Abstract

Introduction:

Underwater organism detection is critical for intelligent aquaculture and marine ecological monitoring, but real-time deployment on resource-constrained platforms remains challenging due to the high computational cost of existing detectors.

Methods:

To address this, we propose UOD-YOLO, a lightweight real-time detection framework derived from YOLOv11n. The model integrates three key components: (1) a RepViT-based lightweight backbone for efficient feature representation; (2) a scale-sequence feature fusion (SSFF) module and a triple feature encoding (TFE) module to enhance multi-scale information extraction and fine-grained feature representation; and (3) a lightweight detection head combined with a channel–position attention mechanism (CPAM) to strengthen small-object recognition. We evaluate the model on three underwater benchmarks: RUOD, UTDAC2020, and DUO.

Results:

Compared with YOLOv11n, UOD-YOLO improves mAP50 and mAP50–95 by 3.5% and 6.9%, respectively, while reducing the number of parameters and floating-point operations by 36.3% and 19.7%. The model achieves a real-time detection speed of 279.8 frames per second. Visualization experiments further confirm its robustness under varying illumination and depth conditions.

Discussion:

The compact size and strong accuracy of UOD-YOLO make it suitable for deployment on embedded and edge devices in aquaculture monitoring, continuous underwater surveillance, and multi-sensor fusion systems. This work provides an efficient and reliable solution for real-time underwater organism detection in complex marine environments.

1 Introduction

In recent years, lightweight optimization has become a central topic not only in object detection but also in resource-constrained robotic and IoT sensing systems. Underwater perception devices—such as AUVs, ROVs, and low-power edge platforms—often operate under strict computational and energy budgets, making conventional large-scale detectors impractical for real-time deployment. Therefore, underwater object detection requires a joint consideration of accuracy, model compactness, and efficiency. Existing underwater detectors have focused primarily on improving feature extraction or illumination robustness, but relatively few works systematically address lightweight architectural design for embedded systems. This gap motivates the development of our proposed UOD-YOLO framework. Underwater object detection (UOD) is among the most challenging and complex areas of contemporary computer vision research. Traditional marine operations rely heavily on manual labor, which is both costly and inefficient, and therefore presents a significant challenge in meeting the growing demand for applications (Bai et al., 2022; Chuang et al., 2016). Inspired by the successful application of object detection technology in other industries, UOD is now widely used in a variety of marine applications, including aquaculture, offshore fishing (Yang L. et al., 2021), marine wildlife monitoring, and underwater archaeology (Chen G. et al., 2023). The advances in computing power in graphics hardware have opened up a new avenue for exploring the ocean through the use of computer vision techniques. Human operators can utilize underwater exploration equipment such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) (Ngatini et al., 2017; Elhaki et al., 2022) to develop marine ecological resources in a non-invasive manner.

The resurgence of neural networks is occurring concurrently with the growth in processing power of graphics hardware, which is being driven by the development of deep learning-based object detection methods. These methods are derived from artificial neural networks (Yang J. et al., 2021) and fall broadly into two principal categories: two-stage and single-stage detectors. Both categories have been applied in UOD. The detection model has been enhanced with the integration of diverse feature extraction (Hua et al., 2023), fusion strategies (Xu X. et al., 2023), and loss definitions.

Single-stage algorithms perform simultaneous object detection and classification, thereby directly acquiring the return position and category of the objects in question. This approach is a primary characteristic of single-stage algorithms. The most commonly used algorithms include a single-shot detector (SSD) (Liu et al., 2016) and the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series. The YOLO algorithm has undergone several iterations, including YOLO (Redmon et al., 2016), YOLOv2 (Redmon and Farhadi, 2017), and YOLOv3 (Redmon and Farhadi, 2018), each improving in accuracy and becoming more powerful. Additionally, YOLOX (Ge et al., 2021), which was proposed in 2021, was the first version to enable anchor-less object detection. Unlike the previous YOLO algorithms, this is an unanchored model, which has demonstrated a relatively impressive performance in various metrics on the public dataset. Single-stage detectors are generally faster than two-stage approaches, because they bypass the candidate region proposal step. In contrast, two-stage detectors divide the object detection task into two stages. Initially, suggested candidate object regions are generated from the input image, and subsequently, all candidate regions are conveyed to a classifier for classification. Representative algorithms include Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2017), Mask R-CNN (He et al., 2020), and Cascade R-CNN (Cai and Vasconcelos, 2017). The significant improvements in accuracy achieved by YOLOv8 have enabled it to be employed for the detection of underwater environments (Guo et al., 2024) and other applications (Talaat and ZainEldin, 2023). However, increased accuracy often accompanies increased model size; for example, YOLOv8s is 56% larger than YOLOv5s. Therefore, a balance must be struck between network complexity, size, and detection speed.

Ideal underwater object detectors should possess three essential characteristics: high accuracy, high efficiency, and strong adaptability to complex underwater environments (Xu S. et al., 2023). However, there are several complex challenges associated with UOD. These include the lack of sufficient underwater image datasets (Yang et al., 2023) and the inherent complexity of underwater environments (Li J. et al., 2023), which impose significant demands on the capabilities of underwater imaging devices. The acquisition of underwater images is a more challenging process than that of acquiring atmospheric optical images. Consequently, it is challenging for data-driven deep learning models to attain optimal outcomes. The quality of images captured underwater is often inadequate. The quality of underwater images in terms of color and texture information is inferior to that of atmospheric optical images due to the presence of factors such as uneven lighting, blurring, fogging, low contrast and color deviation (Schettini and Corchs, 2010). The detection of small and clustered objects, which are common in underwater scenes, represents a significant challenge in UOD. Some underwater organisms are characterized by a concentration of small objects, which makes it difficult to extract fine details.

Recent advances in underwater enhancement and structural modeling have direct relevance to robust UOD: diffusion-based visual–textual enhancement improves image quality for downstream detectors (Wang et al., 2026), chromatic-consistency priors help restore natural underwater colors (Wang H. et al., 2024), spectrum-to-graph representations enable robust recognition under low-quality sensing (Li et al., 2025a), and reinforcement-learning-driven joint detection–tracking shows promise for compact real-time monitoring systems (Li et al., 2025b). Some studies have also explored enhanced feature extraction and restoration strategies for underwater perception. For example, the DM-AECB framework integrates diffusion-based restoration with attention-augmented convolutional blocks to improve underwater image clarity and robustness (Tiwari et al., 2025). Similarly, a multi-stage adaptive feature fusion strategy has been proposed to enhance underwater images through progressive refinement and feature aggregation (Akram et al., 2024). These approaches focus primarily on image enhancement, whereas our method targets lightweight end-to-end detection with improved multi-scale fusion and efficient attention design.

The imbalances in the number of specific underwater objects present another obstacle. When the number of samples for a particular class of objects is insufficient, it becomes difficult for an underwater object detector to learn the features of that class. This negatively affects the detector’s performance. These problems collectively pose a substantial challenge to UOD. Additionally, embedded underwater devices typically have limited storage and computational resources, which render large detection networks ineffective in underwater environments. Despite these constraints, there is a paucity of research in the field of lightweight UOD. Therefore, it is essential to develop a lightweight detector with high detection accuracy and a small model size for the purpose of UOD (Wang et al., 2024).

Most underwater detection techniques initially enhance the underwater image data before employing classical rule-box object detection methods (Wang et al., 2023) to identify the underwater objects. Although this preprocessing improves image quality, it is time-consuming and the resulting accuracy may not necessarily be superior to other techniques. Therefore, we proposed a novel UOD framework, based on an enhanced version of YOLOv11 (Jocher et al., 2023), designated as UOD-YOLO. The complete network architecture comprises a YOLOv11 backbone that was partially replaced by an enhanced standard lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) (Wang et al., 2024), an attention scale fusion (ASF)-based (Kang et al., 2024) scale sequence feature fusion (SSFF) module, a triple feature encoding (TFE) module, and the channel and position attention mechanism (CPAM). The standard lightweight CNN was progressively enhanced and substituted within the backbone network of YOLOv11, with reference to the efficient architectural design of the lightweight vision transformer ViT) (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021). This enhanced the performance and efficiency of the detection framework on mobile devices. Subsequently, the original neck of YOLOv11 was reconstructed using the SSFF module. The incorporation of SSFF facilitated the gradual fusion of low-level to high-level features in the backbone network, which enhanced the network in terms of multi-scale information extraction. The TFE module is capable of fusing feature maps at varying scales, thereby enhancing the extraction of detailed information. Furthermore, the CPAM integrated the SSFF and TFE modules, enabling a focus on information channels and small objects associated with spatial locations, thereby enhancing the detection and segmentation performance. The results of our experiments using publicly available UOD datasets, including RUOD (Fu et al., 2023), UTDAC 2020 (Flyai, 2020), and DUO (Liu et al., 2021), demonstrated that our proposed enhanced YOLOv11-based detection approach performed better than other lightweight detection methods, with notable improvements in both detection accuracy and efficiency.

The main contributions of this study were as follows:

-

A lightweight UOD framework based on the YOLOv11 algorithm was proposed. This was achieved by reducing the processing power requirements of the system by streamlining the backbone network and reconstructing the neck of YOLOv11 using an ASF-based feature fusion network. The integration of ASF into the YOLO framework enhanced the detection and segmentation performance of the image.

-

The utilization of the CPAM, which integrated the SSFF and TFE modules, enhanced the detection and segmentation of minute, detail-rich objects in an underwater context. The CPAM provided an efficacious attentional guidance to the model by focusing on the information-rich channels in addition to the spatially location-dependent features of the aforementioned small objects. This mechanism enabled the model to more accurately identify and localize small objects in the image, thereby enhancing the detection and segmentation tasks.

-

To determine the efficacy of different model architectures and parameter sizes for the detection of underwater objects, a series of experiments were conducted using the publicly accessible RUOD, UTDAC2020, and DUO datasets. A comparison with the detection method based on the improved YOLOv11 demonstrated that our proposed approach achieved greater accuracy and a more compact size.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work. Section 3 describes the model employed in the experiment, and outlines the experimental setup and the construction of the dataset. Section 4 presents the experimental and visual results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and suggests potential directions for future research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Underwater object detection

Although object detection has been successfully applied to general category datasets, it remains a challenging task in the context of UOD. In underwater scenes, lighting conditions have a significant impact on the quality of underwater images, resulting in reduced visibility, low contrast, and color distortion. Furthermore, the complexity of underwater environments and the typically small size of underwater objects contribute to the difficulty of UOD.

In recent years, numerous researchers have made significant contributions to the field of UOD, resulting in notable advances. For underwater organism detection,

Existing underwater detection methods can be broadly grouped into three categories: (1) enhancement-driven detection frameworks, (2) small-object-oriented detection networks, and (3) two-stage detectors adapted for underwater imagery.

Enhancement-driven approaches (e.g., Yu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023) improve visibility or contrast before detection but often incur high latency and limited robustness under severe turbidity. Small-object-oriented methods (e.g., Gao et al., 2024; Li P. et al., 2023) enhance multi-scale features or integrate attention modules to resolve dense micro-targets, yet they generally rely on heavy backbones that hinder embedded deployment. Two-stage detectors (Zeng et al., 2021; Song et al., 2023) offer strong accuracy but are computationally burdensome for real-time tasks.

Overall, prior works focus primarily on accuracy improvement while overlooking lightweight design—a critical requirement for edge-based underwater platforms.

However, most of these approaches remain constrained by relatively large backbone complexity or limited generalization ability across varying underwater environments. Although lightweight detection has achieved notable success in mobile vision tasks, its application in underwater domains remains limited. The primary challenge lies in balancing three factors: small-object sensitivity, multi-scale feature representation, and low-computational cost suitable for IoT-grade processors.

To address this gap, our method follows the design principles of efficient hybrid CNN-ViT architectures and lightweight multi-scale fusion, similar in spirit to ASF-YOLO and recent CNN–ViT hybrids. By integrating RepViT, SSFF, TFE, and CPAM, the proposed framework simultaneously enhances multi-scale reasoning and reduces computational overhead, making it suitable for embedded underwater sensing systems. This positioning distinguishes our work from existing methods that prioritize accuracy over deployability.

2.2 Lightweight networks

In recent years, the continuous advancement of deep learning has led to significant improvements in object detection models, which are now widely employed across various fields. However, deploying these neural network models on mobile and embedded devices remains a significant challenge, largely due to the constraints imposed by the limited storage space and computational power. The development of lightweight networks, which aim to reduce the number of model parameters and computational complexity while maintaining accuracy, has become a prominent area of research in the field of computer vision.

The most prevalent lightweight network models in the mainstream are MobileNet (Howard et al., 2017; Sandler et al., 2018; Howard et al., 2019), ShuffleNet (Zhang et al., 2018), and others. These models achieve high efficiency through the use of diverse convolutional methods and structures. Depthwise separable convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) (Chollet, 2017) have demonstrated considerable potential in the field of deep learning, achieving high levels of classification accuracy across various computer vision tasks. The concept of knowledge distillation, as proposed by Hinton et al. (2015), offers a novel approach to address the limitations of slow inference in integrated models and the substantial demands placed on deployment resources. The new partial convolutions presented by Chen J. et al. (2023) offer an enhanced method of extracting spatial features through the concurrent minimization of superfluous computations and memory access.

With the rapid advancement of deep learning in recent years, there has been a surge of interest in leveraging lightweight networks for UOD research. The majority of these studies employed the enhanced YOLO object detection methodology (Guo et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2021; Chen X. et al., 2023), while a smaller number use the lightweight transformer approach (Cui et al., 2023). Table 1 presents an overview of the existing lightweight network models, including their names, primary algorithmic approaches, parameter sizes, and Top-1 accuracy after 300 epochs of training on the ImageNet-1K dataset.

Table 1

| Model | Type | Param(M) | Top-1 Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| MobilenetV4-Conv-M | CONV | 9.2 | 79.9 |

| MobilenetV4-Hybrid-M | Hybrid | 10.5 | 80.7 |

| ShuffleNet(x2) | CONV | 5.4 | 73.7 |

| SwiftFormer-S | Hybrid | 6.1 | 78.5 |

| EfficientFormerV2-S2 | Hybrid | 12.6 | 81.6 |

| YOLO11s-cls | CONV | 5.5 | 75.4 |

| RepViT | CONV | 5.1 | 78.7 |

The classification performance of different models on ImageNet-1K.

As shown in Table 1, The RepViT model demonstrated a satisfactory Top- 1 accuracy with the ImageNet-1K dataset while maintaining a relatively low number of parameters compared to other lightweight models of varying scales.

3 Materials and methods

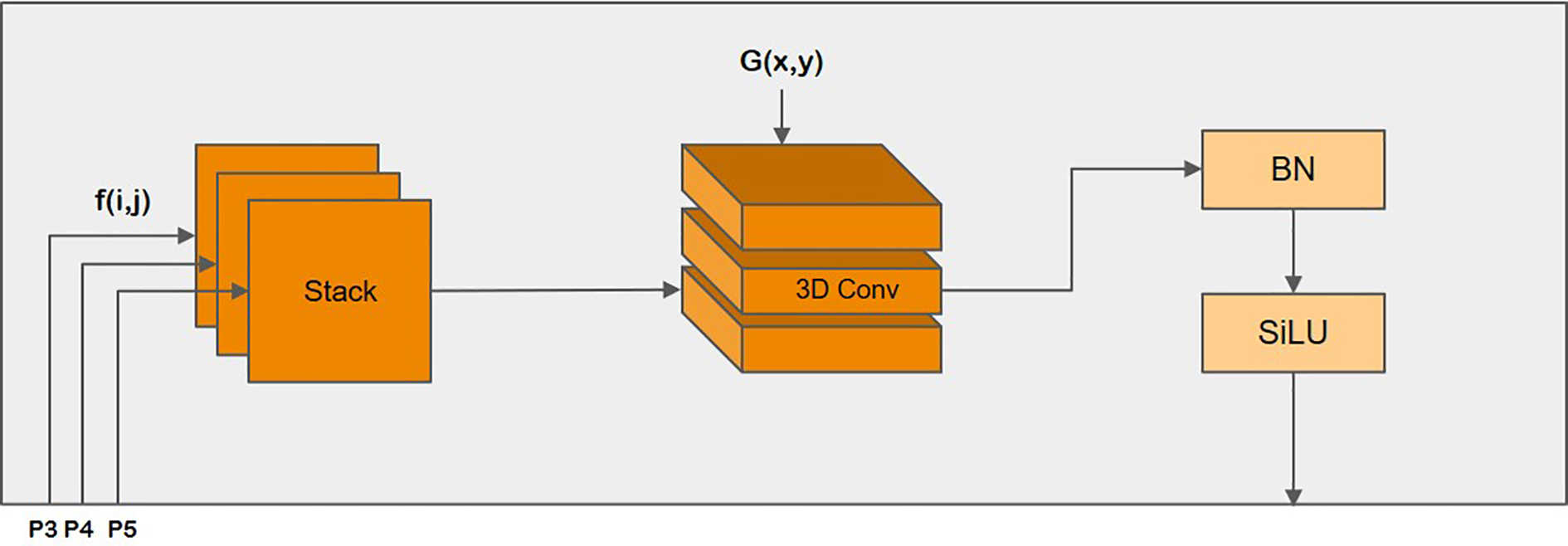

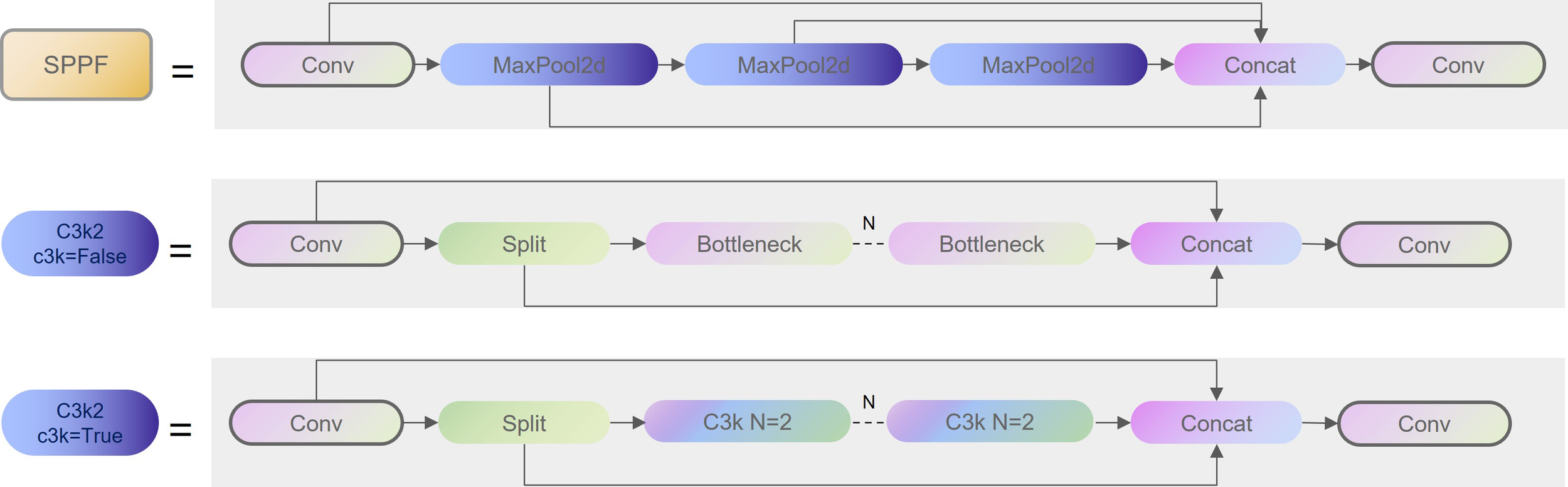

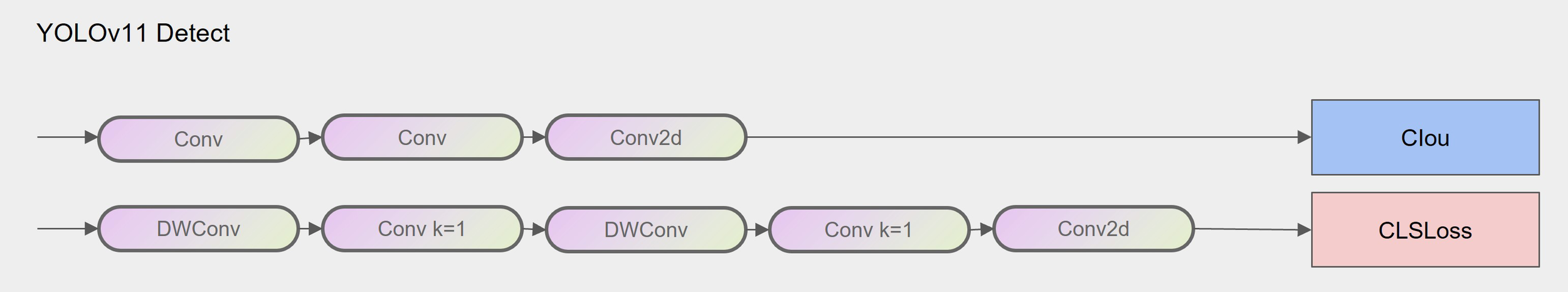

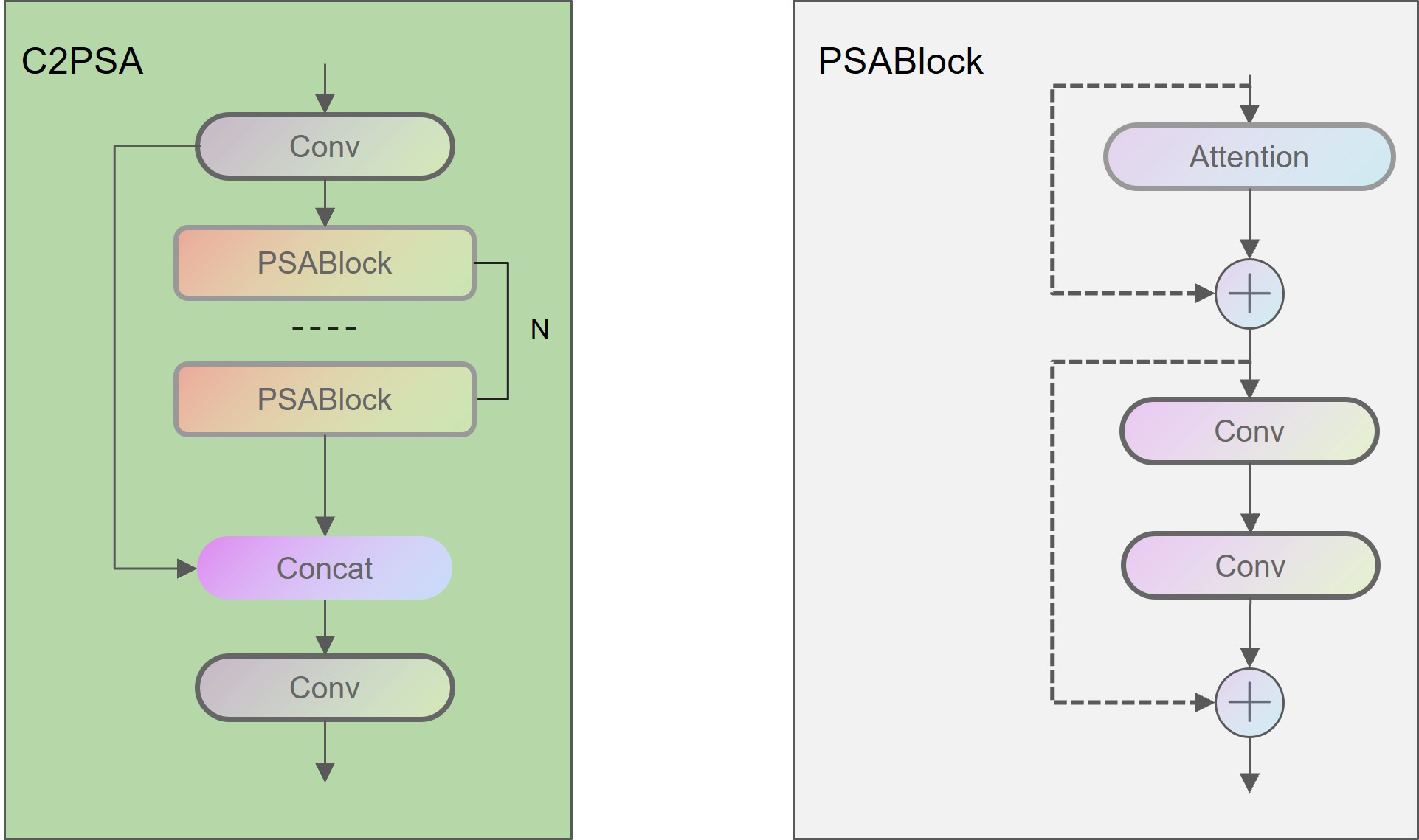

The YOLOv11 architecture retains the same underlying structure as YOLOv8, consisting of the same backbone, neck, and head components. As shown in Figure 1, the main difference lies in the modification of the original C2f module to the C3k2 module, where C3k2 incorporates the parameter C3k. In the superficial layer of the network, C3k is set to False. Consequently, the C3k2, in its present form, is analogous to C2f in YOLOv8, exhibiting a uniform network configuration. The second proposed alteration is the C2PSA mechanism, which is a C2 mechanism that has been embedded with a multi-head attention mechanism, as shown in Figure 2. The final modification is the incorporation of two depth wise convolutional layers (DWConv) into the classification detection header, which was previously decoupled. This modification substantially reduces both the number of parameters and computational requirements (see Figure 3 for further details).

Figure 1

Detailed structure of SPPF and C3k2.

Figure 2

Network structure of C2PSA and PSABlock.

Figure 3

Detectors of Yolov 11.

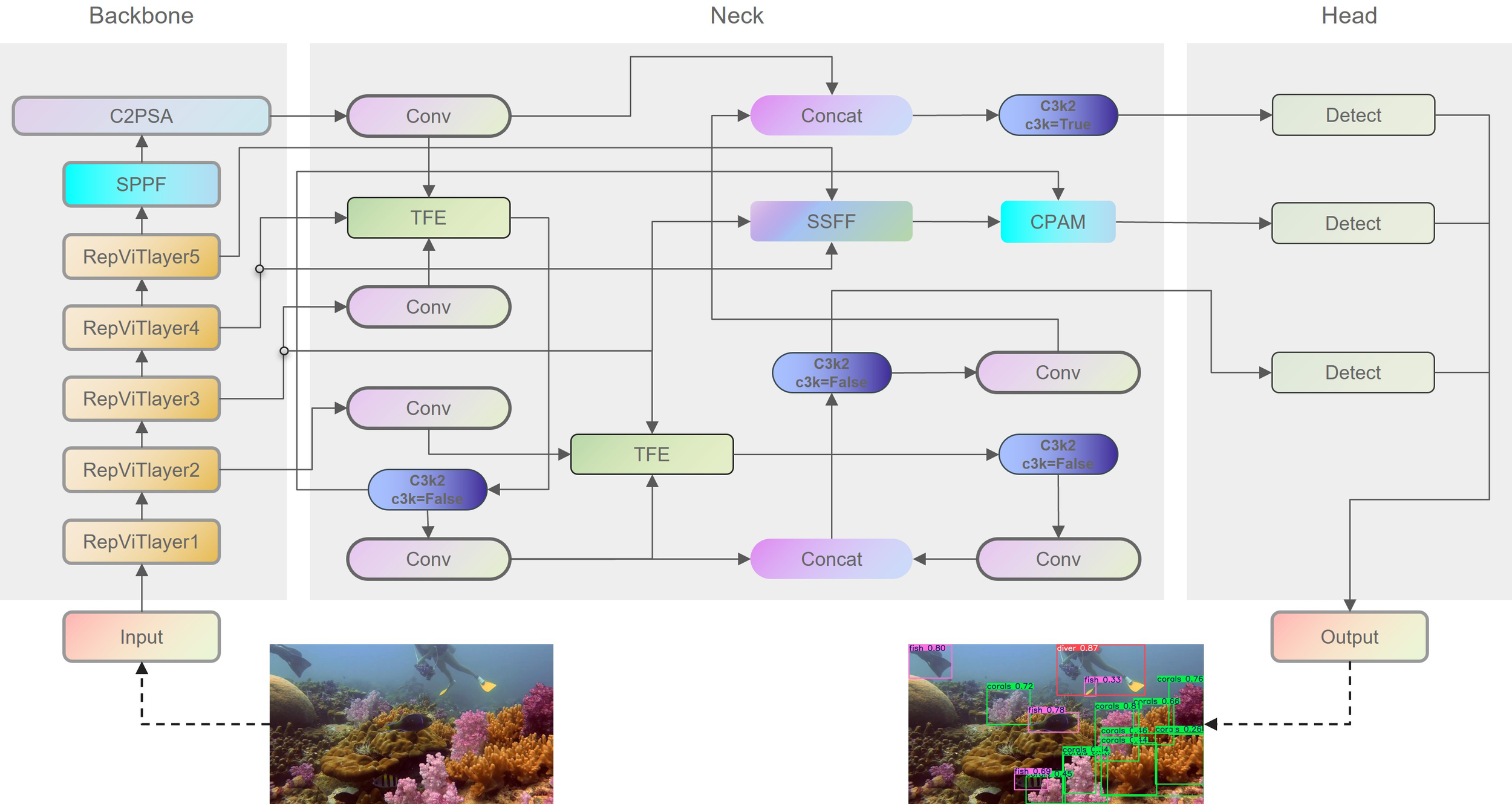

To address the issue of lightweight UOD, the YOLOv11n network was employed as a baseline for the purpose of achieving both high accuracy and a compact model size. Three principal modifications were made to the YOLOv11n. Initially, instead of using the original backbone of YOLOv11n, the proposed UOD-YOLO employed the efficient lightweight model RepViT (Wang et al., 2024) as the backbone, thereby reducing the model size. Second, the SSFF module, which enhances a network’s capacity to extract multi-scale information, was employed in the neck section of the model. Additionally, the TFE module, which fuses feature maps at different scales, was utilized to augment the network’s ability to process multi-scale information. Furthermore, the CPAM was introduced to integrate the SSFF and TFE modules, and provide detailed information. The overall architecture of the UOD-YOLO network is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

The overall architectural design of the UOD-YOLO network.

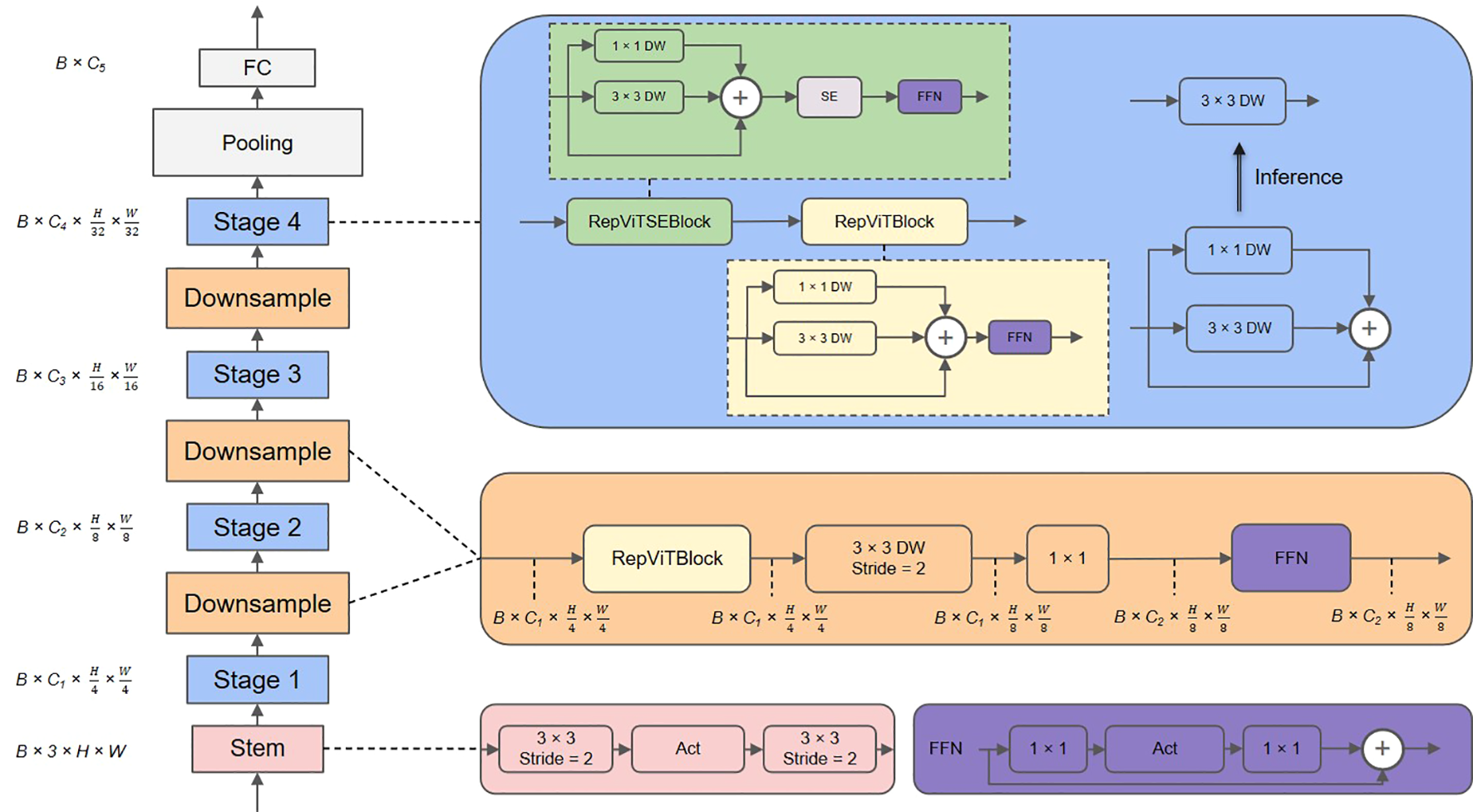

3.1 The RepViT backbone

The RepViT approach builds upon the existing light-weight CNNs by integrating the efficient architectural design of lightweight ViTs, thereby enhancing their suitability for mobile applications. This integration results in a novel family of pure lightweight CNNs. Several experiments have demonstrated that RepViT outperforms existing state-of-the-art lightweight ViTs, and it also exhibits favorable latency across a diverse range of visual tasks. Consequently, we elected to use RepViT as the backbone of our network. The configuration of RepViT is displayed in Figure 5. RepViT consists of four distinct stages, each processing input feature maps at progressively reduced spatial resolutions of × , × , × , and × , respectively.

Figure 5

An overview of the RepViT architecture.

Stem is the module that is responsible for preprocessing the input image, with each stage comprising multiple RepViTBlocks. An optional RepViTSEBlock was also employed, which contained a depth-separable convolution (3 × 3 DW), 1 × 1 convolution, a squeeze-excitation module (SE), and a feedforward network (FFN). The primary function of each stage was to reduce the spatial dimension by downsampling. Following these stages, a global average pooling layer was employed to reduce the spatial dimensionality of the feature map. Finally, a fully connected layer was employed to make a final category prediction.

3.2 Scale sequence feature fusion

To address the multi-scale nature of images, feature pyramid structures are commonly employed for feature fusion in the extant literature. However, previous studies have primarily relied on a simple summation or concatenation for this purpose. These conventional feature pyramid network (FPN) architectures do not efficiently exploit the correlations among all pyramid feature maps. The SSFF module allows for a better combination of multi-scale feature maps by integrating high-level information from deep feature maps with detailed spatial information from shallow feature maps that share the same aspect ratio. Sequential representations of multi-scale feature maps are generated by the backbones (i.e. P3, P4, and P5), which capture image content at different levels of detail. These feature maps are then constructed. The feature maps P3, P4, and P5 are convolved by a series of Gaussian kernels with increasing standard deviation (Tran et al., 2015). The processing is shown mathematically in Equation 1.

where f represents a two-dimensional (2D) feature map and Fσ is generated by a series of convolutional smoothing operations using a 2D Gaussian filter with increasing standard deviation. The feature maps of varying scales were then arranged in a horizontal stack, and the scale sequence features were extracted through a three-dimensional (3D) convolution process inspired by 2D and 3D convolution operations on multiple video frames. Given that the output feature maps of the Gaussian smoothing process had different resolutions, all feature maps were aligned to the same resolution as P3 by means of a nearest neighbor interpolation. This was because the high-resolution feature map level P3 contained most of the information critical for detection and small target segmentation, and the SSFF module was designed based on the P3 level. As shown in Figure 6, the proposed SSFF module encompassed the following components:

Figure 6

Scale sequence feature fusion (SSFF).

-

The number of channels at the P4 and P5 feature levels was varied to 256 using a 1 × 1 convolution. It was resized to the P3 level using the nearest neighbor interpolation method.

-

The dimension of each feature layer was increased using the “unsqueeze” function to change it from a 3D to 4D tensor.

-

The subsequent convolution process involved the connection of 4D feature maps along the depth dimension, resulting in the formation of 3D feature maps.

-

Finally, proportional sequence feature extraction was completed using a 3D convolution, 3D batch normalization, and the sigmoid linear unit (SiLU) activation function (Elfwing et al., 2018).

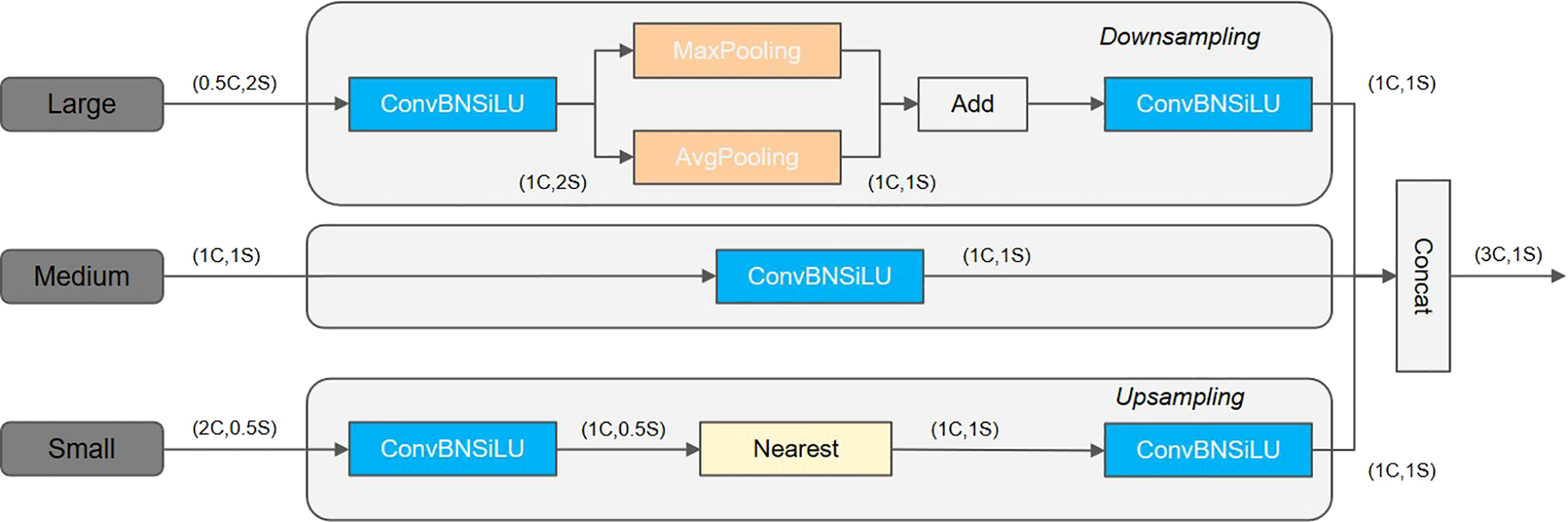

3.3 Triple feature encoding

To effectively recognize densely overlapping small targets, it is essential to reference and compare shape or appearance changes across different scales by zooming into the image. Given that the feature layers of the backbone network vary in spatial resolution, conventional FPN fusion mechanisms merely up-sample small feature maps before merging them with higher-resolution preceding layers of features. This process often neglects the rich, detailed information inherently present within the larger feature layers. To address this limitation, the TFE module has been proposed. This module categorizes features into large, medium, and small categories, and then incorporates large-size feature maps and performs feature scaling to enhance the detailed feature information.

As shown in Figure 7, the TFE module consists of several distinct components. Prior to feature encoding, the number of channels was initially adjusted to correspond with the primary scale features. The large-size feature map (Large) processed by the convolution module was used to adjust the number of channels to 1C. Then, downsampling was performed using a hybrid structure of maximum pooling plus average pooling, which reduced the spatial dimensionality of the features and implemented translation invariance to enhance the robustness of the network to spatial variations and translations in the input image. For small-sized feature maps (Small), the number of channels was also adjusted using the convolution module and then upsampled using the nearest neighbor interpolation method. This approach was intended to preserve local features and prevent the loss of small target feature information due to background interference. The latter was addressed by the nearest neighbor interpolation technique, which can populate the feature map by exploiting neighboring pixels and taking into account sub-pixel neighborhoods. However, it should be noted that the use of nearest neighbor interpolation for up-sampling can result in the loss of significant detail associated with small targets due to the impact of background interference. Finally, the feature maps of varying sizes were convolved within the same dimension, followed by splicing in the channel dimension using the following Equation 2:

Figure 7

Triple feature encoding (TFE).

where FTFE denotes the feature map output from the TFE module, and F, Fm, and FS denote the feature maps of large, medium, and small sizes, respectively. FTFE is the result of stitching Fl, Fm, and FS. FTFE has the same resolution as Fm and has three times the number of channels as Fm.

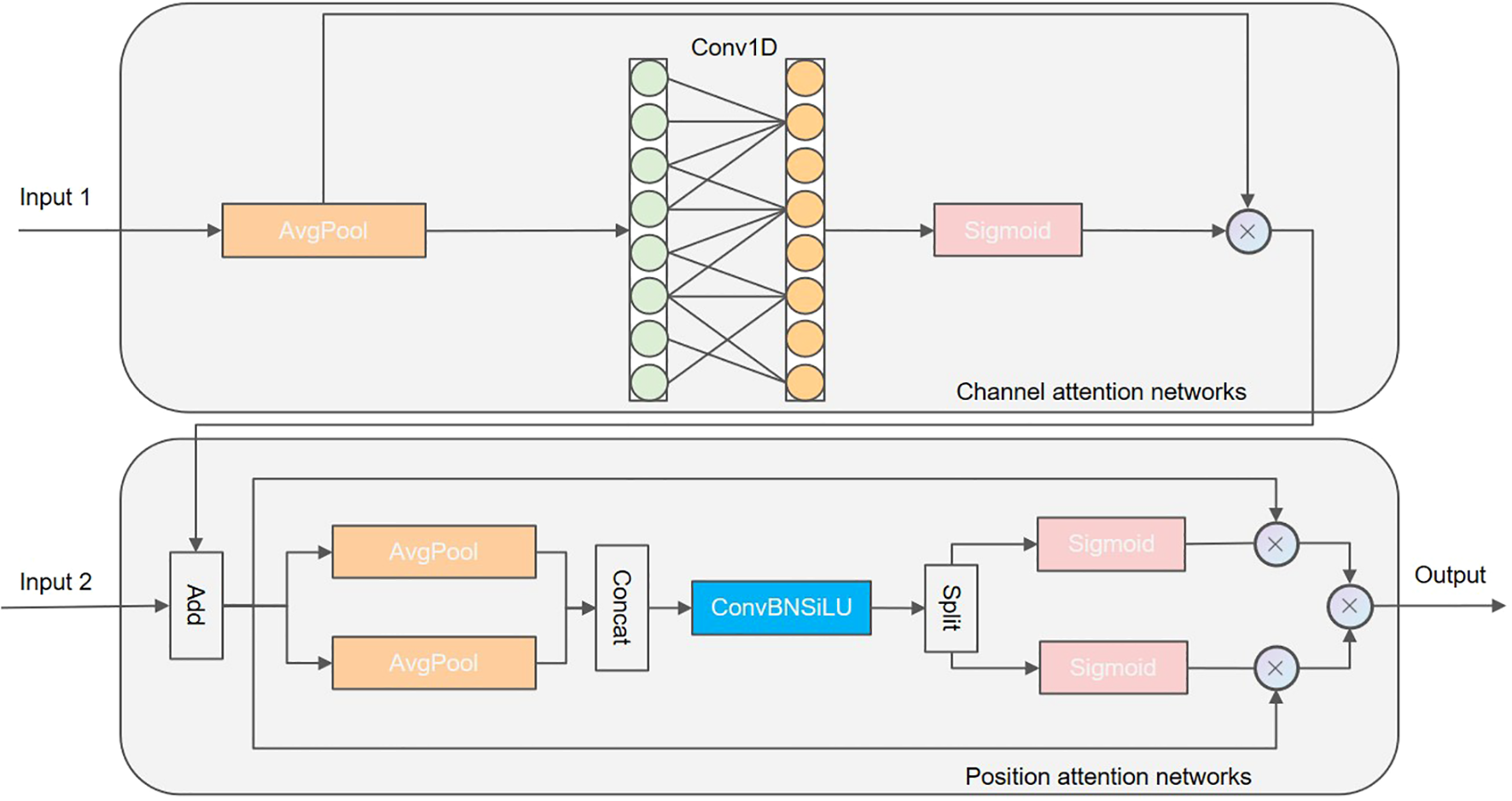

3.4 Channel and position attention mechanism

3.4.1 The CPAM architecture

The architectural configuration of the CPAM model is shown in Figure 8. It comprises a channel attention network that receives inputs from the TFE module (input 1) and a location attention network that receives inputs from the output of the channel attention network, superimposed with the SSFF (input 2). Specifically, input 1 corresponds to the feature map following enhancement by the path aggregation network (PANet), which contains the detailed features extracted by the TFE.

Figure 8

Channel and position attention mechanism (CPAM).

3.4.2 Squeeze-and-excitation network channel attention block

The SENet (Hu et al., 2018) channel attention block commences by treating each channel independently. It applies global average pooling to generate channel weights using two fully connected layers in conjunction with a nonlinear Sigmoid function. These two fully-connected layers are designed to capture nonlinear cross-channel interactions and incorporate dimensionality reduction to regulate model complexity. However, this dimensionality reduction can adversely affect the accuracy of channel attention prediction. Moreover, modelling dependencies across all channels can be both inefficient and unnecessary. Therefore, we introduced an attention mechanism that did not require dimensionality reduction to capture cross-channel interactions efficiently. After the global average pooling of channels without dimensionality reduction, local cross-channel interactions were captured by considering each channel and its k nearest neighbors. This was achieved by implementing a 1D convolution of kernel size k, where k denoted the coverage of local cross-channel interactions, i.e., the number of neighbors involved in the attentional prediction of a channel. To obtain the optimal coverage, k may need to be manually tuned for different network architectures and different numbers of convolutional modules, which is a laborious process. Given that the convolutional kernel size k is proportional to the channel dimension C, which is typically a power of 2, it can be defined Equation 3 as follows:

where γ and b are scaling parameters that control the ratio of convolution kernel size k to channel dimension C.

In Equation 4, the term odd denotes the odd number of nearest neighbors. It is assumed that the value of γ is set to 2 and that of b is set to 1. In accordance with the established nonlinear mapping relationship, the exchange of high-value channels corresponds to a longer duration, while the exchange of low-value channels corresponds to a shorter duration. Consequently, the channel attention mechanism is able to more profoundly explore multiple channel features. The output of the channel attention mechanism, combined with the features of SSFF (input 2) is provided as an input to the positional attention network to extract the key positional information of each cell. In contrast to the channel attention mechanism, the positional attention mechanism first divides the input feature map into two parts in terms of width and height, then processes the feature encoding separately, and finally merges it to generate the output. Specifically, the input feature map is pooled on the horizontal pw and vertical ph axes to preserve the spatial structure information of the feature map, which can be computed by the following Equation 5:

where W and H are the width and height of the input feature maps, respectively, and E (i, j) is the value of the input feature map at position (i, j). When generating positional attention coordinates, the application of join and convolution operations to the horizontal and vertical axes is defined as Equation 6:

where P(aw, ah) denotes the output of positional attention coordinates, Conv denotes a 1 × 1 convolution, and Concat denotes a connection.

When splitting the attention features, the location-dependent feature map pairs are generated as following Equation 7:

The variables w and h denote the width and height of the output that has been divided, respectively. The final Equation 8 of the CPAM is defined as follows:

where E denotes the weight matrix of the channel and location attention.

3.5 Experimental platform and dataset

3.5.1 Experimental environment

To ensure the smooth execution of the experiment, the initialization parameters for the key modules of the proposed UOD-YOLO underwater target detection framework were set. The experimental environment used in the study is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Configuration | Parameter |

|---|---|

| CPU | Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900K |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D |

| Operating system | Windows10 |

| Frame | Pytorch2.1 |

| CUDA | 11.8 |

| Batch Size | 16 |

| Epochs | 300 |

| Image Size | 640×640 |

Experimental environment and parameters.

The implementation of training and testing was facilitated by PyTorch 2.1.0 on a Windows 10 operating system, utilizing an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D GPU with 24 GB of video memory and an Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900K central processing unit. YOLOv11n was employed as the baseline for migration training, leveraging its pre-trained model to expedite the training process. The stochastic gradient descent optimizer was utilized to train 300 epochs, with the initial learning rate set to 0.01, the momentum was set to 0.937, with a weight decay of 0.0005, and an input image size of 640 × 640. The batch sizes were 64 and 1 for the training and testing phases, respectively.

3.5.2 Datasets

The proposed UOD-YOLO detection method was validated using three publicly available underwater datasets. Detailed descriptions of these datasets are provided below:

RUOD. This real-time UOD dataset presents numerous challenges, including fog effects, chromatic aberration, light interference, overlapping objects, and changing object shapes. The dataset contains a total of 14,000 images, the majority of which have a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. It encompasses 10 distinct categories of underwater targets: holothurian, echinus, scallop, starfish, fish, coral, diver, cuttlefish, turtle, and jellyfish. To ensure the efficacy of the training and testing processes, two non-intersecting subsets of the dataset were employed, with 9800 and 4200 images allocated to the training and testing sets, respectively. Additionally, a subset of 1960 images was randomly selected from the training set to serve as the verification set.

UTDAC. The dataset consists of a total of 5168 images for the training set and 1293 for the validation set. The images had four distinct image resolutions: 3840 × 2160, 1920 × 1080, 720 × 405, and 586 × 480. For the experiments, 516 images were randomly selected from the training set to serve as the validation set. The dataset encompasses four distinct object classes: echinus, starfish, holothurian, and scallop.

DUO. The dataset encompasses four categories: echinus, holothurian, scallops, and starfish. It contains 7782 images that have been meticulously annotated, of which 6671 were used for training purposes and 1111 for testing. The images in the DUO dataset have the typical characteristics of underwater images, including high bias, low contrast, uneven lighting, blurring, and high levels of noise. These characteristics complicate the accurate detection of different aquaculture organisms and reflect the difficulties encountered in detecting real marine environment targets.

4 Results and analysis

4.1 Estimation metrics

The measurement of detection accuracy was achieved by employing precision, recall, and mean average precision (mAP). To evaluate the computational complexity of the candidate models, it was necessary to consider the parameter size (Param), floating-point operations (FLOPs), and frames per second (FPS).

4.2 Ablation experiment

The objective of this study was to demonstrate the positive role of the key modules in our proposed UOD-YOLO underwater target detection framework, therefore enhancing the overall performance of the model. To this end, we performed ablation studies on the RUOD open-source baseline dataset. The primary framework was based on a reimplemention of the YOLOv11n algorithm, in which the YOLOv11n backbone network was replaced with RepViT. The remaining network structure remained consistent with YOLO v11n.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the ablation experiments. Among the evaluated models, Model 1 (baseline) is the YOLOv11 backbone network that was replaced with RepViT’s network. Model 2 incorporated the SSFF module to combine multi-scale feature maps. Model 3 added a TFE module to Model 2. Finally, Model 4 integrated the detailed and multiscale feature information from SSFF and TFE using channel and position attention mechanisms. The UOD-YOLO method is the system for the detection of underwater targets proposed in this study.

Table 3

| Model | Method | mAP50(%) | Parameters (M) | AvgSpeed (FPS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | SSFF | TFE | CPAM | RUOD | UTDAC | DUO | |||

| YOLOv11n | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 83.67 | 80.43 | 81.78 | 2.62 | 233.7 |

| 1 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 79.92 | 72.68 | 73.96 | 2.12 | 265.9 |

| 2 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 81.33 | 75.12 | 72.89 | 2.71 | 252.1 |

| 3 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 81.12 | 78.32 | 74.23 | 2.92 | 161.5 |

| 4 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 82.23 | 77.79 | 75.98 | 2.97 | 179.2 |

| UOD-YOLO | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 86.82 | 83.66 | 84.36 | 1.67 | 279.8 |

Results of the ablation experiments using the three datasets.

The experimental results demonstrated that each module contributed to performance improvements relative to the initial YOLOv11n model, indicating the efficacy of the reinforcement methods employed in this study for enhancing underwater detection operations. The analysis of Model 1 revealed that substituting the original YOLOv11n backbone network with the RepViT backbone network could reduce the model parameters, while slightly decreasing the mAP value. Using the RUOD dataset as an example, Models 2, 3, and 4 demonstrated that the incorporation of SSFF, TFE, and CPAM, respectively, enhanced the network’s ability to extract and fuse salient features. Specifically, the combination of SSFF with TFE and CPAM enhanced performance by 0.66% and 0.45% compared to YOLOv11n, leading to a further reduction in the number of model parameters. The proposed UOD-YOLO framework uses SSFF and TFE for neck feature fusion, while also adding CPAM. It achieved a 1.15% increase in mAP and a 36.3% decrease in the number of model parameters compared to the original YOLOv11n. Furthermore, the FPS metric was enhanced, which was crucial for achieving real-time detection because sufficient processing speeds must be attained to meet the demands of real-time detection. In general, the UOD-YOLO network exhibited superior mAP values and a reduced model size in comparison to the original YOLOv11n model, while maintaining efficient FPS rates conducive to real-time underwater target detection.

4.3 Comparative results

We compared our model with several widely recognized object detection methods, including SSD, YOLOv5n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv11n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9n, and YOLOXs. Tables 4 presents the results of the comparative study of the UOD effectiveness of different methods using the RUOD, UTDAC, and DUO datasets. In the table, bold and starred numbers indicate the best and second-best scores, respectively. It is evident that for all three datasets, UOD-YOLO achieved the optimal performance for most of the evaluated metrics, thereby substantiating the efficacy of UOD-YOLO in managing complex UOD tasks.

Table 4

| Method | Param (M) | FLOPs (G) | FPS (f·s-1) | UTDAC2020 | DUO | RUOD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | ||||

| SSD | 26.4 | 116.2 | 196 | 0.8432 | 0.5867 | 0.8314 | 0.5543 | 0.8542* | 0.4903* |

| YOLOv5n | 2.5 | 7.1 | 130 | 0.8084 | 0.5542 | 0.7978 | 0.4947 | 0.8063 | 0.4408 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 6.2 | 13.2 | 84 | 0.8251 | 0.5326 | 0.8233 | 0.5231 | 0.8487 | 0.4881 |

| YOLOv8n | 3.0 | 8.1 | 158 | 0.8162 | 0.5478 | 0.8103 | 0.5092 | 0.8112 | 0.4701 |

| YOLOv9n | 10.3 | 35.4 | 59 | 0.7883 | 0.4634 | 0.8358* | 0.5683* | 0.8354 | 0.4748 |

| YOLOv11n | 2.6 | 6.3 | 233* | 0.8043 | 0.5030 | 0.8178 | 0.5128 | 0.8367 | 0.4692 |

| YOLOXs | 0.9 | 1.1 | 212 | 0.7908 | 0.4907 | 0.7762 | 0.4834 | 0.8231 | 0.4659 |

| UOD-YOLO(Ours) | 1.6* | 4.2* | 279 | 0.8366* | 0.5721* | 0.8436 | 0.5742 | 0.8682 | 0.5232 |

A comparison between the methods applied to the UTDAC2020, DUO, and RUOD datasets.

Bold values indicate the best performance, and values marked with * indicate the second-best.

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted comparative analyses using several established methods across the three datasets. As shown in Table 4, UOD-YOLO demonstrated a competitive performance across multiple evaluation metrics, including mAP50, mAP50:95, number of model parameters, FLOPs, and inference speed measured in FPS.

Furthermore, to rigorously evaluate the generalization capability of our model, we employed an independent dataset named RUOD. This dataset expanded upon existing datasets by incorporating new species categories that were previously unrepresented and by enhancing the diversity of testing environments through carefully designed collection scenarios. This comprehensive validation framework provided a robust benchmark for assessing the adaptability of object detection models in realistic and complex underwater conditions.

The experimental results obtained using the UOD-YOLO framework across these datasets confirmed its effectiveness in UOD tasks. Specifically, as shown in Table 4, our proposed model achieved a high detection accuracy while maintaining notable efficiency advantages. This efficiency was primarily attributed to the lightweight architectural design inherited from the original YOLO framework, enabling high-performance detection with reduced computational complexity. Moreover, the results using the RUOD dataset further validated the generalization capability of the proposed method beyond the results achieved using the UTDAC2020 and DUO datasets.

4.4 Visualization

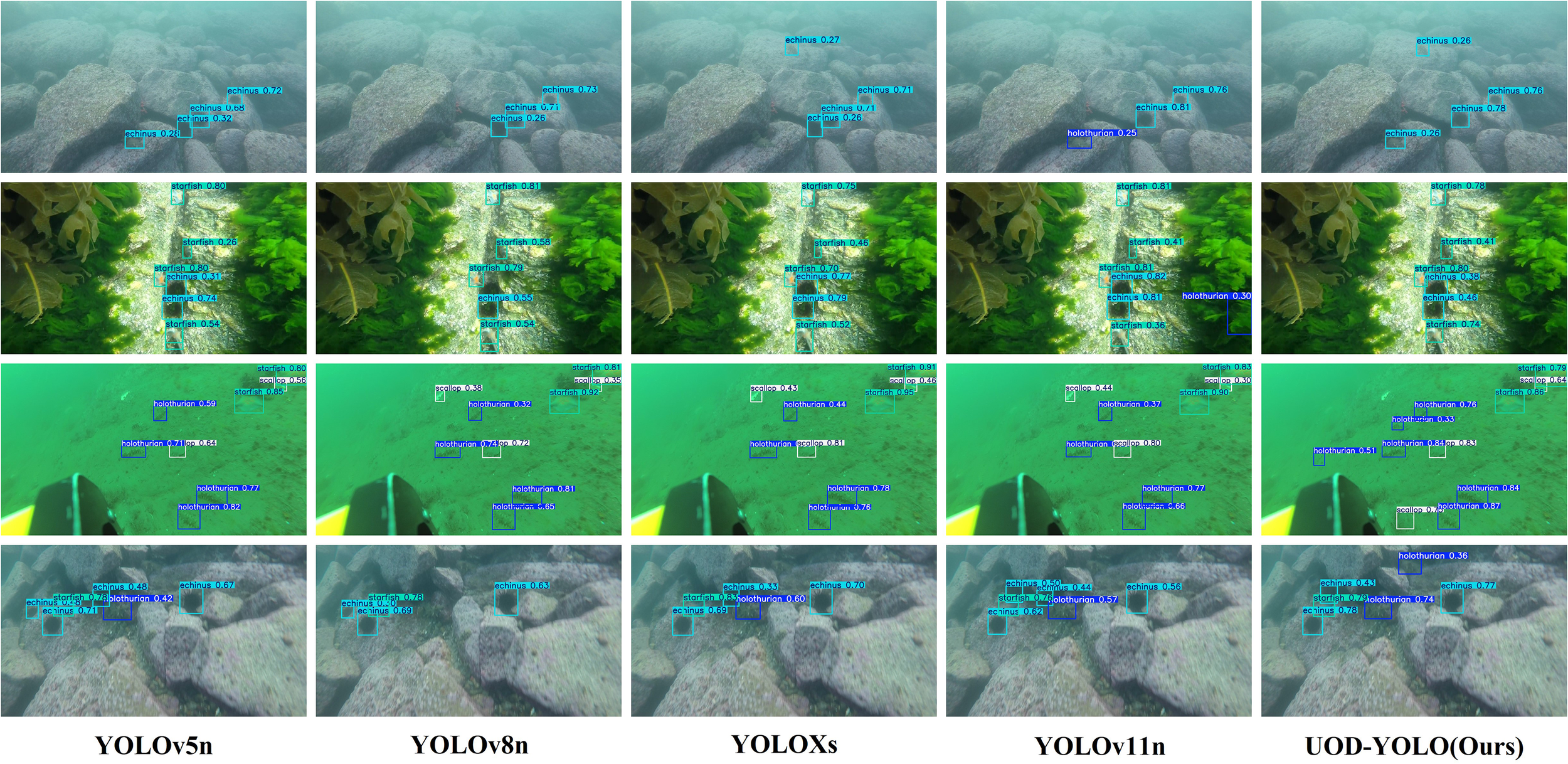

A qualitative comparison of visualization results is presented in Figure 9, which showcases the detection outcomes achieved by YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, YOLOXs, YOLOv11n, and the proposed UOD-YOLO model across representative subsets of the test dataset.

Figure 9

Detection Visualization Comparison.

Visual examination clearly demonstrated that UOD-YOLO consistently outperformed the baseline YOLOv11n model in both single-object and multi-object detection scenarios, demonstrating superior robustness and remarkable consistency. Notably, YOLOv11n occasionally produces false positives and missed detections under specific challenging conditions, whereas UOD-YOLO effectively mitigated these issues, thereby achieving enhanced accuracy and significantly reduced false detection rates.

Additionally, in particularly demanding scenarios characterized by severe lighting variations, complex backgrounds, or significant environmental interference, UOD-YOLO maintained high precision in object detection. Conversely, YOLOv11n exhibited noticeable susceptibility to these environmental disturbances, resulting in compromised detection reliability and diminished performance. The evident superiority of UOD-YOLO under these conditions highlighted its capability to robustly handle intricate visual detection tasks, demonstrating its substantial advancements and efficacy in addressing critical object detection challenges.

Although the proposed model demonstrates strong performance across RUOD, UTDAC2020, and DUO, a more complete evaluation of robustness is essential. Future work will include controlled experiments under varying illumination, turbidity, and depth conditions, as well as cross-dataset generalization and multi-seed variance reporting. Such robustness analyses are particularly important for real-world underwater deployment where environmental conditions fluctuate rapidly.

5 Conclusions

We proposed UOD-YOLO, a lightweight detection model derived from YOLOv11n, to address the challenges of real-time underwater organism detection. The proposed model achieves an elegant balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency through three key innovations. First, a lightweight CNN structure was integrated into the backbone, which was inspired by the efficient design principles of lightweight ViT, thereby reducing computational complexity. Second, SSFF and TFE modules were introduced: the former effectively fused features across different levels to enhance multi-scale information extraction, while the latter optimized the fine-grained detection of details through multi-scale feature map fusion. Finally, a lightweight detection head was developed and combined with a CPAM. This strengthened the focus on both channel and spatial information, significantly improving small-object detection. Experimental evaluations on three underwater detection benchmarks demonstrated that, compared with YOLOv11n, UOD-YOLO achieved gains of 3.5% and 6.9% in mAP50 and mAP50-95, respectively, while reducing the parameters and computational costs by 36.3% and 19.7%, respectively. Moreover, the model sustained a real-time inference speed of 279.8 FPS. The visualization results on test sets further validated the robustness and accuracy of UOD-YOLO under diverse illumination and depth conditions. Compared with mainstream detection algorithms (e.g., YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, and YOLOXs), UOD-YOLO achieved state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining a superior lightweight performance, fully meeting the real-world requirements for high-precision and low-latency underwater organism detection, including deployment on edge devices.

The lightweight design of UOD-YOLO underscored its strong engineering practicality, particularly in the following maritime monitoring scenarios: (1) mariculture and fisheries, where its low computational demand (4.2 GFLOPs) and compact memory footprint (5.4 MB) allow deployment on unmanned surface vehicles or underwater robots for real-time detection and tracking; (2) underwater surveillance systems, where compatibility with edge devices enables continuous 24/7 monitoring in resource-constrained remote stations; and (3) multi-sensor fusion, where its lightweight architecture facilitates integration with radar, automatic identification systems, and infrared sensing for enhanced situational awareness in complex environments.

Despite these promising results, two research directions merit further exploration: (1) dataset limitations — current experiments rely primarily on a single training dataset, and the inclusion of multi-source data covering different species, seasonal variations, and illumination conditions is essential for improving generalization; and (2) model compression — techniques such as pruning and knowledge distillation could be employed to further reduce model size and deployment costs without compromising detection accuracy.

Future work will focus on two main directions. First, we plan to extend the evaluation to more diverse underwater environments, including varying illumination, turbidity, and depth, and to explore cross-domain generalization under multi-site data. Second, to further reduce the computational budget and improve deployability on ultra-low-power platforms, techniques such as structured pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation will be incorporated into the UOD-YOLO pipeline. In addition, integrating multi-modal information such as sonar, acoustic sensing, and optical flow will be explored to enhance robustness under extreme underwater conditions.

In summary, UOD-YOLO provides an efficient and reliable solution for real-time underwater organism detection. The proposed method holds significant theoretical value and has practical implications for aquaculture management and marine ecological monitoring.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

YX: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JY: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Bajpai A. Tiwari N. Yadav A. Chaurasia D. Kumar M . (2024). Enhancing underwater object detection: Leveraging YOLOv8m for improved subaquatic monitoring. SN Computer Science, 5, 793. doi: 10.1007/s42979-024-03170-z

2

Bai G. Wang Z. Zhu X. Feng Y. (2022). Development of a 2-D deep learning regional wave field forecast model based on convolutional neural network and the application in South China Sea. Appl. Ocean. Res.118, 103012. doi: 10.1016/j.apor.2021.103012

3

Cai Z. Vasconcelos N. (2017). ‘Cascade R-CNN: Delving into High Quality Object Detection’, arXiv.org. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.00726 (Accessed January 10, 2025).

4

Chen J. Kao S.h. He H. Zhuo W. Wen S. Lee C. H. et al . (2023). Run, don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2303.03667

5

Chen G. Mao Z. Wang K. Shen J. (2023). HTDet: A hybrid transformer-based approach for underwater small object detection. Remote Sens.15. doi: 10.3390/rs15041076

6

Chen X. Yuan M. Yang Q. Yao H. Wang H. (2023). Underwater-YCC: Underwater target detection optimization algorithm based on YOLOv7. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.11, 995. doi: 10.3390/jmse11050995

7

Chollet F. (2017). Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions, arXiv.org. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1610.02357

8

Chuang M. Hwang J. Williams K. (2016). A feature learning and object recognition framework for underwater fish images. IEEE Trans. Image. Process.25, 1862–1872. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2016.2535342

9

Cui J. Liu H. Zhong H. Huang C. Zhang W . (2023). Lightweight transformers make strong encoders for underwater object detection. Signal, Image and Video Process.17, 1889–1896. doi: 10.1007/s11760-022-02400-2

10

Dosovitskiy A. Beyer L. Kolesnikov A. Weissenborn D. Zhai X. Unterthiner T. et al . (2021). An Image Is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale, arXiv.org. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929 (Accessed May 18, 2025).

11

Elfwing S. Uchibe E. Doya K. (2018). Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation in reinforcement learning. Neural Networks107, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2017.12.012

12

Elhaki O. Shojaei K. Mehrmohammadi P. (2022). Reinforcement learning-based saturated adaptive robust neural-network control of underactuated autonomous underwater vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl.197, 116714. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116714

13

Flyai (2020). Underwater object detection dataset. Available online at: https://www.flyai.com/d/underwaterdetection (Accessed January 10, 2025).

14

Fu C. Liu R. Fan X. Chen P. Fu H. Yuan W. et al . (2023). Rethinking general underwater object detection: challenges, and solutions. Neurocomputing517, 243–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2022.09.068

15

Gao J. Zhang Y. Geng X. Tang H. Bhatti U. A. (2024). PE-Transformer: Path enhanced transformer for improving underwater object detection. Expert Syst. Appl.246, 123253. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123253

16

Ge Z. Liu S. Wang F. Li Z. Sun J. (2021). YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.08430 (Accessed January 16, 2025).

17

Guo A. Sun K. Zhang Z. (2024). A lightweight YOLOv8 integrating fasterNet for real-time underwater object detection. J. Real-Time. Image. Process.21, 49. doi: 10.1007/s11554-024-01431-x

18

He K. Gkioxari G. Dollár P. Girshick R. (2020). Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.42, 386–397. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2844175

19

Hinton G. Vinyals O. Dean J. (2015). Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network, arXiv.org. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1503.02531

20

Howard A. Sandler M. Chu G. Chen L. C. Chen B. Tan M. et al . (2019). Searching for MobileNetV3, arXiv:1905.02244. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1905.02244

21

Howard A. G. Zhu M. Chen B. Kalenichenko D. Wang W. Weyand T. et al . (2017). MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications, arXiv:1704.04861. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861

22

Hu J. Shen L. Sun G. (2018). “ ‘Squeeze-and-excitation networks’,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 7132–7141. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745

23

Hua X. Cui X. Xu X. Qiu S. Liang Y. Bao X. et al . (2023). Underwater object detection algorithm based on feature enhancement and progressive dynamic aggregation strategy. Pattern Recogn., 139. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109511

24

Jocher G. Chaurasia A. Qiu J. (2023). Ultralytics YOLO ( GitHub). Available online at: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (Accessed March 4, 2025).

25

Kang M. Ting C. M. Ting F. F. Phan R. C. W. (2024). ASF-YOLO: A novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image. Vision Comput.147, 105057. doi: 10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105057

26

Li X. Sun W. Ji Y. Huang W. (2025a). A joint detection and tracking paradigm based on reinforcement learning for compact HFSWR. IEEE J. Selected. Topics. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens.18, 1995–2009. doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3504813

27

Li X. Sun W. Ji Y. Huang W. (2025b). S2G-GCN: A plot classification network integrating spectrum-to-graph modeling and graph convolutional network for compact HFSWR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett.22, 1–5. doi: 10.1109/LGRS.2025.3623931

28

Li J. Xu W. Deng L. Xiao Y. Han Z. Zheng H. (2023). Deep learning for visual recognition and detection of aquatic animals: A review. Rev. In. Aquacult.15, 409–433. doi: 10.1111/raq.12726

29

Li P. Zhao A. Fan Y. Pei Z. (2023). “ Research on underwater robust object detection method based on improved YOLOv5s,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA). Harbin, Heilongjiang, China. 1185–1189, iSSN: 2152-744X. doi: 10.1109/ICMA57826.2023.10215559

30

Liu W. Anguelov D. Erhan D. Szegedy C. Reed S. Fu C. et al . (2016). ‘SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.02325 (Accessed January 10, 2025).

31

Liu C. Li H. Wang S. Zhu M. Wang D. Fan X. et al . (2021). A Dataset And Benchmark Of Underwater Object Detection For Robot Picking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.05681.

32

Ngatini Apriliani E. Nurhadi H. (2017). Ensemble and fuzzy…. Expert Syst. Appl.68, 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2016.10.003

33

Redmon J. Divvala S. Girshick R. Farhadi A. (2016). “ You only look once: unified, real-time object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–788.

34

Redmon J. Farhadi A. (2017). “ YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Honolulu, HI, USA. 6517–6525.

35

Redmon J. Farhadi A. (2018). “ YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02767 (Accessed January 10, 2025).

36

Ren S. He K. Girshick R. Sun J. (2017). Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.39, 1137–1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031

37

Sandler M. Howard A. Zhu M. Zhmoginov A. Chen L. C. (2018). “ MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 4510–4520, iSSN: 2575-7075. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474

38

Schettini R. Corchs S. (2010). Underwater image processing: state of the art of restoration and image enhancement methods. EURASIP. J. Adv. Signal Process.2010, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2010/746052

39

Song P. Li P. Dai L. Wang T. Chen Z. (2023). Boosting R-CNN: Reweighting R-CNN samples by RPN’s error for underwater object detection. Neurocomputing530, 150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.088

40

Talaat F. M. ZainEldin H . (2023). An improved fire detection approach based on YOLO-v8 for smart cities. Neural Comput & Applic35, 20939–20954. doi: 10.1007/s00521-023-08809-1

41

Tiwari N. K. Bajpai A. Yadav S. Bilal A. Darem A. A. Sarwar R. et al . (2025). DM-AECB: A diffusion and attention-enhanced convolutional block for underwater image restoration in autonomous marine systems. Front. Mar. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1687877

42

Tran D. Bourdev L. Fergus R. Torresani L. Paluri M. (2015). “ Learning spatiotemporal features with 3D convolutional networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. Santiago, Chile. 4489–4497. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2015.510

43

Wang A. Chen H. Liu L. Guo R. Wang X. Ding J. et al . (2024). RepViT: Revisiting Mobile CNN From ViT Perspective. In *Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)* (pp. 15909–15920). IEEE. doi: 10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01506

44

Wang Z. Shen L. Wang Z. Lin Y. Jin Y. (2023). Generation-based joint luminancechrominance learning for underwater image quality assessment. IEEE Trans. Circuits. Syst. Video. Technol.33, 1123–1139. doi: 10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3212788

45

Wang H. Sun S. Ren P. (2024). Underwater color disparities: cues for enhancing underwater images toward natural color consistencies. IEEE Trans. Circuits. Syst. Video. Technol.34, 738–753. doi: 10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01506. iSSN: 2575-7075.

46

Wang H. Zhang W. Xu Y. Li H. Ren P. (2026). WaterCycleDiffusion: Visual–textual fusion empowered underwater image enhancement. Inf. Fusion.127, 103693. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103693

47

Xu X. Liu Y. Lyu L. Yan P. Zhang J. (2023). MAD -YOLO: A quantitative detection algorithm for dense small-scale marine benthos. Ecol. Inf.75, 204–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102022

48

Xu S. Zhang M. Song W. Mei H. He Q. Liotta A. (2023). A systematic review and analysis of deep learning-based underwater object detection. Neurocomputing527, 204–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.056

49

Yang X. LI J. Liang W. Wang D. Zhao J. Xia X. (2023). Underwater image quality assessment. J. Of. Optical. Soc. Of. America A-Optics. Image. Sci. And. Vision40, 1276–1288. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.485307

50

Yang L. Liu Y. Yu H. Fang X. Song L. Li D. et al . (2021). Computer vision models in intelligent aquaculture with … on fish detection and behavior analysis: A review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng.28, 2785–2816. doi: 10.1007/s11831-020-09486-2

51

Yang J. Xin L. Huang H. He Q. (2021). An improved algorithm for …. Comput. Mechanics.128, 779–802. doi: 10.32604/cmes.2021.014993

52

Yu G. Cai R. Su J. Hou M. Deng R. (2023). U-YOLOv7: A network for underwater organism detection. Ecol. Inf.75, 102108. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102108

53

Zeng L. Sun B. Zhu D. (2021). Lightweight underwater object detection based on YOLO v4 and multi-scale attentional feature fusion. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.100, 104190. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104190

54

Zhang M. Xu S. Song W. He Q. Wei Q. (2021). Lightweight Underwater Object Detection Based on YOLO v4 and Multi-Scale Attentional Feature Fusion. Remote Sens.13, 4706. doi: 10.3390/rs13224706

55

Zhang X. Zhou X. Lin M. Sun J. (2018). “ ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 6848–6856, iSSN:2575-7075. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00716

Summary

Keywords

deep learning, lightweight network, real-time detection, RepVit, YOLOv11n

Citation

Xi Y and Yin J (2025) UOD-YOLO: a lightweight real-time model for detecting marine organisms. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1728563. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1728563

Received

20 October 2025

Revised

26 November 2025

Accepted

30 November 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Kutubuddin Ansari, Karadeniz Technical University, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Hao Wang, Laoshan National Laboratory, China

Dr. Abhishek Bajpai, Government Engineering College, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xi and Yin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingbo Yin, jingboyin@sjtu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.