Abstract

Nutritional supplementation can improve coral recruit performance by enhancing growth and survival, two key metrics for the success of sexually propagated coral restoration. We investigated the effects of three feeding regimes (Control, 1 feed/week, and 2 feeds/week) using powdered commercial coral feed on Galaxea fascicularis recruits over a 23-week period in land-based nurseries. Growth was assessed weekly as budding polyps per recruit, and survival was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank tests. Treatment effects on growth were further evaluated using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (Gamma distribution with log link), including Treatment, Week, and their interaction. Survival differed significantly among treatments, with the twice-weekly feeding group consistently exhibiting higher survival rates than the Control and once-weekly feeding groups. After 23 weeks, survival was highest under twice-weekly feeding (41.3%), followed by once-weekly feeding (29.2%) and no feeding (24.7%). Growth analyses revealed significant main effects of Treatment and Week, as well as a significant Treatment × Week interaction, indicating accelerated growth under more frequent feeding regimes. Our findings demonstrate that frequent supplemental feeding substantially improves both survival and growth of G. fascicularis recruits in ex situ nurseries. Twice-weekly feeding provided the greatest benefits, highlighting the importance of optimized nutritional regimes for coral propagation. These results offer practical guidance for improving husbandry protocols and enhancing the efficiency of sexually propagated coral restoration efforts.

1 Introduction

Coral reefs occupy less than 0.2% of the ocean yet support nearly a quarter of all marine species, providing food, protection, and essential physical and chemical settlement cues for a wide range of organisms (Barth et al., 2015; Lecchini et al., 2014; Li, 2019). Many scleractinian corals form the reef substratum and create essential habitats that function as spawning, nursery, and feeding grounds for marine life (Moberg and Folke, 1999; Roik et al., 2016). Beyond their ecological roles, coral reefs deliver critical services including fisheries production, tourism value, and coastal protection by acting as natural breakwaters (Lachs and Oñate-Casado, 2020; Mehvar et al., 2018). However, despite their importance, coral reefs are experiencing rapid global decline driven by rising sea surface temperatures, storm intensity, overfishing, nutrient enrichment, sedimentation, and invasive species (Cheal et al., 2017; Riegl et al., 2009; Norström et al., 2009; Mcmanus and Polsenberg, 2004). Nutrient imbalances, such as phosphate starvation, further increase coral bleaching susceptibility (D’Angelo and Wiedenmann, 2012).

Active coral restoration’s earliest and most common method is direct transplantation, where scleractinian corals are fragmented from healthy donor colonies and relocated to degraded reefs (Boström-Einarsson et al., 2020). Although effective for rapid visual recovery, transplantation is limited by donor availability, labor intensity, and reduced genetic diversity, which may compromise long-term resilience to bleaching and disease (Baums, 2008; Van Oppen et al., 2015). To overcome this limitation, techniques involving coral spawning and gamete capture have emerged as scalable methods for active coral restoration, offering the added benefit of enhancing genetic diversity and targeting species of interest (Randall et al., 2020). However, this method faces several challenges due to the high natural mortality of newly settled coral recruits and the cryptic, unpredictable nature of coral spawning, which demands advanced expertise, specialized technology, and intensive data collection (Edmunds and Riegl, 2020).

Ex situ coral aquaculture has emerged as a powerful tool to address some of these challenges by providing stable, highly controlled rearing conditions. In closed or semi-open systems, parameters such as light, temperature, flow, and predation risk can be tightly regulated, improving coral growth, survival, and stress tolerance (Craggs et al., 2020; Guest et al., 2014). These systems also enable targeted propagation of species with ecological or restoration value. Galaxea fascicularis is an ideal candidate for coral restoration due to its high energy efficiency, maintaining lipid reserves during periods of starvation (Borell et al., 2008), and naturally high survival rates even under minimal feeding (Van Os et al., 2012). These traits make it a useful model species for understanding the nutritional requirements of early recruits and for developing husbandry practices that can enhance restoration efficiency.

Among the environmental factors influencing coral growth, heterotrophic nutrition plays a critical yet variable role. Corals acquire energy both autotrophically, via photosynthesis from endosymbiotic zooxanthellae, and heterotrophically, through ingestion of particulate and dissolved organic matter (Osinga et al., 2011; Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès, 2009). For many species, heterotrophy can contribute 30–50% of total energy requirements, particularly under stress or low-light conditions when photosynthesis is limited (Grottoli et al., 2006; Anthony and Fabricius, 2000). Importantly, heterotrophic feeding becomes especially valuable during the early post-settlement period, when recruits are most vulnerable to predation, competition, and starvation (Morse et al., 1988; Edmunds and Carpenter, 2001). Survival can be enhanced through pre- and post-settlement methods, such as high-quality water filtration and conditioning settlement materials with CCA (Guest et al., 2014), introducing zooxanthellae to larvae (Petersen et al., 2008), and co-culturing grazers to consume combatant turfing algae (Craggs et al., 2019). Conlan et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of nutrition in early post-settlement coral recruits, reporting increased growth and survival in several Acroporidae species when maintained in unfiltered seawater, likely due to the presence of suspended particulates, plankton, and dissolved nutrients. Given the high mortality typically observed in early post-settlement corals, the effects of feeding regimes on survival and development remain unclear. Species with larger, mounded polyps often exhibit higher heterotrophic capacity than branching forms (Palardy et al., 2005), suggesting that nutritional needs and responses may vary among taxa. For G. fascicularis, nutritional supplementation has been shown to enhance survival and can increase growth, although in mature colonies more frequent feeding chiefly increases ingestion rather than growth (Van Os et al., 2012). These findings highlight the importance of tailoring nutritional inputs to both species and developmental stage, ensuring that feeding strategies optimize physiological benefits rather than simply increasing intake. However, the effects of feeding frequency during the earliest developmental windows remain poorly resolved.

To meet the nutritional needs of corals in ex situ systems, practitioners use a range of feeds, from live to artificial diets. Live feeds such as Artemia, rotifers, microalgae, and plankton cultures can enhance coral health, survival, and growth (Conlan et al., 2017; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2003; Palardy et al., 2005; Puntin et al., 2023), but they require specialized infrastructure and continuous maintenance, and are vulnerable to issues such as Vibrio sp. contamination in Artemia cultures (López-Torres and Lizárraga-Partida, 2001; Sahandi et al., 2025), which can increase coral susceptibility to bleaching (Mass et al., 2024). In contrast, artificial powdered feeds have been shown to improve coral growth across multiple species (Ding et al., 2021; Forsman et al., 2012) while being easier to store, safer to use, and more practical at scale. Consequently, commercial diets offer an accessible and cost-effective alternative for ex situ coral restoration programs.

This study focuses on the early post-settlement phase, the most vulnerable stage in the life history of broadcast-spawning corals. It aims to provide insight into optimal husbandry strategies that enhance the survivability and growth of coral recruits through varied feeding regimes. We test the growth and survival of G. fascicularis recruits over 23 weeks under three feeding treatments (no feeding, feeding once weekly, and feeding twice weekly), while maintaining all recruits in unfiltered seawater. We hypothesize that increased feeding frequency will (i) promote growth through the development of new polyps, and (ii) reduce recruit mortality.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Spawning and development

G. fascicularis colonies were selected from the reef surrounding Kunfunadhoo Island in Baa Atoll, Maldives (5.1122° N, 73.0782° E) after gamete assessments, following the methods shown in Puntin et al. (2023). Colonies with mature gametes were collected one week prior to the predicted spawning event, and these predictions were based upon anecdotal evidence of the timing of this species spawning in previous years upon this reef (Soneva, 2022-2025). Eight female colonies and one male colony were selected based on the availability of mature gametes on the reef at the time of collection. This resulted in a female-biased ratio, which is common in broadcast-spawning work because a single male colony typically produces more than sufficient sperm to fertilize the eggs of multiple females (Wallace et al., 1990). Therefore, despite the uneven sex ratio, the number of males was not expected to limit fertilization success. The selected colonies were placed in a 300 L acrylic tank within the land-based nursery. Unfiltered seawater was supplied to this tank directly from the ocean, flushing the tank at a rate of 120 liters per hour, maintaining stable temperature and salinity (28.44°C ± 0.66 and 32.64 ppt ± 1.62, respectively). The tank was positioned outdoors so colonies were exposed to natural environmental cues such as sunset and moonrise. Colonies were observed each night for signs of spawning, isolating the tank from all water circulation to ensure no gamete loss through the overflow-style filtration. Six female colonies and one male colony of G. fascicularis spawned on the eighth night after the full moon, 28th April 2024. Following the release of gametes, steady aeration (~3 bubbles/second) along the tank walls increased circulation and helped separate the bundles, and all gametes remained in this same 300-L tank for the entire fertilization and early developmental period. Fertilization success was checked every 15 minutes until it exceeded 80%, after which the tank was left undisturbed overnight. Fourteen hours later, a subsample of 500 embryos was assessed, with an average fertilization success of 96%.

2.2 Larval settlement

Gametes remained in the original tank conditions to continue development with twice-daily water changes to ensure optimal water quality. One thousand ceramic plugs covered the bottom of the tank to provide an optimal settlement medium for the larvae. Non-target crustose coralline algae (CCA) were collected from the reef without preference for species identity, crushed with a pestle and mortar, and lightly dusted across each plug to promote larval settlement (Grasso et al., 2011), and reducing the growth of combatant macroalgae through the release of biochemicals (Gomez-Lemos and Diaz-Pulido, 2017). This approach was selected based on prior trials conducted during earlier spawning events at the same site, where crushed CCA application was found to reliably induce settlement without requiring dilution or specialized dispersion techniques. Larval settlement was first observed seven days after fertilization (+7), with all larvae settled after day ten (+10); the tank was then returned to an open system to allow for the free flow of fresh seawater. Two parental colonies of G. fascicularis remained in this tank during development and settlement, both selected based on visual health (no tissue necrosis or paling), to assist in symbiont zooxanthellae uptake (Petersen et al., 2008) and to support photosynthetic processes early in recruit development (Osinga et al., 2011).

2.3 Experimental setup

A total of 180 settlement plugs were randomly selected from the acrylic tank ~4 weeks post-spawning, with an average recruits per plug (n(T) = 1964). Three feeding treatments were trialed across 18 trays (six trays per treatment), holding 10 plugs each. A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for pairwise comparisons was used to ensure no significant variation in recruit densities on plugs between treatments. This study used pre-prepared commercial reef food for each feeding treatment. We fed recruits a commercial coral diet (BeneReef; Benepets). Lot and expiry information were not recorded at the time of use. Manufacturer-reported proximate composition: crude protein 25.5% (min), crude fat 4.7% (min), crude fiber 44% (max), crude ash 5.0% (max), moisture 5.5% (max); declared probiotics ≥1×10^6 CFU g-1 (Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bacillus spp.). The full ingredient list is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Treatments included: no feeding (“Control”), once-weekly feeding (“1 Feed”), and twice-weekly feeding (“2 Feeds”). All recruits remained in a single 300 L holding tank for the full 23-week experiment, with tray positions re-randomized after each feed to avoid spatial bias. The 23-week duration was selected based on facility constraints and aligns with the typical timeframe used in comparable early post-settlement coral recruit studies (Craggs et al., 2019). During each feeding session, trays were transferred into three separate 50 L buckets (one per treatment), each filled with seawater taken directly from the holding tank to ensure identical starting conditions across treatments. Buckets were positioned side-by-side and stirred manually every 15 minutes to maintain an even suspension of food. This setup functioned as a simple flow-through feeding station, where each treatment bucket acted as an isolated feeding chamber while still maintaining identical water quality conditions. Feed was added only to the “1 Feed” and “2 Feeds” buckets, with “2 Feeds” receiving coral food twice weekly and “1 Feed” receiving food once weekly. “Control” trays were placed into their assigned bucket at the same time but without the addition of coral food. Feed was dosed at ~625 mg per 50 L (~12.5 mg L-1) and added 5 minutes prior to introducing trays. Trays remained in their buckets for 1 hour per feeding event, and temperature and salinity were recorded before and after feeding to confirm consistency across treatments (Supplementary Table S2). Together, these steps ensured that feeding frequency was the only experimental variable intentionally manipulated among treatments. Photographs of each plug were taken at the beginning of each week to analyze the total number of recruits and polyps present. We adopted the same metric for growth rates of G. fascicularis, as seen in Van Os et al. (2012), by using the number of new polyps per recruit as a measure of new growth. To track individual polyps and monitor new growth (budding), ImageJ (1.53t) (Schneider et al., 2012) software was used for point counting polyp growth and assessing new growth.

2.4 Statistical analysis

To visualize the survival of coral recruits across treatments, we generated Kaplan–Meier survival curves for each feeding treatment (Kaplan and Meier, 1958) in R (R Core Team, 2023). Survival data were grouped by treatment, and the cumulative survival over time was plotted. Differences in survival across treatments were assessed using a log-rank test (Mantel, 1966). The number of recruits remaining alive at week 23 (final week) was used to compare the treatment effects on survival and growth. At Week 23 (final week), plug-level survival (recruits alive/initial recruits) was analyzed with a beta-binomial GLMM (logit link) including Treatment and initial recruit count (OriginalRec) as fixed effects and a random intercept for Tray to account for clustering. We obtained pairwise contrasts with emmeans (Tukey adjustment) and report model-based survival probabilities. As a robustness check, we also ran a Kruskal–Wallis test (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952) with Dunn’s post-hoc (Dunn, 1964); conclusions were unchanged. Final-week PPR (continuous, positive) was analyzed with a Gamma GLM (log link) with Treatment (and OriginalRec as a covariate, if retained), with pairwise emmeans on the response scale. As a sensitivity analysis for clustering, we re-fit Week-23 PPR with a Gamma GLMM including a random intercept for Tray. The significance of treatment effects on Polyps/Recruit (PPR) was determined by assessing the fixed effects of the model. The effect of feeding treatments on growth rates was evaluated by examining the interaction between treatment and week.

Model assumptions were tested, and violations were addressed by selecting appropriate methods. For PPR analyzes, we tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using Bartlett’s test and Levene’s test (Bartlett, 1937; Levene, 1960). Where assumptions were violated, we used GLMMs instead of ANOVAs. The suitability of models was further evaluated using AIC values, where the model with the lowest AIC was considered the most appropriate (Akaike, 1974). We performed Spearman’s rank correlation tests within each treatment group to evaluate the relationship between initial recruit density with growth and survival (Spearman, 1904). This non-parametric test was used due to the potential for non-linear relationships and ties in the data. We assessed the strength and direction of the correlation for each treatment individually.

3 Results

3.1 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

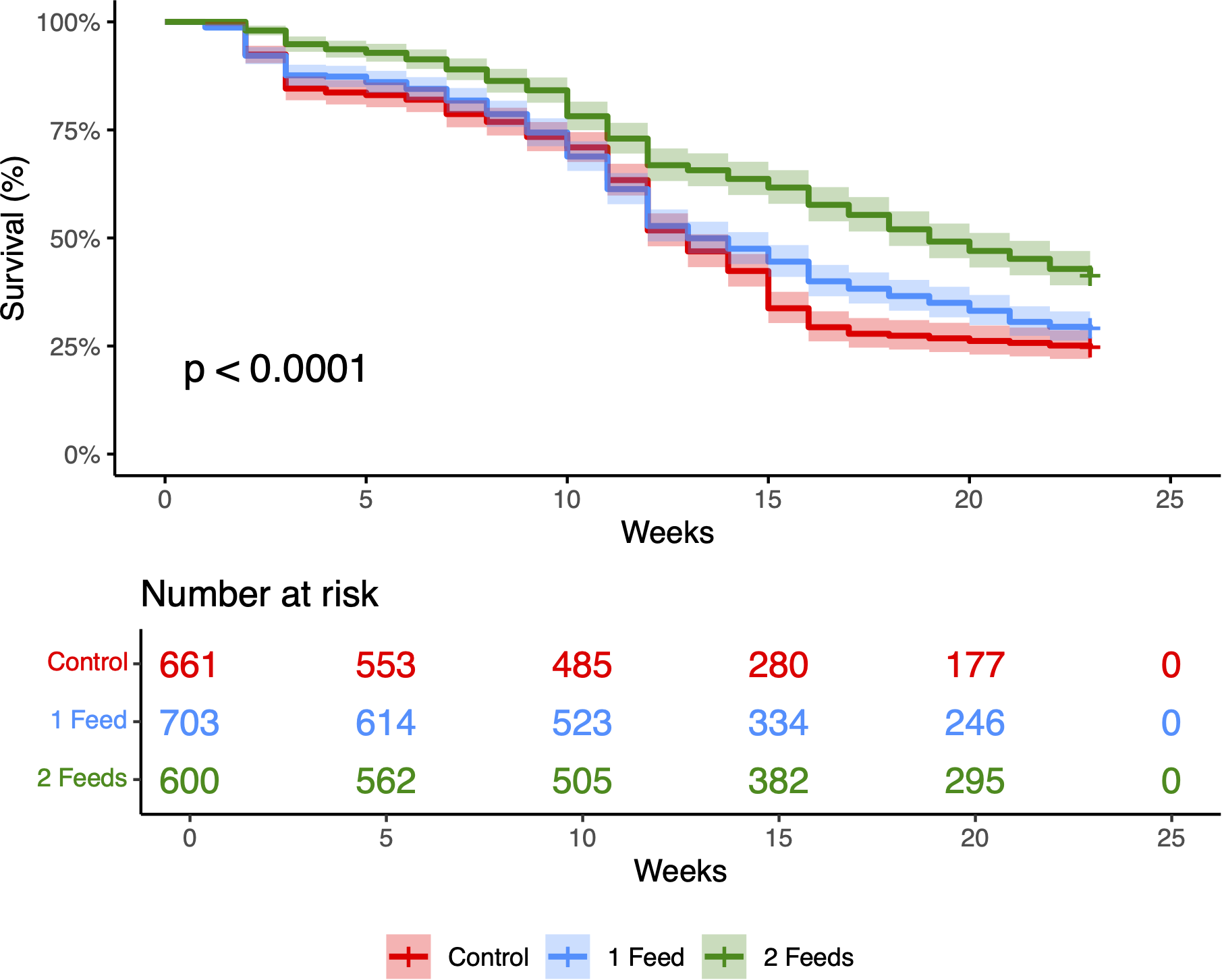

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted for each feeding treatment (“Control”, “1 feed”/week, “2 feeds”/week) to evaluate the survival of coral recruits throughout the experiment. Survival rates were highest in the 2 feeds/week treatment, followed by 1 feed/week, and Control. The log-rank test revealed a significant difference in survival between treatments (χ² = 58.19, df = 2, p = 5.10 × 10-14), indicating that feeding frequency significantly affected recruit survival over time (Figure 1). Global differences among treatments were significant (log-rank χ²(2) = 58.19, p = 5.10 × 10-14). BH-adjusted pairwise tests showed 2 feeds/week > 1 feed/week (p_adj = 3.4 × 10-8) and 2 feeds/week > Control (p_adj = 1.0 × 10-13), whereas 1 feed/week vs Control was not significant (p_adj = 0.054).

Figure 1

Kaplan–Meier survival of Galaxea fascicularis recruits over 23 weeks under three feeding regimes: Control (no feed; n0 = 661, red), 1 feed/week (n0 = 703, blue), and 2 feeds/week (n0 = 600, green). Step curves show survival estimates; shaded bands are 95% CIs. The lower panel reports the cumulative number of mortality events by week. Survival differed among treatments (log-rank χ2 = 58.19, df = 2, p = 5.10 × 10-14); at week 23, KM survival was 41.3% (2 feeds/week), 29.2% (1 feed/week), and 24.7% (Control).

3.2 Final-week survival (beta-binomial GLMM)

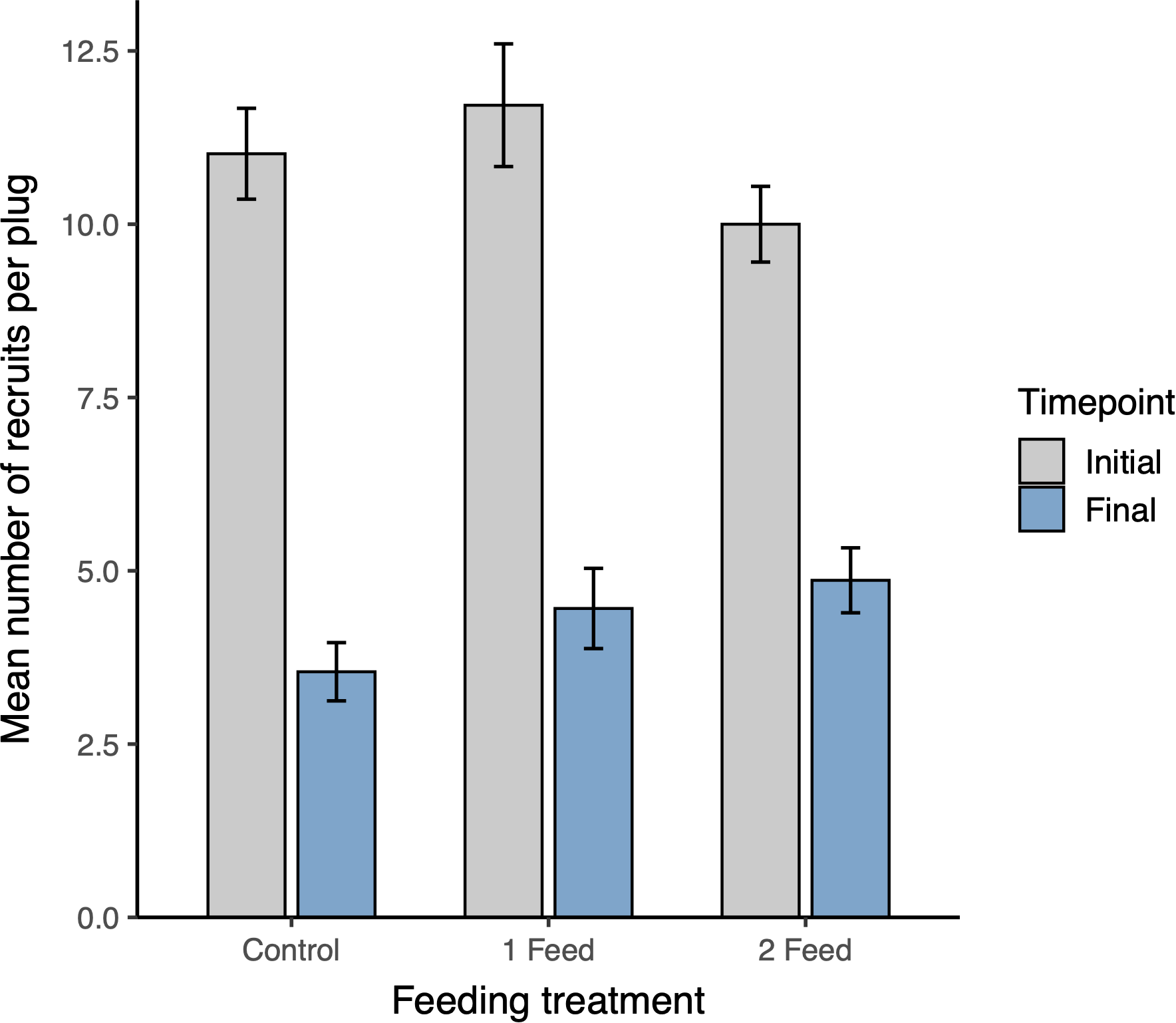

A beta-binomial GLMM with a random intercept for Tray detected higher survival under twice-weekly feeding relative to Control (Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0146) and a marginal increase relative to once-weekly (Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0557); once-weekly did not differ from Control (Tukey-adjusted p = 0.876) (Figure 2). Model-based Week-23 survival probabilities (plug level; 95% CIs) were 0.393 (0.308–0.484) for 2 feeds/week, 0.254 (0.187–0.336) for 1 feed/week, and 0.229 (0.166–0.307) for Control. The random-effect SD for Tray was 0.336 (Var = 0.113), indicating limited residual clustering; inclusion of OriginalRec as a covariate showed a positive trend (p = 0.053) without changing treatment inferences. These patterns matched the KM curves (Figure 1). As a robustness check, Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc gave concordant conclusions.

Figure 2

Mean number of recruits per plug at the start (Week 0; “Initial”, gray) and end (Week 23; “Final”, blue) of the experiment for each feeding treatment (Control, 1 feed/week, 2 feeds/week). Bars show plug-level means (n = 60 plugs per treatment); error bars are ± SE. Initial recruit densities did not differ among treatments (Kruskal–Wallis, p > 0.05). Final counts were highest under 2 feeds/week feeding, consistent with the survival differences in Figure 1.

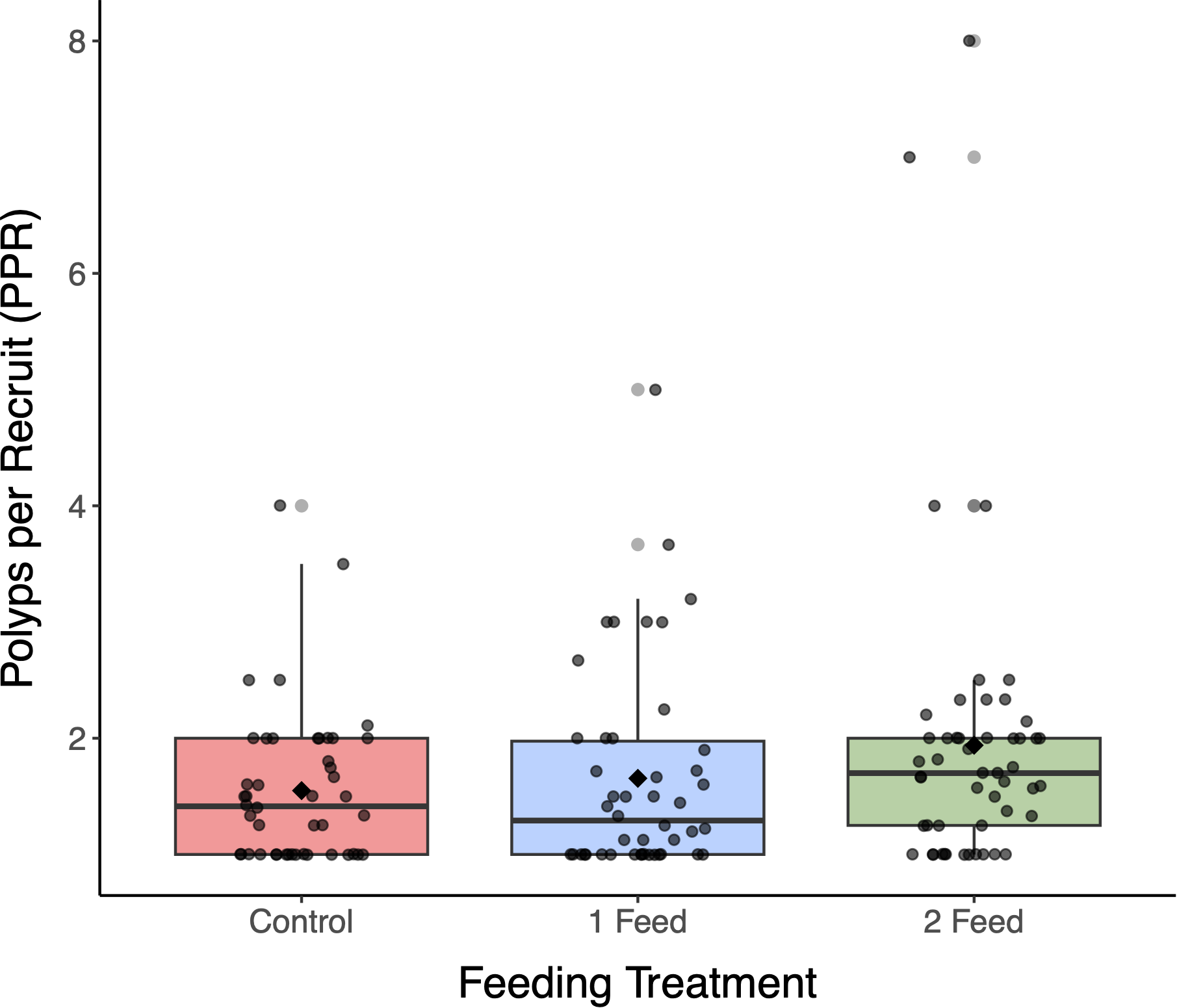

3.3 Polyps per recruit at week 23

At the final week, PPR differed among treatments. 2 feeds/week yielded the highest PPR , exceeding 1 feed/week and Control (; Figure 3). An omnibus model for the week-23 data indicated a treatment effect (Gamma GLM, log link; χ² = 6.18, p = 0.006). Post-hoc contrasts showed higher PPR under 2 feeds/week than under 1 feed/week and Control (both p < 0.05); 1 feed/week vs Control was not significant.

Figure 3

Polyps per recruit at week 23 by feeding regime: Control (n = 46), 1 feed/week (n = 46), and 2 feeds/week (n = 51). Boxes show median and interquartile range; whiskers are 1.5× IQR; points are plug-level values; black diamonds are means. Polyps per recruit differed among treatments (Gamma GLM (log link): χ2 = 6.18, p = 0.006). The 2 feeds/week group had the highest polyps per recruit (mean = 2.34), exceeding 1 feed/week (1.46) and Control (1.23) by +0.88 (+60%) and +1.11 (+90%), respectively (post hoc, p < 0.05). In a tray-aware GLMM sensitivity, the same ordering was recovered but pairwise contrasts were not significant; see Results 3.3.

To evaluate whether tray-level clustering affected results, we refit the Week-23 PPR data using a Gamma-log GLMM with a random intercept for Tray. The estimated marginal means (± 95% CI) were: 2 feeds/week = 1.87 (1.64–2.12), 1 feed/week = 1.69 (1.48–1.93), and Control = 1.54 (1.35–1.76). Although this ordering matched the primary analysis, none of the pairwise Tukey contrasts were statistically significant at α = 0.05 (2 feeds/week vs Control: ratio = 1.21, p = 0.111; 1 feed/week vs Control: ratio = 1.10, p = 0.612; 1 feed/week vs 2 feeds/week: ratio = 0.91, p = 0.560). The random-effect variance was small (SD ≈ 0.053; Gamma dispersion ≈ 0.186), indicating that trays contributed minimal additional variability. Overall, the sensitivity analysis supports that the observed treatment differences are not driven by tray-level clustering.

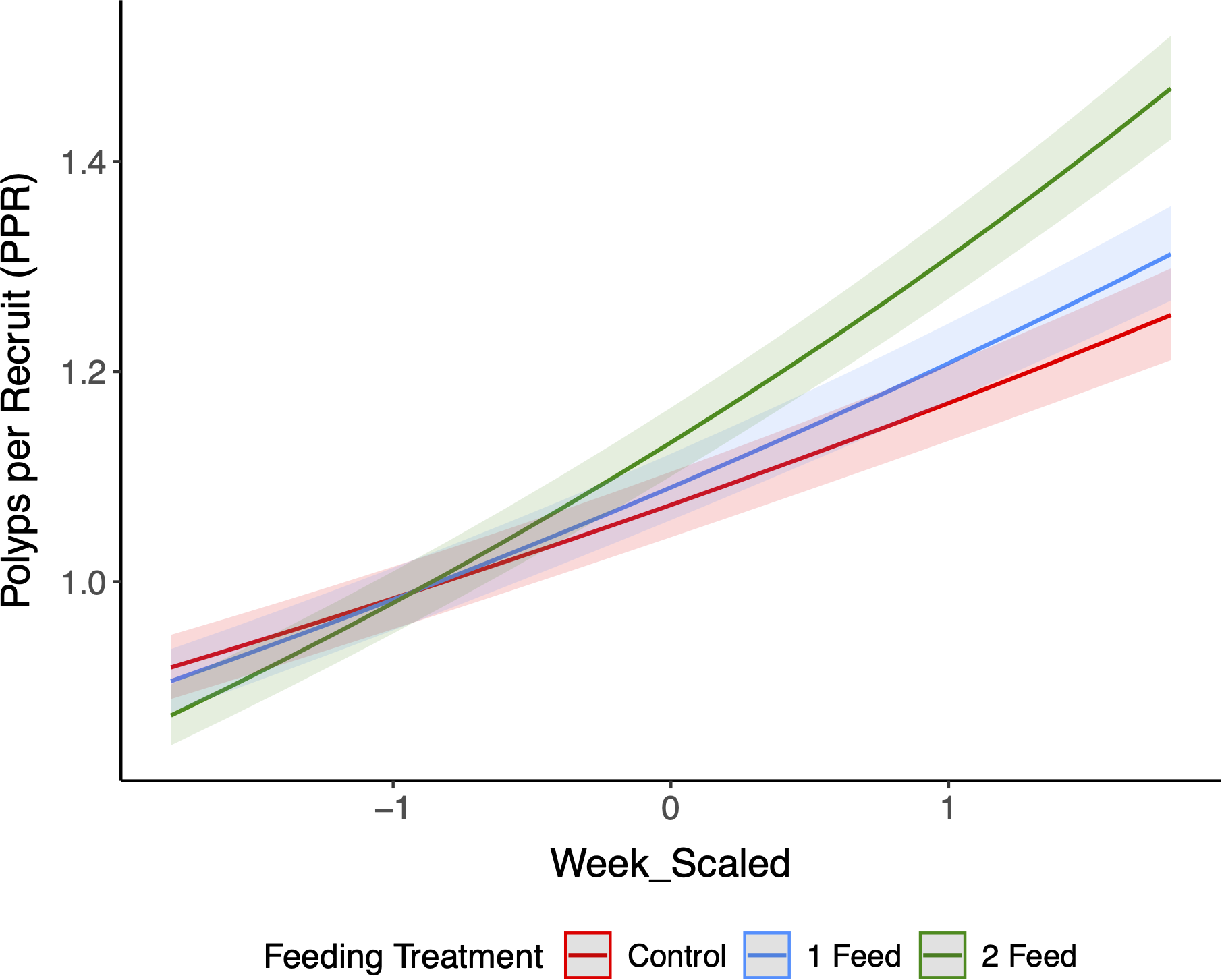

3.4 PPR across weeks (model overview)

Across the full 23-week time series, a Gamma-log GLMM with a random intercept for plug fit the data well (AIC = −1437.8; N = 4,055 observations from 180 plugs; R2_marginal = 0.238, R2_conditional = 0.444). Week had a positive effect on PPR (β = 0.103 ± 0.0049 SE, z = 21.0, p < 2×10-16). The significant Treatment × Week interaction indicates different slopes (growth rates) through time among treatments: relative to 1 feed/week, 2 feeds/week had a steeper week slope (β = 0.0417 ± 0.0068, z = 6.14, p = 8.38×10-10), whereas Control had a shallower slope (β = −0.0165 ± 0.0070, z = −2.35, p = 0.0187). Thus, recruits grew faster over time under twice-weekly feeding and slower under no feeding (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Trajectories of polyps per recruit across the 23-week experiment for Control, 1 feed/week, and 2 feeds/week. Lines are GLMM (Gamma, log link) marginal means with 95% CIs (shaded); random intercept for Plug. The x-axis uses the z-scored week variable (Week_scaled). The Treatment × Week interaction was significant (Wald χ2 test, p < 0.001), indicating faster and sustained increases under 2 feeds/week, with 1 feed/week intermediate and Control lowest.

Interestingly, the largest single-recruit increase was observed in the 2 feeds/week treatment (plug 165), which produced seven additional polyps by week 23 (Figure 5). Initial recruit density did not detectably influence final PPR or survival in this dataset.

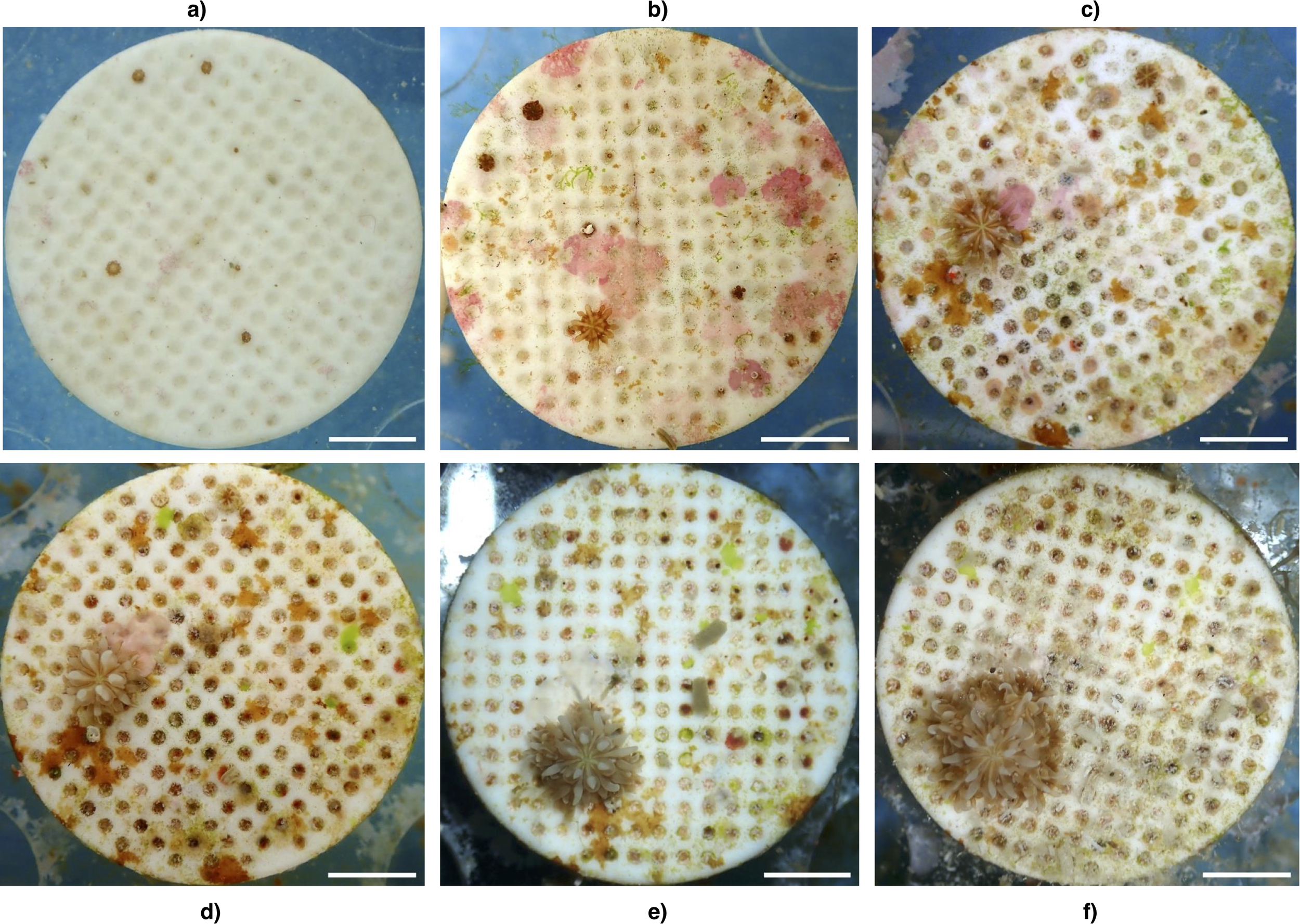

Figure 5

Representative time series of a single Galaxea fascicularis recruit on plug 165 in the 2 feeds/week treatment. Panels show the same recruit at (a) week 1, (b) week 5, (c) week 11, (d) week 15, (e) week 19, and (f) week 23. Across the experiment the recruit produced seven additional polyps, illustrating sustained polyp budding under the higher frequency feeding regime. A white solid line in the lower right of each image represents a scale bar of 5mm. Minor color differences reflect changes in the fouling community and lighting during imaging. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

4 Discussion

This study demonstrates that feeding frequency can significantly enhance the survival and growth of G. fascicularis recruits. Frequent additional feeding resulted in higher survival rates and greater polyp development, underscoring the importance of nutritional supplementation during early post-settlement stages in ex situ coral propagation efforts. Survival inferences remained when accounting for tray clustering (beta-binomial GLMM with a Tray random intercept), and tray-aware PPR models reproduced the same treatment ordering with small tray variance, supporting that the observed feeding-frequency effects are not artifacts of the shared-tank/rotated-bucket design. These findings are particularly relevant for Indian Ocean reef restoration programs, where optimizing nursery conditions can improve the resilience and readiness of outplanted corals.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that recruits in the 2 feeds/week treatment exhibited consistently higher survival across the 23-week experimental period, with the log-rank test confirming significant differences between feeding regimes (p = 5.10 × 10-14). This suggests that regular heterotrophic feeding provides physiological advantages that support recruit longevity. G. fascicularis is known for its capacity for heterotrophic uptake and mucus production, traits that may make it particularly responsive to supplemental feeding (Craggs et al., 2017; Hii et al., 2009). Importantly, these characteristics also enable the species to sustain itself under natural reef conditions without supplemental feeding, reducing the risk that dependence on artificial nutrition would compromise post-outplant performance. Compared to many other coral taxa, G. fascicularis is particularly well equipped to benefit from supplemental feeding during early development. Similar feeding-responsive patterns have been observed in other large-polyped, strongly heterotrophic genera such as Acropora spp. and Pocillopora spp., which typically show improved growth and energetic condition when provided with particulate diets (Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2003; Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès, 2009; Conlan et al., 2017). In contrast, small-polyped corals including Porites, Montipora, and Stylophora rely more heavily on autotrophy and often show limited gains under the same feeding conditions (Grottoli et al., 2006; Palardy et al., 2005). These broader patterns help contextualize our findings, highlighting that the strong response observed in G. fascicularis aligns with species that can effectively capitalize on additional food inputs during early post-settlement growth. Heterotrophy has been shown to buffer corals against environmental stress and enhance their energy budgets during early development (Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès, 2009). This is because heterotrophic feeding supplies carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and essential organic compounds required for coral biosynthesis, nutrients that photosynthesis alone cannot provide, and which can otherwise limit growth if insufficient (Osinga et al., 2011). Feeding also interacts synergistically with autotrophy by enhancing the efficiency of photosynthesis, effectively creating a light-fuel interaction that improves energy acquisition and supports tissue growth (Osinga et al., 2011). In the context of coral restoration, this dual contribution is particularly important during the transition from ex situ cultivation to reef outplanting, when corals are especially vulnerable to environmental shock. Ensuring adequate nutritional support at this stage can therefore improve survival and growth, ultimately increasing the likelihood of restoration success.

After 23 weeks, KM estimates indicated two feeds/week yielded 41% and 67% greater survival than 1 feed/week and control, respectively. These results highlight the potential for supplemental feeding to reduce early-stage mortality, a key bottleneck in coral restoration (Rodd et al., 2022). In G. fascicularis, survival during the post-settlement phase is often constrained by energy limitations, microbial interactions, and environmental fluctuations (Jones and Gilliam, 2024). Regular feeding may help overcome some of these challenges, supporting the transition from vulnerable recruits to stable juvenile colonies. Twice-weekly feeding increased mean PPR by 0.88 and 1.11 polyps per recruit over 1 feed/week and control, respectively (+60.3%, +90.2%). This metric provides a useful proxy for colony development and early skeletal accretion (Loya, 1976). As a species capable of relatively rapid polyp budding under favorable conditions, G. fascicularis appears to benefit from energy inputs that exceed ambient plankton availability in aquaria. The significant effect of feeding treatment on PPR, confirmed through GLMM analysis, supports the idea that heterotrophy contributes directly to both tissue growth and calcification in this species (Craggs et al., 2017; Hii et al., 2009).

PPR trends over time further revealed that feeding frequency influenced not only the final size but also the rate of growth throughout the experiment. Recruits in the 2 feeds/week treatment consistently outperformed other groups in growth rate, with a significant interaction between treatment and week. These differences likely reflect cumulative energetic benefits, enabling faster development and earlier attainment of ecological thresholds such as predator resistance or reproductive capacity (Ligson et al., 2022). The slowest growth was observed in the Control group, suggesting that passive nutrient acquisition alone may be insufficient for optimal growth in G. fascicularis recruits in aquaria (Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès, 2009). Additionally, feeding once per week likely did not meet the corals’ physiological demands, leading to little or no improvement compared to unfed individuals. These results point to a threshold frequency, below which feeding does not produce measurable physiological benefits. Interestingly, the initial number of recruits per plug did not significantly influence either survival or growth outcomes. This contrasts with some previous findings where high recruit density increased competition and mortality (Tsang et al., 2018; Vermeij and Sandin, 2008).

Conversely, Van Os et al. (2012) reported high survival in G. fascicularis across different feeding regimes, with growth rates showing little sensitivity to changes in feeding frequency. In contrast, our findings emphasize that feeding frequency is critical during the early post-settlement period (0–5 months), when recruits face heightened vulnerability and elevated energy demands. Under these conditions, nutritional supplementation appears to play a decisive role in supporting survival and growth. In our experiment, colony densities may have remained below thresholds that typically induce resource limitation or intraspecific competition; alternatively, the higher-frequency treatments may have alleviated any emerging density-dependent effects by providing a more consistent supply of food. Importantly, heterotrophic feeding provides essential, bioavailable nutrients that support both coral tissue development and zooxanthellae function, whereas direct inorganic enrichment (e.g., nitrogen or phosphate) can destabilize this relationship and increase bleaching susceptibility (Osinga et al., 2011; Wiedenmann et al., 2013). Moreover, as saturation thresholds vary across coral taxa (Tagliafico et al., 2018), our results highlight the species- and stage-specific nature of these dynamics. While we did not detect a saturation point within our treatments (limited to twice-weekly feeding), the clear benefits observed underscore the importance of frequent supplementation during the earliest months of development. These findings strengthen the argument that feeding frequency is a key determinant of restoration success for recruits, extending beyond the more general survival patterns described by Van Os et al. (2012).

These findings underscore the crucial role of feeding in enhancing coral survival under warming ocean conditions, highlighting its potential to accelerate coral regeneration and strengthen reef restoration outcomes. Heterotrophic feeding has been shown to improve coral resilience to thermal stress, with Borell et al. (2008), reporting reduced bleaching and sustained metabolism under heat stress when corals received supplemental nutrition. Considering the increasing frequency of bleaching and disturbance events globally (Hayashibara et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2018), strategies that enhance early survivorship and growth are essential. Incorporating structured feeding regimes into land-based nursery protocols could shorten the timeline from settlement to out-planting, thereby improving both the efficiency and scalability of restoration programs. Importantly, our results demonstrate that frequent nutritional supplementation during early post-settlement stages provides a measurable survival advantage; an insight that restoration practitioners can directly apply to optimize nursery outputs. Future work should assess the persistence of these benefits following out-planting, examine responses across both broadcast-spawning and brooding coral taxa, and track recruits through to maturity to determine whether early-stage feeding confers lasting advantages to reef restoration success.

Statements

Data availability statement

All data and analysis scripts are archived on Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30172762 (accessed 19 October 2025) (Cooper et al., 2025). Files are provided under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Soneva Conservation and Sustainability Maldives (NGO #141-NGO/CERT/2023/36), operating under research permits issued by the Ministry of Environment, Climate Change and Energy, Republic of Maldives (Permit #203-ECA/PRIV/2024/648). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HK: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by Soneva Conservation and Sustainability Maldives under its marine and restoration initiative. The funding supported experimental setup, field operations, data collection at Soneva Fushi, Baa Atoll, Maldives, and publication fees. The funder was not involved in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the team at Soneva Conservation and Sustainability Maldives (Soneva CSM) for providing facilities, funding, and logistical support that made this research possible. We are especially grateful to Morgane Dierkens, Solène Jonveaux, and Márcia Naré for their invaluable assistance with experimental setup, daily husbandry, and data collection. Additional thanks are extended to the broader Soneva Fushi team for their technical support and commitment to advancing marine conservation and coral restoration research in the Maldives.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1728004/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Akaike H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automatic Control19, 716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

2

Anthony K. R. N. Fabricius K. E. (2000). Shifting roles of heterotrophy and autotrophy in coral energetics under varying turbidity. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.252, 221–253. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(00)00237-9

3

Barth P. Berenshtein I. Besson M. Roux N. Parmentier E. Banaigs B. et al . (2015). From the ocean to a reef habitat: how do the larvae of coral reef fishes find their way home? A state of art on the latest advances. Vie milieu65, 91–100.

4

Bartlett M. S. (1937). Properties of sufficiency and statistical tests. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci.160, 268–282.

5

Baums I. B. (2008). A restoration genetics guide for coral reef conservation. Mol. Ecol.17, 2796–2811. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03787.x

6

Borell E. M. Yuliantri A. R. Bischof K. Richter C. (2008). The effect of heterotrophy on photosynthesis and tissue composition of two scleractinian corals under elevated temperature. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.364, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.033

7

Boström-Einarsson L. Babcock R. C. Bayraktarov E. Ceccarelli D. Cook N. Ferse S. C. et al . (2020). Coral restoration–A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions. PloS One15, e0226631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226631

8

Cheal A. J. Macneil M. A. Emslie M. J. Sweatman H. (2017). The threat to coral reefs from more intense cyclones under climate change. Global Change Biol.23, 1511–1524. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13593

9

Conlan J. A. Humphrey C. A. Severati A. Francis D. S. (2017). Influence of different feeding regimes on the survival, growth, and biochemical composition of Acropora coral recruits. PLoS One12, e0188568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188568

10

Cooper J. Kyprianou H. Leonhardt J. (2025). Data and R scripts for: Effects of feeding frequency on survival and growth of Galaxea fascicularis recruits in ex situ nurseries. Figshare. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30172762

11

Craggs J. Guest J. Bulling M. Sweet M. (2019). Ex situ co culturing of the sea urchin, Mespilia globulus and the coral Acropora millepora enhances early post-settlement survivorship. Sci. Rep.9, 12984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49447-9

12

Craggs J. Guest J. R. Davis M. Simmons J. Dashti E. Sweet M. (2017). Inducing broadcast coral spawning ex situ: Closed system mesocosm design and husbandry protocol. Ecol. Evol.7, 11066–11078. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3538

13

Craggs J. Guest J. Davis M. Sweet M. (2020). Completing the life cycle of a broadcast spawning coral in a closed mesocosm. Invertebrate Reprod. Dev.64, 244–247. doi: 10.1080/07924259.2020.1759704

14

D’Angelo C. Wiedenmann J. (2012). An experimental mesocosm for long-term studies of reef corals. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom92, 769–775. doi: 10.1017/S0025315411001883

15

Ding D.-S. Sun W.-T. Pan C.-H. (2021). Feeding of a scleractinian coral, goniopora columna, on microalgae, yeast, and artificial feed in captivity. Animals11, 3009. doi: 10.3390/ani11113009

16

Dunn O. J. (1964). Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics6, 241–252. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1964.10490181

17

Edmunds P. J. Carpenter R. C. (2001). Recovery of Diadema antillarum reduces macroalgal cover and increases abundance of juvenile corals on a Caribbean reef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.98, 5067–5071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071524598

18

Edmunds P. J. Riegl B. (2020). Urgent need for coral demography in a world where corals are disappearing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.635, 233–242. doi: 10.3354/meps13205

19

Ferrier-Pagès C. Witting J. Tambutté E. Sebens K. P. (2003). Effect of natural zooplankton feeding on the tissue and skeletal growth of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Coral Reefs22, 229–240. doi: 10.1007/s00338-003-0312-7

20

Forsman Z. H. Kimokeo B. K. Bird C. E. Hunter C. L. Toonen R. J. (2012). Coral farming: effects of light, water motion and artificial foods. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom92, 721–729. doi: 10.1017/S0025315411001500

21

Gomez-Lemos L. A. Diaz-Pulido G. (2017). Crustose coralline algae and associated microbial biofilms deter seaweed settlement on coral reefs. Coral Reefs36, 453–462. doi: 10.1007/s00338-017-1549-x

22

Grasso L. C. Negri A. P. Fôret S. Saint R. Hayward D. C. Miller D. J. et al . (2011). The biology of coral metamorphosis: Molecular responses of larvae to inducers of settlement and metamorphosis. Dev. Biol.353, 411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.010

23

Grottoli A. G. Rodrigues L. J. Palardy J. E. (2006). Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature440, 1186–1189. doi: 10.1038/nature04565

24

Guest J. R. Baria M. V. Gomez E. D. Heyward A. J. Edwards A. J. (2014). Closing the circle: is it feasible to rehabilitate reefs with sexually propagated corals? Coral Reefs33, 45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1114-1

25

Hayashibara T. Iwao K. Omori M. (2004). Induction and control of spawning in Okinawan staghorn corals. Coral Reefs23, 406–409. doi: 10.1007/s00338-004-0406-x

26

Hii Y.-S. Soo C.-L. Liew H.-C. (2009). Feeding of scleractinian coral, Galaxea fascicularis, on Artemia salina nauplii in captivity. Aquac Int.17, 363–376. doi: 10.1007/s10499-008-9208-4

27

Houlbrèque F. Ferrier-Pagès C. (2009). Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev.84, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00058.x

28

Hughes T. P. Kerry J. T. Baird A. H. Connolly S. R. Dietzel A. Eakin C. M. et al . (2018). Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature556, 492–496. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0041-2

29

Jones N. Gilliam D. (2024). Spatial differences in recruit density, survival, and size structure prevent population growth of stony coral assemblages in southeast Florida. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1369286

30

Kaplan E. L. Meier P. (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.53, 457–481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452

31

Kruskal W. H. Wallis W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.47, 583–621. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441

32

Lachs L. Oñate-Casado J. (2020). “ Fisheries and tourism: social, economic, and ecological trade-offs in coral reef systems,” in YOUMARES 9 - the oceans: our research, our future: proceedings of the 2018 conference for YOUng MArine RESearcher in oldenburg, Germany. Eds. JungblutS.LiebichV.Bode-DalbyM. ( Springer International Publishing, Cham).

33

Lecchini D. Miura T. Lecellier G. Banaigs B. Nakamura Y. (2014). Transmission distance of chemical cues from coral habitats: implications for marine larval settlement in context of reef degradation. Mar. Biol.161, 1677–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2451-5

34

Levene H. (1960). Robust tests for equality of variances. In OlkinI. (Ed.), Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling.Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 278–292.

35

Li Z. (2019). Symbiotic microbiomes of coral reefs sponges and corals (Cham, Switzerland: Springer).

36

Ligson C. Cabaitan P. Harrison P. (2022). Survival and growth of coral recruits in varying group sizes. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.556, 151793. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2022.151793

37

López-Torres M. A. Lizárraga-Partida M. L. (2001). Bacteria isolated on TCBS media associated with hatched Artemia cysts of commercial brands. Aquaculture194, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00505-6

38

Loya Y. (1976). “ Settlement, mortality and recruitment of a red sea scleractinian coral population,” in Coelenterate ecology and behavior. Ed. MackieG. O. ( Springer US, Boston, MA).

39

Mantel N. (1966). Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother. Rep.50, 163–170.

40

Mass S. Cohen H. Podicheti R. Rusch D. B. Gerlic M. Ushijima B. et al . (2024). The coral pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus uses a T6SS to secrete a group of novel anti-eukaryotic effectors that contribute to virulence. PLoS Biol.22, e3002734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002734

41

Mcmanus J. W. Polsenberg J. F. (2004). Coral–algal phase shifts on coral reefs: Ecological and environmental aspects. Prog. Oceanogr60, 263–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2004.02.014

42

Mehvar S. Filatova T. Dastgheib A. De Ruyter Van Steveninck E. Ranasinghe R. (2018). Quantifying economic value of coastal ecosystem services: a review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.6, 5. doi: 10.3390/jmse6010005

43

Moberg F. Folke C. (1999). Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ29, 215–233. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00009-9

44

Morse D. E. Hooker N. Morse A. N. C. Jensen R. A. (1988). Control of larval metamorphosis and recruitment in sympatric agariciid corals. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.116, 193–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(88)90027-5

45

Norström A. V. Nyström M. Lokrantz J. Folke C. (2009). Alternative states on coral reefs: beyond coral&x2013;macroalgal phase shifts. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.376, 295–306.

46

Osinga R. Schutter M. Griffioen B. Wijffels R. H. Verreth J. A. Shafir S. et al . (2011). The biology and economics of coral growth. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY)13, 658–671. doi: 10.1007/s10126-011-9382-7

47

Palardy J. E. Grottoli A. G. Matthews K. A. (2005). Effects of upwelling, depth, morphology and polyp size on feeding in three species of Panamanian corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.300, 79–89. doi: 10.3354/meps300079

48

Petersen D. Wietheger A. Laterveer M. (2008). Influence of different food sources on the initial development of sexual recruits of reefbuilding corals in aquaculture. Aquaculture277, 174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.02.034

49

Puntin G. Craggs J. Hayden R. Engelhardt K. E. Mcilroy S. Sweet M. et al . (2023). The reef-building coral Galaxea fascicularis: a new model system for coral symbiosis research. Coral Reefs42, 239–252. doi: 10.1007/s00338-022-02334-8

50

Randall C. J. Negri A. P. Quigley K. M. Foster T. Ricardo G. F. Webster N. S. et al . (2020). Sexual production of corals for reef restoration in the Anthropocene. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.635, 203–232. doi: 10.3354/meps13206

51

R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

52

Riegl B. Bruckner A. Coles S. L. Renaud P. Dodge R. E. (2009). Coral reefs: threats and conservation in an era of global change. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci.1162, 136–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04493.x

53

Rodd C. Whalan S. Humphrey C. Harrison P. L. (2022). Enhancing coral settlement through a novel larval feeding protocol. Front. Mar. Sci.9, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.918232

54

Roik A. Roder C. Röthig T. Voolstra C. R. (2016). Spatial and seasonal reef calcification in corals and calcareous crusts in the central Red Sea. Coral Reefs35, 681–693. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1383-y

55

Sahandi J. Sorgeloos P. Tang K. W. Jafaryan H. Yang W. Mai K. et al . (2025). Highlighting antibiotic-free aquaculture by using marine microbes as a sustainable method to suppress Vibrio and enhance the performance of brine shrimp (Artemia franciscana). Arch. Microbiol.207, 26. doi: 10.1007/s00203-024-04234-7

56

Schneider C. A. Rasband W. S. Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089

57

Soneva C. (2022-2025). Kunfunadhoo island spawning database ( Soneva Conservation & Sustainability Maldives).

58

Spearman C. (1904). The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol.15, 72–101. doi: 10.2307/1412159

59

Tagliafico A. Rangel S. Kelaher B. Christidis L. (2018). Optimizing heterotrophic feeding rates of three commercially important scleractinian corals. Aquaculture483, 96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.10.013

60

Tsang R. H. L. Chui A. P. Y. Wong K. T. Ang P. (2018). Corallivory plays a limited role in the mortality of new coral recruits in Hong Kong marginal coral communities. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.503, 100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2018.03.003

61

Van Oppen M. J. H. Oliver J. K. Putnam H. M. Gates R. D. (2015). Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.112, 2307–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422301112

62

Van Os N. Massé L. M. Séré M. G. Sara J. R. Schoeman D. S. Smit A. J. (2012). Influence of heterotrophic feeding on the survival and tissue growth rates of Galaxea fascicularis (Octocorralia: Occulinidae) in aquaria. Aquaculture330, 156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.12.006

63

Vermeij M. J. A. Sandin S. A. (2008). Density-dependent settlement and mortality structure the earliest life phases of a coral population. Ecology89, 1994–2004. doi: 10.1890/07-1296.1

64

Wallace C. Harrison P. L. Wallace C. C. (1990). “ A review of reproduction, larval dispersal and settlement of scleractinian corals,” in Chapter 7 in ecosystems of the world 25 coral reefs. Ed. DubinskyZ. ( Elsevier, Amsterdam), 133–196.

65

Wiedenmann J. D’Angelo C. Smith E. Hunt A. Legiret F.-E. Postle A. et al . (2013). Nutrient enrichment can increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat. Clim. Change3, 160–164. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1661

Summary

Keywords

coral restoration, Galaxea fascicularis , coral recruits, heterotrophic feeding, feeding frequency, ex situ coral nurseries

Citation

Cooper J, Kyprianou H and Leonhardt J (2026) Improving ex situ coral culture outcomes: growth and survival responses of Galaxea fascicularis recruits to supplemental feeding. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1728004. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1728004

Received

19 October 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

04 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Baruch Rinkevich, Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research, Israel

Reviewed by

Margaret W. Wilson, University of California, Santa Barbara, United States

Fen Wei, Guangxi University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Cooper, Kyprianou and Leonhardt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jarrod Cooper, jarrodmcooper98@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.