Abstract

The constant need to search for new drugs is a major driver for the discovery of new molecules of pharmaceutical interest. Natural products (NPs) of microbial origin have been recognized for their therapeutic properties, with Actinomycetota being one of the leading groups in terms of their production. Due to the fact that Actinomycetota contain in their genomes a high number of biosynthetic gene clusters that may not be expressed under common cultures conditions, the strategy known as “one strain many compounds” (OSMAC) has emerged as an important approach to expand the chemical diversity of actinobacterial metabolites. In this work, 8 OSMAC conditions were applied to 10 actinobacterial isolates previously obtained from deep-sea samples collected at Madeira and Azores archipelagos, Portugal, in an attempt to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters capable of producing new NPs. Organic extracts from the isolates grown under the different conditions (80 in total) were tested for their antimicrobial, anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities, revealing 11 extracts that inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium or Candida albicans, and 9 extracts that reduced the cellular viability of T-47D or HepG2 cancer cells, while no anti-inflammatory activity was observed. Metabolomic profile of the actinobacterial extracts revealed metabolites matching known NPs, as well as features suggestive of previously unreported compounds (15 in total). This study demonstrated that the OSMAC approach is effective in modulating secondary metabolism in Actinomycetota and is consequently a useful resource for the discovery of new molecules with biotechnological potential.

1 Introduction

Natural products (NPs) of microbial origin have inspired many commercial pharmaceutical products. Over the past decade, research efforts have increasingly focused on the marine environment, leading to the discovery of numerous novel metabolites with relevant biological activities. Most of these new compounds were obtained from marine Actinomycetota (Ragozzino et al., 2025) which are known to produce a wide array of bioactive molecules with antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer and antioxidant properties, among others (ul Hassan and Shaikh, 2017).

However, one of the main barriers in NPs research is the high rate of rediscovery of already known metabolites, which can hinder drug discovery efforts and waste resources (Palma Esposito et al., 2021). In order to overcome this issue, recent strategies have focused on prioritizing strains with proven biosynthetic potential or unique ecological origins. Advances in microbial DNA sequencing technologies have allowed the sequencing of the entire genome in a rapid and cost-effective manner. This triggered the development of new genome analysis tools, such as antiSMASH, for the identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Notably, bacterial BGCs have been found to outnumber the molecules isolated in the laboratory, but most of these are often silent or cryptic and are not expressed under standard cultivation conditions. The One Strain Many Compounds (OSMAC) approach has been shown very efficient in activating silent BGCs, being a promising strategy for the discovery of new bioactive compounds (Palma Esposito et al., 2021; Schwarz et al., 2021). Recent studies have highlighted the potential of the application of this approach to marine microorganisms, including Actinomycetota (Tawfike et al., 2019; Palma Esposito et al., 2021). In particular, exposing Actinomycetota to specific elicitor molecules has been shown to activate cryptic genes (Covington et al., 2021; Zong et al., 2022). Elicitors are substances that stimulate certain physiological and/or morphological changes when added in trace amounts to microbial cultures (Nair et al., 2009), and can be used as a direct extension of the OSMAC approach (Romano et al., 2018). Several elicitation strategies have been developed to break the silence of cryptic genes, namely, chemical, biological and molecular strategies (Verma et al., 2018). Chemical elicitors are typically synthetic or non-biological compounds that, when added to the culture medium, can trigger changes in secondary metabolism. Examples include dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethanol dimethyl sulphone, sodium butyrate, and certain inorganic salts and rare earth elements such as scandium and lanthanum, all of which have been reported to modulate the metabolic output of Actinomycetota (Verma et al., 2018). Biological elicitation can be achieved through three main approaches: co-cultivation with other microorganisms, the addition of microbial lysates, and the use of microbial cell components, such as cell wall fragments or signaling molecules (Verma et al., 2018). Molecular elicitation may involve genome mining strategies. In this process, gene knockout studies are performed and the products of the desired genes are analyzed by different techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). In addition to elicitation, variation in culture parameters, such as temperature, pH and change in nutrient regimes, has been found to trigger the production and discovery of new NPs, also constituting important strategies within the OSMAC approach (Romano et al., 2018).

In this line, the objective of this work was to apply the OSMAC strategy to ten actinobacterial isolates previously obtained from deep-sea samples collected at Madeira and Azores archipelagos, aiming to induce the production of novel bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical relevance.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Origin and characterization of actinobacterial strains

We used ten actinobacterial strains previously isolated, as part of an independent study, from eight deep-sea samples collected in the North Atlantic Ocean at Madeira and Azores archipelagos (Table 1). Samples collected at Madeira were obtained from three scientific expeditions with the aid of multiple underwater vehicles and sampling gears at depths between 496 and 2300 m: (i) SEDMAR 1/2017 mission, led by the Portuguese Hydrographic Institute, in 2017; (ii) OOM2018_LUSO using the ROV LUSO6000 from the Task Group for the Extension of the Continental Shelf – EMEPC, on board the NRP Almirante Gago Coutinho of the Portuguese Hydrographic Institute (IH); and (iii) Deep_Madeira 2019 using the manned submersible Lula1000 from the Rebikoff-Niggeler Foundation (Braga-Henriques et al., 2022). Azorean samples were collected during the R/V Meteor cruise M150 BIODIAZ – Controls in benthic and pelagic BIODIversity of the Azores (George et al., 2018) from August to October 2018 at depths between 150 and 3000 m.

Table 1

| Strain code | Sample code | Sample matrix | Depth (m) | Geographic coordinates | Sampling gear | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (dbar) | Mission | Pre-treatment applied to the samplesc | Isolation Mediumf | Growth Mediumj | Closest Taxonomic identificationl | % Similarity | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C_033 11 | OOM2018_033 | Coral | 498 | 32°37'55.5"N 17°04'00.1"W |

ROVa LUSO (Biobox) | 12.4 | 503.6 | OOM2018_LUSO | PT1d | M1g | M1 | Actinopolymorpha rutila | 99.71 | PX127723 |

| C_107 7 | M150-ABH_107 | Coral | 892 | 37° 54,975' N 029° 03,868' W |

Agassiz trawl | 8.79 | 901 | M150 BIODIAZ | PT1 | M1 | M1 | Kocuria palustris | 99.78 | PX127725 |

| Sed_143 1 | M150_ABH_143 | Sediment | 2062 | 38° 03,697' N 029° 25,627' W |

Multicorer | 4.1 | 2089.4 | OOM2018_LUSO | PT1 | NPSh | MBk | Micromonospora maritima | 99.35 | PX127721 |

| Sed_313 25 | M150_ABH_313 | Sediment | 1500 | 38° 42,099' N 027° 25,995' W |

Multicorer | 5.03 | 1517 | M150 BIODIAZ | PT1 | M1 | MB |

Micromonospora

saelicesensis |

99.93 | PX127720 |

| S_113 7 | M150_ABH_113 | Sponge | 892 | 37° 54,975' N 029° 03,868' W |

Agassiz trawl | 8.79 | 901 | M150 BIODIAZ | PT1 | M1 | M1 | Nocardiopsis lucentensis | 99.86 | PX127719 |

| Sed_383 10 | M150_ABH_383 | Sediment | 496 | 37° 16,711' N 24° 43,399' W |

Hanning grab | 12.03 | 501 | M150 BIODIAZ | PT1 | M4i | MB |

Salinispora

cortesiana |

99.62 | PX127722 |

| MA3 2.13 | M_MA3 | Sediment | 2300 | 32° 31,18.48' N 16° 58,7.38' W |

Smith-McIntyre grab | 2.5 | 2310 | SEDMAR 1/2017 | PT1 | M1 | M1 | Streptomyces profundus | 100 | OQ363655 |

| S_071 1.15 | OOM2018_071 | Sponge | 650 | 32°38'14.6"N 17°06'30.6"W |

ROV LUSO (biobox) | 11 | 657.4 | OOM2018_LUSO | PT2e | M4 | MB | Streptomyces xinghaensis | 99.78 | PX127718 |

| C_014 11 | #014 | Coral | 804 | 32° 38,031' N 17°04,937'W |

HOVb Lula1000 (biobox) | 10.4 | 812.2 | Deep_Madeira 2019 | PT1 | NPS | M1 | Microbacterium aerolatum | 98.70 | PX127726 |

| C_017 1 | #017 | Coral | 804 | 32° 38,031' N 17°04,937'W |

HOV Lula1000 (biobox) | 10.4 | 812.2 | Deep_Madeira 2019 | PT1 | M1 | M1 | Microbacterium amylolyticum | 98.33 | PX127724 |

Origin, isolation conditions, and taxonomic identification of the actinobacterial strains used in this study.

Remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

Human-occupied vehicle (HOV).

The samples resulting from the pre-treatment were ten-fold diluted until 10–4 and an aliquot of 100 µL of each sample (100-10-4) was spread in duplicate over the surface of different isolation media.

PT1: consisted in incubation of one g of samples in a water bath at 57°C for 15 minutes.

PT2: consisted in the incubation of one g of the sample with antibiotics (nystatin, cycloheximide and nalidixic acid at 20 mg/mL each) for 30 minutes.

Isolation medium was supplemented with cycloheximide, nystatin and nalidixic acid at 50 mg/mL each.

Composition of medium M1: 10 g starch, 4 g yeast extract, 2 g peptone, 15 g agar and seawater to a final volume of 1 L.

Composition of medium Nutrient Poor Sediment Agar (NPS): 100 mL NPS extract (prepared by washing 900 mL of sand collected from a high-energy beach with 500 mL of seawater), 17 g agar and seawater to a final volume of 1 L.

Composition of medium M4: 2 g chitin, 18 g agar and seawater to a final volume of 1 L.

A liquid version of the growth medium was used, without the addition of agar.

Composition of medium Marine Broth (MB): 40.2 g of commercial medium marine broth (Condalab, Madrid) and deionized water to a final volume of 1 L.

For taxonomic identification, DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A® Bacterial DNA Kit ((Omega Bio-Tek, GA, United States). 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using the universal primers 27F (5'-GAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3'). Sequencing of the amplified DNA was performed by GenCore, I3S (Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde, Portugal). 16S rRNA gene sequences were analyzed using the Geneious Prime 2022.1.2 software and the resulting consensus sequences were compared to the GenBank database using the blastn algorithm and confirmed with the databases EzTaxon. The taxonomic assignments shown in the table are based on EzTaxon results.

Table 1 summarizes the origin, isolation conditions, and taxonomic identification of the actinobacterial strains used in this study.

2.2 Growth of actinobacterial strains under OSMAC conditions

Each actinobacterial isolate selected for this study was grown under eight different OSMAC conditions. In all cases, growth was performed in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 mL of liquid culture medium. For each strain, the inoculum was obtained by transferring a loopful of biomass from the corresponding agar medium (Table 1) into the liquid medium. Cultures were incubated in the dark at 25 °C and 100 rpm for 5 days, in an orbital shaker (Model 210, Comecta SA, Barcelona, Spain). After this period, 0.5 g of Amberlite® XAD16N resin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to the medium and cultures were incubated for another three days.

Controls consisting of Actinomycetota strains grown in their standard medium (M1 or MB; Table 1) without any OSMAC conditions were also included. In addition, to assess the influence of the OSMAC condition alone, uninoculated controls were performed in parallel for each condition under study.

The conditions tested included:

2.2.1 Application of heat shock

Each strain was inoculated in a 50 mL Falcon tube containing 30 mL of the respective growth medium (Table 1) and incubated at 45 °C in a water bath for 1 h. After this period, the culture was transferred to a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask and incubated as described above.

2.2.2 Addition of Escherichia coli lysate

A pre-culture of E. coli ATCC 25922 was prepared by suspending two loops of colonies previously grown on Mueller-Hinton agar (MH, Liofilchem, Roseto d. Abruzzi, Italy), in a falcon tube containing 5 mL of MH broth. The suspension was incubated at 37°C for 2 days, at 100 rpm. After incubation, the culture was vortexed and the entire volume used to inoculate a 2 L Erlenmeyer flask containing 1 L of MH culture medium, which was subsequently incubated at 37°C for 3 days, at 100 rpm. After this period, the culture was centrifuged at 3046 g, for 10 min (MEGA STAR 600R VWR-EMBRC, Radnor, United States) to separate the E. coli pellet from the supernatant. The biomass pellet was lyophilized (0.05 mbar and -55°C) for 2 days. A total of 1.5 g of lyophilized E. coli biomass was added per liter to the appropriate actinobacterial growth medium (Table 1) and autoclaved to obtain a lysate of E. coli while ensuring medium sterilization.

2.2.3 Addition of E. coli supernatant

The E. coli supernatant, obtained as previously described, was frozen at -80°C for 24 h, followed by lyophilization (0.08 mbar and -55°C) for a period of 4 days. The lyophilized supernatant was added to the respective growth medium (Table 1), at the concentration of 1.5 g/L, followed by sterilization in an autoclave.

2.2.4 Growth in glucose peptone agar medium supplemented with yeast lysate

The GPA medium with yeast lysate was prepared according to (Georgousaki et al., 2020) and had the following composition (per liter of deionized water): 45 g glucose, 1.5 g yeast lysate and 10 g peptonized milk. Yeast lysate was obtained from Candida albicans ATCC 10231, and was prepared using the same procedure described for the preparation of the E. coli lysate, with C. albicans grown in Sabouraud Dextrose medium (SD, Liofilchem, Roseto d. Abruzzi, Italy) instead of Mueller-Hinton. After lyophilization, 1.5 g/L of the C. albicans biomass was added to the GPA medium, which was then autoclaved to obtain the lysate and ensure medium sterilization.

2.2.5 Addition of Candida albicans supernatant

The C. albicans supernatant was obtained and processed following the same procedure described for E. coli. The lyophilized supernatant was added to the appropriate growth medium (Table 1), at the concentration of 1.5 g/L, followed by autoclaving to ensure sterilization.

2.2.6 Growth in glucose yeast extract malt extract medium

The GYM medium was prepared with the following composition (per liter of deionized water): 4 g glucose, 4 g yeast extract, 10 g malt extract, 1 g peptone, 2 g NaCl, 1 M MOPS (morpholinopropanesulfonic acid; pH 7.2) (Ochi, 1987). The medium was autoclaved before the addition of the MOPS solution to avoid its degradation. The MOPS solution was filter (0.22 µm) sterilized and added to the culture medium after autoclaving.

2.2.7 Addition of N-acetylglucosamine

A solution of N-acetylglucosamine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, United States) was prepared in deionized water at a concentration of 100 mM (Rigali et al., 2008). This solution was filter (0.22 μm) sterilized and added to the appropriate growth medium at a final concentration of 50 mM.

2.2.8 Addition of lanthanum (III) chloride

A solution of lanthanum (III) chloride (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was prepared in deionized water at a concentration of 200 mM (Xu et al., 2018a). This solution was filter (0.22 μm) sterilized and added to the appropriate growth medium, at a final concentration of 2 mM.

2.3 Preparation of crude extracts for bioactivity assays

At the end of the incubation period, cultures were subjected to three sequential centrifugation cycles at 3046 g for 5 min each. The pellet obtained from each actinobacterial culture (that included both biomass and resin) was lyophilized (0.05 mbar and -55 °C) for three days and stored at -20 °C. Lyophilized cultures were extracted twice with 30 mL of an acetone/methanol mixture 1:1 (v/v). The organic layer was dried in a rotary evaporator and the obtained crude extract was weighted and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ≥ 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) to prepare stock solutions at the concentrations of 10, 3 and 1 mg/mL for bioactivity screening.

2.4 Screening of antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity was screened by employing the agar-based disk diffusion method, using five reference microorganisms: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC 25241) and Candida albicans (ATCC 10231). The bacterial strains were grown on MH agar and the yeast C. albicans was grown on SD agar. After growth on solid medium, these microorganisms were suspended in the corresponding broth and the turbidity of the suspensions was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard (OD625 = 0.08−0.13). These standardized suspensions were used to seed MH (for bacteria) or SD (for C. albicans) agar plates, by evenly streaking the plates with a swab dipped in the inoculum cultures. Blank paper disks (6 mm in diameter; Oxoid Limited, Hampshire, UK) were placed on the surface of the inoculated plates and loaded with 15 μL of crude extract at the concentration of 1 mg/mL. The positive control consisted in 15 μL of enrofloxacin (1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for the bacterial strains and 15 μL of nystatin (1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for the yeast, and the negative control consisted in 15 μL of DMSO. The assays were performed in duplicate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, after which the presence of inhibition halos was inspected and the respective diameters measured.

2.5 Screening of anticancer activity

The cytotoxic activity of the actinobacterial extracts was tested in two human cancer cell lines: HepG2 (liver) and T-47D (breast) (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and in a non-cancer cell line: hCMEC/D3 (Human Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial) (kindly donated by Dr. P. O. Courad, INSERM, France). The cell lines were grown in Dulbeco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Biochrom) at 100 IU/mL and 10 mg/mL, respectively, and 0.1% (v/v) amphotericin (GE Healthcare, Little Chafont, United Kingdom). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% of CO2 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, MA, USA). Cell viability was determined by the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. The cells were seeded in 96- well plates at a density of 6.6×104 cells/mL. After 24 h, cells were exposed to extract solutions at a final concentration of 15 µg/mL. Solvent and positive controls consisted in 0.5% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 100 µM staurosporine, respectively. Cell viability was evaluated after 48 h by adding MTT at a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and incubating for 4 h at 37 °C. After this time, the medium was removed and 100 μL of DMSO were added per well, after which the absorbance was read at 570 nm (Synergy HTX, Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA). Each extract was tested each in triplicate in two independent experiments (n = 6). Cellular viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the solvent control.

2.6 Screening of anti-inflammatory activity

The murine RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line was used to study the anti-inflammatory bioactivity of the actinobacterial extracts. Cells were cultured as described before. The cells were seeded in 96- well plates at a density of 3.5x105 cells/mL. After 24 h, cells were exposed to extract solutions at a final concentration of 15 µg/mL and 6 replicates were used per group derived from two independent assays (n = 6). The macrophage inflammation was monitored by two control groups: 0.5% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) without LPS (lipopolysaccharide) and DMSO with 200 µg/mL of LPS. The performed assay allowed inferring both the anti-inflammation and pro-inflammation potential of the actinobacterial extracts. For analyzing the anti- inflammation potential of the extracts, 200 µg/mL of LPS was added to each well along with the extract. In the analysis of pro-inflammation potential, the wells did not contain LPS, only the extract. After 24 h of exposure, 75 µL of the supernatant was removed to a new plate for the determination of nitrites, as proxy for nitric oxide (NO) levels, a mediator of inflammation. 75 µL of Griess reagent (10 mg/mL sulfanilamide; Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA; 1 mg/mL N-(1-Naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, Fluka Analytical, Munich, Germany) were added to the supernatant, the plates incubated with shaking, for 15 min, at room temperature, before reading the absorbance at 562 nm. The cell viability of macrophages was determined by the MTT assay, by adding MTT at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL, followed by incubation for 45 min at 37 °C. Then, the medium was removed and 100 μL of DMSO were added per well, after which the absorbance was read at 510 nm (Synergy HTX, Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.7 Dereplication and molecular network analysis

All extracts were subjected to metabolomic analyses using MS-based dereplication and molecular network analyses (Nothias et al., 2020; Avalon et al., 2022). The extracts were resuspended in methanol at a concentration of 2 mg/mL and used for LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis on a system composed of a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC coupled to a qExactive Focus Mass spectrometer controlled by XCalibur 4.1 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States). The chromatographic step was carried out in an ACE UltraCore 2.5 Super C18 column (75 mm × 2.1 mm, Avantor, Radnor, Pennsylvania). Five microliters of each extract were injected and separated using a gradient from 99.5% eluent A (95% water, 5% methanol, 0.1% formic acid, v/v) and 0.5% eluent B (95% isopropanol, 5% methanol, 0.1% formic acid, v/v) to 10% eluent A and 90% eluent B, over 9.5 min and then maintained for 6 min before returning to initial conditions. The UV absorbance of the eluate was monitored at 254 nm and at Full MS scans, at the resolution of 70,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM) (range of 150–2000 m/z), followed by data dependent MS2 (ddMS2, Discovery mode) at the resolution of 17,500 FWHM (isolation window used was 3.0 amu and normalized collision energy was 35). The raw data obtained from the MS-based dereplication of the extracts was converted to mzML format and submitted to the dereplication workflow of the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking platform (GNPS). Three dereplication steps were used, Insilico Peptidic Natural Product Dereplicator, Dereplicator VarQuest and Dereplicator+, with the default parameters (except ion mass tolerance precursor and fragment ion mass tolerance, which were set at 0.005 Da) (Wang et al., 2016). To support the dereplication analysis, a molecular network was constructed using the default parameters, excluding ion mass precursor tolerance and fragment ion mass tolerance (set to 0.02 Da). The resulting molecular network was visualized with Cytoscape v3.6.1 (Shannon et al., 1971) and searched for clusters of m/z value that were associated with a single extract. The HRESIMS/MS spectra corresponding to such data were annotated to clarify the likely masses of the compounds generating the clusters. The identified putative compound masses were then used for an additional dereplication step by searching the predicted accurate mass (± 5 ppm) against the Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP; dnp.chemnetbase.com) and Natural Products Atlas 2.0 (NPA) (van Santen et al., 2022) databases. When hits from Actinomycetota were obtained, information regarding the biological activity of the compound(s) was retrieved from this database. In addition, to understand the differences between conditions for each strain, comparative analysis was carried out using the XCalibur™ software.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data from anticancer and anti-inflammatory assays were tested for significant differences compared to the solvent control. The significance level was set for all tests at p < 0.05. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to check for normality distribution of data. For parametric data, one-Way ANOVA was applied followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. If statistical test assumptions were not met, data were either square root transformed and re-tested by ANOVA, or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

3 Results

3.1 Bioactive potential of deep-sea actinomycetota grown under OSMAC conditions

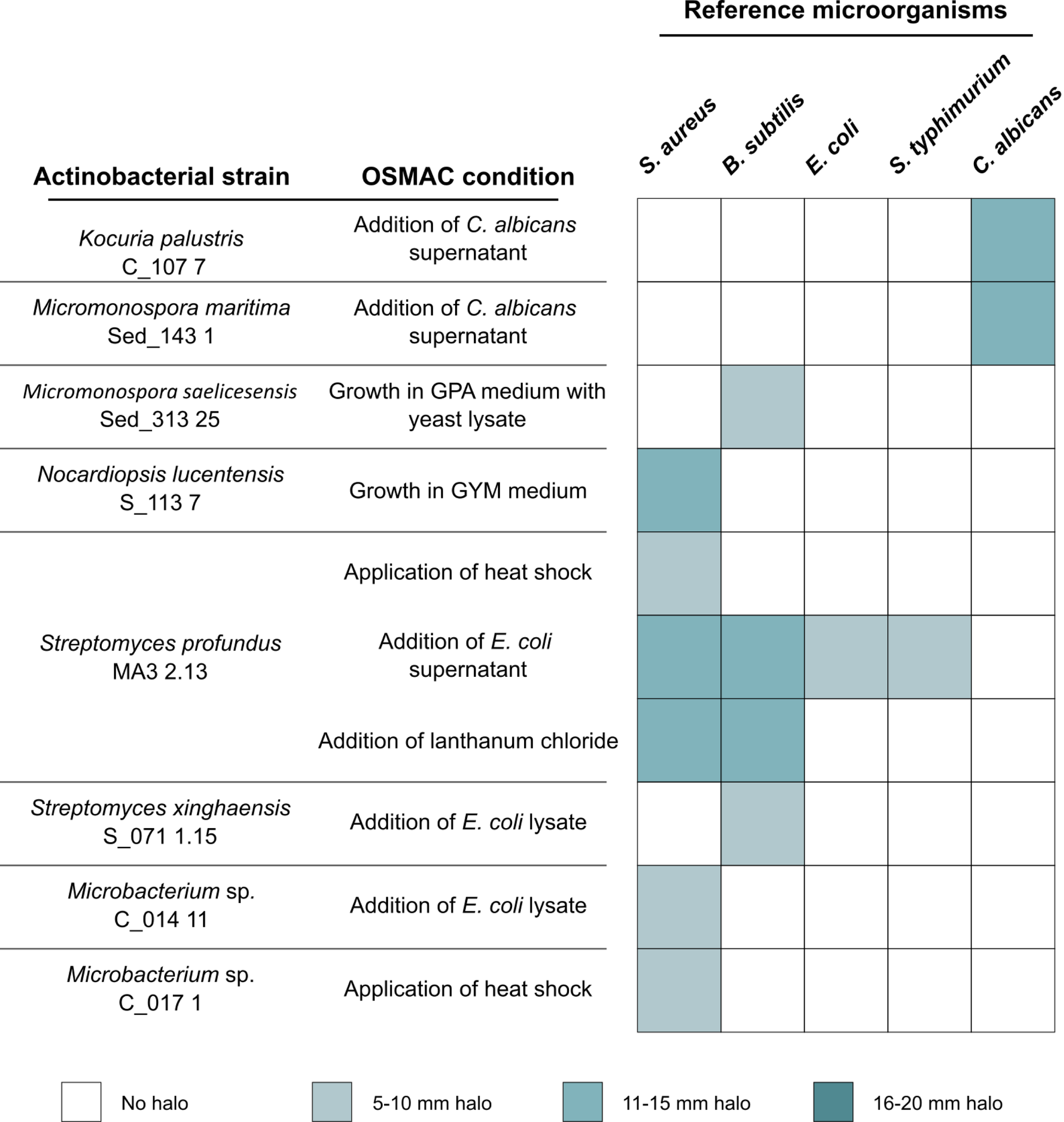

The OSMAC conditions tested in this study led to the detection of 10 actinobacterial extracts capable of inhibiting the growth of at least one of the reference microorganisms tested (Figure 1). Several OSMAC conditions, namely, growth in GYM medium, application of heat shock, addition of E. coli supernatant or lysate and addition of lanthanum (III) chloride, triggered antimicrobial activity against S. aureus. Growing the strains Kocuria palustris C_107 7 and Micromonospora maritima Sed_143 1 in the presence of C. albicans supernatant induced the expression of antifungal activity against this yeast. Four OSMAC conditions - growth in GPA medium supplemented with yeast lysate, addition of E. coli supernatant or lysate and addition of lanthanum (III) chloride to the culture medium - led to activity against B. subtilis. Among all OSMAC conditions tested, only one produced activity against the two Gram-negative reference strains used in this study, E. coli and S. typhimurium, which was observed in the crude extract of Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 grown in the presence of E. coli supernatant.

Figure 1

Actinobacterial extracts resultant from the OSMAC conditions with antimicrobial activity.

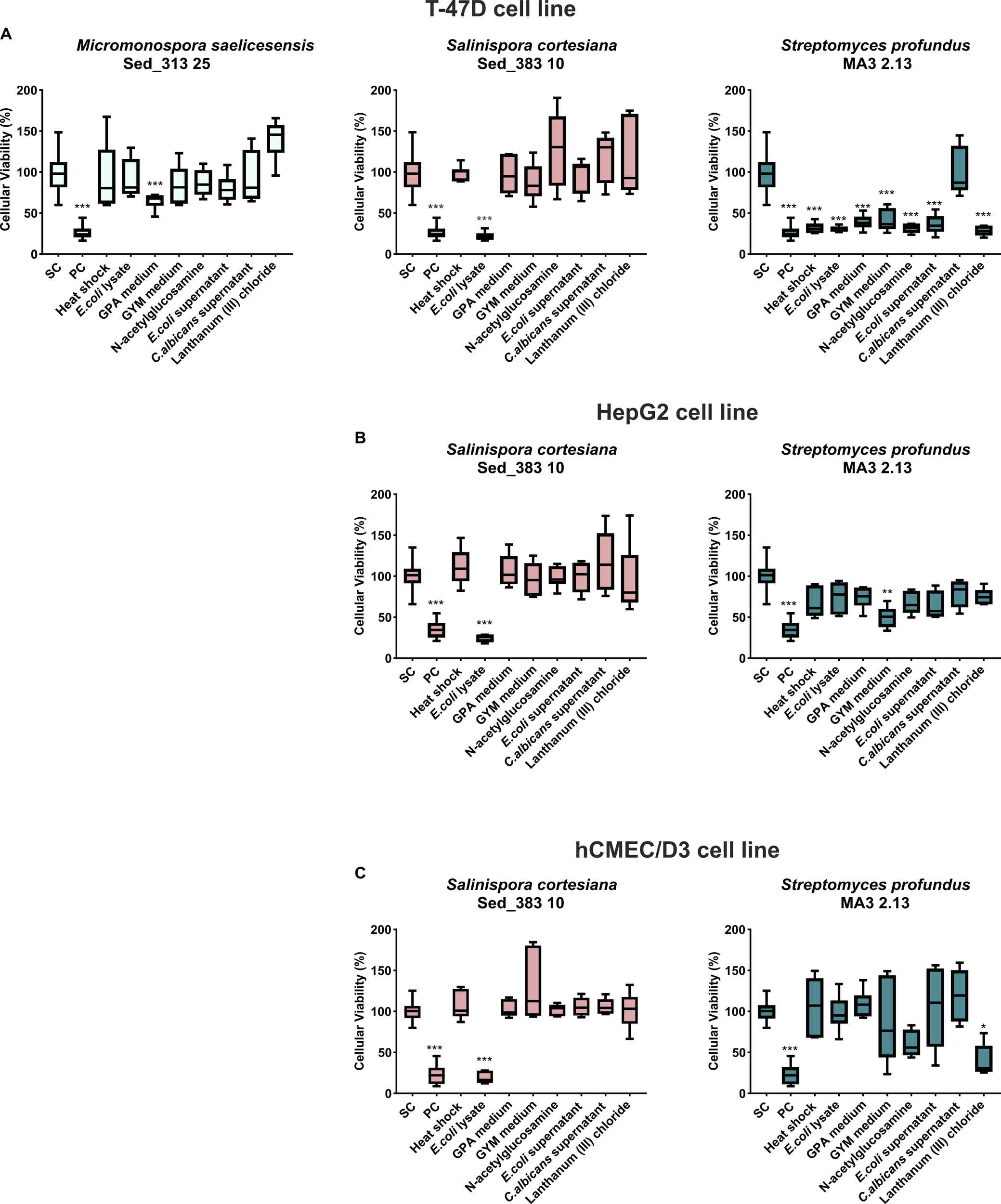

Screening the 80 organic extracts generated in this study showed that 10 exhibited statistically significant cytotoxicity against at least one of the tested human cancer cell lines (HepG2 or T-47D), when compared to the solvent control (Figure 2). Nine extracts reduced the viability of the T-47D cell line by more than 60% (obtained from Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10 grown in the presence of E. coli lysate, and from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 grown under all tested OSMAC conditions, except for the condition addition of C. albicans supernatant), and one extract reduced the viability of this same cell line by more than 35% (Micromonospora saelicesensis strain Sed_313 25 grown in GPA medium) (Figure 2A). For the HepG2 cell line, two extracts reduced its viability, one by approximately 75% (derived from Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10 grown in the presence of E. coli lysate), and another by around 40% (derived from Streptomyces profundus strain MA3 2.13 grown in GYM medium) (Figure 2B). To analyze the specificity of the observed bioactivities towards cancer cells, the crude extracts were also tested on a non-carcinogenic endothelial cell line, hCMEC/D3. Two extracts demonstrated high cytotoxicity on hCMEC/D3 cells – obtained from Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10 grown in the presence of E. coli lysate, and from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 supplemented with GYM medium (Figure 2C) – revealing general cytotoxicity. In contrast, some extracts demonstrated selective cytotoxicity, with significant reduction of the viability of cancer cells, but not of the non-cancer cell line. Streptomyces profundus strain MA3 2.13 under the OSMAC conditions application of heat shock, addition of E. coli lysate, growth in GPA medium supplemented with yeast lysate, or addition of E. coli supernatant, revealed a promising profile, with high cytotoxic activity in breast cancer cells (T-47D) but without significant activity in normal hCMEC/D3 cells. In addition, this same strain grown in GYM medium showed the most promising bioactivity, since its extract reduced the cytotoxicity in both cancer cell lines (breast and liver cancer), but not in the non-cancer cell line (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Actinobacterial extracts resultant from the OSMAC conditions with cytotoxic activity. The effects on the cellular viability of (A) breast carcinoma T47D, (B) liver cancer HepG2, and (C) Human Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial hCMEC/D3, a nontumor cell line, are shown after 48 h of exposure. PC and SC denote positive and solvent controls, respectively. The x- axis labels indicate the OSMAC conditions under study. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation from two independent assays conducted in triplicate. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001).

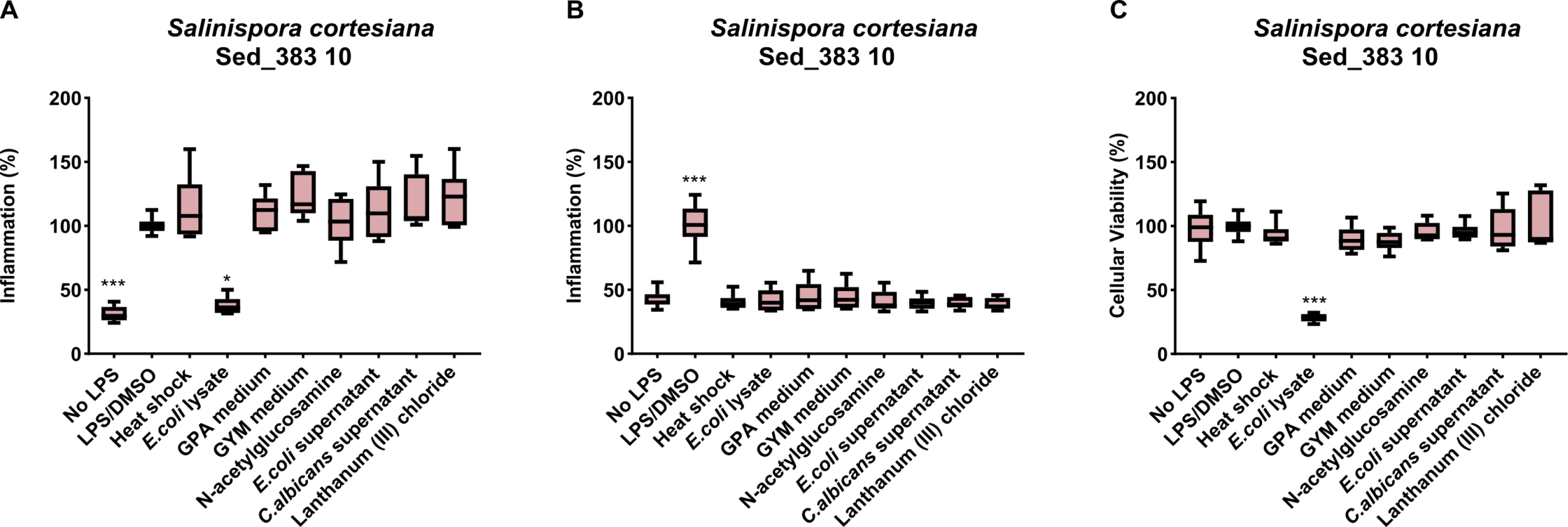

The 80 organic extracts were also screened for their anti-inflammatory activity (Figure 3). The results showed that the extract obtained from Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10 grown in the presence of E. coli lysate had an anti-inflammatory effect, being able to reduce inflammation in about 60% (Figure 3A). However, this extract also had strong cytotoxic activity on the murine RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line (>70%), as shown by the MTT assay (Figure 3C). As such, the anti-inflammatory activity observed for this extract was considered a false positive, leaving no extracts with confirmed activity.

Figure 3

Actinobacterial extracts resultant from the OSMAC conditions with anti- or pro-inflammatory activity. The graphs show the extracts capable of decreasing ((A) – anti-inflammation) or increasing ((B) - pro-inflammation) nitric oxide. (C) Cytotoxic activity of Salinispora cortesiana strain Sed_383 demonstrated by MTT assay. (*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.0001). The x- axis labels indicate the OSMAC conditions under study.

No bioactivity was observed in the controls used in this study, i.e., Actinomycetota strains grown in their standard medium (M1 or MB; Table 1), without OSMAC conditions, or in the uninoculated controls, indicating that the applied OSMAC strategies were responsible for the observed bioactivities.

To determine whether the observed activities in the tested extracts could be attributed to known compounds or potentially novel secondary metabolites, a comprehensive dereplication process was performed on all 80 extracts using LC-HRESIMS/MS. Moreover, this analysis facilitated the assessment of differences among the OSMAC strategies used, by analyzing the raw data in Xcalibur™. The chemical profile analysis showed the presence of several masses that did not present a match in the database and therefore may be associated with potential new compounds (Supplementary Table S1).

Furthermore, 15 extracts showing strong antimicrobial or anticancer activities were selected for dereplication analysis using the GNPS platform to understand whether these activities could be due to known compounds or potentially new metabolites. The strain Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13, grown in GYM medium, showed promising results, as it exhibited cytotoxicity against the T-47D and HepG2 tumor lines, but showed no activity against the non-tumor cell line. The cyclic siderophore nocardamine, identified in the extract and known for its anticancer properties, could explain this activity (He et al., 2024). For the extract resulting from Micromonospora maritima Sed_143 1 grown in the presence of C. albicans supernatant, dereplication did not reveal any compound that could account for the observed antimicrobial activity. In contrast, the GNPS analysis of the remaining extracts indicated the presence of already known bioactive natural products in most of the active extracts, such as aldgamycin P (Wang et al., 2019), arromycin (Wong et al., 2012), etamycin (Sheehan et al., 1958) and nocardamine (Kalinovskaya et al., 2011) (Supplementary Table S2). Although these compounds are primarily known for their antimicrobial activity, some of the extracts displayed anticancer effects that cannot be explained by the dereplication results. Similarly, the dereplication results did not shed light on the cytotoxic activity exhibited by the strain Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10 grown with E. coli lysate.

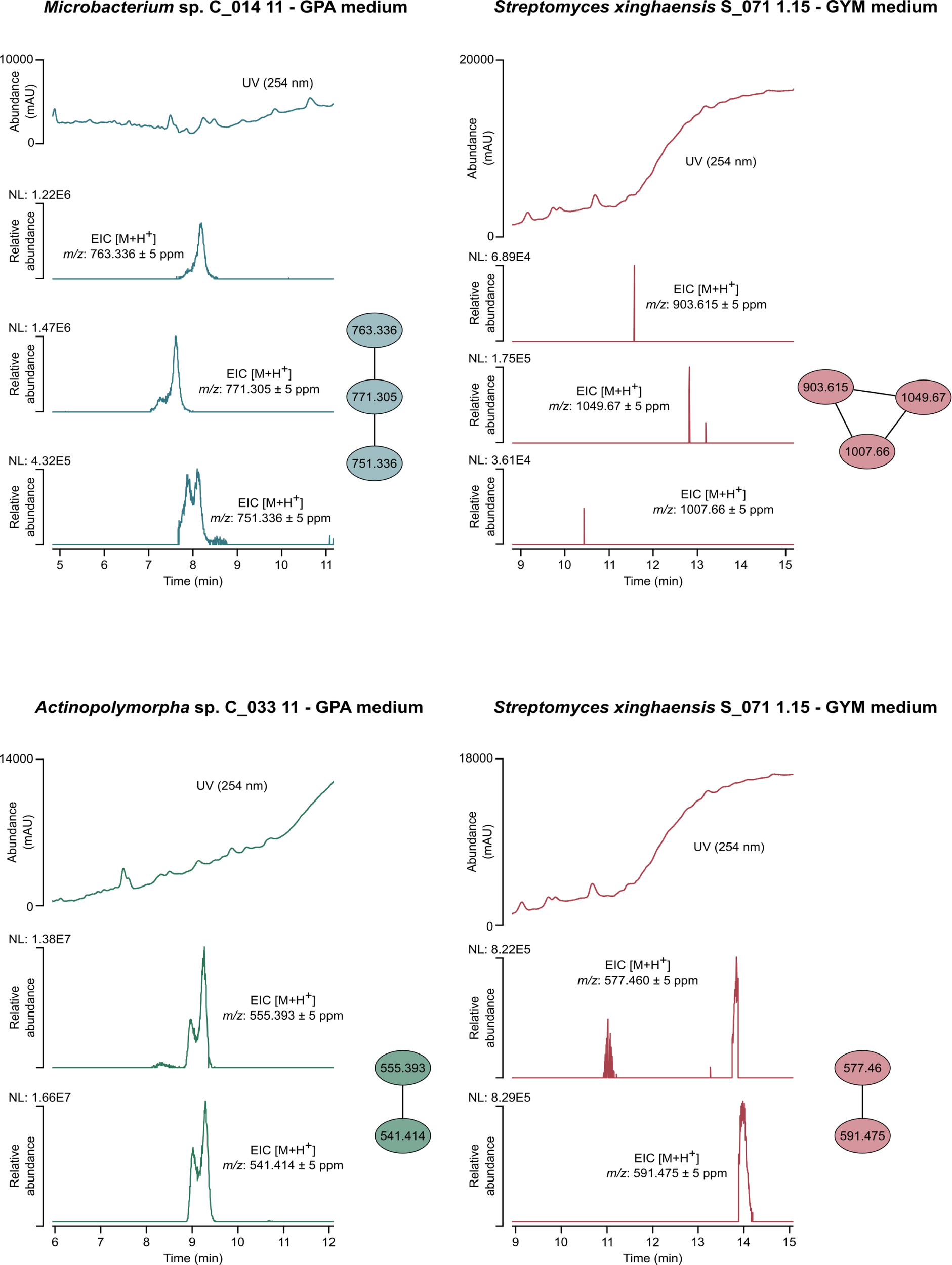

Using the MS/MS data of all the extracts under study, a molecular network was also developed in Cytoscape. Clusters observed in a single extract were used as an additional criterion to increase the likelihood that a cluster might correspond to a novel compound. Two of these clusters were identified in the extract derived from Streptomyces xinghaensis strain S_071 1.15 cultured in GYM medium - m/z 577.46, m/z 591.475; and m/z 903.615, m/z 1007.66, m/z 1049.67, the latter being detected in residual abundances. Additionally, one cluster was detected in the extract of Microbacterium sp. C_014 11 - m/z 763.336, m/z 771.305, m/z 751.336, and another cluster in the extract of Actinopolymorpha rutila C_033 11 - m/z 555.393, m/z 541.414, both grown in GPA medium (Figure 4). Notably, some of the observed mass peaks in these clusters did not exhibit any known association with compounds typically produced by Actinomycetota, a finding particularly evident in the Microbacterium and Actinopolymorpha extracts (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Molecular network developed with MS/MS data of the extracts from Microbacterium sp. C_014 11 grown in GPA medium, Actinopolymorpha rutila C_033 11 grown in GPA medium and Streptomyces xinghaensis S_071 1.15 grown in GYM medium. The numbers within the nodes correspond to the mass of each fragment. For each cluster, the respective UV chromatogram and extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) are shown.

4 Discussion

This study demonstrates that applying multiple OSMAC conditions to deep-sea actinobacterial isolates results in marked diversification of bioactivity and metabolite profiles. From the extracts screened, 11 showed antimicrobial activity and 9 exhibited cytotoxic effects. Metabolomic analysis further revealed features corresponding to compounds not yet reported in the literature, highlighting the effectiveness of the OSMAC approach in activating silent biosynthetic potential.

The most common strategy to influence secondary metabolism and activate silent BGCs is the use of nutrient-rich media with diverse complex nutrient sources, which modulate metabolic pathways and metabolite profiles (Schwarz et al., 2021). In the present study, two OSMAC conditions consisted in growing the actinobacterial isolates in two nutrient-rich culture media different from their original isolation medium - GPA and GYM. The GPA medium has glucose as the main carbon source, but also contains peptonized milk and a C. albicans lysate as a source of nitrogen, whereas the GYM medium has glucose and malt extract as carbon sources, and yeast extract as nitrogen source. The selection of these culture media was based on previous studies that reported promising results in activating secondary metabolism under OSMAC conditions (Kurtböke et al., 2015; Georgousaki et al., 2020; Schwarz et al., 2021). In this study, two extracts showed bioactivity when using GPA as the growth medium. One of these extracts was derived from Micromonospora saelicesensis Sed_313 25, which demonstrated antimicrobial activity against B. subtilis and anticancer activity in the cell line T-47D, and the other extract was obtained from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 that also exhibited anticancer activity in the T-47D cell line. Similarly, two extracts also showed bioactivity when the strains were grown in GYM medium: one extract from Nocardiopsis lucentensis S_113 7, which showed activity against S. aureus, and another extract from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 that exhibited activity against the two cancer cell lines tested. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting bioactive compound production in GYM and GPA media. For example, Streptomyces sp. USC-633 produced the antitumor compound lavanducyanin when cultivated in GYM medium (Kurtböke et al., 2015), and Streptomyces sp. CA-284376 produced the antibiotic sulfomycin I cultivated in GPA medium (Trabelsi et al., 2016). In the dereplication analysis, we detected several antibiotics and cyclic peptides, including flambamycin (Ninet et al., 1974), stenothricin (Hasenböhler et al., 1974), aldgamycin P (Wang et al., 2019), langkolide (Helaly et al., 2012) and nocardamine (Kalinovskaya et al., 2011). Most of these molecules, reported mainly from Streptomyces strains, have known antimicrobial activities, while langkolide has also been described for its anticancer properties. These hits may thus explain the antimicrobial and anticancer activities observed in some of our extracts.

Another OSMAC approach used in our study was the addition of GlcNAc to the culture medium. This aminosugar is a building block of the bacterial peptidoglycan layer and the main monomer of the abundant natural polymer, chitin, which is the main component of fungal cell walls. Exposure to GlcNAc results in the intracellular accumulation of glucosamine-6-phosphate, which binds to the global regulator DasR (DNA binding protein) and inhibits its DNA-binding activity, thereby relieving repression of antibiotic biosynthetic genes (Abdelmohsen et al., 2015). It was shown in previous studies that GlcNAc had a stimulatory effect on antibiotic production by S. clavuligerus, S. collinus, S. griseus, S. hygroscopicus and S. venezuelae species (Rigali et al., 2008). In addition, GlcNAc appears to function as an important sensory molecule for the initiation of secondary metabolism, probably because its presence in the culture medium may be confused with the presence of a microorganism (Baral et al., 2018). Curiously, in our study, the addition of GlcNAc to the culture medium induced anticancer activity (against the T-47D cell line) in Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13, with no antimicrobial activity being induced in any of the tested strains. In line with this result, Xu et al (Dashti et al., 2017). reported that the addition of GlcNAc to cultures of Rhodococcus sp. RV157 induced the production of surfactin 17, a lipopeptide with reported antitumor properties, further supporting the role of GlcNAc in promoting anticancer metabolite production. Dereplication revealed the presence of etamycin, a cyclic peptide antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces sp., active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Sheehan et al., 1958). In our study, no antimicrobial activity was observed in the corresponding extract, which instead showed anticancer activity, indicating that etamycin does not explain the bioactivity detected.

An additional OSMAC condition tested was the addition of lanthanum (III) chloride to the culture medium. The rare earth salt lanthanum (III) chloride is a chemical elicitor that has been shown effective in inducing antifungal or antibacterial activities in strains that do not show such activities under normal cultivation conditions (Xu et al., 2018a). A previous study demonstrated that lanthanum (III) chloride acts as a chemical elicitor in S. coelicolor, leading to the up-regulation of nine genes and the production of several unidentified metabolites, although the mechanism responsible for this response remains unknown (Abdelmohsen et al., 2015). The use of this approach led to the identification of one extract from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 that exhibited antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and B. subtilis, as well as cytotoxic activity. The inhibition of S. aureus growth is in line with the results obtained in a previous study, in which the employment of the same strategy (use of lanthanum (III) chloride) led to the discovery of three new angucyclines (A-C) with antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the strain Nocardiopsis HB-J37 (Xu et al., 2018b). An additional study also demonstrated that the production of antimycin-type metabolites can be activated by lanthanum (III) chloride in strain R818 (Xu et al., 2018a). In our dereplication analysis, compounds potentially explaining the observed bioactivities were detected, including meilingmycin (Sun et al., 2003) and arromycin (Wong et al., 2012), both reported as products of Streptomyces strains.

The application of heat shock was another approach used in this work, since this strategy was shown before to induce the production of new secondary metabolites in Streptomyces species (Baral et al., 2018; Saito et al., 2020). Previous studies have demonstrated that heat-shock induced chaperones may contribute to the organization and assembly of multiple enzyme complexes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis (Doull et al., 1994). The use of this strategy resulted in two active extracts: one from Streptomyces profundus strain MA3 2.13, which demonstrated activity against S. aureus and reduced 70% of the viability of the T-47D cell line, and another from Microbacterium sp. C_017 1 that exhibited activity against S. aureus. Consistent with our findings, Doull and colleagues (Doull et al., 1993) reported that the application of a heat shock triggered the production of the polyketide-derived antibiotic jadomycin in Streptomyces venezuelae, highlighting the potential of this approach to activate otherwise silent biosynthetic pathways. For this condition, dereplication analysis showed the presence of two antibiotics, monensin M2 (Oliynyk et al., 2003) and dihydrostreptomycin (Kavanagh et al., 1960), that can justify the observed antimicrobial activities.

The elicitation of cryptic actinobacterial BGCs can also be performed by adding microbial lysates to the culture medium (Abdelmohsen et al., 2015; Verma et al., 2018). In this process, dead cells of the inducer strain are used to trigger the production of bioactive metabolites by the producer strain. Microbial lysates can act as chemical elicitors because they contain cell-wall fragments, metabolites and stress-related molecules that are sensed by the receiving strain. In Streptomyces, such cues can trigger global stress or nutrient-response pathways, leading to metabolic reprogramming and activation of otherwise silent biosynthetic gene clusters (Abdelmohsen et al., 2015). Consistent with this, the addition of E. coli lysate has been shown to alter central metabolic routes, including glycolysis and amino-acid–related pathways, which can redirect cellular resources towards secondary-metabolite production (Miguez et al., 2021). In this work, one of the OSMAC conditions applied consisted in adding an E. coli lysate to the culture medium, which resulted in the induction of bioactivity in 4 isolates: (i) Streptomyces xinghaensis S_071 1.15, which exhibited activity against B. subtilis, (ii) Microbacterium C_014 11 that was active against S. aureus, (iii) Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 that showed selective activity against the cancer cell line T-47D, and (iv) Salinispora cortesiana Sed_383 10, which demonstrated cytotoxic activity. This extract also showed a false positive result in the anti-inflammatory assay, as it reduced inflammation but demonstrated cytotoxicity to the RAW 264.7 cell line. Less macrophages as a result of cytotoxicity, will lead to lower NO production. For this reason, it is important to always perform anti-inflammatory assays together with cytotoxic evaluations (Regueiras et al., 2021). Thus, the employment of this OSMAC strategy revealed to be efficient in inducing several bioactivities in the tested Actinomycetota strains. In addition, the extract from the control condition, prepared without actinobacterial inoculum, showed activity against C. albicans, indicating that the E. coli lysate itself has activity against this yeast. Supporting the role of bacterial components as inducers, a similar effect was previously observed in Streptomyces sp. A3, where treatment with dead B. subtilis cells enhanced the production of undecylprodigiosin, an antibiotic with immunosuppressive properties. The dereplication analysis of the extracts that showed activity in this condition revealed the presence of several antibiotics, lipiarmycin (Coronelli et al., 1975), concanamycin (Kinashi et al., 1984), piericidin (Zhou and Fenical, 2016) and antibiotic BE 14106 (Kojiri et al., 1992), all reported from various Streptomyces strains, except for Lipiarmycin, that was originally isolated from a Actinoplannes sp. The presence of these compounds, known for their antimicrobial or cytotoxic properties, is consistent with the activities observed in our extracts, suggesting that the bioactivity may be explained, at least in part, by these known metabolites.

Concerning the two other OSMAC conditions tested, i.e., addition to the culture medium of the supernatant resulting from E. coli or C. albicans growth, the rationale behind their choice was based on the fact that the inducer species can release into the supernatant compounds that can be perceived by the producer strain as a threat, or that can induce stress to it, triggering the production of new secondary metabolites. For the approach where E. coli supernatant was used, one extract obtained from Streptomyces profundus MA3 2.13 showed activity against the T-47D cell line and the microorganisms B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli and S. typhimurium, exhibiting antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. For the approach employing the supernatant of C. albicans, two active extracts were identified. These extracts, derived from the strains Kocuria palustris C_107 7 and Micromonospora maritima Sed_143 1, demonstrated antimicrobial activity against C. albicans. These results indicate that the addition to the culture medium of E. coli or C. albicans supernatant can be an effective strategy for triggering, respectively, antibacterial and antifungal activities in actinobacterial strains. This is consistent with observations in S. coelicolor, where the addition of E. coli culture supernatant stimulated the production of undecylprodiogiosin, a compound with antibacterial properties (Kim et al., 2021). In the dereplication analysis, we detected compounds potentially responsible for the observed activities, including antibiotic AB-023b (Bortolo et al., 1993), furaquinocin C (Ishibashi et al., 1991) and flavofungin (Uri and Békési, 1958), all previously reported as products of Streptomyces strains.

To further investigate whether the extracts obtained under different OSMAC conditions could contain potentially novel metabolites, comparative analysis of the metabolite profiles was performed using XCalibur™ across all tested conditions for each of the strains in the study. The masses obtained from these analyses were dereplicated in the DNP and NPA databases and a molecular network analysis was carried out. According to the dereplication analysis (Supplementary Table S1) and metabolic profile of all extracts (including control samples), it became evident that some extracts might contain previously undiscovered compounds. For some of these extracts no bioactivity was observed, which may indicate that the potential new compounds may have other bioactivities not tested in this work. In the present study, the molecular network analysis confirmed the presence of four clusters probably corresponding to new NP: one in the extract of Microbacterium C_014 11 grown in GPA medium supplemented with yeast extract, one in the extract of Actinopolymorpha rutila C_033 11 grown in the same medium, and two in the extract of Streptomyces xinghaensis grown in GYM medium (Figure 4). These extracts will be prioritized in future studies for compound isolation and structural elucidation, in order to assess the novelty and potential bioactivity of the detected metabolites.

Despite these promising results, it should be noted that this study was designed as an exploratory screening based on crude extracts. Bioactivity assays were performed at a single concentration, and MIC or IC50 values were not determined. In addition, metabolite annotation relied on untargeted metabolomic analyses and database-based dereplication, which inherently entails different levels of confidence. These limitations are intrinsic to early-stage OSMAC screenings and highlight the need for subsequent compound isolation, dose–response evaluation, and structural confirmation to fully validate bioactivity and novelty.

5 Conclusion

This study underscores the effectiveness of the OSMAC approach in stimulating the production of secondary metabolites with antimicrobial and anticancer activities in deep-sea Actinomycetota and highlights its potential for uncovering new bioactive molecules. The identification of several bioactive extracts supports the potential of these microorganisms as a source of early-stage leads for antimicrobial discovery and oncology-oriented drug development. Among the strategies tested, the addition of E. coli lysate or supernatant to the culture medium proved particularly effective, inducing a broad range of bioactivities.

It should be noted that this work was conducted within an exploratory screening framework, based on crude extracts and single-dose bioassays. While the objective of demonstrating OSMAC-induced modulation of bioactivity and metabolite profiles was clearly achieved, further quantitative reinforcement, such as dose–response analyses and expanded replication, will be required to fully validate and prioritize individual bioactive compounds.

Future work will prioritize a bioactivity/mass-guided fractionation pipeline, combining LC-HRESIMS/MS and NMR analyses to enable structural elucidation of the active compounds, followed by IC50 determination and expanded bioactivity profiling. Insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying OSMAC-induced activation may be obtained by combining genome mining approaches (such as antiSMASH) with transcriptomic analyses and RT-qPCR of selected biosynthetic gene clusters, which will enable the evaluation of regulatory responses to specific elicitation conditions.

Our findings highlight the importance of continued bioprospecting of deep-sea Actinomycetota using the OSMAC approach. The results obtained in this study leave open the possibility of discovering, isolating, and characterizing one or more new compounds with pharmacological/biotechnological relevance from these deep-sea Actinomycetota.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

SC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. IR: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AB-H: Resources, Writing – review & editing. PL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RU: Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. SC was financially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (FCT) under the Ph.D. fellowship 2023.01541.BD. AB-H was financially supported by the Oceanic Observatory of Madeira Project (M1420-01-0145-FEDER-000001-Observatório Oceânico da Madeira-OOM) and FCT through the strategic project [UIDB/04292/2020] granted to MARE. The M150-BIODIAZ cruise was funded by the DFG-Senatskommission für Ozeanographie, and the DEEP-ML (MAR2020-P06M02-0535P/Regional Government of Madeira) was funded through the MAR 2020 operational program under the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. This work was funded by the project ATLANTIDA II (ref. NORTE2030-FEDER-01799200), co-financed by the European Union through the NORTE 2030 Regional Program and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and by national funds through FCT, and by the European Commission’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, within the scope of UID/04423/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/04423/2025), UID/PRR/04423/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/04423/2025), and LA/P/0101/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0101/2020). Additional financial support was obtained from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement no. 952374, and NORTE2030-FEDER-01796500, project co-funded by the European Union through the NORTE 2030 Regional Program.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author MC declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2026.1754764/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdelmohsen U. R. Grkovic T. Balasubramanian S. Kamel M. S. Quinn R. J. Hentschel U. (2015). Elicitation of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. Biotechnol. advances.33, 798–811. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.06.003

2

Avalon N. E. Murray A. E. Baker B. J. (2022). Integrated metabolomic–genomic workflows accelerate microbial natural product discovery. Analytical Chem.94, 11959–11966. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c02245

3

Baral B. Akhgari A. Metsä-Ketelä M. (2018). Activation of microbial secondary metabolic pathways: Avenues and challenges. Synthetic Syst. Biotechnol.3, 163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2018.09.001

4

Bortolo R. Spera S. Guglielmetti G. Cassani G. (1993). Ab023, novel polyene antibiotics II. Isolation and structure determination. J. Antibiotics.46, 255–264. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.255

5

Braga-Henriques A. Buhl-Mortensen P. Tokat E. Martins A. Silva T. Jakobsen J. et al . (2022). Benthic community zonation from mesophotic to deep sea: Description of first deep-water kelp forest and coral gardens in the Madeira archipelago (central NE Atlantic). Front. Mar. Science.9, 973364. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.973364

6

Coronelli C. White R. Lancini G. Parenti F. (1975). Lipiarmycin, a new antibiotic from Actinoplanes II. Isolation, chemical, biological and biochemical characterization. J. antibiotics.28, 253–259. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.253

7

Covington B. C. Xu F. Seyedsayamdost M. R. (2021). A natural product chemist's guide to unlocking silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem.90, 763–788. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-081420-102432

8

Dashti Y. Grkovic T. Abdelmohsen U. R. Hentschel U. Quinn R. J. (2017). Actinomycete metabolome induction/suppression with N-acetylglucosamine. J. Natural products.80, 828–836. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00673

9

Doull J. L. Ayer S. W. Singh A. K. Thibault P. (1993). Production of a novel polyketide antibiotic, jadomycin B, by Streptomyces Venezuelae following heat shock. J. antibiotics.46, 869–871. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.869

10

Doull J. L. Singh A. K. Hoare M. Ayer S. W. (1994). Conditions for the production of jadomycin B by Streptomyces Venezuelae ISP5230: effects of heat shock, ethanol treatment and phage infection. J. Ind. Microbiol.13, 120–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01584109

11

George K. Arndt H. Wehrmann A. Baptista L. Berning B. Bruhn M. et al . (2018). Controls in benthic and pelagic BIODIversity of the AZores BIODIAZ. METEOR-Berichte. 150, 31–27 doi: 10.2312/cr_m150

12

Georgousaki K. Tsafantakis N. Gumeni S. Gonzalez I. Mackenzie T. A. Reyes F. et al . (2020). Screening for tyrosinase inhibitors from actinomycetes; identification of trichostatin derivatives from Streptomyces sp. CA-129531 and scale up production in bioreactor. Bioorganic Medicinal Chem. Letters.30, 126952. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.126952

13

Hasenböhler A. Kneifel H. König W. Zähner H. Zeiler H.-J. (1974). Metabolic products of microorganisms: 134. Stenothricin, a new inhibitor of the bacterial cell wall synthesis. Arch. Microbiol.99, 307–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00696245

14

He H.-P. Zhao M.-Z. Jiao W.-H. Liu Z.-Q. Zeng X.-H. Li Q.-L. et al . (2024). Nocardamine mitigates cellular dysfunction induced by oxidative stress in periodontal ligament stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther.15, 247. doi: 10.1186/s13287-024-03812-2

15

Helaly S. E. Kulik A. Zinecker H. Ramachandaran K. Tan G. Y. A. Imhoff J. F. et al . (2012). Langkolide, a 32-membered macrolactone antibiotic produced by Streptomyces sp. acta 3062. J. Natural Products.75, 1018–1024. doi: 10.1021/np200580g

16

Ishibashi M. Funayama S. Anraku Y. Komiyama K. Omura S. (1991). Novel antibiotics, furaquinocins C, D, E, F, G and H. J. Antibiotics44, 390–395. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.390

17

Kalinovskaya N. I. Romanenko L. A. Irisawa T. Ermakova S. P. Kalinovsky A. I. (2011). Marine isolate Citricoccus sp. KMM 3890 as a source of a cyclic siderophore nocardamine with antitumor activity. Microbiological Res.166, 654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.01.004

18

Kavanagh F. Grinnan E. Allanson E. Tunin D. (1960). Dihydrostreptomycin produced by direct fermentation. Appl. Microbiol.8, 160–162. doi: 10.1128/am.8.3.160-162.1960

19

Kim J. H. Lee N. Hwang S. Kim W. Lee Y. Cho S. et al . (2021). Discovery of novel secondary metabolites encoded in actinomycete genomes through coculture. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol.48, kuaa001. doi: 10.1093/jimb/kuaa001

20

Kinashi H. Someno K. Sakaguchi K. (1984). Isolation and characterization of concanamycins A, B and C. J. antibiotics37, 1333–1343. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1333

21

Kojiri K. Nakajima S. Suzuki H. Kondo H. Suda H. (1992). A new macrocyclic lactam antibiotic, BE-14106 I. Taxonomy, isolation, biological activity and structural elucidation. J. Antibiotics.45, 868–874. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.868

22

Kurtböke Dİ Grkovic T. Quinn R. J. (2015). Marine actinomycetes in biodiscovery. Springer Handb. Mar. Biotechnol., 663–676. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-53971-8_27

23

Miguez A. M. Zhang Y. Piorino F. Styczynski M. P. (2021). Metabolic dynamics in Escherichia coli-based cell-free systems. ACS synthetic Biol.10, 2252–2265. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00167

24

Nair R. Roy I. Bucke C. Keshavarz T. (2009). Quantitative PCR study on the mode of action of oligosaccharide elicitors on penicillin G production by Penicillium chrysogenum. J. Appl. Microbiol.107, 1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04293.x

25

Ninet L. Benazet F. Charpentie Y. Dubost M. Florent J. Lunel J. et al . (1974). Flambamycin, a new antibiotic from Streptomyces hygroscopicus DS 23 230. Experientia.30, 1270–1272. doi: 10.1007/BF01945179

26

Nothias L.-F. Petras D. Schmid R. Dührkop K. Rainer J. Sarvepalli A. et al . (2020). Feature-based molecular networking in the GNPS analysis environment. Nat. Methods17, 905–908. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0933-6

27

Ochi K. (1987). Metabolic initiation of differentiation and secondary metabolism by Streptomyces griseus: significance of the stringent response (ppGpp) and GTP content in relation to A factor. J. bacteriology.169, 3608–3616. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3608-3616.1987

28

Oliynyk M. Stark C. B. Bhatt A. Jones M. A. Hughes-Thomas Z. A. Wilkinson C. et al . (2003). Analysis of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyether antibiotic monensin in Streptomyces cinnamonensis and evidence for the role of monB and monC genes in oxidative cyclization. Mol. Microbiol.49, 1179–1190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03571.x

29

Palma Esposito F. Giugliano R. Della Sala G. Vitale G. A. Buonocore C. Ausuri J. et al . (2021). Combining OSMAC approach and untargeted metabolomics for the identification of new glycolipids with potent antiviral activity produced by a marine Rhodococcus. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 9055. doi: 10.3390/ijms22169055

30

Ragozzino C. Casella V. Coppola A. Scarpato S. Buonocore C. Consiglio A. et al . (2025). Last decade insights in exploiting marine microorganisms as sources of new bioactive natural products. Mar. Drugs23, 116. doi: 10.3390/md23030116

31

Regueiras A. Huguet Á Conde T. Couto D. Domingues P. Domingues M. R. et al . (2021). Potential anti-obesity, anti-steatosis, and anti-inflammatory properties of extracts from the microalgae chlorella vulgaris and chlorococcum amblystomatis under different growth conditions. Mar. Drugs20, 9. doi: 10.3390/md20010009

32

Rigali S. Titgemeyer F. Barends S. Mulder S. Thomae A. W. Hopwood D. A. et al . (2008). Feast or famine: the global regulator DasR links nutrient stress to antibiotic production by Streptomyces. EMBO Rep.9, 670–675. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.83

33

Romano S. Jackson S. A. Patry S. Dobson A. D. (2018). Extending the “one strain many compounds”(OSMAC) principle to marine microorganisms. Mar. Drugs16, 244. doi: 10.3390/md16070244

34

Saito S. Kato W. Ikeda H. Katsuyama Y. Ohnishi Y. Imoto M. (2020). Discovery of “heat shock metabolites” produced by thermotolerant actinomycetes in high-temperature culture. J. antibiotics.73, 203–210. doi: 10.1038/s41429-020-0279-4

35

Schwarz J. Hubmann G. Rosenthal K. Lütz S. (2021). Triaging of culture conditions for enhanced secondary metabolite diversity from different bacteria. Biomolecules.11, 193. doi: 10.3390/biom11020193

36

Shannon P. Markiel A. Ozier O. Baliga N. S. Wang J. T. Ramage D. et al . (1971). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models. Genome Res.13, 426. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

37

Sheehan J. C. Zachau H. G. Lawson W. B. (1958). The structure of etamycin. J. Am. Chem. Society.80, 3349–3355. doi: 10.1021/ja01546a039

38

Sun Y. Zhou X. Tu G. Deng Z. (2003). Identification of a gene cluster encoding meilingmycin biosynthesis among multiple polyketide synthase contigs isolated from Streptomyces nanchangensis NS3226. Arch. Microbiol.180, 101–107. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0564-1

39

Tawfike A. Attia E. Z. Desoukey S. Y. Hajjar D. Makki A. A. Schupp P. J. et al . (2019). New bioactive metabolites from the elicited marine sponge-derived bacterium Actinokineospora spheciospongiae sp. nov. AMB Express.9, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0730-0

40

Trabelsi I. Oves D. Magan B. G. Manteca A. Nour O. (2016). Isolation, characterization and antimicrobial activities of actinomycetes isolated from a Tunisian saline wetland. J. Microbial Biochem. Technology.8, 465–473. doi: 10.4172/1948-5948.1000326

41

ul Hassan S. S. Shaikh A. L. (2017). Marine actinobacteria as a drug treasure house. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy.87, 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.086

42

Uri J. Békési I. (1958). Flavofungin, a new crystalline antifungal antibiotic: origin and biological properties. Nature.181, 908. doi: 10.1038/181908a0

43

van Santen J. A. Poynton E. F. Iskakova D. McMann E. Alsup T. A. Clark T. N. et al . (2022). The Natural Products Atlas 2.0: a database of microbially-derived natural products. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D1317–D1D23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab941

44

Verma E. Chakraborty S. Tiwari B. Mishra A. K. (2018). “ Antimicrobial compounds from actinobacteria: synthetic pathways and applications,” in New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 277–295.

45

Wang M. Carver J. J. Phelan V. V. Sanchez L. M. Garg N. Peng Y. et al . (2016). Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol.34, 828–837. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3597

46

Wang L. Yu S.-Y. Xu D.-D. Zhao C. Huang S.-X. Ma Y.-T. (2019). Macrolides from soil-derived Streptomyces sp. KIB-K1 and their antimicrobial activities. Natural Product Res. Dev.31, 1764–1771. doi: 10.16333/j.1001-6880.2019.10.014

47

Wong W. R. Oliver A. G. Linington R. G. (2012). Development of antibiotic activity profile screening for the classification and discovery of natural product antibiotics. Chem. Biol.19, 1483–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.09.014

48

Xu D. Han L. Li C. Cao Q. Zhu D. Barrett N. H. et al . (2018a). Bioprospecting deep-sea actinobacteria for novel anti-infective natural products. Front. Microbiol.9, 787. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00787

49

Xu D. Nepal K. K. Chen J. Harmody D. Zhu H. McCarthy P. J. et al . (2018b). Nocardiopsistins AC: New angucyclines with anti-MRSA activity isolated from a marine sponge-derived Nocardiopsis sp. HB-J378. Synthetic Syst. Biotechnol.3, 246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2018.10.008

50

Zhou X. Fenical W. (2016). The unique chemistry and biology of the piericidins. J. antibiotics.69, 582–593. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.71

51

Zong G. Fu J. Zhang P. Zhang W. Xu Y. Cao G. et al . (2022). Use of elicitors to enhance or activate the antibiotic production in Streptomyces. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol.42, 1260–1283. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2021.1987856

Summary

Keywords

bioactivity, deep-sea, marine Actinomycetota, natural products, OSMAC

Citation

Correia S, Ribeiro I, Braga-Henriques A, Leão PN, Urbatzka R and Carvalho MF (2026) Exploring deep-sea Actinomycetota chemical diversity by using the OSMAC approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1754764. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1754764

Received

26 November 2025

Revised

02 January 2026

Accepted

16 January 2026

Published

06 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Hui Cui, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, China

Reviewed by

Tan Suet May Amelia, Chang Gung University, Taiwan

Chengqian Pan, Jiangsu University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Correia, Ribeiro, Braga-Henriques, Leão, Urbatzka and Carvalho.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofia Correia, sofia.correia@ciimar.up.pt

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.