Abstract

Plastic waste accumulates in coastal environments, posing risks to marine organisms and the human communities that depend on them. Fiji relies heavily on inshore fisheries, yet the extent and physiological implications of microplastic (MP) contamination in locally captured species remain unclear. Most existing work has focused on MP contamination in teleosts, with little information for batoids, particularly from South Pacific islands. In Fiji, batoids are a common component in small-scale fishery activities, with the endemic Fiji maskray (Neotrygon romeoi) frequently captured and traded. To provide a first reference for a batoid from this region, we quantified MP contamination in 21 Fiji maskrays from the Suva–Rewa–Tailevu corridor, characterized particles by size, shape, and color, and assessed physiological condition using the hepatosomatic index (HSI). Furthermore, to address a key life history gap relevant to management, we estimated size at maturity for both sexes, finding that females matured at 360–365 mm disc width and males at 369–395 mm disc width. Microplastics occurred in 71.4% of specimens, with a mean of 6.76 ± 7.80 particles per individual and no significant difference between stomach and intestine (p = 0.331). Particle sizes ranged from 63 to 500 µm, with 63 µm being the most frequent. Fragments predominated, with white (n = 38) and silver (n = 33) being the most common. No statistically significant relationship was found between MP presence and HSI, despite a weak to moderate negative trend. Together, these results establish a baseline for MP contamination and provide complementary life history information to support future contamination assessments and fisheries management.

1 Introduction

Plastic waste accumulates in coastal areas due to tidal flow and gyre currents (Chassignet et al., 2021). Plastics < 5mm are defined as microplastics (MP), and classified as primary, intentionally manufactured small particles, or secondary, derived from the breakdown of larger plastics (GESAMP, 2016). Coastal areas often show higher MP concentrations than offshore zones due to their proximity to human activities and land-based debris sources (Cordova et al., 2019). Fiji, located in the South Pacific Ocean, has a coastline of around 1,129 km (Central Intelligence Agency, 2025), and approximately half of its almost 900,000 inhabitants live in urban areas, predominantly along the coasts (Fiji Bureau of Statistics, 2024). Microplastic levels in Fiji’s urban and rural subsurface coastal waters are comparable, suggesting that pollution sources are diffuse rather than localized (Dehm et al., 2020). Although coastal ecosystems are critical for livelihoods, especially through small-scale inshore fisheries (Andradi-Brown et al., 2022), the scale and type of MP contamination in locally captured marine resources are not well understood. For example, arc clams (Anadara spp.) collected in tidal flats around the capital Suva showed a 24% increase in MP contamination between 1980 and 2023 (Powell et al., 2025). Similarly, MPs were found in 81.8% of sediment samples and 67.5% of teleosts from the same area of Southeast Viti Levu (Ferreira et al., 2020).

In teleosts, MP contamination is associated with negative physiological effects, as plastics can accumulate in tissues such as liver, muscle, and brain, leading to toxicity (Parker et al., 2021; Ammar et al., 2022). This toxicity is enhanced by the ability of plastics to adsorb other contaminants, including persistent organic pollutants (Kinigopoulou et al., 2022), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, insecticides, antibiotics, and heavy metals (José and Jordao, 2020; Sun et al., 2022; Huvet et al., 2025). The hepatosomatic index (HSI), the ratio of liver weight to total body weight, is widely used in teleosts to quantify nutritional status and metabolic investment, and is also relevant in elasmobranchs, where the liver is the main organ for lipid storage and detoxification (Reis and Figueira, 2020). Assessing HSI alongside MP contamination can help understand, whether exposure relates to energy reserves, physiological or environmental condition. However, most related work has focused on teleosts, with limited data for elasmobranchs, particularly for batoids (rays and skates) (Ebert and Cowley, 2009; Alkusairy et al., 2014; Marcon et al., 2021; Montero-Hernández et al., 2024). Overall, MP distribution across organs, particle types, and HSI-based condition in batoids remains poorly understood. To date, MP contamination has been examined in only 12 batoid species globally, with studies on coastal rays in the South Pacific being particularly scarce (Gong et al., 2024).

In Fiji, batoids are a common but little-explored component of small-scale fishery activities. At least 19 species occur in Fijian waters (Glaus et al., 2024b), including the endemic Fiji maskray (Neotrygon romeoi; Glaus et al., 2025). The widespread Fiji maskray reaches approximately 400 mm disc width (DW) (Glaus et al., 2024a). The species inhabits sandy bottoms, seagrass beds, and coral reefs (Glaus et al., 2025). It is also the most frequently captured and traded batoid in Fiji (Glaus et al., 2024c). To date, MP contamination has not been quantified for the Fiji maskray. Establishing this baseline is needed to evaluate links to physiological condition and potential MP sources. We therefore aim to (1) quantify MP contamination and compare distributions between stomach and intestine; (2) characterize particle size, shape, and color; and (3) assess physiological condition using the HSI. Additionally, we estimate size at maturity for both sexes. This life history information complements the MP baseline and supports fisheries and ecosystem management of this widely fished endemic species.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Site description and specimen acquisition

The Suva–Rewa–Tailevu corridor (Supplementary Figure S1), on the southeast coast of Fiji’s main island Viti Levu (approx. 18°S, 178°E), is home to more than 250,000 people (Wilson, 2012; Fiji Bureau of Statistics, 2017). The area combines dense urban settlement with intensive agriculture, insufficient waste management, and complex coastal processes increasing the susceptibility to MP accumulation (Drova et al., 2025). The adjacent Rewa River and Delta contain essential elasmobranch habitats (Brown et al., 2016; Glaus et al., 2019). Fishers from this region regularly bring their catch to the municipal market in Suva, particularly on Saturdays, which marks the main market day in Fiji (Glaus et al., 2024c). Twenty-two Fiji maskray specimens were purchased from a known local small-scale fisher between April 2024 and March 2025. The study objectives were explained to the fisher, and verbal consent for the use of specimens in University of the South Pacific (USP) research was obtained. Rays were reportedly caught opportunistically during nearshore gillnet fishing; no Fiji maskrays were caught specifically for this study. Captures occurred between Nausori and the Rewa Delta, but GPS positions and exact catch sites were not disclosed. Specimens were immediately transported to the USP Laucala Campus, and stored at −18 °C until processing.

2.2 Morphometrics, dissection, and organ digestion

Specimens were defrosted for approximately 20 h prior to measurements and dissection, rinsed with distilled water and dried. Specimens were weighed on an Ohaus Adventurer AX Precision Balance (model AX8201/E) to the nearest 0.01 g. Weight measurements included the head, trunk, pectoral, and pelvic fins, as tails had been cut off after capture to prevent injuries. Disc width in mm was measured on the dorsal side along the horizontal axis using a fish measuring board. Specimens were placed on a dissection tray, and a mid-ventral incision from the cloaca to the gill region was made with a sterile scalpel and forceps. To quantify MP contamination and compare presence between organs, the stomach and intestine were extracted. The liver was blotted dry with tissue paper and weighed to calculate the HSI. Liver color was recorded as a visual descriptor indicative for cell mutation (Agius, 1980; Neyrão et al., 2019), and classified as dark brown (DB) or light brown (LB). Stomach and intestine of each specimen were wrapped separately in aluminum foil, labeled, and stored at −18 °C until digestion. For digestion, stomach and intestine were processed separately. Each organ was placed into a labeled 600 mL glass beaker. A 10% Potassium Hydroxide, KOH, solution (volume ≥ 3× tissue volume) was added to dissolve soft tissue and food residues. Beakers were covered with aluminum foil and incubated at 60 °C for 48 h, with manual shaking after 24 h to ensure complete digestion (Amini-Birami et al., 2023). Digested material was then placed in a fume hood until further analysis.

2.3 Microplastic isolation and identification

Digested material from each specimen and organ was filtered through a sieve stack (500, 250, 125, and 63 µm) and allowed to settle for at least 3 min. To avoid MP cross-contamination, we followed procedures described in Pasalari et al. (2025); Trindade et al. (2023). Retained material was examined for MPs under an AmScope Stereo Microscope (SE306R-AZ-E1), using 2× magnification for 500 µm and 250 µm fractions and 4× for 125 µm and 63 µm fractions. For each observed MP particle, shape (fragment, fiber, film, foam, or microbead), sieve fraction, color, and the associated specimen ID were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet to ensure traceability. Microplastics were photographed using a Nikon Z8 with a 100mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens.

2.4 Size at maturity

Sex was determined by the presence of claspers (males, M) or their absence (females, F), which are visible from early development along the inner margin of the pelvic fins (Allen and Robertson, 1994). Immature males have flexible claspers with little or no calcification, whereas mature males exhibit elongated, rigid, and fully calcified claspers (Stevens and McLoughlin, 1991). Hence, the maturity of male Fiji maskrays was determined by taking measurements of the clasper size post cloaca and clasper from the pelvic axis and determining its calcification (Campbell et al., 2021). In female specimens, maturity was assessed visually based on ovarian and uterine development (Pierce et al., 2009). The uterus is presented as a pair of thin, tubular extensions leading from the cloaca, while the ovaries were bilobed and located dorsally. We determined the following maturity categories: (1) Juvenile: little or no ovarian development and/or thin strap-like left uterus, (2) Subadult: differentiated and non vitellogenic follicles and/or partially expanded left uterus, (3) Mature: vitellogenic follicles of >1mm present in the ovary, left oviductal gland clearly differentiated from the ovary & uterus, and/or left uterus >10mm maximum width and trophonemata present. Juveniles and subadults were classified as immature.

2.5 Data analysis

The Excel data sheet (Davuke et al., 2025) was loaded into R Studio (R Core Team, 2025) with the readxl package (Wickham and Bryan, 2015). To clean the data, dplyr package was used (Wickham et al., 2014b). Additionally, tidyr allowed converting between long and wide data formats, and handled missing data values, which were earlier noted as “NA” (Wickham et al., 2014a). Microplastic contamination was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Specimens without MP were excluded from downstream analyses of MP characteristics (size, shape, color) distribution across organs (organs = stomach and intestine) or sexes. To test for differences in MP counts and MP characteristics among organs and between sexes, we fitted multifactor ANOVA models to log-transformed response variables. Model assumptions (normality and homoscedasticity) were evaluated using residual diagnostic plots. To complement the univariate analyses, we assessed multivariate differences in MP characteristic composition among organs using the R packages vegan (Oksanen et al., 2025) and cluster (Maechler et al., 2025).

To understand the physiological state and energy reserves, the HSI was calculated using the formula . Since the measured weight excluded the tail (WT), we calculated two HSIs. First, HSI was computed using WT. Second, HSI was computed using an estimated total body weight. Total body weight (TW) was approximated by adding 2-5% percent to WT and averaging these four values to obtain the total-weight average (TWA) (e.g.

. Differences in HSI between liver color groups were assessed with a One Way ANOVA. To analyze an association between liver color and sex, maturity, or size (DW), irrespective of MP contamination, we used a binomial generalized linear model (GLM) with the car package (Fox and Weisberg, 2019). Spearman rank correlations tested associations between HSI or DW and MP count. Size at maturity was summarized in sex-specific boxplots.

Figures were generated in R with qqplot2 (Wickham, 2016), Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Inc, 2023), and QGIS (QGIS Development Team, 2025).

3 Results

Of 22 Fiji maskray specimens collected, three were excluded due to measurement uncertainties: one from all analyses (TV_Neotrygon_sp19), and additionally one from HSI analysis (TV_Neotrygon_sp8), and one from size-at-maturity assessments (TV_Neotrygon_sp5).

3.1 Microplastic presence & distribution across stomach and intestine

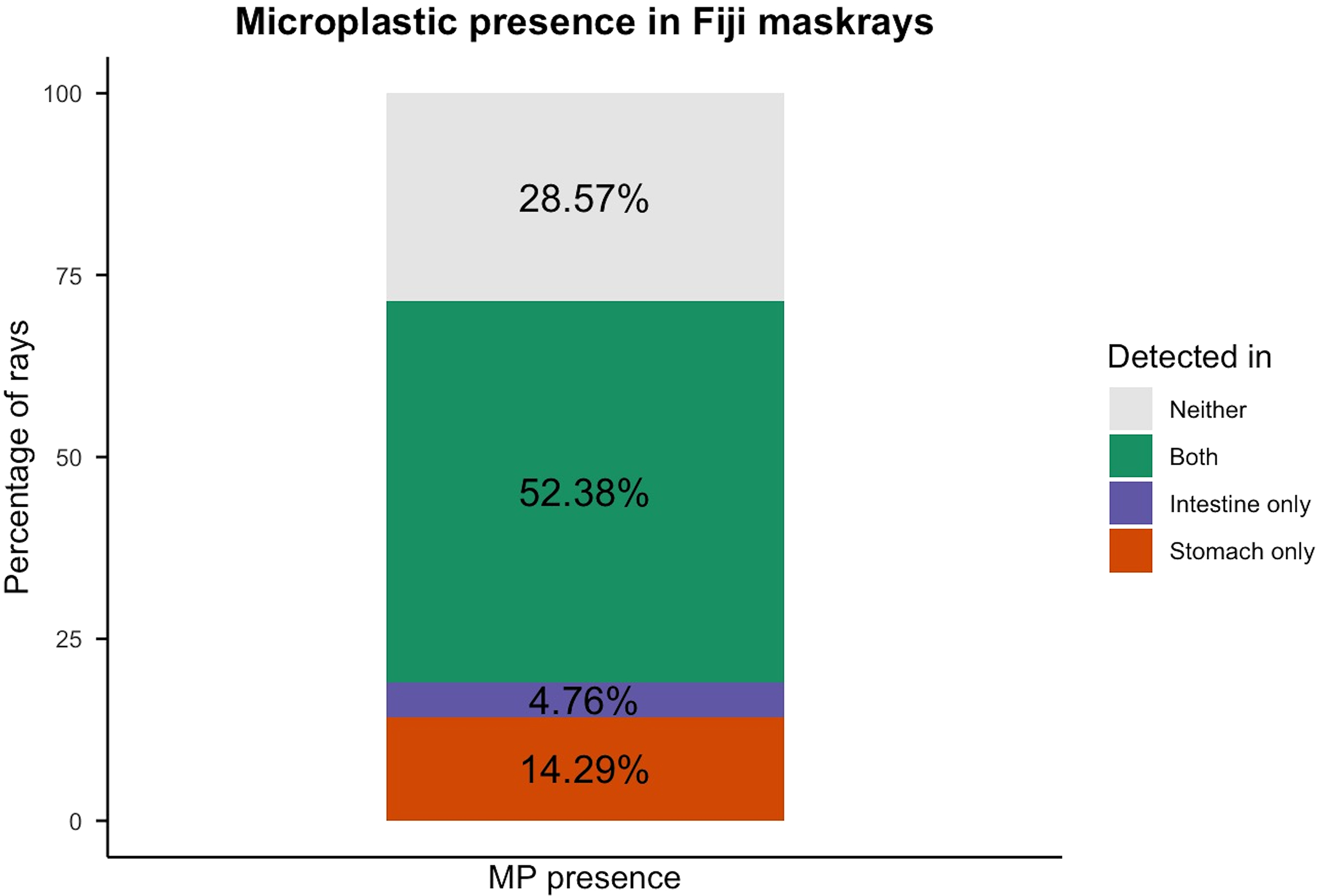

Of 21 Fiji maskrays, MPs were detected in 15 individuals (~71.4%): in the stomach in three (~14.3%), the intestine only in one (~4.8%), and both organs in 11 (~52.4%). Six (~28.6%) had no MPs. Among individuals, the mean was 6.76 ± 7.80 particles per specimen. Particle counts did not differ between organs or sexes (p = 0.331, p = 0.222; Figure 1).

Figure 1

MP presence in the gastrointestinal tract (stomach and intestine) of 21 investigated Fiji maskray specimens.

Microplastic sizes ranged from 63 to 500 µm in both stomach and intestine. Particles of 63 µm were most frequent, accounting for 34.8% of total MPs in the stomach and 22.0% in the intestine. Particles of 125 µm represented 26.1% and 34.0%, 250 µm particles 21.7% and 20.0%, and 500 µm particles 17.4% and 24.0% in stomach and intestine, respectively. No significant differences in particle size distribution were detected between organs or sexes (p = 0.379, p = 0.369).

3.2 Microplastic identification

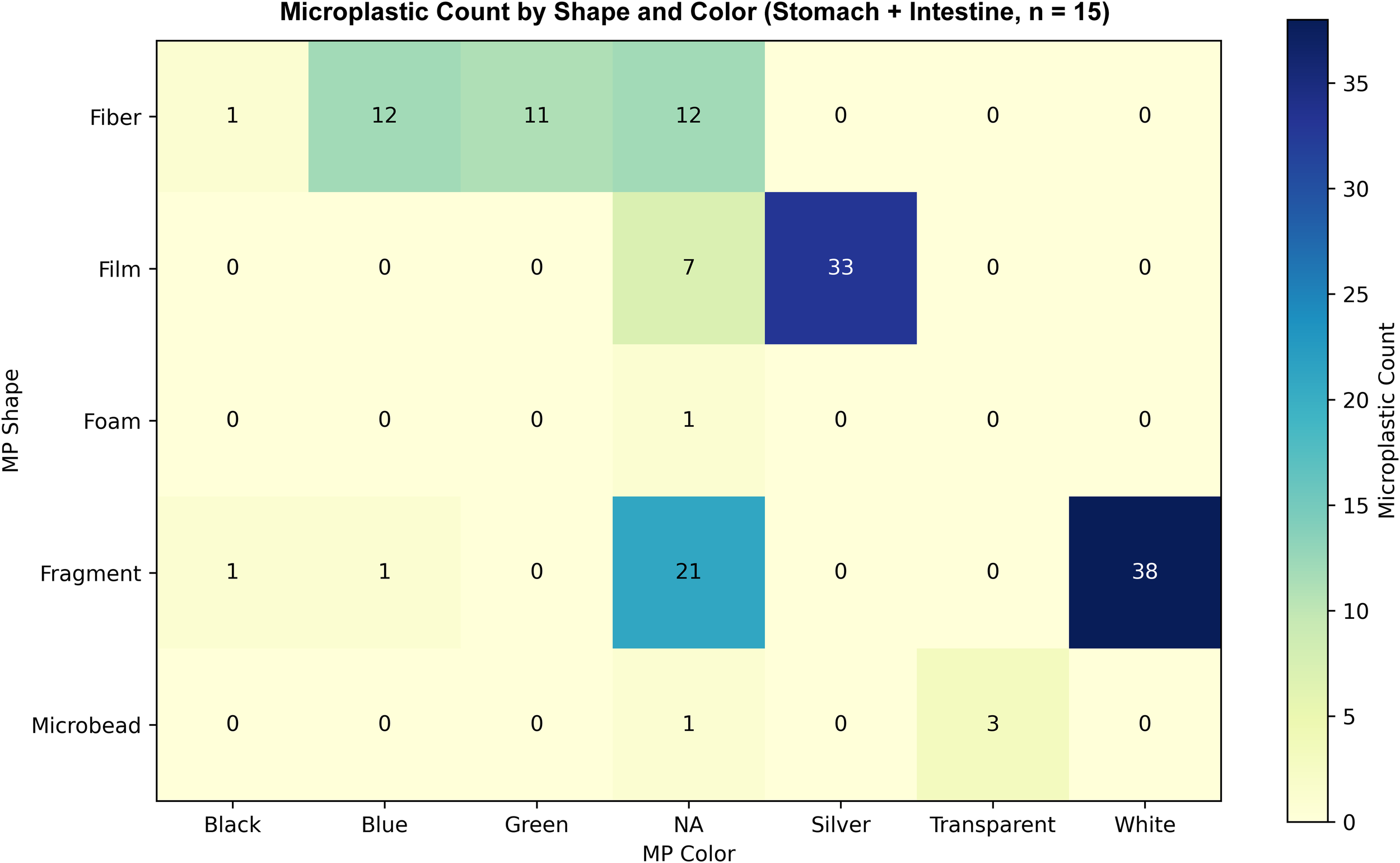

Among the 15 contaminated Fiji maskrays, fragments were most abundant (n = 61), followed by films (n = 40) and fibers (n = 36). Shape distributions did not differ between organs or sexes for fibers, films, foams, fragments, or microbeads (p = 0.589, p = 0.717). In 12 contaminated individuals, white (n = 38) and silver (n = 33) dominated. Color distributions likewise did not differ between organs or sexes for black, blue, green, silver, transparent, or white (p = 0.483, p = 0.913). Overall, MP characteristics did not differ across organs (PERMANOVA, F = 0.911, R2 = 0.016, p = 0.409; Figures 2, 3). Disc width was positively correlated with total MP count (Spearman ρ = 0.562, p = 0.008).

Figure 2

Heatmap of microplastic counts in the stomach and intestine of 15 Fiji maskrays with at least one particle. Particles are classified by shape and color; “NA” denotes unrecorded color (observed in three specimens). Shading reflects total counts per cell; 142 particles were recorded in total.

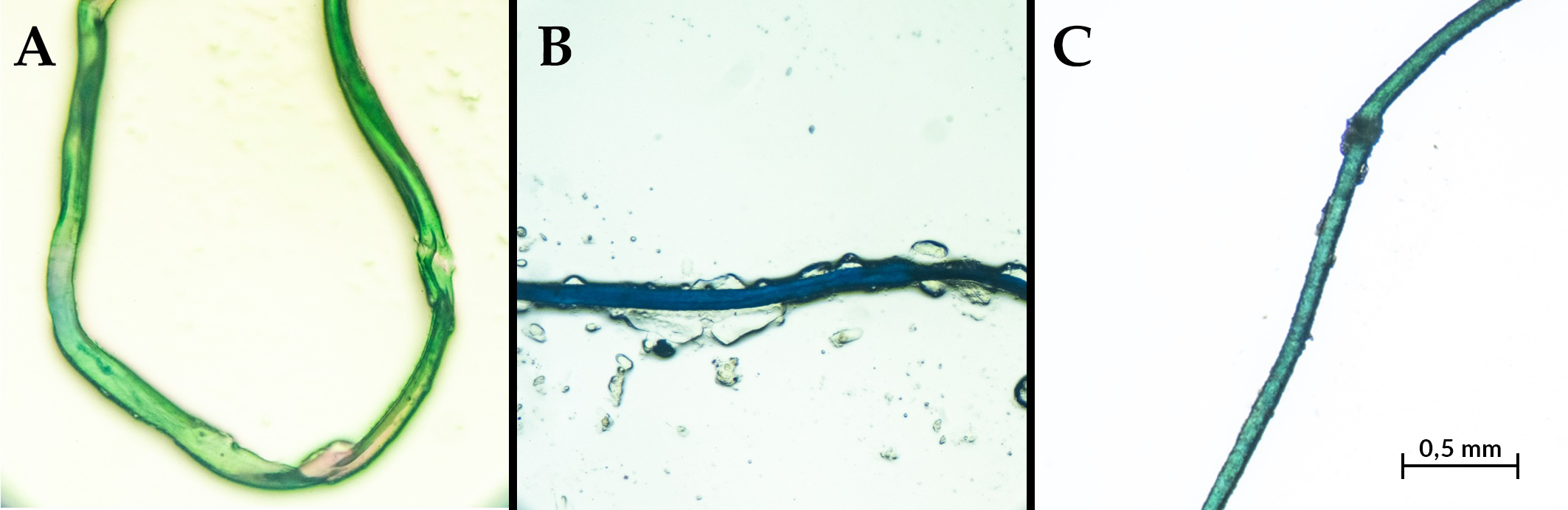

Figure 3

Types of microplastics identified in the gastrointestinal tract of Fiji maskrays. (A) Green fiber; (B) Blue fragment with irregular edges; (C) Monofilament-like fiber with surface abrasions and a visible knot.

3.3 Health, energy reserves, and physiological state

The HSI was calculated for 20 Fiji maskrays. Hepatosomatic index (WT and TWA) did not differ significantly between liver color groups (p = 0.052). Median values are 2.579 (DB) and 3.903 (LB) for WT, and 2.492 (DB) and 3.771 (LB) for TWA. However, no significant association between liver color and sex, maturity, DW or MP count was noted (GLM, p > 0.05). Although a weak to moderate negative correlation was found between MP presence and HSI (WT and TWA), this relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.128, ρ = –0.352; Supplementary Table S1).

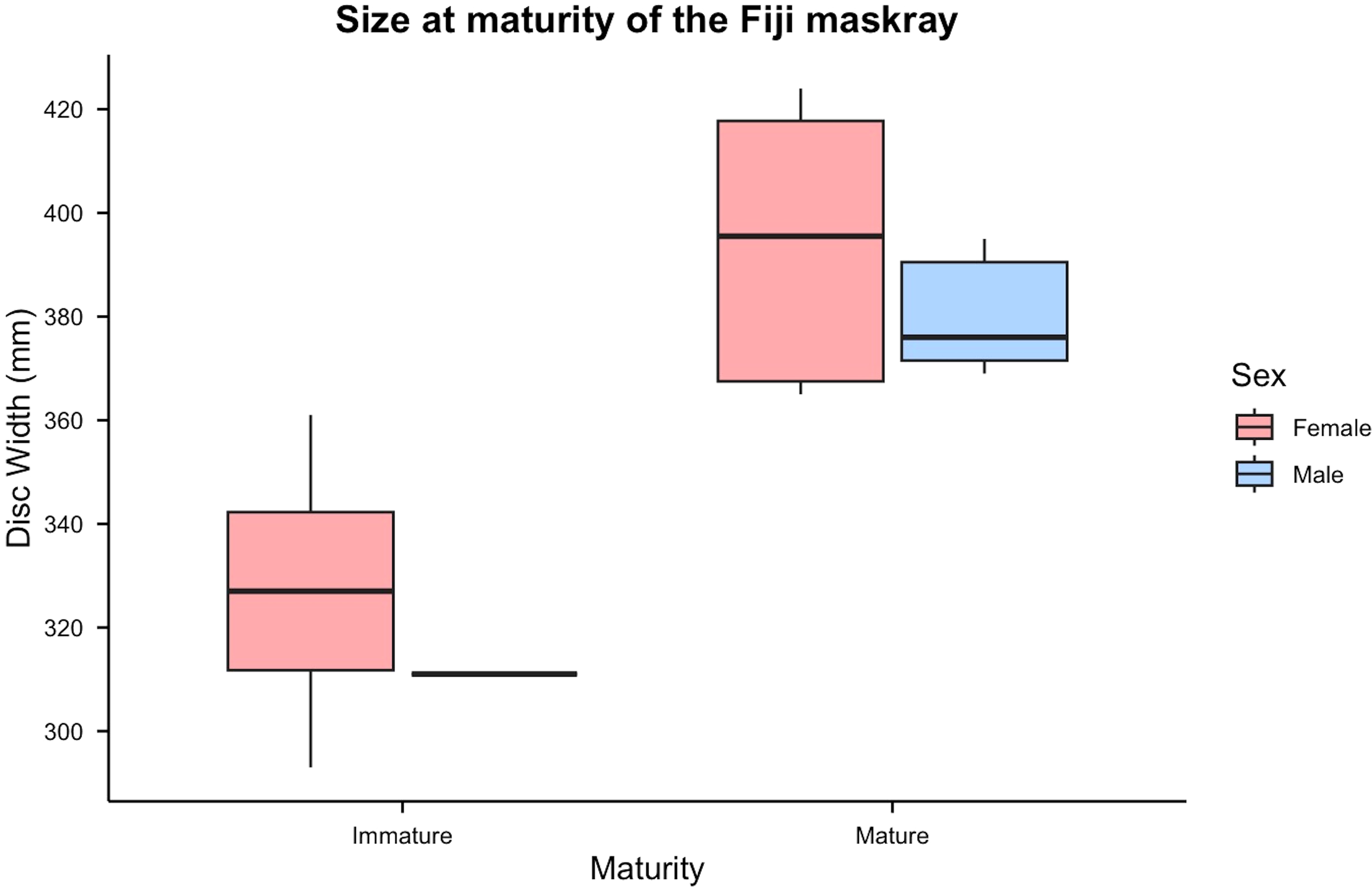

3.4 Size at maturity

Size and sex were determined for 21 Fiji maskrays. One female (TV_Neotrygon_sp5) had undetermined maturity and was excluded, leaving 20 individuals for analysis (12 females, 60%; eight males, 40%). Among females, four were immature (33.3%; 293–361 mm DW; mean 327 ± 2.49 mm) and eight were mature (66.7%; 365–424 mm DW; mean 394 ± 2.55 mm). Among males, one was immature (12.5%; 311 mm DW) and seven were mature (87.5%; 369–395 mm DW; mean 381 ± 1.03 mm) (Figure 4). Males reached maturity at smaller maximum sizes than females.

Figure 4

Size at maturity of the Fiji maskray. Disc width (mm) of immature and mature individuals is shown separately for females (red) and males (blue).

4 Discussion

4.1 Microplastic presence & distribution across stomach and intestine

Plastics are ubiquitously present across the lithosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere (Ziani et al., 2023), affecting marine ecosystems via habitat smothering, enhanced bioavailability, and toxin transfer along food chains (Jiang, 2018). This study reports the first data on MP contamination in the Fiji maskray from the Pacific island region. Overall, 71.43% of examined Fijian maskray individuals contained MPs, with contamination being somewhat higher in the stomach than in the intestine, albeit not significantly (p = 0.331; Figure 1). Microplastics ranged from 63 to 500 µm, with a mean of 6.76 ± 7.80 particles per specimen. Comparable contamination has been reported for other local marine taxa. For example, freshwater mussels (Batissa violacea) and shellfish (Anadara antiquata) from Viti Levu rivers had 0.9–5.9 MP particles per specimen (Barrientos et al., 2022; Powell et al., 2025). Among teleost fishes in Viti Levu, 67 - 74% of individuals contained MPs with mean loads of 1.8–17.0 particles per specimen, varying across locations (Ferreira et al., 2020; Drova et al., 2025).

Globally, demersal elasmobranchs average 4.0 ± 7.32 particles per specimen (Gong et al., 2024). Lower MP counts, averaging 2.4–3.8 particles per specimen, were reported for the Longnose stingray (Hypanus guttatus) and the Xingu freshwater stingray (Potamotrygon leopoldi) in Brazil. This likely reflects local exposure, with urban runoff and plastic waste retained in flooded forests, increasing fragmentation but limiting availability in main foraging channels (Pegado et al., 2021; Trindade et al., 2023). However, higher MP contamination (10.2 ± 7.4 MP particles/specimen) was detected in Haller’s Round stingrays (Urobatis halleri) from California, USA, an important small-scale fisheries habitat (Pinho et al., 2022). Nonetheless, compared to the Fiji maskray, stingrays from Brazil and California showed lower MP contamination rates across sample individuals, ranging from 30 - 60% (Pegado et al., 2021; Pinho et al., 2022; Trindade et al., 2023). Such differences may reflect lower local inputs, different sampling seasons or methods, or contrasts in habitat use and diet. Although the Fiji maskray shows higher MP counts than examined ray species in Brazil and slightly lower MP counts than rays in California, values fall within the range reported for benthic and demersal taxa around Viti Levu (Ferreira et al., 2020; Barrientos et al., 2022; Drova et al., 2025; Powell et al., 2025). This pattern points to local exposure pathways. The Suva–Rewa–Tailevu corridor has dense settlement and active small-scale fishery activities. Gillnets and other plastic gear that, when lost or discarded, degrade in situ thereby adding particles to nearshore habitats (Andrady, 2017; Godoy et al., 2019; Ferreira et al., 2020; Barrientos et al., 2022; Drova et al., 2025; Powell et al., 2025). Also, nearby agriculture and household runoff further add plastics and microfragments, especially along densely settled corridors, with likely amplified inputs from urban and peri-urban areas such as Nausori. Local hydrodynamics and retention in bays and reef-fringed lagoons can keep particles in contact with benthic feeders longer than in open coasts.

4.2 Microplastic identification

Understanding the origin of MPs is critical for reducing their presence and impacts on marine ecosystems. Microplastics are commonly categorized as pellets, fragments, films, or fibers (Guo and Wang, 2019). Microplastics found in the Fiji maskray were dominated by fragments, film, and fibers, with the majority being white or silver (Figures 2, 4). Teleost of Southeast Viti Levu showed similarities in shape dominance of fragments and fibers, and high SD of MP count between individuals (Ferreira et al., 2020). Southeast Viti Levu is strongly affected by wind, waves, and frequent flooding during cyclone season (Mangubhai et al., 2019). Insufficient waste management coupled with extreme weather conditions likely accelerates plastic breakdown (Varea et al., 2020; Drova et al., 2025), whereas plastics are washed through the continuum, eventually reaching the coastal area. Once plastics reach the coast, weathering can slowly break down larger particles into MPs. Also, strong UV radiation increases the degradation process of plastics (GESAMP, 2015). Additionally, discoloration of plastic particles occurs in advanced stages of degradation (Sutkar et al, 2023), possibly explaining the dominance of white and silver MPs in the Fiji maskray specimens.

In examined rays from other regions, fibers and blue colored MPs were predominant (Pegado et al., 2021; Pinho et al., 2022; Trindade et al., 2023). Fibers most likely originated from textile abrasion during washing (Mishra et al., 2024). Population density peaks in Suva, and comparably lower densities elsewhere within the Suva–Rewa–Tailevu corridor may translate into lower fiber inputs from domestic sources. By contrast, fragments and films are more likely to originate from discarded packaging and urban runoff (Burns and Boxall, 2018; Akdogan and Guven, 2019). Furthermore, MPs ingested by rays (Pinho et al., 2022; Pasalari et al., 2025) or demersal fish (Ferreira et al., 2020) are likely linked to MPs found in the sediments of the species habitat, its feeding strategy of how to obtain and select food sources, or MP contaminated prey. Fiji maskrays occur from the littoral zone to at least 23 m depth, inhabiting sandy bottoms, seagrass beds, muddy–sandy substrates, and coral reefs (Glaus et al., 2025). Microplastics that reach the ocean may sink and accumulate in benthic habitats (GESAMP, 2016). Given its nearshore habitat and likely benthic feeding, the Fiji maskray may be exposed to MP from urban runoff, littering, and textile fibers released via wastewater. We found no relevant sex-specific differences in MP uptake, suggesting that females and males either co-occur in the same habitats or that different habitats are affected to a comparable degree by MP pollution. The relatively high SD in particles per specimen may reflect this spatial heterogeneity or differing foraging histories. Due to the small sample size, variability is high, and a few extreme values can disproportionately affect the variance. Sampling was conducted year-round with the same fisher and methods within the same area, reducing procedural variation. However, as GPS positions were not disclosed, minor differences in capture location may have contributed to the observed variability. Nonetheless, it is plausible that Fiji maskrays are exposed to MPs throughout their life (Ferreira et al., 2020), corroborated by the positive monotonic relationship between size (DW) and MP (p = 0.008, ρ = 0.562). Contrastingly, Trindade et al. (2023) found no significant correlation between number of plastic particles and ray size (DW), possibly indicating that MP particles do not bioaccumulate.

4.3 Health, energy reserves, and physiological conditions

Hepatosomatic index, being a morphometric index, is commonly used as a biological indicator, however its sensitivity requires careful interpretation (Martins et al., 2023). Although used to assess how environmental factors influence the health or physiological state of elasmobranchs, it can vary across species, seasons and environmental conditions (Reis and Figueira, 2020). Relative to values reported for rays sampled in Australia, Fiji maskray HSI appears lower than that of fiddler rays (Trygonorrhina fasciata; Reis and Figueira, 2020), but within the range reported for other members of the Neotrygon species complex (Pierce et al., 2009). Higher HSI values can be correlated with reproductive readiness (Pierce et al., 2009; Reis and Figueira, 2020). The weak to moderate negative correlation between MP presence and HSI, although not statistically significant, may indicate a subtle physiological response. Microplastic contamination can affect an individual’s molecular, biochemical, and cellular pathways (Avio et al., 2017), possibly leading to oxidative damage in gills and muscles, endocrine disruption, or cell mutation (Ašmonaitė et al., 2018; Varea et al., 2021). For example, in two species of catsharks (Scyliorhinus canicula & Galeus melastomus) from the Balearic Islands, with high MP contamination the detoxification process was activated and caused changes at cellular level (Torres et al., 2024). In addition, MP count had no significant effect on liver color, nor was liver color associated with sex, maturity, or body size. Given the relatively low HSI values and instances of liver darkening in Fiji maskrays, potential links between MP contamination and toxicological effects merit further investigation. Although total body weight was approximated using different tail-weight percentages to derive TWA, results were consistent across calculations.

4.4 Size at maturity

Many batoids generally grow slowly, mature late, and have low fecundity compared to teleost fishes (Stevens et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2009). Here, immature females measured 293–361 mm DW (n = 4), while mature females ranged from 365–424 mm (n = 9; Figure 3). We suggest that females reach sexual maturity at approximately 360–365 mm DW. The only immature male measured 311 mm DW, while mature males ranged between 369 and 395 mm (n = 7), pointing at a similar size at maturity, although more specimens are required to confirm this. Within the Neotrygon species complex, which has undergone several taxonomic revisions (Last et al., 2016), the southeast Queensland form previously assigned to N. kuhlii likely corresponds to other members of the complex, including the Coral Sea maskray (N. trigonoides) and the Australian bluespotted maskray (N. australiae). These species reach a larger maximum size of approximately 470 mm DW, with females maturing at around 314 mm and males at 294 mm (Pierce et al., 2009). Although the Fiji maskray reaches a smaller maximum size than other members of the Neotrygon species complex, it matures at a relatively larger proportion of its adult size. The warmer Fijian water could support faster somatic growth, where elevated temperatures may accelerate growth rates (Kingsolver, 2009) and size attainment but delay sexual maturation if more energy is initially allocated to growth. High prey availability in Fiji’s estuarine habitats may also support faster growth, with reproduction beginning only once sufficient energy reserves are reached. Future work examining vertebral band deposition (Mejía-Falla et al., 2014) would help determine growth rates and age at maturity in the Fiji maskray. Measuring sex pheromones in females could further clarify reproductive timing and temperature-related patterns (Elisio et al., 2019).

Fiji maskrays, like other co-occurring taxa, are exposed to locally derived MPs, with contamination increasing with body size yet not clearly reflected in hepatosomatic condition; future non-lethal, long-term field studies with larger sample sizes should target sublethal toxicological effects using biomarkers and repeated-measure condition indices and assess population-level consequences of chronic exposure. In parallel, systematic MP assessments and hotspot mapping (GESAMP, 2015), aligned with initiatives such as “Plastic Free Fiji” (United Nations, 2021), can help guide waste management and mitigation efforts to reduce plastic pollution pressure on South Pacific coastal ecosystems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30358048.

Ethics statement

The research study was approved by the Pacific-European Union Marine Partnership (PEUMP) program Project Management and the Head of the School of Agriculture, Geography, Environment, Ocean and Natural Sciences at the USP, Suva, Fiji. No animal was killed specifically for this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RD: Conceptualization, Validation, Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis. WS: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Writing – review & editing. TV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Visualization. KG: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the PEUMP program within the PAGoDA Grant Agreement, key result area 6: “Capacity built through education, training and research and development for key stakeholder groups in fisheries and marine resource management”, led by the USP under the Institute of Marine Resources, Centre for Sustainable Futures. The PEUMP program is a regional initiative funded by the European Union and Government of Sweden to support the sustainable management and development of fisheries for food security and economic growth in the Pacific.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Suneel Salen for providing the Fiji maskray specimens used in this study. We are thankful for Shyna Prasad’s help during initial lab and analytical work. We appreciate the PEUMP project team and the staff of USP Centre for Sustainable Futures for their ongoing support during the study. We thank Amanda Ford for her advice and guidance. Special thanks go to Sharon Appleyard for her helpful review prior to journal submission. KG likes to thank the Deutsche Stiftung Meeresschutz for their continuous support and advise.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors declare that the generative AI ChatGPT was used for coding purposes in R Studio and for grammar checks. Additionally, Scopus AI was used in literature research. All content created was reviewed, edited, and verified by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1734954/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adobe Inc (2023). “ Adobe Photoshop,” in Adobe Systems. (California, United States: Adobe Inc). Available online at: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html (Accessed September 21, 2025).

2

Agius C. (1980). Phylogenetic development of melano–macrophage centres in fish. J. Zool.191, 11–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb01446.x

3

Akdogan Z. Guven B. (2019). Microplastics in the environment: A critical review of current understanding and identification of future research needs. Environ. pollut.254, 113011. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113011

4

Alkusairy H. Ali M. Saad A. Reynaud C. Capapé C . (2014). Maturity, reproductive cycle, and fecundity of spiny butterfly ray, Gymnura altavela (Elasmobranchii: Rajiformes: Gymnuridae), from the coast of Syria (eastern Mediterranean). Acta Ichthyol. Piscat.44, 229–240. doi: 10.3750/AIP2014.44.3.07

5

Allen G. R. Robertson D. R. (1994). Fishes of the Tropical Eastern Pacific (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press).

6

Amini-Birami F. Keshavarzi B. Esmaeili H. R. Moore F. Busquets R. Saemi-Komsari M. et al . (2023). Microplastics in aquatic species of Anzali wetland: An important freshwater biodiversity hotspot in Iran. Environ. pollut.330, 121762. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121762

7

Ammar E. Mohamed M. S. Sayed A. E.-D. H. (2022). Polyethylene microplastics increases the tissue damage caused by 4-nonylphenol in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio) juvenile. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1041003

8

Andradi-Brown D. A. Veverka L. Free B. Ralifo A. Areki F . (2022). Status and trends of coral reefs and associated coastal habitats in Fiji’s Great Sea Reef (Washington, D.C. & Suva: World Wildlife Fund US, WWF-Pacific Programme, and Ministry of Fisheries Fiji), 142158773. doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.13228910

9

Andrady A. L. (2017). The plastic in microplastics: A review. Mar. pollut. Bull.119, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082

10

Ašmonaitė G. Larsson K. Undeland I. Sturve J. Carney Almroth B . (2018). Size matters: ingestion of relatively large microplastics contaminated with environmental pollutants posed little risk for fish health and fillet quality. Environ. Sci. Technol.52, 14381–14391. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b04849

11

Avio C. G. Gorbi S. Regoli F. (2017). Plastics and microplastics in the oceans: From emerging pollutants to emerged threat. Mar. Environ. Res.128, 2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2016.05.012

12

Barrientos E. E. Paris A. Rohindra D. Rico C . (2022). Presence and abundance of microplastics in edible freshwater mussel. Mar. Freshw. Res.73, 528–539. doi: 10.1071/MF21223

13

Brown K. T. Seeto J. Lal M. M. Miller C. E . (2016). Discovery of an important aggregation area for endangered scalloped hammerhead sharks, Sphyrna lewini, in the Rewa River estuary, Fiji Islands. Pac. Conserv. Biol.22, 242. doi: 10.1071/PC14930

14

Burns E. E. Boxall A. B. A. (2018). Microplastics in the aquatic environment: Evidence for or against adverse impacts and major knowledge gaps. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.37, 2776–2796. doi: 10.1002/etc.4268

15

Campbell M. J. McLennan M.F. Courtney A.J. Simpfendorfer C.A . (2021). Life-history characteristics of the eastern shovelnose ray. Mar. Freshw. Res.72, 1280–1289. doi: 10.1071/MF20347

16

Central Intelligence Agency (2025). Fiji — The world factbook ( Central Intelligence Agency/The World Factbook). Available online at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/Fiji/geography (Accessed October 16, 2025).

17

Chassignet E. P. Xu X. Zavala-Romero O. (2021). Tracking marine litter with a global ocean model: where does it go? Where does it come from? Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667591

18

Cordova M. R. Purwiyanto A. I. S. Suteja Y. (2019). Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in the northern coastal waters of Surabaya, Indonesia. Mar. pollut. Bull.142, 183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.03.040

19

Davuke R. Sevakarua W. Vierus T. Glaus K. . (2025). Dataset for analysis of: Microplastic contamination and size at maturity estimates in the endemic Fiji Maskray (Neotrygon romeoi) (Zurich: Figshare). doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30358048

20

Dehm J. Singh S. Ferreira M. Piovano S . (2020). Microplastics in subsurface coastal waters along the southern coast of Viti Levu in Fiji, South Pacific. Mar. pollut. Bull.156, 111239. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111239

21

Drova E. Tuqiri N. Prasad K. Rosi A. Gadekilakeba T. Bai A. et al . (2025). Microplastic occurrence in 21 coastal marine fish species from fishing communities on Viti Levu, Fiji. Mar. pollut. Bull.216, 118045. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.118045

22

Ebert D. A. Cowley P. D. (2009). Reproduction and embryonic development of the blue stingray, Dasyatis chrysonota, in southern African waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. Utd. K.89, 809–815. doi: 10.1017/S0025315408002907

23

Elisio M. Awruch C. A. Massa A. M. Macchi G. J. Somoza G. M . (2019). Effects of temperature on the reproductive physiology of female elasmobranchs: The case of the narrownose smooth-hound shark (Mustelus schmitti). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.284, 113242. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.113242

24

Ferreira M. Thompson J. Paris A. Rohindra D. Rico C . (2020). Presence of microplastics in water, sediments and fish species in an urban coastal environment of Fiji, a Pacific small island developing state. Mar. pollut. Bull.153, 110991. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.110991

25

Fiji Bureau of Statistics (2017). Population and Demographic Indicators ( Fiji Bureau of Statistics). Available online at: https://www.statsFiji.gov.fj/statistics/social-statistics/population-and-demographic-indicators/ (Accessed October 5, 2025).

26

Fiji Bureau of Statistics (2024). Experimental GIS FIJI Population Grid 2023. FBoS Release 80 (Suva: Fiji Bureau of Statistics). Available online at: https://www.statsFiji.gov.fj/experimental-gis-Fiji-population-grid-2023/ (Accessed October 16, 2025).

27

Fox J. Weisberg S. (2019). An {R} Companion to Applied Regression (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication). Available online at: https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion/ (Accessed October 25, 2025).

28

GESAMP (2015). Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: a global assessment Vol. 90 (London: IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection), 96.

29

GESAMP (2016). Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: part two of a global assessment (London: IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection). Available online at: http://www.gesamp.org/site/assets/files/1275/sources-fate-and-effects-of-microplastics-in-the-marine-environment-part-2-of-a-global-assessment-en.pdf (Accessed October 9, 2025).

30

Glaus K. B. J. Brunnschweiler J. M. Piovano S. Mescam G. Genter F. Fluekiger P. et al . (2019). Essential waters: Young bull sharks in Fiji’s largest riverine system. Ecol. Evol.9, 7574–7585. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5304

31

Glaus K. White W. T. O’Neill H. L. Thurnheer S. Appleyard S. A . (2025). A new blue-spotted Maskray species (Neotrygon, Dasyatidae) from Fiji. J. Fish. Biol.107 (3), 963–974. doi: 10.1111/jfb.70094

32

Glaus K. Gordon L. Vierus T. Marosi N. D. Sykes H. . (2024b). Rays in the shadows: batoid diversity, occurrence, and conservation status in Fiji. Biology13, 73. doi: 10.3390/biology13020073

33

Glaus K. Loganimoce E. Mescam G. Appleyard S. A . (2024a). Genetic diversity of an undescribed cryptic maskray (Neotrygon sp.) species from Fiji. Pac. Conserv. Biol.30, 1–3. doi: 10.1071/PC23064

34

Glaus K. Savou R. Brunnschweiler J. M. (2024c). Characteristics of Fiji’s small-scale ray fishery and its relevance to food security. Mar. Policy163, 106082. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106082

35

Godoy V. Martín-Lara M. A. Calero M. Blázquez G . (2019). Physical-chemical characterization of microplastics present in some exfoliating products from Spain. Mar. pollut. Bull.139, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.026

36

Gong Y. Gao H. Guo Z. Huang X. Li Y. Li Z. et al . (2024). Uncovering the global status of plastic presence in marine chondrichthyans. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish.34, 1351–1369. doi: 10.1007/s11160-024-09877-9

37

Guo X. Wang J. (2019). The chemical behaviors of microplastics in marine environment: A review. Mar. pollut. Bull.142, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.03.019

38

Huvet A. Frère L. Lacroix C. Rinnert E. Lambert C. Paul-Pont I . (2025). Microplastics as sorption materials of herbicides, persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a coastal bay. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.89, 104279. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2025.104279

39

Jiang J.-Q. (2018). Occurrence of microplastics and its pollution in the environment: A review. Sustain. Prod. Consum.13, 16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2017.11.003

40

José S. Jordao L. (2020). Exploring the interaction between microplastics, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and biofilms in freshwater. Polycycl. Arom. Compd.42, 2210–2221. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2020.1830809

41

Kingsolver J. G. (2009). The well-temperatured biologist: (American society of naturalists presidential address). Am. Nat.174, 755–768. doi: 10.1086/648310

42

Kinigopoulou V. Pashalidis I. Kalderis D. Anastopoulos I . (2022). Microplastics as carriers of inorganic and organic contaminants in the environment: A review of recent progress. J. Mol. Liq.350, 118580. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118580

43

Last P. R White W. T Séret B (2016) “Taxonomic status of maskrays of the Neotrygon kuhlii species complex (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) with the description of three new species from the Indo-West Pacific,”Zootaxa, 4083, 533–561. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4083.4.5

44

Maechler M. et al . (2025). cluster: cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions ( R package version 2.1.8.1). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster (Accessed October 25, 2025).

45

Mangubhai S. Sykes H. Lovell E. Brodie G. Jupiter S. Morris C. et al . (2019). “ Chapter 35 - FIJI: coastal and marine Ecosystems,” in World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition), 2nd ed. Ed. SheppardC. (London, United Kingdom: Academic Press), 765–792. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100853-9.00044-0

46

Marcon J. L. Morales-Gamba R. D. Barcellos J. F. M. Araújo M. L. G. D . (2021). Sex steroid hormones and the associated morphological changes in the reproductive tract of free-living males of the cururu stingray Potamotrygon wallacei. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.309, 113786. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2021.113786

47

Martins M. F. Costa P. G. Bianchini A. (2023). Bioaccumulation and potential impacts of persistent organic pollutants and contaminants of emerging concern in guitarfishes and angelsharks from Southeastern Brazil. Sci. Tot. Environ.893, 164873. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164873

48

Mejía-Falla P. A. Cortés E. Navia A. F. Zapata F. A . (2014). Age and growth of the round stingray urotrygon rogersi, a particularly fast-growing and short-lived elasmobranch. PloS One9, e96077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096077

49

Mishra S. Ren Y. Sun X. Lian Y. Singh A. K. Sharma N . (2024). Microplastics pollution in the Asian water tower: Source, environmental distribution and proposed mitigation strategy. Environ. pollut.356, 124247. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124247

50

Montero-Hernández G. Caballero M. J. Curros-Moreno Á. Suárez-Santana C. M. Rivero M. A. Caballero-Hernández L. et al . (2024). Pathological study of a traumatic anthropogenic injury in the skeleton of a spiny butterfly ray (Gymnura altavela). Front. Vet. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1452659

51

Neyrão I. M. Conrado A. L. V. Takatsuka V. Bruno C. E. M. de Azevedo V. G . (2019). Quantification of liver lipid deposition and melano-macrophages in lesser guitarfish Zapteryx brevirostris submitted to different feeding cycles. Comp. Clin. Pathol.28, 805–810. doi: 10.1007/s00580-019-02953-8

52

Oksanen J. Simpson G. L. Blanchet F. G. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. R. et al . (2025). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan

53

Parker B. Andreou D. Green I. D. Britton J. R . (2021). Microplastics in freshwater fishes: Occurrence, impacts and future perspectives. Fish. Fish.22, 467–488. doi: 10.1111/faf.12528

54

Pasalari M. Esmaeili H. R. Keshavarzi B. Busquets R. Abbasi S. Momeni M. . (2025). Microplastic footprints in sharks and rays: First assessment of microplastic pollution in two cartilaginous fishes, hardnose shark and whitespotted whipray. Mar. pollut. Bull.212, 117350. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117350

55

Pegado T. Brabo L. Schmid K. Sarti F. Gava T. T. Nunes J. et al . (2021). Ingestion of microplastics by Hypanus guttatus stingrays in the Western Atlantic Ocean (Brazilian Amazon Coast). Mar. pollut. Bull.162, 111799. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111799

56

Pierce S. J. Pardo S. A. Bennett M. B. (2009). Reproduction of the blue-spotted maskray Neotrygon kuhlii (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) in south-east Queensland, Australia. J. Fish. Biol.74, 1291–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02202.x

57

Pinho I. Amezcua F. Rivera J. M. Green-Ruiz C. Piñón-Colin T. D. J. Wakida F. . (2022). First report of plastic contamination in batoids: Plastic ingestion by Haller’s Round Ray (Urobatis halleri) in the Gulf of California. Environ. Res.211, 113077. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113077

58

Powell W.-J. Varea R. Williams L. Naivalurua J. Brown K. T. Dehm J . (2025). Comparison of historical, (1980s) and contemporary, (2023–2024) microplastic contamination of arc clams (Anadara spp.) from tidal flats in Suva, Fiji. Mar. pollut. Bull.220, 118401. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.118401

59

QGIS Development Team (2025). QGIS Geographic Information System ( QGIS Association). Available online at: https://www.qgis.org (Accessed October 5, 2025).

60

R Core Team (2025). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed September 5, 2025).

61

Reis M. Figueira W. F. (2020). Age, growth and reproductive biology of two endemic demersal bycatch elasmobranchs: Trygonorrhina fasciata and Dentiraja australis (Chondrichthyes: Rhinopristiformes, Rajiformes) from Eastern Australia. Zoologia37, 1–12. doi: 10.3897/zoologia.37.e49318

62

Stevens J. Bonfil R. Dulvy N. K. Walker P. . (2000). The effects of fishing on sharks, rays, and chimaeras (chondrichthyans), and the implications for marine ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci.57, 476–494. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0724

63

Stevens J. McLoughlin K. (1991). Distribution, size and sex composition, reproductive biology and diet of sharks from Northern Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res.42, 151. doi: 10.1071/MF9910151

64

Sun Q. Ren S.-Y. Ni H.-G. (2022). Effects of microplastic sorption on microbial degradation of halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water. Environ. pollut.313, 120238. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120238

65

Sutkar P. R. Gadewar R. D. Dhulap V. P. (2023). Recent trends in degradation of microplastics in the environment: A state-of-the-art review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv.11, 100343. doi: 10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100343

66

Torres S. Compa M. Box A. Pinya S. Sureda A . (2024). Presence and potential effects of microplastics in the digestive tract of two small species of shark from the balearic islands. Fishes9, 55. doi: 10.3390/fishes9020055

67

Trindade P. A. A. Brabo L. D. M. Andrades R. Azevedo-Santos V. M. Andrade M. C. Candore L. et al . (2023). First record of plastic ingestion by a freshwater stingray. Sci. Tot. Environ.880, 163199. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163199

68

United Nations (2021). Plastic pollution - Free FIJI Campaign (United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs – SDG Partnerships Plattform). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/plastic-pollution-free-Fiji-campaigndescription (Accessed October 5, 2025).

69

Varea R. Paris A. Ferreira M. Piovano S . (2021). Multibiomarker responses to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and microplastics in thumbprint emperor Lethrinus harak from a South Pacific locally managed marine area. Sci. Rep.11, 17991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97448-4

70

Varea R. Piovano S. Ferreira M. (2020). Knowledge gaps in ecotoxicology studies of marine environments in Pacific Island Countries and Territories – A systematic review. Mar. pollut. Bull.156, 111264. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111264

71

Wickham H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis ( Springer-Verlag New York). Available online at: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (Accessed September 6, 2025).

72

Wickham H. Bryan J. (2015). readxl: read excel files. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.readxl

73

Wickham H. François R. Henry L. Müller K. Vaughan D . (2014a). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.dplyr

74

Wickham H. Vaughan D. Girlich M. (2014b). tidyr: tidy messy data. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.tidyr

75

Wilson S.-A. (2012). “ Fiji,” in Politics of Identity in Small Plural Societies: Guyana, the Fiji Islands, and Trinidad and Tobago. Ed. WilsonS.-A. ( Palgrave Macmillan US, New York), 99–124. doi: 10.1057/9781137012128_6

76

Ziani K. Ioniţă-Mîndrican C.-B. Mititelu M. Neacşu S. M. Negrei C. Moroşan E. et al . (2023). Microplastics: A real global threat for environment and food safety: A state of the art review. Nutrients15, 617. doi: 10.3390/nu15030617

Summary

Keywords

Dasyatidae, elasmobranchs, hepatosomatic index, life history, pollution, size at maturity, South Pacific

Citation

Davuke R, Sevakarua W, Vierus T and Glaus K (2026) Microplastic contamination in the endemic Fiji maskray (Neotrygon romeoi). Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1734954. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1734954

Received

29 October 2025

Revised

26 November 2025

Accepted

11 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Xinchen Gu, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, China

Reviewed by

Paulo Trindade, Federal University of Pará, Brazil

Marina Rocha De Carvalho, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Davuke, Sevakarua, Vierus and Glaus.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ramona Davuke, r.davuke@outlook.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.