Abstract

Introduction:

Adult strabismus has a wide range of etiologies and necessitates clinical evaluation for appropriate treatment. Advancements in eye tracking technology show promise for the development of clinically accurate, automated evaluation and diagnosis of peripheral and central causes of ocular misalignment. However, multiple barriers prevent the incorporation of automated devices into clinical use. This study aimed to perform a quantitative meta-analysis and qualitative assessment of published reports of devices capable of automated strabismus evaluation.

Methods:

A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify reports of automated strabismus evaluation published between the years 1949–2025. Sixty-nine studies were identified through the literature search, and 17 of these studies qualified for statistical meta-analysis of automated device quality compared to gold standard clinical evaluation. We also analyzed factors affecting clinical use, including device portability, cost, and applicability toward patients with extreme angles of strabismus or anatomic variances, among others.

Results:

Meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled estimation of correlation of 0.87 [95% CI: (0.81, 0.91)] between results obtained by devices capable of automated strabismus evaluation in the literature and gold standard clinical evaluation. We identified advantages and limitations of previous models and offered guidelines to facilitate the advancement of device capabilities toward the level of gold standard expert clinical evaluation, and to facilitate the clinical implementation of these devices.

Discussion:

While barriers exist between experimental testing and clinical incorporation, automated strabismus technology shows promise for rapid, precise, and accurate evaluation of strabismus and has the potential to expand access to ophthalmic care in cases of low-resource or remote areas that lack local expert clinical personnel.

1 Introduction

Strabismus can be defined as a misalignment of the visual axes that may be congenital or acquired (1). The diagnosis has an estimated prevalence of 4% among the pediatric population and between 1 and 4% among the adult population worldwide (1–5). In individuals with normal ocular alignment, or orthophoria, both eyes can fixate on an object simultaneously. In those with strabismus, one eye is fixated on an object of interest, while the opposite eye is deviated away from the fixating eye (6). Strabismus may be either congenital or acquired in origin (3, 6). Congenital misalignment, which is often comitant (the misalignment is a constant, fixed amount in any direction of gaze), is the most common category of strabismus overall (3, 6). The etiology of congenital misalignment is incompletely understood but is suggested to arise from central nervous system pathways involved in processing and control of oculomotor function, including the lateral geniculate nucleus, midbrain fusion centers, striate cortex, and extrastriate cortical areas (3, 6). Acquired strabismus is typically incomitant and may be attributed to systemic conditions, such as vascular disease resulting in an aneurysm or ischemia, autoimmune disorders, demyelinating disease, systemic granulomatous disease, or muscular dystrophies (1–3, 6, 7). Misalignment can also arise as a sign of central nervous system infection, a neoplastic processes that raises intracranial pressure or affects the cranial nerves or extraocular muscles, or a cavernous sinus pathology (1–3, 6, 7). Additionally, acute trauma to the eye, extraocular muscles, or craniofacial structures can cause ocular misalignment (1, 3). Strabismus can result from adult-onset conditions affecting the tone, elasticity, or position of the extraocular muscles (e.g., thyroid eye disease, orbital inflammation, myositis, orbital or facial trauma, use of periocular implantable devices and age-related), or can re-emerge in adulthood as a decompensation of childhood strabismus, potentially with a history of surgery (1, 3, 6). Altogether, strabismus has a wide range of etiologies, and undiagnosed or new-onset strabismus warrants a timely and thorough evaluation to determine the cause and appropriate treatment for the best possible outcome (1, 3, 6).

Treatment of strabismus largely depends on the type and etiology of disease (1–3, 6, 7). Misalignment due to refractive error may be corrected with prescription lenses (1, 6). Often, strabismus requires surgical intervention to resolve diplopia or to improve a patient’s ability to make eye contact. The new onset of misalignment in older children and adults may suggest the need for further workup including imaging to assess for additional underlying pathology requiring interdisciplinary treatment (1, 6).

The gold standard measurement of ocular misalignment is achieved by using single and alternate cover tests and prisms, with alignment usually reported in prism diopters (8). Additional tests that assess for misalignment include the Hirschberg ratio or corneal light reflex, the Krimsky test, which uses prisms to center the corneal light reflex, the Brückner method, which uses an ophthalmoscope to assess for an asymmetric red reflex, the Hess screen test, the Lancaster red-green test, or synoptophore testing (7–10). Complete clinical evaluation of strabismus requires highly trained orthoptists, strabismus surgeons, or neuro-ophthalmologists who are trained in performing a sensorimotor exam and determining if additional systemic work-up or imaging is necessary (11, 12).

Multiple barriers exist between patients and appropriate evaluation of ocular misalignment. Evaluation of strabismus at any age should be timely, as undiagnosed strabismus can have consequences which range from decreased quality of life to significant morbidity or mortality, depending on the cause (4, 13, 14). Evaluation of strabismus in clinic is time-consuming and requires extensive clinical experience for examiners to accurately quantify misalignment (1, 11). Studies show that access to clinical experts trained in strabismus evaluation varies depending on geographical location and in some cases, socioeconomic status (15, 16). Additionally, the literature is lacking regarding guidelines for imaging in the setting of acute-onset misalignment, which often leads to unnecessary imaging and an inefficient use of healthcare resources (17).

Using automated systems for strabismus assessment would increase timely access for diagnosis and treatment for patients and reduce subjective measurement variability (12, 18). Concerning the pediatric population, automated strabismus and motility evaluation is under investigation as a tool to gain insight into infant eye movement, tracking, and cognitive development (19). Developing a clinically accurate, automated method of strabismus and ocular motility evaluation has become a popular field of technological research and development (8, 20–22). Previous devices that have been tested with the goal of assessing ocular deviation have applied a range of techniques, from the use of photographs to detect deviation in the nine cardinal gaze positions to the use of an automated application of the Hirschberg test, to the use of video-based pupil-tracking software to accurately estimate the degree of misalignment (21, 23, 24). More recently, the utilization of artificial intelligence and the adaptation of virtual reality head-mounted devices, many of which were originally developed for entertainment and gaming, have shown promise in the development of a portable, easy-to-use evaluation of ocular misalignment (25, 26). Despite these developments, multiple barriers prevent incorporation of these devices into clinical use, including the challenge of designing virtual reality headsets that fit both adults and children, the limitation of some devices that screen for the presence of strabismus without quantification or characterization of the misalignment, measurement of extreme degrees of deviation, evaluation of paralytic strabismus, accurate tracking of ocular structures in cases of ptotic eyelids or small eyelid fissures, rapid testing protocols, accurate automated software analysis of video recordings, cost of instrumentation, and portability of equipment (11, 22, 27, 28).

The objective of this study was to systematically review the literature for quantitative and qualitative evidence with which to evaluate the accuracy, reliability, portability, and feasibility of clinical implementation of devices that perform automated strabismus measurement. Primarily, we questioned how well automated strabismus devices perform quantitative measurement and characterization of strabismus compared to gold-standard clinical evaluation. Secondarily, we questioned what technical and contextual factors limit clinical implementation of technologies capable of automated strabismus evaluation. This review aims to identify advantages and limitations of previously proposed device models and to propose a framework for a device capable of automated strabismus measurement. This report also provides recommendations regarding the effective design of automated strabismus technology that compares to gold standard clinical evaluation. Additionally, this study proposes guidelines regarding the implementation of validation and feasibility studies to facilitate the incorporation of automated measurement technology into healthcare settings where clinical expertise on ocular misalignment is unavailable.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

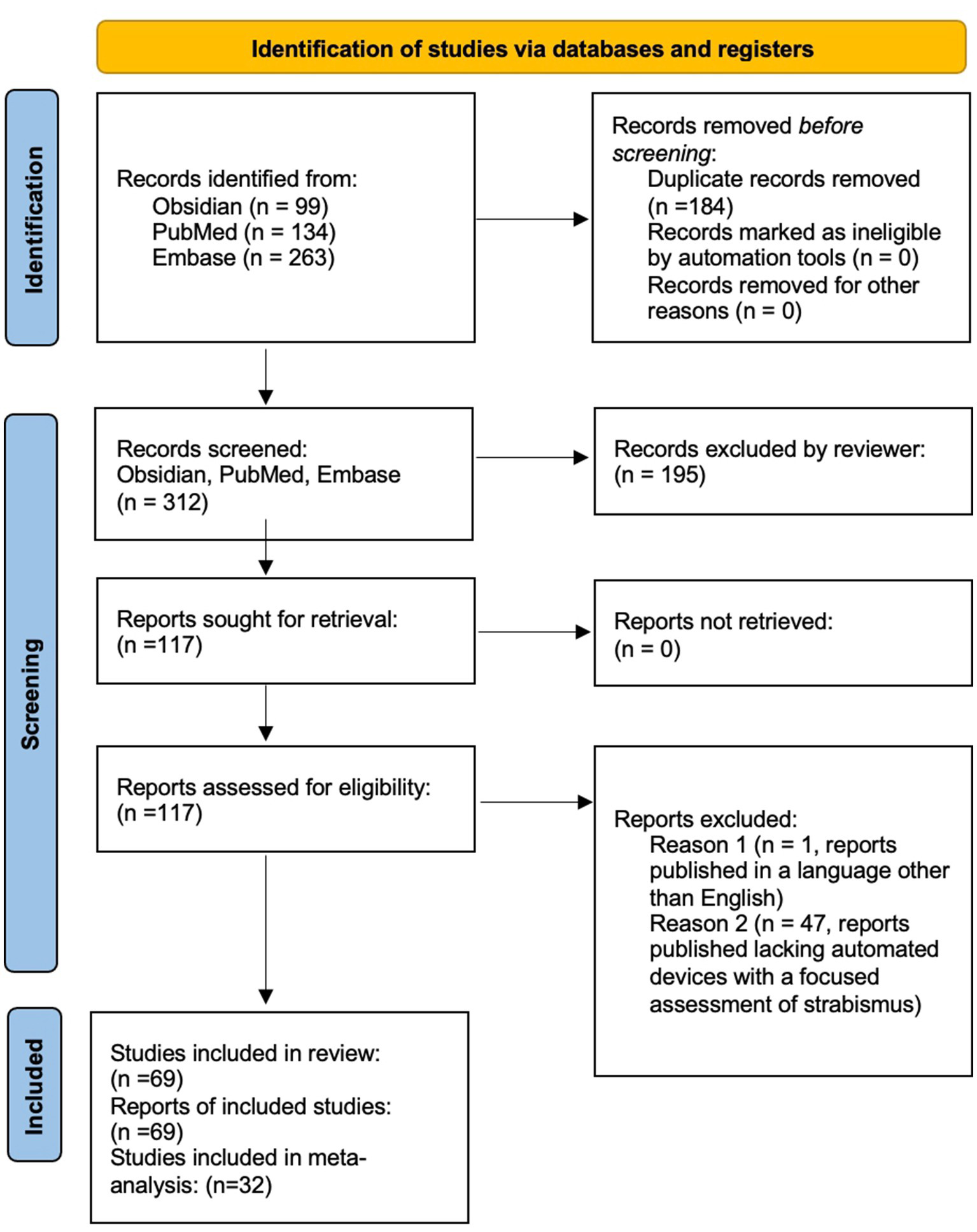

A review was performed of reports published between the years 1949–2025 to analyze the available online published scientific literature describing devices capable of performing automated strabismus measurement that have been tested on either normal research participants, strabismus patients, or both. Considering the PICOS framework, this study examined how the assessment of strabismus by devices capable of automated strabismus evaluation in adult and pediatric populations compared to gold standard clinical evaluation. Outcomes considered included the accuracy and validity of strabismus detection and measurement in various gaze directions, as reported in various study designs that reflect the diversity of technological advancements reported in the literature. Data was collected through searches across the following platforms: Obsidian, PubMed, and Embase. Obsidian software was used to perform an advanced search. For this project, five folders were created in the Obsidian vault: Bibliographies, MeSH Terms, Original Bibliography, Project Notes, and Search Notes. After the initial literature search was conducted, individual notes were made for each MeSH Term assigned to the relevant articles. Then, individual notes were created for the citations of the articles and placed into the “Original Bibliography” folder. Each citation note included the article citation, bidirectional links to the notes of the assigned MeSH Terms, and the bibliography of the article. Notes were also created and linked for each citation on each bibliography list. These notes were placed in the Bibliographies folder. In the end, the MeSH Terms folder contained 157 notes, the Original Bibliography folder contained 52 notes, and the Bibliographies folder contained 814 notes. The most commonly used MeSH Terms were identified based on the number of links to the MeSH Term note, including “Humans,” “Child,” “Adult,” “Male,” “Female,” “Strabismus/diagnosis,” “Strabismus/physiopathology,” “Strabismus/diagnostic imaging,” “Reproducibility of Results,” “Vision, Binocular/physiology,” “Diagnostic techniques, ophthalmological,” “Fixation, Ocular/physiology,” “Esotropia/diagnosis,” “Exotropia/diagnosis,” “Vision Tests/methods,” “Image Processing, Computer-Assisted/methods,” “Sensitivity and Specificity,” “Vision Screening/instrumentation,” “Observer variation,” “Oculomotor muscles/pathology,” “Optics and photonics/instrumentation,” “Automation.” Two search statements were created based on these terms, the first as: (“Strabismus/diagnosis”[Mesh]) AND (((((“Diagnosis, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh]) OR (“Image Processing, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh])) OR (“Neural Networks, Computer”[Mesh])) OR (“Algorithms”[Mesh])) OR (“Pattern Recognition, Automated”[Mesh])), which produced 117 results, and the second as: (“Strabismus/diagnosis”[Mesh]) AND ((“Diagnosis, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh]) OR (“Image Processing, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh])), which produced 99 results. The date of last search using Obsidian was June 17, 2024. Additionally, the databases PubMed and Embase were used. PubMed search terms included “automated strabismus” and “automated strabismus evaluation.” yielding 134 search results. Embase search terms included ‘automated strabismus’ OR (automated AND (‘strabismus’/exp. OR strabismus)),” “‘automated strabismus evaluation’ OR “(automated AND (‘strabismus’/exp. OR strabismus) AND (‘evaluation’/exp. OR evaluation))” and “‘automated strabismus evaluation’ OR (automated AND (‘strabismus’/exp. OR strabismus) AND (‘evaluation’/exp. OR evaluation))” yielding 263 search results. After pertinent articles were extracted, their references were consulted for additional relevant literature. Duplicate search results were filtered from the included studies. Inclusion criteria included literature that was published and peer-reviewed, studies that were published in the English language, studies demonstrating the use of technology capable of automated strabismus detection and/or quantification, and studies validating or evaluating technology capable of automated strabismus detection and/or quantification. Exclusion criteria included studies that were unpublished or lacking peer review, studies that were published in a language other than English, or if the study pertained to automated assessment devices that evaluated conditions excluding strabismus. The studies were screened, read, and evaluated for inclusion in the study. At times, multiple studies from the same research group were included in the context of ongoing technological development by that group, or if distinct studies included updated hardware, software, or protocols of the same device, or included different technologies developed by the same research group, or included different subjects that were tested in the separate studies. The inclusion of these studies corresponded with our goal to analyze published studies pertaining to the development and clinical implementation of automated strabismus evaluation. The date of last formal search was October 30, 2024. Three reviewers screened records and assessed abstracts, and one reviewer assessed studies in full-length text for eligibility. In total, 69 articles met criteria for evaluation and were included in this review, and 32 studies were included (Figure 1). In the meta-analysis (see section “Statistical meta-analysis”). Studies not included in the meta-analysis were either included in the brief summary table (Table 1) or addressed in the Discussion.

Figure 1

PRISMA diagram outlining literature review search methods.

Table 1

| Study | Study population | Method | Eye tracking feature | Gaze position assessed | Fixation target distance | Validation method | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guyton et al. (44) | Adult and pediatric; Patients with strabismus; n = 6; Age range: 8–47 years | Remote infrared television camera | Pupil center | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 80 centimeters | Hess-Lancaster; alternate cover test | Out of 1,188 horizontal and vertical measurements taken with all techniques, only 2.7% differed from the mean value for a particular test by more than 2.0 prism diopters, with the largest difference from the mean reported as 4.0 prism diopters. | True accuracy of remote haploscope testing and infrared television eye tracker testing is difficult to determine due to the lack of reported comparison with a manual, gold standard APCT. |

| Kault et al. (92) | Patient with strabismus; n = 1; Age unknown | Robinson’s Model, Reverse Model, and XEYE Package computer programs creating a model of strabismus and surgical planning. | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified | Retrospective comparison of the computer model to the surgical planning and outcome of a prior case | “The case presented in Results should be regarded only as an illustration of XEYE since evaluation will require examination of a number of cases with strabismus measurements made under precisely standardized conditions.” | A limited number of patients (n = 1) limits the power of the study. A retrospective comparison makes conclusions of validity and accuracy difficult. |

| Campos et al. (93) | 1 eye used as demonstration of the device model; Age unspecified | Remote infrared television camera | Pupil | Unspecified | Unspecified | Prior surgical planning and outcome | Descriptive study | Descriptive study |

| Thompson et al. (94) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 38; Age range 6–81 years | Automated Hess screen test, remote device (AHS) | Patient-operated button to signal viewing target is centered on screen | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 25 centimeters | Electronic Hess screen test (EHS) | The electronic Hess screen test results were found to be slightly more accurate than the automated Hess screen test in the production of an accurate strabismus diagnosis. | “[T]he panel of experts were all experienced at interpreting the motor fields measured using an EHS but had no previous experience interpreting AHS data.” |

| Schiavi and Orciuolo (95) | Age, Strabismus status, and number of patients unspecified | Remote infrared television camera | “Position of pupil relative to second image” | Primary | Distance (5 meters) and near (33 centimeters) | Validation method not discussed; Largely descriptive paper of new automated strabismus measurement model | No statistically analyzed quantitative results available. | Descriptive paper lacking objective numeric measurements of tested patients for comparison to gold standard APCT. |

| Miller et al. (96) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants with induced/simulated strabismus; n = 10; Age unspecified | Remote infrared video camera | Corneal light reflex compared to pupillary axis/ Hirschberg test | Primary | 1 meter | Known value of artificially-induced strabismus | “Statistically significant linear correlation of Hirschberg horizontal reflex deviation with asymmetric fixation of pseudo-esotropia…(p < 0.05).” | (Discussed by the authors:) A spherical cornea was assumed to calculate centroid of Purkinje reflex; Most pupils appeared ellipse in shape, causing potential decentration of the image plane with respect to the eye midpoint on imaging; |

| Bos and de Graaf (43) | Adult; Strabismus status unknown; n = 7; Age range 19–45 years | Head-mounted goggles with video oculography | Details within iris structure | Primary | 2 centimeters | Control “reference image” | “The implementation, applying averaging over ocular torsion determined in partitioned iris images, yields a theoretical resolution of 5′ of arc. In a control experiment with an artificial eye, the accuracy showed to be better than 14′ of arc.” | Limited sample size and without testing on patients with torsional strabismus. |

| Miller et al. (49) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants with induced/artificial strabismus; n = 18; Age range 20–40 years | Remote camera employing the Bruckner test | Coaxial fundus reflex | Primary | 254 centimeters | Known value of artificially-induced strabismus | Results shown only in graph format (see original paper), numerical data not provided in table or manuscript. | Pupillary size assumed constant, but observed to change image to image; Unexplained variation of pupil brightness during testing; Authors noted significant camera noise. |

| Hasebe et al. (34) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 87; Age range 4 months-75 years | Remote infrared television camera | Corneal light reflex, pupillary center (decentration of light reflex from pupil center measured) | Primary | 140 centimeters | APCT | “The 95% limits of agreement between the Hirschberg measures and the PACT were within ±7.8° or ±13.7 PD. The average (± SD) Hirschberg ratio was 12.3 ± 1.2°/mm or 21.8 ± 2.1 PD/mm.” | Measurement was limited in participants with large angles of deviation; Reported measurement error due to intersubject variance in Hirschberg ratio. |

| Hunter et al. (97) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants; n = 16; Age unspecified | Remote reitnal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 1.5 meters | Normal subjects tested, some but not all (unspecified), had examination by ophthalmologist confirming normality | “RBS can be used for remote, noninvasive, continuous monitoring of true foveal fixation within 61°, without strict restrictions on head position or the need for head-mounted appliances.” | “Although many of the subjects had documentation of normal eye examinations including normal ophthalmoscopy, this was not performed routinely on all subjects.” The study lacks comparison with gold-standard measurement for validation. |

| Simons et al. (45) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 100; Age range 4 months to 12 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 1 meter | APCT | The range of sensitivity of the MTI Photoscreener (screen for amblyogenic risk factors) in detecting strabismus was: 23 to 50%. Among clinical observers, the range of sensitivity for detecting strabismus was: sensitivity = 23 to 50%. | “The photoscreener had a low sensitivity even for manifest strabismus.” The authors also note the importance of adequate pupil size for effective screening, which could limit testing on patients with abnormal irises. |

| Scott et al. (98) | Monkey; n = 1 | Head-mounted liquid crystal shutters that perform automatic occlusion of eyes for alternating cover test | Ocular misalignment during cover tests | Primary | 50 centimeters | Alternating cover test, single cover test | “The shutters produced occlusion of each eye as effective as that of an opaque plastic occluder used in previous experiments that required monocular viewing. Heterotropias were detected and recorded in monkeys and closely resembled those observed in human patients. It was also possible to detect heterophorias by actuating the shutters alternately.” | Small sample size, not tested on humans with strabismus, strabismus assessed only in primary gaze. |

| Schaeffel (66) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants; n = 24; Age range 25–47 years | Remote infrared video camera | Corneal light reflex | Multiple gaze positions to calibrate kappa angle and Hirschberg ratio | 90 centimeters | No gold-standard testing; Data compared to data in prior literature | Angle kappa and Hirshberg ratio were highly correlated in both eyes of the subjects. | The authors note that the gaze tracker requires a smooth cornea and cannot be used in patients with a history of refractive surgery. Data was not compared to gold-standard measurement, limiting validity. |

| Hunter et al. (40) | Adult; Non strabismus patients (n = 21), Strabismus patients (n = 4), Age range 20–58 years | Remote retinal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Primary | 45 centimeters | Previous diagnosis strabismus | Detected binocularity (representing alignment) by retinal birefringence was significantly reduced in participants with strabismus compared to non-strabismus participants, suggesting the device may function as a screening tool. | Lower scores of binocularity were found in participants with smaller pupils, likely (per the authors) as a result of reduced light detection versus misalignment. Also, signal quality was noted to be lower in those with uncorrected myopia. |

| Hunter et al. (35) | Adult, Non-strabismus participant (n = 1), Strabismus patient (n = 1) | Remote retinal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Four ordinal directions | 40 centimeters | Data from strabismus patients compared to data collected from non-strabismus patients within the same study | Measured binocularity was significantly reduced in participants with strabismus compared to non-strabismus participants, supporting the use of the device as a screening tool. | Lack of quantitative numerical data provided in the study. Lack of comparison between the study results from patients with strabismus with gold standard clinical testing. |

| Nassif et al. (50) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 40); Strabismus patients (n = 20); Age range 22–79 years | Remote retinal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Primary and the four ordinal gaze directions | 40 centimeters | Reported “gold standard” clinical evaluation by orthoptist | “Good binocular alignment was appropriately detected in all control adults, while all adults with constant strabismus received a “refer” score.” | The near point of fixation utilized by the screening device necessitated accommodation, which may be limited in older adults. |

| Vaswani and Mudgil (99) | Non-strabismus participants; n = 70; Mean age: 16 years | The test was developed with binoculars with prisms and colored filters used to subjectively orient parallel lines on remote computer screen. | Subjective report of research participant/ orientation of parallel lines | Primary | 2 meters | Unspecified | “The mean degree of cyclodeviation tilt in the right eye was 0.6 degrees for monocular viewing conditions and 0.7 degrees for binocular viewing conditions, with a standard deviation of approximately one degree. There was no statistically significant difference between monocular and binocular viewing,” supporting that the test may be used in the detection of cyclovertical strabismus. | Authors reported difficulty in testing outside of primary gaze position (which would present.difficulty in cases of patients with compensatory head postures). The test also cannot be used to test patients with constant diplopia due to their lack of fusion in primary position. |

| Van Eenwyk et al. (100) | Adult and pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 610, Age range 6 months to 6 years | A remote video-based system combining Brückner pupil red reflex imaging and eccentric photorefraction that captured images analyzed by artificial intelligence | Brückner reflex | Primary | Unspecified | “Strabismus examination” by a clinician | For a ‘refer/do not refer” result, the system showed an accuracy of 77%, compared to the “gold standard” clinical examination and correctly identified 82% of strabismic individuals, | Suggetss that the device can be used to screen for, but not quantify or characterize, strabismus. |

| Han et al. (71) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants; n = 15; Age range 19–65 | Remote infrared video recording system | Limbus | Primary | 40 centimeters (Maddox rod), 45 centimeters (limbus tracking system) | APCT, Maddox rod test | “Responses objectively recorded using the limbus tracking system exhibited similar standard deviations to the Maddox rod and the alternate cover test techniques.” | The authors note that the use of a target for binocular fixation may affect the accurate assessment of phoria in their study (see study for full details). |

| Model et al. (101) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants; n = 48; Age range:18–57 | Remote two-camera video tracking system that performs a fixation-free measurement of the Hirschberg ratio | Pupil center and three corneal reflexes | None- fixation-free procedure | 85 centimeters | Fixation-free measurements compared to fixation-based Hirschberg measurements | Fixation-free and fixation-based protocols were highly correlated (r = 0.95; p < 0.001) showed repeatability and consistency. | Study does not examine strabismus according to APCT gold standard measurements, however, is an important study for fixation-free testing of alignment in infants. |

| Model and Eizenman (46) | Pediatric; Non-strabismus participants; Age rang 6–16 months | Remote infrared video cameras used to measure Hirschberg ratio and angle kappa | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 85 centimeters | This study measured for repeatability between measurements of the Hirschberg ratio and angle kappa | “The average difference between two independent measurements of eye misalignment was −0.27° ± 0.38° and the 95% limits of agreement for repeated measurements were ±0.75. “The AHT procedure can provide more accurate measurements of ocular misalignment than the standard HT. It may, therefore, enable early and reliable detection of infantile esotropia that may lead to early treatment and increase the chances for normal visual development in these patients.” | Lack of testing on patients with strabismus and comparison to gold standard APCT. |

| Almeida et al. (72) | Ages unspecified; Non-strabismus participants (n-30); Strabismus patients (n = 15) | Static photograph | Light reflection on cornea | Primary | 40–50 centimeters | “cover test” | “The methodology has produced results on the range of 100% sensibility, 91.3% specificity and 94% for the correct identification of strabismus. on digital images obtained from the Hirschberg test.” | Patients were excluded from testing with the following conditions, (among others listed in the study): horizontal or vertical yaw above 15 degrees, cornea or limbus aberrations, presence of nystagmus, inability to achieve 40s of arc on Titmus stereoscopic visual acuity test, inability to achieve 1.0/1.0 on the Snellen table. |

| Yang et al. (78) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n-32; Age range 0.5–58 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex and limbus | Primary | 0.33 meter | “2 independent ophthalmologists measured participants with Krimsky test and prism and alternate cover test” | “The 95% limit of agreement of inter-observer variability was 63.58 (6.1 prism diopters (PD)), 63.18 (5.4 PD) and 61.58 (2.6 PD) for the Krimsky test, PCT and the 3D Strabismus Photo Analyzer, respectively. The test–retest reliability was 62.88 (4.9 PD) for the 3D Strabismus Photo Analyzer versus the Krimsky test. The results of the Krimsky test and 3D Strabismus Photo Analyzer showed a strong positive correlation.” | Analysis limited to assessment of manifest strabismus in primary gaze, and the authors discuss that the software may not be able to measure more extreme deviations of gaze. |

| Awadein (102) | Adult; Strabismus patients; n = 82; Age range 22–56 years | Computerized version of the Lancaster red-green test | Patient subjective response | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 40 centimeters and 100 centimeters | Standard Lancaster red-green test | “The measured vertical and torsional deviation in the conventional test showed good agreement with both versions of the computerized test (limits of agreement < 5Δ for vertical measurements and < 3° for torsional measurements).” | APCT is considered the gold standard for strabismus assessment. |

| Yang et al. (60) | Non-strabismus participants (n = 30); Strabismus patients (n = 60); Ages unspecified | Remote infrared video camera with selective wavelength filter measuring angle kappa | Limbus, pupil, corneal light reflex | Primary | 0.33 meter | APCT | “Results of the PCT and selective wavelength filter analysis showed a strong positive correlation (R = 0.900, p < 0.001).” | Authors discuss that the software may not be able to assess patients with extreme degrees of misalignment, nystagmus, torsion, or abnormalities of ophthalmic anatomy. |

| Khumdat et al. (103) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; Age range 11–17 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex and limbus | Primary | 1 meter and 6 meters | Examination by “three specialists,” unspecified. | The methodology has produced results on the range 94.17% of accuracy, 97.23% of sensitivity and 73.08% of specificity. | The assessment may be limited by occlusion of the eye surface by eyelids, hair, inadequate illumination or insufficient contrast. |

| Silbert and Matta (36) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 151; Age range 1–6 years | Infrared static photograph | Measuring noncycloplegic refraction in partially dark-adapted mid-dilated pupils | Primary | 1 meter | “patients found to have amblyopia or amblyopia risk factors based on the 2003 AAPOS referral criteria” (including strabismus) | “A total of 151 children were included. The Spot had a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 74%. With the revised 2013 AAPOS referral criteria, the sensitivity was 87% and specificity was 74%.” | “This study was limited by the ophthalmology clinic setting and the screening of an enriched population.” (see paper) |

| Priglinger et al. (104) | Pediatric; Strabismus patient, n = 1 real patient, 3 simulated patients; Age: 1 patient followed from age 6 months to 7 years | Patient results were compared to computer-generated simulated patients | Not discussed | Nine cardinal gaze positions | Unspecified | Prism cover test, Hess-Lancaster test | Quantitative values were provided in Figures (see paper); The device software was used to proposed a diagnosis for underlying strabismus. | Limited number of patients tested limits the power of the study. |

| Irsch et al. (105) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 2), Strabismus patients (2); Age range 3–67 years | Remote retinal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Primary | Unspecified | Results (identification of strabismus during screening) compared to a previous diagnosis of strabismus | “Feasibility tests of focus detection with our new PVS using the improved target system with accommodation control suggest that the device has the potential to detect spherical focus within +/− 1.00 D” | Device demonstrates ability to screen for strabismus, but lacks ability to quantify or characterize strabismus. |

| Jost et al. (37) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 300; Age range 2–6 years | Remote retinal birefringence scanning | Retinal birefringence | Primary | 35–40 centimeters | “Gold standard” cover testing | “The sensitivity of the PVS to detect strabismus and amblyopia (0.97; 95% CI, 0.94–1.00) was significantly higher than that of the SureSight Autorefractor (0.74; 95% CI, 0.66–0.83). Specificity of the PVS for strabismus and amblyopia (0.87; 95% CI, 0.80–0.95) was significantly higher than that of the SureSight Autorefractor (0.62; 95% CI, 0.50–0.73).” | “[The] present study was conducted in a clinical setting, with a cohort enriched in children affected by the targeted conditions of strabismus and amblyopia; therefore, this study cannot directly assess the performance of the PVS in a primary care screening setting” |

| Lim et al. (32) | Strabismus patients; n = 120; Age unspecified | Static photograph | Corneal limbus | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 6 meters | Two independent observers measured the degree of inferior oblique muscle overactivation via a specified clinical grading scale, and interobserver reliability was measured | “The 95% limit of agreement of interobserver variability for the degree of inferior oblique muscle overaction was ±1.76 degrees, and ICC was 0.98. The angle of inferior oblique muscle overaction showed significant correlation with the clinical grading scale (R = 0.549, p < 0.001).” | Authors discuss that measurement error may arise due to clinician variability, that this method calculated inferior oblique overactivation using a 2D model, while the eye is 3D, that nine cardinal gaze position photographs may be difficult to obtain in patients with small eyelid fissures or in small children who are less cooperative with testing. |

| Garry and Donahue (106) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 155, Age range 2–9 years | Infrared static photograph | “The output from the screening instrument consists of 7 output values for each eye, including estimates of spherical and cylindrical refractive error, axis, and gaze vector.” | Primary | 3 feet | “Participants.received a gold standard pediatric ophthalmic examination, consisting of an assessment of.strabismus” | “Spot was 89% sensitive and 71% specific in detecting amblyopia risk factors.” | “One limitation to our design involved using an ophthalmology clinic patient population as opposed to a more typical screening population in the field with high numbers of normal children.” |

| Peterseim et al. (107) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 444; Age range 1–16 years old | Infrared static photograph | Unspecified | Primary | 3 feet | “A comprehensive examination was then performed, including.stereopsis and motility evaluation.” | “Compared to the ophthalmologist’s examination, the Spot sensitivity was 87.7% and the specificity was 75.9% in detecting amblyopia risk factors.” | “This study is limited by our testing of a high-risk population, which would be expected to decrease testability and alter the positive predictive value and negative predictive value.” |

| Seo et al. (62) | Unspecified | “Infrared camera and liquid crystal shutter glasses to simulate cover test and the digital video camera to detect the deviation of the eye.” | Pupil | Primary | Unspecified | Unspecified | This study is largely descriptive; Objective numerical data not provided. | Results given not compared to gold standard cover-uncover test. Number of tested patients not specified apart from one patient photographed. |

| Almeida et al. (20) | Strabismus patients; n = 40; Age range unspecified | Static photograph | Limbus vs. corneal light reflex | Primary, four ordinal gaze directions | Near: 40–50 centimeters, Distance: 6 meters | “The method’s accuracy was evaluated by comparing to the diagnoses presented by the specialist.” | “[The] method was demonstrated to be 88% accurate in esotropias identification (ET), 100% for exotropias (XT), 80.33% for hypertropias (HT), and 83.33% for hypotropias (HoT). The overall average error was 5.6Δ and 3.83Δ for horizontal and vertical deviations, respectively, against the measures presented by the specialist. | The Hirschberg test (upon which the automated test is based) is limited to patients who present with tropias. |

| Peterseim et al. (108) | Adult and Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status; n = 444; Age range 11 months-19 years | Remote video camera | Gaze criteria based on degrees displacement from the pupil center to the corneal light reflex. | Four ordinal gaze directions | 3 feet | “A comprehensive examination was then performed, including.stereopsis and motility evaluation.[by] four experienced pediatric ophthalmologists.” | “The sensitivity of the Spot to detect AAPOS-threshold strabismus was 77.17%; the specificity, 93.73%.” | “children with intermittent strabismus may have had straight eyes [during screening] but later appeared to have constant strabismus to the ophthalmologist on examination. In our study, these children would be included as false negatives. Conversely, children identified as having strabismus by the Spot may have demonstrated abnormality in “gaze” during the screening but are not included as AAPOS-threshold strabismus positive because their strabismus was intermittent on examination. These children with intermittent strabismus would therefore be considered false positives.” |

| Otero-Millan et al. (77) | Strabismus (torsion) patient; n = 1; Age unspecified | Head-mounted infrared video camera | Pupil center | Primary, +/− horizontal degrees, +/− vertical degrees, 35 degrees horizontally, 50 degrees horizontally | Unspecified | Scleral annulus search coil and video oculography | “The current setup operates binocularly at 100 Hz with noise <0.10 degrees and is accurate within 20 degrees of gaze to the left, to the right, and up and 10 degrees of gaze down.” | “First, at some gaze positions… the eyes might be largely occluded by the eyelids and eyelashes. Second, during fast movements of the head, any head-mounted display may suffer from slippage of the goggles on the head… Other limitations are… when changes in pupil size shift the relative position of the centers of the pupil and the iris, when pupils have very nonelliptical shapes, and when pupils are very small and the corneal reflection from the light-emitting diode illumination completely covers them… though with more than 20 subjects we have yet to find a subject in whom these issues precluded reliable measures of torsion.” |

| Kumar et al. (109) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 8); Strabismus patients (n = 8); Age range 50–70 years | Remote infrared video camera | Pupil center | Primary plus five unspecified positions in horizontal and vertical positions | 50 centimeters | Previous diagnosis of gaze palsy or abnormality, unspecified | “Our preliminary feasibility study with eight pairs of chronic (months) stroke survivors and healthy individuals revealed that gaze related indices in response to both static and dynamic visual stimuli may serve as potential quantitative biomarkers for stroke assessment.” | “Our preliminary feasibility study had some limitations. The gaze-related indices used in this study, though showed variations between the two groups of participants, did not have statistical significance, since our present study lacked sample power and our data was quite diffused. Also, we could have access to detailed neuroimaging reports of only two stroke patients which restricted us from doing in depth analysis of mapping one’s gaze-related indices to localized lesions in the brain. “ |

| Valente et al. (52) | Strabismus patients; n = 7; Age unspecified | Remote video camera | Pupil | Primary | 50 centimeters | “Specialist diagnosis,” unspecified | “To detect the presence of strabismus, the proposed method achieved a specificity value of 100%, and (2) a sensitivity value of 80%, with 93.33% accuracy in diagnosis of patients with exotropia. This procedure was recognized to diagnose strabismus with an accuracy value of 87%, while acknowledging measures lower than 1Δ, and an average error in the deviation measure of 2.57Δ” | “In detection of eye region and pupil location stage… the methodology failed in six cases due to situations in which the color of the pupil region, in dark eyes, was similar to the color above the pupil region. Another reason was that the shadow influence due to the close proximity of the patient’s body parts relative to the eye position in relation to the light source in the room.” |

| Maor et al. (42) | Pediatric; Strabismus patients (n = 409); Age range 3–9 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 40–70 centimeters | “All children underwent orthoptic assessment including.stereoacuity, cover/uncover and alternate prism cover test, and eye movement assessment.” |

“In children with phorias, the mean corneal light reflection location difference between the eyes was −0.10 ± 0.14 mm in primary position and −2.02 ± 0.39 mm in off-center fixation. Using a threshold of ±0.5 mm on either side of zero for central and of 2 mm for off-center fixation, sensitivity to detect strabismus increased from 65.6% in central to 79.3% in off-center fixation, respectively. The calculation of specificity will require inclusion of a population of individuals without strabismus.” | “Selection bias was introduced by choosing 34 cases out of a consecutive series of 52 cases and selecting images that allowed easy manual image processing using generic image analysis software. Cases of dark irides (poor contrast between pupil margin and pupil), poor eyelid opening, and poor target fixation were eliminated because it was not possible to obtain accurate measurements from these photographs. Another type of selection bias was the inclusion of predominantly esotropic participants… Detailed analysis and correlation of orthoptic measurements of strabismus and camera-based measurements were not meaningful because the algorithm aims to detect manifest strabismus, whereas the orthoptic alternate prism cover test measurements taken reflected the sum of manifest and latent strabismus.” |

| Nesaratnam et al. (54) | Adult; Strabismus patients; n = 3; Age range 22–73 years | Head-mounted virtual reality headset | Lees screen test: foveal position | Primary | Unspecified | Lees Screen test (modification of the Hess screen test) | “The pattern of deviation obtained using the virtual reality-based test showed agreement with that obtained from the Lees screen for patients with a fourth nerve palsy, comitant esotropia, and restrictive thyroid eye disease.” | Limited number of patients tested limits the power of the study. |

| Kim et al. (33) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 30), Strabismus patients (n = 30); Age range 5–74 years | Computerized torsion test administered on liquid crystal display remote monitor; participants wore red–green filter spectacles (red–green glasses used for the Worth-four-dot test or LRGT) | Subjective reporting of visual images by subject | Primary: torsion testing | 50 centimeters | Lancaster red green test, double Maddox rod test | “Both the DMRT and CTT showed no significant test–retest differences in the strabismus and control groups. The DMRT and CTT results demonstrated an acceptable agreement. The reliability of the CTT was better than that of the DMRT. The LRGT showed low sensitivity for the detection of ocular torsion compared with the DMRT (40.0%) and CTT (39.1%).” | “[T]he patients with strabismus had various disorders, which could have resulted in variable test outcomes. Second, the age range of participants was wide… which may have affected the reliability of results in very young and aged patients.” |

| Weber et al. (38) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 17), Strabismus patients (n = 41); Age range 6–81 years | Head-mounted, infrared video goggles | Pupil | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 0.5 meter | Hess screen test | “There was good agreement between the strabismus video goggles and the Hess screen test in the measurements of horizontal and vertical deviation (intraclass correlation coefficient horizontal 0.83, 95% confidence interval [0.77, 0.88], vertical 0.76, 95% confidence interval [0.68, 0.82]). Both methods reproduced the characteristic strabismus patterns in the 9-point grid. In contrast to Hess screen testing, strabismus video goggle measurements were even possible in patients with comitant strabismus and visual suppression.” | “[The] goggles… have been designed for an average-size head [and]… they did not fit all patients equally well… The current goggles prototype is not equipped to correct for refractive errors… sometimes a shadow image of the laser target was perceived by the occluded eye… Currently, the software analyzes only horizontal and vertical deviations, and ocular cyclotorsion has not been implemented yet.” |

| Chen et al. (110) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 15), Strabismus patients (n = 10); Age range 3–63 years | Remote video camera | Unspecified | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 50 centimeters | “Ophthalmologist’s diagnosis” | “Experimental results on the dataset demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed system for strabismus diagnosis.” (See paper for details) | “The limitation of our system is that it cannot yet precisely measure the strabismus angle as the cover test with a prism, though the relative severity is quite accurate.” |

| Chen et al. (111) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 25), Strabismus patients (n = 17); Age range 25–63 years | Remote video camera, convolutional neural networks | Unspecified | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 50 centimeters | “[The participants] have been diagnosed by a professional ophthalmologist, and the diagnosis results are used as ground truth in this paper.” | “Experimental results demonstrate that… strabismus can be effectively recognized by our proposed method.” (see paper for details) | Objective numerical data not explicitly provided in comparison to gold-standard APCT results. |

| Chopra et al. (57) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 15), Strabismus patients (n = 15); Age range 33–67 years | “[Binocular OCT:] [T]he corneal vertex reflection in the fixing eye. was used as a surrogate for the visual axis. A line was drawn between the pupil margins at the posterior epithelium of the iris for both eyes. The angle between the lines was calculated as the angle of deviation” | Corneal vertex reflection | Primary | Unspecified | APCT | “The APCT and OCT measurements were strongly correlated for the horizontal (Pearson r = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.60–0.95; p < 0.001) and vertical (r = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.69–0.96; p < 0.001) deviations.” | “Inability to ascertain heterophoria or heterotropia… all participants with strabismus had a constant deviation. Those with intermittent deviations may not be identified using the current prototype setup… Refractive error can affect the size of the deviation, and the inability to correct cylindrical error may contribute to the differences that were observed between the methods” |

| Thorisdottir et al. (112) | Adult; Unknown strabismus status; n = 19; Age range 27–78 years | Digital KM screen test: The patient wears red-green goggles and performs the test on a remote computer screen | “The positions indicated by the patients are recorded on the computer.” | “Twenty-five different points are used to test each eye, creating a primary position as well as an inner and an outer quadrant at 15° and 30° from the primary position.” | 1 meter | Hess and Lees screen tests | “No significant differences were found between the results obtained by all three tests [n = 19 (p > 0.05)].” | “There are several limitations… Examiners [were not] masked to the results [of all three tests]… Second, our study cohort was small, and only half the group repeated the tests for testing the level of difficulty and duration but not for repeatability of the test results. Third, with congenital deviations, a habitual head posture can be difficult to overcome during testing.” |

| Mestre et al. (61) | Adult; Strabismus patients; n = 30; Age range 23–33 years | Remote infrared video eye tracker | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 40 centimeters | Cover-uncover test and modified Thorington test | “The signed mean differences between the heterophoria measured with the three tested methods were considerably close to 0 PD, which means that on average none of the methods were clearly biased toward more esophoria or exophoric values.” (See paper for more details) | The paper discusses an inability to detect and/or measure properly paralytic heterotropias, since in these conditions the secondary deviation (the deviation when the paretic eye is fixating) is always greater than the primary deviation. |

| Yoo et al. (75) | Pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 75), Strabismus patients (n = 83); Age range 0–4 years | Static infrared photograph | Corneal light reflex | Primary | Near: 0.33 meter, Distance: 5 meters | APCT | “The testability of infrared photographs using selective wavelength filters in children under 4 years of age was 85.6%. The mean angle of esodeviation was 11.3 ± 4.0 PD by manual measurements and 11.5 ± 4.4 PD by the infrared photograph analysis. Manual measurements and the infrared photograph analysis showed a strong positive correlation (R = 0.815, p < 0.001). The sensitivity and specificity of the infrared photograph analysis for detecting small-angle esotropia were 95.2 and 77.9%, respectively, with a cutoff value of 4.0 PD” | “Selection bias may be present, as this is a retrospective cross-sectional study… Not all children could perform the infrared photograph analysis, as they could not tolerate the few seconds with an occluder placed in front of their eyes… a few children (13.7%) were determined with the Krimsky test, which is subject to measurement error. Software is based on normative ophthalmic biometry. Therefore, the analysis of subjects who have extreme proportions falling out of the normal variation was limited.” |

| Pundlik et al. (56) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 139), Strabismus (n = 100); Age range 20–40 years | Smartphone application capable of assessing strabismus deviation through static photography as well as assessing patient performance of cover-uncover or alternate cover test through video camera recording | Corneal light reflex | Primary and intended horizontal deviation | 40 centimeters | APCT, modified Thorington test | “The gaze angles measured by the app closely followed the ground truth (slope = 1.007, R^2 = 0.97, p < 0.001), with a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 2.4Δ. Phoria measurements with the app were consistent with MT (slope = 0.94, R^2 = 0.97, p < 0.001, RMSE = 1.7Δ). Overall, the strabismus measurements with the app were higher than with Synoptophore (slope = 1.15, R^2 = 0.91, p < 0.001), but consistent with CTPN (slope = 0.95, R^2 = 0.95, p < 0.001). After correction of CTPN values for near fixation, the consistency of the app measurements with CTPN was improved further (slope = 1.01).” | “Use of population average [Hirschberg ratio (HR)] can lead to an error in individual measurements… It is likely that there are age-, sex-, or ethnicity-related differences in HR values… We also did not evaluate the effect of glasses on the accuracy of the app.” |

| Zheng et al. (113) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients (n = 19); Age range unspecified | Remote infrared video camera recording automated cover test | Iris/limbus, pupil | Primary | 33 centimeters | “[T]he ground truths of deviations in prism diopters were provided by manually observing and calculating the deviations of eyes for all samples.” | “Experimental results demonstrate that the deviation of strabismus can be well-evaluated by our proposed method. The accuracy was over 91%, in the horizontal direction, with an error of 8 diopters; and it was over 86% in the vertical direction, with an error of 4 diopters.” | “For the acquisition of data, there are obvious changes in the video brightness, due to the cover of the occluder. This might bring a perturbation for the algorithm, especially for the pupil detection. Second… a slight movement of the head that is not detectable to humans will cause a certain deviation in the detection of eye position, thus, reducing the accuracy of the final evaluation.” |

| Luo et al. (28) | Strabismus patients; n = 14; Age range unspecified | “Smartphone app to perform Hirschberg test for measuring manifest and intermittent ocular misalignment” | Corneal light reflex, iris center | Primary | 40 centimeters | Prism and alternate cover test | “As the linear regression analysis showed (slope = 1.02, R^2 = 0.94, p < 0.001), the app measurements of strabismus angles were consistent with clinical cover test measurements.” | “The app only provides magnitude of the misalignment, rather than any interpretation or diagnosis… Usually for patients with larger eye fissures, i.e., iris area being more revealed, the fitting will be robust and accurate. On the other hand, for patients with smaller eye fissures… the fitting may be prone to inaccuracies. The current version does not provide measurement of vertical misalignment…” |

| Maio et al. (69) | Non-strabismus participants (n = 5), Strabismus patients (n = 12); Age range “above 6 years old” | Head-mounted virtual reality headset with infrared video camera | Pupil tracking, eyeball diameter | Primary | “Minions” toy at 6 meters | Prism cover test | “The mean difference between the two techniques and the doctor’s results for all of the patients were all less than 0.7 degrees.” | “In some cases (such as young children), the headset is too big, which produces estimation errors…[Regarding] eyes that were too small or lush eyelashes that covered the pupil, the pupil center could not be accurately tracked.” |

| Yehezkel et al. (11) | Pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 69; Age range 3–15 years | Remote infrared video camera | Vector between pupil and corneal light reflection | Primary | 50 centimeters | APCT and cover-uncover test | “A high correlation was found between the automated and the manual test results (R = 0.9 and p < 0.001 for the horizontal deviation, and R = 0.91 and p < 0.001 for the vertical deviations, with 100% correct identification of the type of deviation). The average automated test duration was 46 s. The Bland–Altman plot, used to compare the 2 measurement methods, showed a mean value of −2.9 prism diopters (PD) and a half-width of the 95% limit of agreement of ±11.4 PD.” |

“…This method cannot be applied to patients with a large amplitude of nystagmus - not designed to measure torsion…could not distinguish dissociated vertical deviation (DVD) from vertical hypertropia.” |

| Zheng et al. (47) | Pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 3,021), Strabismus patients (n = 2,772) | Static photographs and deep learning algorithm for assessment of misalignment | Region of interest including pupils, iris, conjunctivae, eyelids, and rectangular regions encompassing the eyes. | Primary | Unspecified | APCT and Hirschberg test | “Using 5-fold cross-validation during training, the average areas-under-the-curve of the DL models were approximately 0.99. In the external validation data set, the DL algorithm achieved an AUC of 0.99 with a sensitivity of 94.0% and a specificity of 99.3%. The DL algorithm’s performance (with an accuracy of 0.95) in diagnosing referable horizontal strabismus was better than that of the resident ophthalmologists (with accuracy ranging from 0.81 to 0.85).” | Does not perform quantitative assessment of strabismus; Assessment of strabismus is limited to primary gaze. |

| Cheng et al. (51) | Pediatric; n = 113; Unknown strabismus status; Age range <18 years | Smartphone application capable of assessing strabismus deviation through static photography | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 40 centimeters | APCT | “The nurse obtained at least one successful app measurement for 93% of children (125/133). 40 were flagged for PACT, of which 6 were confirmed to have strabismus. Based on the ROC curve, the optimum threshold for the app to detect strabismus was determined to be 3.0△, with the best sensitivity (83.0%), specificity (76.5%).” | Experiment limited to assessment of strabismus in primary gaze. |

| Yeh et al. (53) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients (n = 38); Age range 13 to 65 years | Head-mounted infrared video camera with 3D virtual reality headset | Position of the central pupil in relation to corneal light reflex | Primary | 6 meters | APCT | “The angle of ocular deviation measured by the VR-based system and the APCT showed good to excellent correlation [intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC = 0.897 (range: 0.810–0.945)]. The 95% limits of agreement was 11.32 PD.” | “The sample size was relatively small. We did not correct for patient’s refractive error…we only compared the measurement by the VR-based system with that of the APCT, and we did not determine intra-observer and inter-observer data from measurements with the VR-based system. We included all types of strabismus, such as comitant and incomitant strabismus, which might also affect measurements. However, in order to simulate the APCT in a real clinic situation, we only measured the ocular deviation in the primary position.” |

| Huang et al. (48) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 30), Strabismus patients (n = 30); Age range unspecified | Static photograph | Deep learning face detection: pupil position | Primary | Unspecified | Comparison to the results of normal subjects evaluated with the same experimental method | “The average value of the iris positional similarity of normal images was smaller than one of the strabismus images via the method (p < 0.001). The sample mean and sample standard deviation of the positional similarity of the normal and strabismus images were 1.073 ± 0.014 and 0.039, as well as 1.924 ± 0.169 and 0.472, respectively.” | “Pupil center…can be unevenly blocked by the lids/lashes, leading to inaccurate center calculation…the localization of the medial and lateral canthus may not be perfectly accurate due to several possible factors (e.g., skin color, illumination, and inapparent facial contour), which has an impact on the measurement of the positional similarity of two eyes.” |

| Mesquita et al. (59) | Pediatric; Unknown strabismus status (n = 204), Strabismus patients (n = 22); Age range 5–15 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex compared to center of limbus | Primary | 40 centimeters | APCT and simple cover test | “Fraction measurements were used with two cutoff points of 6 and 11 prismatic diopters (PD). Results were compared according to their concordances, with a fair Kappa equal to 0.43 [95%CI = (0.38; 0.48)], which was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) at the cutoff point of 6 PD and Kappa equal to 0.49 (95% CI = [0.35; 0.61]), which was statistically significant (p < 0.042) in the cutoff point of 11 PD.” | “The mhealth application analyzes the images since the eye with a deviation is being observed tangentially to the cell phone’s camera and not at the right angle as interpreted by the ophthalmologist. This results in the contradiction among values found and it will be greater the deviation.” |

| Garcia et al. (two studies in one paper) (8) | Adult; Unknown strabismus status, n = 28; Age range 18–56 | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex, limbus for automated reference point | Primary | Near: 33 centimeters, Distance: 4 meters | APCT | “The application obtained a matching rate of 95.14% for the face and eyes. The application yielded a sensitivity of 92.86% for horizontal strabismus at distance and near fixation, however, with low specificity values (7.692, 14.81, and 8%).” | “Since binocular fusion was not disrupted, the application was limited to the measurement of manifest deviations and did not measure latent deviations.” |

| Garcia et al. (two studies in one paper) (8) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 8; Age range 12–57 | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex, limbus for automated reference point | Primary | Near: 33 centimeters, Distance: 4 meters | APCT | “The Bland–Altman plots derived from Study B showed bias values of application measurements between 3.625Δ and 6.125Δ with wide intervals of the limits of agreement. Repeatability of the measurements yielded bias values of −0.625Δ and 2.5Δ for horizontal and vertical strabismus at distance and 4.375Δ and 1.25Δ at near fixation, respectively.” | “Our existing data is skewed toward normal and exotropic subjects, with a lack of subjects exhibiting vertical strabismus – reflecting the population of strabismus patients referred to our clinic.” |

| Kang et al. (21) | Adult; Strabismus patients; n = 2; Age range unspecified | Static photographs and deep learning algorithm for assessment of misalignment | Corneal light reflex, limbus; Ratio of impaired eye movement to normal eye movement | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 1 meter | “[T]he areas of the limbi and sclerae for both eyes were manually annotated…for use as the ground truth images.” | “The segmentation models exhibited high performance, with 96.88% dice similarity coefficient for the sclera segmentation and 95.71% DSC for the limbus segmentation.” | “Several assumptions were made based on the limitations of analyzing three-dimensional objects in a 2D environment… (1) Both the limbus and sclera are perfect spheres (2) In adults, the radius of the sclera is 2.5 times longer than that of the limbus (3) The extension line of the corneal light reflex point penetrates the center of the eyeball…It was difficult to identify the location of the limbi in cases of small eyes with little exposure to the limbus area. Potential for the existence of differences according to the age or surgery status of the patient.” |

| Morrison et al. (41) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants with artificially-induced strabismus; n = 10; Age range 26–66 years | Head-mounted infrared video camera | Pupil | Five targets on the tablet (center, vertical and horizontal ± 8.5°). | 260 millimeters | APCT | “We found a significant correlation between the reference APCT and the Skew video-oculography (VOG) (Pearson’s R^2 = 0.606, p < 0.05). There was a good agreement between the two tests (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.852, 95 CI 0.728–0.917, p < 0.001). The overall accuracy of the VOG was estimated at 80.53% with an error rate of 19.46%. There was no significant difference in VOG skew estimations compared with the gold standard except for very small skews.” | “Our current study investigated artificially induced skew on healthy participants. Thus, it has not yet been tested on patients with pathological skews.” |

| Huang et al. (114) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants (n = 30), Strabismus patients (n = 30); Age range unspecified | Static photograph and meta-learning algorithm for assessment of misalignment | Corneal light reflex | Primary | 1 meter | “[Participants] underwent screening tests conducted by a professional ophthalmologist and the screening results were used as the ground truth to evaluate the classification results.” | “The proposed method achieved a classification accuracy of 0.805 with a sensitivity (correct classification of strabismus) of 0.768 and a specificity (correct classification of normal) of 0.842, whereas the classification accuracy of using meta-learning alone was 0.709 with a sensitivity of 0.740 and a specificity of 0.678.” | “[I]mage data only comes from a hospital in Busan; whether the result can be generalized to other regions remains to be verified… Second, images without cornea light reflex are the potential factors that affect classification performance… Third, [there may be] imprecise localization of the medial and lateral canthus due to the factors such as illumination, eyelashes, and inapparent facial contours.” |

| Luo et al. (76) | Adult and pediatric; Non-strabismus participants; n = 207; Age range 5–60 years | Static photographs and convolutional neural network algorithm for assessment of misalignment | Limbus | Nine cardinal gaze positions | 100 centimeters | “Manual measurement of the images was conducted…by another experienced ophthalmologist.” | “The intraclass correlation coefficients between manual and automated measurements of six extraocular muscles ranged from 0.802 to 0.848 (p < 0.001), and the bias ranged from −0.63 mm to 0.71 mm.” | “Participants with eyelid diseases were excluded from this study, because that abnormality of eyelid function or morphology would cause ocular measurements far from the real values…the effect of eyeball size had not been considered in this study…only participants aged below 60 years were included in the analysis…our deep learning method had not been validated in populations with ocular motility disorders or populations of other ethnicities.” |

| Rajendran et al. (22) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 39; Age range 3–41 years | Remote video camera performing automated cover-uncover test with infrared glasses | Vector between the corneal light reflex and pupil center | Primary | 50 centimeters | APCT | “The prism alternate cover test (PACT) manual measurements and the automated alternate cover test for measuring horizontal deviation, the manual measurement, and the automated eye track system showed a highly positive correlation (r = 0.932, p < 0.001). The Bland Altman plot analysis shows good agreement between the two measurements, with the mean difference between the two measurements being 1.55 PD, and the 95% limit of agreement was ± 10 PD.” | “[The method] is based on eye movement detection and hence not feasible for patients with paralytic strabismus…measurement is variable in cases with large-amplitude nystagmus…the automated tracker tests deviation only in the primary position of gaze…cannot detect torsion…small sample size…non-inclusion of patients with vertical deviations…measurements were performed for near deviation alone.” |

| Lou et al. (39) | Adult and pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 72; Age range 4 to 56 years | Static photographs and deep learning algorithm for assessment of misalignment | Height difference between the inferior corneal limbus of both eyes | Adducted position | 1 meter | “Manual measurement of IOOA based on the photographs in the contralateral gaze was conducted by an investigator” | “There were significant correlations between automated photographic measurements and clinical gradings (Kendall’s tau: 0.721; 95% confidence interval: 0.652 to 0.779; p < 0.001), between automated and manual photographic measurements [intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs): 0.975; 95% confidence interval: 0.963 to 0.983; p < 0.001], and between two-repeated automated photographic measurements (ICCs: 0.998; 95% confidence interval: 0.997 to 0.999; p < 0.001).” | “Deviation in the adducted position was not measured by alternate prism cover test…it was difficult to fit the corneal limbus by a full ellipse in a few cases of eyes with little exposure of the corneal area…diversity of sample was limited, because this study included more mild-to-moderate [inferior oblique overactivation] IOOA eyes than severe IOOA eyes…the present study measured IOOA based on two-dimensional photographs, whereas real eyes are three-dimensional.” |

| Azri et al. (73) | Pediatric; Strabismus patients; n = 44; Age range <16 years | Static photograph | Corneal light reflex, kappa angle calculation | Primary gaze | 1 meter | APCT | “The correlation between the angle measured by the PCT and the angle measured by Strabocheck® (SK) was strong (R = 0.87). The mean absolute difference in the angle measured by the two methods was Δ = 11.9+/− 9.8 diopters. The Bland–Altman plot shows a 95% interval limit between −30.0 [−34.4; −25.6] and 31.0 [26.7; 35.4] diopters.” | Misalignment assessed only in primary gaze. |

| Nixon et al. (27) | Adult; Non-strabismus participants (n = 7), Strabismus patients (n = 19); Age (mean) 58.7 ± 22.4 years | Head-mounted infrared video camera with augmented reality used for an automated alternate cover test | Pupil | Primary | 6 meters | APCT | “STARE was able to identify the presence of horizontal strabismus with an area under the curve of 1.00 (100% sensitivity and 100% specificity). The mean difference (bias) {95% CI} was 2.1 {−1.8, 9.9} prism diopters, and the 95% coefficient of repeatability {95% CI} was ±27.9 {14.8, 50.8} prism diopters. The Pearson correlation between APCT and STARE was r24 = 0.62, p < 0.001.” | “Headset…too big for use in young children…unable to measure torsion… STARE cannot be used in those with nystagmus…does not differentiate between manifest and latent deviations. Only horizontal deviations were considered in comparisons of size of deviation between APCT and STARE…no intra- or inter-observer data was recorded…ocular deviation was also only measured in primary position with STARE…small sample of patients.” |

| Gao et al. (55) | Age unspecified; Strabismus status unknown; n = 1 | Head-mounted infrared video camera with augmented reality and deep learning algorithm for assessment of alignment | Pupil | Six gaze points, unspecified | 1 meter | None reported | “The experimental results show that when the distance between the subject and the display is 1 meter, the eye tracking accuracy of the smart glasses can reach 1.0° with an error of no more than ±0.1°.” | Not compared to gold standard evaluation. Largely descriptive paper detailing software design. |

Summary of papers identified in literature search meeting inclusion criteria.

2.2 Statistical meta-analysis

Sixty-nine studies were identified through database search. Of these, 22 studies either examined Pearson correlation, Kendall’s tau correlation, intraclass correlation (ICC), or kappa statistics between the new techniques for strabismus assessment and the gold standard and/or clinical grading scales (Table 1). Because Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient measures a non-linear association between two quantitative continuous variables, we utilized a technique by Gilpin (29) to convert this correlation into Pearson correlation coefficient. For data characterized by non-continuous variables, Kappa coefficient and ICC were often reported, but they are not on the same scale even though they provide a measure of agreement between two techniques or two raters. In addition, Kappa deals with nominal data while ICC provides a more effective analysis of ordinal and interval data. Nominal data is used to label variables without any quantitative value. It categorizes data by labeling or naming values. The key characteristics of nominal data are: (1) no inherent order- the categories are distinct and separate, with no hierarchy or ranking among them, (2) data consists of mutually exclusive categories- each category is unique, and an item can belong to only one category, (3) uses descriptive names or terms to represent categories, without implying any numerical relationships. Ordinal data is a type of data that classifies variables into categories with a meaningful order or ranking. The key characteristics of ordinal data are: (1) data categories are ranked, having a clear order or hierarchy, such as from high to low, (2) the intervals between categories are not necessarily equal and numerical values can be used as labels, but these values do not represent equal intervals. We therefore reported their results separately from those of Pearson correlation and Kendall’s tau. To obtain a more accurate approximation of confidence intervals around the estimates, all correlations and ICC were transformed using the Fisher’s Z transformation (30):

where the standard error is expressed asand the sample size of each study.

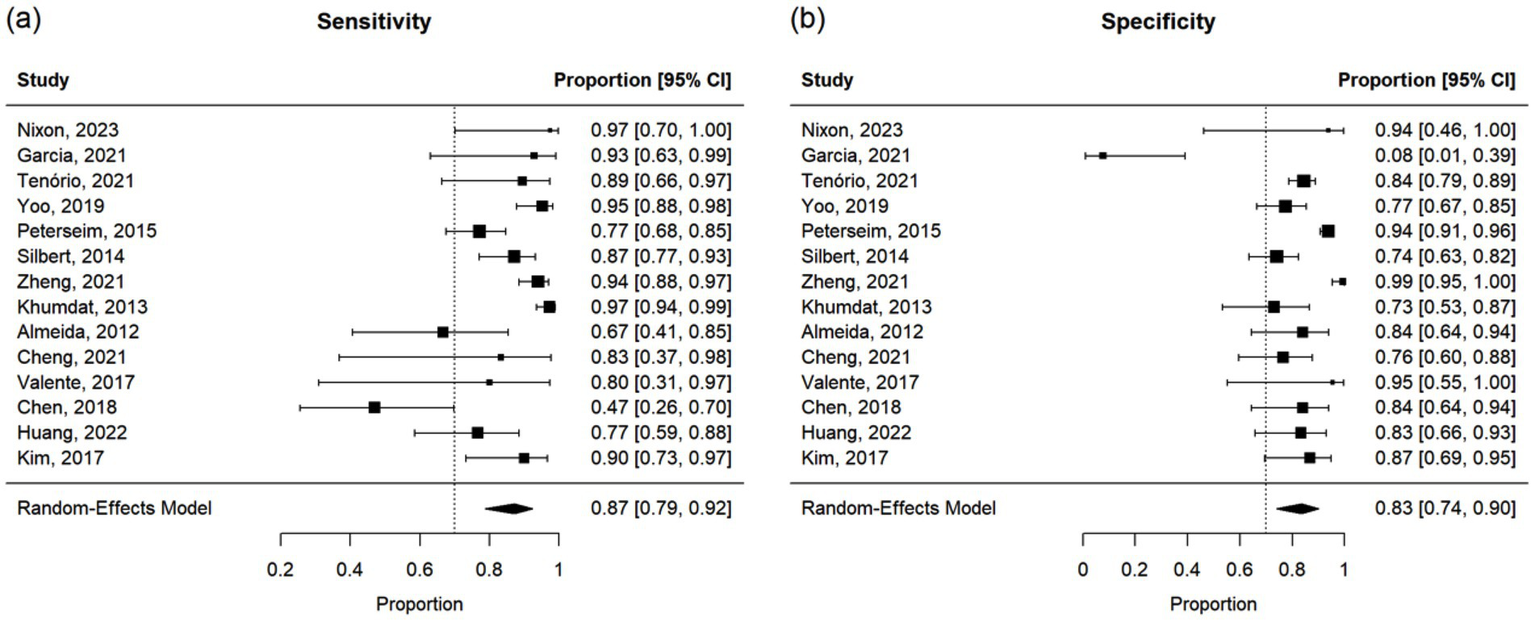

Additionally, of the 69 studies, 14 reported sensitivity and specificity of the new technique for the diagnosis of strabismus. Of these, three studies also provided a correlation. Because sensitivity and specificity are proportions, a logit transformation was performed before the meta-analysis to ensure approximate normality and variance stabilization.

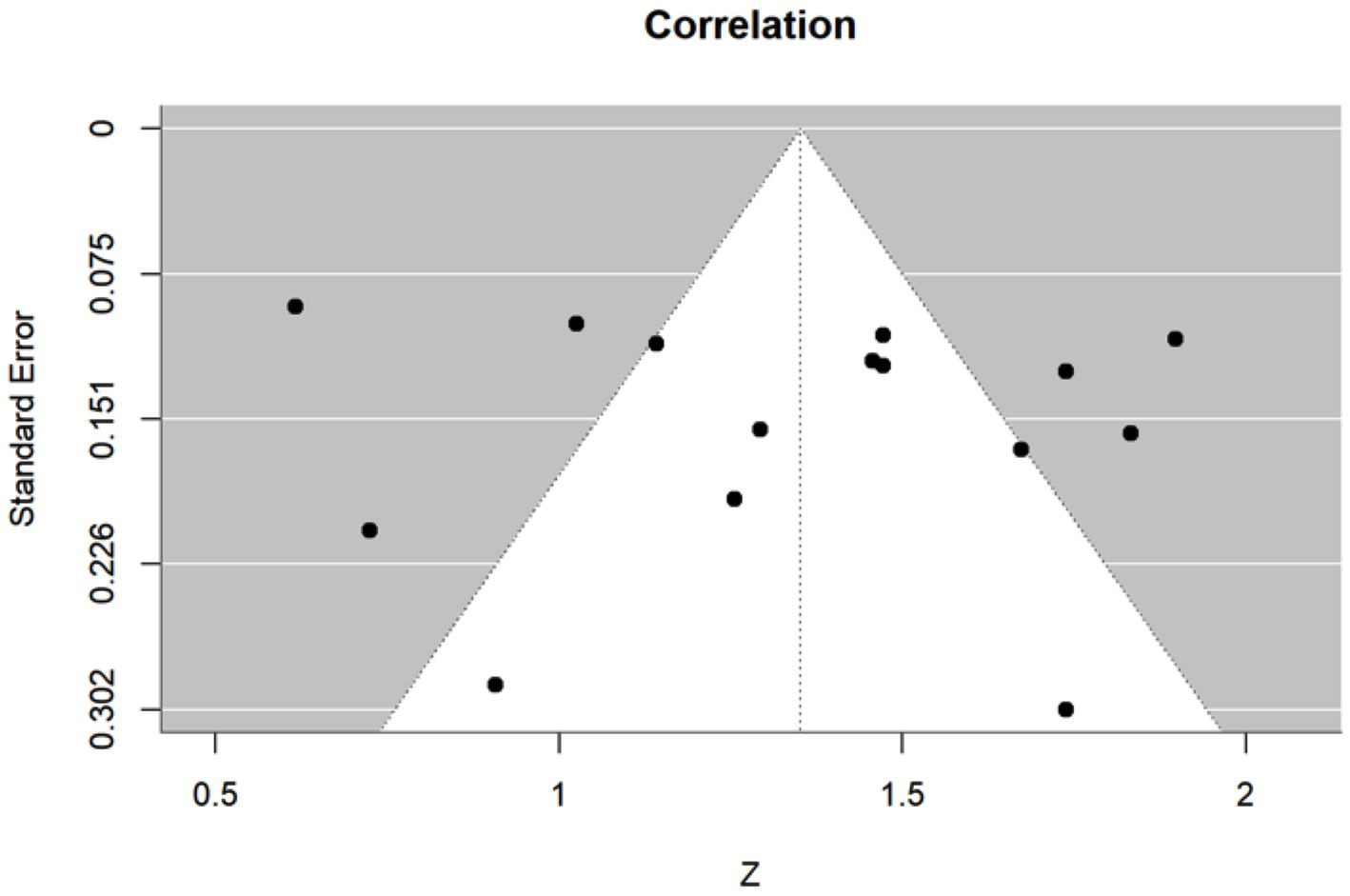

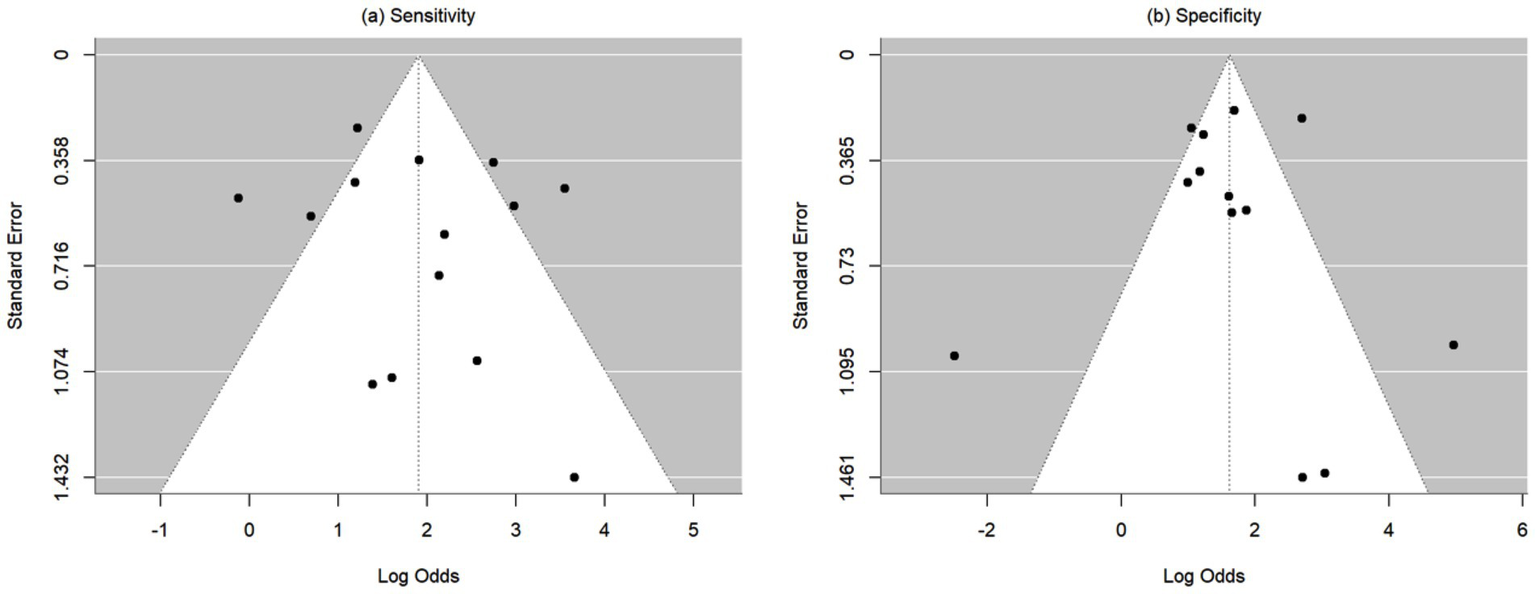

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and I-squared (I2) statistics as described by Higgins and Thompson (31). The I2 Statistic measures the proportion of total variation in observed effect sizes that is due to variance in true effects rather than random chance. The significance threshold for the Cochran’s Q test is set at alpha = 0.05. Publication bias for meta-analyses in the cases of correlation, sensitivity, and specificity was assessed by the Egger’s tests along with funnel plots. Funnel plots are visual aids for assessing bias or systematic heterogeneity. When random effect models are used, heterogeneity is usually accounted for in the modeling step; thus, the stress in the funnel plot is primarily on the presence or absence of publication bias. A symmetrical inverted funnel shape indicates an unbiased distribution of studies, whereas an asymmetrical shape may indicate selective reporting and/or other systematic biases. The x-axis on the plot represents the observed effect size while the y-axis represents the standard error.

All meta-analyses results were obtained under a random-effect model to allow for heterogeneity in the estimation process. R software version 4.4.2 was used to carry out the meta-analyses. Since the sample sizes available for each meta-analysis is limited, it was not feasible to account for multiple covariates in the estimations of the pooled correlation, intraclass correlation, sensitivity, and specificity. Studies included in the meta-analysis were those that provided, by the parameters described above, objective data from which statistical analysis could be performed. Studies that were not included in the meta-analysis were summarized in Table 1 or narratively evaluated in the discussion.

3 Results

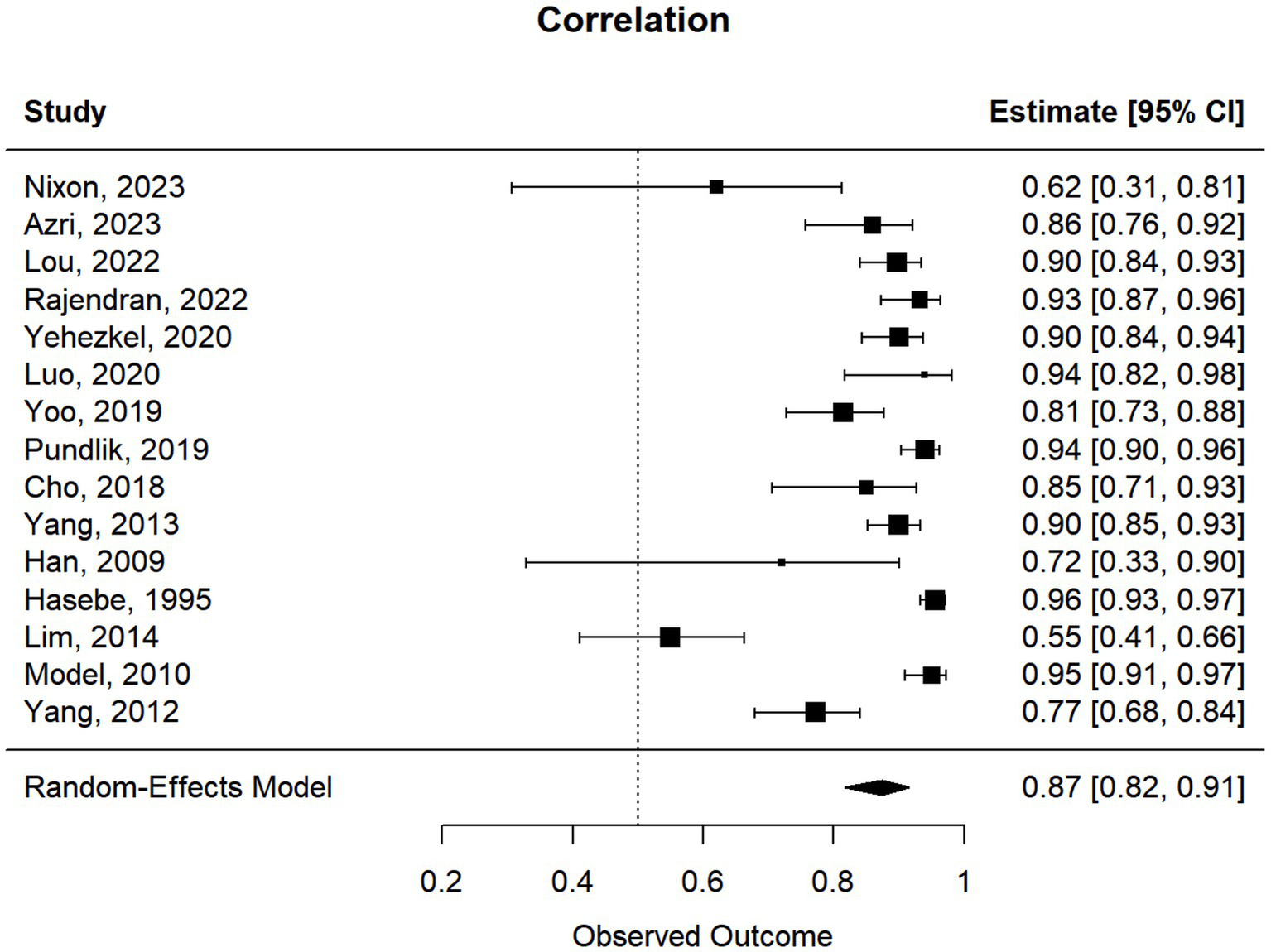

3.1 Meta-analysis of studies reporting Pearson correlations and Kendall’s tau

This meta-analysis included 17 studies out of 69 (24.64%). Their sample sizes ranged from 10 to 158 participants. The average (or median) age of the participants ranged from 2.8 to 58.7 years; and the reported correlations ranged from 0.549 to 0.956 (Table 2). Among the included studies, Nixon et al. (r = 0.62), Lim et al. (r = 0.549), and Yang et al. (r = 0.772) reported the lowest correlation values (27, 32, 33). Specifically, Nixon et al. evaluated an augmented reality headset with eye-tracking in a relatively small sample (n = 26), with measurements limited to horizontal deviations in primary gaze only, which may have introduced instability in correlation with APCT (27). Lim et al. used a clinical grading scale rather than APCT as the validation method, potentially introducing subjectivity and lowering the observed correlation (32). While static photograph methods have shown strong correlation with APCT in other studies, Yang et al. included a wide age range (0.5 to 58 years), suggesting possible variability in cooperation or diagnostic visibility across age groups (33). Figure 2 shows the estimates and confidence intervals post meta-analysis. The pooled estimation of the correlation was 0.87 [95% CI: (0.81, 0.91)]. In this analysis, the Cochran’s Q test for heterogeneity had a p-value of <0.001 and the I2 statistic was large (98.34%), suggesting that obtaining the overall estimate via a random effect model would provide an effective analysis. The funnel plot appeared approximately symmetric around the pooled estimate and the Egger’s test was statistically insignificant (p = 0.800; see Figure 3), indicating there was no evidence of publication bias. In other words, smaller studies did not consistently report stronger or weaker effects, which suggests that the results were less likely to be distorted by selective publication and supporting the robustness of the pooled findings.

Table 2

| Year | Country | Agea (Yrs) | New technique | Validation method | Sample Sizeb (Number of strabismus Subjects) | Correlation (r)/Kappa/ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nixon et al. (27) | United Kingdom | 58.7 ± 22.41 | Augmented reality headset with integrated eye-tracking | APCT | 26 (19) | r = 0.62 |

| Azri et al. (73) | France | 7.83 [3.58–17.3]2 | Static photograph | PCT | 44 (0) | r = 0.86 |

| Lou et al. (76) | China | 17.6 ± 12.71 | Deep learning-based image analysis | Hand measurement by ophthalmologists of same photographs provided to deep learning analysis software | 72 (72) | rc = 0.897 ICC = 0.975 |

| Rajendran et al. (22) | India | 13.64 ± 9.041 | Automated cover-uncover test | APCT | 39 (39) | r = 0.932 |

| Tenório et al. (59) | Brazil | [5–15]3 | Static photograph | APCT | 224 (22) | Kappa = 0.43 |

| Yehezkel et al. (11) | Israel | 7.17 ± 2.781 | Automated cover-uncover test and automated prism cover test | Cover-uncover test and APCT | 69 (69) | r = 0.9 |

| Luo et al. (28) | United States | NR4 | Smartphone app-automated Hirschberg test | PCT, APCT | 14 (10) | r = 0.97 |

| Yoo et al. (75) | South Korea | 2.8 ± 1.21 | Static photographs | APCT | 83 (83) | r = 0.815 |

| Pundlik et al. (56) | China | 13 [4–63]2 | Static photographs taken by smartphone app | APCT | 66 (66) | r = 0.97 |