1 Introduction

Dark oxygen production (DOP) broadly encompasses all light-independent pathways that produce oxygen (Ruff et al., 2024), including microbial and abiotic processes such as radiolysis of water (Gutsalo, 1970; Sauvage et al., 2021), chlorite dismutation (Xu and Logan, 2003), nitric oxide dismutation (Ettwig et al., 2012) and, water lysis via methanobactins (Dershwitz et al., 2021). Recently, Sweetman et al. (2024) claim to present evidence for a novel form of DOP occurring at the abyssal seafloor, which they attribute to seawater electrolysis driven by polymetallic nodules. Although transient, the reported rates (1.7–18 mmol O2 m-2 d-1) are substantial—equivalent to 0.5–180% of gross community production measured in the Equatorial Pacific (10–365 mmol O2 m-2 d-1; Stanley et al. (2010)), a region recognized among the most photosynthetically productive in the open-oceans (Rousseaux and Gregg, 2013). If real, nodule-associated DOP would constitute the discovery of an entirely new source of oxygen, and could challenge the long-standing paradigm that the abyssal seafloor functions exclusively as an oxygen sink (Glud, 2008; Smith et al., 2018; Jørgensen et al., 2022). Henceforth, throughout this paper, we use the term DOP exclusively to refer to the nodule-associated process of oxygen production claimed by Sweetman et al. (2024), rather than the broader suite of established light-independent oxygen-producing pathways.

Beyond biogeochemistry, the assignment of a novel oxygen-generating role to polymetallic nodules carries broader societal and policy implications. The finding was published at a critical juncture in the development of international regulations for deep-sea mining. DOP was subsequently discussed by council members during the International Seabed Authority’s 29th annual session (IISD, 2024) and cited by the United Nations Scientific Advisory Board as a potential challenge to long-standing assumptions about oxygen production on Earth (UN Scientific Advisory Board, 2024). The study has also been widely amplified in public-facing materials, including NGO campaigns and viral explainer videos (e.g., Miles, 2024; Young, 2024). Together, these responses have propelled the publication into the top 5% of all research outputs scored by Altmetric (Altmetric, 2025), reflecting its disproportionate influence on science-policy discourse.

The far-reaching influence of Sweetman et al. (2024) is perhaps unsurprising, given the broad speculative framing within the study. The authors suggest that DOP may offer insights into biological evolution and the oxygenation of Earth—despite the fact that oxygen is a known prerequisite for polymetallic nodule formation (Burns and Mee Burns, 1975). They have since proposed DOP as a possible mechanism to support life on extraterrestrial planetary bodies (Boston University, 2024). Such speculative extensions, though attention-grabbing, remain unsupported by the data presented in the study.

Despite its high visibility and circulation, the DOP observation remains unreplicated. The experimental procedures, data presentation, and interpretation have been subject to previous critique (Denny et al., 2024; Downes et al., 2024; Nakamura, 2024; Tengberg et al., 2024; Cuesta and Jaspars, 2025). Here, we synthesize and expand upon those concerns. We focus specifically on the inconsistency with comparable studies, flaws in the proposed mechanism, and evidence of experimental artefact. Taken together, these issues call into question the validity of the DOP claim and its relevance to our current understanding of abyssal biogeochemical processes.

2 Divergence from existing observations

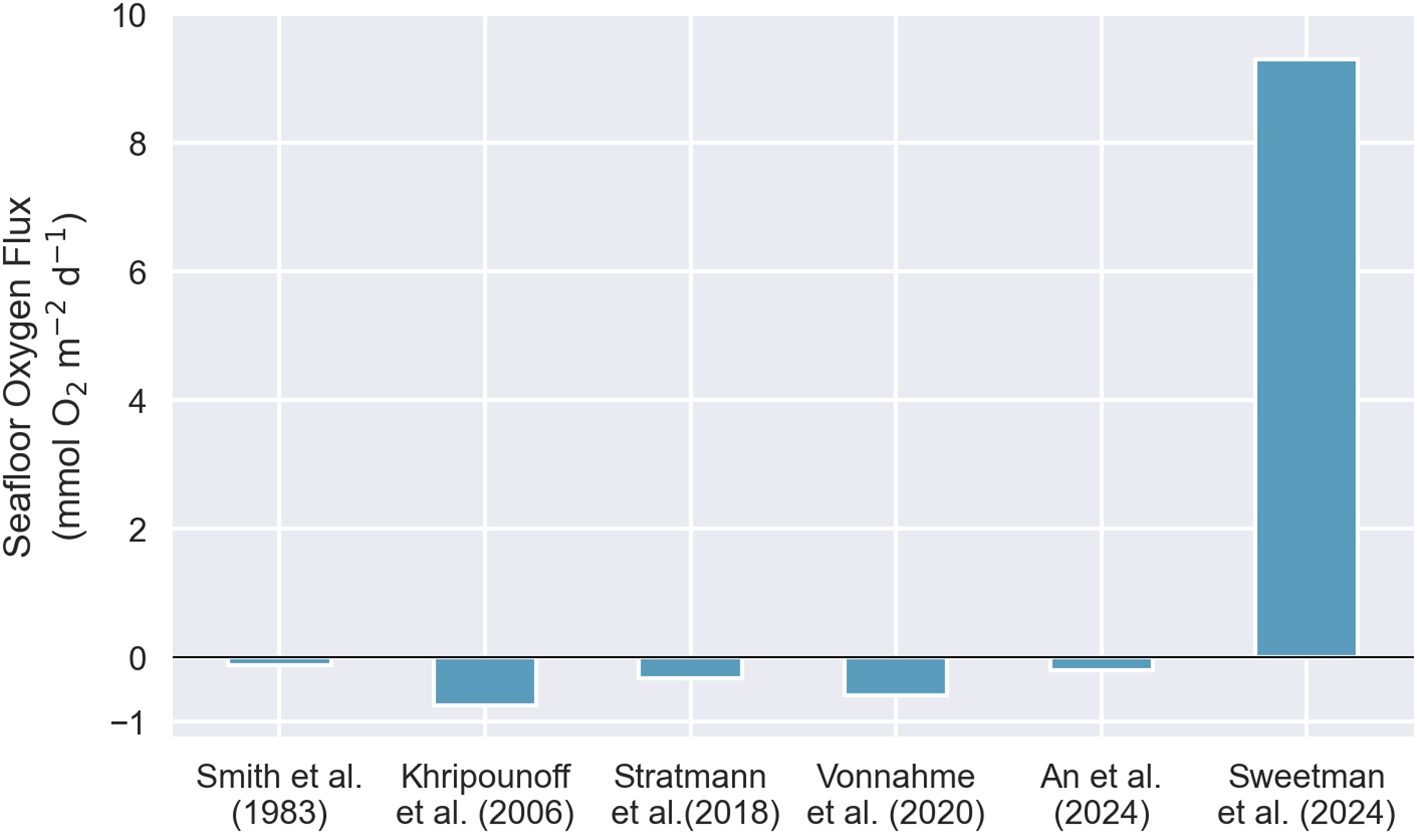

To date, no other study has independently observed DOP. Numerous investigations of seafloor oxygen fluxes using benthic chamber landers—functionally similar to the benthic chamber lander used by Sweetman et al. (2024)—have been conducted in polymetallic nodule-bearing regions across the Pacific, including the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), the Peru Basin, and sites in the central and eastern North Pacific (Smith et al., 1983; Khripounoff et al., 2006; Stratmann et al., 2018; Vonnahme et al., 2020; An et al., 2024). All of these studies measured oxygen consumption at rates consistent with the global average for the abyssal zone (0.8 ± 0.8 mmol O2 m-2 d-1; Jørgensen et al., 2022). Sweetman et al. (2024), whose study was also conducted in the CCZ, acknowledge that their findings diverge from previous abyssal seafloor observations in general, but they do not reference or engage with the specific comparable studies conducted at nodule-rich sites, all of which consistently show no evidence of oxygen production (Figure 1). When considered against the prevailing body of evidence, the DOP result stands out as anomalous.

Figure 1

Comparison of seafloor oxygen fluxes measured in situ using benthic chamber landers deployed in polymetallic nodule-rich areas.

3 Questioning the proposed mechanism

The mechanism proposed by Sweetman et al. (2024)—that polymetallic nodules act as natural batteries capable of driving seawater electrolysis—is fundamentally at odds with Thermodynamics. The splitting of water into oxygen and hydrogen is a highly endergonic reaction, with a standard Gibbs free energy change of +237 kJ mol-1 H2O and cannot proceed spontaneously. Spontaneous occurrence of a reaction with a positive change of Gibbs free energy violates the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Water splitting into H2 and O2 can of course be forced, but this requires a source of energy that can push the system uphill in Gibbs free energy. Invoking nodules as “geo-batteries” without any evidence to be found of what that source of energy would be, violates the First Law of Thermodynamics. The authors claim that the energy required would come from an “internal redistribution” of electrons within the nodules, yet no energy source capable of generating the necessary potential difference to drive such redistribution was identified.

An alternative to water splitting would be oxidation of water to O2 by an oxidant stronger than O2 itself, either electrochemically (one metallic nodule, or region of a metallic nodule, acting as anode where water is oxidized, another acting as cathode where that oxidant would be reduced) or by direct reaction between water and that oxidant (in which case, the polymetallic nodules would be irrelevant). While a range of reactive oxygen species—such as hydrogen peroxide—are produced biologically as intermediary byproducts of aerobic respiration, their concentrations in the deep-sea are extremely low and far below those required to drive measurable oxygen production at the rates reported by Sweetman et al. (2024).

Environmental conditions at abyssal depths do not improve feasibility for electrolysis. High pressure increases the Gibbs free energy due to gas compression effects, and low temperatures marginally increase entropy gains but do not shift the overall reaction toward spontaneity. Moreover, the presence of chloride ions (Cl-) in seawater introduces a competing oxidation pathway. Chloride is preferentially oxidized to chlorine gas (Cl2) due to faster kinetics, making selective oxygen production highly improbable without tightly controlled conditions—conditions that do not exist in the deep ocean.

The interpretation of measured voltages across nodules as evidence of electrolysis is similarly flawed. Any two conductive materials immersed in an electrolyte exhibit a potential difference—this alone is not indicative of electrolysis. Even under ideal laboratory conditions, electrolysis requires an external power source supplying > 1.23 V (typically at least 1.5 V with a good electrocatalyst) to overcome thermodynamic and kinetic barriers. The voltages reported by Sweetman et al. (2024) fall well below the threshold required to drive water electrolysis. While they claim a maximum of 0.95 V, this apparent outlier is not shown in the main figure where the maximum is just 0.24 V—far below the threshold required even with an ideal electrocatalyst with infinitely fast kinetics (1.23 V). In addition, no measurements of hydrogen gas—the co-product of water electrolysis—were conducted. Given that hydrogen and oxygen are produced at a fixed ratio (2:1) during water splitting, detecting hydrogen is essential to confirm that electrolysis occurred. Given the theoretical inconsistencies and absence of supporting evidence, it is surprising that electrolysis was identified as the mechanism underlying the apparent oxygen increases.

4 A case of experimental artefact?

The instrument Sweetman et al. (2024) used to measure oxygen production at the seafloor was an autonomous benthic lander that incubated a small section of the seafloor together with the overlying bottom water. Initial oxygen concentrations recorded in their incubation chambers—measured by both sensors and Winkler titrations—did not agree, varied widely among incubations, and were consistently higher than the ambient bottom water. In their incubations conducted in the NORI-D area of the CCZ, Sweetman et al. (2024) report initial oxygen chamber concentrations of 161–246 µM. This 85 µM range is implausible for bottom-water in deep-sea environments. Over the same period (2019–2022), bottom-water oxygen measured across several sites in NORI-D narrowly ranged 14 µM (145–159 µM) (Downes et al., 2024), consistent with long-term observations for the southeastern CCZ (~144–170 µM; Washburn et al., 2021).

Such unrealistically high and highly variable initial chamber oxygen concentrations reported by Sweetman et al. (2024) are diagnostic of inadequate chamber ventilation (i.e., failure to fully exchange the chamber volume with ambient bottom water before sealing) a condition that can allow for artefacts such as contamination from overlying water or air trapped at the surface. If chambers do not begin incubations at ambient bottom-water concentrations, they cannot have been properly ventilated. Kononets et al. (2021) provide clear examples of the artefacts arising from inadequate chamber ventilation; in one case, trapped air bubbles produced an initial rise in chamber oxygen that resembles the pattern reported by Sweetman et al. (2024). A trapped air bubble on the order of 0.1–0.2 L (≈ 1% of the 12.1 L chamber volume at the surface), would contain enough oxygen to explain their highest oxygen increase.

Sweetman et al. (2024) argue that trapped air would dissolve too rapidly to generate the observed patterns of oxygen increases that, in some cases persist for several hours. However, this argument implicitly assumes complete dissolution into the chamber. In reality, bubble collapse under high pressure can generate pockets of water supersaturated with oxygen within the valves, tubing, or other small auxiliary components attached to the chambers. Diffusion of oxygen from such finite supersaturated reservoirs into the chamber would produce a non-renewing, rectangular-hyperbolic increase consistent with the curves reported by Sweetman et al. (2024).

Despite initial chamber oxygen concentrations that clearly indicate poor ventilation and the presence of artefact, Sweetman et al. (2024) do not provide credible empirical evidence to rule out the benthic chamber lander itself as the source of the observed oxygen increases. While the authors acknowledge that the non-linear and non-continuous pattern of the DOP observations suggests the lander may be stimulating oxygen production, they propose that the bow wave generated upon seafloor contact exposes nodule surfaces that facilitate electrolysis. However, no negative control experiments—incubations without nodules to confirm an absence of oxygen production—are reported in Sweetman et al. (2024) to validate the claim.

Notably, such negative controls were in fact conducted: oxygen concentrations increased during deployments on the same cruise using the same benthic chamber lander, in which chambers were closed above the seafloor without penetrating the sediment—so-called closed-bottom chamber experiments. Although these results were omitted from Sweetman et al. (2024), they were later reported by Downes et al. (2024), who revealed previously unreported data and meta data showing oxygen increases in chambers containing only bottom water and no nodules. This directly undermines the central hypothesis and instead implicates the instrument itself as the source of the DOP signal.

Sweetman et al. (2024) also report chamber incubations from the western CCZ as evidence of DOP, despite a prior publication of the same dataset (i.e., Cecchetto et al., 2023) explicitly stating that no nodules were present in those chambers (Downes et al., 2024; Tengberg et al., 2024). Since these deployments lacked nodules—the proposed oxygen source—they constitute de facto negative controls. Yet, despite oxygen increasing in the absence of nodules, Sweetman et al. (2024) paradoxically present these results as supporting evidence for the DOP hypothesis.

Taken together, these omissions and misrepresentations cast serious doubt on the validity of the experimental evidence for DOP. The mismatch between initial chamber oxygen concentrations and ambient bottom water demonstrates inadequate chamber ventilation. The fact that oxygen increased during control experiments when the chambers contained no nodules demonstrates that the DOP signal originates from the chamber lander itself—most plausibly from residual air contamination. Such an inconsistent artefact would also explain the large variance in both the initial oxygen concentrations and the magnitude of the oxygen increases reported by Sweetman et al. (2024).

5 Conclusions

The theory of dark oxygen production proposed by Sweetman et al. (2024) is unfounded and contradicts the data presented as evidence, the established scientific literature, and the Laws of Thermodynamics. Five independent studies using comparable benthic chamber methods in nodule-rich regions (i.e., Smith et al., 1983; Khripounoff et al., 2006; Stratmann et al., 2018; Vonnahme et al., 2020; An et al., 2024) did not observe oxygen production consistent with the DOP hypothesis. The proposed mechanism—seawater electrolysis driven by polymetallic nodules at voltages < 1.23 V—lacks credible evidence and violates the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics. Specifically, the study fails to identify a viable energy source, demonstrate the presence of a strong oxidant, or report hydrogen production as would be expected from electrolysis. Furthermore, key omissions, including data from control experiments showing that the DOP signal originates from the benthic chamber lander itself—not the nodules—strongly indicates that the reported oxygen increases are experimental artefact rather than a genuine geochemical process.

Given the extraordinary nature of the DOP claim, the narrative built around it warranted far more robust empirical support. Its presentation—detached from the relevant body of opposing literature—elevated DOP into policy discourse, lending credibility to a hypothesis that is incompatible with established knowledge and inconsistent with experimental evidence. While the broader societal consequences of high-profile, questionable scientific claims are difficult to quantify—particularly in policy-relevant domains like deep-sea mining—the financial cost of research funding potentially misallocated on the basis of speculative assertions is far more tangible.

Statements

Author contributions

PD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AD: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. AT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PH: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. L-KT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. WS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. MJ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. FS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

AD, L-KT, and WS were employed by Adepth Minerals. AT was employed by Aanderaa-Xylem. PD, MC, FS, AW, and JB are employees of The Metals Company. LM was an employee of The Metals Company during the preparation of this manuscript. The Metals Company partly funded the study reported in Sweetman et al. 2024 through its subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. NORI. NORI holds exploration rights to the NORI-D contract area in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, regulated by the International Seabed Authority and sponsored by the Government of Nauru.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Altmetric (2025). Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor Overview of attention for article published in Nature Geoscience, July 2024. Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor Overview of attention for article published in Nature Geoscience, July 2024. Available online at: https://nature.altmetric.com/details/165583015 (Accessed July 21, 2025).

2

An S.-U. Baek J.-W. Kim S.-H. Baek H.-M. Lee J. S. Kim K.-T. et al . (2024). Regional differences in sediment oxygen uptake rates in polymetallic nodule and co-rich polymetallic crust mining areas of the Pacific Ocean. Deep. Sea. Res. Part I.: Oceanogr. Res. Papers.207, 104295. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2024.104295

3

Boston University (2024). Oxygen Produced in the Deep Sea Raises Questions about Extraterrestrial Life on Other Planets ( Boston University). Available online at: https://www.bu.edu/articles/2024/deep-sea-oxygen-raises-questions-about-extraterrestrial-life/ (Accessed July 21, 2025).

4

Burns R. G. Mee Burns V. (1975). Mechanism for nucleation and growth of manganese nodules. Nature255, 130–131. doi: 10.1038/255130a0

5

Cecchetto M. M. Moser A. Smith C. R. van Oevelen D. Sweetman A. K. (2023). Abyssal seafloor response to fresh phytodetrital input in three areas of particular environmental interest (APEIs) in the western clarion-clipperton zone (CCZ). Deep. Sea. Res. Part I.: Oceanogr. Res. Papers.195, 103970. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2023.103970

6

Cuesta A. Jaspars M. (2025). Is abyssal dark oxygen production even possible at all? EarthArXiv (California Digital Library, University of California). doi: 10.31223/X5DT6P

7

Denny A. Svellingen W. Trellevik L.-K. (2024). Critical Examination of “Evidence of Dark Oxygen Production at the Abyssal Seafloor”. EarthArXiv (California Digital Library, University of California). doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30239.37289

8

Dershwitz P. Bandow N. L. Yang J. Semrau J. D. McEllistrem M. T. Heinze R. A. et al . (2021). Oxygen Generation via water splitting by a novel biogenic metal ion-binding compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.87, e00286–e00221. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00286-21

9

Downes P. Marsh L. Bento J. Webber A. Clarke M. (2024). Contributions to the discussion of novel detection of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor. EarthArXiv (California Digital Library, University of California). doi: 10.31223/X5WB0X

10

Ettwig K. F. Speth D. R. Reimann J. Wu M. L. Jetten M. S. M. Keltjens J. T. (2012). Bacterial oxygen production in the dark. Front. Microbiol.3. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00273

11

Glud R. N. (2008). Oxygen dynamics of marine sediments. Mar. Biol. Res.4, 243–289. doi: 10.1080/17451000801888726

12

Gutsalo L. K. (1970). Radiolysis of water as the source of free oxygen in the underground hydrosphere. Geochem. Int. (Engl. Transl.)8, 897–903.

13

IISD (2024). Summary report 15 July – 2 August 2024 ( International Institute for Sustainable Development). Available online at: https://enb.iisd.org/international-seabed-authority-isa-council-29-2-summary (Accessed July 21, 2025).

14

Jørgensen B. B. Wenzhöfer F. Egger M. Glud R. N. (2022). Sediment oxygen consumption: Role in the global marine carbon cycle. Earth-Sci. Rev.228, 103987. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103987

15

Khripounoff A. Caprais J.-C. Crassous P. Etoubleau J. (2006). Geochemical and biological recovery of the disturbed seafloor in polymetallic nodule fields of the Clipperton-Clarion Fracture Zone (CCFZ) at 5,000-m depth. Limnol. Oceanogr.51, 2033–2041. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2033

16

Kononets M. Tengberg A. Nilsson M. Ekeroth N. Hylen A. Robertson E. K. et al . (2021). In situ incubations with the Gothenburg benthic chamber landers: Applications and quality control. J. Mar. Syst.214, 103475. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2020.103475

17

Miles B. (2024). We Just Discovered “Dark” Oxygen on Earth - Breakthrough Explained. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iixZ6UptVNo (Accessed July 21, 2025).

18

Nakamura K. (2024). Questioning Dark Oxygen Production in the Deep-sea Ferromanganese Nodule Field. EarthArXiv (California Digital Library, University of California). doi: 10.31223/X5PH7F

19

Rousseaux C. Gregg W. (2013). Interannual variation in phytoplankton primary production at a global scale. Remote Sens.6, 1–19. doi: 10.3390/rs6010001

20

Ruff S. E. Schwab L. Vidal E. Hemingway J. D. Kraft B. Murali R. (2024). Widespread occurrence of dissolved oxygen anomalies, aerobic microbes, and oxygen-producing metabolic pathways in apparently anoxic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.100, fiae132. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiae132

21

Sauvage J. F. Flinders A. Spivack A. J. Pockalny R. Dunlea A. G. Anderson C. H. et al . (2021). The contribution of water radiolysis to marine sedimentary life. Nat. Commun.12, 1297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21218-z

22

Smith K. L. Jr. Laver M. B. Brown N. O. (1983). Sediment community oxygen consumption and nutrient exchange in the central and eastern North Pacific. Limnol. Oceanogr.28, 882–898. doi: 10.4319/lo.1983.28.5.0882

23

Smith K. L. Ruhl H. A. Huffard C. L. Messie M. Kahru M. (2018). Episodic organic carbon fluxes from surface ocean to abyssal depths during long-term monitoring in NE Pacific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.115, 12235–12240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814559115

24

Stanley R. H. R. Kirkpatrick J. B. Cassar N. Barnett B. A. Bender M. L. (2010). Net community production and gross primary production rates in the western equatorial Pacific. Global Biogeochem. Cycles.24. doi: 10.1029/2009GB003651

25

Stratmann T. Voorsmit I. Gebruk A. Brown A. Purser A. Marcon Y. et al . (2018). Recovery of Holothuroidea population density, community composition, and respiration activity after a deep-sea disturbance experiment. Limnol. Oceanogr.63, 2140–2153. doi: 10.1002/lno.10929

26

Sweetman A. K. Smith A. J. de Jonge D. S. W. Hahn T. Schroedl P. Silverstein M. et al . (2024). Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor. Nat. Geosci.17, 737–739. doi: 10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8

27

Tengberg A. Kononets M. Hall P. O. J. (2024). “ Rebuttal of sweetman,” in Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor. Eds. A.KSmithA. J.de JongeD. S. W.et al. EarthArXiv (California Digital Library, University of California). doi: 10.31223/X5T708

28

UN Scientific Advisory Board (2024). Brief of the Scientific Advisory Board on Deep-Sea Mining: What is Deep-Sea Mining? Why It Matters? Available online at: https://www.un.org/scientific-advisory-board/sites/default/files/2025-05/250403-DSM-Brief-Rev-7.pdf (Accessed July 21, 2025).

29

Vonnahme T. R. Molari M. Janssen F. Wenzhöfer F. Haeckel M. Titschack J. et al . (2020). Effects of a deep-sea mining experiment on seafloor microbial communities and functions after 26 years. Sci. Adv.6, eaaz5922. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz5922

30

Washburn T. W. Jones D. O. B. Wei C.-L. Smith C. R. (2021). Environmental heterogeneity throughout the clarion-clipperton zone and the potential representativity of the APEI network. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.661685

31

Xu J. Logan B. E. (2003). Measurement of chlorite dismutase activities in perchlorate respiring bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods54, 239–247. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00058-7

32

Young N. (2024). Dark oxygen discovered in the deep sea spells trouble for seabed mining industry ( Greenpeace Aotearoa). Available online at: https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/story/dark-oxygen-discovered-deep-sea/ (Accessed July 21, 2025).

Summary

Keywords

dark oxygen production, polymetallic nodules, deep-sea geochemistry, science-policy, deep-sea mining

Citation

Downes P, Cuesta A, Denny A, Tengberg A, Hall POJ, Trellevik L-K, Svellingen W, Jaspars M, Webber AP, Sales de Freitas F, Bento JP, Marsh L and Clarke M (2025) Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence: evaluating nodule-associated dark oxygen production. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1721853. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1721853

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

18 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Gordon T. Taylor, Stony Brook University, United States

Reviewed by

Beate Kraft, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Ronnie Nohr Glud, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Downes, Cuesta, Denny, Tengberg, Hall, Trellevik, Svellingen, Jaspars, Webber, Sales de Freitas, Bento, Marsh and Clarke.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patrick Downes, patrick.downes@metals.co

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.