Abstract

Introduction:

The microbiome is crucial for the health and resilience of marine species; however, in most cases its complexity and host-specific dynamics remain poorly understood.

Methods:

This study provides a multi-year and multi-seasonal analysis of eukaryotic and prokaryotic microbiomes in three ecologically important bivalves - mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), clams (Ruditapes philippinarum), and cockles (Cerastoderma edule) – coexisting within the same coastal ecosystem in the Rı́a of Vigo (NW Spain).

Results:

High-throughput sequencing of the V9 region of 18S rRNA and the V4 region of 16S rRNA genes revealed distinct microbiomes for each bivalve species, demonstrating significant host specificity and a stable microbial composition across seasons. Prevalent eukaryotic parasites, including Mytilicola intestinalis in mussels and trematodes such as Bucephalus minimus in cockles, were identified. Perkinsus olseni and Marteilia cochilia, protozoans associated with bivalve mortality and ecosystem disruption under environmental stress, were also detected. Endozoicomonas and Vibrio dominated the prokaryotic communities of all the three bivalves; however, species-specific bacteriomes were observed due to the presence of other distinct taxa. A meta-analysis comparing bivalve and environmental microbiomes, revealed that despite the microbial diversity in the water column and sediment, each bivalve maintained its own stable and specific microbiome, exceeding the habitat effect. We identified Vibrio, Woeseia and Lutimonas as keystone genera that shape these microbiomes through both competitive and cooperative interactions. Functional predictions suggest that mutualistic relationships enhance host health through metabolic and defensive roles, including the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites.

Conclusion:

These findings demonstrate that host identity is the primary determinant of bivalve microbiome composition, with different keystone taxa that could serve as biomarkers for ecosystem and health monitoring in Rı́a de Vigo.

1 Introduction

Marine bivalves are widely distributed organisms that play crucial roles in coastal ecosystems by providing habitats, interacting with benthopelagic energy fluxes, and maintaining water quality (Robledo et al., 2019). Their filter-feeding activity implies the intake of vast amounts of water, making them valuable bioindicators (Paillard et al., 2022). Furthermore, bivalves hold significant economic importance in aquaculture, with 18.911 million tons of mollusks produced globally for human consumption (FAO, 2024, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2024). Disease prevention and control present significant challenges for bivalve mollusk production (Elston and Ford, 2011). In particular, numerous protists and metazoans can act as potential pathogens implicated in global-scale declines in a wide range of marine species (Harvell et al., 2002; Granek et al., 2005; Panek, 2005). In the Ría de Vigo, a highly productive site where this study was conducted, several parasites associated with bivalve mortality have been identified (Robledo et al., 1994a; Villalba et al., 1997, Villalba et al., 2004). These animals are exposed to a large number of organisms in marine habitats, making host-microorganism interactions a key focus for a fundamental understanding of the marine microbiome and bivalves health (Paillard et al., 2022).

Microbiome studies have gained relevance in recent years due to their implications for organism’s health status and biological activity. Adjustments in the microbiome composition, including bacteria, archaea, micro eukaryotes, fungi and viruses regulate several diseases (Diwan et al., 2023). However, stressful situations and environmental changes can disrupt the microbiota, impairing host health status and increasing susceptibility to diseases (Vezzulli et al., 2018). Moreover, bivalve-associated microorganisms also influence biological processes including digestion, growth, reproduction, and the immune system (Diwan et al., 2023). Therefore, understanding bivalves microbiome is critical and further efforts are needed to elucidate host-microbiome interactions (Pierce and Ward, 2018; Neu et al., 2021; Santibáñez et al., 2022; Akter et al., 2023).

High-throughput technologies provide high-resolution data on microbiome structure, functions and host interactions offering a valuable resource for understanding ecological systems (Robledo et al., 2019). Amplicon sequencing targets hypervariable regions of ribosomal genes (16S rRNA gene for bacteria and 18S rRNA gene for eukaryotes) to identify specific taxa (Popovic and Parkinson, 2018). The application of this technology has advanced our understanding of the microbiome in complex marine environmental samples (Amaral-Zettler et al., 2009a; Ríos-Castro et al., 2022), facilitating a deeper comprehension of the functional activities within bacterial communities (Pierce and Ward, 2018; Vezzulli et al., 2018). Eukaryotic profiling presents a challenge because bivalve host DNA, itself eukaryotic, can be amplified alongside that of the eukaryotic microbiota, potentially concealing significant results. Therefore, several strategies have been developed to overcome these limitations (Carnegie et al., 2003; Bower et al., 2004; Vestheim and Jarman, 2008; Amaral-Zettler et al., 2009b; Leray et al., 2013; Hadziavdic et al., 2014; Hugerth et al., 2014; Bass and Del Campo, 2020; Mayer et al., 2021; Minardi et al., 2022; Muñoz-Colmenero et al., 2024), although further improvements are still necessary.

In the present study, high-throughput sequencing was performed on the V9 region of the 18S rRNA gene (eukaryotes) and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (prokaryotes). This approach enabled us to characterize the resident and transient microbial communities in clams, mussels and cockles from the same geographical area. We further extended the analysis to include environmental samples, comparing the bivalve microbiomes with those of the surrounding water column and sediment as previously described by Ríos-Castro et al (Ríos-Castro et al., 2022). Additionally, a functional metabolic analysis was conducted to assess the impact of microbial-bivalve interactions on the biology and health of these mollusks.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity was evaluated in three species of bivalves sampled from Meira (Ría de Vigo, NW Spain). The sampled bivalves were mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), clams (Ruditapes philippinarum) and cockles (Cerastoderma edule), with 15 individuals of each species collected at different sampling points. The first sampling was performed in the summer of 2016, and the subsequent samplings were performed approximately every three months (i.e., seven sample collections from 2016 to 2018). Mussels were sampled in the intertidal zone, and cockles and clams at 6–7 cm deep in the sediment. Figure 1A shows the experimental layout. After the collection of specimens, they were transported to the laboratory, where a fragment was fixed for further histological procedures. The other part of the samples was preserved in 99–100% ethanol at room temperature (25°C) to enable DNA extraction. For the subsequent analyses, some data from the first sampling point (July 2016) were not available due to the poor quality of the DNA. These samples were: cockle (for 18S rRNA gene) and mussel and cockle (for 16S rRNA genes). R. philippinarum was included despite being non-native to European waters as it constitutes a significant component of the local aquaculture industry, allowing for a comparison of microbiome adaptation in introduced versus native species within the same ecosystem.

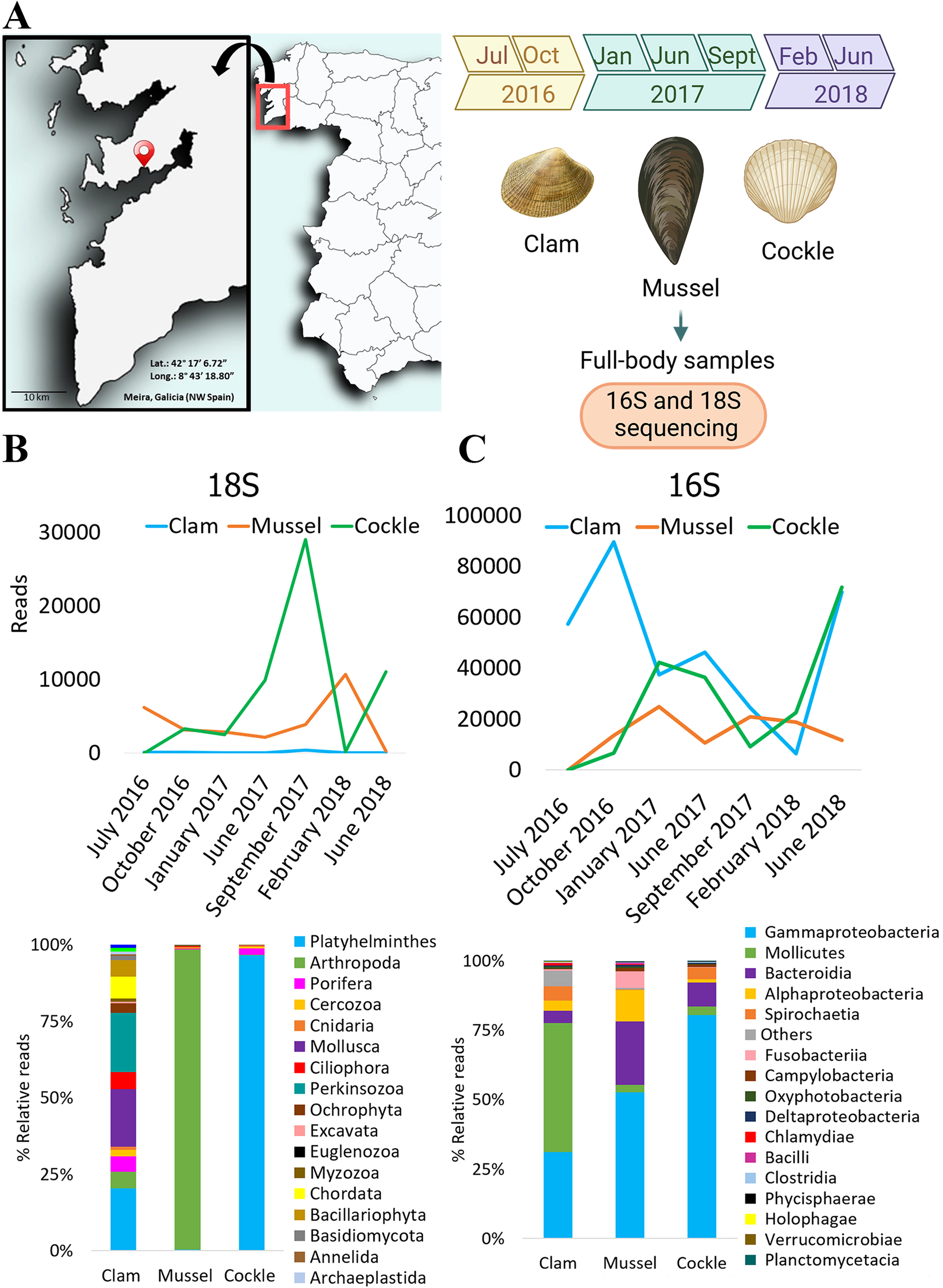

Figure 1

(A) Location of the bivalve production area under study in Meira (Rı́a de Vigo, NW Spain). The seven sampling points are also shown. (B) Number of 18S raw reads obtained over time and relative abundance (%). Eukaryotes classification at phylum level detected in bivalves. (C) Number of 16S raw reads obtained over time and relative abundance (%). Prokaryotes classification at class level detected in bivalves.

The whole-body sampling approach, while enabling robust species comparisons, limits the resolution of tissue-specific microbiome patterns that may exhibit seasonal variations. Nevertheless, this methodology offers a comprehensive overview of host-specific microbial signatures while minimizing potential bias from organ-specific sampling variations.

2.2 Histological sample processing

Oblique transverse sections, approximately 5 mm thick, including the mantle, gonad, digestive gland and gills, were taken from each specimen after fixation in Davidson solution (Shaw and Battle, 1957). Tissue samples were processed in an automatic tissue processor (Leica TP 1020, Leica Microsystems, Germany), embedded in paraffin wax blocks and cut on a microtome. Sections of 5 µm were first deparaffinized, rehydrated and finally stained with hematoxylin-eosin (Howard et al., 2004). Histological sections were examined for the presence of parasites and pathological alterations using an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i) at 10X and 40X magnification.

2.3 DNA isolation, amplification and sequencing

For DNA isolation, a longitudinal section of the animal body, including fragments of the gonad, mantle, gill, and digestive gland was collected, pooled, and homogenized with a pestle to obtain a representative DNA sample. DNA extraction was performed in batches as sampling progressed using the Maxwell 16 Blood Purification DNA Kit (Promega, Madison, USA), following the manufacturer´s instructions. DNA quality and quantity were estimated with a NanoDrop™ 1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., DE, USA). A pooled DNA sample was obtained for each bivalve species by mixing an equal amounts of DNA (50 ng) extracted from the 15 animals. DNA was stored at -80°C for further analysis.

The V9 region of the 18S rRNA gene (180 bp long) was amplified using the universal eukaryotic-specific primers 1380F/1510R (Amaral-Zettler et al., 2009a). Amplicons were purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The sequencing library was prepared using the Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V2 (Illumina) and the paired-end sequencing (2x300) was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Macrogen, Korea). The raw read sequences obtained were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1083288.

16S rRNA gene PCR amplicon libraries were generated from genomic DNA (Lasa et al., 2019). These primers amplify the V4 hypervariable region. A first target enrichment PCR assay was performed using the 16S rRNA gene conserved primers, followed by a second PCR assay with customized primers that included complementary sequencing adapters (Lasa et al., 2019). Libraries obtained from clam, cockle, and mussel samples collected from July 2016 to June 2018 were sequenced using an Ion Torrent (PGM) Platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA). The raw read sequences obtained were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1082107.

2.4 Bioinformatic analysis

Raw reads were trimmed, and sequencing adapters and low-quality reads were removed. The Microbial Genomics module (Version 25.1) of the CLC Genomics Workbench (Version 25.0.2) was used to perform the analysis.

Following trimming, 18S rRNA gene eukaryotic and 16S rRNA gene prokaryotic reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs).

Prior to the eukaryotic clustering, a custom reference database was created, using 18S rRNA gene sequences from the Bivalvia Class (available in SILVA database v.132 clustered at 97%) to classify and remove host eukaryotic reads. Reads were mapped to this database, allowing a similarity and length fraction threshold of 0,9. Unmapped reads (i.e. 18S rRNA gene sequences belonging to non-host eukaryotes) were clustered at a 97% level of similarity into OTUs applying two different databases: SILVA v.132 clustered at 97% and an 18S rRNA gene Custom database generated in a previous work (Ríos-Castro et al., 2021).

The 16S rRNA gene reads were also clustered into OTUs at a 97% similarity level using the SILVA v.132 database (clustered at 97%). For downstream analysis, reads from all the samples were subsampled to 12,400 to ensure comparable sequencing depth.

Singletons and chimaeras were detected and removed. Only reads occurring at least twice in the trimmed dataset were retained for analyses.

2.5 Alpha and beta diversity

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic alpha diversity were analyzed using the Vegan R package. The Shannon and Simpson indices, Fisher’s alpha, and OTU richness were calculated for each bivalve sample across different seasons.

Beta diversity analysis was performed by calculating Bray–Curtis distances and applying Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) to the distance matrices. Based on the Bray-Curtis and Jaccard dissimilarity indices, a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed using the Microbial Genomics Module of the CLC Workbench 25.1 software.

Both, alpha- and beta-diversity analyses were performed at the OTU taxonomic level.

2.6 Eukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity of bivalves and environmental samples

Environmental data from a previous study (Ríos-Castro et al., 2022) were used to conduct a meta-analysis. For eukaryotes, we explored the potential presence of parasites in bivalves in relation to their surrounding environment (water and sediment) from the same area. For prokaryotes, we compared diversity patterns among bivalves, sediment, and water, and constructed co-occurrence networks between the bivalve microbiome and habitat-associated bacteria. These networks allowed us to identify keystone taxa, which we subsequently examined for functional profiles.

Differences in prokaryotic diversity indices were statistically tested using ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. However, for the Simpson index, the differences were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test due to the non-compliance with the assumption of homoscedasticity of variances. A square root transformation of the data for Fisher’s alpha diversity was applied to normalize the data distribution.

2.7 Prokaryotic co-occurrence networks

Network analyses were conducted to detect potential keystone interactions within the prokaryotic communities of each bivalve and its surrounding environment (mussel-water column, clam-sediment and cockle-sediment). To prevent habitat effects, centered log-ratio (CLR) abundances of prokaryotes were corrected using the habitat filtering (HF) algorithm (Brisson et al., 2019). Spearman correlations with an | ρ | > 0.7 were used to generate the co-occurrence network. Networks were visualized through Gephi using the Force Atlas layout. Singleton nodes without edges and loops were removed from the network. Keystone species were identified by calculating the node degree and betweenness centrality (Degree > 12 and Betweenness centrality > 200). These metrics were obtained using Brandes’ algorithm (Brandes, 2001). Bacterial communities were also identified (Blondel et al., 2008).

2.8 Prediction of metagenome functions

Functional activities associated with keystone taxa from each bivalve-habitat network were also predicted. For this purpose, a Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States analysis (PICRUSt2 v.2.5.0) was performed based on the abundance OTU tables (including taxa with OTUs composed of more than four reads). Subsequently, the most relevant predicted EC pathways were associated with specific keystone taxa. In this way, some of the detected enzymes could be related to the metabolic pathways in which they are involved.

3 Results

3.1 Sequencing results

A total of 3,215,210 raw reads were obtained after sequencing the 18S rRNA gene of the three species of bivalves (20 samples, including mussels, clams and cockles). After trimming, reads were clustered at 97% similarity, resulting in 129 OTUs, using SILVA v132 as reference; and 429 OTUs, using the 18S rRNA gene Custom database as reference. Of this, 61 and 62 OTUs were based on the reference databases, while 68 and 367 were de novo OTUs, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, 1,385,256 reads were obtained after sequencing of bivalve samples (19 samples including mussels, clams and cockles). After trimming, reads were clustered at 97% similarity, resulting in 2,050 OTUs. In this case, 1,455 OTUs were based on the reference SILVA v132 database, while 595 were de novo OTUs. Following read standardization, 1,295 OTUs were obtained and used for the subsequent analyses (Supplementary Table 1).

In both cases, OTUs with a combined abundance across all samples ≤5 reads were excluded from the analysis to reduce non-representative taxa.

3.2 Bivalves eukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity

Eukaryotic diversity was evaluated in Cerastoderma edule, Mytilus galloprovincialis and Ruditapes philippinarum sampled from Meira, Ría de Vigo (NW Spain).

For 18S rRNA gene, cockles and mussels showed higher abundance than clams, reaching the highest amount in summer 2017 and winter 2018 (29,033 and 10,683 reads, respectively). In contrast, clam reads remained consistently very low in all sampling points, being not sufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The eukaryotic phyla exhibited completely different profiles among the three bivalves (Figure 1B). While some variations in the microbiome pattern were observed across the sampling points, no clear seasonality was detected (Supplementary Figure 1). Clams had a wide variety of taxa, while mussels and cockles showed clear dominant phylotypes. The Arthropoda phylum was predominant in mussels, reaching more than 95% of the total OTU abundance, whereas the Platyhelminthes phylum was predominant in cockles, with more than 90% of the total OTUs (Figure 1B).

For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the highest number of reads was observed in clam samples (October 2016) (Figure 1C). Reads from clams and cockles varied, increasing in abundance from February to June 2018. The maximum read values for both bivalves were 89,533 and 71,749, respectively. On the contrary, mussel reads were less abundant and remained relatively constant in all the sampling points, reaching a maximum value of 24,923 reads. The bacterial class profiles shared several predominant classes across the three bivalve species, although their relative abundances differed among hosts (Figure 1C). Specifically, the Gammaproteobacteria class was the most predominant in cockles (80,4%) and mussels (52,4%). In contrast, Mollicutes was the most dominant bacterial class in clams (46,4%), but negligible in the other bivalves (~3%). Bacteroides were also abundant in mussels (22,7%) but not relevant in cockles (8,7%) and clams (abundance below 5%). Finally, the abundance of the Alphaproteobacteria class was also remarkable in mussels (11,3%) (Figure 1C). Differences in bacterial class profiles of clams, mussels and cockles throughout the experiment could not be attributed to apparent seasonality (Supplementary Figure 2).

We calculated several alpha diversity indices to compare the diversity among the three bivalve species across the experiment, and no significant differences were found among bivalves or between seasons (Supplementary Figure 3).

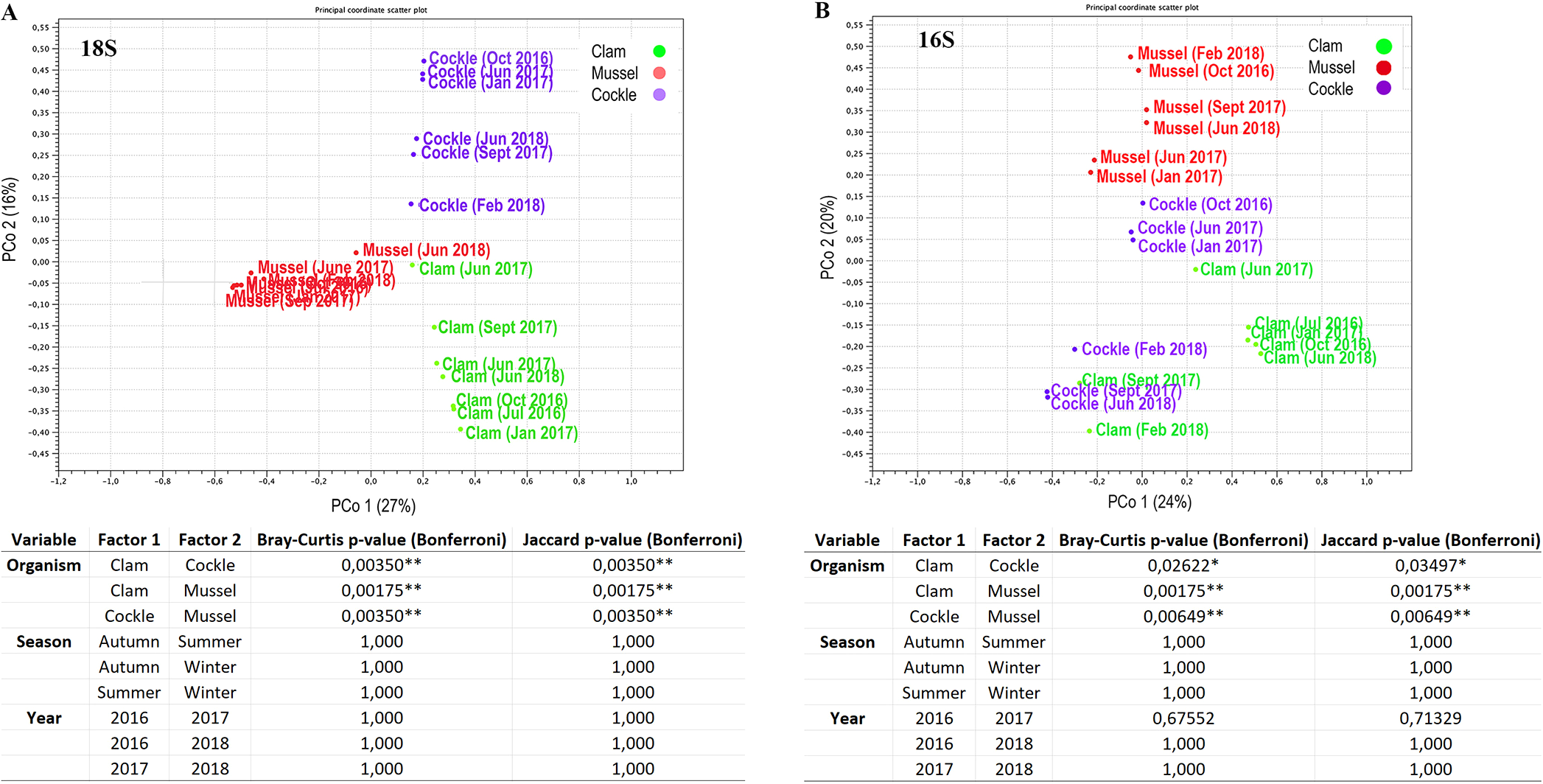

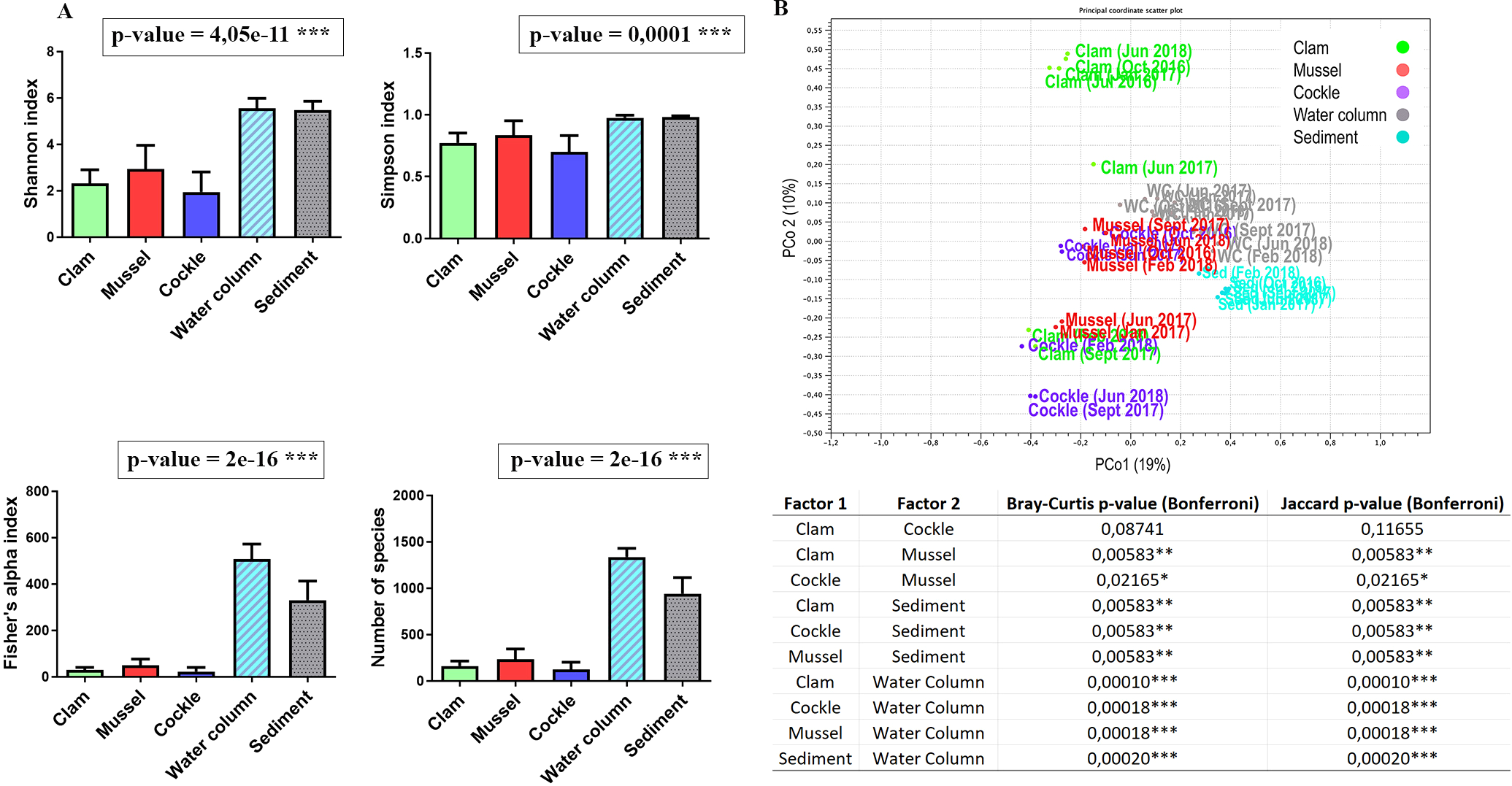

Beta diversity analyses revealed distinct eukaryotic and prokaryotic community composition among bivalves. The diversity of both the 16S rRNA gene and 18S rRNA in clams, mussels and cockles was different (Figure 2). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on the Bray-Curtis and Jaccard dissimilarity indices considering the three variables of the sampling procedure (organism, year and season) confirmed significant species-specific differences (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Beta diversity analysis. (A) PCoA based on Bray-Curtis distances to represent the eukaryotic composition and PERMANOVA analysis. (B) PCoA based on Bray-Curtis distances to represent prokaryotic composition. Pairwise comparisons from the PERMANOVA statistics based on the Bray-Curtis and Jaccard indices. P-values are represented for each comparison pair. Statistically significant differences are displayed as follows: p-value < 0.05 (*); p-value < 0.01 (**).

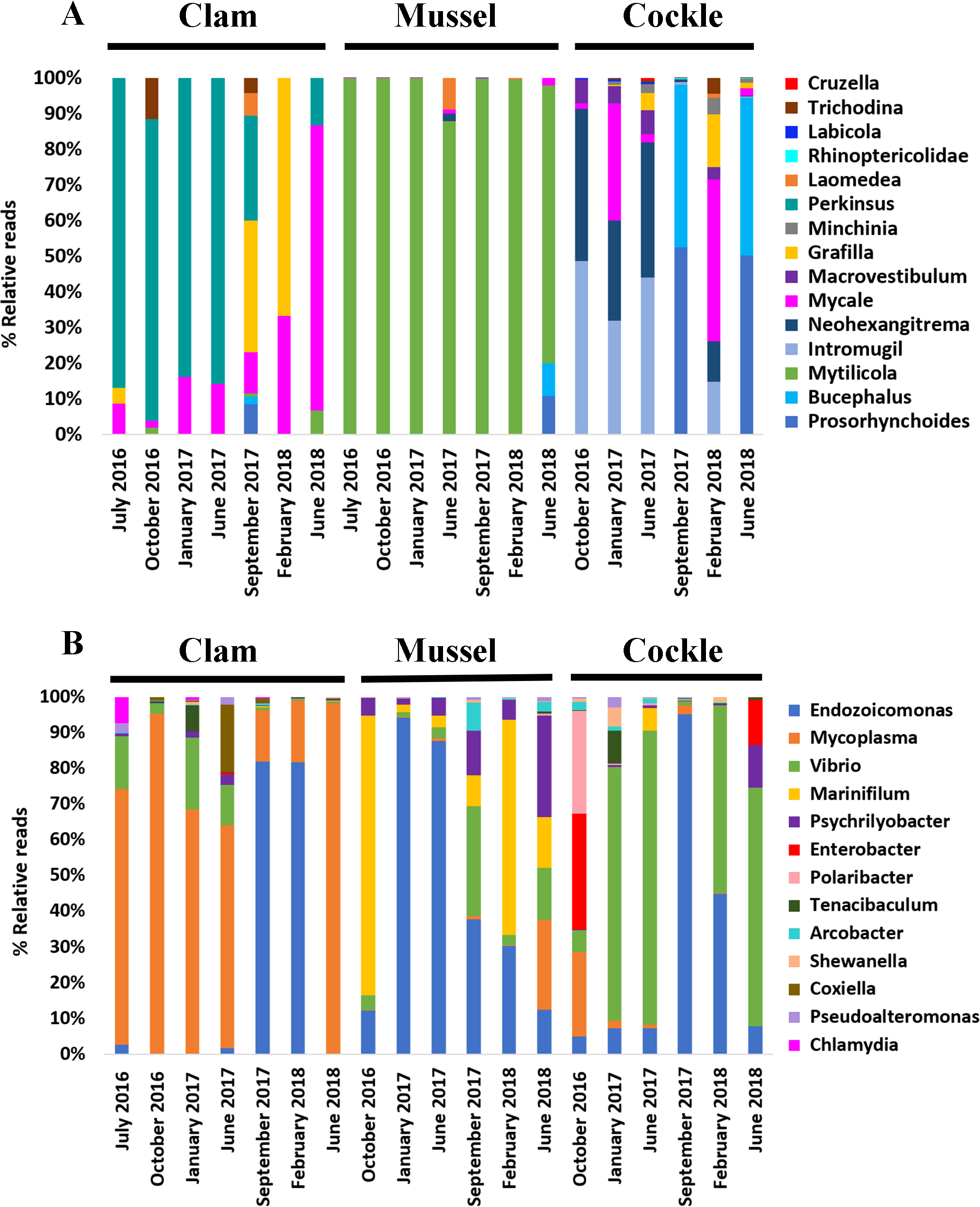

The eukaryotic microbiota included several bivalve parasites. The copepod Mytilicola intestinalis (74-99% of relative abundance) was consistently detected in mussels across all sampling points. In contrast, several platyhelminth species, such as Neohexangritrema zebrasomatis and Intromugil mugilicolus, were detected in cockles for most of the sampling period, representing 14% to 48% of the relative abundance. It was also interesting to detect Bucephalus minimus and Prosorynchoides borealis in September 2017 and June 2018. The genus Mycale was mainly detected during the winter season (January 2017 and February 2018). Furthermore, Perkinsus olseni was detected in the three bivalves and Minchinia merecenariae and Marteilia cochillia were present in cockles, although with low coverage (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

Microbiota composition (relative abundances). (A) The most abundant eukaryotic genera found in each bivalve over time. (B) The most abundant prokaryotic genera found in each bivalve over time.

Regarding the bacterial profile, Endozoicomonas was one of the most abundant genera detected in all bivalve samples. Its abundance in mussel tissues decreased from January 2017 to June 2018 (from 94,2% to 12% relative abundance). In contrast, Endozoicomonas increased its prevalence in clams (1% to 81,9%) and cockles (7,3% to 95,2%) in the same period. Interestingly, in June 2018 (the last sampling point of our analysis) its abundance was practically non-existent in all three bivalve species. Vibrio genus was present in all bivalve samples, but it prevailed in cockles with relative abundance values ranging from 52,5% to 82,5%. Moreover, Mycoplasma was highly associated with clams since it was dominant for most of the studied period (62,3 to 98,1%), only being detected in mussels and cockles in June 2018 (25,3%) and October 2016 (23,6%), respectively. Finally, the genera Marinifilium and Psychrilyobacter were especially abundant in all mussel samples, but almost undetectable in clams or cockles. The detection of the genus Bacillus in mussels, specifically Bacillus cereus, should also be mentioned, though at relative abundances below 1% (Figure 3B).

Despite sharing a common environment, the microbiomes of the three species exhibited minimal seasonal variability and strong species-specific signatures, indicative of robust host selection.

3.3 Microbiome meta-analysis: bivalves and environmental samples

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity in the water column and sediment from the same geographical area in Meira, Ría de Vigo (NW Spain) was previously studied (Ríos-Castro et al., 2021, Ríos-Castro et al., 2022). A meta-analysis was conducted to compare the bivalve microbiome with those of the surrounding environment.

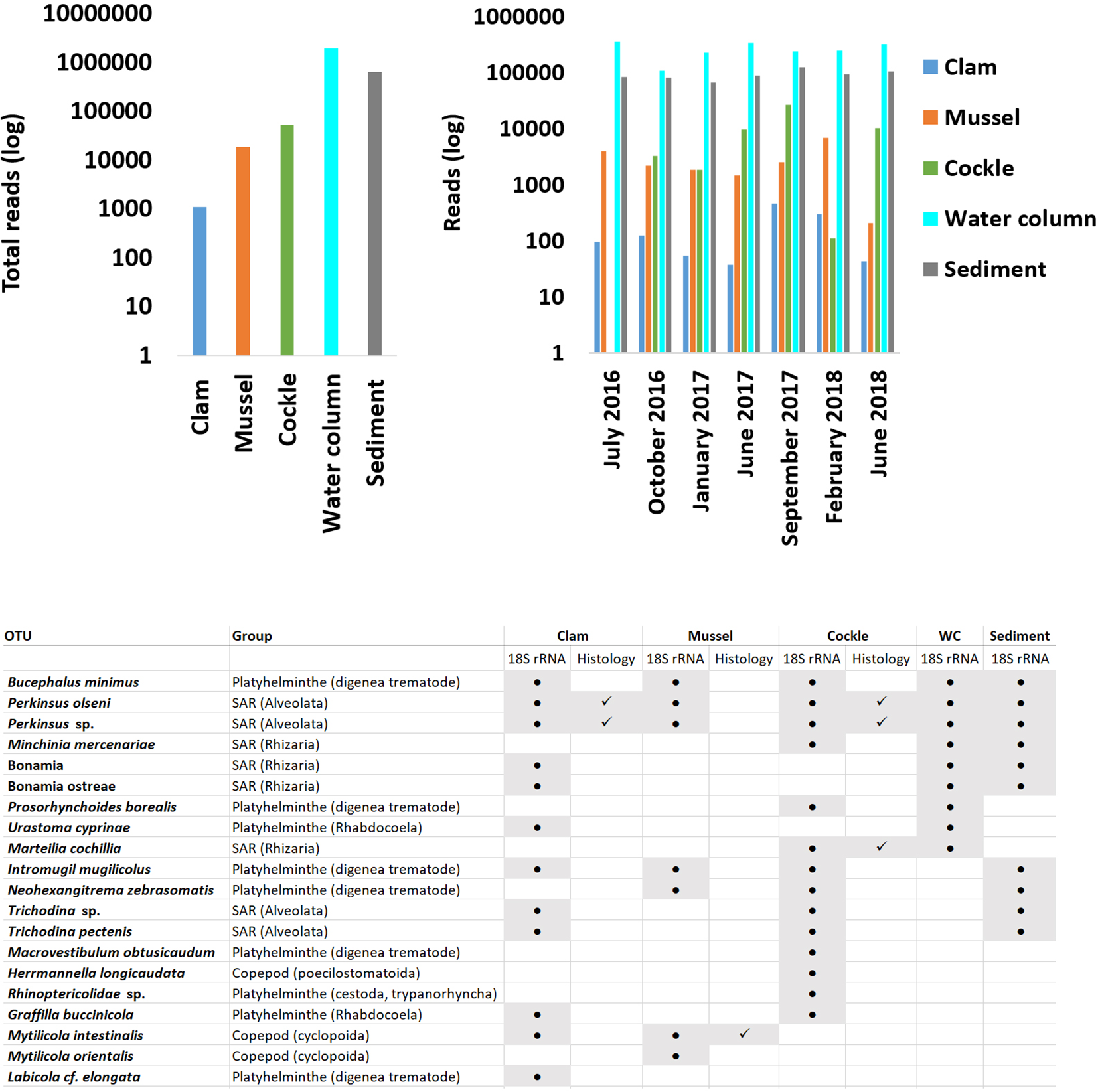

The raw abundance of eukaryotic reads obtained from clams, mussels and cockles was considerably lower than that in water column and sediment samples primarily due to the detection hosts 18S rRNA gene (Figure 4). However, the sequencing depth was sufficient to detect several bivalve parasites and potential pathogens. These OTUs corresponded to protozoans, platyhelminths and copepod parasites. Most parasites found in bivalves were also present in the environment, including the water column, sediment, or both. Parallel histological examinations of the same specimens corroborated the presence of some parasites detected by metagenomics.

Figure 4

Number of 18S rRNA reads obtained in bivalves and environmental samples. The left panel shows the total number of reads, and the right panel shows the number of reads over time. The table indicates the presence or absence of each eukaryotic parasite detected in the three bivalve species and in the environmental samples by molecular biology (18S rRNA column). It includes an additional column specifying whether each parasite was detected by histology (Histology column).

Protozoans of the genus Perkinsus, specifically Perkinsus olseni and the trematode Bucephalus minimus were commonly found in the two environmental samples and the bivalves. The presence of P. olseni was further confirmed histologically in clams and cockles. Other protozoans, such as Minchinia mercenariae, Marteilia cochilia, or the platyhelminth Prosorhynchoides borealis present in the environment, were only detected in cockles with M. cochilia additionally corroborated by histology. Similarly, the platyhelminth Urastoma cyprinae was found only in clams.

Only a few parasites were present exclusively in bivalves. These included the platyhelminth Macrovestibulum obtusicaudum, the genus Rhinopericolidae and the copepod Herrmannella longicaudata in cockles, and the copepod Mytilicola orientalis in mussels. The trematode Labicola cf. elongata was found only in clams. Finally, some parasites such as Grafilla buccinicola and Mytilicola intestinalis were present in various bivalves, with M. intestinalis confirmed histologically in mussels (Figure 4).

Despite the detection of several parasites by molecular and histological approaches, all examined individuals of the three bivalve species exhibited good health, with no histopathological signs of disease (Supplementary Figure 4).

Significant differences were observed among bivalves, sediment, and water column in terms of bacterial communities (Figure 5). Four different metrics were used to compare bacterial diversity between samples: Shannon index, Simpson index, Fisher alpha and number of species. Sediment and seawater diversities were significantly higher than those found in bivalves (Figure 5A). Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of bacterial diversity showed clear separation between bivalve and environmental samples. However, a certain degree of similarity existed between bivalve microbiomes on one side and environmental microbiome on the other. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on the Bray-Curtis and Jaccard dissimilarity indices revealed significant differences among all groups except for clam and cockle samples (Figure 5B).

Figure 5

Alfa and beta diversity of bivalves and environmental samples. (A) Shannon, Simpson, and Fisher alpha indices and richness estimated for all the samples. Results of ANOVA (except a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA in the case of Simpson index) comparing the alpha diversity indices between each bivalve and environment. (B) PCoA based on Bray-Curtis distance to represent prokaryotic composition. Pairwise comparisons from the PERMANOVA statistics based on the Bray-Curtis and Jaccard dissimilarity indices. P-values were represented for each pair of comparisons. Statistically significant differences are displayed as follows: p-value < 0.05 (*); p-value < 0.01 (**); p-value < 0.001 (***).

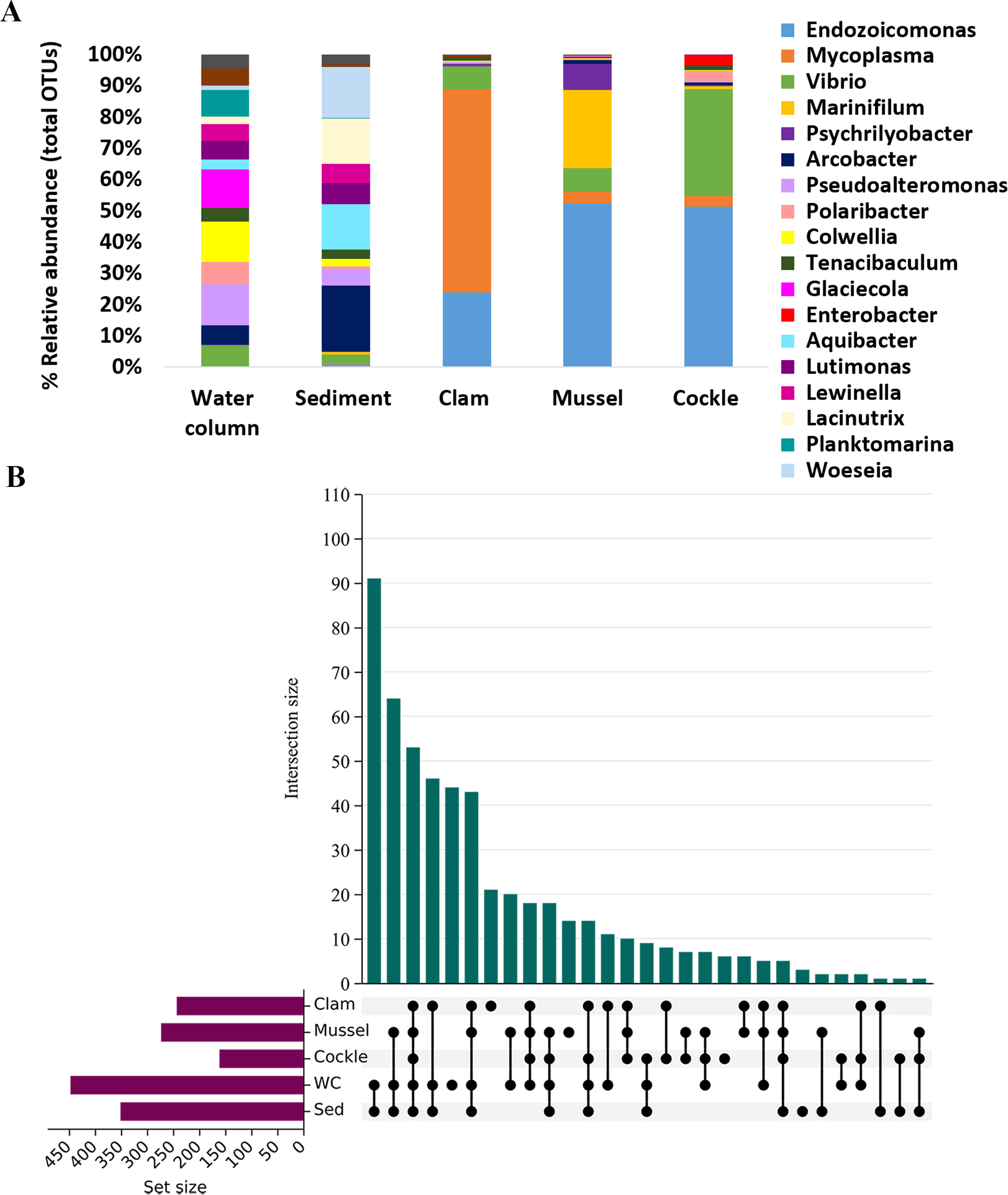

There were also marked differences between the bivalve and environmental bacterial profiles (Figure 6A). The five most abundant genera previously described in the three bivalves (Endozoicomonas, Mycoplasma, Vibrio, Marinifilum and Psychrilyobacter) were either not detected or present only rarely in the water column and sediment (in both cases, with relative abundance below 2%).

Figure 6

Meta-analysis of microbiota composition. (A) The most abundant prokaryotic class for each bivalve and environmental sample (water column and sediment) are shown. The abundances are represented in relative values. (B) Upset plot representing the exclusive and shared OTUs obtained from each bivalve and environmental sample.

In environmental samples, OTUs exhibited a more balanced abundance with no single genus standing out. The most abundant genera in the water column were Pseudoalteromonas, Colwellia and Glaciecola. In the case of sediment, the most abundant genus was Arcobacter, followed by Woeseia, Lacinutrix and Aquibacter.

Water and sediment shared 91 OTUs, while all the bivalves and environmental samples shared 54 OTUs. However, only 10 bacterial taxa were exclusively shared among bivalves, indicating a substantial difference between the bivalve microbiome and the environmental microbial ecosystem (Figure 6B; Supplementary Table 2).

3.4 Co-occurrences between prokaryotic microbiota among bivalves and their habitats

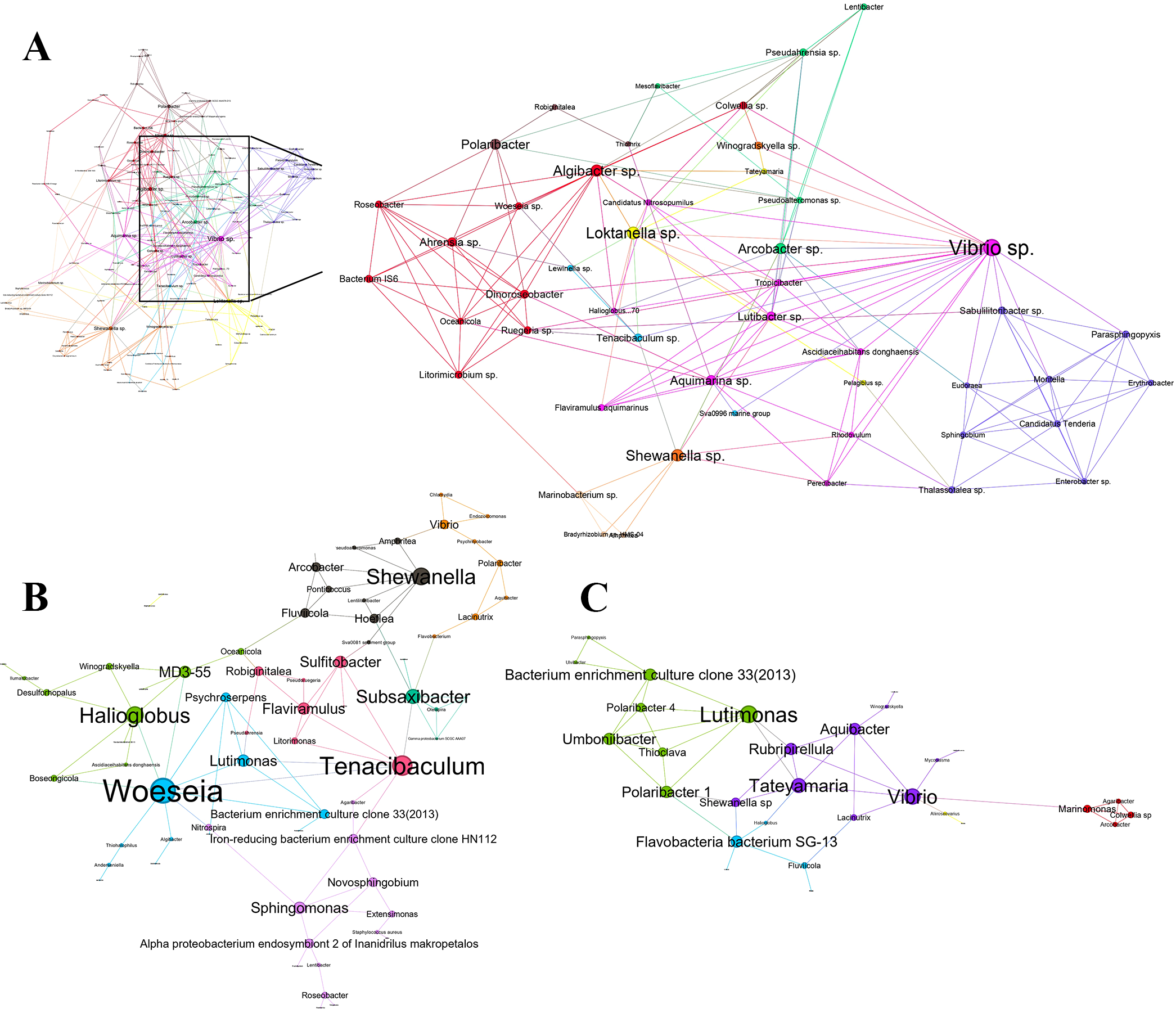

A co-occurrence network was performed to examine the interaction between bivalve and environmental microbiome (Figure 7). Significant correlations were detected between some bacterial taxa within each bivalve and their respective environmental habitats.

Figure 7

Network representing all prokaryote-prokaryote interactions in (A) mussel-water system, (B) clam-sediment system, and (C) cockle-sediment system. Each node represents an OTU (size proportional to each node degree). The links between the nodes indicate a strong and significant correlation (p-value < 0.01, Spearman | ρ | > 0.7).

The bacterial network for the mussel and the seawater column was the most complex, with 135 nodes and 766 edges. Positive correlations (437 co-occurrences) were slightly more abundant than negative correlations (329 co-exclusions) (Supplementary Table 3). The most noteworthy keystone taxa were Vibrio sp. (Degree 60, Betweenness Centrality 3291), which had the highest number of interactions with other taxa. Moreover, Loktanella sp. (Degree 42, Betweenness Centrality 2071), Shewanella sp. (Degree 40, Betweenness Centrality 2654), Algibacter sp. (Degree 39, Betweenness Centrality 1401) and Arcobacter sp. (Degree 35, Betweenness Centrality 1521) were also identified as keystone taxa in the mussel-seawater system. Bacterial communities within the network were clustered by prioritizing stronger interactions within clusters over those with the rest of the network. These groups likely represent functionally related taxa or those sharing similar niches. We detected 10 different bacterial communities, each characterized by its relevant species, interacting within the mussel-seawater environment (Figure 7A).

On the other hand, the network of clam-sediment bacteria consisted of 69 nodes and 197 edges in which co-occurrences (127) were also slightly over co-exclusions (68) (Supplementary Table 3). In this case, Woeseia (Degree 20, Betweenness Centrality 1728), Tenacibaculum (Degree 16, Betweenness Centrality 1893), Halioglobus (Degree 14, Betweenness Centrality 565), Shewanella (Degree 14, Betweenness Centrality 728) and Subsaxibacter (Degree 12, Betweenness Centrality 1238) were identified as keystone genera. Among these keystone genera, the most notable co-occurrences were observed between the Gammaproteobacteria Woeseia sp. and the Bacteroidota Psychroserpens sp. Eight different bacterial communities, with their influenced by the most important species were identified (Figure 7B).

Finally, the cockle and sediment bacterial network comprised 36 nodes and 103 edges. Co-occurrences (61) were slightly higher than co-exclusions (42) (Supplementary Table 3). Lutimonas (Degree 14, Betweenness Centrality 203) and Vibrio (Degree 13, Betweenness Centrality 376) were identified as the keystone species. The most relevant co-occurrences were observed between Lutimonas sp. and Thioclava sp. At the same time, relevant co-exclusions occurred between bacteroides such as Lutimonas sp. - Polaribacter sp. or Vibrio sp. - Aquibacter sp. In this case, eight different bacterial communities and the most important species for every community were also detected (Figure 7C).

3.5 Bacterial metabolic pathways prediction

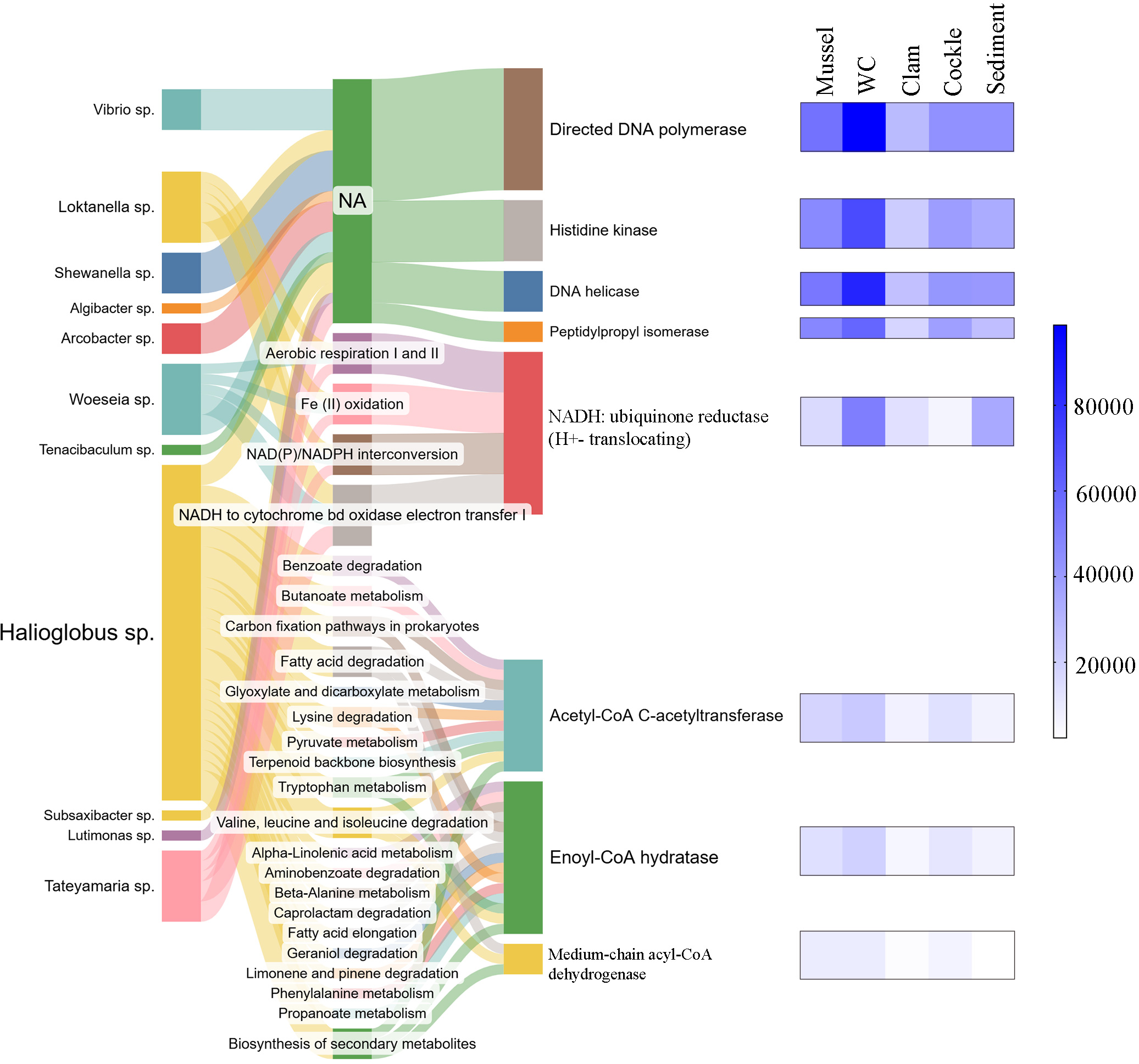

PICRUSt2 was used to predict metabolic pathways associated with the most important keystone bacteria identified across all the samples (bivalves, seawater, and sediment). As a result, we obtained 415 metabolic pathways and 2,185 predicted EC numbers (enzyme functions) among all the OTUs. After selecting the most representative EC numbers for each keystone species, eight enzymes were identified as being involved in 23 different metabolic pathways (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Metabolic pathways and representative enzymes associated with the keystone species found in the bivalve microbiome and environmental samples after PICRUSt analysis.

Examining the predicted enzymatic functions associated with bacterial profiles, DNA polymerase (EC:2.7.7.7) was one of the most representative enzymes shared among all keystone taxa (except in Algibacter sp.). However, the specific metabolic pathways associated with this enzyme could not be clearly resolved. The same occurred for histidine kinase, DNA helicase and peptidoprolyl isomerase enzymes (EC:2.7.13.3, EC:3.6.4.12 and EC:5.2.1.8), which were shared among fewer bacteria, and their specific metabolic functions also remained unclear.

Nevertheless, NADH: ubiquinone reductase (H+-translocating) enzyme (EC:1.6.5.3) was shared among Loktanella sp., Arcobacter. sp., Woeseia sp., and Tateyamaria sp. and it would be involved in metabolic pathways related to energy metabolism as “aerobic respiration I and II”, “Fe (II) oxidation”, “NAD(P)/NADPH interconversion”, and “NADH to cytochrome bd oxidase electron-electron transfer I”. Otherwise, Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase, enoyl-CoA hydratase and medium-chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC:2.3.1.9, EC:4.2.1.17 and EC:1.3.8.7) were three exclusive enzymes detected in Halioglobus sp. These enzymes were predicted to be involved in metabolic pathways related to biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and several routes related to biological processes, carbon biogeochemical cycle, energy metabolism and amino and nucleic acid metabolism.

4 Discussion

The microbiome significantly influences the health status and biological activity of most organisms. Large-scale ribosomal amplicon sequencing has become a widely used tool for analyzing and classifying the microbial communities associated with aquaculture-relevant bivalves (Pierce and Ward, 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020; Offret et al., 2020; Neu et al., 2021; Muñoz-Colmenero et al., 2024). In this study, we present a comprehensive prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbiome description of mussels, clams and cockles from a shared environment in Ría of Vigo. This multi-year study used high-throughput sequencing of the 18S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes.

The eukaryotic and prokaryotic microbiome was host-specific and not clearly affected by temporal or seasonal variations. We hypothesized that the three bivalves harbor specific microorganisms that remain relatively stable across seasons despite sharing the same ecosystem. This suggest that microbiome of these bivalves is shaped primarily by intrinsic host factors rather than external microbial availability. Although this pattern has already been reported in similar systems (Vezzulli et al., 2018; Akter et al., 2023; Ben Cheikh et al., 2024) our results confirm its consistency in the studied bivalves. Still, ecological differences may also contribute to microbial patterns (Gignoux-Wolfsohn et al., 2024), since C. edule and R. philippinarum, as benthic species, would be expected to have similar patterns, while the epibenthic M. galloprovincialis, would show a distinct pattern. Despite this, the low number of shared OTUs among bivalves (even between clams and cockles) indicated that habitat influence does not explain the observed microbiome differences.

The analysis of eukaryote communities showed the presence of several parasites as part of the microbiome in all three bivalve species. In Mytilus galloprovincialis, the eukaryotic microbiota was dominated by arthropods, particularly by the presence of the cyclopoid copepod Mytilicola intestinalis, known as a common parasite of the mussel (Gresty, 1992). Our results were consistent with several studies that have reported its presence in mussels (Andreu, 1963, Andreu, 1965; Figueras and Figueras, 1981; Paul, 1983; Trotti et al., 1998; Francisco et al., 2010; Yılmaz et al., 2020). M. intestinalis abundance remained high throughout the years (Davey, 1989; Robledo et al., 1994b, Robledo et al., 1994c; Mouritsen and Poulin, 2002), and the health of M. galloprovincialis did not appear to be adversely affected (Davey, 1989; Robledo et al., 1994c).

On the other hand, platyhelminth trematodes such as Neohexangritrema zebrasomatis, Intromugil mugilicolus and Bucephalus minimus dominated the eukaryotic microbiota of C. edule across years, consistent with observations in other studies (Deltreil and His, 1970; Lauckner, 1984; De Montaudouin et al., 2000; Desclaux et al., 2002; Thieltges and Reise, 2006). Some detected species belong to the digenetic trematode group, which are among the most common metazoan parasites infecting bivalves (Lamine et al., 2023). Given that, cockles are primary and secondary hosts (Longshaw and Malham, 2013), and their presence is not uncommon (Magalhães et al., 2015). Their detection is significant since some of them have been associated with mortality events, growth reduction or decreased fecundity (Longshaw and Malham, 2013).

Other bivalve parasites were also detected, although in very low numbers, such as Minchinia mercenaria in cockles or Perkinsus olseni in all the three bivalves. Therefore, bivalves host several protistan parasites, whose impact on the host health is unknown and clearly determined by environmental or physiological stress (Paillard et al., 2022).

Most eukaryotic parasites identified in bivalves were also found in the surrounding environments (water, sediment or both). This observation must be carefully considered in marine ecosystem management, as bivalves are constantly exposed to these potentially pathogenic parasites, and shifts in environmental conditions could disrupt the ecosystem balance. In particular, the detection of Perkinsus olseni may cause mortalities in clams (Villalba et al., 2004), Marteilia cochilia and Minchinia mercenaria may cause mortalities in cockles (Carrasco et al., 2013; Villalba et al., 2014; Carballal et al., 2016) and Bonamia ostreae in oysters (Engelsma et al., 2014; Ramilo et al., 2014). Importantly, parasites and pathogens can also influence the composition of the host-associated microbiome, as reported in previous studies (Zannella et al., 2017; Bass and Del Campo, 2020; Paillard et al., 2022; Gignoux-Wolfsohn et al., 2024). This interaction is important, because shifts in parasite prevalence could alter microbial community structure.

It is worth noting that histological confirmation was possible only for parasites whose identity could be established with certainty at the species level. In many bivalve samples, although unequivocal species identification was not possible, histological sections frequently revealed trematode metacercariae and turbellarians. These observations underscore both the complementarity and the limitations of histology relative to molecular approaches, highlighting the complexity of parasite detection in bivalves. Moreover, histology is inherently constrained by the possibility that parasites may not be present in the specific tissue section examined, or may be present in developmental stages that remain unrecognized under light microscopy.

Regarding bacterial communities, the gammaproteobacterial genus Endozoicomonas was one of the most abundant bacteria detected across all three bivalves. These results are consistent with previous studies, including mollusks and other marine invertebrates (Neave et al., 2016; Schill et al., 2017; Howells et al., 2021). Bacteria within this widely distributed genus have diverse proposed functions, ranging from beneficial symbionts crucial for optimal host functioning to potentially lethal pathogens (Neave et al., 2016). This is particularly relevant to our observation, since the widespread detection of Endozoicomonas in all three bivalves suggest a symbiotic involvement in processes such as digestion or immune modulation, consistent with its documented associations in other marine species (Schill et al., 2017). However, the presence of Endozoicomonas does not always imply a beneficial symbiotic relationship (Cano et al., 2018). Its detection in both healthy and diseased individuals in other studies (Bennion et al., 2021; Howells et al., 2021) suggests a context-dependent dual role. Therefore, monitoring these potentially pathogenic species provides valuable information for assessing the state of the ecosystem.

In a similar way, the genus Vibrio was detected in all three bivalve species, with particularly high abundance in cockles. This is relevant considering that many Vibrio species are important marine aquaculture pathogens capable of affecting bivalves at all life stages (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2010). Although our approach could not definitively identify specific pathogenic Vibrio strains, the genus presence may reflect either stable symbiotic associations or early indicators of potential pathogenicity. Beyond their pathogenic potential, several studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria can modulate host-associated microbial communities (Destoumieux-Garzón et al., 2020). This genus is often considered a regular component of the bivalve microbiome, establishing stable or transient associations with host tissues (Pruzzo et al., 2005; Destoumieux-Garzón et al., 2020). Abundant concentrations of Vibrio have been reported in Ría de Vigo, likely as a consequence of aquaculture activities (Huang et al., 2024). The manifestation of Vibrio-related diseases in bivalves depends on several factors, including environmental stressors (Zannella et al., 2017), host genetic background, developmental stage, co-infection by other pathogens (Destoumieux-Garzón et al., 2020), and immune response (Zhang et al., 2014; Rey-Campos et al., 2019). Lastly, it is worth noting that many Vibrio species are also pathogenic to humans and have been associated with food-borne diseases. Other human pathogenic bacteria, such as Enterobacter (Jantan et al., 2018) and Bacillus, were also found in our study. In particular, Bacillus cereus, which produces toxins associated with food poisoning (Venugopal and Gopakumar, 2017), was detected in cockles and mussels. The presence of these bacteria in bivalve mollusks (Grevskott et al., 2017) may indicate the release of fecal microorganisms from sewage near the sampling location, having serious implications for food safety.

The sea water and sediment harbored significantly higher bacterial diversity than bivalves (Whitman et al., 1998; Green and Keller, 2006; Fuhrman et al., 2015). Although host specificity was the primary factor shaping the microbiomes, the different ecological niches likely also contributed to some of the observed differences. Although clams and cockles did not exhibit a similar overlap with sediment-associated microbes, the subtle microbiome similarity between the two hosts might be attributed to their shared benthic infaunal environment. Correspondingly, mussels, which filter the water column might be expected to show greater overlap with water-associated microbes. Therefore, similar microbiomes in close habitats maybe reflect host-regulation by chemical and physical barriers (Bevins and Salzman, 2011; Nyholm and Graf, 2012; McFall-Ngai et al., 2013). In parallel, microbes have developed strategies to recognize and cope with some innate immune mechanisms conserved across metazoans, regulating the infections as well as the homeostasis of the host microbiome (Brennan and Gilmore, 2018). These selective processes may also depend on recognition mechanisms involving microbial- or host-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs/HAMPs) (Didierlaurent et al., 2002; Koropatnick et al., 2004; Niedergang et al., 2004).

Interactions such as competition, mutualism and parasitism among microorganisms can also contribute to the structure and function of bacterial communities (Faust and Raes, 2012; Dang and Lovell, 2016). These interactions, combined with complex biotic and abiotic factors, strongly influence microbial community assembly and dynamics (Liu et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2022). Our network analysis revealed significant co-occurrences and co-exclusions among the bacteria associated with each bivalve and its surrounding environment, indicating that ecosystem network patterns were robust and stable (Liang et al., 2024). The presence of both negative and positive correlations in nearly equal proportions suggests that both competitive and cooperative interactions played key roles in shaping bacterial communities (Zelezniak et al., 2015).

Keystone species play an important role in the structure and function of bacterial communities in the ecosystem through their extensive connections to other taxa (Hu et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2022). Vibrio emerged as key taxon within the mussel-water networks exerting significant influence on community structure despite not always being the most abundant genus. This finding contrast with previous studies linking its presence with negative health effects in clams (Dai et al., 2022, Dai et al., 2023). Otherwise, in benthic-associated networks, Woeseia sp. and Lutimonas sp. were identified as keystone species respectively. Both genera contribute to nutrient recycling in marine sediments (Mußmann et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2024). Although the role of Lutimonas in bivalves has not been directly studied, it has been associated with beneficial effects in shrimp (Duan et al., 2020), suggesting that its presence in cockles may be indicative of positive interactions. Additionally, Tenacibaculum sp. was also identified as key component of the clam microbiome. Some species within this genus are known to cause tenacibaculosis in fish (Avendaño-Herrera et al., 2006) and have been implicated in mortality events in Pacific oysters (Burioli et al., 2018). However, as previously mentioned, none of the animals in our study exhibited signs of compromised health status, as confirmed by histological examination.

Our results suggest that microbes can contribute to significant ecological innovations, providing hosts with a wide range of functional benefits (Ganesan et al., 2022). Notably, the keystone genus Halioglobus sp., was involved in metabolic pathways related to the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. These compounds, commonly produced by marine bacteria, are known for their bioactive properties such as antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal or antitumoral activity (Valliappan et al., 2014; Andryukov et al., 2019). This suggests a functional role for Halioglobus in mediating microbial competition or host defense within the sediment microenvironment. Several ecological models demonstrate that sessile invertebrates benefit from microbial metabolites to dissuade predators and outcompete pathogens (Rizzo and Lo Giudice, 2018). The relationship between bivalves and their microbiota likely extends beyond simple coexistence, potentially playing essential roles in host physiology, nutrition, reproduction, immune defense, and overall homeostasis (Chaston and Goodrich-Blair, 2010). However, further studies are necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of all these complex interactions, including improved detection and identification techniques for better classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities.

In summary, this multi-year metabarcoding study, based on the sequencing of 18S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes, provided a solid description of eukaryotic and prokaryotic microbiota of mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), clams (Ruditapes philippinarum), and cockles (Cerastoderma edule) from the Ría de Vigo. Despite inhabiting the same geographical area, each bivalve species harbored unique prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities, underscoring the dominant role of intrinsic host factors in shaping microbiome composition. Eukaryotic analyses identified prevalent parasites and potential pathogens, such as Mytilicola intestinalis in mussels, trematodes in cockles, and Perkinsus olseni across all three bivalves. The impact of these parasites and pathogens may vary depending on host susceptibility and environmental context. The bivalve microbiomes were distinct from those of surrounding water and sediment, suggesting selective host mechanisms maintain core microbial assemblages overriding direct environmental exposure. Prokaryotic communities were structured by host-specific taxa, including keystone genera such as Vibrio, Woeseia, and Lutimonas, which appear to influence microbial dynamics through both competitive and cooperative relationships. Functional predictions indicated potential mutualistic roles for key bacteria, particularly in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites that may support host health. Altogether, these findings establish a valuable ecological and molecular baseline for future biomonitoring, and highlight the relevance of host-microbe interactions in sustaining bivalve health and ecosystem resilience.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study can be found in the SRA-NCBI database with the following BioProject numbers: PRJNA1083288 and PRJNA1082107.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because animals are invertebrates.

Author contributions

MM-M: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR-C: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RA: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RR-C: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Our research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2021-124955OB-I00), Xunta de Galicia (IN607B 2022/13), and VIVALDI Project (678589) (EU H2020). The predoctoral contract of M.M-M (PRE2022-102115) was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and the European Social Fund (ESF). We acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative (PROA) through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

Acknowledgments

We thank the IIM aquarium staff for their technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors BN and AF declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2026.1731630/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Akter S. Wos-Oxley M. L. Catalano S. R. Hassan M. M. Li X. Qin J. G. et al . (2023). Host species and environment shape the gut microbiota of cohabiting marine bivalves. Microb. Ecol.86, 1755–1772. doi: 10.1007/s00248-023-02192-z

2

Amaral-Zettler L. A. McCliment E. A. Ducklow H. W. Huse S. M. (2009a). A method for studying protistan diversity using massively parallel sequencing of V9 hypervariable regions of small-subunit ribosomal RNA genes. PloS One4, e6372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006372

3

Amaral-Zettler L. A. McCliment E. A. Ducklow H. W. Huse S. M. (2009b). Correction: A method for studying protistan diversity using massively parallel sequencing of V9 hypervariable regions of small-subunit ribosomal RNA genes. PloS One4. doi: 10.1371/annotation/50c43133-0df5-4b8b-8975-8cc37d4f2f26

4

Andreu B. (1963). Propagación del copépodo parásito Mytilicola intestinalis en el mejillón cultivado de las rías gallegas (NW de España). Inv. Pesq.24, 3–20.

5

Andreu B. (1965). Biología y parasitología del mejillón gallego. Las. Cienc.30, 107–118.

6

Andryukov B. Mikhailov V. Besednova N. (2019). The biotechnological potential of secondary metabolites from marine bacteria. JMSE7, 176. doi: 10.3390/jmse7060176

7

Avendaño-Herrera R. Toranzo A. Magariños B. (2006). Tenacibaculosis infection in marine fish caused by Tenacibaculum maritimum: a review. Dis. Aquat. Org.71, 255–266. doi: 10.3354/dao071255

8

Bass D. Del Campo J. (2020). Microeukaryotes in animal and plant microbiomes: Ecologies of disease? Eur. J. Protistol.76, 125719. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2020.125719

9

Beaz-Hidalgo R. Balboa S. Romalde J. L. Figueras M. J. (2010). Diversity and pathogenecity of Vibrio species in cultured bivalve molluscs. Environ. Microbiol. Rep.2, 34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00135.x

10

Ben Cheikh Y. Massol F. Giusti-Petrucciani N. Travers M.-A. (2024). Impact of epizootics on mussel farms: Insights into microbiota composition of Mytilus species. Microbiol. Res.280, 127593. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2023.127593

11

Bennion M. Ross P. Howells J. McDonald I. Lane H. (2021). Characterisation and distribution of the bacterial genus Endozoicomonas in a threatened surf clam. Dis. Aquat. Org.146, 91–105. doi: 10.3354/dao03626

12

Bevins C. L. Salzman N. H. (2011). The potter’s wheel: the host’s role in sculpting its microbiota. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.68, 3675–3685. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0830-3

13

Blondel V. D. Guillaume J.-L. Lambiotte R. Lefebvre E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech.2008, P10008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

14

Bower S. M. Carnegie R. B. Goh B. Jones S. R. M. Lowe G. J. Mak M. W. S. (2004). Preferential PCR amplification of parasitic protistan small subunit rDNA from metazoan tissues. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.51, 325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00574.x

15

Brandes U. (2001). A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality*. J. Math. Sociol.25, 163–177. doi: 10.1080/0022250X.2001.9990249

16

Brennan J. J. Gilmore T. D. (2018). Evolutionary origins of toll-like receptor signaling. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 1576–1587. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy050

17

Brisson V. Schmidt J. Northen T. R. Vogel J. P. Gaudin A. (2019). A new method to correct for habitat filtering in microbial correlation networks. Front. Microbiol.10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00585

18

Burioli E. A. V. Varello K. Trancart S. Bozzetta E. Gorla A. Prearo M. et al . (2018). First description of a mortality event in adult Pacific oysters in Italy associated with infection by a Tenacibaculum soleae strain. J. Fish. Dis.41, 215–221. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12698

19

Cano I. Van Aerle R. Ross S. Verner-Jeffreys D. W. Paley R. K. Rimmer G. S. E. et al . (2018). Molecular characterization of an endozoicomonas-like organism causing infection in the king scallop (Pecten maximus L.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol.84, e00952–e00917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00952-17

20

Carballal M. Iglesias D. Darriba S. Cao A. Mariño J. Ramilo A. et al . (2016). Parasites, pathological conditions and resistance to Marteilia cochillia in lagoon cockle Cerastoderma glaucum from Galicia (NW Spain). Dis. Aquat. Org.122, 137–152. doi: 10.3354/dao03070

21

Carnegie R. Meyer G. Blackbourn J. Cochennec-Laureau N. Berthe F. Bower S. (2003). Molecular detection of the oyster parasite Mikrocytos mackini, and a preliminary phylogenetic analysis. Dis. Aquat. Org.54, 219–227. doi: 10.3354/dao054219

22

Carrasco N. Hine P. M. Durfort M. Andree K. B. Malchus N. Lacuesta B. et al . (2013). Marteilia cochillia sp. nov., a new Marteilia species affecting the edible cockle Cerastoderma edule in European waters. Aquaculture, 412–413223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.07.027

23

Chaston J. Goodrich-Blair H. (2010). Common trends in mutualism revealed by model associations between invertebrates and bacteria: Table 1. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.34, 41–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00193.x

24

Dai W. Dong Y. Ye J. Xue Q. Lin Z. (2022). Gut microbiome composition likely affects the growth of razor clam Sinonovacula constricta. Aquaculture550, 737847. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737847

25

Dai W. Zhang Z. Dong Y. He L. Xue Q. Lin Z. (2023). Acute salinity stress disrupts gut microbiota homeostasis and reduces network connectivity and cooperation in razor clam sinonovacula constricta. Mar. Biotechnol.25, 1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s10126-023-10267-8

26

Dang H. Lovell C. R. (2016). Microbial surface colonization and biofilm development in marine environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.80, 91–138. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00037-15

27

Davey J. T. (1989). Mytilicola intestinalis (Copepoda: cyclopoida): A ten year survey of infested mussels in a cornish estuary 1978–1988. J. Mar. Biol. Ass.69, 823–836. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400032197

28

Deltreil J. P. His E. (1970). On the presence of a trematoda cercaria in Cardium edule I. in the Arcachon basin. Rev. Des. Trav. l’Inst. Des. Pêch. Marit.34, 225–232.

29

De Montaudouin X. Kisielewski I. Bachelet G. Desclaux C. (2000). A census of macroparasites in an intertidal bivalve community, Arcachon Bay, France. Oceanol. Acta23, 453–468. doi: 10.1016/S0399-1784(00)00138-9

30

Desclaux C. De Montaudouin X. Bachelet G. (2002). Cockle emergence at the sediment surface: “favourization” mechanism by digenean parasites? Dis. Aquat. Org.52, 137–149. doi: 10.3354/dao052137

31

Destoumieux-Garzón D. Canesi L. Oyanedel D. Travers M. Charrière G. M. Pruzzo C. et al . (2020). Vibrio –bivalve interactions in health and disease. Environ. Microbiol.22, 4323–4341. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15055

32

Didierlaurent A. Sirard J.-C. Kraehenbuhl J.-P. Neutra M. R. (2002). How the gut senses its content. Cell Microbiol.4, 61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00177.x

33

Diwan A. Harke S. N. Panche A. (Eds.) (2023). Microbiome of finfish and shellfish (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore). doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-0852-3

34

Duan Y. Wang Y. Ding X. Xiong D. Zhang J. (2020). Response of intestine microbiota, digestion, and immunity in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei to dietary succinate. Aquaculture517, 734762. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734762

35

Elston R. A. Ford S. E. (2011). “ Shellfish diseases and health management,” in Shellfish aquaculture and the environment. Ed. ShumwayS. E. (Oxford: Wiley), 359–394. doi: 10.1002/9780470960967.ch13

36

Faust K. Raes J. (2012). Microbial interactions: from networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.10, 538–550. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2832

37

Figueras M. A. Figueras H. A. (1981). Myticola intestinalis Steuer, in cultivated mussels in the Ria of Vigo. Invest. Pesq.45, 263–278.

38

Francisco C. J. Hermida M. A. Santos M. J. (2010). Parasites and symbionts from mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamark 1819) (Bivalves: mytilidae) of the aveiro estuary Portugal. J. Parasitol.96, 200–205. doi: 10.1645/GE-2064.1

39

Fuhrman J. A. Cram J. A. Needham D. M. (2015). Marine microbial community dynamics and their ecological interpretation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.13, 133–146. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3417

40

Ganesan R. Wierz J. C. Kaltenpoth M. Flórez L. V. (2022). How it all begins: bacterial factors mediating the colonization of invertebrate hosts by beneficial symbionts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.86, e00126–e00121. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00126-21

41

Gignoux-Wolfsohn S. Garcia Ruiz M. Portugal Barron D. Ruiz G. Lohan K. (2024). Bivalve microbiomes are shaped by host species, size, parasite infection, and environment. PeerJ12, e18082. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18082

42

Granek E. F. Brumbaugh D. R. Heppell S. A. Heppell S. S. Secord D. (2005). A blueprint for the oceans: implications of two national commission reports for conservation practitioners. Conserv. Biol.19, 1008–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00221.x

43

Green B. D. Keller M. (2006). Capturing the uncultivated majority. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.17, 236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.004

44

Gresty K. A. (1992). Ultrastructure of the midgut of the copepod mytilicola intestinalis steuer, an endoparasite of the mussel mytilus edulis L. J. Crustac. Biol.12, 169–177. doi: 10.2307/1549071

45

Grevskott D. H. Svanevik C. S. Sunde M. Wester A. L. Lunestad B. T. (2017). Marine bivalve mollusks as possible indicators of multidrug-resistant escherichia coli and other species of the enterobacteriaceae family. Front. Microbiol.8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00024

46

Hadziavdic K. Lekang K. Lanzen A. Jonassen I. Thompson E. M. Troedsson C. (2014). Characterization of the 18S rRNA gene for designing universal eukaryote specific primers. PloS One9, e87624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087624

47

Harvell C. D. Mitchell C. E. Ward J. R. Altizer S. Dobson A. P. Ostfeld R. S. et al . (2002). Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science296, 2158–2162. doi: 10.1126/science.1063699

48

Howard D. W. Lewis E. J. Keller B. J. Smith C. S. (2004). Histological techniques for marine bivalve mollusks (Oxford, MD: NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

49

Howells J. Jaramillo D. Brosnahan C. Pande A. Lane H. (2021). Intracellular bacteria in New Zealand shellfish are identified as Endozoicomonas species. Dis. Aquat. Org.143, 27–37. doi: 10.3354/dao03547

50

Hu X. Gu H. Wang Y. Liu J. Yu Z. Li Y. et al . (2022). Succession of soil bacterial communities and network patterns in response to conventional and biodegradable microplastics: A microcosmic study in Mollisol. J. Hazard. Mater.436, 129218. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129218

51

Huang X. Huang K. Chen S. Yin X. Pérez-Lorenzo M. Teira E. et al . (2024). A diverse vibrio community in ría de vigo (Northwestern Spain). Biology13, 986. doi: 10.3390/biology13120986

52

Hugerth L. W. Muller E. E. L. Hu Y. O. O. Lebrun L. A. M. Roume H. Lundin D. et al . (2014). Systematic design of 18S rRNA gene primers for determining eukaryotic diversity in microbial consortia. PloS One9, e95567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095567

53

Jantan N. S. Zakaria Z. Aziz S. A. Matori F. (2018). “ Occurrence of pathogenic bacteria in blood cockles, anadara granosa,” in Proceedings of the 7th international conference on multidisciplinary research ( SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia), 268–272. doi: 10.5220/0008888602680272

54

Koropatnick T. A. Engle J. T. Apicella M. A. Stabb E. V. Goldman W. E. McFall-Ngai M. J. (2004). Microbial factor-mediated development in a host-bacterial mutualism. Science306, 1186–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1102218

55

Lamine I. Chahouri A. Moukrim A. Ait Alla A. (2023). The impact of climate change and pollution on trematode-bivalve dynamics. Mar. Environ. Res.191, 106130. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2023.106130

56

Lasa A. Di Cesare A. Tassistro G. Borello A. Gualdi S. Furones D. et al . (2019). Dynamics of the Pacific oyster pathobiota during mortality episodes in Europe assessed by 16S rRNA gene profiling and a new target enrichment next-generation sequencing strategy. Environ. Microbiol.21, 4548–4562. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14750

57

Lauckner G. (1984). Impact of trematode parasitism on the fauna of a North Sea tidal flat. Helgol. Meeresunters.37, 185–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01989303

58

Leray M. Agudelo N. Mills S. C. Meyer C. P. (2013). Effectiveness of annealing blocking primers versus restriction enzymes for characterization of generalist diets: unexpected prey revealed in the gut contents of two coral reef fish species. PloS One8, e58076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058076

59

Liang H. Huang J. Xia Y. Yang Y. Yu Y. Zhou K. et al . (2024). Spatial distribution and assembly processes of bacterial communities in riverine and coastal ecosystems of a rapidly urbanizing megacity in China. Sci. Tot. Environ.934, 173298. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173298

60

Liu Q. Zhao Q. Jiang Y. Li Y. Zhang C. Li X. et al . (2021). Diversity and co-occurrence networks of picoeukaryotes as a tool for indicating underlying environmental heterogeneity in the Western Pacific Ocean. Mar. Environ. Res.170, 105376. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2021.105376

61

Longshaw M. Malham S. K. (2013). A review of the infectious agents, parasites, pathogens and commensals of European cockles ( Cerastoderma edule and C. glaucum). J. Mar. Biol. Ass.93, 227–247. doi: 10.1017/S0025315412000537

62

Lu L. Tang Q. Li H. Li Z. (2022). Damming river shapes distinct patterns and processes of planktonic bacterial and microeukaryotic communities. Environ. Microbiol.24, 1760–1774. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15872

63

Magalhães L. Freitas R. De Montaudouin X. (2015). Review: Bucephalus minimus, a deleterious trematode parasite of cockles Cerastoderma spp. Parasitol. Res.114, 1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4374-6

64

Mayer T. Mari A. Almario J. Murillo-Roos M. Syed M. Abdullah H. Dombrowski N. et al . (2021). Obtaining deeper insights into microbiome diversity using a simple method to block host and nontargets in amplicon sequencing. Mol. Ecol. Resour.21, 1952–1965. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13408

65

McFall-Ngai M. Hadfield M. G. Bosch T. C. G. Carey H. V. Domazet-Lošo T. Douglas A. E. et al . (2013). Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.110, 3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110

66

Minardi D. Ryder D. Del Campo J. Garcia Fonseca V. Kerr R. Mortensen S. et al . (2022). Improved high throughput protocol for targeting eukaryotic symbionts in metazoan and eDNA samples. Mol. Ecol. Resour.22, 664–678. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13509

67

Mouritsen K. N. Poulin R. (2002). Parasitism, community structure and biodiversity in intertidal ecosystems. Parasitology124, 101–117. doi: 10.1017/S0031182002001476

68

Mußmann M. Pjevac P. Krüger K. Dyksma S. (2017). Genomic repertoire of the Woeseiaceae /JTB255, cosmopolitan and abundant core members of microbial communities in marine sediments. ISME. J.11, 1276–1281. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.185

69

Muñoz-Colmenero M. Lee R.-S. Velasco A. Ramilo-Fernández G. Longa Á. Sotelo C. G. (2024). New metagenomic procedure for the investigation of the eukaryotes present in the digestive gland of Mytillus galloprovincialis. Aquac. Rep.36, 102031. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102031

70

Neave M. J. Apprill A. Ferrier-Pagès C. Voolstra C. R. (2016). Diversity and function of prevalent symbiotic marine bacteria in the genus Endozoicomonas. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.100, 8315–8324. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7777-0

71

Neu A. T. Hughes I. V. Allen E. E. Roy K. (2021). Decade-scale stability and change in a marine bivalve microbiome. Mol. Ecol.30, 1237–1250. doi: 10.1111/mec.15796

72

Nguyen V. K. King W. L. Siboni N. Mahbub K. R. Dove M. O’Connor W. et al . (2020). The Sydney rock oyster microbiota is influenced by location, season and genetics. Aquaculture527, 735472. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735472

73

Niedergang F. Didierlaurent A. Kraehenbuhl J.-P. Sirard J.-C. (2004). Dendritic cells: the host Achille’s heel for mucosal pathogens? Trends Microbiol.12, 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.011

74

Nyholm S. V. Graf J. (2012). Knowing your friends: invertebrate innate immunity fosters beneficial bacterial symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.10, 815–827. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2894

75

Offret C. Paulino S. Gauthier O. Château K. Bidault A. Corporeau C. et al . (2020). The marine intertidal zone shapes oyster and clam digestive bacterial microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.96, fiaa078. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa078

76

Paillard C. Gueguen Y. Wegner K. M. Bass D. Pallavicini A. Vezzulli L. et al . (2022). Recent advances in bivalve-microbiota interactions for disease prevention in aquaculture. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.73, 225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.07.026

77

Panek F. M. (2005). Epizootics and disease of coral reef fish in the tropical western atlantic and gulf of Mexico. Rev. Fish. Sci.13, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/10641260590885852

78

Paul J. D. (1983). The incidence and effects of Mytilicola intestinalis in Mytilus edulis from the Rías of Galicia, North West Spain. Aquaculture31, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(83)90252-1

79

Pierce M. L. Ward J. E. (2018). Microbial ecology of the bivalvia, with an emphasis on the family ostreidae. J. Shellfish. Res.37, 793–806. doi: 10.2983/035.037.0410

80

Popovic A. Parkinson J. (2018). “ Characterization of eukaryotic microbiome using 18S amplicon sequencing,” in Microbiome analysis. Eds. BeikoR. G.HsiaoW.ParkinsonJ. ( Springer New York, New York, NY), 29–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8728-3_3

81

Pruzzo C. Gallo G. Canesi L. (2005). Persistence of vibrios in marine bivalves: the role of interactions with haemolymph components. Environ. Microbiol.7, 761–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00792.x

82

Ramilo A. González M. Carballal M. Darriba S. Abollo E. Villalba A. (2014). Oyster parasites Bonamia ostreae and B. exitiosa co-occur in Galicia (NW Spain): spatial distribution and infection dynamics. Dis. Aquat. Org.110, 123–133. doi: 10.3354/dao02673

83

Rey-Campos M. Moreira R. Gerdol M. Pallavicini A. Novoa B. Figueras A. (2019). Immune Tolerance in Mytilus galloprovincialis Hemocytes After Repeated Contact With Vibrio splendidus. Front. Immunol.10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01894

84

Ríos-Castro R. Costas-Selas C. Pallavicini A. Vezzulli L. Novoa B. Teira E. et al . (2022). Co-occurrence and diversity patterns of benthonic and planktonic communities in a shallow marine ecosystem. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.934976

85

Ríos-Castro R. Romero A. Aranguren R. Pallavicini A. Banchi E. Novoa B. et al . (2021). High-throughput sequencing of environmental DNA as a tool for monitoring eukaryotic communities and potential pathogens in a coastal upwelling ecosystem. Front. Vet. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.765606

86

Rizzo C. Lo Giudice A. (2018). Marine invertebrates: underexplored sources of bacteria producing biologically active molecules. Diversity10, 52. doi: 10.3390/d10030052

87

Robledo J. A. F. Caceres-Martinez J. Figueras A. (1994a). Marteilia refringens in mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis Lmk.) beds in Spain. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish. Pathol.14, 61–63.

88

Robledo J. A. F. Caceres-Martinez J. Figueras A. (1994b). Mytilicola intestinalis and Proctoeces maculatus in mussel (Mytilis galloprovincialis Lmk.) beds in Spain. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish. Pathol.14, 89–95.

89

Robledo J. A. F. Santarém M. M. Figueras A. (1994c). Parasite loads of rafted blue mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) in Spain with special reference to the copepod, Mytilicola intestinalis. Aquaculture127, 287–302. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(94)90232-1

90

Robledo J. A. F. Yadavalli R. Allam B. Espinosa E. P. Gerdol M. Greco S. et al . (2019). From the raw bar to the bench: Bivalves as models for human health. Dev. Comp. Immunol.92, 260–282. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2018.11.020

91

Santibáñez P. Romalde J. Maldonado J. Fuentes D. Figueroa J. (2022). First characterization of the gut microbiome associated with Mytilus Chilensis collected at a mussel farm and from a natural environment in Chile. Aquaculture548, 737644. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737644

92

Schill W. B. Iwanowicz D. Adams C. (2017). Endozoicomonas dominates the gill and intestinal content microbiomes of mytilus edulis from barnegat bay, new Jersey. J. Shellfish. Res.36, 391–401. doi: 10.2983/035.036.0212

93

Shaw B. L. Battle H. I. (1957). The gross and Microscopic Anatomy Of the Digestive tract uf the Oyster Crassostrea Virginica (Gmelin). Can. J. Zool.35, 325–347. doi: 10.1139/z57-026

94

FAO (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. Rome: FAO. doi: 10.4060/cd0683en

95

Thieltges D. W. Reise K. (2006). Metazoan parasites in intertidal cockles Cerastoderma edule from the northern Wadden Sea. J. Sea. Res.56, 284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2006.06.002

96

Trotti G. C. Baccarani E. Giannetto S. Giuffrida A. Paesanti F. (1998). Prevalence of Mytilicola intestinalis (Copepoda : Mytilicolidae) and Urastoma cyprinae (Turbellaria : Hypotrichinidae) in marketable mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis in Italy. Dis. Aquat. Org.32, 145–149. doi: 10.3354/dao032145

97

Valliappan K. Sun W. Li Z. (2014). Marine actinobacteria associated with marine organisms and their potentials in producing pharmaceutical natural products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.98, 7365–7377. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5954-6

98

Venugopal V. Gopakumar K. (2017). Shellfish: nutritive value, health benefits, and consumer safety. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe.16, 1219–1242. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12312

99

Vestheim H. Jarman S. N. (2008). Blocking primers to enhance PCR amplification of rare sequences in mixed samples – a case study on prey DNA in Antarctic krill stomachs. Front. Zool.5, 12. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-5-12

100

Vezzulli L. Stagnaro L. Grande C. Tassistro G. Canesi L. Pruzzo C. (2018). Comparative 16SrDNA Gene-Based Microbiota Profiles of the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and the Mediterranean Mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) from a Shellfish Farm (Ligurian Sea, Italy). Microb. Ecol.75, 495–504. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1051-6

101

Villalba A. Iglesias D. Ramilo A. Darriba S. Parada J. No E. et al . (2014). Cockle Cerastoderma edule fishery collapse in the Ría de Arousa (Galicia, NW Spain) associated with the protistan parasite Marteilia cochillia. Dis. Aquat. Org.109, 55–80. doi: 10.3354/dao02723

102

Villalba A. Mourelle S. Carballal M. López C. (1997). Symbionts and diseases of farmed mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis throughout the culture process in the Rías of Galicia (NW Spain). Dis. Aquat. Org.31, 127–139. doi: 10.3354/dao031127

103

Villalba A. Reece K. S. Camino Ordás M. Casas S. M. Figueras A. (2004). Perkinsosis in molluscs: A review. Aquat. Liv. Resour.17, 411–432. doi: 10.1051/alr:2004050

104

Whitman W. B. Coleman D. C. Wiebe W. J. (1998). Prokaryotes: The unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.95, 6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578

105

Yılmaz H. Genç E. Ünal Mine E. Yıldırım Ş. Keskin E. (2020). Molecular identification of parasites isolated from Mediterranean Mussel (Mytilus Galloprovincialis Lamarck 1819) specimens. NWSA15, 61–71. doi: 10.12739/NWSA.2020.15.2.5A0133

106

Yu X. Li X. Liu Q. Yang M. Wang X. Guan Z. et al . (2022). Community assembly and co-occurrence network complexity of pelagic ciliates in response to environmental heterogeneity affected by sea ice melting in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Sci. Tot. Environ.836, 155695. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155695

107

Zannella C. Mosca F. Mariani F. Franci G. Folliero V. Galdiero M. et al . (2017). Microbial diseases of bivalve mollusks: infections, immunology and antimicrobial defense. Mar. Drugs15, 182. doi: 10.3390/md15060182

108

Zelezniak A. Andrejev S. Ponomarova O. Mende D. R. Bork P. Patil K. R. (2015). Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 6449–6454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421834112

109

Zhang Y. Li T. Li G. Yuan T. Zhang Y. Jin L. (2024). Profiling sediment bacterial communities and the response to pattern-driven variations of total nitrogen and phosphorus in long-term polyculture ponds. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1403909

110

Zhang T. Qiu L. Sun Z. Wang L. Zhou Z. Liu R. et al . (2014). The specifically enhanced cellular immune responses in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) against secondary challenge with Vibrio splendidus. Dev. Comp. Immunol.45, 141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.02.015

Summary

Keywords

amplicon sequencing, bivalves, environmental health, marine microbiome, microbial dynamics

Citation

Muñoz-Martínez M, Rey-Campos M, Aranguren R, Ríos-Castro R, Novoa B and Figueras A (2026) Unveiling the specific microbiome of bivalves: insights into host microbial dynamics and pathogen interactions in a shared environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1731630. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1731630

Received

24 October 2025

Revised

16 December 2025

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

09 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Taewoo Ryu, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Japan

Reviewed by

Dimitrios Loukovitis, A.T.E.I.Th

Yosra Ben Cheikh, Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, Greece

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Muñoz-Martínez, Rey-Campos, Aranguren, Ríos-Castro, Novoa and Figueras.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beatriz Novoa, beatriznovoa@iim.csic.es; Antonio Figueras, antoniofigueras@iim.csic.es

Disclaimer