Abstract

This review explores the concept of dilutional rheomodulation in dermal fillers with the addition of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and its potential to improve both aesthetic and regenerative outcomes. PRP is a biological product rich in growth factors and cytokines derived from the patient’s own blood, which plays a significant role in tissue regeneration and healing. According to previous studies that utilized titrated aqueous solutions as solvents, it is hypothesized that incorporating PRP into different dermal filler formulations may be effective for modulating the rheological parameteres of dermal fillers while providing regenerative and immunomodulatory properties, potentially improving biocompatibility, injectability, distribution, and overall tissue integration as suggested by preliminary investigations. This combined approach may reduce severe adverse effects associated with filler injections while enhancing their biostimulatory effects. Moreover, PRP has been shown to stimulate collagen production and promote skin regeneration, which may extend the filler’s longevity and improve skin texture and elasticity. Although early studies suggest positive outcomes, further clinical trials are needed to determine optimal dilution ratios, establish best practices, and assess long-term safety and efficacy. This review highlights the promising potential of PRP-filler combinations in advancing aesthetic procedures through the integration of immediate volumization with regenerative skin enhancement.

Introduction

During the last decades, aesthetic and regenerative medicine have shifted focus from conventional structural interventions toward strategies that enhance endogenous self-repairing mechanisms (1). In this context, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has gained attention as an autologous biological product with regenerative potential (2). PRP provides growth factors and cytokines—including PDGF, TGF-β, VEGF, EGF, IGFs, and FGFs—crucial for tissue repair, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and extracellular matrix remodeling (3). Its use in dermatology and aesthetic medicine has grown significantly, supported by a strong safety profile and evidence for effectiveness in skin rejuvenation, alopecia, inflammatory dermatoses, and wound healing (4).

Injectable dermal fillers have also become essential for addressing age-related volume loss, facial sculpting, and dermal support (5). Their applications extend beyond cosmetic volume restoration to scar revision (6), lipodystrophy correction in HIV (7), post-traumatic or post-surgical contour defects (8), and regenerative purposes when combined with bioactive compounds (9). Soft-tissue fillers vary in composition, rheology, residence time, and biological interactions (10). These factors determine mechanical behavior—including viscoelasticity and cohesivity—which influence tissue integration, resistance to deformation, and biomechanical response (11). Additionally, biological behavior includes interactions with the extracellular matrix and immune system, biocompatibility, potential inflammatory or granulomatous reactions, and capacity to stimulate fibroblasts, induce neocollagenesis, or remodel tissue (12).

The longevity of a dermal filler denotes the duration over which it maintains clinical efficacy before enzymatic degradation or resorption, largely dependent on molecular composition, cross-linking, and physicochemical stability (13). Injectable implants can be broadly categorized into temporary, semi-permanent, and permanent fillers (14). Temporary fillers, commonly based on hyaluronic acid (HA), carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), polyethylene oxide (PEO) or collagen (bovine, porcine, or human), are biodegradable and well-tolerated, offering reversible results with a favorable safety profile (15). Semi-permanent fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA), high-density or cross-linked HA, and polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) provide longer-lasting outcomes by maintaining mechanical volume and, in some cases, stimulating neocollagenesis while gradually resorbing (16). Permanent fillers, including polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), acrylic hydrogels, polyalkylimide–polyacrylamide hydrogels, polyvinyl microspheres in polyacrylamide, e-polytetrafluoroethylene, Gore-tex, and autologous fat offer sustained volume but carry higher risks of adverse reactions (17). Autologous dermal fillers, a subclass of regenerative treatments, use the patient’s own tissue or cells—fat, dermis, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), PRP, plasma-derived gel, or combinations—for facial rejuvenation and volumization. They generally provide more natural outcomes (18–25), though volume loss and fat harvesting complexity remain challenges. Nevertheless, they are promising options for personalized, non-synthetic treatments with lower complication risk (26).

In this context, it is critical to distinguish dermal fillers from biostimulators based on primary function (27). This distinction relates to their mechanism of action and physical properties. Classical dermal fillers, such as HA, CaHA, PMMA, or PHB products, are typically viscoelastic gels designed for rapid volume replacement via structural support. Primary biostimulators—including Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), Poly-D-lactic acid (PDLLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), or hyperdilute CaHA—are usually administered as colloidal suspensions with minimal or transient filling capacity, whose action is independent of viscoelastic properties. Their main function is to trigger controlled cellular signaling, gradually inducing neocollagenesis and yielding long-term volume restoration through tissue regeneration (28). While many injectables exhibit both structural and bioactive effects, classification depends on the dominant mechanism (29). Most autologous materials—PRP, plasma gel, or fat/dermal grafts—display a dual role: providing immediate or semi-permanent volume and structural support, while promoting tissue regeneration through fibroblast activation, neocollagenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, combining volumizing and bio-stimulatory effects (21, 22, 30).

Dilution of dermal fillers is a strategic approach aimed at modulating their rheological and biostimulatory properties (31–33). The choice of diluent—ranging from sterile water, isotonic saline or lidocaine to autologous components such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or extracellular matrix-derived solutions—significantly affects the structural integrity and biological performance of the filler (31, 34, 35). The use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) as a diluent for dermal fillers may confer additional advantages, including enhanced biocompatibility, improved tissue integration, and stimulation of regenerative processes through the localized delivery of autologous growth factors (31, 36). The aim of this review is to synthesize the current state of knowledge and recent advances in the field of dilution-based rheological and biological modulation of dermal fillers and biostimulants using platelet-rich plasma (PRP). This approach, which involves modifying the rheological and biological properties of injectable biomaterials through dilution with autologous PRP, has emerged as a promising strategy to support filler biocompatibility, influence tissue integration, and possibly reduce adverse inflammatory responses. These combined effects are hypothesized to not only improve the clinical efficacy and aesthetic outcomes of filler treatments but also extend their durability and regenerative potential within the treated tissues.

Results

Dilutional rheomodulation of dermal fillers

The rheology of PRP is central to understanding its clinical performance and interactions with dermal fillers. Basic rheological parameters provide insight into specific viscoelastic responses. The elastic or storage modulus (G′) represents the portion of the deformation energy that is stored and then recovered during each oscillatory cycle, reflecting the material’s stiffness and solid-like behavior or resistance to deformation, while the loss or viscous modulus (G”) characterizes the flow-like component or the mechanical energy dissipated when the material undergoes structural changes (37). As summarized by McCarthy et al. (33), the loss tangent (tanδ) indicates the relative contribution of viscous and elastic behavior in each case, correlating with spreadability and fluidity. The complex modulus (G*) integrates elastic and viscous components, serving as an overall measure of gel strength. In addition, complex viscosity governs flow resistance, reflecting the material’s response to deformation and providing insight into its behavior during injection. Similarly, yield stress represents the minimum stress necessary to initiate flow, which is relevant for handling and injectability of dermal fillers and biostimulants, whereas cohesivity reflects the internal cohesion of the gel, influencing its ability to maintain shape and integrate with surrounding tissue. Collectively, these parameters provide a mechanistic framework for evaluating handling, injectability, and in vivo performance of dermal fillers and biostimulants. In this scenario, PRP exhibits unique viscoelastic behavior that is highly dependent on activation status and preparation conditions. Non-activated PRP and PRP-derived supernatants behave largely as Newtonian fluids, with low viscosity and minimal viscoelastic properties, offering negligible mechanical support when used alone (38–40). However, activation with calcium, thrombin, or collagen, as well as temperature variations, promotes fibrin polymerization, increasing G′ and overall gel stability.

The type of PRP activator and its combinations significantly influence both gel viscoelasticity and formation kinetics (41). For example, thrombin results in the firmest gels, characterized by the highest G′ and almost instantaneous gelation (42, 43). On the other hand, Calcium-based activation produces firm gels with moderately high G′ and gelation over 15–30 min (44–46), whereas collagen type I generates softer, more flexible gels with low G′ and much slower or minimal clot formation (47), highlighting that both activator selection or the combination of different activators dictate mechanical behavior and factor release.

The viscoelastic behavior of activated PRP is also correlated with both platelet and activator concentrations, with increased activator generally producing a more solid-like network, where elastic behavior (G′) dominates over viscous response (G″) (44). Moreover, temperature-based activation of PRP induces the formation of a fibrin network with enhanced G′ and sustained growth factor release, while thermal oscillation can transform liquid PRP into a dense, highly viscous paste with improved structural stability, potentially improving mechanical retention and bioactivity (48, 49). In addition, plasma gels formed through thermal treatment and albumin denaturation exhibit significantly increased viscoelasticity, with a solid-like network (high G′) that provides structural support and serves as a reservoir for bioactive molecules (21, 50, 51). As a result, the rheological properties of PRP can be precisely tailored by adjusting or combining different preparation methods and preparations, reflecting the broad textural versatility achievable through procedural variations that modulate its viscoelastic characteristics (21).

In this sense, evidence from composite hydrogel systems, including CaHA-CMC, CaHA-HA, and HA-PRP, demonstrates that dilutions with viscoelastic components produce nonlinear rheological effects that differ significantly from saline dilution (32, 33, 52–57). Accordingly, activated PRP-containing formulations are expected to form stronger, more cohesive composite gels than saline, non-activated PRP or PRP supernatant-diluted gels, with customizable rheological properties that allow precise modulation of filler performance and bioactive component delivery.

The timing of PRP activation – prior or subsequent to mixing with the filler or biostimulant- also represents a critical determinant of the rheological behavior of PRP-filler composites. Results obtained using PRP in its non-combined form have shown that it behaves primarily as a low-viscosity quasi-Newtonian protein solution until the onset of fibrin polymerization (39, 40), allowing for a more homogeneous mixture, lower extrusion force, and minimal early changes in viscosity, with fibrin matrix formation occurring in situ after filler injection. In contrast, PRP activation induces time-dependent fibrin polymerization and clot formation, leading to a swift increase in viscosity and cohesivity, higher extrusion forces, potential clogging, and non-uniform particle-fibrin distribution (42–44). Therefore, activation timing must be carefully considered when designing PRP-based composite gels to balance injectability, homogeneity, and rheological properties. However, the effects of PRP activation must be systematically assessed in each experimental context, since its interactions with diverse biomaterials are modulated by multiple factors, including the biomaterial’s concentration, particle size, surface topography and chemical composition, the dilution factor applied, the intrinsic cellular and biochemical profile of each specific PRP formulation, and the activation strategy adopted.

The rheological characterization of diluted injectables is essential for understanding their mechanical behavior, optimizing their delivery, and ensuring reproducibility in clinical applications. Table 1 provides an overview of key physical and rheological properties of the most common individual and composite dermal fillers and biostimulators, including their dilutions, as documented in the literature. Variations in viscosity, shear-thinning behavior, and viscoelasticity directly influence injectability, distribution in tissue planes, and cellular viability (58, 59). Comprehensive rheological profiling supports the standardization of protocols and enhances the predictability of graft integration and regenerative outcomes. Dilutional rheomodulation constitutes an emerging strategy in the modulation of dermal filler behavior, enabling precise control over their rheological properties (32). By diluting filler materials with isotonic solutions or bioactive agents —ranging from sterile water, saline or lidocaine to autologous components such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or extracellular matrix-derived solutions— it is possible to modulate critical parameters. From a biophysical perspective, dilution —when the filler’s viscoelasticity exceeds that of the diluent— reduces the filler’s viscosity and elastic modulus (G′), increasing spreadability, improving flow through fine-gauge needles and allowing for more uniform distribution across tissue planes (33). For example, the addition of PRP to hyaluronic acid (HA) results in a reduction of viscoelastic shear moduli and an increase in the crossover point, primarily attributable to a dilutional effect (53). This approach is particularly advantageous in treatments requiring subtle volumization or superficial placement, where high-viscosity gels may cause irregularities, overcorrection or overfilling (60, 61). Nevertheless, because the rheological parameters of PRP preparations can be extensively customized through procedural variations—including activation method, timing, incubation temperature, or the combination of different formulations—PRP dilution may be used to increase the viscoelasticity of low- to medium-viscoelasticity dermal fillers and biostimulatory agents, including collagen, low-density non-crosslinked HA, PLLA, and PDLLA.

TABLE 1

| Material | Dilution | G′ (Pa)1 | G″ (Pa)2 | G* (Pa)3 | tanδ4 | η* (Pa⋅s)5 | Cohesivity6 | Yield stress (Pa)7 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | Undiluted | 962 | 422.9 | 1050.85 | 0.44 | ≈2,00013 | High | 48 | (32, 33, 57) |

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | 1:0.25 | 113.2 | 92.49 | 146.18 | 0.817 | ≈10013 | Low | 5.7 | (32, 33) |

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | 1:0.5 | 40.78 | 42.61 | 59.98 | 1.045 | ≈9013 | Low | 2 | (32, 33) |

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | 1:1 | 8.369 | 12.42 | 14.977 | 1.484 | ≈2513 | Low | 0.42 | (32, 33) |

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | 1:2 | 1.021 | 2.512 | 2.712 | 2.46 | ≈213 | Low | 0.05 | (32, 33) |

| CaHA-CMC + saline8 | 1:3 | 0.119 | 0.6164 | 0.628 | 5.18 | ≈113 | Low | 0.006 | (32, 33) |

| PLLA8 | Undiluted | 0.015 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.00075 | (32) |

| HA9 | Undiluted | 6.93–603.14 | 8.79–91.7 | 11.19–584.87 | 0.15–1.27 | 149.09–1629.9 | Low to high | 0.35–30 | (55, 57, 170, 171) |

| HA + CaHA entrapped (10% m/v)10 | Undiluted | ≈20013 | ≈2013 | ≈20114 | ≈0.1014 | NR | NR | 10 | (55) |

| HA + CaHA entrapped (10% m/v)10 | 20% (m/v) CaHA free | ≈30013 | ≈4013 | ≈30314 | ≈0.1314 | NR | NR | 15 | (55) |

| HA + CaHA entrapped (10% m/v)10 | 45% (m/v) CaHA free | ≈90013 | ≈10013 | ≈90614 | ≈0.1114 | NR | NR | 45 | (55) |

| HA10 | 10% (m/v) CaHA entrapped | ≈20013 | ≈2013 | ≈20114 | ≈0.1014 | NR | NR | 5.5 | (55) |

| HA10 | 30% (m/v) CaHA entrapped | ≈60013 | ≈7013 | ≈60414 | ≈0.1214 | NR | NR | 30 | (55) |

| HA10 | 30% (m/v) CaHA free | ≈30013 | ≈4013 | ≈30314 | ≈0.1314 | NR | NR | 6 | (55) |

| HA + CaHA-CMC10 | 1:1 | 260.58–703.22 | 173.52–296.92 | 313.08–763.35 | 0.42–0.67 | 19.16–29.38 | Medium | 5–35 | (52) |

| HA + CaHA-CMC10 | 1:2 | 139.81–495.83 | 104.9–183.13 | 174.79–528.58 | 0.37–0.75 | 20.18–27.74 | Medium | 7–25 | (52) |

| HA + CaHA-CMC10 | 1:3 | 103.08–424.12 | 90.91–146.76 | 131.75–448.8 | 0.35–0.8 | 19.37–27.75 | Low–medium | 5–21 | (52) |

| HA + CaHA-CMC10 | 1:4 | 86.31–388.95 | 71.16–126.16 | 113.5–408.9 | 0.32–0.86 | 19.61–28.43 | Low–medium | 4–19 | (52) |

| PMMA-Collagen11 | Undiluted | 2815.27 | NR | NR | NR | 656.41 | NR | 141 | (159) |

| PRP non-activated | Undiluted | NR | NR | <0.113 | NR | <0.0113 | Low | <0.005 | (38–40) |

| PRP activated12 | Undiluted | ≈5–8013 | ≈1–513 | ≈3–8013,14 | ≈0.1–4014 | NR | Low | 0.4–4 | (43, 44) |

Physical and rheological properties, including dilutions, of common individual and composite dermal fillers and biostimulatory agents at the low-frequency regime.

1 G ′(Pa), storage modulus; NR, not reported.

2 G ″(Pa), loss modulus.

3 G*(Pa), complex modulus.

4tanδ, loss tangent.

5Complex viscosity η*(Pa⋅s).

6Cohesivity was classified based on G* and drop-test volume: low (∼200–400 Pa, >50 μL/drop), medium (∼400–800 Pa, 21–50 μL/drop), high (>800 Pa, 5–20 μL/drop) (11, 57).

7Yield stress (σy) was estimated from the measured storage modulus (G′) under the assumption of a representative critical strain (γ c = 0.05) corresponding to the limit of the linear viscoelastic region, as commonly applied in soft gels and dermal fillers (172, 173). The calculation follows the relation σy ≈ G′⋅γ c, providing an approximate, literature-supported value of the stress at which the material begins to yield. This approach allows comparison across different fillers and biostimulaory composites, while noting that exact yield stress should ideally be determined experimentally via amplitude sweep or creep tests.

8Rheological measurements evaluated at 0.1 Hz with a steady shear deformation of 0.1% under ambient conditions (25 °C).

9Rheological measurements were conducted at 0.1 Hz using small-amplitude oscillatory shear within the Linear Viscoelastic Region (LVER) at 37 °C.

10Rheological measurements evaluated at 1 Hz with a steady shear deformation of 0.1% under ambient conditions (25 °C).

11Rheological measurements evaluated at 0.7 Hz within the Linear Viscoelastic Region (LVER) under ambient conditions (25 °C).

12Rheological measurements evaluated at 0.1 Hz at 20 °C–25 °C.

13Data estimated from visual inspection of G′, G″, and η* curves; values are approximate and intended for comparative purposes.

14 G* and tanδ were calculated from the primary moduli using the constitutive relationships: G* (Pa) = √(G′2 + G″2); tan δ = G″/G.

Dilution also increases the total filler volume and may promote a more uniform distribution of bioactive components, while the effect on injection precision depends on the resulting rheological properties of the mixture (62). Despite the generally favorable safety profile of dermal fillers, with most adverse events being mild and transient, rare but serious side effects have been documented, including infection, granuloma and vascular complications (63–69). Dilution-induced alterations in the rheological properties of dermal fillers can have significant implications for their safety profile, leading to a significant decrease in the amount of obstructive particles per volume of intravascular injectate and a reduction of the product’s cohesivity, resilience and elastic modulus, which are potential contributors to different mechanisms involving intravascular occlusion and external compressive forces (33, 56). Although the frequency of such adverse events is low, comprehensive safety assessment requires a large dataset derived from multiple studies involving different dermal fillers, dilution protocols, and clinical applications. Nevertheless, preliminary evidence suggests that individuals treated with diluted or hyperdiluted formulations may experience a lower rate of severe adverse reactions (70–74).

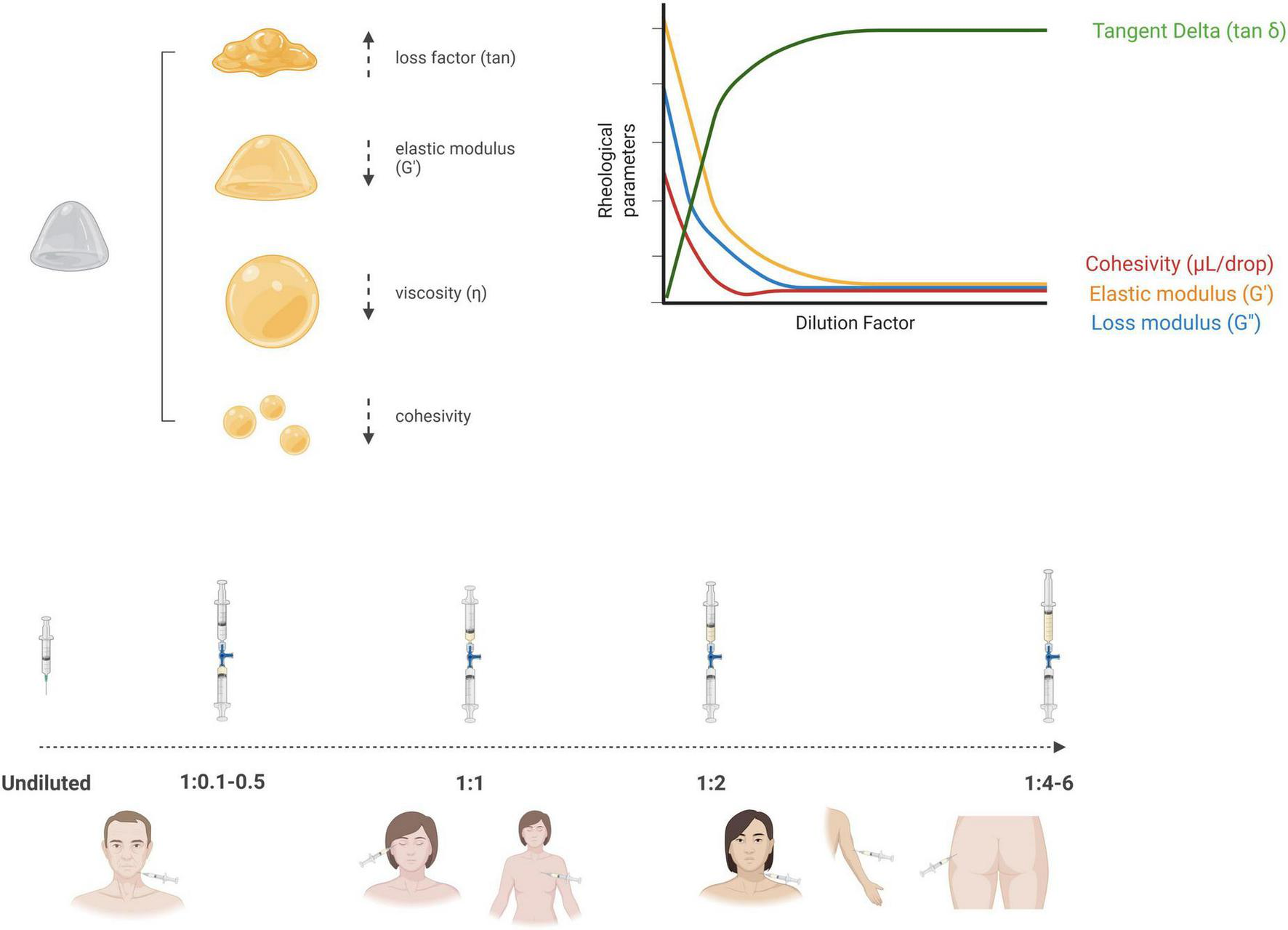

Figure 1 provides a synthesis of the concept of dilutional rheomodulation, illustrating its fundamental principles and highlighting its optimal applications in enhancing the rheological performance and clinical outcomes of dermal fillers. Most dilutional rheomodulation research has focused on investigating the effects of titrated aqueous solutions on rheological parameters of semi-permanent CaHA-based formulations combined with CMC (CaHA-CMC), a biphasic gel composed of suspended CaHA microspheres 25–45 μm in diameter (30% w/v) within a hydrophilic carrier (70% w/v), which includes water, glycerin and CMC (Radiesse, Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC, United States) (70). In rheological terms, CaHA demonstrates higher G′ and viscosity values than other commercially available HA-based dermal fillers (75). Due to its high viscoelasticity, undiluted CaHA-CMC-based filler is optimally suited for deep dermal implantation and volumetric correction (57, 76, 77). Recommended treatment paradigm for diluted and hyperdiluted CaHA-CMC has been published by Goldie et al. (72), de Almeida et al. (78), Corduff et al. (79), Green et al. (80), ranging from undiluted CaHA-CMC (volume augmentation and structural support in areas like the chin, jawline, and temples) or diluted at 1:1 (facial rejuvenation, cellulite, striae or abdomen) to hyperdiluted 1:2–1:4 (laxity of the upper arm, neck or décolletage skin tightening or skin quality improvement) or even 1:6 as biostimulants (gluteal sagging or mild dermal irregularities on the buttocks).

FIGURE 1

Schematic illustration of dilutional rheomodulation, depicting how controlled dilution modulates the viscosity and viscoelastic properties of a material to optimize its flow behavior and functional performance (Created in BioRender. Anitua, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/11gkb15).

According to Lorenc et al. (81), when CaHA-CMC is diluted at a 1:1 ratio with a biocompatible diluent, it retains partial volumizing effects due to the preservation of its intrinsic viscoelastic properties. However, at dilution ratios of 1:2 or higher, the CaHA-CMC biphasic filler undergoes a marked shift in rheological behavior, resulting in a substantial loss of volumizing capacity (32, 33, 77, 82). In this hyperdiluted form, CaHA primarily acts as a biostimulatory agent rather than a filler (72). The hyperdiluted formulation yields a suspension of CaHA microspheres that enables uniform distribution across broad anatomical regions (79). Rather than serving a volumizing function, hyperdiluted CaHA facilitates dermal regeneration by stimulating neocollagenesis and elastogenesis (83). Consequently, dilution protocols must be approached based on particle dispersion kinetics and cellular activation, rather than maintaining specific rheological properties required for structural fillers. This shift in functional behavior supports its role in regenerative aesthetic procedures, where the primary objective is to enhance skin quality—specifically elasticity, pliability, and dermal thickness—rather than to provide structural augmentation (73). Nevertheless, the dilution of dermal fillers remains an unstandardized practice, characterized by significant variability in dilution ratios, types of diluents, and clinical indications. This lack of consensus highlights the imperative for an evidence-based framework to guide dilutional protocols.

Biological and clinical effects of dermal filler dilution

Despite the primary focus on traditional aqueous diluents such as sterile water, saline, lidocaine or lidocaine-epinephrine solutions, emerging attention is being directed toward novel formulations, such as poly-micronutrient-enriched solutions (84), exosomes (34), hyaluronidase or PRP (35). In this sense, non-activated PRP and PRP-derived supernatants demonstrate a basic rheological behavior similar to that of conventional aqueous diluents (38, 40). Its low viscosity and minimal elasticity facilitate the modulation of filler properties, enhancing injectability and distribution (39). Nevertheless, the rheological properties of PRP can be modulated through specific preparation parameters, including activation procedure, incubation time, temperature, and formulation strategy (21, 41–51). In addition, when PRP is utilized as a diluent for dermal fillers, the effects of dilutional rheomodulation can be synergistically enhanced through the inherent regenerative, anti-inflammatory and healing potential of the autologous platelet-rich derivative (35). Biostimulators can also be diluted to maximize the microparticle surface area available for cellular signaling, effectively shifting the primary mechanism from immediate structural support to widespread fibroblast stimulation and diffuse, long-term neocollagenesis (32, 33, 74, 85, 86). This dual functionality not only increases therapeutic efficacy but also reduces the risk of adverse effects related to immunogenicity (87) or contamination with impurities commonly associated with non-autologous fillers or diluents (88, 89). Therefore, PRP-based dilution of dermal fillers and biostimulants may help improve biocompatibility, potentially minimize adverse effects, and support tissue integration, ultimately contributing to optimized clinical outcomes in regenerative medicine applications.

Hyaluronic acid-based fillers

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a linear glycosaminoglycan naturally present in the extracellular matrix of vertebrate tissues, including connective, epithelial, and neural structures, with particularly high levels in the skin (90). Its capacity to bind water, along with its viscoelastic properties and biocompatibility with human tissue, has led to its widespread use as a dermal filler in aesthetic and reconstructive procedures (91). HA-based soft tissue fillers comprise several comercial formulations with particular characteristics (92), including Juvederm Ultra®, Juvederm Ultra Plus® or Juvederm Voluma® (Allergan Aesthetics an AbbVie Company, Irvine, CA, United States), Restylane® Restylane Lyft®, and Restylane Silk® (Galderma, Zug, Switzerland), Stylage® (Laboratoires VIVACY, Archamps, France), Princess® (Croma-Pharma GmbH, Leobendorf, Austria), and Belotero Balance® (Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC, United States) (93–95). When injected into the dermis or subcutaneous layers, HA helps restore soft tissue volume, reduce the appearance of wrinkles, and improve skin hydration (96). The results are temporary, as HA is progressively broken down by enzymes such as hyaluronidase, with clinical effects typically lasting up to 12 months, depending on the formulation and anatomical location (97, 98). Its favorable safety profile, reversibility, and low incidence of adverse immune responses have established HA as a cornerstone in minimally invasive facial rejuvenation (99).

Different combinations of PRP and HA-based injectable hydrogels have shown promising biological and clinical effects for facial rejuvenation (100) or skin defects management (101). A randomized controlled trial published by Hersant et al. (102) concluded that diluting HA-based filler (SkinVisc, Regen Lab, Switzerland) with autologous PRP (1:1) yielded enhanced outcomes in terms of skin elasticity and overall facial appearance when compared to the administration of either agent independently. Significant improvements in skin elasticity and skin smoothness have also been obtained using the combined PRP-HA technology for facial rejuvenation, which consists of tubes designed to prepare a mixture of PRP and non-crosslinked HA (103). Pirrello et al. (104) also demonstrated that filler injections of hyaluronic acid and PRP (A-CP HA kit, Regen Lab, Switzerland) in a similar proportion constitute an effective therapeutic option for patients with scleroderma considering both aesthetic appearance and functional improvement. Moreover, the hyperdilution of an HA filler (Tissuefill, JW Pharmaceutical, South Korea) with PRP (1:5) was reported to be effective and safe for facial augmentation (105). Analogous conclusions have been reached in studies aiming to evaluate the biological effect of HA-based hydrogels combined with PRP involving different therapeutic applications, including osteoarthritis management (106–108) or wound healing (109).

CaHA-based fillers

CaHA is a naturally-occurring mineral that is commonly used as a biocompatible and biodegradable dermal filler with demonstrated efficacy in enhancing cutaneous structural integrity (69, 110). Its regenerative action includes activation of collagen and elastin synthesis, vascular neogenesis, and proliferation of dermal cells (78). Examples of commercially available CaHA-based dermal fillers include Hydroxyfill® (Dr. Korman Laboratories Ltd., Kiryat Bialik, Israel), Radiesse® (Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC, United States) and HArmonyCa® (Allergan Aesthetics an AbbVie Company, Irvine, CA, United States) (111). Although the potential synergy between CaHA and HA has been examined (112–114), the prevailing body of evidence centers around CaHA-CMC biphasic formulations. CaHA suspended in a CMC matrix demonstrates a strong regenerative potential over a wide dilutional range due to its capacity to stimulate resident fibroblasts (71, 85, 115, 116). The biophysical engagement between these fibroblasts and the CaHA microspheres plays a pivotal role in initiating new tissue synthesis (117). Notably, optimal regenerative effects have been associated with diluted preparations (from 1:1 to 1:3), likely attributable to the increased interparticle spacing, which facilitates cellular activity and matrix remodeling. This relationship has been confirmed through both laboratory experimentation and histological evaluations in clinical settings (118).

Clinical data largely support the effectiveness and safety profile of diluted CaHA-CMC at 1:3 or even lower dilutions for facial rejuvenation (119), soft tissue augmentation (120) or for the treatment of dorsal hand volume loss (121, 122), at 1:1 for cellulite dimpling on the buttocks (123), hyperdiluted CaHA-CMC (1:2) for the improvement of decollete wrinkles in females (124, 125), for the correction of volume loss in the infraorbital region (126), for skin rejuvenation (127) and also for skin tightening (128) and hyperdiluted CaHA-CMC (1:3) for the treatment of perioral rhytids (129). In the same line, improved neocollagenesis and neoelastogenesis have been reported after injection of diluted and hyperdiluted CaHA-CMC in different areas (71, 74, 122, 130, 131). Collagen neosynthesis has been consistently detected between 1 and 12 months following administration of CaHA-based fillers (71, 114, 132–134), including in treatments utilizing highly diluted filler solutions (74, 135).

Since standard aqueous solutions exhibit no inherent regenerative capacity, their replacement with bioactive solutions such as PRP has been proposed to enhance tissue regeneration and improve clinical outcomes. Khalifian et al. (35) concluded that a single session of a combination therapy based on hyperdiluted CaHA-CMC at a 1:4 dilution with a mixture of PRP and hyaluronidase was well-tolerated and demonstrated improvements in skin texture, along with a reduction in cervical rhytides and tissue laxity. According to the authors, the synergistic effect of PRP-derived growth factors and cytokines may enhance the regenerative potential of CaHA-CMC, facilitating fibroblast activation, collagen and elastin fiber biosynthesis, neo-angiogenesis and overall skin quality enhancement (136). Such biological mechanisms have been consistently demonstrated in clinical practice (137). Future investigations should further explore the role of PRP as a diluent in CaHA-CMC filler protocols, with systematic comparisons with conventional aqueous-based solutions.

Other dermal fillers and biostimulants

Current literature provides limited insight into the biological and clinical consequences of diluting alternative injectable implant formulations. PLLA is an absorbable semi-permanent injectable biobased polymer that can be used to restore volume loss due to facial fat atrophy, while concurrently promoting dermal regeneration and skin texture improvement (138, 139). PLLA collagen-stimulators, including Sculptra® (Galderma, Zug, Switzerland) and Lanluma V® (Sinclair Pharma, London, United Kingdom), show a favorable safety profile, contribute to effectively increase volume, corrects laxity and improve contours, skin quality and the appearance of cellulite across various anatomical regions (140, 141). A trend toward higher reconstitution volumes in PLLA-containing injectable products has been observed in clinical practice, with lidocaine often added to the mixture to reduce injection-related discomfort (142–145). According to Palm et al. (146), the effectiveness of PLLA reconstituted with 8 mL of sterile water and 1 ml 2% lidocaine was similar to that of PLLA reconstituted with 5 ml of sterile water for the correction of nasolabial folds. To date, no published studies have been found addressing the use of PRP as a diluting agent for PLLA acid dermal fillers in the consulted literature. However, PRP-loaded PLLA-based biomaterials have demonstrated a strong regenerative potential in different soft tissue defect models (147, 148).

Collagen-based dermal fillers constitute a significant category of biodegradable non-permanent injectable materials in which the concept of dilutional rheomodulation, particularly involving PRP as an aqueous diluent or biostimulatory coadjuvant agent, remains under-investigated. Collagen is the predominant structural protein in vertebrate connective tissues, comprising approximately 30% of the total protein mass in the human body (149). The primary sources of collagen for the production of injectable formulations include bovine, porcine, swine, equine, and human tissues (150). Collagen-based dermal fillers, though available in numerous commercial forms with multiple origins and diverse biochemical profiles, present inherent challenges. These include susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, significant management and production costs, and risks associated with immunogenic responses and zoonotic disease transmission (151–155). To cite a few examples, Zyderm® and Zyplast® (Allergan, Dublin, Ireland), Cosmoplast® and Cosmoderm® (Inamed, Santa Barbara, CA, United States), GUNA® (GUNA, Milan, Italy) products or CartiRegen® (Joint Biomaterials, Mestre, Italy) (150). Regarding the effect of collagen dilution on dermal filler bioactivity, Weinkle (156), Yang et al. (157) demonstrated that the porcine-based dermal injectable collagen Dermicol-P35® (Evolence, Ortho Dermatologics, Skillman, NJ, United States) combined with lidocaine constitute useful therapeutic strategies for correcting nasolabial fold wrinkles.

Polymethyl methacrylate is a non-biodegradable filler that, similar to CaHA and PLLA, exerts its effects primarily by stimulating de novo collagen synthesis (98, 158). PMMA-collagen gel is indicated for correcting moderate to severe acne scars, malar atrophy and infraorbital rhytides and for volume augmentation in regions such as the temple, chin, mandible, piriform aperture, nasolabial folds (98, 158–165). Although no studies have been identified that combine PMMA-based dermal fillers with PRP, experimental results confirm that the rheological properties of the carrier are critical for ensuring homogeneous distribution of the microspheres, which facilitates interstitial tissue infiltration (158, 166). Upon enzymatic degradation of the carrier, the microspheres persist in situ, functioning as a three-dimensional scaffold that supports neocollagenesis and tissue regeneration (58). In this sense, the rheological properties of collagen-PMMA gels limit their suitability for certain superficial applications in the undiluted form. As a result, the potential use of these gels as a diluted or hyper-diluted biostimulatory agent has been previously highlighted in the literature (159).

Although there is a gap in research regarding the use of PRP in collagen-based dermal filler formulations, several studies have shown that functionalizing collagen-based hydrogels or scaffolds with PRP improves cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, vascularization, and the deposition of mature collagen (167–169).

Conclusion

This review consolidates current knowledge on PRP as a diluent for dermal fillers, examining theoretical rationale, clinical experience, and supporting evidence. It highlights limitations in existing data and suggests directions for further research in regenerative aesthetic medicine. Despite numerous studies addressing the role of dilutional rheomodulation in defining optimal therapeutic application of particular dermal fillers, they often limit analysis to clinical aptitude considering viscoelasticity, injectability, and filler volume, overlooking underlying biophysical factors. Future research should focus on elucidating effects of dilution on rheological parameters and therapeutic potential of dermal fillers from a biological perspective, with emphasis on autologous bioactive solutions such as PRP. Integration of PRP may enhance viscoelastic properties of the filler while minimizing immunogenic risks. Moreover, such combinations could provide the formulation with significant biostimulatory potential, promoting accelerated tissue regeneration, extracellular matrix synthesis, and neovascularization. Such integrative strategies may reinforce the physical resilience of dermal fillers and potentiate their role in tissue repair and remodeling.

Statements

Author contributions

EA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

EA is the Scientific Director of BTI Biotechnology Institute and RT and MA are scientists at BTI Biotechnology Institute, a dental implant company that investigates in the fields of oral implantology and PRGF-Endoret® technology.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors confirm that the manuscript was refined using AI-assisted copy-editing tools (GPT-5 mini) to enhance readability, correct grammar/spelling, and improve stylistic flow. Such interventions were exclusively editorial and did not involve any generative content creation, data analysis, interpretation, or authorship. All final edits were reviewed, approved, and remain the original work of the authors, who take sole responsibility for the scientific content, methodology, and conclusions.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Wang Y Jang YY . From cells to organs: the present and future of regenerative medicine.Adv Exp Med Biol. (2022) 1376:135–49. 10.1007/5584_2021_657

2.

Dos Santos RG Santos GS Alkass N Chiesa TL Azzini GO da Fonseca LF et al The regenerative mechanisms of platelet-rich plasma: a review. Cytokine. (2021) 144:155560. 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155560

3.

Pavlovic V Ciric M Jovanovic V Stojanovic P . Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components.Open Med. (2016) 11:242–7. 10.1515/med-2016-0048

4.

Vladulescu D Scurtu LG Simionescu AA Scurtu F Popescu MI Simionescu O . Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in dermatology: cellular and molecular mechanisms of action.Biomedicines. (2023) 12:7. 10.3390/biomedicines12010007

5.

Ballin AC Brandt FS Cazzaniga A . Dermal fillers: an update.Am J Clin Dermatol. (2015) 16:271–83. 10.1007/s40257-015-0135-7

6.

Almukhadeb E Binkhonain F Alkahtani A Alhunaif S Altukhaim F Alekrish K . Dermal fillers in the treatment of acne scars: a review.Ann Dermatol. (2023) 35:400–7. 10.5021/ad.22.230

7.

Sturm LP Cooter RD Mutimer KL Graham JC Maddern GJ . A systematic review of permanent and semipermanent dermal fillers for HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy.AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2009) 23:699–714. 10.1089/apc.2008.0230

8.

Mundada P Kohler R Boudabbous S Toutous Trellu L Platon A Becker M . Injectable facial fillers: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at MRI and PET CT.Insights Imaging. (2017) 8:557–72. 10.1007/s13244-017-0575-0

9.

Kim JH Kwon TR Lee SE Jang YN Han HS Mun SK et al Comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of novel hyaluronic acid-polynucleotide complex dermal filler. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:5127. 10.1038/s41598-020-61952-w

10.

Al-Ghanim K Richards R Cohen S . A practical guide to selecting facial fillers.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2023) 22:3232–6. 10.1111/jocd.15867

11.

Choi MS . Basic rheology of dermal filler.Arch Plast Surg. (2020) 47:301–4. 10.5999/aps.2020.00731

12.

Bentkover SH . The biology of facial fillers.Facial Plast Surg. (2009) 25:73–85. 10.1055/s-0029-1220646

13.

Liu MH Beynet DP Gharavi NM . Overview of deep dermal fillers.Facial Plast Surg. (2019) 35:224–9. 10.1055/s-0039-1688843

14.

Sánchez-Carpintero I Candelas D Ruiz-Rodríguez R . Materiales de relleno: tipos, indicaciones y complicaciones [Dermal fillers: types, indications, and complications].Actas Dermosifiliogr. (2010) 101:381–93. 10.1016/s1578-2190(10)70660-0Spanish.

15.

Fagien S Klein AW . A brief overview and history of temporary fillers: evolution, advantages, and limitations.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2007) 120(6 Suppl):8S–16S. 10.1097/01.prs.0000248788.97350.18

16.

Broder KW Cohen SR . An overview of permanent and semipermanent fillers.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2006) 118(3 Suppl):7S–14S. 10.1097/01.prs.0000234900.26676.0b

17.

Witmanowski H Błochowiak K . Another face of dermal fillers.Postepy Dermatol Alergol. (2020) 37:651–9. 10.5114/ada.2019.82859

18.

Amiri R Khalili M Iranmanesh B Ahramiyanpour N Karvar M Aflatoonian M . The innovative application of autologous biofillers in aesthetic dermatology.Ital J Dermatol Venerol. (2023) 158:321–7. 10.23736/S2784-8671.23.07485-6

19.

Clark NW Pan DR Barrett DM . Facial fillers: relevant anatomy, injection techniques, and complications.World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2023) 9:227–35. 10.1002/wjo2.126

20.

Hirose Y Fujita C Hyoudou T Inoue E Inoue H . Skin rejuvenation using autologous cultured fibroblast grafting.Cureus. (2024) 16:e75405. 10.7759/cureus.75405

21.

Godfrey L Martínez-Escribano J Roo E Pino A Anitua E . Plasma rich in growth factor gel as an autologous filler for facial volume restoration.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2020) 19:2552–9. 10.1111/jocd.13322

22.

Cheng H Li J Zhao Y Xia X Li Y . In vivo assessment of plasma gel: regenerative potential and limitations as a filler.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2025) 24:e16765. 10.1111/jocd.16765

23.

Christodoulou S Tzamalis A Tsinopoulos I Ziakas N . Surgical and non-surgical approach for tear trough correction: fat repositioning versus hyaluronic acid fillers.J Pers Med. (2024) 14:1096. 10.3390/jpm14111096

24.

Diesch S Frank K Brébant V Bohusch S Brix E Zeng R et al Subject-Reported satisfaction after cell-enriched lipotransfer (CELT) for lip augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2025) 49:5111–9. 10.1007/s00266-025-04875-z

25.

Wanitphakdeedecha R Ng JNC Phumariyapong P Nokdhes YN Patthamalai P Tantrapornpong P et al pilot study comparing the efficacy of autologous cultured fibroblast injections with hyaluronic acid fillers for treating nasolabial folds. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:6616. 10.1038/s41598-023-33786-9

26.

Nassar AH Dorizas AS Sadick NS . Autologous skin fillers. In: DraelosZDeditor.Aesthetic Rejuvenation: A Regional Approach.Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2022). p. 719–27. 10.1002/9781119676881.ch47

27.

Fisher SM Borab Z Weir D Rohrich RJ . The emerging role of biostimulators as an adjunct in facial rejuvenation: a systematic review.J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. (2024) 92:118–29. 10.1016/j.bjps.2024.02.069

28.

Haddad S Galadari H Patil A Goldust M Al Salam S Guida S . Evaluation of the biostimulatory effects and the level of neocollagenesis of dermal fillers: a review.Int J Dermatol. (2022) 61:1284–8. 10.1111/ijd.16229

29.

Gilbert E Hui A Waldorf HA . The basic science of dermal fillers: past and present Part I: background and mechanisms of action.J Drugs Dermatol. (2012) 11:1059–68.

30.

Trotzier C Sequeira I Auxenfans C Mojallal AA . Fat graft retention: adipose tissue, adipose-derived stem cells, and aging.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2023) 151:420e-431e. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009918

31.

Libby TJ Williams RF El Habr C Tinklepaugh A Ciocon D . Mixing of injectable fillers: a national survey.Dermatol Surg. (2019) 45:117–23. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001631

32.

McCarthy AD Soares DJ Chandawarkar A El-Banna R de Lima Faria GE Hagedorn N . Comparative rheology of hyaluronic acid fillers, poly-l-lactic acid, and varying dilutions of calcium hydroxylapatite.Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2024) 12:e6068. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000006068

33.

McCarthy AD Soares DJ Chandawarkar A El-Banna R Hagedorn N . Dilutional rheology of radiesse: implications for regeneration and vascular safety.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2024) 23:1973–84. 10.1111/jocd.16216

34.

Chernoff G . Combining topical dermal infused exosomes with injected calcium hydroxylapatite for enhanced tissue biostimulation.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2023) 22(Suppl 1):15–27. 10.1111/jocd.15695

35.

Khalifian S McCarthy AD Yoelin SG . Hyperdiluting calcium hydroxylapatite with platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronidase for improving neck laxity and wrinkle severity.Cureus. (2024) 16:e63969. 10.7759/cureus.63969

36.

Anitua E . Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants.Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. (1999) 14:529–35.

37.

Herrada-Manchón H Fernández MA Aguilar E . Essential guide to hydrogel rheology in extrusion 3d printing: how to measure it and why it matters?Gels. (2023) 9:517. 10.3390/gels9070517

38.

Brust M Schaefer C Doerr R Pan L Garcia M Arratia PE et al Rheology of human blood plasma: viscoelastic versus Newtonian behavior. Phys Rev Lett. (2013) 110:078305. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.078305

39.

Mitra H Jayaram P Bratsman A Gabel T Alba K . Characterization and rheology of platelet-rich plasma.J Rheol. (2020) 64:1017–34. 10.1122/1.5127743

40.

Rodrigues T Mota R Gales L Campo-Deaño L . Understanding the complex rheology of human blood plasma.J Rheol. (2022) 66:761–74. 10.1122/8.0000442

41.

Cavallo C Roffi A Grigolo B Mariani E Pratelli L Merli G et al Platelet-Rich plasma: the choice of activation method affects the release of bioactive molecules. Biomed Res Int. (2016) 2016:6591717. 10.1155/2016/6591717

42.

Huber SC Cunha Júnior JL Montalvão S da Silva LQ Paffaro AU da Silva FA et al In vitro study of the role of thrombin in platelet rich plasma (PRP) preparation: utility for gel formation and impact in growth factors release. J Stem Cells Regen Med. (2016) 12:2–9. 10.46582/jsrm.1201002

43.

Jalowiec JM D’Este M Bara JJ Denom J Menzel U Alini M et al An in vitro investigation of platelet-rich plasma-gel as a cell and growth factor delivery vehicle for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. (2016) 22:49–58. 10.1089/ten.TEC.2015.0223

44.

Perinelli DR Bonacucina G Pucciarelli S Cespi M Serri E Polzonetti V et al Rheological properties and growth factors content of platelet-rich plasma: relevance in veterinary biomedical treatments. Biomedicines. (2020) 8:429. 10.3390/biomedicines8100429

45.

Toyoda T Isobe K Tsujino T Koyata Y Ohyagi F Watanabe T et al Direct activation of platelets by addition of CaCl2 leads coagulation of platelet-rich plasma. Int J Implant Dent. (2018) 4:23. 10.1186/s40729-018-0134-6

46.

Perez AG Rodrigues AA Luzo AC Lana JF Belangero WD Santana MH . Fibrin network architectures in pure platelet-rich plasma as characterized by fiber radius and correlated with clotting time.J Mater Sci Mater Med. (2014) 25:1967–77. 10.1007/s10856-014-5235-z

47.

Fufa D Shealy B Jacobson M Kevy S Murray MM . Activation of platelet-rich plasma using soluble type I collagen.J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2008) 66:684–90. 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.635

48.

Chen JL Cheng WJ Chen CC Huang SC Chen CPC Suputtitada A . Thermal oscillation changes the liquid-form autologous platelet-rich plasma into paste-like form.Biomed Res Int. (2022) 2022:6496382. 10.1155/2022/6496382

49.

Zhao X Xu H Ye G Li C Wang L Hu F et al Temperature-activated PRP–cryogel for long-term osteogenesis of adipose-derived stem cells to promote bone repair. Mater Chem Front. (2021) 5:396–405. 10.1039/D0QM00493F

50.

Nakamura M Masuki H Kawabata H Watanabe T Watanabe T Tsujino T et al Plasma gel made of platelet-poor plasma: in vitro verification as a carrier of polyphosphate. Biomedicines. (2023) 11:2871. 10.3390/biomedicines11112871

51.

Navarro R Pino A Martínez-Andrés A Garrigós E Sánchez ML Gallego E et al Combined therapy with endoret-gel and plasma rich in growth factors vs endoret-gel alone in the management of facial rejuvenation: a comparative study. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2020) 19:2616–26. 10.1111/jocd.13661

52.

Kaczuba E Fakih-Gomez N Kadouch J Bartsch R Pecora C Yutskovskaya YA et al Exploring the rheology and clinical potential of calcium hydroxylapatite–hyaluronic acid hybrids. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2025) 24:e70473. 10.1111/jocd.70473

53.

Russo F D’Este M Vadalà G Cattani C Papalia R Alini M et al Platelet rich plasma and hyaluronic acid blend for the treatment of osteoarthritis: rheological and biological evaluation. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0157048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157048

54.

Vadalà G Russo F Musumeci M D’Este M Cattani C Catanzaro G et al Clinically relevant hydrogel-based on hyaluronic acid and platelet rich plasma as a carrier for mesenchymal stem cells: rheological and biological characterization. J Orthop Res. (2017) 35:2109–16. 10.1002/jor.23509

55.

Xin H Seigneur A Bernardin A Singh-Virk S Singh-Virk A Calderón-Vaca M et al Effect of entrapped and free calcium hydroxyapatite particles on rheological properties of hyaluronic acid–calcium hydroxyapatite composite hydrogels. ACS Omega. (2025) 10:48242–56. 10.1021/acsomega.5c05147

56.

Soares DJ Fedorova J Zhang Y Chandawarkar A Bowhay A Blevins L et al Arterioembolic characteristics of differentially diluted CaHA-CMC gels within an artificial macrovascular perfusion model. Aesthet Surg J. (2025) 45:645–53. 10.1093/asj/sjaf028

57.

Sundaram H Voigts B Beer K Meland M . Comparison of the rheological properties of viscosity and elasticity in two categories of soft tissue fillers: calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid.Dermatol Surg. (2010) 36(Suppl 3):1859–1865. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01743.x

58.

Heitmiller K Ring C Saedi N . Rheologic properties of soft tissue fillers and implications for clinical use.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2021) 20:28–34. 10.1111/jocd.13487

59.

Pierre S Liew S Bernardin A . Basics of dermal filler rheology.Dermatol Surg. (2015) 41(Suppl 1):S120–6. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000334

60.

Lim TS Wanitphakdeedecha R Yi KH . Exploring facial overfilled syndrome from the perspective of anatomy and the mismatched delivery of fillers.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2024) 23:1964–8. 10.1111/jocd.16244

61.

Snozzi P van Loghem JAJ . Complication management following rejuvenation procedures with hyaluronic acid fillers-an algorithm-based approach.Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2018) 6:e2061. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002061

62.

Chao YY Kim JW Kim J Ko H Goldie K . Hyperdilution of CaHA fillers for the improvement of age and hereditary volume deficits in East Asian patients.Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2018) 11:357–63. 10.2147/CCID.S159752

63.

Colon J Mirkin S Hardigan P Elias MJ Jacobs RJ . Adverse events reported from hyaluronic acid dermal filler injections to the facial region: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Cureus. (2023) 15:e38286. 10.7759/cureus.38286

64.

Funt D Pavicic T . Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches.Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2013) 6:295–316. 10.2147/CCID.S50546

65.

Hong GW Hu H Chang K Park Y Lee KWA Chan LKW et al Review of the adverse effects associated with dermal filler treatments: part I nodules. granuloma, and migration. Diagnostics. (2024) 14:1640. 10.3390/diagnostics14151640

66.

Hong GW Hu H Chang K Park Y Lee KWA Chan LKW et al Adverse effects associated with dermal filler treatments: part II vascular complication. Diagnostics. (2024) 14:1555. 10.3390/diagnostics14141555

67.

Kadouch JA . Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2017) 16:152–61. 10.1111/jocd.12326

68.

McCarthy AD van Loghem J Martinez KA Aguilera SB Funt D . A Structured approach for treating calcium hydroxylapatite focal accumulations.Aesthet Surg J. (2024) 44:869–79. 10.1093/asj/sjae031

69.

Pavicic T . Calcium hydroxylapatite filler: an overview of safety and tolerability.J Drugs Dermatol. (2013) 12:996–100.

70.

Amselem M . Radiesse(®): a novel rejuvenation treatment for the upper arms.Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2015) 9:9–14. 10.2147/CCID.S93137

71.

Casabona G Pereira G . Microfocused ultrasound with visualization and calcium hydroxylapatite for improving skin laxity and cellulite appearance.Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2017) 5:e1388. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001388

72.

Goldie K Peeters W Alghoul M Butterwick K Casabona G Chao YYY et al Global consensus guidelines for the injection of diluted and hyperdiluted calcium hydroxylapatite for skin tightening. Dermatol Surg. (2018) 44(Suppl 1):S32–41. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001685

73.

Massidda E . Starting point for protocols on the use of hyperdiluted calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse®) for optimizing age-related biostimulation and rejuvenation of face, neck, décolletage and hands: a case series report.Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2023) 16:3427–39. 10.2147/CCID.S420068

74.

Yutskovskaya YA Kogan EA . Improved neocollagenesis and skin mechanical properties after injection of diluted calcium hydroxylapatite in the neck and décolletage:a pilot study.J Drugs Dermatol. (2017) 16:68–74.

75.

Lorenc ZP Bass LM Fitzgerald R Goldberg DJ Graivier MH . Physiochemical characteristics of calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA).Aesthet Surg J. (2018) 38(Suppl_1):S8–12. 10.1093/asj/sjy011

76.

Loghem JV Yutskovskaya YA Werschler W . Calcium hydroxylapatite over a decade of experience.J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. (2015) 8:38–49.

77.

Meland M Groppi C Lorenc ZP . Rheological properties of calcium hydroxylapatite with integral lidocaine.J Drugs Dermatol. (2016) 15:1107–10.

78.

de Almeida AT Figueredo V da Cunha ALG Casabona G Costa de Faria JR Alves EV et al Consensus recommendations for the use of hyperdiluted calcium hydroxyapatite (Radiesse) as a Face and body biostimulatory agent. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2019) 7:e2160. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002160

79.

Corduff N Chen JF Chen YH Choi HS Goldie K Lam Y et al Pan-Asian consensus on calcium hydroxyapatite for skin biostimulation, contouring, and combination treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. (2021) 14:E76–85.

80.

Green JB Biesman BS Hill DA Kwok GP Levin M Sergeeva D . Panfacial approach to rejuvenation using calcium hydroxylapatite: a case series illustrating calcium hydroxylapatite versatility through dilution and a multilayered treatment approach.Aesthet Surg J Open Forum. (2024) 7:ojae119. 10.1093/asjof/ojae119

81.

Lorenc ZP Black JM Cheung JS Chiu A Del Campo R Durkin AJ et al Skin tightening with hyperdilute CaHA: dilution practices and practical guidance for clinical practice. Aesthet Surg J. (2022) 42:N29–37. 10.1093/asj/sjab269

82.

Busso M Voigts R . An investigation of changes in physical properties of injectable calcium hydroxylapatite in a carrier gel when mixed with lidocaine and with lidocaine/epinephrine.Dermatol Surg. (2008) 34(Suppl 1):S16–23; discussion S24. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34238.x

83.

Van Loghem JAJ . Use of calcium hydroxylapatite in the upper third of the face: retrospective analysis of techniques, dilutions and adverse events.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2018) 17:1025–30. 10.1111/jocd.12733

84.

Dal Col V Marchi C Ribas F Franzen Matte B Medeiros H Domenici de Oliveira B et al In vitro comparative study of calcium hydroxyapatite (Stiim): conventional saline dilution versus poly-micronutrient dilution. Cureus. (2025) 17:e80344. 10.7759/cureus.80344

85.

Nowag B Casabona G Kippenberger S Zöller N Hengl T . Calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres activate fibroblasts through direct contact to stimulate neocollagenesis.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2023) 22:426–32. 10.1111/jocd.15521

86.

Felix Bravo B Bezerra de Menezes Penedo L de Melo Carvalho R Amante Miot H Calomeni Elias M . Improvement of facial skin laxity by a combined technique with hyaluronic acid and calcium hydroxylapatite fillers: a clinical and ultrasonography analysis.J Drugs Dermatol. (2022) 21:102–6. 10.36849/JDD.2022.6333

87.

Samadi P Sheykhhasan M Khoshinani HM . The use of platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic and regenerative medicine: a comprehensive review.Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2019) 43:803–14. 10.1007/s00266-018-1293-9

88.

Currie E Granata B Goodman G Rudd A Wallace K Rivkin A et al The use of hyaluronidase in aesthetic practice: a comparative study of practitioner usage in elective and emergency situations. Aesthet Surg J. (2024) 44:647–57. 10.1093/asj/sjae009

89.

Wollina U Goldman A Kocic H Andjelkovic T Bogdanovic D Kokić IK . Impurities in hyaluronic acid dermal fillers? a narrative review on nonanimal cross-linked fillers.Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. (2024) 26:190–4. 10.1089/fpsam.2023.0294

90.

Salih ARC Farooqi HMU Amin H Karn PR Meghani N Nagendran S . Hyaluronic acid: comprehensive review of a multifunctional biopolymer.Futur J Pharm Sci. (2024) 10:63. 10.1186/s43094-024-00636-y

91.

Wongprasert P Dreiss CA Murray G . Evaluating hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a critique of current characterization methods.Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15453. 10.1111/dth.15453

92.

Fagien S Bertucci V von Grote E Mashburn JH . Rheologic and physicochemical properties used to differentiate injectable hyaluronic acid filler products.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2019) 143:707e–20e. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005429

93.

Gutowski KA . Hyaluronic acid fillers: science and clinical uses.Clin Plast Surg. (2016) 43:489–96. 10.1016/j.cps.2016.03.016

94.

Ramos-E-Silva M Fonteles LA Lagalhard CS Fucci-da-Costa AP . STYLAGE®: a range of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers containing mannitol. Physical properties and review of the literature.Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2013) 6:257–61. 10.2147/CCID.S35251

95.

Rzany B Sulovsky M Sattler G Cecerle M Grablowitz D . Long-term performance and safety of princess volume plus lidocaine for midface augmentation: the primavera clinical study.Aesthet Surg J. (2024) 44:203–15. 10.1093/asj/sjad230

96.

Zhou R Yu M . The effect of local hyaluronic acid injection on skin aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2025) 24:e16760. 10.1111/jocd.16760

97.

Alijotas-Reig J Fernández-Figueras MT Puig L . Late-onset inflammatory adverse reactions related to soft tissue filler injections.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2013) 45:97–108. 10.1007/s12016-012-8348-5

98.

Lemperle G Gauthier-Hazan N Wolters M Eisemann-Klein M Zimmermann U Duffy DM . Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 1. possible causes.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2009) 123:1842–63. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818236d7

99.

Lee JH Kim J Lee YN Choi S Lee YI Suk J et al The efficacy of intradermal hyaluronic acid filler as a skin quality booster: a prospective, single-center, single-arm pilot study. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2024) 23:409–16. 10.1111/jocd.15944

100.

Ulusal BG . Platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid - an efficient biostimulation method for face rejuvenation.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2017) 16:112–9. 10.1111/jocd.12271

101.

Marinescu EA Nica O Cojocaru A Liliac IM Ciurea AM Ciurea ME . Treatment of skin defects with PRP enriched with hyaluronic acid - histological aspects in rat model.Rom J Morphol Embryol. (2022) 63:439–47. 10.47162/RJME.63.2.15

102.

Hersant B SidAhmed-Mezi M Aboud C Niddam J Levy S Mernier T et al Synergistic effects of autologous platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid injections on facial skin rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. (2021) 41:N854–65. 10.1093/asj/sjab061

103.

Hersant B SidAhmed-Mezi M Niddam J La Padula S Noel W Ezzedine K et al Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma combined with hyaluronic acid on skin facial rejuvenation: a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2017) 77:584–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.022

104.

Pirrello R Verro B Grasso G Ruscitti P Cordova A Giacomelli R et al Hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, a new therapeutic alternative for scleroderma patients: a prospective open-label study. Arthritis Res Ther. (2019) 21:286. 10.1186/s13075-019-2062-0

105.

Lee H Yoon K Lee M . Full-face augmentation using Tissuefill mixed with platelet-rich plasma: “Q.O.Fill”.J Cosmet Laser Ther. (2019) 21:166–70. 10.1080/14764172.2018.1502449

106.

Belk JW Kraeutler MJ Houck DA Goodrich JA Dragoo JL McCarty EC . Platelet-Rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.Am J Sports Med. (2021) 49:249–60. 10.1177/0363546520909397

107.

Qiao X Yan L Feng Y Li X Zhang K Lv Z et al Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, and PRP and combination therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2023) 24:926. 10.1186/s12891-023-06925-6

108.

Santiago MS Doria FM Morais Sirqueira Neto J Fontes FF Porto ES Aidar FJ et al Platelet-rich plasma with versus without hyaluronic acid for hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2025) 13:1545431. 10.3389/fbioe.2025.1545431

109.

Ramos-Torrecillas J García-Martínez O De Luna-Bertos E Ocaña-Peinado FM Ruiz C . Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid for the treatment and care of pressure ulcers.Biol Res Nurs. (2015) 17:152–8. 10.1177/1099800414535840

110.

Amiri M Meçani R Llanaj E Niehot CD Phillips TL Goldie K et al Calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) and aesthetic outcomes: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:1686. 10.3390/jcm13061686

111.

Sanchez-Rico GA Canto SBA . Three calcium hydroxylapatite-based dermal fillers marketed in Mexico: comparison of particle size and shape using electron microscopy.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2025) 24:e70100. 10.1111/jocd.70100

112.

Braz A Colucci L Macedo de Oliveira L Monteiro G Ormiga P Wanick F et al A retrospective analysis of safety in participants treated with a hybrid hyaluronic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite filler. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2024) 12:e5622. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000005622

113.

Fakih-Gomez N Kadouch J . Combining calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid fillers for aesthetic indications: efficacy of an innovative hybrid filler.Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2022) 46:373–81. 10.1007/s00266-021-02479-x

114.

Jeong SH Fan YF Baek JU Song J Choi TH Kim SW et al Long-lasting and bioactive hyaluronic acid-hydroxyapatite composite hydrogels for injectable dermal fillers: physical properties and in vivo durability. J Biomater Appl. (2016) 31:464–74. 10.1177/0885328216648809

115.

Guida S Longhitano S Spadafora M Lazzarotto A Farnetani F Zerbinati N et al Hyperdiluted calcium hydroxylapatite for the treatment of skin laxity of the neck. Dermatol Ther. (2021) 34:e15090. 10.1111/dth.15090

116.

Nowag B Schäfer D Hengl T Corduff N Goldie K . Biostimulating fillers and induction of inflammatory pathways: a preclinical investigation of macrophage response to calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L lactic acid.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2024) 23:99–106. 10.1111/jocd.15928

117.

Aguilera SB McCarthy A Khalifian S Lorenc ZP Goldie K Chernoff WG . The role of calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) as a regenerative aesthetic treatment: a narrative review.Aesthet Surg J. (2023) 43:1063–90. 10.1093/asj/sjad173

118.

Botsali A Erbil H Eşme P Gamsızkan M Aksoy AO Caliskan E . The comparative dermal stimulation potential of constant-volume and constant-amount diluted calcium hydroxylapatite injections versus the concentrated form.Dermatol Surg. (2023) 49:871–6. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003874

119.

Amaral VM Ramos HHA Cavallieri FA Muniz M Muzy G de Almeida AT . An innovative treatment using calcium hydroxyapatite for non-surgical facial rejuvenation: the vectorial-lift technique.Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2024) 48:3206–15. 10.1007/s00266-024-04071-5

120.

Pavicic T Sattler G Fischer T Dirschka T Kerscher M Gauglitz G et al Calcium hydroxyapatite filler with integral lidocaine CaHA (+) for soft tissue augmentation: results from an open-label multicenter clinical study. J Drugs Dermatol. (2022) 21:481–7. 10.36849/JDD.6737

121.

Goldman MP Moradi A Gold MH Friedmann DP Alizadeh K Adelglass JM et al Calcium hydroxylapatite dermal filler for treatment of dorsal hand volume loss: results from a 12-month, multicenter, randomized, blinded trial. Dermatol Surg. (2018) 44:75–83. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001203

122.

Figueredo VO Miot HA Soares Dias J Nunes GJB Barros de Souza M Bagatin E . Efficacy and safety of 2 injection techniques for hand biostimulatory treatment with diluted calcium hydroxylapatite.Dermatol Surg. (2020) 46(Suppl 1):S54–61. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002334

123.

Durairaj K Baker O Yambao M Linnemann-Heath J Shirinyan A . Safety and efficacy of diluted calcium hydroxylapatite for the treatment of cellulite dimpling on the buttocks: results from an open-label, investigator-initiated, single-center, prospective clinical study.Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2024) 48:1797–806. 10.1007/s00266-023-03815-z

124.

Fabi SG Alhaddad M Boen M Goldman M . Prospective clinical trial evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of calcium hydroxylapatite for chest rejuvenation.J Drugs Dermatol. (2021) 20:534–7. 10.36849/JDD.5680

125.

Pavicic T Kerscher M Kuhne U Heide I Dersch H Odena G et al A prospective, multicenter, evaluator-blinded, randomized study of diluted calcium hydroxylapatite to treat decollete wrinkles. J Drugs Dermatol. (2024) 23:551–6. 10.36849/JDD.8261

126.

Hevia O . A retrospective review of calcium hydroxylapatite for correction of volume loss in the infraorbital region.Dermatol Surg. (2009) 35:1487–94. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01262.x

127.

Rovatti PP Pellacani G Guida S . Hyperdiluted calcium hydroxylapatite 1: 2 for mid and lower facial skin rejuvenation: efficacy and safety.Dermatol Surg. (2020) 46:e112–7. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002375

128.

Yutskovskaya YA Sergeeva AD Kogan EA . Combination of calcium hydroxylapatite diluted with normal saline and microfocused ultrasound with visualization for skin tightening.J Drugs Dermatol. (2020) 19:405–11. 10.36849/JDD.2020.4625

129.

Somenek M . Hyperdilute calcium hydroxylapatite for the treatment of perioral rhytids: a pilot study.Aesthet Surg J Open Forum. (2024) 6:ojae021. 10.1093/asjof/ojae021

130.

Casabona G Marchese P . Calcium hydroxylapatite combined with microneedling and ascorbic acid is effective for treating stretch marks.Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2017) 5:e1474. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001474

131.

Lapatina NG Pavlenko T . Diluted calcium hydroxylapatite for skin tightening of the upper arms and abdomen.J Drugs Dermatol. (2017) 16:900–6.

132.

Berlin AL Hussain M Goldberg DJ . Calcium hydroxylapatite filler for facial rejuvenation: a histologic and immunohistochemical analysis.Dermatol Surg. (2008) 34(Suppl 1):S64–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34245.x

133.

Coleman KM Voigts R DeVore DP Termin P Coleman WP III . Neocollagenesis after injection of calcium hydroxylapatite composition in a canine model.Dermatol Surg. (2008) 34(Suppl 1):S53–5. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34243.x

134.

Marmur ES Phelps R Goldberg DJ . Clinical, histologic and electron microscopic findings after injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler.J Cosmet Laser Ther. (2004) 6:223–6. 10.1080/147641704100003048

135.

Yutskovskaya Y Kogan E Leshunov E . A randomized, split-face, histomorphologic study comparing a volumetric calcium hydroxylapatite and a hyaluronic acid-based dermal filler.J Drugs Dermatol. (2014) 13:1047–52.

136.

Manole CG Soare C Ceafalan LC Voiculescu VM . Platelet-Rich plasma in dermatology: new insights on the cellular mechanism of skin repair and regeneration.Life. (2023) 14:40. 10.3390/life14010007

137.

Phoebe LKW Lee KWA Chan LKW Hung LC Wu R Wong S et al Use of platelet rich plasma for skin rejuvenation. Skin Res Technol. (2024) 30:e13714. 10.1111/srt.13714

138.

Arruda S Prieto V Shea C Swearingen A Elmadany Z Sadick NSA . Clinical histology study evaluating the biostimulatory activity longevity of injectable poly-l-lactic acid for facial rejuvenation.J Drugs Dermatol. (2024) 23:729–34. 10.36849/JDD.8057

139.

Oh S Lee JH Kim HM Batsukh S Sung MJ Lim TH et al Poly-L-Lactic acid fillers improved dermal collagen synthesis by modulating M2 macrophage polarization in aged animal skin. Cells. (2023) 12:1320. 10.3390/cells12091320

140.

Christen MO . Collagen stimulators in body applications: a review focused on poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA).Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2022) 15:997–1019. 10.2147/CCID.S359813

141.

Kwon TR Han SW Yeo IK Kim JH Kim JM Hong JY et al Biostimulatory effects of polydioxanone, poly-d, l lactic acid, and polycaprolactone fillers in mouse model. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2019) 18:1002–8. 10.1111/jocd.12950

142.

Alessio R Rzany B Eve L Grangier Y Herranz P Olivier-Masveyraud F et al European expert recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. (2014) 13:1057–66.

143.

Magacho-Vieira FN Vieira AO Soares A Jr. Alvarenga HCL de Oliveira Junior IRA Daher JAC et al Consensus recommendations for the reconstitution and aesthetic use of poly-D,L-lactic acid microspheres. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2024) 17:2755–65. 10.2147/CCID.S497691

144.

Narins RS Baumann L Brandt FS Fagien S Glazer S Lowe NJ et al A randomized study of the efficacy and safety of injectable poly-L-lactic acid versus human-based collagen implant in the treatment of nasolabial fold wrinkles. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2010) 62:448–62. 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.040

145.

Palm M Mayoral F Rajani A Goldman MP Fabi S Espinoza L et al Chart review presenting safety of injectable PLLA used with alternative reconstitution volume for facial treatments. J Drugs Dermatol. (2021) 20:118–22. 10.36849/JDD.5631

146.

Palm M Weinkle S Cho Y LaTowsky B Prather H . A randomized study on PLLA using higher dilution volume and immediate use following reconstitution.J Drugs Dermatol. (2021) 20:760–6. 10.36849/JDD.6034

147.

Leonardi F Angelone M Biacca C Battaglia B Pecorari L Conti V et al Platelet-rich plasma combined with a sterile 3D polylactic acid scaffold for postoperative management of complete hoof wall resection for keratoma in four horses. J Equine Vet Sci. (2020) 92:103178. 10.1016/j.jevs.2020.103178

148.

Yao D Hao DF Zhao F Hao XF Feng G Chu WL et al [Effects of platelet-rich plasma combined with polylactic acid/polycaprolactone on healing of pig deep soft tissue defect caused by fragment injury]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. (2019) 35:31–9. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-2587.2019.01.007

149.

Deshmukh SN Dive AM Moharil R Munde P . Enigmatic insight into collagen.J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. (2016) 20:276–83. 10.4103/0973-029X.185932

150.

Salvatore L Natali ML Brunetti C Sannino A Gallo N . An update on the clinical efficacy and safety of collagen injectables for aesthetic and regenerative medicine applications.Polymers. (2023) 15:1020. 10.3390/polym15041020

151.

Buck DW II Alam M Kim JY . Injectable fillers for facial rejuvenation: a review.J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. (2009) 62:11–8. 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.036

152.

Charriere G Bejot M Schnitzler L Ville G Hartmann DJ . Reactions to a bovine collagen implant. clinical and immunologic study in 705 patients.J Am Acad Dermatol. (1989) 21:1203–8. 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70330-3

153.

Ellingsworth LR DeLustro F Brennan JE Sawamura S McPherson J . The human immune response to reconstituted bovine collagen.J Immunol. (1986) 136:877–82.

154.

Lynn AK Yannas IV Bonfield W . Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen.J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. (2004) 71:343–54. 10.1002/jbm.b.30096

155.

Parenteau-Bareil R Gauvin R Berthod F . Collagen-Based biomaterials for tissue engineering applications.Materials. (2010) 3:1863–87. 10.3390/ma3031863

156.

Weinkle S . Efficacy and tolerability of admixing 0.3% lidocaine with Dermicol-P35 27G for the treatment of nasolabial folds.Dermatol Surg. (2010) 36:316–20. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01439.x

157.

Yang CY Chang YC Tai HC Liao YH Huang YH Hui RC et al Evaluation of collagen dermal filler with lidocaine for the correction of nasolabial folds: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2024) 17:1621–31. 10.2147/CCID.S447760

158.

Lemperle G Knapp TR Sadick NS Lemperle SM . ArteFill permanent injectable for soft tissue augmentation: I. mechanism of action and injection techniques.Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2010) 34:264–72. 10.1007/s00266-009-9413-1

159.

Lorenc ZP Pilcher B McArthur T Patel N . Rheology of polymethylmethacrylate-collagen gel filler: physiochemical properties and clinical applications.Aesthet Surg J. (2021) 41:N88–93. 10.1093/asj/sjaa31464

160.

Gold MH Sadick NS . Optimizing outcomes with polymethylmethacrylate fillers.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2018) 17:298–304. 10.1111/jocd.12539

161.

Karnik J Baumann L Bruce S Callender V Cohen S Grimes P et al A double-blind, randomized, multicenter, controlled trial of suspended polymethylmethacrylate microspheres for the correction of atrophic facial acne scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2014) 71:77–83. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.034

162.

Mills DC Camp S Mosser S Sayeg A Hurwitz D Ronel D . Malar augmentation with a polymethylmethacrylate-enhanced filler: assessment of a 12-month open-label pilot study.Aesthet Surg J. (2013) 33:421–30. 10.1177/1090820X13480015

163.

Mani N McLeod J Sauder MB Sauder DN Bothwell MR . Novel use of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) microspheres in the treatment of infraorbital rhytids.J Cosmet Dermatol. (2013) 12:275–80. 10.1111/jocd.12065

164.

Rivkin A . A prospective study of non-surgical primary rhinoplasty using a polymethylmethacrylate injectable implant.Dermatol Surg. (2014) 40:305–13. 10.1111/dsu.12415

165.

Cohen S Dover J Monheit G Narins R Sadick N Werschler WP et al Five-Year safety and satisfaction study of PMMA-collagen in the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. (2015) 41(Suppl 1):S302–13. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000542

166.

Smith KC Melnychuk M . Five percent lidocaine cream applied simultaneously to the skin and mucosa of the lips creates excellent anesthesia for filler injections.Dermatol Surg. (2005) 31(11 Pt 2):1635–7. 10.2310/6350.2005.31253

167.

Houdek MT Wyles CC Stalboerger PG Terzic A Behfar A Moran SL . Collagen and fractionated platelet-rich plasma scaffold for dermal regeneration.Plast Reconstr Surg. (2016) 137:1498–506. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002094

168.

Li Z Li Q Ahmad A Yue Z Wang H Wu G . Highly concentrated collagen/chondroitin sulfate scaffold with platelet-rich plasma promotes bone-exposed wound healing in porcine.Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2024) 12:1441053. 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1441053

169.