Abstract

Background:

Metabolic disorders and neurocognitive diseases frequently co-occur, yet the specific mechanisms driving this comorbidity remain elusive. While epidemiological associations are well-documented, the causal links between these conditions are complex and incompletely understood, necessitating a systems-level investigation into their shared biological architecture.

Methods:

This study integrates large-scale human genetics with experimental in vivo transcriptomics and computational chemistry to elucidate these shared pathways. Specifically, an AD-like murine model was used to experimentally prioritize a core network of 13 dysregulated genes within a pathologically relevant context.

Results:

Network-informed Mendelian randomization identified bidirectional causalities, including a 14% elevated dementia risk from type 2 diabetes and protective effects of obesity against parental Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The study identified a signature encompassing key lipid metabolism hubs APOE, CLU, and LDLR. This signature serves as a critical biological filter, anchoring human genetic associations by providing direct evidence of their dysregulation in a neurodegenerative environment. Subsequent chemical enrichment and molecular docking analyses indicated that these experimentally-prioritized targets are engaged by both therapeutic agents (e.g., valproic acid) and environmental toxins (e.g., benzo[a]pyrene).

Conclusion:

This multi-modal investigation provides a robust framework that converges on a high-confidence, 13-gene signature of lipid dysregulation as a central mechanistic interface, offering a powerful set of prioritized targets for future functional validation and therapeutic development at the metabolic-neurocognitive nexus.

Introduction

Age-related disorders, particularly metabolic and neurocognitive disorder, represent an escalating global health challenge. Neurodegenerative conditions, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as the most prevalent form of dementia, place a profound burden on affected individuals and healthcare systems worldwide (Manly et al., 2022). In parallel, metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), obesity, and hypertension have reached epidemic proportions (Klein et al., 2022; Pasdar et al., 2024). Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate strong associations between these disease classes; for example, midlife obesity and T2D are recognized risk factors for late-life dementia (Marrano et al., 2023; Toledano et al., 2024). However, observational findings are inherently susceptible to confounding and reverse causation, leaving the biological mechanisms and directionality of these relationships incompletely understood (Ezkurdia et al., 2023; Weijie et al., 2024).

Previous efforts to clarify these links have often relied on genetic approaches that use inherited variants as proxies for modifiable exposures, enabling causal inference with reduced confounding (Zhang et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2025; Wang F. et al., 2025). These studies have provided important insights, suggesting that metabolic traits may influence neurodegenerative risk (Domenighetti et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025). However, while bidirectional MR has begun to illuminate these reciprocal influences, such analyses have largely been restricted to isolated, pairwise assessments. Consequently, a systems-level map that models the complex interplay and shared genetic architecture across a network of metabolically-linked neurocognitive disorder remains a critical, unaddressed gap. Moreover, translating statistical associations into actionable biological insight requires integration with functional genomics data to illuminate the molecular processes that mediate these effects (Ebrahim and Davey Smith, 2008; Tyner, 2017).

Here, we present a multi-stage analytical framework designed to map the shared causal architecture between metabolic and neurocognitive disease and to identify biologically meaningful molecular drivers. Critically, to avoid circular reasoning and selection bias, our pipeline begins with hypothesis-free, genome-wide inputs for both genetic (GWAS) and transcriptomic datasets. Rather than funneling data through pre-selected domains, we allowed key pathways to emerge naturally from the intersection of independent data modalities. We first apply a network-guided causal inference strategy to uncover robust, biologically coherent trait–trait relationships and cluster them into functional modules, thereby enhancing both statistical power and interpretability. Genetic variants supporting these relationships are then mapped to putative effector genes. To experimentally prioritize these candidates and validate their dysregulation in a relevant pathological context, we established an AD-like murine model and performed hippocampal RNA-sequencing. This approach enabled us to filter and rank genetically-implicated candidates based on their actual expression changes in a disease-relevant tissue environment, thereby bridging statistical associations with biological plausibility. The resulting set of high-confidence, dysregulated genes is then explored for therapeutic and environmental relevance by mapping their interactions with chemicals and drugs using the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD), followed by molecular docking simulations. These computational analyses are employed not as definitive validation, but to explore the structural plausibility of binding and to generate mechanistic hypotheses regarding how prioritized environmental agents might structurally engage with the identified gene targets.

We hypothesize that anchoring large-scale genetic causal inference with experimental transcriptomic data from an in vivo model will provide a robust framework for identifying a core set of shared molecular pathways underlying the comorbidity of metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. By bridging causal inference with experimental prioritization and mechanistic insight, this study aims to (1) construct a systems-level causal landscape connecting metabolic and neurocognitive disorder, with a primary focus on identifying and dissecting bidirectional relationships that suggest shared feedback mechanisms; (2) experimentally prioritize and characterize the tissue-specific predictive utility of the key genes and pathways mediating these relationships within an in vivo pathological context; and (3) highlight molecular nodes that represent promising candidates for diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive interventions, pending further functional validation studies. A schematic of the analytical strategy is provided in Figure 1 to illustrate the overall workflow.

FIGURE 1

Schematic overview of the multi-stage analytical framework for dissecting the shared causal architecture between metabolic and Neurocognitive Disorder. The analytical pipeline begins with a network-informed, bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to establish robust causal relationships between a curated panel of metabolic and neurodegenerative traits. Significant causal pairs are organized into functional modules. Genetic instruments (SNPs) underlying these causal links are mapped to their putative effector genes. To experimentally validate and prioritize these candidates within a relevant pathological context, we established an AD-like murine model and performed hippocampal RNA-sequencing, generating a high-confidence set of dysregulated genes. In a parallel stream, the biological pathways enriched by the initial set of putative genes are evaluated for functional relevance using a pathway-centric machine learning framework on six disease-specific transcriptomic datasets. In the final stage, the experimentally-prioritized driver genes from our in vivo model are queried against the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) to identify potential interactions with drugs and environmental chemicals. High-priority chemical-gene pairs are then subjected to molecular docking analysis to provide structural evidence supporting these interactions. Overall, this integrated strategy is designed to systematically progress from broad genetic causal inference, through experimental validation in a disease-relevant model, to specific mechanistic insights and the identification of therapeutically relevant molecular targets.

Methods

Phenotype definitions and GWAS sources

To investigate the shared genetic architecture and potential causal pathways connecting metabolic disorders and neurocognitive disorder, we curated a focused panel of phenotypes representing two major categories of age-related disorders. The first category encompassed traits indicative of neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment, including AD and all-cause Dementia. The second category comprised classical metabolic disorders, namely hypertension, obesity, T2D, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), all of which have been implicated in the etiology and progression of cognitive decline.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets were retrieved from publicly accessible repositories, including the IEU OpenGWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/), and the FinnGen consortium (https://www.finngen.fi/en/consortium), ensuring standardized data processing and consistent quality control across studies. Neurodegenerative phenotypes were defined using both algorithm-derived endpoints from the UK Biobank (UKB, https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/) and registry-based clinical outcomes from FinnGen. The UKB-derived trait ieu-b-5067 captured AD status based on a composite definition incorporating hospital admission records, cognitive performance scores, and death registry data, analyzed using the BOLT-LMM framework (Mitchell et al., 2019). From FinnGen, we included three distinct AD endpoints—finn-b-G6_AD_WIDE (broad definition), finn-b-AD_LO (late-onset AD), and finn-b-AD_AM (atypical or mixed AD)—as well as two dementia-related phenotypes, finn-b-KRA_PSY_DEMENTIA (general dementia) and finn-b-F5_ALZHDEMENT (Alzheimer-related dementia).

Metabolic phenotypes were selected for their relevance to systemic vascular and metabolic dysfunction. Hypertension was represented by ukb-b-12493, corresponding to ICD-10 code I10 (essential hypertension), and ieu-b-5144, which defined early-onset hypertension based on internal UKB criteria. Obesity phenotypes included ieu-a-1096 (childhood obesity, EGG consortium) and ebi-a-GCST001475 (adult obesity, GIANT consortium), both derived from the meta-analysis by Bradfield et al. (2012). T2D was represented by four independent datasets: two from the Million Veteran Program (MVP)—ebi-a-GCST90013892 and ebi-a-GCST90013942, analyzed using Firth and saddlepoint approximation (SPA) correction models, respectively (Mbatchou et al., 2021)—and two BMI-adjusted trans-ancestry datasets, ebi-a-GCST007518 and ebi-a-GCST007516, from the meta-analysis by Mahajan et al. (2018). To capture hepatic metabolic contributions, two NAFLD datasets were included: ebi-a-GCST90091033 (Ghodsian et al., 2021) (histologically confirmed liver fat accumulation) and ebi-a-GCST90054782 (imaging-based liver fat content) (Ghodsian et al., 2021). These phenotypes provide important links between adiposity, hepatic lipid metabolism, and systemic inflammation, processes increasingly implicated in neurodegenerative pathology.

This ontology-driven phenotype selection established a robust foundation for investigating potential bidirectional genetic relationships between metabolic dysfunction and neurocognitive decline. Detailed phenotype definitions, sample sizes, ancestry compositions, and SNP coverage are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

TABLE 1

| Trait ID | Trait description | Sample size | PMID | Year | Population | nsnp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ieu-b-5067 | Alzheimer’s disease (UKB, algorithm-defined) | 488,285 | 35564004 | 2022 | European | 12,321,875 |

| finn-b-G6_AD_WIDE | Alzheimer’s disease, wide definition (FinnGen) | — | 34594039 | 2021 | European | 16,380,462 |

| finn-b-AD_LO | Alzheimer’s disease (late onset) | ∼2,670 cases | 34594039 | 2021 | European | 214,871 |

| finn-b-AD_AM | Alzheimer’s disease (atypical/mixed) | ∼800 cases | 34594039 | 2021 | European | 214,893 |

| finn-b-KRA_PSY_DEMENTIA | All-cause Dementia | ∼5,900 cases | 34594039 | 2021 | European | 212,859 |

| finn-b-F5_ALZHDEMENT | Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease | ∼2,200 cases | 34594039 | 2021 | European | 209,487 |

| ukb-b-12493 | Essential hypertension (ICD10: I10) | 463,010 | 29844963 | 2018 | European | 9,851,867 |

| ieu-b-5144 | Early-onset hypertension (UKB) | 462,826 | — | 2024 | European | 12,321,875 |

| ieu-a-1096 | Childhood obesity | 13,848 | 22484627 | 2012 | European | 2,442,739 |

| ebi-a-GCST001475 | Obesity (adult) | 13,848 | 22484627 | 2012 | European | 2,430,514 |

| ebi-a-GCST90013892 | Type 2 diabetes (Firth correction) | 406,831 | 34017140 | 2021 | European | 11,039,026 |

| ebi-a-GCST90013942 | Type 2 diabetes (SPA correction) | 406,831 | 34017140 | 2021 | European | 11,038,957 |

| ebi-a-GCST007518 | T2D (BMI-adjusted) | 298,957 | 29632382 | 2018 | European | 190,208 |

| ebi-a-GCST007516 | T2D (BMI-adjusted) | 298,957 | 29632382 | 2018 | European | 190,208 |

Characteristics of GWAS datasets.

Bidirectional two-sample Mendelian Randomization analysis

Following the curation of GWAS datasets, we conducted a bidirectional two-sample analysis to systematically evaluate the causal relationships between the selected metabolic and neurodegenerative traits. This bidirectional framework was applied in two complementary directions: in the forward analysis, metabolic disorders were treated as exposures and neurodegenerative traits as outcomes; conversely, in the reverse analysis, neurodegenerative traits served as exposures and metabolic disorders as outcomes. To reduce potential confounding from population stratification, all analyses were restricted to individuals of European ancestry.

For each exposure trait, we identified independent genetic instruments by selecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) achieving genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) and applying linkage disequilibrium (LD) clumping (r2 < 0.001 within a 1,000 kb window). Effect estimates for these instruments were then extracted from the outcome GWAS datasets. To ensure valid causal estimates, allele harmonization was performed to align effect alleles between exposure and outcome datasets, resolve strand ambiguity for palindromic SNPs, and remove instruments that could not be reliably matched.

The primary causal effects were estimated using the random-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method. Robustness was evaluated using several sensitivity analyses: MR-Egger regression to test for directional pleiotropy (a non-significant intercept, P > 0.05, indicating absence of bias), Cochran’s Q statistic to quantify heterogeneity among SNP-specific estimates, leave-one-out analysis to detect disproportionately influential instruments, and Radial MR (both IVW- and MR-Egger-weighted) to identify and down-weight outlier SNPs.

A causal association was considered robust and reported as a qualified finding only if it met three stringent criteria: (1) a statistically significant effect in the IVW analysis (P < 0.05); (2) no evidence of directional pleiotropy (MR-Egger intercept P > 0.05); and (3) no significant heterogeneity across instruments (Cochran’s Q test P > 0.05). To ensure the validity of the causal direction and address the potential for bias in highly pleiotropic regions, we rigorously applied Steiger filtering (Hemani et al., 2017). This procedure calculates the variance explained in the exposure versus the outcome, removing instruments that explain more variance in the outcome to mitigate reverse causation. Furthermore, regarding the APOE locus (chr19:44.9–45.9 Mb), while we acknowledge its extensive pleiotropy, we elected to retain instruments within this region to capture the complete genetic architecture shared between lipid metabolism and neurodegeneration (Kunkle et al., 2019). The application of Steiger filtering ensures that these powerful genetic signals are statistically anchored to the hypothesized causal direction rather than being artifacts of reverse causality. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from the beta coefficients for all qualified associations. All statistical analyses were performed in R using the “TwoSampleMR” (Hemani et al., 2018) and “RadialMR” (Bowden et al., 2018) packages.

Network-guided integration and filtering

To integrate the results systematically, we collated MR outputs from multiple independent analyses, harmonizing them into two master tables representing forward and reverse directions. Each record was assigned a unique identifier reflecting its original source. Using the forward-direction results, we constructed a trait-level causal network, in which nodes represented traits (exposures or outcomes) and edges represented statistically significant causal links. The Walktrap community detection algorithm was applied to partition this network into densely connected modules, capturing groups of biologically or functionally related traits.

We then applied a stringent network-informed filtering strategy to prioritize high-confidence causal relationships. Specifically, we defined a set of “core network relationships,” representing exposure–outcome pairs in which both traits resided within the same module, reasoning that intra-modular relationships were more likely to reflect coherent biological mechanisms. This curated core set was used as a bidirectional filter: in the forward analysis, only pairs matching the core set were retained, whereas in the reverse analysis, only those pairs exactly inverting a core forward relationship (i.e., exposure and outcome reversed) were retained. The resulting dataset comprised bidirectionally evaluated, module-consistent relationships. Each entry was annotated with its network module identifier and subsequently used for downstream analyses.

Identification, prioritization, and functional annotation of key genetic instruments

To determine the genetic variants underlying the observed causal relationships, we applied a multi-stage process encompassing SNP filtering, prioritization, and functional annotation. In the initial step, instrumental SNPs were selected using a stringent network-guided criterion derived from the previously defined core network relationships. These core relationships represent exposure–outcome pairs in which both traits reside within the same computationally defined biological module. For forward-direction analyses, a SNP was retained only if its exposure–outcome pair matched a core network relationship. For reverse-direction analyses, the selection criterion was symmetrically applied, retaining SNPs only when their exposure–outcome pair precisely inverted a core forward relationship. This approach ensured that only SNPs linked to robust, module-supported causal pathways were carried forward for subsequent analyses.

The retained SNPs were then prioritized based on their frequency of association, calculated as the number of distinct module-supported causal relationships in which each SNP served as an instrument. This frequency-based prioritization was performed separately for each original data source and for each causal direction (forward and reverse), enabling identification of robust instruments repeatedly implicated across multiple independent causal tests.

The final analytical step involved functional annotation of the prioritized SNPs to identify candidate effector genes. Positional mapping was performed using the human genome build hg19 as a reference. A candidate gene was assigned to a SNP if it was the closest annotated gene located within a 50 kb flanking region upstream or downstream of the SNP’s genomic coordinates. These functionally annotated SNP–gene pairs provided the foundation for subsequent biological pathway and network analyses.

Pathway and ontology enrichment analysis of key genes

To investigate the collective biological functions of the prioritized genes, we performed formal gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify biological pathways and ontology terms significantly over-represented within our gene lists. The reference for this analysis was the C5 ontology gene sets collection from the Molecular Signatures Database (Liberzon, 2014; Castanza et al., 2023) (MSigDB v2025.1. Hs, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb). This resource integrates curated gene sets from two primary ontology sources: the Gene Ontology (GO) project, covering its three core domains—Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF)—and the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO). To ensure functional relevance, the MSigDB C5 collection excludes overly broad gene sets (more than 2,000 members) and overly specific sets (fewer than five members). The analytical background was defined as the complete set of unique genes represented across all pathways in this collection.

The enrichment analysis was conducted separately for each group defined by a unique combination of original GWAS data source and direction of causal analysis (forward or reverse). For each group, we compiled a query list of unique key genes identified in the preceding SNP prioritization step. The statistical significance of enrichment for each gene set was evaluated using a one-sided hypergeometric test, which measures whether the observed overlap between the query genes and a given pathway exceeds the overlap expected by random chance. To correct for multiple testing across thousands of pathways, raw P-values from the hypergeometric tests were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedure. Gene sets were considered significantly enriched if they met the threshold of an FDR-adjusted P < 0.05.

Transcriptomic data acquisition and differential expression analysis

To characterize transcriptional alterations associated with disease states, we obtained six publicly available transcriptomic datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/): GSE5281 (AD) (Readhead et al., 2018), GSE140830 (all-cause Dementia), GSE122063 (VaD) (McKay et al., 2019), GSE184050 (T2D) (Chen et al., 2022), GSE262828 (Hypertension) (Ananthamohan et al., 2024), and GSE77962 (obesity) (Tareen et al., 2020). Each dataset provided pre-processed gene expression matrices and metadata specifying sample diagnosis and clinical status. Detailed dataset information, including sample size, tissue origin, and experimental platform, is provided in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2.

TABLE 2

| Disease | GEO NO. | Sample size | Description | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | GSE5281 | Total: 161 Controls: 74 Cases: 87 (cortical layer III neurons) |

This study profiled gene expression to identify molecular signatures of AD and aging. To eliminate tissue heterogeneity, laser capture microscopy (LCM) was used to isolate layer III pyramidal cells from six specific brain regions (entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, medial temporal gyrus, posterior cingulate, superior frontal gyrus, and primary visual cortex). Gene expression was measured using Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 arrays. | 17077275; 18332434; 29937276; 18270320 |

| Dementia | GSE112681 | Total: 542 Controls: 281 Cases: 261 (bvFTD: 80, PSP: 54, nfvPPA: 47, svPPA: 44, CBS: 36) |

This study investigates the role of peripheral inflammation in dementia by analyzing gene expression profiles from total RNA obtained from peripheral blood. It compares a diverse set of dementia patients—including multiple Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) spectrum disorders—to healthy controls to identify transcriptional signatures of inflammation. | 29939990; 31118040 |

| VaD | GSE131282 | Total: 136 Controls: 44 Cases: 92 (Alzheimer’s disease: 56, vascular dementia: 36) |

This study profiled gene expression on post-mortem frontal and temporal cortex tissue, comparing vascular Dementia (VaD), Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and non-demented controls. VaD cases were selected for low Braak staging to minimize AD comorbidity, while AD and control cases were confirmed to have no infarcts. Gene expression was measured using Agilent human 8 × 60k v2 microarrays.c | 30990880 |

| Hypertension | GSE262828 | Total: 89 Low blood pressure: 43 Mid/Elevated blood pressure: 13 High blood pressure: 33``` |

This study aims to identify molecular mechanisms of target organ Damage (TOD) in youth with primary hypertension. Using high-throughput sequencing (RNA-seq), it profiled gene expression in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from youth stratified by blood pressure levels and the presence of TOD. The study is part of a larger multi-omics investigation to define circulatory regulators involved in blood pressure-mediated TOD. | 38948714 |

| Obesity | GSE77962 | Total: 152 (from 53 individuals) Baseline: ∼51 (inferred) After weight loss period: 50 After weight stable period: 51 |

This randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of weight loss rate on the adipose tissue transcriptome. Overweight and obese individuals were assigned to either a low-calorie diet (LCD) or a very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) to achieve similar total weight loss. Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies were collected at baseline, after the weight loss period, and after a subsequent weight stabilization period, with gene expression analyzed by microarray.c | 30380678; 27840413; 32015415 |

| T2D | GSE28894 | Total: 116 Controls: 66 Cases: 50 |

This longitudinal study investigated gene expression changes in whole blood to identify transcriptional signatures associated with the progression to type 2 Diabetes (T2D). Using high-throughput sequencing (RNA-seq), it compared subjects who transitioned to T2D over time against controls who did not. A key gene network associated with T2D transition status was identified and subsequently validated. | 35157052 |

Characteristics of gene expression datasets.

To ensure consistency across datasets, a standardized analysis workflow was applied. Importantly, to avoid artifacts arising from tissue heterogeneity and batch effects, we did not merge the raw expression matrices. Instead, each dataset underwent independent normalization and differential expression (DE) analysis specific to its tissue of origin (brain, blood, or adipose). This strategy ensures that the identified gene signatures reflect robust disease-associated changes within each specific biological context, rather than technical disparities between tissue types. Samples were classified into two groups based on study metadata: a “disease” group representing the pathological condition of interest and a “healthy control” (HC) group. Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was performed using the “limma” (Ritchie et al., 2015) package in R, suitable for both microarray and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data. For each gene, a linear model was fitted to evaluate expression differences between disease and control groups using a design matrix constructed to capture group effects. This strategy ensures that the identified gene signatures reflect robust disease-associated changes within each specific biological context, distinguishing shared pathological mechanisms (e.g., lipid dysregulation) from generic systemic inflammation.

To enhance statistical power and stabilize variance estimates, particularly in datasets with modest sample sizes, empirical Bayes moderation was applied to model coefficients using the eBayes function. This procedure moderates standard errors by borrowing information across all genes, providing robust estimates of differential expression.

For each gene, the analysis generated log2 fold-change (logFC) values to quantify the magnitude of expression differences, along with associated P-values and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)–adjusted P-values. These results provided both the effect size and statistical significance for transcriptional changes between disease and control cohorts.

Pathway-centric machine learning framework

To build predictive models and identify key driver genes from the complex transcriptional landscapes of multiple disease states, we utilized six publicly available transcriptomic datasets covering both neurodegenerative conditions (AD, all-cause Dementia, and VaD) and metabolic disorders (T2D, Hypertension, and Obesity). From the biologically relevant gene sets identified through prior functional enrichment analyses, we selected subsets specifically associated with each disease category. Specifically, for each disease, the initial feature space for modeling was defined as the union of all genes belonging to pathways that were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) in the corresponding genetic analysis. These curated gene subsets served as the feature space for model construction, enabling the assessment of their predictive value for disease risk and the identification of potential molecular drivers.

Prior to model training, we applied a standardized preprocessing and feature selection pipeline to optimize the input data for each gene set. This pipeline consisted of three sequential steps: (1) Standardization, where gene expression values were transformed using a Z-score to ensure all features were on a comparable scale; (2) Low-Variance Filtering, to remove genes with near-constant expression that offer little discriminatory information; and (3) Univariate Feature Selection, which employed an ANOVA F-test to select the most significant genes associated with the disease status, dynamically adjusting the number of features to ensure a focused yet sufficiently complex feature set for modeling. This rigorous feature selection step was critical to mitigate the curse of dimensionality and reduce the risk of overfitting by focusing the models only on the most informative, pathway-restricted molecular features. To create a focused yet informative feature set, only genes with an ANOVA F-test P-value < 0.01 were retained for model training. This stringent, data-driven criterion ensures that only features with a strong univariate association with the phenotype are included, thereby reducing model complexity and the risk of including noisy variables.

Machine learning model repertoire

To robustly assess the predictive potential of our selected gene features, we employed a diverse suite of machine learning algorithms. This multi-model strategy was chosen to mitigate the risk of model-specific bias and to systematically explore a wide range of underlying data structures, from simple linear relationships to complex, non-linear interactions. The repertoire included.

Logistic Regression–a linear model providing a robust, interpretable performance baseline to establish benchmark performance.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) – more complex non-linear models capable of capturing intricate decision boundaries and non-parametric relationships, respectively.

A variety of powerful ensemble methods, known for their high accuracy and inherent robustness against overfitting by aggregating predictions from multiple base learners. This included Random Forest and Extra Trees, which are parallel tree-based ensembles, as well as Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, and CatBoost, which are sequential ensembles that iteratively improve predictions.

Finally, to test the capacity to capture high-order feature interactions that might be missed by traditional algorithms, we included state-of-the-art deep learning models specifically designed for tabular data. These were TabNet, which uses sequential attention to enhance interpretability, and FT-Transformer (Fourier Transform Transformer). While computationally intensive, the inclusion of models like FT-Transformer was justified by their potential to uncover novel predictive patterns in complex transcriptomic data, even with modest sample sizes, when combined with our rigorous cross-validation framework.

Model evaluation and gene prioritization

A rigorous framework was implemented to evaluate model performance and identify key driver genes. All models were assessed using a 10-fold stratified cross-validation strategy to provide a robust and unbiased estimation of model performance on unseen data and to explicitly mitigate the risk of overfitting. During this process, we carefully monitored for significant discrepancies between training and validation performance metrics, which would indicate potential overfitting. The consistent performance observed across folds confirmed the generalizability of our models. Model performance was quantified using a comprehensive suite of metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), accuracy, F1-score, precision, recall, and Cohen’s kappa. For each pathway-specific model, a composite rank was derived by summing the individual performance ranks across all metrics, enabling the identification of models that consistently exhibited superior predictive performance.

To prioritize genes, we performed a hierarchical feature importance analysis restricted to the top five models as determined by the composite rank. Feature importance was extracted using methods appropriate to each model architecture: intrinsic importance scores were used for models with built-in ranking mechanisms (e.g., tree-based ensembles and linear models), whereas SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used for complex, non-linear models to estimate the marginal contribution of each gene to model predictions. The final comprehensive importance score for each gene was calculated by weighting its normalized importance from each of the top five models by the corresponding model’s composite rank, yielding a robust, performance-weighted measure of gene relevance within the diagnostic signature.

The machine learning model repertoire and evaluation framework were implemented using the following Python packages: pandas: v2.2.2, NumPy: v1.26.4, scikit-learn: v1.5.0, XGBoost: v2.1.0, CatBoost: v1.2.5, PyTorch: v2.3.0, pytorch_tabnet: v4.1.0, rtdl: v0.0.13, and SHAP: v0.45.0.

Prioritization of key disease-associated genes

To derive a high-confidence list of key driver genes from the machine learning results, we implemented a multi-stage, data-driven prioritization pipeline. This approach integrated evidence from the independently trained models for each disease cohort. By comparing high-performing features across these distinct, tissue-specific models, we identified shared molecular drivers that transcend tissue boundaries. This result-level integration allows for the detection of convergent pathological mechanisms—such as lipid dysregulation—while filtering out tissue-specific noise or generic systemic inflammation markers that might dominate a merged dataset.

The process began by quantifying model reliability through a Composite Model Performance Score. For each model within each pathway-specific gene set, six performance metrics (accuracy, AUC, F1-score, precision, recall, and Cohen’s kappa) were normalized to a 0–1 scale and averaged to produce a single score representing the overall predictive utility of the model.

Next, we calculated a Performance-Weighted Importance Score for each gene by multiplying its raw feature importance (as computed in the machine learning pipeline) by the Composite Model Performance Score of the model that identified it. This ensured that gene importance was up-weighted when derived from a robust, high-performing model and down-weighted when originating from a lower-performing one.

A final Gene Prioritization Score was then calculated for each gene within each disease dataset by summing its Performance-Weighted Importance Scores across all relevant pathways and models. This aggregation rewarded genes that were consistently identified as important across multiple predictive contexts. Genes were ranked in descending order based on this score, and a stringent selection criterion was applied: only the top 1% of genes for each disease context were retained for downstream analysis, yielding a high-confidence list of key driver genes.

Chemical-gene interaction network analysis

To explore the therapeutic potential of the prioritized genes, we interrogated the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) (Wiegers et al., 2025) (http://ctdbase.org/), a curated resource detailing chemical–gene interactions and their relevance to human health. As of the July 2025 release, the CTD contained more than 3.1 million manually curated chemical–gene interactions, encompassing approximately 15,000 unique chemicals and 57,000 genes. This dataset is augmented by systematic integration with other authoritative bioinformatics resources, including NCBI Gene, KEGG, Reactome, GO, PubChem, ChemIDplus, and PubMed.

For each disease context, we identified the top five hub chemicals, defined as those interacting with the largest number of prioritized gene targets. These chemicals were classified as either “Drugs” or “Compounds” according to CTD annotations, enabling differentiation between potential therapeutic agents and environmental exposures. For each hub chemical, we constructed and analyzed chemical–gene interaction networks, representing chemicals and genes as nodes and curated interactions as edges. Each interaction was further annotated by its reported mode of action (e.g., activation, inhibition, or binding). To detect latent structural relationships, we applied the Louvain community detection algorithm, which identified densely interconnected modules of chemicals and genes.

Finally, to facilitate cross-disease comparisons, we integrated hub chemicals and their gene targets from all six disease contexts into a single bipartite network. This unified framework enabled the identification of shared therapeutic targets, potential pleiotropic effects, and molecular cross-talk among metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders.

Animal model and behavioral assessment

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hubei Minzu University. Ten-week-old, specific-pathogen-free (SPF) male Kunming mice (n = 5 per group) were sourced from Sibeck Biotechnology (Henan, China). Following a 7-day acclimatization period, an oxidative stress-induced model of aging-associated cognitive impairment, which mimics key features of sporadic AD, was established. Unlike transgenic models that replicate familial amyloid pathology, the D-galactose/sodium nitrite (D-gal/NaNO2) regimen was selected to specifically induce systemic oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic dysregulation—the core shared pathways identified in our computational analysis (Rehman et al., 2017). The model group received daily subcutaneous injections of D-galactose (120 mg/kg/day) and sodium nitrite (55 mg/kg/day) for 60 consecutive days. The control group received vehicle injections. Both D-galactose and sodium nitrite were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Cognitive function was evaluated using the Morris Water Maze (MWM) test. For the spatial learning acquisition phase, mice were trained for five consecutive days to locate a hidden platform, with the escape latency recorded in each trial. On the sixth day, a probe trial was conducted by removing the platform to assess memory retention. The frequency of platform crossings and the time spent in the target quadrant were quantified as primary measures of spatial memory. All animal experiments were conducted under the ethical guidelines of the Hubei Minzu University Institutional Review Board.

Molecular analyses of hippocampal tissue

Following behavioral assessments, mice (n = 3 per group) were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). Euthanasia was confirmed by the absence of corneal reflex, respiration, and heartbeat. Immediately following euthanasia, hippocampal tissues were rapidly dissected, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent molecular analysis (Meng et al., 2021).

Total RNA was extracted from the hippocampal tissue and subjected to global transcriptomic profiling. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on an Illumina platform. The resulting raw sequencing data underwent a standard bioinformatic pipeline, which included quality control, alignment to the reference genome (e.g., GRCm39), and transcript quantification. Differential expression analysis was then performed to identify significant transcriptomic alterations between the model and control groups.

To validate key gene expression changes identified by RNA-seq, we quantified the relative mRNA levels of the neuronal synapse marker,

Grin2a, and the microglial inflammation marker,

Tnfrsf11b. Expression was normalized to the endogenous control gene,

Gapdh. The specific primers used for amplification were as follows:

Grin2a:

Forward: 5′-ACGTGACAGAACGCGAACTT-3′

Reverse: 5′-TCAGTGCGGTTCATCAATAACG-3′

Tnfrsf11b:

Forward: 5′-CCTTGCCCTGACCACTCTTAT-3′

Reverse: 5′-CACACACTCGGTTGTGGGT-3′

Gapdh:

Forward: 5′-GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA-3′

Reverse: 5′-TGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCC-3′

Molecular docking analysis of prioritized chemical-target pairs

Molecular docking simulations were performed to predict binding affinities and characterize potential interaction modes between prioritized chemicals and their corresponding protein targets. Candidate chemical–protein pairs were selected based on curated interactions from the CTD, ensuring that each chemical was linked to at least one high-priority gene identified by the machine learning analysis and enriched across multiple disease contexts.

Three-dimensional protein structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/), and structural preparation was performed using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software. Preprocessing steps included removal of co-crystallized water molecules and ligands, addition of hydrogen atoms, and assignment of protonation states of ionizable residues under physiological pH (7.4) using the Protonate 3D module. Canonical 2D ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database, converted into 3D conformations, and energy-minimized using the AMBER10:EHT force field to generate stable geometries.

Docking was carried out using a rigid-receptor, flexible-ligand approach. Binding sites were identified using the Site Finder module, and ligand placement was performed using the Triangle Matcher algorithm, generating 30 distinct binding poses per ligand. These poses were scored using the London dG scoring function, which estimates the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG). For each chemical–target pair, the top-scoring pose representing the most favorable binding configuration was selected for detailed characterization, including non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and π–π stacking, to elucidate the molecular basis of ligand binding.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v4.3.0) and Python (v3.10). Genome-wide association signals were filtered at P < 5 × 10−8. Differential expression analyses applied the limma package with empirical Bayes moderation and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction (P < 0.05). Machine learning models were evaluated using 10-fold stratified cross-validation, with model performance assessed by AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Cohen’s kappa. Functional enrichment analyses used a one-sided hypergeometric test with FDR adjustment (P < 0.05). Functional enrichment analysis of prioritized genes employed a one-sided hypergeometric test with FDR adjustment (P < 0.05). Chemical–gene network analyses used the Louvain community detection algorithm to identify functionally coherent interaction modules. Molecular docking results were evaluated based on London dG binding scores, with lower ΔG values indicating higher binding affinity.

Results

Network-informed Mendelian randomization reveals complex causal architectures

Our network-informed MR analysis partitioned the causal landscape into six functionally distinct modules, uncovering a complex architecture of risk-conferring, protective, and bidirectional relationships (Figure 2A; Supplementary Table S3). A comprehensive summary of each module is presented in Table 3, while the main text below highlights the key biological narratives, supported by their most representative statistical evidence.

FIGURE 2

Mendelian randomization uncovers causal links and shared genetic architecture between metabolic and neurocognitive disorder. (A) The Mendelian Randomization association network systematically maps the causal architecture linking metabolic and Neurocognitive Disorder. The analysis partitions significant associations into six functionally distinct modules, indicated by edge color. This data-driven network reveals a complex landscape of both risk-conferring and protective effects. For instance, Module 1 highlights the contrasting effects of hypertension, which is protective against one dementia subtype while being a risk factor for another. Modules 2 and 4 are characterized by protective links, where obesity is associated with a reduced risk of AD. In contrast, Module 5 identifies a single, potent risk association between primary hypertension and early-onset AD. The largest and most interconnected cluster, Module 6, demonstrates significant bidirectional causality between Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and dementia, indicative of an intricate feedback mechanism between these conditions. (B) Forest plots display the most significant Mendelian Randomization results, filtered to show up to the top 10 associations per module, ranked by p-value. For modules containing more than 10 significant findings, the label indicates that the top 10 are shown (e.g., Module 6, Top 10 of 100). The source metabolic disease category (Hypertension, T2D, or Obesity) for each association is indicated by the color of the exposure label on the y-axis. These plots powerfully illustrate key findings, such as the bidirectional relationship in Module 6, where forward analysis (T2D → Dementia) shows increased risk (OR > 1) and reverse analysis (Dementia → T2D) shows a protective effect (OR < 1). (C) Key SNP-Gene Chord Diagrams map the genetic instruments (SNPs) to their annotated genes for the primary causal associations. These diagrams reveal the genetic architecture mediating the interplay between metabolic disorders and AD/Dementia. • Hypertension and Dementia/AD: In the forward direction (Hypertension → Dementia/AD), instrumental variants map to genes including ABHD16A, APOM, MTHFR, and NPPA. In the reverse direction, the genetic instruments converge primarily on the APOE/TOMM40 locus, with other implicated genes including PVRL2 and BCAM. • Obesity and Dementia/AD: Forward analysis implicated well-established obesity-related loci, including FTO, BDNF, and TMEM18. The reverse analysis was dominated by instruments in the APOE/TOMM40 region, along with other known AD-risk genes such as BIN1, CLU, and PVRL2. • T2D and Dementia/AD: Forward analysis revealed SNPs in genes related to glucose metabolism (GIPR, ATP6V1G2) and immune pathways (PSORS1C1). In the reverse direction, the APOE/TOMM40 locus was again central, with additional implicated genes like RELB and PVRL2, suggesting complex interactions between neurodegeneration and glucose homeostasis.

TABLE 3

| Module ID | Core biological theme | Key causal relationship | Key biological Takeaway | Representative effect (OR [95% CI]) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Contrasting effects of hypertension on Dementia | Early-onset hypertension → ↓ Lewy body Dementia; early-onset hypertension → ↑ Atypical/Mixed AD | Hypertension exhibits subtype-specific effects, conferring strong protection against one form of dementia while dramatically increasing risk for another, suggesting distinct underlying vascular pathologies. | 1.71 × 10−8 [1.86 × 10−14–0.016]; 5.66 × 108 [3.05–1.05 × 1017] |

0.011; 0.038 |

| 2 | Protective effects of metabolic traits on familial AD | Obesity → ↓ parental history of AD; T2D → ↓ parental history of AD | Genetic predisposition to obesity and T2D is paradoxically associated with a reduced risk of having a parental history of AD, hinting at complex genetic interactions or survival biases. | 0.94 [0.89–0.996]; 0.96 [0.93–0.994] |

0.035; 0.020 |

| 3 | Nuanced and bidirectional Obesity-AD links | Class 2 obesity → ↑ AD risk; childhood obesity → ↓ AD risk | The effect of obesity on AD is context-dependent: Severe adult obesity slightly increases risk, while childhood obesity is protective, suggesting different mechanisms related to timing and severity. | 1.0005 [1.0002–1.0009]; 0.52 [0.29–0.93] |

0.0035; 0.028 |

| 4 | Consistent protective effect of obesity on AD | Obesity/Hyperalimentation → ↓ AD risk | Multiple genetic definitions of obesity consistently show a protective causal effect against developing AD, challenging the conventional view of obesity as a universal risk factor. | 0.90 [0.86–0.95] | 1.12 × 10−5 |

| 5 | Potent hypertension risk for early-onset AD | Essential hypertension → ↑ AD risk | A strong, specific causal link exists where primary hypertension dramatically increases the risk of early-onset AD, highlighting a critical role for vascular health in this aggressive form of the disease. | 32.17 [1.42–729.21] | 0.029 |

| 6 | Bidirectional T2D-Dementia interplay | T2D → ↑ all-cause Dementia; AD → ↓ T2D risk (protective) | Reveals a complex feedback loop: while T2D is a causal risk factor for dementia, the genetic liability for AD, in turn, confers a protective effect against developing T2D. | 1.14 [1.07–1.21]; 0.96 [0.94–0.98] |

3.29 × 10−5; 3.36 × 10−5 |

Summary of causal modules linking metabolic and neurocognitive phenotypes identified by network-informed mendelian randomization.

The causal influence of hypertension proved to be remarkably potent and context-dependent. It emerged as a potential causal risk factor for early-onset alzheimer’s disease (AD), increasing the risk over 30-fold (Module 5; ukb-b-12493 → finn-b-AD_EO_EXMORE; OR = 32.17; 95% CI: 1.42–729.21; P = 0.029). While the primary IVW analysis yielded a notably high odds ratio (OR = 32.17), the extremely wide confidence intervals (95% CI: 1.42–729.21) indicate substantial statistical uncertainty. This magnitude likely reflects the “winner’s curse” phenomenon often observed in MR analyses when exposure and outcome sample sizes are vastly disproportionate (Burgess et al., 2019). Therefore, we interpret this not as a precise clinical risk estimate, but as a robust qualitative signal indicating that early vascular dysregulation significantly elevates AD trajectory. Yet, it also exhibited a paradoxical, subtype-specific effect, simultaneously conferring profound protection against Lewy Body Dementia (Module 1; ieu-b-5142 → ebi-a-GCST90001390; OR = 1.71 × 10−8; P = 0.011) while dramatically increasing the risk for atypical or mixed AD (ieu-b-5142 → finn-b-AD_AM_EXMORE; OR = 5.66 × 108; P = 0.038). These findings strongly suggest that the impact of vascular health on neurodegeneration is highly specific to the underlying dementia pathology.

Our findings on obesity challenged its conventional role as a straightforward risk factor. Across multiple genetic definitions, obesity consistently demonstrated a protective causal effect against AD, with the most significant association observed for obesity with hyperalimentation (Module 4; finn-b-E4_OBESITY_HYPER → ebi-a-GCST90027158; OR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.86–0.95; P = 1.12 × 10−5). This protective signal was further nuanced by a context-dependent relationship where childhood obesity was strongly protective (Module 3; ieu-a-1096 → finn-b-AD_U_EXMORE; OR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.29–0.93; P = 0.028), while severe class 2 adult obesity conferred a marginal but statistically significant risk (ieu-a-91 → ieu-b-5067; OR = 1.0005; 95% CI: 1.0002–1.0009; P = 0.0035). Together, these results indicate that the timing and nature of adiposity are critical determinants of its effect on neurocognitive health.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for systemic interplay was found in Module 6, which uncovered a significant bidirectional feedback loop between Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and dementia. While genetic liability for T2D consistently increased the risk for all-cause dementia (ebi-a-GCST90013892 → finn-b-F5_DEMENTIA; OR = 1.14; 95% CI: 1.07–1.21; P = 3.29 × 10−5), a reverse causal effect was also robustly evident: a genetic predisposition for AD was, in turn, protective against the development of T2D (finn-b-G6_ALZHEIMER_EXMORE → ebi-a-GCST90013942; OR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94–0.98; P = 3.36 × 10−5). This reciprocal relationship points to a deeply integrated, shared pathophysiology between central glucose metabolism and neurodegenerative processes (Figures 2A,B; Supplementary Table S4).

In addition to these core modules, our analysis identified a protective causal effect of dementia liability on the risk of NAFLD. Genetic liability for a paternal history of AD/Dementia (ukb-b-323), for instance, was associated with a striking reduction in the odds of imaging-defined NAFLD (ebi-a-GCST90054782) (OR = 0.0007; 95% CI: 3.22 × 10-5–0.014; P = 2.26 × 10−6). This protective signal was consistent across multiple dementia definitions, including “Any dementia” (finn-b-KRA_PSY_DEMENTIA) (OR = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.80–0.89; P = 2.49 × 10−10). While this dementia-to-NAFLD protective link represents a highly significant finding, its unidirectional nature places it in a distinct mechanistic category from the reciprocally-linked metabolic-neurocognitive axes that form the core of our investigation. To maintain a focused analytical scope on these bidirectional feedback loops, which we hypothesized represent the most tightly integrated shared pathologies, we prioritized the symmetric relationships for our initial multi-omics integration. This approach allows for a coherent dissection of the shared molecular architecture underlying these specific reciprocal effects. However, we acknowledge that the protective effect on NAFLD is a critical observation that highlights a potentially distinct biological pathway. It was therefore set aside not due to a lack of importance, but as a key finding that warrants a dedicated, separate investigation to unravel its unique molecular drivers, which may differ from the shared mechanisms explored here. All MR and sensitivity analysis results are presented in Supplementary Tables S5–S8.

Identification of key genetic loci driving causal associations

To dissect the molecular underpinnings of these causal relationships, we investigated the genetic instruments and their annotated genes, providing insights into the genetic architecture mediating the interplay between metabolic disorders and neurocognitive disorder.

For Hypertension and AD/Dementia associations, forward-direction analysis (metabolic exposure to neurodegenerative outcome) identified instrumental variants, including SNPs such as rs1052486, rs1077394, and rs750332, mapping to genes ABHD16A, AIF1, and APOM. Additional loci included rs115740542 and rs198851 (associated with HFE and HIST1H1E) and rs12567136 and rs149764880 (linked to MTHFR and NPPA). In the reverse direction (neurodegenerative exposure to metabolic outcome), genetic instruments primarily converged on the APOE/TOMM40 locus, with SNPs such as rs429358, rs769449, and rs2972558. Other implicated genes included PVRL2 (rs2972558) and BCAM (rs2972558), suggesting roles for lipid metabolism and neuronal adhesion pathways.

For Obesity and AD/Dementia associations, forward-direction analysis implicated obesity-related loci, including variants within or near the FTO gene (rs11075989, rs1121980, rs1558902) and the BDNF gene (rs11030104, rs11030112, rs2030323). Other genes included TMEM18 (rs12623218, rs13393304), frequently associated with body mass index. In the reverse direction, instruments were predominantly in the APOE/TOMM40 region (rs112019714, rs117310449, rs190651665), with additional genes BIN1 (rs6733839), CLU (rs1532277, rs867230), and PVRL2 (multiple SNPs), indicating genetic interplay between AD and obesity.

For T2D and AD/Dementia associations, forward-direction analysis revealed SNPs in genes related to glucose metabolism, such as GIPR (rs10408179, rs10420309) and ATP6V1G2 (rs2857605, rs3130924). Additional instruments were near PSORS1C1 (rs1065461, rs2233978, rs3132520) and VNN2 (rs7773338). In the reverse direction, the APOE/TOMM40 locus was central (rs429358, rs112784534, rs769449), with additional genes RELB (rs35080293, rs6509191) and PVRL2 (multiple SNPs), suggesting complex interactions between neurodegenerative pathways and glucose homeostasis (Figure 2C; Supplementary Table S9).

Genetic drivers and their recurrence in causal networks

To elucidate the genetic underpinnings of the causal networks between metabolic disorders and neurocognitive disorder, we conducted an intersection analysis of instrumental SNPs and prioritized them by recurrence frequency across significant MR tests. This analysis revealed both unique and shared genetic drivers, highlighting asymmetry in the robustness of genetic signals across forward and reverse causal directions.

In the forward direction (metabolic disorders to AD/Dementia), large, distinct SNP sets were identified: 496 unique SNPs supported the hypertension-to-AD/Dementia network (e.g., rs74661587, rs12258967), 478 supported the T2D-to-AD/Dementia network (e.g., rs10830963, rs2796441), and 39 supported the obesity-to-AD/Dementia network (e.g., rs7138803, rs4854344). The T2D-to-AD/Dementia network exhibited the most robust genetic signal, with highly recurrent SNPs including rs10830963 (frequency = 79), rs2796441 (frequency = 74), and rs11708067 (frequency = 69), averaging 63.5 for the top 10 SNPs. In contrast, the obesity-to-AD/Dementia network had a top SNP, rs7138803 (frequency = 8), and the hypertension-to-AD/Dementia network had rs74661587 (frequency = 5), indicating less concentrated genetic signals.

In the reverse direction (AD/Dementia to metabolic disorders), smaller SNP sets were observed: 67 for obesity (e.g., rs7384878, rs10933431), 25 for T2D (e.g., rs111371860, rs147963283), and 3 for hypertension (e.g., rs2230288, rs6599388, rs7680557). The AD/Dementia-to-T2D network showed the highest recurrence, with rs429358 (APOE, frequency = 19) and rs111371860 (frequency = 18). The AD/Dementia-to-obesity network included SNPs like rs10792832, rs6733839 (BIN1), and rs7384878 (frequency = 5). The AD/Dementia-to-hypertension network was the most diffuse, with rs12984643 and rs429358 (APOE) each at a frequency of 2 (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3

Genetic architecture of causal networks: shared snps and high-frequency drivers. (A) A cross-disease comparative analysis of instrumental SNPs from the six primary causal pathways. The bar chart quantifies the number of SNPs unique to each causal pathway (colored bars) and those shared between pathways (grey bars). In the forward direction, large sets of unique SNPs support the causal links from Hypertension to AD/Dementia (496 SNPs) and T2D to AD/Dementia (478 SNPs). In contrast, the reverse direction pathways are supported by smaller SNP sets. The grey bars highlight key pleiotropic SNPs, such as rs429358, which is common to the reverse causal effects of AD/Dementia on both hypertension and T2D. (B) High-frequency SNP profiles for each causal direction, displaying the top 10 most recurrent SNPs. The frequency of each SNP is noted within the circle, and the diamond marker indicates the average frequency of the top 10. The analysis reveals a highly concentrated genetic signal for the T2D-to-AD/Dementia network, driven by exceptionally frequent SNPs like rs10830963 (frequency = 79) and rs2796441 (frequency = 74). In contrast, the forward signals from hypertension and obesity, as well as all reverse-direction signals, are more diffuse, characterized by SNPs with much lower recurrence frequencies. These findings highlight a strong, concentrated genetic basis for T2D-driven neurodegeneration and a more heterogeneous genetic architecture for other causal relationships.

Pleiotropic loci underscored shared mechanisms across networks. rs429358 was common to AD/Dementia effects on hypertension and T2D, and the reciprocal T2D-to-AD/Dementia network. rs6733839 linked AD/Dementia to hypertension and obesity. Five SNPs, including rs769449 and rs2972558, were shared in reverse effects on hypertension and T2D, while five others, including rs56094641 and rs6905288, connected forward effects of hypertension and T2D on dementia. Four SNPs, including rs10792832 and rs1532277, linked AD/Dementia to obesity and T2D, and five, including rs1558902 and rs12967878, connected obesity and T2D to AD/Dementia. These findings highlight a concentrated genetic signal for T2D-driven neurodegeneration and a more heterogeneous basis for reverse effects (Figure 3B; Supplementary Table S10).

Comparative performance of diagnostic models across multiple disease cohorts

To develop biologically informed diagnostic models, we identified gene sets representing key biological pathways implicated in the causal networks linking metabolic and neurocognitive disorder. This process involved multiple steps: first, we prioritized genetic instruments that were both part of robust, network-supported causal links and recurrent across multiple such links. Next, we mapped these SNPs to their putative effector genes using positional mapping. Finally, gene set enrichment analysis against the MSigDB C5 ontology database identified 121, 174, and 158 significantly enriched biological gene sets for the Hypertension-Dementia, Obesity-Dementia, and T2D-Dementia causal networks, respectively (Supplementary Table S11). To evaluate the diagnostic potential of these gene sets, we trained and tested ten machine learning models on six disease-specific transcriptomic datasets, assessing performance via the AUC. Model performance varied significantly across diseases and algorithmic architectures, revealing a clear hierarchy in the predictive power of gene expression signatures.

In neurodegenerative cohorts, particularly VaD and AD, models achieved exceptional discrimination. For VaD, the FT-Transformer led with an AUC of 0.908, followed closely by the Support Vector Machine (SVM) (AUC = 0.900) and ExtraTrees (AUC = 0.899). Similarly, in the AD cohort, the FT-Transformer excelled (AUC = 0.874), with SVM (AUC = 0.825) and ExtraTrees (AUC = 0.809) also demonstrating strong predictive utility. For Obesity and T2D, models showed moderate predictive power, with the FT-Transformer again outperforming others, achieving AUCs of 0.804 for Obesity and 0.662 for T2D. In contrast, gene signatures for general Dementia and Hypertension exhibited limited diagnostic potential, with the best models—FT-Transformer for Dementia (AUC = 0.594) and Logistic Regression for Hypertension (AUC = 0.598)—performing only marginally better than random chance.

Cross-model comparisons highlighted the consistent superiority of the deep learning FT-Transformer, which was the top performer in five of six datasets and highly competitive in the sixth. A second tier of effective models included SVM and tree-based ensemble methods (ExtraTrees and CatBoost), which provided robust predictions across most datasets. Simpler models, such as Logistic Regression and KNN, offered reliable baseline performance but rarely excelled. Notably, the TabNet model consistently underperformed, with AUCs approximating random chance (≈0.5) across all datasets (Figure 4A; Supplementary Table S12).

FIGURE 4

Predictive modeling and multi-omics integration identify key genes and pathways in metabolic and neurocognitive disorder. (A) Comparative performance profile of nine machine learning models across six disease datasets, evaluated by mean Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve (ROC AUC). The analysis demonstrates exceptional predictive accuracy for neurodegenerative cohorts, particularly Vascular Dementia (VaD) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). For VaD, the FT-Transformer model achieved a leading AUC of 0.908, closely followed by Support Vector Machine (SVM) (AUC = 0.900) and ExtraTrees (AUC = 0.899). Similarly, in the AD cohort, the FT-Transformer excelled with an AUC of 0.874. Models for metabolic disorders showed moderate to strong performance, with the FT-Transformer achieving an AUC of 0.804 for Obesity but a more modest 0.662 for T2D. In contrast, gene signatures for general Dementia (top AUC = 0.594) and Hypertension (top AUC = 0.598) showed limited diagnostic potential, performing only marginally above the random chance baseline (AUC = 0.5). The FT-Transformer consistently emerged as the superior model, while TabNet consistently underperformed across all datasets. (B) Upset plot analysis identifying shared high-performance biological pathways across disease combinations. This analysis reveals significant overlap in the predictive gene sets, pointing to common molecular mechanisms. The strongest overlap was identified between AD and VaD, with 205 shared pathways, led by “PROTEIN LOCALIZATION TO EXTRACELLULAR REGION” (performance score = 0.969) and “CARBOHYDRATE HOMEOSTASIS” (score = 0.958). A set of 19 pathways was shared among AD, Obesity, and VaD, with top performers including “POSITIVE REGULATION OF MULTICELLULAR ORGANISMAL PROCESS” and “LIPID METABOLIC PROCESS” (both score = 0.914). These findings underscore that shared vulnerabilities in protein localization, carbohydrate homeostasis, and lipid metabolism link these distinct age-related disorders. (C) Quantitative assessment and ranking of the top 30 elite genes based on a Holistic Gene Score. This composite score integrates performance-weighted importance from all models with a robustness factor (“Total Hits”) representing the frequency of a gene’s selection across all analyses. The results reveal two distinct gene archetypes: (1) high-impact “specialist” genes, such as SORL1 in AD (top-ranked with only 1 hit) and CPT1A in T2D (highly ranked with 2 hits), which derive their importance from potent, context-specific roles; and (2) broadly influential “generalist” genes, like APOE and APOC1 (each with 4 hits across AD and VaD), which gain prominence through consistent involvement across multiple disease contexts and predictive models. (D) Prioritization of the top 10 elite genes within each disease dataset using a Dataset-Specific Score. This score aggregates a gene’s weighted importance and appearance frequency within a single disease context. Lines connect identical genes across datasets, revealing key pleiotropic players. The analysis shows a striking convergence on lipid metabolism. APOE stands out as a highly pleiotropic gene, ranking first for VaD, Obesity, and Hypertension. APOC1 and CLU are core components of a shared neurodegenerative signature across AD, Dementia, and VaD. Disease-specific leaders, such as SORL1 in AD and CPT1A (fatty acid oxidation) in T2D, are also identified. This reinforces the central role of dysregulated lipid metabolism as a shared biological mechanism linking these metabolic and Neurocognitive Disorder.

Pairwise statistical comparisons confirmed significantly higher predictive accuracy in neurodegenerative cohorts (AD, VaD) compared to metabolic disorders (P < 0.0001). The SVM demonstrated robust and balanced performance, significantly outperforming ensemble models like RandomForest in accuracy for the AD cohort (P < 0.0001). The FT-Transformer exhibited a specialized advantage in class discrimination and sensitivity, achieving significantly higher AUC (P < 0.0001) and recall (P < 0.0001) compared to other models in the AD dataset (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2; Supplementary Table S13). These findings underscore the disease-specific diagnostic potential of transcriptomic signatures and the FT-Transformer’s consistent superiority as a classification framework.

Identification of predictive gene sets for disease classification

Our pathway-centric machine learning approach identified gene sets with robust predictive utility for classifying disease states, revealing both disease-specific and shared biological pathways. The diagnostic performance of these gene sets varied across diseases, reflecting distinct transcriptomic signatures underlying metabolic and neurodegenerative conditions.

For VaD, numerous gene sets exhibited exceptional discriminatory power, achieving AUC values exceeding 0.98 across all metrics. These high-performing gene sets, derived from causal links involving Hypertension, Obesity, and T2D, were functionally diverse. Key examples include CARBOHYDRATE HOMEOSTASIS (from the T2D→Dementia network), AMYLOID PRECURSOR PROTEIN METABOLIC PROCESS (Obesity→Dementia), and VASCULAR PROCESS IN CIRCULATORY SYSTEM (Hypertension→Dementia). These pathways, linked to glucose regulation, amyloid processing, and vascular function, respectively, underscore the strong transcriptomic signatures driving VaD classification.

For AD, gene sets consistently delivered high classification performance. The top-performing gene set, PROTEIN LOCALIZATION TO EXTRACELLULAR REGION (T2D→Dementia), achieved an AUC of 0.943 and an accuracy of 0.944, followed closely by POSITIVE REGULATION OF MULTICELLULAR ORGANISMAL PROCESS (Obesity→Dementia), with identical AUC and accuracy of 0.943 and 0.944. Other notable gene sets included CELL ACTIVATION (immune function), REGULATION OF TRANSPORT, and PHOSPHOLIPID TRANSPORT (cellular transport and metabolism), all with AUCs exceeding 0.91, highlighting the role of extracellular protein dynamics and immune regulation in AD diagnostics.

In metabolic cohorts, gene sets showed moderate predictive performance. For Obesity, the most predictive signatures, primarily from the reverse Dementia→Obesity network, were linked to lipid biology. The top gene set, LIPID METABOLIC PROCESS, achieved an AUC of 0.890 and an accuracy of 0.890, followed by LIPID LOCALIZATION (AUC = 0.916) and REGULATION OF KETONE METABOLIC PROCESS (AUC = 0.860). For Hypertension, REGULATION OF ANATOMICAL STRUCTURE SIZE (Hypertension→Dementia) was the most predictive, with an AUC of 0.863 and an accuracy of 0.856. For T2D, PROTEIN LOCALIZATION TO EXTRACELLULAR REGION (T2D→Dementia) yielded an AUC of 0.807 and an accuracy of 0.808. In the general Dementia cohort, where predictive signals were weaker, REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT (Hypertension→Dementia) performed best, with an AUC of 0.698 (Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S14).

Intersection analysis of high-performing gene sets revealed pleiotropic pathways with predictive utility across multiple diseases. REGULATION OF ANATOMICAL STRUCTURE SIZE was a shared signature across AD, Hypertension, and VaD (overall score = 0.901). A group of 19 gene sets was shared among AD, Obesity, and VaD, with top-ranked pathways including POSITIVE REGULATION OF MULTICELLULAR ORGANISMAL PROCESS and LIPID METABOLIC PROCESS (both with overall score = 0.914). The strongest overlap occurred between AD and VaD, with 205 shared predictive gene sets, led by PROTEIN LOCALIZATION TO EXTRACELLULAR REGION (overall score = 0.969) and CARBOHYDRATE HOMEOSTASIS (overall score = 0.958). These results highlight disease-specific transcriptomic signatures alongside shared pathways related to metabolism, protein localization, and organismal regulation, reflecting common biological vulnerabilities across these age-related disorders (Figure 4B).

Cross-disease prioritization of key genes reveals specialist and generalist signatures

To systematically prioritize the most impactful genes across metabolic and neurocognitive disorder, we developed a Holistic Gene Score. This score aggregates performance-weighted importance scores from all models and pathways, multiplied by a robustness factor derived from the logarithm of a gene’s total appearances (Total_Hits), which reflects the number of times a gene was identified as a predictive feature across all models, pathways, and disease datasets. This unified framework balances raw predictive power with consistency across diverse biological and analytical contexts. Analysis of contribution patterns revealed two gene archetypes: high-impact “specialist” genes and broadly influential “generalist” genes. Specialist genes, such as SORL1 in AD (Total_Hits = 1), achieved top rankings through exceptional influence in specific predictive pathways. Similarly, LDLR in general Dementia (Total_Hits = 3) and CPT1A in T2D (Total_Hits = 2) secured high ranks via limited but potent contributions. In contrast, generalist genes like APOE and APOC1, each identified in four contexts (Total_Hits = 4) for AD and VaD, and CAV1 across three contexts (AD, Obesity, VaD), gained prominence through consistent involvement across multiple models and pathways. This distinction highlights that a gene’s significance in a disease’s transcriptomic signature can arise from either context-specific potency or widespread influence across biological processes (Figure 4C).

For disease-specific prioritization, we calculated a Dataset-Specific Score for each gene by aggregating performance-weighted importance scores from all models and pathways, weighted by the logarithm of appearance frequency. This approach prioritized genes with consistent importance across high-performing models and frequent roles in distinct pathways. The top 10 genes per disease were selected based on this score, revealing both disease-specific and shared signatures, with a notable convergence on lipid metabolism and transport pathways. In AD, SORL1 topped the rankings, followed by lipid metabolism genes APOC1, LPL, ABCG1, and LIPA. For VaD, APOE and APOC1 led, underscoring lipid transport’s critical role. General Dementia signatures were dominated by LDLR and APOC1, followed by LDLRAP1 and APOA5. The consistent prominence of APOC1 and CLU across dementia-related cohorts highlights their role as core components of a shared neurodegenerative signature. In metabolic cohorts, Obesity was led by APOE, followed by cholesterol transport and lipid metabolism genes ABCA1, LPL, and CLU, overlapping significantly with dementia signatures. For Hypertension, APOE and SCARB1 topped the list, alongside inflammatory response gene TREM2. The T2D signature was distinct, with CPT1A (fatty acid oxidation) ranked highest, followed by cholesterol homeostasis genes (LDLR, ABCG1) and insulin secretion gene ABCC8. Cross-disease comparison identified APOE as a highly pleiotropic gene, ranking first for VaD, Obesity, and Hypertension, and in the top five for Dementia. Similarly, APOC1, CLU, and LPL consistently ranked among top-tier genes across both neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders, reinforcing lipid metabolism dysregulation as a shared biological mechanism linking these age-related diseases (Figure 4D). All gene importance rankings are presented in Supplementary Table S15.

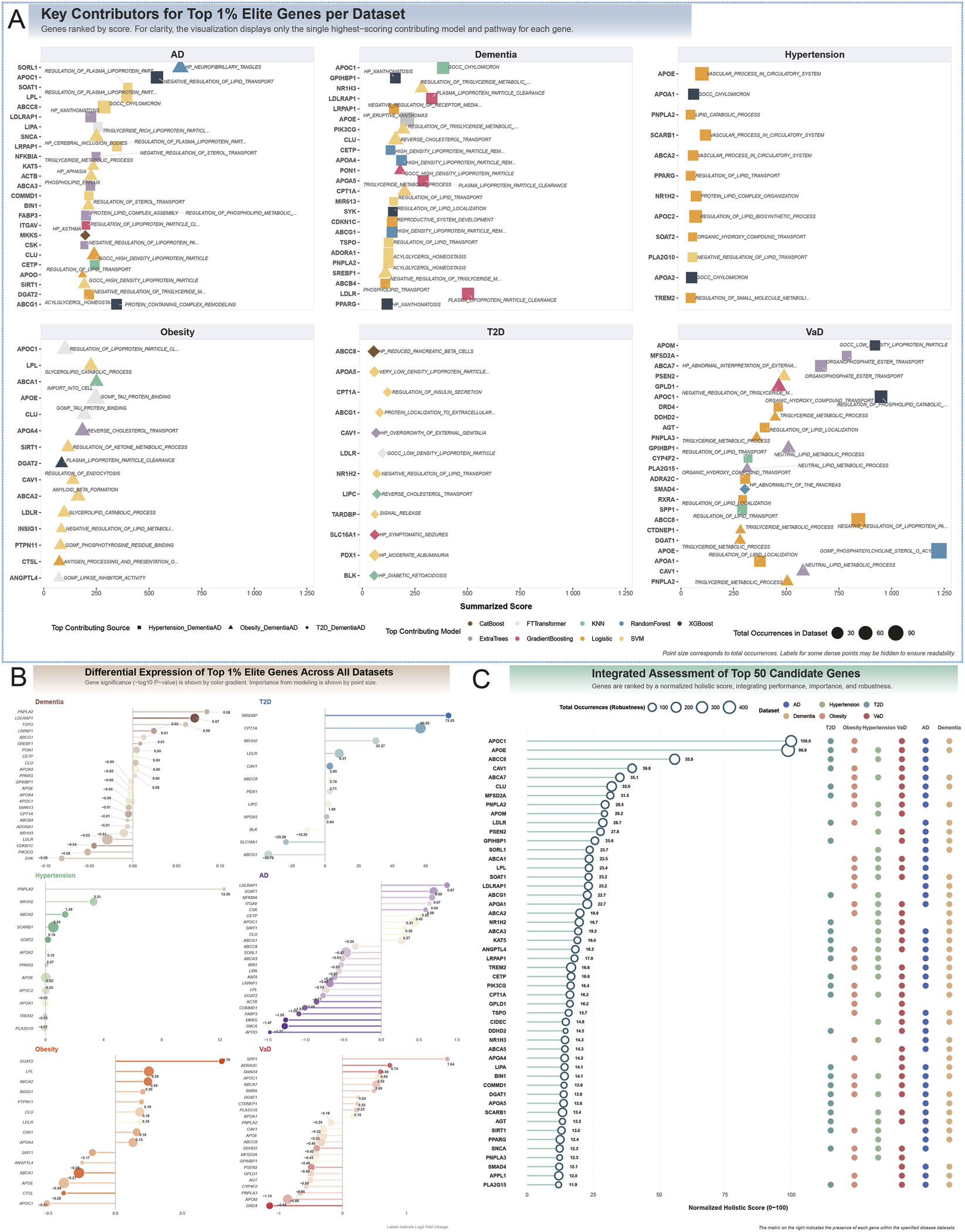

Lipid dysregulation as a central molecular axis and cross-disease pathway activation

Analysis of top-ranked genes and their pathway contributions revealed a molecular landscape consistently dominated by lipid dysregulation across all six diseases. Pathways related to lipid and lipoprotein metabolism were among the strongest contributors, exemplified by APOE and APOC1 in the VaD cohort (Summarized Scores = 1,225.30 and 949.91, respectively) and LDLR in the dementia cohort (Score = 502.57). Cross-disease pathway activation emerged in the obesity cohort, where the transcriptomic signature intersected with hallmark processes of neurodegeneration. While the top gene ABCA1 (Score = 250.50) was driven by the expected IMPORT INTO CELL pathway, the second-ranked gene APOE (Score = 246.74) derived its major contribution from the TAU PROTEIN BINDING pathway, a molecular feature central to AD. Conversely, the AD signature itself blended classic neurodegenerative and metabolic processes: SORL1 (Score = 648.53) was uniquely linked to NEUROFIBRILLARY TANGLES, whereas APOC1 (Score = 537.59) and SOAT1 (Score = 398.41) were primarily associated with NEGATIVE REGULATION OF LIPID TRANSPORT and REGULATION OF PLASMA LIPOPROTEIN PARTICLE ASSEMBLY.

A similar trend was observed in T2D, where the top gene CPT1A (Score = 120.19) was linked to REGULATION OF INSULIN SECRETION, yet other contributors, such as LDLR (Score = 96.22), implicated lipid clearance mechanisms also prominent in dementia. These findings suggest that disease-specific pathways can emerge as key transcriptomic drivers in unrelated conditions, underscoring complex molecular crosstalk between metabolic and neurodegenerative processes (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5