Abstract

Octocorals build characteristic sclerites within the mesoglea, traditionally described as being produced by isolated ectoderm-derived scleroblasts adjacent to the endoderm-derived canals. We revisited scleroblast organization using thick sections, cellular labeling, and confocal imaging with 3D reconstructions in two model species: the soft coral Sarcophyton sp. (Malacalcyonacea) and the precious red coral Corallium rubrum (Scleralcyonacea). In both taxa, scleroblasts were not disseminated as cell clusters but instead formed a continuous scleroblastic network intertwined with the canal system. In C. rubrum, a single sleeve-like network of scleroblasts formed an extracellular compartment enclosing growing sclerites. In Sarcophyton, two cellular networks co-occurred: a primary tubular network lining canals and a secondary dendritic meshwork, where sclerites developed within pocket-like compartments. We also observed cytoplasmic bridges spanning the mesoglea, physically linking canal cells and scleroblasts. These findings overturn the longstanding view of isolated scleroblasts and instead support a tissue-level, networked model of octocoral biomineralization.

1 Introduction

Biomineralization is an evolutionarily conserved process by which living organisms produce organized mineral structures, playing various roles in protection, mechanical support, or physiological regulation. In marine invertebrates, this process is particularly well illustrated by the formation of sclerites (or spicules) which are intracellular or extracellular skeletal elements synthesized within various phyla (Porifera, Cnidaria, Platyhelminthes, Mollusca, Echinodermata, and Ascidiacea) (Furuhashi et al., 2009; Kingsley, 1984; Sethmann and Wörheide, 2008; Vielzeuf et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2012; Wilt, 2002). Far beyond their simple structural function, sclerites constitute a privileged model for the study of fundamental mechanisms of cell biology, including cell differentiation, secretion and the dynamics of cell-matrix interactions. A detailed understanding of the mechanisms of sclerite formation is thus fundamental to decipher ancestral cellular processes underlying mineralization in metazoans.

Within Cnidaria, Octocorallia is a subclass of Anthozoa that comprises more than 3,500 species displaying a wide diversity of morphologies. It is subdivided into two main orders: Scleralcyonacea and Malacalcyonacea (Gómez-Gras et al., 2025; McFadden et al., 2022). Octocorals are colonial organisms with relatively simple histology: they are diploblastic and lack differentiated organs (Bayer, 1956). Colonies are composed of multiple polyps, also called zooids, interconnected by a common tissue known as the coenenchyma. Depending on the species, zooids may differentiate into two types: autozooids, which bear eight tentacles for feeding and predation, and siphonozooids, which lack tentacles and contribute to water circulation (Loentgen et al., 2025; Moseley, 1881; Nonaka et al., 2012). The coenenchyma is externally lined by an ectodermal cell layer exposed to seawater and internally filled with a collagen-rich connective matrix, the mesoglea. Within the mesoglea lie two main tissues: the endodermal canals, which form a network for fluid exchange between zooids, and the scleroblasts, ectodermal cells responsible for producing sclerites (see Supplementary Figure 1). Sclerites are minute calcified elements, typically a few hundred micrometers in size, and are present in the vast majority of octocorals (Conci et al., 2021). Through the biologically controlled calcification process, they grow in size and develop protuberances with species-specific morphologies (Kingsley et al., 2001; Kingsley and Watabe, 1984). The histological organization depicted above characterizes soft corals of the order Malacalcyonacea, such as Sarcophyton spp. Additionally, species of the order Scleralcyonacea develop a central skeletal axis that is usually partially calcified but may be fully calcified in certain taxa, such as the precious coral Corallium rubrum (McFadden et al., 2022). The central axis is produced and covered by a monolayer of cells (the axial epithelium (Grillo et al., 1993). Thus, most cells within the coenenchyma, situated between the ectodermal layers, are either endodermal canal cells or ectodermal scleroblasts.

Although sclerite formation in octocorals has been recognized for over 150 years, the underlying cellular processes remain only partially understood. The limited number of studies, primarily based on thin-section observations using electron microscopy across different species, has led to incongruent and sometimes contradictory descriptions of the mechanisms involved. Scleroblasts (also referred to as sclerocytes) are thought to originate from ectodermal interstitial cells before migrating into the mesoglea. Depending on the species, their morphology may vary across the stages of sclerite formation, including potential differentiation into primary and secondary scleroblasts. A two-phase model of sclerite formation has been proposed, involving an initial intracellular phase followed by an extracellular phase. Primary scleroblasts were historically reported to initiate calcification either within vesicles (e.g., Pseudoplexaura flagellosa, Sinularia gibberosa) (Goldberg and Benayahu, 1987; Jeng et al., 2011) or within an intracellular vacuole (e.g., Leptogorgia virgulata, Renilla reniformis, C. rubrum) (Dunkelberger and Watabe, 1974; Grillo et al., 1993; Kingsley and Watabe, 1982; Le Goff et al., 2017). During this intracellular phase, now commonly recognized as vacuolar, scleroblasts are characterized by a prominent nucleus that becomes displaced toward the cell periphery as the sclerite enlarges within the vacuole (Kinsley 1984, Conci et al., 2021). In the subsequent phase, the process of sclerite growth appears to vary between species or depending on the author’s interpretation. In some cases, growth continues within the vacuole until it fills the cell, as in R. reniformis (Dunkelberger and Watabe, 1974), or within a syncytial, multinucleated cell formed by several secondary scleroblasts, as observed in Alcyonium digitatum (Woodland, 1905a; Woodland, 1905b) and P. flagellosa (Goldberg and Benayahu, 1987). Sclerite growth may eventually rupture the cell membrane, releasing the sclerite into the mesoglea, as seen in Leptogorgia virgulata (Kingsley and Watabe, 1982; Watabe and Kingsley, 1992). Alternatively, the sclerite may be expelled and continue to grow inside an extracellular compartment formed by a few scleroblasts organized as cell clusters disseminated throughout the mesoglea, as in S. gibberosa, Swiftia exserta, or C. rubrum (Grillo et al., 1993; Jeng et al., 2011; Le Goff et al., 2017; Menzel et al., 2015).

Despite these differing observations, a general consensus is that sclerites are initially formed within intracellular vacuoles and may subsequently be expelled into an extracellular compartment. In the extracellular compartment sclerites can be either located within scleroblast clusters or, in some cases, found “naked” in the mesoglea (Conci et al., 2021). Still, the precise organization and arrangement of scleroblasts within the mesoglea remain poorly characterized.

In this study, we employed confocal imaging with cellular markers to gain new insights into the histological features of scleroblasts and to elucidate their spatial organization within the mesoglea of two octocoral species: Corallium rubrum, a deep-water, asymbiotic member of the Scleralcyonacea and Sarcophyton sp., a shallow-water, photosynthetic endosymbiotic member of the Malacalcyonacea. The study of Sarcophyton sp. in addition to the one with Corallium rubrum therefore allows a comparative analysis to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the diversity of biomineralization strategies of Octocorallia. We propose a revised model that, for the first time, describes the organization and positioning of scleroblasts around sclerites as a continuous cellular network.

2 Results

To investigate the histological organization of the coenenchyma in Corallium rubrum and Sarcophyton sp., we combined macroscopic observations with high-resolution confocal imaging of sectioned tissues. To distinguish between the two major coenenchymal cell types, namely canal cells and scleroblasts, we labeled tubulin in motile flagella. This approach, previously shown to specifically highlight flagellated endodermal cells of the coelenteron in scleractinian corals (Tambutté et al., 2021), was also specific to endodermal canal cells in octocorals. Together, these methods enabled the analysis of tissue architecture and the spatial relationships between coenenchymal cell types and sclerites in both demineralized and non-demineralized samples.

2.1 Observations and histological sections of Corallium rubrum

2.1.1 Histological overview of Corallium rubrum

Corallium rubrum is distinguished by the presence of red-pigmented mineralized sclerites (Figure 1A). After demineralization, thick transverse sections clearly revealed the canal network and the two polyp types, autozooids and siphonozooids, which retract into the coenenchyma during fixation (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure 1). At higher magnification, the hollow canal network could be distinguished from a second tissue type, which (as will be demonstrated below) corresponds to scleroblasts. These cells are already discernible as a distinct network embedded within the mesoglea (Figure 1C).

Figure 1

Corallium rubrum histology under conventional light microscope. (A) Branch of Corallium rubrum with expanded polyps. (B) Demineralized thick sections of the tissue showing a polyp (autozooid) and the coenenchyma with the visible canal network. (C) Higher magnification of (B) revealing the scleroblastic network between the polyp and the canals.

2.1.2 The Corallium rubrum tissues

Large confocal views of demineralized sections of the colony apex showed the broad, sac-shaped retracted polyps, clearly distinguishable from the surrounding coenenchyma (Figure 2A). Within the coenenchyma, the mesoglea does not retain staining and appears as background. Two distinct cell types can be identified. Canals are characterized by cells displaying long flagella within their lumen and a striated outer sheath (Figure 2B). These canals establish discrete connections with polyps (Figure 2C).

Figure 2

Corallium rubrum histology under confocal microscope. The apex of a branch of Corallium rubrum was fixed, demineralized, sectioned and stained with Phalloidin (in cyan) to visualize cellular actin and differentiate the cells, anti-Tubulin (in glow) to visualize the flagella that are specific to the canals, and DAPI (in white) to visualize nuclei. Confocal imaging with motorized stage of the section was acquired with 10X objective (A; Z-stack of 34µm) for a large overview and 40X objective (B–D; Z-stack of 32 µm) for a detailed view. A/Among the colony tissues, polyps can easily be discriminated from the coenenchyma (coen.), which essentially consist of the canal network and the scleroblast. The demineralized skeleton (skel.) appears as a central lightly tainted zone. At higher magnification (B–D), primary canals lining the axial skeleton (Pcan) and secondary canals (can) bare flagella lining their lumen and have striated actin fibers on their outer part (B). Canals connect with polyps via discrete connections (C). Scleroblast form a continuous highly convoluted tubular network of cells intertwined with the canal network (B–D). Note that since the preparation was demineralized, sclerites are not visible: only imprints of their presence can be imagined within some parts of the scleroblastic network (D). The ectoderm layer surrounding the coenenchyma is not discernible from the scleroblastic network (D). Cytoplasmic extensions can be seen bridging cells of the canal network and the scleroblastic network [asterix in (C, D)]. Please refer to Video_1 (Supplementary Material) for the 3D reconstruction and full appreciation. Scale bars are indicated.

In addition to the canals, a second continuous tissue type is visible. As these structures lack the features of canal cells, they are identified as scleroblasts (Figures 2B–D). Importantly, scleroblasts do not appear as isolated cells; instead, they form a continuous tubular arrangement that we propose to designate as the “scleroblastic network.” This network is highly convoluted and intricately interwoven with the canal system. In our preparations, we were unable to distinguish the outer ectodermal layer from the scleroblastic network. As the tissue was demineralized, sclerites are not present; however, their imprints can be inferred in parts of the scleroblastic network. These imprints exhibit a gradient across the coenenchyma, with more sclerites observed near the periphery and fewer near the center, adjacent to the axial skeleton (compare Figures 2B, D; see also Supplementary Figure 2).

Despite the overall histological complexity, the distinction between scleroblasts and canal cells remains clear. Supplementary Video 1, Table 1 provides a 3D dynamic visualization of this architecture, gradually zooming into the scleroblastic network and clearly highlighting its continuity.

Table 1

| Video | Figshare DOI link |

|---|---|

| Video_1 | https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042283 |

| Video_2 | https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042496 |

| Video_3 | https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042523 |

| Video_4 | https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042532 |

| Video_5 | https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042538 |

DOI links to the video files.

2.1.3 Cytoplasmic extensions as intercellular bridges

As previously shown in Figures 2C, D, cytoplasmic extensions can be seen expanding from both the canal network and the scleroblastic network (indicated by stars in C and D). To further investigate potential cell–cell interactions, we examined both thin demineralized sections (Figures 3A, B; Supplementary Video 2, Table 1) and paraffin-embedded sections (Figures 3C–E). Long cytoplasmic extensions traversing the mesoglea between canal cells and scleroblasts are visible, often forming intercellular bridges that connect the cytoplasm of the bridged cells. These long cytoplasmic extensions stain positive for phalloidin, indicating that they are composed of actin filaments. They measured up to tens of micrometers in length and approximately 2 µm in diameter. At higher magnification (Figures 3D, E), granular structures were observed within the cytoplasmic bridges. Thus, canal cells and scleroblasts are connected by large intercellular bridges with varying density, ranging from sparse (Figure 3C) to dense (Figure 3E).

Figure 3

Long cytoplasmic extensions connecting canal and scleroblastic cells in Corallium rubrum. Demineralized thick (A, B) and paraffin (C–E) sections of Corallium rubrum reveal long cytoplasmic extensions spanning the mesoglea between canal cells and scleroblasts. These extensions often form intercellular bridges. (A) Thick section labeled for actin (Phalloidin in cyan) and nuclei (DAPI in white) to visualize actin components of the cytoplasmic extensions. Imprints of sclerites present prior to demineralization are shown in light green (scl). (B) Higher magnification of A focusing on actin; Please refer to Video_2 (Supplementary Material) for the 3D reconstruction and full appreciation. (C) Demineralized paraffin sections in bright field (without staining) showing numerous extensions connecting canal and scleroblast cells; Imprints of two sclerites present prior to demineralization are delineated with dashed lines. (D, E) High magnification of cytoplasmic extensions revealing granular structures passing through the intercellular bridges. scl, demineralized sclerite imprint; can, canal; white or black arrowheads: cytoplasmic extensions extending from canal or scleroblastic cells, respectively. Scale bars as indicated.

2.1.4 Detailed observation of sclerites within the scleroblastic network

While the previous experiments demonstrated that scleroblasts form a network, demineralization only allowed us to observe sclerite imprints. To examine the relationship between the scleroblastic network and the sclerites, we prepared thick tissue sections from a portion of the coenenchyma (removed from the axial skeleton) without demineralization, and stained for actin and nuclei (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure 2). We observed that sclerites are more densely concentrated in the outer layers of the coenenchyma, with a gradient decreasing toward the center near the axial skeleton (Supplementary Figure 2; as previously observed in Grillo et al., 1993). Sclerites of Corallium rubrum appeared dark and opaque within the tissue due to their red pigmentation. Due to the abundance of sclerites at the periphery of the coenenchyma, individual sclerites and surrounding tissue were not clearly discernible. However, in regions where both sclerites and tissues could be distinguished, with canals recognizable by their striated sheath, mature sclerites (several tens of micrometers with protuberances) were found embedded within the scleroblastic network. These sclerites were surrounded by multiple cells, as judged by the number of nuclei, forming a tightly wrapped cellular sleeve that conforms to the sclerite’s shape (Figure 4). Multiple cytoplasmic extensions were also observed emanating from the scleroblastic cells surrounding the sclerite. Thus, mature sclerites appear to grow within an extracellular space formed by the scleroblastic network.

Figure 4

Sclerite localisation within the scleroblastic network of Corallium rubrum. A Corallium rubrum specimen was fixed and manually sectioned before labeling with phalloidin (see Supplementary Figure 2 for a wide-field view and Supplementary Figure 3 for detailed annotations) and imaging with confocal microscopy. (A, B) correspond to the same area, showing a scleroblastic sleeve with a sclerite in the middle, situated between two canal sections. (A) Single Z-confocal image merging bright field, phalloidin staining (in cyan), and nuclei (DAPI, in white). (B) Snapshot of the 3D reconstruction from the Z-stack encompassing the sclerite imaged in (A). mes, mesoglea; scale bar as indicated.

Hence, in Corallium rubrum, scleroblasts form a unique tubular network of calcifying cells, within which sclerites undergo their extracellular phase of maturation inside the lumen of the cellular sleeve.

2.2 Observations and histological sections of Sarcophyton sp.

2.2.1 Histological overview of Sarcophyton sp.

Sarcophyton sp. is characteristic of soft corals with a large common coenenchyma, no axial support, and polyps located on the surface of the organism. It is a shallow-water octocoral that harbors endosymbiotic photosynthetic unicellular algae (Symbiodiniaceae), which provide a partial source of autotrophic nutrition. However, few histological studies have described its internal anatomy and structures (Forin et al., 2024; Moseley, 1876).

A section of Sarcophyton sp. reveals polyps situated at the periphery of the organism and long canals, referred to as vertical canals, located beneath the polyps and extending inward from the periphery, irrigating the organism toward its center (Figures 5A, B). A close-up of the coenenchyma shows small brown dots along the inner side of the canals, corresponding to Symbiodiniaceae. Between the canals, within the mesoglea, numerous densely packed sclerites are apparent as translucent mineralized structures approximately 100 to 300 µm in length (Figure 5C).

Figure 5

Sarcophyton sp. under conventional light microscope. (A) Photograph of a colony of Sarcophyton sp. with expanded polyps. (B) Section through a lobe of Sarcophyton sp. showing retracted polyps lining the medium at the colony periphery and tubular canals running parallel to one another vertically from the polyps to the bottom of the colony in contact with the substratum. (C) High magnification of canals and surrounding tissues showing colorless sclerites and brownish unicellular algal endosymbionts (Symbiodiniaceae) visible in the lumen of the vertical canals. Scale bars as indicated.

2.2.2 The Sarcophyton sp. tissues

A large confocal view of demineralized Sarcophyton sp. revealed a structure similar to that shown in Figure 5B, with many retracted polyps at the periphery and vertical canals running parallel from the polyps to the base of the colony (Figure 6A). These canals were characterized by tubulin-positive flagella lining their inner walls, the presence of Symbiodiniaceae (detectable by their chlorophyll autofluorescence; see Supplementary Table 1), and an actin-striated sheath on their outer walls. The large vertical canals were interconnected by narrow transverse canals, ensuring homogeneous fluid distribution throughout the organism (Figure 6B).

Figure 6

Sarcophyton sp. histology under confocal microscopy. A nubbin of Sarcophyton sp. was fixed, demineralized, sectioned and stained with Phalloidin (in cyan) to visualize cellular actin and differentiate the cells, anti-Tubulin (in glow) to visualize the flagella that are specific to the canals, and DAPI (in white) to visualize nuclei; Chlorophyll autofluorescence from Symbiodiniaceae is in blue. Confocal imaging with motorized stage of the section was acquired with 10X objective (A, B; Z-stack of 450 µm) for large overviews and 20X (C; Z-stack of 67 µm) and 40X objectives (D; Z-stack of 100 µm) for a detailed view. A/In the colony, retracted polyps are visible at the periphery, each positioned on top of a large opening which prolonged to what constitute the vertical canal. B/At higher magnification, vertical canals (with flagella and Symbiodiniaceae) are connected by transverse canals. In between two canals, cellular tubes with a ladder-like shape are apparent, forming the primary scleroblastic network. C/Higher magnification reveals the actin striated canals with their flagella and Symbiodiniaceae, and next to it, the primary scleroblastic network forming compact tubular tissues and the secondary scleroblastic network, formed by a mesh a cells adopting a dendritic network shape. D/Close-up on the primary and the secondary scleroblastic network, next to a canal portion. Please refer to Video_3 and 4 (Supplementary Material) for the 3D reconstruction and full appreciation of the complex histology of the dendritic meshwork. Scale bars as indicated.

In the surrounding mesoglea, a complex cellular organization was observed: a tubular, ladder-like tissue network was visible along and between the canals, accompanied by a secondary population of cells forming a diffuse dendritic network (Figures 6C, D; Supplementary video_3, Table 1). We interpreted these two networks as the primary and secondary scleroblast networks described in other octocorals (see discussion). Both are continuous, the former forming homogeneous sheets of cells, the latter forming a branched and reticulated meshwork of cells, characterized by small cellular bodies with a central nucleus connected by long cytoplasmic extensions, reminiscent of neuronal cells’ architecture. Although discrete points of connection between the primary and secondary scleroblastic network were observed, the developmental relation between the two networks is not apprehended in this study.

Since the preparation was fixed and demineralized, sclerites only leave imprints (at least for large sclerites). We did not observe imprints within the primary scleroblastic network. However, although very faint, we could detect a thin actin staining showing the thin cytoplasm of the stretched out cell(s) inside the secondary scleroblast meshwork (Supplementary Videos 3, 4, Table 1).

2.2.3 Detailed observation of sclerites within the scleroblastic meshwork

To better understand the positioning of sclerites within the cellular networks, we repeated our labeling experiment without the demineralization step. Since the sclerites of Sarcophyton sp. are transparent, we first incubated the colony in seawater supplemented with calcein. Calcein is specifically incorporated into biominerals undergoing calcification and enables detection of the surface of growing sclerites under a fluorescent laser beam (Forin et al., 2024).

When observed under a bright-field microscope, mature sclerites with protuberances appear as naked structures within the mesoglea (Figure 7A). Under fluorescence imaging, the superficial surface of the sclerite is visible within the lace-like structures formed by the scleroblastic meshwork, which interweaves between the protuberances (Figure 7B). Supplementary Video 5, Table 1 shows, through 3D reconstruction of Figure 7B, the complexity of the entanglement between the secondary scleroblastic meshwork and the sclerites.

Figure 7

Sclerite formation within the secondary scleroblastic network of Sarcophyton. A Sarcophyton colony was incubated for 24H in calcein to label sclerites. The specimen was fixed and manually sectioned, then labeled with phalloidin and DAPI, and imaged with confocal microscope. (A) Bright field image of mature sclerites with microprotuberances (microprot.) in the mesoglea (mes). (B) Z-stack confocal imaging encompassing a superficial portion of the central sclerite imaged in (A), with the same microprotuberances indicated. Note the surrounding secondary scleroblastic network intertwining around the sclerite. Calcein: white; phalloidin: cyan; DAPI: bright green. Please refer to Video_5 (Supplementary Material) for the 3D reconstruction and full appreciation. Scale bars as indicated.

Hence, in Sarcophyton sp., scleroblasts form a continuous and complex dendritic meshwork of calcifying cells, within which sclerites appear to grow inside either in an intra-cellular or extra-cellular space, although the exact location remains to be determined.

3 Discussion

A key taxonomic feature long used for species discrimination is the observation of sclerites, small calcified structures produced by octocorals that display species-specific lengths, shapes, and arrangements of protuberances. Sclerites are thought to initially form inside vacuoles of specialized cells called scleroblasts, which were generally described as scattered throughout the mesoglea, either singly or in small groups. In this study, we revisited the histological characteristics of scleroblastic tissues in two species: Sarcophyton sp. (Malacalcyonacea) and Corallium rubrum (Scleralcyonacea), originally described in 1876 and 1864, respectively. We used large- and thick-section confocal imaging techniques to visualize scleroblast architecture. Contrary to over a century of prevailing descriptions, we found that scleroblasts in both species do not occur as isolated cells; instead, they form a continuous cellular network with two distinct architectures: a sleeve-like network in C. rubrum and a dendritic meshwork in Sarcophyton.

3.1 Revised representation of the Corallium rubrum scleroblastic network

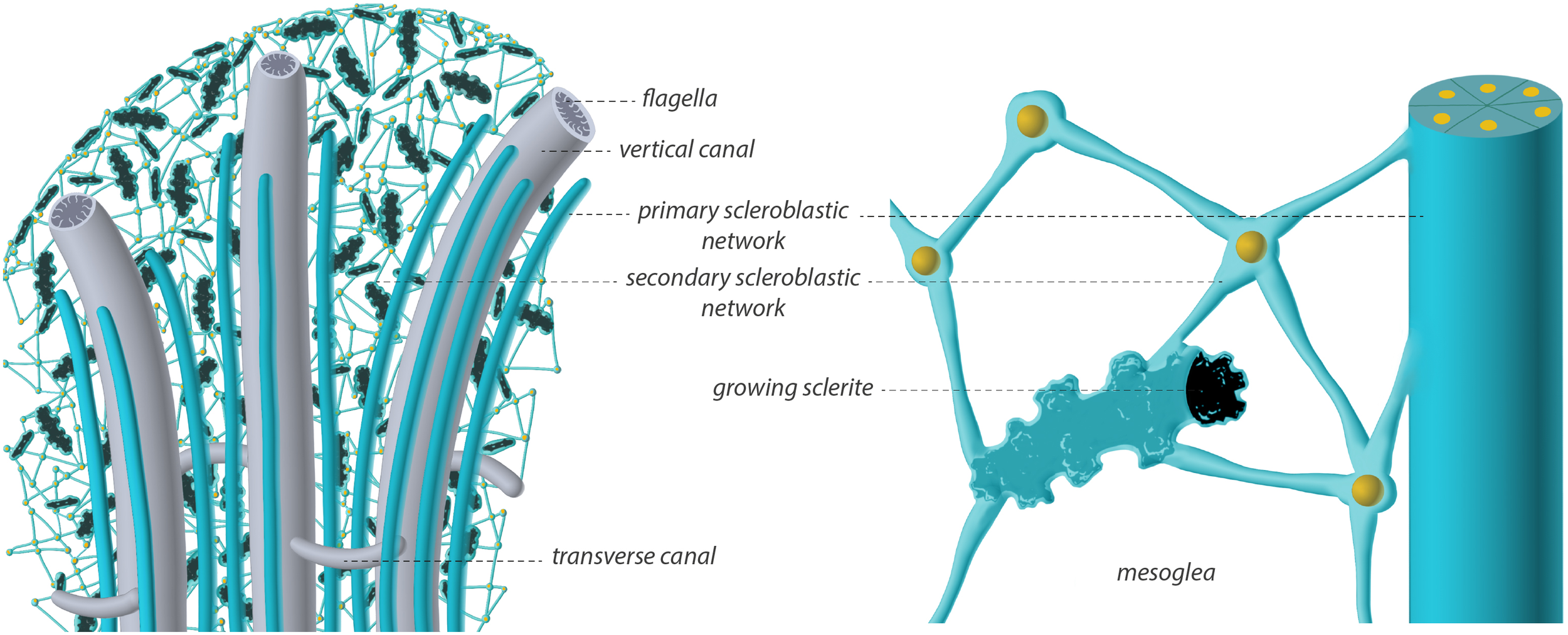

Corallium rubrum, a member of the precious corals (family Coralliidae), is characterized by red-pigmented mineralized structures that give the coenenchyma its distinctive coloration, contrasting with the expanded white polyps (Figure 1A). Its anatomy was first described in detail by Lacaze-Duthiers (1864), and subsequent studies on the Pacific precious coral Corallium japonicum have confirmed a high degree of anatomical similarity (Nonaka et al., 2012). Figure 8 presents an artistic rendering of the C. rubrum coenenchyma tissues summarizing our observations. Endodermal canals occur in two subtypes: large primary canals, running parallel to the axial skeleton, and thinner secondary canals forming a network above them (see Loentgen et al., 2025 for photographs). The canals bear long tubulin-based flagella on the luminal side and an actin-striated outer wall. Both subtypes are interconnected and connect to the polyps via discrete junctions (polyps omitted for clarity).

Figure 8

Artistic drawing illustrating the model for Corallium rubrum histology of the scleroblastic and canal networks. The left panel corresponds to a broad view showing the primary canals (grey) lining the axial skeleton, the secondary canals (grey) and the scleroblastic (green) networks entwined within the coenenchyma space, primarily filled with mesoglea. Sclerites (red) are embedded within the scleroblastic network and no naked sclerite were observed in C. rubrum. The right panel illustrates a flagellated secondary canal and a scleroblastic tube forming a closed compartment that contains a small developing sclerite and a larger mature one, which deforms the surrounding cells. Cellular nuclei are in orange. Cytoplasmic extensions bridging the cells of the two networks are depicted in grey/green to suggest their probable dual origin.

A single type of scleroblastic network was observed: scleroblasts form a continuous, tortuous tubular system entwined with the canals in the mesoglea. Canals and scleroblasts sometimes form large intercellular bridges containing granular structures, suggesting possible exchange of molecules and organelles across the mesoglea. As previously noted by Grillo et al. (1993), sclerites are more abundant at the periphery than in the center of the coenenchyma. The early intracellular stages of sclerite formation within individual scleroblasts (Le Goff et al., 2017) were not investigated here and are not depicted. Developing sclerites were located extracellularly within the lumen of the sleeve formed by the scleroblastic network. Multiple nuclei were observed surrounding a mature sclerite, indicating that several scleroblasts contribute to the formation of a single sclerite. This suggests that the number of participating cells increases from vacuolar initiation to the extracellular calcification of a sclerite with eight protuberances. As sclerites grow, they may exceed the lumen diameter, stretching surrounding scleroblasts so that their nuclei lie in the depressions between the protuberances. Notably, naked sclerites were never observed in the mesoglea of Corallium rubrum. The cellular processes underlying the progression from the round vacuolar calcified nucleus (Le Goff et al., 2017) to the fully formed extracellular sclerite remain to be elucidated.

3.2 Revised representation of the Sarcophyton sp. scleroblastic network

Figure 9 presents an artistic rendering of the Sarcophyton sp. coenenchyma, summarizing our observations. Large vertical canals, originating beneath the peripheral polyps (polyps omitted for clarity), connect to thinner transverse canals (nomenclature after Moseley, 1881), forming a network that spans the entire organism. Adjacent to the vertical canals, we observed thick ladder-like structures, here interpreted as “primary scleroblasts”.

Figure 9

Artistic drawing illustrating the model for Sarcophyton histology of the scleroblastic and canal networks. The left panel shows a broad view with transverse and vertical flagellated canals (grey) running through the colony, primary scleroblastic networks (green) forming tubes lining the vertical canals, and secondary scleroblastic networks (green) forming a dendritic network within the coenenchyma. Cellular nuclei are in orange. Sclerites (black) are maturing within the secondary scleroblastic network. The presence of naked sclerites was not determined. The right panel illustrates a tubular primary scleroblast connected to a network of secondary scleroblasts, creating an enclosed extracellular space around a maturing sclerite.

Our terminology for primary and secondary scleroblasts follows established literature on sclerite formation: primary scleroblasts are considered responsible for the early intracellular stages of calcification, whereas secondary scleroblasts are thought to participate in the formation of mature sclerites, typically bearing microprotuberances, whether located intra- or extracellularly. For descriptive purposes, we assumed that the coenenchyma contained only two main cell types: canal cells and scleroblasts, with scleroblasts being further differentiated into primary and secondary scleroblasts in some species. Secondary scleroblasts are described as being derived from primary scleroblasts. In Sarcophyton sp., no growing sclerites were detected, at our resolution, in the tissue that we interpreted as a “primary scleroblastic network”. On the other hand, this tissue lacked the endodermal markers characteristic of canals (external striated actin fibers, flagella within the lumen, and endosymbionts), supporting our designation as a primary scleroblastic network. A possible third cell type, however, cannot be excluded. The “cell cords” described in the sea whip Pseudoplexaura flagellosa consist of cellular networks containing multiple cell types, potentially serving as precursors to various differentiated cells (Chester, 1913). In P. flagellosa, scleroblasts “in early stages of crystal formation are found clustered near the edge of the cell cord” (Goldberg and Benayahu, 1987), although no large-scale tissue views were provided. By analogy, the structures we identified in Sarcophyton sp. as primary scleroblasts may alternatively represent cell cords, a possibility that warrants further investigation.

The remainder of the mesoglea was populated by dendritic-shaped cells forming a continuous meshwork. These cells correspond to scleroblasts in the strict sense, as they contained growing sclerites, and are referred to here as secondary scleroblasts. Between their nucleated cell bodies, maturing sclerites of various sizes and with distinct protuberances were enclosed by an extended cytoplasmic envelope (Supplementary Videos 3–5). Structurally, this arrangement is reminiscent of a neuronal network, with discrete cell bodies connected only through their dendritic extensions. Similar organization has been described in P. flagellosa, where scleroblasts appear interconnected by “interdigitating pseudopodia” (Goldberg and Benayahu, 1987). However, the nature of the connectivity between the canal system and the scleroblastic networks, specifically the developmental link between primary and secondary scleroblasts, remains unresolved.

In summary, Sarcophyton sp. exhibits two distinct scleroblastic systems: (1) a primary scleroblastic (or cell cord) network running alongside the vertical canals, and (2) a secondary scleroblastic network forming a dendritic meshwork within the mesoglea, where sclerite growth occurs.

3.3 Cell boundaries

In octocorals, sclerite formation is mediated by scleroblasts within a controlled microenvironment. Earlier reports proposed that scleroblast clustering around forming sclerites could be arranged as a syncytium in some species scleroblasts (Woodland, 1905a) (Goldberg and Benayahu, 1987). However, in Corallium rubrum, electron microscopy imaging showed that two individual scleroblasts surrounding a developing sclerite are separated by a continuous plasma membrane and linked by a septate junction (Le Goff et al., 2017). Septate junctions, a hallmark of individualized cells in invertebrate tissues, are intercellular junctions characterized by an intermembrane spacing of ~20 nm between adjacent plasma membranes (Ganot et al., 2015; Tambutté et al., 2007). Thus, although the resolution of our present confocal analyses is insufficient to distinguish membrane boundaries between paired scleroblasts, previous ultrastructural analyses in C. rubrum demonstrated that the scleroblastic network is composed of individual cells.

In Sarcophyton sp., the absence of electron micrographs prevents determination of whether distinct boundaries exist between the numerous scleroblasts revealed by DAPI staining of their nuclei, or of the precise nature of the cellular compartment enclosing the growing sclerites. In particular, it remains unclear whether sclerites develop entirely within a vacuole-like compartment of a single cell or within an extracellular space formed by multiple scleroblasts. However, we labeled growing sclerites within the scleroblastic network using calcein, a cell-impermeant dye. As such, calcein cannot label mineralization occurring within a closed intracellular compartment, which would require passage across both the plasma membrane and the vacuolar membrane. By contrast, calcein diffuses through extracellular spaces in anthozoan tissues, as the permselective barrier formed by septate junctions allows calcein to pass between adjacent cells (Ganot et al., 2015; Venn et al., 2011). Consistently, in other calcein-labeling experiments in which sclerites were isolated from Sarcophyton tissues following bleaching and analyzed for calcein incorporation as a function of size, labelling was observed in sclerites ranging from 50 to 300 µm in length (Forin et al., 2024, Forin et al., 2026). This indicates that the vacuolar phase of calcification is restricted to sclerites smaller than ~50 µm in Sarcophyton. Together, these observations suggest that, during most of their growth, sclerites calcify within an extracellular compartment formed by multiple scleroblasts. Ultrastructural analyses of Sarcophyton sp. will be essential to definitively resolve the histological organization of the scleroblastic dendritic meshwork.

3.4 Cell connections

Another significant observation in C. rubrum was the presence of intercellular bridges between canal cells and the scleroblastic network, as well as between cells of the same subtype. Grillo et al. (1993) previously reported such cytoplasmic extensions, although without detailed characterization. These intercellular bridges are actin-based and resemble the filopodia, cytonemes, or tunneling nanotubes described in other metazoans. Each of these terms, however, carries specific functional implications, for example, cytonemes are specialized for the exchange of signaling proteins between cells in bilaterians (Belian et al., 2023). As the molecular nature of the material exchanged between C. rubrum cells remains unknown, we retain the neutral term “bridges”.

In animals, intercellular communication and exchange rely on multiple mechanisms that depend on both the distance between cells and the nature of the information being transmitted. These mechanisms include gap junctions, cellular intercellular bridges (or analogous structures), and the diffusion of molecules through the extracellular matrix (González-Méndez et al., 2019; Heinke, 2025; Kornberg and Roy, 2014). Intercellular bridges are actin-based plasma membrane protrusions that establish cytoplasmic contacts between neighboring cells, whereas gap junctions are built around core channel-forming proteins (connexins or their homologs) that directly connect the cytosol of adjacent cells and mediate the exchange of small cytosolic molecules. Interestingly, although gap junctions have been reported in hydrozoans (a clade of Medusozoa, the sister group to Anthozoa) (Magie and Martindale, 2008), no homologs of connexins, innexins, or pannexins are encoded in octocorallian genomes (P.G., unpublished results). This absence suggests that canonical gap junctions are absent in octocorallians, thereby restricting intercellular signaling to molecular diffusion through the extra cellular matrix, such as the mesoglea, and direct intercellular bridges.

Based on our observations, these bridges appear to originate as cytoplasmic extensions from a cell of either subtype (Figure 3; Supplementary Video 2, Table 1), which then meet and connect to a cell of another subtype, forming a continuous link. In C. rubrum, these bridges can reach diameters of up to 2 µm, and the presence of granular structures within suggests the potential transfer of large cytosolic components, possibly even organelles. Such structures could therefore serve as conduits for exchange and communication between tissues otherwise separated by tens of micrometers of mesoglea.

Our histological observations indicate that bridge formation is transient, or at least unevenly distributed, within the coenenchyma: in some regions of a given preparation they are abundant, while in others they are absent. This variation suggests that bridge-based communication may be labile to endogenous stimuli or regulated in a spatiotemporal manner. Clusters of scleroblasts within the continuous scleroblastic network throughout the colony would thus be independently subjected to additional levels of developmental regulation, based on their local microenvironment, such as sclerite formation and their distance from canal cells. Such regulation would be required for the spatially coordinated production of sclerites, as well as for the supply of nutrients from the gastrodermal canals. Although the physiological conditions that promote or inhibit bridge formation remain unknown, this spatial variability may reflect a level of regulation in cell–cell communication not previously documented in octocorals. Importantly, the intercellular bridges of C. rubrum should not be confused with the dendritic processes of the secondary scleroblastic meshwork in Sarcophyton.

3.5 Fluid circulation

Although our investigation focused primarily on scleroblasts, it also revealed processes involved in the overall irrigation of an octocoral colony, specifically fluid exchange within the canal system. Octocorals possess networks of canals that connect the gastrodermal cavities of the polyps. Seawater entering through autozooids or siphonozooids forms part of this internal fluidic system. In our previous study (Loentgen et al., 2025), long-term time-lapse videos of C. rubrum demonstrated that the opening and closing of polyp mouths were synchronized across the colony (see supplementary videos in Loentgen et al., 2025). Moreover, polyp closure and contraction, which induce changes in hydrostatic pressure, were accompanied by pronounced dilation of the canals; conversely, polyp opening was associated with canal contraction. Such polyp contractions likely act as one motor driving fluid circulation within the colony, although intervals between contraction events may extend over days or even weeks.

In the present work, we further show that octocoral canals possess an external sheath of striated actin, a feature typically associated with contractile mechanisms. In addition, the canal walls are covered by tubulin-based flagella, closely resembling the motile flagella described in the coelenteric cavities of hexacorallian corals (Tambutté et al., 2021). Taken together, these observations suggest that fluid movement within the colony is driven by three coordinated mechanisms: (1) polyp contraction, (2) canal contraction, and (3) flagellar beating within the canal lumen.

4 Conclusion

Our observations reveal that scleroblasts in both Corallium rubrum and Sarcophyton are organized not as isolated units as originally described but as components of a continuous scleroblastic tissue, intimately associated with the canal system. This organization implies a high degree of cellular integration within the mesoglea, potentially facilitating the exchange of signals or metabolites relevant to biomineralization. In C. rubrum, a single, primary scleroblastic network is responsible for sclerite formation; the developing sclerite remains continuously encased within a sleeve-like cellular envelope, and naked sclerites are never observed in the mesoglea. By contrast, Sarcophyton sp. exhibits two distinct networks: a primary network forming continuous cellular sheets and a secondary network forming a dendritic meshwork, where cells contact each other only via limited cytoplasmic connection. In this species, sclerites develop within pockets of the secondary network.

This study describes the growth of maturing sclerites within scleroblastic tissues; however, their precise intracellular origin remains unresolved and represents a key target for future ultrastructural and molecular investigations. Understanding whether these organizational patterns are conserved or variable across octocoral lineages could provide valuable insight into the evolution of biomineralization strategies in this group.

5 Materials and methods

To investigate the histological organization of the coenenchyma in Corallium rubrum and Sarcophyton sp., we employed a three-step experimental approach. First, coarsely sectioned samples were examined under a macroscope to obtain an overview of tissue architecture. Second, thick sections from demineralized samples were prepared and the coenenchyma was imaged using deep confocal Z-stacks spanning several tens of microns, combined with multi-position stage acquisition to generate wide-field views. Cell boundaries were visualized by phalloidin staining of cortical F-actin, and nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Canal cells were identified by anti-tubulin immunolabeling, which specifically labels the motile flagella lining the inner wall of the canals. Finally, non-demineralized tissue sections were imaged after phalloidin labeling to integrate the spatial relationships between sclerites and the surrounding scleroblasts.

5.1 Biological materials

All aquaria were supplied with an open-circuit flow of Mediterranean seawater and coral cultures were fed daily. Corallium rubrum colonies were maintained in separate aquaria at 15°C and cultured as described in Loentgen et al. (2025). Sarcophyton sp. mother colonies were maintained in large aquaria at 25°C, following Forin et al. (2024).

Calcein labeling: Sarcophyton sp. nubbins of approximatively 3cm long were cut from the main colony and allowed to regenerate for two weeks. They were then incubated in a 1L beaker for 24 h in seawater supplemented with calcein, followed by fixation and immunofluorescence without a demineralization step.

5.2 Imaging procedures for thick sections

The protocol from fixation to immunolabeling was adapted from Ganot et al. (2015). Colony fragments of interest from C. rubrum or Sarcophyton sp. were cut with a scalpel and fixed for 24 h at 4°C in 50 ml of chilled artificial seawater/paraformaldehyde (PAF) fixation buffer [425 mM NaCl, 9 mM KCl, 9.3 mM CaCl2, 25.5 mM MgSO4, 23 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaHCO3, 100 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 4.5% PAF]. Samples were then demineralized for 24 h in 50 ml of buffer [100 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.4% PAF], rinsed three times in PBS (10 min each), and manually sliced into thin sections.

Sections were incubated in blocking buffer [1× PBS, 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), 2% BSA] for 1 h, followed by staining with phalloidin in blocking buffer (15 µl phalloidin/ml blocking buffer) for 1 h. Samples were then incubated with primary rabbit anti-AcTubK40 antibody (1:500) for 48 h at 4°C, rinsed three times in PBST (5 min each), and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000) in blocking buffer for 24 h. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI during the second PBST rinse. Finally, samples were mounted on coverslips in ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant and allowed to polymerize in the dark for 48 h before mounting on slides for confocal microscopy.

For preparations without demineralization, samples were manually cut after fixation and processed directly for phalloidin and DAPI staining. This approach is technically challenging due to the hardness of the sclerites, which necessitate larger coral sections and can hinder laser penetration during imaging.

Confocal imaging was performed using Leica SP8 confocal microscope and associated LAS-X software. Large panels were acquired using motorized stage and las-X Navigator software. 3D reconstruction videos were performed using Las-X 3D sofware, Table 1. Each channel was acquired sequentially to ascertain lack of cross-emission. Laser and PMT setups are given in the Supplementary Table 1.

5.3 Paraffin-embedded for thin sections

For paraffin-embedded sections, a branch of C. rubrum was fixed and decalcified as described above. The sample was then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and embedded in paraffin (Sigma). Seven-micrometer sections were cut on a Leica RM 2155 microtome and mounted on silane-coated glass slides (Sigma S4651-72EA). Paraffin was removed using baths of xylene substitute, followed by rehydration through a graded ethanol series ending with a Milli-Q water rinse. Sections were imaged using a Leica microscope equipped with a 40× objective and a CCD camera.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

CF: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. We thank CHANEL and the Government of the Principality of Monaco for financial support.

Acknowledgments

Artistic drawing were created by Beink Dream (www.beink.fr). We thank CHANEL and the Government of the Principality of Monaco for financial support.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to improve language and readability, with caution.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1729603/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Bayer F. M. (1956). “ Octocorallia,” In: MooreR. C. (ed) Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology Part F. Coelenterata (Lawrence, Boulder, CO/Kansas: Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press), pp. 163–231.

2

Belian S. Korenkova O. Zurzolo C. (2023). Actin-based protrusions at a glance. J. Cell Sci.136, jcs261156. doi: 10.1242/jcs.261156

3

Chester W. M. (1913). The structure of the gorgonian coral pseudoplexaura crassa wright and studer. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts. Sci.48, 737. doi: 10.2307/20022876

4

Conci N. Vargas S. Wörheide G. (2021). The biology and evolution of calcite and aragonite mineralization in octocorallia. Front. Ecol. Evol.9. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.623774

5

Dunkelberger D. G. Watabe N. (1974). An ultrastructural study on spicule formation in the pennatulid colony Renilla reniformis. Tissue Cell6, 573–586. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(74)90001-9

6

Forin C. Allemand D. Tambutté S. Ganot P. (2026). A window into vitamin effects on biomineralization in octocorals. General and Comparative Endocrinology375, 114854. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2025.114854

7

Forin C. Loentgen G. Allemand D. Tambutté S. Ganot P. (2024). In vivo injection of exogenous molecules into octocorals: Application to the study of calcification. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods22, 333–350. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10610

8

Furuhashi T. Schwarzinger C. Miksik I. Smrz M. Beran A. (2009). Molluscan shell evolution with review of shell calcification hypothesis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol.154, 351–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2009.07.011

9

Ganot P. Zoccola D. Tambutté E. Voolstra C. R. Aranda M. Allemand D. et al . (2015). Structural molecular components of septate junctions in cnidarians point to the origin of epithelial junctions in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol.32, 44–62. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu265

10

Goldberg W. M. Benayahu Y. (1987). Spicule formation in the gorgonian coral pseudoplexaura flagellosa. 1: demonstration of intracellular and extracellular growth and the effect of ruthenium red during decalcification. Bull. Mar. Sci.40, 287–303.

11

Gómez-Gras D. Linares C. Viladrich N. Zentner Y. Grinyó J. Gori A. et al . (2025). The Octocoral Trait Database: a global database of trait information for octocoral species. Sci. Data12, 82. doi: 10.1038/s41597-024-04307-8

12

González-Méndez L. Gradilla A.-C. Guerrero I. (2019). The cytoneme connection: direct long-distance signal transfer during development. Development146, dev174607. doi: 10.1242/dev.174607

13

Grillo M.-C. Goldberg W. M. Allemand D. (1993). Skeleton and sclerite formation in the precious red coral Corallium rubrum. Mar. Biol.117, 119–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00346433

14

Heinke L. (2025). Connecting cells through TNT. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.26, 6–6. doi: 10.1038/s41580-024-00811-2

15

Jeng M.-S. Huang H.-D. Dai C.-F. Hsiao Y.-C. Benayahu Y. (2011). Sclerite calcification and reef-building in the fleshy octocoral genus Sinularia (Octocorallia: Alcyonacea). Coral. Reefs.30, 925–933. doi: 10.1007/s00338-011-0765-z

16

Kingsley R. J. (1984). Spicule formation in the invertebrates with special reference to the gorgonian leptogorgia virgulata. Am. Zool.24, 883–891. doi: 10.1093/icb/24.4.883

17

Kingsley R. J. Corcoran M. L. Krider K. L. Kriechbaum K. L. (2001). Thyroxine and vitamin D in the gorgonian Leptogorgia virgulata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol.129, 897–907. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00354-3

18

Kingsley R. J. Watabe N. (1982). Ultrastructural investigation of spicule formation in the gorgonianLeptogorgia virgulata (Lamarck) (Coelenterata: Gorgonacea). Cell Tissue Res.223, 325–334. doi: 10.1007/BF01258493

19

Kingsley R. J. Watabe N. (1984). Synthesis and transport of the organic matrix of the spicules in the gorgonian Leptogorgia rirgulata(Lamarck) (Coelenterata: Gorgonacea). Cell Tissue Res. (1984) 235, 533–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00226950

20

Kornberg T. B. Roy S. (2014). Cytonemes as specialized signaling filopodia. Development141, 729–736. doi: 10.1242/dev.086223

21

Lacaze-Duthiers H. de (1821–1901). (1864). Histoire naturelle du corail, organisation, reproduction, pêche en Algérie, industrie et commerce. Paris. doi: 10.5962/bhl.title.11563

22

Le Goff C. Tambutté E. Venn A. A. Techer N. Allemand D. Tambutté S. (2017). In vivo pH measurement at the site of calcification in an octocoral. Sci. Rep.7, 11210. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10348-4

23

Loentgen G. Parks S. K. Allemand D. Tambutté S. Ganot P. (2025). Polyp dimorphism in the Mediterranean Red Coral Corallium rubrum: siphonozooids are precursors to autozooids. Front. Mar. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1512361

24

Magie C. R. Martindale M. Q. (2008). Cell-cell adhesion in the cnidaria: insights into the evolution of tissue morphogenesis. Biol. Bull.214, 218–232. doi: 10.2307/25470665

25

McFadden C. S. Van Ofwegen L. P. Quattrini A. M. (2022). Revisionary systematics of Octocorallia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) guided by phylogenomics. Bull. Soc Syst. Biol.1. doi: 10.18061/bssb.v1i3.8735

26

Menzel L. P. Tondo C. Stein B. Bigger C. H. (2015). Histology and ultrastructure of the coenenchyme of the octocoral Swiftia exserta, a model organism for innate immunity/graft rejection. Zoology118, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2014.09.002

27

Moseley H. N. (1876). On the structure and relations of the alcyonarian heliopora caerulea, with some account of the anatomy of a species of sarcophyton, notes on the structure of species of the genera millepora, pocillopora, and stylaster, and remarks on the affinities of certain palaeozoic corals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc Lond.166, 91–129. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1876.0004

28

Moseley H. N. (1881). Report on certain hydroid, alcyonarian, and madreporarian corals procured during the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-76. Part III. On the deep-sea Madreporaria. Rep. Sci. Results Voyage HMS Chall. Years 1873–76 Zool. London: Longmans & Co.

29

Nonaka M. Nakamura M. Tsukahara M. Reimer J. D. (2012). Histological examination of precious corals from the ryukyu archipelago. J. Mar. Biol.2012, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2012/519091

30

Sethmann I. Wörheide G. (2008). Structure and composition of calcareous sponge spicules: A review and comparison to structurally related biominerals. Micron39, 209–228. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2007.01.006

31

Tambutté É. Allemand D. Zoccola D. Meibom A. Lotto S. Caminiti N. et al . (2007). Observations of the tissue-skeleton interface in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Coral. Reefs.26, 517–529. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0263-5

32

Tambutté E. Ganot P. Venn A. A. Tambutté S. (2021). A role for primary cilia in coral calcification? Cell Tissue Res.383, 1093–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00441-020-03343-1

33

Venn A. Tambutté E. Holcomb M. Allemand D. Tambutté S . (2011). Live Tissue Imaging Shows Reef Corals Elevate pH under Their Calcifying Tissue Relative to Seawater. PLoS ONE6, e20013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020013

34

Vielzeuf D. Floquet N. Perrin J. Tambutté E. Ricolleau A. (2017). Crystallography of complex forms: the case of octocoral sclerites. Cryst. Growth Des.17, 5080–5097. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00087

35

Wang X. Schloßmacher U. Wiens M. Batel R. Schröder H. C. Müller W. E. G. (2012). Silicateins, silicatein interactors and cellular interplay in sponge skeletogenesis: formation of glass fiber-like spicules. FEBS J.279, 1721–1736. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08533.x

36

Watabe N. Kingsley R. J. (1992). “ Calcification in octocorals,” in Hard Tissue Mineralization and Demineralization. Eds. SugaS.WatabeN. ( Springer Japan, Tokyo), 127–147. doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-68183-0_9

37

Wilt F. H. (2002). Biomineralization of the spicules of sea urchin embryos. Zool. Sci.19, 253–261. doi: 10.2108/zsj.19.253

38

Woodland W. (1905a). II.—Spicule formation in alcyonium digitatum; with remarks on the histology. J. Cell Sci.S2-49, 283–304. doi: 10.1242/jcs.s2-49.194.283

39

Woodland W. (1905b). Studies in spicule formation.: I.—The development and structure of the spicules in sycons: with remarks on the conformation, modes of disposition and evolution of spicules in calcareous sponges generally. J. Cell Sci.S2-49, 231–282. doi: 10.1242/jcs.s2-49.194.231

Summary

Keywords

biomineralization, Corallium rubrum , histology, red coral, spicules

Citation

Forin C, Loentgen G, Allemand D, Tambutté S and Ganot P (2026) Scleroblasts, the sclerite forming cells in octocorals, form a continuous network throughout the mesoglea. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1729603. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1729603

Received

21 October 2025

Revised

19 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

14 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Yehuda Benayahu, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Reviewed by

Shan-Hua Yang, National Taiwan University, Taiwan

Xuelei Zhang, Ministry of Natural Resources, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Forin, Loentgen, Allemand, Tambutté and Ganot.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philippe Ganot, pganot@centrescientifique.mc

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.