Abstract

Background:

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the leading causes of blindness globally, among individuals with diabetes mellitus. Early detection through screening can help in preventing disease progression. In recent advancements artificial Intelligence assisted screening has emerged as an alternative to traditional manual screening methods. This diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) review aims to compare the sensitivity and specificity of AI versus manual screening for detecting diabetic retinopathy, focusing on both dilated and un-dilated eyes.

Methods:

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted for comparison of AI vs. manual screening of diabetic retinopathy using 25 observational (cross sectional, validation and cohort) studies with total images of 613,690 used for screening published between January 2015 and December 2024. Outcomes of the study was sensitivity, and specificity. Risk of bias was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool for validation studies, the AXIS tool for cross-sectional studies, and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.

Results:

The results of this meta-analysis showed that for un-dilated eyes, AI screening showed pooled sensitivity of 0.90 [95% CI: 0.85–0.94] and pooled specificity of 0.94 [95% CI: 0.91–0.96] while manual screening shows pooled sensitivity of 0.79 [95% CI: 0.60–0.91] and pooled specificity of 0.99 [95% CI: 0.98–0.99]. For dilated eyes the pooled sensitivity of AI screening is 0.95 [95% CI: 0.91–0.97] and pooled specificity is 0.87 [95% CI: 0.79–0.92], while manual screening sensitivity is 0.90 [95% CI: 0.87–0.92] and specificity is 0.99 [95% CI: 0.99–1.00]. These data show comparable sensitivities and specificities of AI and manual screening, with AI performing better in sensitivity.

Conclusion:

AI-assisted screening for diabetic retinopathy shows comparable sensitivity and specificity compared to manual screening. These results suggest that AI can be a reliable alternative in clinical settings, with increased early detection rates and reducing the burden on ophthalmologists. Further research is needed to validate these findings.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/home, CRD42024596611.

Introduction

Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) is one of the most prevalent microvascular complications of diabetes, characterized by damage to the retina due to prolonged hyperglycemia. It remains a leading cause of blindness globally, particularly among working-age adults. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 422 million people worldwide have diabetes (1), with approximately 103.12 million adult individuals affected by diabetic retinopathy and 160.50 million by 2045 (2). In advanced stages, untreated DR can lead to severe vision impairment and blindness. According to a 2023 global report on vision by the WHO report globally distance vision impairment or blindness from diabetic retinopathy are 3.9 million (3). Early detection and timely treatment can significantly reduce the risk of vision loss, but widespread screening remains a challenge, particularly in low-resource settings.

Screening for diabetic retinopathy has traditionally been performed through manual methods, including fundus photography, direct ophthalmoscopy, mydriatic and non mydriatic retinal photography, slit lamp microscopy, and retinal video recording conducted by trained ophthalmologists. However, these methods are often time-consuming and require specialized equipment and personnel, limiting their availability in certain regions (4). Recent technological advancements have led to the development of automated screening methods using artificial intelligence (AI). AI-based algorithms, particularly deep learning models, can analyze retinal images and detect signs of DR with comparable sensitivity and specificity to human graders. These systems have the potential to increase screening efficiency, reduce costs, and provide access to screening in underserved populations. AI has been recognized for its ability to identify DR and classify the severity of the condition, making it a valuable tool in large-scale screening programs.

There are few systematic reviews and meta-analyses which have evaluated the performance of AI-based systems for DR screening. Meta-analysis reported high sensitivity and specificity for AI algorithms (5–8). Another review (9) supported these findings but highlighted the variability in performance. However there is no review on comparison of AI vs. manual method to clarify the role of AI in different screening contexts, particularly in comparison to manual methods.

This Review aims to evaluate the performance of AI versus manual screening in DR detection. We systematically review the sensitivity and specificity of AI and manual methods, with a focus on both dilated and un-dilated eye conditions.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a literature search for AI and manual screening methods of diabetic retinopathy using PubMed and Google Scholar to identify relevant studies published between January 2015 to September 2024 and a second search was done in Feb 2025 which added 13 studies to included studies which become 25 included studies. Search strategy contain mesh terms and keywords which included “diabetic retinopathy,” “artificial intelligence,” “deep learning,” “manual screening,” and “automated detection.” Only English language articles were included if they show AI-based or manual-based screening methods for DR detection and reported sensitivity and specificity outcomes.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were observational or validation and evaluated AI algorithms or manual screening for DR with patients aged 15 to 90 years diagnosed with DR and reported sensitivity and specificity outcomes for either dilated or un-dilated eye conditions. Studies were excluded if they did not report the outcomes of interest (specificity and sensitivity), the author of the studies did not respond or if the full text were not available.

Study selection

Initially two independent reviewers screened the articles by titles and abstracts. Once the articles met the inclusion criteria or were uncertain than full texts were obtained for those. The same reviewers then independently assessed the full texts. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or, if needed, consultation with a third reviewer. PRISMA flow diagram was used for documentation of selection process Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram for included studies.

Quality assessment

Each study was assessed for quality by two independent reviewers to evaluate selection bias, outcome/exposure assessment bias, follow-up bias, measurement bias, sample representativeness, reporting bias, index test bias, reference standard bias, flow and timing bias, and ethical considerations bias was evaluated. Three different tools QUADAS-2, AXIS tool, and Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used according to type of studies (validation study, cross-sectional and cohort respectively) to evaluate risk of bias, which were used for strength of evidence of meta-analysis results.

Data extraction

Sensitivity and specificity data for AI and manual screening methods were extracted using a standardized data collection form for dilated or un-dilated eyes. Extracted information included study characteristics such as first author, country, number of participants, number of images, age of participants, comparison to human grader, photographic protocol, reference standard and outcomes of interest like sensitivity, and specificity. Two reviewers independently extracted data to minimize bias, by consensus or consulting a third reviewer disagreements were resolved. The information was initially entered into Excel tables and then transferred to Review Manager 5.4 and R-software for analysis. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies, the AXIS tool for cross-sectional studies, and the QUADAS-2 tool for validation studies.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 25 studies met the inclusion criteria of this review which evaluated Artificial intelligence based screening and manual screening for diabetic retinopathy. Twelve studies reported images of un-dilated eyes screened by AI-based or manual methods, while 14 studies show dilated eyes images screened by AI-based and manual methods. Twelve out of 25 studies were prospective (10–21), and 13 were retrospective design (22–34).

The range of sample size is from 54 to 5,738 in 19 studies with total participants of 29,358 while six studies did not mentioned number of participants but only images, 613,690 images in 25 studies were used for screening process, in a broad geographic range of settings (out patients, hospital, community based and nationwide survey) and populations. The details are given in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study | Country | Study setting | No. of images | No. of participants | Prospective | Compared to human graders | Photographic protocol | Reference standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | Singapore | Community-based and clinic-based populations | 225,302 | Not mentioned | No | Yes | 2 fields images, Mydriasis | Grading by a retinal specialist (>5 years’ experience in conducting diabetic retinopathy assessment) |

| Sosale et al. 2020 (15) | India | Outpatient | 618 | 297 | Yes | Yes | 3-fields dilated retinal imaging, Mydriasis | Adjudicated diagnosis of the two fellowship-trained vitreoretinal specialists |

| Surya et al. 2023 (16) | India | Outpatient | 1,234 | 1,085 | Yes | Yes | 5 fields imaging, No Mydriasis | Diagnosis made by the specialist ophthalmologists |

| Piatti et al. 2024 (13) | Italy | Outpatient | 602 | 598 | Yes | Yes | 2 field imaging, Mydriasis | Classification of the retinal images by the human ophthalmologist grader |

| Sedova et al. 2022 (14) | Austria | Outpatient | 113 | 54 | Yes | Yes | 45-degree, 2 fields imaging, No Mydriasis | Manual grading of images by retina specialists |

| Ipp 2021 (10) | United states | Outpatient | 4,004 | 893 | Yes | Yes | 4-wide field imaging for no Mydriasis and 2 fields imaging No Mydriasis | Grading of 4-wide-field stereoscopic dilated fundus photographs by the WFPRC |

| Tokuda et al. 2022 (17) | Japan | Inpatient | 69 | 70 | Yes | No | 45-degree, no mydriasis | Grading of the fundus images by three retinal experts according to the ICDRS scale |

| Acharyya et al. 2024 (22) | India | Outpatient | 1,783 | Not mentioned | No | Yes | 45-degree, no mydriasis | Consensus of three blinded vitreoretinal specialists, with an arbitrator resolving any disagreements. |

| Arenas-Cavalli et al. 2022 (23) | Chile | Outpatient | 1,142 | 1,123 | No | Yes | 45-degree, 2 fields, variable for case to case | assessment performed remotely by a clinical ophthalmologist. |

| Li et al. 2022 (11) | China | Hospital-based study | 1,464 | 1,147 | Yes | Yes | 45-degree, no mydriasis | Grading of the retinal fundus images by a certified retinal specialist with more than 12 years of experience, who used the 5-point (ICDRS) scale to assign grades |

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | Thailand | Nationwide screening program | 11,148 | 5,738 | No | Yes | 45-degree, 1 field, no mydriasis | Grading of the retinal photographs by a panel of three IRS |

| Lupidi et al. 2023 (12) | Italy | Outpatient | 831 | 251 | Yes | Yes | 50-degree, 1 field, no mydriasis | Fundus biomicroscopic examination by an experienced retina specialist |

| González-Gonzalo et al. 2020 (26) | Sweden | Dataset | 600 | 288 | No | Yes | 45-degree field, no mdriasis | Certified ophthalmologist with over 12 years of experience |

| Lin et al. 2018 (27) | United states | Dataset | 33,000 | No | no | not mentioned | Well-trained clinicians according to the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy scale | |

| Li et al. 2019 (28) | China | Hospital-based study | 19,233 | 5,278 | No | Yes | Inner circle of retina | Expert committee of three senior ophthalmologists |

| Soto-Pedre et al. 2015 (18) | Spain | Dataset | 10,556 | 5,278 | Yes | Yes | 45-degree field, mdriasis | One retinal specialist |

| Hansen et al. 2015 (29) | Kenya | Community-based | 6,788 | 3,460 | No | Yes | 2 field, mydraisis | Moorfields Eye Hospitals Reading Centre in the UK |

| Rajalakshmi et al. 2018 (19) | India | Hospital-based study | 2,408 | 301 | Yes | Yes | 45-degree field, mdriasis | Ophthalmologists (retina specialists) |

| Gargeya and Leng 2017 (30) | United states | Dataset | 75,137 | Not mentioned | No | Yes | inner retinal circle | Panel of human retinal specialists |

| Wang et al. 2018 (20) | India | Outpatient | 1,661 | 383 | Yes | Yes | non-steered central image, mydriasis | Certified diabetic retinopathy (DR) graders at the Doheny Image Reading Center (DIRC) |

| Abràmoff et al. 2016 (31) | United states | Dataset | 1,748 | 874 | No | Yes | 45-degree field, mdriasis | Three US Board certified retinal specialists |

| Zhang et al. 2019 (32) | China | Hospital-based study | 13,767 | 1,872 | No | Yes | 45-degree field, mdriasis | One retinal specialist with over 27 years of experience and two ophthalmologists with over 5 years of experience |

| Li et al. 2018 (21) | China and Australia | Hospital-based study | 106,244 | Not mentioned | Yes | Yes | 45-degree field, mdriasis and non mydraisis | Panel of ophthalmologists |

| Zhang et al. 2022 (33) | China | Dataset | 92,894 | Not mentioned | No | Yes | Fundus images | Ophthalmologist used international grading system for diabetic retinopathy |

| Kumar et al. 2016 (34) | India | Hospital-based study | 1,344 | 368 | No | Yes | 50-degree field, mdriasis | Panel of expert ophthalmologists at the Regional Institute of Ophthalmology |

Characteristics of included studies.

WFPRC, Wisconsin Fundus Photograph Reading Center; IRS, international retina specialists; ICDRS, International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Severity scale. aThese are the external datasets for which accuracy estimates were included in the meta-analysis; datasets used for training and internal validation were not included. b. “Compared to human graders” refers to whether retinal images were graded and compared with the results provided by AI with human graders. c. Where specified the mydriatic or non-mydriatic imaging protocols were followed depending on the study setting, with multiple fields captured. d. For certain studies, the primary reference standard was provided by expert ophthalmologists or retinal specialists with a minimum of 5 years’ experience in diabetic retinopathy assessment, though in some cases, decisions were made through consensus from multiple specialists or reading centers. e. External validation of these studies was conducted in clinical settings such as hospital-based, outpatient, or community-based screening programs, as specified.

Test accuracy

The diagnostic accuracy of AI-based diabetic retinopathy (DR) screening compared to manual methods shows that, in dilated eyes, the SROC curves shows wider confidence intervals of specificities across the included studies, indicating variability in diagnostic performance.

Un-dilated eye screening tends to achieve high sensitivity and specificity values with most of the studies reporting sensitivity and specificity of more than 0.90. This suggests a reliable ability of AI algorithms to correctly identify DR in un-dilated eye examinations. The studies generally cluster around the upper-left corner of the plot, indicating strong diagnostic performance with low rates of false positives and false negatives.

Overall, these SROC plots highlight that AI models demonstrate robust diagnostic accuracy for detecting diabetic retinopathy in both dilated and un-dilated settings, with higher sensitivity and closer specificity compared to manual screening methods in most of the studies as can be seen in the Figures 2, 3.

Figure 2

SROC plot for un-dilated eyes screening.

Figure 3

SROC plot for dilated eyes screening.

Sensitivity

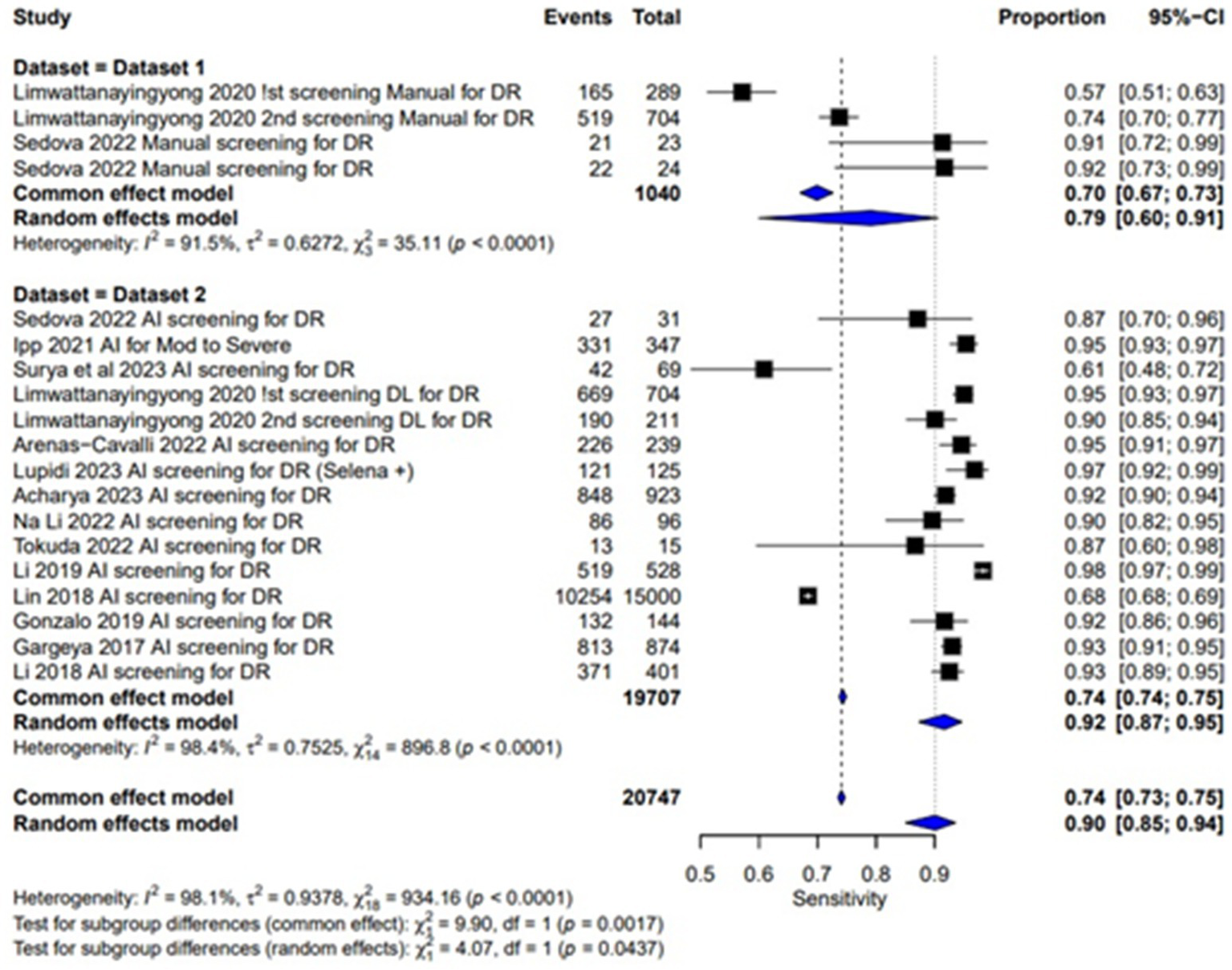

The sensitivity of AI-based screening for dilated eyes show consistent results across the studies with a pooled sensitivity of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.91, 0.97). For manual screening in dilated eyes, the pooled sensitivity reported was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.87, 0.92), showing lower performance than AI as given in Table 2 and Figure 4. For un-dilated eyes, AI screening achieved a pooled sensitivity of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.87, 0.95). In the manual screening of un-dilated eyes images pooled sensitivities of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.60, 0.91) is reported given in Table 2 and Figure 5. AI-based screening shows higher performance than manual screening.

Table 2

| Study | Outcome | Dilated/Un-dilated eye | TP | FP | FP | TN | Sensitivity (CI at 95%) | Specificity (CI at 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piatti et al. 2024 (13) | Mild DR with AI | Dilated | 70 | 102 | 102 | 399 | 0.41 [0.33, 0.48] | 0.93 [0.90, 0.95] |

| Piatti et al. 2024 (13) | Moderate and beyond with AI | Dilated | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 [0.90, 1.00] | Not estimable |

| Sosale et al. 2020 (15) | AI for referable DR | Dilated | 120 | 23 | 23 | 153 | 0.84 [0.77, 0.90] | 0.99 [0.96, 1.00] |

| Sosale et al. 2020 (15) | AI for any DR | Dilated | 105 | 8 | 8 | 168 | 0.93 [0.87, 0.97] | 0.91 [0.86, 0.95] |

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | AI for referable DR | Dilated | 3,057 | 9,172 | 9,172 | 100,097 | 0.25 [0.24, 0.26] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | Moderate and beyond with AI | Dilated | 676 | 9,969 | 9,969 | 102,003 | 0.06 [0.06, 0.07] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Ipp 2021 (10) | AI for Mod and beyond | Dilated | 356 | 375 | 375 | 2,630 | 0.49 [0.45, 0.52] | 0.99 [0.99, 1.00] |

| Soto-Pedre et al. 2015 (18) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 535 | 1,034 | 1,034 | 2,277 | 0.34 [0.32, 0.37] | 0.69 [0.67, 0.70] |

| Wang et al. 2018 (20) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 213 | 205 | 205 | 206 | 0.51 [0.46, 0.56] | 0.50 [0.45, 0.55] |

| Abràmoff et al. 2016 (31) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 182 | 88 | 88 | 598 | 0.67 [0.61, 0.73] | 0.87 [0.84, 0.90] |

| Hansen et al. 2015 (29) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 91 | 900 | 900 | 2,093 | 0.09 [0.07, 0.11] | 0.70 [0.68, 0.72] |

| Rajalakshmi et al. 2018 (19) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 184 | 21 | 21 | 84 | 0.90 [0.85, 0.94] | 0.80 [0.71, 0.87] |

| Kumar et al. 2016 (34) | AI screening for DR | Dilated | 722 | 176 | 176 | 176 | 0.80 [0.78, 0.83] | 0.50 [0.45, 0.55] |

| Zhang et al. 2019 (32) | AI screening for DR (Grading system) | Dilated | 414 | 4 | 4 | 344 | 0.99 [0.98, 1.00] | 0.99 [0.97, 1.00] |

| Zhang et al. 2019 (32) | AI screening for DR (identification system) | Dilated | 412 | 8 | 8 | 340 | 0.98 [0.96, 0.99] | 0.98 [0.96, 0.99] |

| Zhang et al. 2022 (33) | AI screening for DR (InceptionV3_299) | Dilated | 12,440 | 3,580 | 3,580 | 35,953 | 0.78 [0.77, 0.78] | 0.91 [0.91, 0.91] |

| Zhang et al. 2022 (33) | AI screening for DR (InceptionV3_896) | Dilated | 12,984 | 3,676 | 3,676 | 35,857 | 0.78 [0.77, 0.79] | 0.91 [0.90, 0.91] |

| Sedova et al. 2022 (14) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 27 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 0.96 [0.82, 1.00] | 0.80 [0.56, 0.94] |

| Ipp 2021 (10) | AI for Mod to Severe | Undilated | 331 | 345 | 345 | 2,342 | 0.49 [0.45, 0.53] | 0.99 [0.99, 1.00] |

| Surya et al. 2023 (16) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 42 | 10 | 10 | 283 | 0.81 [0.67, 0.90] | 0.91 [0.88, 0.94] |

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | 1st screening DL for DR | Undilated | 669 | 102 | 102 | 4,932 | 0.87 [0.84, 0.89] | 0.99 [0.99, 1.00] |

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | 2nd screening DL for DR | Undilated | 190 | 84 | 84 | 3,853 | 0.69 [0.64, 0.75] | 0.99 [0.99, 1.00] |

| Arenas-Cavalli et al. 2022 (23) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 226 | 227 | 227 | 657 | 0.50 [0.45, 0.55] | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99] |

| Lupidi et al. 2023 (12) | AI screening for DR (Selena +) | Undilated | 121 | 4 | 4 | 122 | 0.97 [0.92, 0.99] | 0.97 [0.92, 0.99] |

| Acharyya et al. 2024 (22) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 848 | 128 | 128 | 732 | 0.87 [0.85, 0.89] | 0.91 [0.88, 0.93] |

| Li et al. 2022 (11) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 86 | 25 | 25 | 1,323 | 0.77 [0.69, 0.85] | 0.99 [0.99, 1.00] |

| Tokuda et al. 2022 (17) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 13 | 5 | 5 | 49 | 0.72 [0.47, 0.90] | 0.96 [0.87, 1.00] |

| Li et al. 2019 (28) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 519 | 16 | 16 | 256 | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99] | 0.94 [0.91, 0.97] |

| Lin et al. 2018 (27) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 10,254 | 1,519 | 1,519 | 13,481 | 0.68 [0.68, 0.69] | 0.90 [0.89, 0.90] |

| González-Gonzalo et al. 2020 (26) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 132 | 30 | 30 | 295 | 0.92 [0.86, 0.96] | 0.91 [0.87, 0.94] |

| Gargeya and Leng 2017 (30) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 813 | 113 | 113 | 761 | 0.93 [0.91, 0.95] | 0.87 [0.85, 0.89] |

| Li et al. 2018 (21) | AI screening for DR | Undilated | 371 | 199 | 199 | 13,057 | 0.93 [0.89, 0.95] | 0.98 [0.98, 0.99] |

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | !st screening Manual for DR | Undilated | 165 | 124 | 59 | 3,915 | 0.74 [0.67, 0.79] | 0.97 [0.96, 0.97] |

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | 2nd screening Manual for DR | Undilated | 519 | 185 | 71 | 4,963 | 0.88 [0.85, 0.90] | 0.96 [0.96, 0.97] |

| Sedova et al. 2022 (14) | Manual screening for DR | Undilated | 21 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 0.95 [0.77, 1.00] | 0.94 [0.80, 0.99] |

| Sedova et al. 2022 (14) | Manual screening for DR | Undilated | 22 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 0.96 [0.78, 1.00] | 0.94 [0.80, 0.99] |

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | Manual for referable DR | Dilated | 3,077 | 302 | 768 | 108,501 | 0.80 [0.79, 0.81] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | Moderate and beyond with Manual | Dilated | 558 | 78 | 447 | 111,525 | 0.56 [0.52, 0.59] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

Results for outcomes.

CI, Confidence Interval; DR, Diabetic Retinopathy; Referable DR, severity grade 2 and above; DL, Deep Learning; DLA, Deep Learning Algorithm; FN, False Negative; FP, False Positive; Mod, Moderate; RDR, Referable Diabetic Retinopathy; SVM, Support Vector Machine; TP, True Positive; TN, True Negative; UWF, Ultra-Wide Field Grading.

Figure 4

Specificity forest plot for un-dilated eyes.

Figure 5

Sensitivity forest plot for un-dilated eyes.

Specificity

Pooled specificity of AI screening for dilated eyes was reported at 0.87 (95% CI: 0.79, 0.92) showing a good performance and manual screening for dilated eyes also showed a high pooled specificity value of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.00). Showing a good performance of both AI-based and manual screening methods as shown in the Figure 6. For un-dilated eyes, AI screening demonstrated pooled specificity of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.91, 0.96). Manual screening similarly showed robust specificity 0.99 (95% CI: 0.98, 0.99) as given in the Figure 7. Showing that AI a comparable alternative to manual screening.

Figure 6

Specificity forest plot for dilated eyes.

Figure 7

Sensitivity forest plot for dilated eyes.

Multi-test analysis

The combined pooled sensitivity and specificity of dilated eye is 0.94 [95% CI: 0.90; 0.97] and 0.91 [0.83; 0.95] with heterogeneity of 95.2 and 99.9% and p value of 0.0386 and 0.0001, respectively, showing comparable results in the outcomes with high variability among studies as shown in Figures 4, 6. Un-dilated eye report combined pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.90 [95% CI: 0.85; 0.94] and 0.95 [0.93; 0.97] with heterogeneity of 98.1 and 99.1% and p value of 0.0437 and 0.0001, respectively, showing results with no statistically significant difference as shown in Figures 5, 7.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was systematically assessed using appropriate tools for the study designs. For the 16 validation studies (13, 16, 18–21, 23, 26–34), the QUADAS-2 tool was used. Thirteen of these studies demonstrated a low risk of bias, while three study shows some concerns particularly in the domain 3 and 4, as shown in the accompanying Figures 8, 9.

Figure 8

Risk of bias assessment traffic light plot for QUADAS-2 tool.

Figure 9

Risk of bias assessment summary plot for QUADAS-2 tool.

For the five cross-sectional studies, the AXIS tool was used to assess the risk of bias (10, 12, 15, 22, 25). The results reported a moderate risk of bias across the studies, with bias related to results and conclusion. These findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Author | Intro | Methods | Results | Conclusions | Other | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ting et al. 2017 (25) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 75% | 50% | Moderate |

| Sosale et al. 2020 (15) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 75% | 0% | Moderate |

| Ipp 2021 (10) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | Moderate |

| Acharyya et al. 2024 (22) | 100% | 90% | 50% | 75% | 0% | Moderate |

| Lupidi et al. 2023 (12) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 75% | 0% | Moderate |

AXIS risk of bias assessment summary-percentages of items satisfied.

AXIS, Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies; %, percentage of the bias.

In the risk of bias assessment of four cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was applied. All four studies demonstrated a low risk of bias, in all domains such as selection, comparability, and outcome assessment (11, 14, 17, 24). These results are detailed in Table 4, supporting the reliability of the included cohort studies.

Table 4

| Study | Adequacy of selection | Comparability | Outcome assessment | Asterisk rating | Overall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representative of the exposed cohorts | Selection of the exposed cohorts | ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that Outcome of Interest was Not Present at Start of Study | Assessment of outcomes | Follow-up period long enough for outcome to occur | Adequacy of follow-up period among cohorts | ||||

| Sedova et al. 2022 (14) | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8.0/9.0 | Low | |

| Tokuda et al. 2022 (17) | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7.0/9.0 | Low | ||

| Li et al. 2022 (11) | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7.0/9.0 | Low | ||

| Limwattanayingyong et al. 2020 (24) | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 7.0/9.0 | Low | ||

Asterisk rating in observational studies according Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) tool.

NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; **Indicates two stars in NOS for comparability domain; *Indicates one star for selection, comparability, or outcome assessment based on NOS guidelines for cohort studies; Adequacy of follow-up period: evaluated based on sufficient follow-up time.

Discussion

The development of artificial intelligence based screening systems has led to potential use as a diagnostic tool in health care system. Evaluating the accuracy of AI in clinical settings is essential to ensure its implementation in clinical settings. Diabetic retinopathy screening is important in preventing vision loss. In this meta-analysis, we assessed the diagnostic accuracy of AI-based systems versus manual screening methods for both dilated and un-dilated eyes, for detecting DR. The aim was to determine whether AI systems could offer a comparable or superior alternative to manual methods in clinical practice.

Our results showed that AI systems demonstrated a high sensitivity across most studies. In comparison sensitivity for both dilated and un-dilated eyes using AI screening shows a good performance and specificity for AI screening and manual screening was generally comparable, with dilated eyes as well as un-dilated eyes.

These results highlight that AI systems, especially in un-dilated eye conditions, show promise for clinical use with reliable sensitivity and specificity, but variations exist depending on the system and clinical setting.

Most of the studies exhibit low risk of bias showing which shows robust methodologies and reliable findings but some validation studies have shown moderate risk of bias especially in index test and reference standards suggesting possible inconsistencies in diagnostic criteria or lack of blinding. Also the studies assessed with axis tool shows moderate risk of bias in all studies especially in the results and conclusion domain indicates potential selective reporting, which could introduce bias in outcome interpretation.

Limitations and implications

Despite the promising outcomes, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, there is considerable heterogeneity across the included studies in terms of study settings, photographic protocols, and reference standards. The studies vary from community-based to outpatient settings, and the imaging techniques range from two-field to five-field photography with or without mydriasis. These differences may have influenced the diagnostic performance of AI based screening, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the reference standards used for manual grading differ across studies, with some having single specialists and others using diagnoses by multiple experts, potentially affecting the accuracy of comparisons. Second, not all studies report the number of participants, making it difficult to assess the true sample size, which could impact diagnostic validity. Third, there is a significant variability among the studies in AI based screening, Variability in AI performance can arise from differences in study methodologies, dataset quality, and model training conditions. The findings highlight the need for standardized evaluation metrics and more transparent reporting to solve inconsistencies. Addressing these issues will enhance the reliability of AI applications in clinical settings and ensure robust decision-making.

Moreover, some of the studies had a moderate risk of bias which could lead to over-estimation or down-estimation of accuracy. To ensure that AI systems are safe and effective for real-world use, evaluations need to be conducted in representative clinical settings. Systems should be tested on a wide range of image qualities, and medical settings.

Conclusion

The findings from this meta-analysis suggest that AI systems are promising for DR screening, especially in settings where high sensitivity is critical. However, further independent studies, particularly those assessing the dilated eyes screening, are required to establish the efficacy of AI in broader clinical practice. Factors such as system technical failures, and operational settings should also be considered before full implementation. In conclusion, while AI-based systems offer a valuable tool for reducing the workload on human graders, their clinical utility depends on continued rigorous evaluation and refinement.

Future research

Future work should focus on refining AI algorithms for dilated eye conditions and exploring the integration of AI screening into routine ophthalmic practice. Large-scale, prospective validation studies will be essential to confirm these findings and guide the adoption of AI in DR screening protocols.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MT: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ID: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. RP: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AA: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ST: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. YA: Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work. This research is supported by the author, there are no sponsors or funds for the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

World Health Organization . Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

2.

Teo ZL Tham YC Yu M Chee ML Rim TH Cheung N et al . Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. (2021) 128:1580–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027

3.

World Health Organization . (2023) Blindness and visual impairment fact sheet. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

4.

Piyasena M Murthy GVS Yip JLY Gilbert C Zuurmond M Peto T et al . Systematic review on barriers and enablers for access to diabetic retinopathy screening services in different income settings. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0198979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198979

5.

Hasan SU Siddiqui MAR . Diagnostic accuracy of smartphone-based artificial intelligence systems for detecting diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2023) 205:110943. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110943

6.

Uy H Fielding C Hohlfeld A Ochodo E Opare A Mukonda E et al . Diagnostic test accuracy of artificial intelligence in screening for referable diabetic retinopathy in real-world settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0002160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002160

7.

Wang S Zhang Y Lei S Zhu H Li J Wang Q et al . Performance of deep neural network-based artificial intelligence method in diabetic retinopathy screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Eur J Endocrinol. (2020) 183:41–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0968

8.

Zhelev Z Peters J Rogers M Allen M Kijauskaite G Seedat F et al . Test accuracy of artificial intelligence-based grading of fundus images in diabetic retinopathy screening: a systematic review. J Med Screen. (2023) 30:97–112. doi: 10.1177/09691413221144382

9.

Tan CH Kyaw BM Smith H Tan CS Tudor Car L . Use of smartphones to detect diabetic retinopathy: scoping review and Meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e16658. doi: 10.2196/16658

10.

Ipp E Liljenquist D Bode B Shah VN Silverstein S Regillo CD et al . Pivotal evaluation of an artificial intelligence system for autonomous detection of referrable and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2134254. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34254

11.

Li N Ma M Lai M Gu L Kang M Wang Z et al . A stratified analysis of a deep learning algorithm in the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy in a real-world study. J Diabetes. (2022) 14:111–20. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13241

12.

Lupidi M Danieli L Fruttini D Nicolai M Lassandro N Chhablani J et al . Artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy screening: clinical assessment using handheld fundus camera in a real-life setting. Acta Diabetol. (2023) 60:1083–8. doi: 10.1007/s00592-023-02104-0

13.

Piatti A Romeo F Manti R Doglio M Tartaglino B Nada E et al . Feasibility and accuracy of the screening for diabetic retinopathy using a fundus camera and an artificial intelligence pre-evaluation application. Acta Diabetol. (2024) 61:63–8. doi: 10.1007/s00592-023-02172-2

14.

Sedova A Hajdu D Datlinger F Steiner I Neschi M Aschauer J et al . Comparison of early diabetic retinopathy staging in asymptomatic patients between autonomous AI-based screening and human-graded ultra-widefield colour fundus images. Eye. (2022) 36:510–6. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01912-4

15.

Sosale B Sosale AR Murthy H Sengupta S Naveenam M . Medios-an offline, smartphone-based artificial intelligence algorithm for the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2020) 68:391–5. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1203_19

16.

Surya J Garima Pandy N Hyungtaek Rim T Lee G Priya MNS et al . Efficacy of deep learning-based artificial intelligence models in screening and referring patients with diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2023) 71:3039–45. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_11_23

17.

Tokuda Y Tabuchi H Nagasawa T Tanabe M Deguchi H Yoshizumi Y et al . Automatic diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy stage focusing exclusively on retinal hemorrhage. Medicina. (2022) 58:1681. doi: 10.3390/medicina58111681

18.

Soto-Pedre E Navea A Millan S Hernaez-Ortega MC Morales J Desco MC et al . Evaluation of automated image analysis software for the detection of diabetic retinopathy to reduce the ophthalmologists' workload. Acta Ophthalmol. (2015) 93:e52–6. doi: 10.1111/aos.12481

19.

Rajalakshmi R Subashini R Anjana RM Mohan V . Automated diabetic retinopathy detection in smartphone-based fundus photography using artificial intelligence. Eye (Lond). (2018) 32:1138–44. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0064-9

20.

Wang K Jayadev C Nittala MG Velaga SB Ramachandra CA Bhaskaranand M et al . Automated detection of diabetic retinopathy lesions on ultrawidefield pseudocolour images. Acta Ophthalmol. (2018) 96:e168–73. doi: 10.1111/aos.13528

21.

Li Z Keel S Liu C He Y Meng W Scheetz J et al . An automated grading system for detection of vision-threatening referable diabetic retinopathy on the basis of color fundus photographs. Diabetes Care. (2018) 41:2509–16. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0147

22.

Acharyya M Moharana B Jain S Tandon M . A double-blinded study for quantifiable assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of AI tool "ADVEN-i" in identifying diseased fundus images including diabetic retinopathy on a retrospective data. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2024) 72:S46–s52. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_3342_22

23.

Arenas-Cavalli JT Abarca I Rojas-Contreras M Bernuy F Donoso R . Clinical validation of an artificial intelligence-based diabetic retinopathy screening tool for a national health system. Eye (Lond). (2022) 36:78–85. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01366-0

24.

Limwattanayingyong J Nganthavee V Seresirikachorn K Singalavanija T Soonthornworasiri N Ruamviboonsuk V et al . Longitudinal screening for diabetic retinopathy in a Nationwide screening program: comparing deep learning and human graders. J Diabetes Res. (2020) 2020:8839376. doi: 10.1155/2020/8839376

25.

Ting DSW Cheung CYL Lim G Tan GSW Quang ND Gan A et al . Development and validation of a deep learning system for diabetic retinopathy and related eye diseases using retinal images from multiethnic populations with diabetes. JAMA. (2017) 318:2211–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18152

26.

González-Gonzalo C Sánchez-Gutiérrez V Hernández-Martínez P Contreras I Lechanteur YT Domanian A et al . Evaluation of a deep learning system for the joint automated detection of diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. (2020) 98:368–77. doi: 10.1111/aos.14306

27.

Lin GM Chen M-J Yeh C-H Lin Y-Y Kuo H-Y Lin M-H et al . Transforming retinal photographs to entropy images in deep learning to improve automated detection for diabetic retinopathy. J Ophthalmol. (2018) 2018:2159702. doi: 10.1155/2018/2159702

28.

Li F Liu Z Chen H Jiang M Zhang X Wu Z . Automatic detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs based on deep learning algorithm. Transl Vis Sci Technol. (2019) 8:4. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.6.4

29.

Hansen MB Abràmoff MD Folk JC Mathenge W Bastawrous A Peto T . Results of automated retinal image analysis for detection of diabetic retinopathy from the Nakuru study, Kenya. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0139148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139148

30.

Gargeya R Leng T . Automated identification of diabetic retinopathy using deep learning. Ophthalmology. (2017) 124:962–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.02.008

31.

Abràmoff MD Lou Y Erginay A Clarida W Amelon R Folk JC et al . Improved automated detection of diabetic retinopathy on a publicly available dataset through integration of deep learning. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2016) 57:5200–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19964

32.

Zhang W Zhong J Yang S Gao Z Hu J Chen Y et al . Automated identification and grading system of diabetic retinopathy using deep neural networks. Knowl-Based Syst. (2019) 175:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.03.016

33.

Zhang X Li F Li D Wei Q Han X Zhang B et al . Automated detection of severe diabetic retinopathy using deep learning method. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2022) 260:849–856. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05402-x

34.

Kumar PS Deepak RU Sathar A Sahasranamam V Rajesh Kumar R . Automated detection system for diabetic retinopathy using two field fundus photography. Procedia Comput Sci. (2016) 93:486–94. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2016.07.237

Summary

Keywords

diabetic retinopathy, screening, artificial intelligence, deep learning, manual screening, automated detection

Citation

Tahir HN, Ullah N, Tahir M, Domnic IS, Prabhakar R, Meerasa SS, AbdElneam AI, Tahir S and Ali Y (2025) Artificial intelligence versus manual screening for the detection of diabetic retinopathy: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1519768. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1519768

Received

07 November 2024

Accepted

14 April 2025

Published

07 May 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Yanwu Xu, Baidu, China

Reviewed by

Xiuju Chen, Xiamen University, China

Rajalakshmi R., Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Tahir, Ullah, Tahir, Domnic, Prabhakar, Meerasa, AbdElneam, Tahir and Ali.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hasan Nawaz Tahir, hasan.nawaz@su.edu.saNaseer Ullah, khannasir965@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.