Abstract

In most animals, excess dietary energy is stored as lipids in specialized tissues, such as the liver in vertebrates or the hepatopancreas and fat body in invertebrates, which function as energy reservoirs for reproduction. In cephalopods, however, dietary energy is rapidly mobilized from the digestive gland for growth rather than stored for reproduction. How excess energy is allocated for reproduction activity in cephalopods remains largely unclear. Lipogenesis is initiated by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), which converts acetyl-CoA derived from dietary carbon sources into malonyl-CoA; subsequent synthesis of saturated fatty acids is catalyzed by fatty acid synthase (FAS). Using the bigfin reef squid as a model, we investigate the role of fas in female development. fas mRNA was highly expressed in ovaries but weak in other tissues, including the lipid-rich digestive gland. fas showed female-biased expression in gonads, with level highest in juvenile ovaries and progressively decreasing to their lowest in mature ovaries. Expression was also high in primary and multiple follicular oocytes but declined in later stages. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry confirmed fas mRNA and protein localization in oocytes, particularly in primary and multiple follicular oocytes. In vitro ovarian culture further showed that inhibiting FAS activity enhanced somatic cell proliferation. Together, these findings suggest that squid ovary is a primary site of fatty acid synthesis, supporting early oocyte growth and membrane biogenesis in the absence of dedicated lipid storage tissues. The decline of FAS activity during oogenesis, and the associated reproduction in fatty acid synthesis, may act as a regulatory signal to promote somatic cell proliferation.

1 Introduction

Coastal cephalopods are promising candidates for aquaculture due to their rapid growth rates, and several species, including bigfin reef squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana), cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis and S. pharaonis) and octopus (Octopus maya and O. vulgaris), are already being cultured at small to large scales (Jiang et al., 2021; Vidal et al., 2014). Among them, the bigfin reef squid is a commercially valuable species in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in East Asian countries such as Japan and Taiwan, where the market price for live squid can reach approximately 35 USD per kilogram. Despite its potential, large-scale aquaculture of this species is hindered by low reproductive success in captive populations. In particular, later generations often exhibit structural abnormalities in the egg case, resulting in poor embryonic development and significantly reduced offspring production (Ikeda et al., 2009). Consequently, achieving full-life-cycle aquaculture of the bigfin reef squid remains a major challenging due to the unreliable production of viable offspring in captivity. In most cephalopods, the egg case consists of multiple layers, including an inner jelly-like matrix and outer egg capsule, which are secreted by the oviductal gland and nidamental gland, respectively (Huang et al., 2018; Lum-Kong, 1992). The development of these glands is closely linked to the female reproductive cycle (Huang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Lum-Kong, 1992) and is likely regulated by female-derived signals, particularly ovary-secreted factors. Thus, the abnormal egg case structures observed in captive bigfin reef squid may result asynchronous development between the ovary and it associated reproductive glands, particularly in captivity-induced precocious females.

Nutritional status plays a critical role in reproductive processes such as gametogenesis, gonadal maturation, and overall fertility in animals. Inadequate nutrient intake has been widely associated with reduced reproductive activity in many adult species (Dunn and Moss, 1992). In cephalopods, high proteolytic activity in the digestive gland reflects their carnivorous feeding habits (Boucaud-Camou and Boucher-Rodoni, 1983). Notably, loliginid squids do not store significant amounts of dietary lipids in the digestive gland for later use in reproduction or as an energy source for oocytes (Semmens, 1998). Additionally, digestion in bigfin reef squid is extremely rapid, often completed within just 4 hours (Semmens, 2002). These finding suggest that inter-feeding intervals longer than 4 hours may induce a nutritional deficit or “hungry state” in captive squid, potentially forcing them to mobilize stored lipids for energy. This metabolic stress could impair reproductive development, especially in females, by depleting energy reserves stored in lipid-rich oocytes. Therefore, cephalopod may have evolved unique strategies for female reproduction, particularly to support the development and maintenance of oocytes.

The first committed step of lipogenesis is catalyzed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), which converts acetyl-CoA derived from carbon sources derived from carbohydrates and amino acids into malonyl-CoA (Tong, 2013; Bianchi et al., 1990). Subsequently, the de novo synthesis of saturated fatty acids from malonyl-CoA is carried out by fatty acid synthase (FAS) (Smith et al., 2003). In addition to its role in fatty acid biosynthesis, malonyl-CoA can also serve as a precursor for polyketide synthesis in secondary metabolism (Günenc et al., 2022). Molluscan-specific animal FAS-like polyketide synthases have been reported in cephalopods (Lin et al., 2024). Therefore, fas expression can be used as a proxy for sustained lipogenic capacity in cephalopod.

In vertebrates, FAS/fas mRNA is highly expressed in lipid-rich tissues such as the liver and adipose tissue, including in mammals (Mildner and Clarke, 1991), birds (Cui et al., 2012), and fish (Peng et al., 2017; Sakae et al., 2020). Similarly, studies in invertebrates have shown high fas expression in lipid-rich tissues, such as the hepatopancreas of bivalves (Nie et al., 2023) and the fat body of insects (Song et al., 2022). However, in crustacean, fas expression is relatively low in the hepatopancreas compared to other tissues such as the stomach, pyloric cecum, and muscle (Zuo et al., 2017). Together, these findings suggest that the primary site of de novo fatty acid synthesis appears to be conserved among vertebrates but is more variable across invertebrate species. Additionally, FAS/fas transcripts exhibit sexually dimorphic expression patterns, with higher expression levels in the ovaries of fish (Baron et al., 2008; Sakae et al., 2020) and bivalves (Li et al., 2022b; Teaniniuraitemoana et al., 2014). Furthermore, fas-deficient mosquitoes produced fewer eggs than controls (Alabaster et al., 2011). These findings suggest that de novo fatty acid synthesis in the ovary may play a crucial role in reproduction of female squid.

Although gonadal transcriptomic data indicate enrichment of fatty acid biosynthesis pathway in the ovary but not the testis of the Asian common octopus (Octopus sinensis) (Li et al., 2024), the functional role of de novo fatty acid synthesis in cephalopod reproduction remains largely unexplored. In this study, we used the bigfin reef squid as a model to address following questions: 1) whether de novo fatty acid synthesis is sexually dimorphic and preferentially associated with ovarian development; 2) how the spatial and temporal expression of fas/FAS during oocyte development; and 3) whether FAS activity is required for normal ovarian development. We hypothesized that ovary-specific lipogenesis supports oocyte growth under nutritionally dynamic conditions and that disruption of this pathway impairs female reproductive development. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expression and localization of fas mRNA across gonadal stages using quantitative PCR (qPCR), in situ hybridization (ISH), and immunohistochemistry (IHC), and functional evaluated FAS activity using the specific inhibitor TVB-3166 in an in vivo organ culture system. Our results demonstrate fas transcripts were exclusively expressed in the ovary, with minimal expression in other tissues. Both fas mRNA and protein were exclusively localized in oocytes, especially in primary oocyte stage. Additionally, FAS inhibition disrupts the proliferation of oocyte-surrounding cells. Collectively, these findings suggest that de novo fatty acid synthesis may play a critical role in ovarian development in cephalopods and provide new mechanistic insight into reproductive failure under captive conditions, with potential implications for full life-cycle aquaculture.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Squid sampling

Bigfin reef squid were purchased from a fisherman on Heping Island, Keelung. These squids were collected using hand jigging from a boat near Heping Island, located along the northeastern coast of Taiwan. Additionally, juvenile bigfin reef squids were provided as a gift by the Marine Research Station of the Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology, Academia Sinica.

Sex identification was based on gonadal morphology and the presence of accessory reproductive organs, such as the nidamental gland in females and spematophoric gland in males, as previously described (Lee et al., 2025). When external morphology was insufficient to determine sex, gonadal histology was further used for confirmation. The gonadal status of females, as well as the relationship between oocyte size and developmental stage, was assessed using gross morphological characteristics and ovarian histology, respectively, as described in our previous work (Chen et al., 2018). Male gonadal status was classified as either immature or mature based on the presence of spermatophores. Squids were anesthetized with 5% ethanol in seawater at room temperature, and tissue samples were collected prior to decapitation. All experimental procedures were approved by the National Taiwan Ocean University International Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with standard ethical guidelines.

2.2 Experimental designs

2.2.1 Experiment 1: analysis of gene expression in different tissues and reproductive stages of male and female squid

For tissue distribution analysis, tissues from a mature female were collected to assess relative expression across organs. Tissues were further collected from immature and mature males (n = 3 in each stage), including the digestive gland and testis. For females, tissues were collected from immature (n = 4) and mature individuals (n = 3), including the digestive gland, ovary, nidamental gland, and accessory nidamental gland. Additionally, the oviductal gland was collected only from mature females. The biological characteristics of the squids were described in our previous study (Chen et al., 2018).

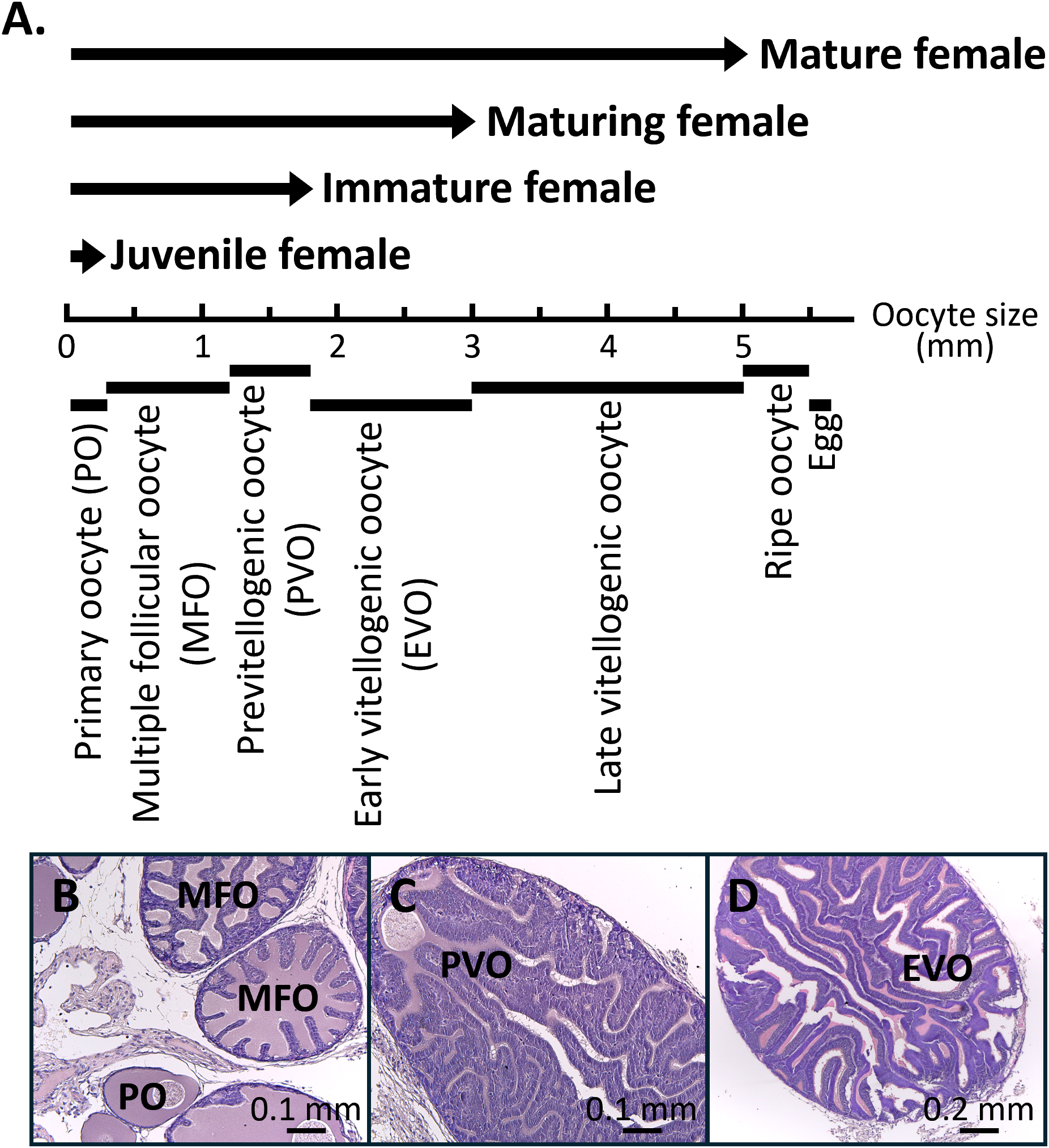

2.2.2 Experiment 2: gene expression profiling and enzymatic activity across various stages of ovarian development

Ovaries at different developmental stages were collected, including juvenile females containing primary oocytes (n = 4), immature females with previtellogenic oocytes (n = 14), maturing females with early vitellogenic oocytes (n = 12), and mature females with late vitellogenic oocytes (n = 9) (Figure 1A). Although multiple oocyte stages can coexist within a single ovary, the developmental stage of each ovary was determined based on the most advanced oocytes present. The histological characteristics of key oocyte stages are shown, including primary oocytes (Figure 1B), multiple follicular oocytes (Figure 1B), previtellogeneic oocytes (Figure 1C), and early vitellogenic oocytes (Figure 1D). For RNA extraction, we carefully dissected ovarian regions enriched in these dominant oocytes to minimize contamination from less-developed oocytes, ensuring that transcriptomic profiles primarily reflect the intended developmental stage. To further examine the gene expression profile and FAS activity, oocytes ranging in sizes from 0.5 to 6 mm were collected from mature females. The relationship between the oocyte size and developmental stage is shown in Figure 1A. The biological characteristics of the squids were described in our previous study (Chen et al., 2018).

Figure 1

Relationship between the oocyte size, oocyte stages, and female reproductive stages. (A) Seven oocyte stages classified by size: primary oocyte (<300 µm), multiple follicular oocyte stage (0.3-1.2 mm), previtellogenic oocyte (1.2-1.8 mm), early vitellogenic oocyte (1.8-3 mm), late vitellogenic oocyte (3-5 mm), ripe oocyte (5-5.5 mm), and egg (>5.5 mm). Four female reproductive stages were defined according to oocyte development: juvenile female (up to the primary oocyte stage), immature female (up to the previtellogenic oocyte stage), maturing female (up to the early vitellogenic oocyte stage), and mature female (containing eggs in the oviduct). (B-D) H&E staining of representative oocyte stages. PO, primary oocyte; MFO, multiple follicular oocyte stage; PVO, previtellogenic oocyte; EVO, early vitellogenic oocyte.

2.2.3 Experiment 3: localization of target genes and their proteins within the ovary

To further determine the location of de novo fatty acid synthesis, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining of were performed to detect fas mRNA and protein expression levels in the gonads, with a particular focus on the ovary.

2.2.4 Experiment 4: functional characterization of FAS in the ovary

Based on literature reviews and our laboratory observations, chemicals injection techniques have not yet been successfully applied in squid due to the high mortality rate following administration. To investigate the role of FAS, we established an in vitro organ culture system using juvenile female ovaries (30 days post-hatching), treated with a FAS inhibitor. The samples were then subjected to immunohistochemical analysis to evaluate the effect, particularly on cell proliferation activity.

2.3 Gonad histology

Tissue histology was performed as described in our previous study (Chen et al., 2018). Gonads were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 16 hours, dehydrated in methanol, and stored at -20°C. The tissues were then processed through an ethanol-xylene series and embedded in paraffin. Sections were dissected at 5-µm thickness, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.4 Nucleic acid extraction

Nucleic acids were extracted using Trizol reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific), following the manufacture’s protocol. Trizol-homogenized tissues were mixed with chloroform to separate total RNA into the upper aqueous phase. RNA was then precipitated using a high-salt solution and isopropanol. The isolated RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and used for subsequent cDNA synthesis.

2.5 RNA analysis

cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using Oligo(dT)12-18 primers (Company) and Superscript III (Company), following the manufacture’s protocol. The synthesized cDNA was then used for qPCR analysis, performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2018). Gene expression levels were quantified using the CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) with SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad). PCR specificity for each gene was confirmed by the presence of a single melting curve in both experimental samples and template-containing (positive) controls. No signal was detected in the non-templet (blank) controls. Reaction efficiency for each gene was initially assessed using serially diluted standards. The qPCR amplification efficiencies of fas and ef1a were 70.8% and 73.2%, respectively. Because the difference in amplification efficiency between fas and ef1a were lower than 2.5%, the relative expression levels of the fas gene (GeneBank accession no. PX526114) were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Elongation factor 1 alpha (ef1a; GeneBank accession no. MG924746) was selected as the internal reference gene for qPCR normalization based on its narrow Ct distribution across all tissues (16.2 ± 0.75). The specific qPCR primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

| Gene (GeneBank accession no.) | Orientation | Sequence | Analysis (Amplicon size, bp) | PCR amplification efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ef1a

(PX526114) |

Sense | 5’-CCAGGTGACAATGTTGGTTTC-3’ | qPCR (101) |

70.8% |

| Antisense | 5’-GTCTCTTTGGGTGGGTTATTCT-3’ | |||

|

fas

(MG924746) |

Sense | 5’-GCCATTGGTGATGTTGGTATTG-3’ | qPCR (128) |

73.2% |

| Antisense | 5’-GGGCTGTCCTGGTTTAAGAA-3’ | |||

| fas | Sense | 5’-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGG- GGGAATGAAGACTGGAAAGGAGT-3’ |

ISH (1, 649) |

|

| Antisense | 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG- GTGACTGGATGTGTGGGCT-3’ |

Oligonucleotides for specific primers used for the RNA analysis.

The bottom line indicates the T3 and T7 sequences used for synthesizing the sense and antisense probes, respectively.

2.6 In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-11-UTP (DIG)-labeled antisense and sense probes were synthesized from target fragments of the fas genes (Table 1). The DIG-labeled antisense probe was used to detect target mRNA localization, while the sense probe served as a negative control to assess non-specific signal. Wholemount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed as our previous description (Li et al., 2022a). Fixed samples were rehydrated and sectioned into 0.1 mm slices using a vibratome (microslicer DTK-1000, Dosaka), followed by standard ISH procedures. Samples were incubated overnight at 50-60°C with DIG-labeled probes. mRNA expression was detected using an ovary-pre-adsorbed, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-DIG antibody (11093274910, Merck), and visualized using the NBT/BCIP Detection System (11681451001, Roche). Following color development, samples were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Technovit 3040 plastic resin. Sections were dissected at 5-µm thickness, rehydrated, and counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (H-3403-500, Vector Laboratories) to visualize cell nuclei.

2.7 Antiserum generation

Polyclonal antiserum was generated by immunizing rabbit with a synthetic peptide (H2N-CNKPLKIEVIDGNHESFIQGEYAQK-COOH) corresponding to the C-terminal region of bigfin reef squid FAS, conjugated to ovalbumin. The immunization and antiserum collection were performed by Yao-Hong Biotechnology Inc. The specificity of the antiserum was further confirmed by Western blot (WB) analysis using tissue samples expressing the target protein.

2.8 Antiserum specificity analysis

Protein analysis was performed as described in our previous study (Chen et al., 2018). Samples were homogenized in cell lysis buffer containing 25 µM Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and cOmplete™ Mini protease inhibitor cocktail (4693124001, Roche) and centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for subsequent analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using a Pierce™ bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (A65453, ThermoFisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (up to 20 µg per sample) were separated on a 5% SDS-PAGE gel. For WB analysis, the separated proteins were transferred onto a 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membrane. After washing, membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk powder for 1 hour and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody, anti-FAS antiserum (1: 2000 dilutions in 1.5% nonfat milk). The membranes were subsequently incubated with an alkaline phosphate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (31340, ThermoFisher Scientific; 1: 10,000 dilutions in 1.5% nonfat milk) at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein expression was visualized using the 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium chloride solution (BCIP/NBT) Detection System (B1911, Merck). As a specificity control, the anti-FAS antiserum was preabsorbed with 1 µg/ml of the peptide antigen and used in place of the primary antibody.

2.9 Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2018). Section preparation performed the methods described in this study. For IHC staining, sections were treated with HistoVT One (Nacalai Tesque) to expose the antigens and then incubated with 3% H2O2 to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. To detect nucleus-incorporated bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), sections were further treated with 2N HCl to dissociate proteins bound to chromatin. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk powder for 1 hour, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody: anti-FAS antiserum (1: 2,000 dilutions with 1.5% nonfat milk powder) or anti-BrdU (MAB4072, Sigma-Aldrich; 1:1,000 dilution with 1.5% nonfat milk powder). The next day, sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution with 1.5% nonfat milk powder) at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein localization was visualized using the Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) kit (Vector Laboratories) and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. As a specificity control, the anti-FAS antiserum was preabsorbed with 1 µg/ml of the peptide antigen and used in place of the primary antibody.

2.10 Fatty acid synthase activity

The FAS activity assay was performed as previously described with minor modification (Ross et al., 2008). Oocytes of various sizes with associated follicle cells were independently isolated and stocked at -80°C. Samples were homogenized in lysis buffer, centrifuged (16,000 x g, 15 minutes), and the resulting supernatant was used for analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit. For the assay, supernatant was added to a reaction mixture containing 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 400 mM EDTA, 240 µM NADPH, and 30 µM acetyl-CoA, and incubated at 30°C for 10 minutes. Background NADPH oxidation was measured prior to the addition of malonyl-CoA. The enzymatic reaction was initiated by adding 100 µM of malonyl-CoA, and the decrease in optical density (OD) was recorded at 5 minutes intervals over 30 minutes using a microplate reader at 340 nm.

2.11 In vitro organ culture

Due to limitations in surgical techniques and the need for accurate identification of sexual characteristics, one-month-old squids were used for organ culture. Sex determination was based on relative gonadal size, with females exhibiting larger gonads than males. Specimens with large gonads (presumed ovaries) were selected for organ culture (n = 9 per group). Three ovarian samples were placed in each well of a 6-well plate. Ovaries were maintained in M199 medium supplemented with 3% (w/v) sea salt, 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU penicillin, and 100 ug/ml streptomycin. Notably, ovarian tissue exhibited widespread structural degradation after one week in culture (Supplementary Figure S1).

2.12 Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation in the ovary was assessed by the incorporation of BrdU. Ovaries were incubated with BrdU (60 µg/ml) for 24 hours prior to sampling under two different conditions: control and FAS function inhibition groups. To evaluate the inhibiting efficiency of the FAS inhibitor TVB-3166 (SML1694, Sigma-Aldrich), different concentrations ranging from 200 nM to 1.6 µM were tested using juvenile female ovaries containing primary oocytes. The FAS activity assay revealed that enzymatic activity was reduced by approximately 50% in the 200 nM treated group compared with the control. Increasing the concentration beyond 200 nM produced no further significant suppression of FAS activity. Therefore, in the FAS inhibition group, ovarian tissues were incubated with the FAS inhibitor TVB-3166 (1 µM) to inhibit FAS activity. Treatments were administrated for two-day intervals, and ovaries were collected on day 5 for analysis. Cell proliferation was evaluated using IHC staining as described in this study. The number of BrdU-incorporated cells was quantified to assess proliferative activity. Ovarian cell proliferation was represented as the relative number of BrdU-positive germline and somatic cells, respectively. For each group, three tissue samples were analyzed, with triplicate stained (4-6 serial sections on each slide) per sample.

2.13 Data analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Prior to conducting parametric tests, all datasets were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test. Values that met these assumptions were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey post hoc test, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was applied (P < 0.05), provided that normality and equal variance assumptions were satisfied. When assumptions were not met, appropriate non-parametric test, such as the Kruskal-Wallis test, were used.

3 Results

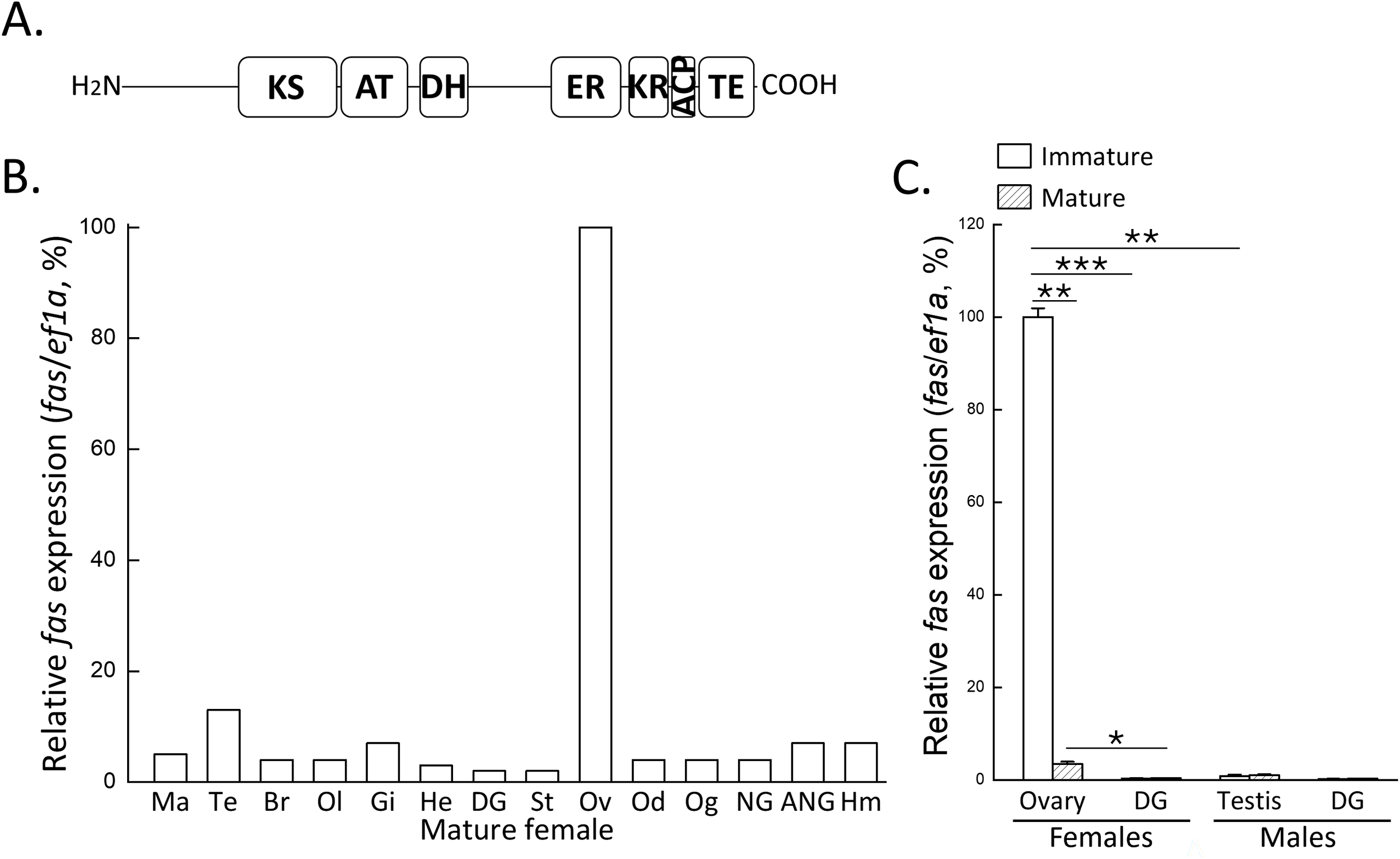

3.1 fas expression across different tissues

The sequence of fas gene was identified from the genome-annotated gene database (In preparation) of the bigfin reef squid. To confirm the sequence, the full-length cDNA was obtained by cloning. The gene contains an open reading frame encoding 3,043 amino acid residues. The deduced amino acid sequence includes conserved functional domains, including the ketosynthase (KS; 556-1026 aa), acyltransferase (AT; 1047-1362 aa), dehydratase (DH; 1450-1651), enoylreductase (ER; 2089-2405 aa), ketoreductase (KR; 2434-2613 aa), acyl carrier protein (ACP; 2676-2744 aa), and thioesterase (TE; 2784-3038 aa) (Figure 2A), which are structurally similar to those found in other species (Lin et al, 2024).

Figure 2

Domain structure of FAS and its mRNA expression profiles in tissues and reproductive stages. (A) Predicted domain structure of FAS, including ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), dehydratase (DH), enoylreductase (ER), ketoreductase (KR), acyl carrier protein (ACP), and thioesterase (TE). (B) qPCR analysis of fas mRNA expression in various tissues of mature female. (C) qPCR analysis of fas mRNA expression in gonads and digestive gland of immature and mature individuals of both sexes. Expression levels were normalized to ef1a, and the highest expression was set to 100%. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test: P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***). Ma, mantle; Te, tentacle; Br, brain; Ol, optic lobe; Gi, gill; He, heart; DG, digestive gland; St, stomach; Ov, ovary; Od, oviduct; Og, oviductal gland; NG, nidamental gland; ANG, accessory nidamental gland; Hm, hemocytes.

Tissue distribution of the fas gene in a mature female showed predominant expression in the ovary, with weak expression in other tissues, including the lipid-rich digestive gland (Figure 2B). To investigate the reproductive-associated expression pattern of fas, qPCR analysis was performed on gonads and digestive glands from both sexes at immature and mature stages. The result showed that fas expression was female-biased in the gonads, with the highest expression observed immature ovaries (Figure 2C). In contrast, fas expression in the digestive gland remained unchanged across reproductive stages in females (Figure 2C). These findings indicate that fas mRNA is specifically expressed in the ovary and not in lipid-rich tissues such as the digestive gland, which functions similarly to the hepatopancreas in invertebrates and liver in vertebrates.

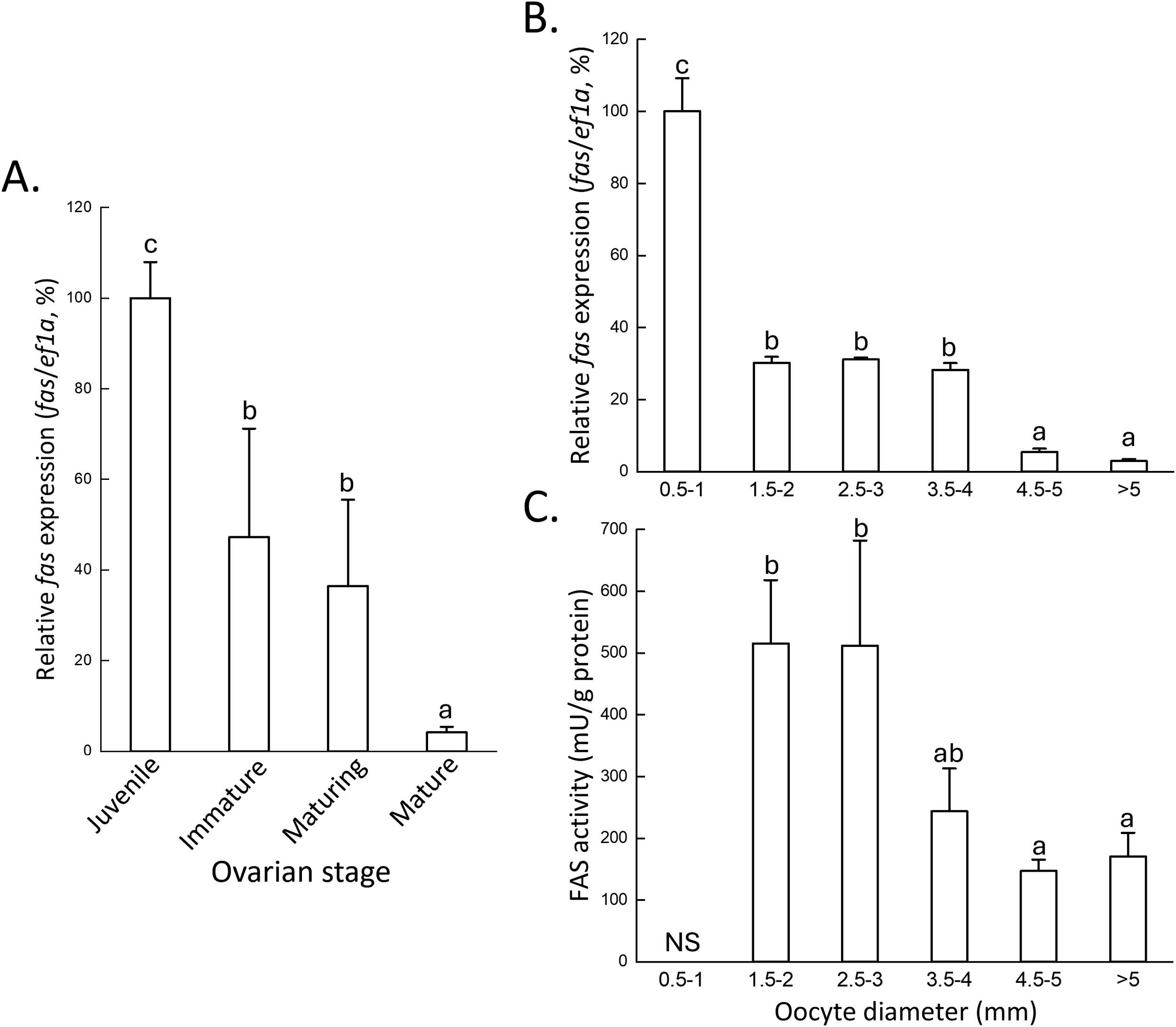

3.2 fas expression during oocyte development

To investigate the expression profile of fas during the reproductive cycle, ovaries at different development stages of ovaries were analyzed for fas mRNA levels. Based to the histological characteristics described in a previous study (Chen et al., 2018), four ovarian stages were defined in this study: juvenile females containing primary oocytes, immature females with previtellogenic oocytes, maturing females with early vitellogenic oocytes, and mature females with late vitellogenic oocytes. qPCR analysis revealed that fas mRNA expression was highest in juvenile females, decreased gradually during ovarian growth, and reached its lowest level in mature females (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

fas mRNA expression profiles and enzymatic activity across ovarian and oocyte stages. (A) qPCR analysis of fas mRNA expression in ovarian stages: juvenile (up to the primary oocyte), immature (up to the previtellogenic oocyte), maturing (up to the early vitellogenic oocyte), and mature (eggs in the oviductal gland). (B) qPCR analysis of fas mRNA expression. (C) FAS enzymatic activity in different oocyte stages. The relationship between oocyte size and stage is shown in Figure 1. Expression levels were normalized to ef1a, and the highest expression was set to 100%. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.05), indicated by different letters. NS, no sample.

We next examined the fas mRNA expression profile across different oocyte size classes, which correspond to specific developmental stages as described previously (Chen et al., 2018). qPCR results showed that fas expression was high in oocytes smaller than 1 mm, including oogonia, primary oocytes, and multiple follicular oocytes (Figure 3B). Expression levels declined significantly in oocytes ranging from 1.5 - 4 mm, which include previtellogenic (1.5-2 mm), early vitellogenic oocytes (2.5-3 mm, and some late vitellogenic oocytes (3.5-4 mm) (Figure 3B). The lowest expression levels were observed in oocytes larger than 4.5 mm, corresponding to late vitellogenic oocytes (4.5-5 mm) and fully mature (ripe) oocytes (>5 mm) (Figure 3B). Consistently, FAS protein exhibited the lowest fatty acid synthesis activity in oocytes larger than 3 mm, including late vitellogenic oocytes and ripe oocytes (Figure 3C). Together, these findings suggest that fas mRNA expression and its enzymatic activity are not positively correlated with de novo fatty acid synthesis during oocyte vitellogenesis.

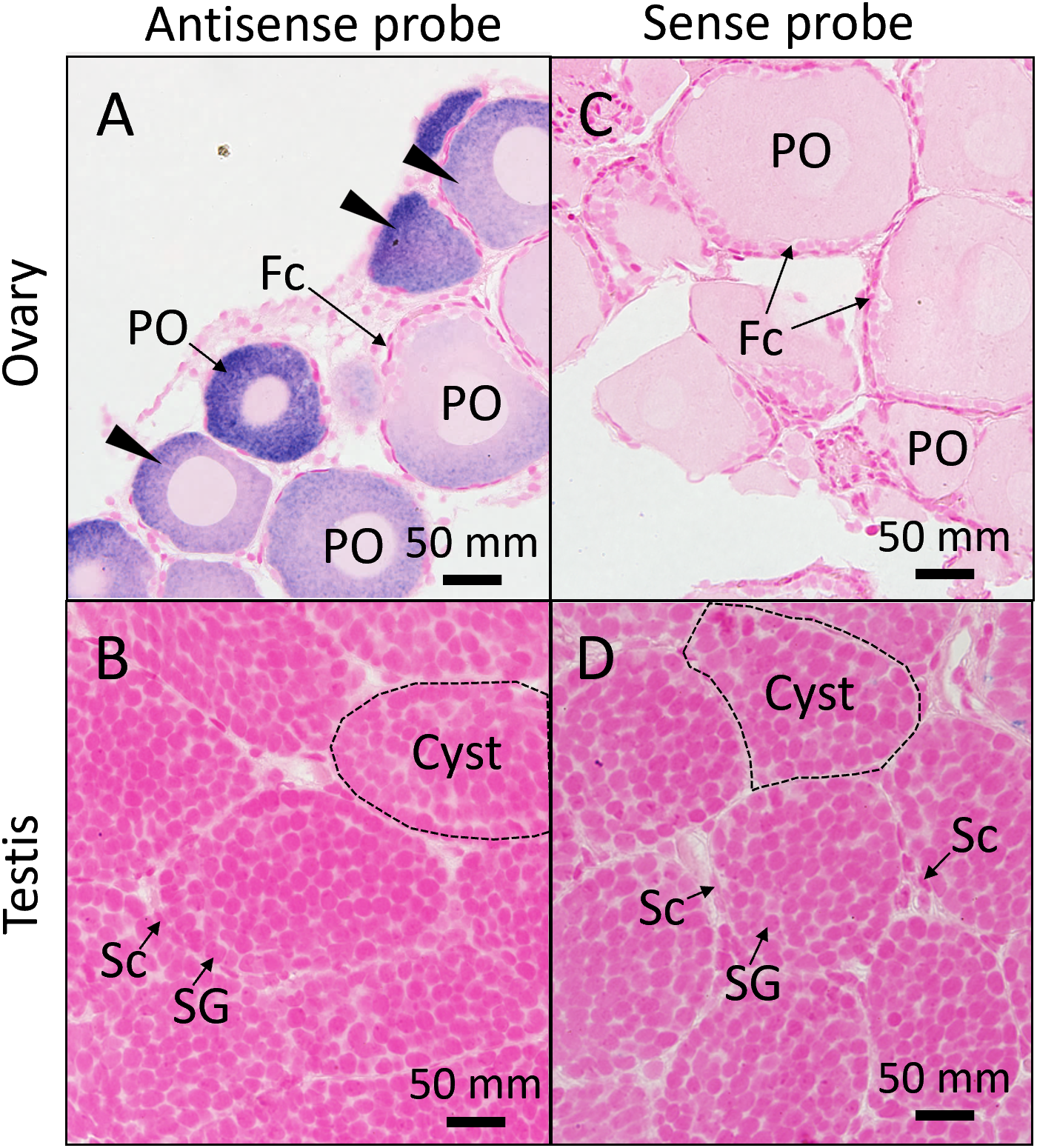

3.3 Localization of fas mRNA

To examine fas mRNA expression in specific gonadal cell types, WISH was performed on juvenile individuals, including ovaries at the primary oocytes stage, when fas transcript levels at high, and testes at the spermatogonia stage. In the ovary, WISH results showed strong fas mRNA expression in primary oocytes, with slight to no expression detected in surrounding somatic cells (Figure 4A). In the testis, fas mRNA expression was weak or nondetectable in both somatic and germline cells (Figure 4B). No signal was detected in testis and ovary with sense probe, respectively (Figures 4C, D). These results indicate that fas mRNA is specifically localized on oocytes.

Figure 4

Distribution of fas mRNA in juvenile gonads. In situ hybridization (ISH) with an antisense probe detected fas mRNA in the ovary (A) and testis (B) of juvenile individuals. Sense probes were used as negative control in the ovary (C) and testis (D). Black arrowheads indicate ISH signals. Fc, follicle cell; PO, primary oocyte; Sc, Sertoli cell; Sg, spermatogonia.

3.4 Specificity of the anti-FAS antiserum

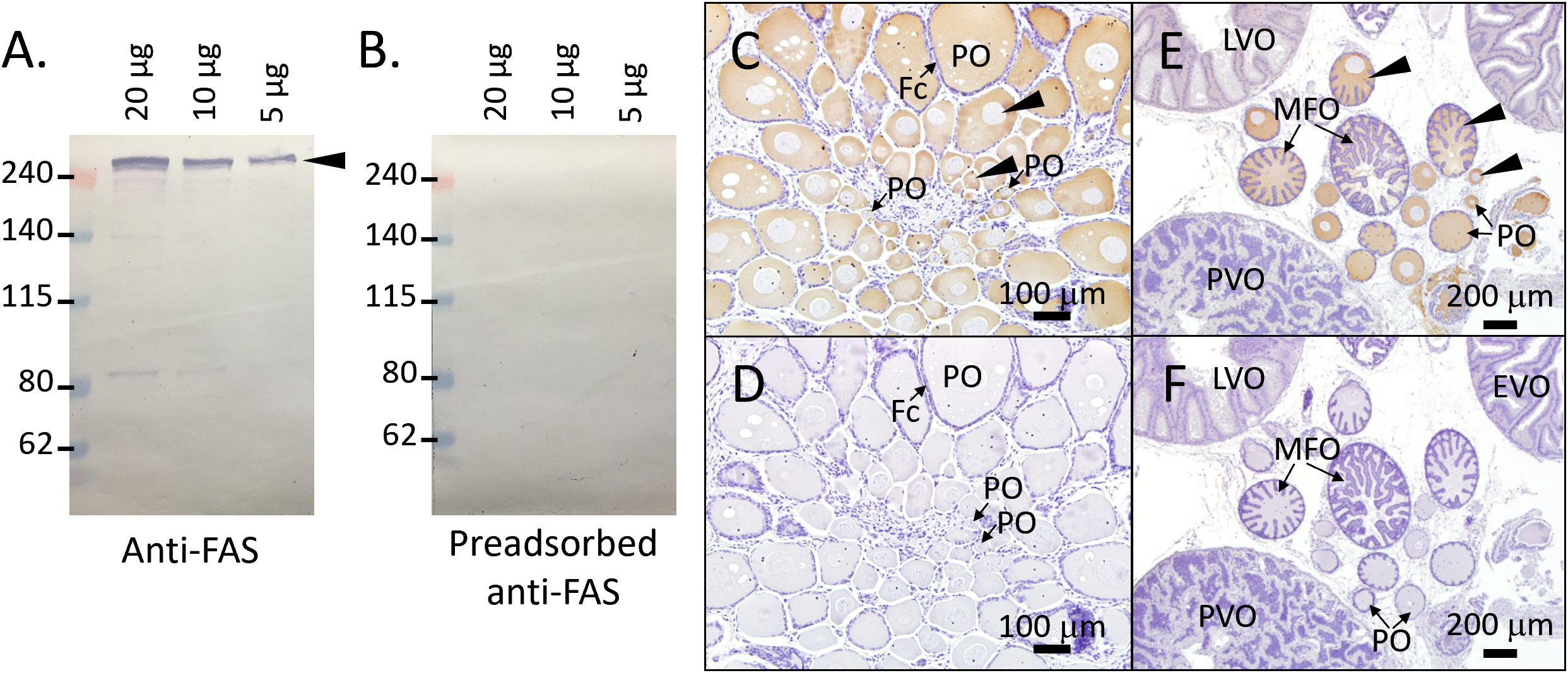

Based on analysis using the ExPASy compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/), theoretical molecular weight of the FAS protein was estimated to be approximately 337-kDa. The specificity of the anti-FAS antiserum was validated by WB analysis using oocyte extracts containing follicle cells from oocytes ranging in size from 1 to 2 mm. Immunoblotting revealed a single band larger than 240-D, corresponding to the predicted size of the FAS protein (Figure 5A). Notably, our protein ladder does not contain markers above 240-kDa, suggesting the detected band represents a high molecular weight protein. Furthermore, the FAS immunoblot signal was greatly reduced or absent when the antiserum was preadsorbed with its antigenic peptide (Figure 5B), confirming the specificity of the antibody. This result indicates that the anti-FAS antiserum specifically recognizes the FAS protein.

Figure 5

Specificity of anti-FAS antiserum and distribution of FAS protein in the ovary. (A) Western blotting (WB) with anti-FAS antiserum in ovarian protein extracts. (B) WB with preadsorbed anti-FAS antiserum (preincubated with immunizing peptides) as negative control. (C, E) Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with anti-FAS antiserum in juvenile (C) and mature (E) female squid. (D, F) Negative control IHC with preadsorbed anti-FAS antiserum in juvenile (D) and mature (F) females. Black arrowheads indicate FAS protein signals in WB and IHC. Fc, follicle cell; PO, primary oocyte; MFO, multiple follicular oocyte; PVO, previtellogenic oocyte; EVO, early vitellogenic oocyte; LVO, late vitellogenic oocyte.

3.5 Distribution of FAS protein

To examine the cellular localization of FAS protein, IHC staining was performed using a specific anti-FAS antiserum. In ovaries from juvenile females, FAS signals were strongly detected in primary oocytes, with weaker or nondetectable staining observed in oogonia (Figure 5C). In maturing females, strong FAS signals were observed in primary oocytes and multiple follicular oocytes, while weaker expression was detected in previtellogenic oocytes and oocytes at later stages (Figure 5D). No signal was detected when using the antigen-preabsorbed anti-FAS antiserum, confirming antiserum specificity (Figures 5E, F). Unexpectedly, IHC results show very weak FAS signals in previtellogenic oocytes, despite qPCR and enzymatic activity assay indicating a decrease in fas mRNA and FAS activity during later oocyte stages. This discrepancy may be due to the substantial increases in oocyte size, which could dilute the protein signal and reduce detection sensitivity.

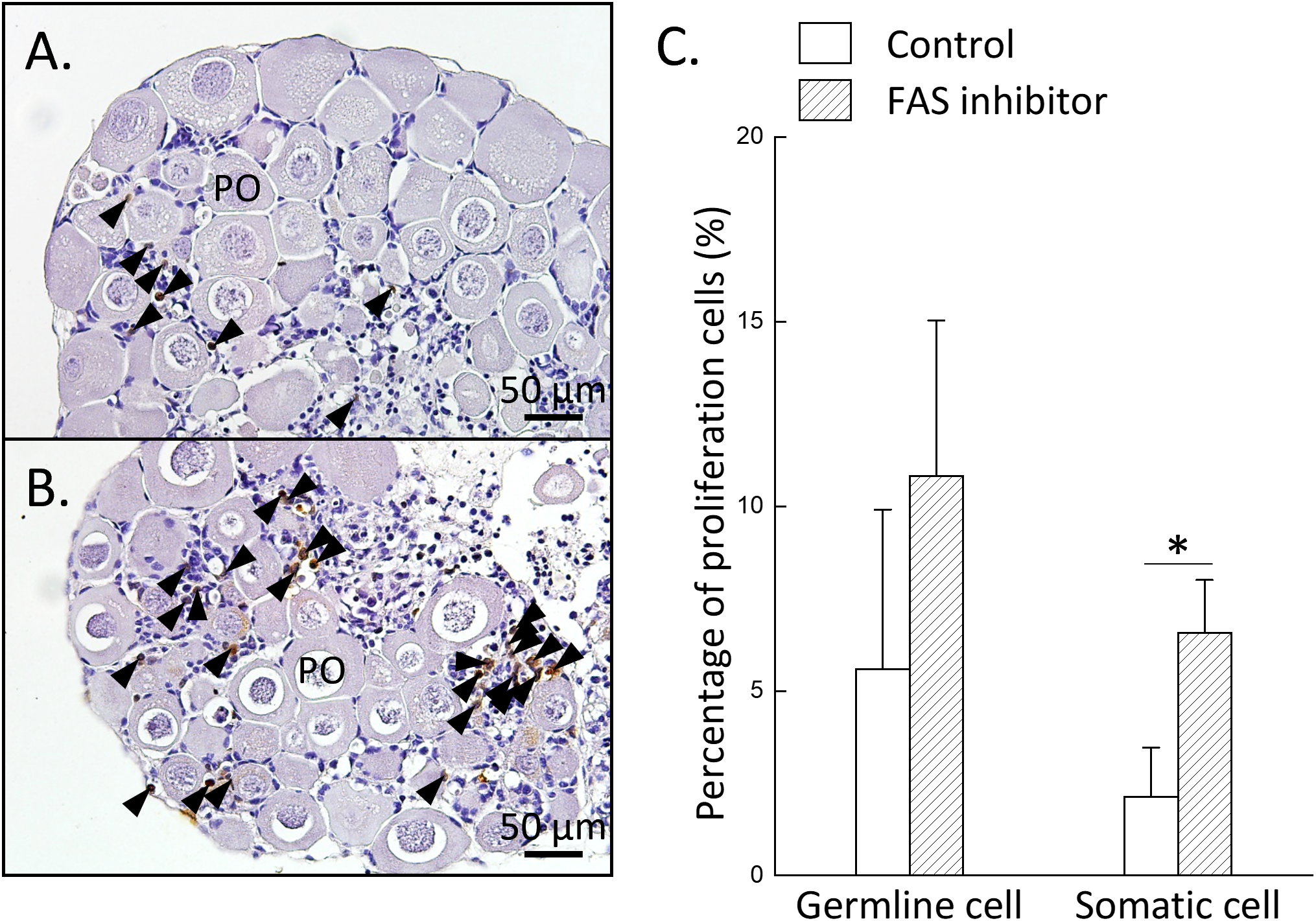

3.6 Inhibition of ovarian FAS activity

To further investigate the potential role of FAS in ovarian development, juvenile female ovaries were treated with TVB-3166. After incubation, histological analysis results revealed signs of tissue degradation in approximately 50% of ovaries across all groups. Only samples (n = 3 per group) that retained the most intact structures were selected for subsequent analyses. Cell proliferation was examined by BrdU incorporation using IHC staining. IHC revealed that BrdU-positive signals were mainly localized to somatic cells, with minimal labeling in germline cells across all groups (Figures 6A, B). The number of BrdU-positive somatic cells significantly increased in the FAS inhibition group (TVB-3166 treatment) compared to the control (Figure 6C). No significant difference in BrdU-positive germline cells were observed among the groups (Figure 6C). Altogether, these results suggest that de novo fatty acid synthesis in oocytes may regulate the proliferation of surrounding somatic cells.

Figure 6

Inhibition of FAS enzymatic activity increases somatic cell proliferation in the ovary. Ovarian tissues were divided into two groups: control and FAS-inhibited group (treated with 20 µM TVB-3166). (A, B) IHC staining of BrdU-incorporated cells in the control (A) and FAS-inhibited (B) groups. (C) Ovarian proliferative activity, evaluated as the relative percentage of BrdU-positive cells in both groups. Black arrowheads indicate BrdU-positive cells. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test: P < 0.05 (*). PO, primary oocyte.

4 Discussion

In this study, we used the bigfin reef squid as a model to investigate the potential role of de novo fatty acid synthesis during gonadal development. We analyzed fas mRNA expression profiles in various tissues of both sexes and found that high fas expression was observed in the ovaries, with only weak expression in other tissues, including the lipid-rich digestive gland (Figure 2). Our data also showed that fas mRNA exhibited female-bias expression in the gonads. Further analysis of fas expressions at different stages of ovarian development revealed that expression was highest in juvenile female ovaries and progressively decrease at later stages, reaching its lowest level in mature female ovaries (Figure 3). Additionally, fas expressions were examined across oocytes of different sizes. We found high expression in oocytes smaller than 1 mm, which contain oogonia, primary oocytes, and multiple follicular oocytes, with a gradual decrease in later stages (Figure 3). WISH and IHC analyses confirmed that fas mRNA and FAS protein were specifically localized in oocytes, particularly in primary and multiple follicular oocytes (Figures 4, 5). In vitro ovarian culture experiments showed that the inhibition of FAS activity led to increased proliferation of surrounding somatic cells (Figure 6). Together, these findings suggest that de novo fatty acid synthesis in oocytes plays a crucial role in regulating the proliferation of surrounding somatic cells during oocyte development.

4.1 Ovary as a major fatty acid synthesis organ in female cephalopods

Our findings indicate that fas mRNA is predominantly expressed in the ovary compared to other tissues, including the lipid-rich digestive gland, in squid. In contrast, fas mRNA is generally expressed at high levels in lipid-rich tissues such as the liver and adipose tissue in vertebrates (Cui et al., 2012; Mildner and Clarke, 1991; Peng et al., 2017; Sakae et al., 2020), and in the hepatopancreas and fat body of invertebrates (Nie et al., 2023; Song et al., 2022). Notably, only one study in crustaceans reported lower fas expression in the hepatopancreas compared to other tissues (Zuo et al., 2017). Therefore, ovary serving as the primary site of fatty acid synthesis in squid represents a unique case among animal species.

In most animals, excess energy derived from dietary intake is converted into lipid stores in lipid-rich tissues such as the liver in vertebrates (Arukwe and Goksøyr, 2003) or the hepatopancreas and fat body in invertebrates (Lee and Chang, 1999; Osada et al, 2004; Pan et al, 1969). These tissues function as major energy reservoirs that support reproduction, particularly during vitellogenesis in females. In contrast, cephalopods exhibit a distinct strategy: dietary lipids are rapidly transported from the digestive gland to other tissues for growth rather than being stored for later use in reproduction (Semmens, 1998). This immediate-use strategy may represent an evolutionary adaptation that promotes energy supply to oocytes through de no fatty acid synthesis.

Another possible reason for the active de novo fatty acid synthesis in squid oocytes may be linked to their unique folliculogenesis process. Unlike in many other animals, cephalopod oocytes are not only surrounded by follicle cells but also invaded by them, forming a special structure known as a follicular fold (Chen et al., 2018). This invasive process likely causes a substantial expansion of the oocyte’s surface area, thereby requiring enhanced lipid synthesis to support membrane formation. In mammals, FAS-synthesized fatty acids are known to play essential roles in membrane biosynthesis, particularly in rapidly proliferating cells such as cancer cells (Chen et al., 2014). Together, these findings suggest that the squid ovary serves as a primary site of fatty acid synthesis, likely supporting both oocyte development and membrane biogenesis in the absence of dedicated lipid storage tissues.

Specifically, we found that fas mRNA expression levels are elevated during the primary oocyte stage but significantly reduced at the later multiple follicular oocyte stage. Furthermore, inhibition of FAS activity at the primary oocyte stage promoted proliferation of ovarian somatic cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that reduced FAS activity, and the consequent decrease in fatty acid synthesis during oocyte development, may serve as a regulatory signal to enhance somatic cell proliferation.

4.2 Oocyte-synthesized fatty acids are not the major energy source stored in eggs

Yolk protein accumulation in oocytes plays a crucial role in energy storage for embryogenesis and larva survival in oviparous animals. The primary precursor of yolk protein is vitellogenin (VTG) (Hayward et al., 2010). In most vertebrates (Arukwe and Goksøyr, 2003; Guiguen et al., 2010) and insects (Pan et al., 1969; Wojchowski et al., 1986), VTG is synthesized in lipid-rich organs such as the liver and fat body, respectively. In other invertebrates, VTG mRNA expression has been observed in extraovarian tissues (e.g., the lipid-rich hepatopancreas) and/or the ovary itself (Review in Chen et al., 2018). Notably, in cephalopods, VTG mRNA expressions are specifically localized on the ovary. VTGs synthesized by ovarian follicle cells are accumulated in oocytes during vitellogenesis (Chen et al., 2018; Gaudron et al., 2005; Kitano et al., 2017). However, VTGs are absent from the hemolymph in mature female squids (Kitano et al., 2017), suggesting that VTGs are immediately transferred from follicle cells to oocytes without entering the systemic circulation.

In cephalopod, lipids account for a relatively small proportion (~15%) of the egg yolk compared to total proteins and carbohydrates (Matozzo et al., 2015). Although our findings show that oocytes are a major site of fatty acid production, with fas mRNA and protein highly expressed at early oocyte stages, these levels progressively decline during vitellogenesis and reach their lowest in late vitellogenic oocytes. In contrast, VTGs mRNA and protein expression are low in early oocytes but increase significantly during vitellogenesis (Chen et al., 2018; Kitano et al., 2017). These results suggest that VTGs synthesized by ovarian follicle cells are the primary contributor to energy storage in cephalopod eggs, whereas fatty acids synthesized by oocytes play a minimal role in this process.

4.3 Sex-dependent lipid metabolism in cephalopod gonads

In contrast to the ovary, which exhibited markedly higher fas mRNA expression than the lipid-rich digestive gland in females, fas expression in the testis was comparable to that in the digestive gland in males. These results indicate that the ovary serves as a primary site of de novo fatty acid synthesis in females, whereas this lipogenic pathway is not preferentially activated in testis. Consistent with this interpretation, higher lipid content has been reported in the digestive gland of females compared with males in both octopus (Estefanell et al., 2015; Rosa et al., 2004) and bigfin reef squid (our unpublished data). In contrast, lipid content was higher in the testis than in the ovary in octopus (Estefanell et al., 2015). Collectively, these findings suggest that, in males, gonadal lipid accumulation may rely primarily on lipid transport from the hepatopancreas rather than local de novo synthesis, whereas females preferentially activate ovarian lipogenesis to support oocyte development.

Further evidence for sex specific metabolic strategies comes from differences in fatty acid composition. In octopus, males exhibited higher levels of oleic acid (18:1 n-9), whereas females showed elevated eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 n-3) in the digestive gland, independent of feeding regime (Estefanell et al., 2015). Moreover, arachidonic acid (ARA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and palmitic acid (16:0) were predominant in testes, whereas ovaries were enriched in 16:0, DHA, and ARA (Estefanell et al., 2015). Together, these observations support the existence of sex-dependent lipid metabolic pathways in cephalopods, in which male gonad development may preferentially utilize lipid uptake and remodeling pathways rather than de novo fatty acid synthesis.

4.4 Conclusions

Achieving full-life-cycle aquaculture of the bigfin reef squid remains a major challenging, primarily due to the unreliable production of viable offspring in captivity. This includes issues such as precocious females laying small eggs, abnormal egg case structures, and the resulting low survival rate in subsequent captive generations. Unlike in vertebrates, where the roles of estrogen and androgen in sexual reproduction is well established, the functions of vertebrate-type sex steroids in invertebrates remain poorly understood (Fodor et al., 2020). To date, no studies in cephalopod have reported the regulatory pathway governing puberty and later sexual maturation in both sexes. In this study, we demonstrate that ovary serves as a primary site for fatty acid synthesis in cephalopods. While our results suggest a potential link between fatty acid synthesis and somatic cell proliferation, this relationship is currently correlative, and future studies are needed to establish causality. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the lipid-rich digestive gland and ovary may further clarify differences in lipid metabolism-related processes between these tissues. Although fas/FAS expression profiles during oocyte maturation were examined, the lipid content of eggs were not measured, limiting the direct extrapolation of our finding to lipogenesis during oocyte maturation. Consequently, while these findings provide a basis for exploring metabolic influences on reproductive physiology, any links to abnormal egg case structure or reduced survival in captive squid remain speculative and require further investigation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s. The validated gene sequences reported in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MG924746 (ef1a) and PX526114 (fas).

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by National Taiwan Ocean University International Animal Care and Use Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

H-WL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Y-CT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources. C-FC: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. G-CW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was partly supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 111-2326-B-019-001-MY3) and by the Center of Excellence for the Oceans, National Taiwan Ocean University, from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Marine Research Station, Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology, Academia Sinica, for preparing the juvenile squid for the organ culture experiments. We thank Mr. Pou-Long Kuan for his valuable assistance with squid husbandry. We thank Ms. Ying-Syuan Lyu for her assistance in organizing the references and formatting the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author Y-CT and C-FC declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1748686/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Degradation of ovarian tissue. After one week of in vitro organ culture, most ovarian tissues exhibited marked morphological expansion. Histological analysis revealed abnormal oocytes characterized by reduced size.

References

1

Alabaster A. Isoe J. Zhou G. Lee A. Murphy A. Day W. A. et al . (2011). Deficiencies in acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase 1 differentially affect eggshell formation and blood meal digestion in Aedes aEgypti. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol.41, 946–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.09.004

2

Arukwe A. Goksøyr A. (2003). Eggshell and egg yolk proteins in fish: hepatic proteins for the next generation: oogenetic, population, and evolutionary implications of endocrine disruption. Comp. Hepatol.2, 4. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-4

3

Baron D. Houlgatte R. Fostier A. Guiguen Y. (2008). Expression profiling of candidate genes during ovary-to-testis trans-differentiation in rainbow trout masculinized by androgens. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.156, 369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.01.016

4

Bianchi A. Evans J. L. Iverson A. J. Nordlund A. C. Watts T. D. Witters L. A. (1990). Identification of an isoenzyme from of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J. Biol. Chem.265, 1502–1509. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40045-8

5

Boucaud-Camou E. V. E. Boucher-Rodoni R. (1983). “ Feeding and Digestion in Cephalopods,” in The Mollusca, vol. 5 . Eds. SaleuddinA. S. M.WilburK. M. ( Academic Press, San Diego), 149–187.

6

Chen C. Li H. W. Ku W. L. Lin C. J. Chang C. F. Wu G. C. (2018). Two distinct vitellogenin genes are similar in function and expression in the bigfin reef squid Sepioteuthis lessoniana. Biol. Reprod.99, 1034–1044. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy131

7

Chen C. C. Lin J. T. Cheng Y. F. Kuo C. Y. Huang C. F. Kao S. H. et al . (2014). Amelioration of LPS-induced inflammation response in microglia by AMPK activation. BioMed. Res. Int.2014, 692061. doi: 10.1155/2014/692061

8

Cui H. X. Zheng M. Q. Liu R. R. Zhao G. P. Chen J. L. Wen J. (2012). Liver dominant expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS) gene in two chicken breeds during intramuscular-fat development. Mol. Biol. Rep.39, 3479–3484. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1120-8

9

Dunn T. G. Moss G. E. (1992). Effects of nutrient deficiencies and excesses on reproductive efficiency of livestock. J. Anim. Sci.70, 1580–1593. doi: 10.2527/1992.7051580x

10

Estefanell J. Socorro J. Izquierdo M. Roo J. (2015). Effect of two fresh diets and sexual maturation on the proximate and fatty acid profile of several tissues in Octopus vulgaris: specific retention of arachidonic acid in the gonads. Aquac. Nutr.21, 274–285. doi: 10.1111/anu.12163

11

Fodor I. Urbán P. Scott A. P. Pirger Z. (2020). A critical evaluation of some of the recent so-called ‘evidence’ for the involvement of vertebrate-type sex steroids in the reproduction of mollusks. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.516, 110949. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110949

12

Gaudron S. M. Zanuttini B. Henry J. (2005). Yolk protein in the cephalopod, Sepia officinalis: a strategy for structural characterisation. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev.48, 129–135. doi: 10.1080/07924259.2005.9652179

13

Guiguen Y. Fostier A. Piferrer F. Chang C. F. (2010). Ovarian aromatase and estrogens: a pivotal role for gonadal sex differentiation and sex change in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.165, 352–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.03.002

14

Günenc A. N. Graf B. Stark H. Chari A. (2022). “ Fatty Acid Synthase: Structure, Function, and Regulation,” in Macromolecular Protein Complexes IV, vol. 99 . Eds. HarrisJ. R.Marles-WrightJ. (Springer, Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 1–33.

15

Hayward A. Takahashi T. Bendena W. G. Tobe S. S. Hui J. H. L. (2010). Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of vitellogenin and other large lipid transfer proteins in metazoans. FEBS Lett.584, 1273–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.056

16

Huang J. D. Lee S. Y. Chiang T. Y. Lu C. C. Lee M. F. (2018). Morphology of reproductive accessory glands in female Sepia pharaonis (Cephalopoda: Sepiidae) sheds light on egg encapsulation. J. Morphol279, 1120–1131. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20835

17

Ikeda Y. Ueta Y. Anderson F. E. Matsumoto G. (2009). Reproduction and life span of the oval squid Sepioteuthis lessoniana (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae): comparison between laboratory-cultured and wild-caught squid. Mar. Biodivers. Rec2, e50. doi: 10.1017/S175526720900061X

18

Jiang M. Chen Q. Zhou S. Han Q. Peng R. Jiang X. (2021). Optimum weaning method for pharaoh cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis Ehrenberg 1831, in small- and large-scale aquaculture. Aquac. Res.52, 1078–1087. doi: 10.1111/are.14963

19

Kitano H. Nagano N. Sakaguchi K. Matsuyama M. (2017). Two vitellogenins in the loliginid squid Uroteuthis edulis: Identification and specific expression in ovarian follicles. Mol. Reprod. Dev.84, 363–375. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22786

20

Lee F. Y. Chang C. F. (1999). Hepatopancreas is the likely organ of vitellogenin synthesis in the freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. J. Exp. Zool284, 798–806. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19991201)284:7<798::AID-JEZ10>3.0.CO;2-C

21

Lee Y. C. Tang L. L. Yeh Y. C. Li H. W. Ke H. M. Yang C. J. et al . (2025). Detection of genetic sex using a qPCR-based method in the bigfin reef squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana). Aquac. Rep.40, 102644. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2025.102644

22

Li F. Chen S. Zhang T. Pan L. Liu C. Bian L. (2024). Gonadal transcriptome sequencing analysis reveals the candidate sex-related genes and signaling pathways in the east asian common octopus, Octopus sinensis. Genes15, 682. doi: 10.3390/genes15060682

23

Li H. W. Chen C. Kuo W. L. Lin C. J. Chang C. F. Wu G. C. (2019). The characteristics and expression profile of transferrin in the accessory nidamental gland of the bigfin reef squid during bacteria transmission. Sci. Rep.9, 20163. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56584-8

24

Li H. W. Kuo W. L. Chen C. Tseng Y. C. Chang C. F. Wu G. C. (2022a). The characteristics and expression profile of peptidoglycan recognition protein 2 in the accessory nidamental gland of the bigfin reef squid during bacterial colonization. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.825267

25

Li Y. Liu L. Zhang L. Wei H. Wu S. Liu T. et al . (2022b). Dynamic transcriptome analysis reveals the gene network of gonadal development from the early history life stages in dwarf surfclam Mulinia lateralis. Biol. Sex Differ13, 69. doi: 10.1186/s13293-022-00479-3

26

Lin Z. Li F. Krug P. J. Schmidt E. W. (2024). The polyketide to fatty acid transition in the evolution of animal lipid metabolism. Nat. Commun.15, 236. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44497-0

27

Lum-Kong A. (1992). A histological study of the accessory reproductive organs of female Loligo forbesi (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae). J. Zool226, 469–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb07493.x

28

Matozzo V. Conenna I. Riedl V. M. Marin M. G. Marčeta T. Mazzoldi C. (2015). A first survey on the biochemical composition of egg yolk and lysozyme-like activity of egg envelopment in the cuttlefish Sepia officinalis from the Northern Adriatic Sea (Italy). Fish Shellfish Immunol.45, 528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.04.026

29

Mildner A. M. Clarke S. D. (1991). Porcine fatty acid synthase: cloning of a complementary dna, tissue distribution of its mrna and suppression of expression by somatotropin and dietary protein. J. Nutr.121, 900–907. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.6.900

30

Nie H. Lu Z. Li D. Dong S. Li N. Chen W. et al . (2023). The potential roles of fatty acid metabolism-related genes in Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum under cold stress. Aquaculture562, 738750. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738750

31

Osada M. Harata M. Kishida M. Kijima A. (2004). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of vitellogenin in scallop, Patinopecten yessoensis (bivalvia, mollusca). Mol. Reprod. Dev.67, 273–281. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20020

32

Pan M. L. Bell W. J. Telfer W. H. (1969). Vitellogenic blood protein synthesis by insect fat body. Science165, 393–394. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3891.393

33

Peng S. Shi Z. Gao Q. Zhang C. Wang J. (2017). Dietary n-3 LC-PUFAs affect lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) activities and mRNA expression during vitellogenesis and ovarian fatty acid composition of female silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) broodstock. Aquac. Nutr.23, 692–701. doi: 10.1111/anu.12436

34

Rosa R. Costa P. R. Nunes M. L. (2004). Effect of sexual maturation on the tissue biochemical composition of Octopus vulgaris and O. defilippi (Mollusca: Cephalopoda). Mar. Biol.145, 563–574. doi: 10.1007/s00227-004-1340-8

35

Ross J. Najjar A. M. Sankaranarayanapillai M. Tong W. P. Kaluarachchi K. Ronen S. M. (2008). Fatty acid synthase inhibition results in a magnetic resonance-detectable drop in phosphocholine. Mol. Cancer Ther.7, 2556–2565. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0015

36

Sakae Y. Oikawa A. Sugiura Y. Mita M. Nakamura S. Nishimura T. et al . (2020). Starvation causes female-to-male sex reversal through lipid metabolism in the teleost fish, medaka (Olyzias latipes). Biol. Open9, bio050054. doi: 10.1242/bio.050054

37

Semmens J. M. (1998). An examination of the role of the digestive gland of two loliginid squids, with respect to lipid: storage or excretion? Proc. R. Soc London B. Biol. Sci.265, 1685–1690. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0489

38

Semmens J. M. (2002). Changes in the digestive gland of the loliginid squid Sepioteuthis lessoniana (Lesson 1830) associated with feeding. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol.274, 19–39. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00165-X

39

Smith S. Witkowski A. Joshi A. K. (2003). Structural and functional organization of the animal fatty acid synthase. Prog. Lipid Res.42, 289–317. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(02)00067-X

40

Song Y. Gu F. Liu Z. Li Z. Wu F. Sheng S. (2022). The key role of fatty acid synthase in lipid metabolism and metamorphic development in a destructive insect pest, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 9064. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169064

41

Teaniniuraitemoana V. Huvet A. Levy P. Klopp C. Lhuillier E. Gaertner-Mazouni N. et al . (2014). Gonad transcriptome analysis of pearl oyster Pinctada margaritifera: identification of potential sex differentiation and sex determining genes. BMC Genomics15, 491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-491

42

Tong L. (2013). Structure and function of biotin-dependent carboxylases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.70, 863–891. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1096-0

43

Vidal E. A. G. Villanueva R. Andrade J. P. Gleadall I. G. Iglesias J. Koueta N. et al . (2014). “ Cephalopod Culture: Current Status of Main Biological Models and Research Priorities,” in Advances in Marine Biology, vol. 67 . Ed. VidalE. A. G. (United States: Academic Press), 1–98.

44

Wojchowski D. M. Parsons P. Nordin J. H. Kunkel J. G. (1986). Processing of pro-vitellogenin in insect fat body: a role for high-mannose oligosaccharide. Dev. Biol.116, 422–430. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90143-0

45

Zuo H. Gao J. Yuan J. Deng H. Yang L. Weng S. et al . (2017). Fatty acid synthase plays a positive role in shrimp immune responses against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol.60, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.11.054

Summary

Keywords

fatty acid synthase, folliculogenesis, lipogenesis, oocyte, ovary

Citation

Li H-W, Tseng Y-C, Chang C-F and Wu G-C (2026) Potential role of oocyte-intrinsic fatty acid synthesis in ovarian development of the bigfin reef squid Sepioteuthis lessoniana. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1748686. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1748686

Received

18 November 2025

Revised

29 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Enric Gisbert, Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology (IRTA), Spain

Reviewed by

Adnan H. Gora, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR), India

Carlos Alfonso Alvarez-González, Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Tseng, Chang and Wu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guan-Chung Wu, gcwu@mail.ntou.edu.tw

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.