Abstract

Ocean acidification (OA) generally receives far less consideration than other climate stressors and related hazards, such as global warming and extreme weather events. Canada is uniquely vulnerable to OA given its extensive coastal oceans, the oceanographic processes in its three basins, accelerated warming and sea-ice melt, and extensive coastal communities and maritime economic sectors. Canada’s coastline is also home to extensive and diverse First Nations peoples with distinct histories, rights, title, laws, governance and whose traditions and cultures are extrinsically linked to the sea. However, there are currently very limited pathways to support OA action, mitigation, and/or adaptation in Canada, particularly at the policy level. Here, we present a first synthesis of the current state of OA knowledge across Canada's Pacific, Arctic, and Atlantic regions, including monitoring, modelling, biological responses, socioeconomic and policy perspectives, and examples of existing OA actions and efforts at local and provincial levels. We also suggest a step-wise pathway for actions to enhance the coordinated filling of OA knowledge gaps and integration of OA knowledge into decision-making frameworks. The goals of these recommendations are to improve our ability to respond to OA in Canada, and minimize risks to coastal marine environments and ecosystems, vulnerable sectors, and communities.

1 Introduction

Ocean acidification (OA) driven by anthropogenic CO2 emissions alters seawater chemistry and is being pushed past planetary boundaries (Findlay et al., 2025b), posing a wide range of threats to marine organisms, ecosystems, and ecosystem services (Orr et al., 2005; Doney et al., 2020; IPCC, 2023). Canada is particularly vulnerable to OA given its extensive coastline and marine resource utilization spanning three ocean basins (Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2013; Azetsu-Scott, 2018; Niemi et al., 2021). Furthermore, naturally weakly-buffered seawaters, shaped by regional conditions in all three of Canada’s ocean basins, are being pushed beyond key thresholds by the uptake of anthropogenic CO2 emissions. For example, the cold waters surrounding Canada have a naturally lower calcium carbonate saturation state, as carbonates are more soluble in colder waters (Revelle and Fairbridge, 1957; Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2009, 2013; Shadwick et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2020). Regionally, vulnerabilities also include weakly-buffered seawater due to circulation patterns of “old” waters enriched in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), freshwater input, and seasonal upwelling in the Pacific (Tortell et al., 2012; Haigh et al., 2015; Engida et al., 2016; Moore-Maley et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2019, 2022, 2025; Cai et al., 2020; Franco et al., 2021; Holdsworth et al., 2021; Jarníková et al., 2022), increased freshwater input from glacial/sea-ice melt and terrestrial runoff and enhanced atmospheric CO2 update from declining sea-ice cover in the Arctic (Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2009, 2025; Azetsu-Scott et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2014; Evans et al., 2015; Mathis et al., 2015; Steiner et al., 2015; Bianucci et al., 2018; Moore-Maley et al., 2018; Pilcher et al., 2018; Hare et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2021; Niemi et al., 2021; Steiner and Reader, 2024), and circulation conditions causing increased atmospheric CO2 uptake (Azetsu-Scott et al., 2010) and stratification/bottom water acidification in the Atlantic (Mucci et al., 2011; Lavoie et al., 2021; Nesbitt and Mucci, 2021; Gibb et al., 2023; Galbraith et al., 2025). Canada’s extensive coastline and reliant coastal communities will therefore be increasingly vulnerable due to the impacts of OA and climate change on marine ecosystems (Barton et al., 2015; Ekstrom et al., 2015; Haigh et al., 2015; Mathis et al., 2015; Hall-Spencer and Harvey, 2019).

The wide range of OA conditions and drivers, the longest coastline of any country in the world, and the diversity of regional ecosystems, communities, and economies creates challenges for delivering consistent OA information and coordinating research, policies, mitigation, and adaptation actions across Canada. The rapid emergence of ocean climate mitigation initiatives, such as marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) and offshore carbon storage, internationally and in Canada, further underscores the urgent need for enhanced coordinated OA research capacity to establish baselines, and could be used to verify carbon sequestration effectiveness. While ocean climate interventions may provide some benefits through locally ameliorating OA (Zhou et al., 2024), there is little known about the impacts and risks to marine ecosystems, again highlighting the role that established scientific baselines and expertise can provide to assessments of carbon mitigation activities. The Canadian OA Community of Practice (OA CoP)1 was established in 2018 as a mechanism to bring together researchers, sectors, and impacted communities to aid in unifying Canada’s response to OA, and is a UN Decade-endorsed project under the Ocean Acidification Research for Sustainability (OARS) Programme. The following community perspective paper represents the OA CoP’s efforts to synthesize the current state of OA knowledge in Canada. This multidimensional assessment of current and projected impacts of OA in Canada includes an integration of OA scientific information (physical, chemical, biological) and highlights socio-economic vulnerabilities, policy progress and perspectives, and current OA action planning processes and initial actions taken. The assessment also identifies key resources requiring sustained support to enable well-informed policies, and provides recommendations for areas of OA knowledge enhancement to promote adaptation planning for Canadian ecosystems, coastal resources, livelihoods, and communities.

2 State of OA knowledge in Canada

2.1 Overview

2.1.1 Ongoing OA research efforts in Canada

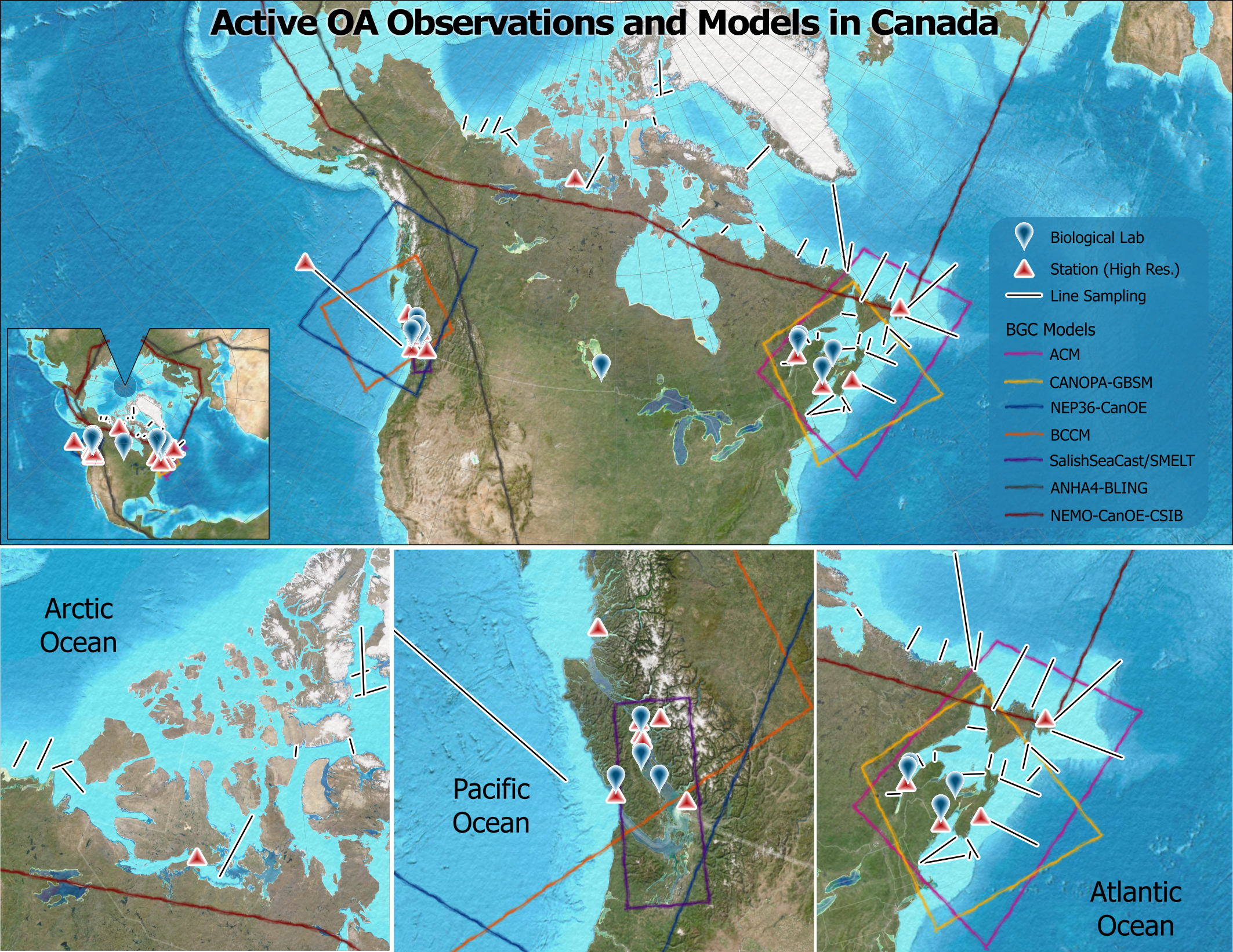

OA research in Canada includes monitoring, modelling, and biological experiments, which inform assessments of socioeconomic exposure, vulnerability, and policy needs for OA adaptation and mitigation in Canada. This research also contributes to global analyses of species and ecosystem responses to OA (Widdicombe et al., 2023) and helps improve global OA and climate model forecasts. With over 150 members, the OA CoP has a considerable institutional knowledge of OA research efforts in Canada and has concatenated metadata on existing Canadian research in collaboration with members. The metadata gathered from the community was compiled (Supplementary Tables S1, S2) and used to generate both static (Figure 1) and dynamic2 maps for Canadian OA research infrastructure (e.g., cruise lines, sampling stations, laboratories, models). Ongoing efforts are expected to capture information missed during this first stock-take and to incorporate new data as activities come online. To date, this activity represents the most comprehensive assessment of Canada’s OA research infrastructure, serving as important context to aid coordination efforts across the country.

Figure 1

Map of Canada’s OA research assets, including biological labs, cruise lines and moorings, and biogeochemical model domains. This figure only contains active, Canada-based OA resources at the time of publication. A dynamic version of this map will be regularly updated, and is available at https://arcg.is/nWnTa0. The online version of the map also includes inactive/past assets and US-based assets in Canadian waters, as well as links to relevant citations/webpages.

2.1.2 National and international OA science collaboratives

Nationally, there is formal federal science collaboration through the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Ocean Chemistry Working Group, which is further enhanced internationally through the bilateral federal DFO-NOAA (National Oceanic Atmospheric and Administration) Working Groups. The monitored state of OA is included in DFO State of the Oceans Reports, such as the 2024 State of Canada’s Arctic seas report (Niemi et al., 2024) and the 2025 Atlantic report (Galbraith et al., 2025). Other coordinated OA research efforts in Canada include those through the Marine Environmental Observation, Prediction and Response (MEOPAR) network, promoting societal understanding through science knowledge translation (e.g. the OA CoP). Besides supporting the OA CoP, MEOPAR has also funded and contributed to ongoing independent OA research projects in all regions of Canada (Tai et al., 2018, 2019, 2021a, b; Menu-Courey et al., 2019; Steiner et al., 2019; Stevenson et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2020; Noisette et al., 2021). Other international coordination efforts involving Canada include the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON)3 regional North American and Arctic Hubs. Internationally, the OSPAR 2023 Ocean Acidification Assessment (McGovern et al., 2022) highlighted current and future trends, impacts, and mitigation and adaptation needs, including those consistent with management of OA in association with climate change regionally in Canada. While we recognize the importance of these highly valuable long-term collaborations, particularly those with the US, the focus of this paper is strictly on Canada-generated OA assets. Furthermore, although these platforms and groups develop scientific consensus and may provide advice to respective governments, there is no direct linkage to policymaking.

2.2 Monitoring

2.2.1 Monitoring overview

Canada’s OA observations are multi-institutional, involving government agencies, universities, and not-for-profit organizations. As such, OA data collection in Canada spans a wide range of techniques and applications reflective of the wide range of coastal environments that exist within Canadian Economic Exclusion Zones (EEZ). Here we classify marine domains within the Canadian EEZ as: offshore (deep ocean basins with depths exceeding 600 m), continental shelf (exposed waters with depths shallower than 600 m, including deep canyons that incise the broader portions of the Pacific continental shelf), and nearshore (waters within 20 km of land, accessible by small boats, including semi-enclosed seas, fjords, etc.). The OA CoP strives to help coordinate these diverse data collection activities and minimize the risks of data gaps emerging.

A strength of the Canadian approach is that OA monitoring programs exist on all three coasts, including measurement programs with time-series spanning multiple decades that include Line P in the Pacific beginning in 1990 (Franco et al., 2021) and the central Labrador Sea AR7W repeat hydrography line beginning in 1986 (Raimondi et al., 2021). These records are long enough to statistically resolve secular trends, and this ability is expected to emerge for other Canadian time-series over the next decade. Other data collected within each ocean basin surrounding Canada provide important regional baseline information and can identify locations and time periods of heightened vulnerability or refugia from acidification (Figure 1). Below, we provide an overview of monitoring efforts for each region.

2.2.2 Observations of OA in the Pacific

A number of federal, academic, and private research programs are currently operating along the Canadian Pacific coast to document spatio-temporal variability (e.g., characterization of regional OA hotspots and areas of refugia, identifying marine ecosystem vulnerabilities, and developing long-term time-series measurements) (Evans et al., 2023). Organizations that maintain these programs include DFO, the Hakai Institute, and Ocean Networks Canada (ONC). The Province of British Columbia (BC) has also provided support through the Climate Ready BC Seafood Program4 that funds a variety of smaller observing projects that are distributed along Canada’s Pacific Coast to address actions identified in the BC OA and Hypoxia (OAH) Action Plan (British Columbia Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Action Plan Advisory Committee, 2023). Despite these efforts, large regions of the Canadian Pacific coast remain poorly sampled (Evans et al., 2023).

A description of OA patterns along Canada’s Pacific coast must begin with the deep Northeast Pacific basin that contains some of the lowest pH and most corrosive water in the upper 1000 m of the global ocean due to the flow-path of ocean circulation, organic matter remineralization along this flow-path, and anthropogenic CO2 input (Lauvset et al., 2020). Aragonite and calcite become undersaturated (Ω< 1) at depths of around 185 and 340 m, respectively, shoaling at rates between 1 and 1.7 m yr-1 (Ross et al., 2020). For detailed definitions of carbonate parameters, see glossaries from the IPCC (IPCC, 2019) and Scientific Assessment for the BC OAH Action Plan (Evans et al., 2023). Seawater corrosive to aragonite spans the continental shelf during summer and can reach the surface during periods of upwelling-favorable winds (Feely et al., 2008, 2018). Intensifying OA due to the continual addition of anthropogenic CO2 (Carter et al., 2019; Gruber et al., 2019; Franco et al., 2021) alters the extent, duration, and intensity of exposure to low pH and corrosive conditions for vulnerable marine organisms (Hauri et al., 2013; Feely et al., 2016). To date, only Line P in the Northeast Pacific can reliably detect these long-term changes in marine carbonate parameters (Franco et al., 2021). Global anthropogenic carbon has decreased pH by an estimated 0.13 units since the Industrial Revolution (Jiang et al., 2019) at rates ranging from -0.0011 to -0.0017 yr-1 in surface waters of the Northeast Pacific (Franco et al., 2021). Statistical models using observations to help fill the gaps in multi-decadal time-series have estimated the increasing trend in surface seawater pCO2 to be 1.4 uatm yr-1 (Duke et al., 2023). These estimates are comparable to Franco et al. (2021) who report increasing trends in pCO2 and salinity-normalized DIC in surface water of 1.0 to 1.6 µatm yr-1 and 0.5 to 0.8 µmol kg-1 yr-1, respectively, and Carter et al. (2019), who provided an estimate of 0.7 µmol kg-1 yr-1 change in DIC at high latitudes in the Pacific. The most up-to-date estimate of total anthropogenic CO2 content and its rate of change is 73.3 µmol kg-1 and near 1.0 µmol kg-1 yr-1, respectively, for Northeast Pacific surface water in 2021 (Feely et al., 2024).

Moving from the open Northeast Pacific to the continental shelf and nearshore waters, marine CO2 patterns within these areas exhibit large variability owing to the myriad of physical and biological processes unique to the land-ocean boundary. Pacific continental shelf and nearshore domains contain the areas of highest primary productivity (Ware and Thomson, 2005; Jackson et al., 2015), while also receiving significant land runoff (Morrison et al., 2012; Giesbrecht et al., 2022) and experiencing substantial physical forcing from winds and tides. Several regions along the Canadian Pacific coast have been documented as being highly sensitive to increasing anthropogenic CO2 content because of weak buffering conditions. These conditions lead to extremes in the extent, intensity, and frequency of exposure to acidified seawater, including in the Salish Sea (Ianson et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2019, 2025; Simpson et al., 2022), in select adjacent fjords (Hare et al., 2020), and in portions of the Inside Passage (Evans et al., 2022) network of waterways used for transport along the BC coast. Estimates and projections suggest a range of anthropogenic CO2 content in these settings with a maximum equivalent to open ocean estimates (Evans et al., 2019, 2022; Hare et al., 2020; Simpson et al., 2022; Duke et al., 2024). Also, a 40% increase in acidity that exceeds the global average (Evans et al., 2022), and the potential for an additional 15% increase in acidity at an atmospheric CO2 level consistent with a 1.5°C warmer world is expected by 2035 (Evans et al., 2022; Riahi et al., 2022).

2.2.3 Observations of OA in the Arctic

Monitoring efforts in the Canadian Arctic are driven by government, academic institutions (e.g., University of Calgary, University of Manitoba), ONC, and through research organizations, such as ArcticNet and Amundsen Science. Canadian collaborations with international monitoring assessments include the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Ship-based cruises include GO-SHIP lines in the Davis Strait, and research cruises in Hudson Bay, Baffin Bay, the Beaufort Sea, and Northwest Passage. DFO collaborates with NOAA and academic colleagues on the Distributed Biological Observatory - a systematic observation network to monitor change in the Pacific sector of the Arctic (Grebmeier et al., 2019). Collaborations with local communities and researchers are essential to provide frequent observations, particularly over the winter, however, the majority of data collection occurs over the ice-free summer months. Community-run infrastructure, such as the Cambridge Bay Observatory (in partnership with ONC), provides year-round data through its underwater cabled sensors. DFO and individual researchers also work closely with several Arctic communities to provide data collection and assess community priorities, including in connection with the Canadian Rangers Ocean Watch program (CROW) (Williams et al., 2018; Laenger et al., in prep).

Arctic waters in Canada are particularly susceptible to acidification, due to a unique combination of cold water, sea-ice dynamics, and high freshwater content. The Arctic receives a disproportionate supply of riverine freshwater, making the entire ocean basin susceptible to low aragonite (ΩA) saturation (Terhaar et al., 2020). Areas of regional upwelling like the Beaufort Sea (Mucci et al., 2010; Chierici et al., 2011; Mathis et al., 2015) also contribute brief periods of ΩA undersaturation in the surface layer. Seasonal undersaturation of ΩA in surface seawater has been identified in summer in the Canada Basin (Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2009, 2025) and in the southwest portions (the “Kitikmeot Sea” (Williams et al., 2018)) of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Chierici and Fransson, 2009; Beaupré-Laperrière et al., 2020). Summer observations of ΩA in Hudson Bay have revealed consistent undersaturation of surface waters in a narrow band along the southeast coast of the Bay (Azetsu-Scott et al., 2014; Burt et al., 2016). Undersaturated ΩA has not been observed to date in surface waters of the eastern Archipelago or Baffin Bay (Chierici and Fransson, 2009; Ahmed et al., 2019; Else et al., 2019; Beaupré-Laperrière et al., 2020; Burgers et al., 2023).

Like in many regions, ΩA undersaturation is common in subsurface waters of the Canadian Arctic. Inflowing Pacific water from the Bering Strait, which forms the upper halocline layer (~100–200 m depth), has a low ΩA signal due to remineralization of organic material formed in the highly productive Bering Sea. Miller et al. (2014) identified undersaturated ΩA in this layer in the Canada Basin and Beaufort Sea since the 1970s, and other observers have similarly found undersaturated ΩA at depths where this layer occurs, including in the Amundsen Gulf (Niemi et al., 2021), Hudson Bay (Burt et al., 2016) and Nares Strait (Burgers et al., 2023). For much of the Canadian Arctic, ΩA undersaturation is not observed until much greater depths: around 700 m in Baffin Bay (Beaupré-Laperrière et al., 2020), and 2000 m in the Canada Basin (Miller et al., 2014). One notable exception is the shallow (typically <300 m depth) Kitikmeot Sea, where ΩA undersaturation has been observed throughout the water column (Beaupré-Laperrière et al., 2020). In winter, Duke et al. (2021) observed a sustained 4.5-month period of ΩA undersaturation conditions, also in the Kitikmeot Sea, attributed to processes occurring beneath the sea ice (brine rejection, remineralization, and restriction of gas exchange) unique to polar seas.

Measurements of pCO2 in the western coastal Arctic (Evans et al., 2015), the Canada Basin (DeGrandpre et al., 2020), Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Ahmed et al., 2019), Hudson Bay (Else et al., 2008; Ahmed et al., 2021), and Baffin Bay (Nickoloff et al., 2024) all show substantial uptake of atmospheric CO2. These strong sinks are commonly attributed to cold surface water temperatures, but ice-associated phytoplankton blooms and other sea ice processes may play an important role (Rysgaard et al., 2009). As sea-ice, particularly in the winter, prevents outgassing, studies generally conclude that loss of sea ice has increased CO2 uptake in the Arctic, primarily by exposing a greater portion of the Arctic surface ocean to the atmosphere for longer time periods (DeGrandpre et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2024). Miller et al. (2014) used a dataset from 1974 to 2009 collected in the Canada Basin and the Beaufort Sea, and found that ΩA was highly variable but generally decreasing in deep waters and the Pacific halocline layer. Studying a dataset collected across the Canadian Arctic from 2003 to 2016, Beaupré-Laperrière et al. (2020) was unable to detect any trends in ΩA, but did calculate time of emergence of OA signals to be on the order of 20–25 years of continuous observations. Other studies have placed their short-term observations in the context of likely changes due to acidification; for example, Duke et al. (2021) used an estimate of the anthropogenically-driven DIC load to show that the prolonged period of undersaturated ΩA they observed over winter would have been unlikely to occur during pre-industrial times.

2.2.4 Observations of OA in the Atlantic

Since 1998, DFO’s Atlantic Zone Monitoring Program (AZMP) has tracked seasonal and interannual variability in Atlantic Canadian waters, with OA parameters routinely included since 2014 to support resource management (Gibb et al., 2023; Galbraith et al., 2025). The core sampling protocol of the AZMP consists of seasonal seagoing surveys along predefined hydrographic sections, with more frequent sampling at specific stations on the Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) shelf, the Scotian shelf, Bedford Basin, the Gulf of Maine, and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (GSL) (Figure 1) (Galbraith et al., 2025). Additional Atlantic monitoring includes the Atlantic Zone Offshelf Monitoring Program (AZOMP) line AR7W which extends ~900 km from the Labrador to the Greenland shelves to produce a time-series of the Labrador Sea since 1996 (Ringuette et al., 2025). Other programs include the Bedford Basin Monitoring Program and the Rimouski station time-series from the St. Lawrence Estuary (Galbraith et al., 2025).

Atlantic marine waters of Canada host a unique combination of Arctic, subarctic and sub-tropical waters, and receive a significant influx of freshwater originating from the St. Lawrence Estuary, which transits through the Gulf before reaching the Atlantic. In the northern part of the Atlantic region, the Labrador Coastal Current delivers cold, relatively fresh, and low pCO2 Arctic waters to the region. Near the surface, ΩA increases from spring to fall on the NL and Scotian shelves mainly due to the seasonal increase in temperature (Gibb et al., 2023). Surface DIC decreases from spring to summer during plankton blooms, then increases from summer to fall due to the remineralization of sinking organic matter, particularly at depth (Gibb et al., 2023). Labrador Slope Water (LSlW), formed from the mixing of the Labrador Current and North Atlantic Current near the Grand Banks, have low oxygen levels and calcium carbonate saturation states (e.g., ΩA typically < 2) (Gilbert et al., 2005; Jutras et al., 2020; Gibb et al., 2023). A portion of the LSlW delivers relatively cool and fresh waters to the Scotian shelf and the northeast US coast (New et al., 2021). These regions also receive fresh and acidic surface waters that flow out of the GSL via the western part of Cabot Strait. The low ΩA signal of the LSlW and GSL can be traced all the way to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico (Wanninkhof et al., 2015).

A portion of the LSlW also enters the Laurentian Channel along the continental slope, forming the deep waters of the GSL. These waters become isolated from the atmosphere and oxygen-depleted due to the remineralization of sinking organic matter as they are slowly advected inland by estuarine circulation, with surface waters flowing seaward and mid- and bottom-waters flowing landward (Mucci et al., 2011). These processes also increase DIC resulting in the highest pCO2, and lowest pH and Ω values along the deep Laurentian channel, especially in the St. Lawrence Estuary (see below).

Since systematic monitoring began in 2014, annual values of pH across the Canadian Atlantic zone have exhibited substantial spatial and vertical variability, ranging from approximately 7.5 in bottom waters of the LSLE and GSL to values above 8 in surface waters off Labrador, with the highest pH generally observed along the shelf in summer (Gibb et al., 2023; Galbraith et al., 2025). Most of the bottom waters of the GSL and the Lower St. Lawrence Estuary (LSLE) are permanently undersaturated with respect to aragonite, ΩA also occasionally falls below saturation in the Avalon Channel, on the Grand Banks, in the deepest part of the Newfoundland Shelf slope, and on the eastern Scotian Shelf. While pH in the bottom waters of the LSLE is believed to have decreased by 0.2 to 0.3 units between the 1930s and the early 2000s (Mucci et al., 2011), this decrease has accelerated over the recent years potentially linked to the increased influence of warmer LSlW waters in the deepest GSL layers, resulting in a significant reduction of pH since about 2020 (Galbraith et al., 2025). Overall, surface waters in Atlantic Canada appear to be acidifying particularly rapidly, with pH declining by 0.03–0.04 units per decade (Bernier et al., 2023), faster than the global average decline of 0.017–0.027 units per decade (Orr et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2019; IPCC, 2021).

2.3 Modelling

2.3.1 Modelling overview

Ocean models are an essential complement to observations. Numerical ocean models can help interpret observations, which are often sparse in time and space (e.g., de Mora et al., 2013). Models represent testable hypotheses that can elucidate mechanistic relationships, and can be used for attribution of observed events (e.g., Kirchmeier-Young et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). Models are particularly needed when trying to better understand the future effects of climate change as they are the only tool at our disposal to estimate future ocean states and related uncertainties.

Ocean model simulations generally fall into three categories: hindcasts, projections and predictions. Hindcasts are reconstructions of past ocean states using ocean models forced with observed (or reconstructed) atmospheric forcing (e.g., Peña et al., 2019; Mortenson et al., 2020; Lavoie et al., 2021; Han et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024; Holdsworth et al., 2025), and can reproduce the timing of climate-variability events like El Niño. Projections are made using global coupled (ocean-atmosphere) models based on future socioeconomic pathways (e.g., Moss et al., 2010), but do not accurately represent year-to-year variability. These coarse-resolution global climate models may be downscaled to higher-resolution regional ocean models (Holdsworth et al., 2021). Predictions are short-term (days to a few years) forecasts based on the current ocean state and operate similar to weather forecasts. Canada currently maintains operational systems for both seasonal-to-decadal predictions and near-term (<10 days) forecasts of the physical ocean state (Lin et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2021), but these do not yet include biogeochemistry.

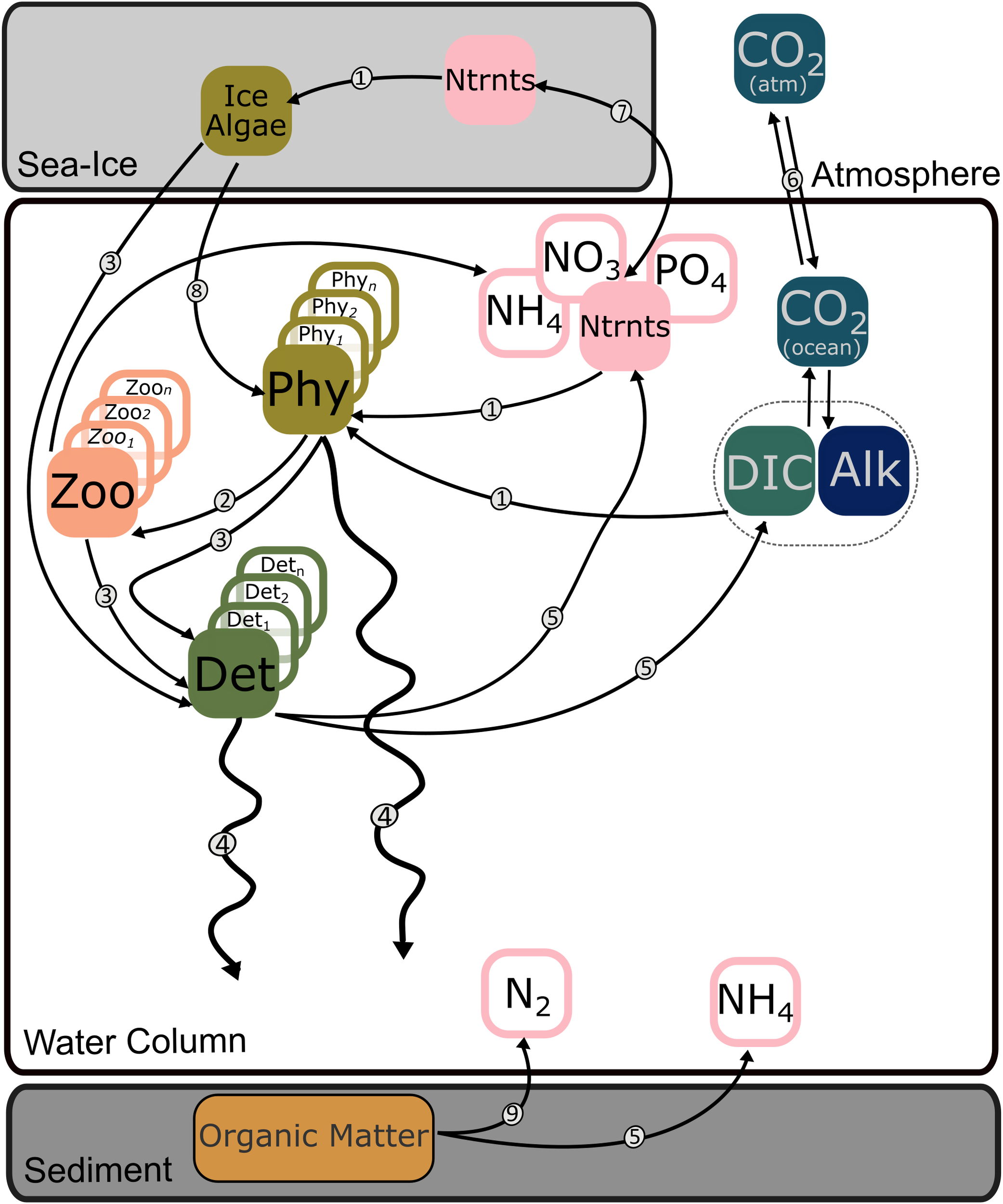

Ocean models are based on general circulation models, which provide the framework of ocean circulation, stratification, and mixing. Additional biogeochemical modules embedded within the general circulation model include components, such as carbon chemistry, air-sea gas exchange, biological uptake and remineralization of carbon and other elements (e.g., N, P, Fe), and external nutrient sources and sinks (e.g., rivers, atmospheric deposition, burial in the sediments). Ocean biological modules usually include at least one nutrient element (e.g., N or P), phytoplankton and zooplankton, and some representation of particle sinking and remineralization. Figure 2 shows a generic biogeochemical model structure. Biological models of increasing complexity include more components such as multiple phytoplankton groups; some also include heterotrophic bacteria and dissolved organic matter (e.g., Christian and Anderson, 2002).

Figure 2

Generic schematic of a simplified biogeochemical model including sea-ice. Squares represent model variables; circled numbers indicate modelled processes. Potential variables included are various nutrients (Ntrnts), DIC, alkalinity (Alk), one or more phytoplankton (Phy) groups, one or more zooplankton (Zoo) groups, one or more size classes of detritus (Det), and ice algae. Processes included are: 1 – nutrient and DIC uptake; 2 – grazing; 3 – mortality; 4 – sinking; 5 – remineralization; 6 – air-sea gas exchange; 7 –mixing and upwelling; 8 – seeding of ice algae; 9 – denitrification. Abiotic effects of sea ice formation on DIC and alkalinity (Mortenson et al., 2020) are not represented.

The high complexity of Canadian waters, which encompass complex coastlines, shallow shelves, deep fjords as well as seasonal and perennial sea ice, emphasizes the need for regional models, which allow to better represent coastal and bathymetric features, and the use of models which include sea ice dynamics and biogeochemical exchange processes for some regions. These biogeochemical models can produce a three-dimensional estimate of OA for both past and (projected or predicted) future climates. Higher trophic levels such as fish have little direct effect on ocean biogeochemical cycles and are not represented directly in the models, i.e., they are usually the subject of ‘downstream’ studies of biological impacts (see Biological responses section below).

2.3.2 Canadian OA trends in global models

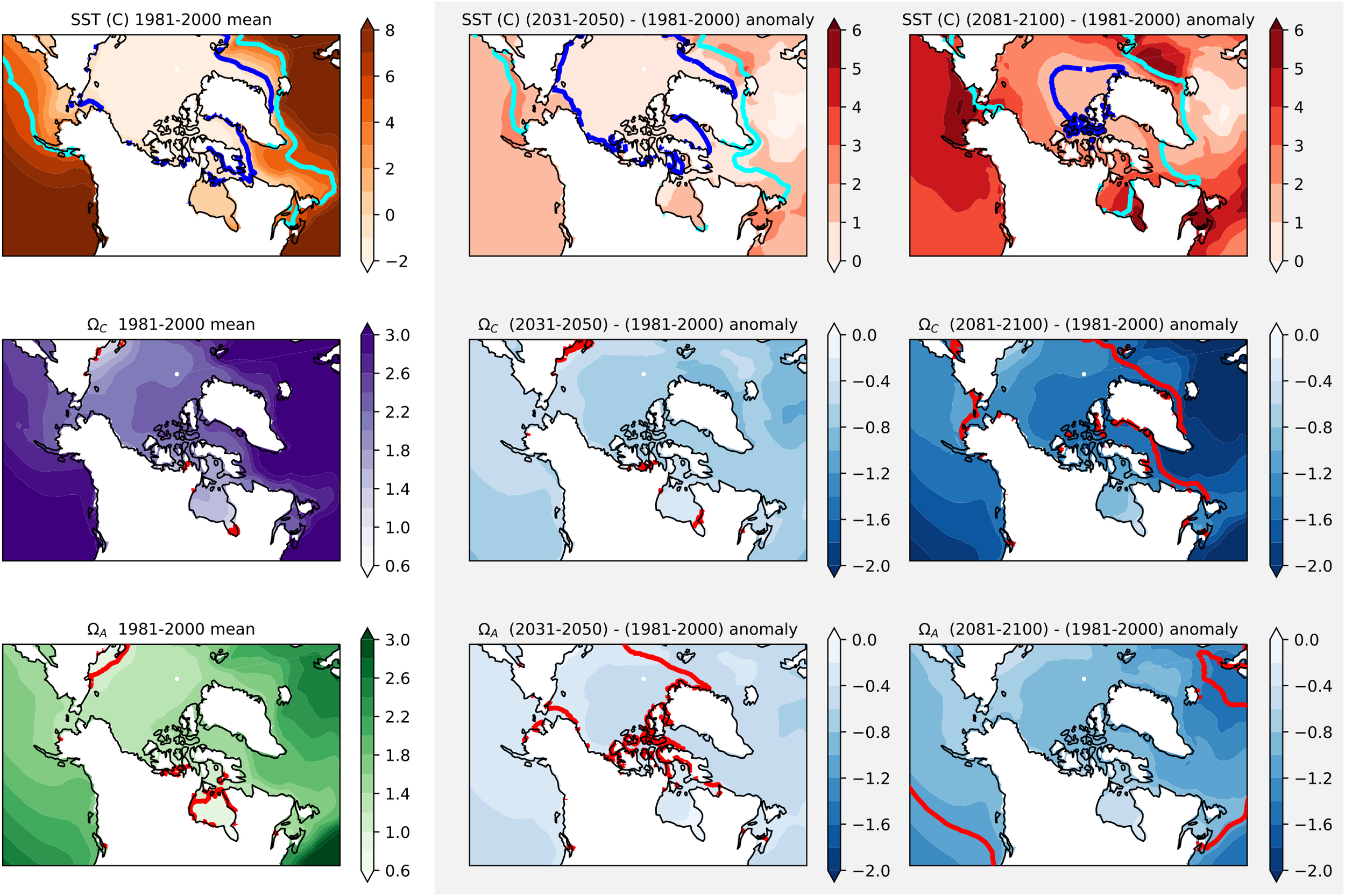

Many Earth System Models (ESMs) contributing to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) now include ocean biogeochemistry, allowing us to assess projections covering Canada’s three oceans (Séférian et al., 2020). Figure 3 shows the annual mean temperature and CaCO3 (calcite, aragonite) saturation state for 1981–2000 and projected changes by the mid- (2031-2050) and late (2081-2100) 21st century using the average of 10 CMIP6 models (expanded from Steiner and Reader, 2024) under the high emission scenario, SSP585. The models show warmest waters in the Canadian Pacific and Atlantic, with the largest warming rate in the Pacific Arctic region and between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. OA is projected to be most advanced in the Arctic, particularly the Pacific Arctic and Hudson Bay. Trends are fairly consistent across Canada’s Three Oceans. Given the advanced OA in the Arctic, many regions are already undersaturated with respect to aragonite or projected to be by 2100 (calcite undersaturation is also projected to occur in many regions). This is consistent with Terhaar et al. (2021), who noted good agreement with respect to OA projections over the 21st century for CMIP6 models, with reduced model uncertainties (~50%) compared to CMIP5. For the multi-model mean projections, the rate of reduction of aragonite and calcite saturation state averaged over the upper 1000 m is independent of the emission pathway until around 2040, and diverges afterwards (Terhaar et al., 2021; Steiner and Reader, 2024). Both ΩA and ΩC show the same regional trend pattern. In sea-ice regions, decrease in saturation state parallels the decrease in sea-ice over time, which shows large differences in pace and timing across models. The initial acceleration is linked to CO2 uptake via increased atmospheric CO2 and melting sea-ice, while ocean warming becomes a strong driver in the late 21st century.

Figure 3

Maps of simulated temperature (top row), and surface ocean aragonite (ΩA, middle row) and calcite saturation state (ΩC, bottom row) from model output for the historical climate (1981-2000) (left panels) and projected changes for the mid- (2031–2050 minus 1981-2000, middle panels) and late (2081–2100 minus 1981-2000, right panels) 21st century, with projected changes (middle and right columns) highlighted by a shaded box. The right-hand colour bars for the left column indicate mean simulated temperature/saturation states for 1981-2000, whereas the colour bars for the middle and right plots on each row represent the anomalies with respect to 1981-2000. Dark blue lines indicate the 0°C contour, cyan the 5°C contour and red the Ω=1 contour. Model estimates are calculated from DIC, alkalinity, temperature, and salinity from Earth System Model simulations and are the mean of ten models (ACCESS-ESM1-5, CanESM5-CanOE, CESM2-WACCM, CNRM-ESM2-1, GFDL-ESM4, MIROC-ES2L, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2-0, NorESM2-MM, and UKESM1-0-LL). Future projections are for the high-emission scenario SSP585.

In deeper layers, model biases are smaller and stay more consistent over time, but the multi-model mean evolution is similar, with faster paced acidification during mid-century (not shown). Differences among regions are largely retained over time. By late century, essentially the same OA trends are simulated across depths, indicating not only an accelerated pace of OA but also deepening of the acidification signal, which is consistent with previous analyses of CMIP5 models (Steinacher et al., 2009; Steiner et al., 2014).

All Canadian Arctic ocean regions are projected to be aragonite undersaturated by 2060 for SSP245 and SSP585 (shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) applied in CMIP6), for at least the top 200 m (IPCC, 2021). For calcite, the multi model mean remains supersaturated in SSP245, as do most individual models, but undersaturation occurs by 2085 for SSP585. A key driver is the reduction in sea ice (Steiner and Reader, 2024). Trends show little difference among scenarios before 2040. After 2040, higher emission scenarios show faster acidification progression. Some Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, including the Beaufort Sea, reach aragonite undersaturation by the 2010s, consistent with observations (Niemi et al., 2021) and regional model results (Mortenson et al., 2020). For other regions, undersaturation can still be avoided with lower emissions.

The seasonal amplitude of near-surface ocean temperature is increasing within areas of sea-ice retreat (Steiner and Reader, 2024). Carbon system variables show a less pronounced increase in seasonal range, but the maximum pH and Ω may shift earlier by 1–2 months. Steiner et al. (2013) showed that projected sea-ice retreat alters seasonal CO2 flux by enhancing uptake in fall and reducing uptake in summer. Seasonal extremes are important for biological impacts (McNeil and Matear, 2008; Sasse et al., 2015) and how these evolve in the future may vary greatly among the diverse regions of Canada’s oceans.

Projections of species impacts (Tai et al., 2021b) suggest that invertebrates in the Arctic are most at risk from OA; however, these authors emphasized the uncertainty of the projections. In particular, ESM acidification projections are most robust for the open ocean where changes are strongly driven by atmospheric CO2. However, harvested invertebrates inhabit coastal areas where non-CO2 drivers such as freshwater and nutrient inputs impact acidification trends (Wallace et al., 2014; Kessouri et al., 2021). Hence the development of regional models with improved resolution and representation of coastal processes is essential.

2.3.3 Canadian OA trends in regional models

High resolution regional ocean biogeochemistry models require as inputs (1) high spatial resolution coastline and bathymetry; (2) high spatial and temporal resolution atmospheric forcing (e.g., wind speed and heat flux); (3) accurate open boundary forcing (e.g., temperature and nutrient concentration at the open-ocean boundaries of the regional model); and (4) freshwater discharge (volume, temperature, chemical composition). These model inputs are available to varying degrees, e.g., river chemistry is usually represented in very simplified fashion, and river discharge is poorly known in some regions. For projections, climate model simulations are used to define the change at the open boundaries (there are caveats about the accuracy with which climate models can represent relatively fine-scale features like the Gulf Stream, the California Undercurrent, or Labrador Sea convection).

Ocean scientists in Canada maintain a variety of regional models for hindcasts, predictions, and downscaling climate projections to regional scale (Han et al., 2022; Lavoie et al., 2025). They range in resolution from <1 km (Olson et al., 2020) to 1/4°; global ocean models, by contrast, usually have a resolution of 1-2°. Some regional models have published physical ocean results and are currently implementing biogeochemistry; these represent infrastructure being developed to address OA questions. For a limited number of regions, high-resolution regional models with biogeochemistry exist (e.g., Peña et al., 2019; Mortenson et al., 2020; Olson et al., 2020; Holdsworth et al., 2021; Lavoie et al., 2021). Recently, a moderate resolution model with a Canada-wide domain has been introduced (Christian et al., 2026), which can potentially provide consistent boundary conditions to a broad range of more localized domains. Here, we outline the current status of regional modelling projects that have published results including carbon chemistry.

The Canadian Pacific coast, from the Salish Sea to the Gulf of Alaska, is covered by models (Table 1). These have horizontal grid spacing ranging from 500 m (SalishSeaCast) to 4.5 km, with biogeochemical models ranging from medium to high complexity. Two models span the entire BC coast and have published climate projections (Holdsworth et al., 2021) as well as hindcasts (Peña et al., 2019); other experiments are in progress. Biogeochemical hindcasts are available for the Salish Sea (Olson et al., 2020; Jarníková et al., 2022). Biogeochemical hindcasts, forecasts and projections are also available for the Salish Sea region from US-developed models: LiveOcean Model (hindcasts and forecasts; Siedlecki et al., 2015) and Salish Sea Model (hindcasts and projections; Khangaonkar et al., 2019). Hindcast simulations of the Gulf of Alaska are available from US-developed models (Pilcher et al., 2018; Hauri et al., 2020).

Table 1

| Region | Model | System | Area covered | Horizontal resolution | nz | Experiments | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific | BCCM | ROMS | BC coast | 3 km | 42 | hindcast, projection* | a |

| NEP36-CanOE | NEMO | BC coast | 1/36° | 50 | hindcast*, projection | e | |

| SalishSeaCast/SMELT | NEMO | Salish Sea (partial) | 500 m | 40 | hindcast, forecast | g | |

| Arctic | CanOE-CSIB | NEMO | Arctic Ocean | 11–15 km | 46 | hindcast, projection* | h |

| ANHA4-BLING | NEMO | Northern Baffin Bay | ~10 km | 50 | hindcast, projection | i | |

| Atlantic | CANOPA/GBSM | NEMO | Scotian Shelf, GSL, GOM | 1/12° | 46 | hindcast, projection | j |

| ACM | ROMS | GOM to Labrador | 1/10° | 30 | hindcast, projection | k | |

| All | CanTODS | NEMO | North Pacific (44°N) to North Atlantic (26°N) | 1/4° | 75 | hindcast | l |

List of models that have conducted simulations including OA variables in Canadian coastal waters.

All of these are based on one of the available modelling systems, FVCOM, NEMO, or ROMS. NA, North America; GOM, Gulf of Maine; GSL, Gulf of St. Lawrence. nz signifies the number of model vertical levels. Hindcast, forecast, and projection are defined in the text. *indicates experiment is not yet published. References: a) Peña et al., 2019; e) Holdsworth et al., 2021; f) Khangaonkar et al., 2019; g) Olson et al., 2020; Jarníková et al., 2022; h) Hayashida et al., 2019; Mortenson et al., 2020; i) Buchart et al., 2022; j) Lavoie et al., 2021; k) Brennan et al., 2016; Laurent et al., 2021; Rutherford et al., 2021; l) Christian et al., 2026. Note that models developed by the US that cover Canadian waters (references b, c, d) are found in Supplementary Table S3.

For the Canadian Arctic, the model described in Mortenson et al. (2020) encompasses the entire Arctic Ocean with grid spacing of 11–15 km. It uses a medium complexity biogeochemical model and sea-ice biogeochemistry (CanOE-CSIB; Hayashida et al., 2019); a hindcast for 1980–2015 has been published, projection publications are in preparation. The Arctic and Northern Hemisphere Atlantic (ANHA4) model (Buchart et al., 2022) has performed both hindcasts (1981-2005) and projections (2006-2070) for the Canadian Arctic; for example, Butchart et al. (2022) describe application of this model to Northern Baffin Bay, using a resolution of ~10 km and a simple biogeochemical model (BLING; Galbraith et al., 2010). The recently developed Canada-wide (CanTODS) model of Christian et al. (2026) includes the entire Arctic Ocean as well as the Bering Sea and the subarctic Atlantic at 1/4°.

For Atlantic Canada, there are two models published. The CANOPA model described in Lavoie et al. (2021) encompasses the Gulf of Maine, Scotian Shelf and Gulf of St. Lawrence. This model has 1/12° resolution and is coupled to a medium complexity biogeochemical model. The Atlantic Canada Model (ACM; Laurent et al., 2021; Rutherford et al., 2021) stretches from the Gulf of Maine to the East Newfoundland Shelf. It has 1/10° resolution and is coupled to a medium complexity biogeochemical model. Both models have performed hindcasts (2005–2018 for CANOPA and 1999–2016 for ACM); the ACM has published projections for 2065-2080 (Rutherford et al., 2021; Lotze et al., 2022).

Overall, all of the coastal regions of Canada are covered by regional models to some degree, but most only by moderate-resolution (1/12° - 1/4°) basin-scale models. For example, a 1/12° North Atlantic model covers most of Canada’s east coast, but this resolution is not really adequate for nearshore regions. High-resolution coastal models are, however, being developed for some areas. For example, high-resolution (10 m - 1 km grid spacing) biogeochemical models exist for BC fjords, but have not yet published carbon chemistry results (DFO, 2022; Han et al., 2022).

From existing regional model results, some trends for Canada’s coasts can be presented. For example, projections presented by Holdsworth et al. (2021) for the BC continental shelf show that on average the saturation horizon is expected to shoal by ~100 m by 2055. This study found that hotspots of change in aragonite saturation in both RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 (Representative concentration pathways, RCPs, applied in CMIP5) were nearshore areas along the west coast of Vancouver Island and shallow areas along the north coast of BC. The Salish Sea Model projects annual mean reduction in pH of 0.18 by 2095 in the Salish Sea compared to 0.36 at the model boundaries; slower acidification in the Salish Sea was attributed to biogeochemical activity and circulation (Khangaonkar et al., 2019). Mortenson et al. (2020) found declines in annual-mean sea-surface pH from 8.1 to 8.0 and aragonite saturation from >1.2 to <1.1 from 1980 to 2015 in the Arctic Ocean north of 66.5°N and highlighted increased seasonal variations when the sea ice carbon pump is included. In Atlantic Canada, the CANOPA model shows low pH throughout the Laurentian Channel and aragonite undersaturation in bottom waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in its 2005–2018 hindcast. In the ACM, the Grand Banks are the main hotspot of bottom water acidification by mid-century; smaller declines in bottom water pH are found in the Gulf of Maine and on the southwestern Scotian Shelf (Rutherford et al., 2021; Lotze et al., 2022).

2.4 Biological responses

2.4.1 Overview

Globally, shelled organisms that use calcium carbonate (CaCO3) are expected to be most directly impacted by OA across all life stages, with resultant impacts on marine biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, food provisioning, and marine industry economic stability (Kroeker et al., 2013; Wittmann and Pörtner, 2013; Barton et al., 2015; Ekstrom et al., 2015; Falkenberg et al., 2018; Doney et al., 2020). For Canada, this includes commercially valuable shellfish species, valued at over $3.7 billion in 2023 (DFO, 2024a, c). Corrosive water conditions along the west coast of North America have already negatively impacted Pacific oyster aquaculture production in the last 10–15 years (Barton et al., 2015), with regional financial losses of $110 million USD (Ekstrom et al., 2015). Atlantic Canada’s reliance on aquaculture and fisheries makes it socio-economically vulnerable to OA (Wilson et al., 2020). Food-web foundational species, such as zooplankton and pteropods (Bednaršek et al., 2012, 2014, 2019; McLaskey et al., 2016, 2019), will also be negatively impacted by OA, particularly in Arctic regions which experience accelerated change (Comeau et al., 2009, 2012; Niemi et al., 2021).

OA may cause other impacts on organisms, such as reduced survival and reproductive output (Ross et al., 2011; Haigh et al., 2015), metabolic or genomic changes (Noisette et al., 2021; Wright-LaGreca et al., 2022; Frommel et al., 2025), and altered behaviour (Jellison et al., 2016; Melzner et al., 2020). OA may also facilitate carbon fixation by photosynthesizers, although studies to date show a range of responses (Mackey et al., 2015; Hoppe et al., 2017, 2018a, b), and OA may increase harmful algal blooms (HABs) (Hattenrath-Lehmann et al., 2015; Riebesell et al., 2018; Griffith and Gobler, 2020). Species responses may differ regionally (Calosi et al., 2017; Vargas et al., 2017; Thor et al., 2018; Guscelli et al., 2023a, b, 2025; Feugere et al., 2025), due to regional exposure levels or multiple stressor combinations. Additive or synergistic effects of multiple drivers alongside OA may further narrow species environmental optima and/or tolerances (Kroeker et al., 2013, 2017; Baumann, 2019; Klymasz-Swartz et al., 2019; Lauchlan and Nagelkerken, 2020; Stevenson et al., 2020; Feugere et al., 2025).

2.4.2 Ongoing biological research efforts and organizational contributions

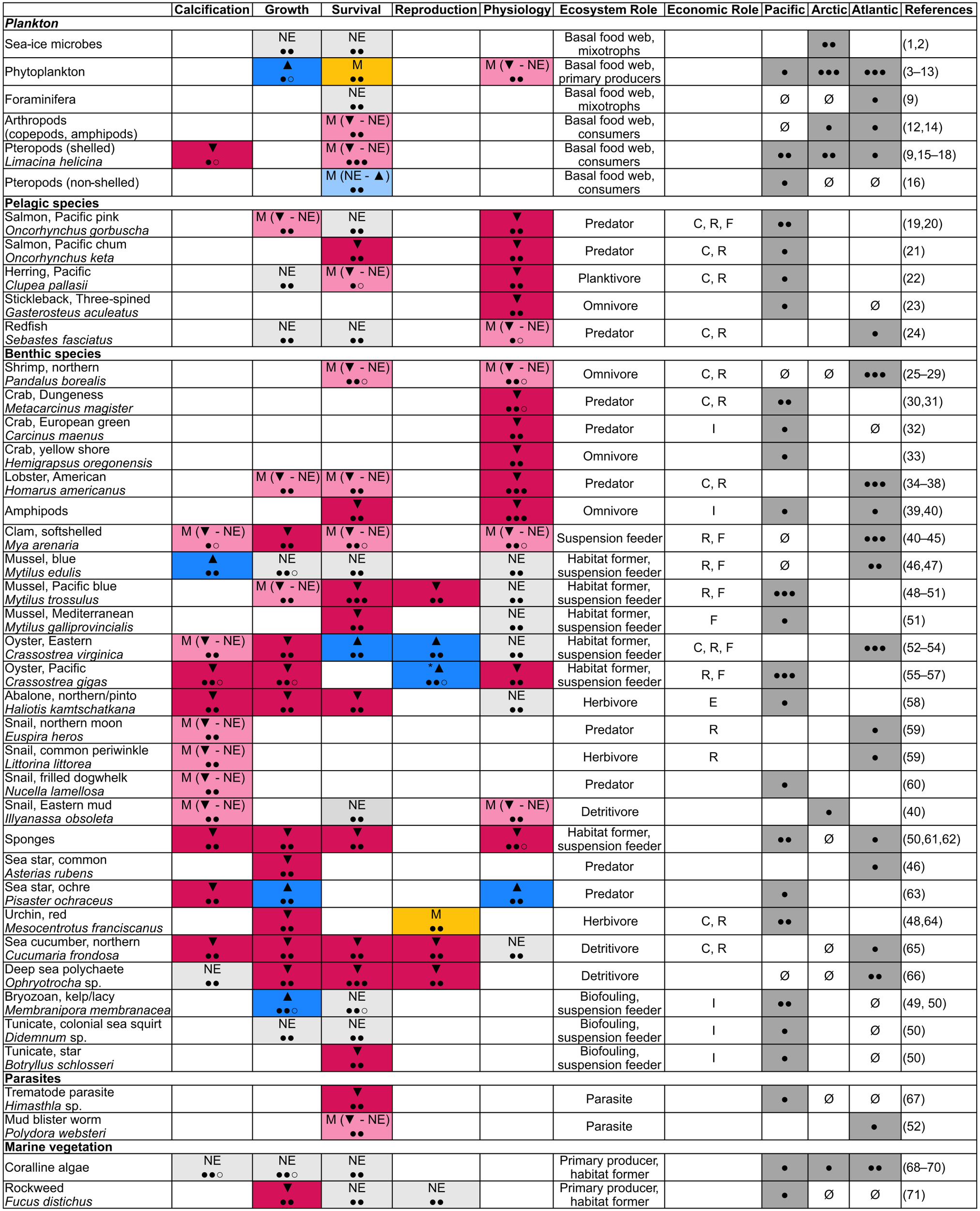

Biological studies of OA in Canada are being conducted by academic research groups primarily in Atlantic and Pacific universities (e.g., University of British Columbia, University of Victoria, Vancouver Island University, University of New Brunswick, Dalhousie University, University of Quebec at Rimouski), government (DFO) and non-profit groups (e.g., Hakai Institute), or in collaboration with each other and industry proponents. In general, biological research is conducted in multistressor laboratories or field mesocosms, ranging from lower trophic levels, marine vegetation, to shellfish, and commercial and subsistence fisheries species (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Table showing species responses to OA from studies conducted in Canada. Responses are: ▼ – negative, ▲ – positive, NE – no effect, M – mixed (positive, negative, no effect), M (▼ - NE) – mixed (negative - no effect), M (NE - ▲) – mixed (no effect -positive), *Selectively bred oysters showed increased resilience to OA. Confidence levels follow the style of IPCC WG II (IPCC, 2023) in terms of number of studies and are: ● – low, ●○ – medium low, ●● – medium, ●●○ – medium high, ●●● – high. Economic Role abbreviations: C – commercial fishery, R – recreational fishery, F – farmed/aquaculture, I – invasive species, E – endangered species. Ranges (Pacific, Arctic, Atlantic): ● – present, low evidence (1 study), ●● – present, medium evidence (2 studies), ●●● – present, high evidence (3+ studies), Ø – present, no data. References: 1 (Monier et al., 2014); 2 (Torstensson et al., 2021); 3 (Hattenrath-Lehmann et al., 2015); 4 (Mélançon et al., 2016); 5 (Hoppe et al., 2017); 6 (Hoppe et al., 2018a); 7 (Hoppe et al., 2018b); 8 (Hussherr et al., 2017); 9 (Maillet and Pepin, 2017); 10 (Bénard et al., 2018); 11 (Bénard et al., 2019); 12 (Murphy et al., 2020); 13 (Bénard et al., 2021); 14 (Lewis et al., 2013); 15 (Comeau et al., 2012); 16 (Mackas and Galbraith, 2012); 17 (Niemi et al., 2021); 18 (Miller et al., 2023); 19 (Ou et al., 2015); 20 (Frommel et al., 2020); 21 (Frommel et al., 2025); 22 (Frommel et al., 2022); 23 (Soor et al., 2024); 24 (Guitard et al., 2025); 25 (Chemel et al., 2020); 26 (Guscelli et al., 2023a); 27 (Guscelli et al., 2023b); 28 (Feugere et al., 2025); 29 (Guscelli et al., 2025); 30 (Hans et al., 2014); 31 (Durant et al., 2023); 32 (Fehsenfeld and Weihrauch, 2013); 33 (Khodikian et al., 2025); 34 (Keppel et al., 2012); 35 (Klymasz-Swartz et al., 2019); 36 (Menu-Courey et al., 2019); 37 (Noisette et al., 2021); 38 (Tai et al., 2021a); 39 (Lim and Harley, 2018); 40 (McGarrigle et al., 2023); 41 (Clements and Hunt, 2014); 42 (Clements and Hunt, 2018); 43 (Clements et al., 2016); 44 (Clements et al., 2017a); 45 (McGarrigle and Hunt, 2023); 46 (Keppel et al., 2015); 47 (Clements et al., 2018c); 48 (Sunday et al., 2011); 49 (Brown et al., 2016); 50 (Brown et al., 2020); 51 (Thyrring et al., 2023); 52 (Clements et al., 2017b); 53 (Clements et al., 2018b); 54 (Clements et al., 2021); 55 (Nordio et al., 2021); 56 (Wright-LaGreca et al., 2022); 57 (Zhong et al., 2024); 58 (Crim et al., 2011); 59 (Clements et al., 2018a); 60 (Nienhuis et al., 2010); 61 (Robertson et al., 2017); 62 (Stevenson et al., 2020); 63 (Gooding et al., 2009); 64 (Reuter et al., 2011); 65 (Verkaik et al., 2016); 66 (Verkaik et al., 2017); 67 (Franzova et al., 2019); 68 (Rahman and Halfar, 2014); 69 (Martone et al., 2021); 70 (Williams et al., 2021); 71 (Schiltroth et al., 2019). Paper metadata and full responses across all species and life stages (e.g., larval, juvenile, adult) with experimental/in situ and species response details can be found in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

2.4.3 Current trends in Canadian biological OA research

To examine biological responses to OA in Canada, we conducted a systematic review by searching Web of Science and Google Scholar databases using the search terms: “ocean acidification” AND Canada, as of January, 2026. Any study including an observed (either natural or experimental) organismal response to OA conducted in Canada and including at least one co-author affiliated with a Canadian institution were included. For studies that also examined other stressors (e.g., temperature), only responses to OA alone were included. Our meta-data analysis found 71 OA impact studies conducted on organisms in Canada, including 65 experimental studies and 7 observational and/or fisheries modelling studies (one included both experiments and observations) (Supplementary Table S4). Of the studies, 28 were conducted in the Pacific, nine were conducted in the Arctic, 33 were conducted in the Atlantic, and one included both Arctic and Atlantic sites (Williams et al., 2021) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S4). Similar to other countries, the majority of OA studies conducted on species in Canada have involved experiments on calcifying organisms, including socio-economically important shellfish species (bivalves and crustaceans) and lower trophic level planktonic organisms (Figure 4), and often examine at least one other climate stressor (e.g., ocean warming, hypoxia). There have been over 100 taxa studied in Canada, ranging from species to kingdom-level identifications (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5). Of the taxa studied, many had distributions spanning multiple regions (Figure 4).

2.4.4 Organismal trends in Canadian OA research

OA indicator species such as molluscs were the most commonly studied animals, particularly commercially relevant bivalves, and the pteropod Limacina helicina (Figure 4). The majority of mollusc species showed either negative or no response to OA, with studies mostly examining impacts to growth, survival and calcification (Figure 4). Interestingly, two aquaculturally important Atlantic taxa, the mussel Mytilus edulis and the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, showed more mixed responses in Canadian studies compared to elsewhere, including positive, negative, and/or no effects of OA (Keppel et al., 2015; Clements et al., 2017b, 2018b, c, 2021). These mixed responses are somewhat surprising given that many other studies of these species from other regions demonstrate more negative outcomes overall (Gazeau et al., 2010; Waldbusser et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2019; Downey-Wall et al., 2020). Another instance of unexpected positive responses in molluscs were the warmer-water adapted pteropods Clio pyramidata and Clione limacina, which showed increased abundances over several decades in the Pacific (Mackas and Galbraith, 2012). Ultimately, observed differences may be related to localized population adaptation, life-stage specific and regional exposure levels, and experimental conditions (e.g., differences in pH/pCO2 levels of both control and OA treatments), highlighting that there are many considerations when determining species vulnerabilities to OA.

Crustaceans were another well studied group; while most species displayed negative responses to OA, there were some mixed responses between life stages, with some species only showing OA impacts at one life stage (Figure 4). Lobsters were the most studied crustacean, and had mostly negative responses to OA, although one study found no significant effects on early larval development and survival but negative OA effects on later juvenile stages (Noisette et al., 2021). These crustacean studies highlight the need to assess OA across life stages in case of a vulnerability bottleneck. Many of the crustacean studies focused on physiological responses to OA, such as metabolic responses (Fehsenfeld and Weihrauch, 2013; Hans et al., 2014; Klymasz-Swartz et al., 2019; Menu-Courey et al., 2019; Noisette et al., 2021; Durant et al., 2023).

OA studies conducted on other animals in Canada included sponges, annelids, cnidarians, tunicates, bryozoans, echinoderms, fish, and trematode parasites. Again, the majority of taxa showed negative responses to OA, although a few were not impacted (Figure 4). Invasive species, such as bryozoans and tunicates, tended to show more resilience to OA than native species, highlighting potential outcompeting of more vulnerable native benthic species by more resilient invasive taxa (Brown et al., 2016, 2020). One study also demonstrated mixed responses in the Pacific seastar, Pisaster ochraceus, where OA negatively impacted calcification, but positively impacted overall growth and physiology (non-significant increase in feeding rates) (Gooding et al., 2009).

Plankton, microbes, and macroalgae were generally more resilient to OA than animals. Sea-ice microbes mostly showed no responses to OA, whereas phytoplankton responses were more mixed in terms of abundance and physiology, with many showing only minimal responses to OA (Figure 4). Even within the same genus or species of phytoplankton, there were varying responses. For example, Chaetoceros species showed either negative or no effects depending on the study (Hoppe et al., 2017, 2018a; Hussherr et al., 2017). Although the calcifying coralline algae species examined (including species from all three Canadian oceans) showed resilience to OA in their skeletal structure and growth (Figure 4), ongoing mesocosm studies suggest that some coralline species are sensitive to OA, showing reduced calcification and growth (unpublished data). These contrasting results highlight nuanced, species-specific responses to OA that warrant further study.

2.4.5 Regional trends in Canadian OA biological studies

Pacific studies mostly focused on commercially valuable organisms, as well as habitat formers (sponges and mussels), ecologically important consumers (e.g. echinoderms), and fouling communities. Overwhelmingly, OA had negative impacts on most Pacific taxa, again with phytoplankton showing more resilience than animal taxa. There was also one study that examined oyster spat microbiomes, which showed no effects from OA (Zhong et al., 2024) (Figure 4). While the overall responses of Pacific oysters to OA are negative, and the oyster industry has already felt the impacts of OA (Barton et al., 2015; Ekstrom et al., 2015), two recent studies conducted in Canada examined how selective breeding may confer resiliency to OA (Nordio et al., 2021; Wright-LaGreca et al., 2022). The Pacific region also included more studies of fish than other regions (Pacific salmon, herring, three-spined sticklebacks) (Ou et al., 2015; Frommel et al., 2020, 2022, 2025; Soor et al., 2024), with only one fish study conducted outside the Pacific region (Guitard et al., 2025).

Arctic studies mostly focused on phytoplankton, zooplankton (copepods and pteropods), and coralline algae. Photosynthetic taxa generally showed resilience to OA, while zooplankton responded more negatively to OA (Figure 4). Changes in biogeochemistry and temperature associated with rapid oceanic change in the Arctic are expected to drive organisms past their sensitivity thresholds faster than other regions (Robbins et al., 2013; Azetsu-Scott, 2018; Bush and Lemmen, 2019; Woosley and Millero, 2020). However, some authors suggest that Arctic microbes and phytoplankton communities may be more tolerant of acidic conditions given their regular exposure to more extreme changes in the carbonate system associated with the formation of sea-ice (Monier et al., 2014; Torstensson et al., 2021).

Atlantic studies also focused mostly on commercially relevant taxa, including crustaceans, bivalves, and one fish study, as well as plankton and benthic species. While Atlantic bivalves, including mussels and oysters, appeared generally more resistant to OA than their Pacific counterparts (Figure 4), Atlantic studies often had more targeted hypotheses that limited their scope. For example, the positive calcification responses in M. edulis resulted in a change to the shell to body-size ratio (Keppel et al., 2015), which would negatively impact their value. Furthermore, many OA studies of Atlantic US bivalves still indicate there will be negative impacts to many northwest Atlantic bivalve fisheries under future OA scenarios, indicating that further research is required to establish vulnerabilities of Atlantic Canadian taxa (Rheuban et al., 2018; Stevens and Gobler, 2018; Pousse et al., 2022). Commercially important crustaceans including lobster and shrimp were also mostly negatively impacted by OA, with regional populations of shrimps varying in the severity of their responses (Guscelli et al., 2023a, b, 2025; Feugere et al., 2025). However, the palatability (taste) of shrimp was unaffected by OA, suggesting that OA impacts to the value of the fishery will be restricted to organismal responses to OA (Chemel et al., 2020).

2.4.6 Emerging trends and knowledge gaps in Canadian biological OA research

General patterns of biological studies of OA in Canada track global trends, with calcifying organisms showing the greatest sensitivity to OA, and photosynthetic organisms showing more resilience (Figure 4), with a focus on calcifying organisms, lower trophic levels, and commercially exploited species. High regional vulnerabilities of taxa from laboratory experiments do not generally account for any transgenerational adaptation potential (Diaz et al., 2018; Spencer et al., 2020; Gibbs et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Parker et al., 2021) nor consider within-species local adaptive responses across geographical gradients (e.g., Guscelli et al., 2023a, b). Such studies are needed for comprehensive vulnerability assessments and levels of risk to be estimated. Adult life-stages are also the most studied in Canada, while juvenile stages are the least studied. This challenge also exists globally, as there are generally fewer studies of OA impacts on juvenile and early life stages, despite their importance to overall population stability (Gosselin and Qian, 1997), and despite growing evidence that for some species, early life stages are disproportionately vulnerable to OA (Przeslawski et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2022). Few studies conducted in Canada focus on more than one life stage and for most organisms, only one part of the life-cycle has been researched (Supplementary Table S5). However, for several of the arthropod taxa, there are varying responses between stages (with one stage usually being more resilient than others) (Supplementary Table S5). Again, this highlights the need for full assessments of OA impacts across life cycles, as even one negatively affected stage may affect population productivity and stability over the long-term. Of the invasive species studied, many show resilience to OA, indicating potentially negative ecosystem outcomes. Taken together, the results of OA studies conducted on organisms in Canada highlight the need for ongoing OA research and integration into multistressor studies, and indicate several key areas (transgenerational adaptation potential, multi life-stage studies, regional/population adaptations), and many species that require additional study.

2.5 Socioeconomic and sociocultural perspectives

Canada’s three oceans are important sources of revenue, employment, recreation and cultural connectivity. Canada’s commercial fisheries were valued at $3.6 billion in 2023, of which $3.1 billion is from shellfish species, with lobster and crab being the predominant economic contributors (DFO, 2024c). Canada’s aquaculture industry had a total value of $1.2 billion in 2023, including $127 million from shellfish species particularly vulnerable to OA, such as oysters, mussels and clams (DFO, 2024a). Combined seafood production (fishing, aquaculture and fish processing) employed 64, 911 people in Canada in 2023, predominantly in rural areas where economic opportunities are less diversified, with a total processing value of $7 billion (DFO, 2024b). Further, the economic value of the sector extends beyond the landed and processing value of fish caught, to include indirect (demand for input purchases needed to support the output from the sector) and induced impacts (from personal income spending generated from direct and indirect impacts) to Canada’s marine economy (DFO, 2024b). OA is currently having negative impacts on Canadian seafood species (see Biological responses section), with projected knock-on effects for socioeconomically and subsistence fishery important species for Atlantic (Wilson et al., 2020; Tai et al., 2021a), Pacific (Haigh et al., 2015; Talloni-Álvarez et al., 2019) and Arctic (Steiner et al., 2019; Tai et al., 2019) regions of Canada.

There are also negative consequences of OA for human food safety from bioaccumulations of pollutants (Costa et al., 2020a, b; Dionísio et al., 2020; Falkenberg et al., 2020) or increased susceptibility to pathogens of concern for humans (Schwaner et al., 2020; Byers, 2021; Ferchichi et al., 2021). Seafood economies alone, however, do not account for the full suite of vulnerabilities posed by climate change to marine resources, which also include impacts on subsistence food security, social and cultural rights, practices and traditions (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2016; Weatherdon et al., 2016; Falkenberg et al., 2020; Whitney et al., 2020; Batal et al., 2021). Like all aspects of climate change, OA will have disproportionate impacts on some frontline and Indigenous communities, whether due to geographic location or specific reliance on (or connection to) species and ecosystems that are most threatened. In some instances, Indigenous communities are co-managers and stewards of marine species, and forward-thinking provinces are already considering the impact of climate change on coastal waters, economies, and Indigenous communities. While there are some exceptions, integration of climate change risks, vulnerabilities and response into mainstream fisheries and aquaculture assessments in Canada is not commonplace (Pepin et al., 2022). Studies integrating socio-economic and socio-cultural indices related to climate-ocean change are rare (Teh et al., 2020; Delgado-Ramírez et al., 2023), which is hindering more holistic local adaptation planning for national economies and coastal communities.

2.6 Policy perspectives

While there is growing recognition of climate related ocean changes like warming, acidification and deoxygenation at the international level, these changes are often under-recognized by policy and decision-makers, or are misunderstood or not incorporated across domestic climate mitigation or adaptation priorities (Harrould-Kolieb and Herr, 2012; Because the Ocean Initiative, 2019; Turley et al., 2021). In addition, there are limited Canadian policies and regulations currently available to address rapidly emerging marine geoengineering activities relevant to OA. For example, ocean fertilization and OAE activities might be subject to various international agreements (VanderZwaag et al., 2023a; Webb et al., 2023) with some small-scale research efforts underway in Canada falling outside the ocean disposal provisions under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) (S.C., 1999, c. 33) in light of the land-based nature of releases (VanderZwaag and Mahamah, 2024). This section provides an overview of existing international and national climate or ocean policy frameworks that have relevance for driving improved OA mitigation, adaptation and resilience measures.

2.6.1 International laws and policies

A fragmented array of international laws and policies relevant to OA has emerged (Steiner and VanderZwaag, 2021; VanderZwaag et al., 2021). Various state responsibilities and commitments have emerged with the Paris Agreement, expanding upon the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and setting the overarching agenda for advancing mitigation and adaptation responses to OA (Engler et al., 2019; Harrould-Kolieb, 2021). Parties to the Paris Agreement of the UNFCCC are expected to have increasingly ambitious climate action over time (Winkler et al., 2017; Kuh, 2021), including greenhouse gas emissions reductions, national adaptation planning, and communication (Perez and Kallhauge, 2017). Although not focused solely on OA, UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 includes Target 14.3, which calls for minimizing and addressing the impacts of OA through enhanced scientific cooperation and standardized global monitoring and reporting (Scott, 2020). The 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework makes specific OA provisions under Target 8: minimizing the impact of climate change and OA on biodiversity; increasing biodiversity resilience through mitigation, adaptation and disaster reduction actions; and utilizing nature-based solutions and ecosystem-based approaches (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has various provisions applicable to OA (Craig, 2022; Popattanachai and Kirk, 2021; Scott, 2021). They include the obligations of States to protect and preserve the marine environment (Art. 192), to take necessary measures to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species (Art. 194(5) and to take necessary measures to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment (Art. 194 (1). The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in its May 2024 Advisory Opinion on Climate Change and International Law highlighted the strict due diligence obligation of States to control greenhouse gas emissions pursuant to Article 194(1) with scientific understanding of climate change and OA impacts being a key factor in determining the due diligence required (ITLOS, 2024, para. 207). The Tribunal also added that a precautionary approach in regulating marine pollution from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions is required in the absence of scientific certainty in light of the serious and irreversible damage that may be caused to the marine environment (ITLOS, 2024, para. 213).

OA also threatens the full enjoyment of various human rights set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations General Assembly, 1948) and other human rights treaties (UNEP, 2015; Engler et al., 2025). Key human rights include the right to food security (Elver and Oral, 2021), life, health, culture, natural resources for Indigenous peoples and the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment (Human Rights Council, 2025).

The Ocean and Climate Change Dialogue first held in December 2020 and annually since 2022 under the auspices of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice continues to be a forum for addressing OA related policies (UNFCCC, n.d). A common discussion point has been the need to protect blue carbon ecosystems, such as mangroves, seagrasses, salt marshes and kelp beds, as a means to mitigate and adapt to climate change and OA. The 2023 dialogue, co-chaired by Canada and Chile, focused specifically on coastal ecosystem restoration, blue carbon, fisheries, and food security (UNFCCC, 2023).

2.6.2 National policies

While Canada submitted its nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement in 2021, there was no specific mention of OA and little attention to the ocean (Government of Canada, 2021). Key climate mitigation commitments included: reducing emissions by 40-45% below 2005 levels by 2030; reaching net-zero emissions by 2050; and placing a price on carbon pollution (Government of Canada, 2021). The only specific mention of oceans was a commitment by Canada to protect 25% of the oceans in Canada by 2025 and looking towards 30% by 2030, which was viewed as having both mitigation and adaptation co-benefits (Government of Canada, 2021, 13-14). General ocean conservation targets were reaffirmed in Canada’s Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2022-2026 (Government of Canada, 2022), including 10 new national marine conservation areas by 2026 (Government of Canada, 2022, 166). The 2023 National Adaptation Strategy (Government of Canada, 2023) and accompanying Adaptation Action Plan (Government of Canada, 2024) again affirmed the previous conservation commitments, and suggested modernization of the Oceans Act (S.C., 1996, c. 31) to enable climate-resilient conservation planning. This Action Plan also pledged to set an indicator for status of key fish stocks affected by changing temperatures and chemistry in Canada’s oceans (Government of Canada, 2023, Appendix D). The amendment of the Fisheries Act in 2019 (S.C., 2019, c. 14) includes provisions allowing for ecosystem considerations (which could include climate change and OA) to be factored into resource management. In 2023 the 8th Standing Committee report on Fisheries and Oceans, (McDonald, 2023) highlighted a number of key recommendations for action related to climate change in Canadian aquatic ecosystems; while OA was not explicitly mentioned, it was included as a climate change stressor. Some recommendations from this Committee included determining climate vulnerabilities, and developing ecosystem-based management approaches to increase resiliency to support coastal communities.

2.6.3 International and national policies relating to marine carbon dioxide removal

Whilst this paper focuses on OA, it is acknowledged that ocean climate mitigation activities such as mCDR are being conducted in Canadian oceans, including ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) and ocean nutrient fertilization (ONF). While various environment-related laws would likely apply to these and other proposed marine geoengineering projects having ocean acidification implications (VanderZwaag et al., 2023a), there are legal limitations. Canada has yet to ratify the 2013 London Protocol amendment addressing ONF in particular (where legitimate scientific research was mentioned, but not defined) and implementation of the restrictions have not yet been enacted under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) (S.C., 1999, c. 33). Commercial operations in Atlantic Canada have been undertaking OAE activities from land-based releases, which have fallen outside the ocean disposal provisions under CEPA in light of the land-based nature of releases (VanderZwaag and Mahamah, 2024). In general, there are policy and governance uncertainties that may limit mCDR operations without further policy development (Steenkamp and Webb, 2023; VanderZwaag and Mahamah, 2024; Engler et al., 2025).

2.7 Examples of provincial and indigenous OA actions in Canada

OA has received little specific attention in climate change planning efforts by the Atlantic provinces and northern regions. The climate change action planning documents for New Brunswick (Province of New Brunswick, 2022), Newfoundland and Labrador (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2025a, b) and Prince Edward Island (Government of Prince Edward Island, 2022a, b) do not specifically mention OA and only provide for general climate mitigation and adaptation actions. While Nova Scotia’s climate action plan, published on December 2022, explicitly recognizes OA as a threat to fisheries and productivity of ocean waters (Province of Nova Scotia, 2022, 11), the plan does not pledge any actions specific to OA, but rather promises various general mitigation and adaptation efforts (Province of Nova Scotia, 2022, 13). National and regional Inuit climate change strategies exist and highlight mitigation, adaptation and knowledge mobilization actions including collaboration with researchers, but do not mention OA specifically (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2019; Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, 2021).

On the Pacific Coast, BC sits on the Pacific Coast Collaborative (PCC) Ocean Acidification Work Group (including representation from Washington, Oregon, and California), which co-founded the International Alliance to Combat Ocean Acidification (OA Alliance). The OA Alliance engages national and subnational governments on the process and substance for creating an OA Action Plan. OA Action Plans allow governments to commit to ambitions for mitigating OA and actively address localized manifestations of OA. The BC Preliminary Climate Risk Assessment released in 2019 identified OA as an immediate high-risk threat and recommended further evaluation of its impacts (Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, 2019). In response, the 2023 BC OAH Action Plan (British Columbia Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Action Plan Advisory Committee, 2023) was developed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food, at the request of the Climate Action Secretariat of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy. This Action Plan was developed to increase collaboration, understanding, and response to OAH in BC’s coastal waters with an emphasis on supporting resilience of keystone fisheries and aquaculture. Five goals of the Action Plan included: 1) build and strengthen collaborations related to OAH science and engagement; 2) increase awareness and understanding of OAH; 3) advance scientific understanding of OAH; 4) evaluate interactions between marine carbon dioxide removal approaches and OAH, and; 5) enhance mitigation, adaptation and resilience to OAH. The OAH Plan was also an endorsed UN Ocean Decade Project under the Ocean Acidification Research for Sustainability Programme5. This Plan was rapidly followed in 2023 by the Climate Ready BC Seafood Program, with $1.7 million from the Province that funded 11 mainly community-led projects helping to address the Action Plan goals. This Action Plan is being used to inform broader coastal climate change adaptation planning. For example, it forms a key component of the province of BC’s Coastal Marine Strategy including the implementation of actions identified in the plan, such as using marine vegetation as an “OA mitigation tactic” (Province of British Columbia, 2024). Further, the OAH Action Plan and associated Climate Ready BC Seafood Program are being reported out in BC’s annual Climate Change Accountability Report, effectively mainstreaming OA awareness and action as a key component of BC climate strategy (Province of British Columbia, 2024).

The Tsleil-Waututh (TWN) First Nation and City of Vancouver have also outlined key research projects and priorities related to mitigating and adapting to OA impacts along their coastlines, and within their respective programs or mandates. For example, the TWN is leading the Cumulative Effects Monitoring Initiative (CEMI), a holistic monitoring program to establish current baseline conditions, monitor and assess trends, and evaluate climate change effects to traditional food species and key habitats throughout Vancouver, BC’s Burrard Inlet, including a study investigating the potential of shell hash to mitigate acidification in intertidal sediments (Doyle and Bendell, 2022). In addition, the TWN registered a voluntary commitment to implement UN SDG 14.3 “to minimize and address OA’’ as part of the UN Ocean Conference in 2022. The City of Vancouver, in addition to setting ambitious carbon emission reduction targets, is leveraging their Rain City Strategy to reduce run-off from road and urban surface through green infrastructure. Further, the BC First Nations Climate Strategy and Action Plan recognizes “rising sea-levels, ocean warming and OA’’ as climate impacts that affect First Nations and their communities, one that amplifies the impacts from colonialism individually in intergenerationally and affects Title, Rights, and Treaty Rights (First Nations Leadership Council, 2022).

3 Discussion

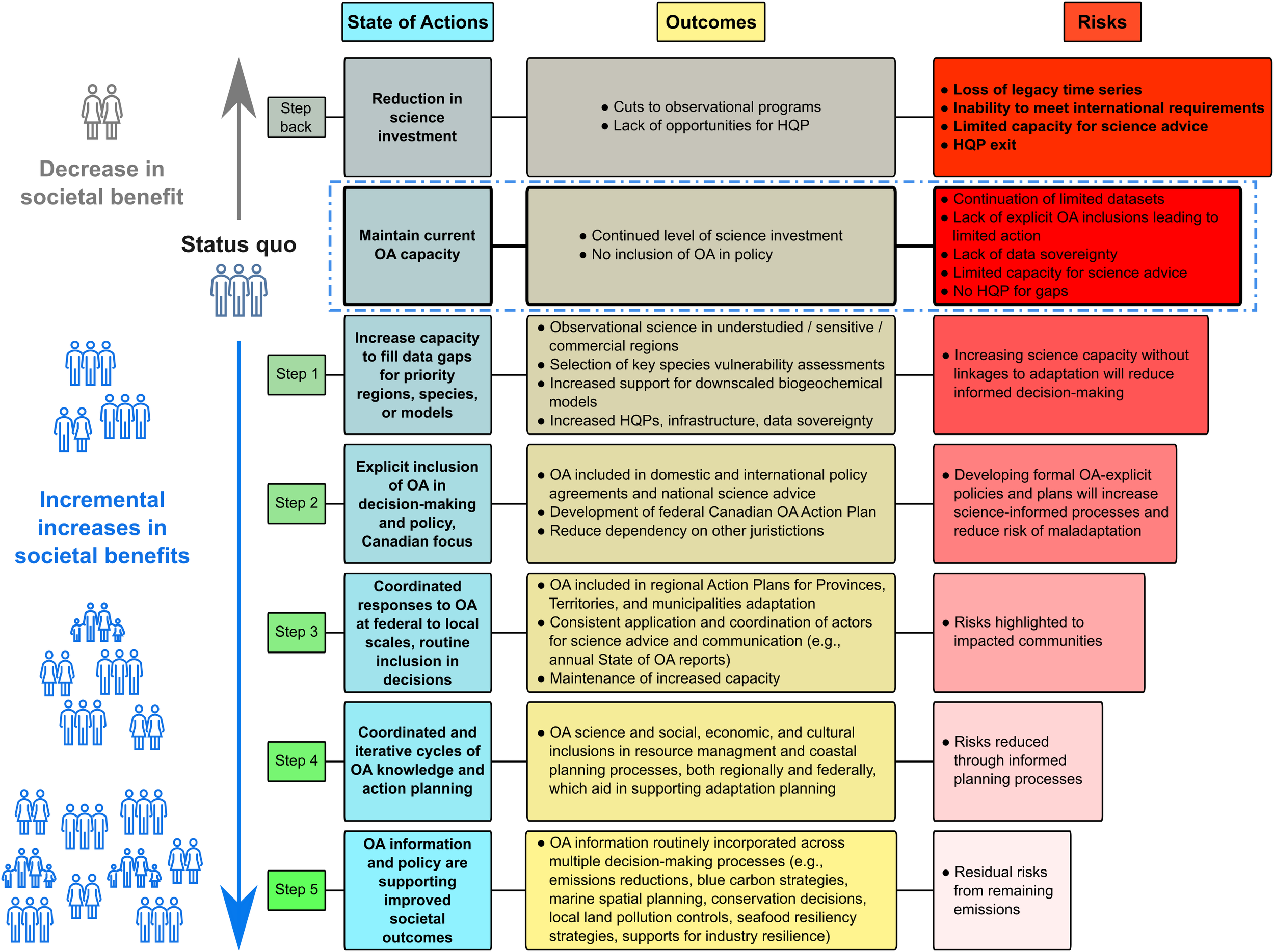

3.1 Recommendations and pathways for OA action in Canada