Abstract

Introduction:

Pompe disease (PD) is a rare inherited recessive autosomal disorder caused by pathogenic nucleotide variants within the gene GAA, encoding Acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA), the lysosomal enzyme catalyzing glycogen breakdown to glucose.

Methods:

We performed molecular screening in a cohort of 15,068 participants with suspected PD of a wide range of age from several regions of Russia. Two screenings had been undertaken from 2014 to 2025, and 2021 to 2025, respectively: 13,128 patients were screened using “two-tier one-gene” algorithm (measurement of GAA activity in dried blood spots followed by Sanger sequencing of the GAA) and 1940 patients were screened using Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)-based algorithm (NGS of the panel of genes linked to neuromuscular disorders, ANO5, CAPN3, DYSF, FKRP, SGCA, SGCB, SGCD, SGCG, TCAP, and GAA, followed by measurement of GAA activity when needed).

Results:

63 causative nucleotide variants in the GAA gene were detected, the most common being c.-32-13T>G (28 patients) followed by c.2662G>T (10 patients). 25 novel nucleotide variants in the GAA gene were described. Of 1,940 patients screened using an NGS-based algorithm, 138 patients (7.1%) were diagnosed with various muscular dystrophies, myopathies, or PD. The majority of these individuals had biallelic variants in the CAPN3 gene (30%), indicative of calpainopathy. Total 57 (0.47%) and 8 (0.41%) patients were diagnosed with PD as a result of “two-tier one-gene” or NGS-based algorithms, respectively.

Discussion:

Overall, our study is the first large-scale country-wide selective screening for PD in Russia based on sequencing and GAA activity measurement and providing the most comprehensive overview of genetics of PD in this study population.

1 Introduction

Pompe disease (PD, OMIM#232300), also known as Glycogen Storage Disease II (GSDII) or Acid Maltase deficiency, is a rare multisystem hereditary recessive autosomal disorder. It is caused by causative nucleotide variants (NVs) within the gene GAA (OMIM 606800) that is located on chromosome 17q25.2-q25.3 and encodes lysosomal enzyme Acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA, Enzyme Commission number 3.2.1.20, also known as Acid Maltase) (Reuser et al., 2019). Such NVs result in the absence or reduced enzymatic activity of GAA. The GAA is the only enzyme capable of catalyzing glycogen breakdown to glucose at acidic pH of lysosomal environment; thus, its inactivation or decreased activity causes aberrant accumulation of glycogen within lysosomes. In turn, it inevitably leads to lysosomal swelling and rupture, disturbed cytoplasmic glycogen metabolism, as well as changes in calcium homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, disruption of lysosome-dependent signaling pathways (such as mTORC1/AMPK) and subsequent pathologies of autophagy (summarized in (Sánchez-Porras et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024) and others). All of this results in a continuum of phenotypes and a broad range of PD manifestations.

The predicted genetic prevalence of PD in the general population varies by population. In particular, it is extremely low in Finland (1:1,056,444) and relatively high in Non-Finnish European (1:13,756) and East Asian population (1:12,125), whereas in other populations it is lower than in Non-Finnish Europeans but higher than in Finnish; namely, for Ashkenazi Jews it is estimated as 1:22,851, for African/African-American 1:26,560, for Latino/Admixed American 1:57,620, and for South Asian 1:93,087 (Park, 2021).

PD can affect people of any age. Traditionally, it is classified into two subtypes - Infantile Onset PD (IOPD) occurring at birth or within the first 12 months of life, also known as classic form of PD, and Late Onset PD (LOPD) occurring after the first 12 months of life. Additionally, depending on the time of onset, PD can be subdivided into infantile, late-infantile, childhood, juvenile, or adult PD. IOPD is characterized by severe muscle weakness, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and respiratory insufficiency. It is more detrimental compared to LOPD and if untreated usually results in death in the first 18 months of life. Common feature of LOPD is progressive dysfunction of skeletal muscle (“muscle weakness”) and subsequent respiratory failure. Classic IOPD is caused by complete functional deficiency of GAA defined as a less than ∼3 percent of activity, whereas levels of GAA activity in less severe late onset cases of PD are in the range of 3–30 percent of normal (van der Ploeg and Reuser, 2008). Some IOPD patients can also have an atypical (non-classic) phenotype, with manifestation by the end of the first year of life and symptoms less severe than in case of the classic one. At birth PD is usually asymptomatic. All of this complicates diagnostics and causes delays in providing appropriate therapy.

The gene GAA has been comprehensively characterized; hitherto, it is considered that it comprises 20 exons, non-coding exon 1 and coding exons 2–20. More than 1,000 sequence variants in the GAA gene can be found in the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed on 2 October 2025). Of them, more than 540 nucleotide variants have been reported so far as linked to PD (the Pompe disease GAA variant database, https://www.pompevariantdatabase.nl/pompe_mutations_list.php?orderby=aMut_ID1, accessed on 2 October 2025), and the database was extended by linking disease-associated variants to clinical severity (Niño et al., 2019).

The Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) - systematic intravenous infusion with a recombinant human GAA (rhGAA), that has been used in clinics for almost two decades allows to mitigate the GAA dysfunction, at least partially. Early ERT in IOPD may improve respiratory as well as some muscular functions and to some degree reverse cardiomyopathy, though with limited impact on skeletal muscles. There is a strong association of the ventilation-free survival and very early ERT initiation for IOPD patients (Kishnani et al., 2024).

Moreover, an immune response to rhGAA may render therapy ineffective. It’s been shown that ERT efficiency is determined at least in part by a so-called Cross-reactive immunologic material (CRIM) status (presence or absence of residual activity GAA). CRIM-negative infant PD patients (“GAA deficient”) usually have a worse clinical outcome on ERT compared to CRIM-positive infants, whose with dysfunctional or aberrant endogenous GAA, because of production of anti-rhGAA antibodies (anti-drug antibodies (ADA)) in CRIM-negative individuals (Gandaeva et al., 2022). However, it’s not always the case (Khallaf et al., 2012). Nevertheless, High-sustained rhGAA IgG antibody titers (HSAT) are observed in the majority of CRIM-negative and in some CRIM-positive individuals. In the case of CRIM-negative status, immunomodulatory therapy is recommended before or immediately after the initiation of ERT (Chen et al., 2024). CRIM-status can be determined by immunological approaches, such as Western blotting, but usually is accurately predicted based on the type of pathogenic nucleotide variants in the GAA gene (Bali et al., 2015).

In LOPD, an impact of ERT on skeletal muscle has been reported (Ripolone et al., 2018). It’s unknown whether ERT is needed or beneficial for asymptomatic individuals with LOPD (Bolano-Diaz and Diaz-Manera, 2022). However, some patients are less responsive to ERT and its efficiency varies in different tissues. Moreover, an immune response to rhGAA may render therapy ineffective. Hitherto, ERT is the only approved therapy of PD, apart from support therapies (physical therapy, artificial ventilation, etc). To overcome limitations of ERT discussed above, other curative approaches to PD are currently being developed, such as gene therapy introducing wild type GAA gene (comprehensively reviewed in (Unnisa et al., 2022)), pharmacological chaperone therapy (PCT) in case of dysfunctional GAA (comprehensively reviewed in (Borie-Guichot et al., 2021)), splicing modulation by antisense oligonucleotides (Aung-Htut et al., 2020) and others (Bellotti et al., 2020). For some of them, it’s of critical importance to determine disease-associated pathogenic nucleotide variants in the GAA gene of the patient.

Alarmingly, clinical presentation of LOPD is very broad and may overlap with other neuro-muscular conditions, leading to underdiagnoses of PD and delays in treatment. LOPD can be mistaken for Duchenne disease, Becker and limb-girdle types of muscular dystrophy, Myotonic dystrophy-2, Rigid spine syndrome, Myasthenia gravis, Spinal muscular atrophy, Polymyositis, Glycogen storage disease types IIIa, IV, V and VII, Danon disease, Mitochondrial myopathies, and Asymptomatic hyperCKemia (Barba-Romero et al., 2012). Even in the case of IOPD, which is characterized by rather uniform clinical features compared to LOPD, there is a spectrum of phenotypes and symptoms.

There is a significant diagnostic delay for PD compared to other more common conditions; for LOPD it can reach 12–480 (median 144) months, and reported delays in case of IOPD was 1.5–3 (median 2.5) months (Lagler et al., 2019). This is an unsatisfactory situation given the progressive nature of disease, severity of symptoms, and consequences of the therapy delay. An untreated PD is progressively debilitating and in the case of IOPD is life-threatening, thus it is of crucial importance to diagnose PD timely and precisely.

In some countries, PD is included in the recommended uniform screening program of heritable disorders in newborns and children (or other, equivalent programs) (Hale et al., 2020). In other regions, selective screening of high-risk population can be performed as an alternative to newborn screening (NS). Currently, no standard worldwide accepted protocol exists for the clinical molecular diagnosis of PD. The guidelines of European consensus for starting ERT recommend that the LOPD diagnosis is established if at least two disease-associated pathogenic nucleotide variants in the GAA gene are present and GAA deficiency is determined (van der Ploeg et al., 2017). This can be determined with the aid of a first-tier analysis via biochemical methods such as enzyme assays measuring GAA activity, usually using a dried blood spot (DBS) method (Goldstein et al., 2009), and GAA genotyping using various sequencing approaches, usually Sanger sequencing. Notably, some sequence variants within the GAA gene cause a decrease of the GAA enzyme activity, but do not cause PD - a pseudodeficiency phenomenon. The presence of pseudodeficiency variants might lead to false-positive results in enzyme assay-based tests for PD.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is a fast and relatively cost-effective high-throughput method that makes it possible to perform sequencing of multiple targets in a single reaction and test concurrently for several hereditary conditions. It’s a significant step forward compared to conventional long diagnostic journeys and “step-by-step” analysis confirming or ruling out certain diagnoses in a relatively time-consuming manner. Incorporation of NGS into clinical practice, subsequently, led to a paradigm shift in the algorithms of rare disease screening. A growing number of works report NGS as a preferable tool for PD diagnostics. Moreover, it’s been reported that deep NGS might correct diagnostic pitfalls of Sanger sequencing-based approach (Tsai et al., 2017).

Previously, NGS with targeted gene panels including GAA and other genes involved in neuromuscular diseases or glycogen storage disorders allowed to make a definite diagnosis of PD in several cohorts (Bevilacqua et al., 2020; Savarese et al., 2018; Lévesque et al., 2016). Moreover, it also allowed identifying novel sequence alterations within the GAA gene (King et al., 2023). The ongoing Lantern Project program applies EA of GAA as well as NGS, using focused multigene panel including GAA and other “neuromuscular” genes, to PD diagnostics (King et al., 2023), and as a result 140 study participants were diagnosed with PD during a period from 2018 till 2021. Importantly, several individuals from the cohort had sequence variants in both GAA and other genes from the panel. As we and others demonstrated recently, cases of coexistence of two or more rare hereditary diseases within individual patients (Burykina et al., 2025) advocate for comprehensive genetic testing. Indeed, having PD does not rule out the possibility of being affected by other diseases which have “neuromuscular” clinical presentations similar to PD.

Here, we present results of the country-wide selective screening in a cohort of 15,060 participants with suspected PD from several regions of Russia using two algorithms. First one is based on the measurement of GAA activity in dried blood spots (DBS) followed by Sanger sequencing of the GAA and second one uses Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the panel of genes linked to neuromuscular disorders, followed by measurement of GAA activity in patients with biallelic variant in GAA gene.

The current study is the largest selective molecular screening for PD in the Russia so far, providing the most comprehensive overview of genetics of PD in this study population.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study cohort and participants recruitment

The patients with suspected PD have been recruited to this single-center study governed by the Federal State Autonomous Institute National Medical Research Center for Children’s Health of the Russian Federation Ministry of Health on an ongoing basis starting from 2014 till current. The data from 2014 to 2025 are presented in this study. The participants were recruited from several geographically distant regions of the Russian Federation. Criteria for inclusion into the cohort were, in case of suspected IOPD - pronounced diffuse muscle hypotonia, myopathy, cardiomegaly, cardiomyopathy, macroglossia, aberrant heart rate; and in the case of suspected LOPD - diffuse muscle hypotonia, muscle weakness, presence of “Gowers’ sign” when standing up, difficulty walking, increased serum creatine kinase (CK) level. Other neuromuscular symptoms warranting recruitment into the cohort for NGS-based screening were 1) muscular weakness of the lower limbs, abdominal trunk muscles, back muscles 2) elevated creatine phosphokinase (200–2000 u/l) 3) elevated ALT/AST ratio. We screened 1,940 patients (795 females and 1,145 males) using an NGS-based algorithm. The median age at screening was 30.3 years, with ages ranging from 7 months to 72 years. For two-tier algorithm number of patients was 12,128 (5,700 females and 6,428 males). The median age at screening was 17.6 years, with ages ranging from 1 month to 88 years. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study or from their legal guardians, in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Medical Research Center for Children’s Health, Moscow, Russian Federation.

2.2 GAA activity measurement in DBS

The peripheral blood stains, ∼3 ul, were dried on a filter pad paper (Whatman carta-filter No. 903) and dried blood spots (DBS) were processed using standard procedure, as described previously elsewhere. Briefly, GAA activity was measured by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)-based method on “MaXis Impact” (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) with positive ionization in electrospray. Ion detection was carried out using flow-injection analysis with the Multiple Reaction Monitoring. The mixture of acetonitrile and water with the addition of formic acid was used as an eluent. The ion detection was in the range 100–550 m/z with an accuracy of determining masses of at least 5 ppm and solution of at least 20,000 (FWHM). The analysis time for one sample was 3 min. The data were analyzed using the built-in package software “Bruker Data Analysis 4.1”. In the case of low activity of the control enzyme in the sample, a new aliquot of the sample was analyzed. Enzyme activity was defined as the amount of product of the reaction, in units of μmol/L/h. In accordance with previously published recommendations (Savostyanov et al., 2021), the cutoff for GAA activity was chosen as 2.15 μmol/L/h.

2.3 DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from dried blood spots (DBS) with the MagPure Universal DNA Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) using the automated Auto-Pure 96 DNA isolation station (Allsheng, Hangzhou, China). DNA quality and concentration were measured either by spectrophotometry with the NanoPhotometer N60 (Implen Gmbh, Munich, Germany), or with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit and Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, United States).

2.4 Sanger sequencing

All primers used for GAA (NM_000152.5) sequencing were designed with “Beacon Designer 8.10”(PREMIER Biosoft International), and their specificity was confirmed using “Primer-BLAST.” Oligonucleotides were synthesized by JSC “Evrogen.” DNA amplification took place on Bio-Rad T100 (Bio-Rad, United States) and ProFlex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) thermocyclers. Sequencing reactions employed the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Capillary electrophoresis was conducted on ABI 3500XL and ABI 3500 genetic analyzers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The obtained sequences were compared against RefSeqGene references from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database.

2.5 MLPA analysis

Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) method was applied to detect deletions and duplications using the SALSA MLPA Probemix P453 (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Denaturation, hybridization, ligation and amplification were performed on Thermocyclers T100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) and ProFlex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), and capillary electrophoresis was performed on ABI 3500 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) genetic analyzer.

2.6 Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The target regions of the ANO5, CAPN3, DYSF, FKRP, GAA, SGCA, SGCB, SGCD, SGCG, and TCAP genes were analyzed. Hybridization probes for the NGS panel were created with the Hyper Design Tool (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, United States) to cover all coding and splice regions of the listed genes. Library preparation followed the KAPA HyperPlus Kit protocol, using a 15-min DNA fragmentation to yield ∼350 bp fragments. Target enrichment used KAPA HyperCap probes (Roche), and sequencing was performed on the MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, United States) with V2 chemistry (500 cycles, paired-end). Each run generated an average of 31.5 million reads, 88% above Q30, with 99% of target regions covered at least 15 times and a mean read depth of 100x.

2.7 Bioinformatic analysis

Bioinformatic analysis was carried out according to the guidelines of Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices (Broad Institute GATK, 2025). Briefly, raw reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (version 0.39) and sequence alignment was performed with Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (version 0.7.17) using GRCh38 genome assembly as a reference. Next, duplicate reads were marked using Picard tools, and base quality score recalibration (BQSR) was performed. Then, genetic variations (SNPs and indels) were identified with GATK HaplotypeCaller (version 4.1.2). Next, gene annotation was performed with an in-house script to annotate variations present in ClinVar, OMIM, and HGMD databases.

All sequence variants, obtained from Sanger sequencing and NGS with minor allele frequency of <1% according to the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) (available at: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org), were subjected to bioinformatics analysis in the program “Alamut Visual” (Interactive Biosoftware). In-silico tools SIFT, PolyPhen HDIV, PolyPhen HVAR, Mutation Taster, FATHMM, CADD13, DANN, M-CAP and REVEL, as well as Alamut with the built-in software modules were used for the prediction of the pathogenicity of the missense sequence variants. The guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) manual were used for the variants interpretation (Richards et al., 2015).

2.8 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the “Statistica 10.0” software package (StatSoft). For quantitative data use The Mann–Whitney p-test was used. The ROC method was used to determine the optimal cutting point corresponding to the maximum sensitivity and specificity of the method. The SPSS software and R were also used for statistical analysis. Calculation of reference intervals was performed following the previously published recommendations (Horn and Pesce, 2003).

3 Results

3.1 The study cohort and diagnostic algorithms

Here, we performed molecular screening in a cohort of 15,068 participants with suspected PD of a wide range of age from several regions of the Russian Federation. Two screenings had been undertaken from 2014 to 2025, and 2021 to 2025, respectively: 13,128 patients were screened using “two-tier one-gene” algorithm (measurement of GAA activity in DBS followed by Sanger sequencing of the GAA) and 1940 patients were screened using NGS-based algorithm followed by measurement of GAA activity to confirm diagnosis. The study design and screening outcomes are depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

The flowchart of screening algorithms and outcomes. VUS, variant of uncertain significancy, LP, likely pathogenic variant, P, pathogenic variant.

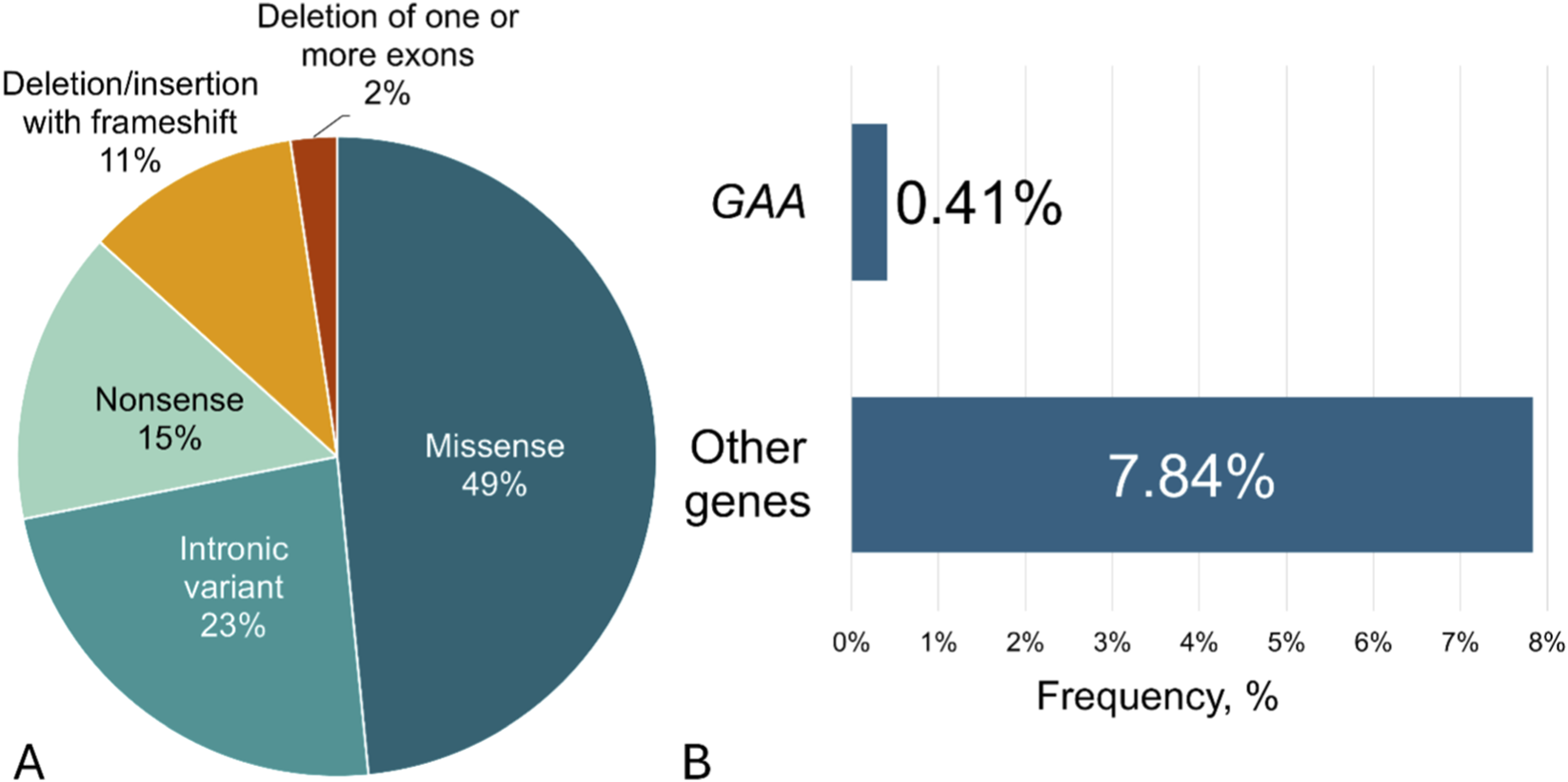

Several nucleotide variants within the GAA gene (NM_000152.5) and other genes from the NGS panel were identified in our study (Supplementary Table S1). Causative nucleotide variants in the GAA gene were found in 0.41% of cases, and in other genes from the NGS panel in 7.8% (Figure 2). Using “two-tier one-gene” algorithm, causative nucleotide variants in GAA gene were found in 0.47% of the cases.

FIGURE 2

(A) The total frequencies and type of nucleotide variants found in GAA gene using both algorithms in a cohort of 15,068 participants; (B) The frequencies of causal nucleotide variants found in GAA gene or other genes using NGS in a cohort of 1940 participants.

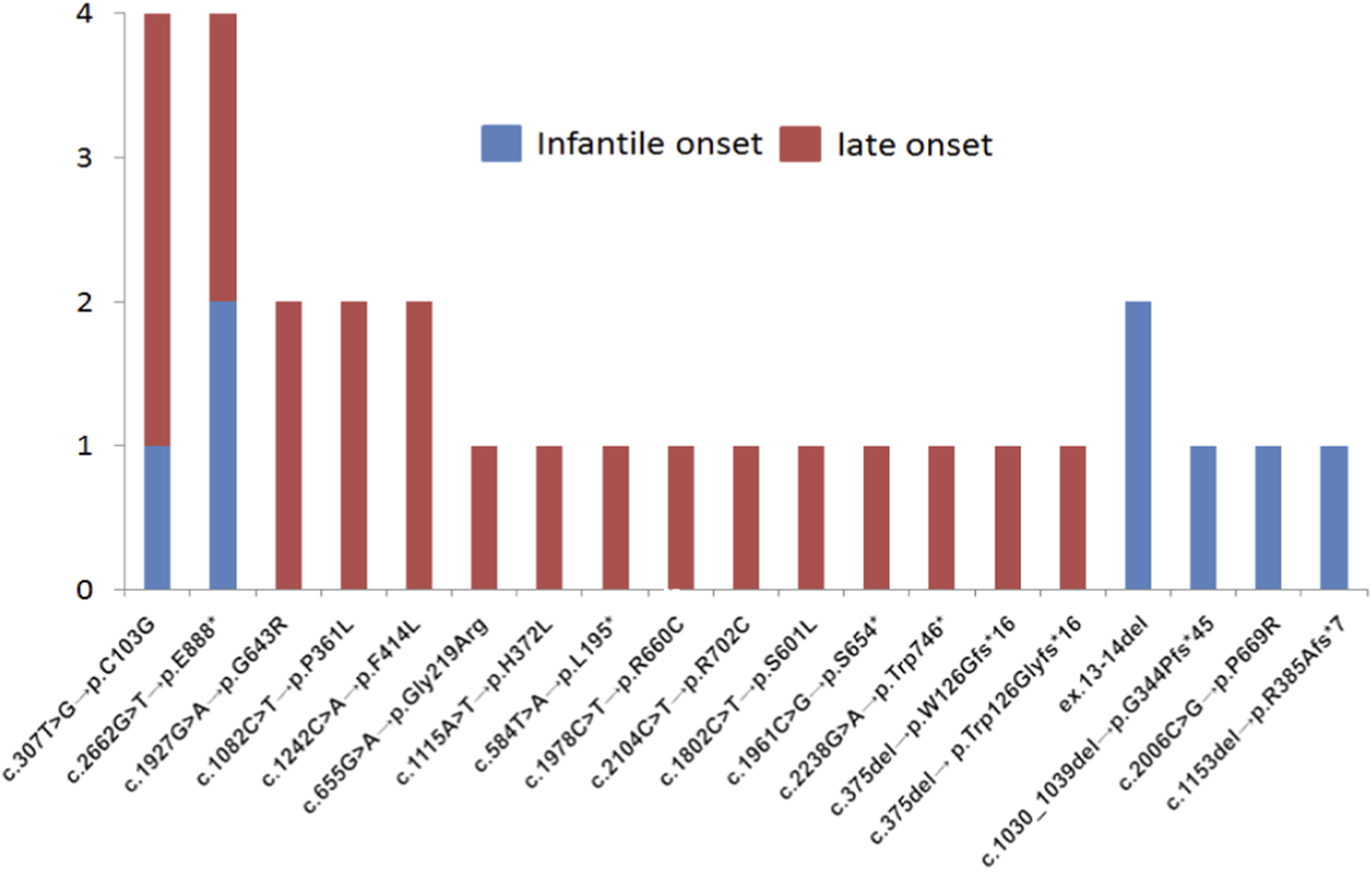

The frequencies and spectrum of the most common nucleotide variants found in the GAA gene using both algorithms in sub-cohorts of patients with IOPD and LOPD are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

The frequencies and spectrum of the most common sequence variants found in GAA gene using both algorithms in a cohort of 15,068 participants.

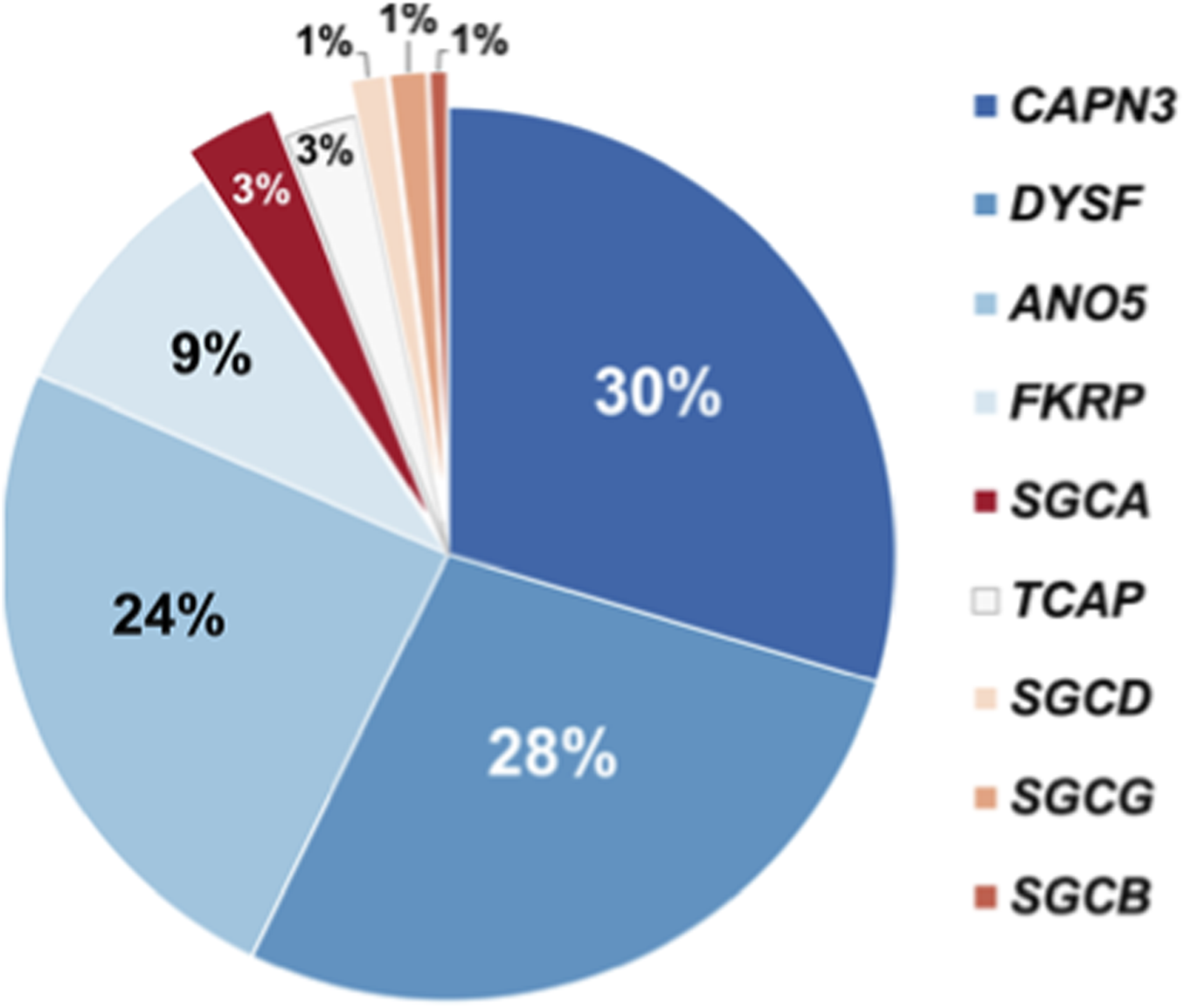

3.2 NGS-based screening

1,940 patients were screened using an NGS-based algorithm. As a result of screening total of 138 patients (7.1%) were diagnosed with various muscular dystrophies, myopathies, or PD. The majority of these individuals had biallelic variants in the CAPN3 gene (30%), indicative of calpainopathy, 28% of patients had biallelic variants in gene DYSF, indicative of dysferlinopathy, 24% of patients had biallelic variants in gene ANO5, indicative of muscular dystrophy, and in 9% of patients biallelic variants were found in gene FKRP (diagnosed with dystroglycanopathy). In 3% of cases biallelic variants were found in gene SGCA (diagnosed with α-sarcoglycanopathy). In 3% of patients biallelic variants were found in gene TCAP (diagnosied with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2G). In 1% of cases, genes SGCB, SGCD, SGCG had biallelic variants, indicative of beta-sarcoglycanopathy, delta-sarcoglycanopathy, and gamma-sarcoglycanopathy, correspondingly. The percentage of causal nucleotide variants identified by NGS across the panel of the genes is presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4

Pie-chart depicting percentage of causal nucleotide variants identified by NGS across the panel of the genes.

In 20 patients (1.4%) harboring biallelic variants in the GAA gene, GAA enzyme activity was evaluated by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS), resulting in the identification of 8 (0.41%) patients with PD. Additionally, at least one pseudodeficiency allele was detected in 190 patients (9.8%): rs1800307 (c.1726G>A, p. G576S) was found in 1.3% alleles, and rs1800309 (c.2065G>A, p. G689K) in 5.1% alleles, among others.

3.3 “Two-tier one-gene” screening

Total 13,128 patients were screened using “two-tier one-gene” algorithm. The HPLC-MS/MS identified 111 patients exhibiting enzyme activity values below the established cut-off (2.15 μmol/l/h), these patients underwent Sanger sequencing of the GAA gene. Among them, 54 patients were identified with biallelic VUS, LP, or P variants. Other 57 patients did not have biallelic variants in the GAA, and, within this group, 32 carried at least one pseudo-deficiency allele (rs1800307, c.1726G>A or rs1800309, c.2065G>A).

3.4 Genetic findings

In our cohort, all patients with c.-32-13T>G variant were compound heterozygous. The numbers and spectrum of nucleotide variants found in compound heterozygous state with c.-32-13T>G are shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5

The numbers and spectrum of nucleotide variants found in compound heterozygous state with c.-32-13T>G.

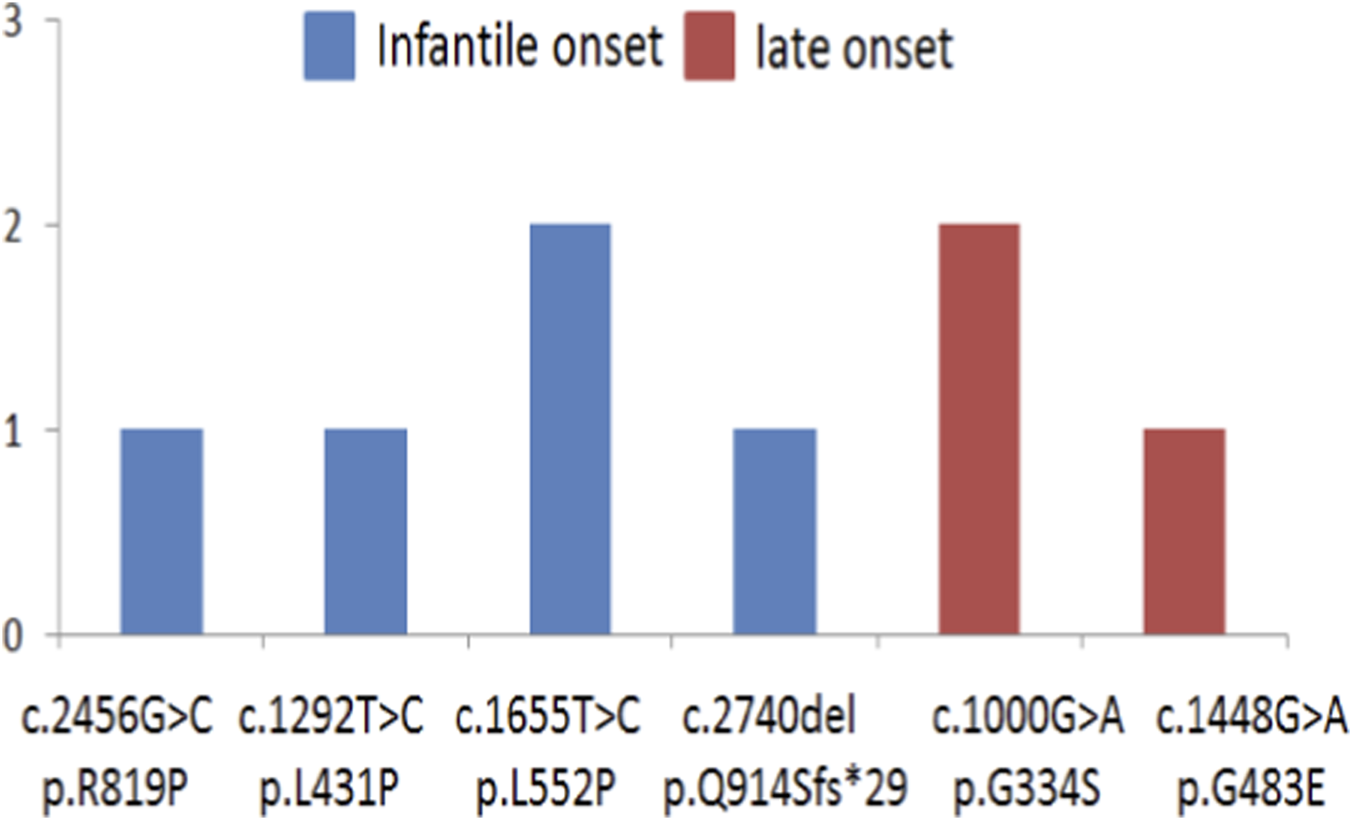

The majority of other causal nucleotide variants were also in compound heterozygous state, however several patients harbored such variants in homozygous state. In particular, 2 patients were homozygous for c.1000 G>A, p. G334S, 2 patients were homozygous for c.1655T>C, p. L552P. One was homozygous for c.2456G>C, p. R819P; one for c.1292T>C, p. L431P; one for c.1448G>A, p. G483E; one for c.2740del, p. Q914Sfs*29 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6

The numbers and spectrum of nucleotide variants found in homozygous state.

Total 25 novel nucleotide variants in GAA were described (Supplementary Table S2).

3.5 Genotype-phenotype correlations

Several differences in clinical signs were found for IOPD vs. LOPD patients (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Clinical sign | IOPD | LOPD | p-value (chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatomegaly | 11 | 4 | <0.001 |

| No hepatomegaly | 4 | 12 | |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 14 | 2 | 0.001 |

| No left ventricular hypertrophy | 3 | 19 | |

| Heart rhythm disturbances | 12 | 5 | 0.012 |

| No heart rhythm disturbances | 5 | 16 |

Clinical signs in patients with IOPD and LOPD.

The analysis also revealed that LOPD patients were statistically significantly more likely (by a factor of 2.96) to possess a genotype with one allele being c.-32-13T>G. Consequently, we elected to conduct a genotype-phenotype correlation study comparing two groups: patients with exclusively biallelic missense variants (Group 1) and with biallelic variants, one of which is c.-32-13T>G (Group 2). Following genotype-phenotype correlations were found (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Clinical sign | Group I a | Group II b | p-value (chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rhythm disturbances | 7 | 4 | 0.006 |

| No heart rhythm disturbances | 1 | 12 | |

| Motor development delay | 7 | 1 | <0.001 |

| No motor development delay | 2 | 17 | |

| Hepatomegaly | 6 | 3 | 0.012 |

| No hepatomegaly | 3 | 16 | |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 5 | 2 | 0.020 |

| No left ventricular hypertrophy | 4 | 17 |

Clinical signs in patients with different types of nucleotide variants in the GAA gene: genotype-phenotype correlation.

Patients only with biallelic missense variants.

Patients with biallelic variants, one of which is c.-32-13T>G.

Furthermore, logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the likelihood of clinical manifestations relative to the subtype of Pompe disease (IOPD or LOPD), the classification of nucleotide variants identified (Group1 or Group2), and enzyme activity levels. The results indicated a statistically significant increase in the probability (OR = 1.48) of delayed motor development in IOPD patients possessing biallelic missense variants (Group 1). No association was observed between clinical manifestations and enzyme activity.

4 Discussion

The rapid progress in the sequencing techniques in the last decade made it feasible to use NGS as a first-tier diagnostic tool in a clinical setting; however, Sanger sequencing still remains a gold standard in diagnostics. Commonly used approach to establish a PD diagnosis combines an initial enzyme assay (EA) measuring GAA activity (usually, in DBS) (Bodamer et al., 2017) and subsequent GAA genotyping (usually, via Sanger sequencing) in case of decreased enzymatic activity of GAA and suspicion of PD based on the overall clinical picture. Such EA is commonly performed using fluorometry-based analysis or tandem mass spectrometry, the latter allowing simultaneous measurement of activities of several enzymes. For example, as early as in 2005, a pilot newborns screening (NS) for PD was started at the National Taiwan University Hospital using a fluorometric EA. Of the total 206,088 screened infants, 6 were diagnosed with PD (Chien et al., 2009).

Notably, there are several limitations of EA assays and several issues to consider. The affinity GAA to glycogen is much higher compared to “artificial” substrate (4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, 4-MU), commonly used in EA (Wisselaar et al., 1993). There is a risk of getting false negative results. GAA activity overlaps with activity of other enzymes, namely, “leukocyte” neutral glucosidase II (GANAB), neutral α-glucosidase C (GANC), and maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM) which also use 4-MU as a substrate (Lukacs et al., 2020). GANAB and GANC do not have any significant activity in acid environments and do not interfere with assay, while MGAM is a main contributor to the false positive results in case of DBS sample analysis. Thus, usage of inhibitors of MGAM activity, maltose or acarbose, is required to minimize its interference with the fluorometric assay (Zhang et al., 2006). The activity of reference enzymes (RE) should be measured in parallel with GAA to monitor sample quality (Lukacs et al., 2020). The pre-analytical factors, such as specimen collection (an effect of drying conditions in case of DBS), its storage, transportation, and others, might affect the sensitivity of the test.

Here, we used HPLC-MS/MS method for GAA activity measurement which was previously optimized and comprehensively characterized by our team in a smaller scale pilot PD screening (Savostyanov et al., 2021).

Currently, PD is not included in any nation-wide NS, anywhere. However, in the US, it was included in the recommended uniform screening panel (RUSP) in February 2015. As an example of the implementation of such recommendation, in Pennsylvania detection rate of 1/16,095 (IOPD + LOPD) was reported based on results of the screening of 531,139 newborns performed between February 2016 and December 2019 (Ficicioglu et al., 2020). The study findings also included 15 newborns with one or two pseudodeficiency alleles and 2 false positive newborns. The screening was done using flow-injection tandem mass spectrometry (FIA/MS/MS) and full sequencing of GAA.

Our study is one of the few selective screenings for PD performed in the world. Results of selective screenings of patients with suspected PD, including adults with suspected LOPD, have been previously reported ((Meznaric et al., 2019; Sekulic et al., 2025) and others). As an example, one of the targeted NGS gene panel for differential diagnostics of PD included, alongside GAA, nine genes linked to diseases from a group of autosomal recessive limb–girdle muscular dystrophies (CAPN3, DYSF, SGCA, SGCB, SGCD, SGCG, FKRP, ANO5, TCAP) (Bevilacqua et al., 2024; Ficicioglu et al., 2020), the same as in our panel. Use of this panel in a 21-country multicentric analysis of 2,372 patients with progressive limb–girdle muscular weakness allowed diagnosing 86.2% and 13.8% of patients with LGMD and PD, correspondingly (Bevilacqua et al., 2024). Causative nucleotide variants (P, LP) were detected in 11% of patients compared to 8.5% in our cohort, perhaps due to population differences. Similarly to our study, the greatest numbers of causative nucleotide variants were detected in CAPN3 and DYSF genes (in 23.37% and 26.44% of cases, respectively) (Bevilacqua et al., 2024). The NGS panel used in Argentina on a cohort of 472 patients with muscle weakness included genes SGCA, SGCB, SGCG, SGCD, CAPN3, DYSF, TCAP, FKRP, ANO5, HNRPDL, GAA, CAV3. The most frequently causative nucleotide variants were detected in CAPN3 gene. The NGS of the panel was carried out for screening purposes in 0.4% of patients with definitive diagnosis of PD (Schiava et al., 2022).

In the case of PD, many causal nucleotide variants are “private”, i.e., found only in one family or in a very small population. Other PD-causing nucleotide variants are more common, and some of the common variants are more frequent in particular populations. For example, the “classic” nucleotide variant c.-32-13T>G (also known as IVS1) in the splicing site upstream of the 2nd exon of GAA is the most common among LOPD individuals in the European population (Niño et al., 2019). The allelic frequencies of this variant in PD patients range between 40% and 70% in some European populations (reviewed in (Peruzzo et al., 2019)). This variant is known to cause impaired splicing and production of three different “abnormal” splicing variants. It is considered that c.-32-13T>G affects overall splicing efficiency of the GAA pre-mRNA transcript, but some residual “normally spliced’ GAA mRNA is present in the cells with c.-32-13T>G, resulting in the delayed disease manifestation (reviewed in (Dardis et al., 2014)). It has been shown that c.510C>T variant is a modifier of the PD phenotype in compound heterozygous and homozygous c.-32-13T>G patients, as presence of c.510C>T decreases the levels of “normally spliced” GAA mRNA in the cell. Thus, compound heterozygous c.-32-13T>G patients with c.510C>T variant might have a childhood onset of PD (Bergsma et al., 2019). Other variants frequently found in compound heterozygous state with c.-32-13T>G are c.525del, c.2481 + 102_2646 + 31del; c.1927G>A (comprehensively reviewed in (Taverna et al., 2020)). Surprisingly, homozygosity of c.-32-13T>G is an unexpectedly rare event, so far being observed only in a few cases; moreover, c.-32-13T>G causal variant has never been observed in a homozygous state in classic IOPD, whereas in LOPD its homozygosity has been reported (Musumeci et al., 2015).

In our study it was also the most frequent nucleotide variant in the GAA gene, and, in line with previous publications, found exclusively in compound heterozygous state. Previously, it been shown that the combination of any splice site variant from the following, c.546G>C, c.1076–22T>G, c.2646 + 2 T>A, with c.−32–13T > G is more likely to be found in patients with LOPD (Viamonte et al., 2021).

In our study, variants most commonly found in compound heterozygous state with c.-32-13T>G were (in both IOPD and LOPD) c.307T>G, c.2662G>T, followed by c.1927G>A, c.1082C>T, c.3175del and (in IOPD) ex.13-14del (Figure 5). Finally, in our cohort variant c.-32-13T>G was more common in patients with LOPD (15.4%) compared to IOPD (6.2%), confirming previously reported findings from other populations.

The second most common causal variant in our cohort was c.2662G>T, p.E888*, detected in 3,8% of IOPD and 3,8% LOPD (Figure 5). Interestingly, the c.2662G>T is relatively common in Asian populations. For example, its allelic frequency in northern and southern Chinese patients with IOPD has been previously reported as 23.1% and 4.2%, respectively (Chen et al., 2017).

In our cohort variant c.1655T>C, p.L552P was relatively common among patients with IOPD (4,6%) but absent in LOPD. Such finding is rather unexpected given that it is a missense variant, and its presence does not result in a truncated protein. Notably, according to literature, this variant had previously been found in a patient with LOPD and is not exclusively IOPD-related (Joshi et al., 2008).

Some variants in GAA cause pseudodeficiency, such as a c.271G>A p. D91N (found in Caucasian populations) (Martiniuk et al., 1990), and c. [1726G>A; 2065G>A] (commonly found in Asian populations) (Tajima et al., 2007). Variant c.1726G>A, p. G576S in cis with c.2065G>A (so-called c. [1726A; 2065A] allele) is known to cause pseudodeficiency and is relatively common in Asian populations (Oda et al., 2011). Further, the c. [1726A; 2065A] homozygosity has been described in apparently healthy individuals in Japanese population (Kumamoto et al., 2009). It is also common among various Chinese populations (gnomAD 4.1: total 0.83%, East Asia 16.7%). Intriguingly, in our study, c.1726G>A was also found in 1.3% alleles, and c.2065G>A in 5.1% alleles (gnomAD 4.1: total 4.55%, East Asia 25.5%).

In light of the findings from the work by De Filippi et al. (De Filippi et al., 2010; De Filippi et al., 2014) [52–53], it’s plausible to suggest that the clinical phenotype of PD can be modulated by other genetic factors, such as sequence variants (including frequent polymorphisms) in the genes linked to other neuromuscular diseases and muscle tissue homeostasis. In such a scenario, of particular value might be the data obtained from NGS of the focused panel of “neuromuscular” genes, combined with the data from longitudinal study and allowing searching for possible additional modulators of PD phenotype.

Following genotype-phenotype correlations were found in our cohort: patients with biallelic missense variants compared to patients with biallelic variants, one of which is c.-32-13T>G, more often had heart rhythm disturbances (0,006), motor development delay (p < 0,001), hepatomegaly (0,012) and left ventricular hypertrophy (0,020). Notably, some missense variants found in our study and contributing to these genotype-phenotype correlations were also found in other studies in patients with IOPD. For example, position 643 is in the catalytic domain of GAA enzyme is close to its active site, and variant c.1927G>A, p. G643R, detected in our study, was previously reported as found in homozygous state IOPD patient from Tunisia (Alila-Fersi et al., 2020). Moreover, region including positions 638–645 is involved in the transport and maturation of the GAA protein (Li et al., 2023), significantly affecting its functions. In our cohort, missense variants c.1933G>A, p. D645N and c.1933G>C, p. D645H from this region were also present. Variant c.1933G>A, p. D645N was previously found in a homozygous state in IOPD patient from China (Kroos et al., 2012), indirectly confirming the impact of variants in this region on GAA function. Further, missense variants c.2456G>C p. R819P, c.1802C>T p. S601L, and c.1781G>A, p. R594H according to literature were predicted to cause severe phenotype of PD (Marotto et al., 2023). As for the frameshift and nonsense variants found in our study, in most cases they were found in the last exons of the gene, therefore only a relatively small part of the GAA protein close to the C-terminus was lost as a result.

In the current study, we also found that numbers of patients with such clinical signs as hepatomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy and heart rhythm disturbances were statistically significantly higher in patients with IOPD compared to LOPD (Table 2), which is consistent with the current views on the pathogenesis of PD.

Of note, additional assessments of metabolic alterations and biomarkers associated with PD can also being used to aid diagnostics. For example, LOPD is often associated with elevated levels of serum Creatine kinase (CK), although some patients with LOPD might have levels of CK in the normal range (Marotto et al., 2023). Furthermore, measurement of glycogen-derived tetrasaccharides (TGLC) secreted in urine, namely glucose tetrasaccharide (Glc4), either alone or in combination with its isomer maltotetraose (M4) (Heiner-Fokkema et al., 2020), can also be used as a complementary method for PD diagnostic and monitoring. Notably, Glc4 is not a PD-specific biomarker and can be used for a number of other glycogen storage diseases (GSDs), such as GSDIa and GSDIb (OMIM#232200, also known as von Gierke disease and G6P transport defect, correspondingly), GSDIIIa and GSDIIIb (OMIM#232400, also known as Cori disease and Forbes disease, correspondingly), GSDXI (OMIM#612933, also known as Lactate dehydrogenase deficiency) (Heiner-Fokkema et al., 2020). M4 has not been studied much due to its rapid degradation in urine (the issue that can be mitigated by adjusting specimen’s pH to ∼9.5), but recent work by Ren et al. has demonstrated its utility as a PD biomarker (perhaps also not exclusively PD-specific) (Ren et al., 2023). Obviously, other complementary metabolic biomarkers yet to be established in the clinic (for example, L-phenylalanine, N-acetyl-4-aminobutanal, N-acetyl-L-aspartic acid, and others) might increase diagnostic accuracy (de Moraes et al., 2023).

In our study we designed and applied two diagnostic algorithms for selective PD screening (namely, “two tier one gene” based on Sanger sequencing or NGS-based one) and presented its results. In our study, causative nucleotide variants in GAA gene were found in 0.47% and 0,41% of cases using “two-tier one-gene” algorithm and NGS-based approach. A molecular diagnostics laboratory should take into account a time/cost balance when choosing the preferable algorithm of screening for PD. Undoubtedly the NGS-based algorithm is faster and provides more data, thus shortening the patient’s “diagnostic journey”. In particular, it allows establishing differential diagnostics with a number of other disorders, as it has been demonstrated in our study where significant percent of patients from the cohort (7.1%) were diagnosed with various muscular dystrophies and myopathies. One or the other algorithm can be chosen depending on the capabilities of the diagnostic center and the aims of the screening.

Overall, the current study is the first one that provides a comprehensive picture of the genetic features of the PD (both IOPD and LOPD) in Russia.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1406018.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee of National Medical Research Center for Children’s Health, Moscow, Russian Federation. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

APu: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration. DC: Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. IZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review and editing. SN: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. EB: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. LuK: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. DA: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. MV: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. SV: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AlG: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. EG: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. ES: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AmG: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. OG: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. VD: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. OE: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. SK: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. ElN: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. EO: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. OT: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. EF: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. EvN: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. VC: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AY: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. LeK: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. NI: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. OR: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. YK: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. NP: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AAh: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AAl: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review and editing. NM: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review and editing. NS: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. LG: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. OZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. TP: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. AR: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review and editing. DD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review and editing. APa: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AF: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review and editing. KS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2025.1745925/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- ADA

anti-drug antibodies

- BQSR

base quality score recalibration

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CRIM

Cross-reacting immunologic material

- DBS

Dried blood spots

- EA

enzyme assay

- ERT

Enzyme replacement therapy

- FIA/MS/MS

Flow-injection tandem mass spectrometry

- GANAB

“leukocyte” neutral glucosidase II

- GANC

neutral α-glucosidase C

- GAA

Acid alpha-glucosidase

- Glc4

Glucose tetrasaccharide

- GSDII

Glycogen Storage Disease II

- GSDs

glycogen storage diseases

- HPLC-MS/MS

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)/Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- HSAT

High-sustained rhGAA IgG antibody titers

- IOPD

infantile-onset Pompe disease

- LOPD

Late Onset Pompe Disease

- LP

Likely pathogenic

- MGAM

Maltase-glucoamylase

- MLPA

Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NGS

Next-Generation Sequencing

- NS

newborn screening

- NVs

nucleotide variants

- PCT

pharmacological chaperone therapy

- P

pathogenic

- PD

Pompe disease

- RE

reference enzymes

- rhGAA

recombinant human GAA

- RUSP

recommended uniform screening panel

- TGLC

glycogen-derived tetrasaccharides

- VUS

variant of uncertain significance

References

1

Alila-Fersi O. Aloulou H. Werteni I. Mahfoudh N. Chabchoub I. Kammoun H. et al (2020). Mutations in GAA gene in Tunisian families with infantile onset Pompe disease: novel mutation and structural modeling investigations. J. Mol. Neurosci.70 (7), 1100–1109. 10.1007/s12031-020-01516-9

2

Aung-Htut M. T. Ham K. A. Tchan M. Johnsen R. Schnell F. J. Fletcher S. et al (2020). Splice-modulating antisense oligonucleotides restore some acid alpha-glucosidase activity in cells derived from patients with late-onset Pompe disease. Sci. Rep.10, 6702. 10.1038/s41598-020-63644-w3

3

Bali D. S. Goldstein J. L. Rehder C. Kazi Z. B. Berrier K. L. Dai J. et al (2015). Clinical laboratory experience of blood CRIM testing in infantile Pompe disease. Mol. Genetics Metabolism Reports5, 76–79. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.10.012

4

Barba-Romero M. A. Barrot E. Bautista-Lorite J. Gutierrez-Rivas E. Illa I. Jiménez L. M. et al (2012). Clinical guidelines for late-onset pompe disease. Rev. Neurol.54 (8), 497–507.

5

Bellotti A. S. Andreoli L. Ronchi D. Bresolin N. Comi G. P. Corti S. (2020). Molecular approaches for the treatment of pompe disease. Mol. Neurobiol.57, 1259–1280. 10.1007/s12035-019-01873-z

6

Bergsma A. J. van den Dorpel J. J. van den Hout H. J. van der Beek N. A. Schoser B. Toscano A. et al (2019). A genetic modifier of symptom onset in pompe disease. EBioMedicine43, 553–561. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.013

7

Bevilacqua J. A. Guecaimburu Ehuletche M. D. Perna A. Dubrovsky A. Franca M. C. Vargas S. et al (2020). The Latin American experience with a next generation sequencing genetic panel for recessive limb-girdle muscular weakness and pompe disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.15, 1. 10.1186/s13023-020-01488-y

8

Bevilacqua J. A. Al-Salti A. M. Al Madani A. Alves da Fonseca A. Durmus H. Chai J. et al (2024). Detection of gene variants associated with recessive limb-girdle muscular weakness and pompe disease in a global cohort of patients through the application of next-generation sequencing analysis. Front. Genet.15, 1477291. 10.3389/fgene.2024.1477291

9

Bodamer O. A. Scott C. R. Giugliani R. Pompe Disease Newborn Screening Working Group (2017). Newborn screening for pompe disease. Pediatrics140 (Suppl. ment_1), S4–S13. 10.1542/peds.2016-3886I

10

Bolano-Diaz C. Diaz-Manera J. (2022). Therapeutic options for the management of pompe disease: current challenges and clinical evidence in therapeutics and clinical risk management. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag.18, 1099–1115. 10.2147/TCRM.S356464

11

Borie-Guichot M. Tran M. L. Génisson Y. Ballereau S. Dehoux C. (2021). Pharmacological chaperone therapy for pompe disease. Molecules26 (23), 7223. 10.3390/molecules26237223

12

Broad Institute GATK (2025). Genome analysis toolkit. Available online at: https://gatk.broadinstitute.org (Accessed January 15, 2025).

13

Burykina Y. Chudakova D. Zharova O. Basargina E. Silnova I. Sdvigova N. et al (2025). A unique case of a child with two rare hereditary diseases: familial dilated cardiomyopathy and arterial calcification. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26, 5900. 10.3390/ijms26105900

14

Chen X. Liu T. Huang M. Wu J. Zhu J. Guo Y. et al (2017). Clinical and molecular characterization of infantile-onset pompe disease in mainland Chinese patients: identification of two common mutations. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers21 (6), 391–396. 10.1089/gtmb.2016.0295

15

Chen H. A. Hsu R. H. Fang C. Y. Desai A. K. Lee N. C. Hwu W. L. et al (2024). Optimizing treatment outcomes: immune tolerance induction in Pompe disease patients undergoing enzyme replacement therapy. Front. Immunol.15, 1336599. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1336599

16

Chien Y. H. Lee N. C. Thurberg B. L. Chiang S. C. Zhang X. K. Keutzer J. et al (2009). Pompe disease in infants: improving the prognosis by newborn screening and early treatment. Pediatrics124 (6), e1116–e1125. 10.1542/peds.2008-3667

17

Dardis A. Zanin I. Zampieri S. Stuani C. Pianta A. Romanello M. et al (2014). Functional characterization of the common c.-32-13T>G mutation of GAA gene: identification of potential therapeutic agents. Nucleic Acids Res.42 (2), 1291–1302. 10.1093/nar/gkt987

18

De Filippi P. Ravaglia S. Bembi B. Costa A. Moglia A. Piccolo G. et al (2010). The angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism modifies the clinical outcome in patients with pompe disease. Genet. Med.12 (4), 206–211. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181d2900e

19

De Filippi P. Saeidi K. Ravaglia S. Dardis A. Angelini C. Mongini T. et al (2014). Genotype-phenotype correlation in pompe disease, a step forward. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.9, 102. 10.1186/s13023-014-0102-z

20

de Moraes M. B. M. de Souza H. M. R. de Oliveira M. L. C. Peake R. W. A. Scalco F. B. Garrett R. (2023). Combined targeted and untargeted high-resolution mass spectrometry analyses to investigate metabolic alterations in pompe disease. Metabolomics19 (4), 29. 10.1007/s11306-023-01971-x

21

Ficicioglu C. Ahrens-Nicklas R. C. Barch J. Cuddapah S. R. DiBoscio B. S. DiPerna J. C. et al (2020). Newborn screening for pompe disease: pennsylvania experience. Int. J. Neonatal Screen.6 (4), 89. 10.3390/ijns6040089

22

Gandaeva L. A. Basargina E. N. Zharova O. P. Kondakova O. B. Rozhkova A. B. Pushkov A. A. et al (2022). A modern view on the management of patients with infantile pompe disease. Pharmateca29 (1), 51–61. 10.18565/pharmateca.2022.1.51-61

23

Goldstein J. L. Young S. P. Changela M. Dickerson G. H. Zhang H. Dai J. et al (2009). Screening for pompe disease using a rapid dried blood spot method: experience of a clinical diagnostic laboratory. Muscle and Nerve40 (1), 32–36. 10.1002/mus.21337

24

Hale K. Kellar-Guenther Y. McKasson S. Singh S. Ojodu J. (2020). Expanding newborn screening for pompe disease in the United States: the NewSTEPs new disorders implementation project, a resource for new disorder implementation. Int. J. Neonatal Screen.6 (2), 48. 10.3390/ijns6020048

25

Heiner-Fokkema M. R. van der Krogt J. de Boer F. Fokkert-Wilts M. J. Maatman R. G. Hoogeveen I. J. et al (2020). The multiple faces of urinary glucose tetrasaccharide as biomarker for patients with hepatic glycogen storage diseases. Genet. Med.22 (11), 1915–1916. 10.1038/s41436-020-0895-4

26

Horn P. S. Pesce A. J. (2003). Reference intervals: an update. Clin. Chim. Acta334 (1-2), 5–23. 10.1016/S0009-8981(03)00133-5

27

Joshi P. R. Gläser D. Schmidt S. Vorgerd M. Winterholler M. Eger K. et al (2008). Molecular diagnosis of German patients with late-onset glycogen storage disease type II. J. Inherit. Metabolic Dis.31, 261–265. 10.1007/s10545-008-0831-4

28

Khallaf H. H. A. Propst J. Geffrard S. Botha E. Pervaiz M. A. (2012). CRIM-negative Pompe disease patients with satisfactory clinical outcomes on enzyme replacement therapy. JIMD Reports–Case Res. Rep.2012/6, 133–137. 10.1007/8904_2012_192

29

King L. S. Pan Y. Nallamilli B. R. Hegde M. Jagannathan L. Ramachander V. et al (2023). Pompe disease ascertained through the Lantern Project, 2018–2021: next-generation sequencing and enzymatic testing to overcome obstacles to diagnosis. Mol. Genet. Metabolism139 (1), 107565. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2023.107565

30

Kishnani P. Stockton D. Hahn A. Llerena J. Broomfield A. Batista J. et al (2024). Early treatment with Alglucosidase Alfa is associated with improved survival in patients with infantile-onset pompe disease: data from pompe registry. Genet. Med. Open2. 10.1038/s44598-024-00029-7

31

Kroos M. Hoogeveen‐Westerveld M. Michelakakis H. Pomponio R. Van der Ploeg A. Halley D. et al (2012). Update of the pompe disease mutation database with 60 novel GAA sequence variants and additional studies on the functional effect of 34 previously reported variants. Hum. Mutat.33 (8), 1161–1165. 10.1002/humu.22104

32

Kumamoto S. Katafuchi T. Nakamura K. Endo F. Oda E. Okuyama T. et al (2009). High frequency of acid alpha-glucosidase pseudodeficiency complicates newborn screening for glycogen storage disease type II in the Japanese population. Mol. Genet. Metabolism97, 190–195. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.03.005

33

Lagler F. B. Moder A. Rohrbach M. Hennermann J. Mengel E. Gökce S. et al (2019). Extent, impact, and predictors of diagnostic delay in Pompe disease: a combined survey approach to unveil the diagnostic odyssey. JIMD Rep.49 (1), 89–95. 10.1002/jmd2.12074

34

Lévesque S. Auray-Blais C. Gravel E. Boutin M. Dempsey-Nunez L. Jacques P. E. et al (2016). Diagnosis of late-onset pompe disease and other muscle disorders by next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.11, 1. 10.1186/s13023-016-0439-2

35

Li J. Shi X. Wang B. Hsi D. H. Zhu X. Ta S. et al (2023). Pompe disease in China: clinical and molecular characteristics. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10, 1261172. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1261172

36

Lukacs Z. Oliva P. Nieves Cobos P. Scott J. Mechtler T. P. Kasper D. C. (2020). At-Risk testing for pompe disease using dried blood spots: lessons learned for newborn screening. Int. J. Neonatal Screen6 (4), 96. 10.3390/ijns6040096

37

Marotto D. Moschetti M. Lo Curto A. Spezzigu A. M. Giacomarra M. Marsana E. M. et al (2023). Late-onset pompe disease with normal creatine kinase levels: the importance of rheumatological suspicion. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (21), 15924. 10.3390/ijms242115924

38

Martiniuk F. Bodkin M. Tzall S. Hirschhorn R. (1990). Identification of the base-pair substitution responsible for a human acid alpha glucosidase allele with lower “Affinity” for glycogen (GAA 2) and transient gene expression in deficient cells. Am. J. Hum. Genet.47, 440–445. 10.1016/S0002-9297(16)38645-X

39

Meznaric M. Fumic K. Leonardis L. (2019). Selective screening of late-onset pompe disease (LOPD) in patients with non-diagnostic muscle biopsies. J. Clin. Pathology72 (7), 468–472. 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205472

40

Musumeci O. Thieme A. Claeys K. G. Wenninger S. Kley R. A. Kuhn M. et al (2015). Homozygosity for the common GAA gene splice site mutation c.-32-13T>G in pompe disease is associated with the classical adult phenotypical spectrum. Neuromuscul. Disord.25 (9), 719–724. 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.06.004

41

Niño M. Y. In’t Groen S. L. Bergsma A. J. van der Beek N. A. Kroos M. Hoogeveen‐Westerveld M. et al (2019). Extension of the Pompe mutation database by linking disease-associated variants to clinical severity. Hum. Mutat.40 (11), 1954–1967. 10.1002/humu.23881

42

Oda E. Tanaka T. Migita O. Kosuga M. Fukushi M. Okumiya T. et al (2011). Newborn screening for pompe disease in Japan. Mol. Genet. Metabolism104, 560–565. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.09.002

43

Park K. S. (2021). Carrier frequency and predicted genetic prevalence of pompe disease based on a general population database. Mol. Genet. Metabolism Rep.27, 100734. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2021.100734

44

Peruzzo P. Pavan E. Dardis A. (2019). Molecular genetics of pompe disease: a comprehensive overview. Ann. Transl. Med.7 (13), 278. 10.21037/atm.2019.05.12

45

Ren J. Ma Y. Ma M. Ding J. Jiang J. Zheng X. et al (2023). Development of a rapid simultaneous assay of two urinary tetrasaccharide metabolites using differential ion mobility and tandem mass spectrometry and its application to patients with glycogen storage disease (type Ib and II). Anal. Bioanal. Chem.415 (27), 6863–6871. 10.1007/s00216-023-04756-4

46

Reuser A. J. J. Hirschhorn R. Kroos M. A. (2019). “Pompe disease: Glycogen storage disease type II: acid α-Glucosidase (acid maltase) deficiency,” in The online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. Editors ValleD.AntonarakisS.BallabioA.BeaudetA. L.MitchellG. A. (New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill).

47

Richards S. Aziz N. Bale S. Bick D. Das S. Gastier-Foster J. et al (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med.17 (5), 405–423. 10.1038/gim.2015.30

48

Ripolone M. Violano R. Ronchi D. Mondello S. Nascimbeni A. Colombo I. et al (2018). Effects of short-to-long term enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) on skeletal muscle tissue in late onset pompe disease (LOPD). Neuropathology Appl. Neurobiol.44 (5), 449–462. 10.1111/nan.12466

49

Sánchez-Porras V. Guevara-Morales J. M. Echeverri-Peña O. Y. (2023). From acid alpha-glucosidase deficiency to autophagy: understanding the bases of POMPE disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (15), 12481. 10.3390/ijms241512481

50

Savarese M. Torella A. Musumeci O. Angelini C. Astrea G. Bello L. et al (2018). Targeted gene panel screening is an effective tool to identify undiagnosed late onset pompe disease. Neuromuscul. Disord.28 (7), 586–591. 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.04.006

51

Savostyanov K. V. Pushkov A. A. Basargina E. N. Kuzenkova L. M. Mazanova N. N. Gandaeva L. A. et al (2021). Selective screening and molecular characteristics of Russian patients with pompe disease. L.O. badalyan neurological. Journal2 (4), 203–215. 10.46563/2686-8997-2021-2-4-203-215

52

Schiava M. Marchesoni C. De Rosa M. G. Estrada N. Cejas L. L. Pardal A. et al (2022). Genetic characterization of limb girdle muscular dystrophies and pompe disease in a large Argentine cohort. Neurol. Perspect.2 (3), 123–133. 10.1055/a-1868-8643

53

Sekulic A. Viric V. Todorovic T. Pesovic J. Brankovic M. Andrejic N. et al (2025). Screening for pompe disease in Serbian patients with limb-girdle muscle weakness. Clin. Neurology Neurosurg.7, 108950. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2025.108950

54

Tajima Y. Matsuzawa F. Aikawa S. I. Okumiya T. Yoshimizu M. Tsukimura T. et al (2007). Structural and biochemical studies on pompe disease and a pseudodeficiency of acid α-Glucosidase. J. Hum. Genet.52 (11), 898–906. 10.1007/s10038-007-0193-9

55

Taverna S. Cammarata G. Colomba P. Sciarrino S. Zizzo C. Francofonte D. et al (2020). Pompe disease: pathogenesis, molecular genetics and diagnosis. Aging (Albany NY)12 (15), 15856–15874. 10.18632/aging.103794

56

Tsai A. C. Hung Y. W. Harding C. Koeller D. M. Wang J. Wong L. C. (2017). Next generation deep sequencing corrects diagnostic pitfalls of traditional molecular approach in a patient with prenatal onset of pompe disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A173 (9), 2500–2504. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38326

57

Unnisa Z. Yoon J. K. Schindler J. W. Mason C. van Til N. P. (2022). Gene therapy developments for pompe disease. Biomedicines10 (2), 302. 10.3390/biomedicines10020302

58

van der Ploeg A. T. Reuser A. J. (2008). Pompe’s disease. Lancet372 (9646), 1342–1353. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61582-3

59

van der Ploeg A. T. Kruijshaar M. E. Toscano A. Laforêt P. Angelini C. Lachmann R. H. et al (2017). European consensus for starting and stopping enzyme replacement therapy in adult patients with pompe disease: a 10‐Year experience. Eur. J. Neurology24 (6), 768-e31. 10.1111/ene.13314

60

Viamonte M. A. Filipp S. L. Zaidi Z. Gurka M. J. Byrne B. J. Kang P. B. (2021). Phenotypic implications of pathogenic variant types in pompe disease. J. Hum. Genet.66 (11), 1089–1099. 10.1038/s10038-021-00989-8

61

Wisselaar H. A. Kroos M. A. Hermans M. M. van Beeumen J. Reuser A. J. (1993). Structural and functional changes of lysosomal acid alpha-glucosidase during intracellular transport and maturation. J. Biol. Chem.268, 2223–2231. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47826-2

62

Zhang H. Kallwass H. Young S. P. Carr C. Dai J. Kishnani P. S. et al (2006). Comparison of maltose and acarbose as inhibitors of maltase-glucoamylase activity in assaying acid alpha-glucosidase activity in dried blood spots for the diagnosis of infantile pompe disease. Genet. Med.8, 302–306. 10.1097/01.gim.0000221681.98652.ff

63

Zhang M. Niu J. Xu M. Wei E. Liu P. Sheng G. (2024). Interplay between mitochondrial dysfunction and lysosomal storage: challenges in genetic metabolic muscle diseases with a focus on infantile onset pompe disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.11, 1367108. 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1367108

Summary

Keywords

gene GAA, genetic screening, infantile-onset pompe disease (IOPD), late-onset pompe disease (LOPD), next-generation sequencing, NGS, pompe disease, rare hereditary diseases

Citation

Pushkov A, Chudakova D, Zhanin I, Nikitin S, Basargina E, Kuzenkova L, Andreeva D, Vasil’eva M, Vasichkin S, Gabitova A, Gaisina E, Saifullina E, Gamzatova A, Gilvanova O, Dudin V, Ergina O, Kurbatov S, Noskova E, Osipova E, Tihonova O, Fedotova E, Nuzhny E, Chernikova V, Yamshchikova A, Kyzina L, Irinina N, Rohlenko O, Kutkova Y, Popkova N, Ahunova A, Alexeeva A, Mazanova N, Sdvigova N, Gandaeva L, Zharova O, Podkletnova T, Sukhozhenko A, Rusakova A, Demianov D, Pakhomov A, Fisenko A and Savostyanov K (2026) Pompe disease: a country-wide molecular screening in a cohort of 15,068 study participants. Front. Mol. Biosci. 12:1745925. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2025.1745925

Received

13 November 2025

Revised

19 December 2025

Accepted

23 December 2025

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Maurizio Renna, University of Naples Federico II, Italy

Reviewed by

Timur R. Samatov, Evotec, Germany

Chenjing Sun, Sixth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Pushkov, Chudakova, Zhanin, Nikitin, Basargina, Kuzenkova, Andreeva, Vasil’eva, Vasichkin, Gabitova, Gaisina, Saifullina, Gamzatova, Gilvanova, Dudin, Ergina, Kurbatov, Noskova, Osipova, Tihonova, Fedotova, Nuzhny, Chernikova, Yamshchikova, Kyzina, Irinina, Rohlenko, Kutkova, Popkova, Ahunova, Alexeeva, Mazanova, Sdvigova, Gandaeva, Zharova, Podkletnova, Sukhozhenko, Rusakova, Demianov, Pakhomov, Fisenko and Savostyanov.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kirill Savostyanov, 7443333@gmail.com; Daria Chudakova, chudakova.da@nczd.ru

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.