Abstract

Placental vascularization may influence fetal brain development, but its long-term impact on neurodevelopment remains unclear. In this pilot study, we analyzed two ligand proteins: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PLGF), and their receptors mRNA and protein levels in placentas from children who later were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or controls. ASD placentas showed lower VEGF, PLGF, and KDR protein levels but higher FLT1, while ADHD placentas had increased FLT1 and reduced VEGF mRNA. These findings suggest distinct placental vascular alterations in ASD and ADHD, highlighting a potential role of the placenta-brain axis in neurodevelopmental disorders and early-life mechanisms underlying impaired brain development.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are common neurodevelopmental conditions with complex etiologies. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ASD is characterized by social communication and interaction difficulties, along with repetitive behaviors. At the same time, ADHD presents as persistent inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. Both disorders emerge in early childhood and impact cognitive, social, and emotional development (1).

The reported prevalence of ASD varies across studies and regions. In Chile, the ASD prevalence has been estimated at 1.96% (2021), derived from a cohort of 272 children (2). However, meta-analytic estimates suggest global ASD prevalence in children closer to ∼0.7–1.5%, with substantial heterogeneity across studies and regions (3). Furthermore, global estimations from meta-analyses indicate that ADHD affects approximately 5–8% of children and adolescents, with higher estimates in boys than girls (4, 5), highlighting the need for deeper investigation into prenatal and perinatal contributors.

The etiology of ASD and ADHD involves genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors, with gene-environment interactions playing a significant role. Prenatal risk factors for ASD include advanced parental age, maternal conditions like gestational hypertension and diabetes, and obstetric complications such as preeclampsia and preterm birth (6). ADHD is highly heritable, but environmental exposures during pregnancy can modulate genetic susceptibility (7). The placental function may play a role in the early programming of these disorders (8). For instance, placental insufficiency and maternal vascular malperfusion, indicative of prenatal hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, have been linked to a markedly increased risk of ASD (9, 10). Also, altered placental DNA methylation patterns were associated with ASD susceptibility (11, 12).

The placenta is a key regulator of fetal development, facilitating the exchange of nutrients and gases, and producing bioactive molecules essential for brain development. Angiogenic factors (ligands), such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PLGF), as well as their receptors—type 1 (VEGFR-1, FLT1) and type 2 (VEGFR-2, KDR)—play critical roles in placental vascularization (13). Dysregulation of these pathways has been implicated in pregnancy complications, but their potential contribution to neurodevelopmental disorders remains unclear.

Using our placental biobank, we investigated the expression (mRNA and protein) of VEGF, PLGF, FLT1, and KDR in the placentas of children (10–12 years old) who were diagnosed with ASD or ADHD, compared to age-matched controls. This study provides insights into the prenatal origins of these disorders and highlights potential underlying alterations occurring during pregnancy.

Methods

Patients

Ethical approval and participant recruitment

The Bioethics Committee of the Herminda Martin Hospital in Chillán approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all parents, and the children also provided informed assent to participate. This pilot study utilized a database from the Vascular Physiology Laboratory at the University of Bio Bio, containing clinical data from 617 deliveries and stored placentas (n = 363). Mothers were contacted when their children were 10–12 years old, and a telephone interview was conducted to identify potential participants searching for children with a previous diagnosis of ASD or ADHD.

Clinical and neurological assessment

In-person evaluations were scheduled for children with a reported diagnosis of ASD or ADHD. Before this evaluation, we obtained a written informed consent, and a speech-language pathologist (C. Celis) conducted an initial interview to verify the diagnosis. Children were then referred to a neurologist (Dr. E. López) for diagnostic reconfirmation.

Final sample and data collection

The final sample consisted of 16 children: 4 with ADHD, 4 with ASD, and eight controls without neurocognitive disorders (Non-ND). Controls were matched by gestational age, pregnancy conditions, child sex, newborn anthropometry, and placental weight. Clinical information was stored in a database, and structured questionnaires were used to collect missing pregnancy-related data.

PCR quantitative (qRTPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from placental extracts, and cDNA was synthesized. qRTPCR was performed using specific primers (Supplementary Table 1) for the genes of interest, with gene expression quantified using the 2–Δ/ΔCT method (14).

Western blot

Placental protein extracts (50 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed with primary antibodies anti-VEGF (Santa Cruz, California, OR, USA; sc-7269, 1:1000 dilution), anti-PLGF (Santa Cruz, California, OR, USA; sc-518003, 1:1000), anti-FLT1 (Santa Cruz, California, OR, USA; sc-316, 1:1000), and anti- KDR (Cell Signaling Technology, Denver, MA, USA; 2472, 1:1000 dilution). They were applied overnight independently, followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies Anti-Rabbit IgG (sc-A9169) or Anti-Mouse IgG (sc-A9917) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Proteins were normalized with β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, California, OR, USA; A5441, 1:5000 dilution). The bands were quantified using ImageJ software as previously described (15).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± SD, and qualitative variables as percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, with Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were organized in a Microsoft Excel database, and statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism.

Results

Participant selection and group characteristics

Of the 617 potential participants, only 363 had placenta samples in our database. From then, 212 mothers were contacted, and 24 agreed to participate (Supplementary Figure 1). The final sample included in this pilot study consists of four placentas and children with ADHD, four with ASD, and eight with non-neurocognitive disorders (Non-ND) (Figure 1A). The age range at inclusion was 10–12 years, with no significant differences among groups. A Kruskal–Wallis test indicated significant differences among groups in mothers’ age [H(2) = 8.53, p = 0.0053, n = 16]. Post hoc Dunn’s test showed a significant difference in the age of mothers of children with ADHD compared to those of the Non-ND group (Z = 2.92, p = 0.0106). No significant differences were observed in gestational age, newborn anthropometry, or placental weight (Table 1).

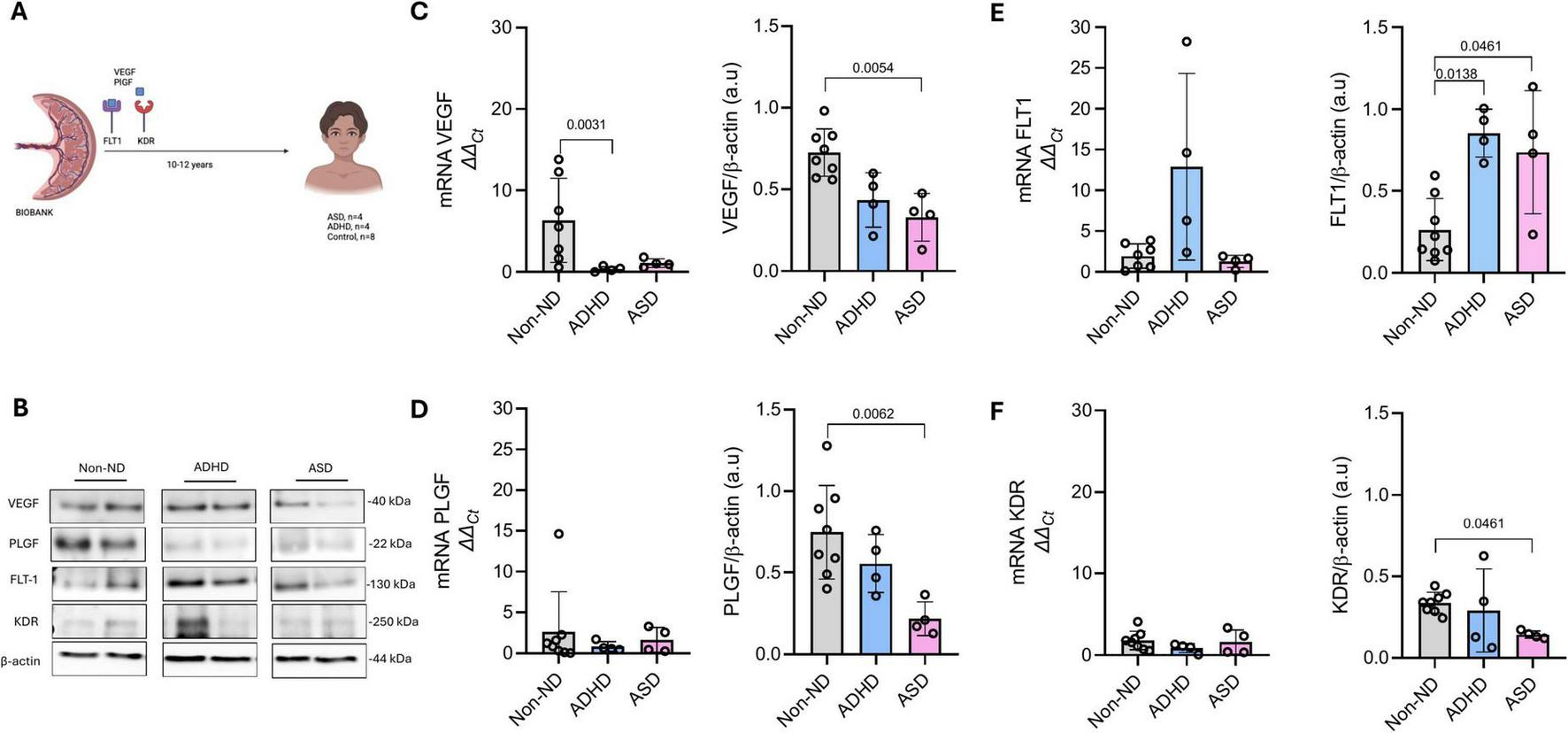

FIGURE 1

Placental expression of VEGF, PLGF, FLT1, and KDR in children later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or controls (Non-ND). (A) Schematic representation of the study design, analyzing placental samples stored in our biobank for 10–12 years. Figure A created with Biorender. (B) Representative blots of VEGF, PLGF, FLT1, KDR, and β-actin. Protein and mRNA expression of (C) VEGF, (D) PLGF, (E) FLT1, and (F) KDR. Every dot represents an individual subject. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P-values are included in each graph.

TABLE 1

| Analyzed characteristic | Non-ND | ADHD | ASD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.753 |

| Children’s age (years) | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 12.5 ± 0.5 | 12.7 ± 0.5 | |

| Maternal age at pregnancy (years) | 33.8 ± 5.8 | 19.25 ± 3.3* | 30.25 ± 7.4 | 0.0053 |

| Primipara (n, %) | 2 (25) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.3 ± 1.2 | 36.3 ± 4.6 | 38.3 ± 0.9 | 0.697 |

| Pregnancy complications (n, %) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | – |

| Cesarean section (n, %) | 4 (50) | 1 (25) | 4 (100) | – |

| Newborn sex (male/female) | 5/3 | 2/2 | 1/3 | – |

| Weight (gr) | 3537 ± 642.3 | 2535 ± 744.0 | 3793 ± 798.2 | 0.055 |

| Size (cm) | 49.4 ± 1.6 | 45.0 ± 4.8 | 48.5 ± 4.0 | 0.109 |

| Placental weight (gr) | 517.5 ± 90.4 | 495 ± 137 | 580 ± 181 | 0.496 |

| Placental efficiency (gr/gr) | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.01* | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.006 |

Characteristics of the included children.

Non-ND, non-neurocognitive disorders. Any pregnancy complications, including podalic presentation, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and preterm delivery.

*p < 0.05 versus Non-ND. Bold represents statistical differences. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dun’s multiple comparisons test.

Placental efficiency was calculated (grams of fetal mass per gram of placental mass), a widely used measure of how much fetal mass is produced per gram of placental mass. This ratio had shown variations associated with pregnancy outcomes (16). We found that placental efficiency was significantly different among the studied groups [H(2) = 8.49, p = 0.0061], with higher values in the ADHD group than in the Non-ND group (Z = 2.79, p = 0.016).

Pregnancy complications tended to be more frequent among mothers of children with ADHD (3/4) and ASD (4/4) compared to those of children in the Non-ND group (5/8). Among these complications, preeclampsia was reported in 2/4 ADHD cases, 3/4 ASD cases, and 2/8 in the Non-ND group. Additionally, gestational diabetes was observed in two mothers from the Non-ND group and one from the ASD group. Only one case of preterm delivery was reported, occurring in the ADHD group.

Placental protein and gene expression analysis

Figure 1B shows representative blots of analyzed proteins. A Kruskal–Wallis test indicated significant differences among groups in the placental protein levels of VEGF [H(2) = 10.48, p = 0.0006]; PLGF [H(2) = 8.75, p = 0.0038]; FLT1 [H(2) = 9.41, p = 0.0019]; and KDR [H(2) = 5.22, p = 0.050]. Placentas from children with ASD exhibited significantly lower protein levels of VEGF (Figure 1C, Z = 3.00, p = 0.0054), PLGF (Figure 1D, Z = 2.96, p = 0.0062), and KDR (Figure 1F, Z = 2.27, p = 0.046) compared to children in the Non-ND group. These reductions were not reflected at the mRNA level. Conversely, compared to children in the Non-ND group, FLT1 protein levels were significantly higher in the ASD group (Figure 1E, Z = 2.27, p = 0.046) despite no differences in FLT1 mRNA expression.

Placentas of children with ADHD showed significantly lower VEGF mRNA levels (Figure 1C, Z = 2.95, p = 0.0031) and elevated FLT1 protein levels (Figure 1F, Z = 2.70, p = 0.013) compared to children in the Non-ND group. No significant differences were observed in VEGF, PLGF, or KDR protein levels.

There were no statistically significant differences in any of the analyzed markers between the ASD and ADHD groups.

Discussion

The results indicate that ASD is associated with a deficiency in angiogenic agonists (VEGF and PLGF) and their receptor, KDR, as well as an increase in FLT1 in the placenta. ADHD placentas exhibit a distinct angiogenic imbalance with elevated FLT1 protein level. These findings suggest potential early-life placental vascular disruptions that may contribute to the intrauterine initiation of altered neurodevelopmental trajectories.

A growing body of evidence supports the role of the placenta in brain development and the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders (8, 9, 17). Studies have linked placental abnormalities to an increased risk of ASD and ADHD (11, 12, 18). For instance, preeclampsia, a condition characterized by impaired placental vascularization (15), has been associated with an increased risk of ASD and developmental delay (19). For ADHD, placental stress responses and angiogenic imbalances may also contribute to its pathogenesis (20). Compatible with this finding, placentas in the ADHD group showed an increase in insufficiency compared with the control group. Moreover, epidemiologic studies suggest an increased risk of neurodevelopmental diagnoses after abruption of the placenta, though specificity for ASD was not directly analyzed (21).

Placental insufficiency and maternal vascular malperfusion have been observed in ASD cases, suggesting that prenatal hypoxia and nutrient deprivation may contribute to altered brain development (9, 10). For instance, medical record analysis showed that acute signs of vascular placental alterations (chronic uteroplacental vasculitis or maternal vascular malperfusion) were highly associated with risk of ASD (7 to 12-fold higher risk) (9). Placental trophoblast inclusions, a marker of altered placental development, have been reported at significantly higher rates in ASD cases than in controls, suggesting that structural abnormalities in the placenta may be early indicators of neurodevelopmental risk (22, 23). Additionally, epigenetic modifications in the placenta, including DNA methylation changes at key neurodevelopmental genes, have been identified in ASD cases, further supporting the placenta’s role in fetal brain programming (11, 12). These observations are consistent with the possibility that acute placental injury or chronic placental dysfunction might perturb angiogenic signaling and fetal neurovascular development, but prospective mechanistic evidence is lacking.

Our findings align with this literature, as reduced levels of critical proangiogenic proteins (such as VEGF and PLGF) in ASD placentas may indicate compromised placental vascularization, potentially leading to fetal brain hypoxia, which in turn may have long-lasting consequences. Future studies that include CD31 immunohistochemistry and stereological/morphometric analysis are required to determine whether vessel density or architecture is altered in these placentas and how these alterations may predispose to structural/functional changes.

In this regard, our findings of lower VEGF/PLGF and KDR protein with higher FLT1 in ASD placentas (and increased FLT1 in ADHD placentas) are consistent with preclinical evidence linking placental angiogenic signaling to fetal brain vascular development. For example, Lecuyer et al. showed that prenatal alcohol exposure impaired placental angiogenesis, reduced PLGF levels, and altered fetal brain vasculature. Interestingly, placental repression of PLGF altered brain FLT1 expression and mimicked alcohol-induced vascular defects in the cortex. At the same time, overexpression of placental PLGF rescued alcohol effects on fetal brain vessels. Translational evidence in humans showed that alcohol exposure disrupted both placental and brain angiogenesis (24). Supporting this idea, another report showed that repression of placental CD146, a co-receptor of KDR, led to reduced cortical vessel density and oligodendrocyte loss (25). Moreover, placental Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1) has been shown to induce persistent neurodevelopmental changes in striatal development (26). These preclinical studies provide mechanistic support for a placenta: brain axis by which altered placental angiogenic signaling may affect fetal neurovascular development and, potentially, later cognitive outcomes. Despite that, we acknowledge that our human data are exploratory and do not demonstrate causality.

Considering embryonic development, Manzo et al. (27) emphasize the importance of neural tube vascular events occurring during early embryogenesis. We note that analyses of term placentas provide a window into cumulative or persistent placental changes but cannot directly demonstrate that the specific angiogenic disruptions we measured were present during neural tube closure. Term placental measures may function as surrogate or residual markers of earlier placental dysfunction, but prospective sampling in early pregnancy is required to test temporality and causality.

The pattern of elevated FLT1 with reduced VEGF and PlGF could create a functionally anti-angiogenic environment by sequestering free ligand, analogous to mechanisms implicated in preeclampsia (28). Alternatively, FLT1 upregulation might reflect an adaptive placental response to chronic stressors (hypoxia or inflammation). Our current data (term placenta protein quantification) cannot distinguish these possibilities. We encourage future work to enhance our understanding of how this imbalance between ligands (VEGF/PLGF) and the FLT1 receptor may drive placental vascular alterations that may impair brain vascular function.

We acknowledge that this is a small, exploratory pilot study, for which analyses are underpowered for sex-stratified comparisons and covariate adjustment. These results should therefore be considered hypothesis-generating. Nevertheless, the study used precious placental samples stored for over a decade, providing a rare opportunity to analyze long-term biological markers. The retrospective nature of the study limits causal inference, and future prospective studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate these findings. Despite that, by integrating protein and mRNA analyses, we identified differential regulatory patterns in placentas from individuals with ASD and ADHD, providing novel insights into early-life vascular alterations that may influence neurodevelopment. Additionally, our findings contribute to the growing field of the placenta-brain vascular axis (17).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights distinct placental angiogenic profiles in ASD and ADHD, suggesting that early-life vascular imbalances may contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders. Further studies are needed to confirm these associations and explore potential interventions to improve placental vascular health.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Bioethics Committee of the Herminda Martin Hospital in Chillán. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EL: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EE-G: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Fondecyt 1240295 and UBB-VRIP GI2301146 (Chile).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the GRIVAS Health, NEUROVAS, and RIVATREM researchers for their valuable support in networking.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1693975/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

American Psychiatric Association [APA]. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2022).

2.

Yáñez C Maira P Elgueta C Brito M Crockett MA Troncoso L et al [Prevalence estimation of Autism Spectrum disorders in chilean urban population]. Andes Pediatr. (2021) 92:519–25. 10.32641/andespediatr.v92i4.2503

3.

Singh J Ahmed A Girardi G . Role of complement component C1q in the onset of preeclampsia in mice.Hypertension. (2011) 58:716–24. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175919

4.

Ayano G Demelash S Gizachew Y Tsegay L Alati R . The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: an umbrella review of meta-analyses.J Affect Disord. (2023) 339:860–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.071

5.

Salari N Ghasemi H Abdoli N Rahmani A Shiri MH Hashemian AH et al The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. (2023) 49:48. 10.1186/s13052-023-01456-1

6.

Wang C Geng H Liu W Zhang G . Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors associated with autism: a meta-analysis.Medicine. (2017) 96:e6696. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006696

7.

Kian N Samieefar N Rezaei N . Prenatal risk factors and genetic causes of ADHD in children.World J Pediatr. (2022) 18:308–19. 10.1007/s12519-022-00524-6

8.

Kratimenos P Penn AA . Placental programming of neuropsychiatric disease.Pediatr Res. (2019) 86:157–64. 10.1038/s41390-019-0405-9

9.

Straughen JK Misra DP Divine G Shah R Perez G VanHorn S et al The association between placental histopathology and autism spectrum disorder. Placenta. (2017) 57:183–8. 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.07.006

10.

Mir IN White SP Steven Brown L Heyne R Rosenfeld CR Chalak LF . Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm infants and placental pathology findings: a matched case-control study.Pediatr Res. (2021) 89:1825–31. 10.1038/s41390-020-01160-4

11.

Schroeder DI Schmidt RJ Crary-Dooley FK Walker CK Ozonoff S Tancredi DJ et al Placental methylome analysis from a prospective autism study. Mol Autism. (2016) 7:51. 10.1186/s13229-016-0114-8

12.

Zhu Y Gomez JA Laufer BI Mordaunt CE Mouat JS Soto DC et al Placental methylome reveals a 22q13.33 brain regulatory gene locus associated with autism. Genome Biol. (2022) 23:46. 10.1186/s13059-022-02613-1

13.

Huang Z Huang S Song T Yin Y Tan C . Placental angiogenesis in mammals: a review of the regulatory effects of signaling pathways and functional nutrients.Adv Nutr. (2021) 12:2415–34. 10.1093/advances/nmab070

14.

Schmittgen TD Livak KJ . Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method.Nat Protoc. (2008) 3:1101–8. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73

15.

Escudero C Celis C Saez T San Martin S Valenzuela FJ Aguayo C et al Increased placental angiogenesis in late and early onset pre-eclampsia is associated with differential activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Placenta. (2014) 35:207–15. 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.01.007

16.

Fowden AL Sferruzzi-Perri AN Coan PM Constancia M Burton GJ . Placental efficiency and adaptation: endocrine regulation.J Physiol. (2009) 587(Pt 14):3459–72. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173013

17.

Gardella B Dominoni M Scatigno AL Cesari S Fiandrino G Orcesi S et al What is known about neuroplacentology in fetal growth restriction and in preterm infants: a narrative review of literature. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:936171. 10.3389/fendo.2022.936171

18.

Gumusoglu SB Chilukuri ASS Santillan DA Santillan MK Stevens HE . Neurodevelopmental outcomes of prenatal preeclampsia exposure.Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:253–68. 10.1016/j.tins.2020.02.003

19.

Walker CK Krakowiak P Baker A Hansen RL Ozonoff S Hertz-Picciotto I . Preeclampsia, placental insufficiency, and autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay.JAMA Pediatr. (2015) 169:154–62. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2645

20.

Bronson SL Bale TL . The placenta as a mediator of stress effects on neurodevelopmental reprogramming.Neuropsychopharmacology. (2016) 41):207–18. 10.1038/npp.2015.231

21.

Oltean I Rajaram A Tang K MacPherson J Hondonga T Rishi A et al The association of placental abruption and pediatric neurological outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2022) 12:205. 10.3390/jcm12010205

22.

Anderson GM Jacobs-Stannard A Chawarska K Volkmar FR Kliman HJ . Placental trophoblast inclusions in autism spectrum disorder.Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 61:487–91. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.068

23.

Walker CK Anderson KW Milano KM Ye S Tancredi DJ Pessah IN et al Trophoblast inclusions are significantly increased in the placentas of children in families at risk for autism. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 74:204–11. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.006

24.

Lecuyer M Laquerrière A Bekri S Lesueur C Ramdani Y Jégou S et al PLGF, a placental marker of fetal brain defects after in utero alcohol exposure. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2017) 5:44. 10.1186/s40478-017-0444-6

25.

Sautreuil C Lecointre M Dalmasso J Lebon A Leuillier M Janin F et al Expression of placental CD146 is dysregulated by prenatal alcohol exposure and contributes in cortical vasculature development and positioning of vessel-associated oligodendrocytes. Front Cell Neurosci. (2024) 17:1294746. 10.3389/fncel.2023.1294746

26.

Carver AJ Fairbairn FM Taylor RJ Boggarapu S Kamau NR Gajmer A et al Placental Igf1 overexpression sex-specifically impacts mouse placenta structure, altering offspring striatal development and behavior. Exp Neurol. (2025) 394:115453. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2025.115453

27.

Manzo J Hernández-Aguilar ME Toledo-Cárdenas MR Herrera-Covarrubias D Coria-Avila GA . Dysregulation of neural tube vascular development as an aetiological factor in autism spectrum disorder: insights from valproic acid exposure.J Physiol. (2025) [Online ahead of print]. 10.1113/JP286899

28.

Phipps EA Thadhani R Benzing T Karumanchi SA . Pre-eclampsia: pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies.Nat Rev Nephrol. (2019) 15:275–89. 10.1038/s41581-019-0119-6

Summary

Keywords

placenta, VEGF family, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, angiogenesis

Citation

Celis C, Troncoso F, López E, Escudero-Guevara E, Acurio J and Escudero C (2025) Dysregulated levels of proangiogenic proteins in the placentas of children with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front. Med. 12:1693975. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1693975

Received

27 August 2025

Accepted

29 October 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Beatrice Paradiso, University of Milan, Italy

Reviewed by

Bruno J. Gonzalez, Normandie Université, France

Genaro Alfonso Coria-Avila, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Celis, Troncoso, López, Escudero-Guevara, Acurio and Escudero.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlos Escudero, cescudero@ubiobio.cl

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

ORCID: Carlos Escudero, orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-4621

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.