Abstract

High-temperature stress threatens sustainable mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) aquaculture by destabilizing the larval microbiome and elevating mortality. This study investigates whether probiotic supplementation can modulate microbial community dynamics and functional assembly to enhance heat resilience. Mud crab larvae across four developmental stages (Zoea I to IV, Z1-Z4) were divided into three groups: a probiotic group (supplemented with Lactobacillus, LAC), an antibiotic group (ANT), and a control group (CK). The microbial community was analyzed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We then calculated α- and β-diversity indices, constructed co-occurrence networks, and inferred functional profiles using PICRUSt2 to assess the structural and functional responses to the treatments. The larval microbiome exhibited stage-specific structural shifts. Although the LAC group showed a significant reduction in α-diversity at the Z4 stage, it demonstrated higher temporal stability in community structure compared to the CK and ANT groups. Co-occurrence network analysis revealed that LAC simplified inter-taxa relationships by lowering modularity and increasing negative interactions, whereas ANT formed a more modular but less connected network. Deterministic processes dominated the functional assembly. The microbiota in the LAC group was significantly associated with enhanced carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, while the ANT group up-regulated pathways related to stress response and antibiotic resistance. Our results demonstrate that probiotic Lactobacillus can remodel the microbial ecology of mud crab larvae under thermal stress, promoting a functionally stable and resilient microbiome. These findings provide a mechanistic foundation for employing probiotics to develop temperature-resilient aquaculture practices for S. paramamosain.

1 Introduction

The mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) is one of the most valuable aquaculture crustaceans in China, contributing significantly to coastal economies due to its high market demand and nutritional value (Li et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2025; Wang, 2023). However, the expansion of its commercial farming is severely constrained by inconsistent seed production, primarily caused by the high temperature sensitivity of larval stages. Elevated temperatures can induce severe physiological stress, disrupt larval development, and lead to mass mortality, thus hindering stable year-round seed supply and threatening the sustainability of mud crab aquaculture (Daunde et al., 2026; Liu et al., 2022., Li and Zeng, 1992; Yu et al., 2007). Addressing thermal stress during larval rearing has therefore become a major challenge for achieving sustainable production.

Microbial communities play a crucial role in maintaining environmental stability and host health in aquaculture systems (Li et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2024; Vadstein et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2017). They drive biogeochemical cycling, regulate nutrient fluxes, suppress pathogens through competitive exclusion and antimicrobial compound production, and modulate host immunity by enhancing enzymatic activities (Lu et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2016, 2015). A balanced microbial ecosystem promotes optimal larval development, whereas dysbiosis can trigger opportunistic pathogen outbreaks and impair surviva (Dai et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2007). Increasing evidence suggests that the assembly and succession of larval microbiota exert long-lasting effects on host physiology and resilience (Bledsoe et al., 2018; Burns et al., 2016; Francino, 2014; Panigrahi et al., 2019). Hence, elucidating the ecological dynamics of microbial communities during larval development is critical for improving aquaculture health management.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have gained increasing attention as multifunctional probiotics in aquaculture. They improve water quality by reducing ammonia and nitrite levels, inhibit pathogen proliferation through bacteriocin production, enhance digestion by stimulating enzyme activity, and strengthen innate immunity and stress tolerance (Figueras et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2024). In mud crab larviculture, LAB supplementation has been reported to improve larval survival and growth while modulating the microbial community structure toward a more beneficial configuration (Li et al., 2021). Despite these promising outcomes, probiotic efficacy is context-dependent and varies with strain composition, dosage, environmental parameters, and developmental stages (Figueras et al., 2022). Under high-temperature conditions, these interactions become even more complex, potentially reshaping microbial networks and altering probiotic performance.

Nevertheless, the ecological mechanisms by which LAB influence microbial community assembly under thermal stress remain poorly understood. Recent larval-stage studies in crustaceans have revealed that microbial community assembly is jointly shaped by deterministic (niche-based) and stochastic (neutral) processes, and that their relative importance shifts across developmental stages (Wang et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2026). Environmental stress, such as elevated temperature, tends to strengthen deterministic selection by filtering thermotolerant and host-associated taxa. In contrast, stable rearing conditions promote higher stochasticity and microbial diversity.

LAB supplementation has been reported to enhance microbial network complexity and stability, fostering beneficial taxa while suppressing opportunistic pathogens (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2024a). These probiotics can also alter community function by enriching metabolic pathways related to nutrient cycling and host defense (Li et al., 2021). However, how LAB reshape microbial co-occurrence networks and shift assembly processes under high-temperature stress in mud crab larvae remains unknown. Addressing this question will clarify whether probiotics interventions enhance microbiota resilience through deterministic regulation or network-mediated buffering, providing a mechanistic basis for temperature-tolerant aquaculture systems.

This study aimed to elucidate how lactic acid bacteria (LAB) modulate microbial community dynamics to enhance mud crab larval performance under high-temperature stress. We systematically evaluated larval survival, microbial diversity, community succession, and functional assembly across treatments with LAB, antibiotics, and a control group. Specifically, we (1) quantified larval survival and diversity indices (α- and β-diversity) across developmental stages (Z1–Z4) to assess temporal community variation; (2) characterized taxonomic composition and identified differential ASVs responsive to LAB and antibiotic treatments; (3) constructed co-occurrence networks to explore alterations in microbial interactions and key taxa connectivity under different treatments; and (4) predicted microbial functions and applied a neutral community model to disentangle the relative contributions of stochastic versus deterministic processes in functional gene assembly. Together, these analyses will provide a comprehensive understanding of how LAB influence microbial ecological processes and larval adaptation under thermal stress, offering a framework for optimizing probiotic strategies in sustainable aquaculture.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental design and larval rearing

In this study, we systematically evaluated how lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and antibiotic interventions regulate the assembly and succession of the larval microbiota in the mud crab (S. paramamosain) under high-temperature stress. Healthy first-stage zoea (Z1) larvae were randomly distributed into three experimental groups: a probiotic-treated group (LAC) receiving a commercial LAB supplement per the manufacturer’s protocol (produced by Nuckel Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), an antibiotic-treated group (ANT) exposed to florfenicol at 2 ppm, and an untreated control group (CK). The tripartite design was employed to dissect the role of microbial manipulation under stress, a rationale supported by previous work in crustacean larviculture (Fu et al., 2024). Each treatment was conducted in triplicate, with larvae maintained in 600-L fiberglass tanks (300 L of filtered, aerated seawater) at a density of 12, 000 individuals per tank and fed newly hatched Artemia salina nauplii twice daily. To mitigate potential microbial dysbiosis during the physiologically stressful molting period, both the LAC supplement and florfenicol were administered prophylactically by direct addition to the rearing water prior to each expected molting event (i.e., at the Z1, Z2, and Z3 stages). The experiment was conducted from 2025 July 28 at the Ninghai Experimental Station of the East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China) under natural high-temperature summer conditions. S. paramamosain zoea larvae have an optimal rearing temperature range of 25–30°C (Fu et al., 2024; Li and Zeng, 1992). Sustained water temperatures above 30°C can induce thermal stress in the larvae, significantly increasing mortality risk. During this experiment, water temperatures ranged from 27–30°C in the morning to 30–35°C at noon (Supplementary Figure 1), thereby establishing a defined high-temperature stress environment. The molting times for each stage were recorded and the detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 1. The final survival rate was determined at the end of the Z4 stage.

2.2 Sample collection and processing

Longitudinal sampling was performed across four key developmental stages (Z1–Z4), with larval staging verified microscopically based on appendage morphology and setation characteristics. For microbial community analyses, duplicate samples of 30 individuals were collected from each replicate tank at every stage, resulting in six biological replicates per treatment per developmental stage (two samples × three tanks). Larvae were concentrated using sterile 100-μm nylon mesh, transferred to cryogenic vials, and washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation (5, 000 × g, 5 min, 4°C) to remove transient environmental microorganisms. The cleaned samples were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until nucleic acid extraction.

2.3 Microbial strain characterization and amplicon sequencing

The commercial product used is a multi-strain. Its label indicates core components including Lactobacillus plantarum (≥2×10¹¹ CFU/L), Vc phosphate ester, and ferrous sulfate, with a manufacturer’s recommended dosage of 12 acres per 5-acre pond at a 1-meter water depth. The commercial probiotic formulation used in larval rearing underwent comprehensive microbiological validation prior to use. Lactic acid bacteria were isolated on de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar under anaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, 5% H2). Dominant isolates were purified by three successive streaks, and their taxonomic identities were confirmed through full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the Sanger method. Phylogenetic affiliation of the isolates was determined via BLASTn searches against the NCBI 16S rRNA and Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) databases (Cole et al., 2014). Phylogenetic analysis identified the dominant cultivated isolate as a Lacticaseibacillus casei strain. In addition, the relative abundance of lactic acid bacteria in the larval microbiota was assessed using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to evaluate the potential colonization of administered strains. Subsequent 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of the larval microbiota revealed a more diverse lactic acid bacterial community, with key endogenous members including Lactobacillus acetotolerans, Lactobacillus melliventris, and Lactobacillus casei. The corresponding sequence data for the cultivated isolate are provided in Supplementary File 1.

For larval microbiota profiling, total genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) with mechanical bead-beating to ensure efficient cell lysis. The hypervariable V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified with dual-indexed primers 343F/798R carrying Illumina adapter sequences. Amplicon libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, normalized, and pooled for paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp) on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Raw sequence reads were processed using a standardized bioinformatics pipeline. Adapter and low-quality bases were trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.39 (Bolger et al., 2014), followed by quality filtering (maxExpectedError = 1) and denoising with the DADA2 algorithm to infer exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (Callahan et al., 2016). Chimeric sequences were removed using the consensus method. Taxonomic classification of ASVs was performed against the SILVA v138 reference database (Quast et al., 2012) using a minimum bootstrap confidence threshold of 80%. The raw data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1378350.

2.4 Community diversity and differential abundance analysis

α- and β-diversity analyses of community diversities were conducted in DADA2. α-diversity was quantified using the Shannon, Simpson, and ACE indices. Statistical comparisons among treatments and developmental stages were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis and one-way ANOVA tests (Ostertagova et al., 2014), followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis to identify significant pairwise differences.

Beta-diversity was evaluated based on weighted unifrac distance and Bray Curtis distance matrices and visualized using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). Differences in community composition among treatment groups were evaluated using both analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) (Clarke, 1993) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, implemented with the adonis2 function in the vegan package v2.6-4) with 999 permutations (Oksanen et al., 2007). These analyses were conducted separately for each developmental stage to identify stage-specific treatment effects. Taxonomic composition was profiled at the phylum and genus levels, and stacked bar plots were used to display taxa with an average relative abundance exceeding 0.5% across developmental stages. Differential abundance analysis was performed separately for each developmental stage to compare treatments based on relative abundance data using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests for pairwise comparisons. Taxa with adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered significantly different.

Differentially abundant ASVs were identified using DESeq2 (v1.40.2) (Love et al., 2014). For each developmental stage (Z1–Z4), separate models were constructed to compare LAC vs. CK and ANT vs. CK treatments. ASVs with FDR-adjusted p < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1 were considered significantly differentially abundant. To evaluate treatment-responsive microbial dynamics, significant ASVs were annotated with their corresponding taxonomic affiliations and summarized across developmental stages.

Temporal decay models were used to analyze microbial community dynamics based on Bray-Curtis similarity matrices across three treatments (CK, ANT, LAC) over the developmental stage. Log-linear regression models (log (Community_similarity) ~ Time) were fitted for each treatment. Temporal decay in community similarity was evaluated by ANCOVA with Type III sums of squares (Fox et al., 2012).

2.5 Temporal dynamics and metagenomic prediction

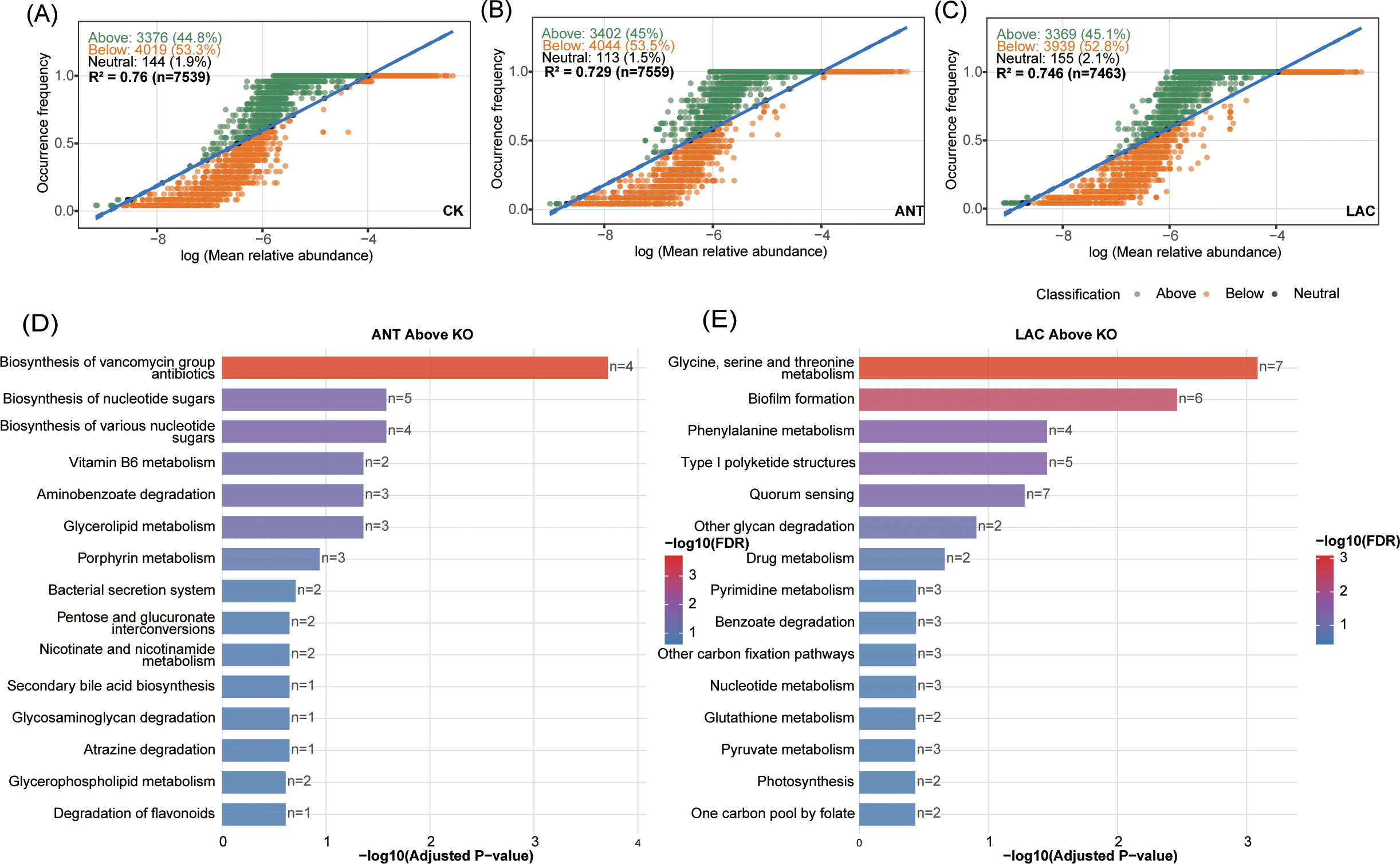

To evaluate the assembly mechanisms of predicted functional genes, functional inference was first performed using PICRUSt2 v2.5.1 (Douglas et al., 2020), which generated KEGG ortholog (KO) profiles at level 3. Based on the predicted KO abundance tables, neutral community model (NCM) analyses were conducted separately for each treatment group (CK, ANT, and LAC). For each KO, occurrence frequency (the proportion of samples with non-zero abundance) and mean relative abundance (row-normalized mean values with an added constant of 1×10−10 to avoid zeros) were calculated. A linear model of occurrence frequency against log10 (mean relative abundance) was then fitted to estimate model fit (R²) and 95% confidence intervals.

KOs were categorized according to their position relative to the confidence limits as Above-neutral (observed frequency above the upper 95% CI), Below-neutral (below the lower 95% CI), or Neutral (within the interval). Treatment-specific Above-neutral KOs were identified using set difference analysis. KEGG pathway enrichment of treatment-specific Above-neutral KOs was performed with clusterProfiler v4.8.1 (Yu et al., 2012), and enrichment results were subsequently summarized for interpretation. All analyses were carried out in R, employing lm for model fitting and ggplot2 for visualization.

2.6 Co-occurrence network analysis and core microbiome identification

Microbial co-occurrence networks were constructed separately for each treatment (CK, ANT, and LAC) based on pairwise correlations of ASV relative abundances in R. Prior to network construction, low-abundance and low-prevalence ASVs (mean relative abundance < 0.1% or occurring in fewer than 5 out of 24 samples) were removed to reduce sparsity and avoid spurious correlations. Pairwise associations were retained if the absolute correlation coefficient exceeded 0.6 and the p-value was below 0.01. The resulting adjacency matrices were exported as GML files and visualized in Gephi v0.10.1 (Bastian et al., 2009).

Network topology was analyzed in Gephi, including the number of nodes and edges, proportion of positive and negative correlations, average degree, degree distribution, average path length, clustering coefficient, modularity, and network density. Key centrality metrics (degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality) were also computed to identify potential keystone taxa. Statistical comparisons of network properties among treatments were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests (p < 0.05).

Keystone species were identified using a dual-threshold approach based on network centrality metrics. ASVs exceeding the treatment-specific median values for both degree and betweenness centrality (CK: degree > 8.0, betweenness > 3.97; ANT: degree > 6.0, betweenness > 4.16; LAC: degree > 5.0, betweenness > 4.70) were defined as keystone taxa. Shared and treatment-specific keystone members were determined by Venn analysis using VennDiagram v1.7.3 (Chen and Boutros, 2011), and the relative abundance dynamics of shared keystone ASVs were compared across developmental stages.

3 Results

3.1 Survival performance and microbial diversity dynamics

A one-way ANOVA indicated a marginally significant difference in survival rates among the treatment groups (F(2, 6) = 3.78, p = 0.087). The LAC group showed a higher mean survival rate (32.2%) compared with the ANT (18.9%) and CK (27.7%) groups, exhibiting a clear increasing trend despite not reaching the conventional threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Figure 2).

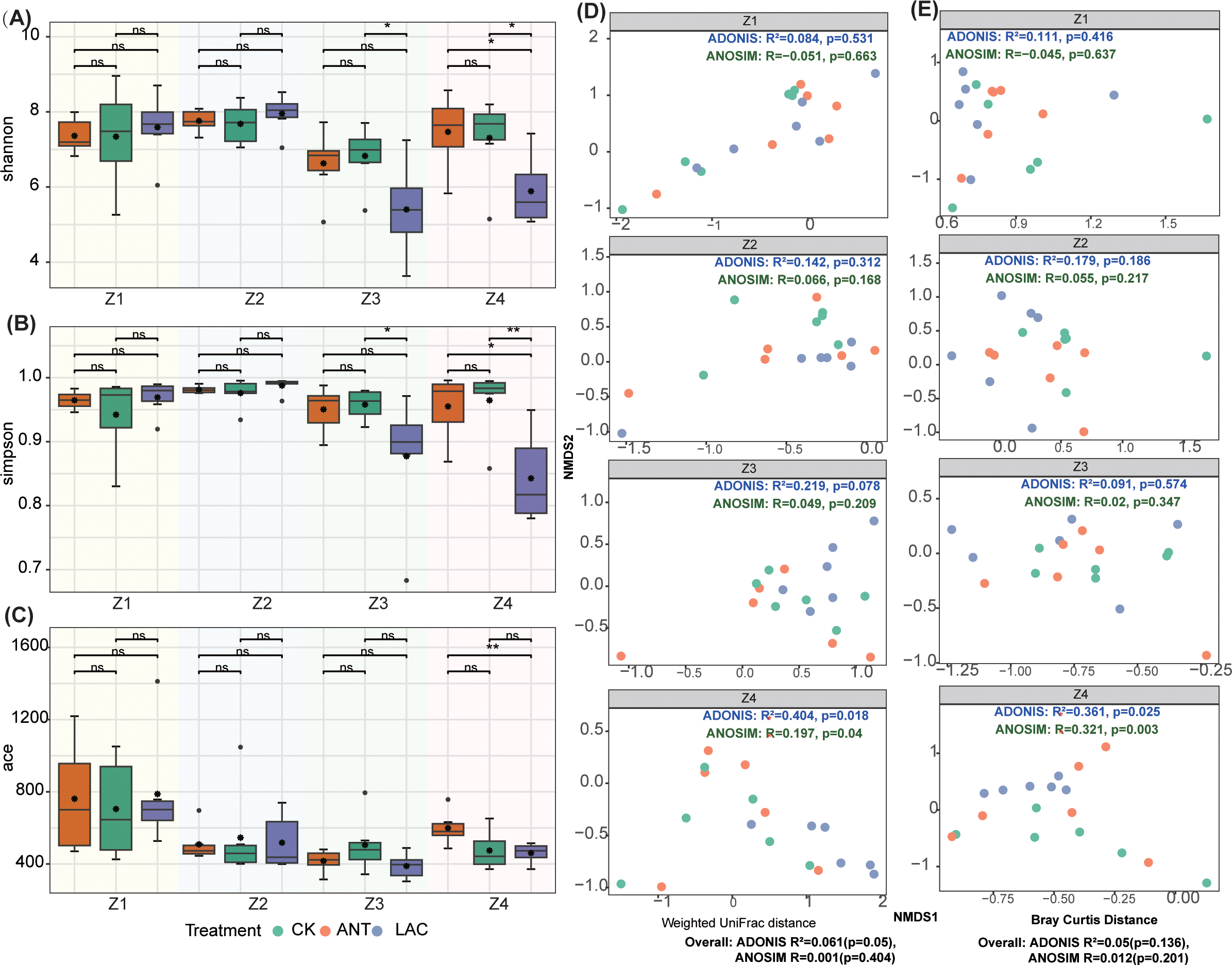

The effects of LAC, ANT, and CK treatments on microbial diversity varied markedly across developmental stages. No significant differences were detected among groups during the early stages (Z1–Z2; p > 0.05) (Figures 1A–C). However, by the Z4 stage, clear treatment effects emerged. The LAC group exhibited significantly lower Shannon diversity than the CK group (p < 0.05) (Figure 1A), while the Simpson index was also significantly reduced in LAC compared with both ANT (p < 0.01) and CK (p < 0.05) (Figure 1B). In contrast, the ACE index was significantly higher in the CK group than in LAC (p < 0.05) (Figure 1C). Collectively, LAC treatment led to a pronounced reduction in microbial diversity during Z4 stages (Figures 1A–C).

Figure 1

Dynamics of microbial community diversity across larval developmental stages (Zoea I–IV) in S. paramamosain among treatment groups. (A–C) Alpha diversity indices of microbial communities in the Control (CK), Lactobacillus (LAC), and Antibiotic (ANT) groups at each larval stage (Z1–Z4), including (A) Shannon, (B) Simpson, and (C) ACE indices. Boxplots show the median and interquartile range. Significant differences within stages, determined by one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests with post-hoc comparisons, are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05, *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001). (D, E) Beta diversity visualized using NMDS ordination based on (D) Weighted UniFrac and (E) Bray–Curtis distances. PERMANOVA (Adonis) and ANOSIM analyses confirmed significant effects of treatment and stage on community structure.

3.2 Community structure succession and temporal dynamics

NMDS analyses based on Bray–Curtis and weighted UniFrac distances revealed that the three treatment groups followed distinct trajectories of microbial community succession across developmental stages (Figures 1D, E). Although no overall differences were detected among treatments, stage-specific variations were evident. During the early stages (Z1–Z3), no significant differences were observed among groups (all p > 0.05) (Figures 1D, E). However, at the Z4 stage, clear inter-group divergence emerged: Bray–Curtis analysis indicated significant community differentiation (ADONIS p = 0.025; ANOSIM p = 0.003), and weighted UniFrac analysis further confirmed these differences (ADONIS p = 0.018; ANOSIM p = 0.040) (Figures 1D, E). Consistently, the NMDS ordination at Z4 visually illustrated a pronounced separation of microbial communities among treatments (Figures 1D, E).

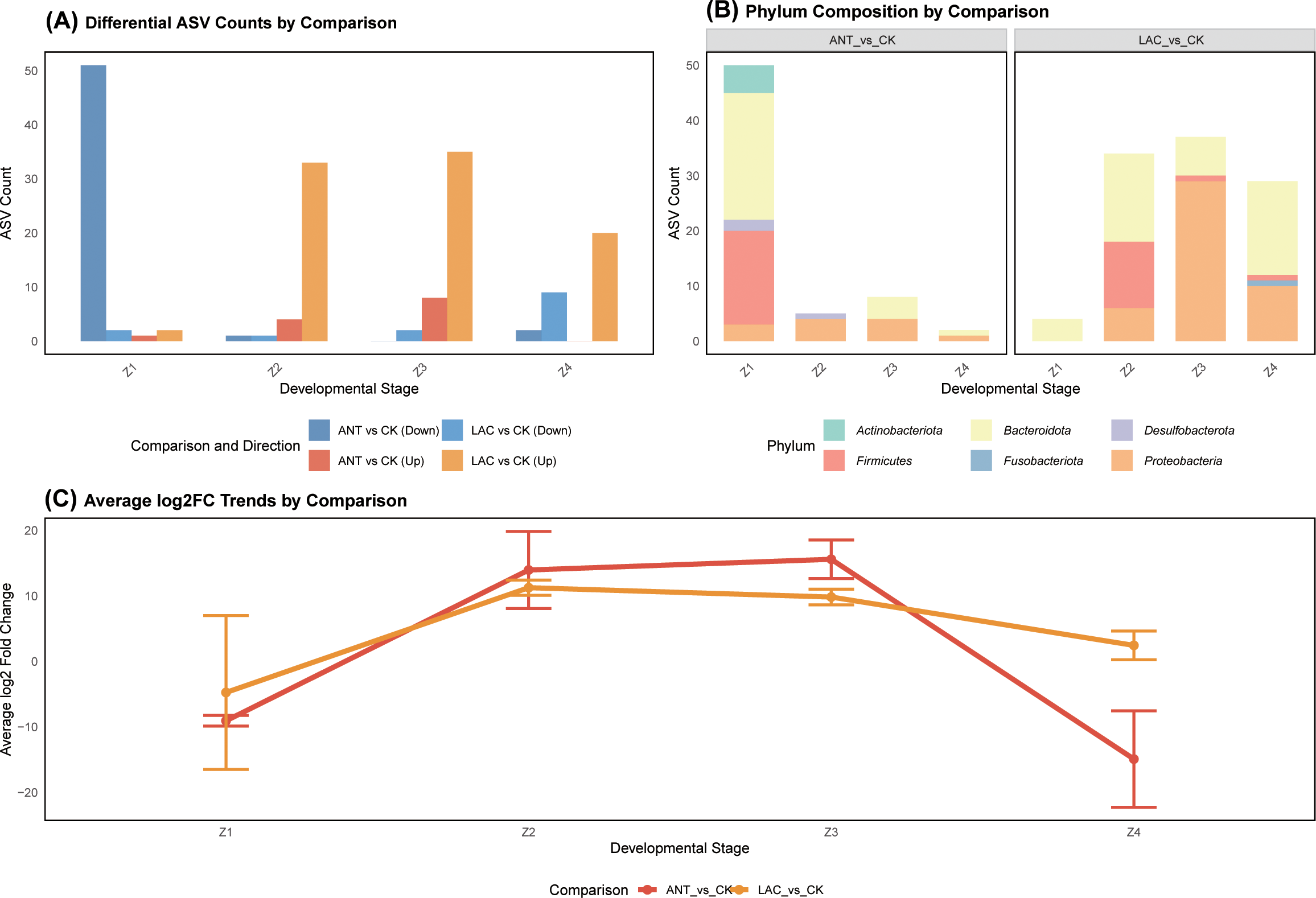

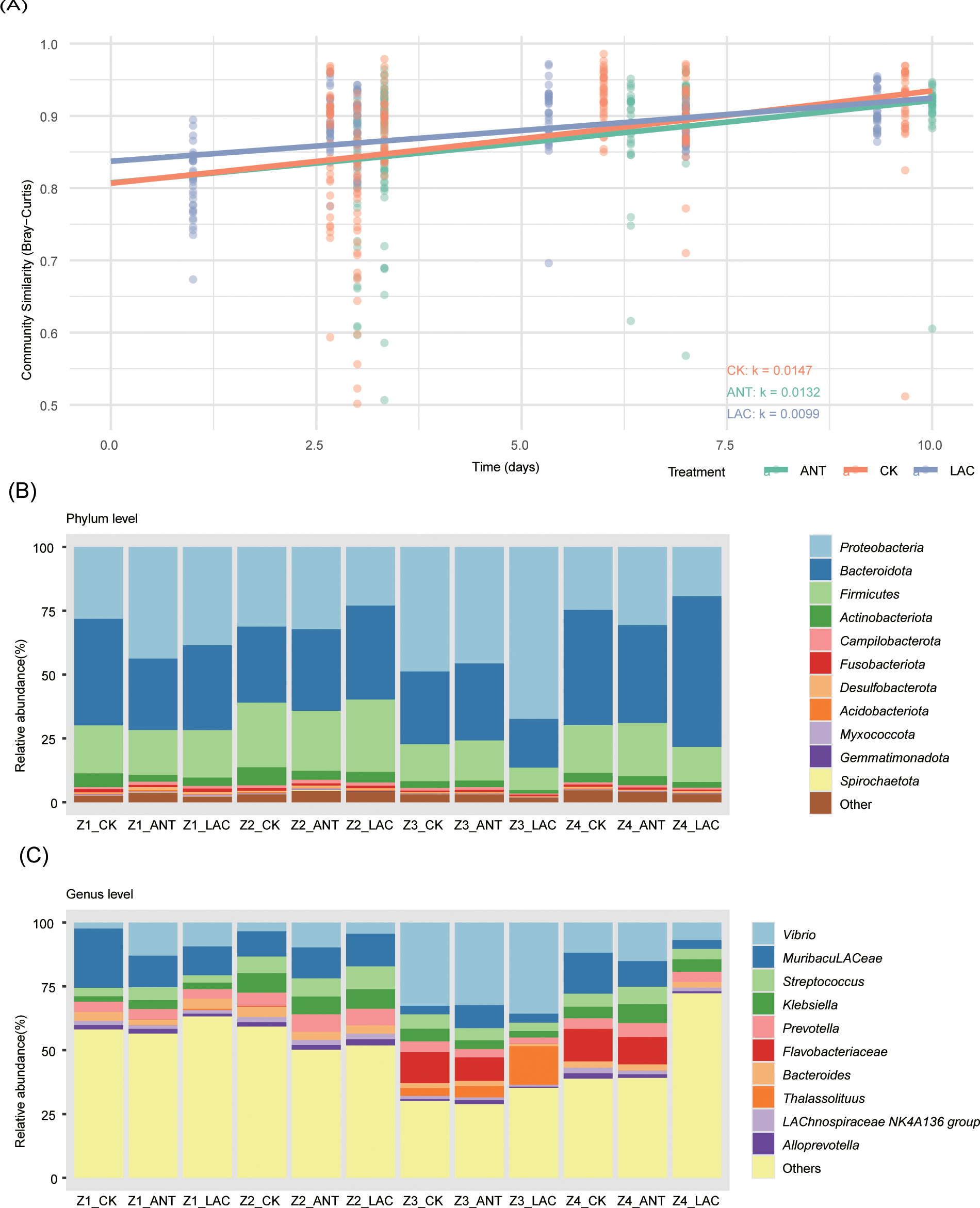

3.3 Community temporal turnover

All treatments exhibited significant temporal decay in community similarity (p < 0.001) (Figure 2A). The estimated decay rates were 0.0147 for CK (F = 26.45, p = 6.10 × 10−7, R² = 0.110), 0.0132 for ANT (F = 23.49, p = 2.41 × 10−6, R² = 0.099), and 0.0099 for LAC (F = 61.09, p = 2.44 × 1013, R² = 0.222) (Figure 2A). ANCOVA indicated a significant main effect of time (F = 42.33, p < 0.001), whereas the time × treatment interaction was not significant (F = 1.20, p = 0.303), suggesting that all treatments followed similar temporal decay patterns.

Figure 2

Temporal succession and taxonomic composition of microbial communities in S. paramamosain larvae among treatment groups. (A) Temporal decay of microbial community similarity across larval development (Z1–Z4) in CK, LAC, and Ant groups. Lines represent fitted regression trends showing temporal turnover. (B) Relative abundance of dominant bacterial phyla, and (C) dominant genera, across larval stages.

3.4 Taxonomic composition and differential abundance

Microbial community profiling revealed that Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota were the predominant phyla across all samples, although their relative abundances varied by developmental stage (Figure 2B). Bacteroidota dominated in the early stages (Z1–Z2), whereas Proteobacteria became markedly enriched in Z3 (67.36%) (Figure 2B). At the genus level, Vibrio was particularly abundant in Z3 (32–36%), while members of Muribaculaceae were more prevalent in Z1 (Figure 2C). Treatment effects were relatively limited and stage-specific: at the phylum level, Bacteroidota showed significant variation only at Z4 (p = 0.015), and at the genus level, Bacteroides exhibited a significant response at Z3 (p = 0.048) (Figures 2B, C).

ANT treatment induced stage-specific shifts in microbial composition, with the most pronounced alterations observed at the Z3 stage (1 ASV up-regulated, 51 down-regulated) (Figure 3A). The responsive ASVs were primarily affiliated with Proteobacteria (across Z1–Z4), Firmicutes (Z1), and Bacteroidota (Z1) (Figure 3B). In contrast, LAC supplementation resulted in distinct community restructuring, characterized by enrichment of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria during Z2–Z4 and sustained increases in Bacteroidota across all developmental stages (Figure 3B). Notably, seven ASVs in the LAC treatment, predominantly belonging to Vibrio, were consistently up-regulated across multiple stages, whereas only ASV3 (Flavobacteriaceae) was down-regulated (Supplementary Figure 3). Both treatments exhibited clear stage-dependent dynamics: Z1 was marked by a general decline in ASV abundance, Z2–Z3 by pronounced enrichment, and Z4 by contrasting patterns, with a net increase under LAC but a reduction under ANT treatment (Figure 3C).

Figure 3

Differentially abundant ASVs across larval stages in S. paramamosain among treatment groups. (A) Numbers of significantly up- and down-regulated ASVs in pairwise comparisons (Ant vs CK and LAC vs CK) at each stage (Z1–Z4), identified by DESeq2 (|log2FC| > 1, adjusted p < 0.05). (B) Taxonomic affiliation of differential ASVs at the phylum level. (C) Mean log2 fold-change (log2FC) values showing abundance shifts under Ant and LAC treatments relative to CK.

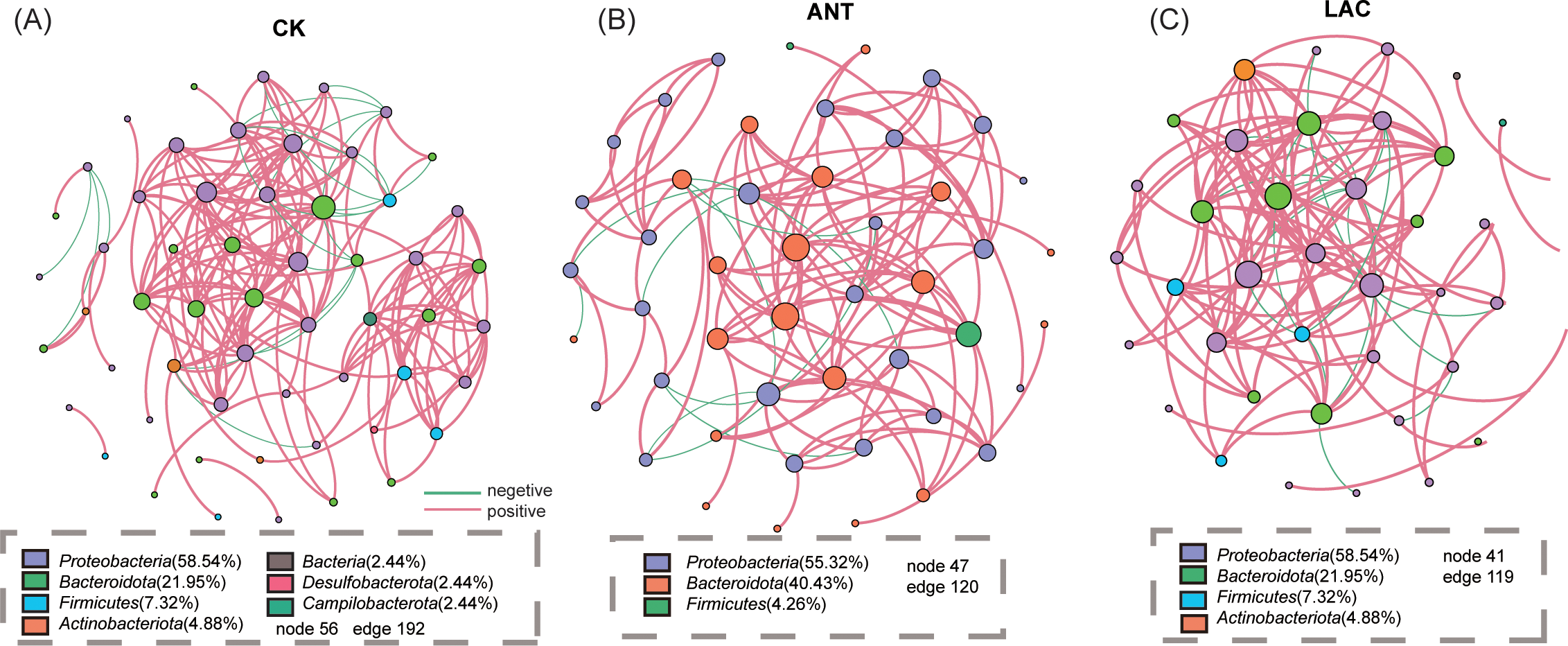

3.5 Community assembly and ecological networks

The microbial co-occurrence networks across all treatments were primarily composed of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota (Figure 4). The CK group exhibited the most complex community structure, additionally incorporating Firmicutes and Actinobacteriota (Figure 4A). In contrast, the ANT network appeared more specialized, with Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota collectively accounting for over 95% of the nodes (Figure 4B). Although the LAC network also included taxa such as Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, and Campilobacterota, its overall composition was markedly distinct from that of the CK group (Figure 4C).

Figure 4

Co-occurrence network analysis of microbial communities based on ASVs among treatment groups. (A–C) Co-occurrence networks constructed at the ASV level for (A) CK, (B) ANT, and (C) LAC groups. Nodes represent ASVs (colored by phylum), and edges indicate significant correlations (Spearman’s |r| > threshold, p < 0.05). Pink edges denote positive correlations, and green edges denote negative correlations.

Marked differences in network topology were observed under the ANT and LAC treatments. Relative to the CK group (56 nodes, 192 edges, positive correlations 90.1%), the ANT network (47 nodes, 120 edges, positive correlations 91.67%) exhibited the highest modularity (0.791) and average clustering coefficient (0.771) (Table 1). In contrast, the LAC network (41 nodes, 119 edges, positive correlations 85.91%) showed the lowest modularity (0.531), the highest proportion of negative correlations (14.29%), and the longest average path length (2.54), suggesting reduced network stability and increased community heterogeneity (Table 1).

Table 1

| Correlations (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | Edges | Modularity | Positive | Negative | Average clustering coefficient | Average path length | |

| CK | 56 | 192 | 0.584 | 90.1 | 9.9 | 0.709 | 1.855 |

| ANT | 47 | 120 | 0.791 | 91.67 | 8.33 | 0.771 | 2.068 |

| LAC | 41 | 119 | 0.531 | 85.91 | 14.29 | 0.676 | 2.54 |

Topological properties of microbial co-occurrence networks among treatment groups. Summary of key network parameters for the CK, ANT, and LAC groups. Metrics include the numbers of nodes and edges, modularity, proportions of positive and negative correlations, average clustering coefficient, and average path length.

Network-level analyses revealed that the LAC treatment significantly modified microbial interaction patterns, as evidenced by changes in node connectivity (degree) and centrality measures, including closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality (p < 0.05). Conversely, the overall structure of the ANT network remained largely comparable to the CK group, showing no significant topological deviations (Supplementary Figure 4C).

The five keystone ASVs shared among all treatments (CK, ANT, and LAC) were ASV10 (Proteobacteria), ASV19 (Actinobacteriota), ASV2, ASV49, and ASV91 (all Bacteroidota) (Supplementary Figures 4A, B). Their relative abundance patterns varied across treatments: ASV10 and ASV91 peaked at different developmental stages, whereas ASV2 showed a consistent increase in abundance in the LAC group (Supplementary Figures 4A, B).

Neutral community model (NCM) analysis was applied to infer the relative contributions of stochastic and deterministic processes in the assembly of predicted functional genes (KEGG level 3). The model exhibited moderate to high fits across all treatments (R² = 0.76 for CK, 0.746 for LAC, and 0.729 for ANT), suggesting that the overall distribution of functional genes conformed partially to neutral expectations (Figures 5A–C). However, the number of functional genes classified as Neutral KOs was relatively small (CK: 144; LAC: 155; ANT: 113), while Above-Neutral KOs and Below-Neutral KOs were dominant (Above: 3376–3402; Below: 3939–4044) (Figures 5A–C). Overall, the assembly of functional genes was mainly governed by deterministic environmental filtering across treatments (Figures 5A–C).

Figure 5

Functional prediction and neutral-model analysis of microbial communities among treatment groups. (A–C) Neutral-model fitting of predicted microbial functions (KEGG Level 3 KOs) for CK, Ant, and LAC groups. The proportions of KOs classified as above, below, or neutral to model expectations and model fit (R2) are shown. (D, E) Functional enrichment of above-neutral (overrepresented) KOs in (D) Ant and (E) LAC groups based on PICRUSt2 predictions.

KEGG enrichment showed that ANT-specific genes were linked to antibiotic biosynthesis, xenobiotic metabolism, and stress response, while LAC-specific genes were enriched in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, short-chain fatty acid production, and energy metabolism (Figures 5D, E). These results indicate that stochastic processes contributed to the assembly of functional genes (Figure 5). However, deterministic factors, particularly environmental filtering associated with different treatments, played the dominant role in shaping functional community structure (Figure 5).

4 Discussion

4.1 High temperature effects on microbial community succession

Elevated temperature is known to disrupt microbial community organization through intensified environmental filtering and reduced ecological resilience (Chai et al., 2024; Garcia et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2025). In this study, this effect was reflected by a significant temporal decay in microbial similarity across all treatments (p < 0.001) (Figure 2A). However, because larval microbiomes naturally undergo stage-dependent divergence during development, part of this decay may reflect intrinsic successional dynamics rather than heat stress alone. In S. paramamosain reared under normal temperature conditions, a similar pattern of stage-specific divergence has been reported (Fu et al., 2024). Therefore, the observed decline in similarity should be interpreted as potentially accelerated, rather than solely caused, by high-temperature stress.

Probiotic supplementation markedly alleviated this structural decline, as the LAC group exhibited the slowest decay rate (k = 0.0099) and the highest model fit (R² = 0.222), corresponding to a 24.8–32.6% reduction in decay rate compared with the control (Figure 2A). These results suggest that lactic acid bacteria supplementation enhanced the temporal stability and predictability of the larval microbiome, consistent with observations in larval rearing systems where probiotic interventions improved microbial homeostasis and resilience to environmental stress (Luo et al., 2024; Paralika and Makridis, 2025).

Despite these stabilizing effects, ANCOVA revealed a non-significant time × treatment interaction (p = 0.303), suggesting that neither antibiotic nor probiotic addition fundamentally altered the intrinsic succession rate of the larval microbiome. Taken together, the results indicate that high temperature imposes a strong background filter that shapes microbial succession, while probiotic treatment provides a buffering effect but does not fundamentally alter these thermally driven dynamics.

4.2 Diversity patterns and community restructuring

The microbial community structure demonstrates distinct stage-dependent successional patterns during development. Research results show no significant differences in microbial diversity among treatment groups during the early developmental stages (Z1-Z2) (p > 0.05) (Figures 1A–C), indicating that community assembly in this phase is primarily governed by developmental programming. This finding aligns with the fundamental patterns of microbial colonization in early developmental stages of aquatic organisms (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2025), as evidenced by studies in Litopenaeus vannamei where microbial community establishment was mainly driven by temporal progression (Wang et al., 2020). This phenomenon is further supported by NMDS analysis, which revealed significant community differentiation among treatment groups at the Z4 stage (Figures 1D, E), consistent with observations from other probiotic application experiments (Jurado et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021).

Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota served as the dominant phyla throughout the culture period, exhibiting clear stage-specific abundance variations (Figure 2B). This pattern of phylum-level succession aligns with observations in other aquatic species, such L. vannamei larvae (Wang et al., 2020). The significant increase in Proteobacteria (67.36%) during the Z3 stage coincided with elevated temperature (Figure 2B), indicating thermal stress as a key driver of community restructuring, a phenomenon supported by the temperature-driven enhancement of their metabolism and phylogenetic distribution (Hirata et al., 2017; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2017).

Under these conditions, differential ASV analysis revealed that LAB treatment not only specifically enriched ASVs of Vibrio but also significantly downregulated ASV3 (Flavobacteriaceae) (Supplementary Figure 3). Given that Flavobacteriaceae includes multiple known aquatic pathogens (Çağatay, 2024; Yu et al., 2025), this reduction in abundance may directly decrease the pathogenic risk of the community. Indeed, it was identified as the primary pathogen causing temperature-dependent shell disease in mud crabs (Yu et al., 2025). While vibrios are potential pathogens, including Vibrio alginolyticus as a causative agent of shell disease in Scylla serrata (Gunasekaran et al., 2019), it is noteworthy that probiotic applications have been reported to increase the abundance of specific Vibrio groups in S. paramamosain (Li et al., 2021). Our research further corroborates this phenomenon, revealing the context-dependent nature of Vibrio colonization.

4.3 Microbial network under thermal stress

Our findings revealed clear alterations in microbial network topology and composition, indicating treatment-specific effects on community assembly and stability. The CK group displayed the most complex and balanced microbial network, whereas the ANT group developed a more specialized and modular community (Figure 5), reflecting higher organization and resilience under antibiotic pressure. In contrast, the LAC group showed markedly lower modularity (0.531), a higher proportion of negative correlations (14.29%), and a longer average path length (2.54) (Table 1), suggesting a fragmented and less stable network. This instability likely resulted from the introduction of LAB, which modified microbial associations through competitive exclusion and metabolic interactions that affected the growth and activity of other taxa (Wei et al., 2024; Xia et al., 2022). Consistent with this, topological parameter analysis revealed significant differences between the LAC and CK networks, with changes in degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality (Supplementary Figure 3), indicating that LAB reshaped the roles of key taxa and weakened overall network stability (Liu et al., 2024).

Network analysis showed that the ANT network was dominated by Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota, which together accounted for over 95% of the nodes (Figure 5). This dominance likely reflects selective pressure from antibiotics, resulting in a specialized and resilient microbial assemblage. In contrast, the LAC network included additional phyla such as Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, and Campilobacterota, yet its lower modularity and higher proportion of negative correlations (Figure 5) indicated reduced stability. Such instability may weaken key ecological functions of the microbiome, including nutrient cycling and disease resistance (Li et al., 2025).

The core ASVs shared across all treatments play an important role in maintaining community stability and functionality. These ASVs displayed varying abundance patterns across treatments. ASV10 (Proteobacteria) remained relatively stable across all treatments, while ASV2 (Bacteroidota) showed a significant increase in the LAC group. In contrast, ASV19 (Actinobacteriota) and ASV91 (Bacteroidota) exhibited treatment-dependent fluctuations (Supplementary Figure 3), suggesting that antibiotics and probiotics can selectively influence microbial communities and affect their functional stability (Li et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2024).

4.4 Assembly processes and functional capabilities

The NCM analysis revealed that the predicted functional gene profiles were only partially consistent with neutral expectations (R² = 0.729–0.76), suggesting that while stochastic processes such as dispersal and drift contributed to functional assembly, deterministic mechanisms exerted stronger influence. This interpretation is supported by the small proportion of Neutral KOs (CK: 144; LAC: 155; ANT: 113) compared with the large numbers of Above- and Below-Neutral KOs (Above: 3376–3402; Below: 3939–4044) (Figures 5A–C), indicating that environmental filtering and niche selection were predominant forces shaping microbial functions under different treatments.

KEGG functional enrichment provided further evidence of such deterministic effects. In the ANT group, Above-Neutral functions were enriched in antibiotic biosynthesis, xenobiotic metabolism, and stress response (Figure 5D). These pathways are commonly associated with microbial adaptive responses to exogenous chemical stressors (Wright, 2007) and have been documented in the gut microbiota of marine animals (Zhang et al., 2024b). This pattern is consistent with the stronger environmental filtering indicated by the neutral model. Meanwhile, the reduced diversity and simplified network structure in the ANT group suggest a more stressed microbial community (Okeke et al., 2022). The enrichment of these stress-related functions may reflect a shift in microbial functional allocation, although its implications for larval growth require further investigation.

In contrast, the LAC group showed enrichment in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, short-chain fatty acid production, and energy metabolism (Figure 5E), consistent with probiotic-driven metabolic diversification. These treatment-specific enrichments imply that antibiotic stress and probiotic supplementation acted as distinct environmental filters, shaping microbial functional traits through directional selection rather than neutral dynamics.

Similar findings have been reported in crustacean larval systems, where microbial community assembly involves both stochastic and deterministic components, with deterministic selection strengthening under environmental or nutritional perturbations (Lu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2026). Collectively, these results suggest that while stochasticity contributes to baseline variation, environmental filtering dominates the functional gene assembly of larval microbial communities under interventions with antibiotics and probiotics.

5 Conclusion

High-temperature conditions impose strong environmental filtering on S. paramamosain larval microbiota, driving community instability and functional disruption. Our results show that probiotic supplementation partially counteracted these effects by enhancing microbial stability and promoting beneficial metabolic functions, whereas antibiotic exposure intensified selective pressure and reduced microbial diversity and functional balance. Although LAB abundance was evaluated, the administered strain did not establish detectable colonization, which should be considered when interpreting probiotic efficacy. Overall, these findings illustrate that microbial manipulation can modulate community resilience under thermal stress, providing a potential strategy to improve larval performance in high-temperature rearing environments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. NQ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. CC: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research received financial support from the following sources: the Earmarked Fund for the Wenzhou Agricultural New Variety Breeding Cooperation Group (Grant No. ZX2025003-02); the Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Coastal Biological Germplasm Resources Conservation and Utilization (Grant Nos. J2024007 and 2024E10128); and the Agricultural Major Technology Collaborative Extension Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2024ZDXT17); Zhejiang Province Research and Development Plan Project (No.2023ZY1056); the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-48).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer YF declared a shared affiliation with the authors WW, XW, CY and NQ to the handling editor at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to polish and improve the linguistic expression and readability of the text. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1744090/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Daily temperature variation during the larval rearing experiment. Temporal changes in water temperature recorded during larval rearing of S. paramamosain. Morning and noon temperatures were measured daily to illustrate diurnal fluctuations throughout the experiment.

Supplementary Figure 2Final survival rate of S. paramamosain larvae among treatment groups. Final survival rates of CK, ANT, and LAC groups at the end of larval rearing. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Supplementary Figure 3Temporal dynamics of shared differentially abundant ASVs between LAC and CK groups. Relative abundance changes of ASVs consistently identified as differentially abundant between LAC and CK across multiple larval stages (Z1–Z4).

Supplementary Figure 4Keystone ASVs and network topology characteristics among treatment groups. (A) Venn diagram showing overlap of keystone ASVs among CK, ANT, and LAC groups, with five shared ASVs. (B) Relative abundance of the shared keystone ASVs across larval stages. (C) Comparison of network topology parameters—degree, closeness centrality, eigenvector centrality, and betweenness centrality—among the three networks.

Supplementary Table 1Larval development time (Z1–Z4) in S. paramamosain under different treatment groups. Data show the average time in days for each stage (Z1–Z4) and the total development time. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Supplementary File 116S rRNA gene sequence of the isolated commercial probiotic strain.

References

1

Bastian M. Heymann S. Jacomy M. (2009). “ Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks,” in Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Vol. 3. 361–362. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937

2

Bledsoe J. W. Waldbieser G. C. Swanson K. S. Peterson B. C. Small B. C. (2018). Comparison of channel catfish and blue catfish gut microbiota assemblages shows minimal effects of host genetics on microbial structure and inferred function. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01073

3

Bolger A. M. Lohse M. Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

4

Burns A. R. Stephens W. Z. Stagaman K. Wong S. Rawls J. F. Guillemin K. et al . (2016). Contribution of neutral processes to the assembly of gut microbial communities in the zebrafish over host development. ISME J.10, 655–664. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.142

5

Çağatay İT. (2024). Use of proteomic-based MALDI-TOF mass spectra for identification of bacterial pathogens in aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture Int.32, 7835–7871. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01544-x

6

Callahan B. J. McMurdie P. J. Rosen M. J. Han A. W. Johnson A. J. A. Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

7

Chai G. Li J. Li Z. (2024). The interactive effects of ocean acidification and warming on bioeroding sponge Spheciospongia vesparium microbiome indicated by metatranscriptomics. Microbiological Res.278, 127542. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2023.127542

8

Chen H. Boutros P. C. (2011). VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinf.12, 35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35

9

Clarke K. R. (1993). Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Ecology74, 1203–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x

10

Cole J. R. Wang Q. Cardenas E. Fish J. Chai B. Farris R. J. et al . (2014). Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.42, D633–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244

11

Dai W. Sheng Z. Chen J. Xiong J. (2020). Shrimp disease progression increases the gut bacterial network complexity and abundances of keystone taxa. Aquaculture517, 734802. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734802

12

Daunde V. V. Y. Liao W. Zhang Z. Liu W. Zhang S. (2026). Effects of climate change-induced temperature rise on crustacean aquaculture: A comprehensive review. Aquaculture Fisheries.11, 11–32. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2025.08.008

13

Douglas G. M. Maffei V. J. Zaneveld J. Yurgel S. N. Brown J. R. Taylor C. M. et al . (2020). PICRUSt2: An improved and customizable approach for metagenome inference. Nat. Biotechnol.38, 685–688. doi: 10.1101/672295

14

Figueras A. Chizhayeva A. Amangeldi A. Oleinikova Y. Alybaeva A. Sadanov A. (2022). Lactic acid bacteria as probiotics in sustainable development of aquaculture. Aquat. Living Resour.35, 10. doi: 10.1051/alr/2022011

15

Fox J. Weisberg S. Adler D. Bates D. Baud-Bovy G. Ellison S. et al . (2012). Package ‘car’. R Foundation Stat. Computing16, 333.

16

Francino M. P. (2014). Early development of the gut microbiota and immune health. Pathogens3, 769–790. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3030769

17

Fu Y. Cheng Y. Ma L. Zhou Q. (2024). Longitudinal microbiome investigations reveal core and growth-associated bacteria during early life stages of Scylla paramamosain. Microorganisms12, 2457. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12122457

18

Garcia F. C. Warfield R. Yvon-Durocher G. (2022). Thermal traits govern the response of microbial community dynamics and ecosystem functioning to warming. Global Change Biol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.906252

19

Gunasekaran T. Gopalakrishnan A. Deivasigamani B. Muhilvannan S. Kathirkaman P. (2019). ). Vibrio alginolyticus causing shell disease in the mud crab Scylla serrata (Forskal 1775). Indian J. Geo-Marine Sci.48, 1359–1363.

20

Hirata M. Ikeda M. Fukuda F. Abe M. Sawada H. Hashimoto S. (2017). Effect of temperature on the production rates of methyl halides in cultures of marine Proteobacteria. Mar. Chem.196, 126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2017.08.012

21

Jurado J. Villasanta-González A. Tapia-Paniagua S. T. Balebona M. C. Moríñigo M. A. Prieto-Álamo M. J. (2018). Dietary administration of the probiotic Shewanella putrefaciens Pdp11 promotes transcriptional changes of genes involved in growth and immunity in Solea Senegalensis larvae. Fish Shellfish Immunol.77, 350–363. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.04.018

22

Li T. Jin Z. Du S. Liang C. Wang Y. Yao Z. et al . (2021). Effects of lactic acid bacteria activation methods on mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) hatching rate and the microbiota in larval culture. Aquaculture Res.52, 3997–4002. doi: 10.1111/are.15199

23

Li J. Wu J. Tu M. Xiao X. Hu K. Li Q. et al . (2025). Interaction between lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in Sichuan bran vinegar: impact on their growth and metabolites. Front. Microbiol.14, 1471. doi: 10.3390/foods14091471

24

Li Z. Zeng Z. (1992). Effect of temperature on survival and development of Scylla paramamosain larvae. J. Fisheries China03, 213–221.

25

Li Z. Zhao Z. Luo L. Wang S. Zhang R. Guo K. et al . (2023). Immune and intestinal microbiota responses to heat stress in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture563, 738965. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738965

26

Li H. Zhong Y. Huang H. Tan Z. Sun Y. Liu H. (2020). Simultaneous nitrogen and phosphorus removal by interactions between phosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) and denitrifying PAOs (DPAOs) in a sequencing batch reactor. Sci. Total Environ.744, 140852. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140852

27

Liu Q. Dong D. Jin Y. Wang Q. Zhao F. Wu L. et al . (2024). Quorum sensing bacteria improve microbial network stability and complexity in wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Int.187, 108659. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108659

28

Liu J. Zhang Z. Huang Y. Li J. Zhang W. (2022). Effects of temperature on growth, molting, feed intake, and energy metabolism of individually cultured juvenile mud crab Scylla paramamosain in the recirculating aquaculture system. Water14, 2988. doi: 10.3390/w14192988

29

Love M. I. Anders S. Huber W. (2014). Differential analysis of count data – the DESeq2 package. Genome Biol.15, 550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

30

Lu Z. Lin W. Li Q. Wu Q. Ren Z. Mu C. et al . (2024). Recirculating aquaculture system as microbial community and water quality management strategy in the larviculture of Scylla paramamosain. Water Res.252, 121218. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121218

31

Luo K. Yang Z. Wen X. Wang D. Liu J. Wang L. et al . (2024). Recovery of intestinal microbial community in Penaeus vannamei after florfenicol perturbation. J. Hazardous Materials480, 133517. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136158

32

Okeke E. S. Zhang L. Li Z. Ojo O. Ezeh C. U. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in aquaculture and aquatic organisms: a review of current nanotechnology applications for sustainable management. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res.29, 69241–69274. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22319-y

33

Oksanen J. Kindt R. Legendre P. O’Hara B. Stevens M. H. H. Oksanen M. J. (2007). The vegan package. Community Ecol. Package10, 719.

34

Ostertagova E. Ostertag O. Kováč J. (2014). Methodology and application of the Kruskal-Wallis test. Appl. Mech. Mater.611, 115–120. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.611.115

35

Panigrahi A. Esakkiraj P. Jayashree S. Saranya C. Das R. R. Sundaram M. (2019). Colonization of enzymatic bacterial flora in biofloc-grown shrimp Penaeus vannamei and evaluation of their beneficial effect. Aquaculture Int.27, 1835–1846. doi: 10.1007/s10499-019-00434-x

36

Paralika V. Makridis P. (2025). Microbial interactions in rearing systems for marine fish larvae. Microorganisms13, 539. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13030539

37

Pérez-Rodríguez I. Sievert S. M. Fogel M. L. Foustoukos D. I. (2017). Biogeochemical nitrogen signatures from rate-yield trade-offs during in vitro chemosynthetic nitrate reduction by deep-sea vent ϵ-Proteobacteria and Aquificae growing at different temperatures. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta211, 214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2017.05.014

38

Quast C. Pruesse E. Yilmaz P. Gerken J. Schweer T. Yarza P. et al . (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res.41, 590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

39

Vadstein O. Attramadal K. J. Bakke I. Forberg T. Olsen Y. Verdegem M. et al . (2018). Managing the microbial community of marine fish larvae: a holistic perspective for larviculture. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01820

40

Wang C. (2023). Current situation and countermeasures for high-quality development of China’s mud crab aquaculture industry [in Chinese. J. Dalian Ocean Univ.38, 913–924.

41

Wang Y. Wang K. Huang L. Dong P. Wang S. Chen H. et al . (2020). Fine-scale succession patterns and assembly mechanisms of bacterial community of Litopenaeus vannamei larvae across the developmental cycle. Microbiome8, 106. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00879-w

42

Wang L. Zhang W. Gladstone S. Ng W. K. Zhang J. Shao Q. (2019). Effects of isoenergetic diets with varying protein and lipid levels on the growth, feed utilization, metabolic enzymes activities, antioxidative status and serum biochemical parameters of black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). Aquaculture513, 734397. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734397

43

Wei J. Nie Y. Du H. Xu Y. (2024). Reduced lactic acid strengthens microbial community stability and function during Jiang-flavour Baijiu fermentation. Food Bioscience59, 103935. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.103935

44

Wright G. D. (2007). The antibiotic resistome: the nexus of chemical and genetic diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.5, 175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1614

45

Xia M. Zhang X. Xiao Y. Sheng Q. Tu L. Chen F. et al . (2022). Interaction of acetic acid bacteria and lactic acid bacteria in multispecies solid-state fermentation of traditional Chinese cereal vinegar. Front. Microbiol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.964855

46

Xiong J. Dai W. Li C. (2016). Advances, challenges, and directions in shrimp disease control: the guidelines from an ecological perspective. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.100, 6947–6954. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7679-1

47

Xiong J. Wang K. Wu J. Qiuqian L. Yang K. Qian Y. et al . (2015). Changes in intestinal bacterial communities are closely associated with shrimp disease severity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.99, 6911–6919. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6632-z

48

Yu Z. Qiao Z. Wang J. (2007). Study on high-temperature larval culture techniques of mud crab Scylla serrata. Modern Fisheries Inf.08, 27–29.

49

Yu G. Wang L. G. Han Y. He Q. Y. (2012). Cluster Profiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS: A J. Integr. Biol.16, 284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.011

50

Yu K. Wang X. Wang C. Mu C. Ye Y. Zhan P. et al . (2025). Temperature-dependent shell disease may relate to bacterial community changes of mud crab Scylla paramamosain in RAS. Aquaculture605, 742900. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742488

51

Zhang F. Chen H. Yu J. Chen R. Zhang D. Chen C. et al . (2025). Source tracking of larval bacterial community of Pacific white shrimp across the developmental cycle. Aquaculture609, 742800. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742800

52

Zhang S. Hou R. Wang Y. Huang Q. Liu H. Li H. et al . (2024b). Xenobiotic metabolism activity of gut microbiota from six marine species: Combined taxonomic, metagenomic, and in vitro transformation analysis. J. Hazardous Materials480, 136152. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136152

53

Zhang S. Liu S. Liu H. Li H. Luo J. Zhang A. et al . (2024a). Stochastic assembly increases the complexity and stability of shrimp gut microbiota during aquaculture progression. Mar. Biotechnol.26, 92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10126-023-10279-4

54

Zhao W. Hu A. Soininen J. Wang J. J. (2025). Microbial responses to temperature change mediated by nutrient enrichment. Global Ecol. Biogeography34, e70111. doi: 10.1111/geb.70111

55

Zheng Y. Yu M. Liu J. Qiao Y. Wang L. Li Z. et al . (2017). Bacterial community associated with healthy and diseased Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) larvae and rearing water across different growth stages. Front. Microbiol.8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01362

56

Zou S. Zheng Y. Yuan J. Ni M. Liu M. Zhou D. et al . (2026). Succession patterns, environmental connections, and assembly mechanisms of gut microbiota in the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) across lifespan. Aquaculture610, 742927. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742927

Summary

Keywords

Scylla paramamosain , larval development, high-temperature stress, probiotics, microbial community, co-occurrence network, keystone taxa, functional assembly

Citation

Yu J, Li T, Wang G, Ling J, Wang W, Wang X, Yin C, Qiao N and Chen C (2026) Probiotics reshape microbial community assembly and functional stability in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) larvae under high-temperature stress. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1744090. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1744090

Received

11 November 2025

Revised

11 December 2025

Accepted

17 December 2025

Published

28 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Naresh Kumar Dewangan, Shri Shankaracharya Professional University, India

Reviewed by

Yunfei Sun, Shanghai Ocean University, China

Yafei Duan, South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, China

Yin Fu, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yu, Li, Wang, Ling, Wang, Wang, Yin, Qiao and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Wang, wangw@ecsf.ac.cn; Chen Chen, 10006986@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.