Abstract

Introduction:

Stroke is a significant global health concern, and numerous studies have established a link between depression and an increased risk of stroke. While many investigations explore this link, some overlook its long-term effects. Depression may elevate stroke risk through physiological pathways involving nervous system changes and inflammation. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the association between depression and stroke.

Methodology:

We conducted a comprehensive search of electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and PsycINFO) from inception to 9 April 2023, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. We included all articles assessing the association between different stroke types and depression, excluding post-stroke depression. Two investigators independently extracted data and assessed quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale and Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, utilizing a random-effects model for data synthesis. The primary outcome was the association of depression with stroke, with a secondary focus on the association of antidepressants with stroke.

Results:

The initial search yielded 10,091 articles, and 44 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled analysis revealed a significant association between depression and stroke risk, with an overall hazard ratio of 1.41 (95% CI 1.32, 1.50; p < 0.00001), indicating a moderately positive effect size. Subgroup analyses showed consistent associations with ischemic stroke (HR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.13, 1.50; p = 0.007), fatal stroke (HR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.24, 1.55; p < 0.000001), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.01, 1.76; p = 0.04). The use of antidepressants was associated with an elevated risk of stroke (HR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.05, 1.55; p = 0.01).

Conclusion and relevance:

This meta-analysis indicates that depression moderately raises the risk of stroke. Given the severe consequences of stroke in individuals with depression, early detection and intervention should be prioritized to prevent it.

Systematic review registration:

Prospero (CRD42023472136).

Introduction

Stroke ranks among the primary causes of mortality and functional impairment worldwide (1). Meanwhile, depression is highly prevalent in the general population, with an estimated occurrence of 5.8% among men and 9.5% among women experiencing a major depressive event within a 12-month timeframe (2). Prior studies suggest a correlation between major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms and an increased risk of developing any form of stroke (3, 4). Numerous investigations have explored the connection between depression and stroke, with some focusing solely on the initial measurements of depression or depressive symptoms as well as potential confounding factors. However, such studies may not adequately capture the long-term implications of depression on the risk of stroke (5). Several potential physiological pathways exist by which depression may elevate the risk of stroke, including neuronal endocrine effects such as the activation of the sympathetic central nervous system and imbalances of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis. Additionally, depression can lead to changes in behavior and have immunological/inflammatory effects, resulting in elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), all of which can contribute to the risk of stroke (6–8). The association between depressive symptoms and an increased risk of stroke in older adults has been well-documented across previous studies, although predominantly evaluated within high-income nations (3, 4, 9, 10). A single study has indicated that the prevalence of heightened depressive symptoms is higher among the Hispanic population (33%) and the Black population (27%) compared to the white population/other groups (18%). Hence, it is important to consider the influence of race/ethnicity when assessing the relationship between depression and stroke (10). Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the relationship between depression and stroke incidence in adults.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive review of the existing literature was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) (11) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. An extensive search was performed across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and PsycINFO, covering the period from inception to 9 April 2023. The search query used was as follows: “(((((((Depression) OR (MeSH Terms: Depressive disorder)) OR (Symptoms of depression)) OR (Major depressive disorder)) AND (Stroke))) OR (Title: Risk of stroke))” to retrieve relevant articles.

Study selection

Two investigators (MSM and MAS) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the identified citations. In cases where the eligibility of a study could not be determined from the abstract alone, a thorough evaluation of the full-text article was conducted. Any disagreements were resolved by a third independent investigator, FA. The articles retrieved from the systematic search were imported into the EndNote reference library, specifically version 20.2 (Clarivate Analytics), and duplicate entries were subsequently removed. The inclusion criteria consisted of Observational Cohorts and Randomized Control trials involving non-institutionalized adults aged 18 years and older. The authors of these studies reported the risk ratio or hazard ratio (HR) of stroke morbidity or mortality in individuals with depression compared to those without depression. Various forms of stroke (complete, fatal, non-fatal, ischemic, and hemorrhagic) were considered, along with different methods, for assessing depression status, such as scales or clinical diagnosis. Studies focusing on post-stroke depression were excluded. Studies focusing on cardiovascular diseases with no stroke data were excluded too. The screening process initially involved reviewing the titles and abstracts of the identified studies, followed by a comprehensive assessment of the full-text articles.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The process of data extraction and quality assessment involved three team members, MAS, MSM, and AM, who followed established protocols. The accuracy of the data was verified by all three members, and any discrepancies were resolved through consultation with a fourth team member. Relevant information was collected from the studies, including study parameters (study name, authors, publication year, study location, duration of follow-up, and participant numbers) and participant characteristics (average age and gender distribution as male or female percentage). The primary focus was on depression, which was assessed through self-stated scales or clinician diagnosis at baseline or subsequent updates. The primary outcome of interest was the risk of stroke, with stroke types identified from self-reports, death records, or medical records. Additionally, the use of antidepressants and their association with stroke were considered during the process of data extraction and analysis. These details were included to explore potential connections between antidepressants and stroke outcomes.

Data synthesis and analysis

The statistical analyses in this study were conducted using RevMan (Version 5.4; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) (12) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software Version 3.3. HRs accompanied by their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as the measure of association, and a random-effects model was utilized to combine the results. Forest plots were generated to visually assess the pooled outcomes. Subgroup differences were evaluated using the chi-square test. HRs were used as the prevailing measure of association across the research studies, with relative risks (RRs) deemed analogous to HRs. When data regarding the overall occurrence of stroke were not available, data pertaining to strokes of ischemic nature, strokes resulting in death, or strokes causing non-survivable outcomes (in sequential order) were utilized as substitutes for the total number of strokes. In cases where studies presented graded relationships (such as mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms), only the estimates for the highest category were taken into consideration. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using Higgins I2, with a value below 50% deemed acceptable. Begg’s test and a visual examination of the funnel plot were conducted to evaluate publication bias. A significance level of p of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Literature search

The initial search yielded a total of 10,091 articles. After removing duplicates (831 records), 9,260 unique records remained for screening. All 9,260 records were evaluated based on their titles and abstracts, resulting in 86 articles for further evaluation. Following a detailed examination, 42 articles were excluded due to various reasons, including failure to meet inclusion criteria and unavailability of relevant data. Ultimately, 44 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics

Among the initially identified articles, a total of 44 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1).

Table 1

| Study name | Country | No. of participants | No of cases | Mean follow-up years | Mean age (years) | Male % | Female % | Duration, y | Depression measures | Stroke measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gilsanz 2017 (5) | USA | 4,319 | 334 | 8.52 | 72.36 (5.23) | 41.63 | 58.37 | 2 | CES-D | Death certificates, neurological images (MRI and CT scan) |

| Meza 2020 (13) | Mexico | 10,693 | 546 | 11.4 (4.2) | 62.3 (9.4) | 45.15 | 54.84 | 2 | CES-D | Clinical diagnosis AND medical records. |

| Ford 2021 (14) | USA | 30,239 | 1,262 | 9.21 (4.0) | 64.5 | 45 | 55 | NA | CES-D | The physician committee independently reviewed medical and death records obtained after a reported or suspected stroke event. |

| Tsai 2017 (15) | Taiwan | 40,645 | 4,550 | 12 | NA | 31.1 | 68.89 | NA | Clinical diagnosis | Death certificates, medical records, and health insurance data. |

| Pan 2011 (16) | USA | 80,574 | 1,033 | 6 | 66 | 0 | 100 | 7 | MHI-5 | National survey of stroke criteria, medical record, and autopsy reports. |

| Sun 2016 (17) | China | 487,377 | 27,623 | 7.2 | 51 | 40.9 | 56.9 | 9 | (DSM)-IV | Death certificates, medical records, and health insurance data. |

| Majed 2012 (18) | Ireland, France | 9,601 | 136 | 5 | 54.98 | 100 | 0 | 10 | CES-D | Follow-up and death certificates. |

| Qiao 2021 (19) | Europe (19 countries) | 78,212 | 2,173 | 12 | NA | 43.1 | 56.38 | 14 | (EDS) | Death certificates and follow-up data. |

| Seifert 2012 (20) | Germany | 3,908 | 156 | 6.13 | NA | 41.19 | 58.77 | 3 | GDS | ICD classification |

| Ellis 2010 (21) | USA | 10,025 | 1,925 | 8 | NA | 43.1 | 56.9 | 5 | CES-D | Death certificates |

| O Brien 2015 (22) | USA | 5,301 | 738 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | 5 | CES-D | Review of death certificates and abstraction of medical records. |

| Henderson 2013 (23) | USA | 4,120 | 603 | 6 | 77.1 (6.3) | 58.2 | 61.4 | 4 | CES-D | Medical records and clinical diagnosis. |

| Glymour 2012 (10) | USA | 18,648 | 1,998 | 3.16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | CES-D | Interviews from patients and relatives. |

| Glymour 2010 (24) | USA | 19,087 | 1854 | 7.5 (3.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA | CES-D | Medical records during follow-up and death certificates. |

| Freak-Poli 2018 (25) | Netherlands | 8,129 | 1,344 | 15 | NA | NA | NA | 21 | CES-D | Follow-up data of clinical diagnosis and medical records. |

| Li 2019 (26) | China | 12,417 | 1,088 | 4 | 58.4 (9.51) | 49.2 | 50.8 | 4 | CES-D | Follow up data. |

| Gafarov 2013 (27) | Russia | 560 | 35 | 16 | NA | 0 | 100 | 15 | The questionnaire MOPSY (subscale D) | NA |

| Daskalopoulou 2016 (28) | UK | 1,937,360 | 94,432 | 6.9 | NA | NA | NA | 13 | Clinical diagnosis | Follow-up and death certificates. |

| Vogt 1994 (29) | USA | 2,573 | NA | 15 | NA | 46.1 | 53.9 | 15 | Depressive Index | Death index or vital records. |

| Everson 1998 (30) | USA | 6,676 | 169 | 29 | 43.4 (15.9) | 45.8 | 44.2 | 29 | HPL depression scale | Death certificates. |

| Jonas 2000 (31) | USA | 6,095 | 483 | 18 | NA | NA | NA | 16 | GDS | Hospital records and death certificates. |

| Larson 2001 (32) | USA | 1,703 | 95 | 13 | NA | NA | NA | 13 | CES-D | Self-reports or death certificate. |

| Ohira 2001 (33) | Japan | 901 | 69 | 10.3 | NA | 35 | 65 | 10.3 | SDS | Death certificate, medical records, or clinical diagnosis. |

| Ostir 2001 (34) | USA | 2,478 | 340 | 6 | NA | 31 | 69 | 6 | CES-D | Clinical diagnosis or death certificate. |

| Wassertheil-Smoller 2004 (35) | USA | 93,676 | 751 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.1 | CES-D and DIS | Self-reports or proxy-reports. |

| Gump 2004 (36) | USA | 11,216 | 167 | 18.4 | 46 | 100 | 0 | 18.4 | CES-D | Death certificates. |

| Kamphuis 2006 (37) | Finland, Italy, Netherlands | 799 | 66 | 10 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 7.4 | SDS | Death certificates. |

| Arbelaez 2007 (38) | USA | 5,525 | 607 | 11 | 42 | 42 | 58 | 11 | CES-D | Medical records and death certificates. |

| Salaycik 2007 (39) | USA | 4,120 | 228 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 8 | CES-D | Clinical diagnosis. |

| Bos 2008 (40) | Netherlands | 4,424 | 291 | 5.8 | 72 | 40 | 60 | 5.6 | CES-D | Self-reports, clinical diagnosis, computed tomographic scan, or hospital records. |

| Liebetrau 2008 (41) | Sweden | 494 | 56 | 3 | 85 | 30 | 70 | 3 | DSMMD-III | Hospital discharge register, death certificates, self-reports, and key informants. |

| Surtees 2008 (42) | UK | 20,627 | 595 | 8.5 | NA | 45.5 | 54.4 | 8.5 | MHI-5 | Clinical diagnosis or death certificate. |

| Wouts 2008 (43) | Netherlands | 2,965 | 176 | 7.7 | 71 | 48 | 52 | 7.7 | CES-D | Self-reports or general practitioners’ diagnosis. |

| Nabi 2010 (44) | Finland | 23,282 | 129 | 7 | 64 | 41 | 59 | 7 | BDI | Hospital discharge register or mortality records. |

| Wassertheil-Smoller 1996 (45) | USA | 4,736 | 294 | 5 | 72 | 42.9 | 57 | 4.5 | CES-D | Clinical diagnosis or death certificates. |

| Simons 1998 (46) | Australia | 2,805 | 401 | 8.2 | 69 | 44 | 56 | 7 | Clinical Diagnosis | Hospital and death records |

| Whooley 1998 (47) | USA | 7,518 | 473 | 6 | 72 | 0 | 100 | NA | GDS | Death certificates and hospital records |

| May 2002 (48) | Wales | 2,172 | 130 | 14 | 56.8 | 100 | 0 | NA | 30-item GHQ | Death certificates and clinical diagnosis |

| Yasuda 2002 (49) | Japan | 980 | 26 | 7.5 | 72 | 38.8 | 61.1 | 7.5 | 30-item GHQ | Death certificates |

| Sturmer 2006 (50) | Germany | 4,267 | 62 | 8.5 | 53.4 | 48.2 | 51.5 | NA | Clinical diagnosis | Death certificates |

| Kawamura 2007 (51) | Japan | 920 | 158 | 15 | NA | 40.1 | 59.8 | 15 | DSMMD-III | Death certificates and clinical diagnosis |

| Lee 2008 (52) | Taiwan | 4,962 | 98 | 5 | NA | 44 | 56 | 5 | DSMMD-III | Medical records |

| Whooley 2008 (53) | USA | 4,876 | 341 | 4.8 | 67 | 80 | 20 | NA | 9-item PHQ | Hospital records and death certificates |

| Peters 2010 (54) | UK | 2,656 | 97 | 2.1 | NA | 39 | 59 | 6 | GDS | Medical records |

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

NA, Not Available; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MHI-5, The Mental Health Inventory-5; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth edition; EDS, Euro-Depression Scale; GDS, The Geriatric Depression Scale; HPL, Human Population Laboratory Depression Scale; SDS, The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; DSMMD-III, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Third Edition; BDI, Beck’s Depression Inventory; 30-item GHQ, 30-item General Health Questionnaire; PHQ, The Patient Health Questionnaire; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

The selected studies were conducted in different regions, primarily in the United States and European countries, with additional studies conducted in Japan, Australia, Taiwan, and as part of an international collaboration. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 401 to 93,676 participants. The total number of participants and cases were 2,379,274 and 148,389, respectively. The mean follow-up duration was 9.35 ± 5.06 years, and the mean age was 64.01 ± 11.35 years. The subsequent assessment durations varied from 2 to 29 years, allowing for the examination of long-term effects. All the included studies were of high methodological quality, as shown in the risk of bias chart, assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale and Cochrane risk of bias tools (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Assessment of risk of bias by Newcastle–Ottawa scale and Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Depression and risk of stroke

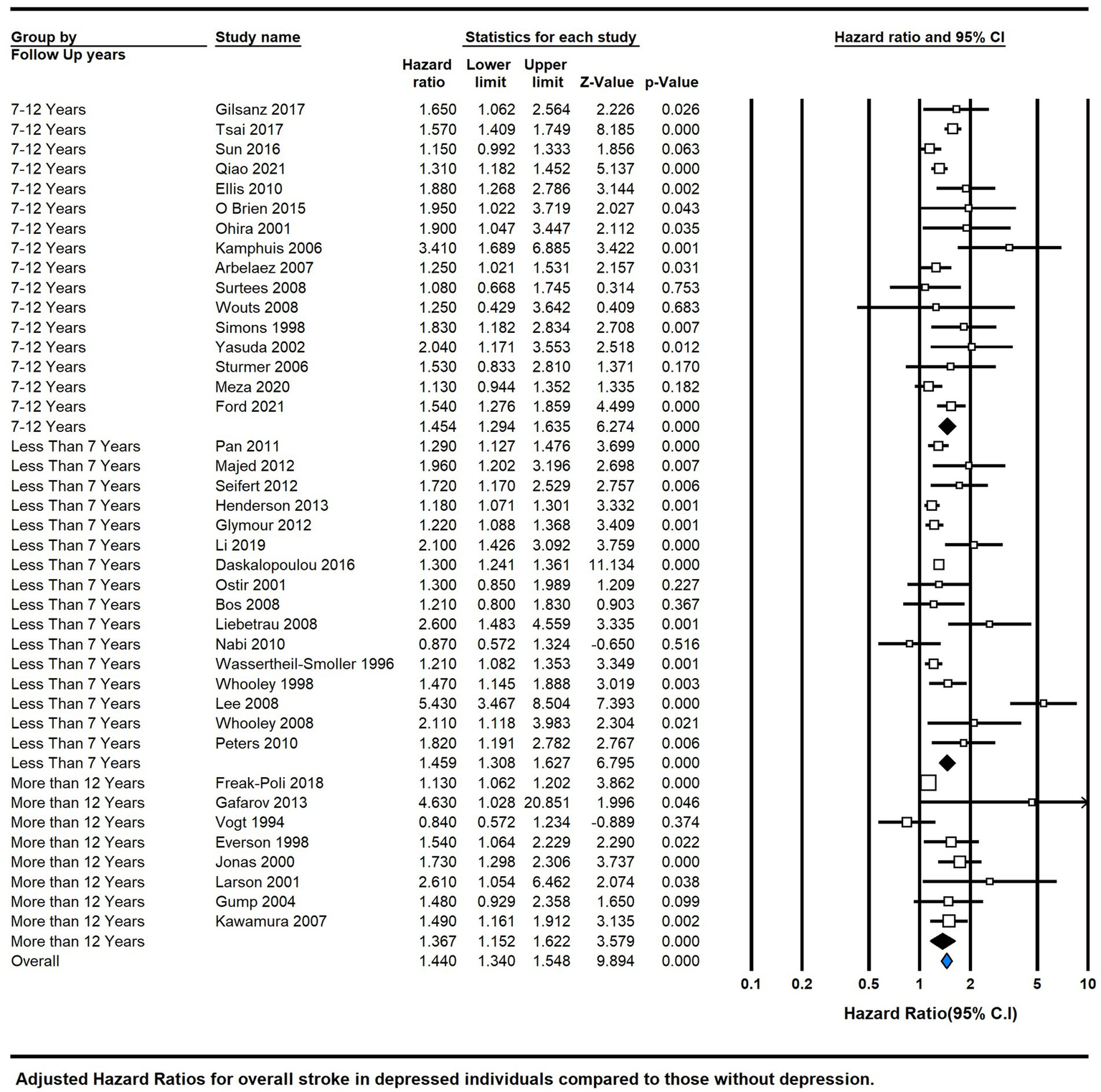

The meta-analysis of depression and the risk of stroke included a total of 44 studies (Figure 3). The pooled analysis revealed a significant association between depression and the risk of stroke, with an overall HR of 1.41 (95% CI 1.32, 1.50; P < 0.00001), indicating a moderate positive effect size. However, the significant heterogeneity among the studies (I^2 = 71%) suggested substantial variability in the effect estimates.

Figure 3

Forest plot of hazard ratios of total stroke for depressed participants compared with non-depressed participants.

Sensitivity analysis

To improve the accuracy and reliability of our research findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the leave-one-out method. This approach allowed us to identify the specific studies that contributed to the heterogeneity and assess their impact on our results. By using this technique, we aimed to enhance the precision of our findings and ensure more dependable outcomes (Supplementary File S1). The HR between stroke and depression was 1.35 (95% CI 1.28, 1.43; p < 0.00001) after sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the association between depression and ischemic stroke, between depression and fatal stroke, and between depression and hemorrhagic stroke (Figure 4). There was no significant difference in the effects of subgroups. The HR between depression and ischemic stroke was 1.30 (95% CI 1.13, 1.50; P = 0.007), between depression and fatal stroke was 1.39(95% CI 1.24, 1.55; P < 0.000001), and between depression and hemorrhagic stroke was 1.33(95% CI 1.01, 1.76; P = 0.04).

Figure 4

Forest plot of subgroup analysis by type of stroke.

The analysis further stratified by follow-up duration: less than 7 years (HR = 1.459, 95% CI 1.308–1.627, p = 0.000, I2 = 78.95), 7–12 years (HR = 1.382, 95% CI 1.310–1.459, P = 0.000, I2 = 57.78), and more than 12 years (HR = 1.178, 95% CI 1.113–1.247, P = 0.000, I2 = 70.899). These findings underline the significance of depression in increasing the risk of diverse stroke types, with the association strength varying based on follow-up duration (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Subgroup analysis by means of follow-up duration.

Use of antidepression medication and stroke

We explored the association between the use of antidepressant medication and stroke. Three studies reported the association, and the overall HR was 1.28 (95% CI 1.05, 1.55; P = 0.01). There was a positive association between the use of antidepressant medication and stroke (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot of hazard ratios between the use of antidepressants and stroke.

Analysis of publication bias

The analysis of the funnel plot (Supplementary File S1) revealed a possible indication of publication bias in the data, and the Eggers test was significant (intercept 1.386; p = 0.00018). Despite the potential presence of publication bias, a trim-and-fill sensitivity analysis was performed, with 13 studies trimmed to assess the robustness of the results. In this case, the results of the trim-and-fill sensitivity analysis showed minimal influence on the findings. Only a slight attenuation, or weakening, of the pooled HR was observed, suggesting that the potential missing studies were unlikely to significantly alter the overall conclusion of the analysis.

Discussion

Our comprehensive meta-analysis, comprising a total of 44 studies, has uncovered a significant association between depression and the risk of stroke (Figure 3). The combined analysis demonstrated an overall HR of 1.41 (95% CI 1.32, 1.50; p < 0.00001), indicating a moderately positive effect size. These findings are in line with a previous meta-analysis published in 2011 (4), which reported adjusted HRs of 1.45 (95% CI, 1.29–1.63) for overall stroke and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.25–1.93) for fatal stroke.

Furthermore, our current meta-analysis provides robust evidence supporting the association between depression and the risks of total stroke, fatal stroke, and ischemic stroke. These results are consistent with the INTERSTROKE study (55), a large case–control study. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between depression and different stroke subtypes, namely ischemic stroke, fatal stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke (Figure 4). Interestingly, no significant differences in the effects were observed among these subgroups, suggesting that the association between depression and stroke may not vary substantially based on the stroke subtype.

It is important to note that three studies (33, 38, 40) reported findings on ischemic stroke, with two studies (33, 38) indicating a significantly increased risk, while one study (33) reported no association with hemorrhagic stroke.

Our analysis revealed an elevated risk of stroke associated with the use of antidepressant medication, with an overall HR of 1.28 (95% CI 1.05, 1.55; p = 0.01). These findings are consistent with previous observational studies (56, 57), suggesting a possible link between antidepressant use and stroke, which included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), with the risk of ischemic, hemorrhagic, and fatal stroke being higher in SSRIs. However, caution should be exercised when interpreting these findings due to potential confounding factors, such as the severity of depression.

Moreover, age and cardiac disease status were identified as potential modifiers in the association between depression and stroke. In one study (39), depression was significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke only in individuals aged 65 years or younger. Additionally, potential mechanisms underlying the association between depression and stroke were explored. MRI scans have revealed that deep white matter lesions are more frequently observed in older individuals with depression (senile depression) compared to those without depression (58, 59). Furthermore, patients who experience depression at a younger age (presenile-onset depression) exhibit a higher incidence of silent cerebral infarctions, regardless of the specific subtypes of depression (60).

Other established susceptibility factors for stroke, including age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, education, and history of cardiovascular events, were thoroughly considered. Notably, cardiac disease serves as a significant contributor to stroke, and depression in patients suffering from cardiovascular disorders may exacerbate the underlying atherosclerotic disease, potentially leading to stroke (43). Detrimental lifestyle elements, such as smoking (61) and reduced exercise levels (62), which themselves increase the risk of depression, were also found to be associated with depression.

Furthermore, inflammatory markers such as CRP, IL-1, and IL-6 have shown positive associations with depression in both clinical and community samples (6). The magnitude of the association between depression and stroke observed in our study is comparable to the associations between smoking and stroke (63).

The potential occurrence of reverse causality should be carefully considered when examining the association between depression and stroke, since some studies have suggested that a history of stroke might enhance the likelihood of developing depression (64). It is possible that certain studies may have overlooked prior stroke incidents that could have led to both depression and subsequent stroke episodes. Furthermore, apart from the studies included in our meta-analysis, several other studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria have also reported a positive association between depression and stroke. For example, Simonsick et al. (65) observed significantly higher rates of stroke incidence in subgroups of older adults with hypertension exhibiting high depressive symptoms compared to non-depressed individuals. Similarly, Nilsson and Kessing et al. (66) found increased future stroke risk among hospitalized patients with severe depression in comparison to patients with osteoarthritis.

Moreover, it is important to note that further research is necessary to investigate the association between depression and stroke in non-Caucasian populations. One study revealed a relatively high prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms among the Caucasian population, the Hispanic population, and the Black population, with Hispanics having the highest occurrence (10). This finding highlights the need for comprehensive studies encompassing diverse populations to gain a better understanding of the relationship between depression and incident stroke.

Strength and limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in our meta-analysis. First, significant heterogeneity was observed across the included studies, likely stemming from variations in study designs, sample sizes, measures of depression and stroke, analysis approaches, and participant characteristics. Although moderate to high heterogeneity persisted in several subgroups, the pooled HRs consistently indicated positive associations. The primary contributors to the heterogeneity were three specific studies (15, 25, 52) that had distinct participant criteria, such as age restrictions and inclusion of rheumatoid arthritis patients. A sensitivity analysis was conducted for these studies, and the forest plot can be found in Supplementary File S1. Furthermore, the analysis of the funnel plot indicated the potential presence of publication bias. However, when conducting the trim-and-fill sensitivity analysis, the results were minimally affected, with only a slight attenuation observed in the pooled HR. One notable strength of our study lies in its extensive inclusion of 44 studies, surpassing the number of studies incorporated in previous meta-analyses. This comprehensive analysis provides compelling evidence concerning the association between depression and the increased risk of stroke.

Another potential limitation of this study is the absence of a separate analysis based on gender. Due to the lack of available data in the existing literature, we were unable to conduct gender-specific analyses. This omission is significant considering the widely suggested notion of a female preponderance in depression, which is deemed universal and substantial. Previous studies have established this association (67, 68). Hence, it is imperative for future research endeavors to delve deeper into the relationship between depression, gender, and the risk of stroke, as understanding these dynamics could yield valuable insights into preventive strategies and tailored interventions.

Conclusion

In summary, our exhaustive meta-analysis strongly establishes the association between depression and an increased risk of stroke, validating earlier findings and indicating potential involvement across various stroke subtypes. Furthermore, our study highlights a significant association between heightened stroke risk and the use of antidepressant medication. Moving forward, further research is essential to unravel the underlying mechanisms of this connection and deepening our understanding of the intricate interrelationship between depression and stroke. Additionally, investigations into effective interventions for reducing stroke risk in individuals with depression are crucial while simultaneously scrutinizing the role of antidepressants in this context, encompassing their impact on stroke risk and associated mechanisms. This comprehensive approach aims to provide a holistic viewpoint on this complex issue.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

FA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. MM: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. MSh: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. AH: Writing – original draft, Data curation. AM: Writing – original draft. AN: Writing – original draft. BS: Writing – original draft. FK: Writing – original draft. MS: Writing – original draft. JI: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1331300/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Johnson W Onuma O Owolabi M Sachdev S . Stroke: a global response is needed. Bull World Health Organ. (2016) 94:634–634A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.181636

2.

Levav I Rutz W . The WHO world health report 2001 new understanding--new hope. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. (2002) 39:50–6. PMID:

3.

Dong JY Zhang YH Tong J Qin LQ . Depression and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke. (2012) 43:32–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.630871

4.

Pan A Sun Q Okereke OI Rexrode KM Hu FB . Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA. (2011) 306:1241–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1282

5.

Gilsanz P Kubzansky LD Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ Wang Q Kawachi I Patton KK et al . Changes in depressive symptoms and subsequent risk of stroke in the cardiovascular health study. Stroke. (2017) 48:43–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013554

6.

Howren MB Lamkin DM Suls J . Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. (2009) 71:171–86. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b

7.

Kaptoge S Di Angelantonio E Lowe G Pepys MB Thompson SG Collins R et al . C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. (2010) 375:132–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7

8.

Shimbo D Chaplin W Crossman D Haas D Davidson KW . Role of depression and inflammation in incident coronary heart disease events. Am J Cardiol. (2005) 96:1016–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.064

9.

Gilsanz P Walter S Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ Patton KK Moon JR Capistrant BD et al . Changes in depressive symptoms and incidence of first stroke among middle-aged and older US adults. J Am Heart Assoc. (2015) 4:4–5. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001923

10.

Glymour MM Yen JJ Kosheleva A Moon JR Capistrant BD Patton KK . Elevated depressive symptoms and incident stroke in Hispanic, African-American, and white older Americans. J Behav Med. (2012) 35:211–20. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9356-2

11.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

12.

Review manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. Denmark: The Cochrane Collaboration (2020).

13.

Meza E Eng CW Sáenz JL Gilsanz P Glymour MM Torres JM . Elevated depressive symptoms and the risk of stroke among the Mexican older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68:2579–86. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16718

14.

Ford CD Gray MS Crowther MR Wadley VG Austin AL Crowe MG et al . Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke in a National Cohort of black and white participants from REGARDS. Neurol Clin Pract. (2021) 11:e454–61. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000983

15.

Tsai TY Lu MC Livneh H Chiu SY Lai NS Guo HR . Does depression increase the risk of stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e014233. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014233

16.

Pan A Okereke OI Sun Q Logroscino G Manson JE Willett WC et al . Depression and incident stroke in women. Stroke. (2011) 42:2770–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.617043

17.

Sun J Ma H Yu C Lv J Guo Y Bian Z et al . Association of Major Depressive Episodes with Stroke Risk in a prospective study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Stroke. (2016) 47:2203–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013512

18.

Majed B Arveiler D Bingham A Ferrieres J Ruidavets JB Montaye M et al . Depressive symptoms, a time-dependent risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in middle-aged men: the PRIME study. Stroke. (2012) 43:1761–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.645366

19.

Qiao Y Liu S Li G Lu Y Wu Y Ding Y et al . Role of depressive symptoms in cardiometabolic diseases and subsequent transitions to all-cause mortality: an application of multistate models in a prospective cohort study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. (2021) 6:511–8. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000693

20.

Seifert CL Poppert H Sander D Feurer R Etgen T Ander KH et al . Depressive symptoms and the risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly—influence of age and sex. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e50803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050803

21.

Ellis C Zhao Y Egede LE . Depression and increased risk of death in adults with stroke. J Psychosom Res. (2010) 68:545–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.11.006

22.

O'Brien EC Greiner MA Sims M Hardy NC Wang W Shahar E et al . Depressive symptoms and risk of cardiovascular events in blacks: findings from the Jackson heart study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2015) 8:552–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001800

23.

Henderson KM Clark CJ Lewis TT Aggarwal NT Beck T Guo H et al . Psychosocial distress and stroke risk in older adults. Stroke. (2013) 44:367–72. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.679159

24.

Glymour MM Maselko J Gilman SE Patton KK Avendaño M . Depressive symptoms predict incident stroke independently of memory impairments. Neurology. (2010) 75:2063–70. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d70e

25.

Freak-Poli R Ikram MA Franco OH Hofman A Tiemeier H . Depressive symptoms prior to and after incident cardiovascular disease and long-term survival. A population-based study of older persons. Depress Anxiety. (2018) 35:18–31. doi: 10.1002/da.22689

26.

Li H Zheng D Li Z Wu Z Feng W Cao X et al . Association of Depressive Symptoms with Incident Cardiovascular Diseases in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e1916591. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16591

27.

Gafarov VV Panov DO Gromova EA Gagulin IV Gafarova AV . The influence of depression on risk development of acute cardiovascular diseases in the female population aged 25-64 in Russia. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2013) 72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21223

28.

Daskalopoulou M George J Walters K Osborn DP Batty GD Stogiannis D et al . Depression as a risk factor for the initial presentation of twelve cardiac, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial diseases: data linkage study of 1.9 million women and men. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0153838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153838

29.

Vogt T Pope C Mullooly J Hollis J . Mental health status as a predictor of morbidity and mortality: a 15-year follow-up of members of a health maintenance organization. Am J Public Health. (1994) 84:227–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.2.227

30.

Everson SA Roberts RE Goldberg DE Kaplan GA . Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Arch Intern Med. (1998) 158:1133–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1133

31.

Jonas BS Mussolino ME . Symptoms of depression as a prospective risk factor for stroke. Psychosom Med. (2000) 62:463–71. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00001

32.

Larson SL Owens PL Ford D Eaton W . Depressive disorder, dysthymia, and risk of stroke: thirteen-year follow-up from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area study. Stroke. (2001) 32:1979–83. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.094623

33.

Ohira T Iso H Satoh S Sankai T Tanigawa T Ogawa Y et al . Prospective study of depressive symptoms and risk of stroke among Japanese. Stroke. (2001) 32:903–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.903

34.

Ostir GV Markides KS Peek MK Goodwin JS . The association between emotional well-being and the incidence of stroke in older adults. Psychosom Med. (2001) 63:210–5. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00003

35.

Wassertheil-Smoller S Shumaker S Ockene J Talavera GA Greenland P Cochrane B et al . Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. The Women's Health Initiative (WHI). Arch Intern Med. (2004) 164:289–98. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.289

36.

Gump BB Matthews KA Eberly LE Chang YF . Depressive symptoms and mortality in men: results from the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Stroke. (2005) 36:98–102. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149626.50127.d0

37.

Kamphuis MH Kalmijn S Tijhuis MA Geerlings MI Giampaoli S Nissinen A et al . Depressive symptoms as risk factor of cardiovascular mortality in older European men: the Finland, Italy and Netherlands elderly (FINE) study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. (2006) 13:199–206. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000188242.64590.92

38.

Arbelaez JJ Ariyo AA Crum RM Fried LP Ford DE . Depressive symptoms, inflammation, and ischemic stroke in older adults: a prospective analysis in the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2007) 55:1825–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01393.x

39.

Salaycik KJ Kelly-Hayes M Beiser A Nguyen AH Brady SM Kase CS et al . Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke. (2007) 38:16–21. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251695.39877.ca

40.

Bos MJ Lindén T Koudstaal PJ Hofman A Skoog I Breteler MM et al . Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke: the Rotterdam study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2008) 79:997–1001. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.134965

41.

Liebetrau M Steen B Skoog I . Depression as a risk factor for the incidence of first-ever stroke in 85-year-olds. Stroke. (2008) 39:1960–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490797

42.

Surtees PG Wainwright NW Luben RN Wareham NJ Bingham SA Khaw KT . Psychological distress, major depressive disorder, and risk of stroke. Neurology. (2008) 70:788–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304109.18563.81

43.

Wouts L Oude Voshaar RC Bremmer MA Buitelaar JK Penninx BW Beekman AT . Cardiac disease, depressive symptoms, and incident stroke in an elderly population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2008) 65:596–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.596

44.

Nabi H Kivimäki M Suominen S Koskenvuo M Singh-Manoux A Vahtera J . Does depression predict coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease equally well? The health and social support prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. (2010) 39:1016–24. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq050

45.

Wassertheil-Smoller S Applegate WB Berge K Chang CJ Davis BR Grimm R Jr et al . Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events. Arch Intern Med. (1996) 156:553–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440050111012

46.

Simons LA McCallum J Friedlander Y Simons J . Risk factors for ischemic stroke: Dubbo study of the elderly. Stroke. (1998) 29:1341–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.7.1341

47.

Whooley MA Browner WS . Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in older women. Study of osteoporotic fractures research group. Arch Intern Med. (1998) 158:2129–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.19.2129

48.

May M McCarron P Stansfeld S Ben-Shlomo Y Gallacher J Yarnell J et al . Does psychological distress predict the risk of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack? The Caerphilly study. Stroke. (2002) 33:7–12. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.100529

49.

Yasuda N Mino Y Koda S Ohara H . The differential influence of distinct clusters of psychiatric symptoms, as assessed by the general health questionnaire, on cause of death in older persons living in a rural community of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2002) 50:313–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50064.x

50.

Stürmer T Hasselbach P Amelang M . Personality, lifestyle, and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer: follow-up of population based cohort. BMJ. (2006) 332:1359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38833.479560.80

51.

Kawamura T Shioiri T Takahashi K Ozdemir V Someya T . Survival rate and causes of mortality in the elderly with depression: a 15-year prospective study of a Japanese community sample, the Matsunoyama-Niigata suicide prevention project. J Investig Med. (2007) 55:106–14. doi: 10.2310/6650.2007.06040

52.

Lee HC Lin HC Tsai SY . Severely depressed young patients have over five times increased risk for stroke: a 5-year follow-up study. Biol Psychiatry. (2008) 64:912–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.006

53.

Whooley MA de Jonge P Vittinghoff E Otte C Moos R Carney RM et al . Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. (2008) 300:2379–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.711

54.

Peters R Pinto E Beckett N Swift C Potter J McCormack T et al . Association of depression with subsequent mortality, cardiovascular morbidity and incident dementia in people aged 80 and over and suffering from hypertension. Data from the hypertension in the very elderly trial (HYVET). Age Ageing. (2010) 39:439–45. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq042

55.

O'Donnell MJ Xavier D Liu L Zhang H Chin SL Rao-Melacini P et al . Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. (2010) 376:112–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3

56.

Chen Y Guo JJ Li H Wulsin L Patel NC . Risk of cerebrovascular events associated with antidepressant use in patients with depression: a population-based, nested case-control study. Ann Pharmacother. (2008) 42:177–84. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K369

57.

Smoller JW Allison M Cochrane BB Curb JD Perlis RH Robinson JG et al . Antidepressant use and risk of incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiative study. Arch Intern Med. (2009) 169:2128–39. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.436

58.

Krishnan KR Goli V Ellinwood EH France RD Blazer DG Nemeroff CB . Leukoencephalopathy in patients diagnosed as major depressive. Biol Psychiatry. (1988) 23:519–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90025-X

59.

Coffey CE Figiel GS Djang WT Weiner RD . Subcortical hyperintensity on magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison of normal and depressed elderly subjects. Am J Psychiatry. (1990) 147:187–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.187

60.

Fujikawa T Yamawaki S Touhouda Y . Incidence of silent cerebral infarction in patients with major depression. Stroke. (1993) 24:1631–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.11.1631

61.

Anda RF Williamson DF Escobedo LG Mast EE Giovino GA Remington PL . Depression and the dynamics of smoking. A national perspective. JAMA. (1990) 264:1541–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450120053028

62.

Camacho TC Roberts RE Lazarus NB Kaplan GA Cohen RD . Physical activity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Epidemiol. (1991) 134:220–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116074

63.

Strazzullo P D'Elia L Cairella G Garbagnati F Cappuccio FP Scalfi L . Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta-analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke. (2010) 41:e418–26. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576967

64.

Huang CQ Dong BR Lu ZC Yue JR Liu QX . Chronic diseases and risk for depression in old age: a meta-analysis of published literature. Ageing Res Rev. (2010) 9:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.005

65.

Simonsick EM Wallace RB Blazer DG Berkman LF . Depressive symptomatology and hypertension-associated morbidity and mortality in older adults. Psychosom Med. (1995) 57:427–35. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199509000-00003

66.

Nilsson FM Kessing LV . Increased risk of developing stroke for patients with major affective disorder--a registry study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2004) 254:387–91. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0519-9

67.

Rydberg Sterner T Gudmundsson P Falk H Seidu N Ahlner F Wetterberg H et al . Depression in relation to sex and gender expression among Swedish septuagenarians-results from the H70 study. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0238701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238701

68.

Parker G Brotchie H . Gender differences in depression. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2010) 22:429–36. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.492391

Summary

Keywords

stroke-diagnosis, depression, ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), hemorrhagic stroke

Citation

Ashraf F, Mustafa MS, Shafique MA, Haseeb A, Mussarat A, Noorani A, Sohail Rangwala B, Kashif Rasool F, Siddiq MA and Iqbal J (2024) Association between depression and stroke risk in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15:1331300. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1331300

Received

02 November 2023

Accepted

08 April 2024

Published

25 April 2024

Volume

15 - 2024

Edited by

Tatjana Rundek, University of Miami, United States

Reviewed by

Arijana Lovrencic-Huzjan, Sisters of Charity Hospital, Croatia

Aleksandra Pavlovic, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Ashraf, Mustafa, Shafique, Haseeb, Mussarat, Noorani, Sohail Rangwala, Kashif Rasool, Siddiq and Iqbal.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Ashir Shafique, Ashirshafique109@gmail.com

†ORCID: Muhammad Ashir Shafique, orcid.org/0000-0001-7420-1292

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.