Abstract

Despite significant advancements in pharmaceutical sciences, conventional drug delivery system remains limited by issues like poor permeability, toxicity, suboptimal efficacy, and inadequate targeting. These challenges pose substantial barrier to effective treatment for complex conditions like cancer, heart problems, chronic pain management, etc. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN), with their remarkable structural tunability and multifunctionality, have emerged as a transformative solution in the realm of drug delivery system. This review delves into the state-of-the-art synthesis methods of MSNs including physical, chemical, top down and bottom-up approaches with particular attention to the widely used Sol-Gel process. We also explore innovative drug loading strategies and controlled release mechanisms, underscoring how factors such as pore size, particle shape, and surface charge influence therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, we highlight the burgeoning applications of MSNs across multiple domains, ranging from anticancer therapy and gene delivery to emerging fields such as precision agriculture and environmental remediation. Recent studies demonstrate the versatility of MSNs in addressing both biomedical and ecological challenges, making them an indispensable tool in modern science. By synthesizing Collectively, this review aims to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and practitioners, fostering continued innovation in the design and application of MSN-based nanotechnology.

1 Introduction

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have garnered significant attention from academia and the pharmaceutical industry in the last 20 years as potential drug delivery systems (DDS) (Trzeciak et al., 2021a). Polymeric based nanoparticles (Kankala et al., 2017), dendrimers (Kankala et al., 2018), and lipid based (Gong et al., 2015) have resulted in treatment process of many diseases including infectious disorders. Both organic and inorganic type nanoparticles have been studied thoroughly for its application in medicine (Alhariri et al., 2013). Iron oxide and quantum dots are being marketed. Carbon dots, silica nanoparticles, layered double hydroxide nanoparticles, other metal oxide nanoparticles like gold or silver are also used in therapeutic activities (Deshpande et al., 2013; Puri et al., 2009). Cornell dots combining radioactive iodide and organic colors are approved for phase one trials (Gad et al., 2016), Because of its highly biocompatible nature, variable surface functionalization properties, and flexible structure and composition, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are a prime example of nanotechnology used in biomedicine (Xu et al., 2023). For many years, researchers have faced great difficulty when it comes to drug nano-formulations. It is still very difficult to design safe, biocompatible devices that deliver exact medication concentrations to specific areas via in vivo barriers. Using intelligent drug delivery systems (DDS) is a viable approach to solving this problem. In this effort, mesoporous silica shows promise as a material. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have been around since the early 1990s and have been used in a wide range of scientific fields and businesses, including molecular biology, electrochemistry, heterogeneous catalysis, and analytical chemistry. The first time these nanostructured materials were used in pharmacy was in 2001, when MCM-41 silica was used for the first time in ibuprofen release methods by Vallet-Regi et al. (2001). This ground-breaking study stimulated ongoing investigation into the potential of mesoporous particles as drug delivery system carriers. Interestingly, silica has uses in food additives and cosmetics and is FDA-approved as “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) (Huang R. et al., 2020). In a positive step, the US FDA approved small silica nanoparticles as imaging agents for a human clinical study (Phillips et al., 2014a). Scientists are encouraged by this discovery that MSNs might be used as drug-delivery vehicles in clinical settings. Additionally, research using simulated bodily fluids has shown that mesoporous silica nanoparticles degrade in three stages after delivery; this characteristic is helpful for the kinetics of drug release (Lin et al., 2012). Mesoporous silica nanoparticles are silica compounds at the nanoscale that have porous properties, as the name implies. MSNs have pores of a diameter of 2–50 nm, according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification (Isa et al., 2019). Nanomaterials also referred to as nanomedicine, are used to deliver medications and may have sizes as small as hundreds of nanometers (Pillai et al., 2019). The Mobil Oil Research Group found and named it M41S (Kresge et al., 1992). It was by chance that this was discovered. M41S exhibited large pore volumes, variable pore sizes, thin amorphous walls, high surface area, and low Bronsted acidity (Kresge et al., 2004; Habeche et al., 2020). The three main members of M41S are MCM-41, MCM-48, and MCM-50. MCM-48 features cubic mesostructured gyroidic phase Ia3d, MCM-41 has a hexagonal pore structure, and MCM-50 has a lamellar geometry consisting of silicate or porous aluminosilicate layers divided by surfactant layers (Rahikkala et al., 2018).

Due to its complex manufacturing and thermal instability, MCM-48 and MCM-50 are the least studied (Habeche et al., 2020), as shown in Figure 1. Various kinds of MSNs have been discovered, such as hollow MSNs, amorphous family (SBA-n) from Fudan University (FDU), folded sheet mesoporous material-16 (FSM-16) (Santa Barbara Pharmaceuticals 2021), and others (Chew et al., 2010). This section looks into both new and current methods for creating MSNs. Because of their superior physicochemical stability, biocompatibility, one-step functionalization, large surface area and pore volume, easy production, and customizable particle size and shape, MSNs are often used as drug delivery agents as mentioned in Table 1 (Niculescu, 2020).

FIGURE 1

Representation of various mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) with distinct structural classifications (He et al., 2018).

TABLE 1

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| High surface area | Difficulty in size distribution |

| Flexible structure and composition | Stable colloidal suspension is difficult |

| Better Biocompatibility | When the silanol group’s surface density interacts with the phospholipid in the red blood cell membrane, MSNPs may cause haemolysis in the cell |

| High pore volume | Can lead to melanoma production due to metabolic charges induced by porous silica nanoparticles |

| Harmonious loading capacity | Increase in elimination rate through urine is seen with particle size |

| Increased bioavailability | |

| Well defined surface properties | |

| Two functional surfaces (cylindrical pore and exterior particle) | |

| Regarded as the most advantageous substance with great potential for treating cancer and other difficult diseases |

Summary of the advantages and limitations of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) in biomedical applications (Jyothirmayi et al., 2024).

2 Synthesis of MSNPs

For the synthesis of MSN multiple adjustments can be done like changes in pH, Surfactant and silica source. Hollow silica Nanoparticles (HSN) sub class of mesoporous silica nanoparticles are widely used for increasing drug loading and pore volume., can be prepared by various techniques like soft templating method (single vessel templating, vesicle templating and micro emulsion templating method), hard templating method and polymerlatexes-templating method, stober method, sol gel method and many more (Jyothirmayi et al., 2024).

There are four significant nanoparticle kinds synthesis methods: physical, chemical, and bottom-up and top-down. Physical synthesis methods include procedures such as inert gas condensation, severe plastic deformation, ultrasonic shot peeling, high-energy ball milling, grinding, and pyrolysis. These procedures are routinely used to create metallic nanoparticles (Maribel et al., 2009). Chemical techniques depend on chemical reduction processes (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2000), electrochemical operations (Sharma et al., 2009) or phytochemical reduction (Raspolli Galletti et al., 2013). Examples include microemulsion, chemical coprecipitation, chemical vapor condensation, and pulse electrodeposition. The most common chemical synthesis is Sol-gel.

Bottom-up approaches begin at the atomic level and continue with the synthesis of molecules. In the top-down technique, the resultant nanoparticles have a higher beginning size. To obtain the required size, mechanical methods or acid additions are used to decrease particle size (Mallick et al., 2004).

The Chemical approaches for nanoparticle production are toxic and dangerous substances, endangering biological systems and the environment (Shankar et al., 2005). In response to these issues, green nanotechnology has evolved as an essential subfield of nanotechnology. Green nanotechnology focuses on safe and eco-friendly techniques for nanomaterial manufacturing, offering an alternative to traditional physical and chemical synthesis processes. Green nanotechnology uses microorganisms such as fungi, algae, and bacteria, as well as plant extracts, including biomolecules like proteins, enzymes, amino acids, and vitamins. These natural sources play an essential role in bio reduction, bioleaching, and nanoparticle production (Van Emden et al., 1988). Green nanotechnology is gaining popularity because it eliminates toxic chemical reagents, resulting in more effective and cost-efficient product synthesis (Raspolli Galletti et al., 2013).

2.1 Sol-gel process

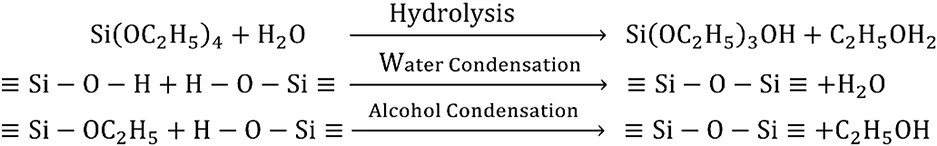

The Sol-Gel process allows for the production of nanoparticles in a variety of sizes to meet specific requirements. The Sol-Gel approach relies on condensation hydrolysis reactions using organic silicone precursors like TEOS or TMOS. During this process, the precursors are hydrolyzed under acidic conditions to produce silanol (Si-OH). These silanol groups then condense to create siloxane (Si-O-Si) bonds, which ultimately contribute to gel formation. Several templates, including CTAB, are employed to cause mesoporosity. Following gel formation, drying and calcination are used to remove solvent and surfactant molecules, resulting in the development of mesoporous silica. The hydrolysis and condensation processes produce a new phase known as the “Sol”, which is subsequently converted into the “Gel” phase by particle condensation (Kinnari et al., 2011; Brinker and Scherer, 1990).

The general reactions of TEOS that lead to the formation of silica particles in the sol-gel process can be written as given below.

The Stober technique is a remarkable version of the Sol-Gel technology with unique characteristics (Kurdyukov et al., 2018). This approach is very effective in producing monodispersed silicon nanoparticles ranging in size from 50 to 2000 nm. It does this by using ammonia as a catalyst, alcohol as a reaction media, and TEOS (Stöber et al., 1968) as a precursor. MSNPs synthesized using the Stober technique have an organized structure with consistent mesopores of fewer than 100 nm. Additionally, they have specified surface areas that range from 600 to 1,000 m2/g and pore volumes spanning from 0.6 to 1.0 mL/g (Wang et al., 2014).

Initially, Grun et al. pioneered the creation of sub micrometer-scaled MCM-41 particles utilizing a modified Stober technique (Grün et al., 1997). These particles were then further refined, culminating in 100 nm particles using a dilute surfactant solution (Cai et al., 2001). To create MSNPs smaller than 50 nm, procedures such as dialysis or a dual surfactant approach have been used, as mentioned in (Suzuki et al., 2004).

In an ideal situation, MCM-41 100 nm particles are synthesized by adding TEOS to a hot basic aqueous solution of CTAB (pH 11). Nanoparticles are produced using base-catalyzed Sol-Gel Condensation and hexagon-shaped micelles (Coti et al., 2009; Wu SH. et al., 2011).

3 Various loading processes

In recent days, silica bases are extensively utilized carriers for medicinal substances, with the amorphous form being the most widespread because of its lesser harmful effects than crystalline silica (Buyuktimkin and Wurster, 2015; McCarthy et al., 2016; Bharti et al., 2015; Jeelani et al., 2020; Miura et al., 2010; Carvalho et al., 2020). The properties of silica structure may be improved by regulating its pores and creating organized mesopore silica particles (Jeelani et al., 2020; Chircov et al., 2020), which has a high surface area (>700 m2/g) and pore volume (over 1 cm2/g), resulting in regulated release (Zid et al., 2020). MSNs have two surfaces: an inner and outer membrane. This outer membrane may help to improve the efficiency of targeted distribution (Natarajan and Selvaraj, 2014; Le et al., 2019). The most frequent MSNs are HMS (hollow mesoporous silica), MSU (Michigan State University), and MCF (meso cellular form), among others. Now, MSNP loading techniques are classified into two types such as solvent-based methods (wet method) and solvent-free methods, as illustrated in Figure 2 (Seljak et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019). Adsorption, solvent evaporation, incipient wetness impregnation, diffusion-supported loading, one-pot drug loading, co-spraying, and covalent grafting are some examples of solvent-based approaches. Physical mixing, melting, co-milling, and microwave irradiation are all solvent-free processes. The most common methods are solvent evaporation, adsorption, incipient wetness impregnation, melt method, and co-miling, in which the desired drug is adsorbed onto the surface of the MSNP under favorable conditions that promote drug carrier interaction such as van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and so on (Andersson et al., 2004). Drug loading varies based on surface area and affinity to silica substrate (Singh et al., 2011; Lehto et al., 2014). A comprehensive overview of drug loading methods utilizing mesoporous silica particles (MSPs), categorized by drug type, Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) class are listed in Table 2.

FIGURE 2

Illustration of various drug loading techniques categorized into solvent-based and solvent-free methods.

TABLE 2

| Drug | BCS class | Msp | Loading method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisolone | I | SBA-15 SBA-3 FDU-12 |

Adsorption |

Ambrogi et al. (2007)

Maleki and Hamidi (2016) |

| Atorvastin | II | SBA-15 | Solvent evaporation | Thomas et al. (2010) |

| Carbamazepine | SBA-16 MCM-41 SBA-15 SBA-15 OMS |

Adsorption Adsorption Incipient wetness Solvent evaporation Liquid solid technique |

Ambrogi et al. (2008)

Ambrogi et al. (2013) Trzeciak et al. (2020) Chen et al. (2012) Hu et al. (2012) |

|

| Carvedilol | SBA-16 MCM-41 SBA-15 SBA-15 OMS |

Adsorption Adsorption Incipient wetness Solvent evaporation Liquid solid technique |

Ambrogi et al. (2008)

Ambrogi et al. (2013) Trzeciak et al. (2020) Chen et al. (2012) Hu et al. (2012) |

|

| Celecoxib | MCM-41 SBA-16 |

Solvent evaporation | Gunaydin and Yılmaz (2015) | |

| Felodipine | MCM-41 SBA-15 |

Adsorption |

Eren et al. (2016)

Wu et al. (2014) |

|

| Econazole | MSN | Solvent evaporation | Ambrogi et al. (2010) | |

| Danazol | MCM-41 | Melting | Van Speybroeck et al. (2011) | |

| Glibenclamide | SBA-15 | Incipient wetness | Trzeciak et al. (2020) | |

| Griseofulvin | SBA-15 | Incipient wetness | Jambhrunkar et al. (2014) | |

| Ibuprofen | MCM-41 | Solvent evaporation | Hillerström et al. (2009) | |

| MCM-41 SBA-15 |

DiSupLo Liq. CO2 co-spraying incipient wetness Adsorption covalent grafting Adsorption Incipient wetness Solvent evaporation Melting Co-spray drying Co-milling |

Rosenholm et al. (2009)

Shen et al. (2011) Tourné-Péteilh et al. (2003) Mellaerts et al. (2008) Mellaerts et al. (2008) Heikkilä et al. (2007) Shen et al. (2010) Wang et al. (2015a) Wang et al. (2015a) Wang et al. (2015a) Malfait et al. (2019) Hu et al. (2011) |

||

| Indomethacin | SBA-16 MCM-41 SBA-15 |

Solvent evaporation Solvent evaporation Adsorption Incipient wetness Solvent evaporation |

Wang et al. (2013a)

Limnell et al. (2011) Guo et al. (2013) Jambhrunkar et al. (2014) Limnell et al. (2011) |

|

| Rufinamide | SBA-16 | Adsorption | Ambrogi et al. (2008) | |

| Ketoconazole | SBA-15 | Incipient wetness | Trzeciak et al. (2020) | |

| Naproxen | MCM-41 SBA-15 |

Adsorption | Zhang et al. (2010) | |

| Nifedipine | SBA-15 | Incipient wetness | Trzeciak et al. (2020) | |

| Telmisartan | MSN | Solvent evaporation | Horcajada et al. (2004) | |

| Aceclofenac | MCM-41 | Solvent evaporation | Kumar et al. (2014) | |

| Flurbiprofen | COK-12 | One pot silicate synthesis and drug loading | Kerkhofs et al. (2015) | |

| Atenolol | III | SBA-16 | Adsorption | Andrade et al. (2012) |

| Methotrexate | MCM-41 | Adsorption | Vadia and Rajput (2012) | |

| Furosemide | IV | MCM-41 SBA-15 |

Solvent evaporation |

Ambrogi et al. (2012a)

Ambrogi et al. (2012b) |

| Paclitaxel | MSN | Adsorption | Jia et al. (2012) |

Comprehensive overview of drug loading methods utilizing mesoporous silica particles (MSPs), categorized by drug type, Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) class, and literature references (Maleki et al., 2017).

4 Solvent based method

Such method is used to Increase the drug release kinetics through MSN.

4.1 Adsorption method

Mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) are submerged in a concentrated drug solution, which causes drug molecules to adhere to their surfaces. These drug-laden MSN are then isolated from the solution using filtering or centrifugation before being dried to eliminate any leftover solvent remnants (Xie et al., 2016)., Because of its low operating temperature, the adsorption technique is frequently employed for both hydrophilic (Brás et al., 2014) and hydrophobic medicines (Li and Zhang, 2006), as well as thermally sensitive compounds. However, with poorly soluble medications, getting a high drug solution concentration is problematic (Xie et al., 2016), as an increase in the concentration of drug solution results in mesopores obstructions and a reduction in loading surface area (Zheng et al., 2019). Another barrier is time consumption, which is compounded by uncertain medication loading levels and high drug waste (Šoltys et al., 2019). Nonetheless, solvent selection significantly impacts the drug loading process; the solvent with the most significant active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) solubility may not be optimum. For example, valsartan loaded better in dichloromethane than in methanol despite the latter’s more significant concentration. Similarly, aprepitant showed thrice greater loading in chloroform than in methanol (Charnay et al., 2004). Charnay et al. found that using polar solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl formamide resulted in poor ibuprofen loading into MCM-41 material (Mellaerts et al., 2008).

4.2 Incipient wetness impregnation method

For the synthesis of catalysts (Campanati et al., 2003; Van Speybroeck et al., 2009) and drug loading into mesoporous particles (Trzeciak et al., 2020; Mellaerts et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2015a), this approach works well. This process involves adding a concentrated drug solution, dropwise, to the silica, so that the drug’s volume matches the pore volume. The drug-diffusing wet powder is then dried for 24 h, vacuum-pressed for 48 h at 40°C (Wang et al., 2015a), and excess drug coating is removed by washing with a solvent. Washing to get rid of extra medication is a crucial step that has a significant impact.

Washing MCM-41 decreased the quantity of encapsulated ibuprofen from 1,350 to 500 mg/g, according to Charnay et al. (Mellaerts et al., 2008). This process’s primary benefits are the accurate measurement of the drug load (Wang et al., 2015a) and the complete use of a sizable MSN pore capacity. High concentrated drug solution and repeated impregnation are utilised to achieve a high degree of drug loading (5%–40% w/w) (Šoltys et al., 2019).

4.3 Solvent evaporation method

It is also a frequently employed procedure that includes solvent evaporation, which modifies the physical state, localization, and rate of release from the carrier, and adsorption, which removes the solvent via filtering and results in drug loss (Wang et al., 2015a; Abd-elbary et al., 2014). To create drug-loaded MSN, the silica is now dissolved in a volatile organic solution such as ethanol or dichloromethane and dried using a rotary evaporator (Ambrogi et al., 2012b) or heating (Maleki et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Deraz, 2017). Mellaerts et al. used solvent evaporation and incipient wetness impregnation techniques to load itraconazole and ibuprofen onto SBA-15 Silica (Trzeciak et al., 2020).

4.4 Diffusion supported loading (DiSupLo) method

Potrezebowski et al.'s DiSupLo methodology provides an easy-to-use method for packing medications inside mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) (Liu et al., 2012). A predetermined amount of MSN and a pre-homogenized drug combination are added to an open weighing vessel, which is then in a sealed vessel and left to sit at room temperature for 3 hours with ethanol within. Using NMR, the length of the drug-loading process is tracked every 30 min. Eventually, the drug-loaded sample’s ethanol is thermally extracted. This method’s adaptability is proven by loading nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, and ketoprofen into MCM-41 pores. Multiple investigations have shown good medication integration utilizing a 1:3 weight ratio of API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) to MCM-41, with filling factors of 33% and 50%, respectively. When a 1:1 ratio is used, a part of the API is located within the pore with a filling factor of roughly 60%, while the remaining stays on the exterior wall of MCM-41 (Liu et al., 2012). When the API/MSN weight ratio is less than the maximum filling factor, the DiSupLo technique allows for high drug loading and full API encapsulation. While most research focuses on single-drug loading and seldom investigates complexity, binary, or ternary systems (Rosenholm et al., 2009; Ahern et al., 2012), this approach allows for the simultaneous loading of two or more components with the appropriate drug composition (Liu et al., 2012).

4.5 Supercritical fluid technology method

In addition to MSN medication loading, it is often employed in food and chromatography (Bouledjouidja et al., 2016; Kompella and Koushik, 2001; Pasquali and Bettini, 2008). Supercritical fluids are utilized here because they have various benefits over organic solvents, such as liquid-like density, gas-like viscosity, low interfacial tension, and so on, which give them an edge as an impregnating agent (Bush et al., 2007). The supercritical phase allows for easier transfer of solubilized substances to the solid matrix, resulting in faster and more uniform impregnation than in the liquid phase. CO2 is a popular solvent because of its moderate critical condition (31.2°C, 7.4 MPa) in the SCF process. It is also inert, non-flammable, and non-toxic. (Kompella and Koushik, 2001; Wang LH. et al., 2013). The SCF approach offers an alternate method of loading onto silica that reduces processing time to 2 h (Hillerström et al., 2014). Stan et al. demonstrated that a relatively modest concentration of ibuprofen in nonpolar liquid CO2 was sufficient to produce the maximal loading of MCM-41 (Gurikov and Smirnova, 2018). Despite the benefits of SCF, multiple investigations have shown that many medications have low SCCO2 solubility (Kerkhofs et al., 2015; Nuchuchua et al., 2017).

4.6 One pot loading and synthesis method

Drug encapsulation may be accomplished by including pharmaceuticals into the production phase of mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) (Dementeva et al., 2018). MSN is typically produced using a sol-gel technique using inert surfactant micelles as templating agents, which are then removed using extraction or calcination procedures (Andersson et al., 2004). After MSN synthesis, drug loading is carried out utilizing recognized procedures (Li et al., 2019; Maleki et al., 2017; Hillerström et al., 2014). However, these traditional procedures are often multistep and time-consuming, resulting in limited drug absorption and burst release, presenting issues for many formulations (Dementeva and Rudoy, 2016). The combination of MSN production and medication loading solves these challenges. Dementia et al. suggested employing micelles of myramistin (an antibacterial drug) as templates in the sol-gel fabrication of mesoporous silica carriers (Dementeva et al., 2016). This approach produces a high drug content (>1 g/g of SiO2) and is pH sensitive, with potential applications to additional amphiphilic medicines such as anticancer and anti-inflammatory compounds (Dementeva et al., 2018; Davis et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2013; Wan et al., 2016). Wan et al. successfully loaded two medicines, hydrophilic heparin, and hydrophobic ibuprofen, onto mesoporous silica using a one-pot synthesis technique. This approach, which uses Evaporation Induced Self Assembly (EISA) for in situ drug loading, has various benefits, including a considerable decrease in delivery system setup time from 74 to 10 h (Wang N. et al., 2019).

4.7 Covalent grafting

Covalent grafting has emerged as a well-established method for loading medicines onto mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) (Ahern et al., 2012; Fasiku et al., 2019; Giret et al., 2015). The functional groups on the outside of MSN walls allow for covalent interaction with medications, making it a more viable choice than adsorption with increased accuracy. This method provides more control, limiting undesired medication release before reaching the target location. Covalently connecting medications involves using common bonds such as amide, disulfide, ester, thiol, etc. The following drug release from these systems occurs by hydrolysis, enzymatic degradation, exchange processes, or redox reactions (Wong and Choi, 2015). This releasing process, known as linker cleavage, is well-addressed in the literature (Ding and Li, 2017; Mortera et al., 2009a). Notably, cysteine, sulfasalazine (a prodrug), and paclitaxel all exhibit this mechanism (Popat et al., 2012; Rosenholm et al., 2010; Uejo et al., 2013). Rosenholm et al. demonstrated the flexibility and effectiveness of this approach by covalently bonding methotrexate (MTX) to poly (ethyleneimine)-functionalized MSN (Yuan et al., 2013).

5 Solvent free method

These offer a high degree of medication loading and take less time. Furthermore, since the API/MSN ratio directly affects the drug concentration in the mesopore, it is simpler to forecast.

5.1 Melt method

The drug loading technique entails heating a drug-mesoporous silica combination over the active pharmaceutical ingredient’s (API) melting point (Kinnari et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2013). Potrzebowski et al. found that the thermal solvent-free melt approach is more successful in incorporating ibuprofen into MCM-41 than the incipient wetness method. The filling factor, calculated as the weight-to-weight ratio of ibuprofen to MCM-41, was about 60%. However, this strategy is only appropriate for thermally stable medications, since some research indicates a higher relationship between molten viscosity (Hampsey et al., 2004).

5.2 Microwave irradiation

A controlled heating procedure, in which the drug’s temperature is managed during loading via a feedback mechanism, is an alternate method for drug loading into silica particles. This approach efficiently stops medication deterioration (Waters et al., 2013). Waters et al., along with collaborators, used this approach to load fenofibrate into a variety of silica structures, including SBA-15 (Skorupska et al., 2014).

Microwave irradiation (300 MHz–300 GHz) is widely used for energy generation through heat production. When polar and charged molecules interact with microwaves, they align with the oscillating field, leading to rapid agitation, energy dissipation, and internal heating (Sun et al., 2016; Gupta and Eugene, 2011; Peng et al., 2012). Unlike conventional heating, which transfers heat from the surface inward, microwaves enable uniform internal heating, reducing reaction times, enhancing yields, and minimizing by-products (Jian et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Schanche, 2003; Kappe and Dallinger, 2009; Kappe, 2008).

This technology has been applied across diverse fields, including food processing (Sansano et al., 2018), water treatment (Wei et al., 2020), and chemical synthesis (Mirzaei and Neri, 2016). In synthesis, microwaves have facilitated the production of various materials, including metal oxides (Mirzaei and Neri, 2016), nanomaterials (Tsuji, 2017), MOFs (Khan and Jhung, 2015), polymers (Ebner et al., 2011), and graphene-based compounds (Li et al., 2017). While reviews exist on microwave-assisted synthesis of porous materials, a comprehensive study on silica materials synthesized via this method remains lacking (Cao et al., 2009; Park et al., 2004; Tompsett et al., 2006; Nithya et al., 2019). This review aims to fill that gap, focusing on mesoporous and non-porous silica synthesized through microwave techniques and their applications.

5.3 Microwave assisted

Microwave-assisted synthesis has revolutionized the fabrication of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) by offering unparalleled efficiency, precision, and sustainability. Unlike conventional thermal methods, which rely on surface-to-bulk heat transfer and often result in localized overheating and prolonged reaction times, microwave irradiation induces volumetric heating, ensuring rapid nucleation, uniform temperature distribution, and superior structural integrity. This technique drastically reduces synthesis duration—from hours to mere minutes—while enabling precise control over pore architecture, surface area, and particle morphology, thereby enhancing MSN functionality for targeted applications. Furthermore, its inherent ability to minimize by-product formation and eliminate excessive purification steps positions it as a highly efficient and environmentally sustainable alternative to traditional hydrothermal synthesis. The method has been extensively employed to engineer highly ordered mesoporous structures, such as SBA-15, SBA-16, and MCM-41, which play pivotal roles in catalysis, drug delivery, adsorption, and environmental remediation. By allowing precise modulation of irradiation power, surfactant concentration, and reaction kinetics, microwave-assisted synthesis elevates the potential of MSNs, offering a scalable, eco-conscious, and next-generation approach for advanced material development (Díaz de Greñu et al., 2020).

5.4 Co-milling

Milling is a flexible process for creating submicrometric particles (Willart and Descamps, 2008) and solid amorphization (Trzeciak et al., 2021b). Research has shown its efficacy, notably with organic molecules such as benzoic acid and 4-fluorobenzoic acid, which may be integrated into MCM-41 pores by planetary ball milling (Malfait et al., 2019). The loading process for guest compounds is determined by the substance-to-silica ratio, with maximum loading capabilities of more than 50% recorded at a 1:1 ratio. Furthermore, this approach permits guest molecules to be spread throughout many zones of MCM-41 (Malfait et al., 2019). Notably, Hedous et al. show that co-milling SBA-15 with ibuprofen increases drug loading into the matrix, with a filling degree of 40% by weight (Fu et al., 2010). Milling is a feasible alternative to solvent-based processes, providing simplicity, decreased time consumption, and scalability for industrial applications.

6 Drug release from MSNPs

Drug absorption is common during mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSNP) release, as shown in Figure 3. However, owing to limited control over mesopores, the delivery rate is of sustained type, reliant on drug dissolution. Aqueous-soluble medicines have less favorable release dynamics than hydrophobic pharmaceuticals since lower dissolution allows for better control over release kinetics as mentioned in Table 3. In Vitro, investigations have shown that interactions between particles and phospholipids (cell membranes) during endocytosis might improve the delivery of encapsulated hydrophobic medicines (Lu et al., 2007). To ensure regulated release, polymers are absorbed or covalently attached to particle surfaces (Fu et al., 2003). In closed conditions, polymer chains block apertures, preventing medication release. However, they may inflate or coil in response to particular stimuli, exposing pores and enabling medication administration. Another method for regulated release is to create chemical bonds across pores (Mal et al., 2003). Alternatively, bulky groups (such as Au) may be added to pore openings to serve as gatekeepers (Vivero-Escoto et al., 2010a). These bulky groups interact non-covalently, resulting in nanomachines such as nano valves and snap-tops (Coti et al., 2009). Various stimuli may be used to provide effective control, including chemical stimuli in which particles react to external chemical additions or internal changes (e.g., pH, enzymes) (Coti et al., 2009; Vivero-Escoto et al., 2010a; Manzano et al., 2009). Electrical stimuli via external electrodes or internal reducing conditions provides another avenue for regulation (Ambrogio et al., 2010; Mortera et al., 2009b), or light as a power source for release mechanisms (Mal et al., 2003; Angelos et al., 2007).

FIGURE 3

The schematic representation of mesoporous channels in nanoparticles facilitates enhanced drug diffusion and release kinetics.

TABLE 3

| Carrier | Drug | Release rate | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCM-41 (C12) MCM-41 (C16) SBA-15 |

Captopril | 45 wt% releases in 2 h while the total drug release was 16 h 47.47 wt% was released in 2 h nd total drug release was >30 h 60 wt% was released within 0.5 h while total drug was release in over 16 h |

Qu et al. (2006) |

| SBA-15 SBA-15 (C8) SBA-15 (C18) |

Erythromycin | 60% release was seen within 5 h And total drug release was between 14 h | Doadrio et al. (2006) |

| SBA-15 unmodified (PS0) SBA-15-NH2 by post synthesis (PS2) SBA-15-NH2 by one pot synthesis (OPS2) |

Ibuprofen | Complete release happened in 10 h Initial burst release was of 50% which was seen in 10 h Followed by 100% release seen within 3 days Total release was seen in 10 h |

Song et al. (2005) |

| MSN (grafting-loading approach) MSN (loading-grafting approach) |

Doxorubicin | 40% was released in 8 h And stagnant release was beyond 8 h 10% was released within first 24 h, while the sustained release was beyond 160 h |

Wang et al. (2016a) |

Drug release profiles for different carriers, highlighting variations in release rates and sustained drug delivery kinetics (Bush et al., 2007).

7 Targeting approaches

7.1 Passive targeting

Matsumura established the idea of passive targeting in 1986, which is based on tumour tissues’ leaky, discontinuous microvasculature and poor lymphatic drainage, resulting in increased permeability and retention (EPR) as shown in Figure 4C. Tumours exhibit fast angiogenesis to support proliferation (Matsumura and Maeda, 1986), resulting in vascular openings that allow nanocarriers to penetrate and accumulate. However, in order to accumulate efficiently, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) must avoid fast renal clearance and the reticuloendothelial system. This method has been widely used to improve tumour targeting using silica nanocarriers (Zhang et al., 2016). Functionalized MSNs, for example, that included magnetic nanoparticles in mesoporous shells and surface changes, were able to successfully reach tumour locations in mice via passive targeting. These MSNs have also been used to produce multimodal imaging probes for MRI applications (Lee et al., 2011).

FIGURE 4

Schematic representation of nanoparticle (NP)-based drug delivery strategies. (A) Various types of nanoparticles, including liposomes, micelles, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), dendrimers, and gold nanoparticles, serve as versatile carriers for therapeutic agents. (B) Functionalization with ligands such as antibodies, hyaluronic acid, peptides, and folic acid enhances targeting specificity. (C) Passive targeting exploits the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, wherein nanoparticles accumulate preferentially in tumour tissues due to defective vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage. (D) Active targeting employs ligand-functionalized nanoparticles that bind to specific receptors (e.g., GPCRs) on cancer cells, facilitating cellular internalization and endosomal uptake, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy (Created with BioRender.com).

Nanoparticle size significantly affects MSN circulation, distribution, tissue accumulation, and cellular uptake. The optimal size for biological use is 10–300 nm, with 100–200 nm particles achieving the highest tumour accumulation via the EPR effect (Petros and DeSimone, 2010; Maeda et al., 2000). Particles of 80 nm show longer residence times, while those larger than 400 nm have poor tumour penetration. Spherical MSNs (80–360 nm) tend to accumulate in the liver and spleen (He Q. et al., 2011). Cellular uptake studies show that 50 nm particles provide the best internalization, though smaller particles may agglomerate and hinder endocytosis (Chithrani et al., 2006).

Nanoparticle shape also influences passive targeting. Spherical MSNs are preferred due to easier fabrication and faster internalization (Gao et al., 2005). Studies show that larger aspect ratios (ARs) enhance cellular uptake and accumulation, with rod-shaped MSNs (AR 2.1–2.5) showing improved tissue penetration (Trewyn et al., 2008). Shorter rods are cleared quickly from the liver, while longer rods accumulate in the spleen. Determining the ideal MSN shape remains challenging due to mixed findings (Huang et al., 2010a; Meng et al., 2011a; Shao et al., 2017).

MSN surface properties affect cell internalization, biodistribution, and circulation (Nel et al., 2009). Negatively charged silanol groups can bind to RBCs, causing hemolysis and reduced targeting, but surface functionalization can mitigate this (Slowing et al., 2009; Teng et al., 2014). PEGylation (with 10,000–20,000 g/mol PEG) reduces protein adsorption and hemolysis (Ke et al., 2017; Cauda et al., 2010; He Q. et al., 2010) while enhancing internalization, though repeated injections may trigger faster clearance due to anti-PEG antibodies. Zwitterionic copolymers and lipid coatings also improve circulation stability (Rosenbrand et al., 2018; Ishida et al., 2003).

Surface charge impacts cell uptake, with positively charged nanocarriers showing better internalization than neutral or negative ones (Yuan et al., 2012). Functionalization with contrast agents (e.g., indocyanine green) or NH2 and PO3 groups enhances drug loading, solubility, and imaging performance (Chaudhary et al., 2019). NH2-modified MSNs have shown improved solubility for lymphoma drugs and enhanced drug delivery under hypoxic conditions in prostate cancer cells (Meka et al., 2018).

7.2 Active targeting

Active targeting takes use of the unique interactions between cancer cells and drug-loaded MSNs, demanding surface functionalization with specialized ligands. These ligands, which range from macromolecules and antibodies to nucleic acids, vitamins, sugars, and peptides, allow MSNs to precisely attach to cancer cells by taking advantage of ligand affinity for overexpressed receptors on tumour surfaces (Peer et al., 2007). Active targeting techniques are divided into three categories: tumour cell targeting, vascular targeting, and subcellular organelle targeting, with each providing site-specific delivery to improve treatment effectiveness. Figure 4D describes MSNPs are functionalized with particular ligands that bind to cancer cell-overexpressed receptors (e.g., GPCRs). After binding, MSNPs are internalized into cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, delivering their payload to intracellular compartments such as endosomes. This dual targeting technique improves the delivery efficiency and therapeutic potential of MSNPs in cancer treatments.

8 In-vivo biodistribution of SNPs

The biodistribution of silica nanoparticles (SNPs) is primarily governed by their physicochemical properties such as size, shape, charge, porosity, and surface functionalization, all of which affect toxicity (Wei et al., 2018; Jasinski et al., 2018). Understanding these parameters is essential for developing successful SNP-based therapeutics. Smaller SNPs (<6 nm) are cleared renally with minimal toxicity, while larger particles (>90 nm) may still appear in urine due to unknown mechanisms (Huang et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2012). Hepatobiliary clearance is influenced by particle size and surface modifications like PEGylation, which prolongs circulation time, while unshielded cationic particles clear rapidly through the liver (Souris et al., 2010). Aspect ratio also plays a role, with elongated particles exhibiting slower renal clearance than spherical ones, and smaller aspect ratios increasing hepatobiliary clearance rates (Huang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016).

The formation of a protein corona mitigates toxicity by increasing surface area and facilitating clearance (Croissant et al., 2018). Dissolution kinetics vary with silica condensation, network connectivity, and surface functionalization, with interrupted networks degrading faster in basic conditions (Möller and Bein, 2019). Ultimately, SNP clearance via renal or hepatobiliary pathways is closely tied to their degradation rate and physicochemical traits.

9 Mechanism of SNPs- induced toxicity

Preclinical safety evaluation of SNPs necessitates consideration of dose, administration route, and animal models (choice, gender, age) etc. SNPs initially interact with endothelial cells, necessitating toxicity studies in these cells due to their critical role in vascular transport (Cao et al., 2021). Toxicity pathways include mitochondrial ROS generation, MAPK and NF-κB upregulation, and inflammasome activation as shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Toxicity type | Route of administration/Preclinical model | Particle sizes with dose | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | Inhalation, BALB/c mice | 12 nm 5,10,20 mg/kg |

Increased production of NLRP3 and IL-1B was upregulated by TXNIP expression | Lee et al. (2020) |

| Hepatic | 40 Sprague Dawley male rats (Intratracheal instillation) |

1.8, 5.4, 16.2 mg/kg | Elevation of triglyceride, ALT, AST | Sun et al. (2021a) |

| Hepatic, Spleen | 18 Sprague Dawley male and female rats intravenous administration |

13–45 nm 20 mg/kg for 1-day and repeated 5- day dose |

Enlarged spleen accompanied by granulomas exhibiting dense inflammatory infiltrates | Tassinari et al. (2021) |

| Endothelial | In vitro | 20 nm 100 nm |

Reduced viability and compromised plasma membrane integrity in HUVECs | Wang et al. (2020) |

| Cardiac | Intraperitoneal Intratracheal Intratracheal Intravenous C57BL/6 J mice |

50 nm 25,50,100,200 mg/kg 63 nm 2 mg/kg 95 nm 100 nm (4, 6,8, 10 mg/kg) 20 nm (4, 10, 20, 30 mg/kg) |

ROS generation Elevated ROS generation and upregulation of cardiac injury-associated proteins Enhanced expression of CD36 Enhanced LDH levels Fatal tachyarrhythmias and severe bradyarrhythmia |

Hozayen et al. (2019)

Yang et al. (2018) Ma et al. (2020) Liu et al. (2020a) |

| Pulmonary | Intravenous Mice, intratracheal Intratracheal |

63 nm, 20 mg/kg 10–20 nm SNP 10, 50, and 200 mg/kg 50nm, 3 μm 400 μg/body or 30 μg/body |

Upregulation of JAKSTAT2/STAT3 signaling accompanied by elevated TNF-alpha, IL-1B, and IL-6 levels Increased ROS production, ERK activation, and ZO1 mRNA downregulation ROS, and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) |

Yu et al. (2019)

Liu et al. (2020b) Inoue et al. (2021) |

| Neurotoxicity | Intranasal | 80, 100 nm, 3 mg/mL | Elevated TNF-alpha, NF-kB, and MCP-1 levels, coupled with a decline in antioxidant defense mechanisms | Parveen et al. (2017) |

| Genotoxicity | Intratracheal | 50,100, 250 nm (Cation) 100 nm (anion) |

Increased ROS and oxidative stress alongside NF-kB and IL-1B upregulation | Chou et al. (2017) |

The summarizes SNP toxicity studies, detailing administration routes, dosages, mechanisms, and adverse effects.

10 Synthesis parameter impact on physicochmical properties of Msnps

10.1 Pore size and shape

The amount and kind of medicine that may be loaded, as well as the drug’s rate of dissolution, are determined by the pore’s size and shape (Bush et al., 2007). Therefore, in order to avoid the medication releasing too soon, the proper pore size must be employed (Varga et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015b). The MSN’s meso-scaled channels aid in the storage of non-crystalline medications (Khushalani et al., 1995). They must be investigated in order to regulate the pore size, kind, concentration of templates, and chain length (Maleki et al., 2017; Jana et al., 2004). The pore size rises from 1.6 nm to 4.2 nm with an increase in chain length from C8 to C22 in tetra ammonium salt, according to research by Jana et al. (Widenmeyer and Anwander, 2002).

Additional research has demonstrated that it is feasible to modify the pore size by up to 4.1 nm, which can change the surfactant chain length (Zhang et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2015). In addition to these variables, pore size is further influenced by catalyst concentration, silica precursor content, and experimental conditions (time and temperature) (Argyo et al., 2014). Mesopores typically have surface areas of 1,000 m2/g, pore volumes of 1–2 cm2/g, and pore diameters of less than 15 nm (NŽK, 2015; Wu et al., 2013).

10.2 Surface charge and particle characteristics

The size, shape, and surface charge of particles are important in determining in vitro and in vivo drug delivery as MSN with less than 1 µm diameter are much preferred due to their ability for faster mass transport and excellent dispersibility (Khushalani et al., 1995; Jana et al., 2004; Chiang et al., 2011). The pharmacokinetics of MSN are affected by changes in surface charge (Huang et al., 2010b). The cellular interaction, distribution, and elimination are all controlled by the particle size (Varache et al., 2015). The size of the particles can be changed with changes in pH (Yu et al., 2012), reaction temperature (Yokoi et al., 2010), stirring rate (Yamada et al., 2013), type of silica precursor used (Ma et al., 2013), and additives (He et al., 2009) as listed in Table 5. Chiang et al. and Wu et al. showed an increase in the hydrolysis rate and polymerization of silica precursor with increased reaction temperature, leading to larger particle size (Chiang et al., 2011; Yokoi et al., 2010; Wu and Yamauchi, 2012; Ma et al., 2012; Lv et al., 2016). Lv et al. (Sarkar et al., 2016), who worked on TEA, described the effects of base concentration (TEA), reaction temperature, and stirring rates on the size of the particles. It was seen that an increase in temperature (55°C) led to an increase in particle size from 21 nm to 38nm, while the particle size decreased from 51nm to 41 nm when base concentration was increased (0.18g TEA). Now, changing the stirring rates from 100 to 700rpm drastically reduced the particle size from 110nm to 38 nm. However, interestingly, upon further increasing the stirring rate from 700rpm to 1000rpm, there was no further change in size. TEM images given below show the effect of stirring rate, base concentration, and reaction temperature on particle size.

TABLE 5

| Stimuli | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|

| External stimuli | ||

| Temperature | • PNIPAM coated MSNs • Dual responsive MSNs (Magnetic field leads to increase in temperature) |

Chen et al. (2011a)

Fuller et al. (2019) |

| Magnetic field | • Superparamagnetic iron core embedded within mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) • Magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) functionalized with cyclic amino acid ligands • Magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) capped with quantum dots |

Baeza et al. (2012), Guisasola et al. (2015), Reichenbach et al. (1992), Zhang et al. (2019) Li et al. (2013a), von et al. (2008), Jiang et al. (2017) Yao et al. (2017) |

| Light | • Near-Infrared (NIR) region • MSNs functionalized with gold nanoparticle caps • Activated through photosensitizer agent • Dual-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) sensitive to both near-infrared (NIR) light and pH, functionalized with perylene-modified poly (dimethylaminoethyl methacrylates) |

Li et al. (2013b), Li et al. (2014), Sun et al. (2018), Zhang et al. (2015), Yang et al. (2019), Liu et al. (2013) Liu et al. (2018), Vivero-Escoto et al. (2009) Yang et al. (2016), Liu et al. (2015a), Gong et al. (2015), Liu et al. (2014) Wang et al. (2016b) |

| Ultrasound | • MSNs were fabricated through surface grafting of 2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl methacrylate co-polymerized with tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate | Paris et al. (2015) |

| Internal stimuli | ||

| pH | • pH-responsive mesoporous silica spheres engineered via surface coating with poly (methacrylic acid-co-vinyl triethoxysilane) (PMV) • Mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) pores functionalized with hydrazine-linked pH-sensitive cleavable linkers • Poly (acrylic acid) chains covalently grafted onto the surface of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) • MSN surfaces capped with gold nanoparticles via acid-degradable acetal linkers • Zinc oxide (ZnO) caps immobilized on mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), enabling release through acidic cleavage |

Gao et al. (2009)

Lee et al. (2010) Martínez-Carmona et al. (2018) Liu et al. (2010) Muhammad et al. (2011) |

| Enzyme | • Hydrolyzed starch conjugated to the surface of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) • Lactose-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) capped for controlled release • Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) anchored to avidin via MMP9 linkers, enabling targeted delivery to MMP9-overexpressing cancer sites • Cathepsin B activity regulated through mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) interactions |

Bernardos et al. (2010)

Bernardos et al. (2009) van Rijt et al. (2015) Cheng et al. (2015) |

| Redox | • Disassembly via disulfide (S-S) bond cleavage | Wang et al. (2015c), Zhao et al. (2014), Zhang et al. (2012), Ma et al. (2014) |

| Small molecules | • Concentration of Glucose • Anionic small silica nanoparticles designed for oral insulin delivery • Competitive binding dynamics in the presence of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) |

Traitel et al. (2000), Zou et al. (2016) Lamson et al. (2020) Zheng et al. (2015) |

The summary highlights the stimuli utilized for drug delivery via MSNs.

11 Applications

Figure 5 presents diverse applications of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) across various fields.

FIGURE 5

MSNs have diverse applications across multiple fields, contributing to advancements in technology and science.

11.1 Increasing bioavailability

Lesser density porous carrier such as porous silicon dioxide (Sylysia), polypropylene foam powder (Accurel), porous calcium silicate (Florite), magnesium aluminium metasilicate (Neuslin) and porous ceramic with open or closed pore structure that provides large surface area and can be used for improving the dissolution and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs like meloxicam, aspirin and indomethacin.

Randy Mellaerts et al. proved that ordered mesoporous silica (OMS) is a promising carrier for achieving enhanced oral bioavailability of drugs with poor aqueous solubility. it presented the effects of spherical MSNs as an oral availability of the model drug TEL and examined their cellular uptake and cytotoxicity (Lu et al., 2010).

11.2 Anti-cancer drug delivery

The delivery of cisplatin can be controlled, allowing for sustained and targeted delivery. The pore structure of MSNPs enables tunable release kinetics, which can be tailored to match the desired therapeutic profile, thus providing a sustained release of potentially toxic Cisplatin molecules along with a decrease in nonspecific release due to enzymatic hydrolysis. The MSNPs can be loaded with multiple drugs, allowing for combination therapy to target different paths involved in cancer progression. Numerous studies of in vivo toxicity, intake distribution, and clearance were done in animal models (He QJ. et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2011b). Where MSNPs of 100 nm (MC-41 type) gave good biocompatibility in mice for a longer term (He QJ. et al., 2011). MSNPs also deliver Anti-cancer drugs into human xenografts in mice and decrease tumour growth (He QJ. et al., 2011). In a study, modified MSNP using PEI-PEG coating delivered DOX on a KB-31 Xenografted tumour model (Lercher et al., 2006). Table 6 provides an overview of MSNs formulations used in Cancer.

TABLE 6

| Therapy | Formulation of MSN | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | MSNs were coated with chitosan, functionalized with carbon dots, and targeted with an anti-MUC1 aptamer | Strong and selective anticancer activities have been shown by nanoparticles, presenting possibilities for targeted cancer therapy and fluorescence imaging | Kajani et al. (2023) |

| Skin Cancer (Melanoma) | MSNs were also loaded with a lysosomal destabilization mediator (chloroquine; CQ) and an anticancer medication (cisplatin; CP) after being functionalized with a histidine-tagged targeting peptide (B3int). Cu2+ was used in chelation to close the MSNs’ pores | These nanoparticles release their loaded pharmaceuticals (cisplatin and chloroquine) in reaction to the acidic pH of lysosomes/endosomes. The peptide’s Cu2+ ions in this environment function as a catalyst to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which injure tumour cells. Tumour volume has been significantly reduced as a consequence of this approach, which has shown strong anticancer efficacy both in vitro and in vivo | Zhang et al. (2022) |

Overview of MSNs in Cancer Treatment with Supporting Literature.

Because MSNPs are a flexible carrier, medications with different characters may be loaded. They have a strong propensity to accumulate within the tumour site because of the enhanced EPR effect (Lercher et al., 2006). Targeting and choosing overexpressed receptors in tumour areas and ligands for those receptors that are conjugated onto the MSN surface allows the medicine to be optimised to reach the precise place. Folic acid (FA) is one such ligand that raises folate levels. In order to provide 5-aminolevulinic acid for photodynamic therapy against B16F 10 skin cancer, Ma et al. (Kleitz et al., 2003) conjugated folic onto the surface of the HMSNs. Hyaluronic acid, or HA, is another well-researched ligand for CD44 receptors. Zhang et al. (Jammaer et al., 2009) reported that DOX-MSN had both receptor-mediated and enzyme-responsive properties.

HA-MSN was synthesised by Gary Bobo et al. (Vialpando et al., 2011) for photodynamic treatment against a colon cancer cell line. The investigation, which used HCT-116 as a model, demonstrated how HA-MSN’s targeting of the CD44 receptor boosted its efficiency over ordinary MSN.

11.3 Biosensor

The biosensor in biosensing is composed of an embedded receptor or indicator and a functionalized MSN matrix (Gao et al., 2020). The idea underlying sensing is to identify variations in the optical or electrical signals of different analytes, which are distinguished by their sensitivity to variations in optical detection techniques as RAMAN and UV spectroscopy. This makes it possible to identify several biological targets, including bacteria, viruses, carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins, and glutathione (Gao et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2017; Huang F. et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021; Tuna et al., 2022; Singh RK. et al., 2017). The MSN matrix increases the receptor’s or indicator’s physiological stability, which raises sensitivity and detection rates. Furthermore, MSN’s structured mesoporous silica structure allows for the creation of particular reaction chambers or promotes interfacial interactions (Gao et al., 2020). Research reports that aptamer-gated aminated MSNs were used for bacterial quantification (Zhu et al., 2021).

11.4 Bioimaging

NP-based contrast agents have gained importance in the realm of bioimaging, which uses bioimaging for diagnostic reasons (Liu et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2022; Al-Hetty et al., 2023). It is possible to overcome stability and low water solubility difficulties with MSN by adding contrast ants. Targeting ligands applied to the surface of MSN increase the concentration of contrast compounds at specific places (Yu et al., 2018; Sun B. et al., 2021). In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Fe, Mn, and Gd-based nanoprobes perform better in contrast because of the porosity nature of MSNPs, which enables water molecules to penetrate the matrix (Yu et al., 2018). MSN enhances photo-bleach resistance and boosts quantum yields for fluorescence imaging (FL) by preventing dye self-aggregation or self-quenching (Sun B. et al., 2021). For PET imaging, radioisotopes like Cu and F must be used to mark molecular probes. When these radioisotopes are added, the MSN matrix lengthens their half-life (Shaffer et al., 2016; Rojas et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2015).

Similar to this, the MSN matrix protects contrast agents in photoacoustic imaging (PA), such as polydopamine (PDA) NP (Cai et al., 2019), Cy754 (Liu Z. et al., 2015), and ICG (Ferrauto et al., 2019) to provide the necessary PA signals. Moreover, multimodal imaging (Grzelak et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2021), computed tomography (CT) imaging (Chen et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2021), and ultrasound imaging (Ho et al., 2020; Kempen et al., 2015) also make substantial use of MSNPs.

11.5 Theranostics and gene delivery

MSNPs can also be used to transport DNA, RNA, and Nucleic acids in the case of gene therapy as they enable these nucleic acids to bind to the outer surface along with drugs entrapped in the pores. An example of such a method is surface grafting (G2) PAMAM dendrimers (Radu et al., 2004).

MSNPs have also been identified for the use of theranostics applications because of its known biocompatibility (Vivero-Escoto et al., 2010b; Slowing et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2011b; Chen et al., 2011c; Bulatović et al., 2014; Kaluđerović et al., 2010a; García-Peñas et al., 2012; Kaluđerović et al., 2010b; Pérez-Quintanilla et al., 2009; Ceballos-Torres et al., 2014) dual drug targeting. Through functionalization [inorganic structures like Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (Zhu et al., 2010), Gold nanocrystal (Chen et al., 2010), Quantum dots (Kim et al., 2006), etc. Or chemically grafting function groups like PEG (Lu et al., 2010), fluorescent molecules (He QJ. et al., 2010), etc. Of MSN surface, biomedical imaging diagnostic, and therapy for lesion sites for cancer can be produced (Wu H. et al., 2011).

11.6 Agricultural application

Due of its connections to several neurological conditions, cancers, respiratory disorders, and irregularities related to hormones and reproduction, chemical pesticide usage has sparked worries about public health. The need to produce ecologically friendly pesticides has increased as a result of this problem. Food products that have been stored are mostly stagnant due to the actions of fungus, insects, and rodents under different storage conditions. Crop losses resulting from diseases and insects can range from 5% to 10% in temperate zones and from 50% to 100% in tropical areas, according to estimates (Torney et al., 2007). Honeycomb mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) with 3-nm pores were created for the first time by Torney, Francois, et al. These MSNs carry genetic material and medications into isolated plant cells and whole leaves by acting as nanocarriers.

Genes and chemical inducers are packed inside the MSNs, and gold nanoparticles cover the ends to stop molecular leaching. Developments in MSNs, such pore enlargement and multi-functionalization, may enable the delivery of drugs, nucleotides, and proteins to specific destinations in plant biotechnology. Pre-treating maize seeds with silica nanoparticles increases the production of organic compounds in the maize seed wall, hence improving resistance to fungal attacks (Suriyaprabha et al., 2012). Additionally, compared to alternative silica-based sources, pre-treated seeds exhibit higher germination rates and improved absorption capacity, resulting in increased nutritional content (Siddiqui and Al-Whaibi, 2014). The use of silica nanoparticles was found to enhance mean germination durations, seed germination indices, and germination rates by Siddiqui and Al-Whaibi (Shi et al., 2013). When 8 g/L of silica nanoparticles were used, germination rates rose by 22.16%. Plants frequently struggle to survive in stressful environments, including those with rising salinities. In order to live, a gene encoding a particular protein that protects against salt has to be introduced.

11.7 Environmental application

Silica nanoparticles aid in better oil recovery by reducing the leakage of brine, heavy metals, and radioactive substances into water. In the case of a leak, the impacted water is channeled underground, causing water flooding, which aids oil recovery. However, the usefulness of nanoparticles in high salinity water, where oil extraction takes place, may be hindered, requiring changes to their functioning to assist the extraction process. Experimental experiments have established the efficiency of H+ protection offered to silica nanoparticles in saltwater, with the addition of HCl acting as a shielding mechanism (Youssif et al., 2018). Surface-treated nanoparticles have reversible adsorption properties, enabling them to travel through oil-rich rocks. Additionally, the application of viscosity enhancers eliminates transportation problems. The behavior of silica nanoparticles in sandstone, dolomite, and limestone was investigated (Rognmo et al., 2018). For example, commercial silica nanoparticles of 20 nm in size were employed as the reservoir in sandstone cores. The optimal oil recovery was obtained at a silica nanoparticle concentration of 0.1 weight % (Yousefvand and Jafari, 2015). Silica nanoparticles generate a consistent CO2 foam from oil and stay stable throughout displacement, resulting in greater oil recovery and a lower carbon footprint owing to CO2 (Khan et al., 2014). Incorporating nanoparticles into polymers has also showed potential for alleviating floods and increasing oil recovery. Nano-silicates, for example, may boost the recovery factor by up to 10% owing to the viscosity of the injected fluid (Qu et al., 2006). These discoveries illustrate nanotechnology’s great potential to improve oil recovery techniques.

11.8 Heavy metal removal

The contamination of water with heavy metal ions poses serious health and environmental risks, necessitating efficient removal strategies. Industries such as food processing, leather, and textile dyeing release toxic metal ions beyond permissible limits, highlighting the need for cost-effective adsorbents. Mesoporous silica has gained prominence for removing heavy metal ions like chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), copper (Cu), sodium (Na), and cobalt (Co.), as well as organic pollutants from industrial effluents (Jadhav et al., 2016; Savage and Diallo, 2005).

Various techniques, including electrochemical treatment, photodegradation, and chemical coagulation, have been explored for metal ion removal (Ibrahim et al., 2010). Among them, MSN-based adsorption stands out for its efficiency, ease of recovery, and reusability (Jadhav et al., 2018; Jadhav et al., 2019). Research interest in MSN applications for heavy metal removal has significantly increased over the past decade (Karbassian and Ghrib, 2018).

A key advancement is the functionalization of MCM-41-type mesoporous silica with organic groups and polymers, enhancing adsorption efficiency for chromium ions. This review compiles recent MSN-based metal ion removal strategies, summarizing newly synthesized materials and their adsorption capacities. The insights provided will aid future research and development in MSN-based water purification.

11.9 Carbon capture

Addressing climate change requires more than atmospheric CO2 capture; effective stabilization demands advanced techniques like carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture and utilization (CCU) (D'Alessandro et al., 2010; Aresta et al., 2014). CCS mitigates emissions from industrial sources by capturing and storing CO2 under high pressure (Tomé and Marrucho, 2016; Tapia et al., 2018). Despite its industrial adoption, high costs and technical challenges limit its commercial viability (Bui et al., 2018). The U.S. leads in CCS deployment (7–8.4 MtCO2/year), followed by China (0.4–2 MtCO2) and Europe (0.7–1 MtCO2) (Wee, 2013; Koh et al., 2019). CCS employs chemical, geological, marine, and terrestrial sequestration but does not convert CO2 into usable products, risking its eventual release. Adsorbent efficiency depends on combustion stages, with meso/macroporous materials suited for pre-combustion and microporous sorbents for post-combustion (Singh G. et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2012).

Conversely, CCU offers a sustainable alternative by converting CO2 into fuels and chemicals, reducing greenhouse gas impact (Kurisingal et al., 2019a; Kurisingal et al., 2019b; Ghiat and Al-Ansari, 2021). More efficient than CCS long-term (Porosoff et al., 2016), CCU repurposes CO2 into hydrocarbons, methanol, and formic acid, minimizing fossil fuel reliance (Wang X. et al., 2019; Calvinho et al., 2018; Branco et al., 2016; Donphai et al., 2016; Wang WH. et al., 2015; Han et al., 2019; Fujiwara et al., 2015; Owen et al., 2016). Conversion methods include hydrogenation, cycloaddition, photochemical reduction, oxidative dehydrogenation, and electrochemical reduction (Dai et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2020; Jeyalakshmi et al., 2013; Kiatphuengporn et al., 2016). Despite CO2’s stability requiring high energy input, industries use ∼3,600 million tons annually. Future policies, like carbon taxation, could enhance CO2 utilization (Parvanian et al., 2022), necessitating novel conversion technologies.

Heterogeneous catalysts such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), transition-metal complexes, porous organic polymers, covalent organic frameworks (COFs), zeolites, porous carbon, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have shown superior efficiency in CO2 utilization (Mohan et al., 2020a; Mohan et al., 2020b; Gui et al., 2020; Kurisingal et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2019). MSNs, with tunable silanol groups, high surface areas (∼2,370 m2 g-1), and large pore volumes (∼1.4 cm3 g-1), enable enhanced metal dispersion, crucial for catalysis (Mohan et al., 2021a; Mohan et al., 2021b; Cashin et al., 2018).

12 Clinical studies in MSNs

Clinical trials involving the potential use of Mesoporous silica are being done from 2007. As of now clinical trials have showed safety and good tolerability of silica in humans. MSNs oral delivery was established in 2014 for the purpose of enhancing pharmacokinetics profile of poor water-soluble drugs (Qu et al., 2006).

Silica nanoparticles with lipid hybrid formulation was loaded with Ibuprofen (Lipo-ceramic IBU). Randomised, double blind, single dose oral study of 20 mg Ibuprofen was practiced on 16 healthy male volunteers., and the bioavailability of lipo-ceramic-IBU was found to be 1.95 times greater than commercial nurofen tablet (Tan et al., 2014).

Similarly in another clinical trial conducted in 2016, 12 subjects were selected and resulted in an increased bioavailability of ordered MSNs oral dose compared to Lipanthyl commercially (Bukara et al., 2016).

Due to positive clinical outcomes of silica based nanocarriers the safety, pharmacokinetics and metabolic profile of Cornell dots or C dots (Hybrid core shell silica nanoparticles) of diameter 6 nm functionalized with 124I targeting peptide cyclo- (Arg-Gly-Tyr) and cy5 (124I-cRGDY-PEG-C dots) was first conducted in humans using PET imaging and clinical tracer in 2014 at clinical trials (NCT01266096) (Phillips et al., 2014b). Good safety and reproducible PK signatures of C dots with whole body clearance half time of 13–21 h s was witnessed after iv injection which is shorter than 111In labelled liposomes and 131I labelled humanised monoclonal antibody A33. These results led to the use of Nanoparticles in human cancer (Phillips et al., 2014b).

In another study, 8 nm shell silica nanoparticles were encapsulated with cy 5.5 and connected with cRGDY on the surface, (cRGDY-PEG-cy 5.5- Nanoparticles)., nodes detection of head and neck melanoma at phase one/2 clinical trials (Zanoni et al., 2021) and phase two trials are expected to finish in 2024 (NCT 02106598).

Another two clinical trials were also conducted on C dots. In 2018, the 89Zr-DFo-cRGDY-PEG-Cy5-C dot traces were used in both surgical and non-surgical patients for PET-CT imaging of malignant brain tumour in phase one clinical trials (NCT03465618). In 2023, distribution and removal profiles of these particles were characterized.

In 2019, 64cu-NOTA-PSMA-PEG-Cy 5.5-C′ dot tracer was used in another human phase one clinical trial for prostate cancer by PET and MRI imaging (NCT04167969) (Xu et al., 2023).

13 Patents in the field of MSNPs

| Patent Number | Year | Inventor | Type of drug | Disease | Title | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US20160008283A1 | 2016 | Nel et al. | Gemcytabine | Pancreatic cancer | Lipid bilayer covering MSNs suggests that anticancer drugs can be loaded onto them with great efficiency | Nel et al. (2016) |

| US20140079774A1 | 2014 | Brinker et al. | Anticancer agent | Liver cancer | Lipid bilayers with NP-maintained pores for focused administration | Brinker et al. (2017) |

| US8926994B2 | 2015 | Serda et al. | TGF-β inhibitor LY364947 | Breast cancer | Adjuvant for antitumour immunity and mesoporous silicon for the synthesis of tumour antigens | Serda et al. (2015) |

14 Future directions

The rapid advancements in nanotechnology, particularly in the development of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), have demonstrated their significant potential in therapeutic and diagnostic applications. The recent clinical approvals of lipid-nanoparticle-based mRNA vaccines have reinforced the promise of nanomaterials in medicine, yet the clinical translation of nanoparticles, including silica-based platforms, remains largely limited. Despite preclinical evidence supporting their efficacy, only a handful of MSN formulations have progressed to human trials. Notably, plasmonic resonance therapy using ferromagnetic core-shell silica nanoparticles has exhibited superior outcomes in coronary atherosclerosis treatment compared to conventional interventions (NCT01270139) (Kharlamov et al., 2017). Furthermore, AuroLase® therapy utilizing gold-shell silica-core nanoparticles has achieved remarkable tumour ablation efficacy in prostate and head and neck cancers (NCT04240639, NCT02680535, NCT04656678, NCT00848042) with minimal systemic toxicity (Rastinehad et al., 2019). Similarly, Cornell dots, a class of ultra-small silica nanoparticles, have demonstrated their safety and efficacy in cancer imaging and sentinel lymph node detection in clinical settings (NCT01266096, NCT02106598) (Phillips et al., 2014c; Zanoni et al., 2021). These pioneering studies underscore the clinical viability of MSNs, yet their widespread adoption necessitates further advancements in overcoming biological barriers and addressing toxicity concerns.

The primary impediments to the clinical translation of MSNs involve their biocompatibility, biodistribution, and potential toxicity. The physicochemical properties, including size, surface functionalization, porosity, and degradation kinetics, critically influence their pharmacokinetic behaviour and toxicity profiles. Reports of silica nanoparticle-induced pathologic lesions, coagulation disturbances, and inflammatory responses in vital organs such as the liver, heart, lungs, and spleen highlight the necessity of optimizing these parameters to mitigate adverse effects. Strategies such as surface functionalization with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and folic acid have demonstrated promise in minimizing systemic toxicity by reducing off-target accumulation. Additionally, the enhanced biodegradability of mesoporous silica compared to its nonporous counterparts suggests a favourable safety profile, yet inconsistencies in in vivo toxicity studies necessitate standardized evaluation methodologies. The divergent findings on MSN toxicity stem from variations in nanoparticle physicochemical properties, dosing regimens, and administration routes, underscoring the need for more comprehensive toxicity assessments that closely mimic clinical conditions (Hargrove et al., 2020; Di Pasqua et al., 2013).

Although MSNs hold immense promise for targeted drug delivery, the transition from preclinical models to clinical applications remains a formidable challenge. The majority of existing studies are confined to in vitro investigations, which do not fully recapitulate the complexities of in vivo biological environments. Limited tissue penetration and the lack of robust data on MSN clearance mechanisms further complicate their clinical translation. Addressing these gaps requires extensive in vivo studies to elucidate the biodistribution, accumulation, and elimination pathways of MSNs, ensuring their long-term safety and efficacy. Moreover, the development of more sophisticated MSN-based drug delivery systems, integrating stimuli-responsive and targeted therapeutic strategies, represents a crucial avenue for enhancing clinical applicability.

In conclusion, mesoporous silica nanoparticles offer a transformative approach to cancer therapy and drug delivery, yet significant challenges remain their clinical adoption. This review underscores the recent advancements in MSN functionalization, stimuli-triggered drug release, and targeted delivery strategies. While the preclinical landscape is promising, prospective investigations focusing on biocompatibility, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity mitigation are imperative to facilitate the transition of MSN-based nanocarriers from laboratory research to clinical practice. Future efforts should prioritize refining MSN designs to enhance their therapeutic efficacy while ensuring safety, ultimately paving the way for their integration into mainstream medical applications.

15 Conclusion

The limitations of conventional therapies underscore an urgent need for next-generation treatment strategies with superior efficacy and precision. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have emerged as a groundbreaking platform for drug delivery, offering tunable physicochemical properties—such as pore architecture, morphology, and surface functionalization—that enable precise control over drug loading and release. This review comprehensively examines the advancements in MSN-based drug carriers, highlighting their potential across diverse biomedical applications, including targeted cancer therapy, gene delivery, theranostics, and environmental remediation. The intricate relationship between MSN design and therapeutic performance underscores the necessity of tailored nanostructures for specific medical applications.

Despite significant progress in optimizing MSNs for controlled drug delivery, their clinical translation remains a formidable challenge. While extensive in vitro studies have demonstrated promising results, the transition to in vivo applications is hindered by unresolved issues such as tissue penetration, systemic distribution, and long-term biocompatibility. Current research predominantly relies on in vitro models that fail to accurately replicate the complexities of the human physiological environment. Moreover, a critical gap in the existing literature is the limited discussion on the biodistribution, metabolism, and clearance pathways of MSNs, raising concerns about their potential accumulation and toxicity in biological systems. Addressing these uncertainties necessitates extensive preclinical in vivo studies to elucidate MSN processing, retention, and elimination within living organisms.

Future research should prioritize refining MSN synthesis, enhancing biocompatibility, and establishing scalable, reproducible manufacturing techniques to facilitate clinical adoption. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaborations integrating cutting-edge nanotechnology, advanced imaging modalities, and pharmacokinetic modeling will be pivotal in overcoming translational barriers. By addressing these challenges, MSNs hold the potential to revolutionize drug delivery, optimize therapeutic efficacy, minimize adverse effects, and advance the era of precision medicine.

Statements

Author contributions

RF: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. PK: Writing–review and editing. KK: Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deep gratitude to my guide, Kalpana, for her valuable guidance and support throughout this research. Her expertise and encouragement have been instrumental in the completion of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1