Abstract

Fermentation is a key biological process in which microorganisms convert carbon-rich substrates into smaller molecules (e.g., organic acids or ethanol) while generating metabolic energy. While extensively applied to terrestrial plant biomass, the fermentation of macroalgae remains relatively unexplored. The brown edible seaweed Himanthalia elongata is a rich source of bioactive compounds with health-promoting properties, making it a promising feedstock for the development of functional ingredients in nutraceutical applications. This review summarizes the biochemical composition of H. elongata and its associated biological activities, with consideration of its holobiont. Lactic acid fermentation is introduced in the context of brown seaweed substrates, together with analytical approaches and monitoring methods. The challenges of H. elongata bioconversion are discussed, including the limited accessibility of key biomolecules, the presence of potential inhibitors, and issues related to the complex seaweed matrix. The intrinsic richness and complexity of H. elongata biomass, along with the adaptive responses of lactic acid bacteria to brown seaweed substrates, present both obstacles and opportunities for fermentation. Optimizing biomass pretreatment, managing endogenous microbiota, and mitigating inhibitory compounds are critical to improve fermentation efficiency and product safety. Moreover, the biological activities of fermented extracts offer valuable prospects for the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals. Overall, this review underscores the need for further research to unlock the full potential of H. elongata as a substrate for lactic acid fermentation and to characterize the properties of the resulting bioproducts.

1 Introduction

Oceans support a wide array of aquatic plants, commonly known as algae. Seaweed, also known as macroalgae, are aquatic organisms capable of photosynthesis. Based on their pigmentation, macroalgae were conventionally classified in three main groups: Chlorophyta (green seaweed), Rhodophyta (red seaweed), and Phaeophyta (brown seaweed) (Makkar et al., 2016). Brown algae, primarily belonging to the orders Fucales and Laminariales, are characterized by notably high levels of phenolic compounds, which exceed those found in red and green algae (Ilyas et al., 2023). These compounds are associated with a range of bioactive properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-hypoglycemic effects, among others (Ilyas et al., 2023; Cofrades et al., 2010; Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2010; Belda-Antolí et al., 2017; Rajauria, 2019; Catarino et al., 2022). Himanthalia elongata, also known as sea spaghetti, belongs to the order Fucales, to the family Himanthaliaceae, and to the genus Himanthalia. Up to 3 meters in length, the algae is formed of fine filaments approximately 15 mm thick that branch in a dichotomous pattern. The body of the algae begins with a thallus resembling a button and its color varies from brown to yellowish-brown (White, 2008; Vila et al., 2022). It is found along the European Atlantic coasts from the Faroe Islands to Portugal and exhibits an intertidal distribution, forming linear bands along rocky shorelines (Casado-Amezúa et al., 2019). This cold-temperate seaweed can be classified as a canopy-forming alga, providing a sheltered microhabitat on rocky shores during low tide and exhibiting tolerance to both atmospheric and marine exposure (Martínez et al., 2015). Among brown seaweed, H. elongata stands out for its high phenolic content, which confers significant potential for applications in the health and nutraceutical sectors (Ilyas et al., 2023; Belda-Antolí et al., 2017; Catarino et al., 2022; Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2017; Santoyo et al., 2011; Cernadas et al., 2019; Flórez-Fernández et al., 2021; Gomes et al., 2022). H. elongata is considered to be safe for food consumption and is part of the European Union list of edible seaweed (Araújo and Peteiro, 2021).

In the context of sustainable development, new technologies and processing innovations are emerging and aimed at reducing the environmental impact of industry. Anastas and Warner (Anastas and Warner, 1998) established twelve principles of “green chemistry” to promote the development of eco-friendly chemical processes while simultaneously fostering innovation (Chen et al., 2020). These principles emphasize the use of green solvents, waste and energy reduction, and the utilization of renewable feedstocks. Some countries, for instance Sweden, have already introduced regulations to limit hazardous use of chemicals and to promote greener industry (Chen et al., 2020). In this context, the development of bioactive natural products is of increasing interest for biomaterial, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical applications (Joyce et al., 2021; Usman et al., 2023). Green extraction techniques include ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, enzymatic processes, supercritical fluid extraction, and microbial fermentation (Usman et al., 2023). Similarly, the use of green solvents is recommended, such as water, biobased solvents and naturel deep eutectic solvents (NaDES).

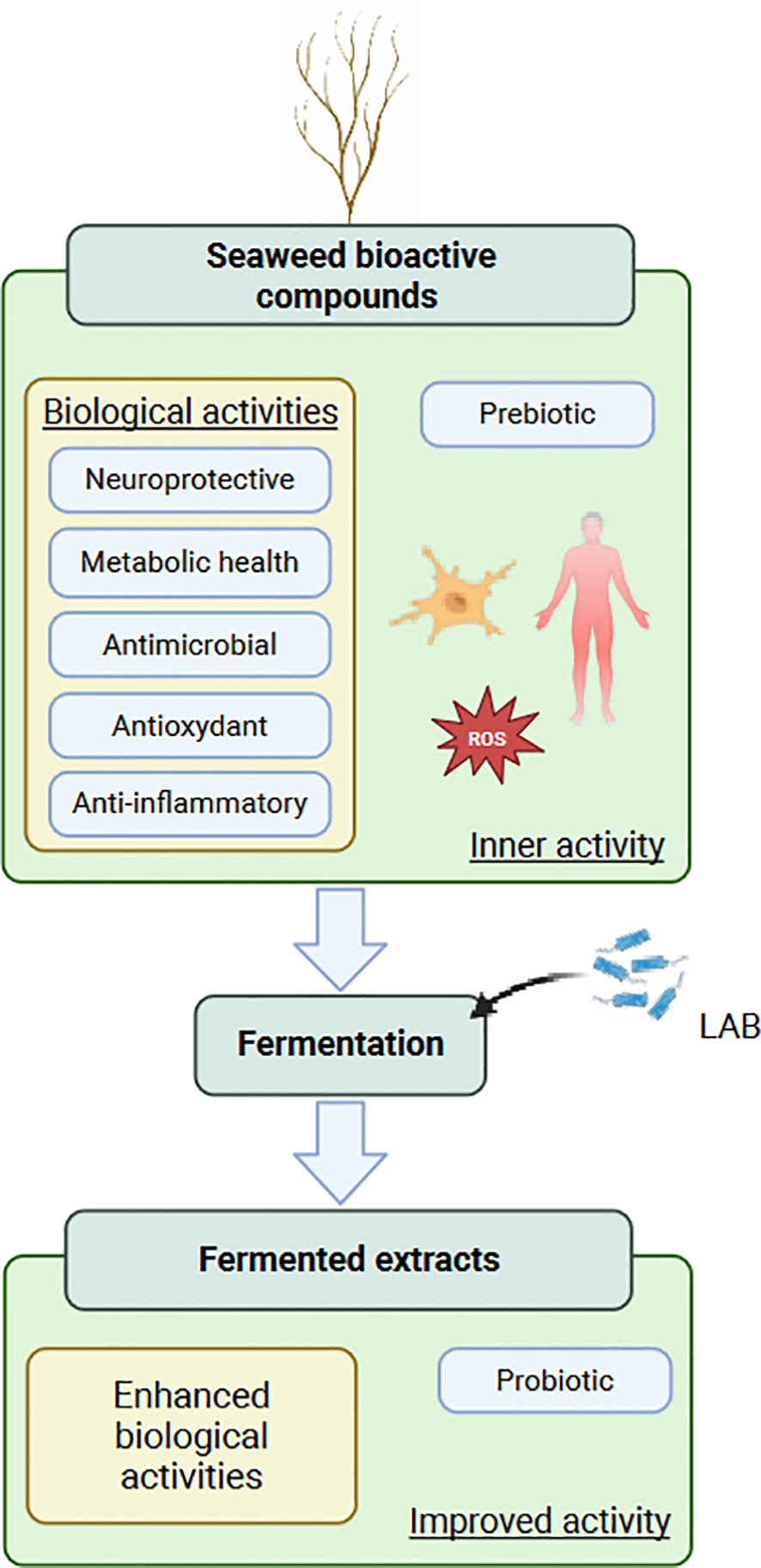

Fermentation refers to the microbial digestion of an energy-rich substrate and its subsequent conversion into organic molecules called metabolites (Shiferaw Terefe and Augustin, 2020). Traditionally used to prolong the shelf life of food and to make alcoholic beverages (Paul Ross et al., 2002), it today plays an increasingly important role in a variety of industries. Lactic acid fermentation is widely used in the dairy industry and is now recognized to enhance the bioactivity of fermented substrates by facilitating the release of bioactive molecules. Additionally, its use can enhance extraction by incorporating metabolites derived from bacterial metabolism, thereby increasing the functional value of the resulting extracts (Reboleira et al., 2021). Finally, Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) may also confer probiotic benefits. Fermentation is consequently an appropriate tool for the development of new extraction techniques and the obtention of new functional ingredients.

The biochemical and nutritional potential of the brown seaweed H. elongata represents a significant opportunity for the development of bioactive extracts through sustainable fermentation processes. While the use of seaweed as a fermentation substrate was reviewed (Monteiro et al., 2021; Reboleira et al., 2021), the specific relationship between the biochemical composition, exogenous lactic acid bacteria, seaweed microbiota, fermentation conditions, and substrate preparation applied to H. elongata remains unexplored. Therefore, this study examines the following research question: how can these interactions be optimized and used to produce bioactive extracts with the aim of promoting the economic value of this species for applications in the field of health. Particular emphasis of this review was placed on integrating current knowledge of the substrate’s composition and bioactivity in a first section. The second part describes lactic acid fermentation including the microorganisms, metabolism and technical parameters. In the last section, the challenges and limits of the fermentation process applied to H. elongata and biomass upstreaming pretreatment are discussed while considering the factors that may interact during bioconversion.

To the best of our knowledge, this perspective has not yet been comprehensively addressed in the literature, offering a novel framework for exploring the fermentation potential of understudied resource.

2 Overview of Himanthalia elongata substrate

Brown seaweed (Phaeophyceae) are recognized for their remarkable diversity of bioactive compounds. Their polysaccharide composition, along with that of complex secondary metabolites such as phlorotannins and carotenoids, contribute to their high biotechnological potential. For fermentation applications, a comprehensive understanding of the nature, quantity, and bio-accessibility of sugar-based fermentable compounds as well as of other high value biochemicals is essential to evaluate the suitability of the substrate and to optimize microbial conversion processes.

2.1 Seaweed polysaccharides and sugars

2.1.1 Cell wall

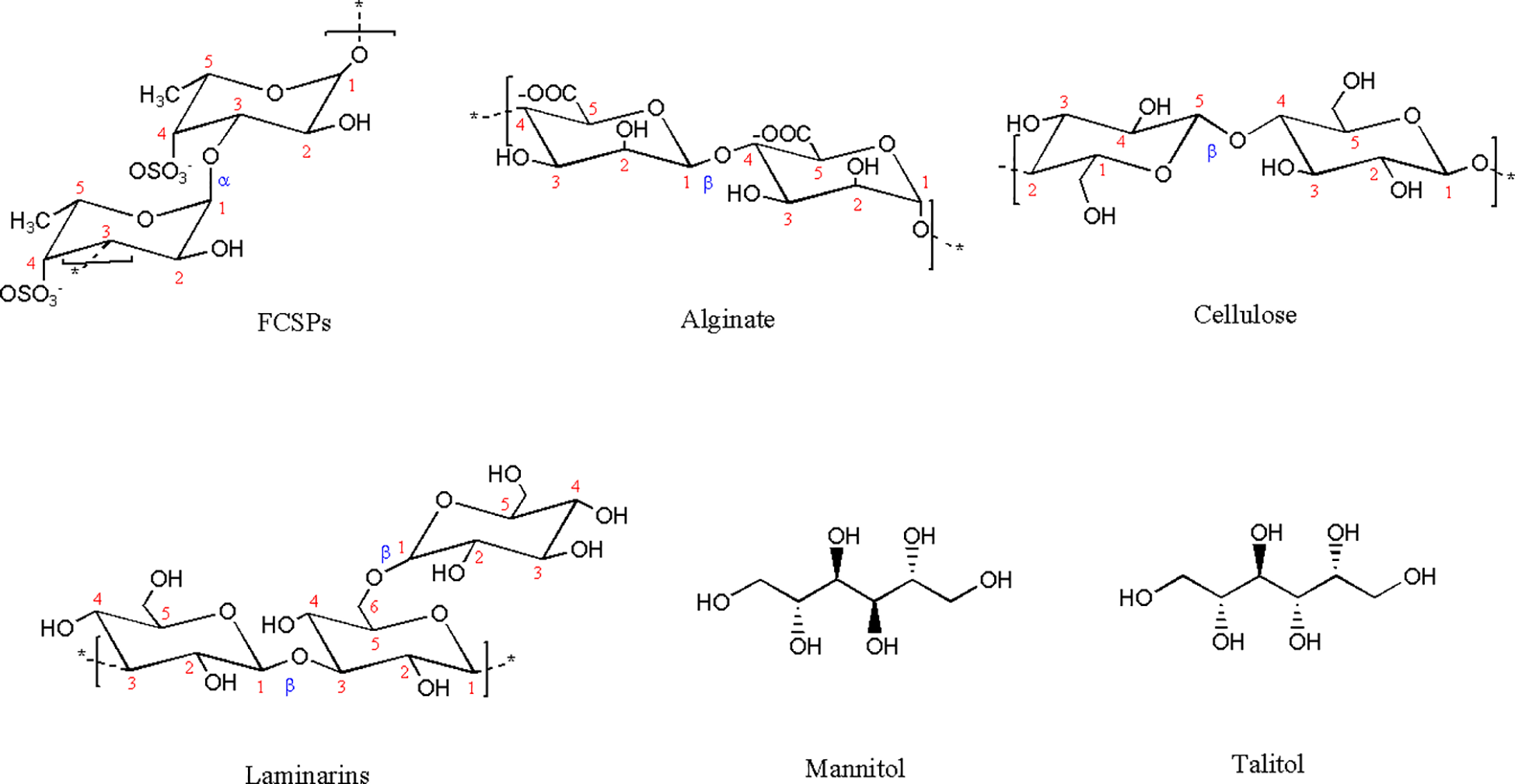

The composition and structure of the brown seaweed cell wall have been studied in the last 20 years due to its uniqueness (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2017). Three main groups of cell wall polysaccharides have been described in brown macroalgae. Figure 1 shows the chemical structures of the polysaccharides and polyols.

Figure 1

Structures of the polysaccharides and storage sugars found in Himanthalia elongata.

2.1.1.1 Alginates

Alginate is the most abundant polysaccharide found in the Phaeophyceae group, accounting for up to 45% of the cell wall, and is composed of two main monomers: β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G), linked by β-(1→4) glycosidic bonds (Figure 1) (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014; Pereira and Cotas, 2020). Notably, alginate is unique among marine polysaccharides due to the presence of carboxyl groups on its monomers, making it an anionic polymer (Xing et al., 2020; Baghel et al., 2021; Abka-khajouei et al., 2022). Subcritical water extraction performed in a pressurized reactor at temperatures up to 160°C, followed by acetone fractionation of the resulting liquid extract to precipitate alginates, enabled a detailed characterization of the alginate. Extraction yields ranged from 5.9% to 15.9% of dry biomass, depending on the acetone-to-hydrolysate volume ratio used during fractionation (Flórez-Fernández et al., 2021; Catarino et al., 2025). The extracted alginates contain a higher proportion of mannuronic acid to guluronic acid, consistent with observations made in other species of the order Fucales. High-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) revealed polymeric chain molecular weights ranging from 12 to 25 kDa (Catarino et al., 2025).

2.1.1.2 Fucose-containing sulfated polysaccharides

With a similar role and closely associated with alginates, Fucose-Containing Sulphated Polysaccharides (FCSPs), comprise the second major class of polysaccharides in brown seaweed. This L-fucose-based polymer not only plays a structural role in the cell wall by interlocking cellulose and hemicellulose scaffolds but has also been shown to be involved in physiological functions such as osmotic adjustment, particularly in algae that are subject to tidal variations (Cernadas et al., 2019; Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2017). FCSPs has been used to encompass any L-fucose-based polysaccharide, but can include xylose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, glucose, and glucuronic acid (Rioux et al., 2007; Bruhn et al., 2017; Ponce and Stortz, 2020). Regular (1→3)- or alternating (1→3)- and (1→4)-linked α-L-fucopyranose backbones are characteristic of sulfated fucans. In contrast, fucoidans have a heterogeneous backbone composed of sulfated fucose and various glycosyl residues. In all cases, the L-fucose units carry one or two sulfate groups at the C2 and/or C4 positions (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2017). A wide range of molecular weights has been reported for FCSPs, from 43 kDa to 1–600 kDa (Rioux et al., 2007). Enzymatic fractionation of H. elongata using cellulase at 40°C for 24 h, followed by purification with Amberlite IR-77 resin and dialysis, yielded FCSPs at 4.7% of dry algal weight (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014). Total fucose content ranged from 2.9% after acid hydrolysis with 1.3 M HCl at 100°C for 1 h (Martínez–Hernández et al., 2018) to 3.7% following hydrothermal treatment at 160°C and acetone fractionation (Cernadas et al., 2019). Structurally, solid state 1H NMR characterization of H. elongata FCSPs showed exclusively α-(1→3)-linked fucose chains with sulfation at the O-4 position (Figure 1) (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014).

2.1.1.3 Cellulose

Cellulose consists of D-Glucose- (1→4) chains (Figure 1). Two crystalline forms, α and β have been reported with a majority of the α- form in seaweed (Baghel et al., 2021). In macroalgae, cellulose is interlinked with other cell wall polysaccharides, and together with alginates, plays the role of a fibrillar skeleton (Baghel et al., 2021). As the predominant component of insoluble dietary fibers, cellulose was quantified at approximately 13% in Spanish H. elongata using protease and amyloglucosidase hydrolysis (AOAC enzymatic gravimetric treatment) followed by dialysis and 1M sulphuric acid hydrolysis at 100°C for 1.5h (Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2010).

As most of the polysaccharides encountered are only present in brown algae, their cell walls are not only a source of unique sugars but also represent a challenging barrier to overcome to release these valuable components and access in-cell seaweed metabolites.

2.1.2 Cellular components

Few studies describe the cellular structure of brown seaweed. While these algae share common traits, such as mitochondrial function and gene expression mechanisms with other eukaryotes, they also have unique structural features that enable photosynthesis and defense against grazers (Hurd et al., 2014). Investigations of species of Fucales, Laminariales, and Ectocarpales have resulted in a hypothetical representation of brown algal cell organization, highlighting in particular, interactions between cell components. Beyond the cell barrier, other types of sugars, known as storage sugars, can also be found. These energy-rich compounds play a crucial role in seaweed survival, as they are stored in vacuoles or aggregated into droplets within the cytoplasm (Fletcher, 2024), and only metabolized when carbon resources become scarce.

2.1.2.1 Laminarins

Laminarins are the fourth class of macromolecular carbohydrates usually found in the Phaeophyceae group. They consist of repeating glucose units linked by β-1,3-glucosidic bonds and, in some cases, by β-1,6- glycosidic bonds (Figure 1). The number of glucose units in each chain typically ranges between 20 and 50. Laminarins are commonly classified into two main groups based on the terminal unit of the chain: the G-chain group, where the chain ends with a glucose unit, and the M-chain group, where the chain ends with mannitol (Tagliapietra and Clerici, 2023). This distinction plays a key role in the solubility of the polysaccharide. The average molecular weight of laminarin is approximately 5 kDa. Only found in brown seaweed, this polysaccharide functions as an energy storage compound. As no explicit data is available on the abundance of laminarins in H. elongata, estimation can be done from the amount of glucose, while bearing in mind that glucose from cellulose can falsify the estimation. However, based on this postulate, the percentage of laminarin in H. elongata can be estimated between 1.84% and 11.7%, depending on the method of determination used (Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2010; Cernadas et al., 2019; Mateos-Aparicio et al., 2018). The proportion of laminarin fluctuates seasonally, and is typically higher in summer and fall when its storage is less critical, and lower in winter when the polysaccharide is used more actively (Schiener et al., 2015).

2.1.2.2 Polyols

Although to a lesser extent, in-cell sugars may also be encountered and associated with the algae’s storage sugars. Mannitol, a sugar alcohol composed of six carbons (Figure 1), is synthesized by brown macroalgae by means of photosynthesis (Hosseini et al., 2024). The amount of mannitol can represent up to 20% of the photosynthesis products. Originally considered as a reserve sugar, the role of mannitol in the osmotic regulation of marine algae has also been demonstrated in studies. A correlation between the level of mannitol and exposure to salinity was established by quantifying intracellular mannitol contents in different saline media (Wright and Reed, 1985). Samples of H. elongata collected at two different locations in Scotland contained amounts of mannitol ranging from 0.7% to 2.6% based on algae dry weight (Hosseini et al., 2024). Another linear polyol sugar was specifically identified in H. elongata samples, and is believed to be talitol (also known as altriol) (Figure 1) (Cernadas et al., 2019). With a very similar role to that of mannitol in osmotic regulation of the cells, talitol content was found to be higher than that of mannitol, ranging from 2.29% to 9.36%) (Cernadas et al., 2019; Wright and Reed, 1985; Chudek et al., 1984).

2.2 Other metabolites

2.2.1 Phenolics and phlorotannins

Among the range of phytochemicals produced by seaweed, brown algae contain a specific class of compounds known as phenolics. These hydroxylated aromatic ring-containing molecules are classified based on their structural characteristics (Cotas et al., 2020). The molecular weight of phenolics ranges from 126 Da to 100 kDa (Heffernan et al., 2015; Ilyas et al., 2023). Phenolics are categorized into six distinct groups: phenolic acids, flavonoids, phenolic terpenoids, bromophenol, phloroglucinol and phlorotannins. Phlorotannins, derived from the oligomerization of phloroglucinol, are the main class of phenolic compounds in brown macroalgae and are further divided into six classes named fucols, fuhalols, fucophloroethol, carmalols, eckols and phloroethol (Amsler and Fairhead, 2005; Negara et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2022). In many species, phlorotannins account for approximately 10% of the seaweed dry weight (Amsler and Fairhead, 2005; Agregán et al., 2017). Synthesized in membrane bound vesicles called physodes, phlorotannins were reported to migrate into the cell wall and to stabilize it by binding with alginate and proteins (Schoenwaelder and Clayton, 1998; Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014). Initially believed to primarily play a structural role, phlorotannins have since been shown to fulfill additional biological functions, such as wound healing, as they were seen to accumulate in wounded areas (Amsler and Fairhead, 2005), photoprotection through absorption in the UV-B range, and defense against exogenous organisms (Hurd et al., 2014; Heffernan et al., 2015; Agregán et al., 2017; Schoenwaelder and Clayton, 1998; Pangestuti et al., 2023). Compared to other brown seaweed, H. elongata contains the highest concentrations of phenolic compounds, ranging from 3 to 18 mg Gallic acid equivalent(GAE)/g dry biomass (Cassani et al., 2022; Martínez–Hernández et al., 2018; Fernández-Segovia et al., 2018). Further investigations into the chemical nature of these molecules led to the identification of not only phlorotannins (difucophloretol, fucotriphloroethol A, B and C) but also of phenolic acids (gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, carnosic acid), flavonols (cirsimaritin, myricetin, kaempferol, quercetin), hydroxybenzaldehyde, epigallocatechin, and phloroglucinol (Santoyo et al., 2011; Cernadas et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Bernaldo De Quirós et al., 2010; Rajauria et al., 2017).

2.2.2 Proteins, lipids

While green and red seaweed are known to contain levels of protein comparable to those of high-protein vegetables, reaching up to 40% of dry matter, brown seaweed generally contain lower amounts, the highest reported content being 24% in Undaria species (Holdt and Kraan, 2011). Protein content in H. elongata varies considerably depending on the method of extraction and on the harvesting period, with values ranging from 6.5% to 18% (Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2010; Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2017; Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014; Martínez–Hernández et al., 2018; Fernández-Segovia et al., 2018). A high proportion of essential amino acids, including lysine, methionine, aspartic acid and glutamic acid contributes to the high nutritional value of H. elongata compared to that of land plants (Cofrades et al., 2010; Catarino et al., 2025). From a functional point of view, brown seaweed proteins have been shown to be closely associated with FCSPs and phenolics, and hence to play a structural role in cell wall architecture (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014).

Although the lipid contents of H. elongata are relatively low (<1.5% of dry weight), several different fatty acids, including palmitic acid, stearidonic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and arachidonic acid, have been identified (Fernández-Segovia et al., 2018; Ilyas et al., 2023). Polyunsaturated fatty acids have been reported to account for 55% of the seaweed lipidic fraction, followed by saturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids (Catarino et al., 2025). Santoyo et al. (2011) successfully characterized fucosterol in H. elongata after hexane and ethanol extraction, thereby identifying this seaweed as a low content but nevertheless valuable source of bioactive lipids.

2.2.3 Pigments, vitamins, minerals

As photosynthetic organisms, brown seaweed possess a range of pigments, including chlorophylls a and c, β-carotene, and various xanthophylls, which contribute to their characteristic color (Pangestuti et al., 2023). In a comparative study of macroalgal pigments, Osório et al. (2020) identified chlorophylls a and d in H. elongata, with total chlorophyll content reaching 168 µg per gram of dry weight. Fucoxanthin, a major carotenoid in brown algae, was characterized and quantified in H. elongata byRajauria et al. (2017) using low-polarity solvent extraction. Fucoxanthin was found to account for 1.86% of the seaweed’s dry weight and exhibited significant antioxidant activity. In addition to pigments, brown seaweed are well-known sources of essential vitamins. After acid and enzymatic hydrolysis, notable level of vitamin C (0.6% of the seaweed dry weight) along with detectable amounts of thiamine, riboflavin, α-tocopherol or folates were found (Ilyas et al., 2023; Sanchez-MaChado et al., 2004).

Minerals are another important component of marine macroalgae, typically accounting for around 20% of the dry mass of brown seaweed (Cernadas et al., 2019; Martínez–Hernández et al., 2018; Fernández-Segovia et al., 2018). These minerals include macro-elements like sodium, potassium, magnesium and calcium, but also trace elements like iodine. H. elongata is particularly rich in potassium, with a favorable sodium-to-potassium ratio for nutritional applications. Furthermore, levels of heavy metals such as chromium, lead, and arsenic have been reported to be low in this species, suggesting its safe use for nutritional and nutraceutical purposes (Cernadas et al., 2019; Martínez–Hernández et al., 2018).

2.3 Functional properties of Himanthalia elongata biochemicals

As previously reported, H. elongata is a valuable source of bioactive compounds with promising health properties, and with potential applications in the human health and nutraceutical sectors.

In particular, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds, such as phlorotannins, fucoxanthin and FCSPs, have demonstrated significant efficacy in regulating oxidative stress and inflammation, thus contributing to healthy aging and reducing the risk of cancer and other chronic diseases. Furthermore, antimicrobial or hypocholesterolemic have also been attributed to H. elongata extracts.

2.3.1 Antioxidant activity

Oxidative reactions are a natural occurring phenomenon in cells, which play a crucial role in cellular functions and immune responses. Oxidative stress arises from an imbalance between the generation of free radicals and the antioxidant defense mechanisms, leading to molecular, cellular, and tissue damage. Over time, this cumulative damage contributes to the pathogenesis of a wide range of inflammatory diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and diabetes (Begum et al., 2021; Fonseca-Barahona et al., 2025).

The antioxidant potential of H. elongata is mainly attributed to its high concentrations of phenolic compounds, especially phlorotannins although this potential depends to a great extent on the extraction process used (Rajauria et al., 2013; Ummat et al., 2021).

Other bioactive chemicals of H. elongata have been reported to have antioxidant properties, including monomeric sugars, carotenoids (fucoxanthin, β-Carotene) and oxygenated fatty acids (Rajauria, 2019; Rajauria et al., 2016; Rico et al., 2018). For instance, purified fucoxanthin recovered from H. elongata exhibited similar antioxidant capacity against DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radicals as commercial fucoxanthin, in a dose-dependent manner, but a lower ferric reducing capacity (Rajauria et al., 2016). By maintaining turgor pressure and stabilizing membrane constituents such as lipids or proteins, mannitol prevents oxidative damage, which suggests antioxidant activity (Hosseini et al., 2024). The antioxidant potential of H. elongata extract was also studied in vivo on a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. The authors demonstrated that intraperitoneal administration of H. elongata ethanolic (60%) extracts to I/R-induced rats at a dose of 830 mg/kg reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, as well as the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), GPx and catalase compared to the control group, consequently protecting intestinal tissue against ischemia/reperfusion injury (Belda-Antolí et al., 2017).

2.3.2 Anti-inflammatory properties

Inflammation is a complex physiological response to harmful factors including tissue injury, pathogens, toxins and allergens. While acute inflammation is essential for healing and recovery, chronic inflammation has been widely reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of different diseases including arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases or neurodegenerative disorders (Arulselvan et al., 2016; Chavda et al., 2024; Fonseca-Barahona et al., 2025).

The anti-inflammatory activity of H. elongata has been investigated in a few studies, mainly its ability to target pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules or enzymes. In a LPS-induced inflammation model of murine macrophage, methanolic extracts significantly inhibited the production of nitric oxide (NO) and Prostaglandin D2, two pro-inflammatory mediators, at a concentration of 500 μg/mL. However, no effect was observed on the levels of mediator tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Rico et al., 2018). The anti-inflammatory potential was attributed to the presence of specific oxygenated fatty acids, phlorotannin oligomers (e.g. phloroglucinol, eckol, dieckol) or FCSPs in the seaweed extract.

In a LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-induced inflammation model of mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage, Catarino et al. (2022) evaluated the impact of simulated gastrointestinal digestion in vitro on the inflammatory activity of a phlorotannin extract from H. elongata. Gastrointestinal digestion is a major concern as it could affect the stability and bioactivity of seaweed extracts or seaweed-derived compounds. The authors observed that the concentrations of phlorotannins as well as their scavenging activities were significantly reduced after digestion. However, the digested extract showed a strong inhibitory effect on the cellular NO production in LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 macrophages, similar, or even tendentially higher than the undigested extract. These results suggest that gastrointestinal digestion may contribute to the breakdown of phlorotannin structures into degradation products or metabolites with bioactive effects, especially upon NO production or release.

2.3.3 Antimicrobial properties

Brown algae are rich in bioactive compounds such as polysaccharides, polyunsaturated fatty acids, phlorotannins and carotenoids that might have antimicrobial activity towards different pathogens (Fonseca-Barahona et al., 2025; Silva et al., 2020).

The antimicrobial properties of H. elongata extracts were reported by Gupta et al. (2010). Among the different brown Irish seaweed studied, the methanolic extract of H. elongata demonstrated the highest activity in terms of inhibition of food pathogenic and spoilage bacteria. However, heat treatment leads to a reduction in antimicrobial activity when the temperature exceeds 95°C.

2.3.4 Metabolic health benefit

Metabolic syndrome is defined as a cluster of metabolic disorders including abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia or insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidemia, leading to an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases (Gabbia and De Martin, 2020). Metabolic syndrome has emerged as a major global health concern in recent years due to its increasing prevalence. Although specific evidence related to H. elongata remains limited, Schultz Moreira et al. (2014) reported that dietary and polyphenol-rich water extracts of the seaweed inhibited α-glucosidase activity by 70% after 30 minutes of incubation. In parallel, the ethanolic extract reduced glucose diffusion by up to 65%, with minimal effect on α-glucosidase. These results suggest that H. elongata biochemicals have a complex hypoglycaemic effect.

In a more recent study, Rico et al. (2018) demonstrated that an aqueous methanolic extract of H. elongata effectively inhibited the activity of angiotensin-converting enzyme I (ACE-I) (IC50 = 65 µg/mL) in vitro, a key target in hypertension management. Additionally, the seaweed extract significantly reduced triglyceride accumulation in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes after 24 hours, without inducing cytotoxicity. These antihypertensive and lipid-lowering effects were higher than those observed with other seaweed species, such as Undaria pinnatifida or Laminaria ochroleuca, and were mainly attributed to the extract’s high phenolic and lipid contents.

2.3.5 Neuroprotective activity

Dementia is a complex disorder characterized by a decline in cognitive function beyond what is expected from normal ageing. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, language, and judgment, while typically preserving consciousness. Emotional regulation, social behavior, and motivation may also be impaired. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. Given its increasing prevalence and impact on public health, individual livelihoods and economic systems, dementia represents a significant global health concern (2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures, 2024).

In this context, the neuroprotective properties of brown algae have been investigated. In a recent study conducted by Martens et al. (2024), the effects of a lipid extract derived from H. elongata, rich in 24-(S)-saringosterol and fucosterol, were evaluated in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Dietary supplementation with the extract significantly improved the results of the cognitive tests suggesting a preventive effect on cognitive decline in object memory, spatial memory, and spatial working memory, respectively (Martens et al., 2024). Further analysis revealed a reduction in microglial activation, highlighted by a decreased Iba1 expression in the brain of treated mice. Additionally, in vitro experiments using LPS-stimulated THP-1-derived macrophages demonstrated that the extract attenuated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, proving its anti-inflammatory potential. The supplementation also led to increased levels of desmosterol, an endogenous agonist of liver X receptors (LXRs), which are known to exert anti-inflammatory effects to attenuate neuroinflammation. Furthermore, treatment with the H. elongata extract reduced AD-associated phosphorylated tau protein and promoted early oligodendrocyte differentiation.

Overall, H. elongata stands out as a rich source of bioactive compounds with diverse health-promoting properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, metabolic, and neuroprotective activities. These findings highlight its strong potential for applications in functional foods, nutraceuticals, and therapeutic formulations, although further in vivo studies and clinical trials are needed to fully validate its efficacy and mechanisms of action.

2.4 Seaweed holobiont

Seaweed are not isolated organisms, rather they are complex ecological units known as holobionts, a term that includes the host and its associated microbiota—bacteria, fungi, viruses, and microeukaryotes. These microbial partners play crucial roles in the host’s morphogenesis, growth, and defense mechanisms (Egan et al., 2013; Wichard, 2015). Environmental factors including temperature, salinity, and nutrient availability significantly influence these interactions (Loos et al., 2019). The microbiota associated with seaweed has attracted attention because of its ecological and industrial potential. Indeed, these microbial communities contribute to host health and in addition, represent a reservoir of bioactive compounds with applications in antifouling, therapeutics, health, nutrition, and biotechnologies (Menaa et al., 2020). Research on the microbiome of brown seaweed has highlighted its role in fermentation and in the production of bioactive compounds (Martin et al., 2015). Indeed, specialized bacteria, such as Flavobacteria and γ-Proteobacteria have hydrolytic enzymes that degrade polysaccharides (Michel and Czjzek, 2013). Bacteria such as Pseudoalteromonas species, (i.e. Pseudoalteromonas distincta and Pseudoalteromonas tunicata) decompose brown algae like Undaria sp. and Sargassum sp., which contain laminarin and alginate. In general, marine bacteria have developed the ability to produce a range of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes, including alginate lyases and fucanolytic enzymes (Michel and Czjzek, 2013). These enzymes often represent novel glycoside hydrolase families with unique structural and functional properties and may have potential applications extending from biofuel production to functional food and pharmaceutical development (Michel and Czjzek, 2013). Bacteria with the ability to degrade polymers may act as opportunistic pathogens or saprophytes, rather than being commensal or mutualistic symbionts of macroalgae.

Moreover, other microorganisms of eukaryotic nature can be found on the surface of the algae and are referred to as eukaryome. Studies have revealed the broad taxonomic diversity of microeukaryotes associated with brown algae, including potential novel lineages and symbionts that can have beneficial or detrimental effects on their hosts (Abdul Malik et al., 2020). Diatoms and cilates are frequently observed in the biofilm on the surface of seaweed, where they live as epiphytes and often occur in large numbers. Mycophycobiosis can exist in brown seaweed holobionts. For example, Mycophycias ascophylli belonging to the Mycosphaerellaceae family was found in the Fucaceae Ascophyllum nodosum and Pelvetia caniculata. This algicolous fungi produces antibacterial metabolites and can modify host physiology under stressful environment (Rousseau et al., 2025).

Understanding the interactions between brown algae and their associated microbiota is thus essential for the development of sustainable solutions in different industrial sectors, including food production and human health (Michel and Czjzek, 2013).

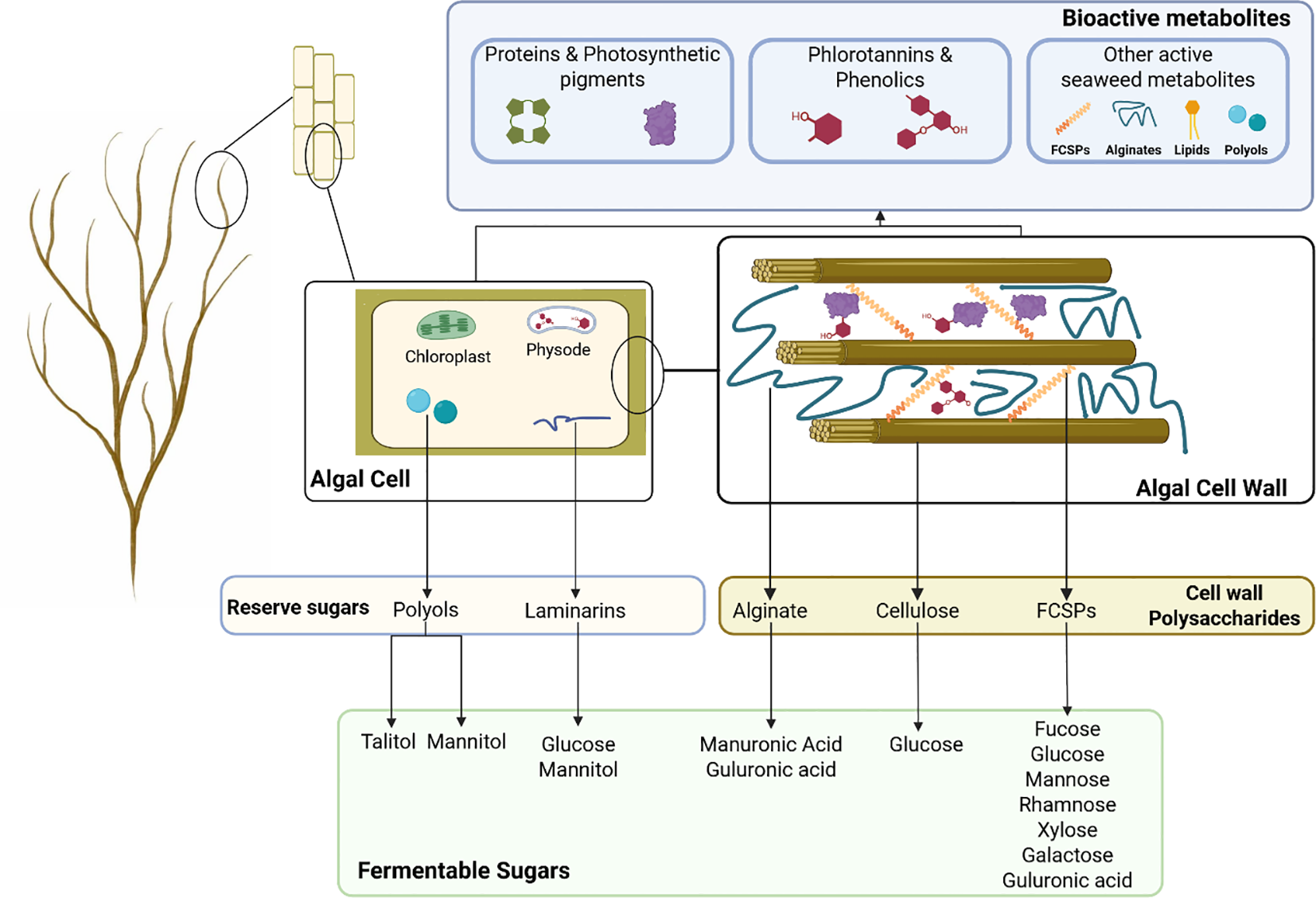

H. elongata emerges as a promising marine resource, offering a wide array of complex polysaccharides and bioactive metabolites, many of which exhibit significant biological activities and biotechnological potential. Figure 2 provides an overview of the main strategic compounds identified in H. elongata, along with their distribution within the algal tissue. Beyond its richness in functional compounds, the presence of potentially fermentable sugars suggests that microbial fermentation could represent a valuable strategy for its valorization. Building on this perspective, section 2. will discuss the specific requirements of lactic acid bacteria in relation to brown seaweed biochemical features described above.

Figure 2

Biochemical potential of Himanthalia elongata for fermentation. Algal cell wall structure is adapted from Deniaud-Bouët et al. (2017) (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2017).

3 Lactic acid fermentation: theory and applicability to Himanthalia elongata

Lactic acid fermentation is extensively described in literature, particularly in relation to plants and agricultural by-products. As a result, the biological process itself is characterized and well understood. However, only a limited number of studies have focused on its application to brown seaweed and specifically to H. elongata. This section investigates the potential interactions between the macroalga and selected microorganisms, through a comprehensive analysis of their metabolic compatibilities and illustrated by representative examples of brown algal biomass bioconversion.

3.1 Microorganisms and metabolism

3.1.1 Lactic acid bacteria

Among the large diversity of known microorganisms capable of fermentation, Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) are one of the most widely studied and most suitable for health applications. These gram-positive bacteria are named for their ability to synthesize lactic acid, and include the genera Leuconostoc, Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Vagococcus, Aerococcus, Carnobacterium, Tetragenococcus, Oenococcus and Weissella (Mozzi, 2016; Abedi and Hashemi, 2020). Due to their high acid tolerance and ability to grow below pH 5, LAB have been used as a competitive bacteria killer to improve food shelf life through lactic acid production (Reddy et al., 2008; Jackson, 2014). LAB are generally considered as nonpathogenic and hence safe for food uses (Mozzi, 2016).

LAB are considered aerotolerant anaerobes, meaning they do not require oxygen for growth but can survive and remain metabolically active under aerobic condition (Reddy et al., 2008; Jackson, 2014). In contrast to common anaerobes, they produce enzymes such as peroxidase and accumulate large quantities of Mn2+ cations in the presence of oxygen, which prevents the destruction of cytoplasmic components by toxic oxygen radicals (Jackson, 2014). LAB usually grow between 5°C and 45°C, but as they are a relatively heterogenous group of microorganisms, the temperatures corresponding to maximum growth rates differ among strains (Adamberg, 2003). The same trend has been observed for optimal pH growth conditions, with most of LAB strains optimally growing between pH 6 and 7, although some strains like O.oeni grow best in a pH range of 4.5 to 5.5 (Jackson, 2014).

3.1.2 Metabolism

3.1.2.1 Metabolic pathways

Although LAB metabolic pathways are known to convert hexoses into lactic acid, studies have revealed more complex mechanisms. This knowledge will not only help to select suitable substrates but also provide insights into improving fermentation conditions and maximizing the raw material accessibility. Sugars serve as both precursors for fermentation-derived compounds and as sources of energy for bacterial growth and development. LAB have the capacity to metabolize a broad range of sugars, including pentoses (e.g., arabinose, xylose), hexoses (e.g., glucose, mannose, fructose, galactose), and disaccharides (e.g., sucrose, lactose, maltose) (Hosseini et al., 2024; Mozzi, 2016; Abedi and Hashemi, 2020; Eiteman and Ramalingam, 2015; Abdel-Rahman et al., 2013). This suggests the suitability of H. elongata as a substrate for LAB.

LAB are classified into two main groups based on their fermentation products. Homofermentative LAB only produce lactic acid. For hexoses such as glucose, these bacteria utilize the Embden-Meyerhof pathway to generate pyruvate, which is subsequently converted into lactic acid by lactate dehydrogenase. Starting from one mole of glucose, homolactic fermentation can theoretically yield to two moles of lactic acid (Eiteman and Ramalingam, 2015). In contrast, pentose metabolism occurs via the pentose phosphate pathway, where three moles of xylose yield five moles of lactic acid. Homofermentative species are found in the genera Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Pediococcus, Enterococcus, and certain Lactobacillus species (Mozzi, 2016; Reddy et al., 2008).

In contrast, heterofermentative LAB do not only convert hexoses and pentoses into lactic acid. Rather, they use the pentose phosphate pathway for hexose metabolism and the phosphoketolase pathway for pentose utilization (Abedi and Hashemi, 2020). This metabolic strategy leads to additional fermentation by-products including acetate, formate, ethanol, and carbon dioxide. These pathways generate glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) and acetyl phosphate; G3P is converted into lactic acid, while acetyl phosphate is further metabolized into ethanol or acetate depending on enzyme availability. Heterofermentative LAB are found in the genera Leuconostoc, Weissella, Oenococcus, and in certain Lactobacillus species (Mozzi, 2016; Reddy et al., 2008). Microbial engineering has underlined the importance of the pentose phosphate pathway in pentose metabolism by LAB. Studies have notably demonstrated that shifting from the phosphohexose to the pentose phosphate pathway improves pentose utilization, particularly for arabinose and xylose conversion (Eiteman and Ramalingam, 2015).

Additionally, some strains of LAB can exhibit either homofermentative or heterofermentative metabolism and are thus classified as facultatively heterofermentative (Mozzi, 2016). This metabolic shift observed in certain Lactobacillus and Streptococcus species, is influenced by the composition of the substrate, which allows these bacteria to use a broader range of carbon sources. For instance, Streptococcus spp. primarily perform homolactic fermentation when metabolizing glucose, but switch to a heterofermentative pathway in the presence of galactose or lactose (Thomas, 1976). Substrate availability also affects the metabolic end-products. Under glucose-excess conditions, lactic streptococci primarily produce lactic acid. However, under glucose-limited conditions, they additionally produce formate, acetate, or ethanol (Thomas et al., 1979).

3.1.2.2 Aeration

While sugar composition can influence these metabolic pathways, aeration also plays an important role in the homofermentative or heterofermentative behavior of LAB.

Because LAB lack catalase, cytochromes, and an electron transport chain, they produce energy solely through fermentation (Reddy et al., 2008). Although they do not require oxygen for growth, they are considered aerotolerant anaerobes, capable of thriving in both anaerobic and aerobic conditions (Reddy et al., 2008). Oxygen can act as an electron acceptor, thereby influencing both cell growth and the production of metabolic products (Fu and Mathews, 1999). Götz et al. (1980) investigated oxygen use in Lactobacillus plantarum strains and demonstrated that the microorganisms exhibit aerobic metabolism by producing oxygen consuming-enzymes in their metabolism. Consequently, L. plantarum should be classified as a facultative anaerobe rather than as an aerotolerant anaerobe. This metabolic flexibility can lead to variations in growth rates and metabolite production.

When studying the growth and metabolite production of three Lactobacillus plantarum strains in De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) medium, Smetanková et al. (2012) observed an aeration-dependent response. Specifically, the presence of oxygen increased the final cell yield. This finding, supported by several studies (Fu and Mathews, 1999; Götz et al., 1980; Murphy and Condon, 1984), can be attributed to additional ATP production under aerobic conditions, providing an increased supply of energy that benefits microbial growth.

In some Lactobacillus strains, acetic acid and ethanol production varies depending on aeration conditions. While aerobic and anaerobic glucose metabolism in MRS medium by L. plantarum initially resulted in similar lactic acid levels, acetate accumulation was later observed under aerobic conditions (Murphy and Condon, 1984). Under these conditions, the conversion of lactic acid to acetic acid was even detected after substrate depletion. Quatravaux et al. (2006) later confirmed that substrate conversion occurs under depletion conditions in the presence of oxygen. Additionally, the same authors suggested that significant amounts of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were produced by the bacteria in the presence of O2 as a byproduct, ultimately reaching lethal concentrations.

Aeration thus emerges as a critical monitoring and control parameter to ensure proper substrate conversion and to steer the metabolism toward a specific pathway.

3.1.2.3 Amino acids conversion

Alternative substrates to glucose can be metabolized under specific stress conditions. Since LAB are already widely used in the production of fermented food products, investigating their amino acid catabolism is important to ensure both the safety and quality of these products. LAB rely on a proteolytic system—comprising cell-envelope proteinases, peptide transporters, and intracellular peptidases—that efficiently converts proteins into essential amino acid (Pessione and Cirrincione, 2016). Although few studies have investigated amino acid catabolism in Lactobacillus species, Tammam et al. (2000) demonstrated that certain Lactobacillus strains can use amino acids as a source of energy, but only in the presence of exogenous α-ketoglutarate that acts as an electron acceptor in amino acid degradation pathways. These specific pathways were reviewed by Fernández and Zúñiga (2006), who highlighted the high capacity of LAB to convert a wide range of energy sources. Using a metabolomic approach, Parlindungan et al. (2019) examined the metabolic responses of Lactobacillus plantarum strains under glucose and Tween 80 stress in modified MRS media. These authors observed distinct differences in metabolite production: glucose-stressed cells accumulated higher levels of amino acids such as lysine, glutamic acid, and aspartic acid, while cells exposed to both glucose and Tween 80 stress showed significant upregulation of metabolites like 4-aminobutanoic acid, L-proline or L-norleucine. These metabolic shifts are thought to represent adaptive survival responses of LAB under stressful conditions. However, the opposite behavior was reported by Ebrahimi et al. (2016) for L. plantarum and L. rhamnosus, which consumed more aspartic acid and glutamine in glucose enriched media.

Therefore, controlling substrate composition and availability is essential to steer LAB metabolism towards desired fermentation outcomes.

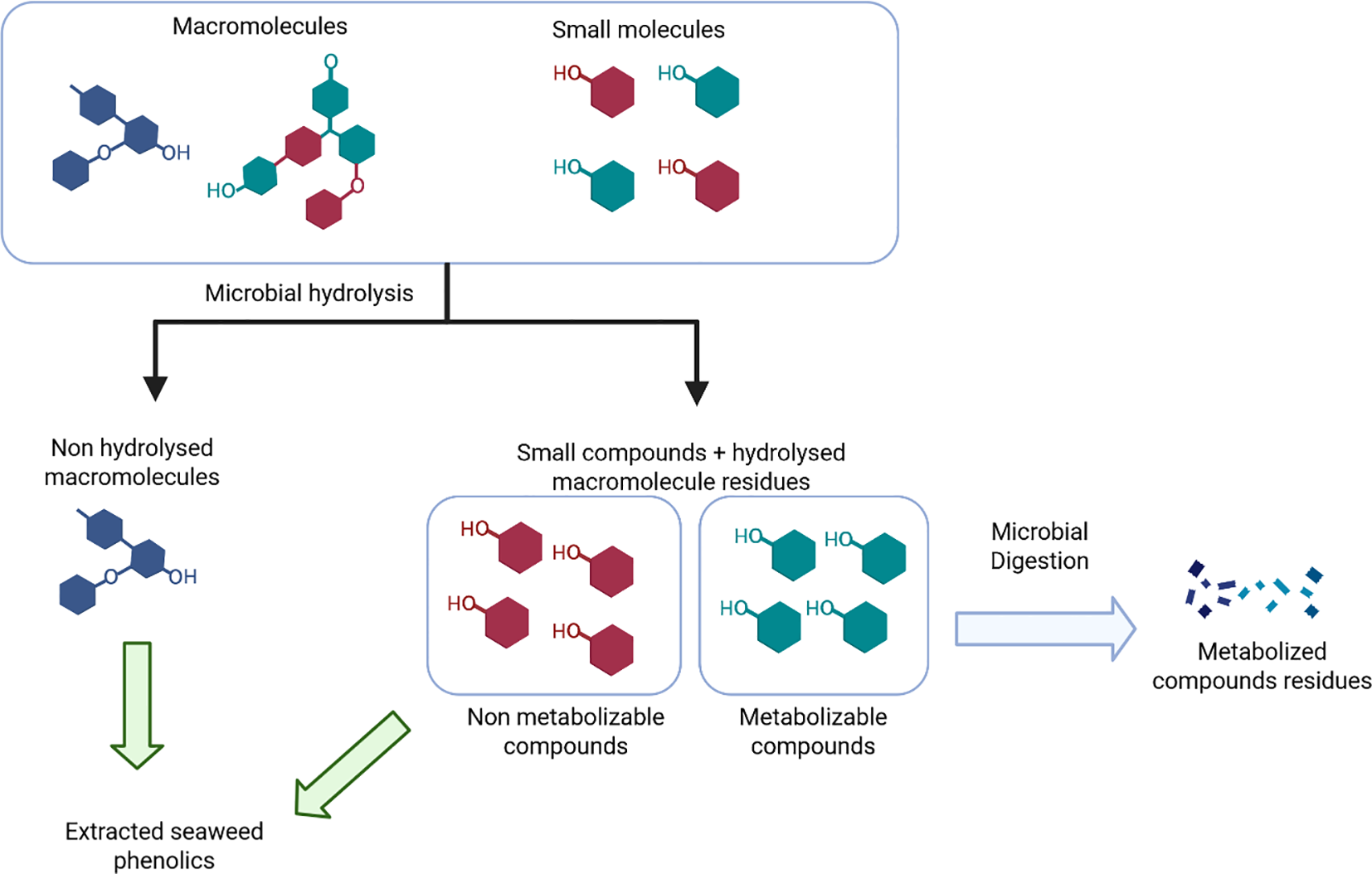

3.1.2.4 Phenolics conversion

As brown seaweed have high phenolic contents, studies investigating the impact of fermentation on phenolic-rich substrates are highly relevant to assess its effects. To date, current research focuses on land plant components. Ran et al. (2023) observed that fermentation of apple pulp extracts using Lactobacillus acidophilus had a significant influence on the composition and bioactivity of the extracts. After 72 hours of fermentation, the authors noted not only an increase in the concentration of phenolic compounds such as quercetin, p-coumaric acid, and phloridzin, but also the presence of p-hydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, and ferulic acid compared to in unfermented samples. Additionally, fermented extracts showed a significant 25% increase in DPPH radical scavenging activity, after 30 minutes of incubation with a 0.2 mmol/L DPPH alcoholic solution. These results can be attributed to the biotransformation of apple polyphenols into antioxidant compounds through fermentation caused by the production of hydrolytic enzymes, including phenolic acid decarboxylases and β-glucosidases (Filannino et al., 2015; Gan et al., 2017; Kwaw et al., 2018). A similar trend was observed in the fermentation of mulberry juice by commercial strains of Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Lactobacillus paracasei. Strain-specific differences in the amount of extracted bioactive phytochemicals were highlighted, suggesting probable variations in the expression of the appropriate hydrolytic enzymes by these strains (Kwaw et al., 2018).

Degradation of certain phenolic acids, including protocatechuic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, gallic acid, has also been reported (Filannino et al., 2015; Landete et al., 2010; Fritsch et al., 2016). Although no explanation has been put forward for the decarboxylation of protocatechuic acid into catechol, the degradation of caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid into their corresponding vinyl derivatives, as well as the conversion of gallic acid into pyrogallol, has been explained by the involvement of phenolic acid decarboxylase. The loss of these phenolics through the fermentation process could in this case lead to a decreased antioxidant activity.

Consequently, lactic acid fermentation using LAB can increase the bioactivity and bioavailability of phenolics. However, it can also reduce the amount of available phenolics, such as hydroxybenzoic or hydroxycinnamic acids, through their metabolism. Figure 3 summarizes these different behaviors in the case of the fermentation of phenolic-containing substrates. Future research are needed to study the effect of fermentation on seaweed phenolics metabolism.

Figure 3

Microbial digestion impact on phenolic content of fermented extracts.

3.2 Application to brown seaweed and Himanthalia elongata

Very few studies have investigated the fermentation potential of H. elongata. The following section therefore examines this potential by compiling findings from fermentations conducted on the whole seaweed, as well as on media enriched with brown seaweed monosaccharides or polysaccharide extracts.

3.2.1 Seaweed monosaccharides

Although LAB ability to convert common monosaccharides is known, some brown seaweed monosaccharides need further attention. Hwang et al. (2011) evaluated the capacity of seven Lactobacillus species to ferment seaweed-derived monosaccharides. They found that both the chemical nature of the sugar and the bacterial strain significantly influenced fermentation efficiency and the ratio of L-lactic acid to acetic acid produced. D-glucose, D-galactose, D-mannose, and D-mannitol produced more L-lactic acid than acetic acid. D-gluconate, D-xylose, L-rhamnose, and L-fucose led to differing ratios of L-lactic acid to acetic acid. D-glucarate, D-glucuronate, and L-arabinose produced more acetic acid. In another study conducted by Allahgholi et al. (2023), LAB consortium mainly constituted of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Levilactobacillus brevis was able to convert glucose, mannitol, galactose, and mannose to produce lactic acid as the main metabolite but also ethanol, and succinate from mannitol source. Xylose fermentation resulted in acetate production. In that study, no growth was observed on fucose, mannuronic and guluronic acids. Laminari-oligosaccharides (DP2-4), obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis of laminarin also produced lactic acid (Allahgholi et al., 2023).

3.2.2 Seaweed polysaccharides extracts

To evaluate the fermentability of brown seaweed polysaccharides, Michell et al. (1996) investigated the fermentation of extracts from H. elongata, Laminaria digitata, and Undaria pinnatifida, alongside purified alginate, fucans, and laminarins, using human fecal microbiota. Laminarins exhibited good fermentation potential, likely due to its glucose monomers, although degradation requires cleavage of β-(1→3) glycosidic bonds. Interestingly, alginate appeared to undergo bacterial metabolism via unknown pathways, while displaying a fermentation pattern similar to that of whole seaweed fibers. This suggests that the observed seaweed fiber fermentation was primarily due to alginate metabolism. In contrast, fucoidans were poorly fermented.

A similar study by Mateos-Aparicio et al. (2018) investigated the fermentation potential of H. elongata dietary fiber extracts using rat gut microbiota. Fermentation of laminarin-rich and cellulose-rich extracts was confirmed, and, notably, sulfated fucans—specifically xylofucoglycuronans and xylomannans—significantly increased the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), key indicators of microbial fermentation. In contrast, despite their low molecular weight, alginate-rich extracts were not readily fermented. These findings suggest that fermentation depends of chemical structure and monomer composition of polysaccharides. Differences in fermentation patterns between alginates and FCSPs may be explained by the variations in the chemical structure, monosaccharide composition and polysaccharide molecular weight. As these properties are species-specific, the results obtained using H. elongata extracts may be more representative than those using commercially purified polysaccharides from other macroalgae.

Allahgholi et al. (2023) also studied the behavior of bacteria on seaweed polysaccharides such as alginates, fucoidans and laminarins. However, none of the polysaccharides mentioned were used by the bacteria. Therefore, a deeper focus was made on glucose containing oligosaccharides (i.e., laminarin oligosaccharides). The authors observed a decrease in the substrate utilization with the molecular weight of the laminarin oligosaccharides, reaching no conversion for chains above 4 units of glucose. Comparison with disaccharides consumption such as sucrose or maltose showed the ability of the consortium to ferment different type of linked units.

3.2.3 Raw seaweed

Further insights were provided by Gupta et al. (2011), who assessed the growth of Lactobacillus plantarum on raw brown seaweed including Saccharina latissima, Laminaria digitata, and Himanthalia elongata. These authors found that H. elongata did not support certain bacterial growth despite the high concentrations of sugar in the fermentation broth. This result was attributed to the presence of FCSPs, which appear to be resistant to bacterial degradation under certain conditions due to their structural complexity and high fucose content (Michell et al., 1996). However, this hypothesis is debatable, as the fucose content of H. elongata was found to be comparable to that of S. latissima (Gómez-Ordóñez et al., 2010) and only slightly lower than that of L. digitata, based on values obtained using High-Intensity Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2018). Moreover, a study conducted by Mateos-Aparicio et al. (2018) reported fermentability of H. elongata’s sulfated fucans, as did a more recent study by Zhou et al. (2024), suggesting that other factors may be involved. Xue et al. (2025) also recently demonstrated that growth of L.rhamnosus is possible in broths containing fucoidans. The unique cell wall architecture of H. elongata, as reported by Deniaud-Bouët et al. (2014) as well as the nature of the strain, may play a critical role in modulating the fermentability of FCSPs.

To the best of the authors knowledge, the only study to report successful fermentation of H. elongata is that of Martelli et al. (2020), who used solid-state fermentation with Lactobacillus casei, L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus, and Bacillus subtilis.

Their findings suggest that H. elongata can support bacterial growth and could serve as a substrate for the production of antimicrobial extracts. These preliminary results open perspectives for further research on the edible seaweed H. elongata.

3.2.4 Fermentation parameters and monitoring techniques

Optimizing lactic acid fermentation of seaweed depends on several interrelated factors, the needs of the strains concerned, the composition and availability of the substrate. Therefore, the selection of appropriate seaweed species, the application of effective biomass pretreatment, the choice of LAB strains, the determination of suitable inoculum ratios and process conditions are particularly important.

The initial cell concentrations for seaweed fermentation usually reported range from 107 to 1010 CFU/mL (Allahgholi et al., 2023; Gupta et al., 2011; Martelli et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Somasundaram et al., 2025).These concentrations are crucial to ensure rapid fermentation onset and effective substrate utilization. As detailed in Section 2.1.2.2., aeration is a critical parameter that significantly influences bacterial metabolism and therefore needs to be taken into consideration. Temperature plays a key role in modulating microbial activity and fermentation kinetics. Brown seaweed fermentation is typically carried out at temperatures between 30°C and 37°C (Gupta et al., 2011; Martelli et al., 2020; Sharma and Horn, 2016), which supports optimal bacterial growth while maintaining the structural and biochemical integrity of the substrate.

While most LAB can tolerate pH below 5, optimal growing conditions are often set between 5 and 6 (Fu and Mathews, 1999; Tang et al., 2017). In a study conducted by Bühlmann et al. (2022), fermentation of food waste maintained at pH 6 improved lactic acid production more than when set at pH 5. Additionally, high chloride and sulfate contents are believed to provide a high buffering capacity, which can then influence bacterial behavior (Herrmann et al., 2015). As a biologically mediated process, fermentation inherently requires time for completion. This duration encompasses both the lag and exponential growth phases of the microbial population, as well as progressive catabolism of the substrate. The overall fermentation kinetics are influenced by several factors, including microbial activity, mass transfer limitations, substrate concentration, temperature, or the viscosity of the medium. For instance, Lactobacillus spp. typically enter the exponential growth phase between 15 and 20 h post-inoculation (Fu and Mathews, 1999). Fermentation of brown seaweed has been reported across a broad range of durations, ranging from a few hours (Gupta et al., 2011) to several days (Allahgholi et al., 2023), and even more than a month in the case of ensiling approaches (Cabrita et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2020). While extended fermentation times may be necessary to ensure effective bioconversion, they can involve economic and logistic challenges in industrial settings where time efficiency is critical. Furthermore, understanding the kinetics of fermentation is essential not only to maximize the production of target metabolites, but also to avoid the formation of undesirable compounds that may occur under suboptimal conditions, such as nutrient limitation or prolonged stress.

For this reason, the use of reliable monitoring techniques is of particular interest. Lactic fermentation primarily yields volatile organic acids (VOAs), lactic acid being the predominant metabolite. Other short-chain fatty acids such as acetic, propionic, and formic acids may also be produced (Eş et al., 2018). These organic acids are key indicators of the fermentation process. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is commonly used to detect lactic acid and other VOAs. Detection is typically performed at 210 nm under isocratic elution using either a 0.05 M phosphate buffer at pH 2.5 (Gupta et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2015; Santanatoglia et al., 2024) or a 5 mM aqueous sulfuric acid solution (Allahgholi et al., 2023; Eş et al., 2018; Lopez-Santamarina et al., 2022).

Given the high concentration of phenolic compounds in H. elongata, which are associated with various bioactivities, monitoring these metabolites is also indispensable. HPLC coupled with a diode array detector (DAD) is frequently used for this purpose, with a C18 column maintained at 40°C. The mobile phase typically consists of water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B), both acidified with 0.1% formic acid (Maiorano et al., 2022; Santanatoglia et al., 2024). Instead, Martelli et al. (2020) (Martelli et al., 2020) used a gradient elution system comprised of acidified acetonitrile (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent B).

While the current knowledge of lactic acid fermentation in agricultural contexts and terrestrial plants provides a valuable framework, several critical factors must be considered to effectively adapt this process to macroalgae. In particular, the complex, condition-dependent behavior of microorganisms and the nature and bioavailability of algal sugars present specific challenges for the fermentation of H. elongata, which remains largely unexplored. These key issues and their implications will be addressed in the following section.

4 Discussion: macroalgal lactic acid fermentation challenges

Due to the complexity of seaweed biomass, its subsequent conversion through fermentation raises multiple challenges. Therefore, the safe and efficient production of fermented extracts from H. elongata requires process understanding and optimization.

4.1 Carbohydrate bioavailability: the role of biomass pretreatments

As described in section 1., H. elongata chemical architecture highlights a rich but low accessible biomass.

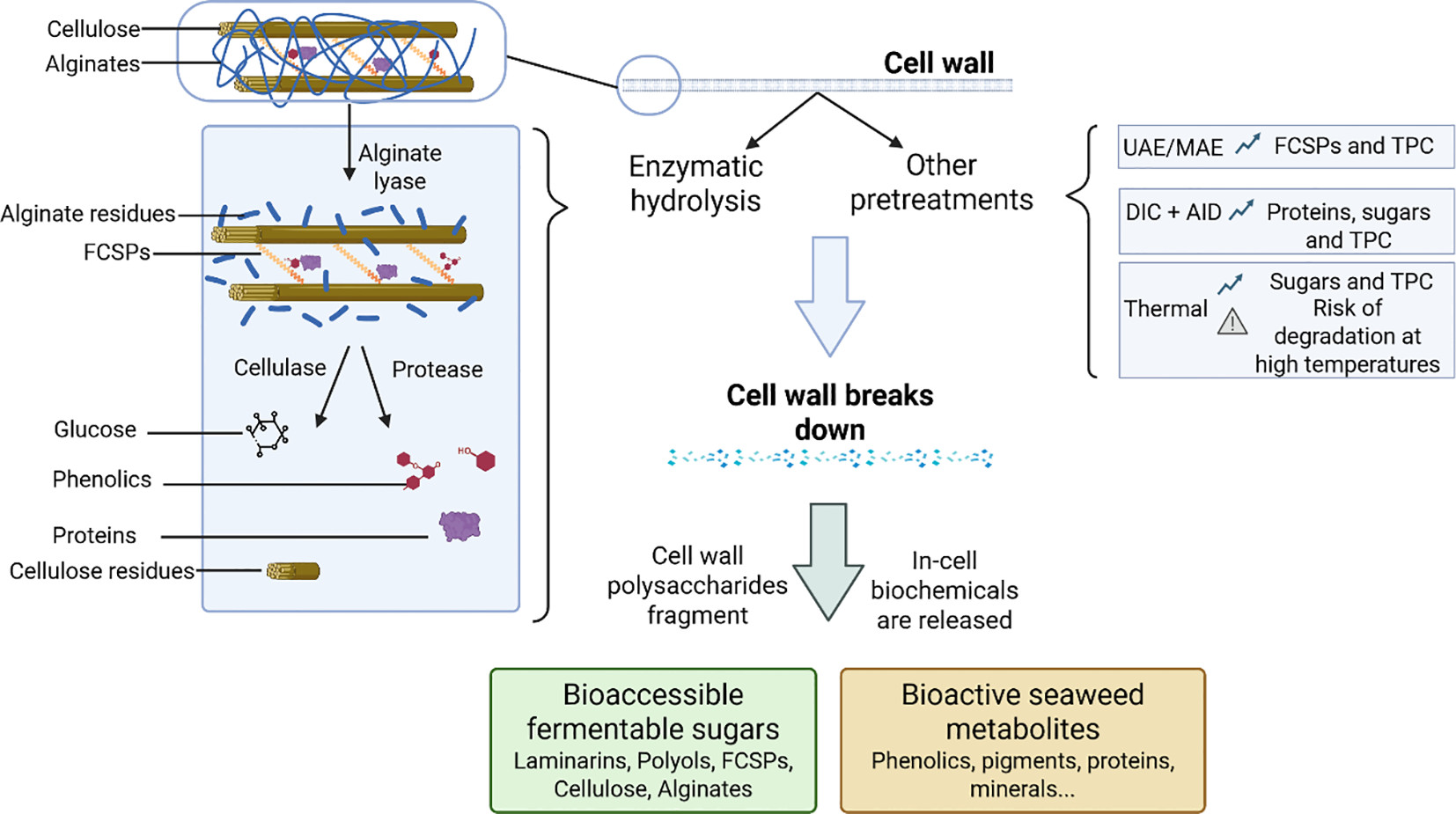

The pretreatment of seaweed biomass consists in an appropriate operational step aimed at improving substrate availability and maximizing the extraction of bioactive molecules that can later be used to facilitate biochemical conversions such as fermentation. Extraction of seaweed components requires cell wall disruption, a step that can be facilitated by pretreatment (Sharma and Horn, 2016; Postma et al., 2017). In this review, pretreatment methods designate the downstream processing steps following harvesting and preceding fermentation, with the purpose of enhancing the release and recovery of carbohydrates and polysaccharides. These compounds are particularly relevant in the context of fermentation, as they can be hydrolyzed into fermentable sugars that constitute essential substrates for the algal fermentation process. Different pretreatments are presented in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Materials) and are discussed below.

4.1.1 Physical pretreatments

Physical pretreatment includes mechanical and irradiation-based methods. Mechanical techniques mainly affect the physical structure of seaweed by reducing particle size, increasing the surface-to-volume ratio and probably modifying crystallinity and structural integrity (Maneein et al., 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2015). In Sargassum wightii, mechanical techniques including shaking and stirring, increased the release of reducing sugars compared to the untreated suspension control (Kooren et al., 2023). The same study further demonstrated that ultrasonication at 40 kHz for 15 min enhanced sugar release. This effect was attributed to the higher shearing forces generated during ultrasonication and magnetic stirring (Karray et al., 2015). Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), which uses microwaves to break down cell walls and release intracellular compounds, has proven to be effective in boosting the recovery of carbohydrates as well as total phenolics and flavonoids from brown seaweed, e.g. H. elongata and Ascophyllum nodosum in just a few minutes of extraction (Cox et al., 2012; Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2020). MAE applied to seaweed generally uses short extraction times ranging from a dozen seconds to fifteen minutes, at 250 to 1000W microwave power and with a temperature up to 110°C (Cox et al., 2012; Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2018). Another irradiation-based pretreatment that is commonly used to extract bioactive compounds from brown algae is Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE). This method involves using ultrasonic baths or probes to emit high-frequency sound waves that cause cavitation in a liquid medium. This process produces and then collapses microscopic bubbles that break down cell walls and reduce the size of the particules, thereby enhancing the release of bioactive compounds and improving solvent penetration as well as mass transfer (Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2020; Terme et al., 2020). Garcia-Vaquero et al. (2020) demonstrated that UAE improved the extraction of FCSPs and carbohydrates under specific amplitude and duration conditions. UAE also showed to cause partial depolymarization of hydrocolloids (Lesgourgues et al., 2024). Compared to UAE, MAE - utilizing smaller volumes of solvents - yielded FCSPs at levels nearly ten times higher than those obtained with UAE. Nevertheless, the heat produced during the MAE could degrade heat-sensitive compounds (Michalak and Chojnacka, 2014). Combining these two techniques, authors demonstrated that ultrasound-microwave-assisted extraction UMAE generated higher yields of compounds compared to UAE and MAE methods separately (Garcia-Vaquero et al., 2020).

4.1.2 Thermal and pressure pretreatments

Thermal pretreatment consists of applying heat to algae biomass, while the pressure pretreatment uses high pressure, often combined with heat. Like other pretreatment, the aim is to break down cell walls and increase extraction efficiency (Vanegas et al., 2014). In their study of various algal species, including Sargassum wightii, Kooren et al. (2023) demonstrated that all thermal pretreatments (autoclaving, water bath heating, oven incubation, and hot plate heating) tested for 15 min. at temperatures ranging from 100°C to 115°C significantly enhanced sugar yield compared to the untreated control. Among these methods, oven incubation was the most effective, yielding a maximum sugar content of 16%, representing a 1.81-fold increase over the untreated control. Hydrothermal treatment of H. elongata under non-isothermal conditions (120°C - 220°C) was also investigated by Cernadas et al. (2019). Their study reported the highest extraction yield (70.7% on a dry weight basis) at 180°C, while the concentrations of monosaccharides, including glucose, fucose, galactose, and xylose, increased with a temperature up to 180°C. Among other pressure-dependent pretreatment methods, Pliego-Cortés et al. (2024) investigated the impact of Instant Controlled Pressure Drop (DIC) and its combination with Air Impingement Drying (AID) on the extraction of bioactive compounds from Sargassum muticum. Results showed that especially when coupled with AID, DIC significantly enhanced the extraction of neutral sugars and polysaccharides such as fucoidan and sodium alginate compared to oven-dried and freeze-dried samples without DIC treatment. This improvement was attributed to DIC’s ability to increase diffusivity by disrupting cell structures and increasing the release and bioavailability of intracellular compounds.

4.1.3 Enzymatic pretreatments

Considered as a sustainable process, enzymatic assisted extraction (EAE) involves the use of enzymes to degrade the seaweed by disrupting the structural integrity of the cell wall and membrane. It is claimed to be a promising alternative to harsh chemical treatments for the extraction of bioactive compounds and fermentable sugars while simultaneously preserving valuable components.

4.1.3.1 Proteases

These enzymes have emerged as highly effective biocatalysts for the extraction of bioactive compounds from various species of seaweed. Used in Nizamuddinia zanardinii, Alcalase® enabled the highest FCSPs recovery (5.58%) of all the enzymes tested (range: 4.28% – 4.80%). The enhanced FCSP extraction was attributed to effective degradation of the seaweed cell wall matrix. Additionally, protease-recovered FCSPs exhibited low protein content which both confirms the close association of FSCPs with proteins within brown algal cell wall reported by Deniaud-Bouët et al. (2014) but also the action of protease on the cell wall matrix. Alcalase also proved effective for the extraction and purification of alginates from Sargassum angustifolium (Borazjani et al., 2017). Combined with cellulase, the two enzymes produced a higher alginate yield (3.50%) than water-treated seaweed samples (3.30%). The crude alginate extracts obtained using protease and cellulase contained significantly lower levels of proteins and polyphenols, which again confirms the close link between structural polysaccharides, proteins and phenolic compounds in the cell wall. This suggests that using these enzymes as a pretreatment step can effectively increase cell wall degradation and hence cell wall breakdown thereby facilitating the release of valuable biochemicals.

4.1.3.2 Cellulases

Cellulases are hydrolytic enzymes that catalyze the depolymerization of cellulose into glucose or oligosaccharides. As cellulose is a structural component of the algal cell wall and a valuable source of fermentable sugars, its degradation represents a challenging step in pretreatment of seaweed before fermentation. The action of cellulases has shown considerable promise in enhancing the extraction of bioactive compounds from brown seaweed. For instance, in Sargassum horneri, treatment with Celluclast®, a commercial cellulase, resulted in the highest carbohydrate concentration in the crude extract (88.7 g/100 g) along with the highest sulfate content (12.01 g/100 g), while maintaining low levels of protein (4.01 g/100 g) (Sanjeewa et al., 2017). Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy of the polysaccharide extracts further suggested the presence of FCSPs. Similarly, in Sargassum muticum, cellulase treatment yielded the highest overall extraction yield (31.3%) compared to other enzyme treatments (ranging from 25.6% to 28.1%) and to hot water extraction (22.5%). It also released the largest quantity of soluble sugars (87.3 mg glucose equivalents/g lyophilized extract), more than double that obtained with hot water extraction. These findings underscore the efficacy of cellulase as a pretreatment strategy to maximize the recovery of fermentable sugars and bioactive compounds from brown macroalgae.

4.1.3.3 Alginate lyases

The efficiency of cellulase in hydrolyzing brown macroalgal biomass can be significantly enhanced by adding alginate lyase. This enzyme specifically cleaves the uronic acid linkages in alginate, which is a major structural polysaccharide in brown macroalgae that limits access to intracellular carbohydrates. In brown macroalgae like Laminaria digitata, the synergistic application of cellulase with 2% alginate lyase led to a steady increase in glucose yield over time (4, 6, and 8 h) (Manns et al., 2016). The highest glucose release was achieved after 8 h using 10% cellulase and 1% alginate lyase, yielding approximately twice the amount of glucose compared to treatments without alginate lyase. Similarly, Sharma and Horn (2016) reported that saccharification yields improved with increasing proportions of alginate lyase in the enzyme mixture, and reached maximum at a 90:10 cellulase-to-alginate lyase ratio. While cellulase alone is capable of degrading seaweed biomass, the incorporation of alginate lyase significantly enhanced sugar release, likely by increasing accessibility to other polysaccharides and reducing structural barriers within the cell wall. Moreover, alginate degradation may reduce the viscosity of the hydrolysate, thereby facilitating mass transfer and enzyme diffusion throughout the matrix.

The choice and implementation of appropriate biomass pretreatment methods are essential to maximize substrate bio-accessibility, which, in turn, can enhance the efficiency of microbial digestion. These pretreatments can disrupt the complex algal matrix, thereby facilitating the release of fermentable sugars and bioactive compounds. In the case of H. elongata, the impact of different pretreatment strategies—whether physical, chemical, or enzymatic—can vary considerably in terms of both the yield and the composition of the extracted compounds. A general model of brown algae cell wall structure was proposed by Deniaud-Bouët et al. (2017), but the case of H. elongata appears to be slightly different. Compared to other Fucales, H. elongata is less susceptible to protease and cellulase treatments, but degradation is greater when treated with alginate lyase. This suggests a distinct cell wall architecture, potentially characterized by a higher prevalence - or a different arrangement - of cell wall polysaccharides (Deniaud-Bouët et al., 2014). As a result, targeting polysaccharides degradation may be particularly effective for disrupting the H. elongata cell wall to facilitate the release of fermentable sugars.

Figure 4 gives an overview of the main pretreatment approaches investigated and their application to H. elongata.

Figure 4

Biomass pretreatment methods applicable to Himanthalia elongata to enhance the bio-accessibility of its biochemicals. UAE, Ultrasounds Assisted Extraction; MAE, Microwave Assisted Extraction; DIC, Instant Controlled Pressure Drop; AID, Air Impingement-Dried; FCSPs, Fucose-Containing Sulphated Polysaccharides; TPC, Total Phenolics Content.

4.2 Potential interactions to consider

As a complex and living substrate, interaction or interference can occur between H. elongata biochemicals or holobiont and exogenous LAB, therefore influencing the fermentation process.

4.2.1 Interferences with endogenous microorganisms

Complex interactions may occur between the endogenous microbiota of brown macroalgae and exogenous microbial inoculants during fermentation. LAB are commonly used in fermentation processes for their ability to enhance food preservation through substrate acidification, which inhibits the growth of pathogenic microorganisms (Dimidi et al., 2019). According to Sørensen et al. (2021), fermentation of Alaria esculenta by the endogenous microbiota failed to reduce the pH to values below 4.6 and led to the development of undesirable organic acids (e.g., butyric) and ethanol as well as harboring a high alpha diversity of microorganisms, indicating the lack of a suitable naturally occurring starter cultures in the seaweed. Moreover, competitive interactions for nutrients and ecological niches may arise between endogenous and exogenous microorganisms, potentially disrupting fermentation dynamics and reducing process efficiency (Shetty et al., 2019). On the other hand, Abdul Malik et al. (2020) emphasized the ecological role of surface microbiota associated with macroalgae that can serve as a biological defense system against pathogens and environmental stressors by acting as an antifouling agent. Likewise, Du et al. (2021) demonstrated that the addition of exogenous probiotics to fermented vegetable waste not only improved fermentation quality but also modulated the microbial community by suppressing undesirable bacteria.

Understanding the interplay between native and introduced microbial populations is critical for optimizing fermentation strategies and enhancing substrate biotransformation. If lactic fermentation can be used to prevent undesirable bacterial growth, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet addressed the potential interactions between the endogenous microbiota of brown macroalgae and exogenous microbial inoculants during fermentation.

4.2.2 Potential inhibitors

As complex substrates, certain brown seaweed biochemicals and components raise concerns regarding potential inhibitory effects on LAB during fermentation. Rozès and Peres (1998) investigated the influence of phenolic acids (caffeic, ferulic, and tannic acids at 1 g/L in ethanol) on the growth of Lactobacillus plantarum and reported inhibitory effects from all three compounds. Specifically, caffeic and ferulic acids reduced viable cell counts over time compared to the control, while tannic acid prolonged the lag phase and also decreased cell viability.

As discussed earlier, phlorotannins display antimicrobial properties, which may be advantageous in extracts derived from H. elongata but problematic in fermentation processes due to their potential activity against beneficial microorganisms. The antibacterial action of phlorotannins has been attributed to the disruption of oxidative phosphorylation and binding to bacterial proteins—including enzymes and membrane components—ultimately leading to cell lysis. For example Shannon and Abu-Ghannam (2016) reported strong inhibition of Vibrio species by low-molecular-weight phlorotannins through membrane damage.

Catarino et al. (2021) evaluated the modulatory effects of phlorotannin-rich extracts from Fucus vesiculosus on Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium animalis. The bacterial growth performed in MRS broth without glucose and supplemented with extracts corresponding to up to 0.35% (w/v) phlorotannins, revealed that phlorotannins delayed exponential bacterial growth or reduced final viable cell counts across all strains. The extent of inhibition, however, varied depending on the strain and extract concentration, with Lactobacillus strains generally less affected than Bifidobacteria. The authors emphasized that due to variability in phlorotannin content and accessibility within brown seaweed, extrapolation to whole biomass fermentation remains difficult. Fermentation of phlorotannin-rich seaweed may still be feasible, even in the presence of inhibitory effects, but further research is required to clarify the impact of phlorotannins on LAB inocula.

In addition to phlorotannins, high salt concentrations can also hinder microbial growth (Maneein et al., 2018). Given the notable salt content of H. elongata, elevated salinity in fermentation media should be considered when optimizing fermentation conditions and selecting appropriate strains.

4.3 Biochemical impact of fermentation

During the fermentation process, LAB metabolize seaweed-derived biochemicals, leading to a series of biochemical transformations. These modifications can significantly modify the composition and functionality of the resulting extracts.

4.3.1 Biological activities

4.3.1.1 Antioxidant activity

In parallel to the internal bioactivity of H. elongata biochemicals, fermentation can enhance the antioxidant capacity of the seaweed extracts by increasing the concentration of bioactive compounds, including antioxidant polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids (Pérez-Alva et al., 2022; Sarıtaş et al., 2024). Fermentation of Sargassum sp. with different marine lactic acid bacteria was investigated by Shobharani et al. (2014). Fermentation was shown to increase total phenolic content, associated with higher antioxidant activity. Similarly, fermented extract with E. faecium was shown to have significantly higher activity than unfermented samples. These results were attributed to the breakdown of the seaweed cell wall during fermentation, thus facilitating the release of polyphenols while enhancing antioxidant activity. Additionally, β-glucosidase-producing lactic acid bacteria have been shown to increase the total phenolic content of phenolic-rich substrates during fermentation, likely through the conversion of isoflavone β-glucosides into their corresponding aglycones (Gan et al., 2017). By analogy, it can be postulated that H.elongata phlorotannins, such as flavonol-like compounds, may also undergo β-glucosidase-mediated hydrolysis during lactic fermentation. This transformation could increase the release and bioavailability of phenolic monomers, thereby enhancing the antioxidant activity of fermented algal substrates.

4.3.1.2 Anti-inflammatory activity