Abstract

Offspring and kin care are common in nature, while non-kin societies are unusual due to their susceptibility to cheaters. Here, we investigated the kinship of mast-building amphipods, Dyopedos bispinis (Gurjanova, 1930). Our goal was to determine if all mast inhabitants are descendants of a single founder female or if they represent a more complex social structure. We sequenced and assembled the complete mitochondrial genome of D. bispinis along with 58 partial genomes from four masts. One of the studied masts contained several adult females with embryos, all of which had identical partial mitochondrial genome sequences. This shows that masts can be inhabited by individuals from different generations. Mitochondrial genome sequences of ten mother-embryo pairs confirm maternal mtDNA inheritance in D. bispinis. However, another mast contained several groups of female individuals exhibiting pronounced (~0.7 substitutions per 1000 b.p.) distance between the groups. The genetic distance between groups from the same mast was not less than the genetic distance from specimens of other masts. This suggests collective usage of the mast by non-related families. If it is true that several female D. bispinis individuals invest resources into maintaining one mast, this case may suggest non-kin cooperation among amphipods. Overall, our study provides an insight into the family structures of mast-inhabiting amphipods and presents a new model for studying shared construction exploitation by distantly related individuals.

1 Introduction

Animals are capable of forming complex societies with distinct roles and kin relationships among individual members. Animal social structures and cooperation are primarily explored in vertebrates with developed sensor systems and cognitive abilities (Clutton-Brock, 2021) and in social insects, such as Hymenoptera and termites (da Silva, 2021). At the same time, intraspecific cooperation remains scarcely and non-systematically studied in other groups (see discussion in Elgar, 2015), potentially leading to an underestimation of their social complexity. Meanwhile, one such group, сrustaceans, exhibits significant morphological and ecological diversity and is capable, similarly to insects, of constructing a variety of individual and communal structures (Atkinson and Eastman, 2015; Moore and Eastman, 2015). Moreover, certain crustaceans have complex levels of social organization, including true eusociality among some shrimp species, exhibited by cooperative brood care, overlapping generations, and a division of labor (Ashrafi and Hultgren, 2023; Duffy et al., 2000; Duffy and Thiel, 2007; Duffy, 2007).

Amphipods are a diverse, abundant, and ecologically significant group of crustaceans (Ritter and Bourne, 2024). Two amphipod families, Dulichiidae and Protodulichiidae, construct unique vertical structures called masts (Ariyama and Hoshino, 2019; Corbari and Sorbe, 2018; Neretin et al., 2017). These masts, made of secreted silk and detritus, elevate the crustaceans far above the bottom, exceeding their body length multiple times. Constructing masts provides protection from predators and increases feeding efficiency (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989; Thiel, 1999a).

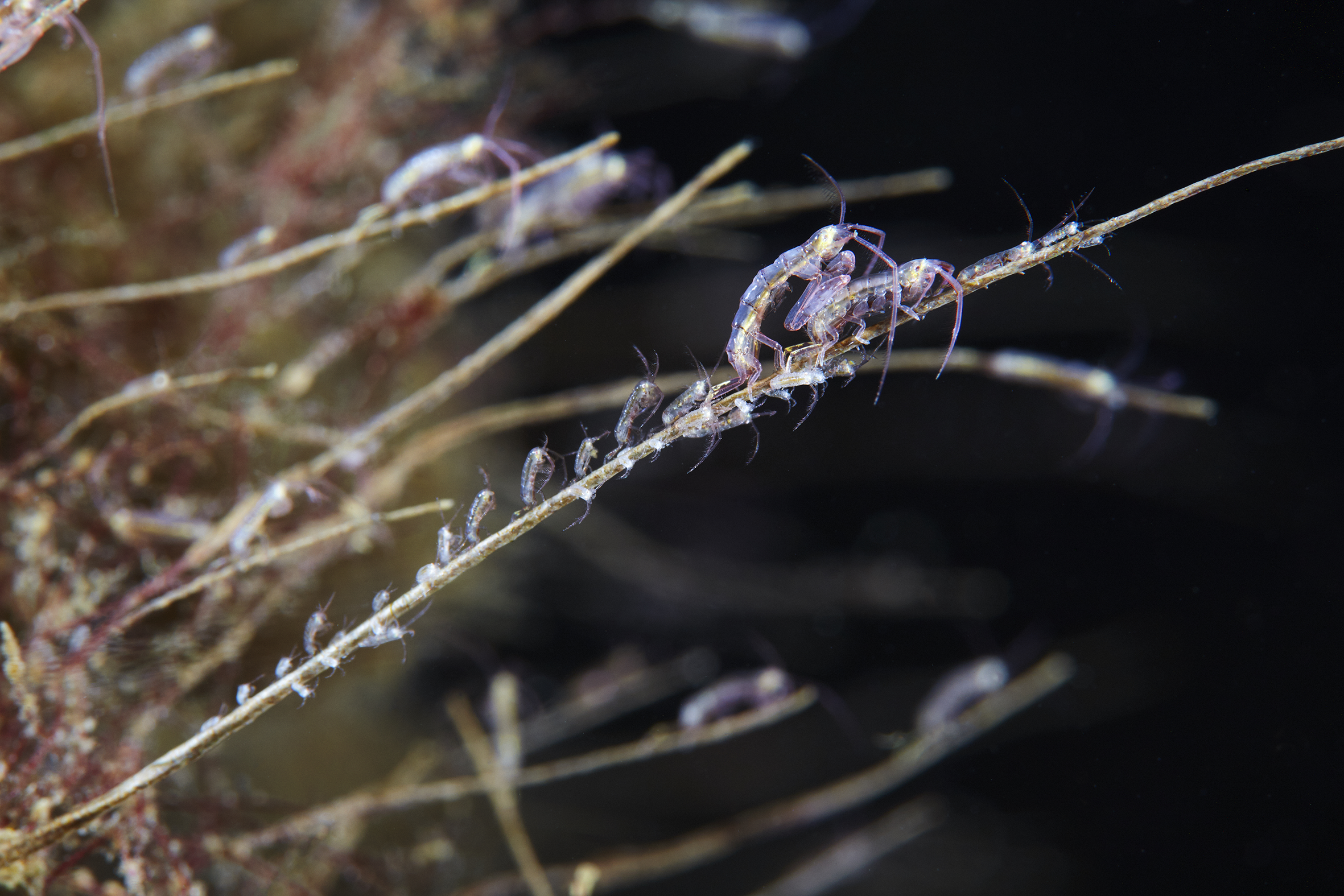

Usually, amphipod constructions are inhabited by a single adult crustacean which protects it from representatives of its species. However, in many cases, the adult female’s structure may also be used by offspring, indicating long-term care of the offspring (Palaoro and Thiel, 2020; Thiel, 2003, 2007). In the case of corophioid amphipods, the females are usually sedentarian whereas males are less attached to the constructions and tend to wander. Often the female may share the building with the male for some time (Borowsky, 1983; Thiel, 2007). Dulichiids and their masts are no exception; Figure 1 shows such a mast inhabited by a female, a male, and the offspring. At the same time, dulichiids exhibit one of the most pronounced extended care of offspring among amphipods. Since the offspring remain on the parental mast for a long time, up to three of a mother’s successive broods can inhabit a mast simultaneously (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989; Thiel, 1997, 1998). Furthermore, recently we found “collective” masts of the amphipod Dyopedos bispinis (Gurjanova, 1930) in the White Sea; these masts, at least in some cases, are characterized by their increased length and are inhabited by several adult female crustaceans (Neretin et al., 2017).

Figure 1

Underwater photograph of a Dyopedos bispinis mast with two adults and several immature specimens. (White Sea, Kandalaksha Gulf, N66.56° E33.11°, 2019, credit Alexander Semenov).

The discovery of collective masts raised questions about the kin relationship of their inhabitants. To test if the collective masts are inhabited by a progeny of a single founding female, we sequenced significant portions of mitochondrial genomes from 58 individuals from two such collective masts as well as two ordinary lone-female masts. Mitochondrial genomes contain regions with various levels of conservation (e.g. COX1), and in most Metazoa, mitochondrial DNA is transmitted from the mother (Birky, 2008). Therefore, mitochondrial genetic markers are convenient for pedigree reconstruction.

It should be mentioned that there are some invertebrate species that deviate from purely maternal mtDNA inheritance. For example, some bivalves exhibit doubly uniparental mtDNA inheritance (DUI), where females inherit mtDNA from mothers whereas males inherit from both parents (Breton et al., 2007). Next, some invertebrates, including arthropods, harbor mitochondrial genomes split into several circular or linear chromosomes (Lavrov and Pett, 2016; Najer et al., 2024). Finally, copepod hybrids can inherit high proportions of paternal mitochondrial DNA (Lee and Willett, 2022). Therefore, we also sequenced several mother-embryo pairs to ensure that our kinship reconstruction is not affected by paternal mtDNA inheritance.

In this study, we investigated the kin structure of collective dulichian masts. We analyzed masts containing multiple adult female individuals to determine whether they are the progeny of a single founding female or if they independently settled and cohabited the masts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Specimen collection and identification

The material was collected from the White Sea (Onega Bay, Solovetsky Islands, Bolshoy Solovetsky Island, “Pesya Luda” dive site, 65° 01.180’ N, 35° 39.721’, see Site 1 in Yakovis and Artemieva, 2015, depth 9–11 m) in August 2022 by scuba diving (Supplementary Table S1). Divers collected masts with one or more than two adult individuals. The masts were plucked with forceps near the mast base and carefully placed in individual tubes that were immediately closed. The specimens were fixed in 96% ethanol. Two collective masts and two masts with normal specimen composition (i.e. single adult female) were used in the population composition analysis.

Taxonomic identification was conducted according to Gurjanova (Gurjanova, 1951) and Laubitz (Laubitz, 1977) to the genus level for all adult individuals and to the species level for adult males. Given that 15 specimens were identified as Dyopedos bispinis (Gurjanova, 1930) and all females as Dyopedos sp., it was assumed that other species of Dulichiidae were not represented in the collection, which was subsequently verified by molecular methods (see below). Amphipod sex was determined by the size and shape of gnathopods 2 and the characteristic shape and position of the body (see figures in Neretin et al., 2017; Laubitz, 1977). Females with embryos in marsupia and males longer than 4 mm were recognized as reliably sexually mature. The others were considered juvenile out of caution, though the largest of them are quite probably ready for reproduction.

Additionally, material from the Kandalaksha Gulf of the White Sea was used: one specimen each of D. bispinis (ZMMU WS20509) and Dyopedos porrectusSpence Bate, 1857 (ZMMU WS22367), see details in the Supplementary Table S1.

In order to extract total DNA, whole juveniles or fragments of large adult amphipods (pleon and 2–3 posterior segments) were placed into the Worm lysis buffer (Williams et al., 1992).

In the case of females with embryos in marsupia, DNA was isolated from the female and embryos separately. DNA was isolated from the entire group of embryos, except for one group where it was isolated separately from each embryo.

A total of 47 individual animals and 12 groups of embryos from marsupia were used in the analysis; the full list is in Supplementary Table S1. DNA, fragments of used adult individuals, and unused individuals are stored in the White Sea branch of the Zoological Museum of Moscow State University (ZMMU WS, Supplementary Table S1). We took photographs of some amphipods using a phone mounted on an MBC-10, YEGREN Mount-W. The sizes of these individuals (rostrum to telson) were measured on these photographs using the ImageJ software package, see Supplementary Table S1.

2.2 Whole-genome DNA sequencing

DNA was extracted using a QIAamp Fast DNA Tissue Kit. DNA libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit by New England Biolabs (NEB, MA, USA) and the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (96 Unique Dual Index Primer Pairs Set 3) by NEB following manufacturer protocol. The samples were amplified using ten cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The constructed libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiniSeq with a paired-end read length of 150.

Pair-end reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic software (Bolger et al., 2014) with options (ILLUMINACLIP:adapters: 2:30:10 LEADING: 3 TRAILING: 3 SLIDINGWINDOW: 4:20 MINLEN: 36).

2.3 De novo assembly of D. bispinis and D. porrectus reference mitochondrial genomes

The whole genome sequence of sample ZMMU WS20509 was used to obtain the reference mitochondrial genome of D. bispinis as follows. De novo contigs were assembled using SPAdes v3.15.4 software (options -only-assembler -k 21,33,55,77) (Bankevich et al., 2012). Nucleotide sequences of the COX1 gene of the Dulichiidae family were searched in the GenBank database, and 19 available partial sequences were compared to the de novo assembly of sample ZMMU WS20509 using BLASTn software. Top hits were found in one of the contigs. It was 14,913 bp in length, which is close to the 15 kb length of mitochondrial genomes that is typical for many invertebrate species. We were able to annotate all mitochondrial genes in this contig (see below). The beginning and end of this contig overlapped by 77 nucleotides. Thus, we obtained a circular mitochondrial genome, 14,836 bp in length. Additionally, we compared this contig back to the de novo assembly of sample ZMMU WS20509 to ensure that no other potential mitochondrial contigs are present in this assembly. Sequence reads were mapped back to the reference assembly using Bowtie2 software (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) to ensure high coverage of every base and concordance of reads and reference sequence: no significant SNPs and indels were found in the reads. Reads matched the reference sequence along all positions except the ~200 bp region between positions 11,200 and 11,400, where the assembly was circled based on the 77-bp overlap of the ends (between positions 11,287 and 11,363). In this region we observed a spike in coverage and heterozygosity in reads. We resequenced this region using Sanger technology, and fully confirmed the reference sequence between positions 11,098 and 11,427. Mapping the original reads to the resulting assembly showed a mean read depth equal to 444 read bases per map position. Mitochondrial genome of D. bispinis was submitted to GenBank, accession number: PQ037584.

The mitochondrial genome of D. porrectus was obtained the same way using the whole genome sequence of sample (ZMMU WS22367); the resulting genome was 14,853 bp in length and also contained all standard mitochondrial genes.

2.4 Sample sequencing, LR-PCR

LR-PCR provides a fast and cheap method for studying mtDNA genetic diversity in a species with a known mitochondrial genome. For most of the specimens we amplified the genomic DNA with Long-Range PCR and sequenced the products. Long-range amplification of several overlapping regions of the mitochondrial genome allowed us to increase its coverage. The available mitochondrial genome enabled us to design eight pairs of primers for long-range PCR (LR-PCR, Supplementary Table S2). The primers were designed in such a way that PCR with these primers amplifies DNA fragments that would completely cover the entire mitochondrial genome of D.bispinis. Primers were designed using Primer-Blast online software. In some cases, nested primers were also used. The Long-Range PCR products were generated using Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, China). The PCR setup was as follows: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Then, the amplicons belonging to one sample were pooled proportionally to their total genomic concentration. Each pool was sheared on a Covaris S220 (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) to a target size of ~350–400 bp. The libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit by New England Biolabs (NEB, MA, USA) and the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (96 Unique Dual Index Primer Pairs Set 3) by NEB following manufacturer protocol. The constructed libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiniSeq with a paired-end read length of 150. Raw sequencing data is submitted to SRA, BioProject accession number: PRJNA1374444.

Pair-end reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic software (Bolger et al., 2014) with the same options as it was done for Whole Genome Sequencing reads: ILLUMINACLIP:adapters: 2:30:10 LEADING: 3 TRAILING: 3 SLIDINGWINDOW: 4:20 MINLEN: 36.

2.5 Annotating mitochondrial genes in the reference sequence

Mitochondrial genes were annotated using a MITOS2 web-server (with genetic code set to 5: Invertebrate) (Bernt et al., 2013). tRNA-Phe was annotated with a MITOS web-server. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the rRNA genes were defined as immediately adjacent to the ends of the flanking tRNAs. The 3′ end of the s-rRNA, not being flanked by any of tRNAs, was annotated as follows: we used the mitochondrial genome sequence of sample ZMMU WS19139 (assembled the same way as the reference sequence), where MITOS2 web-server was able to annotate s-rRNA, and transferred the 3’ coordinate to the reference sequence by aligning two genomes. Finally, the annotation was manually refined.

2.6 Haplotype network structure analysis

First, Illumina sequence reads for each sample were mapped to the reference sequence using Bowtie2 software (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). SNPs and indels were called using the combination of samtools mpileup (-B --max-depth 100000 -uf) and bcftools call (--ploidy 1 -vc) software (Danecek et al., 2021). Variable positions with SNP QUAL<3, 100 bp regions at the beginning and end of the assembly, and four sites containing SNPs near short (1–2 bp) indels, were discarded. In the following analysis we used only sites that were covered by ≥20 reads in each sample. The final dataset comprised 59 samples and ~7,300 positions. 259 sites were variable among this dataset, and 2770 SNPs in total were called for all samples; in 97% of the cases, the fraction of reads supporting the alternative variant exceeded 90%, and in the rest of cases it exceeded 76%. Overall, we ended up with a dataset containing 59 samples that share 7,299 positions with ≥20x coverage without significant internal polymorphism in mapped reads. Among these sites, 259 were polymorphic, 99 of which carried substitutions in exactly one sample. Regions included in this dataset and variable sites are shown in Figure 2A and Supplementary Data S1. A haplotype network was constructed in Pop-Art (Leigh et al., 2015) with the TCS network method (Clement et al., 2002) using a 95% connection limit.

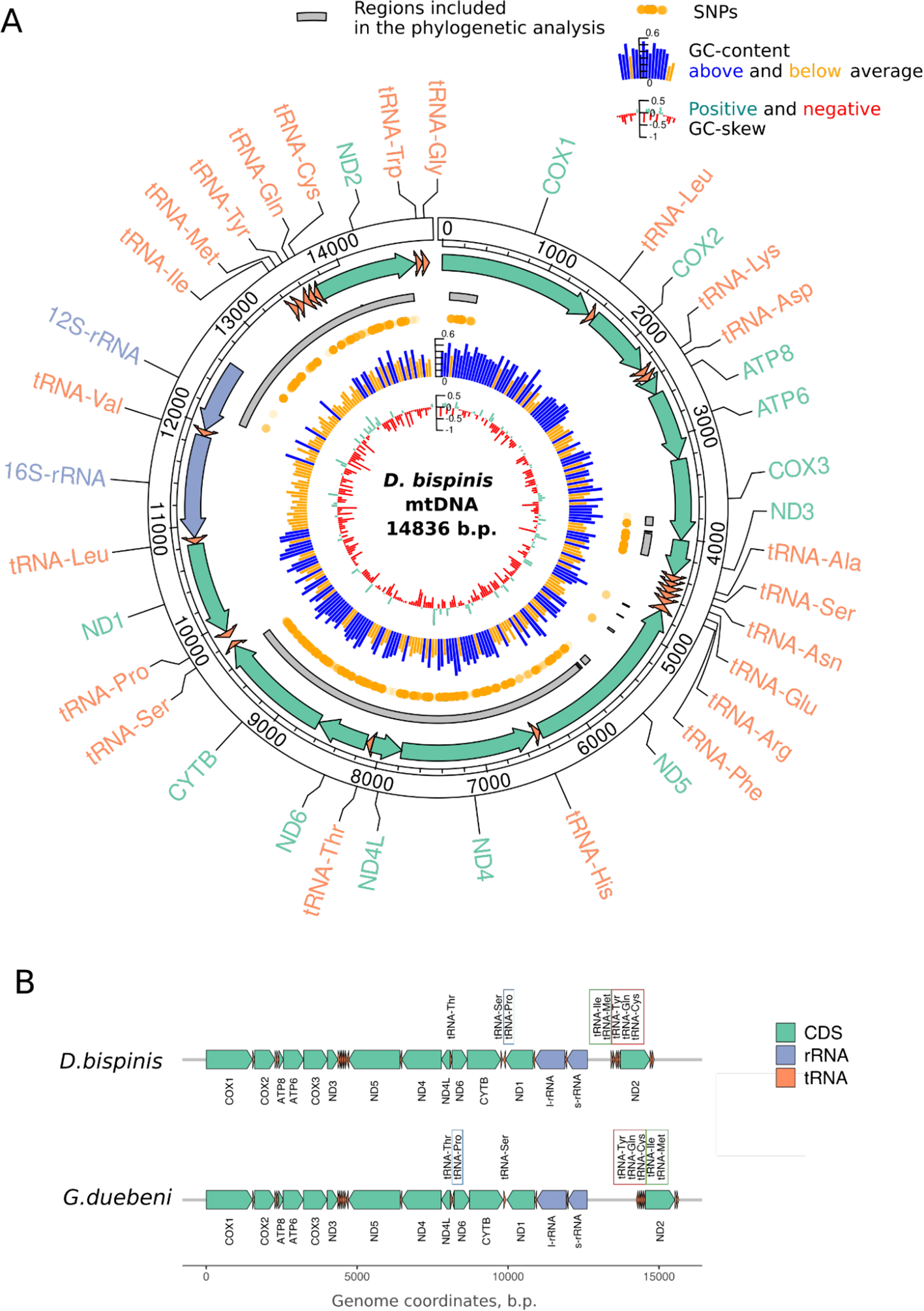

Figure 2

Mitochondrial genome of Dyopedos bispinis. (A) Genome map, where the outer track represents the boundaries of standard mitochondrial PCGs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. Arrow direction corresponds to the coding strand. Regions amplified by long-range PCR and included in phylogenetic analysis are shown in grey. Polymorphic sites are depicted with orange dots in the next track. GC content is shown in blue (above average) and yellow (below average); average GC content is 35%. GC skew index is shown in green (≥0) and red (<0). (B) Comparison of D.bispinis mitochondrial genome architecture with the Gammarus mitochondrial genome. tRNAs that changed locations between Dyopedos and Gammarus are outlined with rectangles.

We also repeated our analysis with a lower (10x) coverage threshold (328 variable sites among 8,876 bp), and found no significant difference in the results.

2.7 Phylogenetic analysis

We reconstructed a phylogenetic tree of D. bispinis, D. porrectus and several species of Gammarus genus (for which complete mitochondrial genomes are available in GenBank) based on the fragment of the COX1 gene. In some of the samples sequenced in this study COX1 gene was fully covered by reads; in some, the first ~920 nucleotides were covered; in some samples, COX1 gene was not covered. For the reconstruction of the tree, we used the first 900 nucleotides of the gene in D. bispinis samples (where available) and aligned them to complete sequences of COI from D. porrectus and several Gammarus species. There were no internal gaps in the alignment. Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the IQtree (v.2.4.0) (Hoang et al., 2018; Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017; Minh et al., 2020) with a model TIM2+F+I+G4 (automatic standard model selection) and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was rooted in the branch that separates Dyopedos and Gammarus clades.

3 Results

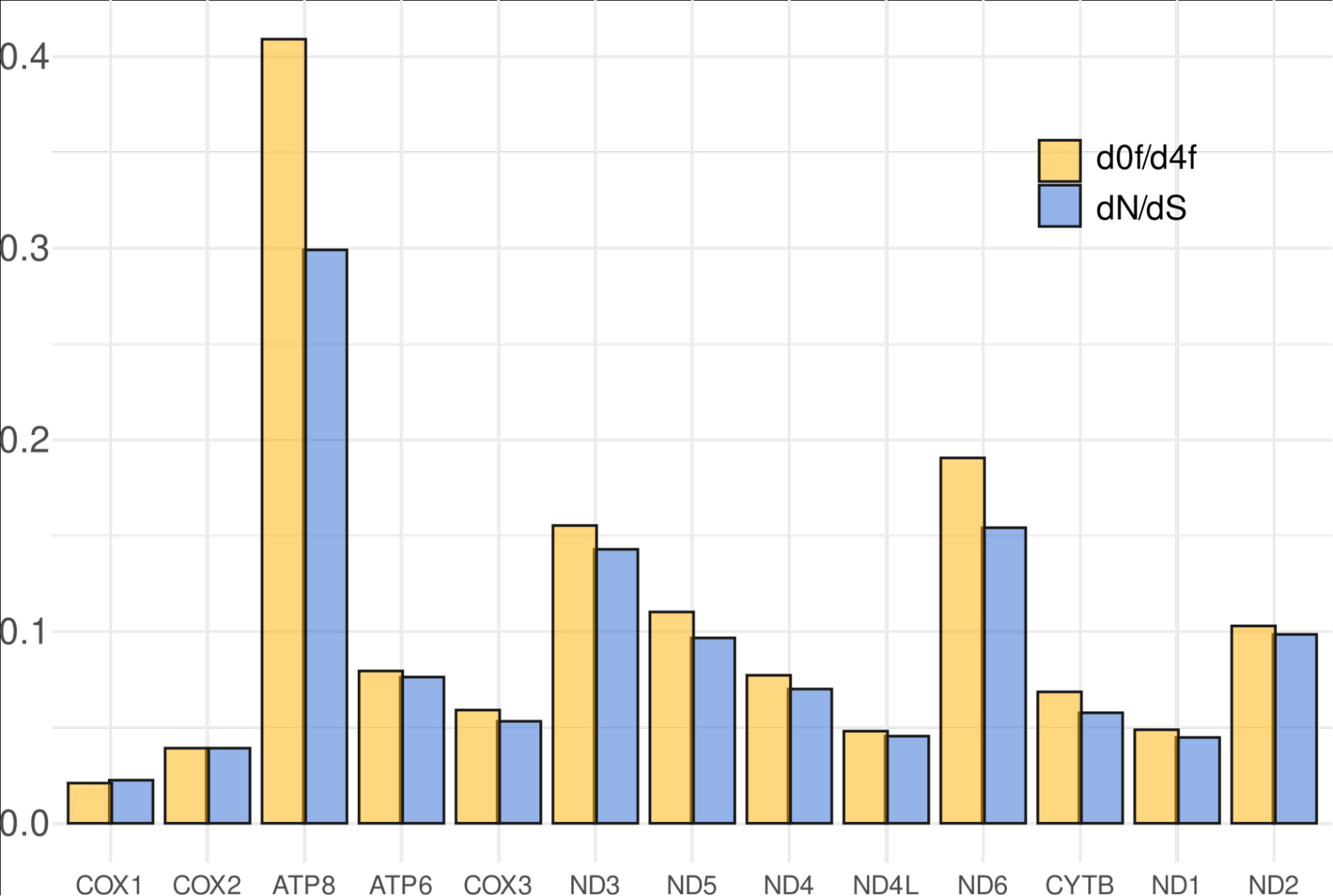

From the available set of total D.bispinis DNA, we chose one sample (ZMMU WS20509) and sequenced it using an Illumina platform. Sequencing enabled the assembly of the complete circular mitochondrial genome (Figure 2). The D. bispinis mitochondrial genome appeared to be 14,836 bp in length, had a 35% GC content, and contained all standard mitochondrial protein-coding genes (PCGs), tRNAs, and rRNAs. It also contained an AT-rich non-coding region upstream of the 12S rRNA gene. AT-richness, along with an absence of predicted open reading frames, suggests that this is the control region containing D-loop. We also sequenced, assembled, and annotated a 14,853 bp mitochondrial genome of another Dyopedos species, D. porrectus (Supplementary Data S2). Assembling the D. porrectus mitogenome allowed us to calculate dN/dS ratios for individual genes, estimating the relative strengths of purifying and positive selection effects acting after the divergence of these species. We also calculated the d0/d4F metric, which is the ratio of non-synonymous substitutions to substitutions in four-fold redundant positions, and provides greater sensitivity than dN/dS. These analyses revealed a typical metazoan pattern: a high conservation in COX1 and a relaxed selection on ATP8 and ND6 genes (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Differential purifying selection on protein-coding genes (PCGs) following the divergence of D. bispinis and D. porrectus. Two metrics are used to quantify selection pressure: dN/dS ratio: The ratio of non-synonymous substitutions (dN) to synonymous substitutions (dS) per site. d0f/d4f ratio: An alternative measure of selection pressure, calculated as the ratio of substitution rates at zero-fold redundant sites (d0f, non-synonymous) to four-fold degenerate sites (d4f, synonymous). Similar to dN/dS, lower values suggest stronger purifying selection.

The order of PCGs in D. bispinis (Figure 2A) and D. porrectus (Supplementary Data S2) did not differ from that of Gammarus duebeniLiljeborg, 1853, the closest species whose complete mitochondrial genome was available in genbank (Figure 2B). The available Gammarus mitogenomes exhibited conserved architectures, with the exception of Gammarus chevreuxiSexton, 1913 (Supplementary Data S3), and a duplicated control region seen in some species, such as Gammarus roeseliGervais, 1835 (Cormier et al., 2018). At the same time, the position and coding strands of some tRNAs differed between the Gammarus and Dyopedos species. In available Gammarus mitogenomes, tRNA-Pro was located upstream of the ND5 gene, whereas in both Dyopedos species it was between tRNA-Ser and the ND1 gene (Figure 2B). Furthermore, a cluster of five tRNAs flanked by the putative control region and the ND2 gene in Dyopedos species was inverted compared to that observed in Gammarus species (Figure 2B, Supplementary Data S3). This suggests that the divergence of Gammarus and Dyopedos led to an architectural reorganization of the mitogenome in one of the groups, resulting in the transposition of several tRNAs.

Then, to analyze the family structure of amphipods on the collective masts, we selected two masts with multiple adult females and two typical short masts (see the full list of individuals on the masts in the Supplementary Table S1). We extracted DNA from several adult individuals on these masts, as well as some immature amphipods. In some cases, we isolated embryos from the females and processed them as separate individuals or as groups of individuals. We performed PCR with the total DNA isolated from 59 samples off these four masts and sequenced LR-PCR products using next-generation sequencing. Given that not all PCRs yielded products, we took only partial genomes in further analysis, constituting roughly half of the entire mitogenome sequence. Figure 2 illustrates the region taken for analysis and the number of polymorphism found in all samples. Phylogenetic tree of several Dyopedos and Gammarus species, generated based on partial nucleotide sequences of the COX1 gene (Supplementary Data S5), shows that intraspecies polymorphism within samples identified as D. bisminis is significantly lower than interspecies divergency, confirming their belonging to the same species.

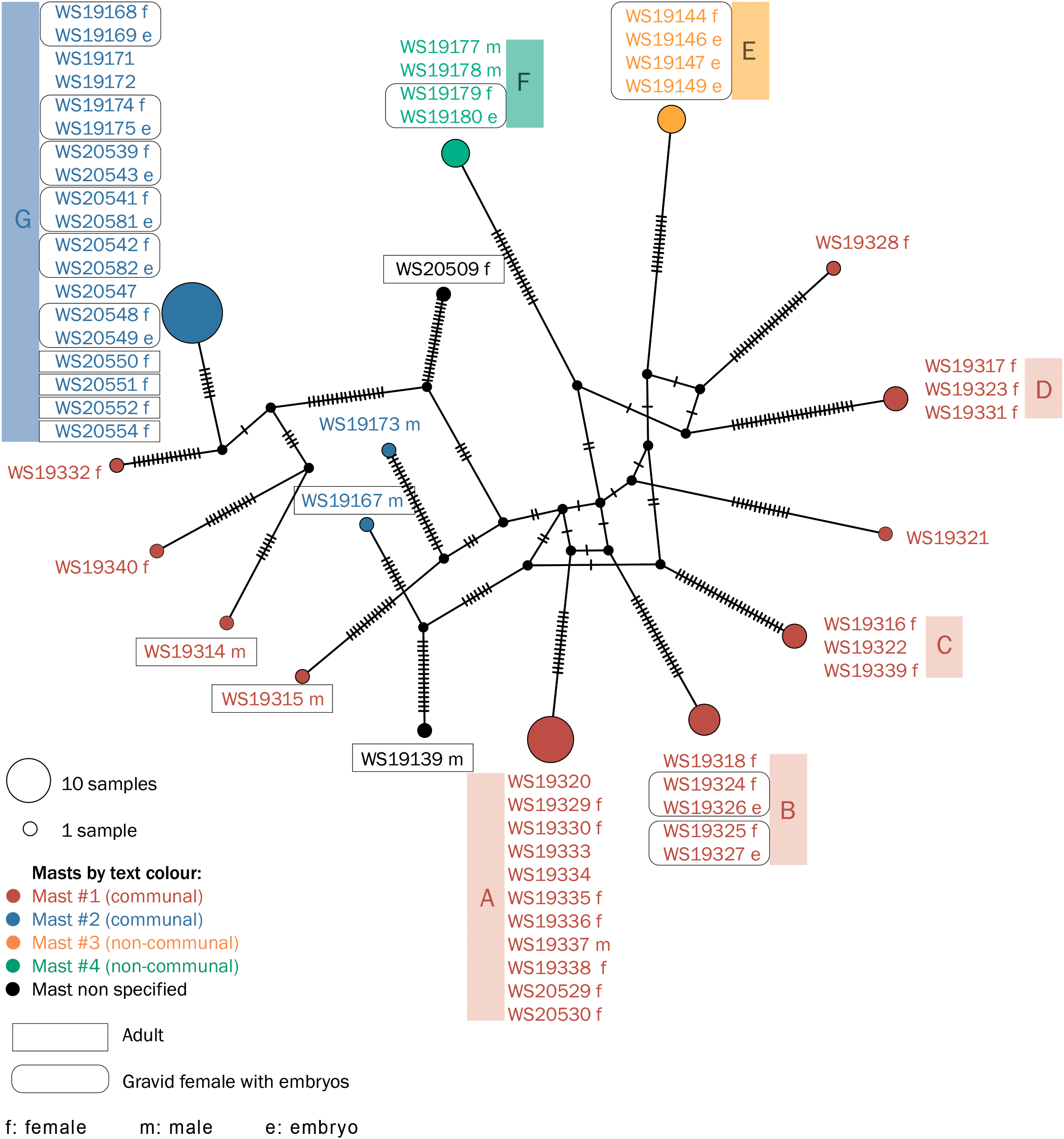

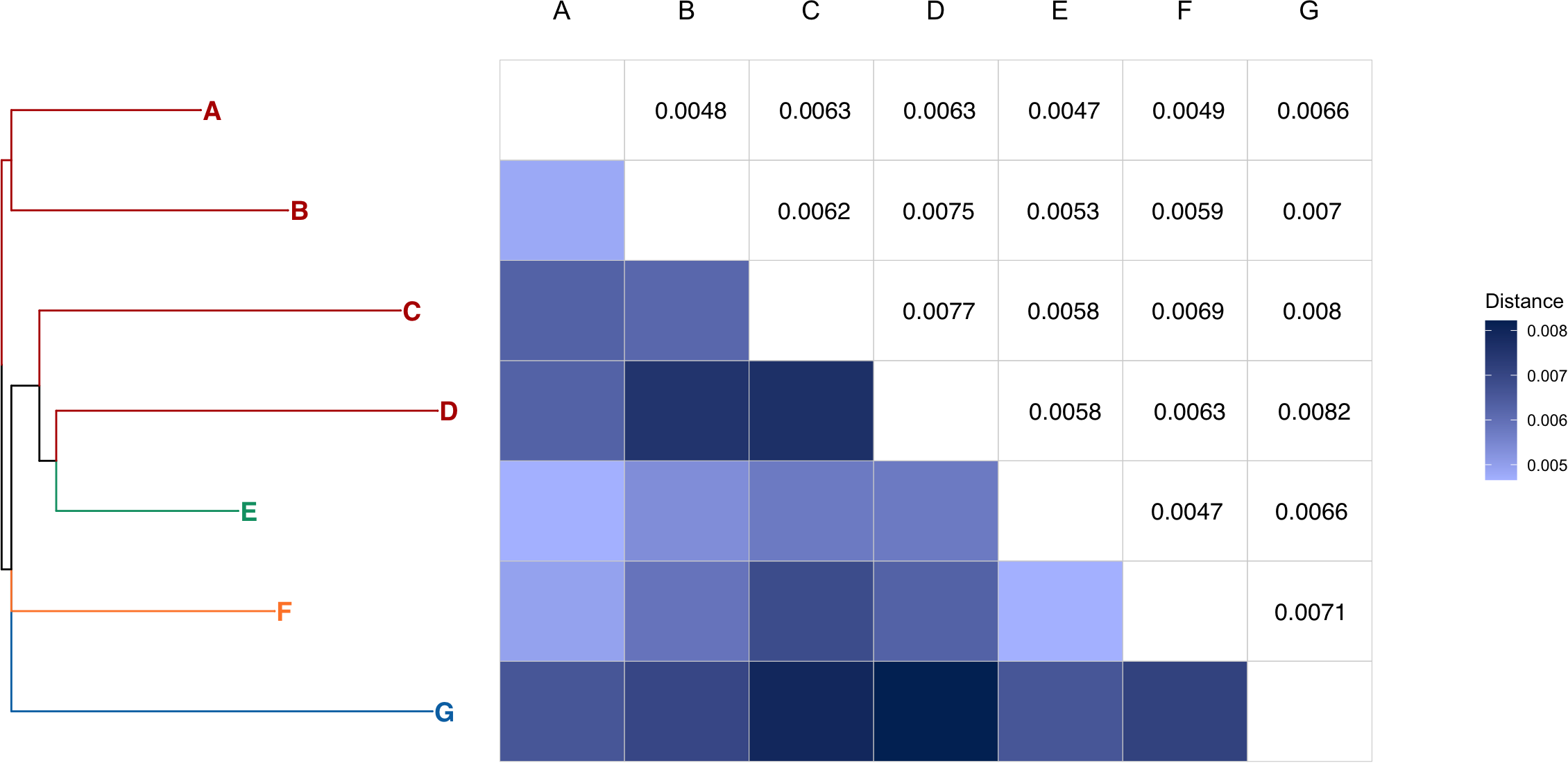

We generated a haplotype network based on 259 variable sites in mitochondrial genome regions with a total length of 7,299 b.p. among 59 individuals or groups of embryos from four collective masts (Figure 4, see alignment in Supplementary Data S4). As expected, the small masts contained either a female with three independently sequenced embryos (mast #3), or a female with embryos and two young male individuals with identical partial mitochondrial genome sequences (mast #4). Specimens from one of the collective masts (mast #2) also shared identical mitochondrial genome partial sequences, with the exception of the two males, adult (ZMMU WS19167) and subadult or adult (ZMMU WS19173). However, one analyzed collective mast (mast #1) contained several groups of female individuals with highly diverged mitochondrial genomes. Figure 4 shows a haplotype network with seven diverged clusters (groups of more than two individuals sharing the same genotype; clusters are named A–G) and branches representing subadult females, adult males, and gravid females with mitotypes distinct from those in the clusters. Figure 5 shows pairwise distances between four clusters from mast #1, as well as three clusters of samples from the remaining three masts. The mean pairwise distance between clusters was 0.63% (45.5 substitutions per 7,299 b.p., or 93.5 substitutions per genome); the mean pairwise distance between clades from mast #1 was 0.65%, 0.61% between clades from masts #2-4, and 0.63% between clades from mast #1 compared to clades from masts #2-4.

Figure 4

Kinship on four D.bispinis masts. Haplotype network is based on partial mitochondrial genomes of 59 individuals from four collective masts. Masts are indicated by text and circle color.

Figure 5

Pairwise distances (substitutions per b.p.) between seven D.bispinis clades, each with more than one sample (heatmap and values). Clades are named the same way as on Figure 4, and colored according to the mast they belong to. The tree on the left is reconstructed using the Maximum Likelihood approach in IQtree (v.2.4.0) with a model TIM+F+I (automatic standard model selection).

Given that mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the female parent, our results shown in Figure 4 suggest that multiple non-kin females inhabit mast #1, and that at least four of the families inhabited the mast long enough to have offspring on it. However, as mentioned in the introduction, there are reports of paternal leakage and unusual patterns of mtDNA inheritance among various invertebrate species. To account for this, we sequenced partial mitochondrial genomes of ten mother-embryo pairs; in all cases, the embryo contained exactly the same genome as the female parent (Figure 4). Therefore, it is unlikely that the difference between clades on mast #1 can be explained by frequent paternal inheritance of mtDNA in this species.

4 Discussion

Some animals can form societies where they share common resources and cooperate with each other. Cooperation is mainly driven by kin selection, though in some cases non-kin individuals or individuals of different species can establish evolutionarily stable cooperation (Clutton-Brock, 2009; Foster et al., 2006). The evolutionary forces shaping these societies, as well as the associated costs and benefits for their individual members, usually remain unclear because of their complexity. Therefore, animals with less complex forms of sociality can provide valuable insights into the development of more complex communities (Costa, 2018).

In this study, we reconstructed the family structures of the social amphipod D.bispinis collected from several masts including two collective masts that harbored several distinct assemblages of similar-sized individuals. On one of the masts (#2), despite the presence of multiple adult females, all the female crustaceans included in the analysis turned out to share an identical ~10 k.b. mitochondrial genome fragment (Figure 4). The presence of several adults, including pregnant females, on a mast suggests two non-mutually exclusive possibilities: (1) there are at least two generations on this mast, or (2) the pregnant females, with identical partial mitochondrial genomes, are sisters continuing to use their progenitor’s mast. At the same time, male D.bispinis are mobile and travel between masts (Neretin et al., 2017), so kinship is expected to be shared through the female line. Accordingly, male individuals from this mast contained another mitochondrial genotype and are therefore not descendants of the founding female (Figure 4).

Figure 4 shows that crustaceans from another collective mast (#1) were divided into several maternally non-kin groups (clades in which all individuals share the same genotype). These groups included (1) a group of one subadult female and two females with embryos, (2) three groups of subadult females, one of which also included small juveniles. The low level of kinship on mast #1 is a rather unexpected result because ordinary “family” masts are considered classic parent-offspring groups with strict territoriality (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989; Neretin et al., 2017; Thiel, 1997, 1998), so it seemed natural to expect a high degree of kinship on the more populated masts that developed from them.

Shared construction and usage by non-kin individuals may result from exploitation of a founding family by later-arriving families or non-kin cooperation. By cooperation here, we mean the investment of resources, not necessarily equally, by different individuals to create a common product—namely, building and/or maintaining a mast. Although we lack the data to quantify the costs of mast construction for each genetically distinct cohort, several arguments suggest the presence of non-kin cooperation in D. bispinis. Firstly, there is evidence of cooperative behavior on ordinary family masts among dulichiids amphipods, like Dyopedos monacanthus (Metzger, 1875) males participating in mast construction as temporary guests (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989). Secondly, we observed no differentiation in the shape and volume of the secretory apparatus among adult females inhabiting collective masts. This does not exclude the possibility of a division of labor or unequal investment in mast construction due to behavioral differences. Finally, in a minority of cases, the length of communal masts may significantly exceed the length of ordinary reproductive masts (those of females with offspring, Neretin et al., 2017). These reasonings and observations suggest that D. bispinis on collective masts may exhibit a primitive mode of cooperation, characterized by the joint construction and shared usage of the mast.

As per Hamilton’s rule, which states that the benefits of cooperative investment fade rapidly with increasing kinship distance, evolutionarily stable cooperation requires kinship (Hamilton, 1964). Uncommon exceptions to this rule occur when manipulation strategies provide individual benefits from cooperative behavior or when mechanisms ensure an immediate fitness advantage from cooperation (Clutton-Brock, 2009). However, Hymenoptera colonies often exhibit reduced relatedness within themselves due to (1) polypaternity (Delaplane et al., 2024; Duff et al., 2023), (2) colony co-founding by multiple distantly related females, and (3) acceptance of new non-sibling breeding females into the colony. The efficiency of such cooperation is likely ensured by immediate (direct) benefits for contributing participants (Ostwald et al., 2022). We suggest that all these mutually non-exclusive scenarios can contribute to the collective masts of D.bispinis.

How a mast with a non-kin population is formed remains unknown. The presence of groups of subadult siblings requires either the assumption of group migrations from other masts, or of their birth and growth on this mast. In the latter case, the formation of a communal structure on the mast should be attributed to the previous generation. Since aggression levels are lower in juveniles than in adults (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989), one might suppose that the non-kin structure of the mast initially forms due to independent arrivals of several juveniles on the mast. One of the family groups (group A) includes two age cohorts, which may signify that their mother spent some time on the mast.

Our data indicate that the masts of D. bispinis are utilized and possibly constructed or maintained by multiple individuals (Figure 4, Neretin et al., 2017). Regardless of the specific contributions by different individuals, these masts are utilized by all adult and immature inhabitants to enhance their foraging and protective capabilities. Such social constructions are common among insects (Costa, 2018; Schwarz et al., 2007; Wcislo et al., 2009). In contrast, shared construction usage among crustaceans is usually limited to parental-offspring groups (Thiel, 2003, 2011, Thiel, 2000a). Exceptions are some burrowing species, for example gnathid isopods and talitrid amphipods form small harem groups (Iyengar and Starks, 2008; Upton, 1987). There are also occasional reports of adults sharing a common burrow for semi-terrestrial crayfish (Norrocky, 1991; Richardson, 2007) and maerid amphipods (Atkinson et al., 1982), but data on these social systems are still very incomplete. However, more structured societies including harems, overlapping generations, and true eusociality, are found in symbiotic amphipods, isopods, shrimps (Duffy, 1996, 2007; Shuster and Wade, 1991; Thiel, 1999b, 2000b), and terrestrial crabs (Diesel and Schubart, 2007). Therefore, the case of the D. bispinis communal mast #1 (Figure 4) is rather exceptional, as it does not fall into either category.

The mechanisms enabling coexistence of non-kin D. bispinis on a shared mast while preventing it in other species remain unknown. Apparently, the high level of territorial aggression that is characteristic for family masts (Mattson and Cedhagen, 1989; Thiel, 1997; Neretin et al., 2017) is decreased on communal masts and at the very least does not lead to competitors being immediately driven away. A change in aggression level towards conspecifics, depending on a set of factors (reproductive state, colony welfare, environmental factors, and others), has been observed for some social insects (Reeve and Nonacs, 1997; Sturgis and Gordon, 2012). Territorial aggression in amphipods may be influenced by selectivity based on the intruder’s size or certain chemical cues. While crustaceans are known to use chemical signals for kin recognition, this occurs very rarely (Thiel, 2007; Beermann et al., 2015). The adoption of unrelated offspring, sometimes even from closely related species, is usually independent of chemical cues (Thiel, 2007). We suggest that D. bispinis communal masts are enabled by the low ‘cost’ of mast sharing due to the type of construction. Indeed, space deficit is not as pronounced on masts as in holes or tubes exploited by other crustaceans (see the discussion in Neretin et al., 2017; Thiel, 2007).

The mitochondrial genome of D. bispinis (Figure 2) did not contain any features uncommon in other crustaceans. The protein-coding genes (PCGs) were fairly conserved, and accumulated significantly more synonymous than non-synonymous mutations since their divergence from D. porrectus (Figure 3). The relaxed purifying selection on the ATP8 gene, which we detected (Figure 3), is a common feature of mitochondrial genomes in other arthropods (da Silva et al., 2020; Hao et al., 2017; Pons et al., 2014). Furthermore, the block of five tRNAs rearranged between Gammarus sp. and D. bispinis is adjusted to a putative control region. This observation is consistent with the idea that architectural mtDNA rearrangements typically involve or occur near the control region (Macey et al., 1997).

The numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the mitogenomes of D. bispinis collected from the same location, and even the same mast, suggest a high mutation rate and/or effective population size (Ne). Indeed, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is prone to mutations (Nabholz et al., 2008) but mtDNA mutation rates (μmito) in invertebrates are understudied, with a few exceptions in some model organisms (Allio et al., 2017; Haag-Liautard et al., 2008). Here, by sequencing mother-offspring pairs, we did not detect any de novo mutations and deviations from the strict maternal inheritance of the mitochondrial DNA. However, the data allows us to make a rough estimate of the lower limit of μmito for D. bispinis. Given that we sequenced approximately 7.3 kb of the mitogenome fragment from twelve embryos and found no differences from their mothers (Figure 4), we can infer that μmito is less than 1.1*10–6 substitutions per base pair per generation. It should be noted, however, that this estimate is significantly higher than the known mutation rate of the fruit fly, which is 6.2 × 10−8 per site per fly generation (Haag-Liautard et al., 2008). Therefore, the actual μmito of D. bispinis is likely to be several orders of magnitude lower than our estimate.

To summarize, the high level of intrapopulation genetic variability in mitochondrial genomes permits for the reliable tracing of maternal kinship within D. bispinis groups. Our study provides essential resources, including an assembled mitochondrial genome and a set of primers, to facilitate kinship investigations in D. bispinis. Utilizing these tools, we have demonstrated the possibility of this marine mast-building amphipod forming non-kin societies. D. bispinis represents an unusual case among marine crustaceans, showcasing the capacity of an amphipod to share a common resource with non-sibling individuals.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

NN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. AB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ME: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. GK: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. TP: Resources, Writing – original draft. AT: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TN: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Russian Science Foundation (project 21-74-20028-P).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the team of RV Professor Zenkevich (Yury Kozhuhov and Elsur Gabaidullin) and to the “Polydora” expedition members: Vitaly Syomin, Eugeniy Yakovis, Anna Artemieva, and Anna Sokolova. To Tatiana Y. Neretina for her help working with the collection material. To Anna Sokolova for translation proofreading.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1732471/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1Dataset with specimen location composition and complete list of mast inhabitant specimens.

Supplementary Table 2Primers used for Long Range PCR.

Supplementary Data Sheet 1Coordinates of the regions included in phylogenetic analysis.

Supplementary Data Sheet 2Mitochondrial genome map of Dyopedos porrectus.

Supplementary Data Sheet 3Architectures of the mitochondrial genomes of the Gammarus species available in genbank.

Supplementary Data Sheet 4Alignment.

Supplementary Data Sheet 5Phylogeny of Dyopedos bispinis, Dyopedos porrectus and several Gammarus species. Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree based on partial nucleotide sequences of the COX1 gene. The tree is rooted in the branch that separates Dyopedos and Gammarus clades. Bootstrap support values (%) are shown above branches.

References

1

Allio R. Donega S. Galtier N. Nabholz B. (2017). Large variation in the ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear mutation rate across animals: implications for genetic diversity and the use of mitochondrial DNA as a molecular marker. Mol. Biol. Evol.34, 2762–2772. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx197

2

Ariyama H. Hoshino O. (2019). A new superfamily, family, genus and species of marine amphipod, Protodulichia scandens, from Japan (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Senticaudata: Corophiida). J. Natural History53, 2467–2477. doi: 10.1080/00222933.2019.1704588

3

Ashrafi H. Hultgren K. M. (2023). Eusociality unveiled: discovery and documentation of two new eusocial shrimp species (Caridea: Alpheidae) from the Western Indian Ocean. Arthropod Systematics Phylogeny81, 1103–1120. doi: 10.3897/asp.81.e111799

4

Atkinson R. J. Eastman L. B. (2015). “ Burrow dwelling in crustacea,” in The Natural History of the Crustacea, vol. 2. Eds. ThielM.WatlingL. (New York: Oxford University Press), 78–117.

5

Atkinson R. J. A. Moore P. G. Morgan P. J. (1982). The burrows and burrowing behaviour of Maera loveni (Crustacea: Amphipoda). J. Zoology198, 399–416. doi: 10.1111/jzo.1982.198.4.399

6

Bankevich A. Nurk S. Antipov D. Gurevich A. A. Dvorkin M. Kulikov A. S. et al . (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol.19, 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.002

7

Bate C. S. (1857). A synopsis of the British edriophthalmous Crustacea. Part I. Amphipoda. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History19, 135–152. London: Taylor and Francis.

8

Beermann J. Dick J. T. A. Thiel M. (2015). “ Social recognition in amphipods: an overview,” in Social recognition in Invertebrates: the Knowns and the Unknowns. Eds. AquiloniL.TricaricoE. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17599-7_6

9

Bernt M. Donath A. Jühling F. Externbrink F. Florentz C. Fritzsch G. et al . (2013). MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.69, 313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023

10

Birky C. W. Jr. (2008). Uniparental inheritance of organelle genes. Curr. Biology: CB18, R692–R695. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.049

11

Bolger A. M. Lohse M. Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

12

Borowsky B. (1983). Reproductive behavior of three tube-building peracarid crustaceans: the amphipods Jassa falcata and Ampithoe valida and the tanaid Tanais cavolinii. Mar. Biol.77, 257–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00395814

13

Breton S. Beaupré H. D. Stewart D. T. Hoeh W. R. Blier P. U. (2007). The unusual system of doubly uniparental inheritance of mtDNA: isn’t one enough? Trends Genetics: TIG23, 465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.011

14

Clement M. Snell Q. Walke P. Posada D. Crandall K. (2002). “ TCS: estimating gene genealogies,” in Parallel and distributed processing symposium, international, vol. 2. (Los Alamitos, California: IEEE Computer Society), 7. doi: 10.1109/IPDPS.2002.1016585

15

Clutton-Brock T. (2009). Cooperation between non-kin in animal societies. Nature462, 51–57. doi: 10.1038/nature08366

16

Clutton-Brock T. (2021). Social evolution in mammals. Science373, eabc9699. doi: 10.1126/science.abc9699

17

Corbari L. Sorbe J.-C. (2018). First observations of the behaviour of the deep-sea amphipod Dulichiopsis dianae sp. nov. (Senticaudata, Dulichiidae) in the TAG hydrothermal vent field (Mid-Atlantic Ridge). Mar. Biodiversity48, 631–645. doi: 10.1007/s12526-017-0788-y

18

Cormier A. Wattier R. Teixeira M. Rigaud T. Cordaux R. (2018). The complete mitochondrial genome of Gammarus roeselii (Crustacea, Amphipoda): insights into mitogenome plasticity and evolution. Hydrobiologia825, 197–210. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3578-z

19

Costa J. T. (2018). The other insect societies: overview and new directions. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 28, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2018.04.008

20

Danecek P. Bonfield J. K. Liddle J. Marshall J. Ohan V. Pollard M. O. et al . (2021). Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience10, 1–4. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008

21

da Silva J. (2021). Life history and the transitions to eusociality in the Hymenoptera. Front. Ecol. Evol.9. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.727124

22

da Silva F. S. Cruz A. C. R. de Almeida Medeiros D. B. da Silva S. P. Nunes M. R. T. Martins L. C. et al . (2020). Mitochondrial genome sequencing and phylogeny of Haemagogus albomaculatus, Haemagogus leucocelaenus, Haemagogus spegazzinii, and Haemagogus tropicalis (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep.10, 16948. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73790-x

23

Delaplane K. Hagan K. Vogel K. Bartlett L. (2024). Mechanisms for polyandry evolution in a complex social bee. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiology78, 39. doi: 10.1007/s00265-024-03450-x

24

Diesel R. Schubart C. D. (2007). “ The social breeding system of the Jamaican bromeliad crab Metopaulias depressus,” in Evolutionary Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems ( Oxford University Press, New York), 365–386. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179927.003.0017

25

Duff L. B. Proulx A. N. M. Corbin L. A.-J. Richards M. H. (2023). Evidence for multiple mating by female eastern carpenter bees, Xylocopa virginica (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Can. Entomologist155, e10. doi: 10.4039/tce.2022.51

26

Duffy J. E. (1996). Eusociality in a coral-reef shrimp. Nature381, 512–514. doi: 10.1038/381512a0

27

Duffy J. E. (2007). “ Ecology and evolution of eusociality in sponge-dwelling shrimp,” in Evolutionary Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems: Crustaceans as Model Organisms. Eds. Emmett DuffyJ.ThielM. (New York: Oxford Academic). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179927.003.0018

28

Duffy J. E. Morrison C. L. Ríos R. (2000). Multiple origins of eusociality among sponge-dwelling shrimps (Synalpheus). Evolution; Int. J. Organic Evol.54, 503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00053.x

29

Duffy J. E. Thiel M. (2007). Evolutionary ecology of social and sexual systems: crustaceans as model organisms. Eds. DuffyJ. E.ThielM. (New York: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179927.001.0001

30

Elgar M. A. (2015). Integrating insights across diverse taxa: challenges for understanding social evolution. Front. Ecol. Evol.3. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2015.00124

31

Foster K. R. Wenseleers T. Ratnieks F. L. W. (2006). Kin selection is the key to altruism. Trends Ecol. Evol.21, 57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.11.020

32

Gervais M. (1835). Note sur deux espèces de crevettes qui vivent aux environs de Paris. Annales des Sciences Naturelles (Zoologie)4, 127–128.

33

Gurjanova E. . (1930). Beiträge zur Fauna der Crustacea-Malacostraca des arktischen Gebietes. Zoologischer Anzeiger86, 231–248.

34

Gurjanova E. F. (1951). “ Amphipoda-Gammaridea of the sea of the USSR and adjoining waters,” in Keys to the Fauna of the USSR, vol. 4. (Leningrad, USSR: Zool. Inst. Acad. Sci. USSR), 1–1029.

35

Haag-Liautard C. Coffey N. Houle D. Lynch M. Charlesworth B. Keightley P. D. (2008). Direct estimation of the mitochondrial DNA mutation rate in Drosophila melanogaster. PloS Biol.6, e204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060204

36

Hamilton W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J. Theor. Biol.7, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4

37

Hao Y.-J. Zou Y.-L. Ding Y.-R. Xu W.-Y. Yan Z.-T. Li X.-D. et al . (2017). Complete mitochondrial genomes of Anopheles stephensi and An. dirus and comparative evolutionary mitochondriomics of 50 mosquitoes. Sci. Rep.7, 7666. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07977-0

38

Hoang D. T. Chernomor O. Von Haeseler A. Minh B. Q. Vinh L. S. (2018). UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281

39

Iyengar V. K. Starks B. D. (2008). Sexual selection in harems: male competition plays a larger role than female choice in an amphipod. Behav. Ecol.19, 642–649. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arn009

40

Kalyaanamoorthy S. Minh B. Q. Wong T. K. Von Haeseler A. Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods14, 587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285

41

Langmead B. Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods9, 357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923

42

Laubitz D. R. (1977). A revision of the genera Dulichia Krøyer and Paradulichia Boeck (Amphipoda, Podoceridae). Can. J. Zoology55, 942–982. doi: 10.1139/z77-123

43

Lavrov D. V. Pett W. (2016). Animal mitochondrial DNA as we do not know it: mt-genome organization and evolution in nonbilaterian lineages. Genome Biol. Evol.8, 2896–2913. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw195

44

Lee J. Willett C. S. (2022). Frequent paternal mitochondrial inheritance and rapid haplotype frequency shifts in copepod hybrids. J. Heredity113, 171–183. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esab068

45

Leigh J. W. Bryant D. Nakagawa S. (2015). POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol.6, 1110–1116. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12410

46

Liljeborg W. (1853). Hafs-Crustaceer vid Kullaberg. Öfversigt af Kongliga Vetenskaps-Akademiens Förhandlingar9, 1–13. Norstedt: Stockholm.

47

Macey J. R. Larson A. Ananjeva N. B. Fang Z. Papenfuss T. J. (1997). Two novel gene orders and the role of light-strand replication in rearrangement of the vertebrate mitochondrial genome. Mol. Biol. Evol.14, 91–104. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025706

48

Mattson S. Cedhagen T. (1989). Aspects of the behaviour and ecology of Dyopedos monacanthus (Metzger) and D. porrectus Bate, with comparative notes on Dulichia tuberculata Boeck (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Podoceridae). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.127, 253–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(89)90078-6

49

Minh B. Q. Schmidt H. A. Chernomor O. Schrempf D. Woodhams M. D. Von Haeseler A. et al . (2020). IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol.37, 1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015

50

Moore P. G. Eastman L. B. (2015). “ The tube-dwelling lifestyle in crustaceans and its relation to feeding,” in The natural history of the Crustacea, vol. 2 . Eds. ThielM.WatlingL. (New York: Oxford University Press), 35–77.

51

Nabholz B. Glémin S. Galtier N. (2008). Strong variations of mitochondrial mutation rate across mammals--the longevity hypothesis. Mol. Biol. Evol.25, 120–130. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn033

52

Najer T. Doña J. Buček A. Sweet A. D. Sychra O. Johnson K. P. (2024). Mitochondrial genome fragmentation is correlated with increased rates of molecular evolution. PloS Genet.20, e1011266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1011266

53

Neretin N. Y. Zhadan A. E. Tzetlin A. B. (2017). Aspects of mast building and the fine structure of “amphipod silk” glands in Dyopedos bispinis (Amphipoda, Dulichiidae). Contributions to Zoology86, 145–168. doi: 10.1163/18759866-08602003

54

Norrocky M. J. (1991). Observations on the ecology, reproduction and growth of the burrowing crayfish Fallicambarus (Creaserinus) fodiens (Decapoda: Cambaridae) in North-central Ohio. Am. Midland Nat.125, 75–86. doi: 10.2307/2426371

55

Ostwald M. M. Haney B. R. Fewell J. H. (2022). Ecological drivers of non-kin cooperation in the Hymenoptera. Front. Ecol. Evol.10. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.768392

56

Palaoro A. Thiel M. (2020). The caring crustacean: An overview of crustacean parental care. In CothranR.ThielM. (eds), Reproductive biology: The natural history of the Crustacea6 (115–144). New York: Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190688554.003.0005

57

Pons J. Bauzà-Ribot M. M. Jaume D. Juan C. (2014). Next-generation sequencing, phylogenetic signal and comparative mitogenomic analyses in Metacrangonyctidae (Amphipoda: Crustacea). BMC Genomics15, 566. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-566

58

Reeve H. K. Nonacs P. (1997). Within-group aggression and the value of group members: theory and a field test with social wasps. Behav. Ecol.8, 75–82. doi: 10.1093/beheco/8.1.75

59

Richardson A. M. M. (2007). “ Behavioral ecology of semiterrestrial crayfish,” in Evolutionary Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems ( Oxford University Press, New York), 319–338. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179927.003.0015

60

Ritter C. J. Bourne D. G. (2024). Marine amphipods as integral members of global ocean ecosystems. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.572, 151985. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2023.151985

61

Schwarz M. P. Richards M. H. Danforth B. N. (2007). Changing paradigms in insect social evolution: insights from halictine and allodapine bees. Annu. Rev. Entomology52, 127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.150950

62

Sexton E. W. (1913). Description of a new species of brackish-water Gammarus (G. chevreuxi, n. sp.). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom9, 542. doi: 10.1017/s0025315400071551

63

Shuster S. M. Wade M. J. (1991). Equal mating success among male reproductive strategies in a marine isopod. Nature. 350, 608–610. doi: 10.1038/350608a0

64

Sturgis S. J. Gordon D. M. (2012). Nestmate recognition in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): a review. Myrmecological News16, 101–110.

65

Thiel M. (1997). Reproductive biology of an epibenthic amphipod (Dyopedos monacanthus) with extended parental care. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom77, 1059–1072. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400038625

66

Thiel M. (1998). Population biology of Dyopedos monacanthus (Crustacea: Amphipoda) on estuarine soft-bottoms: importance of extended parental care and pelagic movements. Mar. Biol.132, 209–221. doi: 10.1007/s002270050387

67

Thiel M. (1999a). Extended parental care in marine amphipods: II. Maternal protection of juveniles from predation. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology234, 235–253. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400038625

68

Thiel M. (1999b). Host-use and population demographics of the ascidian-dwelling amphipod Leucothoe spinicarpa: indication for extended parental care and advanced social behaviour. J. Natural History33, 193–206. doi: 10.1080/002229399300371

69

Thiel M. (2000a). Extended parental care behaviour in crustacean - A comparative overview. The Biodiversity Crisis and Crustacea. Proceedings of the Fourth International Crustacean Congress, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 20-24 July 1998, Volume 2. Crustacean Issues 12, A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam. 211–226.

70

Thiel M. (2000b). Population and reproductive biology of two sibling amphipod species from ascidians and sponges. Mar. Biol.137, 661–674. doi: 10.1007/s002270000372

71

Thiel M. (2003). Extended parental care in crustaceans: an update. Rev. Chil. Hist. Natural76, 205–218. doi: 10.4067/s0716-078x2003000200007

72

Thiel M. (2007). “ Social behavior of parent–offspring groups in crustaceans,” in Evolutionary Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems ( Oxford University Press, New York), 294–318. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179927.003.0014

73

Thiel M. (2011). “ The evolution of sociality: peracarid crustaceans as model organisms,” in New Frontiers in Crustacean Biology (Leiden & Boston: Brill), 285–297. doi: 10.1163/ej.9789004174252.i-354.190

74

Upton N. P. D. (1987). Asynchronous male and female life cycles in the sexually dimorphic, harem-forming isopod Paragnathia formica (Crustacea: Isopoda). J. Zoology212, 677–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb05964.x

75

Wcislo W. T. Tierney S. M. Wilson E. O. (2009). “ The Evolution of Communal Behavior in Bees and Wasps: An Alternative to Eusociality”, in Organization of Insect Societies: From Genome to Sociocomplexity. Eds. GadauJ.FewellJ. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press), 148–170. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv228vr0t.11

76

Williams B. D. Schrank B. Huynh C. Shownkeen R. Waterston R. H. (1992). A genetic mapping system in Caenorhabditis elegans based on polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. Genetics131, 609–624. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.609

77

Yakovis E. Artemieva A. (2015). Bored to death: community-wide effect of predation on a foundation species in a low-disturbance Arctic subtidal system. PloS One10, e0132973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132973

Summary

Keywords

Amphipoda, dulichiid masts, extended parental care, mitochondrial genomes, non-kin societies, sociobiology

Citation

Neretin NY, Bezmenova AV, Ezhova MA, Kolbasova GD, Petrushkova TI, Tzetlin AB, Knorre DA and Neretina TV (2026) Family estates or dormitories: analyzing the kinship of Dyopedos bispinis “collective” mast populations (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Dulichiidae). Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1732471. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1732471

Received

25 October 2025

Revised

06 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

27 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Nicola Pugliese, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Reviewed by

Yanjie Zhang, Hainan University, China

Ioannis A Giantsis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Neretin, Bezmenova, Ezhova, Kolbasova, Petrushkova, Tzetlin, Knorre and Neretina.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dmitry A. Knorre, knorre@belozersky.msu.ru; Tatiana V. Neretina, nertata@wsbs-msu.ru

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.