Abstract

Objective:

Insomnia is a prevalent symptom among perimenopausal women, mainly attributed to estrogen-progesterone imbalance and neuropsychiatric factors, significantly impacting their quality of life. This article seeks to systematically evaluate the efficacy of integrated acupuncture-pharmacotherapy (AP) in treating perimenopausal insomnia (PMI), offering new insights for the management of insomnia in women.

Methods:

Searches were conducted in 8 databases: PubMed, Web of Science (WOS), Cochrane Library, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Biology Medicine Disc (CBM), Wanfang Academic Journal Full-text Database (Wanfang), and Chongqing VIP Database (CQVIP). Database searches extended through August 1, 2024. Endnote 20 was used to build the database and screen for eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The efficacy of AP for PMI were demonstrated by assessing 3 primary outcome measures (Effective rate, Hamilton Anxiety Scale [HAMA], Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndromes [TCMS]) and 5 secondary outcome measures (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI], Modified Kupperman Index [KMI], Luteinizing Hormone [LH], Follicle-Stimulating Hormone [FSH], Estradiol [E2]). The risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Data analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 and StataMP 15.0. Subgroup or sensitivity analysis was applied as necessary to address issues of heterogeneity. Regression analysis was used to determine whether the division of potential subgroups is reasonable. The evidence quality level was evaluated using the GRADEprofiler following the GRADE approach.

Results:

A total of 12 eligible studies comprising 969 PMI cases were ultimately included in this meta-analysis. Pooled results indicated AP had statistically significant benefits for PMI: Efficacy (Effective rate [RR = 1.22, 95% CI (1.13, 1.30), Z = 3.88, p < 0.00001]), Scores (HAMA [MD = −3.26, 95% CI (−3.79, −2.73), Z = 12.06, p < 0.00001]), TCMS [MD = −0.98, 95% CI (−1.21, −0.74), Z = 7.99, p < 0.00001], PSQI [MD = −3.12, 95% CI (−4.21, −2.03), Z = 5.63, p < 0.00001], KMI [MD = −3.96, 95% CI (−5.78, −2.15), Z = 4.28, p < 0.0001], and Hormone levels LH [MD = −10.16, 95% CI (−16.41, −3.91), Z = 3.18, p = 0.001 < 0.05], FSH [MD = −8.65, 95% CI (−13.67, −3.64), Z = 3.39, p = 0.0007 < 0.05], E2 [MD = 15.87, 95% CI (10.16, 21.58), Z = 5.45, p < 0.00001].

Conclusion:

AP demonstrates significant efficacy in treating PMI patients, offering an innovative integrative therapy with substantial clinical value. Future studies should involve more large-scale, multicenter RCTs with long-term follow-up.

Systematic review registration:

Introduction

Perimenopause represents a critical transitional period in a woman’s life, marking the shift from reproductive capability to menopause. According to the STRAW +10 criteria, it is characterized by a gradual decline in ovarian function and is divided into 2 substages: early perimenopause (Stage −2), marked by increased menstrual cycle variability and elevated early follicular phase FSH, and late perimenopause (Stage −1), defined by amenorrhea lasting≥60 days, significantly elevated FSH levels, and markedly reduced anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and antral follicle count (AFC) (1). This stage is accompanied by pronounced hormonal fluctuations and multisystem dysregulation, collectively manifesting as perimenopausal syndrome (PMS) (2). Among the most common and distressing symptoms is insomnia, affecting 30–50% of perimenopausal women. Emerging evidence suggests that the impact of insomnia extends beyond quality of life impairment, exerting a significant influence on cardiovascular and cognitive health through multifactorial pathways. Chronic sleep disturbances may contribute to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, heightened systemic inflammation, and increased sympathetic nervous system activity, all of which can promote atherogenesis and elevate the risk of myocardial infarction (MI). A longitudinal population-based study using data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study found that individuals with elevated levels of social dysfunction and anhedonia—core dimensions of psychological distress—had a significantly increased risk of developing MI over a 10-year period (3). Moreover, in patients already diagnosed with coronary heart disease (CHD), significantly worse scores across multiple domains of mental health, including depression, anxiety, and loss of confidence, were observed (4). These findings suggest a bidirectional interplay between cardiovascular vulnerability and psychological distress, wherein insomnia may act both as a consequence and as a precipitating factor through its neurobiological and behavioral effects. Understanding these interconnections underscores the importance of early intervention in sleep problems to mitigate downstream cardiovascular and cognitive complications.

Current therapeutic approaches vary between Western pharmacological interventions and Chinese herbal medicine. Pharmacotherapy typically includes sedative-hypnotics and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), which are effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms and preventing osteoporosis. However, long-term MHT use carries risks such as thromboembolic events and breast cancer (5, 6). In contrast, acupuncture as a core modality of (Traditional Chinese Medicine) TCM has garnered increasing attention for its multimodal therapeutic mechanisms. Evidence has already suggested that acupuncture exerts its effects through 3 primary pathways: (1) neuroendocrine regulation via the hypothalamic–pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis to stabilize hormonal levels (7); (2) neuromodulation, enhancing central neurotransmitters such as serotonin and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which contribute to improved mood and sleep quality (8); (3) immunomodulation, reducing inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are linked to neuroendocrine dysfunction and sleep disturbances (9). Recent advances in neuroimmunology have uncovered striking similarities in the pathophysiological pathways connecting neuroinflammation with concurrent sleep and cognitive disturbances. Studies of anti-CASPR2 encephalitis demonstrate that autoantibody interference with potassium channel complexes induces dual pathology—disrupting both memory consolidation (notably causing retrograde amnesia) and sleep architecture through combined hippocampal damage and inflammatory mediator release (10). This phenomenon bears remarkable resemblance to the cytokine-driven hippocampal sensitization seen in PMI, where elevated IL-6 and other inflammatory markers similarly impair memory networks and sleep–wake regulation. Such cross-condition parallels highlight immunoneuroendocrine pathways as critical therapeutic targets for sleep-cognitive comorbidities.

Currently, integrated AP has emerged as a promising strategy that may enhance therapeutic efficacy while making up the limitations of conventional pharmacological approaches (11). Preclinical studies have suggested that acupuncture may influence neuropharmacological pathways, potentially affecting drug metabolism, receptor activity, and central responsiveness (12). In areas such as chronic pain and addiction, acupuncture has been shown to reduce dependence on opioids, lower required dosages, and minimize adverse drug reactions (13, 14). Although such evidence is primarily drawn from these fields, similar neuromodulatory effects may be relevant to the treatment of hormonal insomnia.

However, pharmacotherapy alone often encounters issues such as tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, and residual sedation (15). Despite increasing interest in integrated approaches, current clinical evidence for AP in treating PMI remains limited. Systematic reviews have identified significant methodological inconsistencies, including heterogeneity in outcome measures, variability in intervention protocols (e.g., frequency, duration, and acupoint selection), and insufficient long-term follow-up. These limitations hamper the development of standardized clinical guidelines.

This study aims to systematically evaluate the efficacy of AP interventions for PMI by synthesizing data from RCTs. By standardizing outcome measures and comparing the effects of various interventions, this meta-analysis aims to provide an evidence-based foundation for integrative treatment strategies in the management of PMS.

Methods

Study registration

According to the PRISMA 2020 statement (16), we registered the systematic review protocol in PROSPERO on August 20, 2024 (Registration Number: CRD42024579691).1

Search strategies

PubMed, WOS, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, CBM, Wanfang and CQVIP databases were searched, and the search period was set as from the construction of the library to August 1, 2024. The search utilized both MeSH terms and text word. The PubMed search strategy is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | “Acupuncture” [MeSH Terms] |

| #2 | “Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Scalp Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Neck Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Auricular Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Facial Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Tongue Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Hand Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Foot Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Body Acupuncture” [Text Word] “Abdominal Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Back Acupuncture” [Text Word] OR “Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture” [Text Word] |

| #3 | #7 OR #8 |

| #4 | “Perimenopause” [MeSH Terms] |

| #5 | “Perimenopause” [Text Word] OR “Menopause” [Text Word] “Menopausal Transition” [Text Word] |

| #6 | #1 OR #2 |

| #7 | “Insomnia” [MeSH Terms] |

| #8 | “Insomnia” [Text Word] OR “Sleep Disorder” [Text Word] “Bumei” [Text Word] |

| #9 | #4 OR #5 |

| #10 | “Randomized Controlled Trials” [MeSH Terms] |

| #11 | “Randomized Controlled Trials” [Text Word] OR “Randomized Controlled Trial” [Text Word] OR “RCTs” [Text Word] OR “RCT” [Text Word] |

| #12 | #10 OR #11 |

| #13 | #3 AND #6 AND #9 AND #12 |

Search strategy (PubMed).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected based on the pre-defined inclusion criteria: (1) Study design: Only RCTs were considered for inclusion; (2) Participants: Only perimenopausal women who met internationally recognized diagnostic criteria or guidelines for PMI were considered for inclusion, with no restrictions on age, course, ethnicity, country; (3) Interventions: All experimental groups were treated with the AP, while all control groups were treated with Western medication alone (as opposed to the Western medication used in experimental group); (4) Outcome measures: ① Primary outcome measures: Effective rate, HAMA, TCMS; ② Secondary outcome measures: PSQI, KMI, LH, FSH, E2; (5) Language restrictions: Only Chinese or English articles were considered for inclusion.

Study selection

6 researchers (BY, SJ, YT, YW, JZ, CG) were randomly paired into teams of 2 to conduct literature screening using Endnote 20, maintaining independence both between and within groups throughout the screening process. After all groups completed their assessments, inter- and intra-group comparisons were conducted to cross-verify results, identify and reconcile any discrepancies, and ultimately adopt the most comprehensive findings. In case of disagreement, a reviewer (CS) was consulted to reach consensus.

Data extraction

Six researchers (BY, SJ, YT, YW, JZ, CG) were randomly paired into teams of 2 to conduct literature screening using Excel, maintaining independence both between and within groups throughout the extraction process. A data pre-extraction was conducted first. Upon completion by all groups, inter- and intra-group cross-verification was performed to consolidate the final data extraction results. In case of disagreement, a reviewer (CS) was consulted to reach consensus. Data extraction involved identification (first author and publication date), interventions (experiment group and control group), sample size, age, course, acupuncture points, medication dosages, duration, and outcome measures.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias of included studies was assessed using the methods recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (17). The main body consists of 7 items: (1) Random sequence generation (selection bias); (2) Allocation concealment (selection bias); (3) Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); (4) Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); (5) Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); (6) Selective reporting (reporting bias); (7) Others (other bias). Each entry was assessed according to the criteria of “low risk,” “unclear risk,” or “high risk.” 6 researchers (BY, SJ, YT, YW, JZ, CG) were randomly paired into teams of 2 to conduct risk-of-bias assessment using RevMan 5.4, maintaining independence both between and within groups throughout the extraction process. Upon completion by all groups, both inter- and intra-group cross-verifications were performed to minimize potential errors. In case of disagreement, a reviewer (CS) was consulted to reach consensus.

Missing data handling

In cases of missing data, we attempted to contact the original authors for clarification. If unobtainable, the studies were excluded with justification, and sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess potential impacts on the overall findings.

Statistical methods

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 and Stata 15.0, employing risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous variables (count data) and mean differences (MD) for continuous variables (measurement data), both reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 statistics and p-value, with fixed-effect models (I2 ≤ 50%, p > 0.1) or random-effects models (I2 > 50%, p < 0.1), supplemented by sensitivity, subgroup and regression analyses as needed. For outcome measures (included studies number≥10), funnel plots were constructed and Egger test and Begg test were performed to assess potential publication bias.

Evidence quality evaluation

Six researchers (BY, SJ, YT, YW, JZ, CG) were randomly paired into teams of 2 to conduct assessment using the GRADEprofiler, maintaining independence both between and within groups throughout the evaluation process. After all groups completed their assessments, inter- and intra-group comparisons were conducted to cross-verify results, identify and reconcile any discrepancies, and ultimately adopt the most comprehensive findings. In case of disagreement, a reviewer (CS) was consulted to reach consensus. Finally, the evidence levels of all outcome measures were categorized into 4 standards: “high,” “moderate,” “low” and “very low.”

Results

Literature screening process

A total of 943 studies underwent initial screening, and through rigorous selection, 12 Chinese studies (18–29) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis. The literature screening process is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Study flow diagram.

Basic characteristics of the studies

The analysis included 12 studies (18–29) comprising 969 PMI patients, with 489 cases in the experiment group and 480 cases in the control group, all showing similar baseline characteristics. The experiment group received AP, while the control group received Western medication alone, with drug regimens corresponding to their respective experiment group. Regarding diagnostic criteria, 4 studies (19, 20, 25, 29) lacked complete standards, including 2 studies (19, 25) that failed to specify perimenopausal criteria and 2 studies (20, 29) that omitted both perimenopausal and insomnia diagnostic criteria. The remaining 8 studies (18, 21–24, 26–28) applied comprehensive criteria, with 4 studies using CCMD-3 (19, 22, 24, 25) for insomnia diagnosis, 3 studies (19, 21, 22) following TCM Diagnostic & Efficacy Standards, while 5 studies (21–24, 27) utilized Obstetrics and Gynecology for PMI diagnosis. Reported outcome measures included effective rate in 8 studies (18, 20–24, 26, 27), HAMA scores in 4 studies (19, 21, 22, 24), TCMS in 3 studies (21, 23, 28), PSQI in 10 studies (18–25, 27, 29), KMI in 6 studies (19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 28), LH levels in 5 studies (20, 24, 26–28), FSH levels in 6 studies (20, 23, 24, 26–28), and E2 levels in 7 studies (20, 23, 24, 26–29). The baseline characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Tables 2–4.

Table 2

| Study ID | Experimental treatment | Control treatment | Sample size (E/C) | Age [mean ± SD] (E/C) | Course [mean ± SD] (E/C) | Acupuncture points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai 2022 (18) | Acu + Zopiclone | Zopiclone | 51/51 | 49.54 ± 1.82/49.11 ± 1.61 | 2.02 ± 0.81/2.29 ± 0.73 m | BL23, HT7, SP6, Anmian, GV20 |

| Dai 2022 (19) | Acu + Escitalopram Oxalate | Escitalopram Oxalate | 38/35 | 48.68 ± 2.28/48.51 ± 3.32 | 14.34 ± 7.69/13.77 ± 7.24 m | GV20, EX-HN1, GV24, GV29 |

| Li 2019 (20) | Acu + Climen | Climen | 30/30 | 55.54 ± 2.94/54.98 ± 2.76 | 9.71 ± 2.11/9.84 ± 2.43 m | SP6, SP7, SP9 |

| Liu 2023 (21) | Acu + Femoston | Femoston | 39/40 | 49.5 ± 3.0/49.6 ± 2.7 | Not mentioned | Hypothalamus, Endocrine, Subcortical, Pituitary, Ovaries, Internal Reproductive Organs (Uterus), Liver, Kidney, Heart, Spleen Sympathetic Nerves, HT7, Gonadotropin Point, Body–mind Acupoint, Kuaihuo Point |

| Zhang 2024 (22) | Acu + Flupentixol-melitracen | Flupentixol-melitracen | 35/35 | 45.69 ± 4.77/44.78 ± 5.23 | 6.42 ± 3.87/6.26 ± 3.52 m | GV26, PC6, LR3, PC7, LI4, LI11, GB34, GB39, ST36, CV6, SP10 |

| Zhou 2022 (23) | Acu + Estazolam | Estazolam | 35/32 | 50.37 ± 2.47/49.71 ± 2.71 | 7.89 ± 2.91/7.94 ± 2.96 m | HT7, Heart, Kidney, Sympathetic Nervous System, Endocrine, Subcortical |

| Xue 2023 (24) | Acu + Estazolam | Estazolam | 42/41 | 48.35 ± 2.37/47.75 ± 3.10 | 7.34 ± 1.63/8.02 ± 1.46 m | EX-HN1, Anmian, GV20, BL62, LI4, ST40, LR14, LR2, LR3, BL18, KI6, SP6, ST36 |

| Zhu 2016 (25) | Acu + Estazolam | Estazolam | 37/37 | 49.86 ± 3.15/49.27 ± 3.58 | 2.99 ± 4.24/2.97 ± 3.42 y | GV20, GV24, EX-HN1, Anmian, HT7, LR3, KI3, CV12, ST25, SP9 |

| Lv 2017 (26) | Acu + Nilestriol+Medroxyprogesterone Acetate | Nilestriol+Medroxyprogesterone Acetate | 38/38 | 48.6 ± 3.2/47.7 ± 3.1 | 2.3 ± 0.3/2.2 ± 0.2 y | GV20, BL15, BL20, BL23, BL18, BL13, CV4, CV3, HT7, SP6, ST36 |

| Zheng 2023 (27) | Acu + Estazolam+Oryzanol | Estazolam + Oryzanol | 45/44 | 50.38 ± 3.49/50.13 ± 3.26 | 12.06 ± 3.90/12.68 ± 3.74 m | GV29, Anmian, GV20, GV24, EX-HN1, GB13, HT7, KI3, SP6 |

| Li 2022 (28) | Acu + Estradiol Valerate + Progesterone | Estradiol Valerate + Progesterone | 56/56 | 51.53 ± 2.02/52.01 ± 2.11 | 3.28 ± 0.81/3.36 ± 0.78 y | ST25, SP6, EX-CA1, CV4 |

| Han 2020 (29) | Acu + Agomelatine | Agomelatine | 43/41 | Not Mentioned | Not Mentioned | ST36, CV12, SP6, LR3, PC6 |

Basic characteristics of studies.

Acu, Acupuncture; E, Experimental group; C, Control group; w, week(s); m, month(s); y, year(s).

Table 3

| Study ID | Medication dosages (per dose) | Duration | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bai 2022 (18) | 3 mg | 3 months | Effective rate, PSQI |

| Dai 2022 (19) | 5-20 mg | 4 weeks | PSQI, HAMA, KMI |

| Li 2019 (20) | 2 mg/1 mg + 2 mg | 1 month | Effective rate, PSQI, LH, FSH, E2 |

| Liu 2023 (21) | 1 mg/1 mg + 10 mg | 12 weeks | Effective rate, PSQI, HAMA, KMI, TCMS |

| Zhang 2024 (22) | 0.5 mg + 10 mg | 8 weeks | Effective rate, PSQI, HAMA |

| Zhou 2022 (23) | 1 mg | 4 weeks | Effective rate, PSQI, KMI, TCMS, FSH, E2 |

| Xue 2023 (24) | 2 mg | 4 weeks | Effective rate, PSQI, HAMA, KMI, LH, FSH, E2 |

| Zhu 2016 (25) | 1 mg | 4 weeks | PSQI |

| Lv 2017 (26) | 1 mg + 2 mg | 4 weeks | Effective rate, KMI, LH, FSH, E2 |

| Zheng 2023 (27) | 1 mg + 10 mg | 4 weeks | Effective rate, PSQI, LH, FSH, E2 |

| Li 2022 (28) | 1 mg + 100 mg | 8 weeks | KMI, TCMS, LH, FSH, E2 |

| Han 2020 (29) | 25 mg | 4 weeks | PSQI, E2 |

Information supplement.

Table 4

| Study ID | Diagnostic criteria (perimenopause) | Diagnostic criteria (insomnia) |

|---|---|---|

| Bai 2022 (18) |

International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Traditional Chinese Medicine: Menopausal Syndrome (2020)

Clinical Application Guidelines of Chinese Patent Medicines for Treating Menopausal Syndrome (2020) |

Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Insomnia (2017)

International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Traditional Chinese Medicine: Menopausal Syndrome (2020) Clinical Application Guidelines of Chinese Patent Medicines for Treating Menopausal Syndrome (2020) |

| Dai 2022 (19) | Not Mentioned |

CCMD-3 (2001)

TCM Diagnostic & Efficacy Standards (2017) |

| Li 2019 (20) | Not Mentioned | Not Mentioned |

| Liu 2023 (21) | Clinical Guidelines for Obstetrics and Gynecology (2009) |

Clinical Guidelines for Obstetrics and Gynecology (2009)

ICSD-3 (2014) TCM Diagnostic & Efficacy Standards (1994) |

| Zhang 2024 (22) | Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018) |

Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018)

CCMD-3 (2001) TCM Diagnostic & Efficacy Standards (2017) |

| Zhou 2022 (23) |

Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018)

DSM-5 (2018) |

Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018)

DSM-5 (2018) Guidance principle of clinical study on new drug of traditional Chinese medicine (2002) |

| Xue 2023 (24) | Obstetrics and Gynecology-6 (2004) |

Obstetrics and Gynecology-6 (2004)

CCMD-3 (2001) Gynecology of Traditional Chinese Medicine-2 (2006) |

| Zhu 2016 (25) | Not Mentioned |

Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment Programs for 22 Professional and 95 Kinds of Diseases in Chinese Medicine Symptoms (2010)

Practical Neurology of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine-2 (2011) CCMD-3 (2001) |

| Lv 2017 (26) | Diagnostic Criteria for Gynecological Diseases (2001) | Diagnostic Criteria for Gynecological Diseases (2001) |

| Zheng 2023 (27) | Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018) |

Obstetrics and Gynecology-9 (2018)

Zhou Zhongying’s Practical Internal Medicine of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2012) |

| Li 2022 (28) | Perimenopausal Syndrome (2011) | Perimenopausal Syndrome (2011) |

| Han 2020 (29) | Not Mentioned | Not Mentioned |

Information supplement.

CCMD-3, Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders-3; ICSD-3, International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5.

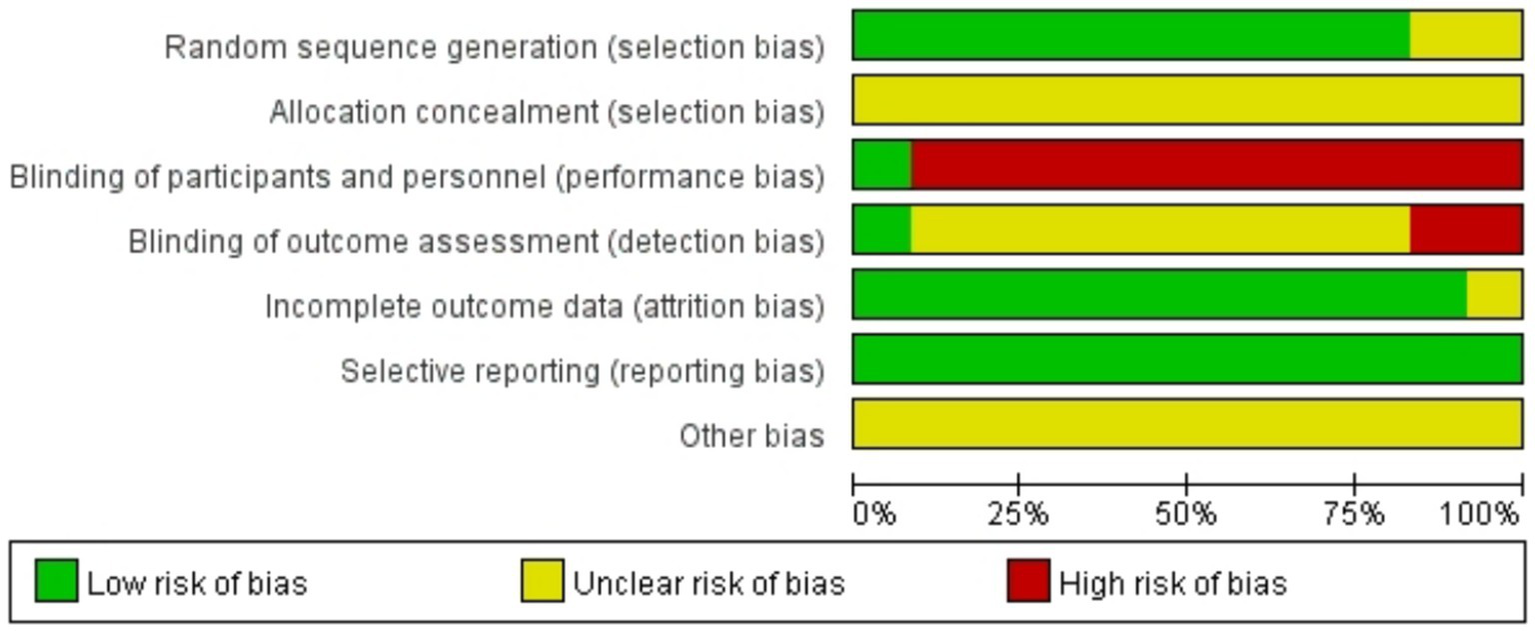

Risk of bias assessment

Among the 12 studies (18–29) included in the analysis, 8 studies (18, 19, 22–27) utilized random number tables for allocation, 2 studies (21, 29) mentioned randomization without specifying methods, and 2 studies (20, 28) employed treatment-based grouping. No studies reported allocation concealment, substantially increasing potential bias risks. Due to the inherent nature of acupuncture interventions, genuine blinding was unattainable. Only 1 study (24) documented blinding of participants and personnel and outcome assessment. Additionally, 1 study had partial missing data that did not significantly affect the analytical outcomes. Detailed results are presented in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 2

Risk of bias graph.

Figure 3

Risk of bias summary.

Primary outcome measures

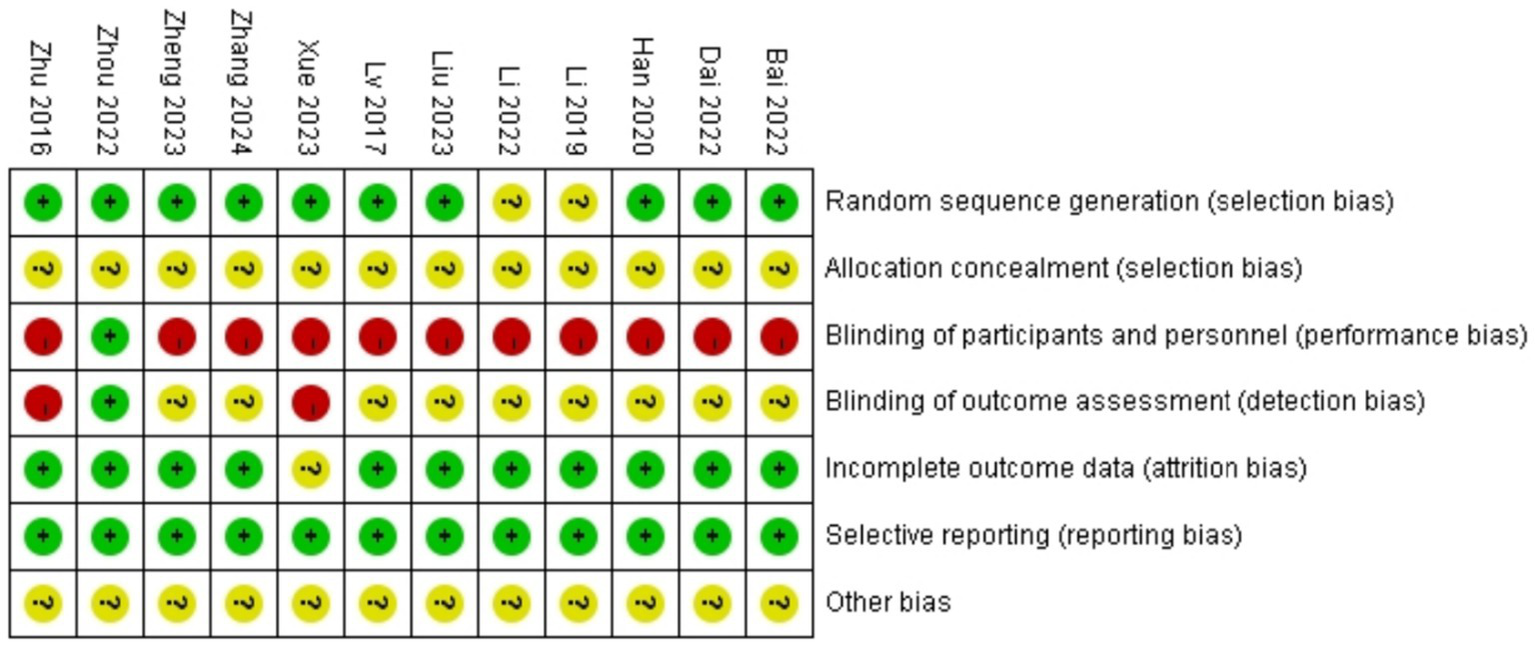

Effective rate

A total of 626 patients in 8 studies (18, 20–24, 26, 27) reported the clinical effective rate of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data revealed a moderate level of heterogeneity (p = 0.003 < 0.1; I2 = 67%), so a random-effects model was applied [RR = 1.28, 95% CI (1.13, 1.45), Z = 3.88, p = 0.0001 < 0.05]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, it was found that when the study Liu et al. (21) was excluded, the heterogeneity significantly decreased (p = 0.67 > 0.1; I2 = 0%), suggesting that this study may be the source of the heterogeneity. Consequently, a fixed-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP effectively improved insomnia symptoms in perimenopausal women, with statistically significant results [RR = 1.22, 95% CI (1.13, 1.30), Z = 3.88, p < 0.00001], as detailed in Table 5 and Figure 4.

Table 5

| Exclusion | MD [95%CI] | p | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu 2023 (21) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.30] | 0.67 | 0% |

| Bai 2022 (18) | 1.32 [1.15, 1.52] | 0.009 | 65% |

| Li 2019 (20) | 1.26 [1.10, 1.44] | 0.003 | 69% |

| Xue 2023 (24) | 1.31 [1.13, 1.52] | 0.001 | 72% |

| Lv 2017 (26) | 1.30 [1.12, 1.51] | 0.001 | 73% |

| Zhang 2024 (22) | 1.29 [1.12, 1.49] | 0.001 | 73% |

| Zheng 2023 (27) | 1.30 [1.12, 1.51] | 0.001 | 73% |

| Zhou 2022 (23) | 1.30 [1.13, 1.50] | 0.001 | 73% |

Sensitivity analysis report of effective rate.

Figure 4

Forest plot effective rate.

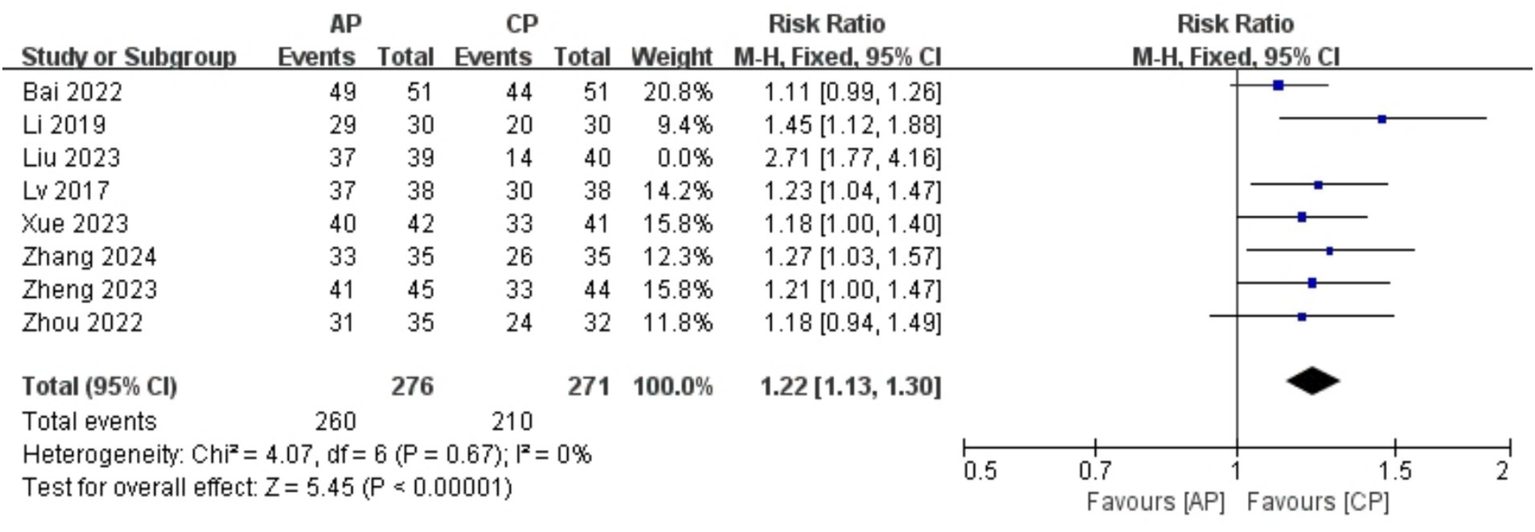

HAMA

A total of 305 patients in 4 studies (19, 21, 22, 24) reported the HAMA scores of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 92%), so a random-effects model was applied [MD = -3.42, 95% CI (−5.03, −1.81), Z = 4.16, p < 0.00001]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, it was found that when the study Liu et al. (21) and study Zhang et al. (22) were excluded, the heterogeneity significantly decreased (p = 0.32 > 0.1; I2 = 0%), suggesting that these 2 studies might be the sources of heterogeneity. Consequently, a fixed-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in HAMA scores among perimenopausal women [MD = -3.26, 95% CI (−3.79, −2.73), Z = 12.06, p < 0.00001], as detailed in Table 6 and Figure 5.

Table 6

| Exclusion | MD [95%CI] | p | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu 2023 (21) | −2.61 [−3.78, −1.44] | 0.005 | 81% |

| Zhang 2024 (22) | −4.07 [−5.73, −2.40] | <0.0001 | 90% |

| Xue 2023 (24) | −3.42 [−6.03, −0.82] | <0.00001 | 94% |

| Dai 2022 (19) | −3.62 [−5.84, −1.40] | <0.00001 | 94% |

| Liu 2023 (21) and Zhang 2024 (22) | −3.26 [−3.79, −2.73] | 0.32 | 0% |

| Liu 2023 (21) and Xue 2023 (24) | −2.13 [−3.52, −0.74] | 0.06 | 72% |

| Dai 2022 (19) and Liu 2023 (21) | −2.47 [−4.44, −0.49] | 0.001 | 90% |

| Dai 2022 (19) and Zhang 2024 (22) | −4.70 [−7.26, −2.13] | <0.0001 | 94% |

| Xue 2023 (24) and Zhang 2024 (22) | −4.43 [−7.59, −1.27] | <0.0001 | 94% |

| Dai 2022 (19) and Xue 2023 (24) | −3.73 [−8.27, −0.82] | <0.00001 | 97% |

Sensitivity analysis report of HAMA.

Figure 5

Forest plot of HAMA.

TCMS

A total of 258 patients in 3 studies (21, 23, 28) reported the TCMS scores of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p = 0.004 < 0.1; I2 = 82%), so a random-effects model was applied [MD = −2.22, 95% CI (−4.19, −0.26), Z = 2.22, p = 0.03 < 0.05]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, it was found that when the study Liu et al. (21) was excluded, the heterogeneity significantly decreased (p = 0.45 > 0.1; I2 = 0%), suggesting that this study might be the source of the heterogeneity. Consequently, a fixed-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in TCMS scores among perimenopausal women [MD = −0.98, 95% CI (−1.21, −0.74), Z = 7.99, p < 0.00001], as detailed in Table 7 and Figure 6.

Table 7

| Exclusion | MD [95%CI] | p | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu 2023 (21) | −0.98 [−1.21, −0.74] | 0.45 | 0% |

| Li 2022 (28) | −4.07 [−9.59, 1.45] | 0.006 | 87% |

| Zhou 2022 (23) | −3.77 [−9.84, 2.30] | 0.001 | 90% |

Sensitivity analysis report of TCMS.

Figure 6

![Forest plot comparing studies by Li 2022, Liu 2023, and Zhou 2022 on AP versus CP. It shows mean differences with a fixed-effect model. The overall mean difference is \(-0.98\) with a \(95\%\) confidence interval of \([-1.21, -0.74]\). Heterogeneity is low, with \(I^2 = 0\%\) and \(P = 0.45\). The test for overall effect is significant, \(Z = 7.99\), \(P < 0.00001\).](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1633794/xml-images/fneur-16-1633794-g006.webp)

Forest plot of TCMS.

Secondary outcome measures

PSQI

A total of 781 patients in 10 studies (18–25, 27, 29) reported the PSQI of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 97%), so a random-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in PSQI among perimenopausal women [MD = −3.12, 95% CI (−4.21, −2.03), Z = 5.63, p < 0.00001]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity was observed, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Subsequently, subgroup and regression analysis were then performed. The data were categorized into 4 subgroups according to sample size, age, course, and duration, yet the heterogeneity did not significantly decrease. Regression analysis results suggest that although AP may be more effective overall than Western medication alone, an increase in sample size might weaken this effect, with this impact being statistically near significance (p = 0.056). The effect sizes for age (p = 0.795), course (p = 0.466) and duration (p = 0.936) were not statistically significant. Regardless of age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years) or duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks), there was little difference in efficacy across subgroups for AP, as detailed in Figure 7 and Table 8.

Figure 7

![Forest plot comparing studies on AP vs. CP, showing mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. The chart indicates a total mean difference of -3.12 [95% CI: -4.21, -2.03], favoring CP. Heterogeneity is high with I² at 97%.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1633794/xml-images/fneur-16-1633794-g007.webp)

Forest plot of PSQI.

Table 8

| Covariates | _ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

| Sample size | −2.590169 | 1.160147 | −2.23 | 0.056 | −5.265473, 0.0851348 |

| _cons (Sample size) | 1.388907 | 1.711638 | 0.81 | 0.441 | −2.558137, 5.335952 |

| Age | 0.5340293 | 1.976585 | 0.27 | 0.795 | −4.139852, 5.207911 |

| _cons (Age) | −2.958072 | 2.554498 | −1.16 | 0.285 | −8.998499, 3.082355 |

| Course | 0.9934527 | 1.276245 | 0.78 | 0.466 | −2.129406, 4.116311 |

| _cons (Course) | −3.828757 | 2.121897 | −1.80 | 0.121 | −9.020852, 1.363338 |

| Duration | 0.075688 | 0.9084093 | 0.08 | 0.936 | −2.019108, 2.170484 |

| _cons (Duration) | −2.359632 | 1.550303 | −1.52 | 0.166 | −5.934637, 1.215374 |

Regression analysis results of PSQI.

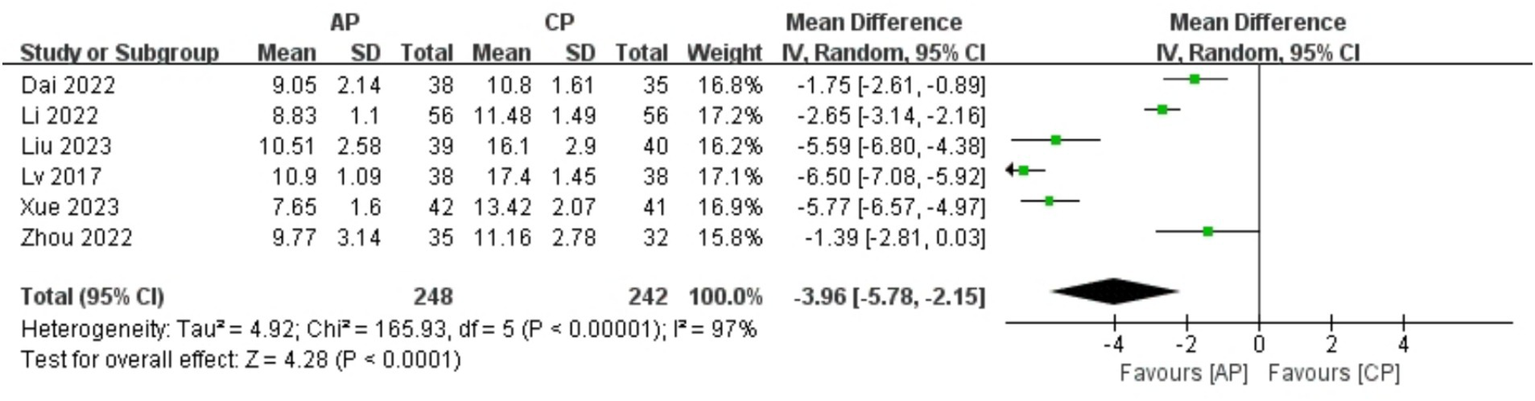

KMI

A total of 490 patients in 6 studies (19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 28) reported the KMI of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 97%), so a random-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in KMI among perimenopausal women [MD = −3.96, 95% CI (−5.78, −2.15), Z = 4.28, p < 0.0001]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity was observed, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Subsequently, subgroup and regression analysis were then performed. The data were categorized into 4 subgroups according to sample size, age, course, and duration, yet the heterogeneity did not significantly decrease. Regression analysis results showed that the effect sizes for sample size (p = 0.774), age (p = 0.899), course (p = 0.589) and duration (p = 0.858) were not statistically significant. Regardless of sample size (<40, >40), age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years) or duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks), there was little difference in efficacy between subgroups for AP, as detailed in Figure 8 and Table 9.

Figure 8

Forest plot of KMI.

Table 9

| Covariates | _ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

| Sample size | −0.4833773 | 1.570389 | −0.31 | 0.774 | −4.84347,7 3.876723 |

| _cons (Sample size) | −1.602275 | 2.223611 | −0.72 | 0.511 | −7.776009, 4.571458 |

| Age | 0.2703314 | 1.99776 | 0.14 | 0.899 | −5.27634, 5.817002 |

| _cons (Age) | −2.564183 | 2.452069 | −1.05 | 0.355 | −9.372218, 4.243853 |

| Course | −0.4620522 | 0.7665194 | −0.60 | 0.589 | −2.901459, 1.977354 |

| _cons (Course) | −1.280723 | 1.907573 | −0.67 | 0.550 | −7.351472, 4.790025 |

| Duration | 0.1867735 | 0.9759528 | 0.19 | 0.858 | −2.522906, 2.896453 |

| _cons (Duration) | −2.529015 | 1.646977 | −1.54 | 0.199 | −7.101756, 2.043726 |

Regression analysis results of KMI.

LH

A total of 420 patients in 5 studies (20, 24, 26–28) reported the LH levels of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 97%), so a random-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in LH levels among perimenopausal women [MD = −10.16, 95% CI (−16.41, −3.91), Z = 3.18, p = 0.001 < 0.05]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity was observed, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Subsequently, subgroup and regression analysis were then performed. The data were categorized into 4 subgroups according to sample size, age, course, and duration, yet the heterogeneity did not significantly decrease. Regression analysis results showed that the effect sizes for sample size (p = 0.558), age (p = 0.225), course (p = 0.390) and duration (p = 0.631) were not statistically significant. Regardless of sample size (<40, >40), age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years) or duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks), there was little difference in efficacy between subgroups for AP, as detailed in Figure 9 and Table 10.

Figure 9

![Forest plot comparing AP and CP groups across five studies. Each study lists mean, standard deviation (SD), total participants, and weight. The mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown with green squares and lines. Overall mean difference is -10.16 with a 95% CI of [-16.41, -3.91], indicated by a black diamond. Heterogeneity and effect statistics are provided.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1633794/xml-images/fneur-16-1633794-g009.webp)

Forest plot of LH.

Table 10

| Covariates | _ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

| Sample size | 0.6268005 | 0.9527609 | 0.66 | 0.558 | −2.40531, 3.658911 |

| _cons (Sample size) | −2.172339 | 1.602291 | −1.36 | 0.268 | −7.271544, 2.926865 |

| Age | −1.14655 | 0.7530293 | −1.52 | 0.225 | −3.543026, 1.249925 |

| _cons (Age) | 0.6749386 | 1.254691 | 0.54 | 0.628 | −3.318049, 4.667926 |

| Course | 0.368096 | 0.3670972 | 1.00 | 0.390 | −0.800171, 1.536363 |

| _cons (Course) | −1.978721 | 0.9226806 | −2.14 | 0.121 | −4.915102, 0.9576608 |

| Duration | 0.6283968 | 1.177636 | 0.53 | 0.631 | −3.119368, 4.376161 |

| _cons (Duration) | −1.921858 | 1.496743 | −1.28 | 0.289 | −6.685162, 2.841446 |

Regression analysis results of LH.

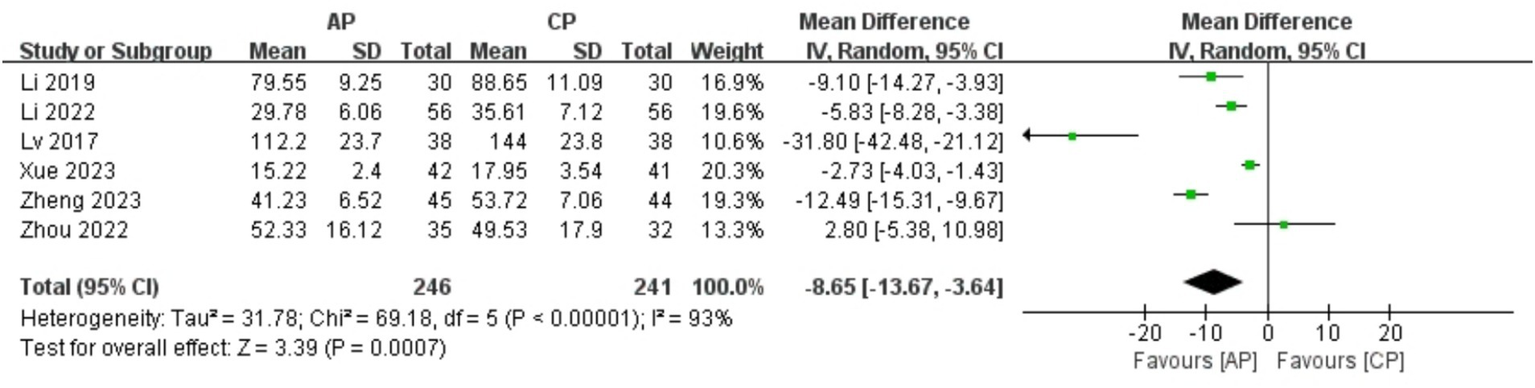

FSH

A total of 487 patients in 6 studies (20, 23, 24, 26–28) reported the FSH levels of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 93%), so a random-effects model was applied. Compared with control group, AP showed a statistically significant improvement in FSH levels among perimenopausal women [MD = −8.65, 95% CI (−13.67, −3.64), Z = 3.39, p = 0.0007 < 0.05]. Using a stepwise exclusion method, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity was observed, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Subsequently, subgroup and regression analysis were then performed. The data were categorized into 4 subgroups according to sample size, age, course, and duration, yet the heterogeneity did not significantly decrease. Regression analysis results showed that the effect sizes for sample size (p = 0.398), age (p = 0.405), course (p = 0.502) and duration (p = 0.927) were not statistically significant. Regardless of sample size (<40, >40), age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years) or duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks), there was little difference in efficacy across subgroups for AP, as detailed in Figure 10 and Table 11.

Figure 10

Forest plot of FSH.

Table 11

| Covariates | _ES_ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

| Sample size | −0.515591 | 0.5448897 | −0.95 | 0.398 | −2.028447, 0.9972653 |

| _cons (Sample size) | −0.1685247 | 0.8656081 | −0.19 | 0.855 | −2.571838, 2.234789 |

| Age | −0.5079103 | 0.5466213 | −0.93 | 0.405 | −2.025574, 1.009754 |

| _cons (Age) | −0.1839147 | 0.8644944 | −0.21 | 0.842 | −2.584136, 2.216306 |

| Course | −0.1791234 | 0.2431741 | −0.74 | 0.502 | −0.8542829, 0.496036 |

| _cons (Course) | −0.585141 | 0.5660585 | −1.03 | 0.360 | −2.156771, 0.9864893 |

| Duration | 0.0781208 | 0.7973545 | 0.10 | 0.927 | −2.13569, 2.291932 |

| _cons (Duration) | −1.038068 | 0.9826441 | −1.06 | 0.350 | −3.766325, 1.690189 |

Regression analysis results of FSH.

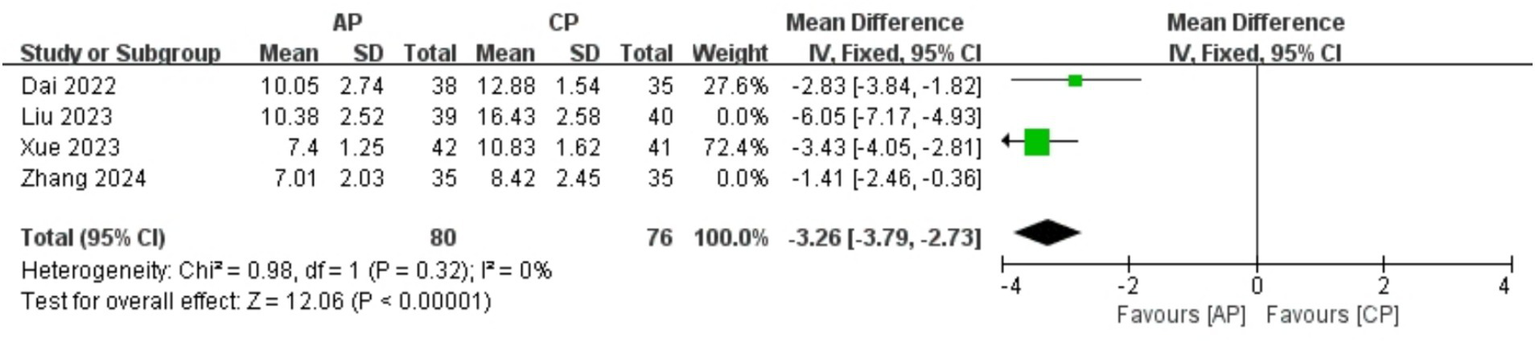

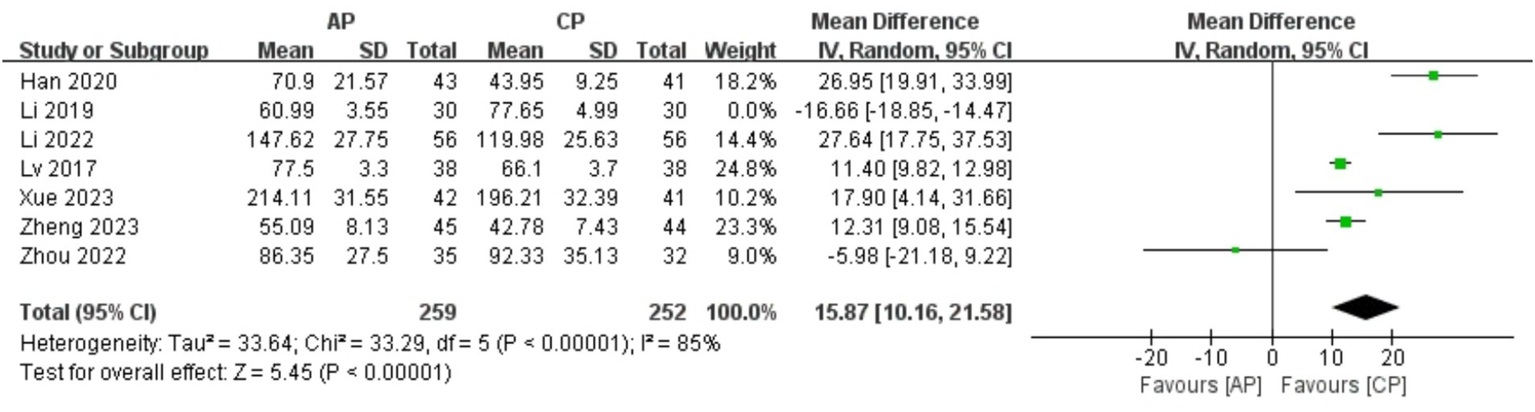

E2

A total of 571 patients in 7 studies (20, 23, 24, 26–29) reported the E2 levels of AP in PMI. Analysis of the extracted data indicated high heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 99%), so a random-effects model was applied. The results showed no significant statistical difference [MD = 10.47, 95% CI (−2.61, 23.56), Z = 1.57, p = 0.12 > 0.05]. Further investigation revealed that the study Li et al. (20) had a significant impact on the statistical outcome. After excluding this study, the analysis demonstrated statistically significant results (Z = 5.45, p < 0.00001) along with a reduction in heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 85%), compared with control group, AP significantly improved E2 levels in perimenopausal women [MD = 15.87, 95% CI (10.16, 21.58), Z = 5.45, p < 0.00001]. Using a stepwise exclusion method to the remaining studies did not substantially reduce heterogeneity, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Subgroup and regression analysis were then performed. The data were categorized into 4 subgroups according to sample size, age, course, and duration, yet the heterogeneity did not significantly decrease. Regression analysis results showed that the effect sizes for sample size (p = 0.800), age (p = 0.935), course (p = 0.343) and duration (p = 0.835) were not statistically significant. Regardless of sample size (<40, >40), age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years) or duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks), there was little difference in efficacy across subgroups for AP, as detailed in Figure 11 and Table 12.

Figure 11

Forest plot of E2.

Table 12

| Covariates | _ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

| Sample size | −0.3025809 | 1.115643 | −0.27 | 0.800 | −3.400103, 2.794941 |

| _cons (Sample size) | 1.799774 | 1.937356 | 0.93 | 0.405 | −3.579188, 7.178736 |

| Age | 0.1198141 | 1.352561 | 0.09 | 0.935 | −4.184639, 4.424267 |

| _cons (Age) | 1.066501 | 2.010372 | 0.53 | 0.633 | −5.331399, 7.464401 |

| Course | 0.533321 | 0.4746068 | 1.12 | 0.343 | −0.9770897, 2.043732 |

| _cons (Course) | 0.0579837 | 1.181358 | 0.05 | 0.964 | −3.701624, 3.817592 |

| Duration | −0.312064 | 1.401123 | −0.22 | 0.835 | −4.202205, 3.578078 |

| _cons (Duration) | 1.658906 | 1.7205 | 0.96 | 0.390 | −3.117968, 6.43578 |

Regression analysis results of E2.

Subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis and regression analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed based on 4 aspects: sample size (<40, >40), age (<50 years, >50 years), course (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years), and duration (4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks). See Supplementary material for figures and Tables 13, 14 for details. The analysis revealed that none of the subgroups effectively reduced heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses showed stable levels, and a stepwise exclusion method was used to identify the sources of heterogeneity. For outcome measures where heterogeneity remained high, regression analysis was performed on each subgroup, as detailed in Tables 8–12 and Supplementary material.

Table 13

| Outcomes | Parameter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Participants | p | I2 | Effect estimate | Effect model | |||

| PSQI | Sample size | <40 | 6 | 423 | <0.00001 | 87% | −2.66 [−3.83, −1.48] | Random |

| >40 | 4 | 358 | <0.0001 | 98% | −3.77 [−5.46, −2.08] | Random | ||

| Age | <50 | 7 | 548 | <0.0001 | 98% | −3.19 [−4.68, −1.70] | Random | |

| >50 | 2 | 149 | 0.004 | 90% | −2.95 [−4.96, −0.95] | Random | ||

| Course | <1 years | 5 | 382 | 0.002 | 98% | −2.92 [−4.79, −1.06] | Random | |

| 1–2 years | 2 | 162 | <0.00001 | 34% | −3.69 [−4.27, −3.10] | Random | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | 74 | 0.20 | N/A | −0.95 [−2.39, 0.49] | N/A | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 7 | 530 | <0.00001 | 96% | −3.14 [−4.40, −1.88] | Random | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | 70 | <0.0001 | N/A | −1.59 [−2.31, −0.87] | N/A | ||

| 12 weeks | 2 | 181 | 0.004 | 95% | −3.85 [−6.47, −1.22] | Random | ||

| KMI | Sample size | <40 | 4 | 295 | 0.007 | 97% | −3.83 [−6.61, −1.06] | Random |

| >40 | 2 | 195 | 0.007 | 98% | −4.19 [−7.25, −1.14] | Random | ||

| Age | <50 | 5 | 378 | <0.0001 | 96% | −4.23 [−6.31, −2.15] | Random | |

| >50 | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | −2.65 [−3.14, −2.16] | N/A | ||

| Course | <1 years | 2 | 150 | 0.10 | 96% | −3.62 [−7.91, 0.67] | Random | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 73 | <0.0001 | N/A | −1.75 [−2.61, −0.89] | N/A | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | 76 | <0.00001 | N/A | −6.50 [−7.08, −5.92] | N/A | ||

| >3 years | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | −2.65 [−3.14, −2.16] | N/A | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 4 | 299 | 0.002 | 97% | −3.90 [−6.42, −1.37] | Random | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | −2.65 [−3.14, −2.16] | N/A | ||

| 12 weeks | 1 | 79 | <0.00001 | N/A | −5.59 [−6.80, −4.38] | N/A | ||

| LH | Sample size | <40 | 2 | 136 | 0.18 | 98% | −20.20 [−49.52, 9.13] | Random |

| >40 | 3 | 284 | 0.04 | 94% | −4.64 [−8.98, −0.31] | Random | ||

| Age | <50 | 2 | 159 | 0.16 | 50% | −2.46 [−5.88, 0.96] | Random | |

| >50 | 3 | 261 | 0.006 | 97% | −15.33 [−26.17, −4.50] | Random | ||

| Course | <1 years | 2 | 143 | 0.28 | 99% | −18.15 [−51.30, 15.01] | Random | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 89 | <0.00001 | N/A | −8.79 [−11.07, −6.51] | N/A | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | 76 | 0.05 | N/A | −5.30 [−10.59, −0.01] | N/A | ||

| >3 years | 1 | 112 | 0.0004 | N/A | −3.98 [−6.20, −1.76] | N/A | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 4 | 308 | 0.008 | 98% | −12.13 [−21.10, −3.16] | Random | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | 112 | 0.0004 | N/A | −3.98 [−6.20, −1.76] | N/A | ||

| FSH | Sample size | <40 | 3 | 203 | 0.13 | 92% | −12.27 [−28.30, 3.77] | Random |

| >40 | 3 | 284 | 0.01 | 95% | −6.91 [−12.36, −1.45] | Random | ||

| Age | <50 | 3 | 226 | 0.20 | 93% | −9.85 [−24.76, 5.07] | Random | |

| >50 | 3 | 261 | 0.0001 | 84% | −9.10 [−13.77, −4.44] | Random | ||

| Course | <1 years | 3 | 210 | 0.17 | 73% | −3.58 [−8.73, 1.56] | Random | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 89 | <0.00001 | N/A | −12.49 [−15.31, −9.67] | N/A | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | 76 | <0.00001 | N/A | −31.80 [−42.48, −21.12] | N/A | ||

| >3 years | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | −5.83 [−8.28, −3.38] | N/A | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 5 | 375 | 0.007 | 94% | −9.73 [−16.78, −2.67] | Random | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | −5.83 [−8.28, −3.38] | N/A | ||

| E2 | Sample size | <40 | 3 | 203 | 0.75 | 100% | −3.63 [−26.33, 19.06] | Random |

| >40 | 4 | 368 | <0.0001 | 85% | 20.93 [11.37, 30.49] | Random | ||

| Age | <50 | 3 | 226 | 0.08 | 66% | 8.98 [−1.19, 19.15] | Random | |

| >50 | 3 | 261 | 0.55 | 99% | 7.42 [−16.98, 31.81] | Random | ||

| Course | <1 years | 3 | 210 | 0.84 | 92% | −2.25 [−23.73, 19.22] | Random | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 89 | <0.00001 | N/A | 12.31 [9.08, 15.54] | N/A | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | 76 | <0.00001 | N/A | 11.40 [9.82, 12.98] | N/A | ||

| >3 years | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | 27.64 [17.75, 37.53] | N/A | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 6 | 459 | 0.28 | 99% | 7.67 [−6.38, 21.72] | Random | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | 112 | <0.00001 | N/A | 27.64 [17.75, 37.53] | N/A | ||

Subgroup analysis results.

Table 14

| Outcomes | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | ID | |||

| PSQI | Sample size | <40 | 6 | Dai 2022 (19), Li 2019 (20), Liu 2023 (21), Zhang 2024 (22), Zhou 2022 (23), and Zhu 2016 (25) |

| >40 | 4 | Bai 2022 (18), Xue 2023 (24), Zheng 2023 (27), and Han 2020 (29) | ||

| Age | <50 | 7 | Bai 2022 (18), Dai 2022 (19), Liu 2023 (21), Zhang 2024 (22), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), and Zhu 2016 (25) | |

| >50 | 2 | Li 2019 (20) and Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| Course | <1 years | 5 | Bai 2022 (18), Li 2019 (20), Zhang 2024 (22), Zhou 2022 (23), and Xue 2023 (24) | |

| 1–2 years | 2 | Dai 2022 (19) and Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | Zhu 2016 (25) | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 7 | Dai 2022 (19), Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), Zhu 2016 (25), Zheng 2023 (27), and Han 2020 (29) | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | Zhang 2024 (22) | ||

| 12 weeks | 2 | Bai 2022 (18) and Liu 2023 (21) | ||

| KMI | Sample size | <40 | 4 | Dai 2022 (19), Liu 2023 (21), Zhou 2022 (23), and Lv 2017 (26) |

| >40 | 2 | Xue 2023 (24) and Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Age | <50 | 5 | Dai 2022 (19), Liu 2023 (21), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), and Lv 2017 (26) | |

| >50 | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Course | <1 years | 2 | Zhou 2022 (23) and Xue 2023 (24) | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | Dai 2022 (19) | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | Lv 2017 (26) | ||

| >3 years | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 4 | Dai 2022 (19), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), and Lv 2017 (26) | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| 12 weeks | 1 | Liu 2023 (21) | ||

| LH | Sample size | <40 | 2 | Li 2019 (20) and Lv 2017 (26) |

| >40 | 3 | Li 2022 (28), Xue 2023 (24), and Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| Age | <50 | 2 | Xue 2023 (24) and Lv 2017 (26) | |

| >50 | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zheng 2023 (27), and Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Course | <1 years | 2 | Li 2019 (20) and Xue 2023 (24) | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | Lv 2017 (26) | ||

| >3 years | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 4 | Li 2019 (20), Xue 2023 (24), Lv 2017 (26), and Zheng 2023 (27) | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| FSH | Sample size | <40 | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), and Lv 2017 (26) |

| >40 | 3 | Xue 2023 (24), Zheng 2023 (27), and Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Age | <50 | 3 | Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), and Lv 2017 (26) | |

| >50 | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zheng 2023 (27), and Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Course | <1 years | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), and Xue 2023 (24) | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| 2–3 years | 1 | Lv 2017 (26) | ||

| >3 years | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 5 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), Lv 2017 (26), and Zheng 2023 (27) | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| E2 | Sample size | <40 | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), and Lv 2017 (26) |

| >40 | 4 | Xue 2023 (24), Zheng 2023 (27), Li 2022 (28), and Han 2020 (29) | ||

| Age | <50 | 3 | Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), and Lv 2017 (26) | |

| >50 | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zheng 2023 (27), and Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Course | <1 years | 3 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), and Xue 2023 (24) | |

| 1–2 years | 1 | Zheng 2023 (27) | ||

| 2−3 years | 1 | Lv 2017 (26) | ||

| >3 years | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

| Duration | 4 weeks | 6 | Li 2019 (20), Zhou 2022 (23), Xue 2023 (24), Lv 2017 (26), Zheng 2023 (27), and Han 2020 (29) | |

| 8 weeks | 1 | Li 2022 (28) | ||

Consistency component classification.

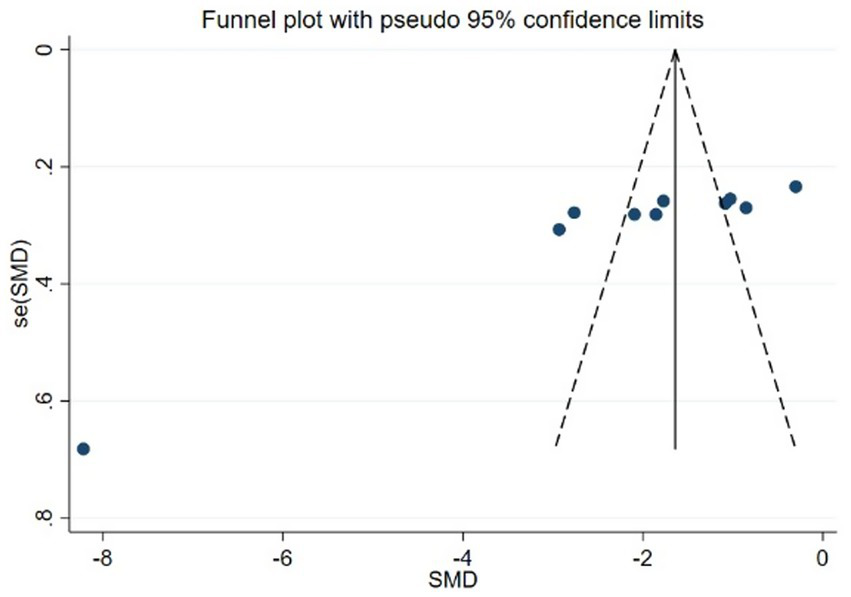

Publication bias

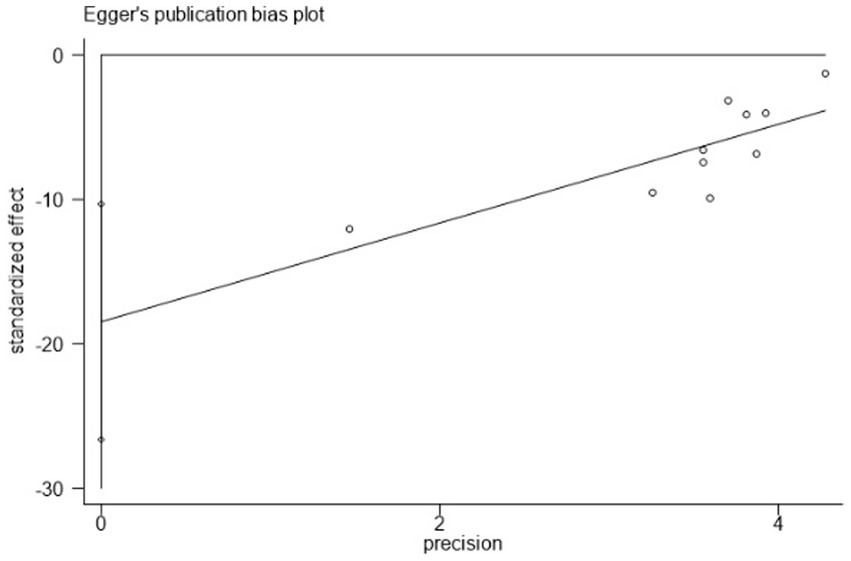

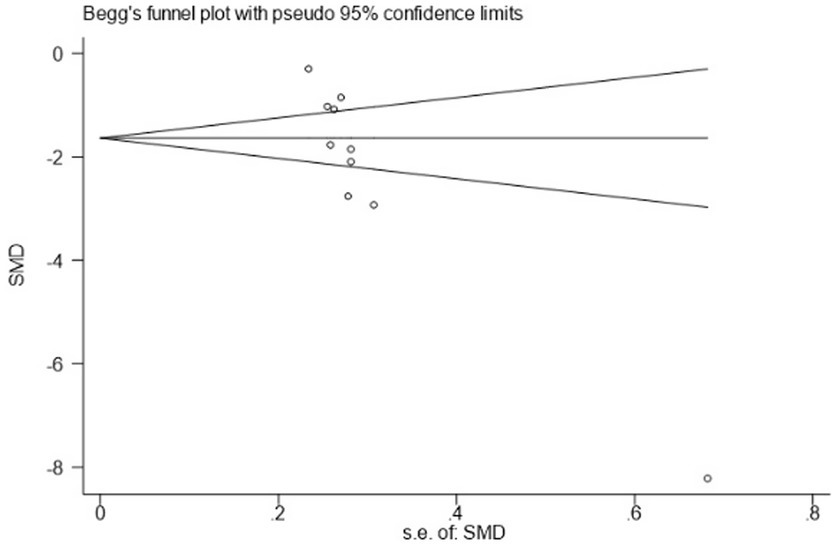

Using PSQI (included studies number = 10) as an indicator to draw a funnel plot of reporting bias, the results show that the scatter points are relatively evenly distributed on both sides, but an extreme point is present on the left side, indicating a relatively large standard error, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. The Egger’s test indicates a significantly upward slope, with a slope coefficient of 3.42 (p = 0.009) and a bias coefficient of −18.48 (p = 0.001). The significant p-values suggest a clear presence of publication bias. The Begg’s test further reveals asymmetry in the funnel plot, particularly with several points deviating significantly at the lower end. Kendall’s Score is −31, z-value is −2.77, and p = 0.006, further supporting the hypothesis of publication bias, as detailed in Figures 12–14 and Tables 15, 16.

Figure 12

Funnel plot of PSQI.

Figure 13

Egger’s test.

Figure 14

Begg’s test.

Table 15

| Std_Eff | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > |t| | [95%Conf. Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | 3.42073 | 0.9891879 | 3.46 | 0.009 | 1.139659, 5.701802 |

| bias | −18.48051 | 3.536957 | −5.22 | 0.001 | −26.63674, −10.32427 |

Results of Egger’s test.

Table 16

| Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|

| adj. Kendall’s score (P-Q) | −31 |

| Std. Dev. of Score | 11.18 |

| Number of studies | 10 |

| z | −2.77 |

| Pr > ∣z∣ | 0.006 |

| z | 2.68 (continuity corrected) |

| Pr > ∣z∣ | 0.007 (continuity corrected) |

Results of Begg’s test.

Grading the quality of evidence

The evidence level assessment indicates that the overall quality of evidence is generally low to very low across all evaluated outcomes (Table 17). This judgment primarily reflects significant methodological limitations present in the included studies. Specifically, the assessment identified serious concerns regarding risk of bias, particularly due to inadequate allocation concealment and insufficient blinding procedures. Furthermore, the certainty of evidence was further diminished by issues of imprecision affecting certain effect estimates.

Table 17

| Profile | Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective rate | HAMA | TCMS | PSQI | KMI | LH | FSH | E2 | |

| Design | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Studies | 8 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Patients (E/C) | 315/311 | 154/151 | 130/128 | 395/386 | 248/242 | 211/209 | 246/241 | 289/282 |

| Risk of bias | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Inconsistency | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Indirectness | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Imprecision | No | No | No | Serious | No | Serious | Serious | Very serious |

| Publication bias | Strongly suspected | Strongly suspected | Strongly suspected | Undetected | Strongly suspected | Strongly suspected | Strongly suspected | Strongly suspected |

| Other considerations | Reporting bias | Reporting bias | Reporting bias | None | Reporting bias | Reporting bias | Reporting bias | Reporting bias |

| Relative effect | RR 1.31 (1.21 to 1.41) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Absolute effect | 223 more per 1,000 (from 151 more to 295 more) | MD 3.42 lower (5.03 to 1.81 lower) | MD 2.22 lower (4.19 to 0.26 lower) | MD 3.12 lower (4.21 to 2.03 lower) | MD 3.96 lower (5.78 to 2.15 lower) | MD 10.16 lower (16.41 to 3.91 lower) | MD 8.65 lower (13.67 to 3.64 lower) | MD 10.47 higher (2.61 lower to 23.56 higher) |

| 232 more per 1,000 (from 158 more to 307 more) | ||||||||

| Grade | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝⊝ Low |

⊕ ⊕ ⊝⊝ Low |

⊕ ⊕ ⊝⊝ Low |

⊕ ⊕ ⊝⊝ Low |

⊕ ⊕ ⊝⊝ Low |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low |

Results of the evidence quality assessment.

Discussion

PMI involve multiple physiological and psychological factors (30, 31). Women in the perimenopausal stage often experience hormonal fluctuations, particularly in estrogen and progesterone, which play a key role in promoting neurotransmitter balance, improving circadian rhythm, adjusting sleep structure, and indirectly influencing mood. When hormonal levels become disrupted, it may lead to sleep disturbances, irritability, and other symptoms (3, 32, 33). Acupuncture modulates the HPO axis by stimulating estrogen receptor (ER)-positive neurons in the hypothalamus, promoting endogenous E2 secretion, while downregulating gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility to reduce elevated FSH/LH levels (34). Additionally, acupuncture enhances β-endorphin release from the arcuate nucleus, further stabilizing hormonal fluctuations (35, 36). Sleep is not only related to hormonal changes but is also closely linked to autonomic nervous function (37). Due to hormonal fluctuations, the imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems results in overactive sympathetic activity at night, leading to issues like rapid heart rate, hot flashes, night sweats, and anxiety, which in turn affect falling asleep and maintaining deep sleep (38). Acupuncture counteracts this by increasing heart rate variability (HRV), reflecting enhanced parasympathetic tone, and reducing nocturnal norepinephrine (NE) release (39, 40). Pharmacological agents like clonidine (an α2-adrenergic agonist) may further suppress sympathetic outflow, but acupuncture provides sustained autonomic nervous system (ANS) rebalancing without drug dependence (41). In TCM, PMS is categorized under conditions like “disorders before and after menopause” and “organ restlessness” associated with both internal and external factors. Clinically, herbal treatments such as Gan Mai Da Zao Decoction for nourishing yin and blood, and Chai Hu Long Gu Mu Li Decoction for relieving depressive fire are commonly used (42, 43). From a biomedical perspective, these formulations may exert effects via anti-inflammatory pathways (downregulating NF-κB and IL-6) and antioxidant activity (enhancing superoxide dismutase [SOD]), which are also targeted by acupuncture (44). Evidence from studies has indicated that acupuncture is effective in managing PMI, and acupuncture combined with Western medication, as an alternative therapy, has shown advantages across multiple outcome measures (45). Acupuncture works by regulating the HPO axis, improving hormone levels in perimenopausal women, significantly reducing LH and FSH levels, and increasing E2 levels post-treatment, indicating a positive effect on promoting endogenous hormone secretion and restoring hormonal balance (46). Moreover, acupuncture upregulates serotonin synthesis in the raphe nuclei and GABAergic activity in the hypothalamus, addressing neurotransmitter deficiencies linked to hyperarousal and mood disturbances (47, 48). Acupuncture also shows notable effects in neurological regulation. Research indicates that it can improve anxiety and depression by modulating neurotransmitter levels, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and dopamine (DA), effectively reducing HAMA scores (49). According to TCM theory, PMI is often caused by liver and kidney yin deficiency or heart and spleen deficiency. Acupuncture enhances TCMS scores by unblocking meridians and harmonizing qi and blood, aligning closely with the holistic concept of TCM (50). Modern studies correlate acupuncture points (GV20, HT7, SP6) with vagal stimulation, 5-HT release, and HPO axis modulation, bridging traditional mechanisms with biomedical evidence (51). The role of Western medication in combination therapy is mainly reflected in its impact on GABA receptors, thereby improving sleep quality, with significant advantages observed in PSQI and KMI improvement (52, 53). AP not only leverages the strengths of both approaches, acupuncture regulates the endocrine system, corrects neurotransmitter imbalances, and alleviates anxiety and depression, while Western medication provides rapid symptom control. The integration of AP produces a synergistic effect, with acupuncture partially mitigating the side effects of Western medication (45), making it a safe alternative therapy.

In this meta-analysis, the majority of included studies employed well-defined diagnostic criteria (mostly internationally recognized standards), while only a minority did not specify their diagnostic methods. This rigorous selection process enhances both the validity and clinical applicability of our findings. By focusing on studies that adopt standardized diagnostic thresholds endorsed by major clinical guidelines, we improved cross-study comparability, minimized diagnostic heterogeneity, and reduced misclassification bias. This methodological consistency ensures that our pooled results are both reliable and generalizable to patient populations meeting these widely accepted criteria. Moreover, the use of clearly defined diagnostic criteria enables more meaningful subgroup analyses and enhances the reproducibility of our study in future research.

Several outcome measures in this meta-analysis exhibited substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), which warrants careful consideration. Potential sources of variability may include differences within patient populations (disease severity, comorbidities), inconsistencies in practitioner technique, and variations in outcome assessment methods (subjective or objective measures) or follow-up durations. Importantly, potential confounding factors such as lifestyle variables (diet, exercise habits), concomitant medication use (hormone therapy, antidepressants), and socioeconomic status were not uniformly reported across studies, which may further contribute to heterogeneity. These factors could independently influence outcomes like sleep quality or mood scores, potentially obscuring the true treatment effect. To address this heterogeneity, we conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with high risk of bias or outliers, which partially reduced inconsistency in some outcomes. Subgroup analyses based on key baseline characteristics (sample size, age, duration, and course) further clarified effect estimates. For outcomes with high heterogeneity, biological mechanisms may offer explanations. For instance, individual variations in hormonal sensitivity (estrogen receptor polymorphisms) or neurotransmitter profiles (serotonin transporter gene variants) could modulate responses to acupuncture or pharmacotherapy. Similarly, variations in sleep outcomes may reflect population differences in how perimenopausal circadian disturbances interact with therapeutic interventions. Nevertheless, residual heterogeneity suggests that unmeasured factors, such as unstandardized co-interventions or publication bias, may still influence results. Given these limitations, the evaluation should be interpreted with caution, particularly for outcomes with high heterogeneity. Future research should prioritize standardized protocols and rigorous reporting to minimize variability and enhance comparability across studies.

Building on established longitudinal methodologies from mental health research, future studies should develop validated clinical prediction tools to identify perimenopausal women most likely to benefit from integrated AP. Three key prognostic domains warrant investigation: (1) biological markers (baseline cortisol, IL-6, and estrogen profiles); (2) sleep architecture parameters (PSQI sub-scores and actigraphy-measured sleep efficiency); (3) psychological phenotypes (HAMA depression cluster scores and stress resilience scales). The proposed framework could adapt linear mixed-effect methods from substance use research to model treatment response trajectories, potentially incorporating dynamic symptom networks mapping insomnia severity to endocrine-immune fluctuations, machine learning analysis of acupoint response patterns from electronic health records, and digital phenotyping via wearable sleep-stage validation —all of which are approaches that would collectively address current evidence gaps in personalized treatment selection for PMI.

Future clinical implementation of acupuncture-pharmacotherapy could benefit from targeted health campaigns and personalized approaches informed by psychological profiles, building on models from vaccination promotion research. Similar to COVID-19 vaccine uptake strategies that considered personality traits and social support, tailored interventions accounting for patients’ stress resilience and health beliefs may optimize treatment adherence. Integration with menopausal health programs could further enhance accessibility and acceptance of this combined therapy.

The strengths of the study are reflected in the following aspects: (1) The study involved a comprehensive search across 8 databases, ensuring a wide scope and thorough content coverage; (2) The analysis included 8 commonly used clinical outcome indicators, making the results more accurate and credible; (3) During the literature inclusion process, strict criteria were applied to select the interventions (with experimental group receiving AP and control group only receiving the corresponding Western medication), which helped to avoid excessive heterogeneity to some extent; (4) The article evaluates the efficacy of AP in PMI, and the analysis results demonstrate that the combination therapy is more advantageous than Western medication alone in treating PMI, highlighting the innovation and unique advantages of TCM combined with pharmacotherapy.

The studies still have some limitations: (1) While our systematic search strategy underwent multiple iterative refinements across 8 databases, the absence of formal peer review by an information specialist represents a potential limitation in search methodology rigor; (2) The limited number of eligible studies, all of which were conducted in Chinese, may lead to potential bias stemming from linguistic or regional influences, and the exclusion of gray literature further restricts the generalizability of findings by omitting potentially relevant unpublished data; (3) When collecting data, the same indicators in different studies had varying units, and some units lack internationally recognized conversion standards, making analysis challenging; (4) Some indicators still showed high heterogeneity, suggesting potential subgroup analyses may be needed; (5) The distinctive characteristics of acupuncture intervention make genuine practitioner blinding methodologically unattainable in clinical research; (6) Currently, high-quality, blinded RCTs are still lacking in clinical practice, which has precluded a comprehensive analysis of the correlation between treatment effects and clinically meaningful thresholds (MCID), and long-term follow-up has also not been achieved; (7) The overall quality of evidence is relatively low; (8) The regression results, while offering exploratory insights, are underpowered due to small subgroup sizes (often <10) and should be viewed as hypothesis-generating given risks of unreliable estimates or spurious associations.

Conclusion

While the combination therapy of AP demonstrates considerable therapeutic potential, its long-term efficacy and MCID warrant further investigation through large-scale, multicenter RCTs with extended follow-up periods, particularly for distinct insomnia subtypes. Future studies should prioritize protocol optimization to facilitate clinical translation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BY: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation. SJ: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization. YT: Software, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. YW: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization. JZ: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. CG: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. CS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Sincerely thank every member of the team for their efforts and contributions. We appreciate the editors’ dedication and responsibility, as well as the rigorous evaluations and valuable feedback from all the reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1633794/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Harlow SD Gass M Hall JE Lobo R Maki P Rebar RW et al . Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97:1159–68. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3362

2.

Duralde ER Sobel TH Manson JE . Management of perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. BMJ. (2023) 382:e072612. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072612

3.

Kang W Malvaso A Bruno F Chan CK . Psychological distress and myocardial infarction (MI): a cross-sectional and longitudinal UK population-based study. J Affect Disord. (2025) 384:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.05.016

4.

Kang W Malvaso A . Mental health in coronary heart disease (CHD) patients: findings from the UK household longitudinal study (UKHLS). Healthcare. (2023) 11:1364. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11101364

5.

Johansson T Karlsson T Bliuc D Schmitz D Ek WE Skalkidou A et al . Contemporary menopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease: Swedish nationwide register based emulated target trial. BMJ. (2024) 387:e078784. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078784

6.

Matheson EM Brown BD DeCastro AO . Treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. Am Fam Physician. (2024) 109:154–60.

7.

Chen BY . Acupuncture normalizes dysfunction of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Acupunct Electrother Res. (1997) 22:97–108. doi: 10.3727/036012997816356734

8.

Wu WZ Zheng SY Liu CY Qin S Wang XQ Hu JL et al . Effect of Tongdu Tiaoshen acupuncture on serum GABA and CORT levels in patients with chronic insomnia. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. (2021) 41:721–4. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20200704-k0001

9.

Zhang M Zhao N He JH Li JL . Effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on the postoperative sleep quality and inflammatory factors in frail elderly patients. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. (2023) 43:751–5. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20220919-k0002

10.

Antonio M Cerne D Sara B Sara B Enrico M Pietro B . Retrograde amnesia in LGI1 and CASPR2 limbic encephalitis: two case reports and a systematic literature review. Eur J Neurol. (2025) 32:e70113. doi: 10.1111/ene.70113

11.

Wang J Zhao H Shi K Wang M . Treatment of insomnia based on the mechanism of pathophysiology by acupuncture combined with herbal medicine: a review. Medicine. (2023) 102:e33213. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000033213

12.

Sun L Wang H . Acupuncture in the treatment of cocaine addiction: how does it work?Acupunct Med. (2024) 42:251–9. doi: 10.1177/09645284241248473

13.

Lee MY Lee BH Kim HY Yang CH . Bidirectional role of acupuncture in the treatment of drug addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2021) 126:382–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.004

14.

Wu XK Gao JS Ma HL Wang Y Zhang B Liu ZL et al . Acupuncture and Doxylamine-pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a randomized, controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Ann Intern Med. (2023) 176:922–33. doi: 10.7326/M22-2974

15.

David DJ Gourion D . Antidepressant and tolerance: determinants and management of major side effects. Encéphale. (2016) 42:553–61. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2016.05.006

16.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

17.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

18.

Bai R . Analysis of therapeutic value of jiaotong xinshen acupuncture combined with zopiclone tablets in the treatment of climacteric insomnia. Guangming J Chin Med. (2022) 37:3390–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2022.18.041

19.

Dai W Liao M Dai L . Clinical effect of electroacupuncture combined with escitalopram oxalate for perimenopausal depression. Hebei J Tradit Chin Med. (2022) 44:1177–80. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2619.2022.07.027

20.

Li X Huang D Zhang M . The efficacy of oral climen combined with acupuncture therapy in treating menopause-related sleep disorders. Pract Clin J Integr Tradition Chin West Med. (2019) 19:145–6. doi: 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2019.04.075

21.

Liu J Ma L Wang D Wang Y . Clinical observation on auricular acupuncture combined with femoston in treating perimenopausal insomnia of kidney deficiency and liver qi stagnation type. Modern J Integr Tradition Chin West Med. (2023) 32:2444–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2023.17.021

22.

Zhang X Zhang Z . Clinical observation on the treatment of perimenopausal insomnia with the xingshen qibi acupuncture method combined with flupentixol-melitracen tablets. J Pract Tradit Chin Med. (2024) 40:269–71.

23.

Zhou Y . Clinical observation of superficial needling on auricular point combine with estazolam in the treatment of perimenopausal insomnia with heart-kidney disharmony. Fuzhou, China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2022).

24.

Xue Y Chen L Hua C . Clinical effect of jieyu jianpi acupuncture combined with estazolam tablets on perimenopausal insomnia of liver spleen deficiency. Hebei J Tradit Chin Med. (2023) 45:1712–1716+1720. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2619.2023.10.030

25.

Zhu S Li P Zhu X . Observation of the therapeutic effect of tiao du an shen acupuncture method on perimenopausal insomnia. Modern J Integr Tradition Chin West Med. (2016) 25:2885–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2016.26.011

26.

Lv X Zheng Y . Observation on the efficacy of acupuncture combined with western medicine in treating perimenopausal syndrome. Chin J Rural Med Pharm. (2017) 24:59–60. doi: 10.19542/j.cnki.1006-5180.000127

27.

Zheng L Li Z . The effect of tiaodu anshen acupuncture method on insomnia in perimenopausal syndrome of heart-kidney disharmony type and its impact on sleep quality and sex hormone levels. J Med Pharmacy Chin Minor. (2023) 29:35–7. doi: 10.16041/j.cnki.cn15-1175.2023.11.002

28.

Li G . Effects of electroacupuncture assisted by progynova and progesterone on serum sex hormones, KI, MRS score in patients with perimenopausal syndrome. J Med Theory Pract. (2022) 35:4050–2. doi: 10.19381/j.issn.1001-7585.2022.23.035

29.

Han S Chen X . Clinical effect of agomeladine, acupuncture combined with conventional Western medical therapy on menopusal patient with functional dypepsia. Henan Med Res. (2020) 29:2539–42. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-437X.2020.14.014

30.

Kravitz HM Joffe H . Sleep during the perimenopause: a SWAN story. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. (2011) 38:567–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.06.002

31.

Shaver J Giblin E Lentz M Lee K . Sleep patterns and stability in perimenopausal women. Sleep. (1988) 11:556–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.6.556

32.

Freeman EW Sammel MD Liu L Gracia CR Nelson DB Hollander L . Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004) 61:62–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.62

33.

Soares CN Frey BN . Challenges and opportunities to manage depression during the menopausal transition and beyond. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (2010) 33:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.007

34.

Wang J Cheng K Qin Z Wang Y Zhai L You M . Effects of electroacupuncture at Guanyuan (CV 4) or Sanyinjiao (SP 6) on hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis and spatial learning and memory in female SAMP8 mice. J Tradit Chin Med. (2017) 37:96–100. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(17)30032-8

35.

Cai Y Zhang X Li J Yang W . Effect of acupuncture combined with Ningshen mixture on climacteric insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). (2024) 103:e37930. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037930

36.

Yu JS Zeng BY Hsieh CL . Acupuncture stimulation and neuroendocrine regulation. Int Rev Neurobiol. (2013) 111:125–40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411545-3.00006-7

37.

Ardawi MS Rouzi AA . Plasma adiponectin and insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2005) 83:1708–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.077

38.

Sowers MR Zheng H McConnell D Nan B Harlow SD Randolph JF Jr . Estradiol rates of change in relation to the final menstrual period in a population-based cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2008) 93:3847–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1056

39.

Akita T Kurono Y Yamada A Hayano J Minagawa M . Effects of acupuncture on autonomic nervous functions during sleep: comparison with nonacupuncture site stimulation using a crossover design. J Integr Complement Med. (2022) 28:791–8. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2022.0526

40.

Lin JG Kotha P Chen YH . Understandings of acupuncture application and mechanisms. Am J Transl Res. (2022) 14:1469–81.

41.

Li YW Li W Wang ST Gong YN Dou BM Lyu ZX . The autonomic nervous system: a potential link to the efficacy of acupuncture. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:1038945. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.1038945

42.

Lu J . Clinical observation on the efficacy of modified ganmai dazao decoction in treating insomnia in menopausal women. Acta Academiae Medicinae Militaris Tertiae. (2007) 29:1634–5. doi: 10.16016/j.1000-5404.2007.16.001

43.

Huang L Geng Y Du N . The mechanism of chaihu jia longgu muli decoction for improving sleep quality during perimenopause. Chin J Drug Depend. (2017) 26:345–8. doi: 10.13936/j.cnki.cjdd1992.2017.05.005

44.

Pan MH Chiou YS Tsai ML Ho CT . Anti-inflammatory activity of traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. J Tradit Complement Med. (2011) 1:8–24. doi: 10.1016/s2225-4110(16)30052-9

45.

Zhao FY Fu QQ Kennedy GA Conduit R Wu WZ Zhang WJ et al . Comparative utility of acupuncture and Western medication in the Management of Perimenopausal Insomnia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2021) 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2021/5566742

46.

Bromberger JT Schott LL Kravitz HM Sowers M Avis NE Gold EB et al . Longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and depressive symptoms across the menopausal transition: results from the study of women's health across the nation (SWAN). Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:598–607. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.55

47.

Yang TY Jang EY Ryu Y Lee GW Lee EB Chang S . Effect of acupuncture on lipopolysaccharide-induced anxiety-like behavioral changes: involvement of serotonin system in dorsal raphe nucleus. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2017) 17:528. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2039-y

48.

Wu Z Shen Z Xu Y Chen S Xiao S Ye J . A neural circuit associated with anxiety-like behaviors induced by chronic inflammatory pain and the anxiolytic effects of electroacupuncture. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2024) 30:e14520. doi: 10.1111/cns.14520

49.

Han Y Wu X Li X Feng J Zhou C . Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of abdominal acupuncture combined with Tiaoshen Jieyu acupuncture in the treatment of patients with perimenopausal insomnia based on 5-HT, DA, NE, 5-HIAA and sleep quality. Jilin J Chin Med. (2023) 43:728–32. doi: 10.13463/j.cnki.jlzyy.2023.06.025

50.

Tao X He Z Lv Y . Application of syndrome differentiation of traditional Chinese medicine in treating perimenopausal syndrome with acupuncture and moxibustion. Clin J Tradition Chin Med. (2016) 28:1224–7. doi: 10.16448/j.cjtcm.2016.0432

51.

Wu P Cheng C Song X Yang L Deng D Du Z . Acupoint combination effect of Shenmen (HT 7) and Sanyinjiao (SP 6) in treating insomnia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2020) 21:261. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4170-1

52.

Li J Mou N Song Y Lv C Cao D Ma H . Curative efficacy of dexzopiclone plus oryzanol tablet on anxiety insomnia and its influences on related neurotransmitters in perimenopausal women. Chin J Hosp Pharm. (2024) 44:941–5. doi: 10.13286/j.1001-5213.2024.08.13

53.

Varinthra P Anwar SNMN Shih SC Liu IY . The role of the GABAergic system on insomnia. Tzu Chi Med J. (2024) 36:103–9. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_243_23

Summary

Keywords

acupuncture, pharmacotherapy, perimenopause, insomnia, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation