Abstract

Background:

Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) affects ~40% of survivors, hindering recovery. Dual-task training (combining cognitive and motor tasks) may help, but its superiority over single-task training or usual care remains unclear. This study examines whether dual-task training improves cognitive function more than (1) single-task training or (2) usual rehab/control, and whether effects vary by intervention duration.

Methods:

Keywords were used to search Chinese and English databases. The search period was up to 15 October 2023. Randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies comparing the effects of dual-task training and single-task training or blank control on improving cognitive impairment in stroke patients were included and the quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane collaboration’s risk assessment tool. The effect indicators were evaluated based on fixed-effects or random-effects models.

Results:

A total of 15 RCT studies were included. The results of the studies showed that there was a significant difference in mini-mental state examination scores in the dual-task training group compared with the control group (p < 0.0001). At intervention time >6 weeks trail making test-A scores were lower compared with controls (p < 0.00001). After intervention time >4 weeks, there was a significant difference in digit span test-backward scores compared with controls (p = 0.0003). There was a significant difference in digit span test-forward scores compared with controls (p = 0.0001) after >4 weeks of intervention. There was a significant difference in Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores compared with controls in elderly patients with insignificant cognitive deficits post-stroke (p < 0.00001) and patients with significant cognitive impairment following a stroke (p < 0.00001).

Conclusion:

Dual-task training is more effective than conventional rehabilitation in improving PSCI, but the aspects of improvement may be limited by the duration of the intervention, the number and quality of included studies and the differences in cognitive function, motor tasks and so on.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, CRD42023393550.

Introduction

As one of the common chronic diseases, stroke has an acute onset, progresses rapidly and leaves behind various degrees of functional impairment, bringing a significant burden to the patient’s family and even society (1). Research suggests that around 40% of stroke patients will have cognitive impairment (2). Cognitive dysfunction following a stroke affects progress in rehabilitation of other functions and increases the difficulty of care and rehabilitation at home and in hospitals (3).

Currently, conventional cognitive training and exercise aerobic training are inefficient because they require an exclusive programme tailored to the patient’s own medical characteristics (4). Kumar et al. (5) showed that the transcranial magnetic stimulation technique can help in post-stroke cognitive deficits by modulating the functional areas of the patient’s brain through cortical stimulation, but the therapeutic effect is unstable. Computer-assisted cognitive training and virtual reality technology are not widely used in clinical applications due to their need for a certain amount of capital investment.

Dual-task training is a new training modality applied to stroke patients in recent years, which involves performing one functional training task along with two or more other tasks (6). Studies by Choi et al. (7) and De Luca et al. (8) suggest that a dual task of cognitive–motor training combined with audio synchronization may be more effective in improving attention, cognitive flexibility and executive performance.

Previous systematic reviews have examined dual-task training primarily for its impact on motor outcomes, such as gait parameters (9) or combined motor–cognitive effects (10). These reviews focused on motor function rather than cognitive recovery per se, and none specifically isolated the cognitive benefits of dual-task training versus single-task or usual care in stroke survivors. However, the current study does not analyze single-task training or blank control studies separately to clarify whether the effect of dual-task training is superior to single-task training or to a blank control. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether dual-task training is better than single-task training and blank control in improving cognitive impairment in stroke patients using a meta-analysis. The aim is to provide an evidence-based reference for clinical, dual-task training in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in stroke patients.

Stroke phase was not an exclusion criterion. Seven of the 15 included trials enrolled participants in the subacute phase (<6 months post-stroke), three recruited chronic patients (>6 months) and five did not specify disease duration. We deliberately retained studies across all phases because (1) the overall literature pool was small and further exclusion would compromise statistical power and generalisability, and (2) our primary objective was to determine whether cognitive–motor dual-task training improves cognitive outcomes relative to usual care or single-task training irrespective of stroke chronicity. Nevertheless, the predominance of participants at a subacute phase should be noted as this window is considered critical for cognitive recovery.

Methods

Literature search

The search strategy followed the PRISMA 2020 statement. Computer searches were conducted using the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Biomedical Literature Database and Wanfang Data databases. The search was available until June 1, 2023, in both Chinese and English. The intervention was dual-task training, the disease type was stroke and the study type was randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The search strategy included both the Chinese and the English languages.

The search terms were as follows: (Strokes OR Cerebrovascular Apoplexy OR Apoplexy, Cerebrovascular OR Cerebrovascular Stroke OR Cerebrovascular Strokes OR Stroke, Cerebrovascular OR Strokes, Cerebrovascular OR Apoplexy OR Cerebral Stroke OR Cerebral Strokes OR Stroke, Cerebral OR Strokes, Cerebral) AND (Cognitions OR Cognitive Function OR Cognitive Functions OR Function, Cognitive OR Functions, Cognitive) AND (dual task OR dual-task OR cognitive task OR cognitive-task OR concurrent task OR cognitive motor OR cognitive-motor OR motor cognitive OR motor-cognitive OR second task OR additional task).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Participants: Diagnosed with stroke and confirmed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging; age and gender were not limited.

-

Intervention: Dual-task training (including a cognitive task) in the experimental group.

-

Control: Other conventional rehabilitation treatments, also combined with physical physiological factor therapy.

-

Outcome indicators: These included the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) (11), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (11), Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A), Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT) and Digit Span Test (DST). For details see Table 1 (11–15).

-

Research method: RCT.

-

Language: Chinese and English.

Table 1

| Scale | Domains assessed | Score range/cut-off | Interpretation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | Orientation, memory, attention, language, visuospatial | 0–30; < 24 indicates cognitive impairment | Global cognitive screening | (11) |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Executive function, memory, language, visuospatial, attention | 0–30; < 26 indicates mild cognitive impairment | More sensitive than MMSE for mild deficits | (11) |

| Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A) | Processing speed, visual attention | Time to completion (seconds); higher = worse | Measures cognitive flexibility and attention | (12) |

| Stroop Color–Word Test (word sub-task) | Selective attention, inhibition | Seconds or errors; higher = worse | Assesses executive inhibition | (13) |

| Digit Span Test-Backward (DST-B) | Working memory | 0–14 digits recalled; higher = better | Verbal working memory capacity | (14) |

| Digit Span Test-Forward (DST-F) | Short-term memory | 0–16 digits recalled; higher = better | Verbal short-term memory | (15) |

Outcome indicators: all trials had to report at least one of the following validated cognitive scales.

The exclusion criteria included the following:

-

Conference papers.

-

Inability to extract valid ending data from the text.

-

Duplicate literature.

-

Systematic reviews.

Seven records were excluded because their full texts could not be accessed. These comprised conference abstracts with image-only PDFs lacking selectable text, subscription-protected journal articles for which our library has no license, one Wanfang Data record with a URL that returned a persistent 404 error, a Journal of Physical Therapy Science paper with an online appendix hosting the required data that was no longer available and two Korean conference papers that were only available in print.

Literature screening and data extraction

Two investigators independently screened the literature, extracted data and cross-checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If disagreements emerged, they were resolved through discussion or negotiation with a third party. Data extracted in this meta-analysis included title, first author, year of publication, sample size, intervention, duration of intervention and relevant outcome indicators.

Literature quality evaluation

Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane-recommended RCT risk of bias assessment tool and cross-checked the results. The evaluation items of the tool include the following seven areas: generation of randomized sequences; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and implementers; blinding of outcome assessments; completeness of outcome data; selective reporting of findings; and other sources of bias (other sources of bias items were excluded from this study).

Statistical analysis

The data included in the study were quantitatively analyzed using RevMan v5.4 software. Successive results in the same units were analyzed using mean difference (MD); in all other cases, standardised mean difference (SMD) was used. Uncertainties are presented as 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using I2; for I2 ≤ 50%, p ≥ 0.1, heterogeneity was small and a fixed-effects model was used; for I2 > 50%, p < 0.1, a random-effects model was used; and for I2 > 75%, p < 0.1, heterogeneity was large and sensitivity or subgroup analysis was used. The Egger and Begg tests were used for publication bias. The level of significance α = 0.05. The sample size of this study was less than 10 articles, meaning only subjective publication bias analysis was conducted.

Results

Literature screening process and results

A total of 748 pieces of related literature were obtained, and 15 articles were finally included by screening the literature quality, language, type, title, abstract, outcome indicators, duplication or not and access to the original text. The literature screening process and results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Literature screening process.

Basic characteristics of included studies and risk of bias results

The basic characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2 (16–30). The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was used to evaluate the quality of the literature, with the results shown in Figure 2.

Table 2

| Inclusion of studies | Sample size | Intervention | Frequency | Times | Outcome indicator | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | CG | EG | ||||

| Wang et al. (16) | 36 | 36 | Routine rehabilitation and proprioceptive training | Cognitive-motor dual-task training. | 40 min/times, 5 times/w | 8w | MoCA |

| Fu et al. (17) | 66 | 65 | Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and basic cognitive training | Addition of cognitive-motor control dual-task training to control group treatment | rTMS:15 ~ 20 min, Once a day, 4–5 days a week exercise: Once a day for an hour. | 4w | MoCA, Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT) |

| Yan (18) | 40 | 40 | Resistance-based rehabilitation | Addition of cognitive-motor control dual-task training to control group treatment | 30 min at a time, once a day, 5 times a week | 12w | MoCA, Trail Marking Test (TMT) |

| Yang (19) | 99 | 99 | Dual Task Training Therapy | Trained in hyperbaric-assisted dual-tasking | One hour at a time, once a day, 5 times a week | 4w | MMSE, MoCA |

| Yang and Wang (20) | 20 | 20 | Routine single-task rehabilitation | Cognitive-motor dual-task training | 2 times a day, 5 times a week | 2w | MMSE, MoCA, DS, SDMT, TMT-A |

| Qin et al. (21) | 53 | 53 | Routine treatment and routine neurosurgical care | Cognitive-Otago motor control dual task training | 90 min a day, once a day, 7 times a week | 90d | MoCA |

| Zhu et al. (22) | 38 | 38 | Health education and routine treatment | Perform a simplified version of Otago’s cognitive-motor dual-task training that combines movement and music. | One hour at a time. 2 times per week | 90d | MoCA-BJ and Trail Marking Test, (TMT-A) |

| Fu et al. (23) | 15 | 15 | General rehabilitation training such as balance, | Dual-task training | 6 times/week, 40–50 min/time. | 3w | MMSE |

| Li et al. (24) | 31 | 31 | Exercise Rehabilitation Therapy and Cognitive Rehabilitation Training | Motor rehabilitation therapy and cognitive rehabilitation dual-task training plus AMST training: using an interactive metronome | 3 times per week, 30 min/trip. | 6w | TMT, Digital Span Test (DST), Stroop test |

| Kim et al. (25) | 10 | 10 | Routine rehabilitation training | Dual-task gait training and cognitive tasks | 5 days a week | 4 w | Stroop test |

| Choi et al. (26) | 10 | 10 | Balance training with balance boards | Dual Task is simultaneous balance and cognitive training using BioRescue | 30 min per day, 5 days per week, | 4w | MMSE |

| Park and Lee (27) | 15 | 15 | Only 3 CMDTs per week | Received CMDT + AMST 3 times per week | 3 times per week | 6w | TMT, DST, Stroop test (ST) |

| An and Kim (28) | 15 | 15 | Perform 20 min of single-task training and receive 10 min of regular occupational therapy | 20 min of dual-task training and receive 10 min of regular occupational therapy | 30 min each time, 5 times a week | 5w | DST-B, DST-F, EFPT-K, K-TMT-e B |

| Park and Lee (29) | 15 | 15 | Traditional occupational therapy | Dual-task training using different cognitive tests | 18 interventions of 30 min each, 3 times per week | 6w | TMT-A, TMT-B DST-F, DST-B, Stroop test (ST) |

| Sun et al. (30) | 20 | 20 | Individualised multi-disciplinary progressive training programme | Patients in the CMDT group received both cognitive and motor training | Complete 40 min of training per day, 5 days per week | 4w | MMSE, MoCA |

Table of general characteristics.

EG indicates experimental group and CG indicates control group.

Figure 2

Cochrane risk of bias assessment results map.

Meta-analyzes results

A total of five RCTs used the MMSE as an outcome indicator, including 328 patients. Since I2 = 41%, a fixed-effects model was selected for meta-analysis, which showed better improvement in MMSE scores in the dual-task group relative to the control group (MD = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.75, 1.20, p < 0.0001) (see Figure 3a).

Figure 3

Graph of meta-analysis results (a) MMSE, (b) MOCA, (c) TMT-A, (d) ST-word, (e) DST-B, (f) DST-F.

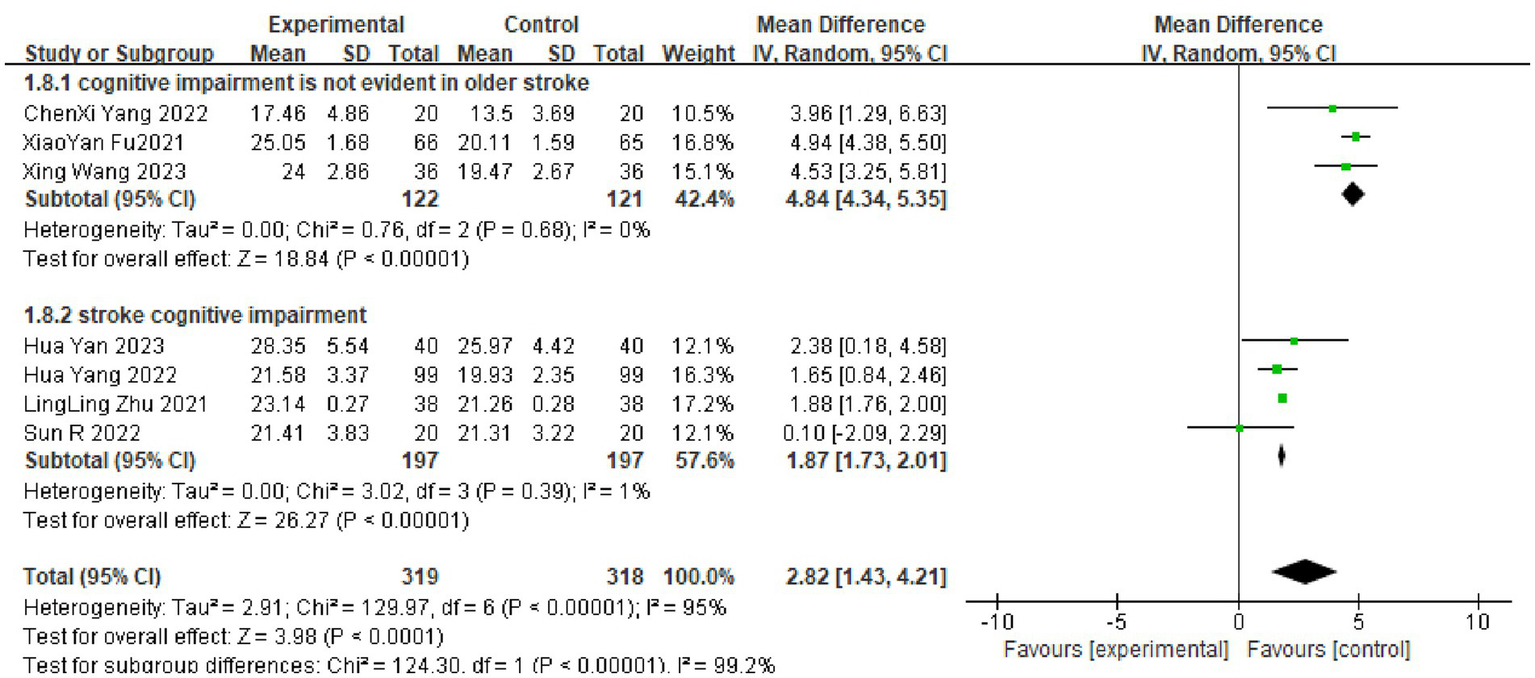

A total of eight RCTs used the MoCA as an outcome indicator, including 743 patients. Given that I2 = 95%, with large heterogeneity among the results, a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed higher scores in the dual-task group compared with the control group (MD = 2.84, 95%CI: 1.73, 3.94, p < 0.0001) (see Figure 3b).

A total of five RCTs used the TMT-A trial as an outcome indicator, including 236 patients. Since I2 = 88%, with large heterogeneity among the results, a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed better improvement in the dual-task group compared with the control group (MD = −16.01, 95%CI: −31.84, −0.19, p = 0.05) (see Figure 3c).

A total of three RCTs used the ST-word test as an outcome indicator, including 122 patients. Given that I2 = 33%, a fixed-effects model was chosen for meta-analysis, which showed that there was no significant difference in ST-word test scores of the dual-tasking group relative to the control group (MD = −7.28, 95%CI: −15.13, 0.58, p = 0.07) (see Figure 3d).

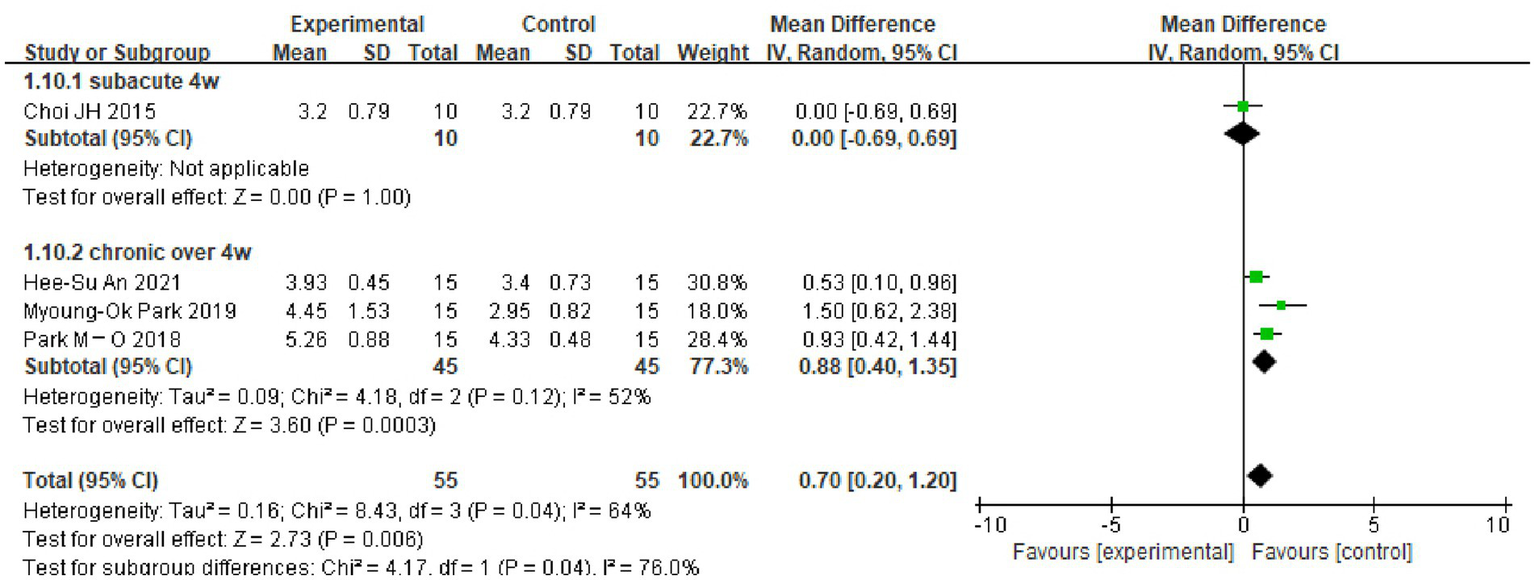

A total of four RCT trials used the DST-backward (DST-B) test as an outcome indicator, including 110 patients. Since I2 = 64%, a random-effects model was selected for meta-analysis, which showed that there was a significant difference in DST-B scores of the dual-tasking group relative to the control group (MD = 0.70, 95%CI: 0.20, 1.20, p = 0.006) (see Figure 3e).

A total of four RCTs used the DST-forward (DST-F) test as an outcome indicator, including 110 patients. Here, I2 = 55%, and a random-effects model was thus used for meta-analysis, which showed no significant difference in DST-F scores of the dual-tasking group relative to the control group (MD = 0.56, 95%CI: −0.14, 1.27, p = 0.12) (see Figure 3f).

Subgroup analysis

Due to the high heterogeneity of the results for the MoCA scores (I2 = 95%), the TMT-A test (I2 = 88%) and the DSTs (I2 = 64%, I2 = 55%), the sources of heterogeneity were further analyzed to consider possible reasons, such as the type of disease, the degree of cognitive impairment, the duration of the disease and the timing of the intervention. The TMT-A and DSTs were analyzed in subgroups according to the duration of the dual-task intervention, and the MoCA scores were analyzed in subgroups according to the type of disease and the degree of cognitive impairment. The results showed the following. (1) There was no significant difference in TMT-A scores between the dual-task group and the control group at 6 weeks of intervention time (MD = 0.09, 95%CI: −13.16, 13.33, p = 0.99), but at >6 weeks of intervention time (MD = −33.57, 95%C1: −46.08, −21.05, p < 0.00001), the TMT-A scores were lower compared with the control group (see Figure 4). (2) The dual-task group had a significant difference in DST-B scores compared with the control group after >4 weeks of intervention (MD = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.40, 1.35, p = 0.0003) (see Figure 5). (3) The dual-task group had a significant difference in DST-F scores compared with the control group after >4 weeks of intervention (MD = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.46, 1.45, p = 0.0001) (see Figure 6). (4) In elderly patients with minor cognitive impairment post-stroke, there was a significant difference in the MoCA score dual-task group compared with the control group (MD = 4.84, 95%CI: 4.34, 5.35, p < 0.00001). In patients with significant cognitive impairment post-stroke, the MoCA score was higher in the dual-task group compared with the control group (MD = 1.87, 95%CI: 1.73, 2.01, p < 0.00001) (see Figure 7).

Figure 4

Graph of the results of TMT-A subgroup analyzes.

Figure 5

Plot of DST-B test subgroup analysis results.

Figure 6

![Forest plot comparing experimental and control groups with subcategories for "subacute 4w" and "chronic over 4w." Mean differences and confidence intervals are shown for each study. Overall mean difference is 0.83 [0.37, 1.29], with heterogeneity statistics provided. The plot uses black diamonds and green squares to illustrate results.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1417364/xml-images/fneur-16-1417364-g006.webp)

Plot of DST-F test subgroup analysis results.

Figure 7

Graph of results of MOCA scale subgroup analyzes.

Publication bias

When there are fewer than 10 included studies for meta-analysis of outcome metrics, publication bias analyzes using funnel plots are not recommended, and only subjective publication bias analyzes were, therefore, performed. The small sample size of the included RCTs in this study may have led to a greater risk of publication bias. The inclusion of studies in Chinese and English only, and the exclusion of studies in other languages may also have resulted in some publication bias.

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that cognitive–motor dual-task training consistently improves global cognition, executive function and working memory in stroke survivors compared with usual rehabilitation or single-task training, with benefits becoming apparent after 4–6 weeks of intervention.

Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) is an important cause of long-term disability and reduced quality of life in stroke patients, with approximately half of patients experiencing cognitive impairment in the first year following a stroke (31). Impairments may affect multiple cognitive domains, including information processing, working memory, executive functioning and attention (32, 33). Currently, medication and rehabilitation are the main clinical treatments for cognitive decline associated with PSCI (34). The effects of dual-task training on PSCI were examined. Due to the small sample size and the lack of clarity regarding the results of the intervention, this study aimed to clarify the therapeutic effect of dual-task training on PSCI.

The results of the meta-analyzes showed significant differences in MMSE scores, MoCA scores, TMT-A test scores and DST-B scores in the dual-task group compared with the conventional group. This suggests that cognitive–motor dual-task training is more effective than conventional cognitive training in improving cognitive deficits post-stroke.

The MoCA scale is suitable for screening for mild cognitive impairment post-stroke and has a good ability to detect aspects of executive functioning that are consistent with the cognitive impairment characteristics of PSCI (35). The MMSE is comparable to the MoCA scale for the detection of PSCI, but the MMSE lacks sensitivity for the detection of mild cognitive dysfunction (36) and does not cover a comprehensive enough cognitive domain (37). This study found that both dual-task groups scored better than the control group. It has been shown that the main mechanism of PSCI is caused by stroke leading to lesions such as microhaemorrhage and edema in key areas, such as the hippocampus or cerebral white matter, which causes disruption of neuronal synaptic structure and function in brain regions (38). Park and Lee (27) showed that cognitive–motor dual-task training shortened the reaction time of central nervous system neurons and significantly increased the oxygenation rate of the frontal lobe, thereby improving cognitive performance.

Learning memory impairment is the main symptom of impaired cognitive function post-stroke (39). The DST is commonly used to measure verbal short-term memory and working memory. Studies have applied cognitive–motor dual-task training to the functional training of stroke patients and found that this method not only improved the patients’ walking resistance but also improved executive and memory functions (24, 40). This is in line with the results of the present study, with the DST-F and DST-B scores significantly different in the dual-task group compared with the conventional group after >4 weeks of intervention. The development of cognitive deficits post-stroke is associated with a reduction in the number of synapses and a decrease in the density of connections in hippocampal neurons (41). Dual-task executive function training increases not only hippocampal volume but also cortical area, especially in the prefrontal lobe, through high-intensity training (39).

Executive function is a control mechanism of the brain that includes processes such as planning, initiating, organising, inhibiting, problem solving, self-monitoring and error correction. Approximately 75% of stroke survivors experience executive dysfunction (4). Executive dysfunction reduces the ability to regain independence in activities of daily living. The TMT is a test of executive functioning and attention that focuses on rapid visual search, visuospatial ordering and cognitive orientation transfer. The Stroop Colour and Word Test (SCWT), a widely used measure of executive function, and its operation requires the synergistic action of multiple cognitive functions of the patient, including short-term memory, stereotype switching and attention (42, 43). The effectiveness of conventional cognitive rehabilitation methods in the treatment of patients with executive dysfunction is controversial. Chung et al. (4) found that cognitive rehabilitation intervention was not effective in patients with executive dysfunction. The results of the present study. Showed a difference in TMT-A results compared with the control group at >6 weeks of intervention. Danneels et al. (44) found that dual-task training had an effect on the executive function, memory and visuospatial ability of patients through a dual-task training study combining two forms of postural control with different cognitive tasks, both static and dynamic. This difference may be related to the timing of the intervention, and the specific execution of the cognitive–motor dual-task, including different cognitive activities, with the choice of motor activities also affecting the dual-task training effect due to the different effects of the dual-task interference they create (45, 46). In examining the immediate effects of dual-task obstacle crossing and single-task obstacle crossing training on the functional and cognitive abilities of chronic ambulatory participants with spinal cord injury, Amatachaya et al. (47) found that there was no significant difference in the percentage of errors in SCWT tasks in the dual-task group as compared with the conventional group, which is in line with the results of the present study. Due to the limitations of the number of participants and the duration of the intervention, the results need to be further validated in a large number of clinical trials.

Conclusion

In summary, cognitive–motor dual-task training is not only a promising adjunct but a clinically superior approach for remediating PSCI when compared with conventional single-task or usual care. The evidence indicates that commencing dual-task programmes within the subacute phase, and continuing them for at least 6 weeks, yields meaningful gains across global cognition, executive function and working memory. These benefits are robust, independent of stroke chronicity and attainable with readily available clinical resources. We therefore recommend that dual-task protocols be routinely integrated into standard stroke rehabilitation pathways and prioritised in future clinical guidelines.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XG: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by Hebei Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital Category Research Program Subjects; titled “Clinical study on the rehabilitation efficacy and neural network mechanism of acupuncture combined with transcranial direct current stimulation on lateral neglect after stroke” (serial number: 2021168).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Liu K Yin M Cai Z . Research and application advances in rehabilitation assessment of stroke. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B Biomed Biotechnol. (2022) 23:625–41. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2100999

2.

McKevitt C Fudge N Redfern J Sheldenkar A Crichton S Rudd AR et al . Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke. (2011) 42:1398–403. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598839

3.

Gibson E Koh CL Eames S Bennett S Scott AM Hoffmann TC et al . Occupational therapy for cognitive impairment in stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2022) 3:CD006430. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006430.pub3

4.

Chung CS Pollock A Campbell T et al . Cognitive rehabilitation for executive dysfunction in adults with stroke or other adult non-progressive acquired brain damage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 2013:CD008391. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008391.pub2

5.

Kumar S Singh S Chadda RK Durward BR Hagen S . The effect of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation at orbitofrontal cortex in the treatment of patients with medication-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a retrospective open study. J ECT. (2018) 34:e16–9. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000462

6.

He Y Yang L Zhou J Yao L Pang MYC . Dual-task training effects on motor and cognitive functional abilities in individuals with stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. (2018) 32:865–77. doi: 10.1177/0269215518758482

7.

Choi W Lee G Lee S . Effect of the cognitive-motor dual-task using auditory cue on balance of survivors with chronic stroke: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. (2015) 29:763–70. doi: 10.1177/0269215514556093

8.

De Luca R Lo Buono V Leo A Russo M Aragona B Leonardi S et al . Use of virtual reality in improving poststroke neglect: promising neuropsychological and neurophysiological findings from a case study. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. (2019) 26:96–100. doi: 10.1080/23279095.2017.1363040

9.

Vecchio M Chiaramonte R De Sire A Finocchiaro EBP Scaturro D Mauro GL et al . Do proprioceptive training strategies with dual-task exercises positively influence gait parameters in chronic stroke? A systematic review. J Rehabil Med. (2024) 56:jrm18396. doi: 10.2340/jrm.v56.18396

10.

Chiaramonte R Bonfiglio M Leonforte P Coltraro GL Guerrera CS Vecchio M . Proprioceptive and dual-task training: the key of stroke rehabilitation. A systematic review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiology. (2022) 7:53. doi: 10.3390/jfmk7030053

11.

Pinto TCC Machado L Bulgacov TM Rodrigues-Júnior AL Costa MLG Ximenes RCC et al . Is the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) in the elderly?Int Psychogeriatr. (2019) 31:491–504. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218001370

12.

Tombaugh TN . Trail making test a and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2004) 19:203–14. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8

13.

Van der Elst W Van Boxtel MP Van Breukelen GJ Jolles J . The Stroop color-word test: influence of age, sex, and education; and normative data for a large sample across the adult age range. Assessment. (2006) 13:62–79. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283427

14.

Krootnark K Chaikeeree N Saengsirisuwan V Boonsinsukh R . Effects of low-intensity home-based exercise on cognition in older persons with mild cognitive impairment: a direct comparison of aerobic versus resistance exercises using a randomized controlled trial design. Front Med. (2024) 11:1392429. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1392429

15.

Kuk F Slugocki C Korhonen P . Characteristics of the quick repeat-recall test (Q-RRT). Int J Audiol. (2024) 63:482–90. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2023.2245969

16.

Wang X Hu S Huang CF lei L jun P dan J et al . Effects of dual-task training combined with proprioceptive training on cognitive function and motor function in elderly patients with hemiplegia after stroke. Chin J Gerontol. (2023) 43:2428–31. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2023.10.035 (in Chinese)

17.

Fu XY Li AL . Value of cognitive-motor dual task training in elderly patients with cognitive impairment after stroke. Practical. Clin Med. (2021) 22:43–5. doi: 10.13764/j.cnki.lcsy.2021.01.015 (in Chinese)

18.

Hua Y . Effects of exercise-cognitive dual-task training on cognition and lower limb function in elderly stroke patients with sarcopenia. Chin J Geriatric Care. (2023) 21:43–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672–2671.2023.01.011 (in Chinese)

19.

Hua Y . Effects of hyperbaric oxygen-assisted dual-task training on moto, cognitive function and quality of life in patients with subacute stroke. J Xinjiang Med Univ. (2022) 45:1362–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5551.2022.11.023 (in Chinese)

20.

Yang CX Wang BL . Effects of cognitive-motor dual-task training on attention and memory after stroke. Chin J Rehabil. (2022) 37:707–12. doi: 10.3870/zgkf.2022.12.001 (in Chinese)

21.

Qin Q Tian DY . Effects of cognitive-Otago motor control dual task training on improving cognitive function and limb motor function in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Evid Based Nurs. (2023) 9:333–7. doi: 10.12102/ji.ssn.2095-8668.2023.02.029 (in Chinese)

22.

Zhu LL Chang H Cai WX et al . Effect of cognitive-motor dual-task training on vascular mild cognitive impairment for old patients. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. (2021) 27:37–42. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006.9771.2021.01.005 (in Chinese)

23.

Fu YT Li YN Sun Y Chang Z Ying H Zhi Y et al . Effect of dual task training on the function of patients with subacute stroke. J Kunming Med Univ. (2020) 41:33–8. (in Chinese)

24.

Li SQ Cui YG Zhuang M . Rehabilitation effect of auditory-motor synchronization training combined with cognitive-motor control dual-task training on patients with chronic stroke. Chin J Pract Nerv Dis. (2019) 22:365–9. doi: 10.12083/SYSJ.2019.04.120 (in Chinese)

25.

Kim GY Han MR Lee HG . Effect of dual-task rehabilitative training on cognitive and motor function of stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci. (2014) 26:1–6. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1

26.

Choi JH Kim BR Han EY et al . The effect of dual – task training on balance and cognition in patients with subacute post-stroke. Ann Rehabil Med. (2015) 39:81–90. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.1.81

27.

Park MO Lee SH . Effect of a dual-task program with different cognitive tasks applied to stroke patients: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Neuro Rehabil. (2019) 44:239–49. doi: 10.3233/NRE-182563

28.

An HS Kim DJ . Effects of activities of daily living-based dual-task training on upper extremity function, cognitive function, and quality of life in stroke patients. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. (2021) 12:304–13. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2021.0177

29.

Park MO Lee SH . Effects of cognitive-motor dual-task training combined with auditory motor synchronization training on cognitive functioning in individuals with chronic stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). (2018) 97:e10910. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010910

30.

Sun R Li X Zhu Z Li T Zhao M Mo L et al . Effects of dual-task training in patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:1027104. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1027104

31.

Weaver NA Kuijf HJ Aben HP Abrigo J Bae H-J Barbay M et al . Strategic infarct locations for post-stroke cognitive impairment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 12 acute ischaemic stroke cohorts. Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:448–59. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00060-0

32.

Higuchi Y Sumiyoshi T Seo T Suga M Nishiyama TTS Kasai YK et al . Associations between daily living skills, cognition, and real-world functioning across stages of schizophrenia; a study with the schizophrenia cognition rating scale Japanese version. Schizophr Res Cogn. (2017) 7:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2017.01.001

33.

Maloni H . Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Nurse Pract. (2018) 14:172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2017.11.018

34.

Sun X Li M Li Q Yin H Jiang X tz HL et al . Poststroke cognitive impairment research Progress on application of brain-computer Interface. Biomed Res Int. (2022) 2022:9935192. doi: 10.1155/2022/9935192

35.

Delavaran H Jönsson AC Lövkvist H Iwarsson S Elmståhl S Norrving B et al . Cognitive function in stroke survivors: a 10-year follow-up study. Acta Neurol Scand. (2017) 136:187–94. doi: 10.1111/ane.12709

36.

Pendlebury ST Mariz J Bull L Mehta Z Rothwell PM . MoCA, ACE-R, and MMSE versus the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards neuropsychological battery after TIA and stroke. Stroke. (2012) 43:464–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.633586

37.

Al-Qazzaz NK Ali SH Ahmad SA Islam S . Cognitive assessments for the early diagnosis of dementia after stroke. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2014) 12:1743–51. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S68443

38.

Kim JO Lee SJ Pyo JS . Effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on post-stroke cognitive impairment and vascular dementia: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0227820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227820

39.

Barrett KM Brott TG Brown RD Jr Carter R Geske JR McNeil NRB et al . Enhancing recovery after acute ischemic stroke with donepezil as an adjuvant therapy to standard medical care: results of a phase IIA clinical trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2011) 20:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.12.009

40.

Pang MYC Yang L Ouyang H Lams FMH Huang M Jehu DA et al . Dual-task exercise reduces cognitive-motor interference in walking and falls after stroke. Stroke. (2018) 49:2990–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022157

41.

Wang L Du J Zhao F Chen Z Chang J Qin F et al . Trillium tschonoskii maxim saponin mitigates D-galactose-induced brain aging of rats through rescuing dysfunctional autophagy mediated by Rheb-mTOR signal pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 98:516–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.046

42.

Chen K Huang L Lin B Zhou Y Zhao Q Guo Q et al . The number of items on each Stroop test card is unrelated to its sensitivity. Neuropsychobiology. (2019) 77:38–44. doi: 10.1159/000493553

43.

Sacco G Ben-Sadoun G Bourgeois J Fabre R Manera V Robert P et al . Comparison between a paper-pencil version and computerized version for the realization of a neuropsychological test: the example of the trail making test. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2019) 68:1657–66. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180396

44.

Danneels M Van Hecke R Leyssens L Degees S Berg DCRvd Rompaey VV et al . 2BALANCE: a cognitive-motor dual-task protocol for individuals with vestibular dysfunction. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e037138. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037138

45.

Shin JH Choi H Lee JA deok ES Dohoon K JaeHo K et al . Dual task interference while walking in chronic stroke survivors. Phys Ther Rehabil Sci. (2017) 6:134–9. doi: 10.14474/ptrs.2017.6.3.134

46.

Patel P Bhatt T . Task matters: influence of different cognitive tasks on cognitive-motor interference during dual-task walking in chronic stroke survivors. Top Stroke Rehabil. (2014) 21:347–57. doi: 10.1310/tsr2104-347

47.

Amatachaya S Srisim K Arrayawichanon P Thaweewannakj T Amatachaya P . Dual-task obstacle crossing training could immediately improve ability to control a complex motor task and cognitive activity in chronic ambulatory individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. (2019) 25:260–70. doi: 10.1310/sci18-00038

Summary

Keywords

stroke, cognitive dysfunction, post-stroke cognitive impairment, dual-task training, cognition disorders, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial

Citation

Shi R, Li W, Liu X, Sun Z, Ge X, Lv P and Yin Y (2025) A meta-analysis of the effects of dual-task training on cognitive function in stroke patients. Front. Neurol. 16:1417364. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1417364

Received

14 April 2024

Accepted

02 September 2025

Published

22 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Maria Francesca De Pandis, Hospital San Raffaele Cassino, Italy

Reviewed by

Rita Chiaramonte, University of Catania, Italy

Mina Kheirkhah, University Hospital Jena, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Shi, Li, Liu, Sun, Ge, Lv and Yin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Yin, yinyu-99@163.com; Weibo Li, liweibo-99@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.