- 1Laboratory of Neuroanatomy and Neuropsychobiology, Department of Pharmacology, Ribeirão Preto Medical School of the University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil

- 2Department of Psychology and Institute for Neuroscience, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

Introduction

Discovering that photobiomodulation (PBM) is neuroprotective and has augmentation effects on human neurocognitive functions has been groundbreaking (1). Transcranial PBM with near-infrared light at low irradiance (mW/cm2) and high energy density or fluence (J/cm2) modulates neural functions in a non-thermal way that may have therapeutic effects on various neurological disorders (2). Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by a persistent predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by neurological, cognitive, and psychosocial consequences (3), in addition to postictal antinociception (4–7) and psychiatric comorbidities (8, 9). It is the fourth most common neurological condition in the world. An estimated 70 million people are suffering from some type of epileptic syndrome (10–12). We propose that transcranial PBM may be developed as a new non-invasive therapeutic strategy for epilepsy based on the following: (1) its well-documented mitochondrial mechanism of action relevant to epilepsy, (2) its beneficial neurocognitive effects in humans, and (3) the promising findings from two recent PBM studies in different epilepsy models.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Epilepsy

One hypothesis to explain the role of mitochondria in epilepsy is linked to metabolic and energy changes after acute seizures and during chronic epilepsy (13–19). For example, Mueller et al. (14) noted that redox status measured by reduced and oxidized forms of glutathione changes to a more oxidized state in the brain and plasma of epileptic patients. During seizure activity, an acute increase in glucose metabolism and cerebral blood flow is observed in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (17), the most prevalent form of acquired epilepsies (20). In addition, in the study conducted by Vielhaber et al. (19), it was noted that the hypometabolism observed in patients with epilepsy is associated with low levels of mitochondrial N-acetyl aspartate in the CA3 hippocampal subfield. Reduced levels of NAD(P)H were also observed in CA1, CA2, and the subiculum of patients with TLE (21).

Studies performed in laboratory animals have suggested mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress as a key mechanism that follows seizures and contributes to epileptogenesis (20, 22, 23). After seizures there are many changes related to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, including an acute increase in mitochondrial oxidative stress, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, increased oxidation of cellular macromolecules, mitochondrial DNA damage, decreased activity of the electron transport chain (ETC), and increased nitric oxide (NO) generation in the cerebral cortex (24) and hippocampus (22, 25–27). Also, studies have shown a decrease in hippocampal ETC complex I and IV activity and oxidative stress in CA1 and CA3 during chronic epilepsy (15, 16, 18).

In view of this, targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress with PBM may provide a new therapeutic strategy to attenuate seizure activity, impairments linked to neuronal loss, and cognitive function (30).

Mitochondrial Mechanism of Action of Photobiomodulation

Generally, PBM, also known as low-level laser therapy (31), is a non-invasive method that has been shown to modulate neuronal functions, including mitochondrial energy metabolism, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (32, 33). The mechanism of action of PBM primarily involves a photonic biochemical effect on mitochondrial respiration and oxidative stress (34). The major acceptor of red-to-near-infrared photons inside cells is the mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome c oxidase (CCO, also called ETC complex IV), which is considered a fundamental molecule for the action of PBM (35–38).

Photonic oxidation of CCO by transcranial PBM with a near-infrared laser has been demonstrated in vivo in the human brain (39, 40). PBM can induce a series of beneficial cellular events, such as the increase in oxidative phosphorylation for ATP production, increased permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, a brief increase in ROS, and activation of mitochondrial signaling pathways linked to neuroprotection and cell survival (2, 41). In addition, NO released by CCO is able to stimulate ATP production by increasing mitochondrial membrane potential and oxygen consumption (35, 36, 38, 42–44), as well as triggering a physiological hemodynamic response to increasing delivery of oxygen to the human brain (39, 40). However, mechanisms other than CCO may mediate PBM effects under certain conditions, as suggested by the extensive metabolomic effects of PBM on the rat brain (45).

Neurocognitive Effects of Photobiomodulation in Humans

Many human studies have demonstrated the potential of transcranial PBM for the augmentation of neurocognitive functions under several conditions (1, 46–54). Studies using laboratory animals have also documented interesting results of brain PBM (45, 55, 56). For example, our research group submitted aged rats to PBM with transcranial laser for 58 consecutive days and we noted that laser treatment was able to rejuvenate the spatial mnemonic damage of the aged rats and modulate brain levels of inflammatory markers (56). In addition, this same laser treatment protocol increased the brain metabolic pathways of young rats and restored the brain metabolic pathways of aged rats to the levels of younger rats (45).

Studies of Photobiomodulation in Epilepsy Models

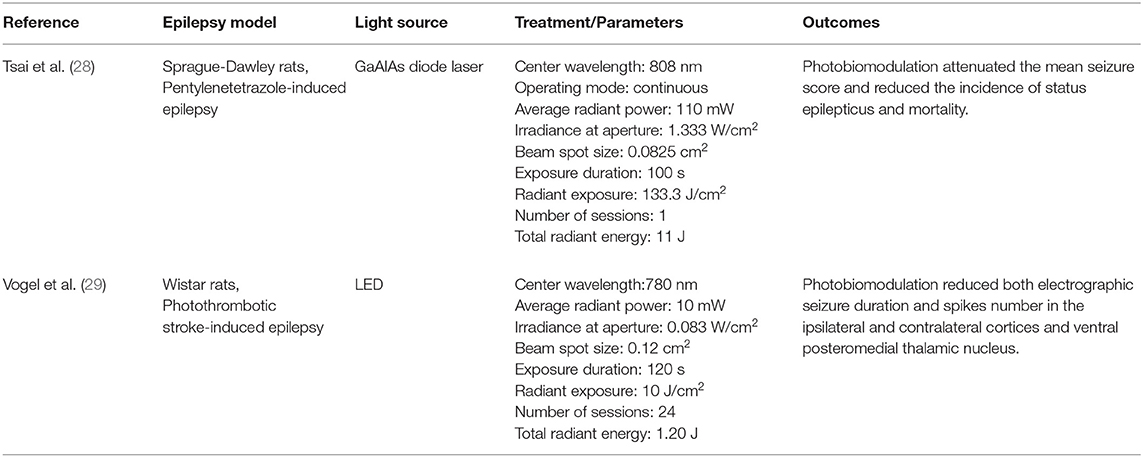

Regarding epilepsy, there have been two recent pre-clinical studies showing beneficial effects of PBM in different epilepsy models (Table 1).

First, Tsai et al. (28) noted that transcranial PBM at wavelength 808 nm was able to attenuate pentylenetetrazole-induced status epilepticus in peripubertal rats. In addition, PBM reduced the apoptotic ratio of parvalbumin-labeled interneurons and alleviated the aberrant extent of parvalbumin-labeled unstained somata of principal cells in the hippocampus. Second, Vogel et al. (29) observed that PBM reduces epileptiform discharges after a stroke (29). They showed that a 780 nm wavelength laser treatment for 2 months after induction of photothrombotic stroke reduced late epileptic electrographic seizures, as well as the number of spikes in the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices and in the ventral posteromedial thalamic nuclei. Although there is a possibility that PBM could trigger epileptic seizures, there is no evidence in support for this, and the two studies evaluating PBM effects on seizure models have found that PBM reduces seizures.

Although these studies present interesting behavioral findings on PBM in epilepsy (28, 29), evidence regarding mitochondrial functions is still lacking. This line of reasoning would be interesting since studies show that mitochondrial damage under various conditions is restored by PBM. Furthermore, this restoration is accompanied by an improvement in behavioral performance (57–59). In fact, PBM increases mitochondrial membrane potential, contributing to an increase in ATP production and a brief increase in ROS (34, 60, 61). In addition, ROS and other mediators of PBM, such as NO and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), activate transcription factors. In this sense, after PBM, CCO stimulates ATP synthesis (62, 63). Extracellular ATP is also a neurotransmitter (64) that participates in many signaling pathways, known as purinergic signaling (65). NO acts by stimulation of guanylate cyclase to form cyclic-GMP (cGMP), which induces Ca++ reuptake and the opening of calcium-activated potassium channels via protein kinase G (66). ROS is a mediator that at low concentrations and brief exposures is beneficial, and at high concentrations and long exposure, periods are harmful (67). When induced by PBM, ROS activates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), which contributes to the increase in gene transcription, and consequently cellular processes, such as proliferation, migration, and cell death (60). cAMP can down-regulate the LPS-induced TNF-α synthesis at the transcriptional level (68–70). Also, cAMP exerts its cellular effects through the signaling of protein kinase A (PKA), cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGC), and exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (Epac) (71–73). Together, the upregulation of mitochondrial respiration that triggers these metabolic signaling cascades suggests that the long-term effects of PBM might be beneficial to treat the mitochondrial deficits found in epilepsy.

Although these results are promising, much more evidence of the effects of PBM on the epileptic brain is needed. When this evidence becomes available, then PBM may be translated to the clinic, but the evidence is too limited at this time.

Conclusion

Transcranial PBM may treat the mitochondrial dysfunction in epilepsy by upregulating CCO, which is the terminal enzyme in mitochondrial respiration. This mitochondrial mechanism of action of PBM might benefit epilepsy because transcranial PBM is neuroprotective and improves human neurocognitive functions affected by epilepsy. This fascinating new intervention is safe and non-invasive and should be tested further to confirm if augmenting neuronal mitochondrial respiration is a neurotherapeutic strategy for epilepsy.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grants 1996/8574-9 and 2009/00668-6), Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Tecnológico (CNPq) (grant 474425/2008-8) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior (CAPES) (AUX-PE-PNPD 2400/2009; grant 23038.027801/2009-37). None of these organizations had a role in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. FC was financially supported by FAPESP (Postdoctoral fellowship grant 2021/06473-4). NC Coimbra is a researcher from CNPq (PQ1A-level grants 301905/2010-0 and 301341/2015-0; PQ2-level grant 302605/2021-5). FG-L was supported by the Oskar Fischer Project Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gonzalez-Lima F. Neuroprotection and Neurocognitive augmentation by Photobiomodulation. In: Opris, I., Lebedev, M. A., Casanova, M. F. (Eds), Modern Approaches to Augmentation of Brain Function. Cham: Springer. (2021). p. 165–207. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-54564-2_9

2. Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Neurological and psychological applications of transcranial lasers and LEDs. Biochem Pharmacol. (2013) 86:447–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.012

3. Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the international league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia. (2017) 58:522–30. doi: 10.1111/epi.13670

4. Coimbra NC, Freitas RL, Savoldi M, Castro-Souza C, Segato EN, Kishi R, et al. Opioid neurotransmission in the post-ictal analgesia: involvement of μ1-opioid receptor. Brain Res. (2001) 903:216–21. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02366-6

5. Freitas RL, Ferreira CMR, Ribeiro SJ, Carvalho AD, Elias-Filho DH, Garcia-Cairasco N, et al. Intrinsic neural circuits between dorsal midbrain neurons that control fear-induced responses and seizure activity and nuclei of the pain inhibitory system elaborating postictal antinociceptive processes: a functional neuroanatomical and neuropharmacological study. Exp Neurol. (2005) 191:225–42. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.10.009

6. Freitas RL, Bassi GS, de Oliveira AM, Coimbra NC. Serotonergic neurotransmission in the dorsal raphe nucleus recruits in situ 5-HT2A/2C receptors to modulate the post-ictal antinociception. Exp Neurolol. (2008) 213:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.003

7. Freitas RL, Ferreira CMR, Urbina MA, Mariño AU, Carvalho AD, Butera G, et al. 5-HT1A/1B, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 serotonergic receptors recruitment in tonic-clonic seizure-induced antinociception: role of dorsal raphe nucleus. Exp Neurolol. (2009) 217:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.003

8. Fiordelli E, Beghi E, Bogliun G, Crespi V. Epilepsy and psychiatric disturbance. A cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiat. (1993) 163:446–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.4.446

9. Jakobsen AV, Elklit A. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in children with severe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 122:108217. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108217

10. Reynolds EH. Introduction: epilepsy in the world. Epilepsia. (2002) 43:1–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.6.1.x

11. Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Sander JW, Newton CR. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: a meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia. (2010) 51:883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x

12. Bell GS, Neligan A, Sander JW. An unknown quantity—the worldwide prevalence of epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2014) 55:958–62. doi: 10.1111/epi.12605

13. Kunz WS, Kudin AP, Vielhaber S, Blümcke I, Zuschratter W, Schramm J, et al. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in the epileptic focus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. (2000) 48:766–73. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200011)48:5<766::AID-ANA10>3.0.CO;2-M

14. Mueller SG, Trabesinger AH, Boesiger P, Wieser HG. Brain glutathione levels in patients with epilepsy measured by in vivo 1H-MRS. Neurology. (2001) 57:1422–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.8.1422

15. Kudin AP, Kudina TA, Seyfried J, Vielhaber S, Beck H, Elger CE, et al. Seizure-dependent modulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. (2002) 15:1105–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01947.x

16. Chuang YC, Chang AY, Lin JW, Hsu SP, Chan SH. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ultrastructural damage in the hippocampus during kainic acid–induced status epilepticus in the rat. Epilepsia. (2004) 45:1202–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.18204.x

17. Kawai N, Miyake K, Kuroda Y, Yamashita S, Nishiyama Y, Monden T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography findings in status epilepticus following severe hypoglycemia. Ann Nucl Med. (2006) 20:371–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02987250

18. Gao J, Chi ZF, Liu XW, Shan PY, Wang R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ultrastructural damage in the hippocampus of pilocarpine-induced epileptic rat. Neurosci Lett. (2007) 411:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.022

19. Vielhaber S, Niessen HG, Debska-Vielhaber G, Kudin AP, Wellmer J, Kaufmann J, et al. Subfield-specific loss of hippocampal N-acetyl aspartate in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2008) 49:40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01280.x

20. Rowley S, Patel M. Mitochondrial involvement and oxidative stress in temporal lobe epilepsy. Free Radic Biol Med. (2013) 62:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.002

21. Kann O, Kovács R, Njunting M, Behrens CJ, Otáhal J, Lehmann TN, et al. Metabolic dysfunction during neuronal activation in the ex vivo hippocampus from chronic epileptic rats and humans. Brain. (2005) 128:2396–407. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh568

22. Waldbaum S, Liang LP, Patel M. Persistent impairment of mitochondrial and tissue redox status during lithium-pilocarpine-induced epileptogenesis. J Neurochem. (2010) 115:1172–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07013.x

23. Puttachary S, Sharma S, Stark S, Thippeswamy T. Seizure-induced oxidative stress in temporal lobe epilepsy. Biomed Res Int. (2015) 2015:745613. doi: 10.1155/2015/745613

24. Tejada S, Sureda A, Roca C, Gamundi A, Esteban S. Antioxidant response and oxidative damage in brain cortex after high dose of pilocarpine. Brain Res Bull. (2007) 71:372–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.10.005

25. Bruce AJ, Baudry M. Oxygen free radicals in rat limbic structures after kainate-induced seizures. Free Radic Biol Med. (1995) 18:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00218-9

26. Liang LP, Ho YS, Patel M. Mitochondrial superoxide production in kainate-induced hippocampal damage. Neuroscience. (2000) 101:563–70. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00397-3

27. Jarrett SG, Liang LP, Hellier JL, Staley KJ, Patel M. Mitochondrial DNA damage and impaired base excision repair during epileptogenesis. Neurobiol Dis. (2008) 30:130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.009

28. Tsai CM, Chang SF, Chang H. Transcranial photobiomodulation attenuates pentylenetetrazole-induced status epilepticus in peripubertal rats. J Biophotonics. (2020) 13:e202000095. doi: 10.1002/jbio.202000095

29. Vogel DD, Ortiz-Villatoro NN, de Freitas L, Aimbire F, Scorza FA, Albertini R, et al. Repetitive transcranial photobiomodulation but not long-term omega-3 intake reduces epileptiform discharges in rats with stroke-induced epilepsy. J Biophotonics. (2021) 14:e202000287. doi: 10.1002/jbio.202000287

30. Pearson-Smith JN, Patel M. Metabolic dysfunction and oxidative stress in epilepsy. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:2365. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112365

31. Anders JJ, Lanzafame RJ, Arany PR. Low-level light/laser therapy versus photobiomodulation therapy. Photomed Laser Surg. (2015) 33:183–4. doi: 10.1089/pho.2015.9848

32. Roja JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Low-level light therapy of the eye and brain. Eye and Brain. (2011) 3:49. doi: 10.2147/eb.s21391

33. Chung H, Dai T, Sharma SK, Huang YY, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR. The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Ann Biomed Eng. (2012) 40:516–33. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0454-7

34. Gonzalez-Lima F, Barksdale BR, Rojas JC. Mitochondrial respiration as a target for neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Biochem Pharmacol. (2014) 88:584–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.010

35. Karu TI. Molecular mechanism of the therapeutic effect of low-intensity laser radiation. Lasers Life Sci. (1988) 2:53–74.

36. Karu TI. Primary and secondary mechanisms of action of visible to near-IR radiation on cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. (1999) 49:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00219-X

37. Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS. Photobiological modulation of cell attachment via cytochrome c oxidase. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2004) 3:211–6. doi: 10.1039/b306126d

38. Karu TI, Kolyakov SF. Exact action spectra for cellular responses relevant to phototherapy. Photomed Laser Surg. (2005) 23:355–61. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.355

39. Wang X, Tian F, Reddy DD, Nalawade SS, Barrett DW, Gonzalez-Lima F, et al. Up-regulation of cerebral cytochrome-c-oxidase and hemodynamics by transcranial infrared laser stimulation: a broadband near-infrared spectroscopy study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2017) 37:3789–802. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17691783

40. Saucedo CL, Courtois EC, Wade ZS, Kelley MN, Kheradbin N, Barrett DW, et al. Transcranial laser stimulation: Mitochondrial and cerebrovascular effects in younger and older healthy adults. Brain Stimul. (2021) 14:440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2021.02.011

41. dos Santos Cardoso F, Mansur FC, Araújo BH, Gonzalez-Lima F, Gomes da Silva S. Photobiomodulation improves the inflammatory response and intracellular signaling proteins linked to vascular function and cell survival in the brain of aged rats. Mol Neurobiol. (2021) 59:420–8. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02606-4

42. Passarella S, Casamassima E, Molinari S, Pastore D, Quagliariello E, Catalano IM, et al. Increase of proton electrochemical potential and ATP synthesis in rat liver mitochondria irradiated in vitro by helium-neon laser. FEBS Lett. (1984) 175:95–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80577-3

43. Hamblin MR. The role of nitric oxide in low level light therapy. in Biomedical Optics (BiOS). International Society for Optics and Photonics. (2008). 6846:684602:684614. doi: 10.1117/12.764918

45. dos Santos Cardoso F, Dos Santos JC, Gonzalez-Lima F, Araújo BH, Lopes-Martins RÁ, Gomes da Silva S. Effects of chronic photobiomodulation with transcranial near-infrared laser on brain metabolomics of young and aged rats. Mol Neurobiol. (2021) 58:2256–2268. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02247-z

46. Barrett DW, Gonzalez-Lima F. Transcranial infrared laser stimulation produces beneficial cognitive and emotional effects in humans. Neuroscience. (2013) 230:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.016

47. Disner SG, Beevers CG, Gonzalez-Lima F. Transcranial laser stimulation as neuroenhancement for attention bias modification in adults with elevated depression symptoms. Brain Stimul. (2016) 9:780–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.05.009

48. Hwang J, Castelli DM, Gonzalez-Lima F. Cognitive enhancement by transcranial laser stimulation and acute aerobic exercise. Lasers Med Sci. (2016) 31:1151–60. doi: 10.1007/s10103-016-1962-3

49. Vargas E, Barrett DW, Saucedo CL, Huang LD, Abraham JA, Tanaka H, et al. Beneficial neurocognitive effects of transcranial laser in older adults. Lasers Med Sci. (2017) 32:1153–62. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2221-y

50. Blanco NJ, Maddox WT, Gonzalez-Lima F. Improving executive function using transcranial infrared laser stimulation. J Neuropsychol. (2017) 11:14–25. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12074

51. Blanco NJ, Saucedo CL, Gonzalez-Lima F. Transcranial infrared laser stimulation improves rule-based, but not information-integration, category learning in humans. Neurobiol Learn Mem. (2017) 139:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.12.016

52. Saltmarche AE, Naeser MA, Ho KF, Hamblin MR, Lim L. Significant improvement in cognition in mild to moderately severe dementia cases treated with transcranial plus intranasal photobiomodulation: case series report. Photomed Laser Surg. (2017) 35:432–41. doi: 10.1089/pho.2016.4227

53. Holmes E, Barrett DW, Saucedo CL, O'Connor P, Liu H, Gonzalez-Lima F. Cognitive enhancement by transcranial photobiomodulation is associated with cerebrovascular oxygenation of the prefrontal cortex. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:1129. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01129

54. O'Donnell CM, Barrett DW, Fink LH, Garcia-Pittman EC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Transcranial infrared laser stimulation improves cognition in older bipolar patients: proof of concept study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2021) 35:321–32. doi: 10.1177/0891988720988906

55. Oron A, Oron U, Streeter J, Taboada LD, Alexandrovich A, Trembovler V, et al. Low-level laser therapy applied transcranially to mice following traumatic brain injury significantly reduces long-term neurological deficits. J Neurotrauma. (2007) 24:651–6. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0198

56. Cardoso FD, de Souza Oliveira Tavares C, Araujo BH, Mansur F, Lopes-Martins RA, Gomes da Silva S. Improved spatial memory and neuroinflammatory profile changes in aged rats submitted to photobiomodulation therapy. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2021) 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10571-021-01069-4

57. Salehpour F, Farajdokht F, Cassano P, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Erfani M, Hamblin MR, et al. Near-infrared photobiomodulation combined with coenzyme Q10 for depression in a mouse model of restraint stress: reduction in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Brain Res Bull. (2019) 144:213–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.10.010

58. Salehpour F, Ahmadian N, Rasta SH, Farhoudi M, Karimi P, Sadigh-Eteghad S. Transcranial low-level laser therapy improves brain mitochondrial function and cognitive impairment in D-galactose–induced aging mice. Neurobiol Aging. (2017) 58:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.06.025

59. Zhang Z, Shen Q, Wu X, Zhang D, Xing D. Activation of PKA/SIRT1 signaling pathway by photobiomodulation therapy reduces Aβ levels in Alzheimer's disease models. Aging Cell. (2020) 19:e13054. doi: 10.1111/acel.13054

60. Chen AC, Arany PR, Huang YY, Tomkinson EM, Sharma SK, Kharkwal GB, et al. Low-level laser therapy activates NF-kB via generation of reactive oxygen species in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e22453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022453

61. Suski JM, Lebiedzinska M, Bonora M, Pinton P, Duszynski J, Wieckowski MR. Relation between mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS formation. In: Methods Mol. Biol. (2012) 810:183–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_12

62. Ferraresi C, Hamblin MR, Parizotto NA. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) on muscle tissue: performance, fatigue and repair benefited by the power of light. Photonics Lasers Med. (2012) 1:267–86. doi: 10.1515/plm-2012-0032

63. Ferraresi C, Kaippert B, Avci P, Huang YY, de Sousa MV, Bagnato VS, et al. Low-level laser (light) therapy increases mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP synthesis in C2C12 myotubes with a peak response at 3–6 h. Photochem Photobiol. (2015) 91:411–6. doi: 10.1111/php.12397

65. Dubyak GR. Signal transduction by P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (1991) 4:295–300. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.4.295

66. Murad F. Discovery of some of the biological effects of nitric oxide and its role in cell signaling. Biosci Rep. (2004) 24:452–74. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2741-8

67. Popa-Wagner A, Mitran S, Sivanesan S, Chang E, Buga AM. ROS and brain diseases: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Oxidat Med Cell Longev. (2013):963520. doi: 10.1155/2013/963520

68. Spengler RN, Spengler ML, Lincoln P, Remick DG, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Dynamics of dibutyryl cyclic AMP-and prostaglandin E2-mediated suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression. Infect Immun. (1989) 57:2837–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2837-2841.1989

69. Tannenbaum CS, Hamilton TA. Lipopolysaccharide-induced gene expression in murine peritoneal macrophages is selectively suppressed by agents that elevate intracellular cAMP. J Immunol. (1989) 142:1274–80.

70. Prabhakar U, Lipshutz D, Bartus JO, Slivjak MJ, Smith EF III, Lee JC, et al. Characterization of cAMP-dependent inhibition of LPS-induced TNFα production by rolipram, a specific phosphodiesterase IV (PDE IV) inhibitor. Int J Immunopharmacol. (1994) 16:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(94)90054-X

71. Zagotta WN, Siegelbaum SA. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. (1996) 19:235–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001315

72. Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nature reviews. Molec Cell Biol. (2003) 4:733–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm1197

Keywords: photobiomodulation, low-level laser therapy, epilepsy, seizure, mitochodria, oxidative stress

Citation: Cardoso FdS, Gonzalez-Lima F and Coimbra NC (2022) Mitochondrial Photobiomodulation as a Neurotherapeutic Strategy for Epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 13:873496. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.873496

Received: 10 February 2022; Accepted: 23 May 2022;

Published: 16 June 2022.

Edited by:

Jonathan Stone, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Michael Hamblin, University of Johannesburg, South AfricaJohn Mitrofanis, Université Grenoble Alpes, France

Copyright © 2022 Cardoso, Gonzalez-Lima and Coimbra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabrízio dos Santos Cardoso, ZmFicml6aW9zY2FyZG9zb0B5YWhvby5jb20uYnI=; Francisco Gonzalez-Lima, Z29uemFsZXpsaW1hQHV0ZXhhcy5lZHU=

Fabrízio dos Santos Cardoso

Fabrízio dos Santos Cardoso Francisco Gonzalez-Lima

Francisco Gonzalez-Lima Norberto Cysne Coimbra

Norberto Cysne Coimbra