Abstract

As the scale and complexity of the RAS (Recirculatory Aquaculture System) on land is increasing, aquaculture is expanding into the more energetic offshore environments. This shifting trend increases the requirement of continuous monitoring of wave, current, cage depth, structural load, flow, pressure and mesh level in cages, tanks and pipes. Use of conventional instruments is constrained to the reliance on cables, high power, limited space coverage and losses of performance due to biofouling and corrosion. As a result, they often cannot provide the continuous data input required for modern operational control. This review aims to highlight the recent progress in hydrodynamic and infrastructure sensing by various types of nanomaterials in marine aquaculture. Nanostructured coatings and functionalized optical fibers from nanomaterials have increased anti-fouling resistance and have allowed distributed measurements surrounding cages, tanks and reservoirs. Two-dimensional materials, such as graphene, MXenes and laser-induced graphene support conformal strains and pressure sensing devices that follow the geometry of the structural components while monitoring isolated point devices. Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) allow self-sensing of wave energy, currents, flows and levels by converting mechanical motion into electrical signals. Altogether, these approaches point to a future of self-powered surveillance on infrastructure surfaces and networks. We discuss the remaining gaps in validating these nanomaterial-based devices on long-term uses, the robustness of packaging and adhesion under immersion, and the selection of calibration and standardized performance indicators on real farm operating conditions.

1 Introduction

Aquaculture has moved from a fringe activity to the major source of aquatic animal food globally (Golden et al., 2021). Global aquaculture production values accounted for over 365 billion USD in 2023, demonstrating their significance in solving global food issues (Tacon et al., 2025). As terrestrial lands become more congested globally, aquaculture farms move to offshore waters, which are exposed and more energetic. At the same time, farms face stringent environmental regulation, extreme events and increasing pressure to reduce effluent discharges, benthic disturbance and nutrient loads (Hamdhani et al., 2020; Somers et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2004; Kennish, 2002). Meeting these demands requires an infrastructure that is both bigger and safer, smarter and continually monitored.

The core challenges, therefore, include hydrodynamics and structural reliability (Mi et al., 2025). Flexible array of cages are subject to disturbances from waves, currents, winds, and fish-induced loads. When these loads are not managed properly, they lead to net deformation, mooring fatigue, overtopping and tearing, and triggers fishes escape (Wang et al., 2024). These risks, therefore, demand structural health monitoring, oceanographic instrumentation, and digital-twin frameworks that link environmental forcing to cage behavior and farm hydraulics (Su et al., 2023). However, in practice, most sensing techniques are still based on a limited number of rigid, fixed location, and often cabled devices (Figure 1). These include acoustic Doppler profilers, wave buoys, pressure gauges, and inertial sensors (Katsidoniotaki et al., 2025; Pereiro et al., 2023; Abrahamsen et al., 2025).

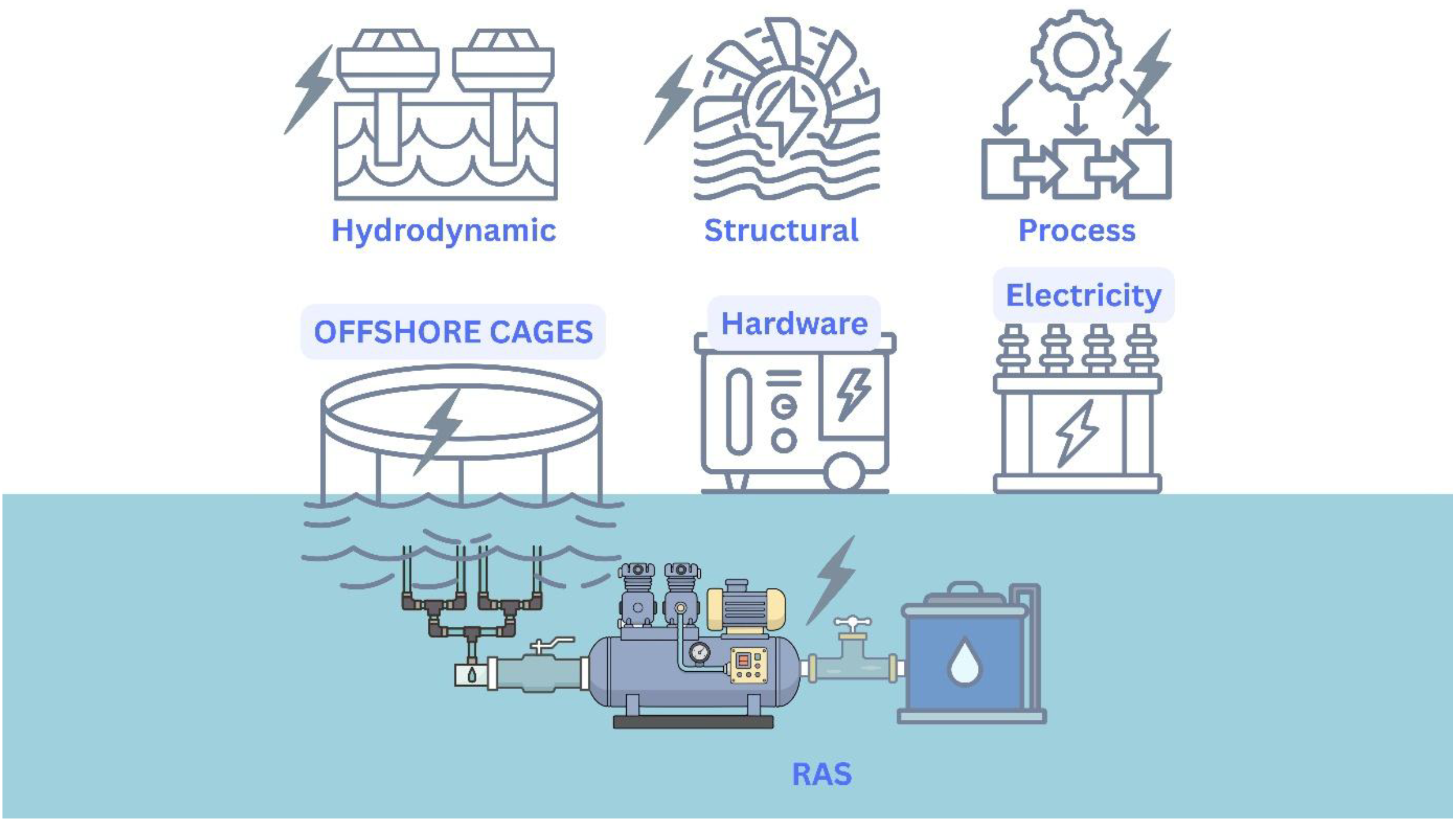

Figure 1

An overview of the monitoring equipment used in offshore cages and land-based RAS: The figure groups the requirements into three primary domains, namely hydrodynamic, structural, and operational monitoring. In practice, these functions still rely on bulky conventional instrumentation and supporting infrastructure. These require frequent maintenance and remain vulnerable to biofouling and other durability challenges, including in offshore cage environments. These shortcomings require the development of novel materials and technologies that can create more compact, robust, and deployment-ready monitoring solutions.

Each of these instruments measures a local variable at one specific location, often requires dedicated power and communication, and is expensive to deploy on a large-scale farming. Biofouling, corrosion, mechanical damage, and long cables increase drag, complicate installation and add failure points (Sahoo et al., 2025; Hopkins et al., 2021; Delgado et al., 2021; Corredor, 2018; Parra et al., 2018; Heasman et al., 2024). Therefore, many farms rely on a limited number of sets as intermittently operated sensors (Parra et al., 2018). Such limited number of sensors often cannot provide the continuous dataset required for autonomous vehicles, as well as real-time control of cage depth, aeration, and feeding (Oliveira et al., 2020). Model-based monitoring frameworks in aquaculture carries immense importance as it demonstrates the value of combining continuous structural and environmental data with numerical models. But their use is still constrained by the cost, energy requirements and the durability of conventional sensing elements (Verma et al., 2024).

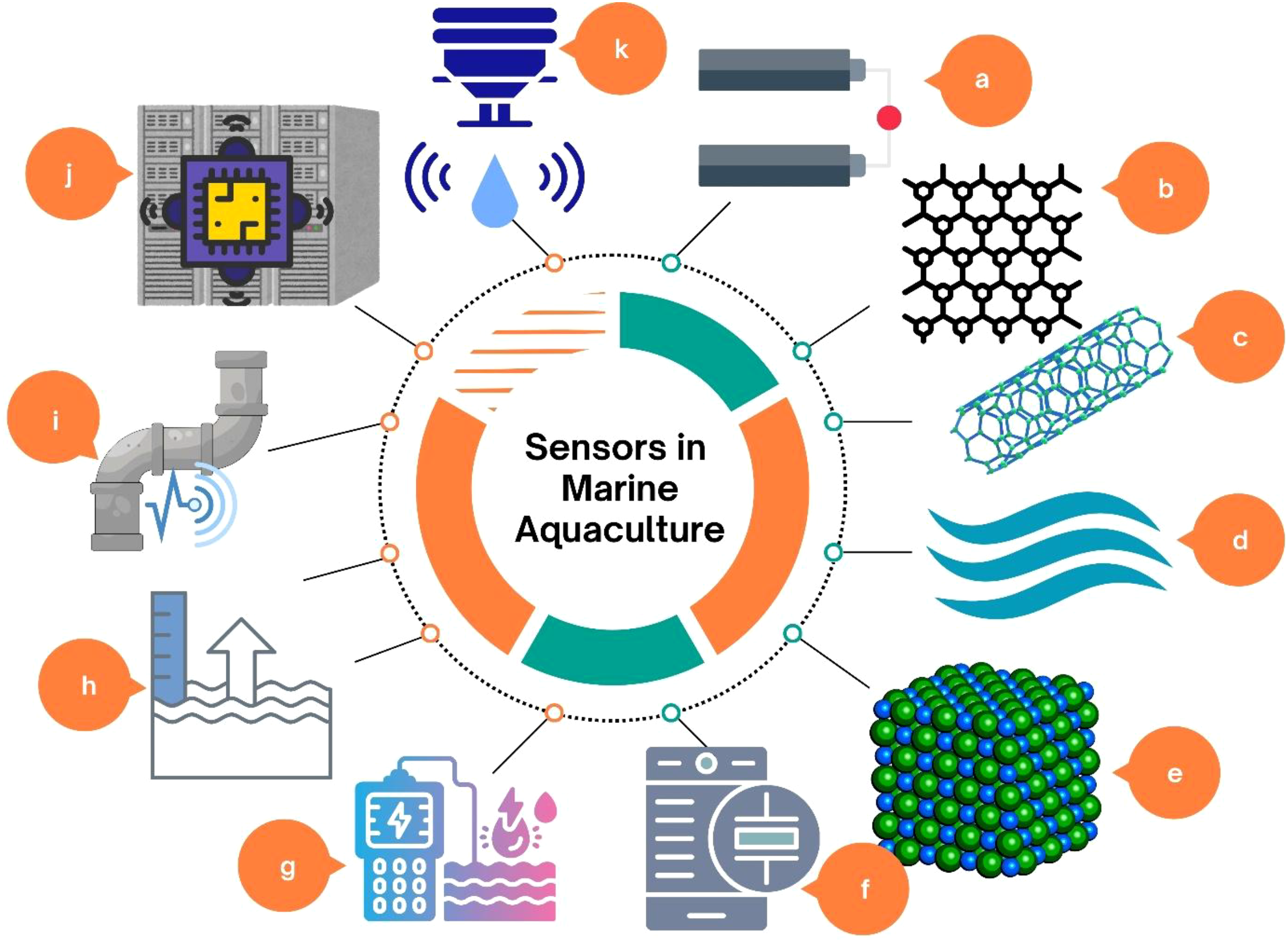

In this regard, nanomaterials provide important platforms for sensing in marine aquaculture. These range from design of individual electrodes to cage structures and structural pipework (Figure 2). Nanostructured metallic, metal oxides, ceramic, and polymer coatings have the potential to reduce biofouling and degradation of surfaces of the sensors and instruments. This can increase the lifespan and stability of the sensors. When applied to optical fibers, nanostructures strengthen the interaction between light and water. This can improve sensitivity for the measurements of depth, temperature, and immersion state. These advantages are especially important in mariculture, where monitoring processing systems must deliver stable measurements over long deployments in biofouling-prone waters (Fajardo et al., 2022; Silvanir et al., 2024; Sharjeel et al., 2024).

Figure 2

Overview of nanomaterial-enabled sensing technologies in marine aquaculture: The schematic highlights major enabling platforms, including (a) triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) as self-powering interfaces and representative nanomaterial building blocks such as (b) graphene and other 2D materials, (c) carbon nanotubes, (d) MXenes, and (e) nanoparticle and nanocomposite assemblies. These platforms support a broad sensor toolbox for farm and facility monitoring, including (f) biofouling surveillance, (g) core water-quality parameters, (h) water level and depth, (i) pipe and hydraulic process variables such as flow, pressure, and leakage, (j) structural condition tracking such as strain, cracking, or component malfunction, and (k) real-time signal processing and data transmission through integrated hardware and IoT-ready architectures. The figure summarizes how material choice, device design, and power strategy converge to enable more compact, robust, and field-deployable monitoring systems for offshore cages and land-based RAS.

In addition, two-dimensional (2D) nanostructured materials such as graphene, MXenes and conductive nanocomposites provide a flexible basis for mechanical and process sensing. Patterned films of these materials can act as strain and pressure sensors on cage rings, moorings and pipe surfaces. More importantly, the developed sensors follow the geometry of the structural components well. When applied as thin coatings, they can register signals related to changes in loading or motion while remaining lightweight and mechanically robust. In marine aquaculture, these features make 2D and nanocomposite conductors attractive candidates for a family of sensors which can be deployed across cages, tanks and pipework (Zhang et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2023; Jaffari et al., 2021).

Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) provide another complementary route by linking sensing directly to local energy harvesting. They convert low-frequency mechanical motions, such as winds, waves, currents, and mechanical vibrations into electrical signals. Additionally, they generate usable power through contact electrification between polymer and electrode surfaces (Fan et al., 2016). So, in marine settings, TENG devices can be configured as buoys, in-line harvesters, or current meters which can both track motion and generate power for nearby electronics (Xia et al., 2023). Several studies have reported that wave-driven TENGs can support simple sensor nodes or indicators using the wave energy, thereby with lesser dependency on shore-based power supplies or frequent battery replacements (Radhakrishnan et al., 2022). Together with nanomaterials and 2D conductors, TENGs support partially self-powered monitoring surfaces integrated into cages, tanks, and pipework (Cheng et al., 2023). The sections following herein examine how these different techniques and materials are being combined and where key gaps remain for robust large-scale deployment.

2 Durable distributed sensing using nanocoatings and optical fibers

2.1 Offshore aquaculture and recirculating aquaculture systems

Sensor deployments for Hydrodynamic and infrastructure in marine aquaculture environments must withstand the biofouling-prone waters and demanding maintenance conditions (Hopkins et al., 2021). Nanostructured metals, ceramics, and polymer coatings help address this durability barrier by reducing biofouling and surface degradation (Liang et al., 2024). This can enhance both the stability and lifespans of the sensors used. The same can be applied to both offshore cages and land-based RAS (Recirculating Aquaculture System) infrastructure, where conventional equipment often fails due to fouling, corrosion, and mechanical stress.

2.2 Nanomaterial enabled optical fiber networks for smart cages

Nanomaterial decorated optical fiber sensors extend this platform into distributed surveillance applications. Bare optical fibers are highly resistant to electromagnetic interference and support long-distance multiplexing as well (Wang et al., 2021). Nanoscale coatings and structured films can expand sensing coverage, and multi-parameter capability around the deployed cages. Nanomaterial coatings, including metallic and semiconductor nanoparticles and other nanostructured films, can be applied to the selected fiber regions (Ielo et al., 2021). By amplifying the evanescent field and localized surface plasmon resonance effects, particularly from noble metal nanostructures, these coatings can enhance the sensitivity to refractive index, and, depending on the configuration, strain, and temperature (Li et al., 2022; Urrutia et al., 2015). As a result, nanocoated fiber loops attached to cage rings and anchors can record a number of physical parameters, such as, distributed strain, vibration, and pressure; thereby complementing point measurements from wave and current sensors.

2.3 Distributed tank and sump sensing with nanomaterial enabled optical fibers

Similar strategies can also be applied to tanks and reservoirs. Optical fiber level sensors benefit from nanomaterial integration. Coatings containing noble metal nanoparticles, or ITO (Indium Tin Oxide), enhance plasmonic resonances and the evanescent field, making spectral signals more sensitive to changes in the immersion state (Urrutia et al., 2015; Lopez et al., 2021). Distributed Rayleigh-backscattering approaches have demonstrated continuous level detection along fibers in cryogenic systems (Chi et al., 2022; Jauregui-Vazquez et al., 2021). The same design logic could enable spatially resolved level profiles in aquaculture with no moving parts. It could also provide a multiplexed backbone for broader infrastructure monitoring.

3 2D-materials for flexible multi-point pressure and strain sensing

Two-dimensional (2D) and related material platforms, such as grapheme (Kong et al., 2023), MXenes (Lai et al., 2023), and laser-induced grapheme (Zhang et al., 2023b) (LIG) offer a flexible base for mechanical and process sensors that follows complex structures. Their main advantage is geometric conformity. Patterned films can be used as strain and pressure sensors on various elements, such as, cage rings, moorings, and pipe surfaces. These allow sensors to track the structure rather than being limited to single-point sensor housings.

3.1 Monitoring pressure and depth in cages

Depth and pressure measurements are important as they can help operators keep cages at targeted depths which can limit exposure to hypoxic or thermally stratified layers (Sievers et al., 2022). Graphene, MXenes, and LIG can offer higher sensitivity, and can be packaged for better signal stability, compared with traditional rigid pressure elements (Sun et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2022a). Graphene-based pressure sensors typically use atomically thin, highly conductive films whose resistance or capacitance changes under small deformations (Deshmukh et al., 2023). Multilayer graphene foams, textiles, and patterned films can detect pressures from a few pascals to hundreds of kilopascals, while maintaining fast response and mechanical flexibility (Tian et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2024).

Laser-induced graphene (LIG) pressure sensors can be patterned directly onto polymer substrates. This, in turn, can create flexible and corrosion-tolerant devices. These sensors have been tested as depth probes in seawater. Protective polymer composite coatings can further improve the resistance to chemical degradation and biofouling, thereby helping maintain long-term stable performance (Volkenburg et al., 2023; Kaidarova et al., 2020). When laminated onto cage frames, mooring lines, or submersible collars, LIG sensors could provide information on spatially resolved depth and pressure.

MXenes, two-dimensional transition-metal carbides and nitrides, also support flexible pressure and strain sensing (Huang et al., 2018). Their conductivity, tunable surface terminations, and lamellar structure enable sensitive piezoresistive responses across wide ranges of pressure often along with good cycling stability (Lu et al., 2020). Pressure-sensitive underwater fabrics coated with nanocomposites have been reported to maintain stable performance during submersion (Fan et al., 2022). This suggests that MXene or MXene-hybrid sensors could be designed to conform to nets, bags, or tank walls. In offshore cages, these approaches could enable whole-cage, multi-point monitoring and finer control of submergence during harmful algal blooms, surface warming, or extreme wave events.

3.2 Monitoring structural strain in cages

Nanomaterial-based pressure and strain sensors can allow the decorated structure itself to act as a distributed sensing surface. MXene- and graphene-based strain gauges can be printed onto or mounted on mooring chains, brackets, or composite beams. These gauges can detect small deformations created by changes in drag forces (Grabowski et al., 2022; Khalid et al., 2025). These signals can be combined with the measurements from waves and currents by TENG buoys or optical fiber arrays. This allows operators to estimate the hydraulic resistance and drag buildup. This supports predictive cleaning and properly timed schedules in changing the net.

3.3 Structural self-sensing and flow monitoring in RAS

Process and infrastructure sensors in RAS were primarily designed for rigid, bulk, cabled and single-point measurements. Conventional flow meters and diaphragm pressure gauges with wetted interfaces are vulnerable to fouling and scaling. Equally, they are costly and complex to deploy at high densities (Delgado et al., 2021). Two-dimensional materials offer an alternative path toward conformal and distributed sensing surfaces.

Nanomaterials enable electrodes monitoring chemistry and hydraulics within the same flow environment. Graphene and related 2D materials can be patterned onto flow cell surfaces to detect trace pollutants or disinfectant residues. As such, scalable graphene-based sensor arrays for the detection of toxins in running water streams have been reported, along with an emphasis on robust fabrication suitable for real-world deployment purposes (Maity et al., 2023). The same could be extended to RAS by employing flow-through cells measuring flow rates while enabling graphene-based detection of core water-quality.

Nanomaterial-based pressure sensors provide alternatives to rigid and diaphragm-based counterparts. A textile-based pressure sensor made from multilayered graphene coated on polyester has been reported (Lou et al., 2017). This could operate over a broad range up to ~800 kPa while maintaining sub-kilopascal sensitivity. Laser-scribed graphene foams and films also show high sensitivity across wide pressure ranges (Gao et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2015). When wrapped around filter housings or attached to structural pipe sections, these devices could detect early pressure increases linked to fouling or scaling.

MXenes extend pressure and strain sensing by combining physical properties, such as metal-like conductivity along with hydrophilic surfaces. Polymer-MXene and MXene-nanocarbon composites show large signal changes under small loads as well as fast response and often stable cycling (Yang et al., 2022; Qin et al., 2024). When printed as conformal coatings on curved components, they could turn filter lids, pipe elbows, or pump casings into active sensing surfaces. This could help localize early signs of fouling or cavitation.

Nanomaterials also support structural health monitoring of aquaculture infrastructure. MXene-based strain sensors can be embedded into composite laminates, beams, and shells (Yao et al., 2025; Khadem et al., 2025). Self-sensing polymer composites containing carbon nanotubes, graphene, or related fillers can convert mechanical strain into measurable electrical changes, thereby enabling distributed monitoring along structural elements (Tao et al., 2025). Graphene-based strain and vibration sensors can also be applied as thin conformal layers. Laser-patterned graphene devices offer a wide dynamic range and can provide stable signal, supporting their potential deployment on critical joints, flanges or brackets in pump skids and tank stands (Miao et al., 2019; Kaidarova et al., 2020).

4 TENG-based self-powered sensing for hydrodynamics and infrastructure monitoring

Hydrodynamic and oceanographic sensing around mariculture cages has traditionally relied on bulky, often cabled instruments that face power limits, biofouling, mechanical stress, and restricted spatial coverage. TENG-based systems help address these constraints by converting mechanical motion into both sensing signals and local energy supply (Dip et al., 2023). This is particularly valuable at offshore sites where access is difficult and where wiring adds drag, complexity, and additional failure points.

4.1 Monitoring wave dynamics around cages

A major development in wave sensing is the triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG). TENGs use nano- and microstructured polymer and electrode surfaces to convert mechanical motion into electrical signals and usable power. A self-powered triboelectric ocean-wave spectrum sensor (TOSS) uses a tubular TENG housed in a hollow-ball buoy. It measures wave height and frequency from multi-directional motion while generating its own power, reducing reliance on external batteries or cables (Zhang et al., 2020). Coral-like and stackable TENG wave sensors use this concept through modular and biomimetic designs supporting larger arrays. This can improve their performance in more complex wave conditions. Nanostructured triboelectric interfaces increase surface charge density and strengthen the electrical output. This feature can improve sensitivity to tiny variations in wave intensity that help define safe operating limits and calibrate hydrodynamic models near farms (Wang et al., 2022a, b). Disk-type TENG buoys and stackable TENG modules also show that the harvested wave energy can power sensors to monitor salinity, temperature, and other basic parameters (e.g., pH), alongside motion sensing. These designs create compact, self-powered sensor units and could support sustained, high-density wave surveillance around marine aquaculture sites (Jung et al., 2024, 2025).

4.2 Hydrodynamic current sensing around aquaculture cages

The triboelectric approach has also been extended to act as current sensors. TENG-based current meters make use of the fluid motion around a rotor or vibrating element, which can generate electrical signals reporting flow speed and variability. A self-powered, speed-adjustable TENG-based ocean-current sensor has been developed for abyssal operation, where battery replacement is nearly impossible (Pan et al., 2024). Tailored triboelectric films and flexible electrodes can further improve sensitivity to changes in current speed while harvesting energy from the flow.

In marine aquaculture, current meters could be deployed around and beneath cages to provide continuous information on the strength and direction of flow without extensive power lines (Zhang et al., 2023a). This would support cage-deformation analysis, waste-plume dispersion modelling, and feed-plume tracking. At present, many farms rely on a small number of fixed-site Doppler Current Profilers/sensors or rotor current meters, which require external power for signal transduction. In contrast, networks of smaller, self-powered nodes could deliver denser and more resilient coverage, including at the relatively low current velocities typical of farm sites.

4.3 Flow and water level sensing in RAS using TENG technology

In RAS, maintaining spatially distributed flow measurements accurately across multiple loops and side streams remains a core challenge. Conventional approaches can require extensive wiring and multiple power supplies, which creates complex and costly infrastructure that is difficult to maintain and prone to failure. TENGs based on nano-microstructured polymers allow flow to serve as both energy source and a sensing signal (Choi et al., 2023). In single-electrode and tubular TENG flow sensors, the inner wall of a pipe is lined or coated with nanostructured triboelectric materials such as PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) or related fluoropolymers. As water moves through the pipe, contact electrification generates voltage or current pulses whose amplitude and/or frequency correlate with flow rate. Micro- and nanoscale interface engineering can increase surface charge density, while surface texturing, hydrophobic coatings, and layered dielectrics help improve signal stability (Tang et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2022). Hybrid triboelectric–electromagnetic devices can extend the measurable range in large pipelines. The triboelectric component supports sensitivity at low flow speeds, while the electromagnetic unit broadens the upper range. Both elements can be powered by the motion of the fluid.

Level sensing in tanks and sumps can also benefit from self-powered approaches. In a liquid-solid tubular TENG, a PTFE tube with distributed copper electrodes converts water-column motion into position-dependent electrical signals. Bubble-driven variants offer a similar route to self-powered level detection (Li et al., 2022). Some TENG architectures integrate energy harvesting and level sensing in the same structures and can maintain measurable output across a wide range of immersion conditions (Cui et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). When mounted inside wells, these sensors can continue generating level signals during brief power outages.

4.4 Cross-system integration between offshore and land-based platforms

Across cages and RAS infrastructure, TENG-based devices enable sensing that can be partially powered by the same physical processes that are being measured. This can overcome some shortcomings in reliance on cables and frequent battery replacement. When combined with conformal 2D sensing layers and durability-focused nanocoatings, these systems can enable denser and more resilient monitoring networks for both hydrodynamic and infrastructure conditions.

5 Conclusion and discussion

This review describes how nanomaterial-based platforms can shape hydrodynamic and infrastructure sensing in marine aquaculture. Offshore cages and expanding RAS facilities require more stable and continuous data streams compared with conventionally obtained single-point and cable-dependent instruments. Power requirements, biofouling, corrosion, and mechanical stress limit spatial coverage and long-term reliability of these sensors. These constraints are practical problems to be overcome for safer offshore operations, finer cage-depth control, and more resilient hydraulic management in RAS.

We limit our focus to three technological innovations that are promising for various applications in marine aquaculture. First, nanostructured coatings and nanomaterial-functionalized optical-fiber platforms address the gaps in durability and distributed measurement. They can reduce surface degradation and biofouling-driven drift. In addition, they support long and multiplexed sensing lines around the cages and within tanks and sumps. This can improve the real-world application scenario of monitoring by extending their operational lifetime and robustness in deployment.

Second, 2D materials, such as graphene, MXenes, and laser-induced graphene provide conformal pressure and strain platforms that can follow infrastructure geometry. These materials can enable sensing for cage rings, moorings, pipes, and structural units. This shifts the measurement from isolated point sensor housings toward structure-integrated maps of load, deformation, and pressure.

Third, TENG-based systems address the energy issues by converting low-frequency hydrodynamic or hydraulic motion into both sensing signals and power. This is especially valuable where structural cables add drag and failure points, or where battery replacement is impractical.

The broader implication could be a paradigm shift in sensor technology in marine aquaculture. It can turn the various infrastructure used in marine aquaculture, such as cages, moorings, pipes, tanks, and collars into distributed, partially self-powered sensing environments. In offshore farms, this approach can link hydrodynamic forces to structural responses and enable earlier detection of drag buildup and deformation. In RAS, it can support spatially resolved flow, pressure, and level monitoring. These can reveal early fouling, flow maldistribution, and pump degradation before the onset of water-quality or mechanical failures that spread through the system.

Despite such promises, several gaps remain to be addressed upon. Long-term field validation under realistic biofouling and mechanical cycling is still the critical test for both optical-fiber platforms and 2D sensors. Coating adhesion and calibration stability under immersion will determine whether these distributed surfaces can outperform conventional point instruments over months. For TENG-based architectures, the key questions involve reliable output performance under variable conditions. These include conditions such as variable waves, robust encapsulation, and stable integration with low-power devices. Performance reporting should prioritize operational metrics that matter in practice; including drift, lifetime, fouling resistance, and maintenance burden, as well as sensitivity.

Overall, the near-term route to large-scale farm adoption should be co-integration of different aspects. Nanocoatings can protect and stabilize both optical fibers and the surfaces of 2D materials. 2D sensing layers can provide spatially rich datasets. TENG architectures can reduce dependence on power cables and frequent battery replacement for distributed nodes. If treated as a coordinated material system, these can serve as multifunctional platforms, offering coherent frameworks for advancing practical hydrodynamic and infrastructure sensing in marine aquaculture.

Statements

Author contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Writing – review & editing. SD: Writing – review & editing. FN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abrahamsen H. I. Johannesen T. T. Patursson Ø. Norði G. Simonsen K. (2025). Wave-generated currents threaten aquaculture sites. Ocean Eng.334, 121574. doi: 10.1016/J.OCEANENG.2025.121574

2

Cheng T. Shao J. Wang Z. L. (2023). Triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers3, 39. doi: 10.1038/s43586-023-00220-3

3

Chi X. Wang X. Ke X. (2022). Optical fiber–based continuous liquid level sensor based on Rayleigh backscattering. Micromachines13, 633. doi: 10.3390/MI13040633

4

Choi D. Lee Y. Lin Z. H. Cho S. Kim M. Ao C. K. et al . (2023). Recent advances in triboelectric nanogenerators: from technological progress to commercial applications. ACS Nano17, 11087–11219. doi: 10.1021/ACSNANO.2C12458/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN2C12458_0047.JPEG

5

Corredor J. E. (2018). “ Environmental constraints to instrumental ocean observing: power sources, hydrostatic pressure, metal corrosion, biofouling, and mechanical abrasion,” in Coastal Ocean Observing ( Springer, Cham), 85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78352-9_4

6

Cui X. Yu C. Wang Z. Wan D. Zhang H. (2022). Triboelectric nanogenerators for harvesting diverse water kinetic energy. Micromachines13, 1219. doi: 10.3390/MI13081219

7

Delgado A. Briciu-Burghina C. Regan F. (2021). Antifouling strategies for sensors used in water monitoring: review and future perspectives. Sensors21, 389. doi: 10.3390/S21020389

8

Deshmukh S. Ghosh K. Pykal M. Otyepka M. Pumera M. (2023). Laser-induced MXene-functionalized graphene nanoarchitectonics-based microsupercapacitor for health monitoring application. ACS Nano17, 20537–20550. doi: 10.1021/ACSNANO.3C07319/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN3C07319_0008.JPEG

9

Dip T. M. Arin Md R. A. Anik H. R. Uddin Md M. Tushar S. I. Sayam A. et al . (2023). Triboelectric nanogenerators for marine applications: recent advances in energy harvesting, monitoring, and self-powered equipment. Advanced Materials Technol.8, 2300802. doi: 10.1002/ADMT.202300802

10

Fajardo C. Martinez-Rodriguez G. Blasco J. Mancera J. M. Thomas B. De Donato M. (2022). Nanotechnology in aquaculture: applications, perspectives and regulatory challenges. Aquaculture Fisheries7, 185–200. doi: 10.1016/J.AAF.2021.12.006

11

Fan F. R. Tang W. Wang Z. L. (2016). Flexible nanogenerators for energy harvesting and self-powered electronics. Advanced Materials28, 4283–4305. doi: 10.1002/ADMA.201504299

12

Fan W. Li C. Li W. Yang J. (2022). 3D waterproof MXene-based textile electronics for physiology and motion signals monitoring. Advanced Materials Interfaces9, 2102553. doi: 10.1002/ADMI.202102553

13

Gao J. Chen X. Afsarimanesh N. Chakraborthy A. Roy T. Maulik G. et al . (2025). Printed graphene sensors for pressure-sensing applications: progress and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Analytical Chem.193, 118470. doi: 10.1016/J.TRAC.2025.118470

14

Golden C. D. Koehn J.Z. Shepon A. Passarelli S. Free C. M. Viana D. F. et al . (2021). Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature598, 315–320. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03917-1

15

Grabowski K. Srivatsa S. Vashisth A. Mishnaevsky L. Uhl T. (2022). Recent advances in MXene-based sensors for structural health monitoring applications: A review. Measurement189, 110575. doi: 10.1016/J.MEASUREMENT.2021.110575

16

Guo Y. Zeng S. Liu Q. Sun J. Zhu M. Li L. et al . (2024). Review of the pressure sensor based on graphene and its derivatives. Microelectronic Eng.288, 112167. doi: 10.1016/J.MEE.2024.112167

17

Hamdhani H. Eppehimer D. E. Bogan M. T. (2020). Release of treated effluent into streams: A global review of ecological impacts with a consideration of its potential use for environmental flows. Freshw. Biol.65, 1657–1670. doi: 10.1111/FWB.13519

18

Heasman K. G. Scott N. Sclodnick T. Chambers M. Costa-Pierce B. Dewhurst T. et al . (2024). Variations of aquaculture structures, operations, and maintenance with increasing ocean energy. Front. Aquaculture3. doi: 10.3389/FAQUC.2024.1444186/BIBTEX

19

Hopkins G. Davidson I. Georgiades E. Floerl O. Morrisey D. Cahill P. (2021). Managing biofouling on submerged static artificial structures in the marine environment – assessment of current and emerging approaches. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2021.759194/XML

20

Huang K. Li Z. Lin J. Han G. Huang P. (2018). Two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev.47, 5109–5124. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00838D

21

Ielo I. Giacobello F. Sfameni S. Rando G. Galletta M. Trovato V. et al . (2021). Nanostructured surface finishing and coatings: functional properties and applications. Materials14, 2733. doi: 10.3390/MA14112733

22

Jaffari Z. H. Abuabdou S. M. A. Ng D. Q. Bashir M. J. K. (2021). Insight into two-dimensional MXenes for environmental applications: recent progress, challenges, and prospects. FlatChem28, 100256. doi: 10.1016/J.FLATC.2021.100256

23

Jauregui-Vazquez D. Gutierrez-Rivera M. E. Garcia-Mina D. F. Sierra-Hernandez J. M. Gallegos-Arellano E. Estudillo-Ayala J. M. et al . (2021). Low-pressure and liquid level fiber‐optic sensor based on polymeric fabry–perot cavity. Optical Quantum Electron.53, 237. doi: 10.1007/S11082-021-02871-6/TABLES/3

24

Jiang D. Xu M. Dong M. Guo F. Liu X. Chen G. et al . (2019). Water-solid triboelectric nanogenerators: an alternative means for harvesting hydropower. Renewable Sustain. Energy Rev.115, 109366. doi: 10.1016/J.RSER.2019.109366

25

Jung H. Lu Z. Hwang W. Friedman B. Copping A. Branch R. et al . (2025). Modeling and sea trial of a self-powered ocean buoy harvesting arctic ocean wave energy using a double-side cylindrical triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy135, 110641. doi: 10.1016/J.NANOEN.2024.110641

26

Jung H. Martinez J. Ouro-Koura H. Salalila A. Garza A. Hall A. et al . (2024). Self-powered ocean buoy using a disk-type triboelectric nanogenerator with a mechanical frequency regulator. Nano Energy121, 109216. doi: 10.1016/J.NANOEN.2023.109216

27

Kaidarova A. Alsharif N. Oliveira B. M.N. Marengo M. Geraldi N. R. Duarte C. M. et al . (2020). Laser-printed, flexible graphene pressure sensors. Global Challenges4, 2000001. doi: 10.1002/GCH2.202000001

28

Katsidoniotaki E. Su B. Kelasidi E. Sapsis T. P. (2025). Multifidelity digital twin for real-time monitoring of structural dynamics in aquaculture net cages. Sci. Rep.15, 44281. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-27812-1

29

Kennish M. J. (2002). Environmental threats and environmental future of estuaries. Environ. Conserv.29, 78–107. doi: 10.1017/S0376892902000061

30

Khadem A. H. Anik H. R. Limon Md G. M. Rabbani M. Rafi A. S. Mim I. K. et al . (2025). Review of MXene-based electrospun nanocomposites for flexible and wearable sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Materials8, 16231–16259. doi: 10.1021/ACSANM.5C02646/SUPPL_FILE/AN5C02646_SI_001.ZIP

31

Khalid M. Y. Umer R. Zweiri Y. H. Kim J. K. (2025). Rise of graphene in novel piezoresistive sensing applications: A review on recent development and prospect. Materials Sci. Engineering: R: Rep.163, 100891. doi: 10.1016/J.MSER.2024.100891

32

Kong M. Yang M. Li R. Long Y. Z. Zhang J. Huang X. et al . (2023). Graphene-based flexible wearable sensors: mechanisms, challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Advanced Manufacturing Technol.131, 3205–3237. doi: 10.1007/S00170-023-12007-7

33

Lai Q. T. Zhao X. H. Sun Q. J. Tang Z. Tang X. G. Roy V. A. L. (2023). Emerging MXene-based flexible tactile sensors for health monitoring and haptic perception. Small19, 2300283. doi: 10.1002/SMLL.202300283

34

Li C. Liu X. Yang D. Liu Z. (2022). Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a moving bubble in liquid for mechanical energy harvesting and water level monitoring. Nano Energy95, 106998. doi: 10.1016/J.NANOEN.2022.106998

35

Li M. Singh R. Wang Y. Marques C. Zhang B. Kumar S. (2022). Advances in novel nanomaterial-based optical fiber biosensors—A review. Biosensors12, 843. doi: 10.3390/BIOS12100843

36

Liang H. Shi X. Li Y. (2024). Technologies in marine antifouling and anti-corrosion coatings: A comprehensive review. Coatings14, 1487. doi: 10.3390/COATINGS14121487

37

Lopez J. D. Keley M. Dante A. Werneck M. M. (2021). Optical fiber sensor coated with copper and iron oxide nanoparticles for hydrogen sulfide sensing. Optical Fiber Technol.67, 102731. doi: 10.1016/J.YOFTE.2021.102731

38

Lou C. Wang S. Liang T. Pang C. Huang L. Run M. et al . (2017). A graphene-based flexible pressure sensor with applications to plantar pressure measurement and gait analysis. Materials10, 1068. doi: 10.3390/MA10091068

39

Lu Y. Qu X. Zhao W. Ren Y. Si W. Wang W. et al . (2020). Highly stretchable, elastic, and sensitive MXene-based hydrogel for flexible strain and pressure sensors. Research2020. doi: 10.34133/2020/2038560

40

Maity A. Pu H. Sui X. Chang J. Bottum K. J. Jin B. et al . (2023). Scalable graphene sensor array for real-time toxins monitoring in flowing water. Nat. Commun.14, 4184. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39701-0

41

Mi S. Avital E. J. Williams J. J. R. Chatjigeorgiou I. K. (2025). A fluid–structure interaction (FSI) solver for evaluating the impact of circular fish swimming patterns on offshore aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric.237, 110625. doi: 10.1016/J.COMPAG.2025.110625

42

Miao P. Wang J. Zhang C. Sun M. Cheng S. Liu H. (2019). Graphene nanostructure-based tactile sensors for electronic skin applications. Nano-Micro Lett.11, 71. doi: 10.1007/S40820-019-0302-0

43

Oliveira A. Resende C. Pereira A. Madureira P. Gonçalves J. Moutinho R. et al . (2020). IoT sensing platform as a driver for digital farming in rural Africa. Sensors20, 3511. doi: 10.3390/S20123511

44

Pan Y. C. Dai Z. Ma H. Zheng J. Leng J. Xie C. et al . (2024). Self-powered and speed-adjustable sensor for abyssal ocean current measurements based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun.15, 6133. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50581-w

45

Parra L. Lloret G. Lloret J. Rodilla M. (2018). Physical sensors for precision aquaculture: A review. IEEE Sensors J.18, 3915–3923. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2018.2817158

46

Pereiro D. Belyaev O. Dunbar M. B. Conway A. Dabrowski T. Graves I. et al . (2023). An observational and warning system for the aquaculture sector. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2023.1288610/BIBTEX

47

Qin R. Nong J. Wang K. Liu Y. Zhou S. Hu M. et al . (2024). Recent advances in flexible pressure sensors based on MXene materials. Advanced Materials36, 2312761. doi: 10.1002/ADMA.202312761

48

Radhakrishnan S. Jelmy S. J. E.J. Saji K. J. Sanathanakrishnan T. John H. (2022). Triboelectric nanogenerators for marine energy harvesting and sensing applications. Results Eng.15, 100487. doi: 10.1016/J.RINENG.2022.100487

49

Sahoo B. N. Thomas P. J. Thomas P. Greve M. M. (2025). Antibiofouling coatings for marine sensors: progress and perspectives on materials, methods, impacts, and field trial studies. ACS Sensors10, 1600–1619. doi: 10.1021/ACSSENSORS.4C02670/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/SE4C02670_0015.JPEG

50

Sharjeel M. Ali S. Summer M. Noor S. Nazakat L. (2024). Recent advancements of nanotechnology in fish aquaculture: an updated mechanistic insight from disease management, growth to toxicity. Aquaculture Int.32, 6449–6486. doi: 10.1007/S10499-024-01473-9

51

Sievers M. Korsøen Ø. Warren-Myers F. Oppedal F. Macaulay G. Folkedal O. et al . (2022). Submerged cage aquaculture of marine fish: A review of the biological challenges and opportunities. Rev. Aquaculture14, 106–119. doi: 10.1111/RAQ.12587

52

Silvanir W. H. F. Chia W. Y. Ende S. Chia S. R. Chew K. W. (2024). Nanomaterials in aquaculture disinfection, water quality monitoring and wastewater remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.12, 113947. doi: 10.1016/J.JECE.2024.113947

53

Somers K. M. Kilgour B. W. Munkittrick K. R. Arciszewski T. J. (2018). An adaptive environmental effects monitoring framework for assessing the influences of liquid effluents on benthos, water, and sediments in aquatic receiving environments. Integrated Environ. Assess. Manage.14, 552–566. doi: 10.1002/IEAM.4060

54

Su B. Bjørnson F. O. Tsarau A. Endresen P. C. Ohrem S. J. Føre M. et al . (2023). Towards a holistic digital twin solution for real-time monitoring of aquaculture net cage systems. Mar. Structures91, 103469. doi: 10.1016/J.MARSTRUC.2023.103469

55

Sun W. Li W. Xue C. Zhang W. Jiang Y. (2025). MXene-silk composites integrated on laser-induced graphene platform for touch-free sensing. Chem. Eng. J.509, 161317. doi: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2025.161317

56

Tacon A. G. J. Metian M. Parsons G.J. Shumway S. E. (2025). A global aquaculture and aquafeed production update: 2010 to 2023. Rev. Fisheries Sci. Aquaculture. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2025.2568830

57

Tang N. Zheng Y. Yuan M. Jin K. Haick H. (2021). High-performance polyimide-based water-solid triboelectric nanogenerator for hydropower harvesting. ACS Appl. Materials Interfaces13, 32106–32114. doi: 10.1021/ACSAMI.1C06330/SUPPL_FILE/AM1C06330_SI_003.AVI

58

Tao Y. Zhang R. Hu X. Ou Y. Ren M. Sun J. et al . (2025). A comprehensive review on fiber-based self-sensing polymer composites for in situ structural health monitoring. Advanced Composites Hybrid Materials8, 339. doi: 10.1007/S42114-025-01413-Y

59

Tian H. Shu Y. Wang X. F. Mohammad M. A. Bie Z. Xie Q. Y. et al . (2015). A graphene-based resistive pressure sensor with record-high sensitivity in a wide pressure range. Sci. Rep.5, 8603. doi: 10.1038/srep08603

60

Urrutia A. Goicoechea J. Arregui F. J. (2015). Optical fiber sensors based on nanoparticle-embedded coatings. J. Sensors2015, 805053. doi: 10.1155/2015/805053

61

Verma D. K. Monika Barad R. R. Satyaveer Chandra I. Maurya N. K. et al . (2024). “ Digitalization as innovative development in aquaculture and fisheries as future importance,” in Futuristic Trends in Agriculture Engineering & Food Sciences, Book 15 ( Iterative International Publisher, Selfypage Developers Pvt Ltd), 3, 689–708. doi: 10.58532/V3BCAG15P6CH1

62

Volkenburg T. V. Ayoub D. Reyes A. A. Xia Z. Hamilton L. (2023). Practical considerations for laser-induced graphene pressure sensors used in marine applications. Sensors23, 9044. doi: 10.3390/S23229044/S1

63

Wang P. He B. Wang B. Liu S. Ye Q. Zhou F. et al . (2023). MXene/metal–organic framework based composite coating with photothermal self-healing performances for antifouling application. Chem. Eng. J.474, 145835. doi: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2023.145835

64

Wang X. Liu J. Wang S. Zheng J. Guan T. Liu X. et al . (2022). A self-powered triboelectric coral-like sensor integrated buoy for irregular and ultra-low frequency ocean wave monitoring. Advanced Materials Technol.7, 2101098. doi: 10.1002/ADMT.202101098

65

Wang C. M. Ma M. Chu Y. Jeng D. S. Zhang H. (2024). Developments in modeling techniques for reliability design of aquaculture cages: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.12, 103. doi: 10.3390/JMSE12010103

66

Wang H. Magesan G. N. Bolan N. S. (2004). An overview of the environmental effects of land application of farm effluents. New Z. J. Agric. Res.47, 389–403. doi: 10.1080/00288233.2004.9513608

67

Wang L. Wang Y. j. Song S. Li F. (2021). Overview of fibre optic sensing technology in the field of physical ocean observation. Front. Phys.9. doi: 10.3389/FPHY.2021.745487/BIBTEX

68

Wang H. Zhao Z. Liu P. Guo X. (2022a). Laser-induced graphene based flexible electronic devices. Biosensors12, 55. doi: 10.3390/BIOS12020055

69

Wang H. Zhu C. Wang W. Xu R. Chen P. Du T. et al . (2022b). A stackable triboelectric nanogenerator for wave-driven marine buoys. Nanomaterials12, 594. doi: 10.3390/NANO12040594/S1

70

Xia K. Xu Z. Hong Y. Wang L. (2023). A free-floating structure triboelectric nanogenerator based on natural wool ball for offshore wind turbine environmental monitoring. Materials Today Sustainability24, 100467. doi: 10.1016/J.MTSUST.2023.100467

71

Xu L. Tang Y. Zhang C. Liu F. Chen J. Xuan W. et al . (2022). Fully self-powered instantaneous wireless liquid level sensor system based on triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Res.15, 5425–5434. doi: 10.1007/S12274-022-4125-9/METRICS

72

Yang N. Liu H. Yin X. Wang F. Yan X. Zhang X. et al . (2022). Flexible pressure sensor decorated with MXene and reduced graphene oxide composites for motion detection, information transmission, and pressure sensing performance. ACS Appl. Materials Interfaces14, 45978–45987. doi: 10.1021/ACSAMI.2C16028/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AM2C16028_0008.JPEG

73

Yao Y. Li X. Sisican K. M. Ramos R. M. C. Judicpa M. Qin S. et al . (2025). Progress towards efficient MXene sensors. Commun. Materials6, 210. doi: 10.1038/s43246-025-00907-y

74

Zhang C. Hao Y. Yang J. Su W. Zhang H. Wang J. et al . (2023a). Recent advances in triboelectric nanogenerators for marine exploitation. Advanced Energy Materials13, 2300387. doi: 10.1002/AENM.202300387

75

Zhang Q. Liu X. Jiang Y. Xiao F. Wang W. Duan J. (2025). Graphene research progress in the application of anticorrosion and antifouling coatings. Crystals15, 541. doi: 10.3390/CRYST15060541

76

Zhang C. Liu L. Zhou L. Yin X. Wei X. Hu Y. et al . (2020). Self-powered sensor for quantifying ocean surface water waves based on triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano14, 7092–7100. doi: 10.1021/ACSNANO.0C01827/ASSET/IMAGES/MEDIUM/NN0C01827_M011.GIF

77

Zhang Z. Zhu H. Zhang W. Zhang Z. Lu J. Xu K. et al . (2023b). A review of laser-induced graphene: from experimental and theoretical fabrication processes to emerging applications. Carbon214, 118356. doi: 10.1016/J.CARBON.2023.118356

Summary

Keywords

aquaculture, blue economy, graphene, MXenes, nanomaterial, recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs)

Citation

Sahoo SR, Liao Z-H, Das SP and Nan F-H (2026) Nanomaterial-enabled hydrodynamic and infrastructure monitoring in marine aquaculture. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1763089. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1763089

Received

08 December 2025

Revised

24 December 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Pranaya Kumar Parida, Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR), India

Reviewed by

Soumya Prasad Panda, Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR), India

Sibiya Ashokkumar, Alagappa University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Sahoo, Liao, Das and Nan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fan-Hua Nan, fhnan@mail.ntou.edu.tw

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.