Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic sciatica, frequently attributable to lumbar disc herniation, imposes substantial burdens on patients’ quality of life and healthcare systems. Conventional interventions, including pharmacotherapy and physical therapy, are widely employed yet constrained by limited efficacy, necessitating the exploration of complementary modalities such as acupuncture. This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published over the past decade (2015.05 – 2025.05) to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in alleviating leg pain intensity and improving functional mobility outcomes among patients with chronic sciatica.

Methods:

We searched four databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science) for RCTs on acupuncture versus control (sham acupuncture, standard care, or conventional acupuncture). Studies included adults with sciatica from herniated disks, assessed via VAS for pain and ODI for function. Data were pooled using random-effects models with subgroup analyses for heterogeneity. Bias risk was assessed with the Cochrane tool.

Results:

Eleven RCTs (n = 868 participants, predominantly from China) were included. The results demonstrated that acupuncture significantly reduced leg pain VAS scores compared with those of controls (SMD = –1.08, 95% CI: –1.41 to –0.75), with consistent efficacy across the sham acupuncture (SMD = –1.05), standard care (SMD = –1.02), and conventional acupuncture (SMD = –1.12) subgroups. Acupuncture also improved functional disability (ODI: SMD = –0.57, 95% CI: –0.84 to –0.31; 7 studies, n = 621). The results indicate both statistical significance and clinical relevance, supporting acupuncture as an effective intervention.

Discussion:

Acupuncture effectively alleviates pain and aids functional recovery in chronic sciatica, highlighting its role in multidisciplinary pain management. However, methodological limitations in the extant literature necessitate cautious interpretation, and future high-quality RCTs are warranted to strengthen evidence-based clinical implementation.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251067853, identifier (CRD420251067853).

1 Introduction

Chronic sciatica, a frequent complication of lumbar disc herniation, arises from the compression of nerve roots, leading to radiating pain along the sciatic nerve, which is often accompanied by lower limb numbness, muscle weakness, and dysfunction (1–3). The global lifetime incidence of sciatica ranges from approximately 1.6 to 43%, with approximately 10 to 40% of cases progressing to a chronic condition lasting more than 12 weeks (4, 5). While most patients find relief through conservative treatments, research indicates that approximately 45% do not experience significant symptom improvement within 1 year, and 34% may endure pain for more than 2 years, substantially diminishing their quality of life and increasing healthcare demands (6, 7).

Lumbar disc herniation is a major cause of low back pain, sciatica, and radicular leg pain, imposing a burden on individuals and society (8). The etiology of leg pain (sciatica) from lumbar disc herniation primarily involves mechanical compression of the nerve root (9).

Traditional treatments include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants) and physical therapy. In some cases, surgical intervention may be needed. However, these traditional therapies have certain limitations, such as the side effects of the medication and the risks of surgery. Therefore, it is important to find safe and effective alternative therapies. Acupuncture is an important part of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) that aims to treat diseases by stimulating specific acupuncture points to regulate the body’s physiological functions. In recent years, acupuncture has shown potential in the treatment of various painful conditions, including sciatica (10–12). Acupuncture can relieve pain through a variety of mechanisms, such as stimulating the endogenous analgesic system, releasing substances such as endorphins, regulating neuroinflammatory responses and attenuating inflammation in nerve roots (13).

There have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the use of acupuncture for the treatment of sciatica (14–16). However, the available evidence remains controversial due to the quality of the included studies, the heterogeneity of interventions, and the length of follow-up (17). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a high-quality meta-analysis. We focused on the literature published in the past decade to systematically evaluate the latest clinical evidence of acupuncture treatment for sciatica caused by lumbar intervertebral disc herniation.

This study aims to critically evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation through a systematic review and meta-analysis. This study will provide clinicians with a more reliable evidence-based basis and provide a reference for future research directions.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and guidance

The protocol of this study was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), and the registration number was CRD420251067853. This systematic review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (18).

2.2 Search strategy

To ensure the quality of the literature, we systematically searched English electronic databases to identify all relevant randomized controlled trials (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library). The search range ranged from the last decade (2015.05–2025.05). The search was conducted via MeSH vocabulary combinations and the following group terms: (1) acupuncture (acupuncture, electroacupuncture, needle, needling, etc.), (2) sciatica (sciatic nerve pain, sciatic neuralgia, sciatic neuropathy, sciatic pain, etc.), and (3) herniated disk (herniated disc, intervertebral disc herniation, disc herniation, etc.) The detailed search strategies for each database are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

2.3 Study selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.3.1 Inclusion criteria

Patients: Adults aged 18 years and older were diagnosed with sciatica due to a herniated disk, regardless of sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

Interventions: The experimental group received acupuncture treatment, which may include various techniques (e.g., manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture).

Comparisons: The control group received either sham acupuncture, no treatment, or standard care (e.g., physical therapy, medication, conventional acupuncture) for sciatica.

Outcomes: At least one of the following outcomes was reported: pain intensity, functional improvement, and quality of life.

Study Design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies.

2.3.2 Exclusion criteria

Patients: Studies involving participants under 18 years of age or those not diagnosed with sciatica due to the herniated intervertebral disc.

Interventions: Studies that do not specify the type of acupuncture intervention, number of sessions, duration of each session, or total treatment duration.

Comparisons: Studies that did not include a control group receiving sham acupuncture, no treatment, or other standard care.

Outcomes: Studies that do not report on at least one of the specified outcomes.

Study Design: Nonrandomized controlled trials, observational studies, animal studies, case reports, reviews, meta-analyses, or duplicates.

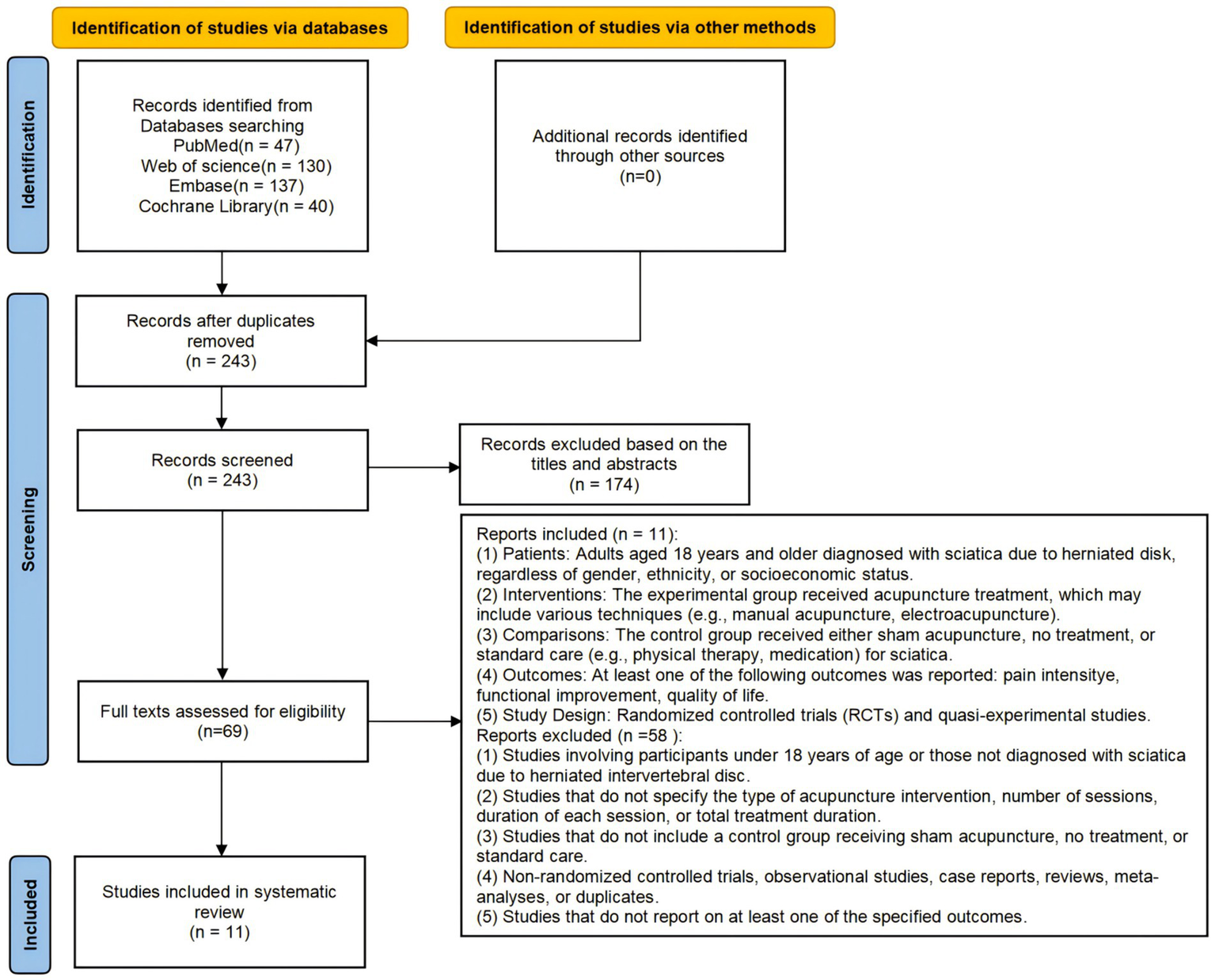

This selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flowchart of study selection.

2.4 Study selection and data extraction

The retrieved records were imported into Endnote, and duplicates were removed. Using a standardized data extraction form, two reviewers (Zhen Qu and Jiangyi Ju) independently extracted detailed information about the included studies, including investigator name, year of publication, study design, sample size, patient characteristics, interventions (e.g., acupuncture points, duration of treatment, frequency), control group interventions, outcome measures, and adverse effects. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third independent reviewer (LiHua Peng). If study data are missing or incomplete, an attempt will be made to contact the authors. Any disputes arising during the data extraction process will also be resolved through discussion or consultation.

2.5 Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (Zhen Qu and Jiangyi Ju) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed via the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool (19). Assessments included bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result. The studies were classified into three levels: low risk, some concern, and high risk.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted via Stata (version 12.0) and R (version 4.5.1) software. Continuous outcomes such as pain intensity visual analog scale (VAS) scores, the functional disability Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) were used as the effect measures, each with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). For dichotomous outcomes, such as the total effective rate, the relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) was employed as the effect measure, as was the 95% CI. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed via the Cochran’s Q statistic and the I2 statistic (20). If I2 ≤ 50% and the p value >0.10, heterogeneity was considered low, and a fixed-effects model was used for the analysis. If I2 > 50% or the p value ≤0.10, significant heterogeneity was deemed present, and a random effects model was employed (20). Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed to explore the potential influence of categorical and continuous variables on the results (21). Publication bias was evaluated qualitatively by visually inspecting funnel plot asymmetry. Given the potential for publication bias, a sensitivity analysis was further conducted via leave-one-out analysis.

2.7 Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis on the basis of the types of control interventions (sham acupuncture, other types of acupuncture, standard care).

3 Results

3.1 Search results

The flow diagram of the screening process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 354 records were retrieved from the search. After removing duplicates, 243 records were screened for potential relevance on the basis of their titles and abstracts. Among these, 174 records were excluded, leaving 69 records for full-text evaluation. Through the screening process, we ultimately included 11 studies (22–32). After full-text assessment, 58 studies were excluded. The primary reason for exclusion was that the interventions in these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria. Additionally, we excluded animal studies, reviews, meta-analyses, case reports and observational studies because they were not randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

This review included 11 studies involving a total of 868 participants. Almost all the studies were conducted in China, with 3 studies (24, 30, 31) being Chinese publications and the remainder being English publications. All studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with one being a multi-center trial (26). The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 30 to 216 participants. All participants in the included trials were required to have a diagnosis of sciatica. All studies reported pain intensity via the VAS score for leg pain, and 7 studies reported the ODI score (22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31). All intervention groups received acupuncture, including acupuncture (22, 25, 26, 28), electroacupuncture (23), and specific acupuncture (24, 27, 29–32). Among the control groups, 4 studies (22, 25, 26, 28) used sham acupuncture, 2 studies (23, 29) used standard care (medication, electrotherapy), and 5 studies (24, 27, 30–32) used conventional acupuncture. Further details of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Author | Publication year | Sample Size | Age, mean (SD), year | Interventions | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture group | Control group | Acupuncture group | Control group | Acupuncture group | Control group | |||

| Li C (22) | 2021 | 37 | 36 | 56.9 (8.3) | 57.3 (9.7) | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | VAS, ODI |

| Zhang X (23) | 2017 | 50 | 50 | 54.3 (12.4) | 51.1 (13.0) | Electroacupuncture | Medium-frequency electrotherapy | NRS, ODI |

| Qiu L (24) | 2016 | 30 | 30 | 43.1 (15.3) | 43.2 (14.3) | Sciatic nerve and routine acupuncture | simple routine acupuncture | VAS, PRI |

| Wei XY (25) | 2024 | 25 | 25 | 60.5 (11.3) | 54.3 (13.2) | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | VAS, ODI, SFBI |

| Tu JF (26) | 2024 | 108 | 108 | 51.6 (14.9) | 50.9 (15.5) | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | VAS, ODI, SFBI, SF-36 |

| Li C (27) | 2023 | 50 | 50 | 50.4 (6.9) | 50.2 (6.9) | Canggui Tanxue technique acupuncture | Huantiao point acupuncture | VAS, JOA, RDQ |

| Huang ZL (28) | 2019 | 23 | 23 | 63.0 (14.0) | 63.0 (11.0) | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | VAS, ODI |

| Gyeltshen D (29) | 2025 | 35 | 35 | 41.4 (12.8) | 41.1 (13.1) | Warm acupuncture | Gabapentin | VAS, RDQ |

| Pan HT (30) | 2022 | 38 | 38 | 57.0 (10.0) | 55.0 (10.0) | Fanzhen Jieci acupuncture | Conventional acupuncture | VAS, ODI |

| Zai FL (31) | 2018 | 30 | 30 | 55.1 (5.4) | 54.6 (5.4) | Warming needle moxibustion acupuncture | Conventional acupuncture | VAS, ODI |

| Liu CH (32) | 2019 | 15 | 15 | 63.2 (8.2) | 54.3 (14.9) | “High-dose” manual acupuncture | “Low-dose” manual acupuncture | VAS, RDQ |

Characteristics of the included studies.

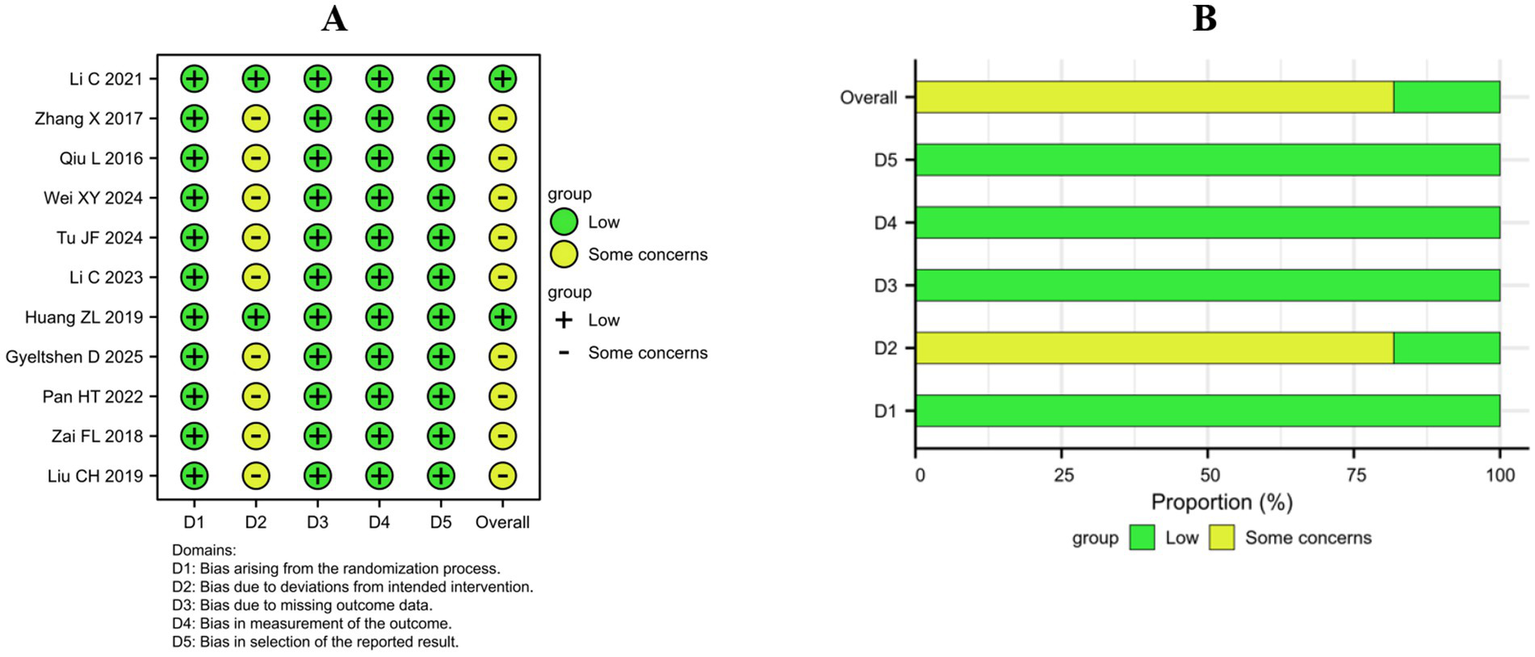

3.2 Risk of bias assessment

The assessment results of “risk of bias” in each domain for individual studies are shown in Figure 2A, while the percentage results of risk assessment for each domain are presented in Figure 2B. This study employed the Cochrane risk of bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool to evaluate the methodological quality of the 11 included studies. Overall, 2 studies (22, 28) had a low risk of bias, 9 studies (23–27, 29–32) had a potential risk of bias, and none had a high risk of bias.

Figure 2

Risk of bias within the included studies. (A) Risk of bias summary. (B) Risk of bias graph.

All 11 studies used a random allocation order, which is considered to have a low risk of bias. In terms of intervention measures, the main problem is the risk of bias caused by the nonblind method of carriers and people delivering the interventions, which is related to the characteristics of acupuncture. In the process of acupuncture treatment, it is difficult to implement blind acupuncture. However, 2 studies (22, 28) were judged to have a low risk of bias because they used adhesive pads to ensure blinding during sham acupuncture. Almost all 11 studies reported complete intervention outcomes for randomized participants, which were considered to have a low risk of bias. All 11 studies reported VAS scores as the primary outcome for assessing pain intensity, which is considered a low risk of bias. All 11 studies analyzed their data in accordance with a prespecified analysis plan that was finalized before unblinded outcome data were available for analysis, which was considered to have a low risk of bias.

3.3 Effect of interventions

3.3.1 VAS (visual analog scale) score for leg pain

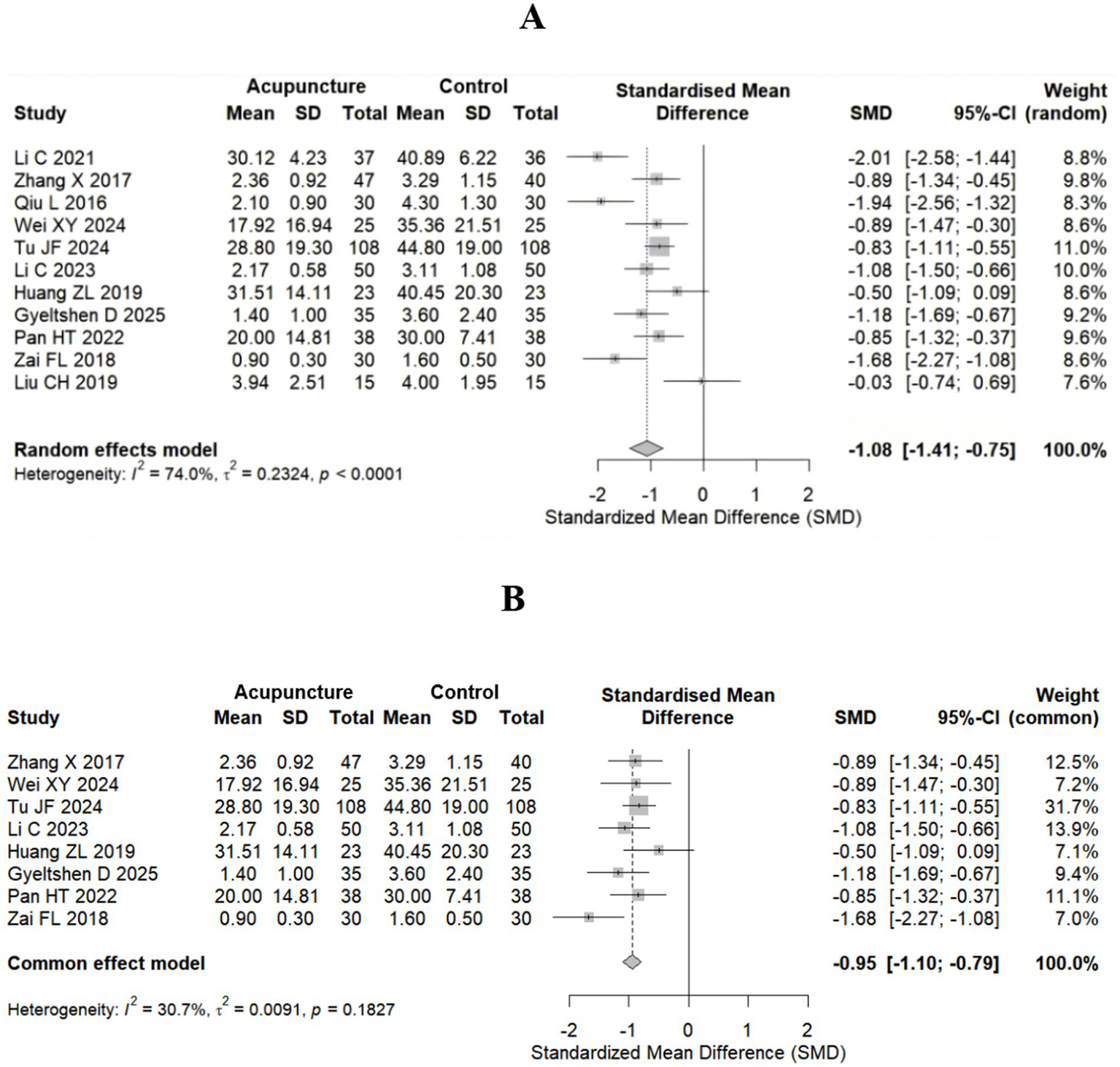

Previous studies (33, 34) have used the total effective rate as the primary outcome measure, but among the 11 studies included in this research, not all reported the number of effective cases treated with acupuncture. Therefore, we selected the VAS score (0–10 cm scale (22, 25, 26, 28, 30) and 0–100 cm scale (23, 24, 27, 29, 31, 32), with 0 cm representing no pain and 10 cm or 100 cm representing extreme pain) at 4 weeks postintervention as the primary outcome to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture for sciatica.

This study included 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with an overall sample size of 868 patients. A random-effects model was used to pool the standardized mean differences (SMDs), revealing that acupuncture treatment for sciatica demonstrated significant clinical efficacy (SMD = −1.08, 95% CI: −1.41–−0.75) (Figure 3A). This effect size exceeded Cohen’s d threshold for a large effect (d = 0.8) (34), indicating superior pain relief in the acupuncture group compared with the control group. Among the 11 studies, 9 studies (22–27, 29–31) reported statistically significant benefits (95% CI not 0), whereas Liu CH (32) reported no significant difference, potentially attributable to its smaller sample size (n = 15 in each group).

Figure 3

Forest plot for the VAS score. (A) All studies included (11 studies). (B) After highly heterogeneous studies (8 studies) were excluded.

There was high heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 74.0%). Therefore, after highly heterogeneous studies (22, 24, 32) were excluded, 8 studies (total sample size n = 718) were ultimately included, and a fixed-effect model combined with the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used. The results revealed that the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of sciatica was significantly better than that in the control group, with an SMD of −0.95 (95% CI: −1.10–−0.79) (Figure 3B). The effect size still exceeded Cohen’s d threshold for large effects (d = 0.8) (34). Heterogeneity was significantly reduced to an acceptable level (I2 = 30.7%, p = 0.1827), supporting the use of a fixed-effects model. The effectiveness of acupuncture on sciatica is more stable.

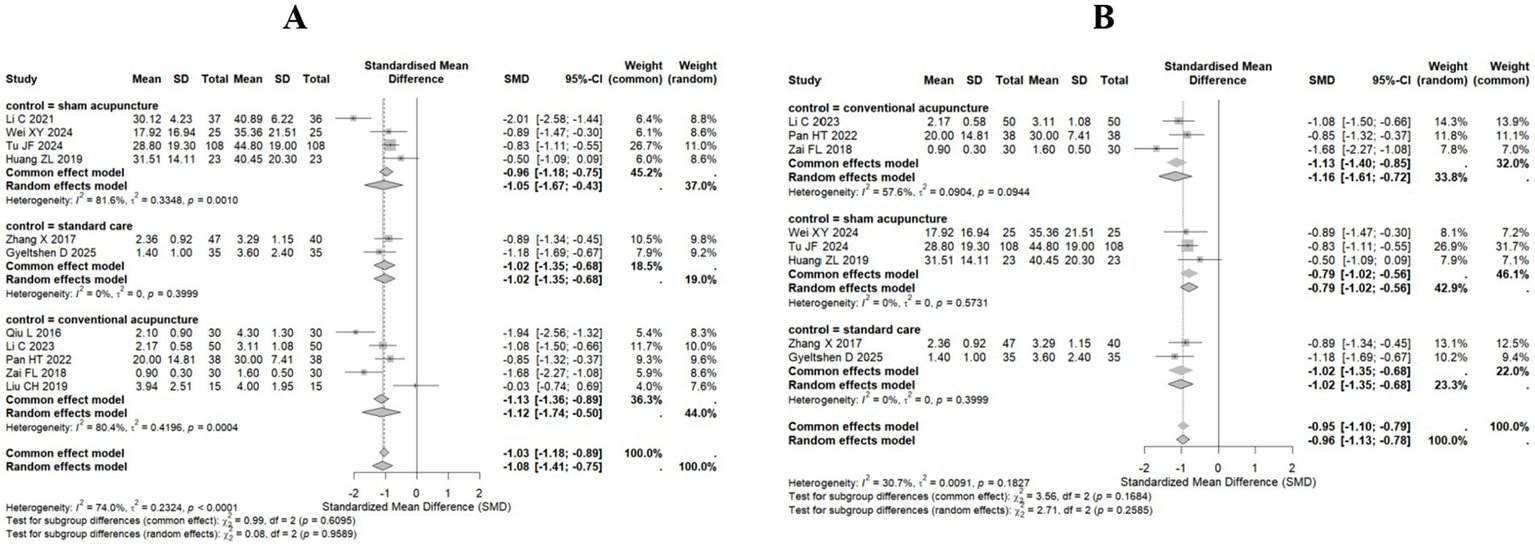

We also performed subgroup analysis on the basis of the types of control interventions. The subgroup analysis indicated that acupuncture treatment for sciatica demonstrated significant efficacy across different control types: the sham acupuncture control group (22, 25, 26, 28) presented a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD = −1.05 95% CI: −1.67 to −0.43); the standard care control group (23, 29) presented homogeneous significant efficacy (SMD = −1.02, 95% CI: −1.35 to −0.68; I2 = 0%, p = 0.3999); and the conventional acupuncture control group (24, 27, 30–32) presented a pooled effect size of SMD = −1.12 (95% CI: −1.74 to −0.50). All studies except Liu CH (32) (SMD = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.74 to 0.69) presented significant effectiveness. The test for subgroup differences revealed no statistically significant differences in either the fixed-effects model (p = 0.6095) or the random-effects model (p = 0.9589), indicating that acupuncture efficacy is not influenced by the control type. The overall pooled effect (11 studies) maintained a large effect size (SMD = −1.03, 95% CI: −1.18–−0.89) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of the VAS score. (A) All studies included (11 studies). (B) After highly heterogeneous studies (8 studies) were excluded.

Subgroup analyses also revealed substantial heterogeneity. Consequently, following the exclusion of highly heterogeneous studies (22, 24, 32), both fixed-effect and random-effects models were employed, utilizing the standardized mean difference (SMD) for pooled analysis. Results demonstrated consistent efficacy across all control groups (conventional acupuncture, sham acupuncture, and standard care). Under the random-effects model, the conventional acupuncture group exhibited an SMD of −1.16 (95% CI: −1.61 to −0.72), indicating moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57.6%). The sham acupuncture group yielded an SMD of −0.79 (95% CI: −1.02 to −0.56), with no observed heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The standard care group demonstrated an SMD of −1.02 (95% CI: −1.35 to −0.68), also without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The overall pooled SMD under the random-effects model was −0.96 (95% CI: −1.13 to −0.78), with total heterogeneity quantified at 30.7%. Subgroup differences were statistically non-significant (p = 0.2585), further indicating consistent treatment effects across control groups (Figure 4B).

The meta-regression analysis was performed using a mixed-effects model (Supplementary Figure 1). The results indicated the presence of residual heterogeneity (I2 = 9.43%), with the model explaining 31.28% of the heterogeneity. This suggests that the included moderating variable (type of control intervention) partially explains variation between studies, although the overall effect remained statistically non-significant. When sham acupuncture and standard care served as control groups, their influence on the intervention effect size exhibited no significant difference compared to the conventional acupuncture group (p > 0.05), indicating that the type of control intervention did not substantially modify the intervention’s efficacy. Across all study designs, the intervention’s effect size remained consistent irrespective of the control intervention type, demonstrating robust stability in the intervention’s effectiveness.

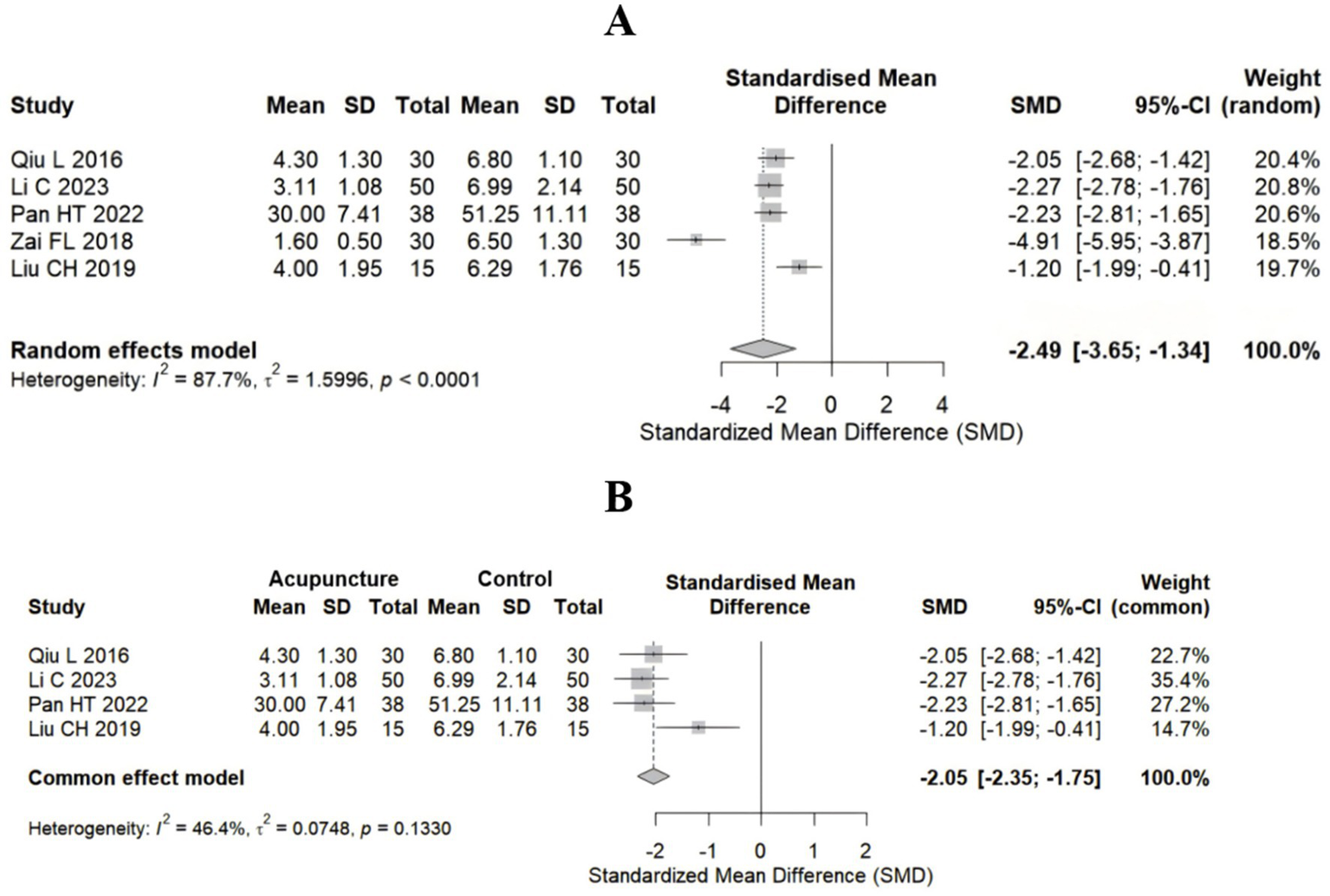

Among the 11 studies, 5 studies (24, 27, 30–32) used acupuncture as the control treatment. To demonstrate the efficacy of acupuncture for sciatica, we extracted the VAS score at 4 weeks postintervention and baseline from these 5 studies and pooled the effect sizes. The random-effects model results revealed that all studies confirmed significant clinical benefits of acupuncture treatment compared with baseline levels, with a pooled SMD of −2.49 (95% CI: −3.65–−1.34), far exceeding Cohen’s large effect threshold (SMD > 0.8) (Figure 5A). The extreme effect size observed in (31) may be the main reason for the high heterogeneity (I2 = 87.7%). After excluding study (31) that may have led to high heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was used to repool the effect sizes. The results similarly demonstrated the effectiveness of acupuncture for sciatica (Figure 5B).

Figure 5

Forest plot for the VAS score in the studies that used acupuncture as control group. (A) Control group vs. baseline group (5 studies); (B) after the exclusion of highly heterogeneous studies (4 studies).

3.3.2 ODI (Oswestry Disability Index)

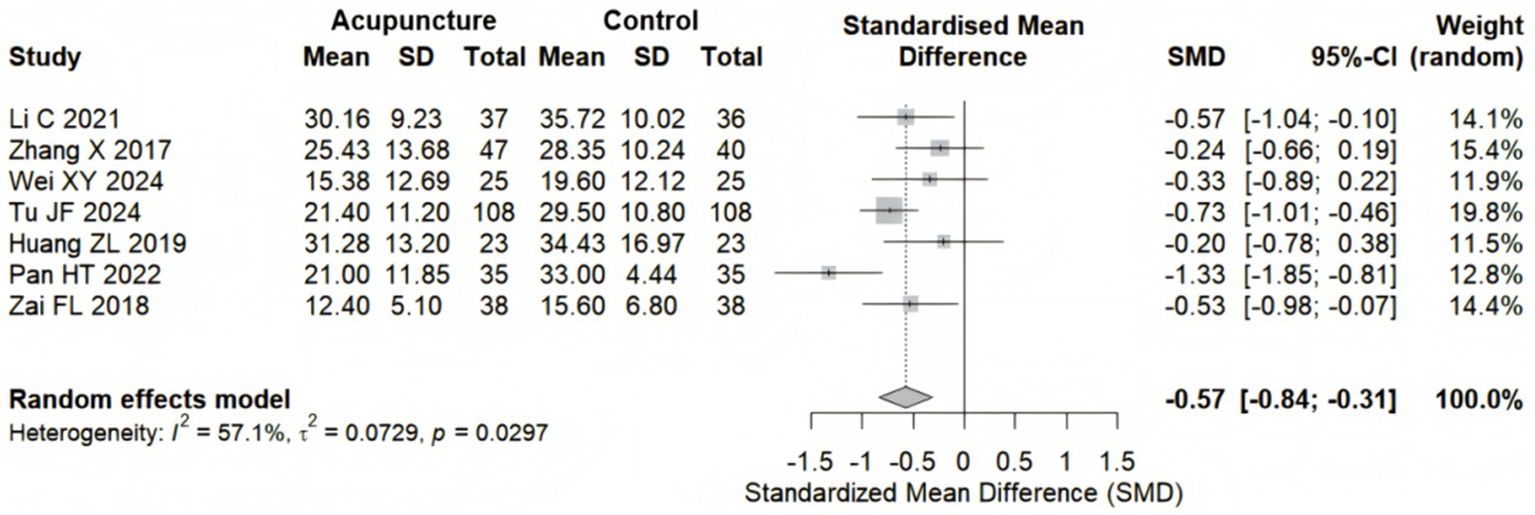

7 studies (22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31) with 621 participants examined the efficacy of acupuncture on the ODI. Pooled results demonstrated that acupuncture significantly outperformed the control group in improving the ODI for sciatica patients, with a random effects model yielding an SMD of −0.57 (95% CI: −0.84 to −0.31), reaching Cohen’s d threshold for a medium effect (d = 0.5) (34). Moderate heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 57.1%, p = 0.0297) (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot for the ODI.

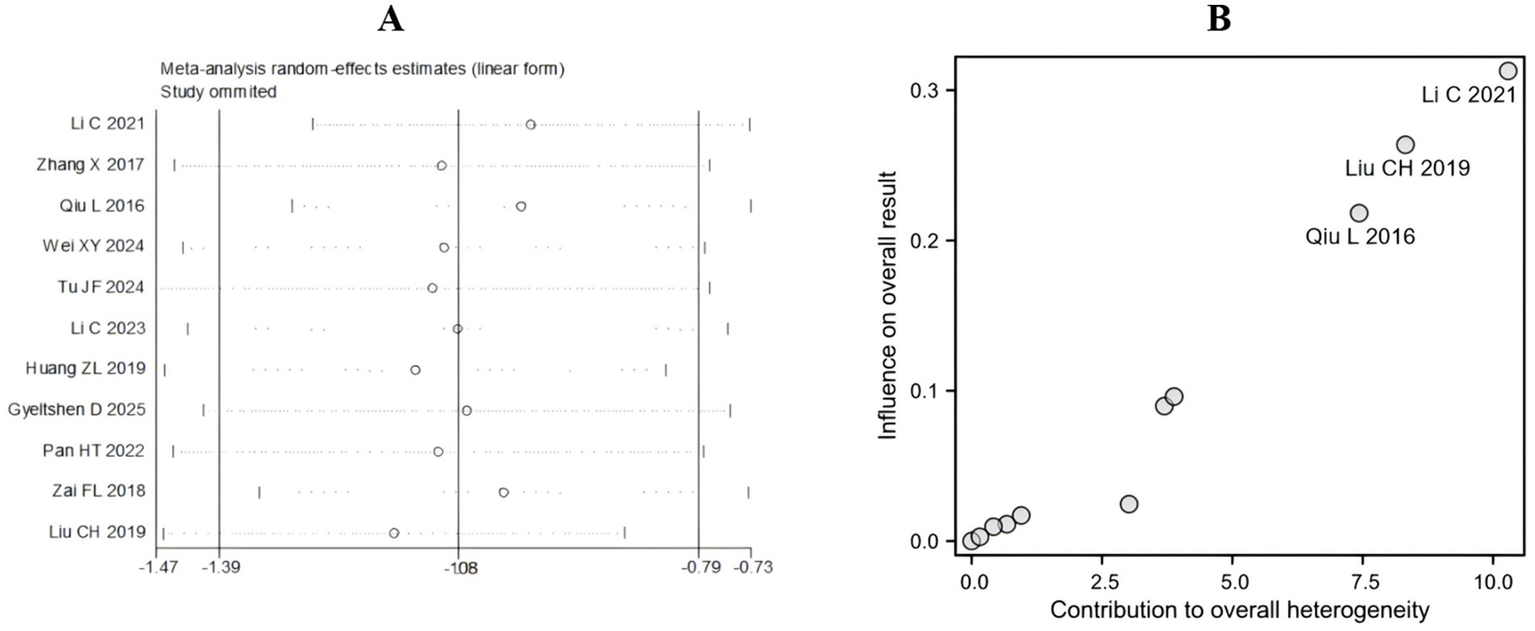

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

With respect to the high heterogeneity found in the effect of acupuncture on the VAS pain score (I2 = 74%), we performed a sensitivity analysis. This sensitivity analysis employed the leave-one-out method, confirming the robustness of the meta-analysis results for acupuncture treatment of sciatica (Figure 7A). When any one of the 11 included studies was sequentially removed, the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) under the random-effects model fluctuated between −1.47 and −0.73 (original pooled SMD = −1.08), with all adjusted effect sizes remaining statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, Baujat plot analysis identified three studies (22, 24, 32) exerting disproportionate influence on both heterogeneity and the pooled VAS score estimates (Figure 7B). These results demonstrated that the heterogeneity primarily originated from individual extreme studies, but the core conclusion (acupuncture significantly remits sciatica) was highly robust.

Figure 7

Sensitivity analysis. (A) Leave-one-out method for VAS. (B) Baujat plot for VAS.

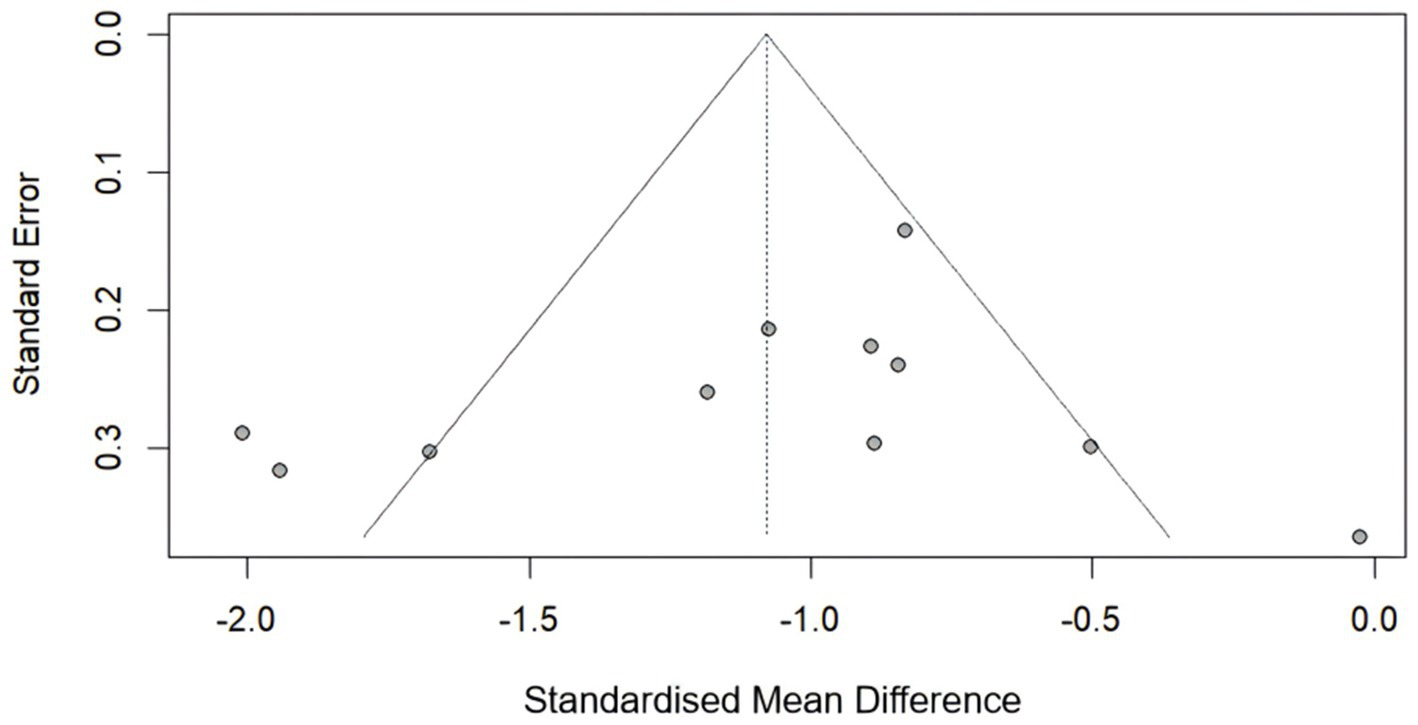

3.5 Publication bias

We generated a funnel plot (Figure 8) and used Eggee’s test and Begg’s test (Supplementary Table 3) to calculate the VAS scores. The symmetrical funnel distribution and the results of Egger’s test (p = 0.4755) and Begg’s test (p = 0.6971) support the absence of significant publication bias in this study.

Figure 8

Funnel plot for the VAS score.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture significantly reduced the VAS score and the ODI. Crucially, the subgroup analysis revealed no significant difference in efficacy between the types of control (sham acupuncture, standard care or traditional acupuncture), which strengthens the specific therapeutic effect of acupuncture beyond the placebo effect. Despite moderate to high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 57.1% for ODI outcomes; 74.0% for overall pain scores), the directional consistency of effects (SMD: −0.84 to −0.31 for ODI; −1.41 to −0.75 for VAS score) robustly supports the efficacy of acupuncture in alleviating sciatica. This heterogeneity likely stems from methodological diversity (e.g., variations in acupuncture protocols (e.g., electroacupuncture and manual acupuncture), outcome measurement tools (VAS and ODI), and control interventions (sham acupuncture and standard care)). Such clinical diversity is inherent in traditional medicine meta-analyses and does not invalidate efficacy conclusions when effects remain consistently favorable (35).

The symmetrical funnel distribution (Egger’s p = 0.475; Begg’s p = 0.69) indicates a low risk of publication bias, despite isolated outliers [e.g., (32)]. This suggests that small studies with null or negative findings were adequately captured, strengthening confidence in the pooled effect estimates.

The moderate improvement in the VAS score following acupuncture aligns with conventional therapies such as NSAIDs (36) but has superior safety. Future trials should standardize acupuncture protocols (e.g., using STRICTA guidelines) and prioritize patient-centered outcomes (e.g., duration of pain recovery and functional recovery) to bridge evidence-practice gaps.

Acupuncture, as a therapeutic approach for sciatica, has been extensively studied, particularly in the treatment of sciatica caused by herniated discs (37). Multiple studies have demonstrated that acupuncture can effectively alleviate sciatic pain and improve patients’ quality of life (38, 39). A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture is more effective than medication in treating sciatica and can enhance drug efficacy (14). Furthermore, the safety profile of acupuncture has been confirmed, with fewer adverse reactions, making it a viable alternative for patients who avoid or cannot tolerate medication (15).

5 Limitations

While the therapeutic efficacy of acupuncture has been preliminarily confirmed, existing research still faces several limitations. (1) Significant heterogeneity exists in acupuncture protocols across studies, including variations in acupoint selection, needling techniques, and treatment frequency, making it challenging to establish optimal treatment regimens. Future research should focus on developing standardized acupuncture protocols to better evaluate their effectiveness and facilitate broader application. (2) Current studies generally have small sample sizes and short follow-up periods, limiting long-term efficacy assessment. Therefore, future research requires larger-scale, well-designed randomized controlled trials to further validate the therapeutic outcomes and durability of acupuncture.

6 Conclusion

Acupuncture has statistically and clinically significant benefits for herniated disc-related sciatica. While methodological limitations in the extant literature necessitate cautious interpretation, these findings support the inclusion of acupuncture in multidisciplinary pain management. Future high-quality RCTs addressing current methodological shortcomings will strengthen evidence-based implementation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. J-yJ: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. HQ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Y-xD: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. L-hP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1689124/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Benzakour T Igoumenou V Mavrogenis AF Benzakour A . Current concepts for lumbar disc herniation. Int Orthop. (2019) 43:841–51. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4247-6,

2.

Hasvik E Haugen AJ Grøvle L . Symptom descriptors and patterns in lumbar radicular pain caused by disc herniation: a 1-year longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e065500. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065500,

3.

Munuera-Martínez PV Reina-Bueno M Vázquez-Bautista C Domínguez-Maldonado G Martínez-Navas Á García-Rodríguez MJ et al . Foot pressure in patients with chronic lumbar radicular pain (sciatica) caused by lumbar disc herniation: a case-control observational study. Eur Spine J. (2025) 34:2311–20. doi: 10.1007/s00586-025-08880-3,

4.

Zhang W Liu H Le X Song K Yang F Cui Z et al . Acupuncture for postoperative pain of lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e32016. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000032016,

5.

Karimi SA Zahra FT Martin LJ . IUPHAR review: navigating the role of preclinical models in pain research. Pharmacol Res. (2024) 200:107073. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107073,

6.

Sulaiman II Hamawandi SM Hammood EK Al-Tameemi AHM . Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica associated with lumbar disc herniation. Zanco J Med Sci. (2016) 20:1405_10. doi: 10.15218/zjms.2016.0038

7.

Tascioglu T Sahin O . The relationship between pain and herniation radiology in giant lumbar disc herniation causing severe sciatica: 15 cases. Br J Neurosurg. (2022) 36:483–6. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1866168,

8.

Yuan S Huang C Xu Y Chen D Chen L . Acupuncture for lumbar disc herniation: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e19117. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019117,

9.

DiZerega GS Traylor MM Alphonso LS Falcone SJ . Use of temporary implantable biomaterials to reduce leg pain and back pain in patients with sciatica and lumbar disc herniation. Materials. (2010) 3:3331–68. doi: 10.3390/ma3053331

10.

Gugliotta M da Costa BR Dabis E Theiler R Jüni P Reichenbach S et al . Surgical versus conservative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e012938. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012938,

11.

Han KH Cho KH Han C Cui S Lin L Baek HY et al . The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture treatment on sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. (2022) 71:102872. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102872

12.

Perreault T Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C Cummings M Gendron BC . Needling interventions for sciatica: choosing methods based on neuropathic pain mechanisms-a scoping review. J Clin Med. (2021) 10. doi: 10.3390/jcm10102189,

13.

Tanaka F Mazzardo G Salm DC de Oliveira BH Joaquim L Machado RS et al . Peripheral activation of formyl peptide receptor 2/ALX by electroacupuncture alleviates inflammatory pain by increasing interleukin-10 levels and catalase activity in mice. Neuroscience. (2023) 529:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.08.004,

14.

Qin Z Liu X Yao Q Zhai Y Liu Z . Acupuncture for treating sciatica: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e007498. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007498,

15.

Zhang Z Hu T Huang P Yang M Huang Z Xia Y et al . The efficacy and safety of acupuncture therapy for sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. Front Neurosci. (2023) 17:1097830. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1097830,

16.

Zhang J Xie Y Li J Yuan M Yu Z Su Y et al . Effectiveness and safety of warm needle acupuncture for sciatica: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e24126. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024126,

17.

Zhong X Liu J Liu H Zhang H . Time points of outcome are often neglected in acupuncture meta-analyses: a methodological survey. J Clin Epidemiol. (2024) 169:111273. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2024.111273,

18.

Haddaway NR Page MJ Pritchard CC McGuinness LA . PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. (2022) 18:e1230. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1230,

19.

Moher D Hopewell S Schulz KF Montori V Gøtzsche PC Devereaux PJ et al . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. (2010) 63:e1–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004,

20.

Held L Hofmann F Pawel S . A comparison of combined p-value functions for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. (2025) 16:758–85. doi: 10.1017/rsm.2025.26

21.

Wilnes B Castello-Branco B Martins Pereira EM Lopes LM Santos VB Bicalho AC et al . Extrastimuli-assisted functional mapping improves ventricular tachycardia ablation outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Heart Rhythm. (2025) S1547-5271(25)02304-5. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.03.2000

22.

Li C Li T Ma X Ni C Wei X Zhang S . A randomized clinical study on acupuncture therapy for relieving sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation. Indian J Pharm Sci. (2021) 83:5–9. doi: 10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.spl.284

23.

Zhang X Wang Y Wang Z Wang C Ding W Liu Z . A randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of electroacupuncture versus medium-frequency electrotherapy for discogenic sciatica. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2017) 2017:9502718. doi: 10.1155/2017/9502718

24.

Qiu L Hu XL Zhao XY Zheng X Zhang J Zhang M et al . A randomized controlled clinical trial of treatment of lumbar disc herniation-induced sciatica by acupuncture stimulation of sciatic nerve trunk. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. (2016) 41:447–50. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.2016.05.015

25.

Wei X-Y Wang X Shi G-X Tu J-F Yang J-W Ren M-M et al . Acupuncture modulation of chronic neuropathic pain and its association with brain functional properties. J Pain. (2024) 25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2024.104645,

26.

Tu J-F Shi G-X Yan S-Y Ni G-X Yu F-T Cai G-W et al . Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture for chronic sciatica from herniated disk. JAMA Intern Med. (2024) 184. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.5463,

27.

Li C Qi X Wang F Wang J . Clinical efficacy of acupuncture with Canggui Tanxue technique on Huantiao point for treating sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation. Altern Ther Health Med. (2023) 29:376–81.

28.

Huang Z Liu S Zhou J Yao Q Liu Z . Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic discogenic sciatica, a randomized controlled sham acupuncture trial. Pain Med. (2019) 20:2303–10. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz167,

29.

Gyeltshen D Dorji T Tenzin K Choeda T Gurung MS Pongpirul K et al . Efficacy and safety of warm acupuncture compared to gabapentin for pain management in patients with sciatica in Bhutan: a randomized controlled (ACUWARM) trial. J Evid Based Integr Med. (2025) 30:2515690x251355513. doi: 10.1177/2515690X251355513,

30.

Pan HT Li J Feng CC Pei LJ Xi ZQ Hou WG et al . Therapeutic effect of Fanzhen Jieci needling on discogenic sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. (2022) 42:261–6. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20210405-k0004

31.

Zai FL Wu RL Zheng MF Guo LY . Warming needle Moxibustion relieves symptoms of lumbar disc herniation patients and upregulates plasma β-endorphin. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. (2018) 43:512–5. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.170736,

32.

Liu CH Kung YY Lin CL Yang JL Wu TP Lin HC et al . Therapeutic efficacy and the impact of the "dose" effect of acupuncture to treat sciatica: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Pain Res. (2019) 12:3511–20. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S210672

33.

Wang J Liang C Zeng F Fan L Zhuang J . Comparison of needle-warming moxibustion and other physical therapies for lumbar disc herniation: a meta-analysis. Comput Math Methods Med. (2022) 2022:2986223. doi: 10.1155/2022/2986223,

34.

Lakens D . Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. (2013) 4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863,

35.

Thompson SG . Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. BMJ. (1994) 309:1351–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6965.1351,

36.

Machado GC Maher CG Ferreira PH Day RO Pinheiro MB Ferreira ML . Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:1269–78. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210597

37.

Xiang A Xu M Liang Y Wei J Liu S . Immediate relief of herniated lumbar disc-related sciatica by ankle acupuncture: a study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Medicine. (2017) 96:e9191. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009191,

38.

Tang S Mo Z Zhang R . Acupuncture for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. (2018) 36:62–70. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2016-011332,

39.

Yan L Zhang J Wang X Zhou Q Wen J Zhao H et al . Efficacy of acupuncture for lumbar disc herniation: changes in paravertebral muscle and fat infiltration - a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2024) 15:1467769. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1467769,

Summary

Keywords

acupuncture therapy, chronic sciatica, disc herniation, meta-analysis, ODI (Oswestry Disability Index), VAS (visual analog scale) score

Citation

Qu Z, Ju J-y, Qin H, Ding Y-x and Peng L-h (2026) Effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic sciatica from herniated disks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 13:1689124. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1689124

Received

20 August 2025

Revised

05 December 2025

Accepted

08 January 2026

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Maria Chiara Maccarone, University of Padua, Italy

Reviewed by

Lili Zhu, Shuguang Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Lengge Si, Inner Mongolia Medical College, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Qu, Ju, Qin, Ding and Peng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li-hua Peng, 140733@hospital.cqmu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.