Abstract

The expansion of marine economic activities and the increasing demand for maritime security have positioned drone-based aerial object detection as a crucial technology for applications such as marine environmental monitoring and maritime law enforcement. However, maritime aerial imagery remains highly challenging due extreme illumination variations, the small size and indistinct appearance of targets. This paper introduces a novel dual-domain contrastive learning framework integrated with low-light degradation enhancement to address these challenges. First, a low-light degradation perception module performs illumination equalization, improving image uniformity under adverse lighting conditions. Then, a dual-domain contrastive learning strategy aligns representations across both image and feature domains, enabling the detection network to learn more discriminative features. Additionally, a Local Feature Embedding and Global Feature Extraction Module (LEGM) is incorporated into the detection network to enhance the representation of small-scale maritime targets. Experiments on SeaDronessee and AFO datasets demonstrate the superiority of the proposed approach, achieving an improvement of 4.3% in mAP@0.5 and 1.9% in mAP@0.5:0.95 on SeaDronesSee, 1.9% in mAP@0.5 and 1.1% in mAP@0.5:0.95 on AFO. These results confirm that the proposed method delivers robust and accurate maritime object detection under complex environmental conditions and has strong potential for deployment in real-world maritime surveillance applications.

1 Introduction

As a nation encompassing both continental and maritime territories, civilization has been molded by millennia of interactions and integration among maritime, agrarian, and nomadic cultures. These cultures have mutually complemented one another, thereby forming the bedrock of Chinese civilization. Currently, the proposition and implementation of concepts such as the construction of a maritime power, the joint promotion of the Belt and Road Initiative (Wang and Liang, 2024), and the forging of a community with a shared future for mankind have presented maritime civilization with a significant historical opportunity for development. However, maritime development entails both opportunities and challenges. Globally, illegal fishing results in annual losses amounting to $23 billion. Oil spills wreak havoc on 54,000 km² of marine ecosystems. Pirate attacks in regions like the Gulf of Aden are escalating at a rate of 17% per annum. Traditional manual patrols are plagued by extensive blind spots and delayed response times. Consequently, there is an urgent need for an intelligent maritime object monitoring system to tackle these issues.

As a versatile automated platform, unmanned aerial vehicles have incrementally evolved into indispensable instruments for maritime surveillance, owing to their extensive coverage and cost-effectiveness. In comparison to conventional satellite remote sensing and vessel-based patrols, UAVs are capable of carrying high-precision sensors and imaging apparatuses, such as high-resolution cameras and LiDAR, to undertake long-duration, large-scale missions. The sea-surface imagery acquired by UAVs offers shore-based personnel substantial data support, thereby augmenting their responsiveness to maritime emergencies.

However, aerial maritime imagery frequently encounters degraded quality and formidable detection challenges, attributed to sea-surface reflections, diminutive targets, and multi-scale variations. Although detection methods predicated on deep learning have emerged as the prevailing techniques with the progress of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the direct application of generic detection methods to UAV aerial maritime targets generally leads to a substantial decline in accuracy, encompassing severe omissions and false detection. Consequently, achieving precise detection in maritime images captured by UAV still represents a significant research direction within the field of object detection.

Current object detection algorithms driven by deep learning1, continue to evolve to balance accuracy and efficiency while advancing in multi-modality, lightweight design, and robustness. The field broadly classifies object detection frameworks into two-stage and single-stage architectures. Two-stage models, which are a dominant paradigm in object detection, operate by dividing the detection process into region proposal generation followed by object classification and localization. Evolutionary milestones include R-CNN (Yasir et al., 2024), followed by Fast R-CNN (Girshick, 2015), culminating in Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2016). Due to their reliance on pre-generated region proposals, these methods demand higher computational resources and exhibit slower detection speeds, making them unsuitable for maritime detection scenarios with limited computing resources and stringent real-time requirements. Single-stage models, such as the YOLO series (Redmon et al., 2016), SSD (Yang et al., 2024), and RetinaNet (Lin et al., 2017), adopt an end-to-end approach that directly predicts object locations and categories in a single forward pass. This streamlined process delivers faster inference and higher accuracy, rendering these algorithms ideal for real-time maritime detection. To address challenges in maritime target detection, researchers have proposed several solutions, which we categorize into the following three directions: 1.Lightweight Network Design Direction: For instance, Yue et al. (2021) integrated MobileNet v2 with YOLOv4 to develop a lightweight maritime detection network. Their approach employed sparse training on Batch Normalization scaling factors and channel pruning to eliminate redundant parameters. 2. Multi-scale Feature Direction: Hu et al. (2022) introduced a multi-scale anchor-free detection method using a Balanced Attention Network, enhancing detection of multi-scale maritime targets and nearshore vessels, though model generalization requires further improvement. Wang et al. (2023) proposed a multi-scale feature fusion network for SAR ship detection, which leverages contextual details to improve contour recognition and detection precision. 3.Attention Mechanism Enhancement Direction: Ma et al (Ma et al., 2024)designed a bidirectional coordinate attention mechanism to help networks focus on ship features while suppressing background noise. They further incorporated multi-resolution feature fusion to mitigate spatial information loss in small-scale vessels.

Although the aforementioned methods have targeted improvements for maritime object detection, detecting small maritime targets remains more challenging compared to standard-sized objects. Scholars generally identify small targets through relative scale or absolute scale criteria (Cheng et al., 2023): Relative scale defines small targets as those occupying less than 0.12% of the total image pixels. Absolute scale classifies targets with resolutions below 32×32 pixels as small targets (Lin et al., 2014).

The key challenges that impede the performance of small-target detection encompass the following aspects:

-

The scarcity of effective information resulting from low resolution;

-

Minimal pixel occupancy, which is further exacerbated by image quality degradation;

-

Interference stemming from complex environments (Liu et al., 2023) and the absence of contextual validation cues (Liu et al., 2022);

-

The prevalent problems of mutual occlusion (Zheng et al., 2022) and dense distribution (Zhang et al., 2021).

To address these challenges, prior studies have integrated contrastive learning with detection networks: Wang et al. (2021) aligned visual features by leveraging similar query text fragments from different videos within the same training batch. By mining co-occurring visually similar segments and integrating Noise Contrastive Estimation (NCE) loss, they learned discriminative features to mitigate the visual-textual semantic gap. Hsu et al. (2020) proposed a progressive adaptation method that employs an intermediate domain to bridge domain gaps, decomposing a challenging task into two simpler subtasks with reduced discrepancies. The intermediate domain is generated by transforming source-domain images into target-like images. This approach progressively addresses adaptation subtasks: first adapting from the source to the intermediate domain, then to the target domain. Additionally, a weighted loss is introduced in the second stage to balance varying image quality within the intermediate domain. This approach incrementally tackles adaptation subtasks: initially adapting from the source domain to the intermediate domain, and subsequently to the target domain. Moreover, a weighted loss function is incorporated in the second stage to balance the varying image qualities within the intermediate domain. The method further mitigates domain shifts across diverse scenarios, weather conditions, and large-scale datasets. Concurrently, addressing the small-sample degradation problem, Qian et al (Qian et al., 2025b). proposed an IWNC-based RUL prediction framework that addresses multi-parameter nonlinear degradation via an enhanced Wasserstein GAN, a nonlinear Wiener process, and a Copula function. Qian et al (Qian et al., 2025a). proposed an innovative adaptive data augmentation method for reliability assessment. By combining the nonlinear Wiener process with the AAM-GAN (Adaptive Augmentation Magnitude Generative Adversarial Network) algorithm, this approach dynamically expands the sample size, addressing the evaluation bias issues caused by insufficient samples in traditional methods.

Building on the aforementioned research, this paper introduces a dual-domain contrastive learning-guided framework tailored for low-light drone-view maritime detection. The framework integrates a dual-domain contrastive learning network as a standalone guidance module within the target detection network, facilitating knowledge transfer through joint optimization. Crucially, contrastive learning solely guides feature space alignment during the training phase, thereby eliminating any additional computational overhead during inference. This mechanism effectively reduces the computational burden while ensuring real-time performance in maritime target detection.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

A dual-domain contrastive learning framework is developed to jointly leverage frequency-domain global structural cues with spatial-domain local texture details. This framework effectively enhances feature discriminability while suppressing redundant information, thus reducing computational cost and satisfying real-time maritime target detection requirements.

-

A low-light enhancement module is proposed to address illumination imbalance in complex maritime environments. By equalizing brightness and improving image uniformity, the module increases feature separability between small targets and background clutter, thereby improving detection robustness under adverse lighting conditions.

-

A novel Locally Embedded Global Feature Extraction Module (LEGM) is designed to enhance multi-scale feature representation through the integrated modeling of local fine-grained structures and global contextual semantics. This design substantially alleviates the problems of missed detection and false positives for small maritime targets.

2 The proposed algorithm

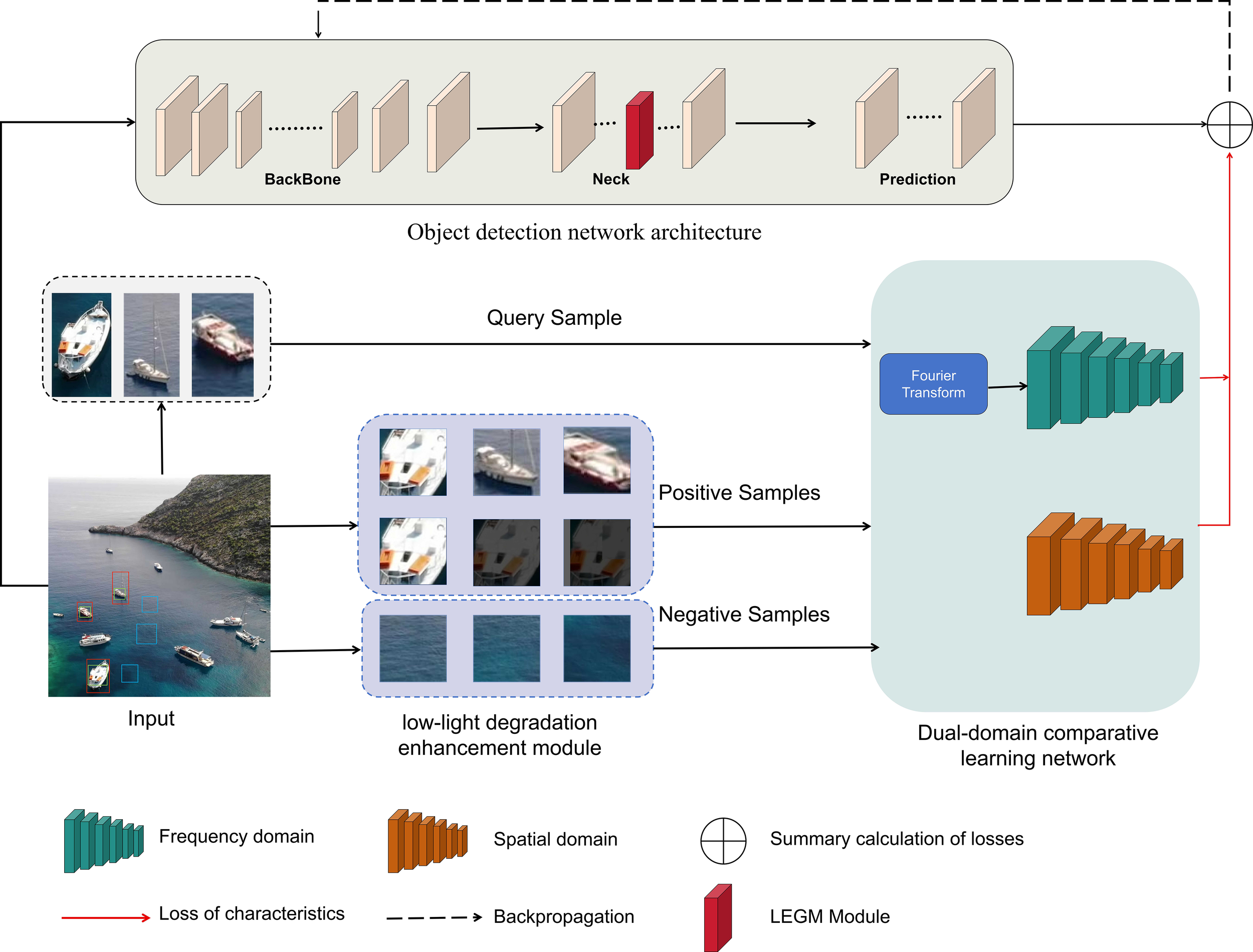

As shown in the overall process framework in Figure 1. In marine environments, images from the UAV perspective often contain small targets, and feature map sizes gradually decrease with frequent down sampling during the object detection process, making feature extraction for small targets typically challenging. Therefore, this paper proposes an algorithm composed of an object detection network and a contrastive learning network. The network integrates spatial and frequency domain information, defined as dual-domain contrastive learning, which prompt the model to identify key characteristics of small targets and construct high-quality feature descriptors. However, in marine object detection, sea surface textures and water reflections often reduce detection accuracy. Thus, the proposed algorithm incorporates a low-light degradation enhancement algorithm before dual-domain contrastive learning. This enhancement algorithm improves image quality while simulating object detection in low-light conditions, providing higher-quality and more diverse training data for subsequent algorithms. Simultaneously, the LEGM module is introduced to optimize the network structure of the object detection framework. Through effective fusion of local and global context information, it strengthens the model’s capacity to characterize blurred features and small-object features, thereby improving the model’s flexibility when handling intricate tasks. Through the above processing, the proposed algorithm covers a complete improvement pipeline from feature representation to data enhancement and then to network structure, systematically addressing the limitations of object detection algorithms in marine environment.

Figure 1

Overall network architecture.

2.1 Dual-domain contrastive learning

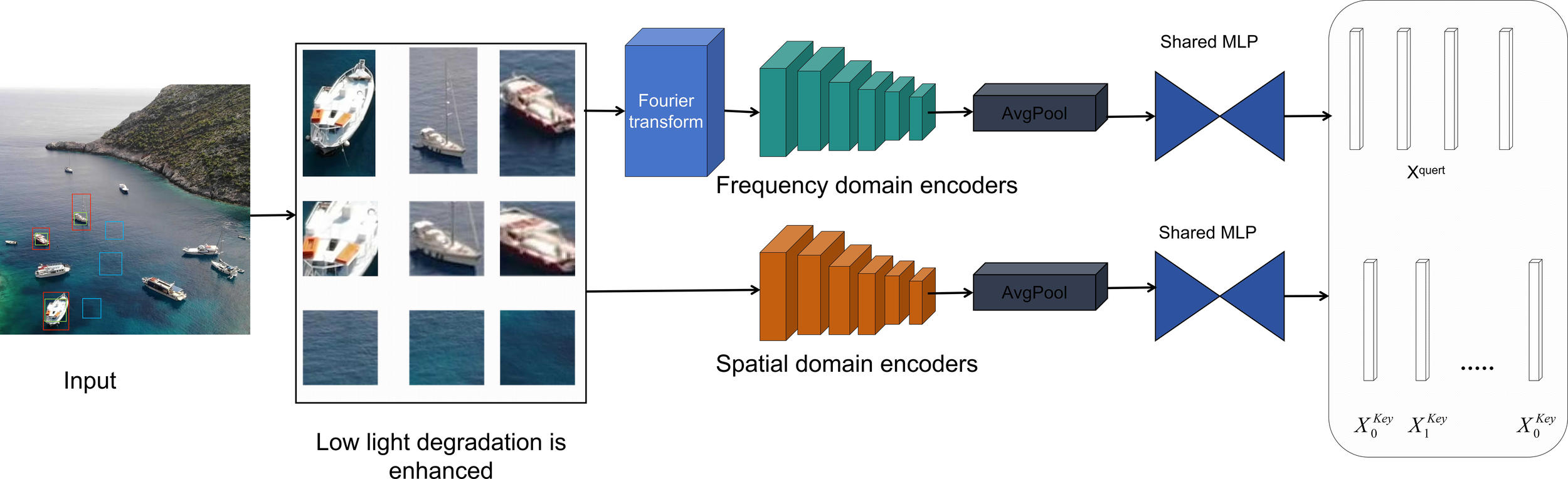

The dual-domain contrastive learning framework, illustrated in Figure 2, employs separate encoders for spatial and frequency domains, Images from the datasets are first randomly cropped into rectangular patches based on their annotations. Among these, patches with red borders denoting ground-truth bounding boxes are defined as query instances(q).Positive and negative samples for contrastive learning are then selected by comparing against these queries according to specific Intersection-over-Crop (IoC) ratio thresholds.

Figure 2

Dual-domain comparative learning network architecture.

Positive Sample (): Randomly generated crop regions are evaluated by calculating the IoC ratio—the area of overlap with any ground-truth bounding box divided by the crop area. If this ratio exceeds 2/3, the region is cropped and designated as a positive sample, marked with a green border.

Negative Sample (): Similarly, randomly generated crop regions are evaluated by calculating the IoC ratio against all ground-truth bounding boxes. If this ratio dose not exceeds 1/5, the region is cropped and designated as a negative sample, marked with a blue border.

All three types of rectangular patches are first enhanced to address low-light degradation and are then processed by structurally identical spatial and frequency-domain encoders, which consist of convolutional layers, average pooling layers, and MLPs. Following the MoCo framework (Tu et al., 2024), in the feature space, the feature representations of query and positive samples are made more similar, whereas the representations of query and negative samples are separated, the relationships within this feature space are determined by the loss function shown in Equation 1.

where stands for the quantity of negative samples, and adjusts the penalty intensity corresponding to these samples. A greater will reduce the penalty’s impact.

As a self-supervised learning strategy, contrastive learning optimizes feature space distances by attracting similar samples and repelling dissimilar ones. During training, the generated queries, positives, and negatives are fed into the spatial-domain encoder, which learns discrete feature representations. Given that objects in images may appear at diverse scales and proportions, the encoder captures scale-sensitive features (e.g., pixel distribution and relative distances) to infer actual object sizes and spatial locations. The spatial-domain encoder focuses on learning textural features of targets, enabling the network to acquire discriminative characteristics for effectively distinguishing object categories. Additionally, it extracts contextual information around targets, deepening the understanding of environmental contexts to reduce false positives and missed detection. Through this process, the semantic features acquired by the spatial encoder significantly enhance the detection ability to extract contextual information from image features, thereby improving target localization and classification precision.

These patches are also transformed via Equation 2. for frequency-domain analysis, enabling the extraction of deep semantic feature from spectral representations.

An image is represented in the frequency domain by the complex function , here and are the horizontal and vertical spatial frequencies, while and refer to the image’s width and height, respectively.

High-frequency components, which capture fine details and textures, are extracted from the amplitude spectrum via the filter specified in Equation 3. Low-frequency components, representing global structures, are correspondingly defined by Equation 4.

Where and represent the amplitude spectrums corresponding to high-frequency components and the original image, and refers to the cutoff radius for high-frequency signals.

where stands for the amplitude spectrum corresponding to low-frequency components, while represents the cutoff radius for low-frequency signals.

The frequency-domain processing branch leverages low-frequency components to extract global features that preserve fundamental structural information, even in blurred images. In contrast, high-frequency components correspond to areas with abrupt grayscale variations such as edges, fine details, textures, and high-frequency noise. By analyzing these high-frequency characteristics, the network learns discriminative patterns that effectively separate target objects from complex backgrounds. The integration of spatial and frequency domains thereby enriches feature representation, leading to improved robustness in low-light detection scenarios. This multi-domain fusion strategy not only enhances target recognition accuracy but also deepens the environmental context understanding, ultimately boosting detection performance across diverse and challenging conditions.

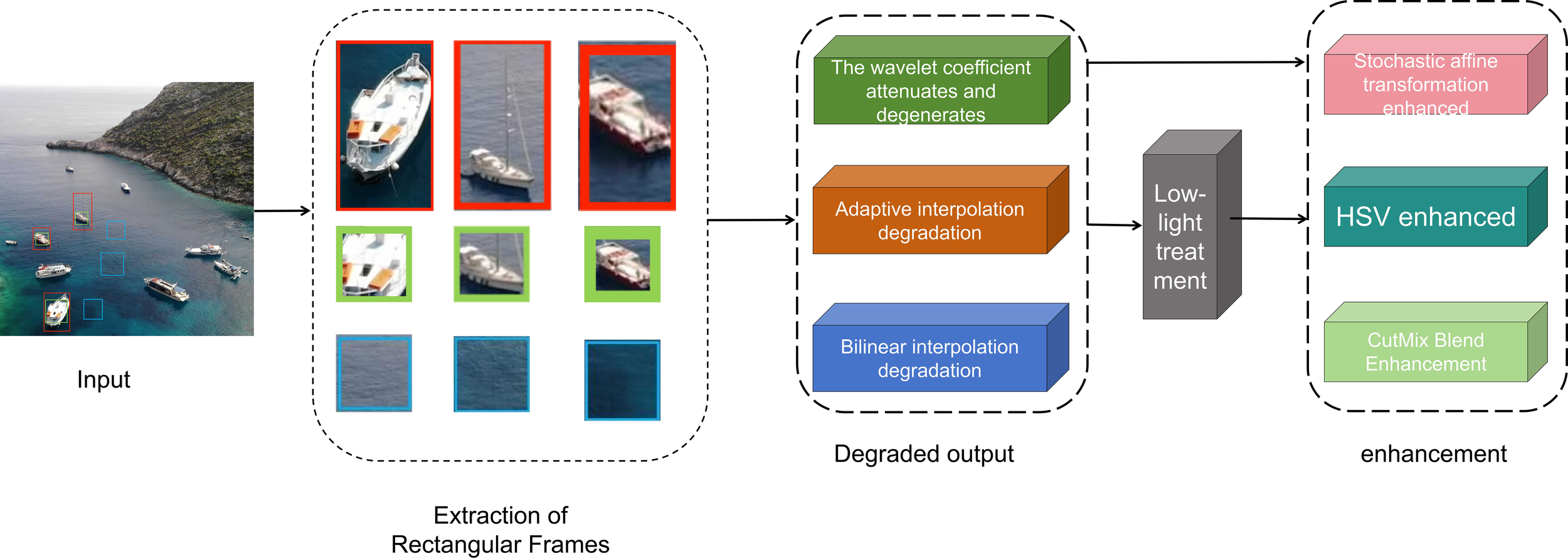

2.2 Low-light degradation enhancement

By applying low-light degradation processing to images, additional views are generated to enhance model robustness against low-quality inputs. As shown in Figure 3, before dual-domain contrastive learning, low-light degradation is applied to positive sample images. Specifically, the image degradation is divided into two groups of interpolation degradation: the first group uses wavelet coefficient attenuation degradation, adaptive interpolation degradation, and bilinear interpolation degradation; the second group randomly selects one interpolation degradation method from the three interpolation-degraded images obtained from the first group for further degradation. Subsequently, the obtained degraded images are subjected to low-light darkening processing to simulate images under low-light conditions, improving the model’s adaptability to scene variations.

Figure 3

Low-light degradation enhances network architecture.

Wavelet coefficient attenuation degradation is an image degradation method based on wavelet transform. Its basic idea is to simulate the blurring or detail loss that may occur in the process of image acquisition or transmission by attenuating the high-frequency coefficients obtained after wavelet transform of the image. Specifically, an image is a typical two-dimensional signal. The image is subjected to the two-dimensional discrete wavelet transform of Equation 5 to obtain high-frequency component , which is often expressed as HH in the image; vertical component , expressed as HL in the image; horizontal component , expressed as LH in the image; and low-frequency component , expressed as LL in the image.

In the degradation process, the main focus is on attenuating the high-frequency coefficients (HH, HL, LH), as these coefficients contain the edge and texture details of the image, and the attenuation equation is shown in Equation 6.

where is the coefficient after attenuation; is the original coefficient; is the attenuation factor, which is between 0 and 1. The smaller the attenuation factor, the more high-frequency information is lost, and the blurrier the image.

Adaptive interpolation degradation combines edges to dynamically select nearest neighbor interpolation degradation or bicubic interpolation degradation. Nearest neighbor interpolation degradation refers to selecting the nearest pixel as its pixel value. It is a simple and fast interpolation method. The core logic here is to first compute the scaling ratio using the dimensions of the original and target images; next, determine the original pixel corresponding to each target pixel via this scaling ratio, and map the original pixel’s value to the target pixel. This approach benefits from low computational load and high processing speed, yet it suffers from inferior image output, which often resulting in mosaic-like textures and jagged edges. The coordinate transformation formula for nearest neighbor interpolation is shown in Equations 7, 8 (Ding et al., 2024a):

where and represent the coordinate values corresponding to the mage, and stand for the coordinates in the target image, while refers to the scaling factor.

Bicubic interpolation degradation performs cubic interpolation using the grayscale values of 16 neighboring points around a sampled pixel, simultaneously considering both the grayscale values of directly adjacent points and their rate of change. Its computational complexity is significantly higher than that of nearest-neighbor and bilinear interpolation, yet it yields optimal image quality. The mathematical principles are illustrated in Equation 9.

Bilinear interpolation estimates pixel values at new positions by performing weighted averaging based on four adjacent pixels in both and directions. While computationally more intensive than nearest-neighbor interpolation (Ding et al., 2024a), it yields superior image quality with reduced pixelation. The method presupposes known function values at points , , , and , with the interpolated value obtained through sequential interpolation operations.

Perform interpolation in the x-direction as shown in Equations 10, 11.

Perform interpolation in the y-direction as shown in Equation 12.

Based on the above content, the conclusion can be drawn as shown in Equation 13.

Process the above-degraded image with darkness treatment to simulate low-light effects by reducing brightness and enhancing the contrast of dark areas. The key operational steps are: first, limit the intensity parameter to the 0.1–0.9 range to prevent excessive brightness or full blackness; next, convert the image from RGB to HSV color space (HSV consists of components representing Hue, Saturation, and Value); extract the Value channel and multiply it by the intensity factor to reduce brightness. Meanwhile, to increase the contrast of dark areas, gamma correction is applied to the V channel, the calculation formula is shown in Equation 14.

where represents the contrast modulation factor, denotes the baseline contrast modulation factor, and is the luminance intensity parameter.

Lastly, transform the processed HSV image back into the RGB color space.

The data augmentation strategy generates highly realistic synthetic samples to effectively expand the training set and approximate the real data distribution, this enables the model to acquire more robust feature descriptors and significantly enhance generalization capability. This study employs random affine transformations, HSV color enhancement, and CutMix blending augmentation to collaboratively optimize both original and degraded image data.

Random affine transformation refers to linear transformation plus translation transformation. The corresponding enhancement effect can be achieved by defining different transformation matrices M for different transformation methods. HSV enhancement realizes image enhancement by randomly adjusting hue, saturation, and brightness. CutMix-based data (Yuanbo, 2023) augmentation creates new training samples by cropping a segment from two randomly chosen images and exchanging these cropped parts. Specifically, first, two images are randomly selected, and a rectangular area is randomly cropped from each image; then, the cropped areas of the two images are swapped and merged into a new image; finally, the label of the resulting image is determined by computing a weighted average of the two original images’ labels, where weights are based on the cropped regions’ area.

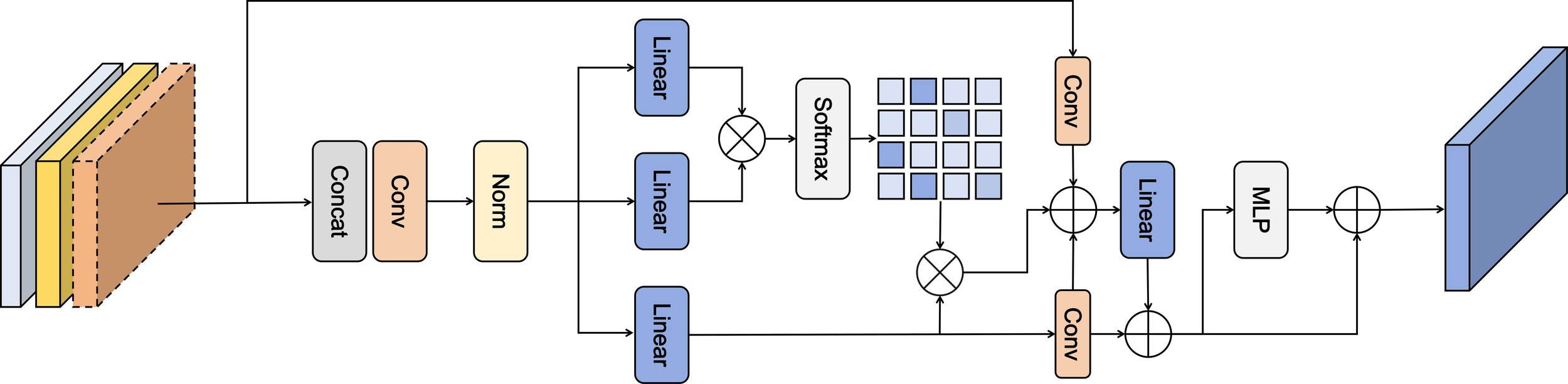

2.3 Locally embedded global feature extraction module

For balancing detection precision and operational efficiency, this study selects the YOLOv8n framework. Specifically, its Backbone achieves lightweight design through the C2f module while preserving the SPPF module for multi-scale optimization. The Neck fuses multi-scale semantic features and introduces the Locally Embedded Global Feature Extraction Module (LEGM) to strengthen channel-level feature integration. The Head employs a decoupled architecture to segregate regression and classification tasks, thereby enabling efficient detection implementation.

Given the suboptimal object detection results in marine scene images, which is usually caused by factors such as sea surface reflection and variable scales, we introduce the LEGM module. Its theoretical basis lies in that the features extracted by convolutional networks contain a large amount of local information, and combining convolutional layers with self-attention mechanisms can simultaneously obtain local and global features, realizing effective feature fusion. The general structural framework of this module is illustrated in Figure 4. This module can help solve the problems of missed detection or false detection that may occur when traditional one-stage detectors handle complex scenes. Through interactive operations on feature maps of different scales, it enables low-level local features to better utilize high-level semantic information, thereby improving detection accuracy.

Figure 4

LEGM network architecture.

The LEGM module is primarily composed of three components:

-

Input part: Analyze the multi-scale features of the input image and first perform concatenation.

-

Feature processing: Conduct preliminary processing on the concatenated features through a convolution layer (Conv) and a normalization layer (Norm); then perform transformation via a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), followed by further processing using a linear layer (Linear); then generate an attention weight matrix using the Softmax function.

-

Feature fusion: Conduct element-wise multiplication of the attention weight matrix and input features, then process the result with convolution and linear layers; next, add this output to the original input features, filter the combined result, and ultimately output the refined features using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP).

2.4 The loss function

During training, the object detection network utilizes full images as input, while the contrastive learning network employs positive and negative sample images. These two separate loss functions are merged into a single integrated loss function, detailed in Equation 15.

where denotes the object detection loss function, stands for the contrastive learning loss function, and refers to the weight coefficient assigned to the contrastive learning loss.

Loss function employs a multi-task joint optimization framework, integrating Bounding Box Regression Loss, Confidence Loss, and Classification Loss to optimize localization, confidence prediction, and classification tasks respectively. The overall expression is shown in Equation 16.

where is the classification loss; is the weight coefficient of the classification loss, with a value of 0.5; is the bounding box regression loss; is the weight coefficient of the bounding box regression loss, with a value of 7.5; is the confidence loss; and is the confidence loss coefficient, with a value of 1.5.

For Bounding Box Regression Loss, we use the CIoU (Complete Intersection over Union) loss function, which metric integrates overlap region, center-point distance, and aspect ratio variance to optimize the localization of predicted boxes. Unlike standard IoU, CloU offers more comprehensive supervision for box adjustments, particularly in handling aspect ratio discrepancies. The Confidence Loss addresses the challenge of significant positive-negative sample imbalance by applying the Focal Loss, which automatically reduces the impact of well-classified samples during training. For multi-label Classification Loss, the framework employs Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) to distinguish object categories.

The framework employs cross-domain contrastive guidance to enable collaborative training. By jointly optimizing the corresponding loss with the detection objective, this mechanism generates domain-invariant features that are fed into the detection network. The resulting joint backpropagation iteratively updates parameters, improving detection performance and lowering deployment costs.

3 Experiments and results

3.1 Datasets

SeaDronessee (Varga et al., 2022) a large-scale benchmark for visual detection and tracking developed by the University of Tübingen, focuses on human detection in marine environments. It contains over 54,000 frames (400k instances) captured from altitudes of 5–260 meters and perspectives of 0–90°, with detailed metadata. The dataset supports multimodal system development for maritime search and rescue by providing altitude, perspective, and speed information to improve detection accuracy. It also includes multispectral imagery (e.g., near-infrared and red-edge) to enhance detection capability. The data is split into 5,630 training, 859 validation, and 1,796 test images.

The AFO datasets (Wang et al., 2025),the first open datasets for maritime search and rescue, consists of 39,991 annotated images extracted from 50 video clips, containing 3,647 object instances in total. These images are divided into training (67.4% of objects), testing (19.12%), and validation (13.48%) subsets. The datasets is derived from 40,000 drone-captured aerial videos featuring manually annotated humans and floating objects, many of small size.

3.2 Experimental setup and evaluation metrics

Our model was trained on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 Ti GPU under the Windows OS; the software setup consists of CUDA 11.8, CUDNN 8.0, and PyTorch as the deep learning framework. During training, we adopted the ADAM optimizer, configured with an initial learning rate of 0.015 and a momentum of 0.937; the batch size was set to 8, and the training was run for 200 epochs.

The evaluation framework employs precision, recall, mean Average Precision (mAP), computational complexity, and parameter count as core metrics. Precision quantifies the accuracy of positive predictions in classification tasks, while recall assesses the model’s capability to identify all relevant positive instances. The mAP serves as a comprehensive indicator for object detection and information retrieval performance. Furthermore, parameter volume and computational demands are key measures of model complexity and efficiency. The evaluation indicators are shown in Equations 17–19.

3.3 Formatting of mathematical components

To analyze how various modules affect the proposed algorithm, this study carries out ablation experiments with YOLOv8n as the base model. The marker denotes that the relevant module is employed in the set up, while the x means it is not adopted. The evaluation results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| YOLOv8 | Dual-domain comparison | Low light degradation | LEGM | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 | Precision | Recall | GFLOPs | Params (M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | × | × | × | 0.908 | 0.617 | 0.912 | 0.852 | 8.1 | 3.01 | |

| B | × | × | 0.911 | 0.62 | 0.913 | 0.855 | 8.1 | 3.01 | ||

| C | × | 0.92 | 0.627 | 0.899 | 0.866 | 8.1 | 3.01 | |||

| D | 0.927 | 0.628 | 0.906 | 0.872 | 10.1 | 4.07 |

Ablation experimental results.

Algorithm B integrates the baseline model with dual-domain contrastive learning. As the contrastive component only guides the training of the detection network without introducing additional structural modules, the model maintains its original parameter size and computational load. Enhanced feature representations in both spatial and frequency domains lead to improvements across all four key metrics: P, R, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95. Algorithm C extends Algorithm B by adding a low-light degradation enhancement module, which effectively counters accuracy loss from uneven illumination and blurred small targets in maritime environments, thereby boosting detection performance. A side effect of this enhancement is the reduction in overall brightness, which increases false detection rates and consequently lowers Precision (P). Algorithm D further incorporates the LEGM module into the detection network. The strengthened capability of LEGM in capturing fine-grained features of small targets raises mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 to 92.7% and 62.8%, respectively. As summarized in Table 1, all proposed enhancements contribute to accuracy gains at varying levels, confirming the efficacy of our approach.

3.4 Formatting of mathematical components

To validate algorithm feasibility, a comparative analysis was conducted against established detectors including Fast-RCNN, SSD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9t, and YOLOv10n. The comparative results on the SeaDronesSee dataset are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Model | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 | FLOPs(G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-RCNN | 0.5779 | 0.3408 | 223.6 |

| SSD | 0.5747 | 0.2707 | 88.1 |

| YOLOv5s | 0.654 | 0.386 | 23.8 |

| YOLOv6n | 0.606 | 0.359 | 11.8 |

| YOLOv8s | 0.6465 | 0.3891 | 28.4 |

| YOLOv8n(base) | 0.628 | 0.376 | 8.1 |

| YOLOv9t | 0.645 | 0.379 | 6.4 |

| YOLOv10n | 0.641 | 0.382 | 8.2 |

| The Proposed Algorithm | 0.671% | 0.395 | 10.1 |

Performance comparison of various algorithms.

As shown in Table 2, compared to the two-stage object detection algorithm Fast-RCNN, our algorithm achieves an improvement of 9.31% in mAP@0.5 and 5.42% in mAP@0.5:0.95 on the SeaDronesSee dataset. Compared to the single-stage object detection algorithm SSD, it improves mAP@0.5 by 9.63% and mAP@0.5:0.95 by 12.43%. Furthermore, compared to the YOLO series algorithms, our method achieves improvements in mAP@0.5 of 1.7%, 6.5%, 2.45%, 4.3%, 2.6% and 3% against YOLOv5s, YOLOv6n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t and YOLOv10n, respectively, and improvements in mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.9%, 3.6%, 0.59%, 1.9%, 1.6% and 1.3%, respectively. In terms of computational efficiency, our model requires 10.1G FLOPs, reflecting a good balance between accuracy and complexity. Although YOLOv9t requires only 6.4G FLOPs, making it the most lightweight among the compared algorithms, our model achieves higher detection accuracy with moderate computational overhead. In summary, compared to other models, our detection algorithm not only has the smallest number of parameters but also achieves the highest average precision, demonstrating certain advantages in both accuracy and real-time performance for maritime small object detection.

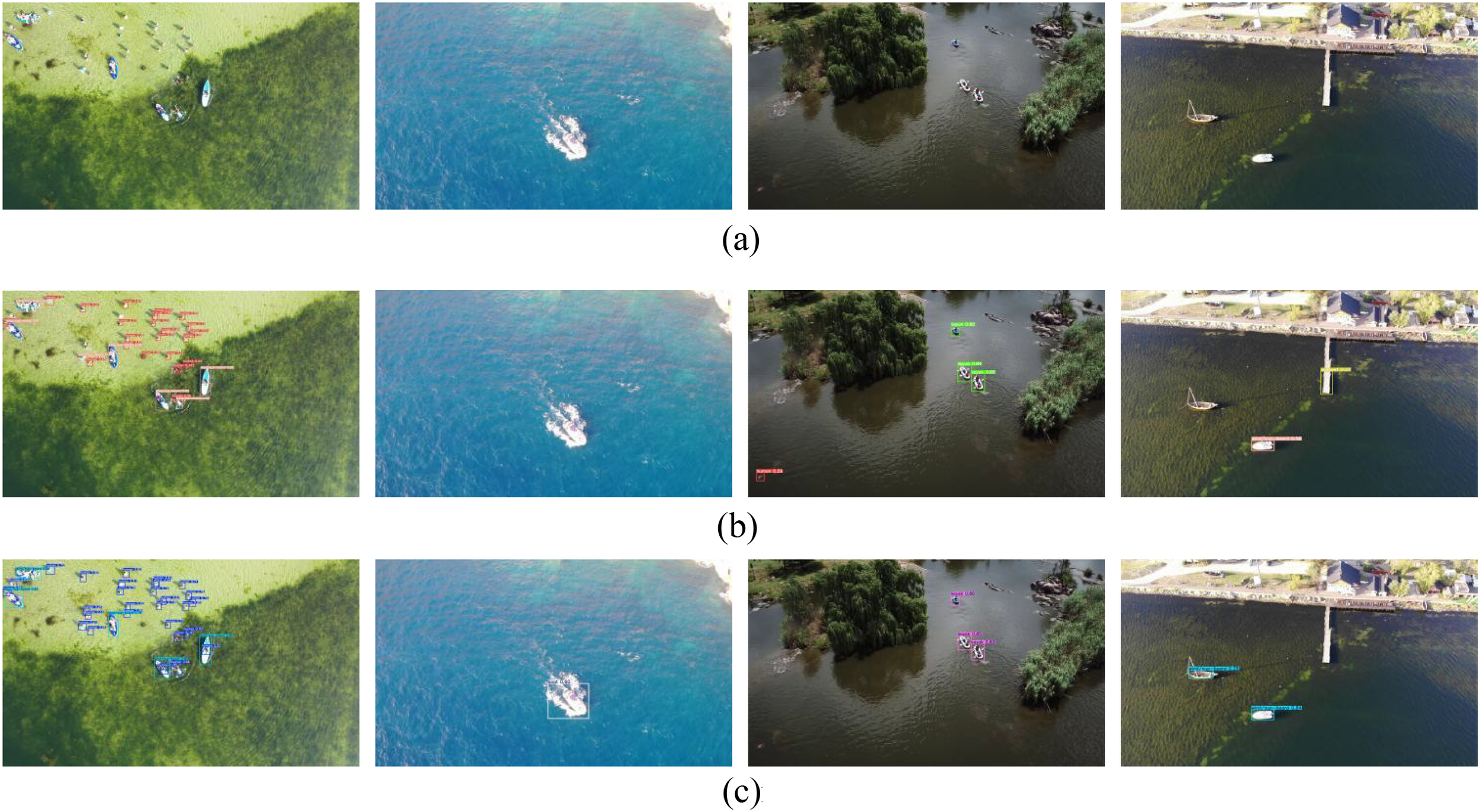

3.5 Visualization

A subset of images representing various marine environments, specifically in sea conditions, illumination, viewpoints, and target scales, was randomly drawn from the AFO datasets for detection evaluation. As illustrated in Figure 5, the three rows correspond to original images, detection outputs of the YOLOv8 model, and results of our proposed method.

Figure 5

Visualize the result. (a) Original images. (b) Detection outputs of the YOLOv8 model. (c) Results of our proposed method.

Through qualitative analysis of the detection results shown in Figure 5, this section reveals the performance differences between the original YOLOv8 algorithm and the proposed algorithm in marine small target detection. The following discussion explores several fundamental limitations exposed by the original YOLOv8 algorithm in the marine small target detection task from multiple dimensions:

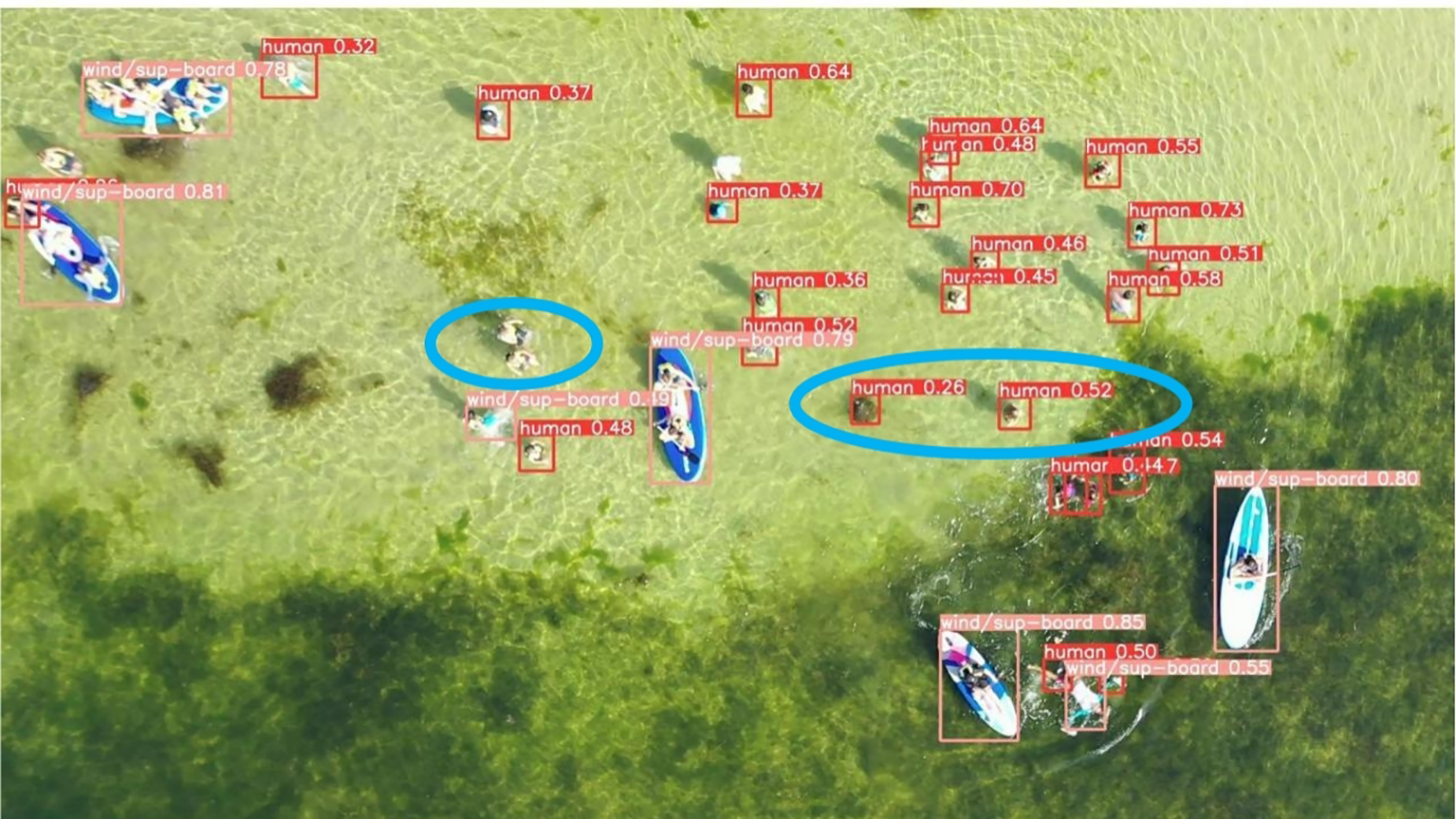

Detection Failure in Target-Dense Scenes: In the first column of dense target images, the YOLOv8 algorithm exhibits both missed detection and false detection of small targets, as indicated by the blue boxes in Figure 6. This issue stems from insufficient feature discrimination capability in complex backgrounds. When multiple small targets are densely distributed, the receptive field design of YOLOv8 encounters challenges in effectively distinguishing adjacent targets, thereby resulting in feature confusion during the feature extraction procedure. Additionally, interference factors such as wave textures and light reflections in marine environments are misidentified as targets, resulting in false detection.

Figure 6

Missed detection and false detection in the original YOLOv8 algorithm.

Missed Detection of Single Target: It is particularly noteworthy that in the second column image, despite ideal lighting conditions and the presence of only a single boat target in the scene, YOLOv8 still exhibited a significant missed detection. This indicates that the issue arises not only from environmental complexity but also from the algorithm’s inherent insufficient sensitivity to the features of small targets. The feature information of small targets is severely lost during multiple down-sampling processes, preventing the model from retaining sufficient discriminative information in the deep feature maps.

Insufficient Model Generalization Capability: The false detection phenomena observed in the third and fourth columns under similar lighting conditions further confirm the limitations of YOLOv8’s generalization ability in marine environments. The algorithm exhibits poor adaptability to variations in lighting and background interference, making it difficult to distinguish real targets from visually similar noise.

In summary, through the synergistic effect of dual-domain contrastive learning, low-light degradation enhancement, and the LEGM module, the proposed algorithm effectively addresses the inherent limitations of YOLOv8 in marine small target detection. It significantly reduces both missed and false detection rates while maintaining high confidence, demonstrating clear performance superiority and practical application value.

4 Conclusions

This study proposes an innovative method for small target detection in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) maritime environments. Its core innovation lies in the joint training of a target detection network with dual-domain contrastive learning (incorporating both spatial and frequency domains). A low-light degradation enhancement module is introduced prior to the dual-domain contrastive learning for producing varied training samples and boosting the model’s robustness against noise and blurring. Simultaneously, an LEGM module is embedded into the detection network to strengthen the integration of local and global features, which notably elevates the detection precision and stability of small objects in intricate marine scenes. However, limitations remain, such as insufficient adaptability to extreme conditions like heavy rain and dense fog, and computational complexity that may constrain real-time deployment on resource-limited UAVs. Potential future work may investigate multi-modal data fusion (such as infrared and radar signals) to improve cross-domain generalization performance, develop dynamic adaptive mechanisms to cope with sudden environmental changes, and further optimize model lightweighting and edge deployment efficiency.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LL: Software, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation. JX: Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft. GF: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. YW: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. FR: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Fund Project for Basic Scientific Research Expenses of Central Universities, grant number 25CAFUC03021, Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province, grant number 2024NSFSC0507 and Research on Laser Imaging Detection Technology for Integrated Land-Air UAVs, grant number JCKEYS2025411011.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Cheng G. Yuan X. Yao X. Yan K. Zeng Q. Xie X. et al . (2023). Towards large-scale small object detection: Survey and benchmarks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell45:13467–13488. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3290594

2

Ding S. Zhi X. Lyu Y. Ji Y. Guo W. (2024a). Deep learning for daily 2-m temperature downscaling. Earth Space Sci.11, e2023EA003227. doi: 10.1029/2023EA003227

3

Girshick R. (2015). “ FastR-CNN,” in 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 1440–1448. Santiago, Chile: IEEE.

4

Hsu H. K. Yao C. H. Tsai Y. H. Hung W. C. Tseng H. Y. Singh M. et al . (2020). “ Progressive domain adaptation for object detection,” in 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). 749–757. Snowmass, CO, USA: IEEE.

5

Hu Q. Hu S. Liu S. (2022). BANet: A balance attention network for anchor-free ship detection in SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens.60, 1–12. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2022.3146027

6

Lin T. Y. Goyal P. Girshick R. He K. Dollár P. (2017). “ Focal loss for dense object detection,” in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 2980–2988. Venice, Italy: IEEE.

7

Lin T. Y. Maire M. Belongie S. Hays J. Perona P. Ramanan D. et al . (2014). “ Microsoft coco: Common objects in context,” in Computer VisionECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, urich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, PartV 13. 740–755 (Cham, Switzerland: Springer).

8

Liu L. Hu Z. Dai Y. Ma X. Deng P. (2023). Isa: Ingenious siamese attention for object detection algorithms towardscomplex scenes. ISA Trans.143, 205–220. doi: 10.1016/j.isatra.2023.09.001

9

Liu W. Ren G. Yu R. Guo S. Zhu J. Zhang L. et al . (2022). “ Image-adaptive YOLO for object detection in adverse weather conditions,” in Proceedings of the 39th Annual AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 36. 1792–1800. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press.

10

Ma Y. Guan D. Deng Y. Yuan W. Wei M. (2024). 3SD-Net: SAR small ship detection neural network. IEEE Trans. On Geosci. And Remote Sens62:1–13. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2024.3454308

11

Qian C. Li L. Zhang S. Ming H. Yang D. Ren Y. et al . (2025a). An adaptive data augmentation-based reliability evaluation and analysis of lithium-ion batteries considering significant inconsistency in degradation. J. Energy Storage134, 118158. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2025.118158

12

Qian C. Li Y. Zhu Y. Yang D. Ren Y. Xia Q. et al . (2025b). Remaining useful life prediction considering correlated multi-parameter nonlinear degradation and small sample conditions. Comput. Ind. Eng.210, 111567. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2025.111567 doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031

13

Redmon J. Divvala S. Girshick R. Farhadi A. (2016). “ You only look once: uni⁃fied, real-time object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conferenceon Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 779–788.

14

Ren S. He K. Girshick R. Sun J. (2016). FasterR-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 39, 1137–1149. USA: IEEE. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031

15

Tu X. He Z. Fu G. Liu J. Zhong M. Zhou C. et al . (2024). Learn discriminative features for small object detection through multi-scale image degradation with contrastive learning. IEICE Trans. Inf. SystE108D:371–383. doi: 10.1587/transinf.2024EDP7204

16

Varga L. A. Kiefer B. Messmer M. Zell A. (2022). “ Seadronessee: A maritime benchmark for detecting humans in open water,” in 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). 2260–2270. Waikoloa, HI, USA: IEEE.

17

Wang S. Cai Yuan J. (2023). Automatic SAR ship detection based on multifeature fusion network in spatialand frequency domains. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens.61, 1–11. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2023.3267495

18

Wang R. Liang T. (2024). The “Belt and Road” Initiative and China’s sporting goods exports: Basic characteristics and policy evaluation. Heliyon10, e33189. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33189

19

Wang Y. Liu J. Zhao J. Li Z. Yan Y. Yan X. et al . (2025). LCSC-UAVNet: A high-precision and lightweight model for small-object identification and detection in maritime UAV perspective. Drones (2504-446X)9, 100. doi: 10.3390/drones9020100

20

Wang Z. Chen J. Jiang Y. G. (2021). “ Visual co-occurrence alignment learning for weakly-supervised video moment retrieval,” in Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. 1459–1468. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

21

Yang Z. Y. Cao X. Xu R. Z. Hong W. C. Sun S. L. (2024). Applications of chaotic quantum adaptive satin bower bird optimizer algorithm in berth-tugboat-quay crane allocation optimization. Expert Syst. Appl.237, 121471. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121471

22

Yasir M. Liu S. Mingming X. Wan J. Pirasteh S. Dang K. B. et al . (2024). ShipGeoNet: SAR image-based geometric feature extraction of ships using convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens.62, 1–13. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2024.3352150

23

Yuanbo Y. (2023). Application of Object Detection and Image Generation in Capsule Endoscopy Assisted Diagnosis System (Singapore: National University of Singapore).

24

Yue T. Yang Y. Niu J. M. (2021). “ A light-weight ship detection and recognition method based onYOLOv4,” in 2021 4th International Conference on Advanced Electronic Materials, Computers andSoftware Engineering (AEMCSE). 661–670 (Changsha, China: IEEE).

25

Zhang H. Wang Y. Dayoub F. Sunderhauf N. (2021). “ Varifocalnet: An iou-aware dense object detector,” in 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 8514–8523. Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE.

26

Zheng A. Zhang Y. Zhang X. Qi X. Sun J. (2022). “ Progressive end-to-end object detection in crowded scenes,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 857–866. Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society.

Summary

Keywords

contrastive learning, deep learning, low-light degradation enhancement, marine aerial object detection, unmanned aerial vehicle

Citation

Liu L, Xu J, Fu G, Zhang X, Wang Y and Fan R (2026) Maritime aerial object detection via dual-domain contrastive learning and low-light degradation enhancement. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1778155. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1778155

Received

30 December 2025

Revised

16 January 2026

Accepted

26 January 2026

Published

16 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Zifei Xu, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Xuri Xin, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom

Chengbo Wang, Xidian University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Liu, Xu, Fu, Zhang, Wang and Fan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gui Fu, abyfugui@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.