Abstract

Background:

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a common condition in rheumatology that affects patients' physical and mental health. Some studies have demonstrated the efficacy of acupuncture in alleviating pain in patients with FMS, but there is still insufficient evidence to support the improvement of pain and associated symptoms in FMS patients through acupuncture. Therefore, this study investigates whether acupuncture has therapeutic effects on patients with FMS.

Methods:

We searched 8 databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating acupuncture interventions for FMS. We used ROB 2.0 tool to assess the risk of bias in selected studies. Heterogeneity among the studies was detected using the I2 test. Identifying sources of heterogeneity using subgroup analysis. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the stability of the results. Meta-analysis was performed using Stata 15.1.

Results:

17 RCTs involving 1,066 patients were included. Meta-analysis results showed that the intervention group had significantly lower VAS scores (SMD: −0.77; 95% CI: −1.00, −0.55), FIQ scores (SMD: −0.98; 95% CI: −1.43, −0.53), and the number of pain points (SMD: −1.36; 95% CI: −1.65, −1.08). It also improved depression and fatigue (SMD: −0.78; 95% CI: −1.10, −0.47) and fatigue (SMD: −0.51; 95% CI: −0.72, −0.30), P < 0.05, but did not significantly improve sleep quality (P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Acupuncture can reduce pain, improve depression and fatigue, and overall lower FIQ scores in the treatment of FMS. These findings require further confirmation through larger-scale, high-quality studies.

Systematic review registration:

Identifier CRD20251120515

1 Introduction

FMS is a syndrome characterized by chronic generalized skeletal muscle pain (1). According to the revised diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 2016, the pain associated with FMS must meet systemic criteria: persistent pain in at least four of the five regions (limbs and axial region), with the pain often being diffuse in nature, and symptoms persisting for more than 3 months (2). In addition to pain, FMS is associated with a cluster of characteristic symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and anxiety or depression (3, 4). FMS is the third most common musculoskeletal disorder in terms of prevalence, following low back pain and osteoarthritis. Its prevalence increases with age, peaking among individuals aged 50–60. Individuals with FMS require nearly twice as many annual medical visits as healthy individuals, and their overall healthcare costs are estimated to be three times higher than those of the general population (5).

Currently, pharmacological treatment for FMS primarily targets symptom control, such as pain, using conventional analgesics like pregabalin, duloxetine, tramadol, and amitriptyline. However, pharmacological treatment has limitations, with only 30–50% of patients responding to medication, and pain relief often less than 50% (6); Etoricoxib did not show superiority over placebo in randomized controlled trials. Additionally, there are significant drug side effects, such as dizziness and weight gain from pregabalin, and nausea, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction from duloxetine (7). Given the limitations of drug efficacy and side effects, there is a need to explore non-pharmacological therapies to reduce drug usage and potentially replace drug therapy to some extent.

Acupuncture, as one of the non-pharmacological therapies for FMS, is recommended for treating FMS patients with pain as the primary symptom (8). Studies suggest that acupuncture may improve central sensitization by increasing serum neuropeptide Y levels, thereby reducing pain in fibromyalgia (9). Electroacupuncture can downregulate inflammatory factors such as interleukin-1, TNF-α, interferon-γ in mouse plasma, as well as inhibit the vanilloid subtype 1 channel of the transient receptor potential family, thereby alleviating pain in FMS patients (10, 11). Currently, there is still a lack of multicenter, large sample RCTs, and there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that acupuncture improves pain and associated symptoms in FMS patients.

Therefore, this study employs systematic reviews and meta-analysis to verify whether acupuncture can effectively alleviate symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, thereby providing scientific evidence for clinical application.

2 Methods

This study was a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature, and have been registered in the PROSPERO Registry (CRD420251120515). This study was conducted in accordance with Cochrane recommendations and follows the PRISMA guidelines (12).

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.1.1 Study type

RCTs.

2.1.2 Study population

Patients diagnosed with FMS, regardless of disease duration, occupation, age, nationality, etc.

2.1.3 Intervention measures

The intervention group used acupuncture and the control group used conventional pain medications (tramadol hydrochloride sustained-release tablets, amitriptyline, pregabalin, and ibuprofen), sham acupuncture, or no intervention.

2.1.4 Outcome measures

Primary outcomes: (1) VAS (13–25): patients marked their subjective pain level on a 10-centimeter linear scale, and physicians measured the marked point to obtain the pain score; (2) Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (13–15, 17–19, 23, 26–28): a self-assessment questionnaire designed to evaluate the extent to which FMS impacts an individual's daily life. The questionnaire consists of ten questions, with a maximum score of 100 points. A higher score indicates a more significant impact; (3) Number of pain points (13, 22, 24, 25, 27): number of pain points at pressure below 4 kg/cm2; Secondary outcomes: (4) Depression (13–16, 18, 20, 21, 25, 27): different depression scales were used to assess the severity of depression in FMS patients, with higher scores indicating more severe depression; (5) Sleep (16, 20, 21, 23, 27, 28): sleep quality in FMS patients were assessed using various sleep scoring scales, with higher scores indicating more severe insomnia; (6) Fatigue (14–16, 18, 27–29): fatigue levels in FMS patients were assessed using various fatigue rating scales, with higher scores indicating more pronounced fatigue.

2.1.5 Exclusion criteria

(1) Studies not related to FMS; (2) Reviews and conferences; (3) Duplicate studies or studies with identical data; (4) Studies that cannot be analyzed without original data; (5) Studies not in Chinese or English.

2.1.6 Research question

Is acupuncture more effective than conventional pain medications, sham acupuncture, or no intervention for pain, overall function, depression, fatigue, and sleep in patients with FMS?

2.2 Literature search

Computerized databases including Web of Science, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, CBM, VIP, and WanFang were searched using a combination of subject terms and free-text keywords, with adjustments made according to the characteristics of each database. Search terms included: “fibromyalgia,” “fibromyalgia syndrome,” “acupuncture,” and “acupuncture therapy,” among others. The search time range spans from the establishment date of each database to July 2025.

2.3 Literature screening and data extraction

Two researchers independently screened the literature, extracted the data and cross-checked them. If there is a disagreement, it shall be settled through discussion or consultation with a third party. During literature screening, duplicate documents were first excluded. Then, the titles were read, and documents clearly unrelated to the study were excluded. Subsequently, the abstracts were read, and finally, the full texts were reviewed to determine inclusion. Data extraction included: (1) study authors and publication year; (2) sample size; (3) age; (4) treatment duration; (5) intervention measures; (6) outcome measures.

When raw data is unavailable or data is presented in graphical form, attempts will be made to contact the relevant authors to obtain the raw data, and GetData Graph Digitizer 2.26 will be used to extract data from the graphs.

2.4 Risk of bias

The Cochrane ROB tool 2.0 (30) was used to assess the risk of bias. Evaluation results were categorized as “low risk,” “unclear,” or “high risk.” The methodological quality was evaluated independently by two evaluators. If there was a disagreement, the agreement was reached according to the third party's opinion.

2.5 Quality assessment

Used GRADEpro GDT web application (https://www.gradepro.org) (31) to assess the quality of evidence for outcomes. The quality of evidence for outcomes was assessed based on the GRADE guidelines (gradeworkinggroup.org). The overall evidence for each outcome measure. GRADE downgrades evidence quality based on five factors: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations. Risk of bias: included studies exhibit methodological limitations (e.g., inadequate randomization, allocation concealment, or blinding). Inconsistency: results across studies show substantial variation without plausible explanation. Imprecision: the 95% confidence interval for the effect size is excessively wide, or the total sample size is too small. Indirectness: evidence is not directly relevant to the clinical question in terms of PICO. Other considerations: overestimation of pooled results due to non-publication of studies with negative or ineffective outcomes. This process is conducted independently by two assessors, with consensus reached through discussion or third-party consultation.

2.6 Statistical analysis

State 15.1 was used for meta-analysis. All data in this study were continuous variables. Due to inconsistencies in units and observation times among the indicators, different scales are used for some indicators (depression, sleep, fatigue), standardized mean differences (SMD) were used to represent the results, with confidence intervals (CI) set at 95%. Heterogeneity was detected by I2 test results. The I2 statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation attributable to between-study variation rather than sampling error. Its formula is: I2 = max (0%, [(Q – df )/Q] × 100%), where Q is the heterogeneity chi-square statistic and df is the degrees of freedom. When I2 ≤ 50%, a fixed-effects model (FEM) based on the inverse variance method was employed, when I2 > 50%, a random-effects model (REM) based on the DerSimonian– (58). Subgroup meta-analysis was used to find the source of heterogeneity, and sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis results. To quantitatively explore potential sources of study heterogeneity, we conducted meta-regression analysis for indicators exhibiting high heterogeneity with more than 10 included studies. Additionally, when the number of studies on an outcome exceeds 10, the funnel plot and Egger's analysis were used to detect publication bias of that outcome measure.

3 Results

3.1 Search result

We preliminarily retrieved 2,248 studies from databases. We summarized the retrieved studies, excluded 566 duplicate studies, and first screened them by reading the titles and abstract, then removed non-FMS, non-RCTs, non-acupuncture studies, and reviews. Next, by reading the full text, we excluded 1 study where the experimental group used other acupuncture methods; seven studies lacking useful data; and 1 study where the control group used other intervention measures. Finally, this study included 17 studies (13–29) for a meta-analysis (Figure 1). The intervention group received acupuncture, while the control group received conventional pain medication, sham acupuncture, or no intervention. The treatment course is 2–12 weeks, mainly concentrated at 4 weeks (Table 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA statement flow chart.

Table 1

| Study | Sample size (T/C) | Age (y), Mean ±SD | Interventions | Frequency | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | |||||

| (13) | 24/25 | 34.71 ± 6.09/34.20 ± 6.84 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Twice a week, 8 times in total | ①②③④ |

| (14) | 25/24 | / | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 20 min, twice a week, 6 times in total | ①②④⑥ |

| (15) | 25/25 | 47.28 ± 7.86/43.60 ± 8.18 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 30 min, 3 treatments in the first week, twice a week for 2 weeks, then once a week for 5 weeks, 12 times in total | ⑥ |

| (29) | 22/15 | 46 ± 10.1/48.1 ± 10.9 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 20 min, once a week for 3 weeks, twice a week for 3 weeks, three times a week for 3 weeks, for a total of 18 times. | ①④⑤⑥ |

| (16) | 25/25 | / | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Twice a week, 24 times in total | ①② |

| (17) | 80/82 | 52.3 ± 9.6/53.2 ± 9.6 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Once a week for 9 weeks | ①②④⑥ |

| (18) | 34/33 | 56.15 ± 7.9/54.39 ± 8.2 | Acupuncture | No intervention | 30 min, twice a week for 5 weeks | ①② |

| (19) | 26/25 | 45.5 ± 7.5/44.2 ± 6.8 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Twice a week for 5 weeks | ② |

| (18) | 34/33 | 56.15 ± 7.9/54.39 ± 8.2 | Acupuncture | No intervention | 30 min, twice a week for 5 weeks | ②③④⑤⑥ |

| (27) | 15/15 | 43.86 ± 7.9/44.2 ± 10.8 | Acupuncture | Fluoxetine | 30 min, three times a week for 2 weeks | ②⑤⑥ |

| (28) | 40/43 | 42.35 ± 6.86/45.52 ± 7.43 | Acupuncture | Tramadol+ Amitriptyline | 20 min, three times a week for 4 weeks | ①④⑤ |

| (20) | 30/30 | 35 ± 8/34 ± 6 | Acupuncture | Amitriptyline | 30 min, once a day for 2 weeks; three times a week for 2 weeks; twice a week for 8 weeks | ①③ |

| (21) | 41/41 | 42 ± 10/43 ± 10 | Acupuncture | Prelamine | 30 min, once a day for 4 weeks | ①②⑤ |

| (22) | 19/19 | 50 ± 2.9/49 ± 3.4 | Acupuncture | Amitriptyline | 30 min, once a day for 4 weeks | ①③ |

| (23) | 42/39 | / | Acupuncture | Amitriptyline | 30 min, three times a week for 12 weeks | ①③④ |

| (24) | 30/30 | / | Acupuncture | Ibuprofen | 6 min, once a day for 2 weeks | ①③ |

| (25) | 25/25 | 43.3 ± 3.6/42.3 ± 4.2 | Acupuncture | Amitriptyline | 30 min, three times a week for 6 weeks | ①③④ |

Basic information of the studies.

VAS; FIQ; Number of pain points; Depression; Sleep; Fatigue.

3.2 Risk of bias

The random number table method was properly implemented in 8 studies (15–19, 26, 27, 29), the method of randomization was not reported in the remaining ones. Six studies (15–18, 26, 27, 29) employed appropriate allocation concealment methods; whereas, the methodology for concealment was omitted in the remaining studies. Five studies (13, 14, 16, 17, 29) implemented blinding for both patients and operators, 1 study (19) did not mention blinding, and the remaining studies did not implement blinding. In the evaluation of outcome measures, 8 studies (13, 14, 16–18, 26, 27, 29) used appropriate blinding methods, 1 study (15) mentioned that blinding was not used, the remaining studies did not state whether blinding was implemented. All studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for selective reporting, as they provided complete outcome reporting (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2

Risk of bias.

3.3 Meta-analysis

3.3.1 VAS

A total of 13 studies (13, 15–25) involving 849 patients were included. Heterogeneity testing revealed I2 = 59.3%, indicating moderate heterogeneity, and a REM was used for analysis. Meta-analysis showed that after acupuncture treatment, the VAS in the intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group (SMD: −0.77; 95% CI: −1.00, −0.55), τ2 = 0.0994, with statistical significance (P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Meta-analysis of VAS.

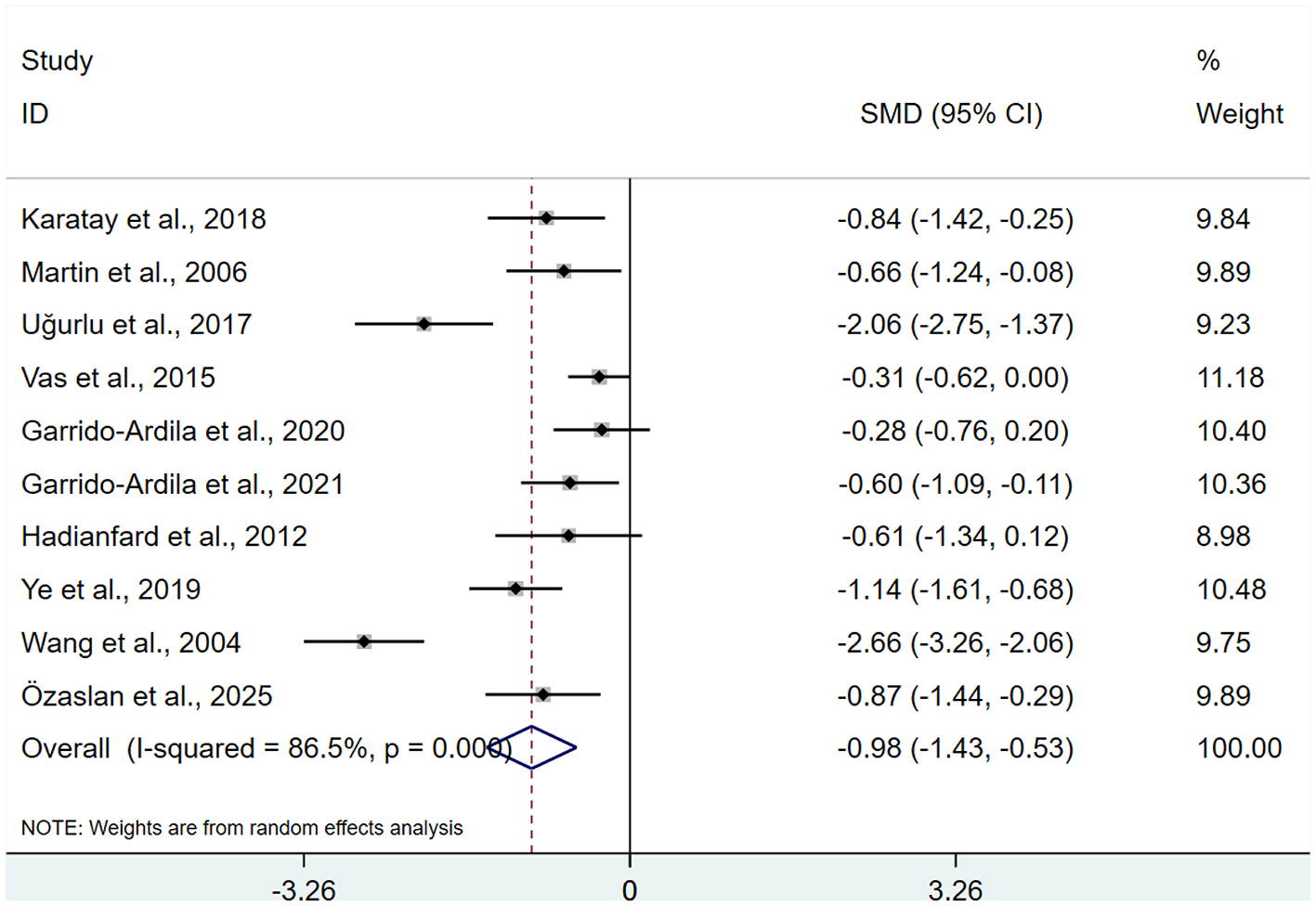

3.3.2 FIQ

A total of 10 studies (13–15, 17–19, 23, 26–28), involving 689 patients. Heterogeneity testing revealed I2 = 86.5%, indicating the presence of heterogeneity, and a REM was used for analysis. Results of the meta-analysis indicated that FMS patients receiving acupuncture exhibited significantly lower FIQ than control group (SMD: −0.98; 95% CI: −1.43, −0.53), τ2 = 0.4444, with statistical significance (P < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4

Meta-analysis of FIQ.

3.3.3 Number of pain points

A total of 5 studies (13, 22, 24, 25, 27) were included, involving 237 patients regarding the number of pain points. Heterogeneity testing showed I2 = 37.5%, and a FEM was used for analysis. Results of the meta-analysis indicated a significant decrease in pain points among FMS patients receiving acupuncture relative to control group (SMD: −1.36; 95% CI: −1.65, −1.08), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5

Meta-analysis of number of pain points.

3.3.4 Depression

A total of 9 studies (13–16, 18, 20, 21, 25, 27) were included, involving 487 patients with depression. Heterogeneity testing revealed I2 = 64.4%, indicating moderate heterogeneity. Analyses were performed using a REM. The results indicated that the intervention group achieved a superior improvement in depression relative to the control group after acupuncture intervention (SMD: −0.78; 95%Cl: −1.10, −0.47), τ2 = 0.1484, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05; Figure 6).

Figure 6

Meta-analysis of depressions.

3.3.5 Sleep

There were 6 studies (16, 20, 21, 23, 27, 28) involving 386 patients related to sleep. Heterogeneity testing showed I2 = 90.1%, indicating heterogeneity, so a REM was used for analysis. Meta-analysis showed that after acupuncture treatment, there was no statistically significant difference in sleep between the intervention group and the control group (SMD: −0.34; 95% CI: −1.01, 0.33), τ2 = 0.6293 (P > 0.05; Figure 7).

Figure 7

Meta-analysis of sleep.

3.3.6 Fatigue

A total of 7 studies (14–16, 18, 27–29) were identified, involving 366 patients with fatigue. Heterogeneity testing revealed I2 = 8.0%, indicating low heterogeneity, and a FEM was used for analysis. Meta-analysis revealed a significantly greater improvement in fatigue in the intervention group compared to the control group following acupuncture treatment (SMD: −0.34; 95%Cl: −1.01, 0.33), (P < 0.05; Figure 8).

Figure 8

Meta-analysis of fatigue.

3.4 Subgroup meta-analysis

Significant heterogeneity was detected across the outcomes (VAS, FIQ, depression, and sleep). To investigate the sources of this heterogeneity, subgroup analysis were explored by treatment course and different intervention measures in the control group.

3.4.1 VAS

Subgroup analysis by intervention duration demonstrated that, at 2–4 weeks, 5–6 weeks, and 8–12 weeks, acupuncture exhibited substantially lower VAS scores compared to the control group (SMD: −1.11; 95% CI: −1.34, −0.88; I2 = 31.6%), (SMD: −0.46; 95% CI: −0.77, −0.16; I2 = 0.0%), and (SMD: −0.58; 95% CI: −0.80, −0.37; I2 = 46.5%), with all differences reaching statistical significance (P < 0.05). The reduction of heterogeneity suggested that different treatment durations in the intervention group may be the source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S2).

3.4.2 FIQ

A subgroup meta-analysis of the FIQ acupuncture intervention course revealed that, at 2–4 weeks, 5–6 weeks, and 8–12 weeks, acupuncture showed superior outcomes in FIQ compared to control group (SMD: −0.87; 95% CI: −1.16, −0.59; I2 = 0.0%), (SMD: −0.56; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.23; I2 = 17.1%), and (SMD: −1.66; 95% CI: −3.27, −0.04; I2 = 96.5%), demonstrating a marked improvement that reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). According to the subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity of 2–4 weeks and 5–6 weeks decreased significantly compared with the previous one, indicating that the course of 8–12 weeks may be the source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S3).

3.4.3 Depression

A subgroup analysis was conducted on different intervention measures (sham acupuncture, medication, no intervention) in the control group. The results showed that acupuncture significantly improved depression compared to sham acupuncture and medication (SMD: −0.74; 95% CI: −1.12, −0.36; I2 = 41.3%), (SMD: −1.03; 95% CI: −1.41, −0.65; I2 = 43.1%), the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Since only one study had a no intervention control group, it was not meaningful for comparison. After subgroup analysis, heterogeneity decreased compared to before, suggesting that different intervention measures in the control group may be a source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S4).

3.4.4 Sleep

A subgroup analysis of the acupuncture for sleep showed that at 2–4 weeks and 8–12 weeks, the intervention group had significantly better sleep outcomes compared to the control group (SMD: −0.78; 95% CI: −1.38, −0.18; I2 = 80.4%), (SMD: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.15, 0.84; I2 = 0.0%), the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Subgroup analysis showed that heterogeneity decreased significantly between 8–12 weeks compared to 2–4 weeks, suggesting that the 2–4 week treatment course may be the source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S5).

3.5 Meta-regression analysis

To investigate the sources of high heterogeneity in VAS, we performed meta-regression analysis. For VAS, we incorporated treatment duration into the model. Meta-regression results showed P = 0.009 < 0.05, indicating that treatment duration significantly influenced outcomes and was thus a source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S6).

3.6 Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the findings across the six key metrics (VAS, FIQ, number of pain points, depression, sleep, and fatigue). The exclusion of any single study from the analysis had no substantial impact on the magnitude of the pooled effect estimate, the SMD value differed little from the original overall SMD value, and statistical significance was maintained with the P-value consistently remaining below 0.05, indicating that the meta-analysis results of the above six indicators are robust and reliable (Supplementary Figure S7).

3.7 Publication bias

The inverted funnel plot for VAS and FIQ showed that all studies are within the 95% CI and are symmetrically distributed, suggesting a low possibility of publication bias for VAS and FIQ (Egger analysis: P = 0.575, 0.083 > 0.05; Supplementary Figure S8).

3.8 Certainty assessment

The assessment of evidence quality was conducted using the GRADE approach (Table 2). The results showed that the evidence grade for VAS, FIQ, depression, and sleep was rated as low due to the inclusion of studies with heterogeneity and a risk of bias in the results. However, there were no issues with other aspects, so their evidence grades were rated as moderate. The number of pain points included studies at risk of bias, with a sample size of no more than 300, so the evidence grade was rated as low. Fatigue included articles at risk of bias, but there were no other issues, so the evidence grade was rated as moderate.

Table 2

| Outcomes | Number of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients | Effect | Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | SMD (95%CI) | |||||||||

| VAS | 13 | Randomized trials | Serious | Serious | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | No serious | 426 | 423 | −0.75 (−0.99, −0.50) | Low |

| FIQ | 10 | Randomized trials | Serious | Serious | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | No serious | 345 | 344 | −0.98 (−1.43, −0.53) | Low |

| Number of pain points | 5 | Randomized trials | Serious | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious | No serious | 113 | 124 | −1.36 (−1.65, −1.08) | Low |

| Depression | 9 | Randomized trials | Serious | Serious | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | No serious | 244 | 243 | −0.78 (−1.10, −0.47) | Low |

| Sleep | 6 | Randomized trials | Serious | Serious | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | No serious | 193 | 193 | −0.34 (−1.01, 0.33) | Low |

| Fatigue | 7 | Randomized trials | Serious | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | No serious | 186 | 180 | −0.51 (−0.72, −0.30) | Moderate |

Certainty assessment.

4 Discussion

This analysis encompassed 17 RCTs with a total of 1,066 participants to assess the efficacy of acupuncture for FMS. The meta-analysis results showed that the treatment group had a significantly greater reduction in VAS (SMD: −0.77; 95% CI: −1.00, −0.55), FIQ (SMD: −0.98; 95% CI: −1.43, −0.53), the number of pain points (SMD: −1.36; 95% CI: −1.65, −1.08), and improved depression and fatigue (SMD: −0.78; 95% CI: −1.10, −0.47), (SMD: −0.51; 95% CI: −0.72, −0.30), P < 0.05, but did not significantly improve sleep quality (P > 0.05).

Compared with recent similar studies, both this research and Valera-Calero's review (32) employed control group settings closer to clinical practice, such as conventional analgesic medications or no intervention. This enhanced the clinical applicability of their conclusions in real healthcare decision-making environments. However, this design also introduces higher heterogeneity. In contrast, Zheng 's study (33) strictly limited the control group to sham and simulated or placebo acupuncture to validate acupuncture's specific therapeutic effects. While this approach yields higher internal validity, its conclusions may be conservative due to potent placebo effects, resulting in relatively limited external validity. Second, findings on sleep improvement vary across studies. This research found no significant benefit for sleep enhancement, whereas Valera-Calero's analysis indicated short-term sleep improvements with dry needling and acupuncture. Such inconsistencies may stem from differences in treatment duration, follow-up periods, assessment tools, and acupoint prescriptions.

FMS is a chronic condition primarily characterized by widespread pain. This complex syndrome frequently presents with a constellation of co-occurring symptoms, including depression, sleep disorders, and fatigue (3). Symptoms are caused by the interaction of multiple factors, including central sensitization, neurotransmitter imbalance, neuroinflammation, HPA axis dysfunction, and mitochondrial metabolic abnormalities (34). Acupuncture provides a safe and effective treatment option for FMS through its multi-targeted, multi-level integrated regulatory effects.

Pain is a prominent manifestation of FMS, and the primary pathological mechanism underlying FMS pain is central sensitization, characterized by disrupted processing and perception of pain signals in the central nervous system (35). This process was driven by neurotransmitter imbalance, glial cell activation, inflammatory factor dysregulation, and peripheral-central signal interaction (36–38). The key pathological feature of central sensitization is an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. In animal studies of FMS, excitatory neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate were significantly elevated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, while inhibitory neurotransmitters like serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are reduced (39). In clinical studies, a fMRI studies have shown that neuronal activation in these regions is significantly higher than in healthy individuals, and increased connectivity in the periventricular gray matter leads to a lowered pain threshold and abnormal sensitivity to mild stimuli (40). A significant dysregulation exists between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission within the central nervous system of individuals with FMS. Studies demonstrate that cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P are markedly elevated (2–3 fold) in FMS patients compared to healthy controls, GABA levels in the insular cortex are reduced by approximately 30%, and glutamate levels are significantly elevated (41). A study found (42) that acupuncture treatment for chronic pain patients specifically enhances functional connectivity between the primary somatosensory cortex and the anterior insula. Acupuncture promotes the activation of the endogenous analgesic system to reduce pain. Acupuncture stimulation activates Aδ and C-type afferent nerve fibers, transmitting signals to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thereby activating brain regions such as the periaqueductal gray matter of the midbrain and the ventromedial nucleus of the medulla. The activation of these regions enhances the descending inhibitory pathways, releasing inhibitory neurotransmitters, thereby inhibiting the transmission of nociceptive signals in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (43, 44). Glial cell activation perpetuates central sensitization in FMS. In FMS model rats, the number of GFAP-positive cells in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord increased by more than 50% compared to normal rats. Activated astrocytes further disrupt inflammatory factors, exacerbating central sensitization (39). Additionally, dysfunction of the HPA axis in FMS patients leads to disrupted cortisol release rhythms, elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, and further promotes central sensitization (3, 45). Huang Yuting's research revealed that following electroacupuncture intervention, the number of GFAP-positive cells significantly decreased (P < 0.05), while simultaneously reducing spinal cord TNF-α levels. This suggests that suppressing astrocyte activation can diminish the release of inflammatory mediators (39). Peripheral pathology in FMS induces small fiber neuropathy and mast cell activation, which sustain central sensitization through “peripheral-central signaling.”At the peripheral level, acupuncture activates TRPV1 and TRPV2 channels on mast cells, promoting degranulation and release of immune mediators like histamine and adenosine. These interact with receptors on nerve endings, initiating neuroimmune regulation (46).

Fatigue ranks as the second most prevalent symptom reported by patients with FMS, following pain, characterized by persistent mental fatigue and impaired physical recovery, rather than mere physical exhaustion (47). Acupuncture improves fatigue in FMS primarily by promoting mitochondrial function and improving muscle microcirculation. Animal studies have shown that acupuncture at ST36 can increase mitochondrial biosynthesis in muscle tissue by approximately 35% and improve ATP production efficiency by 40–50% (48, 49). Additionally, an animal study reported (50) that acupuncture significantly increases the levels of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione, enhances antioxidant responses, and improves muscle strength and function.

Depressive symptoms in FMS patients are not merely psychological reactions but have a clear neurobiological basis. In FMS patients, chronic stress induces significant reductions in hippocampal expression of both 5-HT and BDNF, affecting neuronal plasticity and antidepressant capacity (51, 52). The findings of this study demonstrate that acupuncture alleviates depressive symptoms in FMS patients, consistent with previous research findings. Animal experiments have shown (53, 54) that acupuncture can increase 5-HT concentrations in the hippocampus of depressed model rats while reducing monoamine oxidase activity. Additionally, studies have found (55, 56) that electroacupuncture stimulation significantly enhances BDNF levels in the hippocampus of depressed rats, activates TrkB receptors and their downstream signaling pathways, and promotes neural regeneration. These mechanisms may explain the therapeutic effects of acupuncture on depressive symptoms associated with FMS.

In subgroup meta-analysis, we primarily examined the effects of acupuncture intervention duration and different intervention measures in the control group on meta-analysis results and heterogeneity. Acupuncture intervention duration may be a source of heterogeneity in VAS, FIQ, and sleep outcomes. It had no significant impact on meta-analysis results for VAS and FIQ scores but significantly influenced meta-analysis results for sleep outcomes. At 2–4 weeks, acupuncture improved sleep in FMS patients, but at 8–12 weeks, it had no significant effect on sleep. Exploring the reasons, it may be due to the acute analgesic and relaxation-inducing effects of acupuncture, which can improve sleep in the short term, but long-term improvement in sleep is not obvious. It may be that the acupuncture points used are not changed according to the symptoms and requires deeper and sustained mechanism regulation; another possible reason is that only two studies were conducted between 8 and 12 weeks, with a small sample size, which may have introduced bias in the results. In the treatment course analysis, symptom improvement was observed between 2 and 4 weeks, and acupuncture intervention between 8 and 12 weeks may be necessary to maintain efficacy. This study demonstrates that acupuncture is effective relative to sham acupuncture and medication, though the effect sizes differ. This implies that regardless of its mechanism, acupuncture remains a valuable therapeutic option. Further investigation with larger sample sizes is warranted to validate the effects of varying acupuncture treatment durations on sleep in FMS.

In clinical practice, in addition to acupuncture treatment, the selection of acupoints also significantly influences treatment outcomes. According to a study (57), commonly used acupoints include BL18, BL20, A Shi, SP6, and LI4. Additionally, based on the different symptoms associated with FMS, different acupoints are selected. For example, for depression, GV20, GV29, and LR3 are used; for fatigue, ST36 and BL23 are used; and for sleep disorders, PC6 and BL15 are used. Therefore, in acupuncture treatment for FMS, in addition to the basic commonly used acupoints, different acupoints should be added based on the accompanying symptoms presented by the patient to enhance therapeutic efficacy. This study and previous research demonstrate that acupuncture reliably improves pain, depression, and fatigue in FMS patients. It may be considered for inclusion in clinical pathways as a complementary or alternative approach to pharmacological treatment. Given variations in treatment response across different durations, clinical adjustments based on disease severity are recommended: mild cases may undergo 2–4 weeks of treatment, while moderate to severe cases should extend therapy to 8–12 weeks to sustain efficacy. Establish interdisciplinary teams to jointly advance evidence translation and resolve professional coordination issues in clinical practice.

Among the included studies, 6 studies reported local adverse reactions to acupuncture (discomfort, pain, bruising, hematoma), 5 studiesmentioned systemic adverse reactions (dizziness, nausea, weakness, vasovagal symptoms), while the remaining studies did not report any adverse reactions. These reactions were typically transient and self-limiting, well tolerated by patients, and rarely led to treatment discontinuation. Therefore, during acupuncture treatment, attention should be paid to patients with bleeding tendencies or a history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease to prevent bleeding, nausea and dizziness.

Limitations and outlook

1. Some of the articles included in this study did not use a blind method, this may have some effect on the outcome; 2. The sample size for some of the study indicators was too small, and the results may have been affected by the small sample effect; 3. High heterogeneity across some outcomes, and some included studies have unclear or high risk of bias may introduced a certain degree of bias in the results; 4. Potential publication bias due to concentration of single-center Chinese RCTs. These findings should be verified in future higher-quality studies with larger sample sizes. At the same time, this study may provide evidence-based support for acupuncture treatment of FMS and serve as a reference for subsequent clinical studies.

5 Conclusions

Acupuncture can reduce patients' pain, improve depression and fatigue, and lower overall FIQ scores to treat FMS. Future high-quality research with larger sample is necessary to corroborate these results.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TY: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1710642/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Rusu C Gee ME Lagacé C Parlor M . Chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in Canada: prevalence and associations with six health status indicators. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (2015) 35:3–11. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.35.1.02

2.

Wolfe F Clauw DJ Fitzcharles MA Goldenberg DL Häuser W Katz RL et al . 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2016) 46:319–29. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012

3.

Häuser W Ablin J Fitzcharles MA Littlejohn G Luciano JV Usui C et al . Fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2015) 1:15022. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.22

4.

Mease P Arnold LM Choy EH Clauw DJ Crofford LJ Glass JM et al . OMERACT fibromyalgia working group. Fibromyalgia syndrome module at OMERACT 9: domain construct. J Rheumatol. (2009) 36:2318–29. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090367

5.

Sarzi-Puttini P Giorgi V Marotto D Atzeni F . Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2020) 16:645–60. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00506-w

6.

Clarke H Peer M Miles S Fitzcharles MA . Managing pain in fibromyalgia: current and future options. Drugs. (2025). 85:1081–92 doi: 10.1007/s40265-025-02204-x

7.

Mahagna H Amital D Amital H A . randomised, double-blinded study comparing giving etoricoxib vs. placebo to female patients with fibromyalgia. Int J Clin Pract. (2016) 70:163–70. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12760

8.

Macfarlane GJ Kronisch C Dean LE Atzeni F Häuser W Fluß E et al . EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:318–28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724

9.

Iannuccelli C Guzzo MP Atzeni F Mannocci F Alessandri C Gerardi MC et al . Pain modulation in patients with fibromyalgia undergoing acupuncture treatment is associated with fluctuations in serum neuropeptide Y levels. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2017) 35(Suppl 105):81–5.

10.

Lin YW Chou AIW Su H Su KP . Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) modulates the therapeutic effects for comorbidity of pain and depression: the common molecular implication for electroacupuncture and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:604–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.033

11.

Hsiao IH Lin YW . Electroacupuncture reduces fibromyalgia pain by attenuating the HMGB1, S100B, and TRPV1 signalling pathways in the mouse brain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2022) 2022:2242074. doi: 10.1155/2022/2242074

12.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

13.

Karatay S Okur SC Uzkeser H Yildirim K Akcay F . Effects of acupuncture treatment on fibromyalgia symptoms, serotonin, and substance p levels: a randomized sham and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain Med. (2018) 19:615–28. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx263

14.

Martin DP Sletten CD Williams BA Berger IH . Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. (2006) 81:749–57. doi: 10.4065/81.6.749

15.

Ugurlu FG Sezer N Aktekin L Fidan F Tok F Akkuş S . The effects of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Reumatol Port. (2017) 42:32–7.

16.

Assefi NP Sherman KJ Jacobsen C Goldberg J Smith WR Buchwald D . A randomized clinical trial of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med. (2005) 143:10–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00005

17.

Vas J Santos-Rey K Navarro-Pablo R Modesto M Aguilar I Campos MÁ et al . Acupuncture for fibromyalgia in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. (2016) 34:257–66. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010950

18.

Garrido-Ardila EM González-López-Arza MV Jiménez-Palomares M García-Nogales A Rodríguez-Mansilla J . Effects of physiotherapy vs. acupuncture in quality of life, pain, stiffness, difficulty to work and depression of women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:3765. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173765

19.

Aydin Özaslan E Ural Nazlikul FG Avcioglu G Erel Ö . Effects of acupuncture on oxidative stress mechanisms, pain, and quality of life in fibromyalgia: a prospective study from Türkiye. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. (2024) 71:174–86. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2024.14372

20.

Gong W Wang Y . Observations on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture on fibromyalgia syndrome. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2010) 29:725–27.

21.

Wu H Liu Y . Observation on therapeutic effect of acupuncture at Huatuo Jiaji acupoints combined with electroacupuncture on fibromyalgia syndrome. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med. (2022) 31:1487–91.

22.

Guo Y Sun Y . Clinical study on treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with penetration needling at the back. Chin Acupunct Moxibust. (2005) 30–2. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2005.02.010

23.

Wang W Liu Z Wu Y . 42 cases of clinical observation on fibromyoma syndrome with typing treatment based on differentiation of symptoms and signs according to acupuncture. Forum Tradit Chin Med (2004) 26–7.

24.

Liu Q Li F . Clinical analysis of acupuncture treatment for fibromyalgia in 30 cases. Anthol Med. (2002) 183–84.

25.

Yang C Zhang J Wang Z . Observations on the therapeutic effect of abdominal acupuncture combining with anti-depressant on fibromyalgia syndrome. J Yunnan Univ Tradit Chin Med (2015) 38:53–55 + 69. doi: 10.19288/j.cnki.issn.1000-2723.2015.05.012

26.

Garrido-Ardila EM González-López-Arza MV Jiménez-Palomares M García-Nogales A Rodríguez-Mansilla J . Effectiveness of acupuncture vs. core stability training in balance and functional capacity of women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2020) 34:630–45. doi: 10.1177/0269215520911992

27.

Hadianfard MJ Hosseinzadeh Parizi M . A randomized clinical trial of fibromyalgia treatment with acupuncture compared with fluoxetine. Iran Red Crescent Med J. (2012) 14:631–40.

28.

Ye Y Wang J . Effect of acupuncture on the sleep and life quality in the fibromyalgia syndrome patients. World J Sleep Med. (2019) 6:1054–56.

29.

Harris RE Tian X Williams DA Tian TX Cupps TR Petzke F et al . Treatment of fibromyalgia with formula acupuncture: investigation of needle placement, needle stimulation, and treatment frequency. J Altern Complement Med. (2005) 11:663–71. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.663

30.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al . RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

31.

Schünemann HJ Brennan S Akl EA Hultcrantz M Alonso-Coello P Xia J et al . The development methods of official GRADE articles and requirements for claiming the use of GRADE—a statement by the GRADE guidance group. J Clin Epidemiol. (2023) 159:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.05.010

32.

Valera-Calero JA . Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Navarro-Santana MJ, Plaza-Manzano G. Efficacy of dry needling and acupuncture in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9904. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169904

33.

Zheng C Zhou T . Effect of Acupuncture on pain, fatigue, sleep, physical function, stiffness, well-being, and safety in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. (2022) 15:315–29. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S351320

34.

Siracusa R Paola RD Cuzzocrea S Impellizzeri D . Fibromyalgia: pathogenesis, mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment options update. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:3891. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083891

35.

Mezhov V Guymer E Littlejohn G . Central sensitivity and fibromyalgia. Intern Med J. (2021) 51:1990–8. doi: 10.1111/imj.15430

36.

García-Domínguez M . Fibromyalgia and inflammation: unrevealing the connection. Cells. (2025) 14:271. doi: 10.3390/cells14040271

37.

Yao M Wang S Han Y Zhao H Yin Y Zhang Y et al . Micro-inflammation related gene signatures are associated with clinical features and immune status of fibromyalgia. J Transl Med. (2023) 21:594. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04477-w

38.

Jurado-Priego LN Cueto-Ureña C Ramírez-Expósito MJ Martínez-Martos JM . Fibromyalgia: a review of the pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary treatment strategies. Biomedicines. (2024) 12:1543. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12071543

39.

Huang Y Liao J Kang X Wang D Lin Y Zhang J et al . Study on the spinal cord and peripheral mechanisms of electroacupuncture in antiinflammation and analgesia in rats with fibromyalgia syndrome. Acupunct Res (2025) 50:919–27. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.20250043

40.

Richard JY Hurley RA Taber KH . Fibromyalgia: centralized pain processing and neuroimaging. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2019) 31:A6–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19050107

41.

Mawla I Ichesco E Zöllner HJ Edden RAE Chenevert T Buchtel H et al . Greater somatosensory afference with acupuncture increases primary somatosensory connectivity and alleviates fibromyalgia pain via insular γ-aminobutyric acid: a randomized neuroimaging trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2021) 73:1318–28. doi: 10.1002/art.41620

42.

Lin T Gargya A Singh H Sivanesan E Gulati A . Mechanism of peripheral nerve stimulation in chronic pain. Pain Med. (2020) 21(Suppl 1):S6–S12. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa164

43.

Duan Y Zhang Z Yin J . Effects of internal heat-type acupuncture needle intervention on chronic soft tissue pain based on central sensitization in the spinal cord. Chin J Pain Med. (2021) 27:888–97.

44.

Yen CM Hsieh CL Lin YW . Electroacupuncture reduces chronic fibromyalgia pain through attenuation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 signaling pathway in mouse brains. Iran J Basic Med Sci. (2020) 23:894–900. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2020.39708.9408

45.

Wen W Zhou R Li J . Study on the expressions of TRP,IL-1 and TNF-a in serum of caseswith fibromyalgia syndrome and the intervention of diacerein. Rheum Arthritis (2017) 6:17–20.

46.

Huang M Wang X Xing B Yang H Sa Z Zhang D et al . Critical roles of TRPV2 channels, histamine H1 and adenosine A1 receptors in the initiation of acupoint signals for acupuncture analgesia. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:6523. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24654-y

47.

Bair MJ Krebs EE . Fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 172:ITC33–ITC48. doi: 10.7326/AITC202003030

48.

Chen Z Yao K Wang X Liu Y Du S Wang S et al . Acupuncture promotes muscle cells ATP metabolism in ST36 acupoint local exerting effect by activating TRPV1/CaMKII/AMPK/PGC1α signaling pathway. Chin Med. (2025) 20:112. doi: 10.1186/s13020-025-01169-z

49.

Chen L Fan L Jiao Z . Research progress on mechanism of acupuncture in treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome in recent. Clin J Tradit Chin Med. (2024) 36:583–87.

50.

Felber DT Malheiros RT Tentardini VN Salgueiro ACF Cidral-Filho FJ da Silva MD . Dry needling increases antioxidant activity and grip force in a rat model of muscle pain. Acupunct Med. (2022) 40:241–8. doi: 10.1177/09645284211056941

51.

Henao-Pérez M López-Medina DC Arboleda A Bedoya Monsalve S Zea JA . Patients with fibromyalgia, depression, and/or anxiety and sex differences. Am J Mens Health. (2022) 16:15579883221110351. doi: 10.1177/15579883221110351

52.

Huang Y Chen W Li X Tan T Wang T Qiu S et al . Efficacy and mechanism of acupuncture in animal models of depressive-like behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. (2024) 18:1330594. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1330594

53.

Le JJ Yi T Qi L Li J Shao L Dong JC . Electroacupuncture regulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and enhance hippocampal serotonin system in a rat model of depression. Neurosci Lett. (2016) 615:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.01.004

54.

Kwon S Kim D Park H Yoo D Park HJ Hahm DH et al . Prefrontal-limbic change in dopamine turnover by acupuncture in maternally separated rat pups. Neurochem Res. (2012) 37:2092–8. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0830-1

55.

Jiang H Zhang X Lu J Meng H Sun Y Yang X et al . Antidepressant-like effects of acupuncture-insights from DNA methylation and histone modifications of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:102. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00102

56.

Park H Yoo D Kwon S Yoo TW Park HJ Hahm DH et al . Acupuncture stimulation at HT7 alleviates depression-induced behavioral changes via regulation of the serotonin system in the prefrontal cortex of maternally-separated rat pups. J Physiol Sci. (2012) 62:351–7. doi: 10.1007/s12576-012-0211-1

57.

Chen H Huang Z Hu X . Regularity of acupoints selection in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome by acupuncture and related therapies. Chin J Ethnomed Ethnopharm (2021) 30:10–14.

58.

Borenstein M Hedges LV Higgins JP Rothstein HR A . basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. (2010) 1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12

Summary

Keywords

acupuncture, fibromyalgia syndrome, FSM, meta-analysis, systematic review

Citation

Ye Z, Xue C, Liu Q, Li X, Yu T and Wei H (2026) The efficacy of acupuncture treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1710642. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1710642

Received

22 September 2025

Revised

09 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Stefano Masiero, University of Padua, Italy

Reviewed by

Wanderley Augusto Arias Ortiz, El Bosque University, Colombia

Akash Pathak, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences (SGPGI), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ye, Xue, Liu, Li, Yu and Wei.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hewei Wei, whwhou@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.