- 1Key Laboratory of Industrial Ecology and Environmental Engineering (Ministry of Education), School of Environmental Science and Technology, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

- 2State Environmental Protection Key Laboratory of Coastal Ecosystem, National Marine Environmental Monitoring Center, Dalian, China

Introduction: Copper nanoparticles (Cu-NPs) have been increasingly released into marine environments due to their extensive applications, posing potential risks to marine organisms and human health. Although Cu-NPs of different particle sizes exhibit distinct toxicities—largely attributed to variations in specific surface area and Cu2+ dissolution rates—current physicochemical parameters still fail to fully explain these toxic effects, and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Methods: This study aimed to investigate the toxic effects and underlying molecular mechanisms of Cu-NPs of different nominal primary diameters (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm) on the marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma).

Results: LC50 point estimates suggested slightly higher toxicity for smaller Cu-NPs. Integrated miRNAomic and transcriptomic analyses revealed that Cu-NPs-10 exposure markedly activated multiple metabolic pathways, including drug metabolism–cytochrome P450, retinol metabolism, and ascorbate and aldarate metabolism. Cu-NPs-50 exposure primarily affected neurodevelopment and synaptic signaling, with predicted miRNA–mRNA associations including miR-202 with mprip-like and miR-2187 with adgrg2-like. In contrast, Cu-NPs-100 exposure activated inflammation- and barrier repair-related networks, with potential miRNA–mRNA relationships involving miR-202 with tm4sf5, miR-106a, miR-132c, miR-200b, and miR-202 with znfx1, as well as miR-2187 and miR-202 with rhbdl2.

Discussion: Collectively, the integrated miRNA–mRNA analysis suggests that smaller Cu-NPs show a correlation with more intense molecular stress responses than larger particles under seawater transformations (e.g., aggregation/dissolution), and provides insights into the key regulatory networks potentially underlying these size-associated responses.

1 Introduction

The rapid advancement of nanotechnology has greatly promoted the widespread application of metal-based nanoparticles. Among them, Cu-NPs have attracted considerable attention due to their excellent optical, thermal, and electrical properties, which make them widely used in semiconductors, electronic chips, and photocatalysis (Hossain et al., 2023). In addition, owing to their strong antimicrobial activity against various pathogenic microorganisms, Cu-NPs are increasingly applied in food packaging to inhibit spoilage microbes and extend shelf life (Rai et al., 2018). They are also employed in environmental remediation to enhance water purification and in agriculture as additives in pesticides and herbicides (Rahman et al., 2022). In the biomedical field, Cu-NPs have been utilized in chronic wound dressings (Tao et al., 2019), anti-infective coatings (Yudaev et al., 2022), and antiviral materials (Ha et al., 2022; Yimeng et al., 2022), demonstrating application potential comparable to that of silver nanoparticles (Salvo and Sandoval, 2022; Tortella et al., 2022). However, with their increasing production and utilization, Cu-NPs are inevitably released into the environment through wastewater, agricultural runoff, and industrial effluents. Bansal et al. (2012) reported that Cu-NPs could migrate within soil under field conditions, release copper ions, and significantly alter soil microbial community composition. After undergoing physical (aggregation, sedimentation), chemical (dissolution, redox), and biological (degradation, biotransformation) processes (Devasena et al., 2022), Cu-NPs ultimately enter aquatic environments, where they can be taken up by aquatic organisms and transferred through the food web to higher trophic levels, leading to ecological exposure and potential toxicological risks (Yu et al., 2022).

Previous studies have demonstrated that the toxic mechanisms of Cu-NPs in living organisms involve multiple biological processes, including cell membrane disruption, oxidative stress, DNA damage, immune activation, and apoptosis, with most toxic effects attributed to their ability to induce oxidative stress (Yu et al., 2020; Ramos-Zuniga et al., 2023; Sielska and Skuza, 2025). Zhang et al. (2018) reported that Cu-NPs induced dose-dependent developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos, causing eye hypoplasia, inhibition of intestinal formation, and differential expression of genes associated with wound healing, stimulus response, phototransduction, and metabolic processes. Li et al. (2013) found that in Escherichia coli, Cu-NPs at low to moderate concentrations simultaneously triggered oxidative stress, DNA damage, membrane injury, and protein damage, significantly inhibiting bacterial growth. The primary toxicity was attributed to the rapid release of Cu(I), which drives hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generation during oxidation. In rainbow trout, exposure experiments conducted by Al-Bairuty et al. (2013) and Khan et al. (2025) revealed that Cu-NPs markedly activated immune and inflammatory pathways, accompanied by melano-macrophage aggregation and significant upregulation of inflammatory markers such as HSP70 and IL-1β. Histopathological observations showed severe tissue damage, including lamellar fusion in gills, hepatocellular vacuolation, and necrosis.

Zebrafish and rainbow trout have played essential roles as freshwater model organisms in nanotoxicological research (Kumah et al., 2023). However, O. melastigma, a species of significant ecological and commercial importance that inhabits distinctly different environments, has been recognized as an “ideal marine model fish” owing to its small body size, easily distinguishable sex, short generation time, and high sensitivity to environmental pollutants (Dong et al., 2014). Regarding exposure characteristics, most studies on Cu-NPs have focused on dose-dependent toxic effects, while systematic investigations of particle size–dependent toxicity remain limited (Zhao et al., 2025). Particle size is a critical determinant of nanotoxicity, influencing nanoparticle stability, solubility, and interactions with biological membranes in aquatic environments (Bondarenko et al., 2013). Transcriptomic approaches have been widely used to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the toxic effects of metallic nanoparticles (Simon et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2022); however, post-transcriptional regulation—particularly miRNA-mediated regulation—also plays a crucial role. miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules of approximately 20–24 nucleotides that primarily suppress translation or promote mRNA degradation by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′UTR of target mRNAs (Bartel, 2009). Integrating mRNA and upstream miRNA expression profiles to construct directed regulatory networks can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity. Therefore, joint miRNA–mRNA analyses to elucidate how particle size modulates the accumulation, dissolution-transformation processes, and ultimate toxic effects of Cu-NPs in marine organisms hold significant scientific importance.

This study aimed to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the acute toxicity of Cu-NPs with different particle sizes (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm) in O. melastigma. Specifically, we examined how Cu-NPs of varying sizes influence gene expression and miRNA regulatory networks, and whether these molecular responses exhibit size-dependent characteristics. High-throughput RNA sequencing and miRNA sequencing were employed to jointly analyze transcriptomic and epigenetic regulatory alterations induced by Cu-NPs exposure. The study particularly focused on the effects of particle size on key biological processes, including DNA damage repair, cell cycle regulation, immune signaling, and cell death. Furthermore, by integrating shared miRNA–mRNA association analyses, key regulatory axes were identified to elucidate the ecotoxicological mechanisms of Cu-NPs and to provide a theoretical basis for developing molecular biomarkers for nanomaterial-induced toxicity in marine organisms.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Oryzias melastigma cultivation

Four-month-old O. melastigma with an average body length of 2.1 cm and an average body weight of 0.20 g were used for the experiments. Seawater was sterilized using ultraviolet (UV) irradiation prior to use. Fish were acclimated for two weeks in 50 L glass aquaria under controlled laboratory conditions. The water temperature was maintained at 27 ± 1 °C, salinity at 30‰, pH at 8.1 ± 0.1, and dissolved oxygen at 7.0 ± 0.1 mg/L, with a photoperiod of 14 h light and 10 h dark. The fish were fed freshly hatched brine shrimp (Artemia nauplii) twice daily. Water was renewed twice per week, and dead individuals were promptly removed. The cumulative mortality during acclimation did not exceed 2%.

2.2 Copper nanoparticle characterization

Cu-NPs dispersions with nominal particle sizes of 10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm (designated as Cu-NPs-10, Cu-NPs-50, and Cu-NPs-100, respectively) were purchased from Beijing Dekedaojin Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). According to the manufacturer’s certificate of analysis, the particles were supplied as powder with a stated purity of 99% and a surface modification of uncoated. Stock suspensions were prepared in artificial seawater and dispersed by bath sonication prior to dilution with artificial seawater to the desired concentrations. The morphology and primary particle size of Cu-NPs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Hitachi H-7500, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential (surface charge) of Cu-NPs in seawater were measured at 0 and 96 h using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Zetasizer Nano Series, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK).

2.3 Acute toxicity test

The acute toxicity test on O. melastigma was conducted in accordance with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals No. 203 (Fish, Acute Toxicity Test). For each particle size of Cu-NPs, six exposure concentrations were established: Cu-NPs-10 at 5, 6.6, 8.7, 11.5, 15.2, and 20 mg/L; Cu-NPs-50 at 10, 11.5, 13.2, 15.2, 17.4, and 20 mg/L; and Cu-NPs-100 at 10.3, 11.7, 13.2, 15.0, 17.0, and 19.3 mg/L. Exposure solutions were prepared by diluting stock suspensions with artificial seawater (salinity 30‰). For each concentration group, seven fish were randomly assigned, with three replicates per treatment. Experimental conditions were maintained at 27 ± 1 °C, salinity 30‰, pH 8.1 ± 0.1, dissolved oxygen 7.0 ± 0.1 mg/L, and a photoperiod of 14 h light and 10 h dark. Mortality was recorded daily, and dead individuals were promptly removed. After 96 h of exposure, the median lethal concentration (LC50) values for Cu-NPs of different particle sizes were calculated using the probit method.

2.4 mRNA and miRNA sequencing

Cu-NPs were applied at a concentration of 15 mg/L, which approximately corresponds to the LC50 values determined for three different particle sizes of Cu-NPs in O. melastigma. This concentration was used as a common nominal mass concentration to facilitate cross-size comparison for downstream mRNA and miRNA sequencing. Four exposure treatments were established: (1) control group (CK group); (2) Cu-NPs-10; (3) Cu-NPs-50; and (4) Cu-NPs-100. Each treatment included three replicates. Water quality parameters were measured and recorded once daily throughout the exposure period (Supplementary Table S1). Under the same exposure conditions as those used in the acute toxicity test, O. melastigma were exposed for 96 h. From each replicate of the four groups, one individual was randomly collected, resulting in a total of 12 samples. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until RNA extraction.

Total RNA was extracted and used for both transcriptome and miRNA sequencing. Detailed procedures for mRNA and miRNA sequencing—including RNA extraction, library construction, enrichment, purification, quantification, bridge amplification, and Illumina sequencing—are provided in the Supplementary Information. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) were identified using the R statistical package edgeR (Empirical analysis of Digital Gene Expression in R; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html/), with significance thresholds set at p < 0.05. Target genes of miRNAs were predicted using TargetFinder, and the annotation information of the target genes was matched to the corresponding miRNAs for subsequent regulatory network analysis.

2.5 Bioinformatics analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis of DEGs and target genes of DEmiRNAs was performed using Goatools (https://github.com/tanghaibao/Goatools). Four multiple-testing correction methods—Bonferroni, Holm, Sidak, and false discovery rate (FDR)—were applied to adjust p-values. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was conducted using KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/kobas3), with Benjamini–Hochberg (BH, FDR) correction for multiple testing. All p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact test. GO terms and KEGG pathways with corrected p-values (p(fdr) ≤ 0.05) were considered significantly enriched.

2.6 Data analysis

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was used to evaluate the overall differences between Cu-NPs exposure groups of different particle sizes and the CK group. The significance of group differences was assessed using the Adonis test, where a higher coefficient of determination (R²) indicates greater dissimilarity between groups. After sequencing, Venn diagram analysis was performed to compare the numbers and intersections of upregulated and downregulated DEGs and DEmiRNAs among different Cu-NPs treatments, aiding in the identification of key molecules with shared regulatory roles. Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between common miRNAs and their predicted target genes. Correlations with coefficients greater than 0.6 or less than −0.6 and p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of copper nanoparticles

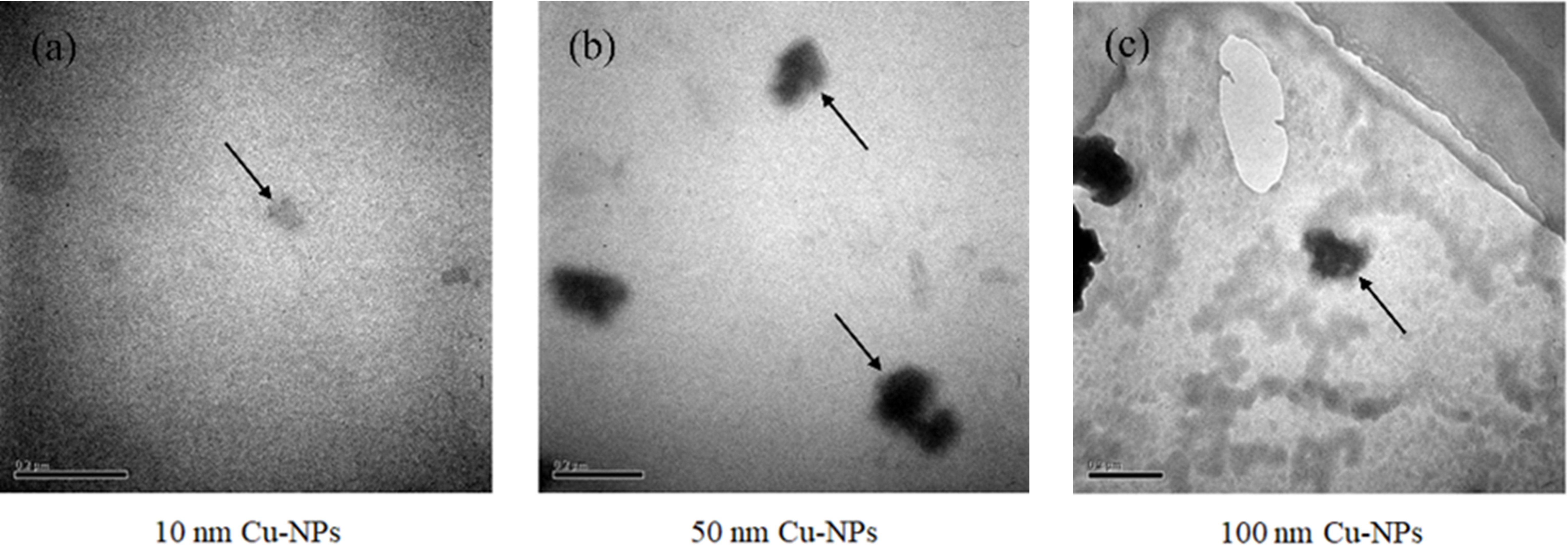

The morphology, particle size, and aggregation state of Cu-NPs were characterized using TEM. Representative TEM images of Cu-NPs with nominal sizes of 10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm are shown in Figure 1. The original Cu-NPs exhibited spherical or nearly spherical shapes with relatively uniform particle size distributions. Smaller Cu-NPs displayed better dispersibility in suspension. Specifically, Cu-NPs-10 particles were small, well-dispersed, and showed no obvious aggregation. Cu-NPs-50 particles were larger and more clearly defined, with slight aggregation observed among some particles, although individual particles remained distinguishable. In contrast, Cu-NPs-100 particles appeared larger and showed pronounced aggregation, with some particles stacking or adhering to the support film surface.

Figure 1. TEM images of Cu-NPs with three particle sizes (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm). (a) Cu-NPs-10, with arrows indicating well-dispersed individual particles; (b) Cu-NPs-50, with the upper arrow indicating dispersed particles and the lower arrow indicating aggregated particles; (c) Cu-NPs-100, with arrows indicating aggregated particle clusters.

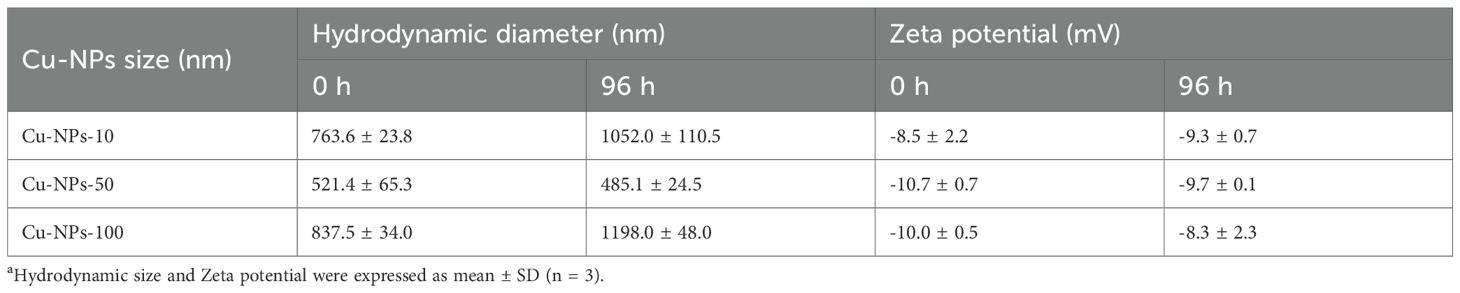

The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of Cu-NPs dispersed in seawater were measured at 0 h and 96 h using DLS (Table 1). All three particle sizes of Cu-NPs exhibited noticeable aggregation over time, particularly Cu-NPs-10 and Cu-NPs-100. The absolute values of zeta potential for all samples were below 10 mV, indicating low colloidal stability and a high tendency for aggregation in seawater. At 0 h, the hydrodynamic diameters of Cu-NPs-10, Cu-NPs-50, and Cu-NPs-100 were 763.6 ± 23.8 nm, 521.4 ± 65.3 nm, and 837.5 ± 34.0 nm, respectively. After 96 h of exposure, these values increased to 1052.0 ± 110.5 nm, 485.1 ± 24.5 nm, and 1198.0 ± 48.0 nm, respectively. The initial zeta potentials of Cu-NPs-10, Cu-NPs-50, and Cu-NPs-100 were −8.5 ± 2.2 mV, −10.7 ± 0.7 mV, and −10.0 ± 0.5 mV, respectively, which slightly changed to −9.3 ± 0.7 mV, −9.7 ± 0.1 mV, and −8.3 ± 2.3 mV after 96 h.

Table 1. Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of Cu-NPs at 0 h and 96 h determined by dynamic light scatteringa.

3.2 Acute toxicity

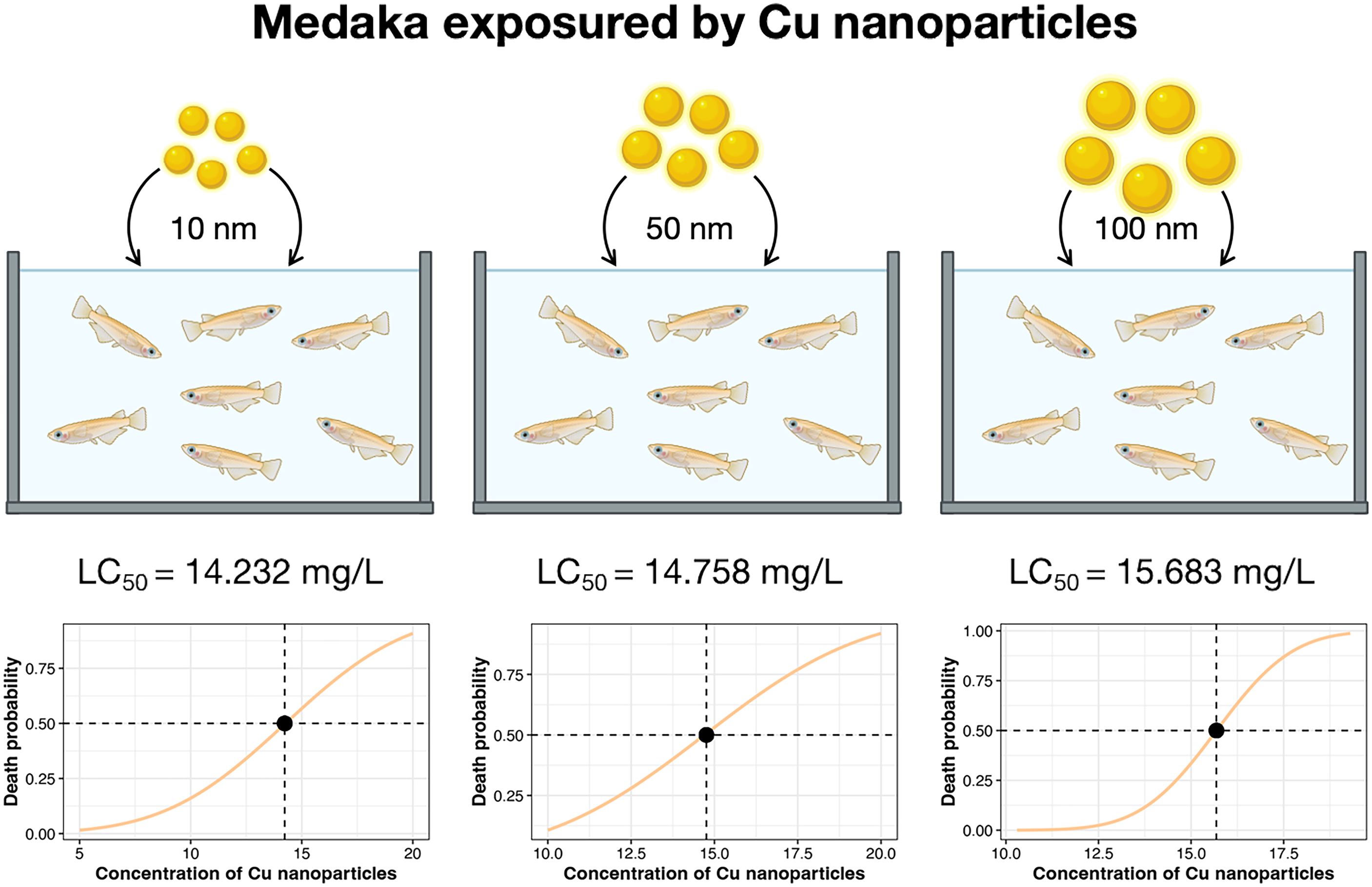

The 96 h LC50 values of Cu-NPs-10, Cu-NPs-50, and Cu-NPs-100 for O. melastigma were 14.232 mg/L, 14.758 mg/L, and 15.683 mg/L, respectively (Figure 2). The LC50 point estimates suggested a modest size-related trend in acute toxicity. Given the similar LC50 estimates across particle sizes, 15 mg/L was selected as a common nominal mass concentration for subsequent exposure and sampling.

Figure 2. Acute toxicity of Cu-NPs with three particle sizes (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm) to O. melastigma.

3.3 Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

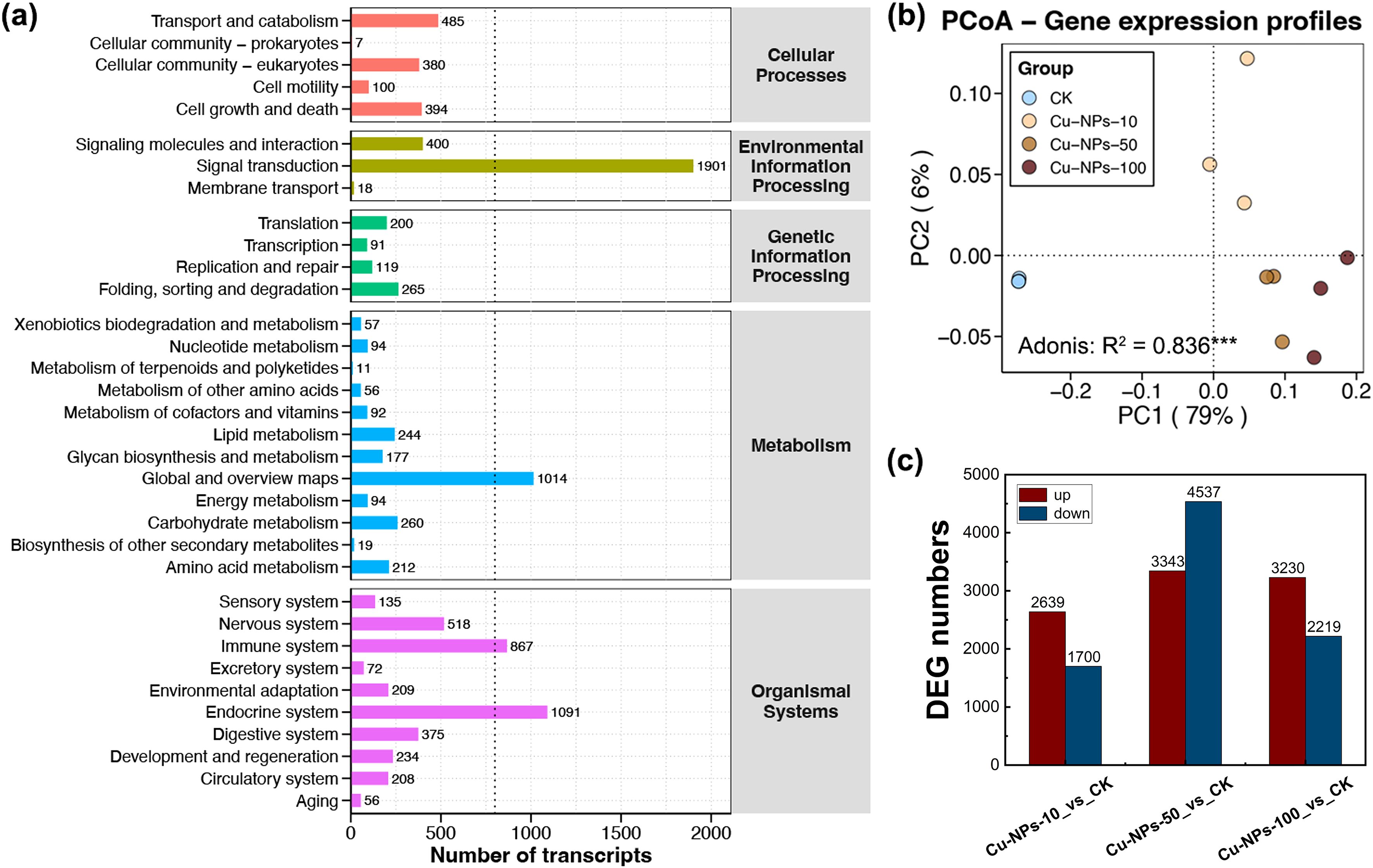

To investigate the effects of different particle sizes of Cu-NPs on mRNA expression, transcriptome sequencing and differential expression analysis were performed on O. melastigma samples. The basic statistical information of the transcriptome sequencing data is provided in Supplementary Table S2. Among all annotated pathways, those related to signal transduction contained the highest number of transcripts (1901), followed by the endocrine system (1091), general and overview metabolism pathways (1014), and the immune system (867) (Figure 3a). PCoA revealed a clear separation between the CK and Cu-NPs exposure groups along the PC1 axis (R² = 0.836, p < 0.001), which accounted for 79% of the total expression variance (Figure 3b). Differences among Cu-NPs treatments of varying particle sizes were also evident along the PC2 axis, explaining 6% of the variance. The Adonis test further confirmed that the treatment factor accounted for 83.6% of the total variation, indicating a strong impact of Cu-NPs exposure on global gene expression profiles. Exposure to Cu-NPs induced substantial transcriptional alterations in marine medaka, with the Cu-NPs-50 group exhibiting the largest number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Specifically, 2639 genes were upregulated and 1700 genes were downregulated in the Cu-NPs-10 group; 3343 genes were upregulated and 4537 downregulated in the Cu-NPs-50 group; and 3230 genes were upregulated and 2219 downregulated in the Cu-NPs-100 group (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Functional annotation and differential gene expression analysis of Cu-NPs exposure groups. (a) Distribution of transcript numbers across pathways in KEGG functional classifications. (b) PCoA based on gene expression profiles showing separation between the CK and Cu-NPs exposure groups (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm). Percentages in parentheses indicate variance explained by each axis (PC1 = 79%, PC2 = 6%); Adonis test, R² = 0.836*** (***p < 0.001). (c) Numbers of DEGs compared with the CK group, with red bars indicating upregulated genes and blue bars indicating downregulated genes.

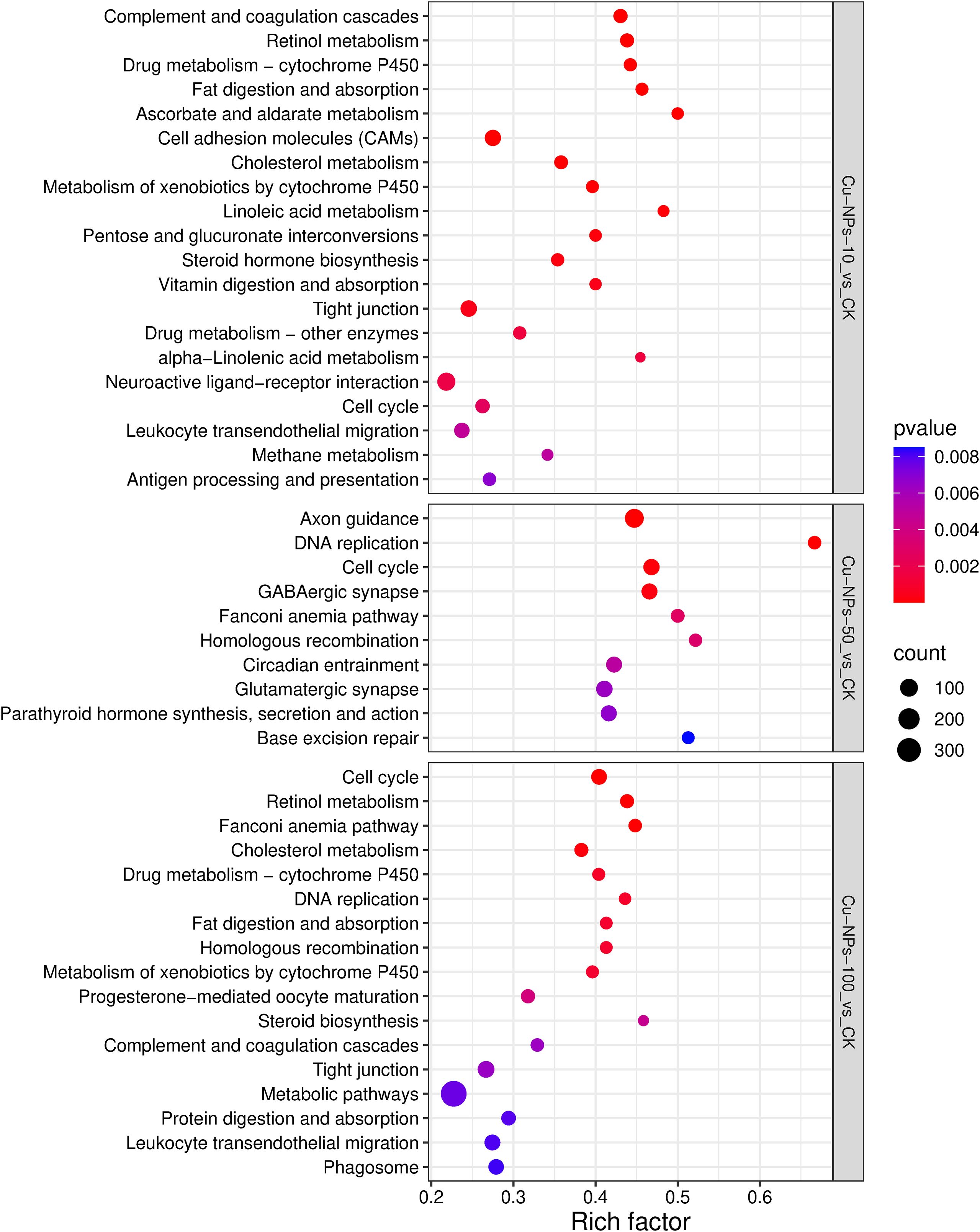

The DEGs identified in marine medaka were primarily associated with genetic information processing, signal transduction, metabolism, and immune system functions, and the affected biological systems varied markedly with Cu-NPs particle size (Figure 4). In the Cu-NPs-10 exposure group, DEGs were significantly enriched in metabolic pathways such as Retinol metabolism, Drug metabolism – cytochrome P450, Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, and Cholesterol metabolism. In contrast, DEGs in the Cu-NPs-50 group were predominantly enriched in neural development and signaling-related pathways, including Axon guidance, GABAergic synapse, Glutamatergic synapse, and Gap junction. Meanwhile, DEGs in the Cu-NPs-100 group were mainly enriched in immune and barrier damage–related pathways, such as Complement and coagulation cascades, Tight junction, and Leukocyte transendothelial migration.

Figure 4. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. The rich factor (x-axis) is the ratio of the number of differentially expressed genes to the total number of genes in a pathway. The size of the bubble represents the number of genes, and the color intensity indicates the statistical significance (pvalue) of the enrichment.

3.4 miRNA sequencing and analysis

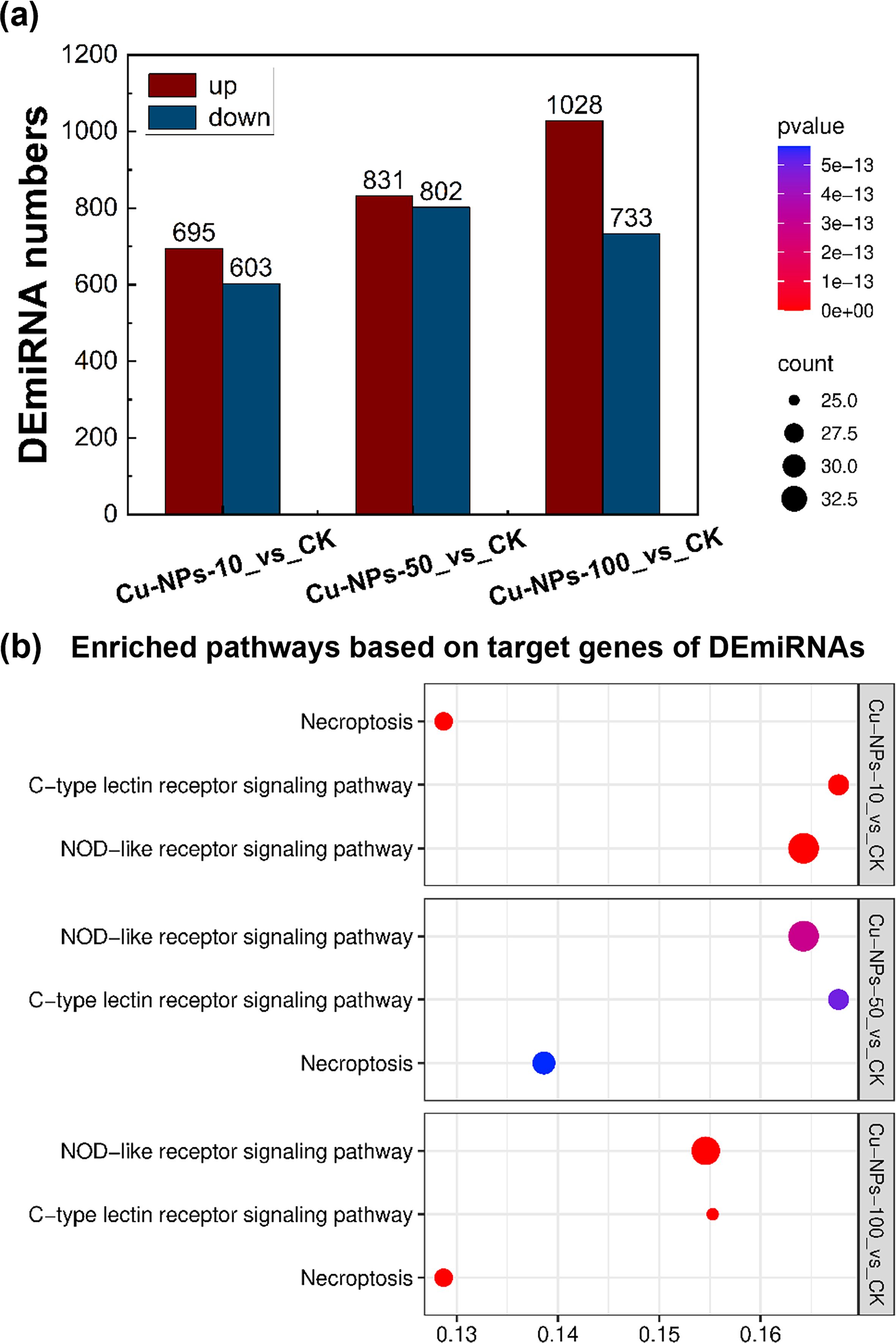

To investigate the effects of different Cu-NPs particle sizes on miRNA expression, miRNA sequencing and differential expression analyses were conducted on O. melastigma samples. The statistical information of the miRNA sequencing data is presented in Supplementary Table S3. The results showed that the number of upregulated DEmiRNAs exceeded that of downregulated ones, and that larger Cu-NPs induced more DEmiRNAs than smaller ones (Figure 5a). Specifically, 695 upregulated and 603 downregulated miRNAs were identified in the Cu-NPs-10 group, 831 upregulated and 802 downregulated miRNAs in the Cu-NPs-50 group, and 1028 upregulated and 733 downregulated miRNAs in the Cu-NPs-100 group. KEGG enrichment analysis of the target genes of DEmiRNAs (Figure 5b) revealed that these genes were mainly enriched in the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, Necroptosis, and C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway, all of which play critical roles in the regulation of immune responses, inflammation, and cell death. The enrichment factors of the Cu-NPs-100 group were lower than those observed in the Cu-NPs-10 and Cu-NPs-50 groups, suggesting relatively weaker activation of these pathways in response to larger particle sizes.

Figure 5. Effects of Cu-NPs exposure on DEmiRNAs and KEGG pathway enrichment of their target genes. (a) Numbers of DEmiRNAs in O. melastigma exposed to Cu-NPs of different particle sizes (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm) compared with the CK group. Red bars indicate upregulated miRNAs, and blue bars indicate downregulated miRNAs. (b) KEGG pathway enrichment of target genes of DEmiRNAs, showing the top three significantly enriched pathways for each treatment group.

3.5 Identification of key genes and miRNAs

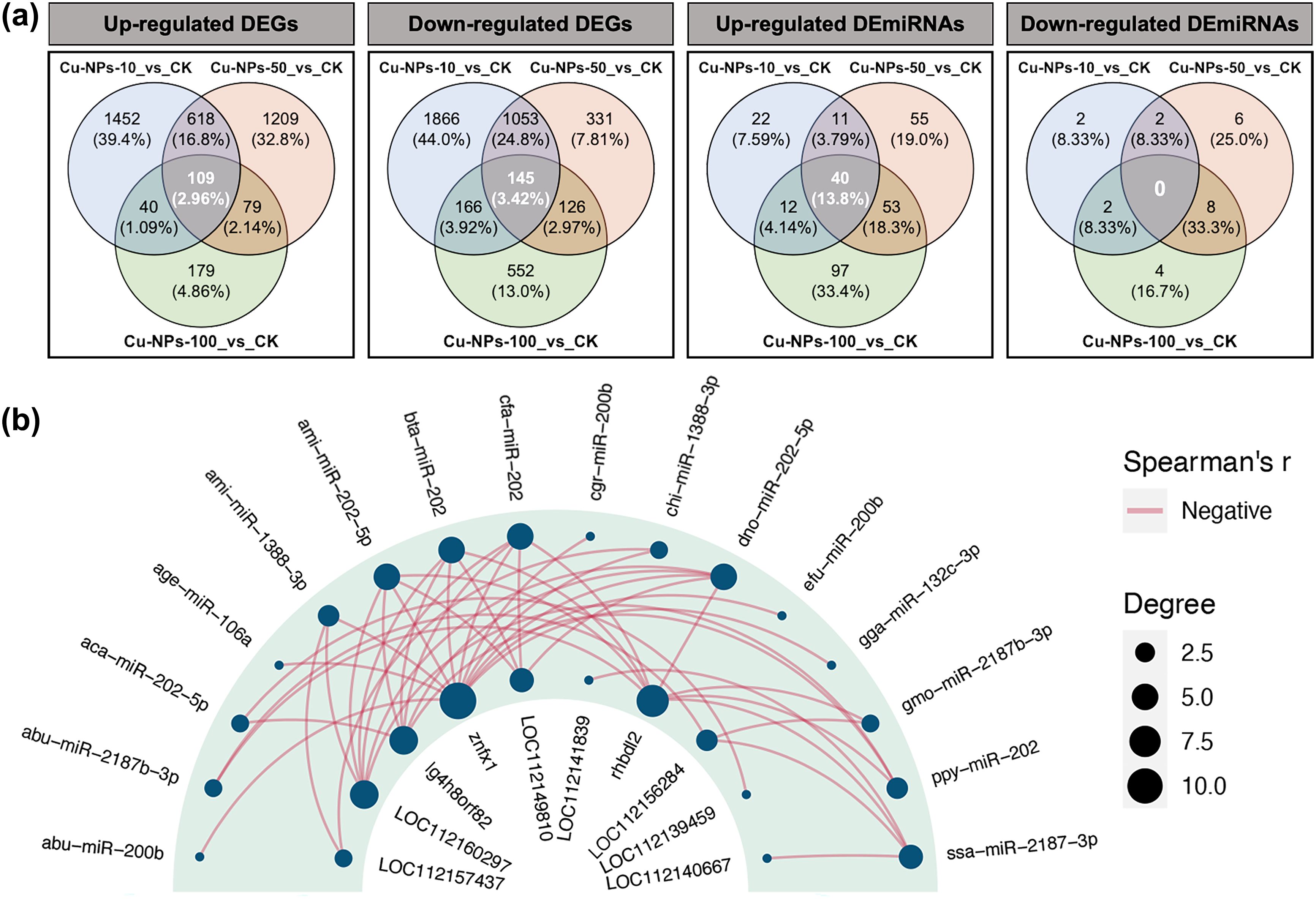

To identify key miRNAs and genes that consistently responded to Cu-NPs exposure across different particle sizes, Venn diagram analysis was performed on the three sets of differential expression results (Figure 6a). A total of 109 commonly upregulated genes, 145 commonly downregulated genes, and 40 commonly upregulated miRNAs were identified, all of which exhibited significant differential expression under exposure to Cu-NPs of varying particle sizes.

Figure 6. Correlation analysis between DEGs and DEmiRNAs under Cu-NPs exposure. (a) Venn diagrams showing the overlap and specificity of upregulated DEGs, downregulated DEGs, upregulated DEmiRNAs, and downregulated DEmiRNAs in O. melastigma exposed to Cu-NPs of different particle sizes (10 nm, 50 nm, and 100 nm) compared with the CK group. Values in parentheses indicate the percentage of each subset relative to the total number of differentially expressed molecules in the corresponding group. (b) Negative correlation (Spearman’s r < 0) miRNA–mRNA regulatory network. The outer ring represents miRNAs, the inner ring represents their target genes, and the connecting lines indicate negatively correlated regulatory relationships. Bubble size corresponds to the node degree.

Subsequent integration of these shared DEGs and DEmiRNAs using Spearman’s correlation analysis (Figure 6b) revealed significant negative correlations between 16 DEmiRNAs and 10 DEGs. Several DEGs were annotated as LOC112160297, LOC112149810, LOC112156284, and LOC112139459. Homology-based annotation identified their putative gene names, including adgrg2-like, tm4sf5, isp2, and mprip-like (the complete gene names can be found in Supplementary Table S4). These 16 miRNAs were grouped into six categories: miR-106a, miR-1388, miR-132c, miR-200b, miR-2187, and miR-202. Among them, miR-106a, miR-132c, miR-200b, and miR-202 showed inverse expression correlations with znfx1; miR-2187 and miR-202 with rhbdl2; miR-1388 with adgrg2-like; miR-2187 with type-2 ISP; and miR-202 additionally with lg4h8orf82, mprip-like, and tm4sf5. These inverse correlations indicate potential miRNA–mRNA regulatory relationships and were used to nominate putative miRNA–mRNA pairs, which require experimental validation.

4 Discussion

In this study, acute toxicity tests suggested a size-related trend of Cu-NPs in O. melastigma. The 96 h LC50 estimates were within a relatively narrow range, with Cu-NPs-10 showing the lowest LC50 value, followed by Cu-NPs-50, whereas Cu-NPs-100 exhibited the highest LC50 value. Moreover, because omics sampling was conducted at a near-LC50 concentration, the observed molecular responses may reflect severe-stress or lethality-associated signatures; and sublethal LCx-based designs would be preferable for resolving early adaptive pathways. Particle size is recognized as a critical determinant of nanoparticle toxicity (Saquib et al., 2012). Our LC50 pattern is consistent with a general trend reported in the literature that smaller Cu-NPs often induce stronger toxic responses, although the magnitude of size effects varies substantially across species, endpoints, and exposure media. For example, Jing. et al. (2014) observed in zebrafish embryos that 25 nm Cu-NPs had an LC50 of 0.58 mg/L, which was significantly lower than that of 50 nm (1.65 mg/L) and 100 nm (1.90 mg/L) Cu-NPs. Likewise, Song et al. (2013) demonstrated that Cu-NPs suspensions with nominal diameters of 25, 50, and 78 nm exhibited increased cytotoxicity with decreasing particle size in mammalian (H4IIE, HepG2) and fish (PLHC-1, RTH-149) hepatocyte lines. Our results are also consistent with findings in rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Prabhu et al., 2009), where 40 and 60 nm Cu-NPs induced significantly greater lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release compared to 80 nm particles, leading to pronounced cell morphological disruption, impaired neurite network formation, and reduced mitochondrial metabolic activity.

In addition, the toxicity of Cu-NPs in seawater is closely associated with their aggregation state and ion release rate (Behzadi et al., 2017). Generally, when nanoparticles aggregate into larger clusters, their cellular uptake efficiency decreases (Chan, 2011), resulting in reduced toxicity (Rotini et al., 2017; Thiagarajan et al., 2019). In the present study, all three Cu-NPs particle sizes exhibited varying degrees of aggregation; however, Cu-NPs-10 showed slightly higher apparent toxicity despite stronger aggregation. This pattern may indicate that the primary particle size remained influential under seawater conditions. A plausible explanation is that the smaller primary size provides a larger specific surface area (Karlsson et al., 2013), which could enhance surface reactivity, accelerate dissolution, and promote the release of Cu2+ ions (Leitner et al., 2019). The release of copper ions can acidify the surrounding medium and increase their bioavailability (Malhotra et al., 2020), thereby intensifying toxic effects. Notably, in the present study, dissolved Cu2+ in the exposure media and internal Cu accumulation in O. melastigma were not quantified; therefore, we cannot determine whether the observed toxicity was driven primarily by particle-specific effects, dissolved ions, or their interaction. Accordingly, our interpretation is most consistent with prior evidence indicating that primary particle size can be a key determinant of metal-ion release and downstream toxicity outcomes (Gliga et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2023).

In the genome of O. melastigma, pathways related to signal transduction, endocrine regulation, immune modulation, and overall metabolic processes contained the highest numbers of transcripts, reflecting their central roles in maintaining organismal homeostasis. Among these, signal transduction pathways were the most abundantly expressed (1901 transcripts) and serve as critical hubs for cellular perception, transmission, and response to external stimuli. These pathways play a pivotal role in sustaining fundamental biological functions (Su et al., 2024). The observed perturbations in these core molecular modules suggest that Cu-NPs exposure can induce systemic disruptions of physiological homeostasis.

Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and miRNA sequencing data identified putative miRNA–mRNA regulatory relationships induced by Cu-NPs exposure of different particle sizes. Notably, the expression trends of several mRNAs (tm4sf5, mprip-like, znfx1 and rhbdl2) were not strictly inversely correlated with those of their upstream miRNAs, suggesting the presence of multilayered regulatory mechanisms under different exposure conditions, such as indirect interactions, transcriptional activation, or feedback compensation (Hill et al., 2014). The target genes of DEmiRNAs across all particle-size groups were significantly enriched in the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (Mahla, 2013), necroptosis (Pasparakis and Vandenabeele, 2015), and C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway (Bermejo-Jambrina et al., 2018; He et al., 2024), indicating that these pathways constitute a common regulatory network underlying Cu-NPs–induced immune and inflammatory responses. Building upon this shared foundation, each particle size exhibited distinct dominant molecular responses. Cu-NPs-10 primarily activated metabolic pathways, characterized by enhanced detoxification- and antioxidant-related processes. Cu-NPs-50 mainly affected neural development and synaptic signaling, implying structural and functional impairments in neuronal systems. Cu-NPs-100, on the other hand, activated pathways related to inflammation and epithelial barrier repair, suggesting its involvement in tissue defense and regeneration processes. Taken together, these findings suggest that miRNA–mRNA regulatory networks may contribute to biological responses to Cu-NPs across particle sizes, with regulatory patterns differing among size classes.

Exposure to Cu-NPs-10 markedly upregulated metabolic pathways such as Retinol metabolism, Drug metabolism–cytochrome P450, and Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, indicating a pronounced state of chemical stress and metabolic adaptation in marine medaka. Retinoic acid (RA) is a key metabolic signaling molecule involved in immune and inflammatory regulation. It is primarily produced by intestinal dendritic cells and maintains mucosal immune tolerance and epithelial barrier homeostasis by enhancing Treg differentiation, suppressing Th1/Th17 responses, and downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Wu et al., 2024). Therefore, the upregulation of Retinol metabolism observed in this study may reflect activation of RA-mediated immune modulation and anti-inflammatory mechanisms aimed at mitigating tissue injury caused by Cu-NPs exposure. Ascorbate (vitamin C) is a major reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger that is preferentially consumed to block lipid peroxidation chain reactions and maintain cellular redox balance (Frei et al., 1989). The observed upregulation of the Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism pathway suggests an enhanced antioxidant response to excessive ROS generation, enabling increased ascorbate utilization and regeneration to neutralize ROS and their reactive by-products. Furthermore, enrichment of the Drug metabolism–cytochrome P450 pathway indicates an elevated detoxification burden (Zanger and Schwab, 2013), likely associated with the clearance of copper ions released from nanoparticles and their reactive intermediates. Collectively, Cu-NPs-10 exposure primarily induced robust activation of metabolic pathways involved in detoxification, antioxidation, and immune-related metabolism. These changes are consistent with a whole-body metabolic adjustment to increased chemical load and oxidative stress during nanoscale copper exposure, although causality cannot be inferred from the 0–96 h dataset alone.

Exposure to Cu-NPs-50 was associated with transcriptional changes indicative of altered neurodevelopment and synaptic signaling in O. melastigma. Based on inverse miRNA–mRNA expression patterns, we identified putative miRNA–mRNA pairs, including miR-202 with mprip-like and miR-2187 with adgrg2-like. MPRIP has been reported to modulate RhoA/ROCK signaling–dependent myosin light chain dephosphorylation, thereby influencing cytoskeletal contraction and neurite outgrowth. Loss or inhibition of MPRIP disrupts cell spreading and impairs neurite extension (Mulder et al., 2004). In the present study, mprip-like was upregulated under Cu-NPs-50 exposure, which may reflect engagement of cytoskeleton- and neurite-related programs. ADGRG2, a member of the G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) family, is broadly involved in neurotransmitter regulation, neuronal excitability, neurite elongation, and axon guidance (Betke et al., 2012). Balenga et al. (2017) demonstrated in studies of the parathyroid system that overexpression of ADGRG2 attenuated CaSR (calcium-sensing receptor)–mediated intracellular Ca2+ signaling and cAMP suppression, leading to aberrant calcium sensing in parathyroid adenoma cells. In our study, the upregulation of miR-2187 may suppress adgrg2-like expression, potentially leading to reduced intracellular cAMP levels. This change could subsequently affect the synthesis of neurotrophic factors and might be indirectly involved in pathways associated with synaptic plasticity and learning and memory—such as the MAPK and Ras signaling cascades (Morozov et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2017). Notably, several pathways related to Axon guidance, GABAergic synapse, and Gap junction were significantly downregulated, supporting the interpretation that Cu-NPs-50 exposure is linked to disrupted neuronal connectivity and excitation–inhibition coordination during development (Ramamoorthi and Lin, 2011; Pernelle et al., 2018; Kim and Kim, 2020). Collectively, these findings suggest that Cu-NPs-50 exposure is associated with altered neurodevelopment- and synaptic signaling in O. melastigma. Although mprip-like upregulation may indicate engagement of cytoskeleton- and neurite-related programs under Cu-NPs-50 exposure, this change appears insufficient to fully restore normal neurite architecture. In addition, whole-fish RNA under severe toxicity may reflect generalized suppression rather than nervous-system–specific effects.

Cu-NPs-100 exposure was associated with transcriptomic signatures related to cellular barrier disruption and defensive response activation, with predicted miRNA–mRNA associations involving miR-202 with tm4sf5, miR-106a, miR-132c, miR-200b, and miR-202 with znfx1, as well as miR-2187 and miR-202 with rhbdl2. ZNFX1 is a mitochondria-localized double-stranded RNA sensor that activates type I interferon (IFN-I) responses through the MAVS pathway (Wang et al., 2019). Subsequently, activation of IFN-I receptors induces the expression of complement components such as complement factor B and C3 (Afzali et al., 2022). In this study, znfx1 was significantly upregulated, which may have contributed to activation of the IFN-I pathway and the upregulation of complement-associated genes, leading to enrichment of the Complement and coagulation cascades pathway. This activation may amplify inflammatory and coagulative responses, thereby increasing the risk of tissue injury (Oikonomopoulou et al., 2011). On the other hand, Choi et al. (2014) reported that tm4sf5 knockdown in zebrafish disrupted muscle fiber alignment and cell–matrix adhesion, impairing trunk development. Johnson et al. (2017) used quantitative proteomics to identify substrate profiles of the rhomboid protease RHBDL2 in human cells, revealing several targets involved in epithelial homeostasis. These findings suggest that RHBDL2 plays an important role in maintaining epithelial integrity. In the present study, the upregulation of miR-202, miR-106a, miR-132c, miR-200b, and miR-2187 was accompanied by significant increases in tm4sf5, rhbdl2 expression and enrichment of the Tight junction pathway. This pattern is consistent with barrier-associated remodeling (e.g., tight junction signaling), although tissue specificity cannot be resolved from whole-body RNA. Taken together, we propose that Cu-NPs-100 exposure may involve a dynamic balance between inflammatory/coagulative activation that could compromise junctional integrity and concurrent barrier remodeling characterized by reinforcement of cell adhesion, cytoskeletal reorganization, and tight junction signaling.

These findings suggest that Cu-NPs of different nominal sizes elicit distinct whole-body transcriptomic signatures in O. melastigma, with enriched pathways that are often associated with specific organ functions. Cu-NPs-10 exposure was characterized by detoxification activation, oxidative stress, and chemical adaptation, which are commonly associated with metabolically active organs such as the liver and intestine. Cu-NPs-50 exposure showed prominent changes in neurodevelopment- and synaptic signaling–related pathways, consistent with a nervous-system–associated response signature. In contrast, Cu-NPs-100 exposure preferentially enriched inflammatory signaling, complement pathways, and tight junction remodeling, which are frequently implicated in barrier and mucosal tissues. Collectively, these pathway patterns raise the possibility that different-sized Cu-NPs may engage different physiological systems to varying extents under seawater transformations, as suggested in prior studies on nanoparticle toxicity and distribution (Win-Shwe and Fujimaki, 2011; Augustine et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2023). However, key DEGs and DEmiRNAs were not independently validated by qRT–PCR in this study. Future work should validate these pathway-level inferences using tissue-resolved qPCR (e.g., brain for neurodevelopmental markers; gill/intestine for tight junction and innate immune markers) or tissue transcriptomics, to both determine whether size-dependent toxicity is linked to differential in vivo distribution and retention and clarify whether the observed signatures reflect organ-enriched responses versus whole-body morbidity effects.

Based on integrated transcriptomic and miRNA sequencing analyses, this study systematically identified a series of key genes and miRNAs that exhibited significant responses to Cu-NPs exposure. These molecules show strong potential as molecular biomarkers for nanomaterial-induced toxicity and may serve as novel indicators for ecological risk assessment (Hou et al., 2011). Biomarkers play a crucial role in environmental monitoring by reflecting organismal responses to pollutants at the molecular level, thus enabling early detection and rapid warning of potential ecological risks (van der Oost et al., 2002). Compared with traditional physicochemical detection methods, biomarker-based monitoring strategies that utilize gene and miRNA expression can reveal the biological effects of environmental contaminants at much earlier stages, providing more sensitive and dynamic tools for ecosystem health evaluation and environmental protection (Vrijens et al., 2015; Ou et al., 2021; Letelier et al., 2023; Moqri et al., 2024). Furthermore, the miRNA–mRNA regulatory network established in this study offers a new epigenetic perspective for nanotoxicology research, uncovering multilayered molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying organismal responses to Cu-NPs exposure. This integrated network framework not only enriches the diversity of available biomarkers but also lays an important foundation for developing a comprehensive, multidimensional toxicity assessment system for nanomaterials.

5 Conclusion

This study evaluated the molecular toxic effects of Cu-NPs with different nominal primary sizes on O. melastigma and revealed size-associated differences in molecular responses. By integrating transcriptomic and miRNAomic data, we characterized the multidimensional biological responses induced by Cu-NPs exposure at the molecular regulatory level. The results demonstrated that smaller particles tended to elicit broader molecular perturbations across multiple metabolic and signaling pathways. These findings highlight the importance of primary particle size in shaping biological responses to Cu-NPs in seawater and nominate putative miRNA–mRNA networks that may contribute to these responses, warranting future experimental validation.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository, accession number PRJNA1374463.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Biomedical & Medical Ethics Committee of Dalian University of Technology. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PR: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. PZ: Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Supervision, Software, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. HbL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. HjL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF0506903).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2026.1758043/full#supplementary-material

References

Afzali B., Noris M., Lambrecht B. N., and Kemper C. (2022). The state of complement in covid-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 77–84. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00665-1

Al-Bairuty G. A., Shaw B. J., Handy R. D., and Henry T. B. (2013). Histopathological effects of waterborne copper nanoparticles and copper sulphate on the organs of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquat. Toxicol. 126, 104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.10.005

Augustine R., Hasan A., Primavera R., Wilson R. J., Thakor A. S., and Kevadiya B. D. (2020). Cellular uptake and retention of nanoparticles: Insights on particle properties and interaction with cellular components. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101692. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101692

Balenga N., Azimzadeh P., Hogue J. A., Staats P. N., Shi Y., Koh J., et al. (2017). Orphan adhesion gpcr gpr64/adgrg2 is overexpressed in parathyroid tumors and attenuates calcium-sensing receptor-mediated signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 32, 654–666. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3023

Bansal V., Collins D., Luxton T., Kumar N., Shah S., Walker V. K., et al. (2012). Assessing the impact of copper and zinc oxide nanoparticles on soil: A field study. PLoS One 7, e42663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042663

Bartel D. P. (2009). Micrornas: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002

Behzadi S., Serpooshan V., Tao W., Hamaly M. A., Alkawareek M. Y., Dreaden E. C., et al. (2017). Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: Journey inside the cell. Chem. Soc Rev. 46, 4218–4244. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00636a

Bermejo-Jambrina M., Eder J., Helgers L. C., Hertoghs N., Nijmeijer B. M., Stunnenberg M., et al. (2018). C-type lectin receptors in antiviral immunity and viral escape. Front. Immunol. 9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00590

Betke K. M., Wells C. A., and Hamm H. E. (2012). Gpcr mediated regulation of synaptic transmission. Prog. Neurobiol. 96, 304–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.009

Bondarenko O., Juganson K., Ivask A., Kasemets K., Mortimer M., and Kahru A. (2013). Toxicity of ag, cuo and zno nanoparticles to selected environmentally relevant test organisms and mammalian cells in vitro: A critical review. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 1181–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1079-4

Cao Y., Tian S., Geng Y., Zhang L., Zhao Q., Chen J., et al. (2023). Interactions between cuo nps and ps: The release of copper ions and oxidative damage. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 166285. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166285

Chan A.A.A.W.C. (2011). Effect of gold nanoparticle aggregation on cell uptake and toxicity. ACS Nano. 5, 5478–5489. doi: 10.1021/nn2007496

Choi Y. J., Kim H. H., Kim J. G., Kim H. J., Kang M., Lee M. S., et al. (2014). Tm4sf5 suppression disturbs integrin alpha5-related signalling and muscle development in zebrafish. Biochem. J. 462, 89–101. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140177

Devasena T., Iffath B., Renjith Kumar R., Muninathan N., Baskaran K., Srinivasan T., et al. (2022). Insights on the dynamics and toxicity of nanoparticles in environmental matrices. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 4348149. doi: 10.1155/2022/4348149

Dong S. J., Kang M., Wu X. L., and Ye T. (2014). Development of a promising fish model (oryzias melastigma) for assessing multiple responses to stresses in the marine environment. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 563131. doi: 10.1155/2014/563131

Frei B., England L., and Ames B. N. (1989). Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6377

Gliga A. R., Skoglund S., Wallinder I. O., Fadeel B., and Karlsson H. L. (2014). Size-dependent cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human lung cells the role of cellular uptake, agglomeration and Ag release. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 11, 11. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-11-11

Ha T., Pham T. T. M., Kim M., Kim Y. H., Park J. H., Seo J. H., et al. (2022). Antiviral activities of high energy e-beam induced copper nanoparticles against h1n1 influenza virus. Nanomaterials (Basel). 12, 268. doi: 10.3390/nano12020268

He H., Wang J., Ma L., Li S., Wang J., and Geng F. (2024). Applied research note: Proteomic analysis reveals potential immunomodulatory effects of egg white glycopeptides on macrophages. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 33, 100437. doi: 10.1016/j.japr.2024.100437

Hill C. G., Matyunina L. V., Walker D., Benigno B. B., and McDonald J. F. (2014). Transcriptional override: A regulatory network model of indirect responses to modulations in microrna expression. BMC Syst. Biol. 8, 36. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-36

Hossain N., Mobarak M. H., Mimona M. A., Islam M. A., Hossain A., Zohura F. T., et al. (2023). Advances and significances of nanoparticles in semiconductor applications – a review. Results Eng. 19, 101347. doi: 10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101347

Hou L., Wang D., and Baccarelli A. (2011). Environmental chemicals and micrornas. Mutat. Res. 714, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.05.004

Jing. H., G. V. M., Farooq. A., K. R. M., and M. P. W. J. G. (2014). Toxicity of different-sized copper nano- and submicron particles and their shed copper ions to zebrafish embryos. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 33, 1174–1182. doi: 10.1002/etc.2615

Johnson N., Brezinova J., Stephens E., Burbridge E., Freeman M., Adrain C., et al. (2017). Quantitative proteomics screen identifies a substrate repertoire of rhomboid protease rhbdl2 in human cells and implicates it in epithelial homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 7, 7283. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07556-3

Karlsson H. L., Cronholm P., Hedberg Y., Tornberg M., De Battice L., Svedhem S., et al. (2013). Cell membrane damage and protein interaction induced by copper containing nanoparticles—importance of the metal release process. Toxicology 313, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.07.012

Khan S. K., Dutta J., Rather M. A., Ahmad I., Nazir J., Shah S., et al. (2025). Assessing the combined toxicity of silver and copper nanoparticles in rainbow trout (oncorhynchus mykiss) fingerlings. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 203, 5838–5856. doi: 10.1007/s12011-025-04607-z

Kim S. W. and Kim K. T. (2020). Expression of genes involved in axon guidance: How much have we learned? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3566. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103566

Kumah E. A., Fopa R. D., Harati S., Boadu P., Zohoori F. V., and Pak T. (2023). Human and environmental impacts of nanoparticles: A scoping review of the current literature. BMC Public Health 23, 1059. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15958-4

Kumar M., Kulkarni P., Liu S., Chemuturi N., and Shah D. K. (2023). Nanoparticle biodistribution coefficients: A quantitative approach for understanding the tissue distribution of nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 194, 114708. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2023.114708

Leitner J., Sedmidubsky D., and Jankovsky O. (2019). Size and shape-dependent solubility of cuo nanostructures. Materials (Basel). 12, 3355. doi: 10.3390/ma12203355

Letelier P., Saldias R., Loren P., Riquelme I., and Guzman N. (2023). Micrornas as potential biomarkers of environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their link with inflammation and lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 16984. doi: 10.3390/ijms242316984

Li F., Lei C., Shen Q., Li L., Wang M., Guo M., et al. (2013). Analysis of copper nanoparticles toxicity based on a stress-responsive bacterial biosensor array. Nanoscale 5, 653–662. doi: 10.1039/c2nr32156d

Luo Y., Kuang S., Li H., Ran D., and Yang J. (2017). Cam/ppka-creb-bdnf signaling pathway in hippocampus mediates cyclooxygenase 2-induced learningmemory deficits of rats subjected to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Oncotarget 8, 35558–35572. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16009

Mahla R. S. (2013). Sweeten pamps: Role of sugar complexed pamps in innate immunity and vaccine biology. Front. Immunol. 4. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00248

Malhotra N., Ger T. R., Uapipatanakul B., Huang J. C., Chen K. H., and Hsiao C. D. (2020). Review of copper and copper nanoparticle toxicity in fish. Nanomaterials (Basel). 10, 1126. doi: 10.3390/nano10061126

Moqri M., Herzog C., Poganik J. R., Ying K., Justice J. N., Belsky D. W., et al. (2024). Validation of biomarkers of aging. Nat. Med. 30, 360–372. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02784-9

Morozov A., Muzzio I. A., Bourtchouladze R., Van-Strien N., Lapidus K., Yin D., et al. (2003). Rap1 couples camp signaling to a distinct pool of p42/44mapk regulating excitability, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Neuron 39, 309–325. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00404-5

Mulder J., Ariaens A., van den Boomen D., and Moolenaar W. H. (2004). P116rip targets myosin phosphatase to the actin cytoskeleton and is essential for rhoa/rock-regulated neuritogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15, 5516–5527. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-04-0275

Oikonomopoulou K., Ricklin D., Ward P. A., and Lambris J. D. (2011). Interactions between coagulation and complement—their role in inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 151–165. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0280-x

Ou F. S., Michiels S., Shyr Y., Adjei A. A., and Oberg A. L. (2021). Biomarker discovery and validation: Statistical considerations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.1616

Pasparakis M. and Vandenabeele P. (2015). Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature 517, 311–320. doi: 10.1038/nature14191

Pernelle G., Nicola W., and Clopath C. (2018). Gap junction plasticity as a mechanism to regulate network-wide oscillations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006025

Prabhu B. M., Ali S. F., Murdock R. C., Hussain S. M., and Srivatsan M. (2009). Copper nanoparticles exert size and concentration dependent toxicity on somatosensory neurons of rat. Nanotoxicology 4, 150–160. doi: 10.3109/17435390903337693

Rahman A., Pittarate S., Perumal V., Rajula J., Thungrabeab M., Mekchay S., et al. (2022). Larvicidal and antifeedant effects of copper nano-pesticides against spodoptera frugiperda (j.E. Smith) and its immunological response. . Insects 13, 1030. doi: 10.3390/insects13111030

Rai M., Ingle A. P., Pandit R., Paralikar P., Shende S., Gupta I., et al. (2018). Copper and copper nanoparticles: Role in management of insect-pests and pathogenic microbes. Nanotechnol. Rev. 7, 303–315. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2018-0031

Ramamoorthi K. and Lin Y. (2011). The contribution of gabaergic dysfunction to neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 17, 452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.03.003

Ramos-Zuniga J., Bruna N., and Perez-Donoso J. M. (2023). Toxicity mechanisms of copper nanoparticles and copper surfaces on bacterial cells and viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 10503. doi: 10.3390/ijms241310503

Rotini A., Tornambè A., Cossi R., Iamunno F., Benvenuto G., Berducci M. T., et al. (2017). Salinity-based toxicity of cuo nanoparticles, cuo-bulk and cu ion to vibrio Anguillarum. Front. Microbiol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02076

Salvo J. and Sandoval C. (2022). Role of copper nanoparticles in wound healing for chronic wounds: Literature review. Burns Trauma 10, tkab047. doi: 10.1093/burnst/tkab047

Saquib Q., Al-Khedhairy A. A., Siddiqui M. A., Abou-Tarboush F. M., Azam A., and Musarrat J. (2012). Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and DNA damage in human amnion epithelial (wish) cells. Toxicol. In Vitro. 26, 351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.12.011

Sielska A. and Skuza L. (2025). Copper nanoparticles in aquatic environment: Release routes and oxidative stress-mediated mechanisms of toxicity to fish in various life stages and future risks. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 47, 472. doi: 10.3390/cimb47060472

Simon D. F., Domingos R. F., Hauser C., Hutchins C. M., Zerges W., and Wilkinson K. J. (2013). Transcriptome sequencing (rna-seq) analysis of the effects of metal nanoparticle exposure on the transcriptome of chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4774–4785. doi: 10.1128/aem.00998-13

Song L., Connolly M., Fernández-Cruz M. L., Vijver M. G., Fernández M., Conde E., et al. (2013). Species-specific toxicity of copper nanoparticles among mammalian and piscine cell lines. Nanotoxicology 8, 383–393. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.790997

Su J., Song Y., Zhu Z., Huang X., Fan J., Qiao J., et al. (2024). Cell-cell communication: New insights and clinical implications. Signal Transduction Target Ther. 9, 196. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01888-z

Tan B., Wang Y., Gong Z., Fan X., and Ni B. (2022). Toxic effects of copper nanoparticles on paramecium bursaria-chlorella symbiotic system. Front. Microbiol. 13, 834208. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.834208

Tao B., Lin C., Deng Y., Yuan Z., Shen X., Chen M., et al. (2019). Copper-nanoparticle-embedded hydrogel for killing bacteria and promoting wound healing with photothermal therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 7, 2534–2548. doi: 10.1039/c8tb03272f

Thiagarajan V., M P., S A., R S., N C., G.K S., et al. (2019). Diminishing bioavailability and toxicity of p25 tio2 nps during continuous exposure to marine algae chlorella sp. Chemosphere 233, 363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.270

Tortella G. R., Pieretti J. C., Rubilar O., Fernandez-Baldo M., Benavides-Mendoza A., Diez M. C., et al. (2022). Silver, copper and copper oxide nanoparticles in the fight against human viruses: Progress and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 42, 431–449. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2021.1939260

van der Oost R., B. J., and Vermeulen N. P. E. (2002). Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 13, 57–149. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(02)00126-6

Vrijens K., Bollati V., and Nawrot T. S. (2015). Micrornas as potential signatures of environmental exposure or effect: A systematic review. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 399–411. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408459

Wang Y., Yuan S., Jia X., Ge Y., Ling T., Nie M., et al. (2019). Mitochondria-localised znfx1 functions as a dsrna sensor to initiate antiviral responses through mavs. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 1346–1356. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0416-0

Win-Shwe T. T. and Fujimaki H. (2011). Nanoparticles and neurotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 6267–6280. doi: 10.3390/ijms12096267

Wu D., Khan F. A., Zhang K., Pandupuspitasari N. S., Negara W., Guan K., et al. (2024). Retinoic acid signaling in development and differentiation commitment and its regulatory topology. Chem. Biol. Interact. 387, 110773. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110773

Yimeng S., Huilun X., Ziming L., Kejun L., Chaima M., Xiangyu Z., et al. (2022). Copper-based nanoparticles as antibacterial agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 26, e202200614. doi: 10.1002/ejic.202200614

Yu Z., Li Q., Wang J., Yu Y., Wang Y., Zhou Q., et al. (2020). Reactive oxygen species-related nanoparticle toxicity in the biomedical field. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 115. doi: 10.1186/s11671-020-03344-7

Yu Q., Zhang Z., Monikh F. A., Wu J., Wang Z., Vijver M. G., et al. (2022). Trophic transfer of cu nanoparticles in a simulated aquatic food chain. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 242, 113920. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113920

Yudaev P., Mezhuev Y., and Chistyakov E. (2022). Nanoparticle-containing wound dressing: Antimicrobial and healing effects. Gels 8, 329. doi: 10.3390/gels8060329

Zanger U. M. and Schwab M. (2013). Cytochrome p450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 138, 103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007

Zhang Y., Ding Z., Zhao G., Zhang T., Xu Q., Cui B., et al. (2018). Transcriptional responses and mechanisms of copper nanoparticle toxicology on zebrafish embryos. J. Hazard. Mater. 344, 1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.11.039

Keywords: copper nanoparticles, marine medaka, miRNA-seq, mRNA-seq, toxicity

Citation: Ren P, Zhang P, Shi J, Li H, Jin R and Li H (2026) Particle size–dependent molecular perturbations induced by copper nanoparticles in marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma): an integrated miRNA–mRNA analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1758043. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1758043

Received: 01 December 2025; Accepted: 07 January 2026; Revised: 29 December 2025;

Published: 26 January 2026.

Edited by:

Mingzhe Yuan, Ningbo University, ChinaCopyright © 2026 Ren, Zhang, Shi, Li, Jin and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruofei Jin, anJ1b2ZlaUBkbHV0LmVkdS5jbg==; Hongjun Li, aGpsaUBubWVtYy5vcmcuY24=

Pengrui Ren1

Pengrui Ren1 Hongjun Li

Hongjun Li