Abstract

Aim:

To assessment the new biomarker, the inflammatory burden index (IBI) and their correlations with clinical outcome as well as stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP) of ICH patients.

Methods:

Patients diagnosed as spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage (SICH) were retrospectively screened from December 2018 to December 2022. The IBI was formulated as C-reactive protein×neutrophils/lymphocytes. In addition, systemic-inflammatory indices including ratios of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte (PLR),and patelet-to-neutrophil (PNR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) on admission also were calculated. The primary outcome measure was 90-day functional outcome and the occurrence of SAP, with an mRS 3–6 score representing a unfavorable outcome. We used ROC curves to evaluate the diagnostic value of these differences. Univariate and multivariable analyses was conducted to identify the factors independently associated with 3 months unfavorable functional outcomes and stroke-associated pneumonia.

Results:

A total of 209 patients were enrolled, of which 144 (68.9%) had unfavorable 90-day functional outcome, and 89 (42.1%) ICH patients developed SAP. Elevated IBI is an independent predictor for both stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP) and unfavorable 3-month outcomes in acute ICH patients, and showed a good predictive ability for SAP (AUC = 0.811, p < 0.001) and poor prognosis at 3 months (AUC = 0.745, p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Inflammatory biomarker index (IBI) are predictive of 90-day functional outcome and the SAP occurrence in patients with ICH.

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a particularly devastating form of stroke. Although it represents merely 10–20% of all stroke cases, it accounts for approximately 44% of stroke-related mortality and 60–80% of survivors experience serious neurological impairment, underscoring its disproportionately high clinical impact (1, 2). Most survivors of ICH continue to face complications, stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP) is the most common devastating complication, with an incidence rate of 34.6%, which also have a significant impact on the patient’s overall prognosis (3). Therefore, it is essential to find an early screening strategy for diagnosis and prognosis prediction in ICH patients (4–6). The inflammatory response contributes to the ICH-induced secondary brain injury and is indispensable in the occurrence and progression of SAP (7).

Within hours to days following ICH, a series of inflammatory reactions around the hematoma contributes to secondary injuries and worsen the prognosis (8). Correspondingly, peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers, as easily accessible markers, may help predict functional outcomes (9). Previous studies have found that systemic inflammatory indices such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) are correlated with the clinical outcomes and complications of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) patients (9–15). The Inflammatory Burden Index (IBI) is a novel inflammatory marker defined as C-reactive protein (CRP) multiplied by the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (16–18). Reflecting the level of inflammatory burden in tumors, IBI has been proven to be a strong prognostic predictor for cancer patients and may be the optimal indicator among various systemic inflammation indicators.

Accordingly, in this study, we aimed to investigate the association between IBI and the prognosis as well as in-hospital complications of ICH patients. We also compared the prognostic performance of IBI with previously reported inflammatory biomarkers to determine their prognostic value.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients diagnosed as spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage (SICH) at a comprehensive stroke center were retrospectively screened from December 2018 to December 2022. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

(1) Diagnosis of spontaneous SICH, confirmed first (or recurrent) stroke by computerized tomography (CT).

-

(2) Within 72 h from the onset.

-

(3) Aged 18 years or older.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

(1) Secondary intracranial hemorrhage, caused by trauma, brain tumor, ruptured aneurysm, vascular malformation, venous sinus thrombosis, or other known causes.

-

(2) Pre-stroke disability [a premorbid modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of ≥3].

-

(3) Patients who required surgical intervention.

-

(4) Severe hepatic or renal dysfunction.

-

(5) The presence of systemic inflammatory rheumatic diseases, hematologic diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, systemic or localized infectious diseases, and active cancer; concurrent/recent infectious diseases, or ongoing anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory therapies.

-

(6) Missing clinical or follow-up information.

Clinical, imaging, and outcome data collection

The detailed data collected from the electronic medical record system were as follows:

-

(1) Demographic data (sex, age, smoker and alcohol drinker).

-

(2) Medical history (hypertension, diabetes, and previous history of stroke).

-

(3) Initial imaging (hemotoma volume [calculated by a*b*c/2], the presence of IVH).

-

(4) Admission status (NIHSS, GCS score, Systolic BP, mmHg, Diastolic BP, mmHg).

-

(5) Laboratory tests (CRP, neutrophils, lymphocytes, glucose, hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets and monocytes).

The primary outcome of the study was 90-day unfavorable outcome, defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 3–6. The secondary outcome was stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP). According to the recommendations of the Pneumonia in Stroke Consensus Group, SAP was defined as the spectrum of lower respiratory tract infections within the first 7 days after stroke onset; (19) It was diagnosed on a basis of clinical symptoms (eg, cough, purulent sputum), signs (eg, fever, tachypnea), or laboratory investigations (eg, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein), and supported by typical chest radiographs findings.

All outcomes assessments were assessed by certified neurologists who were blinded to the clinical data.

Inflammatory biomarkers

Blood samples were routinely collected for the blood counts (including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes) assessment within 24 h after admission. In cases where multiple laboratory data were obtained during these time period, the highest value was recorded.

-

Inflammatory Burden Index (IBI) = CRP × neutrophils/lymphocytes,

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) = neutrophils/lymphocytes,

-

Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) = monocytes/lymphocytes,

-

Platelets-to-Lymphocytes Ratio (PLR) = platelets/lymphocytes,

-

and Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) = neutrophils × monocytes/lymphocytes.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were expressed as the mean (standard deviation; SD) or median (interquartile range; IQR), and the categorical variables were presented as counts (percentages). For continuous variables, intergroup differences were analyzed using Student t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. We used the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and Q-Q plots to evaluate the normality of the data for comparison of categorical variables, the chi-squared test was used. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the effect of IBI, NLR, PLR, MLR and SIRI on 3-month functional outcomes, while adjusting for potential confounders. We plotted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess the predictive performance of the model. The predictive accuracy of the index was then determined by measuring the specificity, sensitivity and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

SPSS 22.0 and R 3.6.2 software were employed for statistical analysis with p<0.05 defined as statistical significance.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University. It was performed according to the Principles of Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of its retrospective nature and minimal risk to patients. This study was reported in accordance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (20).

Results

Study population and baseline characteristic

A total of 209 patients were included, the median age was 60.0 (53.0–67.0) years, and 147 (70.3%) patients were male. The median NIHSS and GCS scores on admission were 6 (IQR, 3–10) and 15 (IQR, 13–15), respectively. Among the total patients patients, 144 (65.45%) had an unfavorable outcome at 3 months (Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristic | mRS Score at 3 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 (n = 65) | 3–6 (n = 144) | p value | |

| Age (median [IQR]) | 58.00 [47.00, 66.00] | 62.50 [54.00, 71.00] | 0.017 |

| Male, n (%) | 42 (64.6) | 105 (72.9) | 0.293 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 21 (32.8) | 55 (39.0) | 0.487 |

| Alcohol drinker, n (%) | 21 (32.8) | 56 (39.7) | 0.429 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 52 (80.0) | 125 (86.8) | 0.290 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 8 (12.3) | 34 (23.6) | 0.089 |

| NIHSS, median [IQR] | 2.00 [1.00, 4.00] | 9.00 [5.00, 12.50] | <0.001 |

| GCS score, median [IQR] | 15.00 [15.00, 15.00] | 15.00 [12.00, 15.00] | 0.012 |

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 154.50 (26.11) | 156.72 (22.65) | 0.536 |

| DBP, median [IQR] | 90.50 [80.75, 98.25] | 90.00 [80.00, 100.00] | 0.518 |

| Hematoma_volume, median [IQR] | 5.77 [2.20, 14.00] | 11.53 [6.23, 19.90] | 0.001 |

| Edema degree, mean (SD) | 2.52 (0.79) | 2.85 (0.72) | 0.004 |

| Nasogastric tube, n (%) | 18 (26.8) | 41 (28.4) | 0.731 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 7 (10.4) | 19 (13.1) | 0.660 |

| Neutrophils, mean (SD) | 5.46 (2.28) | 6.98 (3.38) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes, mean (SD) | 1.93 (2.14) | 1.30 (0.62) | 0.001 |

| Monocytes, mean (SD) | 0.55 (0.72) | 0.54 (0.43) | 0.814 |

| PLT, mean (SD) | 224.36 (60.03) | 216.67 (80.97) | 0.509 |

| CRP, median [IQR] | 3.00 [2.00, 5.25] | 7.60 [3.50, 29.00] | <0.001 |

| IBI, median [IQR] | 8.68 [3.92, 25.48] | 34.90 [10.15, 261.38] | <0.001 |

| NLR, median [IQR] | 3.07 [1.91, 4.83] | 4.96 [3.05, 9.11] | <0.001 |

| MLR, median [IQR] | 0.25 [0.19, 0.36] | 0.38 [0.25, 0.60] | <0.001 |

| PLR, median [IQR] | 125.75 [103.78, 160.00] | 152.41 [109.19, 228.52] | 0.008 |

| SIRI, median [IQR] | 3.07 [1.89, 4.82] | 4.77 [2.94, 8.75] | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics of the 209 patients with ICH.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR); SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia. The bold values are the significant values (p < 0.05).

Patients with unfavorable outcome at 3 months had higher age (p = 0.017), lower admission GCS scores (p = 0.012), higher NIHSS scores (p < 0.001), larger hematoma volumes (p < 0.001) and higher edema degree (p = 0.004). The distribution of GCS is visualized in Figure 1. Meanwhile, higher IBI (p < 0.001), NLR (p < 0.001), PLR (p = 0.008), SIRI (p < 0.001) and CRP (p < 0.001) values on admission were observed in patients with unfavorable outcome at 3 months, as shown in Table 1.

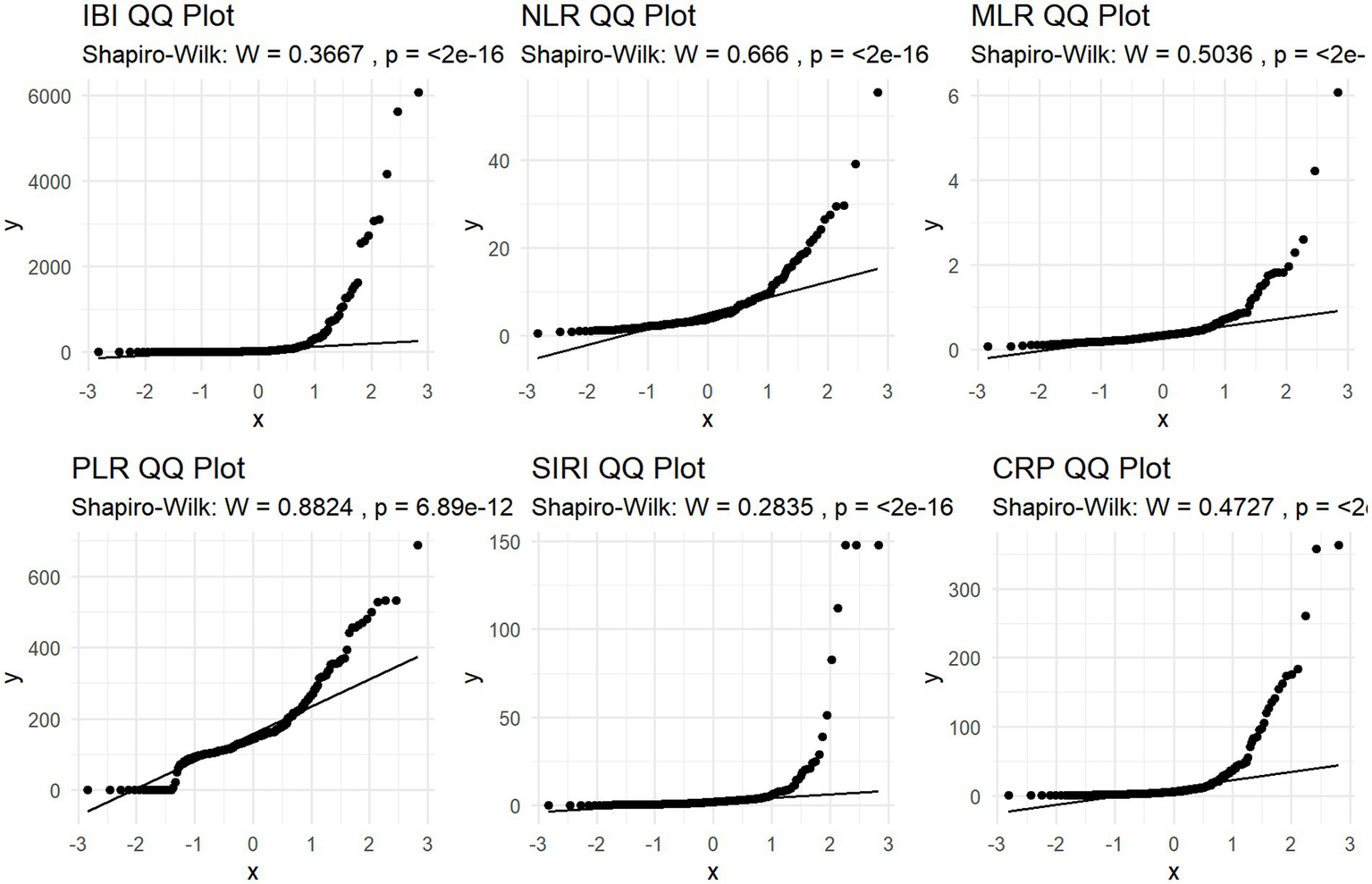

Figure 1

QQ plot of study participant distribution based on Inflammatory indicators.

Unfavorable outcome

Shapiro–Wilk normality test and Q-Q plot was performed to evaluate normality assumption. The result showed typical skewness of the data, so logarithmic conversion was performed on it. (Shapiro–Wilk W>0.05; p < 0.05; Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Skewness | Kurtosis | Shapiro_W | Shapiro_p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBI | 4.898 | 30.337 | 0.367 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 3.228 | 17.729 | 0.666 | <0.001 |

| MLR | 5.287 | 40.866 | 0.504 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 1.363 | 5.554 | 0.882 | <0.001 |

| SIRI | 5.897 | 39.134 | 0.283 | <0.001 |

| SII | 2.718 | 14.006 | 0.734 | <0.001 |

Skewness, Kurtosis, and Shapiro–Wilk test results for normality assessment of inflammatory indicators.

IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR).

Figure 2

Distribution of GCS.

Univariate analyses showed that the patients with unfavorable outcome had higher levels of lnIBI, lnNLR, lnMLR, lnPLR, lnSIRI and lnCRP; After the adjustment for potential confounders, including age, sex, Diabetes mellitus, NIHSS, Hematoma volume and Edema, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that lnIBI (p < 0.001, OR = 1.607, 95% CI 1.240–2.144), NLR (p = 0.003, OR = 2.232, 95% CI 1.199–4.366), and CRP (p = 0.025, OR = 1.518, 95%CI 1.069–2.225) were independent predictors of poor prognosis (Table 3).

Table 3

| 90-day mRS | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR | p_value | OR | p_value |

| Sex | 1.444 (0.754–2.764) | 0.283 | 0.771 (0.307–1.884) | 0.572 |

| Age | 1.037 (1.014–1.061) | 0.004 | 1.024 (0.993–1.057) | 0.139 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.922 (0.894–4.133) | 0.052 | 2.361 (0.847–7.096) | 0.110 |

| NIHSS | 1.246 (1.156–1.344) | <0.001 | 1.459 (1.295–1.681) | <0.001 |

| Hematoma volume | 1.718 (1.498–2.038) | 0.0379 | 0.992 (0.961–1.025) | 0.611 |

| Edema | 1.765 (1.162–2.680) | 0.004 | 1.280 (0.718–2.305) | 0.404 |

| ln IBI | 1.810 (1.492–2.198) | <0.001 | 1.607 (1.240–2.144) | <0.001 |

| ln NLR | 2.782 (1.762–4.392) | <0.001 | 2.232 (1.199–4.366) | 0.003 |

| ln MLR | 2.767 (1.621–4.720) | <0.001 | 1.724 (0.899–3.559) | 0.118 |

| ln PLR | 2.750 (1.438–5.259) | 0.002 | 1.505 (0.903–2.783) | 0.147 |

| ln SIRI | 1.819 (1.308–2.531) | <0.001 | 1.356 (0.893–2.115) | 0.161 |

| lnCRP | 2.058 (1.514–2.799) | <0.001 | 1.518 (1.069–2.225) | 0.025 |

Univariate and multivariate logistics regression analyses for 90 day functional outcome.

Multivariable regression: adjusted for age, sex, Diabetes mellitus, NIHSS, Hematoma volume and Edema. As indicated by the bold font, the p value reached statistical significance.

ln, the natural logarithm; OR, odds ratio; CI, con confidence intervals; IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR). The bold values are the significant values (p < 0.05).

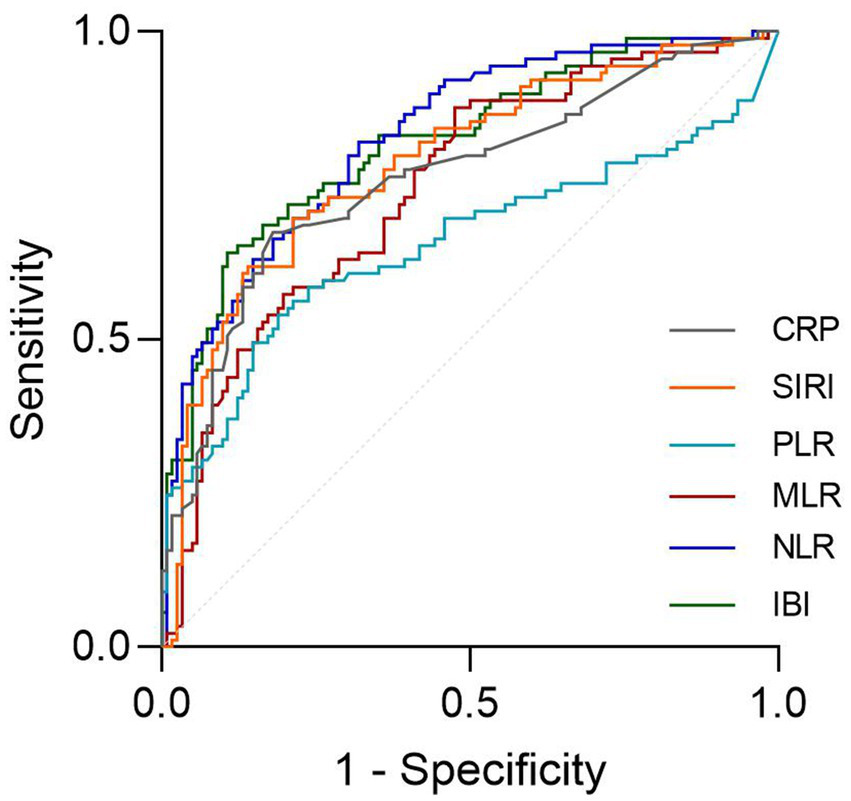

The ROC analysis and AUCs with respect to the 90 day outcome are shown in the Figure 3. ROC analysis revealed that IBI had good predictive accuracy for mRS (AUC = 0.745, p < 0.001), followed by NLR (AUC = 0.719, p < 0.001), without significant difference in AUC between the IBI and NLR (DeLong test, p = 0.146). MLR, SIRI and CRP showed moderate predictive value (AUC = 0.673–0.695, all p < 0.001), while PLR performed poorly, respectively (AUC = 0.605, p = 0.0087) (Figure 4). Details of the optimal cutoff, specificity and sensitivity rates are shown in Table 4.

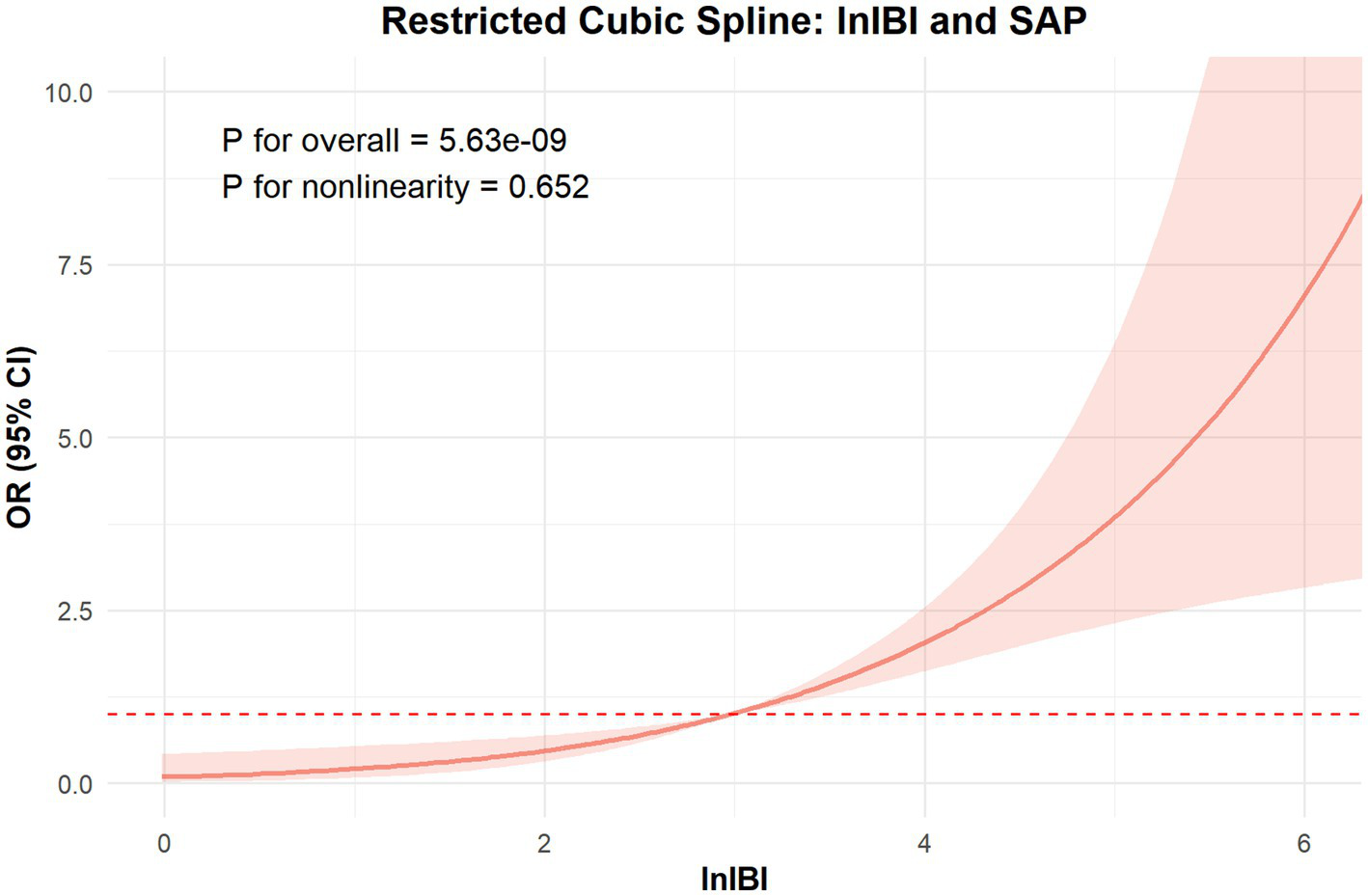

Figure 3

Association between lnIBI and mRS: Restricted Cubic Spline analysis.

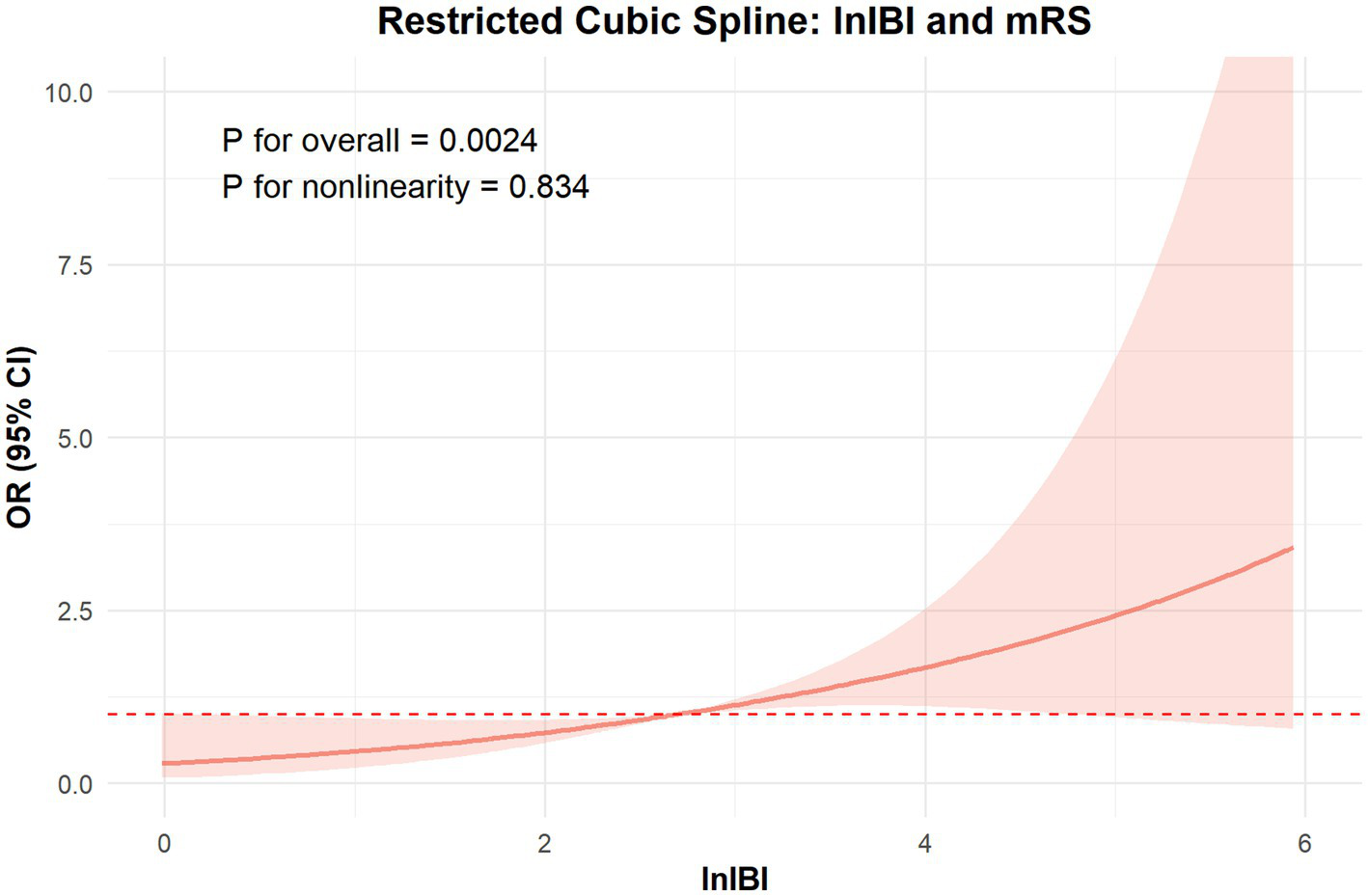

Figure 4

Association between lnIBI and SAP: Restricted Cubic Spline analysis.

Table 4

| mRS | AUC | 95% CI | Cut off | Sensitivity | Specificity | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBI | 0.745 | 0.688 to 0.822 | 52.356 | 0.472 | 0.887 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 0.719 | 0.6469 to 0.7916 | 5.098 | 0.514 | 0.806 | <0.001 |

| MLR | 0.673 | 0.6087 to 0.7611 | 0.377 | 0.514 | 0.823 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 0.605 | 0.5333 to 0.6872 | 165.899 | 0.438 | 0.806 | 0.00871 |

| SIRI | 0.668 | 0.6090 to 0.7611 | 2.153 | 0.569 | 0.71 | <0.001 |

| CRP | 0.695 | 0.6230 to 0.7674 | 6.995 | 0.549 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

AUC in predicting 90 day outcomes.

AUC, Area Under Curve; CI, con confidence intervals; IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR).

SAP occurrence

In univariate analyses, elevated levels of lnIBI, lnNLR, lnMLR, lnPLR, lnSIRI and lnCRP were associated with an increased risk of SAP. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for confounders factors, including age, sex, Diabetes mellitus, NIHSS, Hematoma volume, Edema, Nasogastric feeding and mechanical ventilation, elevated ln-transformed inflammatory biomarkers remained independent predictors of poor outcomes. NLR (OR = 4.993, 95% CI 2.724–9.919), IBI (OR = 1.813, 95% CI 1.446–2.333) showed particularly strong associations (all p < 0.001, Table 5).

Table 5

| SAP | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR | p_value | OR | p_value |

| Sex | 1.384 (0.761–2.556) | 0.291 | 0.865 (0.385–1.958) | 0.724 |

| Age | 1.044 (1.022–1.067) | 0.001 | 1.033 (1.004–1.064) | 0.0277 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.215 (0.611–2.395) | 0.573 | 0.967 (0.385–2.366) | 0.942 |

| NIHSS | 1.156 (1.098–1.225) | <0.001 | 1.124 (1.052–1.207) | 0.009 |

| Hematoma volume | 1.036 (1.016–1.060) | 0.001 | 1.017 (0.990–1.047) | 0.227 |

| Edema | 1.492 (1.032–2.189) | 0.036 | 0.909 (0.528–1.549) | 0.727 |

| Nasal | 0.888 (0.481–1.619) | 0.701 | 0.796 (0.301–2.008) | 0.634 |

| respirator | 0.870 (0.363–1.993) | 0.7461 | 0.613 (0.148–2.412) | 0.489 |

| ln IBI | 2.107 (1.729–2.638) | <0.001 | 1.813 (1.446–2.333) | <0.001 |

| ln NLR | 6.956 (4.115–12.659) | <0.001 | 4.993 (2.724–9.919) | <0.001 |

| ln MLR | 3.544 (2.211–5.998) | <0.001 | 2.243 (1.311–4.037) | 0.005 |

| ln PLR | 5.313 (2.749–10.960) | <0.001 | 3.628 (1.742–8.275) | 0.001 |

| ln SIRI | 1.933 (1.472–2.618) | <0.001 | 1.461 (1.080–2.010) | 0.015 |

| lnCRP | 2.156 (1.680–2.849) | <0.001 | 1.661 (1.237–2.281) | 0.001 |

Univariate and multivariate logistics regression analyses for SAP occurrence.

Multivariable regression: adjusted for age, sex, Diabetes mellitus, NIHSS, Hematoma volume and Edema. As indicated by the bold font, the p Value reached statistical significance.

ln, the natural logarithm; OR, odds ratio; CI, con confidence intervals; IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR). The bold values are the significant values (p < 0.05).

The ROC curves demonstrated that NLR and IBI presented a high predictive value for SAP occurence (Figure 5, AUC = 0.811, 0.814, respectively), without significant difference in AUC between the IBI and NLR (DeLong test, p = 0.881). Details of the optimal cutoff, specificity and sensitivity rates are shown in Table 6.

Figure 5

The ROC value of CRP, SIRI, PLR, MLR, NLR and IBI in predicting 3-months poor functional outcomes in ICH patients.

Table 6

| SAP | AUC | 95%CI | Cut off | Sensitivity | Specificity | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBI | 0.811 | 0.751–0.871 | 62.985 | 0.64 | 0.889 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 0.814 | 0.756–0.872 | 3.666 | 0.82 | 0.641 | <0.001 |

| MLR | 0.741 | 0.673–0.809 | 0.279 | 0.876 | 0.513 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 0.652 | 0.571–0.734 | 173.689 | 0.539 | 0.812 | <0.001 |

| SIRI | 0.781 | 0.716–0.846 | 2.433 | 0.697 | 0.778 | <0.001 |

| CRP | 0.757 | 0.689–0.825 | 6.995 | 0.674 | 0.795 | <0.001 |

AUC in predicting SAP occurrence.

AUC, Area Under Curve; CI, con confidence intervals; IBI, inflammatory burden index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR); monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR).

The RCS analysis revealed no nonlinear relationship between IBI and the occcurance of SAP and 90 day function outcome (p for overall < 0.01, p for nonlinear = 0.652, 0.834, respectively). The risk of SAP and poor prognosis was progressively increased with increasing inflammatory markers, without a clear inflection point (Figure 6).

Figure 6

The ROC value of CRP, SIRI, PLR, MLR, NLR and IBI in predicting SAP in ICH patients.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are that elevated IBI are independent risk factors for SAP and showed a good predictive ability for SAP (AUC = 0.811, p < 0.001). The elevated IBI is independent predictor of unfavorable outcomes at 3 months in patients with acute ICH and showed moderate predictive ability for poor prognosis at 3 months (AUC = 0.745, p < 0.001). Furthermore, in comparisons of various inflammatory indicators, we observed that IBI consistently showed significant and stable results in assessing stroke prognosis and SAP.

Systemic inflammation plays a significant role in the secondary injury of ICH. Accumulating evidences indicate readily available serum biomarkers of inflammation can be efficient predictive indicators of prognosis in patients with ICH (21–23). Similar to the findings of us, Wang observed that among the NLR, SII, PLR, SIRI, the NLR was the best predictor for SAP occurrence and a poor outcome at 3 months in ICH patients. However, the limitations of their study are that their study only shows the predictive power of the SII and SIRI for mRS scores at 3 months (13). A meta-analysis of 14 studies showed that NLR independently predicted 90-day prognosis, but due to substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, the results should be view with caution (11). Therefore, a quest for more reliable predictive inflammatory markers of the prognosis and complications of ICH patients is still warranted.

The inflammatory biomarker index (IBI) has been identified as a more reliable prognostic marker for cancer compared to other combinations of inflammatory biomarkers. One study reported that elevated IBI levels at admission were associated with poor functional outcomes and complications in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (24). Another study demonstrated that higher IBI levels were an independent predictor of poor outcomes in ischemic stroke patients undergoing endovascular therapy (EVT) (16). However, to date, no studies have explored the relationship between IBI and the prognosis or incidence of complication in patients with cerebral hemorrhage.

Our findings demonstrate that IBI, NLR, and CRP are independent predictors of poor prognosis and SAP (p < 0.05), in which IBI has a relatively more robust association with the prognosis at 3 months and complications of aSAH patients. A potential explanation for this advantage is that NLR integrate information from neutrophils and Lymphocytes, reflecting the balance between innate (neutrophils) and adaptive (lymphocytes) immune responses. The impact of NLR on neurological outcome and SAP has been demonstrated by previous studies (13, 25–27). C-reactive protein (CRP) is acute-phase proteins induced by inflammatory factors, plasma CRP have been proven to be an independent predictor of ICH outcome, early hematoma growth and early neurological worsening (28, 29). In combination, IBI may be more valuable and reliable biomarkers for predicting outcomes across various diseases, providing both acute and immune inflammatory information (17).

Neutrophils is the first peripheral blood cell type to infiltrate perihematomal tissue and the hematoma itself following ICH. Neutrophils promote the release of free radicals and matrix metalloproteinase-9, which lead to cellular injury, endothelial basement membrane injury and the destruction of brain–blood barrierr and the increase of tissue edema around cerebral hematoma (8, 30). It was found that autoreactive T cells could promote vascular reconstruction and healing after cerebral trauma. Hence, the increase of blood neutrophils would increase Blood–Brain Barrier breakdown, while increase of blood regulatory T lymphocytes could alleviate the degradation of Blood–Brain Barrier (31, 32). Research indicates that elevated CRP can lead to blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption through CD16/CD32-mediated p38-MAPK-dependent ROS formation and activation of MLCK, which triggers the cellular contractile machinery and consequently causes BBB breakdown (33). As a result, elevated IBI (an increase of blood neutrophils or decrease of lymphocytes) might aggravate the degradation of Blood–Brain Barrier and worsen Brain damage.

Our research has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective, single-center study, the number of patients in this cohort is limited. Accordingly, the possibility of Type II error cannot be ruled out. Second, only inflammatory indexes within the first 24 h of admission was collected as an observation index, and the effect of dynamic indicators change on prognosis was not evaluated. Thus, future studies are needed to explore the changes and predictive value of inflammatory factors at different time points after onset. Third, all of the patients included in the present study were Chinese, further studies are needed to investigate if these results are reproducible in other populations.

In our study of 209 patients with ICH, we demonstrated that the inflammatory biomarker index (IBI) has significant clinical value in predicting poor functional outcomes and SAP. IBI reflects both the likelihood of secondary brain injury and the susceptibility to post-stroke complications. Therefore, monitoring IBI can assist clinicians in identifying patients at higher risk of poor prognosis, particularly in emergency settings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. QC: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft. JS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Support was received from Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan (PZ2024009) for the year 2024; and Beijing Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Development Fund Project (JJ-2023-93).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:795–820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

2.

Ma Q Li R Wang L Yin P Wang Y Yan C et al . Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990-2019: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e897–906. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00228-0

3.

Wang YJ Li ZX Gu HQ Zhai Y Zhou Q Jiang Y et al . China stroke statistics: an update on the 2019 report from the National Center for healthcare quality Management in Neurological Diseases, China National Clinical Research Center for neurological diseases, the Chinese Stroke Association, National Center for chronic and non-communicable disease control and prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and institute for global neuroscience and stroke collaborations. Stroke Vasc Neurol. (2022) 7:415–50. doi: 10.1136/svn-2021-001374

4.

Koennecke HC Belz W Berfelde D Endres M Fitzek S Hamilton F et al . Factors influencing in-hospital mortality and morbidity in patients treated on a stroke unit. Neurology. (2011) 77:965–72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822dc795

5.

Ziai WC . Hematology and inflammatory signaling of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2013) 44:S74–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000662

6.

Chu H Huang C Zhou Z Tang Y Dong Q Guo Q . Inflammatory score predicts early hematoma expansion and poor outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Surg. (2023) 109:266–76. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000191

7.

Ohashi SN DeLong JH Kozberg MG Mazur-Hart DJ van Veluw SJ Alkayed NJ et al . Role of inflammatory processes in hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke. (2023) 54:605–19. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.037155

8.

Xue M Yong VW . Neuroinflammation in intracerebral haemorrhage: immunotherapies with potential for translation. Lancet Neurol. (2020) 19:1023–32. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30364-1

9.

Shtaya A Bridges LR Williams R Trippier S Zhang L Pereira AC et al . Innate immune anti-inflammatory response in human spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2021) 52:3613–23. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034673

10.

Lattanzi S Brigo F Trinka E Cagnetti C di Napoli M Silvestrini M . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute cerebral hemorrhage: a system review. Transl Stroke Res. (2019) 10:137–45. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0649-4

11.

Shi M Li XF Zhang TB Tang QW Peng M Zhao WY . Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:825859. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.825859

12.

Kim Y Sohn JH Kim C Park SY Lee SH . The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting hematoma expansion and poor outcomes in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:3004. doi: 10.3390/jcm12083004

13.

Wang RH Wen WX Jiang ZP Du ZP MZH Lu AL et al . The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1115031. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1115031

14.

Li Y Wen D Cui W Chen Y Zhang F Yuan M et al . The prognostic value of the acute phase systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:628557. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.628557

15.

Zhao G Gu Y Wang Z Chen Y Xia X . The clinical value of inflammation index in predicting ICU mortality of critically ill patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1373585. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1373585

16.

Du M Xu L Zhang X Huang X Cao H Qiu F et al . Association between inflammatory burden index and unfavorable prognosis after endovascular Thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:3009–17. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S419087

17.

Xie H Ruan G Ge Y Zhang Q Zhang H Lin S et al . Inflammatory burden as a prognostic biomarker for cancer. Clin Nutr. (2022) 41:1236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.04.019

18.

Xie H Ruan G Wei L Deng L Zhang Q Ge Y et al . The inflammatory burden index is a superior systemic inflammation biomarker for the prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2023) 14:869–78. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13199

19.

Smith CJ Kishore AK Vail A Chamorro A Garau J Hopkins SJ et al . Diagnosis of stroke-associated pneumonia: recommendations from the pneumonia in stroke consensus group. Stroke. (2015) 46:2335–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009617

20.

Vandenbroucke JP Elm E Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Mulrow CD Pocock SJ et al . Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 147:W-163–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1

21.

Agnihotri S Czap A Staff I Fortunato G McCullough LD . Peripheral leukocyte counts and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. (2011) 8:160. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-160

22.

Di Napoli M Godoy DA Campi V del Valle M Piñero G Mirofsky M et al . C-reactive protein level measurement improves mortality prediction when added to the spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage score. Stroke. (2011) 42:1230–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604983

23.

Brunswick AS Hwang BY Appelboom G Hwang RY Piazza MA Connolly ES Jr . Serum biomarkers of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage induced secondary brain injury. J Neurol Sci. (2012) 321:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.06.008

24.

Song Z Lin F Chen Y Li T Li R Lu J et al . Inflammatory burden index: association between novel systemic inflammatory biomarkers and prognosis as well as in-hospital complications of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:3911–21. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S416295

25.

Sun Y You S Zhong C Huang Z Hu L Zhang X et al . Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the hematoma volume and stroke severity in acute intracerebral hemorrhage patients. Am J Emerg Med. (2017) 35:429–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.037

26.

Ray S Kumar V Biswas R Ojha VS Bhushan D Kirti R et al . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker of functional outcome in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and its comparison with ICH score: a hospital-based study. Cureus. (2024) 16:e69350. doi: 10.7759/cureus.69350

27.

Guo P Zou W . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, white blood cell, and C-reactive protein predicts poor outcome and increased mortality in intracerebral hemorrhage patients: a meta-analysis. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1288377. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1288377

28.

Lattanzi S Cagnetti C Provinciali L Silvestrini M . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the outcome of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2016) 47:1654–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013627

29.

Di Napoli M Godoy DA Campi V Masotti L Smith CJ Parry Jones AR et al . C-reactive protein in intracerebral hemorrhage: time course, tissue localization, and prognosis. Neurology. (2012) 79:690–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e3be

30.

Aronowski J Zhao X . Molecular pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: secondary brain injury. Stroke. (2011) 42:1781–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596718

31.

Woiciechowsky C Asadullah K Nestler D Eberhardt B Platzer C Schöning B et al . Sympathetic activation triggers systemic interleukin-10 release in immunodepression induced by brain injury. Nat Med. (1998) 4:808–13. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-808

32.

Dirnagl U Klehmet J Braun JS Harms H Meisel C Ziemssen T et al . Stroke-induced immunodepression: experimental evidence and clinical relevance. Stroke. (2007) 38:770–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251441.89665.bc

33.

Kuhlmann CR Librizzi L Closhen D Pflanzner T Lessmann V Pietrzik CU et al . Mechanisms of C-reactive protein-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke. (2009) 40:1458–66. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535930

Summary

Keywords

intracerebal hemorrhage, prognosis predict, stroke associated pneumonia, biomaker, inflammatory index, NLR

Citation

Wang X, He L, Cui Q, Zhao J and Song J (2025) Association of inflammatory burden index with prognosis as well as stroke-associated pneumonia in non-surgical patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 16:1596731. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1596731

Received

23 April 2025

Accepted

25 June 2025

Published

09 July 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Sheng Luo, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Luis Alberto Camputaro, Specialized Institute “Hospital El Salvador”, El Salvador

Heng Meng, Jinan University, China

Tieshi Zhu, Central People’s Hospital of Zhanjiang, China

Sennur Delibas Kati, Antalya Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wang, He, Cui, Zhao and Song.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juexian Song, songjuexian@vip.163.com; songjuexian@xwhosp.org

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.