Abstract

Shark populations worldwide are declining rapidly, primarily due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and mislabeling of seafood products, which exacerbates their exploitation and conservation challenges. This study investigates the presence of shark meat being sold under false labels as fish species in Ecuadorian markets, spanning both coastal and highland regions. Using primers derived from the nuclear ribosomal ITS2 region for molecular identification, 97 samples sold as fish meat in Ecuadorian markets were analyzed for the presence or absence of shark DNA. The results revealed that 47.42% of the samples corresponded to shark meat. These samples came from cities in the highlands (Ambato, Cuenca, Ibarra and Quito). No shark meat was identified in the samples from coastal cities (Guayaquil and Manta). Four shark species were identified: Alopias pelagicus (Endangered), Carcharhinus falciformis (Vulnerable), Sphyrna zygaena (Vulnerable), and Prionace glauca (Near Threatened). These findings highlight the ongoing sale of threatened shark species under misleading labels in the highlands region of Ecuador, posing significant risks to marine biodiversity and consumer rights. The study underscores the need for robust traceability systems, routine monitoring, and public education to combat seafood fraud and support shark conservation efforts.

Highlights

-

Nearly half (47.42%) of the fish samples from Ecuadorian markets were actually shark meat, mislabeled and sold without accurate identification.

-

DNA analysis using primers derived from the nuclear ribosomal ITS2 region identified four shark species: Alopias pelagicus (Endangered), Carcharhinus falciformis and Sphyrna zygaena (both Vulnerable), and Prionace glauca (Near Threatened), being sold under false labels, highlighting serious conservation concerns.

-

While highland cities like Quito and Cuenca had mislabeled shark products, no shark meat was found in samples from coastal cities such as Guayaquil and Manta, suggesting region-specific patterns in seafood mislabeling.

-

This study underscores the urgent need for stronger marine policy in Ecuador, recommending the implementation of a seafood traceability system, routine market monitoring using genetic tools, and public education campaigns.

1 Introduction

Sharks play a vital role in aquatic ecosystems as apex predators and mesopredators, regulating prey populations and maintaining species diversity (Dulvy et al., 2014; Motivarash et al., 2020; Dedman et al., 2024). As keystone species, they help stabilize food chains and support overall ecosystem health (Motivarash et al., 2020). Sharks influence a variety of habitats, including coral reefs and seagrass communities, through top-down regulation and nutrient transport (Roff et al., 2016; Dedman et al., 2024). However, despite their ecological importance, shark populations are in decline due to overfishing and human activities (Motivarash et al., 2020; Dedman et al., 2024). These declines disrupt ecosystem functions and alter food web dynamics (Roff et al., 2016).

Recent estimates by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species indicate that 32.6% (391 of 1,199) of assessed elasmobranch species are threatened with extinction. However, because many elasmobranch species are listed as Data Deficient, the true proportion of threatened species is likely underestimated. When Data Deficient species are taken into account, the proportion of threatened elasmobranchs may increase to approximately 37.5% (Dulvy et al., 2021; Constance et al., 2023). The global abundance of sharks and rays has declined by 71% since 1970, posing severe risks to marine biodiversity and ecosystem stability (Pacoureau et al., 2023). Overfishing and habitat degradation have profoundly altered populations of marine animals, particularly sharks and rays (elasmobranchs). In marine ecosystems, extinction risk has increased markedly over the past century with human population growth, the expansion of industrial fishing, and rapid coastal development. Overfishing defined as the excessive removal of fish from the ocean at rates that exceed the species’ capacity to replenish their populations—has emerged as a primary threat to marine biodiversity worldwide (Constance et al., 2023). Loss and degradation of habitat, climate change and pollution are also important threats for sharks and rays (Dulvy et al., 2021).

Conservation and sustainable fisheries management rely on global indicators, such as the shark and ray Red List Index (RLI), to track progress toward biodiversity targets and Sustainable Development Goals (Jacquet et al., 2008). While the IUCN RLI monitors extinction risk across species, indicators for sustainable fisheries are based on limited stock assessments, largely focused on coastal teleosts and market tunas from data-rich regions. This bias leaves small-scale and non-target fisheries, including those involving sharks and rays, underrepresented, underscoring the need for a global RLI that integrates exploited aquatic biodiversity and its ecological implications (Jacquet et al., 2008).

This global gap in monitoring exploited aquatic biodiversity is also evident at the national level. Shark populations in Ecuador are also impacted by overfishing and illegal trade. More than 40 shark species are found in Ecuadorian waters, most of which are listed on the IUCN Red List (Jacquet et al., 2008). The capture of several shark species is forbidden, including the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus), smooth hammerhead shark (Sphyrna zygaena), scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini), bonnethead shark (Sphyrna tiburo), great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran), oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), and silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) (Gobierno de la República del Ecuador, 2008; Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, 2020; Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, 2022). For other shark species, Ecuador does not recognize a directed shark fishery. Nonetheless, a legal loophole allowing the sale of sharks caught as bycatch has led to the legal landing of more than 250,000 individuals annually, likely comprising multiple species (Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018), mainly for their fins, which are sold at high prices in Asian markets (Gobierno de la República del Ecuador, 2008; Mateo Calderón, 2014).

Mislabeling of seafood products, which involves the substitution of one species for another, is a major problem in Ecuador, where shark meat is frequently marketed under the names of commonly traded fish species (Oceana; Mateo Calderón, 2014; Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). This practice threatens marine conservation by facilitating the overexploitation of vulnerable shark populations, many of which are CITES-protected or threatened, and disrupts marine ecosystems (Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). This issue undermines consumer confidence and highlights the urgent need for stricter enforcement and transparent labeling of seafood products so that consumers know with certainty what they are buying and to safeguard marine biodiversity (Oceana; Mateo Calderón, 2014; Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022).

Molecular tools have become central to shark conservation and trade monitoring, especially when morphological identification is difficult. In this study, we employed species-specific PCR targeting mitochondrial markers (Internally Transcribed Spacer – ITS2), an approach that has been widely validated for accurate identification of shark species in market samples. Species-specific PCR offers a cost-effective, sensitive, and practical method for routine monitoring (Pank et al., 2001; Shivji et al., 2002; Abercrombie et al., 2005; Pinhal et al., 2012). While additional methods such as ddPCR, LAMP, eDNA analysis, and nanopore sequencing have expanded the molecular toolkit for wildlife monitoring, these techniques fall outside the scope of the present work and are mentioned here only to highlight ongoing developments in the field (But et al., 2020; Tiktak et al., 2024; Alvarenga et al., 2025).

The widespread mislabeling of shark products highlights the need for accurate species identification and effective monitoring in seafood markets. In this study, we used molecular markers targeting the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) to assess whether shark meat is being sold under false labels in both highland and coastal cities. Although sharks and rays are often discussed together in conservation and trade contexts, the present study specifically focuses on shark meat, which is more prevalent in Ecuadorian fish markets and for which validated genetic tools are available (Palacios et al., 2025). By comparing samples across regions, our objective was to provide an exploratory assessment of mislabeling patterns and to identify which shark species are being traded in local markets, rather than to perform an extensive statistical analysis. These data provide critical insights into the scale of seafood fraud in Ecuador and its implications for consumer rights, fisheries management and shark conservation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

Random sampling was carried out in six highly populated cities located in two regions of Ecuador: Highlands - Ambato, Cuenca, Ibarra and Quito; and Coastal - Guayaquil and Manta. In each city, 3 markets were selected, and an average of 5 samples were obtained per market (Supplementary Table 1). During sampling, researchers requested different types of “corvina”, a term used in Ecuador to refer to white-fish such as Peruvian weakfish (Cynoscion analis) and Brotula (Brotula clarkae), and purchased the least expensive option. A total of 97 fresh, non-frozen fish meat samples were collected between June and September 2023.

This sampling strategy was designed as an exploratory survey to provide an initial descriptive assessment of fish products sold in Ecuadorian markets, rather than to estimate prevalence or support formal statistical comparisons among regions. Markets were selected to capture geographic and socioeconomic diversity within each city; however, sampling was not stratified by market size, sales volume, or vendor type. Accordingly, the study was not intended to support inference beyond descriptive characterization.

Fish products in the surveyed markets were typically sold without formal labeling, species-specific signage, or itemized receipts. In many traditional markets in Ecuador, fish is commonly sold fresh and unpackaged under generic names such as “corvina,” and written documentation of species identity at the point of sale is informal or absent. Sampling and purchase procedures were therefore designed to reflect typical consumer purchasing conditions rather than regulatory labeling compliance.

2.2 DNA extraction and species identification

The extraction of genetic material was performed from 0,12g-0.14g of muscle tissue from each sample, using the protocol by (Abercrombie, 2004). The quantity and quality of the obtained DNA were assessed using the Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific), and its integrity was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genetic analyses were designed to detect shark species only, using primers previously validated for sharks in Ecuador. Identification of ray species was outside the scope of this study (Pank et al., 2001; Abercrombie et al., 2005; Palacios et al., 2025). Shark identification was performed using PCR with two universal shark primers that amplify the ITS2 region: FISH5.8SF and FISH28SR (Abercrombie et al., 2005) (Table 1). When a meat sample belongs to a non-shark species, no amplification occurs with these primers, and therefore no band appears on the gel. Only samples that generated a visible ITS2 band were classified as positive for shark meat, and the size of the amplified fragment allowed further assignment to the corresponding shark family: Carcharhinidae (1470 bp), Sphyrnidae (860 bp), Alopiidae (1200 bp), Lamnidae (1350 bp) (Table 1). The reagent concentrations for the PCR were determined following the protocol outlined by (Pinhal et al., 2012). Each 25 μl PCR reaction contained 20–25 ng/μl of DNA, 1X PCR Buffer (Invitrogen), 12.5 picomoles of each primer, 2.0 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.2 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen), and one unit of Platinum™ Taq DNA Polymerase. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 15 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 65°C for 1 minute, extension at 72°C for 2 minutes, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. After cycling, the samples were kept at 4 °C or -20 °C. These PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1X TBE buffer at 80V for 2 hours.

Table 1

| Universal primers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Primer sequences | Amplicon size (pb) | Reference | |

| Sphyrnidae | Universal Forward Primer FISH5.8SF: 5’TTAGCGGTGGATCACTCGGCTCGT3’ Universal Reverse Primer FISH28SR: 5’TCCTCCGCTTAGTAATATGCTTAA ATTCAGC3’ |

860 | Pank et al. (2001) | |

| Carcharinidae | 1,470 | |||

| Lamnidae | 1,350 | |||

| Alopiidae | 1,200 | |||

| Species specific primers | ||||

| Scientific name | Common name | Specific forward primer sequence* | Amplicon size (pb) | Reference |

| Prionace glauca | Blue | 5’AGAAGTGGAGCGACTGTCTTCGCC3’ | 929 | Shivji et al. (2002) |

| Carcharhinus falciformis | Silky | 5’ ACCGTGTGGGCCAGGGGTC 3’ | 1085 | Shivji et al. (2002) |

| Carcharhinus galapagensis | Galapagos | 5’GTGCCTTCCCACCTTTTGGCG3’ | 480 | Pank et al. (2001) |

| Sphyrna lewini | Scalloped hammerhead |

5’GGTAAAGGATCCGCTTTGCTGGA3’ | 445 | Abercrombie et al. (2005) |

| Sphyrna zygaena | Smooth hammerhead |

5’TGAGTGCTGTGAGGGCACGTGGCCT3’ | 249 | Abercrombie et al. (2005) |

| Sphyrna mokarran | Great hammerhead |

5’AGCAAAGAGCGTGGCTGGGGTTT CGA3’ |

782 | Abercrombie et al. (2005) |

| Alopias superciliosus | Bigeye thresher | 5’AGTGCTTGACCATTCGGTGTGCGT3’ | 1000 | Abercrombie (2004) |

| Alopias vulpinus | Common thresher | 5’TTCCGTCTCCTTCCACACGTCGAGT3’ | 601 | Abercrombie (2004) |

| Alopias pelagicus | Pelagic thresher | 5’CAAGCCTTGCACTTTCGAATGAA GC 3’ |

230 | Abercrombie (2004) |

| Isurus oxyrinchus | Mako | 5’AGGTGCCTGTAGTGCTGGTAGACACA3’ | 771 | Shivji et al. (2002) |

Universal and species-specific primer sequences for sharks.

*Reverse primer used was the universal reverse primer FISH28SR.

For species identification, 10 species-specific primers previously described in the literature were used (Pank et al., 2001; Shivji et al., 2002; Abercrombie, 2004; Abercrombie et al., 2005). These species inhabit Ecuadorian waters and have been found in various fishing and commercialization activities (Jacquet et al., 2008; Briones-Mendoza et al., 2022; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). A separate PCR was performed for each of the Sphyrnidae, Carcharhinidae, and Alopiidae families, utilizing three species-specific primers. This approach enabled accurate identification of each species within its respective family (Table 1). For the Lamnidae family, a PCR was performed using one species-specific primer (Table 1). These PCRs were performed using the same reagent concentrations and conditions as those used for the shark identification PCR. The PCR products were examined using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1X TBE buffer at 100V for 30–45 minutes.

The species-specific PCR primers employed in this study have been previously validated for sensitivity, specificity, and detection limits in shark identification studies only (Pank et al., 2001; Shivji et al., 2002; Abercrombie et al., 2005; Pinhal et al., 2012). These PCR assays were designed to amplify species specific fragments from target species while incorporating positive controls to avoid false negatives. Validation with large datasets of shark reference samples and multiple tissue types showed that the primers consistently amplified only their intended target species, with no cross-reactivity with closely related non-target taxa (Pank et al., 2001; Shivji et al., 2002; Abercrombie et al., 2005; Pinhal et al., 2012). This confirms their high sensitivity and specificity, ensuring reliable identification across a wide range of shark products. Primer specificity was further evaluated by including DNA from taxonomically confirmed non-target teleost fish species (seabass) as negative controls in every PCR assay. These samples, obtained from supermarkets with well-documented and controlled supply chains, consistently showed no amplification, supporting the absence of cross-reactivity with non-shark taxa. No amplification was observed in these controls, confirming that the primers do not cross-react with non-shark fish DNA and that positive results correspond exclusively to shark-derived samples. In all cases, positive control consisted of a previously extracted and analyzed sample of each specific species, as described by (Hidalgo Manosalvas, 2013). For the Sphyrnidae family, we analyzed the species S. zygaena, S. lewini, and S. mokarran. For Carcharhinidae we analyzed P. glauca, C. galapagensis and C. falciformis. For Alopiidae, we analyzed the species A. pelagicus, A. superciliosus and A. vulpinus. Lastly, for Lamnidae we tested for I. oxyrinchus (Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022).

3 Results

3.1 Positive samples from the highlands and coastal region

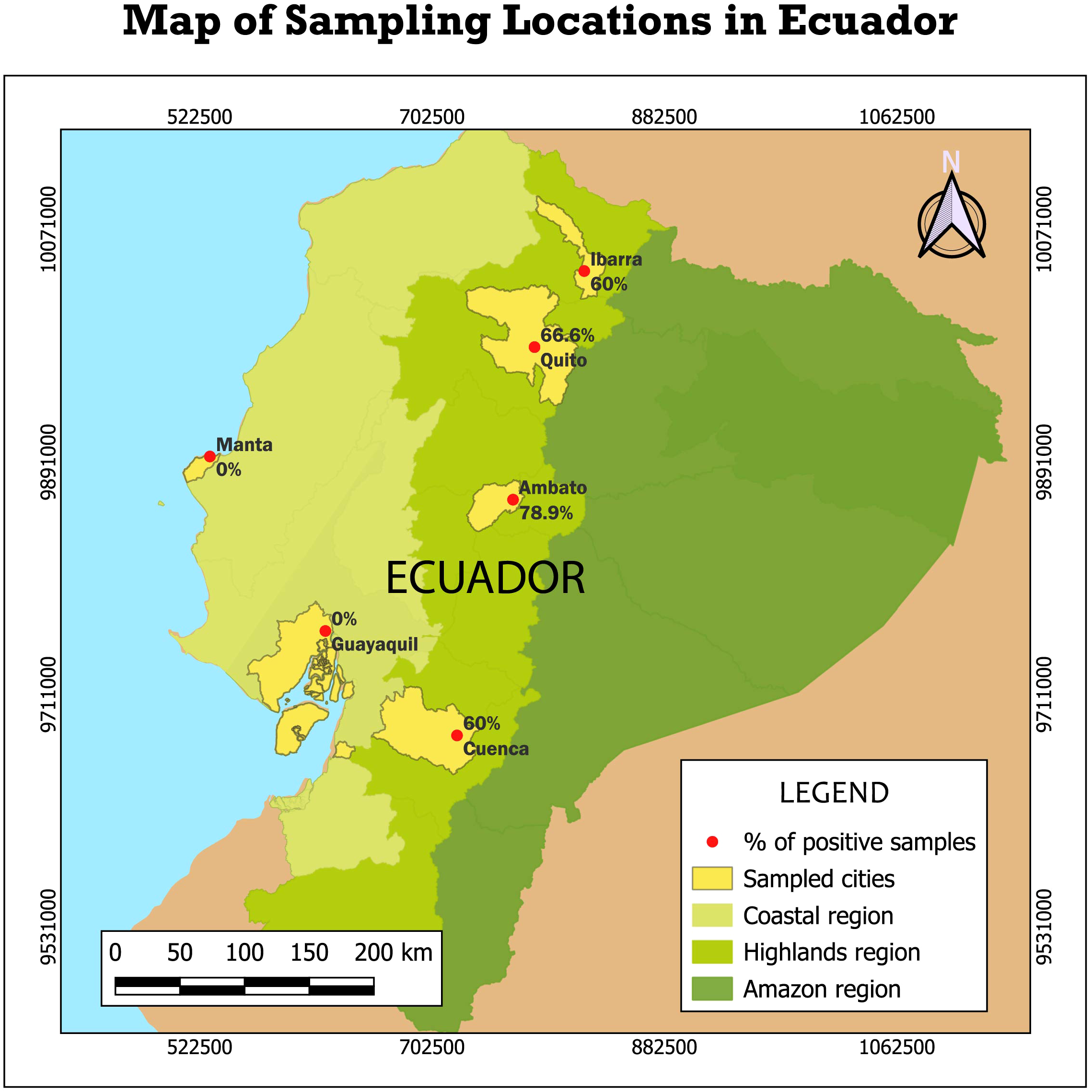

Out of the 97 processed fish meat samples, 46 tested positive for shark meat (47.42%) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure 1). All the positive samples were from Ambato, Cuenca, Ibarra, and Quito, cities in the highlands region. In contrast, 0% of the samples from Guayaquil and Manta (coastal cities) tested positive for shark meat, underscoring the absence of shark meat in coastal markets in our study.

Table 2

| Region | City | Number of samples | Positive samples for shark | Percentage of positive samples | Region - percentage of positive samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highlands | Ambato | 19 | 15 | 78.9% | 66.6% |

| Cuenca | 15 | 9 | 60% | ||

| Ibarra | 20 | 12 | 60% | ||

| Quito | 15 | 10 | 66.6% | ||

| Coastal | Guayaquil | 15 | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| Manta | 13 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Total | 97 | 46 | 47.42% | ||

Results of shark-positive fish meat samples by city and region of Ecuador.

Bold values correspond to total number of samples, total number of positive samples, total percentage of positive samples for both regions, total percentage of positive samples for each region.

Among the 46 samples identified as shark meat, 45 samples (97.8%) were successfully identified to the species level. The remaining sample (2.2%) was identified only to the family taxon level, as Carcharinidae. In the highlands region, the percentage of positive samples in each city were: 66.6% in Quito, 60% in Ibarra, 78.94 in Ambato and 60% in Cuenca (Table 2; Figure 1; Supplementary Figures 2–4).

Figure 1

Percentage of samples identified as shark meat in the coastal and highland regions of Ecuador. Six cities in these two regions were surveyed. The following percentages were identified: Quito, 66.6%; Ambato, 78.9%; Ibarra, 60%; and Cuenca, 60%. No shark meat was found in coastal cities.

3.2 Families and species identification using multiplex PCR

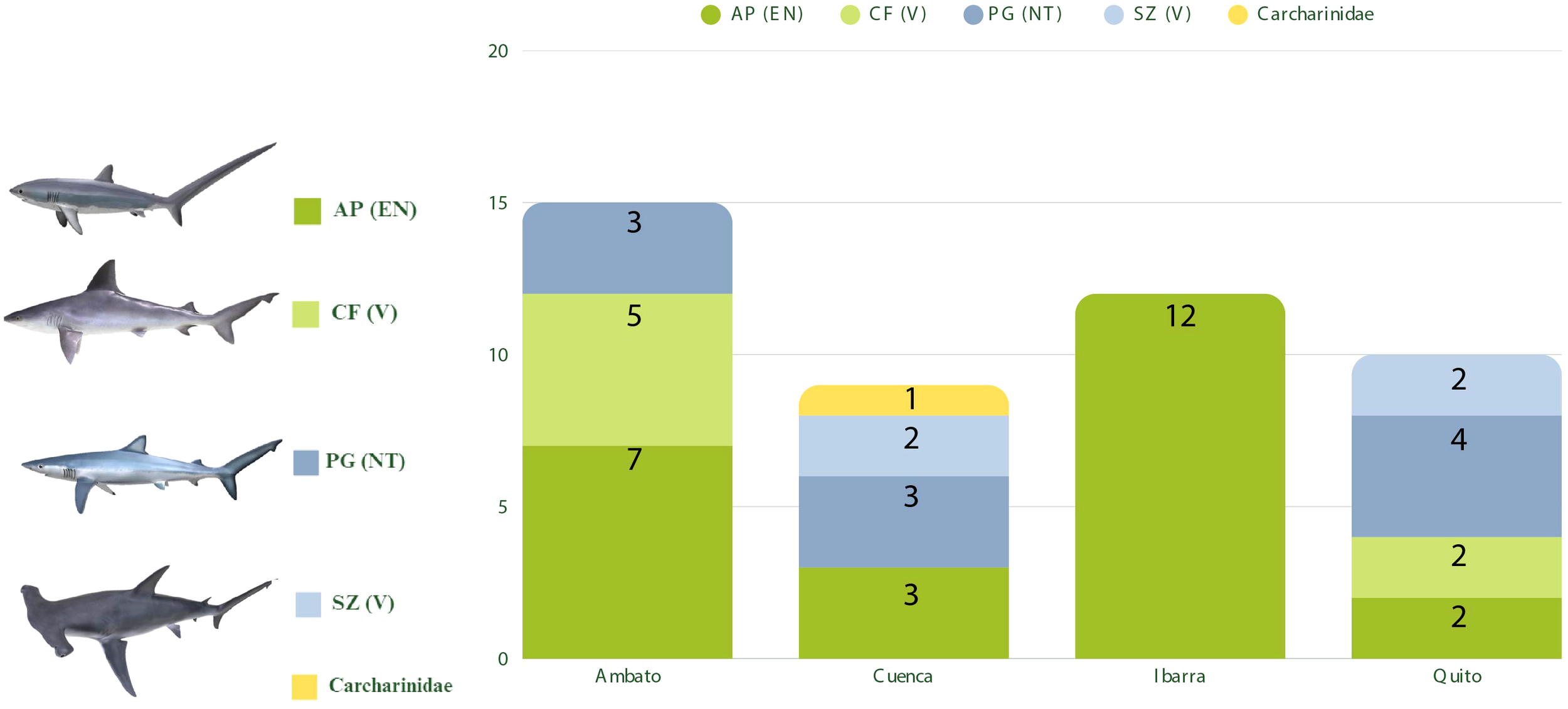

Among the samples that were identified as shark, the family with the highest prevalence was Alopiidae (52.17%), followed by Carcharhinidae (39.13%), and lastly Sphyrnidae with 8.7%. As shown in Figure 2, the identified species and their numbers were: 24 Alopias pelagicus (52.17%), 10 Prionace glauca (21.74%), 7 Carcharhinus falciformis (15.22%), and 4 Sphyrna zygaena (8.7%). It is important to note that all the identified species are listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. A. pelagicus is categorized as “Endangered,” C. falciformis and S. zygaena are classified as “Vulnerable,” and P. glauca is listed as “Near Threatened” (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species). Further, S. zygaena has been fully protected since 2020 in Ecuador (Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, 2020).

Figure 2

Shark species identified in fish meat samples from the highlands region and their respective status on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. AP, Alopias pelagicus; CF, Carcharhinus falciformis; PG, Prionace glauca; SZ, Sphyrna zygaena; Carcharhinidae family unidentified shark. IUCN Red List Category; EN, Endangered; V, Vulnerable; and NT, Near Threatened.

4 Discussion

In this study, we conducted random sampling of fish meat being sold mainly as “corvina” in markets of several large cities in Ecuador, from both the coastal region (including the major ports of Guayaquil and Manta) and the highlands region (Ibarra, Ambato, Cuenca and Quito). This study was exploratory in nature and aimed to detect the presence of shark meat in local markets; therefore, it was not designed to make formal statistical inferences about regional prevalence. As a result, the absence of shark detection in coastal markets is reported descriptively and should be interpreted with caution. Our findings are presented as observational results that highlight patterns warranting further investigation using larger and more comprehensive sampling designs. The results obtained show that shark meat is being mislabeled, as 66.6% of the samples collected in the highlands region were identified as shark meat. However, no samples of the samples collected in the coastal region were identified as shark. These data reflect that consumers living in cities in the highlands are unknowingly buying and consuming shark meat, believing they are buying other types of fish (Silva et al., 2021). Although rays are also of conservation concern and occurs in Ecuadorian waters and markets, they were not included in the sampling or analysis of this study (Niedermüller et al., 2021; Palacios et al., 2025).

From a methodological perspective, the ITS-based molecular approach functioned as a reliable qualitative screening tool for the detection of shark-derived products in market samples sold under alternative commercial names. Amplification with universal shark ITS primers provide unambiguous evidence that a sample corresponds to shark meat. Species-level identification was achieved only when amplification occurred with primers that have been specifically validated for individual shark taxa (Pank et al., 2001; Shivji et al., 2002; Abercrombie et al., 2005; Pinhal et al., 2012; Hidalgo Manosalvas, 2013; Mateo Calderón, 2014; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). Consequently, species assignment is inherently restricted to those taxa for which validated primers are available. Importantly, samples that did not amplify with the universal shark primers are interpreted as negative for shark DNA, indicating that the meat does not correspond to shark products. Overall, this approach allows robust discrimination between shark and non-shark products, while species-level resolution is limited to the validated primer set.

Previous studies in Ecuador have found that shark meat is sold nationwide, particularly in the highlands, where it is often mislabeled and marketed as a higher-value fish species (Mateo Calderón, 2014; Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). In general, research indicates that consumers in the Andes, where there is less of a fish-eating culture than in coastal areas, struggle to differentiate between shark species because the meat is typically sliced and packaged, making identification difficult (Bornatowski et al., 2015). Similar patterns of shark meat mislabeling have been reported across Latin America, including Argentina (Delpiani et al., 2020), Brazil (Alvarenga et al., 2024), and Guatemala (Kasana et al., 2025), where multiple species, often pelagic and threatened, are sold under generic or incorrect labels. Comparable cases have also been documented in United States (Ahles et al., 2025), Ghana (Agyeman et al., 2021), Singapore (French and Wainwright, 2022) and Taiwan (Liu et al., 2013). These examples confirm that shark meat mislabeling is a widespread issue globally and often involves the same few pelagic and threatened shark species.

In this broader context, our study identified four shark species in Ecuadorian markets: Alopias pelagicus, Prionace glauca, Carcharhinus falciformis, and Sphyrna zygaena. The recurrence of these species in different regions underscore their importance in the global shark meat trade and highlights their continued exploitation despite conservation concerns. Based on the literature analyzed for this study, Sphyrna zygaena has not previously been reported as being sold in Ecuadorian markets (Oceana; Pank et al., 2001; Mateo Calderón, 2014). Alopias pelagicus (pelagic thresher shark) is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List, with global populations declining due to high fishing pressure (IUCN, 2018a). This species is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical waters of the Indo-Pacific, including the Eastern Tropical Pacific, where it is frequently caught as bycatch in longline and gillnet fisheries (Martínez-Ortiz et al., 2015; Sánchez-Latorre et al., 2023). Its low fecundity makes it particularly vulnerable to overexploitation, while demand for its fins drives further pressure (Mejía et al., 2024). The species is included in CITES Appendix II, meaning international trade must be controlled to avoid further population declines (CITES, 2025).

Carcharhinus falciformis (silky shark) is categorized as Vulnerable (IUCN, 2017). It is one of the most abundant pelagic sharks globally, yet also among the most heavily exploited. In the Eastern Tropical Pacific, silky sharks are a common bycatch in tuna purse seine and longline fisheries, and they are targeted for both meat and fins (Clarke et al., 2006; Martínez-Ortiz et al., 2015). Although Ecuador prohibits directed shark fishing, this species continues to be landed in significant numbers under the incidental catch exception, creating a loophole that undermines conservation measures (Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, 2022). Like the pelagic thresher, silky sharks are listed under CITES Appendix II (CITES, 2025).

Sphyrna zygaena (smooth hammerhead) is listed as Vulnerable and has suffered declines exceeding 50% over the last three generations (IUCN, 2018b). It has a cosmopolitan distribution in temperate and tropical waters and uses shallow coastal areas as nurseries, which makes juveniles particularly susceptible to fishing (Abercrombie et al., 2005). Smooth hammerhead fins are highly valued in international markets, contributing to intense fishing pressure (Abercrombie et al., 2005; Clarke et al., 2006). Since 2020, Ecuador has granted full legal protection to S. zygaena, prohibiting its capture, landing, and trade (Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, 2020). Despite this protection, our findings indicate that this species is still entering markets under false labels.

Prionace glauca (blue shark) is currently considered Near Threatened (IUCN, 2018c). It is the most widely distributed pelagic shark and one of the most heavily fished globally, with millions caught annually as bycatch in tuna and swordfish fisheries (Nakano and Stevens, 2008; Da Silva et al., 2021). Although it remains relatively more abundant than other species, evidence shows that populations are declining, particularly in the North Atlantic and Pacific (Nakano and Stevens, 2008). Its meat is widely sold, often mislabeled, and in 2023 it was added to CITES Appendix II, reflecting international concern over unsustainable exploitation (CITES, 2025).

Taken together, these species-level assessments highlight that the sharks identified in Ecuadorian markets are already recognized as threatened or declining on a global scale. Their continued mislabeling and sale not only undermine consumer rights and food safety but also exacerbate conservation challenges by concealing the true magnitude of exploitation. These results emphasize the urgent need for improved traceability systems, stricter enforcement of existing protections, and alignment of Ecuador’s fisheries management with global conservation commitments (Dulvy et al., 2021; Pacoureau et al., 2023).

One of the Carcharhinidae samples could not be identified to the species level. This limitation arises because the primers used in this study were specifically designed for the identification of C. falciformis and C. galapagensis. As a result, the unidentified sample may belong to another shark species reported in Ecuadorian waters, such as C. obscurus, C. leucas, C. limbatus, C. porosus, C. longimanus, Carcharodon carcharias, or Galeocerdo cuvier. These species have been previously documented in the region (Jacquet et al., 2008; Salinas De León et al., 2016; Briones-Mendoza et al., 2022; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022).

In Ecuador, where shark fishing is largely prohibited—with the exception of incidental catch regulated by permits from the Ministry of the Environment (Castro, 2022; Tiktak et al., 2024)—weak enforcement and limited monitoring and surveillance have created conditions that enable the continued commercialization of shark products. The lack of traceability and regulatory control over incidentally caught sharks makes it relatively easy for their meat to be mislabeled and sold as more familiar fish species (Ryburn et al., 2023). This issue is exacerbated by a complex and opaque supply chain that depends heavily on intermediaries, making it difficult to monitor trade and enforce regulations effectively (Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018). Despite a 17-year ban on directed shark fishing, bycatch is frequently used as a loophole to justify landings, while insufficient numbers of fisheries inspectors further undermine compliance, particularly at mainland ports (Castro, 2022). It is unclear at which stage of the supply chain the mislabeling occurs. An analysis of shark mobilization permits within Ecuador found that significant quantities of shark meat do leave port towns with the correct paperwork, with Quito being the destination that receives the largest proportions of sharks mobilized internally from Santa Rosa, Manta and Esmeraldas (Domínguez and Cobeña, 2019). However, although correctly-labeled shark meat, or shark meat labeled as “tollo” (another term used exclusively for shark meat) may be found in markets in the Andean region (Domínguez and Cobeña, 2019), our results, combined with those of previous studies, suggest that mislabeling is widespread (Mateo Calderón, 2014; Manzanillas Castro and Acosta-López, 2022). There is little that the end-consumer can do about this, given that the product is generally consumed unknowingly.

This prevalence of mislabeling across the Andes infringes consumer rights to make informed choices about their purchases, in particular when seeking to avoid seafood with high levels of mercury and other toxins that can be harmful to pregnant women and children. For example, a recent study of mercury content in fish in Ecuador recommended dorado and croaker (another species within the “corvina” assemblage) as healthy choices as opposed to shark and marlin (Yánez-Jácome et al., 2023). Furthermore, brotula and weakfish are sold at least twice as expensive as shark meat, which means that consumers may unknowingly pay a higher price for a lower-value product. Finally, one of the arguments to allow the sale of incidentally-caught sharks is that, because they are used integrally, they are an important food source for communities (Brown, 2024). This argument loses force when faced with widespread mislabeling and when it is estimated that just under 50% of consumers of shark meat do so unwittingly (Domínguez and Cobeña, 2019).

To date, there is still no clear definition of by-catch, so shark fishing continues unabated, with over 250,000 sharks landed each year (Martínez-Ortiz et al., 2015). According to the Ecuadorian Fisheries Agency (SRP), from 2007–17 sharks were the third most important group of fish landed, after tuna and dorado (Domínguez and Cobeña, 2019), and the findings of this study, alongside previous reports, confirm that shark meat from threatened and endangered species listed under CITES Appendix II (and in the case of S. zygaena, fully protected in Ecuador) continues to appear in local markets, especially in the Andean region. Although Ecuador is a CITES signatory and therefore committed to regulating trade in endangered species, persistent gaps in traceability, vague definitions of bycatch, and inconsistent reporting of shark landings and exports have led to international concerns. Notably, CITES has recommended suspending commercial transactions involving sharks and rays from or originating in Ecuador (Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, 2024).

Three key recommendations emerge from the results of this study to confront the problem of mislabelled shark meat sales. Firstly, it is crucial to establish and implement a robust traceability system that tracks the seafood supply chain from catch to market. Such a system would help verify the authenticity of the species being sold, reducing the likelihood of mislabeling. Secondly, routine monitoring should be carried out to periodically identify which fish species are being sold in Ecuador’s markets, in order to detect potential cases of species substitution, ensure compliance with existing regulations, and inform enforcement actions. Recent reviews have compiled a full catalogue of rapid DNA and eDNA-based identification tools for Chondrichthyes, including portable PCR, LAMP, and Lab-on-a-Chip technologies (Alvarenga et al., 2025). These methods enable species detection without the need for sequencing and have become increasingly important for biodiversity monitoring and wildlife trade regulation, particularly for threatened and data-poor taxa (Alvarenga et al., 2025). In this context, our study implements one of these rapid diagnostic approaches by combining universal and species-specific PCR assays previously validated for shark identification (Mateo Calderón, 2014; Cevallos Zambrano and Menéndez Delgado, 2018; Briones-Mendoza et al., 2022; Alvarenga et al., 2025). This workflow is time and cost effective, relies on widely accessible laboratory resources, and is therefore well suited for regions where sequencing infrastructure is limited. By implementing a validated and cost-effective method within a Global South context, we demonstrate the practical integration of rapid DNA-based identification tools to enhance traceability, support enforcement efforts, and increase the feasibility of routine monitoring (But et al., 2020; Tiktak et al., 2024; Alvarenga et al., 2025; Palacios et al., 2025). Finally, the public needs to be informed and educated about the importance of making choices to buy fish from sustainable fisheries. It is crucial to address the problem described in this study in order to advocate for shark species that are being overexploited, threatening their populations, the integrity of marine ecosystems, and the services these ecosystems provide to humans.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because the study focused exclusively on fish meat bought in markets.

Author contributions

JG: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. GP: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. AH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. CS-A: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. PV: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. CH: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. MM: Methodology, Writing – original draft. MT: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Our work was possible thanks to the Universidad San Francisco de Quito COCIBA grants awarded to Juan José Guadalupe and María Mercedes Cobo.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Plant Biotechnology Laboratory at USFQ for their input and support throughout this research. We would also like to thank Cristopher Pineda for his assistance with sample processing. We are grateful to María Mercedes Cobo for her help in securing one of the grants that funded this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work ChatGPT (models3.5 and 4o) was used to improve writing style and grammar checks within the article. After using this tool the authors carefully reviewed, edited and revised the content as needed. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2026.1657072/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abercrombie D. (2004). Efficient PCR-based identification of shark products in global trade: applications for the management and conservation of commercially important mackerel sharks (Family lamnidae), thresher sharks (Family alopiidae) and hammerhead sharks (Family sphyrnidae). HCNSO Stud Theses Diss (Fort Lauderdale, Florida). Available online at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/131 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

2

Abercrombie D. L. Clarke S. C. Shivji M. S. (2005). Global-scale genetic identification of hammerhead sharks: Application to assessment of the international fin trade and law enforcement. Conserv. Genet.6, 775–788. doi: 10.1007/s10592-005-9036-2

3

Agyeman N. A. Blanco-Fernandez C. Steinhaussen S. L. Garcia-Vazquez E. MaChado-Schiaffino G. (2021). Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fisheries threatening shark conservation in african waters revealed from high levels of shark mislabelling in Ghana. Genes.12, 1002. doi: 10.3390/genes12071002

4

Ahles S. DeWitt C. A. M. Hellberg R. S. (2025). A meta-analysis of seafood species mislabeling in the United States. Food Control.171, 111110. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2024.111110

5

Alvarenga M. M. Bunholi I. V. Adachi A. M. C. L. Cruz M. M. Feitosa L. M. De Jesus E. V. et al . (2025). Rapid DNA/eDNA -based ID tools for improved chondrichthyan monitoring and management. Mol. Ecol. Resour.25, e70044. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.70044

6

Alvarenga M. Bunholi I. V. De Brito G. R. Siqueira M. V. B. M. Domingues R. R. Charvet P. et al . (2024). Fifteen years of elasmobranchs trade unveiled by DNA tools: Lessons for enhanced monitoring and conservation actions. Biol. Conserv.292, 110543. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110543

7

Bornatowski H. Braga R. R. Kalinowski C. Vitule J. R. S. (2015). Buying a pig in a poke”: the problem of elasmobranch meat consumption in southern Brazil. Ethnobiol Lett.6, 196–202. doi: 10.14237/ebl.6.1.2015.451

8

Briones-Mendoza J. Mejía D. Carrasco-Puig P. (2022). Catch composition, seasonality, and biological aspects of sharks caught in the Ecuadorian pacific. Diversity.14, 599. doi: 10.3390/d14080599

9

Brown K. (2024). CITES warns Ecuador: crack down on illegal shark fishing, now (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Hakai magazine).

10

But G. W. C. Wu H. Y. Shao K. T. Shaw P. C. (2020). Rapid detection of CITES-listed shark fin species by loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay with potential for field use. Sci. Rep.10, 4455. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61150-8

11

Castro M. (2022). Los tiburones en Ecuador: arrasados por la pesca y la falta de información (Quito, Pichincha, Ecuador: GK). Available online at: https://gk.city/2021/07/26/tiburones-Ecuador/ (Accessed January 30, 2025).

12

Cevallos Zambrano D. P. Menéndez Delgado E. R. (2018). La comercialización de la pesca incidental del tiburón realizada por los pescadores artesanales de Manta. ECA Sinerg.9, 37. doi: 10.33936/eca_sinergia.v9i1.971

13

CITES (2025). Appendices I, II and III. Available online at: https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (Accessed January 30, 2025).

14

Clarke S. C. McAllister M. K. Milner-Gulland E. J. Kirkwood G. P. Michielsens C. G. J. Agnew D. J. et al . (2006). Global estimates of shark catches using trade records from commercial markets. Ecol. Lett.9, 1115–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00968.x

15

Constance J. M. Garcia E. A. Pillans R. D. Udyawer V. Kyne P. M. (2023). A review of the life history and ecology of euryhaline and estuarine sharks and rays. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 34, 65–89 Available online at: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11160-023-09807-1 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

16

Da Silva T. E. F. Lessa R. Santana F. M. (2021). Current knowledge on biology, fishing and conservation of the blue shark (Prionace glauca). Neotropical Biol. Conserv.16, 71–88. doi: 10.3897/neotropical.16.e58691

17

Dedman S. Moxley J. H. Papastamatiou Y. P. Braccini M. Caselle J. E. Chapman D. D. et al . (2024). Ecological roles and importance of sharks in the Anthropocene Ocean. Science385, adl2362. doi: 10.1126/science.adl2362

18

Delpiani G. Delpiani S. M. Deli Antoni M. Y. Covatti Ale M. Fischer L. Lucifora L. O. et al . (2020). Are we sure we eat what we buy? Fish mislabelling in Buenos Aires province, the largest sea food market in Argentina. Fish Res.221, 105373. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2019.105373

19

Domínguez C. Cobeña M. (2019). Estudio de comercialización de carne de tiburón en Ecuador, para entender las características específicas del mercado de carne de tiburón y sus subproductos en el país (Guayaquil, Ecuador: WWF-Ecuador).

20

Dulvy N. K. Fowler S. L. Musick J. A. Cavanagh R. D. Kyne P. M. Harrison L. R. et al . (2014). Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. eLife.3, e00590. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590

21

Dulvy N. K. Pacoureau N. Rigby C. L. Pollom R. A. Jabado R. W. Ebert D. A. et al . (2021). Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Curr. Biol.31, 4773–4787.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.062

22

French I. Wainwright B. J. (2022). DNA barcoding identifies endangered sharks in pet food sold in Singapore. Front. Mar. Sci.9,836941. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.836941

23

Gobierno de la República del Ecuador (2008). Decreto Ejecutivo No. 902: Reforma al Decreto Ejecutivo No. 486 sobre la protección de tiburones y rayas. Available online at: https://www.produccion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/PROTECCION-DE-TIBURONES-Y-RAYAS.pdf (Accessed January 30, 2025).

24

Hidalgo Manosalvas C. E. (2013). Protocolo de identificación molecular de especies de tiburón analizando muestras de Galápagos y Puerto López. , Quito: Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Available online at: http://repositorio.usfq.edu.ec/handle/23000/2228 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

25

IUCN (2017). “ Carcharhinus falciformis,” in IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T39370A205782570. Eds. RigbyC. L.ShermanC. S.ChinA.SimpfendorferC. (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/39370/205782570 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

26

IUCN (2018a). “ Alopias pelagicus,” in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T161597A68607857. Eds. RigbyC. L.BarretoR.CarlsonJ.FernandoD.FordhamS.FrancisM. P.HermanK.JabadoR. W.LiuK. M.MarshallA.PacoureauN.RomanovE.SherleyR. B.WinkerH. (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/161597/68607857 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

27

IUCN (2018b). “ Sphyrna zygaena,” in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39388A2921825. Eds. RigbyC. L.BarretoR.CarlsonJ.FernandoD.FordhamS.HermanK.JabadoR. W.LiuK. M.MarshallA.PacoureauN.RomanovE.SherleyR. B.WinkerH. (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/39388/2921825 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

28

IUCN (2018c). “ Prionace glauca,” in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39381A2915850. Eds. RigbyC. L.BarretoR.CarlsonJ.FernandoD.FordhamS.FrancisM. P.HermanK.JabadoR. W.LiuK. M.MarshallA.PacoureauN.RomanovE.SherleyR. B.WinkerH. (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/39381/2915850 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

29

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species ( The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species). (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Available online at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en (Accessed January 30, 2025).

30

Jacquet J. Alava J. J. Pramod G. Henderson S. Zeller D. (2008). In hot soup: sharks captured in Ecuador’s waters. Environ. Sci.5, 269–283. doi: 10.1080/15693430802466325

31

Kasana D. Martinez H. D. Sánchez-Jiménez J. Areano-Barillas E. M. Feldheim K. A. Chapman D. D. (2025). Hunt for the Easter Sharks: A genetic analysis of shark and ray meat markets in Guatemala. Fish Res.283, 107300. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2025.107300

32

Liu S. Y. V. Chan C. L. C. Lin O. Hu C. S. Chen C. A. (2013). DNA barcoding of shark meats identify species composition and CITES-listed species from the markets in Taiwan. PLoS One8, e79373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079373

33

Manzanillas Castro A. B. Acosta-López C. (2022). Molecular identification of shark species commercialised in the ‘17 de Diciembre’ market, Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas-Ecuador. Biodiversity23, 110–117. doi: 10.1080/14888386.2022.2140309

34

Martínez-Ortiz J. Aires-da-Silva A. M. Lennert-Cody C. E. Maunder M. N. (2015). The Ecuadorian artisanal fishery for large pelagics: species composition and spatio-temporal dynamics. PLoS One10, 1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135136

35

Mateo Calderón M. J. (2014). ¿Comemos tiburón? identificación molecular de carne de tiburón de venta en mercados y pescaderías del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito. , Quito: Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Available online at: http://repositorio.usfq.edu.ec/handle/23000/3149 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

36

Mejía D. Mero-Jiménez J. Briones-Mendoza J. Mendoza-Nieto K. Mera C. Vera-Mera J. et al . (2024). Life history traits of the pelagic thresher shark (Alopias pelagicus) in the Eastern-Central Pacific Ocean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.78, 103795. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2024.103795

37

Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca (2020). Acuerdo ministerial nro. MPCEIP-SRP-2020-0084-A. Available online at: https://srp.produccion.gob.ec/normativas_pesqueras/acuerdo-ministerial-nro-mpceip-srp-2020-0084-a/ (Accessed January 30, 2025).

38

Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca (2022). Acuerdo ministerial nro. MPCEIP-SRP-2022-0002-A. Available online at: https://www.produccion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2022/07/MPCEIP-MPCEIP-2022-0002-A.pdf (Accessed January 30, 2025).

39

Motivarash Y. Fofandi D. Dabhi R. Rehanavaz M. Kariya P. (2020). Importance of sharks in ocean ecosystem. J. Entomol Zool Stud.8, 611–613.

40

Nakano H. Stevens J. D. (2008). “ The biology and ecology of the blue shark, prionace glauca,” in Sharks of the open ocean, 1st ed. Eds. CamhiM. D.PikitchE. K.BabcockE. A. (Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK: Wiley), 140–151. doi: 10.1002/9781444302516.ch12

41

Niedermüller S. Ainsworth G. de Juan S. Garcia R. Ospina-Alvarez A. Pita P. et al . (2021). The Shark and Ray Meat Network: A Deep Dive into a Global Affair (Rome, Italy: World Wide Fund for Nature). Available online at: https://sharks.panda.org/images/downloads/392/WWF_MMI_Global_shark:ray_meat_trade_report_2021_lowres.pdf (Accessed January 30, 2025).

42

Oceana What is seafood fraud? Available online at: https://oceana.org/what-seafood-fraud/ (Accessed January 30, 2025).

43

Pacoureau N. Carlson J. K. Kindsvater H. K. Rigby C. L. Winker H. Simpfendorfer C. A. et al . (2023). Conservation successes and challenges for wide-ranging sharks and rays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.120, e2216891120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2216891120

44

Palacios M. D. Weiand L. Laglbauer B. J. L. Cronin M. R. Fowler S. Jabado R. W. et al . (2025). Global assessment of manta and devil ray gill plate and meat trade: conservation implications and opportunities. Environ. Biol. Fishes.108, 611–638. doi: 10.1007/s10641-024-01636-w

45

Pank M. Stanhope M. Natanson L. Kohler N. Shivji M. (2001). Rapid and Simultaneous Identification of Body Parts from the Morphologically Similar Sharks Carcharhinus obscurus and Carcharhinus plumbeus (Carcharhinidae) Using Multiplex PCR. Mar. Biotechnol.3, 231–240. doi: 10.1007/s101260000071

46

Pinhal D. Shivji M. S. Nachtigall P. G. Chapman D. D. Martins C. (2012). A streamlined DNA tool for global identification of heavily exploited coastal shark species (Genus rhizoprionodon). PLoS One7, e34797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034797

47

Roff G. Doropoulos C. Rogers A. Bozec Y. M. Krueck N. C. Aurellado E. et al . (2016). The ecological role of sharks on coral reefs. Trends Ecol. Evol.31, 395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.014

48

Ryburn S. J. Yu T. Ong K. J. W. Alston M. A. Howie E. LeRoy P. et al . (2023). Sale of critically endangered sharks in the United States. Front. Mar. Sci.12, 1604454. doi: 10.1101/2023.07.30.551124v1

49

Salinas De León P. Acuña-Marrero D. Rastoin E. Friedlander A. M. Donovan M. K. Sala E. (2016). Largest global shark biomass found in the northern Galápagos Islands of Darwin and Wolf. PeerJ.4, e1911. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1911

50

Sánchez-Latorre C. Galván-Magaña F. Elorriaga-Verplancken F. R. Tripp-Valdez A. González-Armas R. Piñón-Gimate A. et al . (2023). Trophic Ecology during the Ontogenetic Development of the Pelagic Thresher Shark Alopias pelagicus in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Diversity.15, 1057. doi: 10.3390/d15101057

51

Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (2024). Notification to the parties no. 2024/043: application of article XIII in Ecuador. Available online at: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/notifications/E-Notif-2024-043.pdf.

52

Shivji M. Clarke S. Pank M. Natanson L. Kohler N. Stanhope M. (2002). Genetic identification of pelagic shark body parts for conservation and trade monitoring. Conserv. Biol.16, 1036–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01188.x

53

Silva A. J. Hellberg R. S. Hanner R. H. (2021). “ Chapter 7 - Seafood fraud,” in Food fraud. Eds. HellbergR. S.EverstineK.SklareS. A. (United Kingdom: Academic Press), 109–137. Available online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128172421000087 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

54

Tiktak G. P. Gabb A. Brandt M. Diz F. R. Bravo-Vásquez K. Peñaherrera-Palma C. et al . (2024). Genetic identification of three CITES-listed sharks using a paper-based Lab-on-a-Chip (LOC). PLoS One19, e0300383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300383

55

Yánez-Jácome G. S. Romero-Estévez D. Vélez-Terreros P. Y. Navarrete H. (2023). Total mercury and fatty acids content in selected fish marketed in Quito – Ecuador. A benefit-risk assessment. Toxicol. Rep.10, 647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.05.009

Summary

Keywords

Ecuador, food mislabeling, PCR identification, shark conservation, traceability

Citation

Guadalupe JJ, Pozo G, Hearn AR, Serrano-Abarca C, Viera P, Hidalgo C, Mateo MJ and Torres MdL (2026) Molecular identification of shark meat sold in Ecuadorian markets labelled under different names. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1657072. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1657072

Received

30 June 2025

Revised

22 January 2026

Accepted

30 January 2026

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Juan Pablo Torres-Florez, National Center for Wildlife (Saudi Arabia), Saudi Arabia

Reviewed by

Marcela Alvarenga, Centro de Investigacao em Biodiversidade e Recursos Geneticos (CIBIO-InBIO), Vairão, Portugal

Alicia Schmidt-Roach, PhD, Buro Happold GmbH, Germany

Sergio Matías Delpiani, Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas (CADIC-CONICET), Argentina

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Guadalupe, Pozo, Hearn, Serrano-Abarca, Viera, Hidalgo, Mateo and Torres.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria de Lourdes Torres, ltorres@usfq.edu.ec

†Present address: Carmen Hidalgo, Dentistry School, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.