Abstract

Although SCN1A variants result in a wide range of phenotypes, genotype-phenotype associations are not well established. We aimed to explore the phenotypic characteristics of SCN1A associated seizure diseases and establish genotype-phenotype correlations. We retrospectively analyzed clinical data and results of genetic testing in 41 patients carrying SCN1A variants. Patients were divided into two groups based on their clinical manifestations: the Dravet Syndrome (DS) and non-DS groups. In the DS group, the age of seizure onset was significantly earlier and ranged from 3 to 11 months, with a median age of 6 months, than in the non-DS group, where it ranged from 7 months to 2 years, with a median age of 10 and a half months. In DS group, onset of seizures in 11 patients was febrile, in seven was afebrile, in two was febrile/afebrile and one patient developed fever post seizure. In the non-DS group, onset in all patients was febrile. While in the DS group, three patients had unilateral clonic seizures at onset, and the rest had generalized or secondary generalized seizures at onset, while in the non-DS group, all patients had generalized or secondary generalized seizures without unilateral clonic seizures. The duration of seizure in the DS group was significantly longer and ranged from 2 to 70 min (median, 20 min), than in the non-DS group where it ranged from 1 to 30 min (median, 5 min). Thirty-one patients harbored de novo variants, and nine patients had inherited variants. Localization of missense variants in the voltage sensor region (S4) or pore-forming region (S5–S6) was seen in seven of the 11 patients in the DS group and seven of the 17 patients in the non-DS group. The phenotypes of SCN1A-related seizure disease were diverse and spread over a continuous spectrum from mild to severe. The phenotypes demonstrate commonalities and individualistic differences and are not solely determined by variant location or type, but also due to functional changes, genetic modifiers as well as other known and unknown factors.

Introduction

Since the first discovery of SCN1A gene associated with epilepsy in 2000 (Escayg et al., 2000), SCN1A has remained the most common and important epilepsy pathogenic gene. The gene is located on chromosome 2q24.3 and encodes the alpha 1 subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.1, a 2,000 amino acid protein and exhibits dominant interneuron-specific expression. SCN1A variants lead to dysfunction of the sodium channel which initiates and propagates neuronal action potentials, thereby causing epilepsy (Stafstrom, 2009). It has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with incomplete penetrance. Its pathogenic variants cause a wide range of phenotypes, ranging from the mildest simple febrile seizures (FS) to severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI), or early onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (Scheffer and Nabbout, 2019). Although the various phenotypes have distinct characteristics, they often have similar presentations at onset, such as early stage febrile convulsions, thereby making it difficult to predict phenotype development. To date, 2,127 pathogenic variants of the SCN1A have been reported and documented in the Human Gene Mutation Database. However, genotype-phenotype correlation of these seizure disorders is still unclear. This study retrospectively documented the clinical phenotype and genotype data of 41 patients with SCN1A variants, to explore genotype-phenotypic associations. The results can be used to define the phenotypic spectrum as well as provide a scientific basis for precision-based clinical treatment and genetic counseling for SCN1A-related seizure disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample Collection

From March 2015 to June 2021, a total of 41 patients with SCN1A variants who presented with convulsions at the Department of Neurology, Beijing Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University, China were recruited. The clinical data of these patients and their family members, including sex, age, age of seizure onset, clinical manifestations, seizure evolution, birth history, growth and development history, family history, cranial imaging, electroencephalogram (EEG), and other laboratory examinations, as well as clinical diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up were collected and summarized.

Based on the clinical manifestations, the 41 patients were divided into two groups. In the first, the Dravet syndrome (DS) group, included patients with severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI) and severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy borderline (SMEB), that also covered intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures (ICEGTC) (Fujiwara et al., 2003). The second group contained patients of non-Dravet syndrome (non-DS), including genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), febrile seizures (FS), febrile seizures plus (FS+), and epilepsy not classified as a specific epileptic syndrome. The diagnosis of the patients was made after meeting the specific diagnostic criteria of febrile seizures, epilepsy, and epilepsy syndrome (Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1989).

This study was a retrospective cohort study. The research scheme was approved by the medical ethics committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University.

Diagnostic Criteria

Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI) typically presents with prolonged febrile and afebrile seizures in infants without impaired physical or neurologic development prior to onset. Myoclonic, focal, atypical absence, and atonic seizures present between the ages of 1 and 4 years, This form of epilepsy is usually intractable, and affected children develop epileptic encephalopathy with cognitive, behavioral, and motor impairment. The patient often has a family history of epilepsy or febrile seizures. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy borderline (SMEB) refers to patients who lack several of the key features of SMEI, such as myoclonic seizure or generalized spike-wave discharges in EEG, or exhibit cognitive function impairment to a lesser degree (Scheffer et al., 2009; Guerrini and Oguni, 2011; Wirrell et al., 2017).

Febrile seizures (FS) refer to generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) with fever that occur between 6 months and 6 years. Febrile seizures that occur outside the normal age limits of classical FS (6 months to 6 years), or afebrile generalized tonic-clonic seizures occur as well as febrile convulsive seizures are referred to as febrile seizures plus (FS+). Genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is characterized by a wide phenotypic spectrum, including febrile seizures (FS), FS plus (FS+), and FS along with other minor seizure types, although it is considered a familial epilepsy syndrome, but it does not always occur in a familial context, patients with GEFS+ phenotypes may have de novo variants (Myers et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0. Measurement data were expressed as the median while the enumeration data were expressed as the number of cases. For measurement data that presented a normal distribution, a t-test was used, else the Mann-Whitney was used for analysis. Enumeration data were analyzed using the chi-square test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical Features of Patients

The clinical information of the 41 patients (26 males and 15 females) with the SCN1A variants they harbored is summarized in Tables 1, 2. Of the 41 patients, 21 were classified as DS group (five of SMEI and 16 of SMEB) and 20 patients were non-DS group (four of epilepsy not conforming to definite epilepsy syndrome, 11 of GEFS+, four of FS, and one of FS+).

TABLE 1

| Patient No. |

Sex | Age at seizure onset |

Age at last follow-up |

Seizure type |

Seizure onset pattern |

Seizure evolution |

Seizure duration (common/max) |

Seizure frequency during 24 h |

Birth history |

Development history |

Family history |

EEG (first visit) |

Brain MRI |

Diagnosis (group) |

Medication trials |

Seizure condition |

| 1 | F | 7 m | 6 y 6 m | GCS, MS | FS | FS/aFS | 1-2 mi n/20 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | no | Normal | Normal | SMEI (DS) | VPA | seldom |

| 2 | M | 4 m | 5 y | GTCS, AS, FOS | aFS | FS/aFS | 20–30 min/30 min | 1 | Normal | Retardation | no | Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in posterior) |

Abnormal (subarachnoid space widening) |

SMEI (DS) | VPA LEV CLB KD |

Intermittent |

| 3 | F | 3 m | 5 y 4 m | UCS | aFS | FS/aFS | <1 min/20 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | no | Normal | Abnormal (subarachnoid space widening) |

SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV TPM KD |

Intermittent |

| 4 | F | 6 m | 4 y | UCS | aFS | aFS (fever after seizure) | 2-3 min/30 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | LEV VPA | intermittent |

| 5 | M | 5.7 m | 3 y 1 m | GCS | FS | FS/aFS | 2–15 min/70 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA | intermittent |

| 6 | F | 6 m | 2 y 11 m | sGCS, GCS | FS | FS/aFS | 1-2 min/20 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | LEV VPA | intermittent |

| 7 | M | 4 m | 3 y 3 m | sGCS | FS/aFS | FS/aFS (seizure during bathing) | 10 min/60 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | Yes/mother | Normal | Abnormal (subarachnoid space widening) |

SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV TPM | Intermittent |

| 8 | F | 4 m | 1 y 5 m | sGCS, GCS | aFS (fever after seizure) | FS/aFS | 3–5 min/40 min | 1 | Normal | Retardation | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV | Intermittent |

| 9 | F | 5 m | 8 y 1 m | GTCS, FOS | aFS | FS/aFS | 1–5 min | 1 | Normal | Retardation | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA | Intermittent |

| 10 | M | 3 m | 1 y 6 m | sGCS, MS | aFS | FS/aFS | 3–5 mi n/30 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Abnormal (generalized epilepstiform discharges) |

Abnormal (subarachnoid space widening) |

SMEI (DS) | LEV TPM | Intermittent |

| 11 | M | 12 m | 6 y | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 3-4min/6 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/mother, father | Abnormal (epilepstiform discharges in left posterior region) | Normal | GEFS+(non-DS) | LEV | Loss |

| 12 | M | 10 m | 3 y 11 m | GCS | FS | FS/aFS | 1-2 min/10 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | GEFS+(non-DS) | VPA | Loss |

| 13 | M | 10 m | 6 y 6 m | GCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 10 min/20 min | 1 | Normal | Language retardation | yes/father | Abnormal (epilepstiform discharges in left frontal and central region) |

Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | LEV | No seizure |

| 14 | F | 10 m | 4 y | GCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1-2 min/2 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | Yes/mother, grandmother | Abnormal (generalized epilepstiform discharges) |

Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | NO | Loss |

| 15 | F | 10 m | 6 y 1 m | GCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 2-3 min/6 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Not available | Normal | SMEB (DS) | LEV VPA TPM NZP | No seizure |

| 16 | F | 5 m | 9 y | GCS, FOS | aFS (seizure during bathing) | FS/aFS | 1-2 min/2 min | 2 | Abnormal (post mature delivery postnatal mild hypoxia) | Retardation | no | Normal | Abnormal (poor myelination of periventricular white matter) | SMEB (DS) | LEV VPA TPM NZP | Intermittent |

| 17 | M | 8 m | 7 y 6 m | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS | 2-3 min/3 min | 5 | Abnormal (postnatal mild hypoxia) |

Mild retardation | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA TPM | Intermittent |

| 18 | F | 11 m | 3 y 5 m | GTCS, aAS | FS/aFS | FS/aFS | 4-5 min/5 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | no | Normal | Abnormal (right hippocampal signal increased slightly) |

SMEI (DS) | VPA LEV TPM | intermittent |

| 19 | M | 10 m | 2 y 6 m | GTCS, MS, FOS | FS | FS/aFS | 1-2 min/2 min | 3 | Normal | Mild retardation | no | Abnormal (generalized epilepstiform discharges) | Abnormal (slightly enlarged lateral ventricles) |

SMEI (DS) | VPA | seldom |

| 20 | M | 12 m | 4 y 7 m | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS | 3-5 min/5 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/father, aunt, brother |

Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in Rolandic region) |

Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | LEV VPA | No seizure |

| 21 | M | 7 m | 4 y 3 m | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS (seizure during bathing) | 3 min/30 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | no | Normal | Normal | EP (non-DS) | LEV | seldom |

| 22 | F | 8 m | 2 y | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS | 5 min/5 min | 3 | Normal | Normal | no | Boundary (rare spikes infrontal and central regions) |

Normal | EP (non-DS) | VPA | intermittent |

| 23 | M | 9 m | 3 y 6 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1-2 min/30 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/grandfather, sister |

Abnormal (small spike in central region) | Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | VPA LEV | intermittent |

| 24 | M | 10 m | 2 y 10 m | GTCS | FS | aFS(fever after seizure) | 1-2 min/5 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | EP (non-DS) | No drug | No seizure |

| 25 | F | 6 m | 12 y 11 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1-2 min/6 min | 3 | Normal | Retardation | no | Not available | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV | intermittent |

| 26 | F | 1 y 2 m | 5 y | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 5-6 min/15 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/mother | Abnormal (epilepstiform discharges in posterior region) |

Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | VPA | intermittent |

| 27 | M | 8 m | 7 y 2 m | GTCS | FS | aFS | 1-2 min/2 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | NO | seldom |

| 28 | M | 11 m | 8 y | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS | 2-5 min/5 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/father | Normal | Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | VPA LEV | Loss |

| 29 | F | 7 m | 6 y 4 m | GTCS, FOS | aFS | aFS (seizure usually during infection) | 1-2 min/10 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV TPM | intermittent |

| 30 | F | 2 y | 4 y 8 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS (fever after seizure) | 5-6 min/10 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/mother | Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in right frontal, central and temporal regions) |

Normal | GEFS+ (non-DS) | VPA | Loss |

| 31 | M | 9 m | 2 y 11 m | GCS, aAS | FS | aFS | 1-3 min/10 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA | intermittent |

| 32 | M | 1 y 1 m | 2 y 7 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1-2 min/2 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Boundary (rare spikes in frontal and central regions) |

Abnormal (slightly enlarged lateral ventricles | EP (non-DS) | NO | seldom |

| 33 | M | 1 y 7 m | 8 y | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1 min/1 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | Yes/father sister | Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in frontal region) |

Abnormal (poor myelination of periventricular white matter) | GEFS+ (non-DS) | LEV | No seizure |

| 34 | M | 7 m | 10 y 11 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | aFS | 1 min/20 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | Yes/mother | Normal | Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV | seldom |

| 35 | M | 10 m | 3 y 9 m | GTCS | FS | FS/aFS | 1-2 min/30 min | 3 | Normal | Normal | no | Abnormal (rare epileptiform discharges) |

Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA | seldom |

| 36 | M | 7 m | 4 y 3 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | FS/aFS | 2 min/40 min | 1 | Normal | Mild retardation | Yes/brother | Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in left frontal region) |

Normal | SMEB (DS) | VPA LEV TPM NZP | seldom |

| 37 | M | 10 m | 8 y 8 m | GTCS | FS | FS | 5 min/5 min | 1 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | FS (non-DS) | NO | No seizure |

| 38 | M | 2 y | 9 y 2 m | GCS | FS | FS | 3-5 min/5 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | no | Not available | Normal | FS+ (non-DS) | NO | No seizure |

| 39 | M | 1 y 5 m | 7 y 5 m | GTCS, FOS | FS | FS | 2-3 min/3 min | 2 | Normal | Language retardation | Yes/mother | Not available | Normal | FS (non-DS) | NO | No seizure |

| 40 | M | 8 m | 4 y 8 m | GTCS | FS | FS | 1 min/1 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | no | Normal | Normal | FS (non-DS) | NO | No seizure |

| 41 | M | 1 y 6 m | 5 y | GTCS | FS | FS | 1-2 min/2 min | 2 | Normal | Normal | Yes/brother | Abnormal (epileptiform discharges in posterior) | Normal | FS (non-DS) | NO | No seizure |

Clinical features of patients with SCN1A variant.

AS, absence seizure; aAS, atypical absence seizure; MS, myoclonic seizures; GTCS, generalized tonic–clonic seizure; GCS, generalized clonic seizure; sGCS, secondary generalized clonic seizure; UCS, unilateral clonic seizure; FOS, focal seizure; SMEI, severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy; SMEB, severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy borderline; GEFS+, genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus; FS, febrile seizures; aFS, afebrile seizures; FS+, febrile seizures plus; EP, epilepsy; LEV, levetiracetam; TPM, topiramate; VPA, valproate; NZP, nitrazepam; CLB, chlorbazam; KD, ketogenic diet; EEG, electroencephalography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

TABLE 2

| DS group | non-DS group | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 | 16 |

| Female | 11 | 4 |

| Age at seizure onset (months) | ||

| ≤6 m | 11 | 0 |

| 7–12 m | 10 | 11 |

| ≥12 m | 0 | 9 |

| Mode of onset | ||

| Onset with febrile seizure | 11 | 20 |

| Onset with afebrile seizue | 7 | 0 |

| Onset with febrile/afebrile seizure | 2 | 0 |

| Onset with fever after seizure | 1 | 0 |

| Age at first afebrile seizure (months) among onset with febrile seizure | ||

| ≤12 m | 2 | 0 |

| 12–36 m | 7 | 6 |

| ≥36 m | 2 | 7 |

| Not available | 0 | 2 |

| Mode of seizure evolution | ||

| Evolution to afebrile seizure | 5 | 8 |

| Evolution to febrile/afebrile seizure | 15 | 4 |

| Evolution to fever after seizure | 1 | 3 |

| No seizure | 0 | 4 |

| Still febrile seizure | 0 | 1 |

| Types of seizure | ||

| Focal | 3 | 0 |

| Focal and secondary generalized | 9 | 9 |

| Generalized | 6 | 11 |

| Focal, generalized and other | 3 | 0 |

| Duration of seizure | ||

| <5 min | 3 | 6 |

| ≥5 min <10 min | 4 | 8 |

| ≥10 min <30 min | 6 | 4 |

| ≥30 min | 8 | 2 |

| Seizure frequency during one day | ||

| 1 | 15 | 13 |

| 2 | 2 | 6 |

| >2 | 4 | 1 |

| Birth history | ||

| Normal | 19 | 20 |

| Abnormal | 2 | 0 |

| Family history | ||

| Yes | 3 | 11 |

| No | 18 | 9 |

| Developmental delay | ||

| Yes | 13 | 3 |

| No | 8 | 17 |

| EEG at initial visit | ||

| Abnormal | 5 | 9 |

| Normal | 14 | 7 |

| Boundary | 0 | 2 |

| No exam | 2 | 2 |

| Brain MRI/CT | ||

| Nonspecific abnormal | 7 | 2 |

| Normal | 14 | 18 |

| Treatment | ||

| Single AEDs | 6 | 8 |

| Two AEDs | 7 | 3 |

| Three or more AEDs | 8 | 0 |

| No treatment | 0 | 9 |

| Loss follow-up | 0 | 5 |

| Seizure outcome | ||

| Still seizure | 20 | 6 |

| No seizure | 1 | 9 |

| Loss follow-up | 0 | 5 |

Summary of 41 patients’ clinical data.

In the DS group, the age of seizure onset ranged from 3 to 11 months, with a median age of 6 months. Of these, 52.4% (11/21) had seizure onset before 6 months of age, and 47.6% (10/21) had seizure onset between 7 months and 1 year of age. In the non-DS group, the age of seizure onset ranged from 7 months to 2 years, with a median age of ten and a half months. Of these, 65% (13/20) had seizure onset between 7 months and 1 year, and 35% (7/20) had seizure onset beyond 1 year of age. The age of seizure onset in the DS group was therefore significantly earlier than that in the non-DS group (p < 0.01, Supplementary File 1). Seizure onset patterns differed considerably between the two groups. The patients in the DS group had varied seizure onset patterns since 11 (52.4%) presented with febrile seizure, seven (33.3%) with afebrile seizure and one of them with seizure that occurred during bathing, two (9.5%) with febrile or afebrile seizure, and one (4.8%) with fever after seizure. However, all 20 patients in the non-DS group presented with febrile seizures as their seizure onset pattern. Further, in the DS group, among the 11 patients with febrile seizure onset, two patients evolved to afebrile seizure before the age of 1 year, seven between 1 and 3 years of age, and only two patients after the age of 3 years. In contrast, of the 20 patients in the non-DS group with febrile seizure onset, six patients progressed to afebrile seizure between 1 and 3 years of age, seven after 3 years of age, and none before 1 year of age. It can therefore be inferred that patients in DS group evolve to afebrile seizure earlier than those in non-DS group, however, there was no significant difference in the age of occurrence of the first afebrile seizure between the two groups (p > 0.05, Supplementary File 2).

In the DS group, five patients were afebrile at the time of seizure and one developed fever post seizure. The remaining 15 patients later developed febrile or afebrile seizure. Of these, seizures were triggered in four patients by elevated ambient temperature, such as during bathing or vigorous exercise. In the non-DS group, eight patients developed afebrile seizures, one of which occurred during bathing, four presented with febrile or afebrile seizure, three developed fever post seizure, four patients had no recurrence at the time of follow-up, and one patient still experienced febrile seizures. Thus, 58.5% (24/41) of the patients experienced seizures associated with fever or a hot environment with disease progression. This was markedly obvious in the DS group.

The following distribution of type of seizure was seen in the 41 patients included in this study. In the DS group, nine (42.9%) patients presented with generalized or secondary generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizure, six (28.6%) with generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizures, three (14.3%) with unilateral clonic seizures, and three (14.3%) with multiple seizures, such as unilateral clonic seizure or generalized tonic-clonic or clonic seizure, myoclonic seizure, and atypical absence seizure. In the non-DS group, nine (45%) patients presented with generalized or secondary generalized tonic-clonic or clonic seizures, and 11 (55%) with generalized tonic-clonic or clonic seizures.

The maximum duration of seizure in the DS group ranged from 2 to 70 min with a median of 20 min, while in the non-DS group it ranged from 1 to 30 min, with a median of 5 min. The duration of seizure was longer than 30 min in eight (38.1%) patients, 10–30 min in six (28.6%) patients, 5–10 min in four (19%) patients, and less than 5 min in three (14.3%) patients in the DS group. In the non-DS group, six (30%) patients had seizure episodes of less than 5 min, eight (40%) patients of 5–10 min, four (20%) patients of 10–30 min, and two (10%) patients of more than 30 min. Seizure duration was therefore significantly longer in the DS group than in the non-DS group (p < 0.05, Supplementary File 3). The two groups did not show a significant difference (p > 0.05, Supplementary File 4) with respect to frequency of seizure occurrence during a 24 h period, with 15 patients in DS group and 13 patients in non-DS group presenting with a frequency of one seizure, while two patients in DS group and six patients in non-DS group had two seizures, and four patients in DS group and one patient in non-DS group had more than two seizures.

Among the 41 patients, all except for two patients with mild hypoxia at birth had normal antenatal history. Thirteen patients in the DS group and three in the non-DS group had varying degrees of cognitive and motor development retardation. A positive family history of epilepsy or febrile seizures was recorded in 3 and 11 patients in the DS group and non-DS group, respectively.

Brain MRI of nine patients (seven in the DS group and two in the non-DS group) showed non-specific abnormalities, including four patients in DS group showed subarachnoid space widening, one patient in DS group and one patient in non-DS group showed poor myelination of periventricular white matter, one patient in DS group showed marginally higher hippocampal signal, and one in DS group and one in non-DS group showed slightly enlarged lateral ventricles. At least one electroencephalography (EEG) examination was performed on 37 patients. At the first visit, but not necessarily early in the course of the disease, EEG abnormalities including focal and generalized epileptiform discharges were seen in 14 patients (five in the DS group and nine in the non-DS group). Another two patients in the non-DS group had borderline abnormal changes and the remaining 21 patients (14 in the DS group and seven in the non-DS group) had normal EEG. In the DS group, the EEG of 14 patients were normal, of which eight patients were examined EEG before the age of 1 year at the initial stage of seizure onset, six patients were examined between 1 and 2 years old. The EEG results of remaining two patients in the DS group were unknown, which were not provided by their parents at the first visit, and the other two patients in non-DS group were diagnosed with FS and FS+, respectively without examination of EEG.

All patients were followed up with outpatient services or telephonic consultations. In the DS group, the age at last follow-up ranged from 1 year and 5 months to 12 years and 11 months, with a median of 4 years and 3 months. In the non-DS group, it ranged from 2 to 10 years and 11 months, with a median of 5 years. There was no significant difference in age at last follow-up between the two groups (p > 0.05, Supplementary File 5). At the time of follow up, 26 patients, including 20 (20/21, 95.2%) patients in the DS group and six (6/20, 30%) patients in the non-DS group continued to experience seizures. Another 10 patients, nine (9/20, 45%) patients in the non-DS group and one (1/21, 4.8%) patient in the DS group no longer suffer from seizures at present, and the remaining five were lost to follow-up. In the DS group, eight (8/21, 38.1%) patients were treated with more than three antiepileptic drugs, seven (7/21, 33.3%) with two antiepileptic drugs, and six (6/21, 28.6%) with only one antiepileptic drug. By the time of follow-up, only one patient in the DS group had not experienced seizures for 8 months after treatment with four antiepileptic drugs. In the non-DS group, eight (8/20, 40%) patients were not prescribed drugs and advised to prevent hyperthermia alongside temporary administration of sedatives to prevent convulsions during fever, six of whom experienced no seizures, and two experienced seldom seizures. The remaining two patients, one of whom no longer has seizures, and the other who rarely experience seizures, were prescribed two antiepileptic drugs. Another five patients had one antiepileptic drug, two of whom experienced no seizures, and three experienced intermittent seizures.

Genetic Characteristic of SCN1A Variants Identified in This Study

Details of the identified SCN1A variants are summarized in Tables 3, 4. Among the 41 patients, 31(75.6%) had de novo variants, including 20 patients in the DS group and 11 in the non-DS group. Inherited variants were seen in nine (22%) patients, including one patient in the DS group and eight in the non-DS group, all of whom reported a family history of febrile seizure or epilepsy. Among the patients with de novo variants, four (two in the DS group and two in the non-DS group) had a positive family history of febrile seizures despite not having inherited a pathogenic variant. Additionally, the origin of the variant identified in a single patient could not be verified due to unavailability of the father’s blood sample.

TABLE 3

| No./Phenotype | Exon | cDNA* | Variant | Location in | Mutation type | Transmission | Reported mutation |

| protein | (references) | ||||||

| (previous diagnosis) | |||||||

| 1/SMEI | 4 | c.563A > C | p.D188A | DIS2-DIS3 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 2/SMEI | 26 | c.4571delC | p.P1524Lfs*15 | DIIIS6-DIVS1 | Frameshift | De novo | No |

| 3/SMEB | 26 | c.5035delC | p.L1679X | DIVS5 | Nonsense | De novo | No |

| 4/SMEB | 16 | c.3111dupC | p.F1038Lfs*3 | DIIS6-DIIIS1 | Frameshift | De novo | No |

| 5/SMEB | 26 | c.4439G > T | p.G1480V | DIIIS6-DIVS1 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Harkin et al., 2007) MAE |

| 6/SMEB | 4 | c.272T > C | p.I91T | H3N+-DI | Missense | De novo | Yes (Sun et al., 2008) SMEI |

| 7/SMEB | 13 | c.1837C > T | p.R613X | DIS6-DIIS1 | Nonsense | Maternal | Yes (Kearney et al., 2006) SMEI |

| 8/SMEB | 25 | c.4301G > A | p.W1434X | DIIIS5-DIIIS6 | Nonsense | De novo | Yes (Zucca et al., 2008) SMEI |

| 9/SMEB | 19 | c.3759dupA | p.Y1254Ifs*3 | DIIIS2 | Frameshift | De novo | No |

| 10/SMEI | 23 | c.3981delA | p.L1327Ffs*7 | DIIIS4 | Frameshift | De novo | No |

| 11/GEFS+ | 1 | c.1852C > T | p.R618C | DIS6-DIIS1 | Missense | Maternal | Yes (Brunklaus et al., 2015) GEFS+ SMEI |

| 12/GEFS+ | 15 | c.2732_2733delinsAA | p.L911Q | DIIS5-DIIS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 13/GEFS+ | 21 | c.4112G > C | p.G1371A | DIIIS5-DIIIS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 14/GEFS+ | 2 | c.364A > G | p.I122V | H3N+-DI | Missense | Maternal | Yes (Till et al., 2020) SMBI |

| 15/SMEB | 18 | c.2791C > T | p.R931C | DIIS5-DIIS6 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Ohmori et al., 2002) SMEI |

| 16/SMEB | 28 | c.4762T > C | p.C1588R | DIVS2 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Marini et al., 2007) SMEI |

| 17/SMEB | 18 | c.2946+2T > C | (splicing) | DIIS6 | Splice site | De novo | No |

| 18/SMEI | 12 | c.2134C > T | p.R712X | DIS6-DIIS1 | Nonsense | De novo | Yes (Sugawara et al., 2002) SMEI |

| 19/SMEI | 15 | c.2134C > T | p.R712X | DIS6-DIIS1 | Nonsense | De novo | Yes (Sugawara et al., 2002) SMEI |

| 20/GEFS+ | 28 | c.4741A > G | p.I1581V | DIVS2 | Missense | Paternal | No |

| 21/EP | 6 | c.706A > T | p.I236F | DIS4-DIS5 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 22/EP | 20-29del | Partial exon deletion | De novo | No | |||

| 23/GEFS+ | 28 | c.5218G > T | p.D1740Y | DIVS5-DIVS6 | Missense | Paternal | No |

| 24/EP | 2q24.3del | 2q24.3 deletion | De novo | No | |||

| 25/SMEB | 9 | c.825T > G | p.N275K | DIS5-DIS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 26/GEFS+ | 7 | c.493T > C | p.Y165H | DIS2 | Missense | Maternal | Yes (Fernández-Marmiesse et al., 2019) SMBI |

| 27/GEFS+ | 19 | c.3867_3869delCTT | p.1289delF | DIIIS3 | Deletion | De novo | Yes (Ohmori et al., 2006) SMBI |

| 28/GEFS+ | 14 | c.2576G > A | p.R859H | DIIS4 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Volkers et al., 2011) GEFS+ |

| 29/SMEB | 5 | c.680T > G | p.I227S | DIS4 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Nabbout et al., 2003) SMEI |

| 30/GEFS+ | 26 | c.5770C > G | p.R1924G | DIVS6-CO2- | Missense | Maternal | No |

| 31/SMEB | 24 | c.4049T > C | p.V1350A | DIIIS4 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 32/EP | 18 | c.2735T > C | p.F912S | DIIS5-DIIS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 33/GEFS+ | 6 | c.G709C | p.V237L | DIS4-DIS5 | Missense | Paternal | No |

| 34/SMEB | 21 | c.4168G > A | p.V1390M | DIIIS5-DIIIS6 | Missense | De novo | Yes (Rilstone et al., 2012) SMEI |

| 35/SMEB | 17 | c.2585G > T | p.R862L | DIIS4 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 36/SMEB | 28 | c.5108A > C | p.D1703A | DIVS5-DIVS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 37/FS | 18 | c.3643G > T | p.V1215F | DIIS6-DIIIS1 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 38/FS+ | 20 | c.3973A > G | p.R1325G | DIIIS4 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 39/FS | 29 | c.5389G > T | p.A1797S | DIV-CO2 | Missense | Unknown | No |

| 40/FS | 26 | c.5078C > A | p.A1693D | DIVS5-DIVS6 | Missense | De novo | No |

| 41/FS | 28 | c.4787G > A | p.R1596H | DIVS2-DIVS3 | Missense | Paternal | Yes (Zuberi et al., 2011) GEFS+ |

Genetic characteristic of 41 SCN1A variants identified in this study.

DIS1, domain 1 segment 1; SMEI, severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy; SMEB, severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy borderline; GEFS+, genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus; EP, epilepsy not classified as a specific epileptic syndrome; FS+, febrile seizures plus; FS, febrile seizures. *Coding DNA reference sequence NM_001165963 does not contain intron sequences.

TABLE 4

| ITEM\case | DS group | Non-DS group | Total |

| 21 | 20 | 41 | |

| Genetic variation | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| De novo | 20 | 11 | 31 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Missense mutation | 11 | 17 | 28 |

| Nonsense mutation | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Frameshift | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Splice site | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deletion mutation | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Partial deletion of SCN1A exon | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2q24.3 deletion | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Summary of 41 patients’ genetic data.

The distribution of variant type in the DS group included nonsense variants in five patients, frameshift variants in four, a splice site variant in one, and missense variants in the remaining eleven. Missense variants were found in 17 patients, and the remaining three had a deletion, a partial deletion of SCN1A exon 20–29, and a 2q24.3 deletion each in the non-DS group.

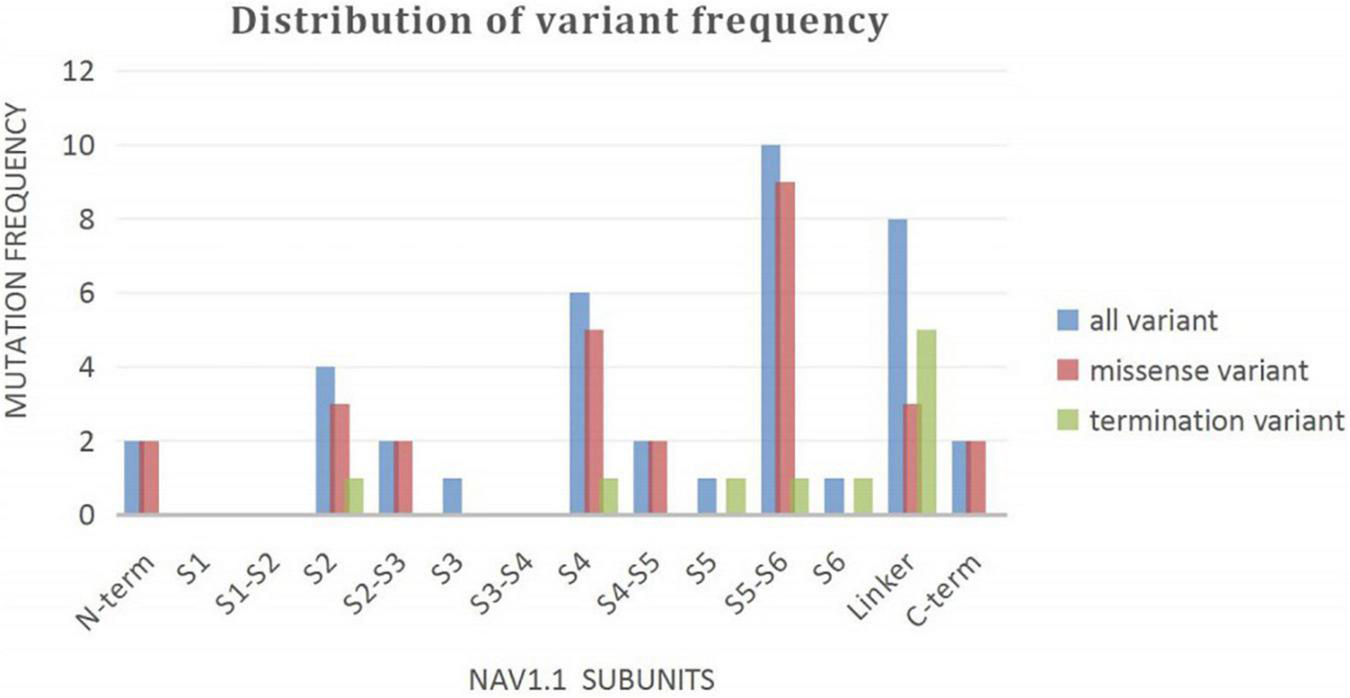

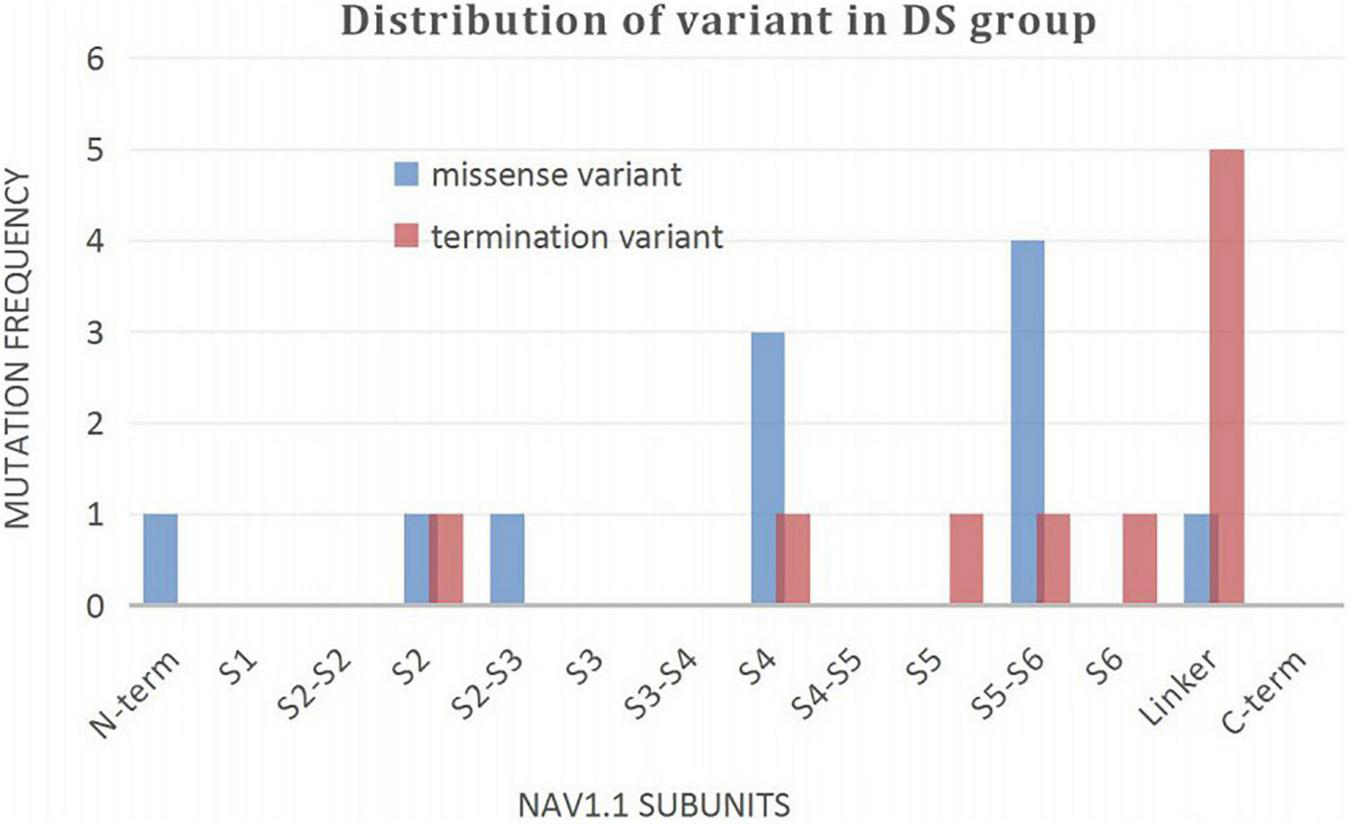

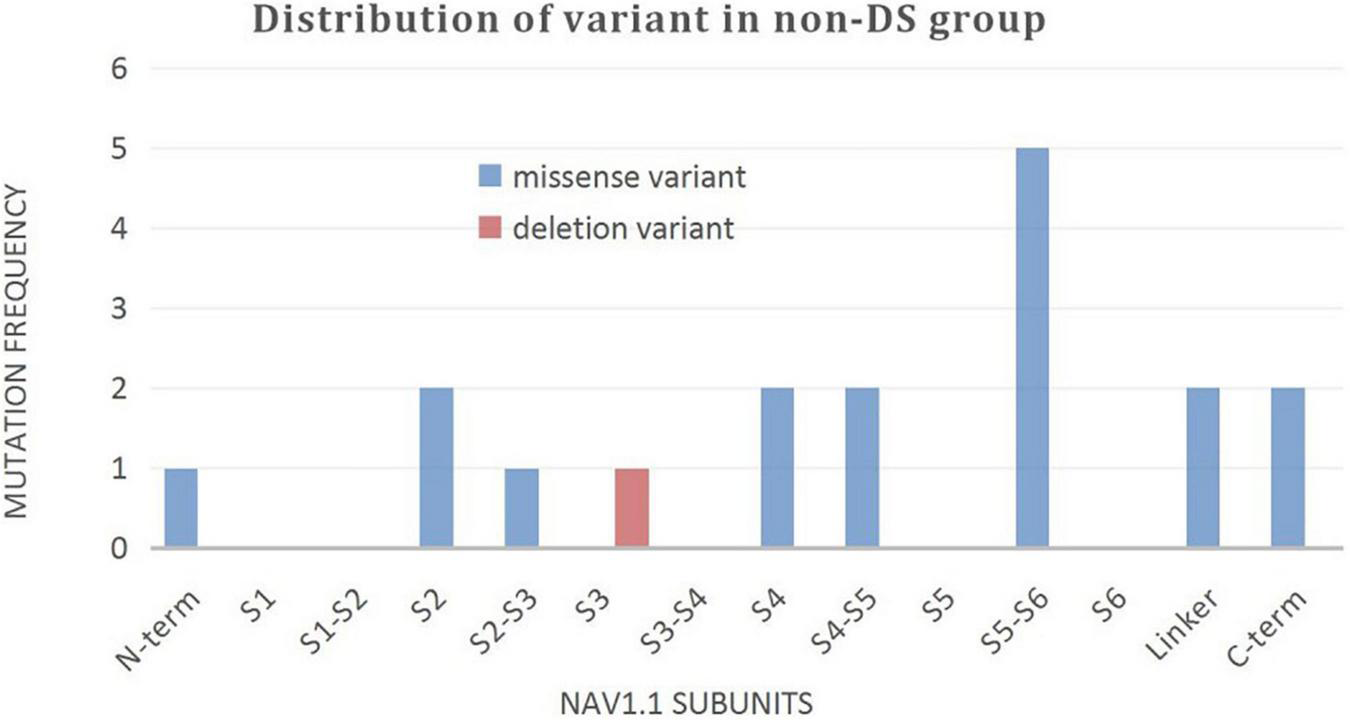

A wide distribution of the 39 SCN1A point variants identified across all domains of the sodium channels were observed (Figure 1). Of these, 10 mapped to the sodium channel pore-forming region (S5–S6), six to the voltage sensor region (S4), eight to the linker regions, and the remaining 15 were scattered evenly throughout the sodium channels Nav1.1 (Figure 2). Among the eleven missense variants in the DS group, three were located in the S4 region, four in the S5–S6 region, and the rest were evenly distributed. Of the 10 termination variants, including nonsense, frameshift, and splice site variants, five were located in the linker region, and the rest were distributed evenly (Figure 3). In the non-DS group, 17 patients harbored missense variants, of which five were located in the S5–S6 region, two in the S4 region, and the remaining were evenly distributed (Figure 4).

FIGURE 1

Structure of the human Nav1.1 channel and the location of SCN1A variants identified in this study. Nav1.1 channels α subunit consist of four homologous domains (DI–DIV), each with six transmembrane segments (S1–S6). The fourth segment (S4) of each domain functions as a voltage sensor. The S5 and S6 segments of each domain make up the pore of the channel, and the connecting loop between S5 and S6 is the pore loop. The identified variants in DS group were depicted with circle and in non-DS group with square. Missense variants are shown in blue. Nonsense variants are shown in red. Frameshift variants are shown in orange. Splice site variant is shown in pink and deletion variant in black.

FIGURE 2

Distribution of variant frequency of 39 patients with point variant in our study.

FIGURE 3

Distribution of variant in DS group.

FIGURE 4

Distribution of variant in non-DS group.

Discussion

The SCN1A gene was first associated with genetic (formerly generalized) epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) (Escayg et al., 2000). Subsequently, it was discovered that the vast majority of patients with Dravet syndrome harbored SCN1A variants with an increasing number of SCN1A variants being reported. To date, the clinical spectrum of epilepsies related to SCN1A variants encompass various phenotypes, the most common being SMEI and SMEB, and a small proportion being GEFS+, including FS and FS+. Other phenotypes included epilepsies not classified as a definite epileptic syndrome and rare early onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (Sadleir et al., 2017).

Although the 41 patients in our study presented with the same complaint of intermittent convulsions with or without fever in the early stage of the disease, other clinical manifestations were not similar. Age of seizure onset in the DS group was significantly earlier than that of the non-DS group, since all the patients were below 1 year of age, and most were symptomatic before 6 months of age. The pattern of onset in the DS group was either febrile or afebrile seizures, or an alternate occurrence of the two. In the non-DS group the only pattern of onset was febrile seizures. Patients in the DS group initially showed unilateral clonic seizure or secondary generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizures, or generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizures. However, those in the non-DS group showed generalized or secondary generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizures without unilateral clonic seizures. Longer duration of seizures as well as a greater tendency to be prone to status epilepticus was reported from patients in the DS group than those in the non-DS group. The vast majority of patients in the DS group experienced seizures with a frequency of one every 24 h, however, some in the non-DS group experienced more than two seizures in the same time period and demonstrated some clustered features. While there was no significant difference between the two groups, the age of first afebrile seizure in patients with febrile seizure at onset was slightly earlier in the DS group than in the non-DS group. To summarize, the clinical manifestations of both groups are specific and vary in terms of severity and complexity.

In spite of phenotypic differences, several core features remained consistent. Seizure-related fever was observed in 34 patients (83%) at onset, and the remaining seven patients with afebrile onset of seizure eventually developed febrile seizures in the course of the disease. In addition, 32 patients (78%) experienced seizure durations of more than 5 min, and 20 patients (50%) had prolonged seizures that lasted longer than 10 min, especially in the DS group. Consequently, in concordance with previous findings, fever-related and/or prolonged seizures are prominent phenotypes associated with SCN1A variants (Guerrini and Oguni, 2011).

The phenotype of SCN1A variant is a continuous disease spectrum ranging from the mild self-limited and drug-reactive diseases, such as GEFS+, FS, and FS+ to the severe drug-refractory developmental epileptic encephalopathies (DEE), including DS and other rare phenotypes such as myoclonic-atonic epilepsy (MAE), epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures (EIMFS), and early onset SCN1A- related DEE, which have been reported in rare cases (Wallace et al., 2001; Carranza Rojo et al., 2011; Freilich et al., 2011). With the wide application of gene sequencing technology, some focal epilepsies have been found to be associated with SCN1A variants (McDonald et al., 2017; Bisulli et al., 2019). Thus, the phenotypes of SCN1A variants possess significant heterogeneity. Many of the differences between DS and non-DS are a function of the definitions of the disease. They have common genetic etiology and are a continuous entity of a disease with a wide range of seizure types and severities. Sometimes, it is very hard to separate adjacent phenotypes with a line.

As many as 2,127 diverse variations in the SCN1A have been reported that map to almost every domain of the voltage-gated sodium channel alpha 1 subunit protein, resulting in a large assortment of potential alterations in channel function. Phenotypic variations as the consequence of SCN1A variations depend on a variety of factors including position, type, and the category of functional change induced by variants, as well as the role of other modifier genes and environmental effects (Meng et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2019). The main etiology of SCN1A associated epileptic phenotypes is closely related to its functional changes. The functional researches of SCN1A variants have confirmed that loss-of-function leading to haploinsufficiency is the main effect of both Dravet syndrome and GEFS+, although for some variants, mixed loss- and gain-of-function effects and for few variants a net gain-of-function have been observed (Mantegazza and Broccoli, 2019). Recent study has investigated that SCN1A T226M variant presents gain-of-function in early infantile development and epileptic encephalopathy which is far more severe than typical Dravet syndrome (Berecki et al., 2019). Previous studies have demonstrated the correlation of clinical severity with variant type, with missense changes resulting in milder and truncations causing severe epilepsy (Kanai et al., 2004; Stafstrom, 2009). So, genotypes determine phenotypes, the relationship appears unexpected complexity involving numerous known and unknown factors related to intrinsically complex pathophysiologic responses as well as environmental factors, which yet remain to be fully disentangled.

In our study, 10 patients in the DS group carried protein termination variants, including five nonsense, four frameshift, and one splice site variant. Termination of protein translation resulting in a short truncated protein is predicted to cause complete loss of sodium channel function and a consequent severe phenotype. The remaining eleven patients harbored missense variants, of which seven were located within functionally important domains including the sodium channel ion pore and voltage sensor regions and still had seizures up to the last follow-up, only one patient treated with four kinds of antiepileptic drugs without seizures for 8 months. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies (Ceulemans et al., 2004; Kanai et al., 2004; Zuberi et al., 2011) and demonstrate a correlation between genotype (such as the nature and location of variants) and phenotype. Of the variants associated with severe phenotypes, truncation variants are often evenly distributed in the sodium channels, while missense variants are mostly concentrated around voltage sensors and channel pores (Zuberi et al., 2011). Our results demonstrate a higher distribution of termination variants in the linker region. Given that this is a novel finding, it will be interesting to validate it in a large sample size study. About truncation variants, another situation requires attention. It is identified that few DS patients are caused by poison exons that are naturally occurring and highly conserved exons, these poison exons contain a premature termination codon, alternative splicing of such an exon is predicted to lead to nonsense mediated decay, decreasing the amount of protein produced (Carvill and Mefford, 2020; Aziz et al., 2021). Therefore, the results of nonsense mediated decay are similar to those of truncation variants.

Among the 17 patients with missense variants in the non-DS group, seven carried variants that were located within the sodium channel ion pore and voltage sensor regions. Except two patients lost to follow-up, only two patients with the phenotypes of GEFS+ and epilepsy not classified as a specific epileptic syndrome continued to experience intermittent seizures, the other three patients, including one case of GEFS+, FS and FS+, respectively, fared better with stoppage of seizure episodes. We were therefore able to conclude that variant location in a functionally important domain of the sodium channel need not necessarily translate into a serious phenotype. The reason why certain missense variations are linked to severe phenotypes, while others are not, is not well elucidated. Similarly, in the DS group, two patients with identical genotypes carrying the same nonsense variants had significantly different phenotypes, one with mild epilepsy and the other suffering from severe disease. This strongly suggests the influence of other factors including modifier genes, environmental effects, and brain development in determining the phenotypic expression of the disease (Stafstrom, 2009; Parihar and Ganesh, 2013). Genetic modifiers are genes distinct from the primary mutation that modulate the severity of the disease phenotype (Kearney, 2011). The studies identified several genetic modifiers such as Hlf, the gene encoding hepatic leukemia factor, Cacna1g, the gene encoding Cav3.1 and Gabra2, the gene encoding the GABAA receptor α2 subunit that influence the phenotypes and severity of Scn1a+/− mouse model of Dravet syndrome (Hawkins and Kearney, 2016; Calhoun et al., 2017; Hawkins et al., 2021). In addition, it is also reported that variants in Scn2a, Kcnq2, and Scn8a can dramatically influence the phenotype of mice carrying the Scn1a-R1648H mutation (Hawkins et al., 2011). The ability to study the complex genetic interactions in model organisms contributes to our understanding of the genetic factors that influence neurological disease and suggest candidate genes for follow-up study in human patients.

With the researches of the pathogenic mechanism of SCN1A-related epilepsy, especially the functional changes and genetic modifiers, there are some novel therapeutic approaches that target seizure control through genetic modulation have emerged. Due to SCN1A haploinsufficiency of most DS patients, the first precision therapy was antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) which can restore functional SCN1A mRNA and NaV1.1 levels. It was developed using Targeted Augmentation of Nuclear Gene Output (TANGO) technology (Lim et al., 2020). Another gene therapy focuses on adeno-associated virus (AAV)-delivered gene modulation. For example, an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) vector-based, GABAergic neuron-selective, which can upregulate endogenous SCN1A gene expression to prevent GABAergic neurons disinhibition (Isom and Knupp, 2021). The treatments of genetic epilepsy will no longer be solely symptomatic to control seizures, but will be transformed into genomics-driven personalized therapy for underlying molecular defects or its consequences.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. This retrospective study only includes patients who came to our hospital for diagnosis and treatment, which may result in some bias. Additionally, our sample size is small and follow-up duration was short. These limitations can be overcome by further long term follow up studies in large cohorts. Our findings will help to further understand the clinical characteristic significance of SCN1A variants. The phenotypes of SCN1A associated seizure disorder are significantly heterogeneous over a continuous spectrum from mild to severe with both commonness and individuality. The effect of variants on phenotype is not completely determined by location and type, but also due to functional changes, genetic modifiers as well as other known and unknown factors, therefore genotype-phenotype predictions cannot be easily made. Evaluation of patients in the early stage of disease, with respect to clinical manifestations and SCN1A variant features is crucial to assess disease progression for early identification of patients who may benefit most from precise medical intervention.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the medical ethics committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CC conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. CC, FF, XW, JL, XHW, and HJ collected data and carried out the initial analyses. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their cooperation in this study. We would like to thank Mr. Kangkang Peng for helping to complete figures and tables as well as some statistical calculations. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2022.821012/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aziz M. C. Schneider P. N. Carvill G. L. (2021). Targeting poison exons to treat developmental and epileptic encephalopathy.Dev. Neurosci.43241–246. 10.1159/000516143

2

Berecki G. Bryson A. Terhag J. Maljevic S. Gazina E. V. Hill S. L. et al (2019). SCN1A gain of function in early infantile encephalopathy.Ann. Neurol.85514–525. 10.1002/ana.25438

3

Bisulli F. Licchetta L. Baldassari S. Muccioli L. Marconi C. Cantalupo G. et al (2019). SCN1A mutations in focal epilepsy with auditory features: widening the spectrum of GEFS plus.Epileptic Disord.21185–191. 10.1684/epd.2019.1046

4

Brunklaus A. Ellis R. Stewart H. Aylett S. Reavey E. Jefferson R. et al (2015). Homozygous mutations in the SCN1A gene associated with genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus and Dravet syndrome in 2 families. Eur. J. Paediat. Neurol. 19, 484–488. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.02.001

5

Calhoun J. D. Hawkins N. A. Zachwieja N. J. Kearney J. A. (2017). Cacna1g is a genetic modifier of epilepsy in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome.Epilepsia58e111–e115. 10.1111/epi.13811

6

Carranza Rojo D. Hamiwka L. McMahon J. M. Dibbens L. M. Arsov T. Suls A. et al (2011). De novo SCN1A mutations in migrating partial seizures of infancy.Neurology77380–383. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227046d

7

Carvill G. L. Mefford H. C. (2020). Poison exons in neurodevelopment and disease.Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.6598–102. 10.1016/j.gde.2020.05.030

8

Ceulemans B. P. Claes L. R. Lagae L. G. (2004). Clinical correlations of mutations in the SCN1A gene: from febrile seizures to severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy.Pediatr. Neurol.30236–243. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.10.012

9

Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy (1989). Commission on classification and terminology of the international league against epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes.Epilepsia30389–399. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316

10

Escayg A. MacDonald B. T. Meisler M. H. Baulac S. Huberfeld G. An-Gourfinkel I. et al (2000). Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2.Nat. Genet.24343–345. 10.1038/74159

11

Fang Z. X. Hong S. Q. Li T. S. Wang J. Xie L. L. Han W. et al (2019). Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of SCN1A-related epilepsy in Chinese children.NeuroReport30671–680. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001259

12

Fernández-Marmiesse A. Roca I. Díaz-Flores F. Cantarín V. Pérez-Poyato M. S. Fontalba A. et al (2019). Rare variants in 48 genes account for 42% of cases of epilepsy with or without neurodevelopmental delay in 246 pediatric patients. Front. Neurosci. 13:1135. 10.3389/fnins.2019.01135

13

Freilich E. R. Jones J. M. Gaillard W. D. Conry J. A. Tsuchida T. N. Reyes C. et al (2011). Novel SCN1A mutation in a proband with malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy.Arch. Neurol.68665–671. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.98

14

Fujiwara T. Sugawara T. Mazaki-Miyazaki E. Takahashi Y. Fukushima K. Watanabe M. et al (2003). Mutations of sodium channel alpha subunit type 1 (SCN1A) in intractable childhood epilepsies with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures.Brain126531–546. 10.1093/brain/awg053

15

Guerrini R. Oguni H. (2011). Borderline Dravet syndrome: a useful diagnostic category?Epilepsia52(Suppl. 2) 10–12. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.02995.x

16

Harkin L. A. McMahon J. M. Iona X. Dibbens L. Pelekanos J. T. Zuberi S. M. et al (2007). The spectrum of SCN1A-related infantile epileptic encephalopathies. Brain130, 843–852. 10.1093/brain/awm002

17

Hawkins N. A. Martin M. S. Frankel W. N. Kearney J. A. Escayg A. (2011). Neuronal voltage-gated ion channels are genetic modifiers of generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus.Neurobiol. Dis.41655–660. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.016

18

Hawkins N. A. Nomura T. Duarte S. Barse L. Williams R. W. Homanics G. E. et al (2021). Gabra2 is a genetic modifier of Dravet syndrome in mice.Mamm. Genome32350–363. 10.1007/s00335-021-09877-1

19

Hawkins N. A. Kearney J. A. (2016). Hlf is a genetic modifier of epilepsy caused by voltage-gated sodium channel mutations.Epilepsy Res.11920–23. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.016

20

Isom L. L. Knupp K. G. (2021). Dravet syndrome: novel approaches for the most common genetic epilepsy.Neurotherapeutics181524–1534. 10.1007/s13311-021-01095-6

21

Kanai K. Hirose S. Oguni H. Fukuma G. Shirasaka Y. Miyajima T. et al (2004). Effect of localization of missense mutations in SCN1A on epilepsy phenotype severity.Neurology63329–334. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129829.31179.5b

22

Kearney J. A. (2011). Genetic modifiers of neurological disease.Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.21349–353. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.12.007

23

Kearney J. A. Wiste A. K. Stephani U. Trudeau M. M. Siegel A. RamachandranNair R. et al (2006). Recurrent de novo mutations of SCN1A in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy.Pediat. Neurol. 34, 116–120. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.07.009

24

Lim K. H. Han Z. Jeon H. Y. Kach J. Jing E. Weyn-Vanhentenryck S. et al (2020). Antisense oligonucleotide modulation of non-productive alternative splicing upregulates gene expression.Nat. Commun.11:3501. 10.1038/s41467-020-17093-9

25

Mantegazza M. Broccoli V. (2019). SCN1A/NaV1.1 channelopathies: mechanisms in expression systems, animal models, and human iPSC models.Epilepsia60(Suppl. 3) S25–S38. 10.1111/epi.14700

26

Marini C. Mei D. Temudo T. Ferrari A. R. Buti D. Dravet C. et al (2007). Idiopathic epilepsies with seizures precipitated by fever and SCN1A abnormalities. Epilepsia48, 1678–1685. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01122.x

27

McDonald C. L. Saneto R. P. Carmant L. Sotero de Menezes M. A. (2017). Focal seizures in patients with SCN1A mutations.J. Child Neurol.32170–176. 10.1177/0883073816672379

28

Meng H. Xu H. Q. Yu L. Lin G. W. He N. Su T. et al (2015). The SCN1A mutation database: updating information and analysis of the relationships among genotype, functional alteration and phenotype.Hum. Mutat.36573–580. 10.1002/humu.22782

29

Myers K. A. Burgess R. Afawi Z. Damiano J. A. Berkovic S. F. Hildebrand M. S. et al (2017). De novo SCN1A pathogenic variants in the GEFS+ spectrum: not always a familial syndrome.Epilepsia58e26–e30. 10.1111/epi.13649

30

Nabbout R. Gennaro E. Bernardina B. D. Dulac O. Madia F. Bertini E. et al (2003). Spectrum of SCN1A mutations in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Neurology60, 1961–1967. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000069463.41870.2f

31

Ohmori I. Kahlig K. M. Rhodes T. H. Wang D. W. George A. L. (2006). Nonfunctional SCN1A is common in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy.Epilepsia47, 1636–1642. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00643.x

32

Ohmori I. Ouchida M. Ohtsuka Y. Oka E. Shimizu K. (2002). Significant correlation of the SCN1A mutations and severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295, 17–23. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00617-4

33

Parihar R. Ganesh S. (2013). The SCN1A gene variants and epileptic encephalopathies.J. Hum. Genet.58573–580. 10.1038/jhg.2013.77

34

Rilstone J. J. Coelho F. M. Minassian B. A. Andrade D. M. (2012). Dravet syndrome: seizure control and gait in adults with different SCN1A mutations. Epilepsia53, 1421–1428. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03583.x

35

Sadleir L. G. Mountier E. I. Gill D. Davis S. Joshi C. DeVile C. et al (2017). Not all SCN1A epileptic encephalopathies are Dravet syndrome: early profound Thr226Met phenotype.Neurology891035–1042. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004331

36

Scheffer I. E. Nabbout R. (2019). SCN1A-related phenotypes: epilepsy and beyond.Epilepsia60 (Suppl. 3) S17–S24. 10.1111/epi.16386

37

Scheffer I. E. Zhang Y. H. Jansen F. E. Dibbens L. (2009). Dravet syndrome or genetic (generalized) epilepsy with febrile seizures plus?Brain Dev.31394–400. 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.01.001

38

Stafstrom C. E. (2009). Severe epilepsy syndromes of early childhood: the link between genetics and pathophysiology with a focus on SCN1A mutations.J. Child Neurol.24(Suppl. 8) 15S–23S. 10.1177/0883073809338152

39

Sugawara T. Mazaki-Miyazaki E. Fukushima K. Shimomura J. Fujiwara T. Hamano S. et al (2002). Frequent mutations of SCN1A in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Neurology58, 1122–1124. 10.1212/wnl.58.7.1122

40

Sun H. H. Zhang Y. H. Liang J. M. Liu X. Y. Ma X. W. Qin J. (2008). Seven novel SCN1A mutations in Chinese patients with severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Epilepsia49, 1104–1107. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01549_2.x

41

Till A. Zima J. Fekete A. Bene J. Czakó M. Szabó A. et al (2020). Mutation spectrum of the SCN1A gene in a Hungarian population with epilepsy. Seizure74, 8–13. 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.10.019

42

Volkers L. Kahlig K. M. Verbeek N. E. Das J. H. G. Kempen M. J. A. Stroink H. et al (2011). Nav 1.1 dysfunction in genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures-plus or Dravet syndrome. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 1268–1275. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07826.x

43

Wallace R. H. Scheffer I. E. Barnett S. Richards M. Dibbens L. Desai R. R. et al (2001). Neuronal sodium-channel alpha1-subunit mutations in generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus.Am. J. Hum. Genet.68859–865. 10.1086/319516

44

Wirrell E. C. Laux L. Donner E. Jette N. Knupp K. Meskis M. A. et al (2017). Optimizing the diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome: recommendations from a North American consensus panel.Pediatr. Neurol.6818–34. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.01.025

45

Zhang Y. H. Burgess R. Malone J. P. Glubb G. C. Helbig K. L. Vadlamudi L. et al (2017). Genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus: refining the spectrum.Neurology891210–1219. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004384

46

Zuberi S. M. Brunklaus A. Birch R. Reavey E. Duncan J. Forbes G. H. (2011). Genotype phenotype associations in SCN1A-related epilepsies.Neurology76594–600. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c309b

47

Zucca C. Redaelli F. Epifanio R. Zanotta N. Romeo A. Lodi M. et al (2008). Cryptogenic epileptic syndromes related to SCN1A: twelve novel mutations identified. Arch. Neurol. 65, 489–498. 10.1001/archneur.65.4.489

Summary

Keywords

epilepsy, sodium channel, SCN1A , genetic, generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy, dravet syndrome

Citation

Chen C, Fang F, Wang X, Lv J, Wang X and Jin H (2022) Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics of SCN1A Associated Seizure Diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15:821012. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.821012

Received

23 November 2021

Accepted

09 March 2022

Published

28 April 2022

Volume

15 - 2022

Edited by

Yuwu Jiang, Peking University First Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Lori L. Isom, University of Michigan, United States; Atsushi Ishii, Fukuoka Sanno Hospital, Japan

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Chen, Fang, Wang, Lv, Wang and Jin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunhong Chen, sjkbch@sina.com

This article was submitted to Brain Disease Mechanisms, a section of the journal Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.