that suggests WB and WPX lesion development is an independent phenomenon based on differences in microbiomes between diseased and healthy regions on the same colony (Schul et al., 2023). However, the colonies were incorporated as a random effect to account for possible effects the colonies may have had on recovery rates. Data from the two WB experiments were combined for analysis because the average rate of lesion expansion was not significantly different between the two time points. The combined WB and WPX experiments were analyzed independently of each other given the difference in species and disease observed. A chi-squared test was used to test for differences in the proportion of halted versus unhalted lesions among treatment levels. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) (α = 0.05) was then used to determine the effectiveness of each treatment level at halting WB and WPX lesion progression in RStudio (v.4.4.1). To ascertain the effectiveness of treatment at the colonial level, the mode for all lesions on a single colony was determined and used in an additional chi-squared test.

3 Results

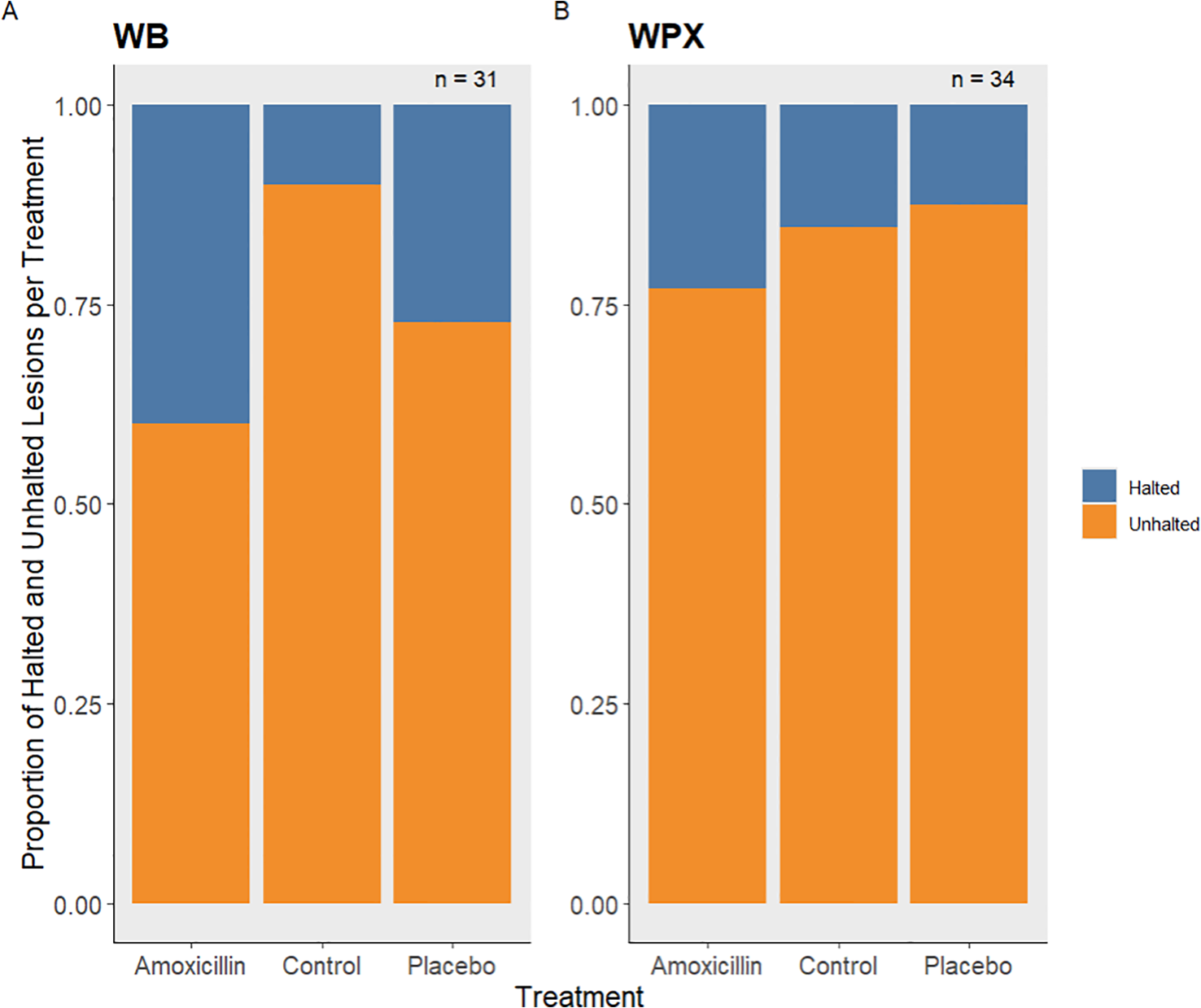

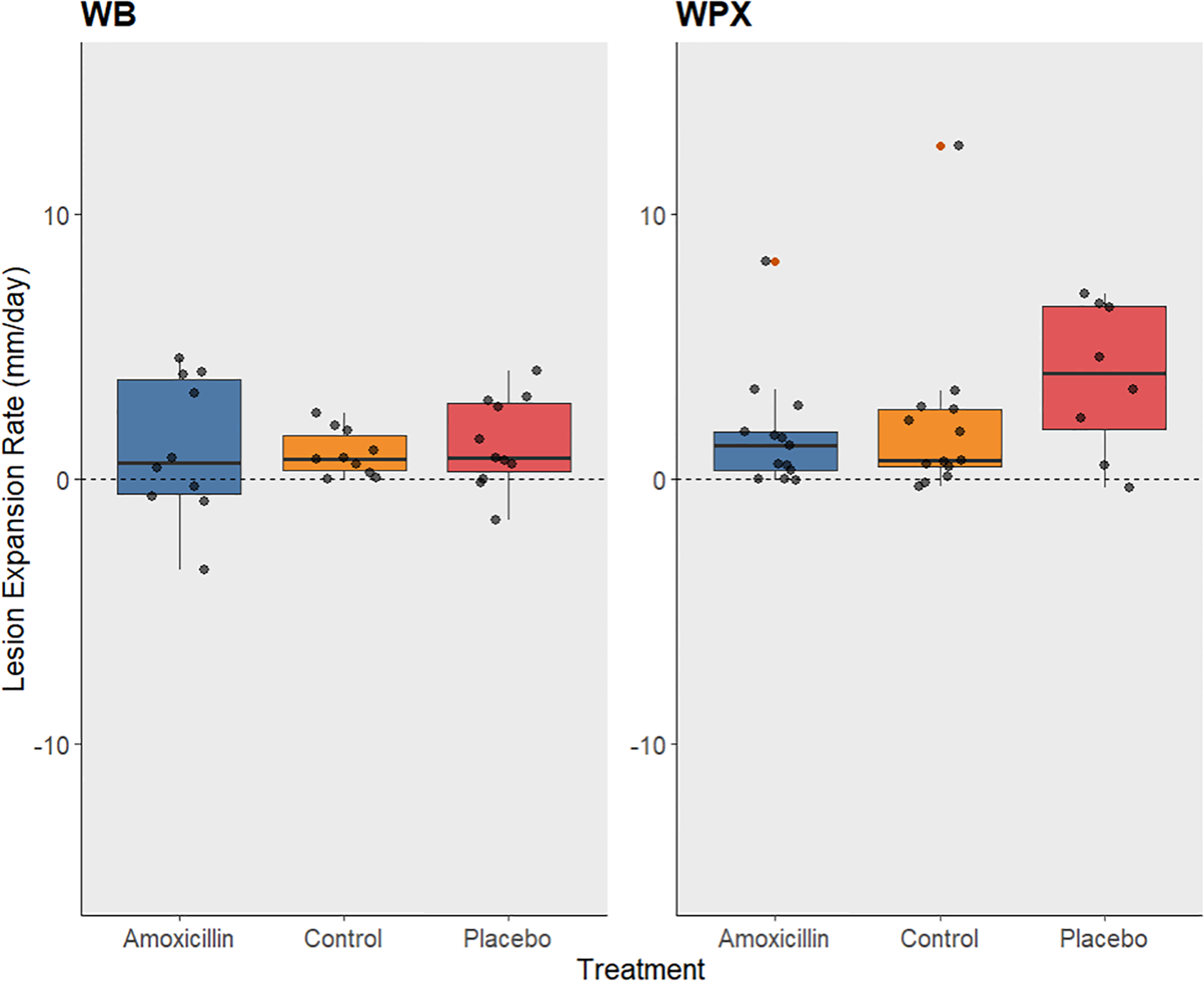

The majority of diseased lesions across both experiments remained active after treatments were administered. No significant effect was found among treatments on the proportion of lesions halted for either experiment (Chi-squared p-values > 0.05) (Table 2). Though treatment successes were not statistically different, 40% of all WB lesions (10 lesions) treated with the mix of Base2B and amoxicillin were successfully halted, while only 27% of the lesions (11 lesions) treated with the Base2B placebo were halted. Within the control group, only one lesion (10%) halted on its own accord (Figure 3A). During the WPX experiment, 15% of the lesions (13 lesions) treated with the antibiotic paste were successfully halted. While 13% of the lesions (8 lesions) treated with the placebo paste were halted; and only two lesions (15%) within the control group halted on their own accord (Figure 3B). Similarly, the lesion expansion rates did not differ among treatments for either the WB nor the WPX experiment (Figure 4; Table 1).

Table 2

| Disease treated | ANOVA F-value | ANOVA p-value | X-squared value | Chi-squared p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White band | 0.090 | 0.914 | 53.029 | 0.5119 |

| White pox | 1.479 | 0.244 | 68.000 | 0.4089 |

The p-value for each treatment experiment analysis. The ANOVAs were conducted on the rate of change in lesion length between treatment levels.

The Chi-squared analyses were conducted on the proportion of halted and unhalted lesions between treatment levels. The grey indicates the results from the proportional data.

Figure 3

The proportion of halted and unhalted lesions per treatment level (A) for both white band experiments combined and (B) the 2024 white pox experiment.

Figure 4

Box plot showing the rate of lesion expansion (mm/day) for each treatment level. Amoxicillin treatments are represented with blue, controls with orange, and placebo treatments with red. The dotted line represents no change in lesion length, above the line represents lesion growth, and below the line represents lesion regression. (A) rate of change in white band lesions from both 2023 and 2024 monitoring period, (B) rate of change in white pox lesions during the monitoring period in 2024. Orange dots represent outliers.

When analyzed at the colony level, treatment still did not significantly affect WPX (X-squared = 36, p-value = 0.3751) nor WB (X-squared = 34, p-value = 0.3715). Three colonies affected by WPX experienced full lesion cessation, two were treated with amoxicillin and one was treated with the placebo. However, these colonies only had one lesion each. Five colonies affected by WB experienced full lesion cessation, two colonies were treated with amoxicillin, two colonies were treated with the placebo, and one was a control. The colonies treated with the placebo and the control colony only had one lesion each. The colonies treated with the amoxicillin both had two lesions.

4 Discussion

Historically, the use of antibiotics on corals has primarily been used to determine if the causative agents for diseases were bacterial or to treat diseased corals in a laboratory setting, not to treat infected corals in situ (Kline and Vollmer, 2011). It was not until the emergence of SCTLD and the creation of Base2B that a topical antibiotic was used to treat corals in the wild. Even though the effectiveness of this new treatment was not always 100% and varied between species, it was successful in halting the disease progression overall (Neely et al., 2020). The difference in effectiveness of the antibiotic paste against SCTLD versus WPX and WB was contradictory to what was expected. Though more lesions were halted in the antibiotic treatment, particularly for WB, it was not statistically significant for either of the acroporid diseases tested in comparison to the placebo and the unmanipulated controls. With a higher number of samples, a significant result may have been found for WB, but for WPX there was little difference among treatments. Therefore, we would recommend more testing for WB and not recommend Base2B and amoxicillin as a treatment for WPX.

Amoxicillin was chosen as the antibiotic in this study for several reasons. It was the most successful antibiotic against SCTLD which is a rapid tissue loss disease similar to WB and WPX (Miller et al., 2020). Amoxicillin was the most effective antibiotic against SCTLD in an ex situ experiment, resulting in a 97% survival rate of infected coral fragments (Miller et al., 2020). In situ, the amoxicillin and Base2B mix proved to be 88-95% effective at halting SCTLD across seven species (Neely et al., 2021; Shilling et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2021). The effectiveness of the antibiotics against SCTLD suggests the involvement of bacteria in the disease’s progression (Papke et al., 2024). The bacterial orders Flavobacteriales, Clostridiales, Rhodobacterales, Alteromonadales, Vibrionales, Rhizobiales, Campylobacterales, and Peptostreptococcales-Tissierellaels were found to be enriched in SCTLD lesions compared to apparently healthy tissue, which could lend insight to the effectiveness of antibiotics in halting lesion progression (Rosales et al., 2023, 2022; Clark et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2021; Papke et al., 2024). Of these enriched bacterial orders found in SCTLD lesions, two of these orders are also associated with WB; Flavobacteriales and Vibrionales (Schul et al., 2023; Sweet et al., 2014; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015). The parallels between these disease-associated bacteria lent support for amoxicillin being effective against WB in addition to amoxicillin being nearly identical to ampicillin which was found to be highly effective against WB (Kline and Vollmer, 2011; Sweet et al., 2014; Selwyn et al., 2025). WPX is also closely associated with Enterobacter spp. and Vibrio spp., with Serratia marcescens causing a form of WPX and Vibrio spp. found to have a higher concentration in diseased tissue compared to apparently healthy tissue. Regardless of the factors supporting the use of amoxicillin against WPX and WB, this study revealed no statistical effect of it halting lesion progression for WPX and WB.

The ineffectiveness of amoxicillin could be a result of the way amoxicillin functions. Amoxicillin inhibits the biosynthesis and repair of the bacterial mucopeptide wall for a wide range of gram-positive and few gram-negative bacteria (Akhavan et al., 2021; Karaman, 2015). Therefore, amoxicillin is primarily used against gram-positive bacteria (Karaman, 2015). Of the three bacterial families associated with WB – Vibrionales, Flavobacteriales, and Rickettsiales (Sweet et al., 2014; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015) – amoxicillin is only effective against species found in the Flavobacteriales and Rickettsiales orders (Yudiati and Azhar, 2021; Barnes and Brown, 2011; Rolain et al., 1998). While S. marcescens was not found associated with WPX in the U.S. Virgin Islands, it is the implicated pathogen in acroporid serratiosis which presents similarly to other forms of WPX, like the one observed in this region (Sutherland et al., 2011; Polson et al., 2008). This bacterium is a gram-negative bacterium that is not sensitive to amoxicillin (Khanna et al., 2012; Fusté et al., 2012; Bodey and Nance, 1972). If the pathogen for the U.S. Virgin Islands form of WPX is similar to S. marcescens, then the bacterium may not be susceptible to the mechanics of amoxicillin trihydrate. If both diseases are in fact caused by gram-negative bacteria, it could be the main reason the topical antibiotic failed in both experiments. However, this does not explain why ampicillin baths were highly successful in the ex situ experiments with WB and WPX, since ampicillin functions similarly to amoxicillin and is most effective against gram-positive bacteria (Sweet et al., 2014; Kline and Vollmer, 2011). Nor does it explain how the topical antibiotic paste was successful against SCTLD considering only two of the eight bacterial orders associated with SCTLD are gram-positive (Zhao et al., 2022; Alauzet et al., 2014; Waśkiewicz and Irzykowska, 2014; Løbner-Olesen et al., 2005; Mittal et al., 2023; Choma et al., 2017; Perez-Perez and Blaser, 1996). The varying results of amoxicillin in halting disease progression for all three diseases could instead be an indication that the cause of the WPX and WB is more complex than a single causative bacterium.

Past research emphasizes finding a singular causative agent of bacterial origins for WPX and WB, however, the contrasting ineffectiveness of amoxicillin in this study suggests these diseases do not follow a one pathogen-one disease paradigm. WPX and WB are possibly a result of environmental factors changing normally benign and non-pathogenic bacteria into harmful secondary infectors that can originate from either the environment or the coral’s microbiome (Lesser et al., 2007; Garzon-MaChado et al., 2024; Casas et al., 2004). One study found that Vibrio spp. were common residents in healthy A. palmata mucus and speculated the occurrence of WPX or WB may be due to a change in the composition of the bacteria and not the colonization and infection of the pathogen from the environment (Garzon-MaChado et al., 2024; Selwyn et al., 2025). Similarly, Rickettsiales spp. were found to be common in healthy A. cervicornis fragments as well as diseased ones and it is believed they play a role in secondary colonization when thermal stress occurs (Gignoux-Wolfsohn et al., 2020). This follows the dysbiosis theory for coral diseases (Vega Thurber et al., 2020). Dysbiosis is when environmental stressors shift the microbial composition of the coral holobiont to be favorable for disease (Vega Thurber et al., 2020). If the diseases are a result of dysbiosis, the application of a singular antibiotic, such as amoxicillin, would be ineffective because it only targets specific bacteria that are not the causative agent, or at least not the singular causative agent. Instead, treatments would have to be more holistic, treating the entire disrupted microbiome. Such treatments could include the application of probiotics, which have shown promise in treating SCTLD in Florida. A chemically characterized coral probiotic treatment applied prophylactically to affected corals in a lab setting slowed or halted the progression of SCTLD on most of the fragments and completely prevented disease transmission (Ushijima et al., 2023). However, more research is needed to understand host-microbiome interactions in the context of disease and treatments (Ushijima et al., 2023). Another study, which tested the effectiveness of amoxicillin on yellow band disease (YBD) in the Caribbean, found similar results to our findings (Pearson-Lund et al., 2025). Amoxicillin proved ineffective in halting lesion progression for YBD, which is also thought to be a dysbiotic disease, and holistic treatments were recommended instead (Pearson-Lund et al., 2025). The ineffectiveness of a singular antibiotic against a disease caused by dysbiosis and WB falling into this pattern is further supported by the success in preventing WB transmission using prophylactic antibiotic baths containing four different antibiotics (Selwyn et al., 2025). The preemptive baths worked against dysbiosis because they altered the coral microbiome and removed bacterial strains in the microbiome that are potential secondary infectors, thus treating the microbiome as a whole (Selwyn et al., 2025). The effectiveness of multi-antibiotic mixtures at halting lesion progression ex situ lends favor to investigating the effectiveness of antibiotic mixtures in situ on WB and WPX. However, the application of broad-spectrum antibiotics in situ should be used prudently given the limited understanding of diseased microbiomes and the associated risks such as increasing the potential for antibiotic resistance (Larsson and Flach, 2022).

SCTLD is known to impact 22 scleractinian species, none of which include Acropora species. Most of the SCTLD susceptible species embody bouldering morphology, arguably the most noticeable difference between the SCTLD susceptible species and branching Acropora (Hawthorn et al., 2024). When looking deeper, the differences continue on a molecular level with differences in their algal symbiont community. Ex situ, both A. palmata and A. cervicornis host Symbiodinium, specifically S. fitti (Palacio-Castro et al., 2021; Elder et al., 2023). However, most SCTLD susceptible species are primarily found with Breviolum or have very flexible algal symbiont assemblages and usually associate with multiple genera at once (Papke et al., 2024). In fact, Symbiodinium is almost exclusively associated with low to no SCTLD susceptibility species (Papke et al., 2024). The implication that the algal symbionts are responsible for susceptibility to SCLTD is further supported by the evidence SCTLD is caused by a virus infecting and degrading the Symbiodiniaceae (Beavers et al., 2023). While there is no current evidence suggesting WB or WPX is caused by infected symbionts, the molecular and morphological differences between Acropora species and SCTLD susceptible species could also contribute to the difference in validity of the Base2B treatment between the white diseases.

Regardless of the reason behind the ineffectiveness of the Base2B treatment, the failure to significantly halt WB and WPX lesions suggests this treatment should not be considered as an intervention method. Until the causative agent is identified for individual diseases or the paradigms influencing coral epizootics is sufficiently understood, the proper course for mitigation will remain unknown. While treatments are not expected to completely mitigate disease from the reef environment based on past literature, they can be critical tools in saving corals during major outbreaks (Neely et al., 2021). Continuing to broaden possible treatments for coral diseases should be continued.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

AC: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. SM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. TS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MB: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation award (#2109622) to MB as well as VI EPSCoR (NSF #1946412).

Acknowledgments

This work could not have been completed without the hours of fieldwork dedicated by Moriah Seveier, Natasha Bestrom, Alexandra Cormack, C.J. Johnson, Stefanie Maxin, and Kianna Pattengale. Field work was authorized by the Department of Planning and Natural Resources Coastal Zone Management permit #(DFW23039T). This is contribution (305) from the Center of Marine and Environmental Studies at the University of the Virgin Islands.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aeby G. S. Work T. M. Runyon C. M. Shore-Maggio A. Ushijima B. Videau P. et al . (2015). First record of black band disease in the Hawaiian archipelago: response, outbreak status, virulence, and a method of treatment. PloS One10, e0120853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120853

2

Akhavan B. J. Khanna N. R. Vijhani P. (2021). “ Amoxicillin,” in StatPearls ( StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL).

3

Alauzet C. Marchandin H. Courtin P. Mory F. Lemée L. Pons J. L. et al . (2014). Multilocus analysis reveals diversity in the genus Tissierella: description of Tissierella carlieri sp. nov. in the new class Tissierellia classis nov. Systematic Appl. Microbiol.37, 23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.09.007

4

Aronson R. B. Precht W. F. (2001). “ White-band disease and the changing face of Caribbean coral reefs,” in The ecology and etiology of newly emerging marine diseases ( Springer, Dordrecht), 25–38.

5

Barnes M. E. Brown M. L. (2011). A review of Flavobacterium psychrophilum biology, clinical signs, and bacterial cold water disease prevention and treatment. Open Fish Sci. J.4, 40. doi: 10.2174/1874401X01104010040

6

Beavers K. M. Van Buren E. W. Rossin A. M. Emery M. A. Veglia A. J. Karrick C. E. et al . (2023). Stony coral tissue loss disease induces transcriptional signatures of in situ degradation of dysfunctional Symbiodiniaceae. Nat. Commun.14, 2915. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38612-4

7

Becker C. C. Brandt M. Miller C. A. Apprill A. (2021). Microbial bioindicators of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease identified in corals and overlying waters using a rapid field-based sequencing approach. Environ. Microbiol.24, 1166–1182. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15718

8

Bodey G. P. Nance J. (1972). Amoxicillin: in vitro and pharmacological studies. Antimicrobial Agents chemotherapy1, 358–362. doi: 10.1128/AAC.1.4.358

9

Bruckner A. W. (2015). History of coral disease research. Dis. coral, 52–84.

10

Bruckner A. W. Bruckner R. (1998). Destruction of coral by Sparisoma viride. Coral Reefs17, 350. doi: 10.1007/s003380050138

11

Carpenter K. E. Abrar M. Aeby G. Aronson R. B. Banks S. Bruckner A. et al . (2008). One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science321, 560–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1159196

12

Casas V. Kline D. I. Wegley L. Yu Y. Breitbart M. Rohwer F. (2004). Widespread association of a Rickettsiales-like bacterium with reef-building corals. Environ. Microbiol.6, 1137–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00647.x

13

Choma A. Komaniecka I. Zebracki K. (2017). Structure, biosynthesis and function of unusual lipids A from nodule-inducing and N2-fixing bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Biol. Lipids1862, 196–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.11.004

14

Clark A. S. Williams S. D. Maxwell K. Rosales S. M. Huebner L. K. Landsberg J. H. et al . (2021). Characterization of the microbiome of corals with stony coral tissue loss disease along Florida’s coral reef. Microorganisms9, 2181. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9112181

15

Dalton S. J. Godwin S. Smith S. D. A. Pereg L. (2010). Australian subtropical white syndrome: a transmissible, temperature-dependent coral disease. Mar. Freshw. Res.61, 342–350. doi: 10.1071/MF09060

16

Eaton K. R. Clark A. S. Curtis K. Favero M. Hanna Holloway N. Ewen K. et al . (2022). A highly effective therapeutic ointment for treating corals with black band disease. PloS One17, e0276902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276902

17

Elder H. Million W. C. Bartels E. Krediet C. J. Muller E. M. Kenkel C. D. (2023). Long- term maintenance of a heterologous symbiont association in Acropora palmata on natural reefs. ISME J.17, 486–489. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01349-x

18

Ewen K. A. (2022). Buck Island’s Corals Get Relief from a Deadly Disease ( National Park Service). Available online at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/buck-islands-corals-get-relief-from-a-deadlydisease.htm (Accessed January 28, 2025).

19

Fusté E. Galisteo G. J. Jover L. Vinuesa T. Villa T. G. Viñas M. (2012). Comparison of antibiotic susceptibility of old and current Serratia. Future Microbiol.7, 781–786. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.40

20

Garzon-MaChado M. Luna-Fontalvo J. García-Urueña R. (2024). Disease prevalence and bacterial isolates associated with Acropora palmata in the Colombian Caribbean. PeerJ12, e16886. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16886

21

Gignoux-Wolfsohn S. A. Precht W. F. Peters E. C. Gintert B. E. Kaufman L. S. (2020). Ecology, histopathology, and microbial ecology of a white-band disease outbreak in the threatened staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis. Dis. Aquat. Organisms137, 217–237. doi: 10.3354/dao03441

22

Gignoux-Wolfsohn S. A. Vollmer S. V. (2015). Identification of candidate coral pathogens on white band disease-infected staghorn coral. PloS One10, e0134416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134416

23

Gladfelter W. B. (1982). White-band disease in Acropora palmata: implications for the structure and growth of shallow reefs. Bull. Mar. Sci.32, 639–643.

24

Hawthorn A. C. Dennis M. Kiryu Y. Landsberg J. Peters E. Work T. (2024). Stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) case definition for wildlife: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques Methods19, 20. doi: 10.3133/tm19I1

25

Holden C. (1996). Coral disease hot spot in Florida Keys. Science274, 2017.

26

Hudson H. (2000). First aid for massive corals infected with black band disease: an underwater aspirator and post-treatment sealant to curtail re-infection. Diving Sci. 21st Century, 10–11.

27

Karaman R. (2015). From conventional prodrugs to prodrugs designed by molecular orbital methods. Front. Comput. Chem.2, 187–249. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-60805-979-9.50005-6

28

Khanna N. Boyes J. Lansdell P. M. Hamouda A. Amyes S. G. (2012). Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance pattern of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Glasgow, Scotland. J. antimicrobial chemotherapy67, 573 577. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr523

29

Kline D. Vollmer S. (2011). White band disease (type I) of endangered caribbean acroporid corals is caused by pathogenic bacteria. Sci. Rep.1. doi: 10.1038/srep00007

30

Larsson D. G. J. Flach C.-F. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.20, 257–269. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00649-x

31

Lee Hing C. Guifarro Z. Dueñas D. Ochoa G. Nunez A. Forman K. et al . (2022). Management responses in Belize and Honduras, as stony coral tissue loss disease expands its prevalence in the Mesoamerican reef. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.883062

32

Lesser M. P. Bythell J. C. Gates R. D. Johnstone R. W. Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2007). Are infectious diseases really killing corals? Alternative interpretations of the experimental and ecological data. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.346, 36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.02.015

33

Lesser M. P. Jarett J. K. (2014). Culture-dependent and culture-independent analyses reveal no prokaryotic community shifts or recovery of Serratia marcescens in Acropora palmata with white pox disease. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.88, 457–467. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12311

34

Løbner-Olesen A. Skovgaard O. Marinus M. G. (2005). Dam methylation: coordinating cellular processes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol.8, 154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.009

35

MacKnight N. J. Dimos B. A. Beavers K. M. Muller E. M. Brandt M. E. Mydlarz L. D. (2022). Disease resistance in coral is mediated by distinct adaptive and plastic gene expression profiles. Sci. Adv.8, eabo6153. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo6153

36

Milena B. Stefano M. Tiziana S. (2022). Clostridium spp. Encyclopedia Dairy Sci.3), 431–438. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22989-2

37

Miller M. W. Lohr K. E. Cameron C. M. Williams D. E. Peters E. C. (2014). Disease dynamics and potential mitigation among restored and wild staghorn coral, Acropora cervicornis. PeerJ2, e541. doi: 10.7717/peerj.541

38

Miller C. V. May L. A. Moffitt Z. J. Woodley C. M. (2020). Exploratory treatments for stony coral tissue loss disease: pillar coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus). doi: 10.25923/d632-jc82

39

Mittal M. Tripathi S. Saini A. Mani I. (2023). Phage for treatment of Vibrio cholera infection. Prog. Mol. Biol. Trans. Sci.201, 21–39. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2023.03.021

40

Neely K. L. (2024). Measuring coral disease lesions: a comparison of methodologies. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1348929

41

Neely K. L. Macaulay K. A. Hower E. K. Dobler M. A. (2020). Effectiveness of topical antibiotics in treating corals affected by Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease. PeerJ8, e9289. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9289

42

Neely K. L. Shea C. P. Macaulay K. A. Hower E. K. Dobler M. A. (2021). Short-and long- term effectiveness of coral disease treatments. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.675349

43

NOAA (2014). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Final Listing Determinations on Proposal to List 66 Reef-building Coral Species and to Reclassify Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals ( Administration NOAA), 1104.

44

Palacio-Castro A. M. Dennison C. E. Rosales S. M. Baker A. C. (2021). Variation in susceptibility among three Caribbean coral species and their algal symbionts indicates the threatened staghorn coral, Acropora cervicornis, is particularly susceptible to elevated nutrients and heat stress. Coral Reefs40, 1601–1613. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02159-x

45

Papke E. Carreiro A. Dennison C. Deutsch J. M. Isma L. M. Meiling S. S. et al . (2024). Stony coral tissue loss disease: a review of emergence, impacts, etiology, diagnostics, and intervention. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1321271

46

Patterson K. L. Porter J. W. Ritchie K. B. Polson S. W. Mueller E. Peters E. C. et al . (2002). The etiology of white pox, a lethal disease of the Caribbean elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.99, 8725–8730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092260099

47

Pavoni G. Corsini M. Ponchio F. Muntoni A. Edwards C. Pedersen N. et al . (2022). Taglab: AI-assisted annotation for the fast and accurate semantic segmentation of coral reef orthoimages. J. Field Robotics39, 246–262. doi: 10.1002/rob.22049

48

Pearson-Lund A. S. Williams S. D. Eaton K. R. Clark A. S. Holloway N. H. Ewen K. A. et al . (2025). Evaluating the effect of amoxicillin treatment on the microbiome of Orbicella faveolata with Caribbean yellow band disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., e02407–e02424. doi: 10.1128/aem.02407-24

49

Perez-Perez G. Blaser M. J. (1996). Campylobacter and helicobacter. 4th edition (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Medical Microbiology).

50

Polson S. W. Higgins J. L. Woodley C. M. (2008). PCR-based assay for detection of four coral pathogens. Proc 11th Proc 9th Int Coral Reef Symp Ft Lauderdale. 8, 247–251.

51

Pujalte M. J. Lucena T. Ruvira M. A. Arahal D. R. Macián M. C. (2014). “ The Family Rhodobacteraceae,” in The Prokaryotes. Eds. RosenbergE.DeLongE. F.LoryS.StackebrandtE.ThompsonF. ( Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg). doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-30197-1_377

52

Rolain J. M. Maurin M. Vestris G. Raoult D. (1998). In vitro susceptibilities of 27 rickettsiae to 13 antimicrobials. Antimicrobial Agents chemotherapy42, 1537–1541. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1537

53

Rosales S. M. Huebner L. K. Clark A. S. McMinds R. Ruzicka R. R. Muller E. M. (2022). Bacterial metabolic potential and micro-eukaryotes enriched in stony coral tissue loss disease lesions. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.776859

54

Rosales S. M. Huebner L. K. Evans J. S. Apprill A. Baker A. C. Becker C. C. et al . (2023). A meta-analysis of the stony coral tissue loss disease microbiome finds key bacteria in unaffected and lesion tissue in diseased colonies. ISME Commun.3, 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s43705-023-00220-0

55

Schul M. D. Anastasious D. Spiers L. J. Meyer J. L. Frazer T. K. Brown A. L. (2023). Concordance of microbial and visual health indicators of white-band disease in nursery reared Caribbean coral Acropora cervicornis. PeerJ11, e15170. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15170

56

Selwyn J. D. Despard B. A. Galvan-Dubois K. A. Trytten E. C. Vollmer S. V. (2025). Antibiotic pretreatment inhibits white band disease infection by suppressing the bacterial pathobiome. Front. Mar. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1491476

57

Shilling E. N. Combs I. R. Voss J. D. (2021). Assessing the effectiveness of two intervention methods for stony coral tissue loss disease on Montastraea cavernosa. Sci. Rep.11, 8566. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86926-4

58

Smith T. B. Brandt M. E. Brewer R. S. Kisabeth J. Ruffo A. Sabine A. M. et al . (2014). Acroporid monitoring & Mapping program of the United States virgin islands.

59

Sutherland K. P. Berry B. Park A. Kemp D. W. Kemp K. M. Lipp E. K. et al . (2016). Shifting white pox aetiologies affecting Acropora palmata in the Florida Keys 1994 2014. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.371, 20150205. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0205

60

Sutherland K. P. Shaban S. Joyner J. L. Porter J. W. Lipp E. K. (2011). Human pathogen shown to cause disease in the threatened eklhorn coral Acropora palmata. PloS One.6, e23468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023468

61

Sweet M. J. Croquer A. Bythell J. C. (2014). Experimental antibiotic treatment identifies potential pathogens of white band disease in the endangered Caribbean coral Acropora cervicornis. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.281, 20140094. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0094

62

Ushijima B. Gunasekera S. P. Meyer J. L. Tittl J. Pitts K. A. Thompson S. et al . (2023). Chemical and genomic characterization of a potential probiotic treatment for stony coral tissue loss disease. Commun. Biol.6, 248. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04590-y

63

Vega Thurber R. Mydlarz L. D. Brandt M. Harvell D. Weil E. Raymundo L. et al . (2020). Deciphering coral disease dynamics: integrating host, microbiome, and the changing environment. Front. Ecol. Evol.8. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.575927

64

Vollmer S. V. Selwyn J. D. Despard B. A. Roesel C. L. (2023). Genomic signatures of 33 disease resistance in endangered staghorn corals. Science381, 1451–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.adi3601

65

Waśkiewicz A. Irzykowska L. (2014). Flavobacterium spp.–characteristics, occurrence, and toxicity. Encyclopedia Food Microbiol., 938–942. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-3847300.00126-9

66

Walker B. K. Turner N. R. Noren H. K. Buckley S. F. Pitts K. A. (2021). Optimizing stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) intervention treatments on Montastraea cavernosa in an endemic zone. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.666224

67

Walton C. J. Hayes N. K. Gilliam D. S. (2018). Impacts of a regional, multi-year, multi-species coral disease outbreak in Southeast Florida. Front. Mar. Sci.5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00323

68

Wijayanti D. P. Sabdono A. Dirgantara D. Widyananto P. A. Sibero M. T. Bhagooli R. et al . (2020). Antibacterial activity of acroporid bacterial symbionts against White Patch Disease in Karimunjawa Archipelago, Indonesia. Egyptian J. Aquat. Res.46, 187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ejar.2020.02.002

69

Yudiati E. Azhar N. (2021). “ Antimicrobial susceptibility and minimum inhibition concentration of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio harveyi isolated from a white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) pond,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science ( IOP Publishing), Vol. 763. 012025. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/763/1/012025

70

Zhao L. Zhang J. Xu Z. Cai S. Chen L. Cai T. et al . (2022). Bioconversion of waste activated sludge hydrolysate into polyhydroxyalkanoates using Paracoccus sp. TOH: Volatile fatty acids generation and fermentation strategy. Bioresource Technol.363, 127939. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127939

Summary

Keywords

Acropora , amoxicillin, Caribbean, disease, white band, white pox

Citation

Coble A, Meiling S, Smith TB and Brandt M (2026) Ineffectiveness of topical antibiotics in treating Acropora spp. affected by white diseases. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1720360. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1720360

Received

07 October 2025

Revised

23 December 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

26 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Thierry Work, United States Department of the Interior, United States

Reviewed by

Katherine Eaton, University of Miami, United States

Tess Moriarty, The University of Newcastle, Australia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Coble, Meiling, Smith and Brandt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marilyn Brandt, mbrandt@uvi.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.