- 1Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

- 2Department of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, City University of New York Medical School, New York, NY, USA

- 3Istituto Di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Centro “Bonino Pulejo”, Messina, Italy

- 4Department of Biomedical Science and Morphological and Functional Images, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

Objective: Investigation of spatial and temporal cognitive processing in idiopathic cervical dystonia (CD) by means of specific tasks based on perception in time and space domains of visual and auditory stimuli.

Background: Previous psychophysiological studies have investigated temporal and spatial characteristics of neural processing of sensory stimuli (mainly somatosensorial and visual), whereas the definition of such processing at higher cognitive level has not been sufficiently addressed. The impairment of time and space processing is likely driven by basal ganglia dysfunction. However, other cortical and subcortical areas, including cerebellum, may also be involved.

Methods: We tested 21 subjects with CD and 22 age-matched healthy controls with 4 recognition tasks exploring visuo-spatial, audio-spatial, visuo-temporal, and audio-temporal processing. Dystonic subjects were subdivided in three groups according to the head movement pattern type (lateral: Laterocollis, rotation: Torticollis) as well as the presence of tremor (Tremor).

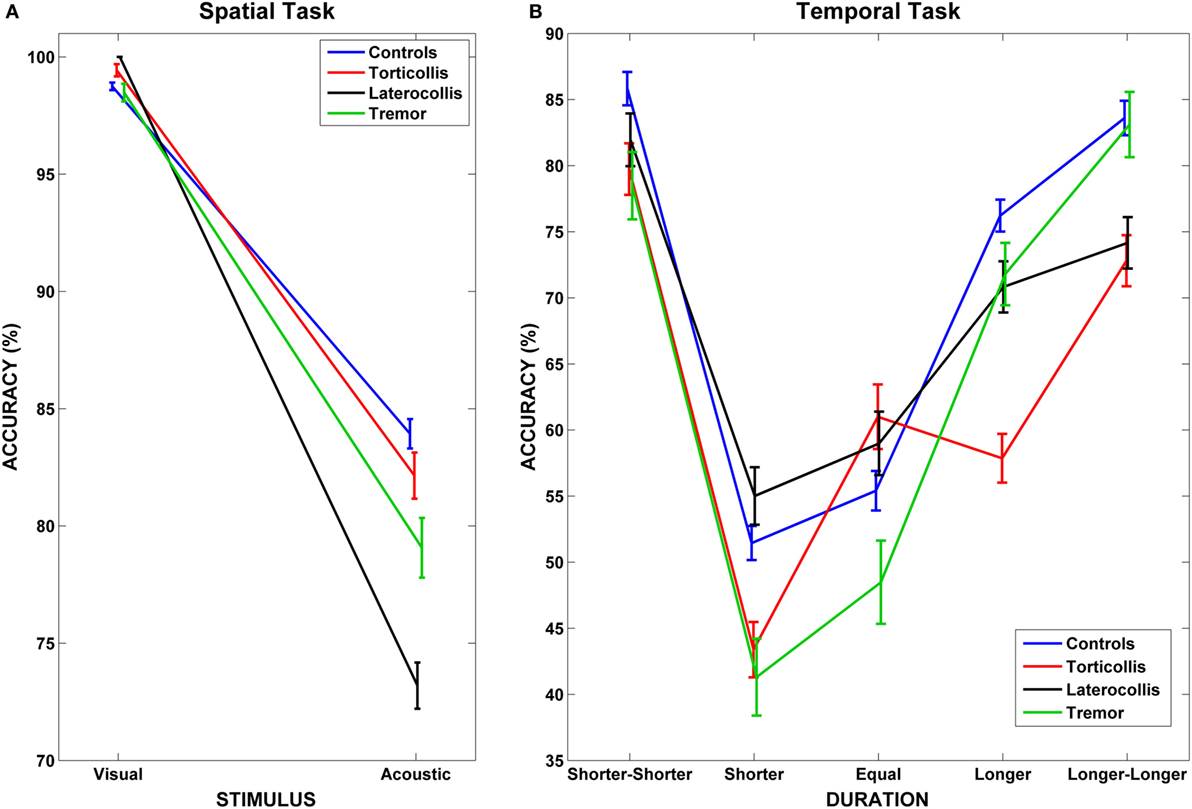

Results: We found significant alteration of spatial processing in Laterocollis subgroup compared to controls, whereas impairment of temporal processing was observed in Torticollis subgroup compared to controls.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that dystonia is associated with a dysfunction of temporal and spatial processing for visual and auditory stimuli that could underlie the well-known abnormalities in sequence learning. Moreover, we suggest that different movement pattern type might lead to different dysfunctions at cognitive level within dystonic population.

Introduction

Dystonia is a movement disorder characterized by patterned involuntary muscle contractions resulting in torsional movements and abnormal postures (1). Despite the “motor” definition of dystonia, there is increasing evidence that non-motor features, like depression (2) and dysfunctions in the sensory domain, are also present (3, 4). In keeping with this concept, few reports have shown subclinical sensory and perceptual dysfunctions (5) and impaired kinesthesia (6, 7); moreover, abnormal somatotopy in sensory areas has been reported by EEG (8), MEG (9–11), and fMRI (12, 13) studies. All these abnormalities are due to a dysfunction in sensory processing with a loss of lateral inhibition either in space or in time (13, 14). In fact, a series of studies have found that mild abnormalities in the primary sensory system are present in patients with dystonia both in spatial (15, 16) and temporal (17, 18) domains.

In dystonia, previous psychophysiological studies have related temporal and spatial dysfunctions as a consequence of sensory processing impairment, with a loss of lateral inhibition either in space or in time (13, 17, 19). However, the definition of such processing is controlled at higher cognitive level has not been sufficiently addressed. In addition, these studies have mostly focused on somatosensory stimuli finding out that somatosensory maps are alterated and produce blurred/altered representations of a person’s body in focal dystonia (20–22) with only a few studies investigating processing of visual stimuli (6, 23, 24), and no studies exploring processing of auditory stimuli.

There is increasing evidence that idiopathic cervical dystonia (CD) can be viewed as a circuit disorder, involving the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical as well as cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways (25, 26). The incorrect motor drive from the brain may cause various patterns of CD, the most common of which are the Laterocollis and the Torticollis; more rarely, we have dystonic tremor.

The aim of this study was to test whether in patients with CD the processing of spatial and temporal perception is impaired at higher cognitive level using recognition tasks that require attention to span both in the visual and auditory domains. Moreover, we further hypothesized that different movement pattern type of CD (Laterocollis, Torticollis, and prominent tremulous dystonia) may induce different cognitive deficit within dystonic population.

Materials and Methods

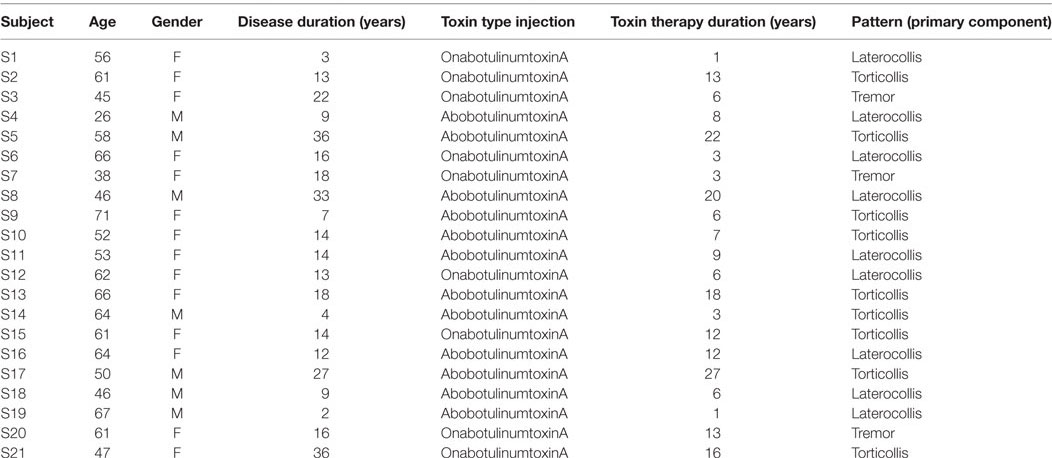

Twenty-one subjects (W/M, 14/7) with idiopathic CD (mean age 55.2 ± 11.01 years) and 22 healthy controls (W/M, 11/10) (mean age 54.41 ± 12.1 years) were recruited at the Movement Disorders Centre of University of Messina. All subjects were right-handed according to Edinburgh Handedness Inventory. Dystonic population was subdivided in three subgroups according to the head movement pattern type derived from the prevalent subscore at the Tsui scale (27): eight subjects were diagnosed as Laterocollis, eight were diagnosed as Torticollis, and five were diagnosed as tremulous CD (Tremor). All patients underwent extensive neurological examination and laboratory and neuroimaging investigations to rule out acquired causes of dystonia. None of the enrolled patients has been ever treated with drugs blocking the dopamine receptor. All drugs affecting the central nervous system were discontinued at least 1 week prior to the study; all patients were receiving botulinum toxin injections and were examined at least 3 months after the last injection. Clinical features of dystonic patients are given in Table 1.

Ethical Approval

The local ethical committee approved the entire research protocol and all subjects signed an informed consent before examination.

Task Settings

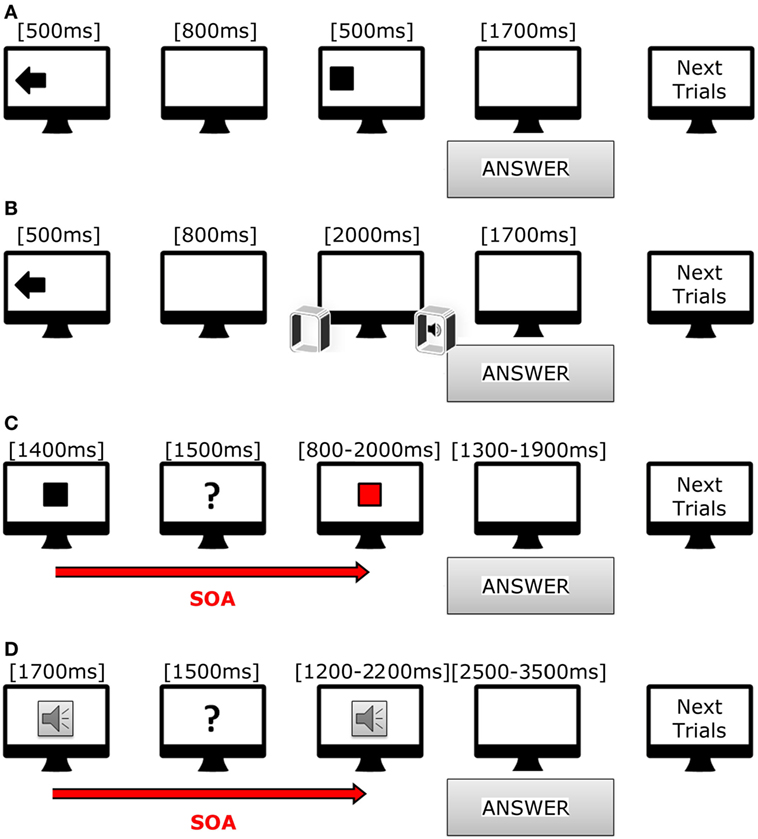

All tasks were prepared with Psychopy software (28) release 1.81. Stimuli were presented with a Dell workstation (21″ Dell monitor, resolution 1,680 × 1,050 pixels), and two speakers that were equidistant from the monitor. Subjects were comfortably sitting in front of the monitor at a distance of 70 cm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cartoon showing trials used in our tasks. (A) Scheme of incongruent trial in visual–spatial task. (B) Scheme of congruent trial in acoustic-spatial task. (C) Scheme of short trial in visual–temporal task. (D) Scheme of long trial in acoustic-temporal task.

Spatial Recognition Tasks

Each subject was asked to identify the position of either visual or auditory stimuli at a constant intertrial interval of 3,500 ms.

In the visuo-spatial task (Figure 1A), target presentation was preceded by the appearance of a visual cue lasting for 500 ms; the visual cue consisted of an arrow pointing either in right/left or down/up direction, or a cross in the center of the screen. After 800 ms, a white square (190 × 190 pixels) appeared for 500 ms in one of the four quadrants of the screen (right or left, upper and inferior). Subjects had to indicate as fast as possible the target position with respect to the direction of the preceding using a keyboard. The responses were thus classified in six categories: congruent (same direction for target and arrow), incongruent (opposite direction for target and arrow), neutral (target preceded by a cross). A total of 145 trials were presented (8.46 min).

In the audio-spatial task (Figure 1B), the target sound was preceded by the appearance of a visual cue on the screen, namely, an arrow pointing either to the right or left as well as a cross on screen center that lasted for 500 ms. The target sound was a beep (WAV, 44 kHz, 16 bit, duration 2,000 ms) produced by either the right or left speaker or simultaneously by both speakers. Subjects had to answer as soon as they realized the sound position using the same keyboard. The responses were thus classified in six categories: congruent (same direction for sound and arrow), incongruent (opposite directions for sound and arrow), neutral (sound preceded by a cross). We presented 72 trials (duration 4.2 min).

Temporal Recognition Tasks

The subjects had to evaluate whether the duration of a target stimulus, visual or auditory, was different from that of a reference stimulus. In the visuo-temporal task (Figure 1C), the reference stimulus was a white square appearing at the center of the screen for either 1,400 ms (fast condition) or 1,800 ms (slow condition). After 1,500 ms the target stimulus was presented, namely a red square appearing in the same position as the reference one. The target stimulus was either fast (range from 800 to 2,000 ms, with the reference stimulus of 1,400 ms) or slow (range from 1,000 to 2,600 ms, with the reference stimulus of 1,800 ms). At the end of each trial, each subject had to decide whether the duration of the target stimulus was equal to, shorter or longer than the reference. They were asked to answer as soon as possible after target presentation by using a keyboard. The responses were again classified in six categories: fast-shorter, fast-equal, fast-longer, slow-shorter, slow-equal, and slow-longer. A total of 72 trials were presented (8.34 min).

In the audio-temporal task (Figure 1D), the reference stimulus, a beep tone (WAV, 44 kHz, 16 bit), was presented for either 700 ms (fast) or 1,700 ms (slow), arranged in line with a screen one to the right and the other to the left. After 1,500 ms, the target stimulus was presented. During the fast condition, the target stimuli duration ranged from 400 to 1,000 ms (reference duration 700 ms), while during the slow condition, duration ranged from 1,200 to 2,200 ms (reference duration 1,700 ms). A total of 72 trials divided in 2 section were presented (8.12 min).

Data Analysis

For all the four tasks, we measured accuracy (number of correct answers) and reaction times (interval between stimulus onset and response).

Linear mixed models (LMM) were run separately on spatial and temporal tasks using accuracy rates as dependent variable to investigate differences between controls and different forms of dystonia (PatternType). For LMM on spatial tasks, three within-subject factors were considered: type of Stimulus (visual vs auditory), Congruency (congruent vs incongruent vs uninformative), and Position (right vs left vs centered). Notice that, for visual task, performances related to stimuli presented either in the upmost or in the bottom part of the screen were averaged together to facilitate comparison with the “centered” condition of auditory task; this decision was taken after observing that results from those two conditions largely overlapped both in terms of accuracy and reaction times.

For LMM on temporal tasks, following within-subject factors were considered: type of Stimulus (visual vs auditory), Speed (fast vs slow), Duration (shorter-shorter vs shorter vs equal vs longer vs longer-longer).

In both models, age and gender were used as covariates. As our primary interest was investigating accuracy rates, we further included an interaction between PatternType and reaction time as a covariate in the models; in this way, we wanted to account for potential interaction effects, e.g., speed-accuracy trade-off. In LMMs, covariance structure of residuals related to repeated measurement is explicitly fitted together with parameter estimates; different structures were adopted, and compared by means of Akaike information criteria (AIC). The smaller the AIC the better the model fit (29, 30). For both spatial and temporal LMMs, the best performances were obtained using a heterogeneous Toeplitz structure. Random effect on subjects was not included in the final models as the percentage of variance explained in this way was negligible after modeling covariance structure of residuals. In all analyses, cutoff for significance was set to 0.05. Multiple comparisons issue was accounted for by applying Bonferroni correction.

Before being administered cognitive tasks, Tsui and Pain scales were determined on CDs. At the time of the study, they were receiving different toxin types; moreover, disease duration and toxin therapy duration were quite variable. Thus, we tested whether those variables may influence either accuracy rates or reaction times. To this end, for both accuracy rates and reaction times, we estimated Kendall’s tau correlation coefficients between those measures and disease duration, as well as toxin therapy duration, Tsui and Pain scales. This analysis was performed both on global measures obtained by pooling all tasks together, as well as for each separate task. Moreover, we tested whether systematic differences may exist due to toxin type injection.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical features of dystonic patients. Correlation analyses performed between task outcomes and clinical features did not show significant differences within dystonic group, neither when pooling al subjects together, nor when separately analyzing subjects belonging to different dystonic patterns (corrected p-values >0.05).

Spatial Tasks

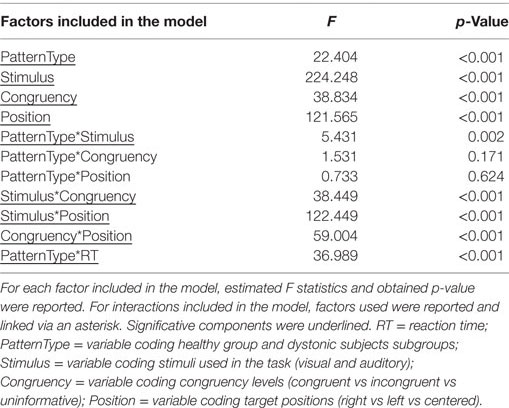

Results of LMM performed on spatial tasks are reported in detail in Table 2. A main effect of PatternType was observed (F = 22.404, p < 0.001); however, post hoc comparisons did not reveal significant differences after correcting for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, a significant interaction between PatternType and Stimulus was observed (F = 5.431, p = 0.002); post hoc analyses revealed that subjects diagnosed as Laterocollis were significantly less accurate than controls when processing auditory stimuli (average diff = 10.75%, SD error = 3.502, corrected p = 0.021, see Figure 2A). Moreover, a significant interaction with reaction time was observed (F = 36.989, p < 0.001). Post hoc analyses, after applying Bonferroni correction, showed that subjects diagnosed as Torticollis and Laterocollis were consistently slower than controls (Z = −2.976, corrected p = 0.018 and Z = −3.702, corrected p = 0.001, respectively). No significant differences were detected between controls and Tremor group, likely due to lack of statistical power.

Figure 2. Interaction between dystonic patients and tasks. (A) Accuracy rates for controls and dystonic subtypes highlight the lower accuracy for Laterocollis with respect to controls when spatially detecting acoustic stimuli. (B) We observe decreased accuracy for Torticollis with respect to controls when detecting target sounds that lasted “longer” than reference sounds in temporal tasks. Bars represent SEM.

Temporal Tasks

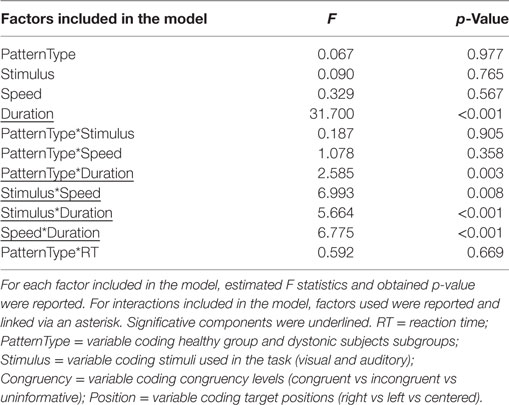

Results of LMM performed on temporal tasks are reported in detail in Table 3. We found a significant interaction between PatternType and Duration factors (F = 2.585, p = 0.003); post hoc analyses revealed, after applying Bonferroni correction, that subjects diagnosed as Torticollis were significantly less accurate than controls when detecting target stimuli whose duration with respect to reference sound was in condition longer (average diff = 18.362%, SD error = 6.616, corrected p = 0.043, see Figure 2B). Unlike for the spatial task, no significant interaction was observed with reaction times.

Discussion

Dystonia is a movement disorder characterized by patterned voluntary muscle contractions (1). However, non-motor features are also present, which may arise as a consequence of motor impairment or might have a more inherent genetic basis (2–4, 31–33). In this study, we aimed to test whether, in patients with idiopathic CD, the processing of spatial and temporal perception is impaired at higher cognitive level. We found that CD patients showed perceptive dysfunctions of different level with respect to neurophysiologic pattern type: a double dissociation in the performance between Laterocollis and Torticollis undergoing spatial and temporal tasks was indeed detected.

Spatial Tasks

In visuo-spatial task, we observed that dystonic patients were on average slower than controls, although significant differences were detected only for Torticollis and Laterocollis subtypes. This result likely reflects the motor features of the disorder (34). When investigating accuracies in spatial tasks, we found that Laterocollis were worse than healthy subjects in auditory but not visual task. It is known that a sound lasts in short-term memory for about 4 s while a visual stimulus persists for only 0.25 s (35); thus, we may hypothesize that the first sound mask the second one interfering on the response accuracy of the second auditory stimulus. This result may therefore indicate a perceptual abnormality on auditory recognition for Laterocollis.

Recent studies using intracranial recordings (36) and functional imaging (37) have provided compelling evidence for a hemispheric specialization in the auditory processing. It has been suggested that the processes associated with identification of linguistic auditory objects are lateralized toward the left hemisphere (38) while the paralinguistic aspects of vocal processing are lateralized toward the right hemisphere (39). According to this theory, in the left hemisphere, anterior brain structures are involved in expressive tasks, whereas posterior areas contribute to stimulus perception (40).

It is well known that idiopathic dystonia is mainly attributed to basal ganglia dysfunction (11). Hence, a greater left damage involving these structures may explain perceptual abnormality observed on the performance of the Laterocollis. It is important to highlight that this result was not confirmed neither for Torticollis, who were on average 1.78% less accurate than controls (SD error 3.5%), nor for subjects diagnosed as Tremor, who were on average 4.86% less accurate than controls (SD error 4.42%).

Temporal Tasks

When investigating temporal tasks, we found that subjects diagnosed as Torticollis were less accurate than healthy subjects when the duration of stimulus (exposure times) was in the condition “longer” with respect to reference sound.

It is supposed that the representation of numbers is arranged along a mental line, called mental number line (MNL) (41, 42). In people who read from left to right, the MNL is spatially oriented from left to right (43); Moreover, it is known that two numbers that are numerically distant are more easily and quickly detected [distance effect (44)]. In accordance to these theories, we observed that for all subjects it was easier to temporally discriminate reference from target sounds in presence of a clear temporal difference (45). This situation can be visualized in Figure 2B when looking at “shorter-shorter” and “longer-longer” conditions. The condition “equal” was the most difficult to detect, while performances improved either when moving towards “shorter” or “longer” conditions. Of importance, such pattern did not hold for Torticollis, who did not show an advantage for “long” condition (see Results).

Shomstein and Behrmann (46) found that longer exposure times of stimuli allowed more time for perceptual grouping and figure-ground segmentation, leading to the best representation of the object. On other hand, the effects of this representation diminished with long SOA (time between the onsets of reference and target components). This effect may explain the loss of accuracy of Torticollis in our temporal task. Therefore, Torticollis’ increased likelihood of making mistakes as time interval increases might undergo a difficult in maintaining temporal object representation. Some evidence of abnormal timing adjustment in CD was observed elsewhere (47, 48). However, in Filip et al. (48), both Torticollis and Laterocollis were not explicitly compared against each other: it might be the case that it was the Torticollis subgroup to mostly drive their result.

Pathophysiological Correlates of Visuo-Spatial and Audio-Spatial Impairment in CD

Several abnormalities in posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and ventral frontoparietal circuits have been observed in clinically unaffected carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation during learning of visuo-motor sequences, with a compensatory increased activation in the left ventral prefrontal cortex and lateral cerebellum (21). Furthermore, abnormal connectivity between PPC and primary motor cortex (M1) may be present in CD, an abnormality that is associated with slower reaching movements (49, 50). The interaction between PPC and M1 is crucial for the preparation and planning of movements directed to visual targets (51, 52), as it regulates visuo-spatial mechanisms that affect performance, accuracy, and variability.

The differences observed in our study between Laterocollis and Torticollis might be explained by involvement of different brain structures in these groups of patients, confirming a pivotal role of these circuits in the pathophysiology of idiopathic dystonia.

Indeed, a consistent body literature supports a major role of the basal ganglia in dystonia; however, more recent findings explore the causative role of other regions, in particular the cerebellum (48, 53), but no previous study has linked the respective basal ganglia and cerebellar networks with different patterns of dystonia. We might hypothesize that the difficulty of identifying the stimuli as result of spatial attention deficits, as we found in the case of Laterocollis, may be more marked in dystonic patients with major impairment of the basal ganglia. On the other side, it may be supposed that problems in time estimation of stimuli, as we found in Torticollis, are due to difficulty of object-based selective attention when a major cerebellar involvement occurs.

We did not identify, within CD group and after correcting for multiple comparisons, significant correlations between measured task outcomes and clinical features. It is, however, worth to mention that average accuracy rates in audio-spatial task showed a negative correlation with Tsui scale (Kendall’s tau = −0.408, uncorrected p = 0.016); this result did not come unexpected and may reflect increased difficulty for CDs to achieve good accuracy in audio-spatial processing when degree of impairment increases.

Finally, it may be postulated that the abnormal auditory and visual processing might also have a reflection on movement programming and planning (54). Movement preparation is known to be impaired in dystonia; movement preparation involves a number of factors, including the process of sensorimotor integration (55). The human nervous system prefers to be anticipatory rather than reactive, and a disordered preparation for movement will certainly be a crucial factor in faulty execution.

The heterogeneity and the small size of the population under study have to be considered the limitations of the present work. In addition, due to the small number of subjects, we could not stratify the patients according to the side (i.e., right or left) of the affected muscles. Future studies will be necessary to better explore parieto-motor connectivity during audio-motor or visuo-motor tasks by means, for instance, of fMRI or dual-coil TMS approaches, and to further clarify the differences, we observed within subtypes of dystonia.

Author Contributions

GC: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, drafting the work; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AC: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; responsible for data analyses; and substantial contribution to creation of figures for the work. FM: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, acquisition and interpretation of data for the work; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CT: substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. VR: substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. PG: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. MG: substantial contributions to revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. AQ: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, drafting the work; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; and final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors do not report any financial disclosure. The authors have no professional or financial affiliations that might be perceived as having biased the presentation.

References

1. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, DeLong MR, Fahn S, Fung VSC, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord (2013) 28(7):863–73. doi:10.1002/mds.25475

2. Moraru E, Schnider P, Wimmer A, Wenzel T, Birner P, Griengl H, et al. Relation between depression and anxiety in dystonic patients: implications for clinical management. Depress Anxiety (2002) 16(3):100–3. doi:10.1002/da.10039

3. Fabbrini G, Pantano P, Totaro P, Calistri V, Colosimo C, Carmellini M, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in patients with primary cervical dystonia and in patients with blepharospasm. Eur J Neurol (2008) 15:185–9. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02034.x

4. Kuyper DJ, Parra V, Aerts S, Okun MS, Kluger BM. Nonmotor manifestations of dystonia: a systematic review. Mov Disord (2011) 26:1206–17. doi:10.1002/mds.23709

5. Frima N, Nasir J, Grunewald RA. Abnormal vibration-induced illusion of movement in idiopathic focal dystonia: an endophenotypic marker? Mov Disord (2008) 23:373–7. doi:10.1002/mds.21838

6. Putzki N, Stude P, Konczak J, Graf K, Diener HC, Maschke M. Kinesthesia is impaired in focal dystonia. Mov Disord (2006) 21:754–60. doi:10.1002/mds.20799

7. Bara-Jimenez W, Catalan MJ, Hallett M, Gerloff C. Abnormal somatosensory homunculus in dystonia of the hand. Ann Neurol (1998) 44:828–31. doi:10.1002/ana.410440520

8. Meunier S, Garnero L, Ducorps A, Mazières L, Lehéricy S, du Montcel ST, et al. Human brain mapping in dystonia reveals both endophenotypic traits and adaptive reorganization. Ann Neurol (2001) 50:521–7. doi:10.1002/ana.1234

9. Meunier S, Hallett M. Endophenotyping: a window to the pathophysiology of dystonia. Neurology (2005) 65:792–3. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000177919.02950.4a

10. Butterworth S, Francis S, Kelly E, McGlone F, Bowtell R, Sawle GV. Abnormal cortical sensory activation in dystonia: an fMRI study. Mov Disord (2003) 18:673–82. doi:10.1002/mds.10416

11. Peller M, Zeuner KE, Munchau A, Quartarone A, Weiss M, Knutzen A, et al. The basal ganglia are hyperactive during the discrimination of tactile stimuli in writer’s cramp. Brain (2006) 129:2697–708. doi:10.1093/brain/awl181

12. Frasson E, Priori A, Bertolasi L, Mauguière F, Fiaschi A, Tinazzi M. Somatosensory disinhibition in dystonia. Mov Disord (2001) 16:674–82. doi:10.1002/mds.1142

13. Tinazzi M, Priori A, Bertolasi L, Frasson E, Mauguière F, Fiaschi A. Abnormal central integration of a dual somatosensory input in dystonia. Evidence for sensory overflow. Brain (2000) 123(Pt 1):42–50. doi:10.1093/brain/123.1.42

14. Serrien DJ, Burgunder JM, Wiesendanger M. Disturbed sensorimotor processing during control of precision grip in patients with writer’s cramp. Mov Disord (2000) 15:965–72. doi:10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<965::AID-MDS1030>3.0.CO;2-0

15. Klintenberg R, Gunne L, Andren PE. Tardive dyskinesia model in the common marmoset. Mov Disord (2002) 17:360–5. doi:10.1002/mds.10070

16. Burke RE, Fahn S. An evaluation of sustained postural abnormalities in rats induced by intracerebro-ventricular injection of chlorpromazine methiodide or somatostatin as models of dystonia. Adv Neurol (1988) 50:335–42.

17. Tinazzi M, Fiaschi A, Frasson E, Fiorio M, Cortese F, Aglioti SM. Deficits of temporal discrimination in dystonia are independent from the spatial distance between the loci of tactile stimulation. Mov Disord (2002) 17:333–8. doi:10.1002/mds.10019

18. Fiorio M, Tinazzi M, Scontini A, Stanzani C, Gambarin M, Fiaschi A, et al. Tactile temporal discrimination in patients with blepharospasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2008) 79:796–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.131524

19. Tinazzi M, Fiorio M, Fiaschi A, Rothwell JC, Bhatia KP. Sensory functions in dystonia: insights from behavioral studies. Mov Disord (2009) 24(10):1427–36. doi:10.1002/mds.22490

20. Ghilardi MF, Carbon M, Silvestri G, Dhawan V, Tagliati M, Bressman S, et al. Impaired sequence learning in carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Ann Neurol (2003) 54(1):102–9. doi:10.1002/ana.10610

21. Fiorio M, Tinazzi M, Bertolasi L, Aglioti SM. Temporal processing of visuotactile and tactile stimuli in writer’s cramp. Ann Neurol (2003) 53:630–5. doi:10.1002/ana.10525

22. Quartarone A, Rizzo V, Terranova C, Milardi D, Bruschetta D, Ghilardi MF, et al. Sensory abnormalities in focal hand dystonia and non-invasive brain stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci (2014) 8:956. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00956

23. Irvine E. Rich experience and sensory memory. Philos Psychol (2011) 24(2):159–76. doi:10.1080/09515089.2010.543415

24. King AJ. Visual influences on auditory spatial learning. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci (2009) 364(1515):331–9. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0230

25. Lehéricy S, Tijssen MA, Vidailhet M, Kaji R, Meunier S. The anatomical basis of dystonia: current view using neuroimaging. Mov Disord (2013) 28(7):944–57. doi:10.1002/mds.25527

26. Quartarone A, Hallett M. Emerging concepts in the physiological basis of dystonia. Mov Disord (2013) 28(7):958–67. doi:10.1002/mds.25532

27. Tsui JC, Sroessl AJ, Eisen A, Calne S, Calne DB. Double-blind study of botulinum toxin in spasmodic torticollis. Lancet (1986) 328(8501):245–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92070-2

28. Peirce JW. PsychoPy – psychophysics software in Python. J Neurosci Methods (2007) 62(1–2):8–13. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.017

30. Sakamoto Y, Ishiguro M, Kitagawa G. Akaike Information Criterion Statistics. Boston, MA: D. Reidel Publishing Company (1986).

31. Klein C. Genetics in dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2014) 20:S137–42. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70033-6

32. Crisafulli C, Chiesa A, Han C, Lee S-J, Balzarro B, Andrisano C, et al. Case-control association study of 36 single-nucleotide polymorphisms within 10 candidate genes for major depression and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res (2013) 209:121–3. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.009

33. Calati R, Crisafulli C, Balestri M, Serretti A, Spina E, Calabrò M, et al. Evaluation of the role of MAPK1 and CREB1 polymorphisms on treatment resistance, response and remission in mood disorder patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2013) 44:271–8. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.03.005

35. Grice GR, Gwynne JW. Temporal characteristics of noise conditions producing facilitation and interference. Percept Psychophys (1985) 37:495–501. doi:10.3758/BF03204912

36. Liegeois-Chauvel C, Lorenzi C, Trebuchon A, Regis J, Chauvel P. Temporal envelope processing in the human left and right auditory cortices. Cereb Cortex (2004) 14:731–40. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh033

37. Zatorre RJ, Belin P. Spectral and temporal processing in human auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex (2001) 11:946–53. doi:10.1093/cercor/11.10.946

38. Parker GJ, Luzzi S, Alexander DC, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Ciccarelli O, Lambon RMA. Lateralization of ventral and dorsal auditory-language pathways in the human brain. Neuroimage (2005) 24:656–66. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.047

39. Belin P, Fecteau S, Bedard C. Thinking the voice: neural correlates of voice perception. Trends Cogn Sci (2004) 8:129–35. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.01.008

40. Ross ED, Thompson RD, Yenkosky J. Lateralization of affective prosody in brain and the callosal integration of hemispheric language functions. Brain Lang (1997) 56:27–54. doi:10.1006/brln.1997.1731

41. Umiltà C, Priftis K, Zorzi M. The spatial representation of numbers: evidence from neglect and pseudoneglect. Exp Brain Res (2009) 192:561–9. doi:10.1007/s00221-008-1623-2

42. Oliveri M, Vicario CM, Salerno S, Koch G, Turriziani P, Mangano R, et al. Perceiving numbers alters time perception. Neurosci Lett (2008) 438(3):308–11. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.051

43. Dehaene S, Piazza M, Pinel P, Cohen L. Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cogn Neuropsychol (2003) 20:487–506. doi:10.1080/02643290244000239

44. Moyer RS, Landauer TK. The time required for judgements of numerical inequality. Nature (1967) 215:1519–20. doi:10.1038/2151519a0

45. Jolicoeur P, Lefebvre CJ. Mechanisms of Sensory Working Memory: Attention and Performance XXV. London: Academic Press (2015).

46. Shomstein S, Behrmann M. Object-based attention: strength of object representation and attentional guidance. Percept Psychophys (2008) 70(1):132–44. doi:10.3758/PP.70.1.132

47. Sadnicka A, Hoffland BS, Bhatia KP, van de Warrenburg BP, Edwards MJ. The cerebellum in dystonia – help or hindrance? Neurophysiol Clin (2012) 123(1):65–70. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2011.04.027

48. Filip P, Lungu OV, Shaw DJ, Kasparek K, Bareš M. The mechanisms of movement control and time estimation in cervical dystonia patients. Neural Plast (2013) 2013:908741. doi:10.1155/2013/908741

49. Koch G, Fernandez Del Olmo M, Cheeran B, Schippling S, Caltagirone C, Driver J, et al. Functional interplay between posterior parietal and ipsilateralmotor cortex revealed by twin-coil transcranial magnetic stimulation during reach planning toward contralateral space. J Neurosci (2008) 28:5944–53. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0957-08.2008

50. Ricci R, Salatino A, Siebner H, Mazzeo G, Nobili M. Normalizing biased spatial attention with parietal rTMS in a patient with focal hand dystonia. Brain Stimulat (2014) 7(6):912. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2014.07.038

51. Vicario M, Martino D, Koch G. Temporal accuracy and variability in the left and right posterior parietal cortex. Neuroscience (2013) 245:121–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.041

52. Koch G, Cercignani M, Pecchioli C, Versace V, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C, et al. In vivo definition of parieto-motor connections involved in planning of grasping movements. Neuroimage (2010) 51:300–12. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.022

53. Perlov E, Tebarzt van Elst L, Buechert M. H1-MR spectroscopy of cerebellum in adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Psychiatr Res (2010) 44(14):938–43. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.016

54. Blauert J. The Psychophysics of Human Sound Localization. Revised ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (1996).

Keywords: Laterocollis, Torticollis, spatial processing, temporal processing, attention

Citation: Chillemi G, Calamuneri A, Morgante F, Terranova C, Rizzo V, Girlanda P, Ghilardi MF and Quartarone A (2017) Spatial and Temporal High Processing of Visual and Auditory Stimuli in Cervical Dystonia. Front. Neurol. 8:66. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00066

Received: 19 July 2016; Accepted: 15 February 2017;

Published: 03 March 2017

Edited by:

Ryuji Kaji, University of Tokushima, JapanReviewed by:

Cristian F. Pecurariu, Transylvania University, USAPedro Ribeiro, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Copyright: © 2017 Chillemi, Calamuneri, Morgante, Terranova, Rizzo, Girlanda, Ghilardi and Quartarone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gaetana Chillemi, Y2hpbGxlbWkudGFuaWFAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Gaetana Chillemi

Gaetana Chillemi Alessandro Calamuneri

Alessandro Calamuneri Francesca Morgante

Francesca Morgante Carmen Terranova

Carmen Terranova Vincenzo Rizzo

Vincenzo Rizzo Paolo Girlanda

Paolo Girlanda Maria Felice Ghilardi

Maria Felice Ghilardi Angelo Quartarone

Angelo Quartarone