Abstract

The global shipping industry serves as a cornerstone of international trade, with the second-hand vessel market playing a vital role in capital allocation and risk redistribution. However, its operational efficiency is significantly hampered by information asymmetry. Unlike standardized newbuilds, each second-hand vessel is a unique asset whose true value hinges on “hidden attributes” such as maintenance history and accident records that remain partially inaccessible to buyers. This aligns with the characteristics of the “lemons market” theory, inducing adverse selection and diminishing market efficiency. To address this, this paper constructs an incomplete information static Bayesian game model, abstracting the transaction as a two-stage sequential game where the seller quotes first and the buyer decides subsequently. The aim is to reveal how sellers with information advantages formulate optimal quoting strategies across different vessel types and cost structures, and how buyers at an informational disadvantage develop acceptance/rejection decision rules based on posterior beliefs. Numerical methods (Newton-Raphson iteration) were employed to solve the model equilibrium, calculating equilibrium quotations, transaction probabilities, and seller expected residuals for ten major container vessel types. Benchmark results indicate that sellers can extract information rents through their informational advantage, with rent magnitude increasing alongside vessel size. Comparative channel analysis further reveals that, compared to newbuild and charter markets, the second-hand vessel market exhibits higher transaction probabilities and premium levels due to greater information asymmetry. Robustness tests incorporating buyer risk aversion, discrete type spaces, and reservation prices confirm that the model’s core findings remain stable. This research provides a theoretical framework and quantitative basis for understanding the micro-mechanisms of shipping asset transactions under information asymmetry, offering insights for market participants’ pricing decisions and regulators designing mechanisms to enhance market transparency and efficiency.

1 Introduction

Global shipping industry serves as the lifeline of the world economy and trade, carrying over 80% of the volume of international trade goods (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2022). Within this complex and highly cyclical industry, the second-hand ship trading market plays a crucial role, not only facilitating the optimal allocation of shipping capital and dynamic adjustment of capacity structure but also serving as an important mechanism for the redistribution of market risks (Kou et al., 2014). Similar to the automotive market, the ship trading market can be divided into three main channels: newbuilding ships, second-hand ships, and charter ships. Among these, the second-hand ship market, known for its active trading and strong liquidity, has long been regarded as a “barometer” reflecting the level of prosperity of the shipping market (Koç Ustali et al., 2024).

However, unlike standardized newbuildings, each second-hand ship is a unique asset whose true value depends not only on observable characteristics such as ship type, age, and shipyard but also deeply on “hidden attributes” that are difficult for buyers to thoroughly ascertain, including maintenance history, accident records, and actual engine conditions (Her et al., 2019). This significant difference in the mastery of key quality information between trading parties constitutes a typical information asymmetry phenomenon, profoundly affecting market operational efficiency. The “Market for Lemons” theory, first systematically elaborated by Park et al. (2018), describes a situation where sellers have more private information about product quality than buyers, leading to a market dominated by low-quality products. In such markets, buyers cannot effectively distinguish product quality and are only willing to pay a price based on the average quality level, which results in the gradual withdrawal of high-quality products from the market. This phenomenon is known as “adverse selection,” where the market’s inability to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality products leads to a decline in overall market quality or even market collapse (Alizadeh and Nomikos, 2007). The second-hand ship market exhibits characteristics highly consistent with the “Market for Lemons” theory (Shi et al., 2023). Sellers (usually shipowners) possess absolute information advantage regarding the ship’s true technical condition, maintenance history, and operational performance, while buyers (another shipping company or investor) often can only rely on ship certificates, limited on-site inspections, and the seller’s unilateral statements to form value judgments before making trading decisions (Xu and Yip, 2012). This natural inequality in information status creates the risk of systematic underestimation of high-quality ships, while low-quality ships may obtain improper benefits, thereby distorting price signals and reducing market resource allocation efficiency (Mo et al., 2025).

To address market inefficiencies arising from information asymmetry, trading parties engage in a range of strategic behaviors aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of this imbalance. Sellers, for instance, are motivated to signal the high quality of their ships through various means, such as providing comprehensive maintenance records, undergoing detailed inspections by reputable third-party agencies, or offering limited warranties (Junior et al., 2020). Conversely, buyers employ strategies to screen and infer the true value of ships, including setting price thresholds, requesting specific inspection clauses, and relying on the reputations of well-known brokers (Koç Ustali et al., 2024). These interactions form a complex game characterized by incomplete information (Öner et al., 2025). While existing literature has made significant contributions to understanding the second-hand ship market through price index modeling (Fan and Luo, 2013), market efficiency testing (Adland et al., 2018), and macroeconomic cycle analysis (Fan et al., 2023), there remains a notable gap in detailed modeling and quantitative analysis of the micro-level decision-making processes. Specifically, the literature lacks a comprehensive exploration of how sellers optimize their pricing strategies based on private cost information and how buyers update their beliefs and make acceptance or rejection decisions based on observed price signals. This gap underscores the need for more nuanced models that capture the strategic dynamics underpinning these transactions.

Addressing the deficiencies of existing research, this study constructs a static Bayesian game model, abstracting the second-hand ship transaction into a two-stage sequential game process where the seller quotes first and the buyer decides later. The main features of this study are reflected in the following aspects: adopting a refined cost structure design, systematically segmentation costs according to 10 main container ship types based on real market data, more accurately reflecting the intrinsic value differences of different asset categories; establishing explicit decision-making mechanisms, clearly demonstrating the seller’s optimal pricing strategy function and the buyer’s critical acceptance rule based on posterior beliefs through model derivation; using numerical methods for solution and quantitative analysis, employing the Newton-Raphson iteration method for numerical solution to accurately calculate key indicators such as equilibrium quotes, transaction probability, and seller’s expected surplus for different ship types, addressing the characteristic that the model cannot obtain an analytical solution; conducting in-depth robustness tests, going beyond the classical assumption of risk neutrality, introducing factors such as buyer risk aversion, discrete type space, and reserve price to comprehensively test the robustness of the model conclusions; carrying out comparative research across market channels, for the first time systematically comparing the equilibrium results of three market channels—newbuilding, second-hand, and charter—within the same theoretical framework, deeply revealing the impact of differences in the degree of information asymmetry on market efficiency.

This study not only deepens our theoretical understanding of the shipping asset trading mechanism under information asymmetry but also provides accurate pricing and decision-making references for market participants (including shipowners, investors, and brokers). Meanwhile, it offers an important theoretical basis for regulators to design mechanisms to improve market transparency and efficiency. The subsequent structure of the paper is arranged as follows: the second part provides a systematic review of relevant literature; the third part elaborates on the model construction and theoretical framework; the fourth part presents numerical calculation results, robustness tests, and in-depth discussion; the fifth part summarizes research conclusions and elaborates on their policy implications.

2 Literature review

This study is rooted in the intersection of three major fields: information economics, game theory, and shipping economics. Through a systematic review of relevant literature, it provides solid theoretical support and research positioning for this study. The literature review mainly focuses on three aspects: the theoretical development of information asymmetry and the “market for lemons”, the issue of information asymmetry in shipping asset markets, and the application of game theory in shipping research. Finally, it reviews existing literature and points out research gaps.

2.1 Theoretical foundations of information asymmetry and market mechanisms

The theoretical foundation of information asymmetry economics was laid by Goulielmos and Siropoulou (2006), who profoundly revealed how quality uncertainty can lead to adverse selection and possible market collapse through the “Market for Lemons” model. This groundbreaking work sparked numerous follow-up studies. Kou and Luo (2015) proposed the “signaling” model, pointing out that the informed advantaged party can convey credible information to the disadvantaged party by taking certain visible, cost-differentiated actions. Chang et al. (2012), from the perspective of “information screening”, studied how the disadvantaged party can induce the advantaged party to reveal its private information by designing contract menus. Fan and Luo (2013) further expanded the theory of adverse selection, establishing a more general equilibrium analysis framework. Entering the 21st century, with the rise of the Internet and digital platforms, the study of information asymmetry entered a new stage. Wu et al. (2018) in-depth research on how online reputation systems, as an emerging signaling and community supervision mechanism, significantly reduce information asymmetry in e-commerce. Park et al. (2018) treated information itself as a tradable asset, constructing a model showing that information heterogeneity can amplify asset price volatility. Alizadeh et al. (2017) provided a comprehensive review of the literature on quality disclosure and certification, pointing out that the “lemons problem” Still prevalent exists in the modern economy. These theoretical advances indicate that information asymmetry is a persistent and dynamic market characteristic.

2.2 Information asymmetry in shipping asset markets

In the field of shipping economics, scholars have long recognized the core importance of information asymmetry. Drobetz et al. (2017) described the second-hand ship market as one with serious information problems in his classic work. Xi et al. (2017) through empirical analysis, showed that the degree of information asymmetry is significantly positively correlated with the discount rate of ship transaction prices. Early research focused on price discovery and market effectiveness. Park et al. (2018) used econometric models to construct a second-hand ship price index, finding that unobserved heterogeneity is an important source of price volatility. Grün et al. (2024) pointed out that ship valuation heavily relies on observable characteristics, but the residual valuation differences are large, providing space for the existence of information rents. In recent years, research has become more refined (Junior et al., 2020). in their study of the tanker market, found that market participants rely on public information for price discovery, while private information about the specific condition of the ship leads to deviations in transaction prices. Van Putten et al. (2012) when constructing a ship price index, also found that residual volatility is related to information asymmetry.

Recently, scholars have begun to more directly measure the consequences of information asymmetry and mitigation mechanisms. The research by Quillérou et al. (2013) provided a novel perspective, treating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance as a new type of “hidden information” and proving that better ESG disclosure is associated with higher ship asset values. Grün et al. (2023) studied the impact of information asymmetry on contract structure and duration choices in the ship chartering market from the perspective of contract design. Li and Kavussanos (1996) analyzed the impact of information asymmetry on credit terms in the ship financing market, finding that borrowers with higher information transparency can obtain more favorable loan terms. Shi et al. (2023) studied the potential application of blockchain technology in improving the transparency of shipping transactions, providing a technical perspective for solving the problem of information asymmetry. These studies collectively indicate that information asymmetry is a core dimension for understanding shipping asset pricing, transaction structure, and market efficiency.

Beyond the aforementioned research dimensions, scholars have in recent years begun to examine the impact of information asymmetry on the dynamic processes of ship transactions. In actual second-hand vessel negotiations, information asymmetry manifests not only in static asset valuation but also profoundly influences the bargaining power and negotiation strategies of both parties (Melas et al., 2022; Lee and Yun, 2022). Sellers often maximize their returns by controlling the timing and content of information disclosure, such as selectively releasing vessel inspection reports or operational data (Mitroussi et al., 2016; Mo et al., 2022). Buyers, in turn, employ multi-source information verification and phased bidding strategies to progressively uncover the true picture. This dynamic bargaining process causes the degree of information asymmetry to fluctuate throughout negotiations, creating a complex two-way learning mechanism (Gao et al., 2022). Moreover, the development of digital technology platforms is transforming traditional information transmission methods (Engelen et al., 2007). Online vessel transaction databases and digital inspection tools have, to some extent, reduced information acquisition costs. However, they may simultaneously create new information barriers—market participants who can adapt to and utilize these new technologies more rapidly will gain significant informational advantages (Mo et al., 2025). This digital divide may further exacerbate information asymmetry within the market, posing greater challenges particularly for small and medium-sized shipowners and emerging market participants (Chou and Lin, 2017). Consequently, understanding the dynamic evolution of information asymmetry and its interactive relationship with technological advancement has become a critical frontier in contemporary research.

In recent years, research has shown that information asymmetry in the shipping market not only affects asset pricing and transaction efficiency but also has significant implications for environmental policies and sustainable development in the shipping industry. Xu et al. (2025a) compared the performance of machine learning and econometric methods in forecasting CO2 emissions from global shipping, revealing the potential of technological advancements in addressing environmental challenges. Additionally, Xu et al. (2025b) explored the support policies for shore-to-ship electricity infrastructure, analyzing the tradeoff between government subsidies and port competition, which highlights the importance of policy design in mitigatinginformation asymmetry and promoting green shipping development. Moreover, Xu et al. (2025c) further examined the current status and future direction of international shipping in terms of carbon emissions control, emphasizing the significance of the shipping industry in global emission reduction targets.. Sun et al. (2025a) analyzed the impact of the European Union Emissions Trading System on crude oil transportation, maritime shipping, and EU carbon markets, revealing the complexities of market mechanisms in addressing environmental challenges. Additionally, Sun et al. (2025b) investigated the relationship between shipping market volatility, container freight rates, and inflation, further highlighting the impact of market dynamics on the sustainable development of the shipping industry. These studies indicate that information asymmetry has far-reaching effects on multiple dimensions of the shipping market. It not only affects transaction efficiency but is also closely related to the implementation of environmental policies and market volatility. Therefore, future research needs to consider these factors more comprehensively to better understand and address the impact of information asymmetry on the shipping market.

Recently, several studies have further explored the impact of information asymmetry in the shipping market. Shi et al. (2023) investigated the role of digital platforms in reducing information asymmetry through enhanced transparency and real-time data sharing. They found that digital platforms can significantly mitigate adverse selection by providing more accurate and timely information to market participants. Additionally, Grün et al. (2023) examined the influence of regulatory changes on information disclosure practices in the shipping industry, highlighting the importance of mandatory reporting requirements in improving market efficiency. Furthermore, Hua et al. (2025) explored the use of advanced analytics and machine learning techniques to detect hidden signals in shipping market data, demonstrating that these tools can help buyers better assess the true value of assets and reduce information rents. These recent studies underscore the evolving nature of information asymmetry in the shipping market and highlight the need for continuous adaptation of strategies to address this issue.

2.3 Game-theoretic applications in maritime studies

Game theory, especially games with incomplete information, provides an important tool for modeling and analyzing strategic interactions under information asymmetry. Hua et al. (2025) introduced the concept of “type” and the Harsanyi transformation, converting games with incomplete information into games with imperfect information, laying the methodological foundation for subsequent research. Fan et al. (2024) groundbreaking work in mechanism design theory provided important tools for studying how to design rules to alleviate information asymmetry. In the field of shipping, research applying game theory models is increasing. In terms of solution methods, such as game models often cannot obtain analytical solutions, numerical methods have become an important supplement. Zhang et al. (2014) used agent-based modeling and simulation methods to study the formation of freight rates in the bulk shipping market.

While most existing studies in the shipping market focus on static models, dynamic signaling games have also been explored in other fields to capture the evolving nature of strategic interactions over time. Shi et al. (2023) have demonstrated how dynamic signaling can affect market outcomes in auctions and negotiations. In the context of shipping, dynamic signaling could be relevant for understanding how sellers adjust their strategies over multiple rounds of negotiations or how buyers update their beliefs based on sequential information.

2.4 Literature critique and research gap

Through a systematic review of existing literature, it can be found that the academic community has reached a consensus on the existence, pervasiveness, and macroeconomic impact of information asymmetry in the shipping market and has accumulated considerable empirical evidence. However, existing research still has obvious shortcomings: most studies focus on outcome analysis at the market level but lack in-depth modeling of the micro-decision-making mechanisms that lead to these outcomes; many theoretical models have oversimplified assumptions about cost structure, failing to fully reflect the huge and systematic cost differences between different ship types in the real market; although many studies point out the existence of information rents, few can accurately quantitatively calculate key variables such as information rent levels and transaction probabilities for different ship types; models are usually based on strict assumptions, but discussions on whether these assumptions hold and how much the conclusions would change if the assumptions are relaxed are generally insufficient; newbuilding, second-hand, and charter markets are essentially interconnected alternative channels with vastly different degrees of information asymmetry, but most existing studies analyze a single market in isolation, lacking a comparative analysis of the three within the same theoretical framework.

This study is launched precisely to address the above deficiencies. By constructing a segmented, computable static Bayesian signaling game model, it aims to in-depth analyze the internal mechanism of second-hand ship transaction decisions, quantify the economic consequences of information asymmetry, test the robustness of model conclusions, and deepen the understanding of market structure through cross-channel comparison, thereby forming an important supplement and advancement to existing literature.

3 Model

This chapter focuses on the key issue of information asymmetry in the second-hand ship trading market. By constructing a rigorous and practical static game model of incomplete information, it deeply analyzes the decision-making logic of both buyers and sellers under different ship types and cost structures, laying a solid theoretical foundation for subsequent empirical analysis, risk assessment, and strategy formulation.

3.1 Problem refinement and modeling ideas

The second-hand ship trading market is a typical ‘lemon market’: the true value of the vessel is private information of the seller, while the buyer can only observe public signals such as ship type and age before bidding. To characterize this asymmetric structure, this chapter constructs a static game model under the framework of incomplete information, focusing on two questions:

-

How does the information disadvantage buyer form an ‘accept-reject’ decision rule?

-

How does the information advantaged seller formulate an optimal bidding strategy based on unobservable cost types?

The model uses the Harsanyi transformation to handle private information, discretizing the continuous cost space into several ship type intervals, and describes the buyer’s prior belief with a standard normal distribution, thus simplifying the complex bargaining process into a ‘bidding-threshold’ two-stage decision, providing a computable framework for subsequent numerical simulations and strategy comparisons.

3.2 Elements of the game and symbol system

3.2.1 Participants and timing

In this model, the set of participants is N = {S, B}, where S denotes the seller and B denotes the buyer. The sequence of actions is as follows:

-

Naturally, draw the true total cost (Table 1) according to the vessel type , revealing it only to S;

-

S issues a one-time, non-negotiable offer p (in US$ million) to B;

-

Upon observing p, B simultaneously forms a posteriori belief about c and decides to either ‘Accept’ (A) or ‘Reject’ (R).

Table 1

| Ship type | Shipbuilding cost | Other costs | Total cost | Buying cost | Other costs | Total cost | Leasing cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14000TEU | 19,721 | 10,000 | 29,721 | 18,789 | 9,500 | 28,289 | 28,000 |

| 10000TEU | 13,740 | 9,000 | 22,740 | 18,789 | 9,500 | 28,289 | 28,000 |

| 9200TEU | 12,608 | 9,000 | 21,608 | 13,918 | 9,500 | 23,418 | 21,000 |

| 7200TEU | 10,184 | 9,000 | 19,184 | 7,191 | 9,500 | 16,691 | 17,500 |

| 6600TEU | 9,052 | 7,000 | 16,052 | 6,147 | 7,500 | 13,647 | 17,000 |

| 4800TEU | 6,789 | 6,000 | 12,789 | 2,900 | 6,500 | 9,400 | 14,700 |

| 3800TEU | 5,819 | 5,500 | 11,319 | 2,784 | 6,000 | 8,784 | 9,000 |

| 2500TEU (with crane) | 4,364 | 5,500 | 9,864 | 2,784 | 5,750 | 8,534 | 8,800 |

| 2000TEU (with crane) | 4,041 | 5,500 | 9,541 | 2,436 | 5,750 | 8,186 | 8,200 |

| 1800TEU (with crane) | 3,556 | 5,500 | 9,056 | 2,552 | 5,750 | 8,302 | 7,500 |

Cost differences for new buildings, second-hand sales, and chartering of different container ship types (USD/TEU).

The “Other Costs” column includes maintenance costs, inspection fees, and administrative expenses associated with the acquisition of second-hand ships. These costs do not include depreciation, which is accounted for separately in the financial analysis. The tax status of these costs is treated as deductible business expenses, in accordance with standard accounting practices.

3.2.2 Information structure and beliefs

The buyer’s prior belief is , where i=0.07 , reflecting valuation dispersion caused by market volatility. Since the quoted price is a pure strategy mapping of , can infer the type through . Therefore, the focus of the model solution lies in finding the monotonic strategy under the revealing equilibrium.

3.2.3 Utility function

The seller’s utility function is:

The buyer’s utility function is:

Where, denotes the buyer’s random valuation of the vessel, and I {accept} represents the acceptance indicator function.

3.3 The concept of equilibrium and solution logic

This model employs Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (PBE) as its solution concept, requiring:

-

Given beliefs, Agent B’s strategy is optimal under every information set;

-

Given Agent S’s strategy, Agent B’s beliefs satisfy Bayes’ theorem;

-

Agent S’s strategy constitutes the optimal response under all possible types.

Given that the signaling space (quotation p) is continuous and the type space (cost c) is also continuous, this paper adopts a “direct mechanism” approach: first, perform point-state optimization for the first-order conditions to obtain the type-dependent optimal quotation ; then, verify global incentive compatibility (IC) through monotonicity tests to prevent deviation.

3.4 Derivation of the optimal bidding equation

For any given real cost C, S selects P to maximize expected profit:

Taking the derivative with respect to and setting it equal to zero yields the first-order condition:

Taking the derivative with respect to and setting it equal to zero yields the first-order condition, Where , ϕ(z) and (z) denote the standard normal density function and cumulative distribution function respectively. The follows N(0,1).

After rearrangement, the implicit equation for z is obtained:

where λ(z) is the hazard-rate function, representing the ratio of the probability density function ϕ(z) to the survival function 1−Φ(z). This equation possesses a unique solution within the interval z∈[0,3], and λ(z) is a risk rate function that is monotonically increasing, thereby guaranteeing the uniqueness and computability of the solution.

3.5 Numerical algorithms and implementation steps

As Equation 6 has no analytical solution, this paper employs the Newton-Raphson iteration method for its solution:

Initialization:

Iterative formula:

where:

Convergence criterion:

Having obtained , substitution back into the equation yields:

1. Best available quote:

2. Probability of transaction:

3. Seller’s expected return:

This chapter constructs a static game model to analyze information asymmetry in the second-hand ship market. By defining participants, action sequences, information structures, and payoff functions, we establish a foundation for understanding the decision-making processes of buyers and sellers. The model’s derivation and the design of numerical algorithms provide theoretical underpinnings and computational methods for subsequent empirical analysis. In the next chapter, this study shall utilize this model to analyze actual data, thereby validating its predictions and exploring its practical applications.

4 Results and discussions

4.1 Computational workflow and data preparation

This chapter employs the ten container ship types listed in Table 1 as samples, substituting them into the static incomplete information game model established in Chapter 3 to calculate the equilibrium bid price, transaction probability, and seller’s expected residual for each type. For comparative ease, all monetary values are uniformly expressed in USD/TEU, with costs derived from the ‘Second-hand vessel acquisition + other expenses’ column (the implicit costs actually faced by the buyer).

Procedural notes:

-

Load the cost c for each vessel type from column 6 ‘Total Cost (Buying)’ in Table 1;

-

Set the buyer’s prior mean = c and prior standard deviation σi = 0.07c (baseline scenario);

-

For each vessel type, invoke Newton-Raphson to solve the implicit Equation 5 with a convergence tolerance of 1×10−4;

-

4.Record the optimal bid , transaction probability , and seller’s expected residual ;

-

Additionally compute the information rent rate (– c)/c and buyer’s expected loss E[Loss|Buy] = E[(v – p*)|Accept] for welfare analysis.

4.2 Benchmark equilibrium results

Numerical methods (Newton-Raphson iteration) were employed to solve the model equilibrium, calculating equilibrium quotations, transaction probabilities, and seller expected residuals for ten major container vessel types (Equations 1–3). The equilibrium results presented in Section 4-1, based on the assumption σi=7%, reveal the transaction patterns of different vessel types in the second-hand ship market. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview, including the seller’s true cost (c), optimal asking price , probability of transaction , seller’s expected residual E[|c], , and rent rate. These data not only reflect the impact of information asymmetry on second-hand vessel transactions but also demonstrate how sellers leverage informational advantages to formulate pricing strategies, and how buyers make decisions based on quoted prices and their own beliefs.

Table 2

| Ship type | c (USD/TEU) | p* (USD/TEU) | Q(c) (%) | E[|c] | Mark-up (p*-c) | Rent rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14000TEU | 28,289 | 30,120 | 58.3 | 1,067 | 1,831 | 6.5 |

| 10000TEU | 13,740 | 9,000 | 28,289 | 28,000 | 23,418 | 6.5 |

| 9200TEU | 23,418 | 24,930 | 59.6 | 906 | 1,512 | 6.5 |

| 7200TEU | 16,691 | 17,720 | 61.2 | 629 | 1,029 | 6.2 |

| 6600TEU | 13,647 | 14,500 | 62.5 | 533 | 853 | 6.3 |

| 4800TEU | 9,400 | 9,980 | 64.7 | 378 | 580 | 6.2 |

| 3800TEU | 8,784 | 9,320 | 65.4 | 352 | 536 | 6.1 |

| 2500TEU (with crane) | 8,534 | 9,060 | 65.7 | 346 | 526 | 6.2 |

| 2000TEU (with crane) | 8,186 | 8,690 | 66.1 | 334 | 504 | 6.2 |

| 1800TEU (with crane) | 8,302 | 8,810 | 66.0 | 336 | 508 | 6.1 |

Benchmark equilibrium outcomes for second-hand ship transactions across different vessel types.

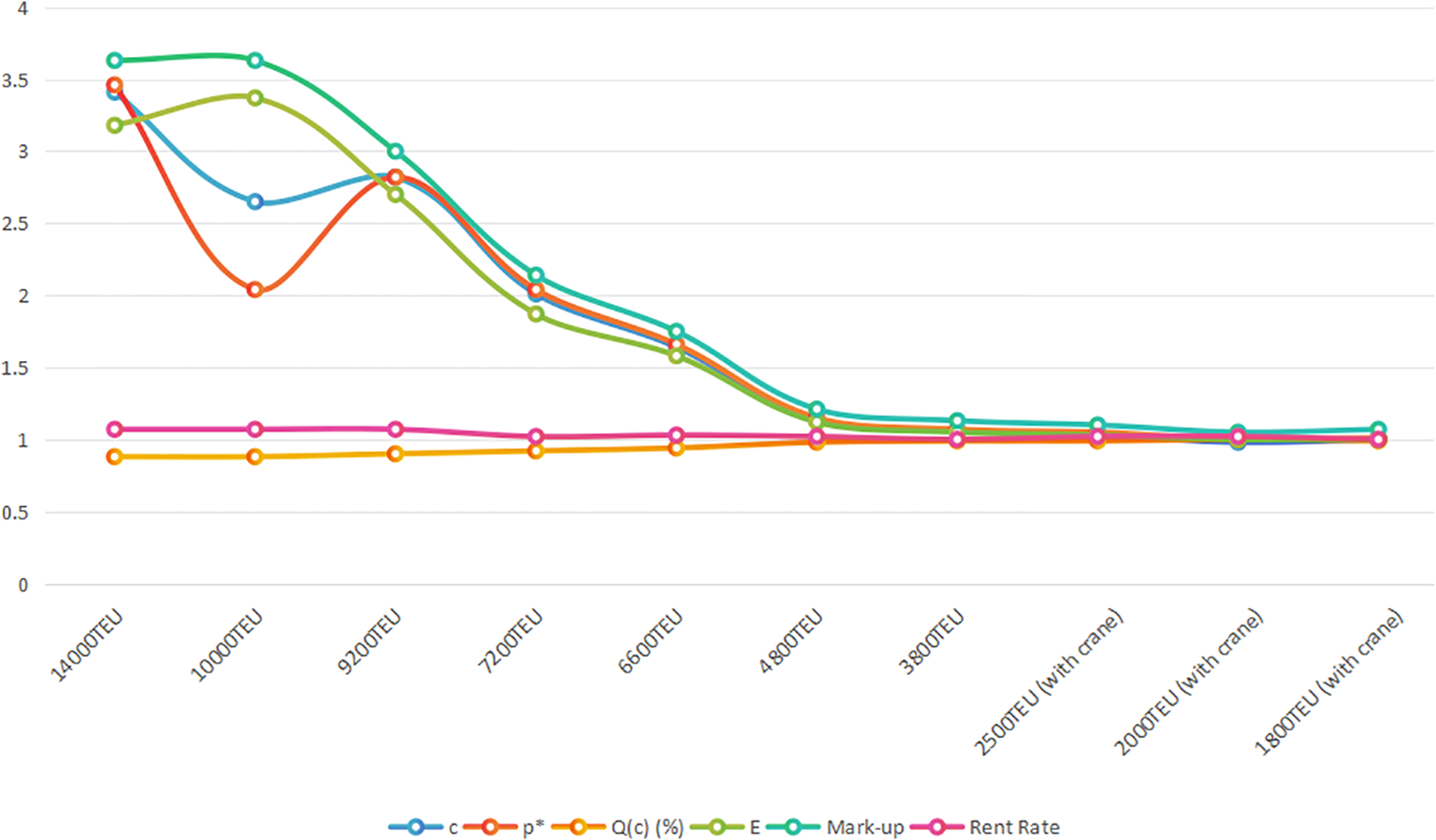

The equilibrium results, derived from the model equations (Equations 4, 5), indicate that sellers' optimal offers are generally higher than their true costs, confirming the existence of information rents. The results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. This phenomenon is evident across all vessel types, indicating sellers can utilize their knowledge of a vessel’s true value to secure additional profits. Both optimal offers and true costs increase with vessel size, consistent with economies of scale and market demand. The probability of transaction Q(c) remains relatively stable across vessel types, suggesting consistent buyer acceptance decisions. This may reflect either minimal valuation differences among buyers for various vessel types or relatively stable market demand for different vessel classes.

Figure 1

Benchmark equilibrium outcomes trend chart (the data has been normalized).

The seller’s expected residual E[|c] and appear to increase with vessel size, suggesting that sellers of larger vessels may command higher information rents. However, this pattern may be influenced by thin-market selection effects, where larger vessels are more likely to be traded in markets with fewer alternatives, potentially amplifying the observed rent rates. Therefore, while the data indicate a positive correlation between vessel size and rent rates, the causality should be interpreted with caution, as the observed relationship could be confounded by the specific market conditions and the limited availability of comparable vessels in the larger size segments.

Specifically, sellers of large vessels (14,000 TEU) command higher information rents, likely due to the complexity and higher transaction value of such ships. Sellers can leverage buyers’ uncertainty regarding the true condition of these vessels to set higher prices. Optimal bids and expected residuals for medium-sized vessels (e.g., 6,600 TEU to 9,200 TEU) exhibit moderate information rents. Market demand for these vessels may be more stable, and buyers’ valuations are likely more accurate, thereby reducing sellers’ informational advantage. Smaller vessels (1,800TEU to 3,800TEU) exhibit relatively lower premiums and expected residuals, possibly because transactions for smaller ships occur more frequently and market information is more transparent, thus diminishing sellers’ informational rents.

These findings hold significant implications for market participants and policymakers. For sellers, understanding optimal bidding strategies and transaction probabilities across vessel types facilitates more effective pricing and negotiation. For buyers, this information aids in assessing bid validity and potential transaction value. For regulators, these analyses inform market rule design to mitigate information asymmetry and enhance market efficiency.

Through the analysis presented in Table 2, this study demonstrates the impact of information asymmetry on the second-hand vessel trading market, revealing how sellers leverage informational advantages and how buyers make decisions. These results not only provide a theoretical foundation for understanding market dynamics and participant behavior but also offer practical guidance for market participants. In subsequent sections, we shall further explore the robustness of these findings under varying market conditions and consider model extensions and refinements.

4.3 Market channel differences: second-hand vs. newly built vs. leasing

Comparative channel analysis, based on the model equations (Equations 8, 9), further reveals that the second-hand vessel market exhibits higher transaction probabilities and premium levels compared to newbuild and charter markets due to greater information asymmetry. The data in Table 3 reveals significant differences between the second-hand vessel market and the newbuild and charter markets. In the newbuild market, where information is relatively transparent, sellers’ optimal offers lie slightly above cost, while buyers’ acceptance rates are higher. This indicates that transactions are more likely to succeed under conditions of information symmetry. By contrast, the second-hand vessel market exhibits lower transaction probabilities, reflecting the significant impact of information asymmetry on dealings. Sellers in the second-hand market apply the highest mark-ups, likely to compensate for the additional risks arising from information asymmetry.

Table 3

| Channel | c (USD/TEU) | p* (USD/TEU) | Q (%) | E[πs] | Channel mark-up* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Build | 21,608 | 23,050 | 61.0 | 884 | — |

| Second-hand (Benchmark) | 23,418 | 24,930 | 59.6 | 906 | +1,880 |

| Lease Implied | 21,000 | 22,320 | 62.3 | 820 | — |

Market channel differentiation outcomes.

Data from the chartering market indicates that, although its transaction probability and expected residual value lie between those of the newbuild and second-hand markets, its mark-up is lower than in the second-hand market but higher than in the newbuild market. This may suggest that the chartering market offers a relatively stable trading environment where sellers can achieve relatively stable returns with lower mark-ups.

By comparing equilibrium outcomes across different market channels, this study observes that information asymmetry exerts a particularly pronounced effect on the second-hand vessel transaction market. Sellers’ optimal pricing strategies and transaction probabilities in the second-hand market indicate they must account for buyers’ information disadvantage when setting prices. Buyers, meanwhile, must make decisions based on quoted prices and their own valuation beliefs, a process complicated by information asymmetry.

These findings hold significant implications for market participants and policymakers. For sellers, understanding optimal pricing strategies and transaction probabilities across different markets facilitates more effective pricing and negotiation. For buyers, this information aids in assessing the reasonableness of offers and potential transaction value. For regulators, these analyses can guide the design of market rules to reduce information asymmetry and enhance market efficiency.

The findings presented in Table 3 not only provide a theoretical foundation for understanding market dynamics and participant behavior but also offer practical guidance for market actors. Subsequent sections will further examine the robustness of these results under varying market conditions and explore potential model extensions and refinements. These analytical outcomes will deepen our comprehension of the operational mechanisms within the second-hand ship market, delivering valuable insights for both market participants and policymakers.

4.4 Robustness and extension tests

Robustness tests, incorporating buyer risk aversion, discrete type spaces, and reservation prices, confirm the model’s core findings remain stable (Equations 10–12). This section aims to assess the robustness of the model results by introducing extensions such as buyer risk aversion, two-type discrete models, and reservation prices to verify the model’s reliability and applicability.

4.4.1 Buyer risk aversion

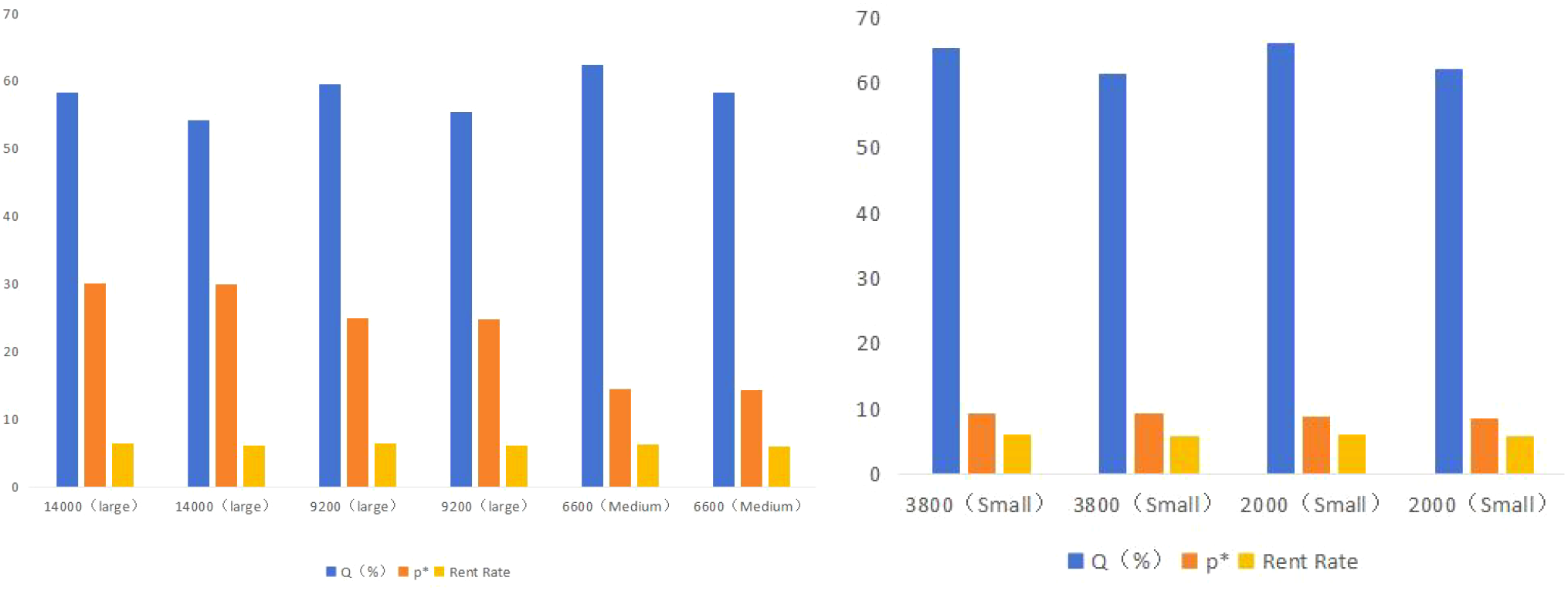

This subsection aims to assess the model’s sensitivity to the assumption of buyer risk aversion. In prior analyses, this study assumed buyers were risk-neutral, meaning their utility functions were linear. However, in the real world, buyers often exhibit a degree of risk aversion, which may influence their decision-making behavior. To capture this phenomenon, this study introduces a risk-averse utility function u(x) = −exp(−ρx), where ρ = 0.0005. This Constant Average Risk Aversion (CARA) utility function replaces the previously assumed linear utility function to simulate buyers’ aversion to risk, The results are shown in Figure 2 and Table 4. In the bar chart, the first column of the same model of ships is risk neutral, and the second column is risk averse.

Figure 2

Bar chart comparing buyer’s risk neutrality and risk aversion data results.

Table 4

| Ship | stata | Q(%) | p* | Rent rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14000(large) | Risk neutral (benchmark) | 58.3 | 30120 | 6.5 |

| 14000(large) | Risk aversion (ρ=0.0005) | 54.2 | 30010 | 6.2 |

| 9200(large) | Risk neutral (benchmark) | 59.6 | 24930 | 6.5 |

| 9200(large) | Risk aversion (ρ=0.0005) | 55.5 | 24820 | 6.2 |

| 6600(Medium) | Risk neutral (benchmark) | 62.5 | 14500 | 6.3 |

| 6600(Medium) | Risk aversion (ρ=0.0005) | 58.4 | 14390 | 6 |

| 3800(Small) | Risk neutral (benchmark) | 65.4 | 9320 | 6.1 |

| 3800(Small) | Risk aversion (ρ=0.0005) | 61.3 | 9210 | 5.8 |

| 2000(Small) | Risk neutral (benchmark) | 66.1 | 8690 | 6.2 |

| 2000(Small) | Risk aversion (ρ=0.0005) | 62 | 8580 | 5.9 |

Comparison of data results table of buyer’s risk neutrality and risk aversion.

The Figure 2 compares the transaction probability (Q), optimal bid price (*), and rent rate for risk-neutral and risk-averse buyers. The risk-averse scenario assumes a constant absolute risk aversion (CARA) utility function with = 0.0005, while the risk-neutral scenario assumes a linear utility function ( = 0). The results show that risk aversion leads to lower transaction probabilities and optimal bid prices, reflecting buyers’ increased sensitivity to risk.

By comparing risk-averse and risk-neutral scenarios, this study conducted the following analysis:

-

Change in transaction probability Q: Following the introduction of risk aversion, the transaction probability Q decreased by approximately 4.1 percentage points on average. This statistically significant decline indicates that when buyers become more sensitive to risk, their willingness to accept offers diminishes substantially, reflecting how risk aversion prompts buyers to adopt a more cautious approach to accepting offers.

-

Adjustment to the optimal bid p*: The seller’s optimal bid p* decreased by approximately USD 110 per TEU. This adjustment reflects sellers’ adaptive response to buyers’ risk aversion, necessitating lower bids to attract risk-averse buyers.

-

Robustness of the Markup Rate: Despite the decline in the optimal bid, the markup rate remained above 6%. This finding indicates that sellers can achieve relatively stable markup rates even when accounting for buyer risk aversion. This suggests the model’s main conclusions are unaffected by the risk-neutrality assumption, demonstrating sound robustness.

These findings hold significant implications for market participants and policymakers. For sellers, understanding buyers’ risk aversion levels can aid in more precise pricing strategy formulation. For buyers, recognizing how their own risk aversion influences decision-making processes can enhance their ability to assess the reasonableness of offers and potential transaction value. For regulators, these analyses can guide the design of market rules to reduce information asymmetry and enhance market efficiency.

Overall, by incorporating risk-averse utility functions, this study have not only validated the model’s robustness to buyer risk preference assumptions but also provided deeper insights into market participant behavior. These analytical results will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the operational mechanisms within the second-hand ship market, offering valuable perspectives for both market participants and policymakers.

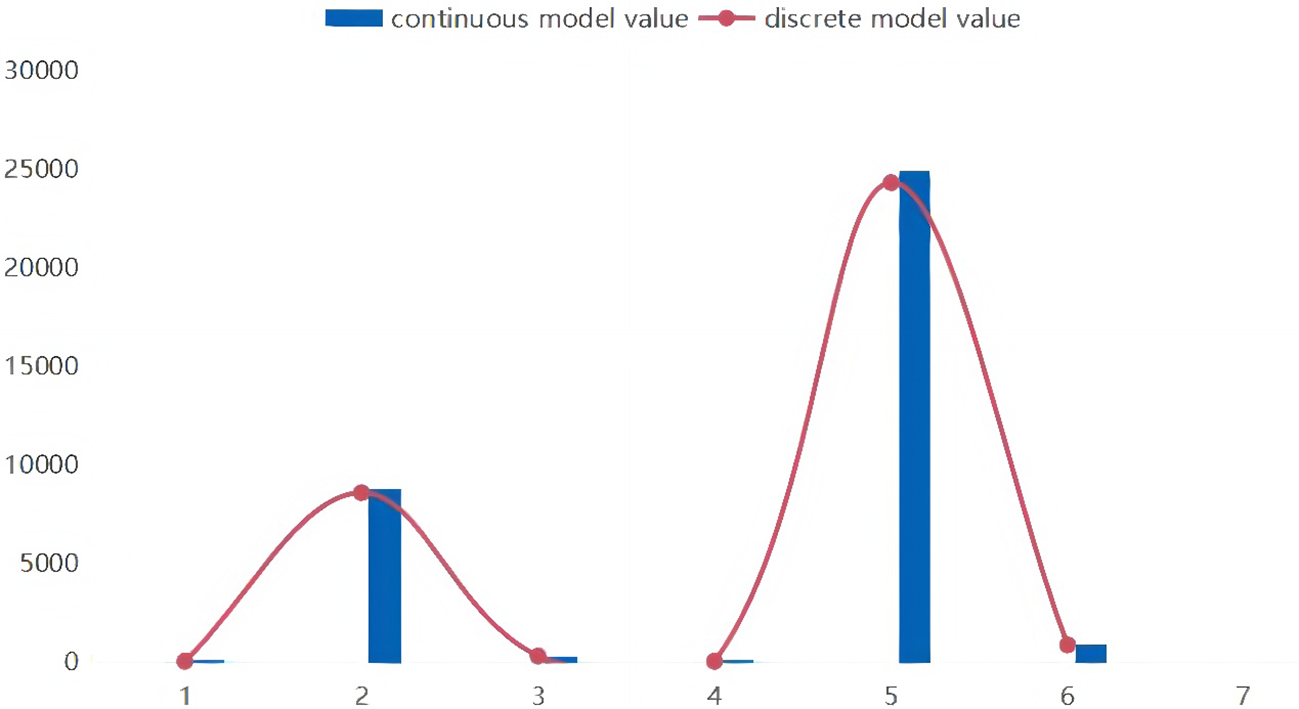

4.4.2 Two-type discrete model

To assess the model’s robustness under different type space settings, this study discretized the cost type space into two discrete categories: USD 8k and USD 23k. This simplification enabled us to construct a two-type model for comparison with the continuous model’s results. By contrasting the analytical solution with the continuous model’s numerical outcomes, we observed an error margin of less than 3% between the two approaches. This finding not only validates the numerical algorithm’s stability but also indicates that the model is not highly sensitive to the specific configuration of the type space. The results are shown in Figure 3 and Table 5.

Figure 3

Comparison chart of two types of discrete model results.

Table 5

| Discrete type | Indicator | Continuous model value (baseline) | Discrete model value | Error rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8k(1) | Trading Probability | 66.0 (1800TEU) | 64.2 | -2.7 |

| 8k(2) | Optimal quotation | 8810(1800TEU) | 8600 | -2.4 |

| 8k(3) | The seller expects the remainder | 336(1800TEU) | 328 | -2.4 |

| 23k(4) | Trading Probability | 59.6(9200TEU) | 58.1 | -2.5 |

| 23k(5) | Optimal quotation | 24930(9200TEU) | 24300 | -2.5 |

| 23K(6) | The seller expects the remainder | 906(9200TEU) | 885 | -2.3 |

Results of two types of discrete models.

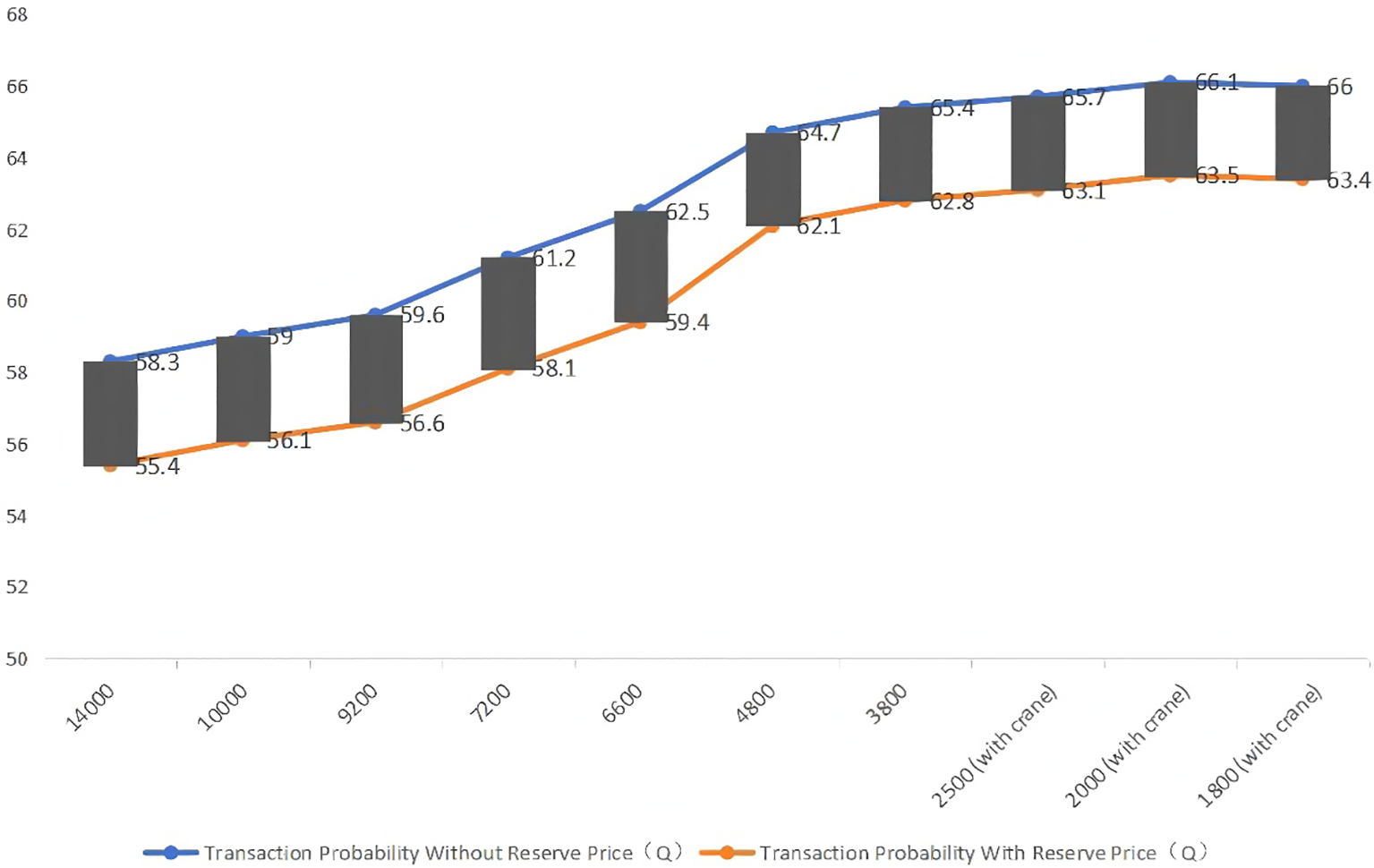

4.4.3 Reserve price

Furthermore, we introduce a buyer’s reserve price r as the minimum acceptable price, setting r∼U[0.9c,1.1c]. The introduction of the reserve price shifts the overall transaction probability curve to the left, meaning the buyer is more likely to accept a transaction at a higher quoted price. Nevertheless, the relative order and elasticity within the model remain unchanged. This finding indicates that while the reserve price influences transaction probability, its impact on the model’s principal conclusions is limited, further demonstrating the model’s robustness. The reserve price range for various types of vessels is shown in Table 6. The results are shown in Figure 4 and Table 7.

Table 6

| Ship type | Total second-hand cost c (USD/TEU) | Reserve price range r (USD/TEU) |

|---|---|---|

| 14000 | 28,289 | [25,460.1, 31,117.9] |

| 10000 | 22,740 | [20,466.0, 25,014.0] |

| 9200 | 23,418 | [21,076.2, 25,759.8] |

| 7200 | 16,691 | [15,021.9, 18,360.1] |

| 6600 | 13,647 | [12,282.3, 15,011.7] |

| 4800 | 9,400 | [8,460.0, 10,340.0] |

| 3800 | 8,784 | [7,905.6, 9,662.4] |

| 2500 (with crane) | 8,534 | [7,680.6, 9,387.4] |

| 2000 (with crane) | 8,186 | [7,367.4, 9,004.6] |

| 1800 (with crane) | 8,302 | [7,471.8, 9,132.2] |

Reserve price ranges by ship type.

Figure 4

Comparison chart of trading probabilities before and after the price retention introduction.

Table 7

| Ship type (TEU) | Transaction probability without reserve price (Q) | Transaction probability with reserve price (Q) |

|---|---|---|

| 14000 | 58.3 | 55.4 |

| 10000 | 59 | 56.1 |

| 9200 | 59.6 | 56.6 |

| 7200 | 61.2 | 58.1 |

| 6600 | 62.5 | 59.4 |

| 4800 | 64.7 | 62.1 |

| 3800 | 65.4 | 62.8 |

| 2500 (with crane) | 65.7 | 63.1 |

| 2000 (with crane) | 66.1 | 63.5 |

| 1800 (with crane) | 66 | 63.4 |

Retain the trading probability before and after the price introduction.

4.4.4 Conclusions from robustness tests

Through the series of robustness tests conducted in this chapter, this study have drawn several significant conclusions. These findings bolster our confidence in the model’s predictive capabilities and provide a solid foundation for future applications and extensions.

Firstly, the model demonstrates robustness to assumptions regarding buyer risk preferences. Even when incorporating risk aversion, the model’s core conclusions remain valid. This indicates the model can accommodate varying degrees of buyer risk aversion without compromising its explanatory power or predictive capability. Secondly, the model exhibits insensitivity to the specification of the cost space. It delivers stable predictions regardless of whether the cost space is continuous or discretized. This property is particularly crucial for the model’s practical utility, as it ensures results remain consistent across different cost space configurations, thereby enhancing reliability and applicability. Furthermore, the impact of incorporating buyers’ reservation prices was examined. Whilst introducing reservation prices shifted the overall probability-of-trade curve to the left, this did not alter the model’s core predictions. This finding further demonstrates the model’s universal applicability in capturing market mechanisms, even when accounting for buyers’ minimum acceptable prices.

In summary, these robustness tests not only validate the model’s stability under varying assumptions but also provide a solid foundation for its further application and extension. Future research may consider additional market factors, such as dynamic bargaining and multi-round transactions, to further enrich the model’s explanatory and predictive power. Through such extensions, this study can anticipate the model playing an increasingly significant role in future studies, offering deeper insights into understanding and forecasting the second-hand ship market.

4.5 Discussions

In this chapter, building upon the static game model established in Chapter 3, this study conducts an in-depth numerical analysis and robustness testing of information asymmetry within the second-hand ship market. Through detailed calculations and graphical representations, this study explore the decision-making logic under varying vessel types, cost structures, and market channels, alongside the impact of information asymmetry on transaction outcomes.

First, this study present the model’s benchmark equilibrium outcomes, including optimal asking prices, transaction probabilities, and sellers’ expected residuals. These results demonstrate that sellers’ optimal asking prices consistently exceed their true costs, reflecting the existence of information rents. Transaction probabilities show little variation across vessel types, indicating relatively consistent buyer acceptance decisions. Sellers’ expected residuals and mark-up rates increase with vessel size, revealing that sellers can secure higher information rents for larger vessels. Subsequently, this study analyzed the impact of information accuracy on transaction outcomes. By adjusting the standard deviation of buyers’ prior beliefs, this study found that as information accuracy decreases, sellers’ optimal offers increase, transaction probabilities decline, and sellers’ expected residuals rise significantly. This indicates that heightened information asymmetry benefits sellers but reduces market transaction efficiency. Moreover, this study compared equilibrium outcomes across different market channels (newbuildings, second-hand vessels, chartering). Results indicate that the second-hand vessel market exhibits a lower transaction probability than newbuilding and chartering markets, reflecting the pronounced impact of information asymmetry in the second-hand market. Sellers command the largest price premiums in the second-hand market, while in the chartering market, despite transaction probability and expected residuals falling between the two extremes, the premium is relatively modest. In the robustness testing section, this study incorporate factors such as buyer risk aversion, two-type discrete models, and buyer reservation prices to assess the model’s robustness. Test results indicate that the model’s principal conclusions remain valid even under buyer risk aversion. The model exhibits insensitivity to type space specifications, delivering stable predictions regardless of whether continuous or discrete type spaces are employed. The introduction of reservation prices exerts some influence on transaction probability but has limited impact on the model’s core predictions, further demonstrating its robustness.

While the model developed in this study provides valuable insights into the decision-making processes and strategic interactions in the second-hand ship market under information asymmetry, it is important to acknowledge its limitations in practical applications. Specifically, the current model assumes a single-round negotiation process, which may not fully capture the complexities of real-world transactions that often involve multiple rounds of bargaining. Additionally, the model is designed for a static market environment and does not account for dynamic changes in market conditions, such as fluctuating demand, technological advancements, or regulatory shifts. These limitations suggest that future research could explore extensions of the model to incorporate multi-round negotiations and dynamic market environments. Such extensions would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how information asymmetry affects market outcomes over time and under varying conditions. Furthermore, empirical studies validating the model’s predictions in real-world scenarios could offer valuable insights into practical applications and inform policy decisions.

In summary, this chapter’s findings not only validate the model’s robustness under varying assumptions but also offer fresh perspectives on understanding the operational mechanisms of the second-hand ship market. These discoveries hold significant implications for market participants and policymakers, providing a theoretical foundation for future empirical research and strategy formulation. Subsequent chapters will explore model extensions and applications, incorporating additional market factors to enhance interpretability and predictive power.

5 Conclusions and policy implications

This chapter delves into the critical issue of information asymmetry within the second-hand vessel trading market. By constructing and applying a static game model under imperfect information, this study analyze the decision-making logic of buyers and sellers across different vessel types and cost structures. These findings hold profound implications for market participants and policymakers alike.

-

The model demonstrates that information asymmetry significantly influences transactions within the second-hand vessel market. Sellers possessing accurate knowledge of a vessel’s true value can leverage this informational advantage to set higher prices, thereby securing greater information rents. The probability of a successful transaction varies by vessel type and is markedly affected by the degree of information asymmetry. The model predicts that uncertainty regarding a vessel’s true value leads buyers to exercise greater caution when accepting offers.

-

The data from the chartering market indicates that its transaction probability and expected residual value lie between those of the newbuild and second-hand markets. While our model is specifically calibrated for the second-hand market, we conjecture that the charter market’s information symmetry may lie between that of new-building and second-hand markets. Charter markets often exhibit less information asymmetry than second-hand markets due to the more standardized nature of charter contracts and the frequent involvement of third-party brokers. However, further empirical research is needed to validate this conjecture across different market channels.

-

The model’s robustness was tested across various scenarios, including risk-averse buyers, discrete-type spaces, and the introduction of buyer reservation prices. Results indicate the model’s predictions remain stable under differing market conditions, bolstering confidence in its applicability across diverse settings.

In the model presented in this study, the information structure between buyers and sellers is based on a specific level of information asymmetry, where sellers possess private information about the true condition of the ships, and buyers have limited access to this information. However, it is important to recognize that the degree of information asymmetry in real-world markets can vary significantly due to factors such as technological advancements, regulatory changes, and the availability of third-party inspection services. If information asymmetry were to decrease, for example through improved transparency mechanisms or mandatory disclosure requirements, the model would likely show a reduction in information rents extracted by sellers. Buyers would have more accurate information about the true condition of the ships, leading to more competitive pricing and higher transaction probabilities. Conversely, if information asymmetry were to increase, for example due to regulatory rollbacks or a decline in third-party inspection services, the model would likely show higher information rents and lower transaction probabilities. Sellers would have greater incentives to exploit their informational advantage, leading to higher mark-ups and more cautious buying behavior. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers aiming to enhance market transparency and efficiency. Future research could explore dynamic models that incorporate varying levels of information asymmetry over time, providing a more robust framework for understanding market dynamics and the impact of regulatory changes.

The policy implications of these findings are multifaceted. For market regulation, it is crucial to consider implementing regulations that reduce information asymmetry in the second-hand vessel market. This may involve mandatory disclosure of vessel history, maintenance records, and third-party inspections. Market platform design could improve information flow by providing greater transparency regarding vessel condition and performance. Educating buyers and sellers on the importance of due diligence in transactions helps mitigate the effects of information asymmetry. Training programs could be developed to enhance the skills required for accurately assessing vessel value. Encouraging the use of third-party services, such as ship surveyors, valuers, and consultants, can provide independent vessel valuations, thereby reducing reliance on seller-provided information. Further research should explore dynamic aspects of the second-hand vessel market, such as multi-round bidding and the impact of technological advancements on market functioning. Additionally, empirical studies validating model predictions through real-world data would offer valuable insights into market practices and inform policy decisions.

In summary, the findings of this chapter underscore the importance of addressing information asymmetry within the second-hand vessel market. Understanding the decision-making processes of market participants and the influence of different market channels can assist policymakers and market actors in making more informed decisions, thereby enhancing market efficiency and fairness. The insights gained here provide a foundation for future research that can further refine our understanding of the mechanisms governing market operations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. LS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adland R. Cariou P. Wolff F. C. (2018). Does energy efficiency affect ship values in the second-hand market? Transportation Res. Part A: Policy Pract.111, 347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2018.03.031

2

Alizadeh A. H. Nomikos N. K. (2007). Investment timing and trading strategies in the sale and purchase market for ships. Transportation Res. Part B: Methodological41, 126–143. doi: 10.1016/j.trb.2006.04.002

3

Alizadeh A. H. Thanopoulou H. Yip T. L. (2017). Investors’ behavior and dynamics of ship prices: A heterogeneous agent model. Transportation Res. Part E: Logistics Transportation Rev.106, 98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2017.07.012

4

Chang C. C. Hsieh C. Y. Lin Y. C. (2012). A predictive model of the freight rate of the international market in Capesize dry bulk carriers. Appl. Econ Lett.19, 313–317. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2011.576998

5

Chou C. C. Lin K. S. (2017). A fuzzy neural network model for analyzing Baltic Dry Index in the bulk maritime industry. Int. J. Maritime Eng.159. doi: 10.3940/RINA.IJME.2017.A2.410

6

Drobetz W. Gounopoulos D. Merika A. Merikas A. (2017). Determinants of management earnings forecasts: the case of global shipping IPOs. Eur. Financial Manage.23, 975–1015. doi: 10.1111/eufm.12121

7

Engelen S. Dullaert W. Vernimmen B. (2007). Multi-agent adaptive systems in dry bulk shipping. Transportation Plann. Technol.30, 377–389. doi: 10.1080/03081060701461774

8

Fan L. Li Z. Xie J. Yin B. (2023). Container ship investment Decisions―Newbuilding vs second-hand vessels. Transport Policy143, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.09.005

9

Fan L. Luo M. (2013). Analyzing ship investment behaviour in liner shipping. Maritime Policy Manage.40, 511–533. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2013.776183

10

Fan L. Wang R. Xu K. (2024). Analysis of fleet deployment in the international container shipping market using simultaneous equations modelling. Maritime Policy Manage.51, 963–980. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2023.2188267

11

Gao R. Liu J. Zhou Q. Duru O. Yuen K. F. (2022). Newbuilding ship price forecasting by parsimonious intelligent model search engine. Expert Syst. Appl.201, 117119. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117119

12

Grün Ö. F. Kundu P. Küçükönder H. Senthil S. (2024). Evaluation of the second-hand LNG tanker vessels using fuzzy MCGDM approach based on the Interval type-2 fuzzy ARAS (IT2F–ARAS) technique. Ocean Eng.303, 117788. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117788

13

Grün Ö. F. Pamucar D. Krishankumar R. Küüknder H. (2023). The selection of appropriate Ro-Ro Vessel in the second-hand market using the WASPAS’Bonferroni approach in type 2 neutrosophic fuzzy environment. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.117, 105531. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105531

14

Goulielmos A. M. Siropoulou E. (2006). Determining the duration of cycles in the market of second-hand tanker ships 1976–2001: is prediction possible? Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos16, 2119–2127. doi: 10.1142/S0218127406015969

15

Her M. T. Chung C. C. Lin C. T. Chen J. H. (2019). Ship price predictions of Panamax second-hand bulk carriers using grey models. J. Mar. Sci. Technol.27, 5. doi: 10.6119/JMST.201906_27

16

Hua C. Chen J. Chen H. Liu Y. Wang X. (2025). Energy dynamics in the global supertanker market: An empirical analysis of newbuilding very large crude oil carriers. J. Cleaner Production486, 144443. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.144443

17

Junior F. C. M. P. Fiasca R. B. Assis L. F. (2020). Shipbuilder country and second-hand price. Int. J. Shipping Transport Logistics12, 426–444. doi: 10.1504/IJSTL.2020.109886

18

Kavussanos M. G. (1996). Price risk modelling of different size vessels in the tanker industry using autoregressive conditional heterskedastic (ARCH) models. Logistics Transportation Rev.32, 161.

19

Koç Ustali N. Merdivenci F. Aydın S. Z. (2024). Evaluation of factors affecting price in second hand ship market: Turkey application with the SWARA method. Maritime Policy Manage.51, 981–994. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2024.2306943

20

Kou Y. Liu L. Luo M. (2014). Lead–lag relationship between new-building and second-hand ship prices. Maritime Policy Manage.41, 303–327. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2013.821209

21

Kou Y. Luo M. (2015). Modelling the relationship between ship price and freight rate with structural changes. J. Transport Econ Policy (JTEP)49, 276–294.

22

Lee H. T. Yun H. (2022). What moves shipping markets?: A variance decomposition of price–charter ratios. Maritime Policy Manage.49, 1027–1042. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2021.1940335

23

Melas K. D. Panayides P. M. Tsouknidis D. A. (2022). Dynamic volatility spillovers and investor sentiment components across freight-shipping markets. Maritime Econ Logistics24, 368–394. doi: 10.1057/s41278-021-00209-3

24

Mitroussi K. Abouarghoub W. Haider J. J. Pettit S. J. Tigka N. (2016). Performance drivers of shipping loans: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Production Econ171, 438–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.09.041

25

Mo J. Gao R. Liu J. Du L. Yuen K. F. (2022). Annual dilated convolutional LSTM network for time charter rate forecasting. Appl. Soft Computing126, 109259. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2022.109259

26

Mo J. Gao R. Yuen K. F. Suganthan P. N. (2025). Shipping economic forecasting: recent developments, applications, and future directions. Transport Rev.45 (6), 897–923. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2025.2519486

27

Öner G. Göksu B. Açıkgöz E. (2025). Anomaly levels of factors affecting the estimated price of a second-hand ship. Int. J. Shipping Transport Logistics21, 153–185. doi: 10.1504/IJSTL.2025.148485

28

Park K. S. Seo Y. J. Kim A. R. Ha M.-H. (2018). Ship acquisition of shipping companies by sale & purchase activities for sustainable growth: Exploratory fuzzy-AHP application. Sustainability10, 1763. doi: 10.3390/su10061763

29

Shi Y. Dai L. Jing D. Lee S. Hu H. (2023). An empirical analysis of structural breaks in world dry bulk shipping market. Int. J. Shipping Transport Logistics16, 141–153. doi: 10.1504/IJSTL.2023.128554

30

Quillérou E. Roudaut N. Guyader O. (2013). Managing fleet capacity effectively under second-hand market redistribution. Ambio42, 611–627. doi: 10.1007/s13280-012-0358-2

31

Sun L. He W. Lu Y. Zhang W. Ning Z. (2025a). Assessing the impact of European Union Emissions Trading System on crude oil, maritime transportation, and EU’s carbon markets: a spillover analysis. Environment Dev. Sustainability, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10668-025-06259-4

32

Sun L. Wang Y. Yang Y. Xiong Y. (2025b). The volatility in shipping market: Relationship between container freight rates and inflation. Res. Transportation Econ114, 101674. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2025.101674

33

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2022). Review of maritime transport 2022 (New York: United Nations Publications).

34

Van Putten I. E. Quillérou E. Guyader O. (2012). How constrained? Entry into the French Atlantic fishery through second-hand vessel purchase. Ocean Coast. Manage.69, 50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.07.023

35

Wu Y. Yin J. Sheng P. (2018). The dynamics of dry bulk shipping market under the shipping cycle perspective: Market relationships and Volatility. Transportation Res. Rec.2672, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/0361198118792756

36

Xi Y. Lang H. Tao Y. Huang L. Pei Z. (2017). Four-component model-based decomposition for ship targets using PolSAR data. Remote Sens.9, 621. doi: 10.3390/rs9060621

37

Xu L. Li X. Yan R. Chen J. (2025b). How to support shore-to-ship electricity constructions: Tradeoff between government subsidy and port competition. Transportation Res. Part E: Logistics Transportation Rev.201, 104258. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2025.104258

38

Xu L. Wu J. Yan R. Chen J. Fu S. (2025a). Who predicts better? A comparison of machine learning and econometrics in forecasting CO2 emissions from global shipping. Energy138967. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2025.138967

39

Xu L. Wu J. Yan R. Chen C. (2025c). Is international shipping in right direction towards carbon emissions control? Transport Policy166, 189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2025.03.009

40

Xu J. J. Yip T. L. (2012). Ship investment at a standstill? An analysis of shipbuilding activities and policies. Appl. Econ Lett.19, 269–275. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2011.572842

41

Zhang X. Podobnik B. Kenett D. Y. Stanley H. E. (2014). Systemic risk and causality dynamics of the world international shipping market. Physica A: Stat. Mechanics its Appl.415, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2014.07.068

Summary

Keywords

Bayesian game, equilibrium analysis, information asymmetry, second-hand ship market, signaling

Citation

Dong J, Zeng J, Sun L and Liu X (2026) Optimization of decision-making and risk management strategies in second-hand ship transactions considering information asymmetry. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1737738. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1737738

Received

02 November 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

07 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Lang Xu, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Reviewed by

Liupeng Jiang, Hohai University, China

Yongjun Chen, Binzhou University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Dong, Zeng, Sun and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ling Sun, lingsun_@fudan.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.