Abstract

Introduction:

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a prevalent degenerative spinal condition in older adults, often necessitating surgical intervention and long-term pharmacological treatment. Korean medicine (KM) has emerged as a relatively safe alternative; however, its impact on surgical rates and opioid use in patients with LSS has not been thoroughly investigated. This nationwide retrospective cohort study aimed to assess the effects of KM treatment on these outcomes.

Methods:

We analyzed claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) for patients newly diagnosed with LSS in 2015. The KM group included patients who had ≥ 3 outpatient KM visits within 1 year of diagnosis and received KM care more frequently than Western medicine (WM). The control group comprised patients with ≥ 3 outpatient WM visits and no KM use during the same period. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed, and outcomes were compared using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results:

After PSM, 70,897 matched pairs were included in the surgery dataset, and 17,217 patients per group in the opioid dataset. KM treatment was associated with significantly lower risks of lumbar surgery (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.821; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.782–0.862), opioid use (HR: 0.810; 95% CI: 0.752–0.872), and opioid use excluding tramadol (HR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.630–0.919).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that KM treatment is associated with a reduced long-term risk of lumbar surgery and opioid use in patients with LSS. KM may represent a potentially effective conservative treatment option. Further randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate these findings.

1 Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a condition characterized by the progressive compression of neural and vascular structures within the spinal canal, resulting from degenerative hypertrophy of bones, ligaments, and synovial tissues in the lower axial spine. This narrowing can lead to a range of symptoms, including lower back pain, radiating leg pain, and neurogenic claudication, either individually or in combination (1).

LSS affects approximately 103 million individuals worldwide each year (2). It is one of the most common degenerative spinal disorders and is strongly associated with aging. Notably, 47% of individuals aged 60 to 69 have been reported to have mild to moderate stenosis (3), and LSS is the leading indication for spinal surgery among adults aged 65 years and older (4).

With the ongoing global increase in the elderly population, both the prevalence of LSS and its associated healthcare and societal burdens are expected to rise. Moreover, LSS has been shown to have a more profound negative impact on quality of life (QoL) than other comorbid conditions, such as hip or knee osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease (5), highlighting the urgent need for more effective treatment strategies.

The treatment of LSS typically follows a stepwise approach. Conservative management, including physical therapy and pharmacological interventions, is usually initiated first. However, the long-term effectiveness of these conservative strategies remains uncertain. Physical therapy often provides only temporary symptom relief (6), and epidural steroid injections (ESIs) provide short-term symptom relief but show limited long-term effectiveness, as a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported only a modest, non-significant short-term trend toward reduced surgery rates and no sustained benefit over longer follow-up (7). When symptoms persist or worsen despite conservative measures, surgical decompression becomes an option.

However, surgery carries considerable risk and limited long-term success, particularly among older adults. A prospective study reported that 33% of patients who underwent surgery experienced treatment failure (8), and a retrospective cohort study using data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service showed that the reoperation rate after surgery for LSS reached 14.2% within 5 years and was projected to increase to 22.9% by year 10 (9). Furthermore, among older adults with musculoskeletal pain, the use of opioid analgesics has been linked to a threefold higher risk of adverse events compared with placebo, and the likelihood of treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects is four times higher (10). These limitations highlight the need for safe and sustainable treatment alternatives.

Korean medicine (KM) has gained attention as a safe alternative. In clinical practice in Korea, various KM modalities – including acupuncture, herbal medicine, pharmacopuncture, and Chuna manual therapy – are frequently used to manage LSS. Several studies have demonstrated that these KM interventions can improve pain, physical function, and QoL (11–15). Acupuncture and pharmacopuncture are known to modulate inflammatory pathways, enhance microcirculation, and regulate central pain signaling through both peripheral and central mechanisms (16). Chuna therapy may relieve mechanical compression and improve spinal alignment (17). These multimodal mechanisms may collectively alleviate pain, improve function, and potentially reduce the need for invasive surgery or long-term opioid use.

However, to date, no study has evaluated the effectiveness of KM using large-scale, population-based data from real-world clinical settings in Korea. Previous studies were generally limited in scope and duration, making it difficult to clarify the long-term, population-level impact of KM on major clinical outcomes. In particular, the effect of KM treatment on surgical rates and opioid use among patients with LSS has not been examined using representative national data. Addressing these evidence gaps, the present study aimed to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of integrative KM treatment for LSS, focusing specifically on its association with lumbar surgery and opioid use.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data source

This study utilized a nationwide claims database provided by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) of Korea (18), comprising healthcare claims for services reimbursed between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2020.

The study received ethical exemption approval from the Institutional Review Board of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine (JASENG IRB 2021-07-002; approved on July 9, 2021). As the research involved secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data, the requirement for informed consent was waived. All analyses were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by HIRA for the use of public data, and all procedures adhered to relevant ethical and regulatory guidelines.

2.2 Study population

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they received healthcare services with LSS (ICD-10 code M48.0) listed as the primary diagnosis between January 1 and December 31, 2015. Medical service utilization was defined as any claim submitted under the National Health Insurance (NHI) system for LSS-related treatment, including KM interventions such as acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and cupping.

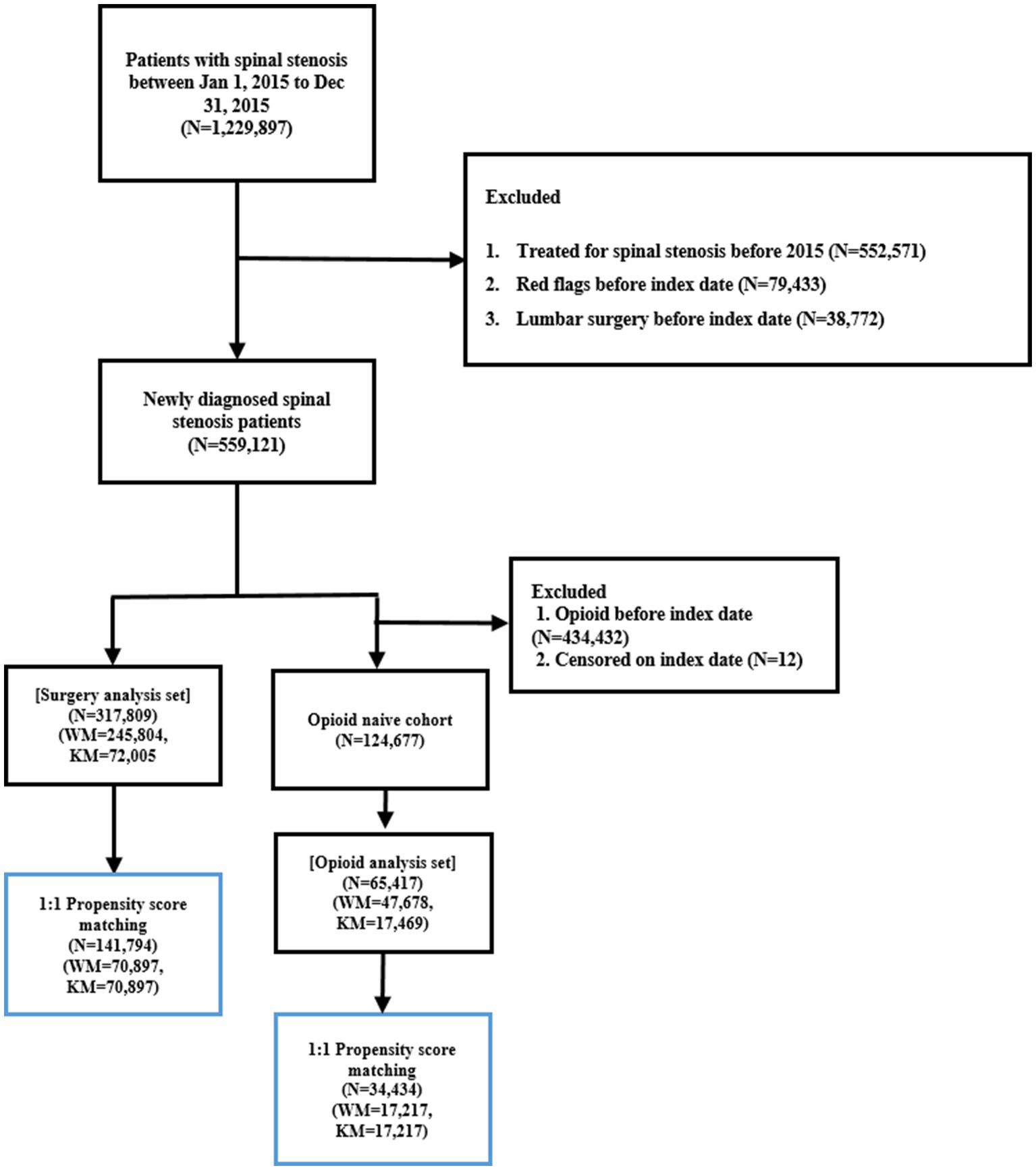

The entry date was defined as the first diagnosis of LSS (M48.0) in 2015, while the index date was 1 year after the entry date. A one-year washout period prior to the entry date was applied to exclude patients with a prior diagnosis of LSS. Patients with red flag conditions (e.g., malignancy, infection, or major trauma) diagnosed within 1 year before the index date were excluded (19) (see Supplementary Table 1). Patients with a history of spinal surgery, other than surgeries related to study outcomes, were also excluded. For the opioid analysis, individuals who had been prescribed opioid analgesics within 1 year before the entry date were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Overview of the study design. (A) Surgery set; (B) Opioid set.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated based on ICD-10 codes using the method proposed by Quan et al. (20). Medical service utilization was quantified by counting LSS-related visits (to either KM or Western medicine [WM] providers) between the entry and index dates, categorized into quartiles, and used as a proxy variable for disease severity.

2.3 Definition of KM and non-KM groups

Customized claims data extracted from HIRA based on variables requested by the researchers were utilized. Patients diagnosed with LSS (M48.0) were categorized into two groups based on their healthcare utilization patterns within the first year after diagnosis:

(a) The KM group included patients who had ≥3 outpatient visits to KM providers and had more KM visits than WM visits during the same period. (b) The non-KM group comprised patients who had ≥3 outpatient WM visits and no KM visits during the one-year period following the entry date. To evaluate the robustness of the operational definition of KM utilization, we additionally conducted sensitivity analyses applying higher visit thresholds (≥6 and ≥8 KM visits within the first year).

2.3.1 Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were: (a) lumbar spine surgery, defined as any of the following procedures: discectomy, laminectomy, or spinal fusion. Relevant procedure codes from the NHI claims database are listed in Supplementary Table 2 (21). (b) Opioid prescription, defined as either ≥14 days of tramadol-based analgesics or ≥7 days of opioid-class analgesics (22). Analyses were conducted for (a) any qualifying opioid use (including tramadol), and (b) opioid-only use (excluding tramadol). Medications were categorized using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes (see Supplementary Table 3). The 7-day threshold for opioid-class analgesics was based on clinical guidelines indicating that prolonged opioid use beyond 3–7 days in acute pain offers no additional benefit and may be associated with poorer functional outcomes (23). The 14-day threshold for tramadol was determined according to opioid prescribing guidelines (24) and previous observational research that defined exposure windows using clinically interpretable and empirically derived criteria (25).

The follow-up period began 1 year after the entry date and extended up to 4 years post-entry. Patients were censored from the analysis if they, prior to the outcome event, (1) were prescribed opioids for unrelated conditions, (2) were diagnosed with red flag conditions, or (3) underwent lumbar surgery not meeting the outcome criteria.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, LSS-related healthcare utilization, comorbidities, and CCI scores. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (n) and percentages (%), while continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD). Baseline differences between KM and non-KM groups were assessed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the independent t-test for continuous variables.

To minimize selection bias and control for confounding factors affecting surgery or opioid outcomes, propensity score matching (PSM) was applied. Propensity scores were calculated using logistic regression, and 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching was performed with a caliper width of 0.1. Matching variables included: sex, age, CCI, presence of spondylolisthesis, and hospitalization status and insurance type, which also served as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used to assess covariate balance post-matching, with an SMD > 0.1 indicating imbalance.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to compare time-to-event outcomes between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to evaluate model fit across different stages of adjustment and PSM.

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics and propensity score matching

A total of 1,229,897 patients diagnosed with LSS (ICD-10 code M48.0) between January 1 and December 31, 2015, were initially identified. Patients were excluded if they (1) had a diagnosis of LSS within 1 year prior to the entry date, (2) were diagnosed with red flag conditions within 1 year before the index date, or (3) underwent lumbar surgery before the index date. After applying these criteria, 559,121 patients were included in the final study cohort.

Patients were classified into two groups based on healthcare utilization patterns during the one-year period following diagnosis. The KM group included those who had ≥ 3 outpatient visits to KM institutions and had more KM visits than WM visits during that year. The control group comprised patients who had ≥ 3 outpatient WM visits and no KM visits in the same period. Based on these criteria, the surgery dataset included 317,809 patients, with 72,005 in the KM group and 245,804 in the control group, while the opioid dataset comprised 65,417 patients, including 47,678 in the KM group and 17,469 in the control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Flowchart illustrating the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to identify the final study cohorts for the surgery and opioid analyses.

Prior to PSM, significant baseline differences were observed between the KM and control groups in both datasets. These differences included sex, age, type of insurance coverage, CCI, hospitalization status, and the presence of spondylolisthesis. The KM group had a higher proportion of females and older patients, as well as a greater number of patients covered by the NHI. Additionally, the KM group tended to have higher CCI scores and a higher prevalence of spondylolisthesis. Similar patterns were observed in the opioid dataset.

To address these differences, PSM was applied. After matching, the surgery dataset included 70,897 matched patients in each group, while the opioid dataset included 17,217 matched patients in each group. Following PSM, no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the KM and control groups. All SMDs were 0.00, indicating excellent covariate balance (Table 1). Additional comparisons of comorbidities and healthcare utilization not included in the PSM model are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 1

| Variables | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WM | KM | p-value | SMD | WM | KM | p-value | SMD | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||

| Surgery dataset | 245,804 | 72,005 | 70,897 | 70,897 | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 93,496 | 38.0 | 22,042 | 30.6 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 21,713 | 30.6 | 21,712 | 30.6 | 0.317 | 0.00 |

| Female | 152,308 | 62.0 | 49,963 | 69.4 | −0.16 | 49,184 | 69.4 | 49,185 | 69.4 | 0.00 | ||

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| <50 | 24,017 | 9.8 | 6,273 | 8.7 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 6,037 | 8.5 | 6,038 | 8.5 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| 50–59 | 55,162 | 22.4 | 14,029 | 19.5 | 0.07 | 13,644 | 19.2 | 13,644 | 19.2 | 0.00 | ||

| 60–69 | 74,380 | 30.3 | 22,284 | 31.0 | −0.01 | 22,009 | 31.0 | 22,009 | 31.0 | 0.00 | ||

| 70–79 | 69,299 | 28.2 | 23,609 | 32.8 | −0.10 | 23,445 | 33.1 | 23,444 | 33.1 | 0.00 | ||

| ≥80 | 22,946 | 9.8 | 5,810 | 8.1 | 0.05 | 5,762 | 8.1 | 5,762 | 8.1 | 0.00 | ||

| Insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 226,806 | 92.3 | 68,400 | 95.0 | <0.001 | −0.11 | 67,348 | 95.0 | 67,348 | 95.0 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| Medical aid | 18,998 | 7.7 | 3,605 | 5.0 | 0.11 | 3,549 | 5.0 | 3,549 | 5.0 | 0.00 | ||

| CCI | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 132,580 | 53.9 | 38,105 | 52.9 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 37,417 | 52.8 | 37,417 | 52.8 | 0.920 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 72,167 | 29.4 | 21,511 | 29.9 | −0.01 | 21,223 | 29.9 | 21,222 | 29.9 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 26,061 | 10.6 | 7,929 | 11.0 | −0.01 | 7,850 | 11.1 | 7,849 | 11.1 | 0.00 | ||

| ≥3 | 14,996 | 6.1 | 4,460 | 6.2 | 0.00 | 4,407 | 6.2 | 4,409 | 6.2 | 0.00 | ||

| WM hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| No | 222,884 | 90.7 | 65,578 | 91.1 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 65,359 | 92.2 | 65,358 | 92.2 | 0.317 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 22,920 | 9.3 | 6,427 | 8.9 | 0.01 | 5,538 | 7.8 | 5,539 | 7.8 | 0.00 | ||

| KM hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| No | 245,804 | 100 | 70,897 | 98.5 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 70,897 | 100 | 70,897 | 100 | – | – |

| Yes | 1,108 | 1.5 | −0.18 | |||||||||

| Spondylolisthesis | ||||||||||||

| No | 237,491 | 96.6 | 69,374 | 96.4 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 38,352 | 96.4 | 68,351 | 96.4 | 0.317 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 8,313 | 3.4 | 2,631 | 3.6 | −0.01 | 2,545 | 3.6 | 2,545 | 3.6 | 0.00 | ||

| Opioid dataset | 47,678 | 17,469 | 17,217 | 17,217 | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 19,628 | 41.2 | 5,851 | 33.5 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 5,762 | 33.5 | 5,764 | 33.5 | 0.157 | 0.00 |

| Female | 28,050 | 58.8 | 11,618 | 66.5 | −0.16 | 11,455 | 66.5 | 11,453 | 66.5 | 0.00 | ||

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| <50 | 6,333 | 13.3 | 2,028 | 11.6 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 1,964 | 11.4 | 1,964 | 11.4 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| 50–59 | 11,252 | 23.6 | 3,662 | 21.0 | 0.06 | 3,571 | 20.7 | 3,571 | 20.7 | 0.00 | ||

| 60–69 | 14,135 | 29.7 | 5,389 | 30.9 | −0.03 | 5,332 | 31.0 | 5,332 | 31.0 | 0.00 | ||

| 70–79 | 11,965 | 25.1 | 5,066 | 29.0 | −0.09 | 5,035 | 29.2 | 5,035 | 29.2 | 0.00 | ||

| ≥80 | 3,993 | 8.4 | 1,324 | 7.6 | 0.03 | 1,315 | 7.6 | 1,315 | 7.6 | 0.00 | ||

| Insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 45,071 | 94.5 | 16,905 | 96.8 | <0.001 | −0.11 | 16,662 | 96.8 | 16,662 | 96.8 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| Medical aid | 2,607 | 5.5 | 564 | 3.2 | 0.11 | 555 | 3.2 | 555 | 3.2 | 0.00 | ||

| CCI | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 29,187 | 61.2 | 10,422 | 59.7 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 10,250 | 59.5 | 10,250 | 59.5 | 0.766 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 12,690 | 26.6 | 4,803 | 27.5 | −0.02 | 4,749 | 27.6 | 4,748 | 27.6 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 3,869 | 8.1 | 1,504 | 8.6 | −0.02 | 1,492 | 8.7 | 1,489 | 8.7 | 0.00 | ||

| ≥3 | 1,932 | 4.1 | 740 | 4.2 | −0.01 | 726 | 4.2 | 730 | 4.2 | 0.00 | ||

| WM hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| No | 17,038 | 35.7 | 1,161 | 6.7 | 0.151 | 0.01 | 6,177 | 35.9 | 1,149 | 6.7 | 0.157 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 12,468 | 26.2 | 3,166 | 18.1 | 0.01 | 4,444 | 25.8 | 3,133 | 18.2 | 0.00 | ||

| KM hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| No | 47,678 | 100 | 17,217 | 98.6 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 17,217 | 100 | 17,217 | 100 | – | – |

| Yes | 252 | 1.4 | −0.17 | |||||||||

| Spondylolisthesis | ||||||||||||

| No | 46,216 | 96.9 | 16,886 | 96.7 | 0.079 | 0.02 | 16,661 | 96.8 | 16,658 | 96.8 | 0.083 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 1,462 | 3.1 | 583 | 3.3 | −0.02 | 556 | 3.2 | 559 | 3.3 | 0.00 | ||

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

3.2 Surgical and opioid prescription outcomes in matched cohorts

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the incidence of lumbar spine surgery and opioid prescriptions in the matched KM and control groups are shown in Supplementary Figures 1–3. Although the KM group exhibited a trend toward lower opioid prescription rates, the difference was not statistically significant based on the log-rank test. Detailed comparisons of opioid prescription rates between the groups are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were conducted with sequential adjustments, including demographic variables (age, sex, insurance type), CCI, and comorbidities.

3.2.1 Surgery

Patients in the KM group had a significantly lower risk of undergoing lumbar spine surgery compared to the control group. In the model adjusted for healthcare utilization, HR was 0.806 (95% CI: 0.768–0.846). In the final model (Model 4), which additionally adjusted for demographic variables, CCI, and comorbidities, the HR was 0.821 (95% CI: 0.782–0.862), indicating that KM utilization within 1 year of diagnosis was significantly associated with a reduced long-term risk of surgery. Sensitivity analyses using higher KM utilization thresholds (≥6 and ≥8 visits during the first year) showed slightly higher hazard ratio estimates than the primary analysis, but the overall direction and interpretation of the association remained unchanged (Supplementary Table 6).

3.2.2 Opioid prescription

For the combined outcome of ≥ 7 days of opioid-class analgesics or ≥ 14 days of tramadol, the KM group showed a significantly lower prescription rate after adjustment for healthcare utilization (HR: 0.794, 95% CI: 0.739–0.854). This association remained significant in the fully adjusted model (HR: 0.810; 95% CI: 0.752–0.872).

For the outcome limited to opioid-class analgesics (excluding tramadol), the KM group again demonstrated a significantly lower prescription rate in the healthcare utilization-adjusted model (HR: 0.729; 95% CI: 0.605–0.877). This association persisted in the final model (HR: 0.761; 95% CI: 0.630–0.919) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Outcomes | After propensity score matching | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Surgery (ref. WM) | 0.806 (0.768–0.846)*** | 0.805 (0.767–0.845)*** | 0.808 (0.770–0.847)*** | 0.821 (0.782–0.862)*** |

| Opioid (ref. WM) | 0.794 (0.739–0.854)*** | 0.810 (0.754–0.872)*** | 0.811 (0.754–0.872)*** | 0.810 (0.752–0.872)*** |

| Opioids excluding tramadol (ref. WM) | 0.729 (0.605–0.877)*** | 0.750 (0.622–0.903)** | 0.751 (0.623–0.905)** | 0.761 (0.630–0.919)** |

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of surgery and opioid outcomes comparing Korean medicine and Western medicine user groups.

Model 1: Adjusted for healthcare utilization (categorized into quartiles).

Model 2: Adjusted for healthcare utilization (quartiles) and demographic variables (age, sex, and health insurance type).

Model 3: Adjusted for healthcare utilization, demographic variables, and CCI.

Model 4: Adjusted for healthcare utilization, demographic variables, CCI, and comorbidities.

NHI, National Health Insurance; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. * p-value <0.05, ** p-value <0.01, *** p-value <0.001.

Finally, model fit was evaluated across the various stages of adjustment and matching using the AIC. Results are presented in Supplementary Table 7.

4 Discussion

This study is the first to utilize nationwide claims data from HIRA to evaluate the impact of KM on surgery and opioid use among patients with LSS in real-world clinical settings.

Although the log-rank test did not show statistically significant differences between groups, the Kaplan–Meier curves indicated a small but persistent separation over time. When adjusted for demographic and clinical factors in the Cox models, these modest differences translated into statistically significant hazard reductions. This pattern suggests that while the absolute differences were not large enough to reach significance in an unadjusted survival comparison, the adjusted analyses captured clinically meaningful and directionally consistent benefits associated with KM utilization. Given the limitations of claims data in capturing clinical severity, healthcare utilization was used as a proxy for disease severity in our models, and model fit metrics such as the AIC supported the validity of this analytical approach.

The proportion of medical aid beneficiaries in the matched dataset was approximately 5%, slightly higher than the national average of 2.8–2.9%. Although this pattern was observed in both KM and control groups, it may reflect differences in healthcare utilization behaviors compared to the broader LSS population. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Our findings differ slightly from those of previous studies. For example, a nationwide retrospective cohort study by Koh et al. (26), which investigated the impact of acupuncture on surgery rates among patients with low back pain, reported a lower HR of 0.633 (95% CI: 0.576–0.696), compared to the HR of approximately 0.8 observed in our study. This discrepancy may be partly attributable to key methodological and clinical differences between the two studies. Koh et al. examined nonspecific low back pain, a condition with greater heterogeneity and generally less structural degeneration than LSS, and defined acupuncture exposure as only two treatment sessions over 6 weeks, with a two-year follow-up duration. In contrast, our study focused on patients with radiologically inferred degenerative spinal stenosis, applied a more stringent KM exposure definition (≥3 visits over the first year and greater KM than WM utilization), and evaluated long-term outcomes over up to 4 years. These differences in disease severity, exposure intensity, and follow-up duration likely contribute to the more modest effect sizes observed in our LSS cohort.

In Korea, integrative KM is widely used as a conservative and noninvasive treatment for LSS. Clinical practice generally involves a combination of modalities such as acupuncture, herbal medicine, Chuna manual therapy, and pharmacopuncture (13). An analysis of Korean national health insurance data from 2010 to 2019 indicated that the most frequently claimed KM treatments for LSS included acupuncture (50.6%), cupping (12.2%), electroacupuncture (8.7%), and moxibustion (5.7%). Herbal decoctions, pharmacopuncture, and Chuna therapy – although not reimbursed at the time – were also commonly used (27). Notably, Chuna therapy has been reimbursed under insurance since 2019 (27).

The potential for KM to reduce the need for surgery and opioid use is supported by a growing body of clinical and mechanistic evidence. A longitudinal follow-up study by Kim et al. (11) demonstrated that KM treatment, including acupuncture, resulted in sustained improvements in pain and functional disability among patients with LSS. In addition, a retrospective observational study reported that integrative KM treatment was associated with meaningful improvements in gait function and pain over a one-year period, supporting its potential long-term benefits in routine practice (12).

Mechanistically, acupuncture has been shown to stimulate the posterior rami of the spinal nerves, enhance blood flow to the sciatic and cauda equina nerves, and modulate inflammatory pathways by inhibiting HMGB1/RAGE and TLR4/NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2 (28, 29). Herbal medicines commonly used in KM practice for LSS, such as Harpagophytum procumbens, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects through NRF2 activation, while human placental extract pharmacopuncture has been shown to downregulate pain-related gene expression and promote neuroregeneration (30, 31).

Building on these mechanisms, recent randomized evidence further supports the clinical relevance of KM interventions. A pragmatic randomized pilot trial of acupotomy showed improvements in pain, walking capacity, and disability over 12 weeks with no major safety concerns (14). Moreover, a multicenter pragmatic randomized controlled trial investigating pharmacopuncture for LSS is currently underway (32), and its findings are expected to provide additional high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of KM modalities in managing degenerative lumbar conditions.

Despite the strengths of this large, population-based study, several limitations should be noted. First, the reliance on administrative claims data precludes access to key clinical variables such as anatomical stenosis severity, symptom duration, neurogenic claudication, functional status, and patient-reported pain outcomes. The absence of these details may introduce residual confounding and limits our ability to establish clinical equivalence between groups. Second, although propensity score matching was used to balance observable characteristics, treatment selection bias may remain, as patients who choose KM may have stronger preferences for nonsurgical or nonpharmacologic care. To partially account for socioeconomic differences, insurance type was used as a proxy indicator of socioeconomic status; however, direct measures such as income or education are unavailable in claims data and may contribute to unmeasured confounding.

Third, our analysis included only reimbursed KM and WM services. Non-reimbursed treatments—such as herbal decoctions, pharmacopuncture, certain WM procedures, and over-the-counter medications—were not captured, potentially underestimating the full range of treatments received by patients. Fourth, although the washout period was selected to identify newly diagnosed patients, LSS is a chronic and recurrent condition, and a one-year washout may not exclude all prior disease activity.

Finally, while subgroup analyses could offer insight into heterogeneity of treatment effects by age, comorbidity burden, or other factors, we elected not to perform extensive subgroup analyses to avoid multiplicity and overinterpretation in this large administrative dataset. Future studies with richer clinical information and predefined subgroup criteria will be needed to clarify which patient groups benefit most from KM interventions.

From a clinical perspective, these findings also suggest ways in which KM could be incorporated into integrative care pathways for LSS. KM modalities such as acupuncture, Chuna manual therapy, and pharmacopuncture may be positioned as early conservative options before considering opioid therapy or surgical referral, particularly for patients seeking nonpharmacologic management. Integrative medicine approaches—such as shared decision-making between KM and WM providers, cross-disciplinary referrals, and combined rehabilitation programs—may further enhance symptom control while reducing reliance on invasive or opioid-based treatments. Developing such integrative pathways can help translate KM’s real-world benefits into routine clinical practice.

Nonetheless, our findings suggest that KM may offer a meaningful nonsurgical and nonpharmacological treatment option for patients with LSS, particularly in aging populations. Future research should aim to confirm these findings through randomized controlled trials involving patients with comparable clinical characteristics and stricter inclusion criteria.

In conclusion, this nationwide retrospective cohort study used HIRA real-world data to assess the impact of KM treatment on surgery and opioid prescription rates among patients with LSS. The results showed that patients who received KM care had significantly lower long-term rates of both surgery and opioid use compared to those who did not. These findings provide real-world evidence that KM may serve as an effective conservative treatment strategy for LSS, potentially reducing reliance on surgical and pharmacologic interventions. These insights may support informed decision-making by clinicians, patients, and policymakers. However, further large-scale, prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings and strengthen the evidence base for KM in LSS management.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data used in this study come from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) in Korea. To protect patient privacy, access to the data is limited to certified researchers within South Korea, with analysis permitted only within the HIRA system and data export strictly prohibited. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YL, goodsmile8119@gmail.com.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because as the research involved secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Author contributions

W-JH: Investigation, Writing – original draft. H-YG: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. I-HH: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. YL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant numbers: RS-2021-KH111861 and RS-2023-KH140014).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1703911/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Bagley C MacAllister M Dosselman L Moreno J Aoun SG El Ahmadieh TY . Current concepts and recent advances in understanding and managing lumbar spine stenosis. F1000Res. (2019) 8:F1000 Faculty Rev-137. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16082.1

2.

Katz JN Zimmerman ZE Mass H Makhni MC . Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis: a review. JAMA. (2022) 327:1688–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5921,

3.

Kalichman L Cole R Kim DH Li L Suri P Guermazi A et al . Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham study. Spine J. (2009) 9:545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.03.005,

4.

Lurie J Tomkins-Lane C . Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMJ. (2016) 352:h6234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6234

5.

Otani K Kikuchi S Yabuki S Igarashi T Nikaido T Watanabe K et al . Lumbar spinal stenosis has a negative impact on quality of life compared with other comorbidities: an epidemiological cross-sectional study of 1862 community-dwelling individuals. Sci World J. (2013) 2013:590652. doi: 10.1155/2013/590652

6.

Fritz JM Magel JS McFadden M Asche C Thackeray A Meier W et al . Early physical therapy vs usual Care in Patients with Recent-Onset low Back Pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2015) 314:1459–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11648,

7.

Bicket MC Horowitz JM Benzon HT Cohen SP . Epidural injections in prevention of surgery for spinal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Spine J. (2015) 15:348–62. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.10.011,

8.

Alhaug OK Dolatowski FC Solberg TK Lønne G . Predictors for failure after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective observational study. Spine J. (2023) 23:261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.10.010,

9.

Kim CH Chung CK Park CS Choi B Hahn S Kim MJ et al . Reoperation rate after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis without spondylolisthesis: a nationwide cohort study. Spine J. (2013) 13:1230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.069,

10.

Blyth F Deveza LA Ferreira M Ferreira P McLachlan A Naganathan V et al . Efficacy and safety of Oral and transdermal opioid analgesics for musculoskeletal pain in older adults: a systematic review of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Pain. (2018):475.e1–475.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.12.001

11.

Kim D Shin J-S Moon Y-J Ryu G Shin W Lee J et al . Long-term follow-up of spinal stenosis inpatients treated with integrative Korean medicine treatment. J Clin Med. (2020) 10:74. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010074,

12.

Kim K Jeong Y Youn Y Choi J Kim J Chung W et al . Nonoperative Korean medicine combination therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis: a retrospective case-series study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2015) 2015:263898. doi: 10.1155/2015/263898

13.

Lee YJ Shin J-S Lee J Kim M Ahn Y Shin Y et al . Survey of integrative lumbar spinal stenosis treatment in Korean medicine doctors: preliminary data for clinical practice guidelines. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2017) 17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1942-6,

14.

Lee JH Lee H-J Woo SH Park YK Han JH Choi GY et al . Effectiveness and safety of acupotomy on lumbar spinal stenosis: a pragmatic, pilot, randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. (2023) 16:659–68. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S399132,

15.

Kim K Shin K-M Hunt CL Wang Z Bauer BA Kwon O et al . Nonsurgical integrative inpatient treatments for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis: a multi-arm randomized controlled pilot trial. J Pain Res. (2019) 12:1103–13. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S173178,

16.

Jang J-H Park H-J . Effects of acupuncture on neuropathic pain: mechanisms in animal models. Perspect Integr Med. (2022) 1:17–20. doi: 10.56986/pim.2022.09.004

17.

Park T-Y Moon T-W Cho D-C Lee JH Ko YS Hwang EH et al . An introduction to Chuna manual medicine in Korea: history, insurance coverage, education, and clinical research in Korean literature. Integr Med Res. (2014) 3:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2013.08.001,

18.

Cheon C Jang B-H Ko S-G . A review of major secondary data resources used for research in traditional Korean medicine. Perspect Integr Med. (2023) 2:77–85. doi: 10.56986/pim.2023.06.002

19.

Cherkin DC Deyo RA Volinn E Loeser JD . Use of the international classification of diseases (ICD-9-CM) to identify hospitalizations for mechanical low back problems in administrative databases. Spine. (1992) 17:817–25. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199207000-00015,

20.

Quan H Sundararajan V Halfon P Fong A Burnand B Luthi J-C et al . Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. (2005) 43:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83,

21.

Jung J-m Chung CK Kim CH Choi Y Kim MJ Yim D et al . The long-term reoperation rate following surgery for lumbar stenosis: a nationwide sample cohort study with a 10-year follow-up. Spine. (2020) 45:1277–84. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003515,

22.

Frieden TR Houry D . Reducing the risks of relief—the CDC opioid-prescribing guideline. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:1501–4. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1515917,

23.

Cantrill SV Brown MD Carlisle RJ Delaney KA Hays DP Nelson LS et al . Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. (2012) 60:499–525. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.06.013,

24.

Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group AMDG 2015 interagency guideline on prescribing opioids for pain Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group 2015. Available online at: https://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2026).

25.

Oh SN Kim HJ Shim JY Kim K Jeong S Park SJ et al . Tramadol use and incident dementia in older adults with musculoskeletal pain: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:23850. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-74817-3,

26.

Koh W Kang K Lee YJ Kim MR Shin JS Lee J et al . Impact of acupuncture treatment on the lumbar surgery rate for low back pain in Korea: a nationwide matched retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0199042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199042,

27.

Yang MY Kim EJ Nam D Park Y Ha IH Kim D et al . Trends of Korean medicine service utilization for lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis: a 10-year analysis of the 2010 to 2019 data. Medicine (Baltimore). (2024) 103:e38989. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000038989,

28.

Inoue M Kitakoji H Yano T Ishizaki N Itoi M Katsumi Y . Acupuncture treatment for low back pain and lower limb symptoms—the relation between acupuncture or electroacupuncture stimulation and sciatic nerve blood flow. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2008) 5:133–43. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem050,

29.

Li H-L Zhang Y Zhou J-W . Acupuncture for radicular pain: a review of analgesic mechanism. Front Mol Neurosci. (2024) 17:1332876. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2024.1332876,

30.

Hong JY Kim H Lee J Jeon WJ Lee YJ Ha IH . Harpagophytum procumbens inhibits Iron overload-induced oxidative stress through activation of Nrf2 signaling in a rat model of lumbar spinal stenosis. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2022) 2022:3472443. doi: 10.1155/2022/3472443,

31.

Hong JY Kim H Jeon WJ Yeo C Lee J Kim H et al . Human placental extract as a promising epidural therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis: enhancing axonal plasticity and mitigating pain and inflammation in a rat model. JOR Spine. (2025) 8:e70085. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.70085,

32.

Lee JY Park KS Kim S Seo JY Cho H-W Nam D et al . The effectiveness of pharmacopuncture in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a protocol for a multi-centered, pragmatic, randomized, controlled, parallel group study. J Pain Res. (2022) 15:2989–96. doi: 10.2147/jpr.S382550,

Summary

Keywords

lumbar spinal stenosis, Korean medicine, opioid, surgery, real-world data, real-world evidence

Citation

Ha W-J, Go H-Y, Ha I-H and Lee YJ (2026) Effect of Korean medicine treatment on surgery and opioid prescription among patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Front. Med. 13:1703911. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1703911

Received

12 September 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

05 January 2026

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Maria Chiara Maccarone, University of Padua, Italy

Reviewed by

Parhat Yasin, Xinjiang Medical University, China

Jeevani Dahanayake, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ha, Go, Ha and Lee.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yoon Jae Lee, goodsmile8119@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.