Abstract

Introduction:

Braak’s hypothesis suggests that α-synuclein may enter the central nervous system through the enteric nervous system and contribute to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). The appendix, enriched in α-synuclein, has been proposed as a possible entry point in PD pathogenesis. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the association between appendectomy and PD risk using newly available data.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted in PubMed and Embase through September 10, 2024, to identify studies on appendectomy and PD risk. Two independent reviewers screened and assessed articles for eligibility with a third reviewer involved in cases of disagreement. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Data for meta-analysis were pooled using a random-effects model and analyzed in Review Manager 5.4. Meta-regression, subgroup, and sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results:

Nine studies met inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis indicated no significant association between appendectomy and PD risk (RR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.90–1.12, p = 0.89). Subgroup analyses showed similar findings. Sensitivity analyses did not change the estimate.

Conclusion:

This analysis suggests no association between appendectomy and PD risk.

1 Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder globally, after Alzheimer’s disease (1). Clinically, PD is characterized by bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, and postural instability, along with various non-motor symptoms (2). The Braak’s hypothesis was previously proposed, suggesting α-synuclein may enter the brain through the olfactory and enteric nervous system, potentially leading to sporadic PD (3–5). The appendix is notably enriched in α-synuclein compared to other gastrointestinal structures, potentially serving as an anatomical entry point in PD pathogenesis (6). Therefore, appendectomy can potentially impact the pathogenic development of PD. Previous observational studies investigating the association between appendectomy and PD risk have yielded inconsistent results (7, 8). This study aimed to reassess this association in light of newly available literature.

2 Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (9). The study was registered on INPLASY per protocol to promote transparency and reduce potential bias (Registration number: INPLASY202490039).

2.1 Literature search and inclusion criteria

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed and Embase through September 10, 2024, to identify potential literature. The search terms used were (parkinson OR parkinsonian OR parkinsonism OR parkinson disease OR parkinson’s disease OR paralysis agitans OR parkinsonian disorders OR parkinsonian syndromes OR parkinsonian diseases) AND (appendectomy OR appendectomy OR appendicitis OR appendix OR append*). Inclusion criteria encompassed case–control studies, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective cohort studies published in English, of high quality, with a matched control group, and reporting measurable outcomes.

2.2 Data extraction

HubMeta, a free web-based data entry system, was used in the data extraction process. Two independent reviewers (HLC and YST) screened titles and abstracts of extracted data after removing duplicates. Full-text articles were then assessed independently by the same reviewers to determine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (HS) until consensus was reached.

2.3 Quality assessment

The quality of the collected literature was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Studies with a score > = 7 were considered high quality studies. Two researchers (HLC and YST) independently conducted the quality assessments, with any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer (HS) after discussion.

2.4 Statistical analysis

We pooled the data and calculated adjusted relative risks (RR) with 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI). Odd ratios (OR) and Hazard ratios (HR) were treated as RR in this study, given that the prevalence of PD in the general population is less than 10% (10). The meta-analysis study employed the random-effects model, and statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic, with I2 > =50 indicating significant heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted using a fixed-effects model to assess differences between groups. Initial subgroup analyses included maximum follow-up years and study design. Additional subgroup analyses based on geographic region and appendectomy assessment method were conducted in response to reviewers’ feedback. No adjustment for multiple testing was applied for subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analysis was also performed to determine the robustness of the results. Meta-regression, Egger’s test and Begg’s test were conducted using STATA/SE version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Meta-regression was performed as a random-effects meta-regression model with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method. The moderators included follow-up years, study design, geographic region, and appendectomy assessment method.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection and characteristics

The initial literature search retrieved 764 articles, with 532 remaining after removing duplicates. Title and abstract screening excluded 513 articles, and 19 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, three articles had only abstract available without further data published in full text. Three articles were abstracts that later published as full articles which were included in the analysis. Four studies were excluded based on quality criteria assessed by NOS. Ultimately, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review and meta-analysis (11–19) (Figure 1). The quality assessment of the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale is depicted in Table 1.

Figure 1

Flow diagram of included studies.

Table 1

| Articles | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of nonexposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome not present at the start of the study | Assessment of outcomes | Length of follow-up | Adequacy of follow-up | |||

| Marras et al. (11) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Svensson et al. (12) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Killinger et al. (13) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Palacios et al. (14) | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 7 | ||

| Liu et al.# (15) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Jain et al. (16) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Koning et al. # (17) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Park et al. (18) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 8 | |

| Wang et al. (19) | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7 | ||

Quality assessment of the included studies by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

NOS In case–control studies consists of: Selection: (1) Representativeness of the cases, (2) Case definition adequacy, (3) Selection of controls, (4) Definition of controls; Comparability; Exposure: (1) Ascertainment of exposure, (2) Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls, (3) Non-response rate.

The included studies comprised a total population of 8,297,621, with sample sizes ranging from 49,248 to 3,224,650. The studies were published between 2016 and 2024 and included participants from Canada (11), Denmark (12), Sweden (13, 15), United States (14, 16, 17), Korea (18), United Kingdom (19). Of the 9 included studies, 7 studies were cohort studies (11–14, 16, 18, 19), 1 was case–control (15), and 1 employed a case–control design with complementary cohort (17). Assessment of appendectomy included self-report and recorded codes. Assessment of PD included recorded codes and history of antiparkinson drug prescription. Maximum follow-up time ranged from 13 years to 52 years. All included studies scored highly on the NOS, with scores between 7 and 9. The characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2

| Articles | Country | Data information | Study design | Sample size | Appendectomy assessment | PD assessment | Maximum follow-up years | Effect estimate (95% CI) | Adjustments | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marras et al. (11) | Canada | Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) database and Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database | Cohort | 85,994 | Medical record | ICD-8,9,10 codes and antiparkinson drug prescription | 17 | HR 1.004 (0.740–1.364) | Median neighborhood income and Aggregated Diagnosis Groups | 8 |

| Svensson et al. (12) | Denmark | Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) | Cohort | 1,594,548 | Operation codes | Record from DNPR using ICD-8,10 codes | 34 | HR 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | Age, sex, smoking, head trauma, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, Charlson Comorbidity Index, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease |

8 |

| Killinger et al. (13) | Sweden | Swedish National Patient Registry (SNPR) and Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) | Cohort | 1,698,000 | ICD codes | ICD-7,8,9,10 codes | 52 | OR 0.831 (0.756–0.907) | Sex and urban/rural municipality | 8 |

| Palacios et al. (14) | United States | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) | Cohort | 138,698 | Self-report | Medical record | 26 | HR 1.08 (0.94–1.23) | Age, smoking, and pack-years smoking. Additional adjustment for postmenopausal hormone use in NHS | 7 |

| Liu et al. (15) | Sweden | Swedish National Patient Registry (SNPR) and Swedish Population and Housing Censuses |

Case–control | 3,224,650 | ICD codes | ICD-7,8,9,10 codes | 46 | OR 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | Birth year, sex, country of birth, highest achieved education, chronic obstructive pulomonary disease, comorbidity index, and number of hospital visits |

8 |

| Jain et al. (16) | United States | Medicare data | Cohort | 329,976 | ICD codes | ICD-9,10 codes | 15 | HR 0.916 (0.861–0.976) | Age, race, sex, comorbidities, cancers, socio-economic status, provider visits, count of visits, and residents of States | 9 |

| Koning et al. (17) | United States | TriNetX medical record | Combined case–control and cohort | 49,248 | TriNetX codes | ICD-10 code with documented ambulatory visit and antiparkinson drug prescription | 16 | OR 2.40 (1.15–5.02) | Prodromal motor and non-motor PD symptoms and Charlson Comorbidity index | 8 |

| Park et al. (18) | Korea | National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC) |

Cohort | 703,831 | Procedure codes | ICD-10 code and registration code for government co-payment | 13 | HR 1.42 (0.88–2.30) | Age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking | 8 |

| Wang et al. (19) | United Kingdom | UK Biobank | Cohort | 472,676 | Not reported, obtained from UK Biobank | Not reported, obtained from UK Biobank | 16 | HR 1.120 (1.016–1.234) | Age, gender, ethnicity, education level, alcohol intake, smoking, body mass index, Townsend deprivation index, hypertension, and Polygenic Risk Score |

7 |

Details of included studies.

3.2 Meta-analysis for appendectomy and risk of PD

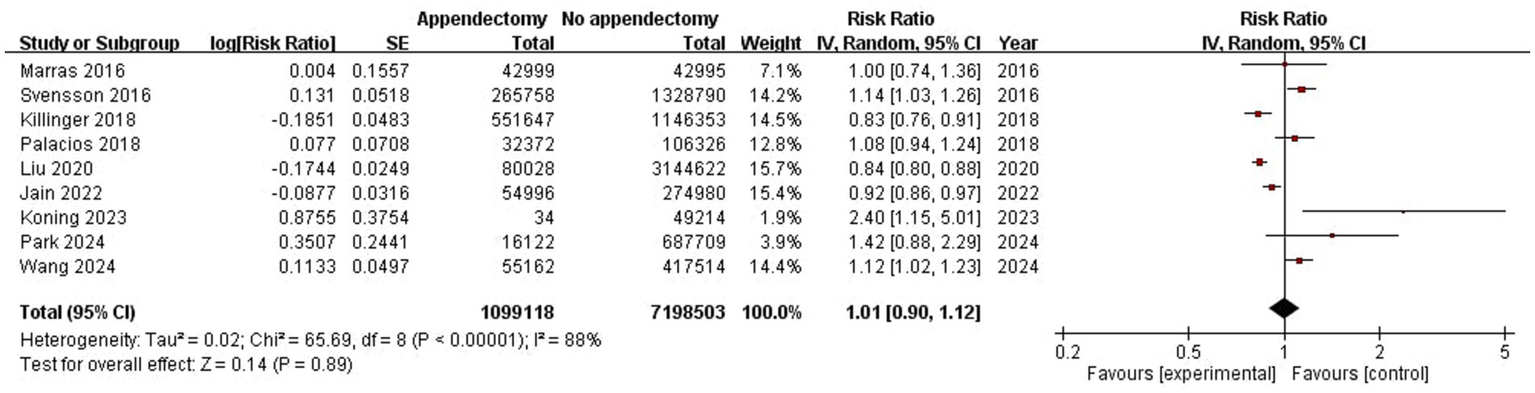

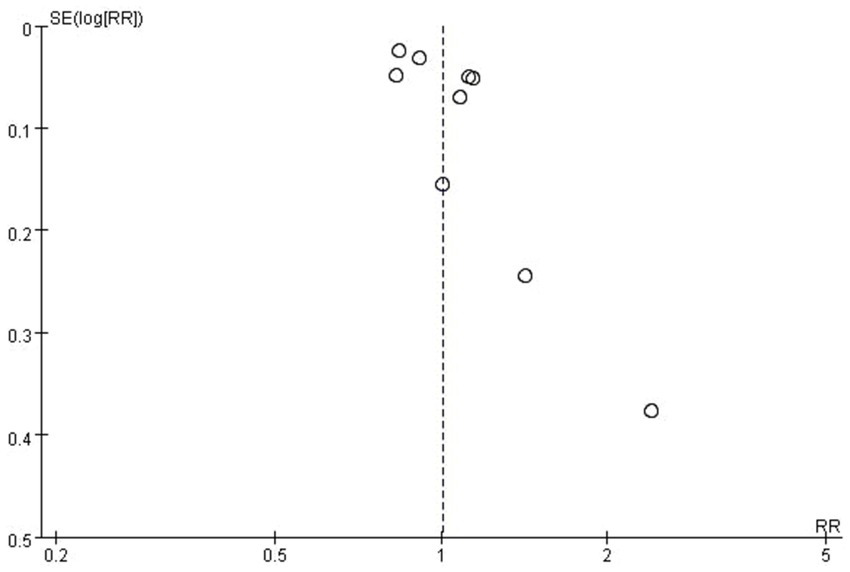

Pooled results from the 9 included studies demonstrated no statistically significant association between appendectomy and risk of PD (Pooled RR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.90–1.12, p = 0.89) (Figure 2). Significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 88%, p < 0.01). The funnel plot appeared asymmetrical, supported by a positive Egger’s test (p < 0.01), while Begg’s test was not significant (p = 0.18), suggesting the presence of potential small-study effects (Figure 3). Meta-regression analyses were conducted to evaluate potential moderators, including follow-up years, study design, geographic region, and appendectomy assessment method; none of these variables sufficiently explained the heterogeneity observed (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2

Meta-analysis forest plot of appendectomy and risk of PD.

Figure 3

Funnel plot of the meta-analysis of the included studies.

3.3 Subgroup analyses of appendectomy and risk of PD

Given that PD is a chronic disease that becomes more common with age, and all effect estimates were treated as RR due to PD prevalence being <10% in the general population, two subgroup analyses were decided to be performed before the beginning of the study (Table 3).

Table 3

| Subgroup | Number of studies | RR (95% Cl) | I2 static | Heterogeneity p | Overall effect p | Subgroup differences p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum follow-up years | ||||||

| >30 | 3 | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) | 93% | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| <=30 | 6 | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 77% | <0.01 | 0.73 | |

| Study design | ||||||

| Cohort | 7 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 83% | <0.01 | 0.30 | <0.01 |

| Case–control | 2 | 0.84 (0.80–0.89) | 87% | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Asia-Pacific | 4 | 0.93 (0.88–0.99) | 70% | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.73 |

| Europe | 5 | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | 93% | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Appendectomy assessment method | ||||||

| ICD codes | 5 | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 92% | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 |

| Non ICD | 4 | 1.12 (0.93–1.36) | 50% | 0.11 | 0.23 | |

Subgroup analyses for appendectomy and risk of PD.

For maximum follow-up years, studies were divided into two subgroups: >30 years and <30 years. A statistically significant subgroup differences p-value was observed, suggesting a possible presence of subgroup effect. However, substantial amount of heterogeneity was noted within both subgroups (>30 years: I2 = 93%, p < 0.01; <=30 years: I2 = 77%, p < 0.01), making the validity of effect estimate for each subgroup uncertain (Table 3).

For study design, studies were divided into two subgroups: cohort and case–control. One of the included studies used a design of case–control with complementary cohort. This study was treated as a case–control design in our study. A statistically significant subgroup differences p-value was observed, suggesting a possible presence of subgroup effect. However, substantial amount of heterogeneity was noted within both subgroups (cohort: I2 = 83%, p < 0.01; case–control: I2 = 87%, p < 0.01), making the validity of effect estimate for each subgroup uncertain (Table 3).

Additional subgroup analyses based on geographic region and appendectomy assessment method were conducted in response to reviewers’ feedback, which also demonstrated high heterogeneity within geographic region subgroups (Asia-Pacific: I2 = 70%, p = 0.02; Europe: I2 = 93%, p < 0.01) as well as within appendectomy assessment method subgroups (ICD codes: I2 = 92%, p < 0.01; Non ICD codes: I2 = 50%, p = 0.11). A statistically significant subgroup difference was observed in the appendectomy assessment method analysis (Table 3).

3.4 Sensitivity analyses of appendectomy and risk of PD

Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of findings to changes. Each study was omitted one by one in performing the sensitivity analyses. Since the two Swedish studies included had a potential partial overlap of populations with variations in ascertainment, a model excluding both studies was also performed to assess the potential effect of oversampling on skewing the results (13, 15). Results indicated that removing any single study did not significantly alter the conclusion that no association was observed between appendectomy and the risk of PD (Table 4).

Table 4

| Study omitted | RR (95% Cl) | I2 static | Heterogeneity p | Overall effect p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marras et al. (11) | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | 89% | <0.01 | 0.88 |

| Svensson et al. (12) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 85% | <0.01 | 0.73 |

| Killinger et al. (13) | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 88% | <0.01 | 0.49 |

| Palacios et al. (14) | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 88% | <0.01 | 0.97 |

| Liu et al. (15) | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 83% | <0.01 | 0.49 |

| Jain et al. (16) | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | 89% | <0.01 | 0.60 |

| Koning et al. (17) | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 88% | <0.01 | 0.84 |

| Park et al. (18) | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 89% | <0.01 | 0.90 |

| Wang et al. (19) | 0.99 (0.88–1.10) | 86% | <0.01 | 0.79 |

| Killinger et al. and Liu et al. (13, 15) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 78% | <0.01 | 0.17 |

Sensitivity analyses for appendectomy and risk of PD.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively evaluated the relationship between appendectomy and the risk of PD, analyzing data from nine observational studies involving a combined population size of approximately 8 million individuals. Our findings suggest no statistically significant association between appendectomy and the risk of PD. These results align with two previously reported meta-analyses on this topic from 2019 and 2020 (7, 8). Compared to previous meta-analyses, our study included additional studies and doubled the number, providing stronger evidence with newly available data (15–19). Notably, our analysis also incorporated one Asian study (18), addressing a gap in previous studies, which focused primarily on European and North American populations. Additionally, we applied a more rigorous quality criterion compared to previous reviews, including only articles with a Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score of > = 7.

Braak’s hypothesis proposed that PD may originate in the gut, with synucleinopathy transported retrogradely to the central nervous system, ultimately leading to PD (3). However, this hypothesis remains controversial. Some neuropathological studies have questioned Braak’s hypothesis, as the observed distribution pattern of synucleinopathy does not always align with it, suggesting that it may not sufficiently explain PD pathogenesis (20, 21). Although the appendix mucosa contains abundant α-synuclein, potentially serving as a reservoir for spread to the brain, our study did not support a protective effect of appendectomy against PD. While Braak’s hypothesis encompasses a broader range of proposed entry sites and mechanisms, our epidemiologic findings suggest that the appendix may play a less prominent role as an entry point in the pathogenesis of PD. Given PD’s lengthy prodromal period and the gradual development of pathology in the gastrointestinal tract, subgroup analyses by follow-up years were also performed, revealing consistent results with no observed differences between subgroups (22).

This systematic review and meta-analysis has some limitations. Despite including studies with large populations and high-quality scores (NOS > =7), the study pool was relatively small and primarily focused on Western, developed countries, limiting generalizability and the power of publication bias assessment. Publication bias and substantial methodological variability, such as differences in how appendectomy and PD were defined and assessed, were present across the included studies. Additionally, differences in adjusted confounders across studies limited the comparability among studies. These may contributed to the observed heterogeneity. Despite conducting subgroup analyses and meta-regression, no consistent moderators could be identified. Furthermore, while subgroups analyses offer valuable exploratory insights, these also raised risk of type I error. Results from subgroup analyses should be regarded exploratory and hypotheses generating rather than confirmatory.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HLC: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Investigation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Validation. YST: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HS: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Haojun Shi personally is a receiver of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82303376) and Shanghai Sailing Program (Grant No. 22YF1440400), part of which was allocated and used to cover the publication fee of this research article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used and acknowledged ChatGPT 4.0 for grammar check and manuscript editing. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1773653.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Kalia LV Lang AE . Parkinson's disease. Lancet. (2015) 386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3

2.

Emamzadeh FN Surguchov A . Parkinson's disease: biomarkers, treatment, and risk factors. Front Neurosci. (2018) 12:612. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00612

3.

Braak H Rüb U Gai WP Del Tredici K . Idiopathic Parkinson's disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm (Vienna). (2003) 110:517–36. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0808-2

4.

Hawkes CH Del Tredici K Braak H . Parkinson's disease: a dual-hit hypothesis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. (2007) 33:599–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00874.x

5.

Hawkes CH Del Tredici K Braak H . Parkinson's disease: the dual hit theory revisited. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2009) 1170:615–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04365.x

6.

Gray MT Munoz DG Gray DA Schlossmacher MG Woulfe JM . Alpha-synuclein in the appendiceal mucosa of neurologically intact subjects. Mov Disord. (2014) 29:991–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.25779

7.

Lu HT Shen QY Xie D Zhao QZ Xu YM . Lack of association between appendectomy and Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2020) 32:2201–9. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01354-9

8.

Ishizuka M Shibuya N Takagi K Hachiya H Tago K Suda K et al . Appendectomy does not increase the risk of future emergence of Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Am Surg. (2021) 87:1802–8. doi: 10.1177/0003134821989034

9.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

10.

Ou Z Pan J Tang S Duan D Yu D Nong H et al . Global trends in the incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability of Parkinson's disease in 204 countries/territories from 1990 to 2019. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:776847. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.776847

11.

Marras C Lang AE Austin PC Lau C Urbach DR . Appendectomy in mid and later life and risk of Parkinson's disease: a population-based study. Mov Disord. (2016) 31:1243–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.26670

12.

Svensson E Horváth-Puhó E Stokholm MG Sørensen HT Henderson VW Borghammer P . Appendectomy and risk of Parkinson's disease: a nationwide cohort study with more than 10 years of follow-up. Mov Disord. (2016) 31:1918–22. doi: 10.1002/mds.26761

13.

Killinger BA Madaj Z Sikora JW Rey N Haas AJ Vepa Y et al . The vermiform appendix impacts the risk of developing Parkinson's disease. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:5280. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar5280

14.

Palacios N Hughes KC Cereda E Schwarzschild MA Ascherio A . Appendectomy and risk of Parkinson's disease in two large prospective cohorts of men and women. Mov Disord. (2018) 33:1492–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.109

15.

Liu B Fang F Ye W Wirdefeldt K . Appendectomy, tonsillectomy and Parkinson's disease risk: a Swedish register-based study. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:510. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00510

16.

Jain S Rosenbaum PR Reiter JG Hill AS Wolk DA Hashemi S et al . Risk of Parkinson's disease after anaesthesia and surgery. Br J Anaesth. (2022) 128:e268–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.12.046

17.

Konings B Villatoro L Van den Eynde J Barahona G Burns R McKnight M et al . Gastrointestinal syndromes preceding a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease: testing Braak's hypothesis using a nationwide database for comparison with Alzheimer's disease and cerebrovascular diseases. Gut. (2023) 72:2103–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329685

18.

Park KW Woo HT Hwang YS Lee SH Chung SJ . Appendectomy and the risk of Parkinson's disease: a Korean Nationwide study. Mov Disord Clin Pract. (2024) 11:704–7. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.14031

19.

Wang Z Li M Ma D Guo M Hao X Hu Z et al . Association between appendectomy and Parkinson's disease from the UK biobank. Gut. (2024) 74:e10. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2024-332353

20.

Kalaitzakis ME Graeber MB Gentleman SM Pearce RK . The dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus is not an obligatory trigger site of Parkinson's disease: a critical analysis of alpha-synuclein staging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. (2008) 34:284–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00923.x

21.

Parkkinen L Pirttilä T Alafuzoff I . Applicability of current staging/categorization of alpha-synuclein pathology and their clinical relevance. Acta Neuropathol. (2008) 115:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0346-6

22.

Stokholm MG Danielsen EH Hamilton-Dutoit SJ Borghammer P . Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann Neurol. (2016) 79:940–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.24648

Summary

Keywords

Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson, appendectomy, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation

Chin HL, Tsang YS and Shi H (2025) Appendectomy and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1619236. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1619236

Received

27 April 2025

Accepted

01 July 2025

Published

21 July 2025

Corrected

29 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Katherine Roe, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, United States

Reviewed by

Jun Mitsui, The University of Tokyo, Japan

Irina G. Sourgoutcheva, University of Kansas Medical Center, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Chin, Tsang and Shi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haojun Shi, shihaojun910202@hotmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.