Abstract

Speech production and comprehension are coordinated by a large-scale language network. The dynamic balance of intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity within this network is essential for normal language processing. Stroke often significantly disrupts both the functional integrity and dynamic balance of the language network, leading to language deficits (aphasia). However, the brain’s adaptive potential to compensate for lesions in post-stroke aphasia (PSA) remains incompletely understood. A key unresolved question is whether recovery of language function in PSA is primarily facilitated by compensatory mechanisms within the left hemisphere, increased recruitment (“upregulation”) in the right hemisphere, or both. Building on prior research, we defined a language network encompassing canonical language areas. We employed resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) to quantify functional connectivity (FC) and investigated differences in intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity within this network between 32 patients with PSA and 70 healthy controls (HCs). Furthermore, we examined the association between altered connectivity patterns at baseline and subsequent improvement in language function in the PSA group. Compared to the HCs, the patients with PSA exhibited increased intrahemispheric FC at baseline. Crucially, this increased intrahemispheric FC was positively correlated with the magnitude of language function improvement from baseline to follow-up. In addition, intrahemispheric FC was significantly higher than interhemispheric FC in the PSA group at baseline. These findings suggest that aberrant connectivity within the language network represents a neural substrate of language impairment in PSA and that heightened intrahemispheric connectivity within the residual left hemisphere language network may predict better recovery of language function in patients with subacute PSA. Collectively, network-based pathology analysis enhances our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying both lesion effects and functional recovery in PSA.

1 Introduction

Language represents a higher-order cognitive function foundational to human communication, instantiated by large-scale, distributed neural architecture. This architecture is predominantly supported by a left-lateralized network of brain regions located in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices (1, 2). However, previous research has demonstrated that engagement of right-hemisphere homologs becomes increasingly significant with rising linguistic complexity (3–5), underscoring the principle of bilateral, dynamic cooperation for maintaining linguistic fluency. Therefore, disruption of this network integrity—resulting from insults such as focal lesions (6, 7) or neurodegenerative diseases (8–10)—clinically manifests as aphasia.

Post-stroke aphasia (PSA) manifests as a spectrum of heterogeneous language deficits arising from the stroke-induced disruption of structural and functional integrity within the language network. While classic lesion-symptom mapping studies have robustly implicated damage to cortical language areas as a primary driver of these impairments (11), the network-level consequences are crucial, which are vividly illustrated by non-invasive brain stimulation studies. For instance, applying continuous theta-burst stimulation (cTBS) to the left temporal lobe transiently increases error rates in picture-naming tasks, mimicking a focal cortical deficit (12). Furthermore, lesions extending to subcortical structures and their associated white matter tracts can sever the critical links required for sound-to-production mapping, thereby compromising the entire articulatory–phonological processing loop (13–15).

Disconnection between cortical and subcortical structures also contributes to aphasia (16, 17). Conductive aphasia is often attributed to arcuate fasciculus (AF) lesions that disconnect receptive and expressive language regions (18, 19). Similarly, primary progressive aphasia (20)—a neurodegenerative disorder group characterized by predominant language deficits—stems from large-scale network degeneration involving white matter pathway alterations. Beyond structural damage, abnormal functioning of the left hemisphere language network impairs language processing. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies reveal reduced lateralization and activation in language production/processing areas in autism spectrum disorder (21, 22). Similarly, children with developmental language disorder or 22q11.2 deletion syndrome exhibit significantly reduced language-related activation during spoken language processing compared to typically developing peers (23). In summary, both structural and functional impairments within the left hemisphere language network can cause language deficits.

Although left hemisphere dominance for language is well-established, accumulating evidence implicates the right hemisphere in language processing (3, 24). Díaz et al. (25) demonstrated right-hemisphere activation during lexical-semantic processing in healthy participants. Consistent with this, patients with right-hemisphere infarction exhibited diverse language impairments (26). While left hemisphere facilitation of aphasia recovery is widely recognized, the role of the right hemisphere remains incompletely understood (27, 28). Some studies suggest that compensatory recruitment of right-hemisphere homologs aids language recovery (4), whereas others propose that increased right-hemisphere activity reflects release from transcallosal inhibition. Supporting the latter view, inhibitory low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) over the right inferior frontal gyrus improves picture-naming in chronic non-fluent aphasia (29, 30). Therefore, the right hemisphere contributes critically to both language execution and aphasia rehabilitation.

In summary, balanced interhemispheric connectivity is integral to uniquely human social communication (3, 24). Consistent with this view, Xu et al. (31) demonstrated that right-hemispheric recruitment increases with contextual complexity during task-based fMRI. These observations motivate a systematic investigation of intrahemispheric and interhemispheric coupling within the language network as a potential lever for optimizing PSA rehabilitation. However, the spatiotemporal dynamics of post-stroke connectivity reorganization are still incompletely defined.

Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) (32) is an ideal modality for mapping intrinsic neural circuits by capturing spontaneous, low-frequency BOLD signal fluctuations (33). From these data, we can compute functional connectivity (FC), a measure of temporal coherence between remote brain regions, typically indexed by the Pearson correlation of their respective time courses (34). Indeed, functional connectivity, derived from various neurophysiological signals, has proven to be a robust method for quantitatively assessing diverse cognitive states, including mental fatigue and emotional responses (35–39). Our prior study in subacute PSA demonstrated network disruption, specifically reduced FC between the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and both the bilateral supplementary motor areas and the right superior temporal gyrus (STG) (33). This aligns with findings in neurodegenerative conditions, where Montembeault et al. (40) observed decreased FC from the left anterior temporal lobe to bilateral language regions in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia relative to Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively unimpaired controls. Characterizing these connectivity patterns is fundamental to understanding large-scale network pathologies and the potential for functional restoration after brain injury.

This study investigates intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity changes between residual language regions and their relationship with language improvement in subacute PSA. We hypothesize that PSA involves aberrant connectivity within the residual language network and that its reorganization predicts language recovery. This study will inform network-based rehabilitation strategies for PSA.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

A total of 32 aphasic patients with left hemispheric stroke were enrolled at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China) (Supplementary Table S1), along with 70 age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy controls (HCs). Patients met the following inclusion criteria: (i) diagnosis of aphasia, (ii) age between 18 and 80 years, (iii) first-ever stroke, (iv) left hemisphere lesion, (v) right-handedness, and (vi) ≤ 3 months post-stroke onset. Both PSA patients and HCs were excluded if they had neurological/psychiatric disorders, head trauma history, or excessive head motion (>3 mm translation or >3° rotation). All 32 PSA patients underwent baseline fMRI and a language assessment (T1, <3 months post-stroke). A follow-up language assessment (T2) was conducted ≥4 weeks after T1. Due to various circumstances, 21 participants were lost to follow-up, ultimately leaving 11 patients who completed the T2 language assessment.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants/guardians. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Anhui Medical University Ethics Committee (2019H009).

2.2 Clinical evaluation

All patients underwent assessments of language performance using the Aphasia Battery of Chinese (ABC) (41), a Chinese standardized variant of the Western Aphasia Battery. The ABC consists of four subsections: spontaneous speech, auditory comprehension, repetition, and naming. The total score is 100, with a score below 93.8 indicating aphasia.

2.3 Neuroimaging data acquisition

MR images were acquired on a 3.0-Tesla MR system (Discovery MR750, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, United States). During the MRI scan, all participants were asked to close their eyes, remain awake, and not think about anything or move their bodies. All resting-state functional images were acquired using the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2,400 ms, flip angle = 90°, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, slice thickness = 3 mm, matrix size = 64 × 64, field of view = 192 × 192 mm2, and 46 continuous slices (one voxel = 3 × 3 × 3 mm3). We also obtained 188 T1-weighted anatomic images in sagittal orientation for each participant, with the following parameters: TR = 8.16 ms, TE = 3.18 ms, flip angle = 12°, field of view = 256 × 256 mm2, slice thickness = 1 mm, and voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3.

2.4 Resting-state fMRI preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI data were preprocessed using the Data Processing and Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging toolkit (DPABI) (42). The processing steps for each participant were as follows: First, the first five functional volumes were discarded to ensure magnetization stability. Next, slice-timing correction and head motion correction were applied to the remaining volumes. Individual anatomic images were co-registered to functional images. Subsequently, the functional images were spatially normalized to standard space using the DARTEL template, applied separately for each group. After spatial normalization, nuisance regression was performed using the 24 Friston motion parameters, white matter high signals, and cerebrospinal fluid signals as regressors. Finally, spatial smoothing (Gaussian kernel = 4 × 4 × 4 mm3) and a band-pass filter (0.01–0.1 Hz) were applied to the functional images.

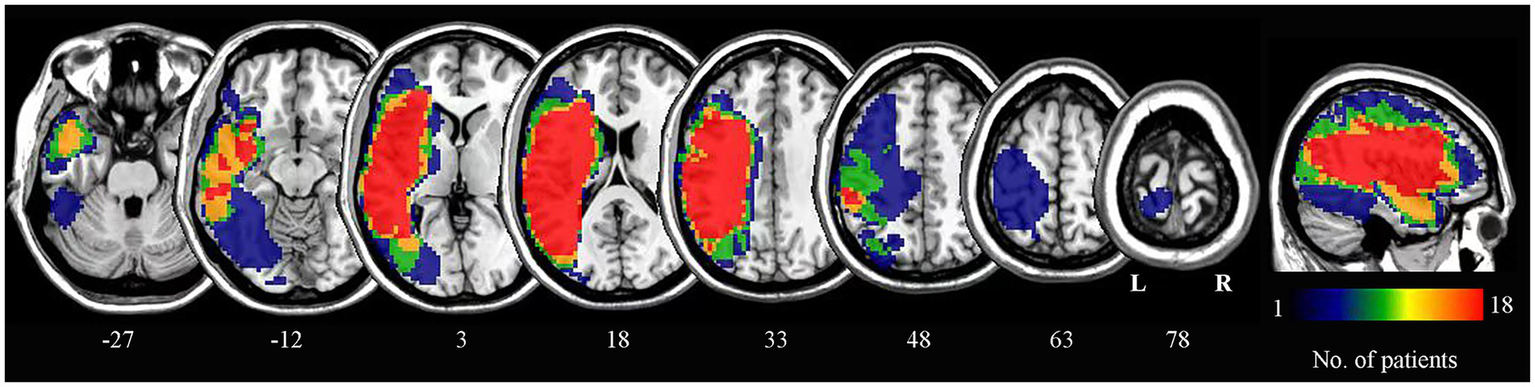

2.5 Lesion overlap map

Lesion outlines were manually traced by a trained researcher on individual 3D T1-weighted structural images using the pen tool in MRIcron software to create a lesion mask for each patient. The transformation matrix derived from normalizing the individual 3D anatomical images to standard space was then applied to normalize each lesion mask to the same standard space. The normalized lesion masks from all patients were overlaid to construct the lesion overlap map (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Lesion overlap map for all patients. The numbers below each axial slice correspond to z-plane coordinates in MNI space. The color scale indicates the number of patients with lesions in each voxel. L, left; R, right.

2.6 Defining regions of interest of language areas

Given the left-lateralized nature of the language network, our analysis focused on perisylvian language regions, including the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and superior temporal gyrus (STG). These areas encompass the classical Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, which underlie language production and comprehension (6, 43). A total of eight regions of interest (ROIs) within these structures were selected to compute the language network (Table 1), consistent with prior validated methodologies for language network mapping (44).

Table 1

| Hemisphere | Brain regions | MNI (x, y, z) |

|---|---|---|

| Left | IFG | −48, 30, −2 |

| Left | IFG | −44, 25, −2 |

| Left | IFG | −50, 19, 9 |

| Left | MFG | −45, 14, 21 |

| Left | STG | −54, −23, −3 |

| Left | STG | −56, −33, 3 |

| Left | STG | −48, −44, 3 |

| Left | STG | −52, −54, 12 |

Regions of interest (ROIs) in the language network.

Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates of peak activation points for the eight ROIs. IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; ROI, region of interest.

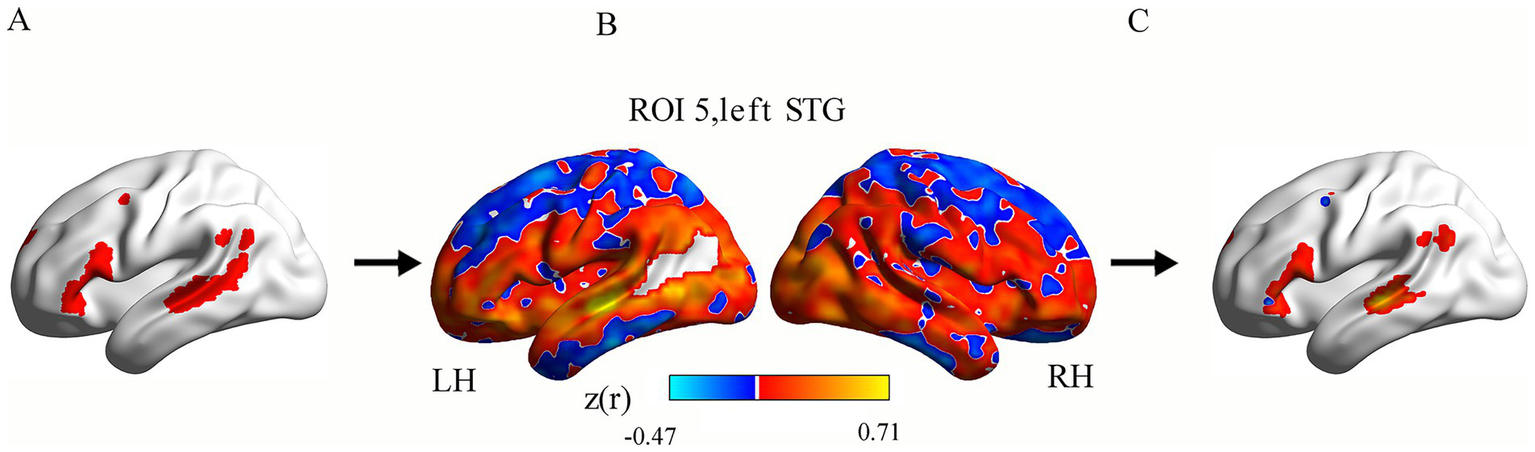

2.7 Calculating the language network map in the healthy controls

In the cohort of 70 healthy controls, we derived a language network map using language-associated ROIs. This normative map served as a mask to extract intrahemispheric and interhemispheric functional connectivity (FC) values in the PSA patients. The computational methodology for FC quantification in this language network comprised the following steps: First, for each participant, region-specific FC maps were generated by computing Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between the time course of each ROI and all other voxels within the brain. Second, subject-level mean FC maps were generated by averaging FC maps across all ROIs. Subsequently, r-values in these mean maps were converted to z-values using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Finally, the group-level language network map was generated by averaging all subject-level mean FC maps. All the voxels with z(r) > 0.3 formed the final language network mask in the group-level FC map. This specific value is explicitly used and described in numerous high-impact neuroimaging studies (44, 45). Then, this language network mask was partitioned into left (Figure 2A) and right hemisphere (not shown) components for subsequent analyses.

Figure 2

Calculation pipeline for intrahemispheric functional connectivity (FC) within the language network in a single patient. Panel (A) exhibits the left hemisphere language network (red). Panel (B) displays one patient’s ROI-based FC map for an ROI (e.g., left STG). Orange-yellow colors show voxels with positive FC with the ROI, while blue colors show negative FC. Panel (C) shows that each ROI-based FC map was masked using the language network template, producing ROI-masked FC maps. ROI, region of interest; FC, functional connectivity; STG, superior temporal gyrus; LH, left hemisphere; RH, right hemisphere.

2.8 ROI-based functional connectivity analysis in post-stroke aphasia

For each PSA patient, the following processing pipeline was implemented: First, Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were computed between each ROI’s time series and all voxels within the remaining brain (excluding lesioned areas). Fisher’s r-to-z transformation converted the coefficients to normalized z-values, generating eight ROI-based FC maps per participant. Second, each ROI-based FC map (Figure 2B) was masked using the language network template (derived from the HCs; voxel inclusion threshold: z(r) > 0.3; Figure 2A), producing ROI-masked FC maps (Figure 2C). Finally, we computed intrahemispheric FC as the mean z-value across voxels in the left hemisphere language mask for all ROI-masked FC maps, with interhemispheric FC similarly derived from the right-hemisphere language mask.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Independent samples t-tests were used to compare age and education years between the PSA patients and HCs. A chi-squared test compared sex distributions. For FC analyses, independent samples t-tests assessed intergroup (PSA vs. HC) differences in intrahemispheric and interhemispheric FC values, while Wilcoxon signed-rank tests evaluated intrahemispheric versus interhemispheric FC differences within the PSA group. Correlation analyses examined baseline functional variables versus language scores at T1 and T2. Partial correlations (controlling for time interval variability) quantified relationships between functional variables and language improvement (T2–T1). A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was used (two-tailed, uncorrected).

3 Results

3.1 Demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 32 patients with PSA and 70 healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients (mean age 55.22 ± 11.79 years) and HCs (mean age 54.63 ± 12.75 years) are summarized in Table 2. No significant differences were found in age, education years, or sex distribution between the groups. A total of 11 PSA patients (mean age 53.09 ± 12.02 years) completed follow-up language assessments. Significantly higher scores were observed at follow-up compared to baseline for the Aphasia Quotient (AQ) and all four subsections (Table 3).

Table 2

| Demographic indicators | PSA (n = 32) | HC (n = 70) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 31/1 | 65/5 | 0.73a |

| Age (years) | 55.22 ± 11.79 | 54.63 ± 12.75 | 0.85b |

| Education (years) | 9.06 ± 3.41 | 9.80 ± 3.44 | 0.38b |

| Disease duration (weeks) | 4.00 ± 3.09 | NA | NA |

| Lesion size (cm3) | 42.41 ± 36.77 | NA | NA |

| ABC scores | |||

| Spontaneous speechc | 8.59 ± 6.39 | NA | NA |

| Auditory comprehensionc | 5.84 ± 2.45 | NA | NA |

| Repetitionc | 3.34 ± 3.49 | NA | NA |

| Namingc | 2.26 ± 2.76 | NA | NA |

| AQc | 40.07 ± 26.87 | NA | NA |

Demographic characteristics of the patients and healthy controls and clinical features of the patients.

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation; aChi-squared test between the healthy controls and patients at baseline; bIndependent samples t-test; cStandardized scores according to the Western Aphasia Battery. PSA, post-stroke aphasia; HC, healthy controls; AQ, Aphasia Quotient.

Table 3

| Language performance (n = 11) | T1 | T2 | t/Z value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous speech | 7.91 ± 7.20 | 16.09 ± 3.83 | 3.839 | 0.003b |

| Auditory comprehension | 6.39 ± 1.88 | 8.22 ± 1.64 | 4.247 | 0.002b |

| Repetition | 3.09 ± 3.70 | 6.45 ± 3.60 | −2.936 | 0.003a |

| Naming | 1.80 ± 2.41 | 7.30 ± 3.97 | 4.841 | 0.001b |

| AQ | 38.39 ± 28.42 | 73.19 ± 27.82 | 3.985 | 0.003b |

Comparison of language performance at baseline and follow-up in the patients.

T1, within 3 months of stroke onset; T2, at least 4 weeks after T1; AQ, Aphasia Quotient; aWilcoxon signed-rank test; bpaired samples t-test. n = 11 patients who completed language assessments at both T1 and T2.

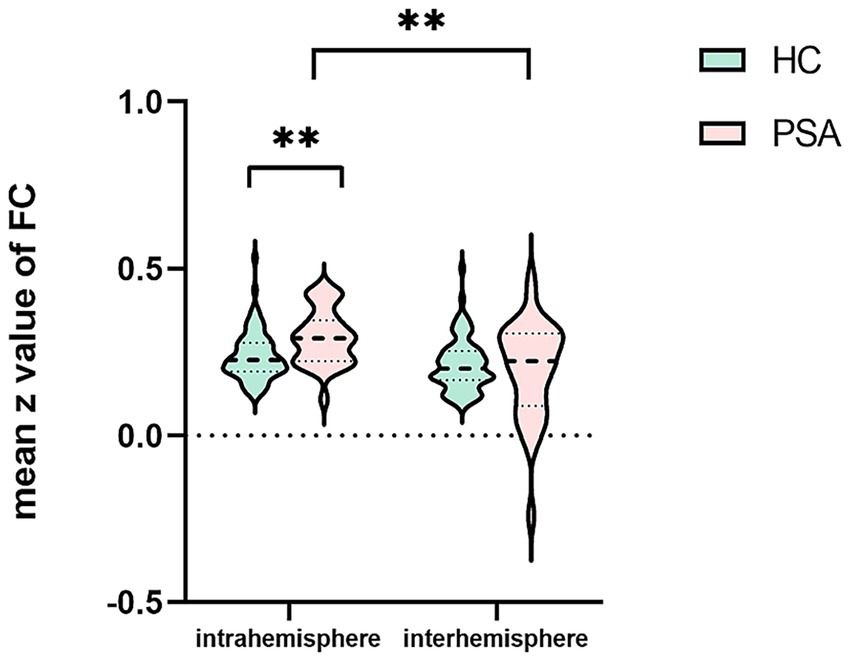

3.2 FC analysis

Compared to the HCs, the PSA patients exhibited significantly increased intrahemispheric FC (t = 3.367, p < 0.01; Table 4; Figure 3). In addition, intrahemispheric FC was stronger than interhemispheric FC in both PSA patients and HCs (PSA: Z = − 3.902, p < 0.01; HC: t = 4.751, p < 0.01; Table 5; Figure 3). No significant intergroup differences emerged in interhemispheric FC (Table 4).

Table 4

| Functional connectivity | PSA (n = 32) | HC (n = 70) | t value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrahemispheric FC | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 3.367 | 0.001a |

| Interhemispheric FC | 0.20 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | −0.477 | 0.636a |

Comparison of intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity between the patients and healthy controls.

aIndependent samples t-test. FC, functional connectivity; PSA, post-stroke aphasia; HC, healthy controls.

Figure 3

Intrahemispheric and interhemispheric functional connectivity (FC) in the patients with post-stroke aphasia (PSA) and healthy controls (HCs). **p < 0.01.

Table 5

| Participants | Intrahemispheric FC | Interhemispheric FC | Z/t value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSA (n = 32) | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.14 | −3.902 | <0.001a |

| HC (n = 70) | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 4.751 | <0.001b |

Differences in intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity within the patients and healthy controls.

aWilcoxon signed-rank test; bpaired samples t-test. FC, functional connectivity; PSA, post-stroke aphasia; HC, healthy controls.

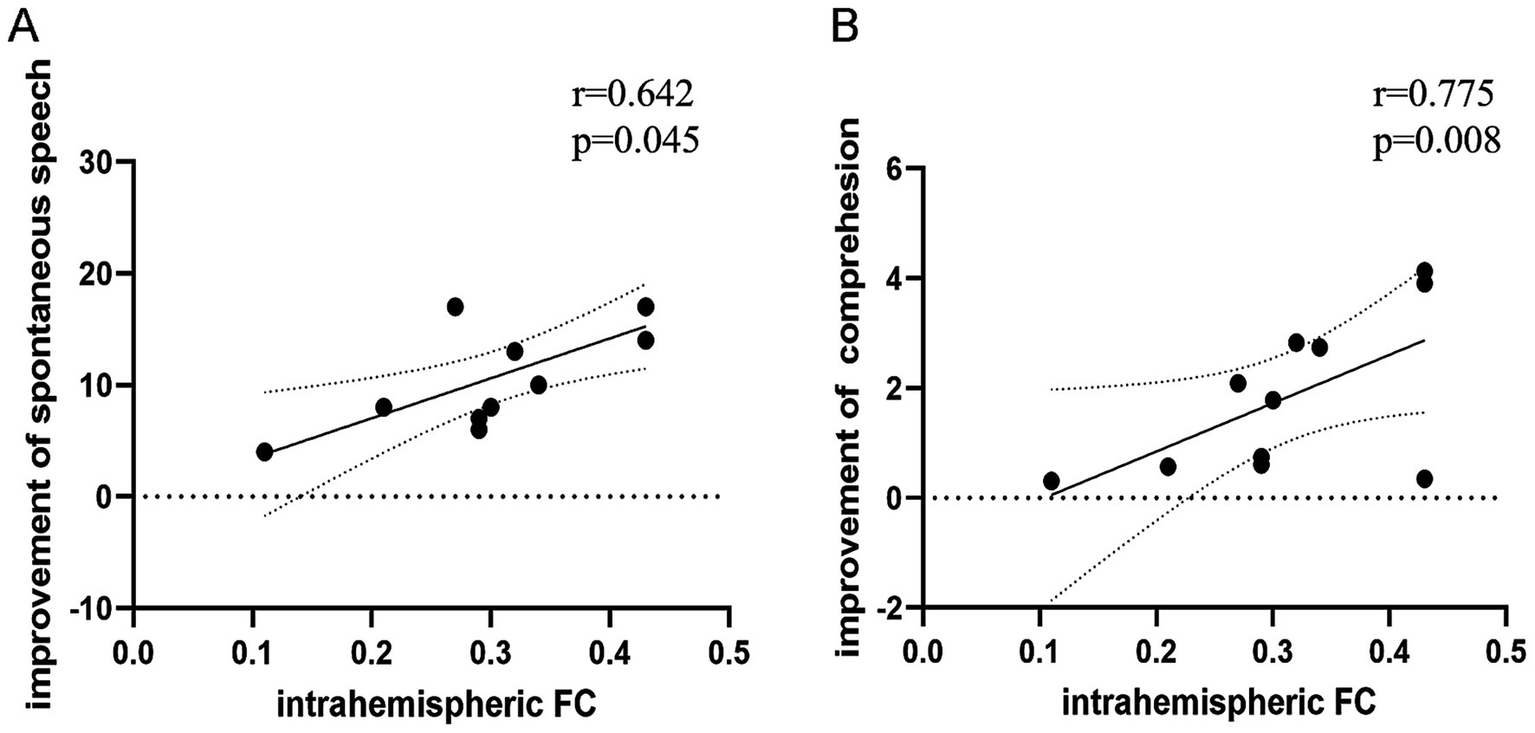

3.3 Correlations of FC abnormalities with clinical symptoms

Baseline intrahemispheric FC correlated positively with improvement in spontaneous speech (r = 0.642, p = 0.045) and auditory comprehension (r = 0.775, p = 0.008) scores from baseline to follow-up (partial correlation analysis; Table 6; Figure 4). No significant associations were found between FC and improvements in other ABC subsections (Table 6), nor between baseline FC and language scores (AQ/subsections) at baseline (Supplementary Table S2) or follow-up (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 6

| The improvement of language performance (n = 11) | Intrahemispheric FC | Interhemispheric FC |

|---|---|---|

| The improvement of spontaneous speech | (0.642, 0.045*) | (0.240, 0.504) |

| The improvement of auditory comprehension | (0.775, 0.008**) | (0.220, 0.542) |

| The improvement of repetition | (0.437, 0.207) | (0.410, 0.239) |

| The improvement of naming | (0.374, 0.288) | (0.482, 0.159) |

| The improvement of AQ | (0.574, 0.082) | (0.506, 0.136) |

Correlation between baseline functional connectivity (FC) and improvements in language scores from baseline to follow-up in the patients (r, p).

FC, functional connectivity; AQ, Aphasia quotient. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Statistical analysis: Partial correlations were performed between baseline functional connectivity (FC) and improvements in language scores from baseline to follow-up. n = 11 patients who completed language assessments at both T1 and T2.

Figure 4

Correlation between baseline functional connectivity (FC) and improvements in language scores from baseline to follow-up. (A) Intrahemispheric FC positively correlated with improvement in spontaneous speech (r = 0.642, p = 0.045). (B) Intrahemispheric FC positively correlated with improvement in auditory comprehension (r = 0.775, p = 0.008; two-tailed, uncorrected).

4 Discussion

Rs-fMRI was employed to investigate functional alterations in intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity within the language network of PSA patients and examine correlations between these connectivity patterns and language recovery. Our study suggests that reorganization of residual language network connectivity predicts language recovery of aphasia following left hemisphere lesions.

Our ROIs focused on core language regions—IFG, MFG, and STG—consistent with established language network models (6, 46, 47). While this selection does not represent the entire language system, these regions constitute canonical perisylvian language areas. The IFG is fundamentally associated with language production, with lesions resulting in Broca’s aphasia (48). The STG supports auditory comprehension, while the MFG contributes to integrative language processes (49). Task-based fMRI studies confirm robust activation of the IFG during speech production and the STG during comprehension tasks (43). Using these anatomically and functionally defined ROIs, we generated a normative language network from the HCs, which subsequently enabled the quantification of intrahemispheric and interhemispheric FC alterations in subacute PSA.

Consistent with established theory (50–52), both PSA patients and HCs exhibited stronger intrahemispheric FC than interhemispheric FC within the language network. Crucially, the PSA patients demonstrated significantly enhanced intrahemispheric FC, while interhemispheric FC showed no significant group differences—although a trend toward reduced interhemispheric connectivity was observed in the patients with PSA compared to the HCs. This pattern suggests that post-stroke functional reorganization preferentially engages residual language areas within the left hemisphere, potentially at the expense of interhemispheric integration. Stroke-induced disruption of language networks triggers compensatory reorganization (13, 53–55), with our results indicating early-stage reliance on intrahemispheric pathways.

This finding aligns with longitudinal studies documenting increased left hemisphere connectivity during the acute-to-subacute transition in PSA (56, 57). This interpretation is reinforced by Saur et al.’s (58) task-based fMRI findings, which showed left hemisphere hyperactivation exceeding healthy control levels during the subacute phase. Our prior observation of reduced left IFG–right hemisphere connectivity further supports this model of intrahemispheric compensation (33). These converging findings underscore the pivotal role of the residual left hemisphere region in language rehabilitation. This upregulated intrahemispheric connectivity likely represents a key mechanism underlying early language network adaptation following left hemisphere lesions.

Compared to the healthy controls, the PSA patients exhibited increased intrahemispheric functional connectivity that positively correlated with language recovery—particularly in spontaneous speech and auditory comprehension domains. This pattern likely reflects compensatory reorganization within residual left hemisphere language networks. The dynamic interactions among classical language areas underlie complex linguistic functions (6, 59). This interpretation is substantiated by complementary evidence: Fridriksson et al. (60) demonstrated that increased activation in preserved left hemisphere regions correlates with improved language outcomes in aphasia, while significant associations exist between comprehension recovery and intrinsic connectivity changes within left frontoparietal networks (61). These observations likely reflect upregulated activity within residual language networks, serving as potential predictors of language improvement. Consequently, therapeutic strategies should prioritize modulation of preserved intrahemispheric connectivity as a primary objective for functional recovery.

The primary limitations of this study include its modest sample size and limited follow-up retention. Additional constraints merit consideration: First, our language network was derived from only eight regions of interest, which may inadequately represent the full complexity of post-stroke language reorganization; second, the inclusion of heterogeneous aphasia subtypes without classification analysis; and third, correlation analyses lacked correction for multiple comparisons. Future investigations should validate these findings using larger cohorts, longer follow-up periods, and expanded ROI selections. Furthermore, exploring differential neural mechanisms across aphasia classifications represents a valuable research direction.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrated significantly stronger intrahemispheric than interhemispheric FC in PSA. Furthermore, the PSA patients exhibited increased intrahemispheric FC relative to the HCs. Critically, enhanced intrahemispheric FC correlated positively with language improvement in aphasia. These findings highlight the importance of preserved left hemisphere regions for language recovery after stroke. Elucidating these network mechanisms in subacute PSA offers valuable insights for developing targeted rehabilitation strategies and informing individualized therapeutic interventions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Anhui Medical University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XX: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Conceptualization, Visualization. YZ: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. MZ: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Visualization. KW: Validation, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. PH: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 82171917, 82471271, and U23A20424).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1634902/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Güntürkün O Ströckens F Ocklenburg S . Brain lateralization: a comparative perspective. Physiol Rev. (2020) 100:1019–63. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2019,

2.

Roll M . Heschl's gyrus and the temporal pole: the cortical lateralization of language. NeuroImage. (2024) 303:120930. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2024.120930,

3.

Keser Z Sebastian R Hasan KM Hillis AE . Right hemispheric homologous language pathways negatively predicts Poststroke naming recovery. Stroke. (2020) 51:1002–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028293,

4.

Sihvonen AJ Vadinova V Garden KL Meinzer M Roxbury T O'Brien K et al . Right hemispheric structural connectivity and poststroke language recovery. Hum Brain Mapp. (2023) 44:2897–904. doi: 10.1002/hbm.26252,

5.

Yang FG Edens J Simpson C Krawczyk DC . Differences in task demands influence the hemispheric lateralization and neural correlates of metaphor. Brain Lang. (2009) 111:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2009.08.006,

6.

Fridriksson J den Ouden D-B Hillis AE Hickok G Rorden C Basilakos A et al . Anatomy of aphasia revisited. Brain. (2018) 141:848–62. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx363,

7.

Kristinsson S den Ouden DB Rorden C Newman-Norlund R Johnson L Wilmskoetter J et al . Partial least squares multimodal analysis of brain network correlates of language deficits in aphasia. Brain Commun. (2025) 7:246. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaf246,

8.

Marshall CR Hardy CJD Volkmer A Russell LL Bond RL Fletcher PD et al . Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol. (2018) 265:1474–90. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6,

9.

Michelutti M Huppertz H-J Volkmann H Anderl-Straub S Urso D Tafuri B et al . Multiparametric MRI-based biomarkers in the non-fluent and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol. (2025) 272:490. doi: 10.1007/s00415-025-13215-9,

10.

Canu E Agosta F Lumaca L Basaia S Castelnovo V Santicioli S et al . Connected speech alterations and progression in patients with primary progressive aphasia variants. Neurology. (2025) 104:e213524. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000213524,

11.

Na Y Jung J Tench CR Auer DP Pyun SB . Language systems from lesion-symptom mapping in aphasia: a meta-analysis of voxel-based lesion mapping studies. Neuroimage Clin. (2022) 35:103038. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103038,

12.

Klaus J Schutter D Piai V . Transient perturbation of the left temporal cortex evokes plasticity-related reconfiguration of the lexical network. Hum Brain Mapp. (2020) 41:1061–71. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24860,

13.

Jiang Z Kuhnke P Stockert A Wawrzyniak M Halai A Saur D et al . Dynamic reorganization of task-related network interactions in post-stroke aphasia recovery. Brain. (2025) 30:awaf036. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaf036

14.

Vukovic M Sujic R Petrovic-Lazic M Miller N Milutinovic D Babac S et al . Analysis of voice impairment in aphasia after stroke-underlying neuroanatomical substrates. Brain Lang. (2012) 123:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.06.008,

15.

Parvizi J . Corticocentric myopia: old bias in new cognitive sciences. Trends Cogn Sci. (2009) 13:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.04.008,

16.

Li H Xie X . Cerebellar activity and functional connectivity in subacute subcortical aphasia: association with language recovery. Neuroscience. (2025) 565:320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.11.077,

17.

Gibson M Maydeu-Olivares A Newman-Norlund R Rorden C . Beyond the cortex: cerebellar contributions to apraxia of speech in stroke survivors. Cortex. (2025) 191:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2025.07.004,

18.

Zhang B Schnakers C Wang KX-L Wang J Lee S Millan H et al . Infratentorial white matter integrity as a potential biomarker for post-stroke aphasia. Brain Commun. (2025) 7:174. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaf174,

19.

Bernal B Ardila A . The role of the arcuate fasciculus in conduction aphasia. Brain. (2009) 132:2309–16. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp206,

20.

Mahoney CJ Malone IB Ridgway GR Buckley AH Downey LE Golden HL et al . White matter tract signatures of the progressive aphasias. Neurobiol Aging. (2013) 34:1687–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.002,

21.

Ashida R Nazar N Edwards R Teo M . Cerebellar mutism syndrome: an overview of the pathophysiology in relation to the Cerebrocerebellar anatomy, risk factors, potential treatments, and outcomes. World Neurosurg. (2021) 153:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.06.065,

22.

Suresh H Morgan BR Mithani K Warsi NM Yan H Germann J et al . Postoperative cerebellar mutism syndrome is an acquired autism-like network disturbance. Neuro-Oncology. (2024) 26:950–64. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noad230,

23.

Vansteensel MJ Selten IS Charbonnier L Berezutskaya J Raemaekers MAH Ramsey NF et al . Reduced brain activation during spoken language processing in children with developmental language disorder and children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neuropsychologia. (2021) 158:107907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107907,

24.

Lindell AK . In your right mind: right hemisphere contributions to language processing and production. Neuropsychol Rev. (2006) 16:131–48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9011-9,

25.

Diaz MT Eppes A . Factors influencing right hemisphere engagement during metaphor comprehension. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:414. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00414,

26.

Alexander MP Fischette MR Fischer RS . Crossed aphasias can be mirror image or anomalous. Case reports, review and hypothesis. Brain. (1989) 112:953–73.

27.

Turkeltaub PE . Brain stimulation and the role of the right hemisphere in aphasia recovery. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2015) 15:72. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0593-6,

28.

Cocquyt EM De Ley L Santens P Van Borsel J De Letter M . The role of the right hemisphere in the recovery of stroke-related aphasia: a systematic review. J Neurolinguistics. (2017) 44:68–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.03.004

29.

Gan L Huang L Zhang Y Yang X Li L Meng L et al . Effects of low-frequency rTMS combined with speech and language therapy on Broca's aphasia in subacute stroke patients. Front Neurol. (2024) 15:1473254. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1473254,

30.

Barwood CHS Murdoch BE Whelan BM Lloyd D Riek S O'Sullivan JD et al . Improved receptive and expressive language abilities in nonfluent aphasic stroke patients after application of rTMS: an open protocol case series. Brain Stimul. (2012) 5:274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.03.005,

31.

Xu J Kemeny S Park G Frattali C Braun A . Language in context: emergent features of word, sentence, and narrative comprehension. NeuroImage. (2005) 25:1002–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.013,

32.

Mirzaei G Adeli H . Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging processing techniques in stroke studies. Rev Neurosci. (2016) 27:871–85. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0052,

33.

Xie X Hu P Tian Y Qiu B Wang K Bai T . Abnormal resting-state function within language network and its improvement among post-stroke aphasia. Behav Brain Res. (2023) 443:114344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114344,

34.

Greicius MD Krasnow B Reiss AL Menon V . Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100,

35.

Xu T Xu L Zhang H Ji Z Li J Bezerianos A et al . Effects of rest-break on mental fatigue recovery based on EEG dynamic functional connectivity. Biomed Signal Process Control. (2022) 77:806. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103806

36.

Wang H Liu X Hu H Wan F Li T Gao L et al . Dynamic reorganization of functional connectivity unmasks fatigue related performance declines in simulated driving. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. (2020) 28:1790–9. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2020.2999599,

37.

Chen C Li Z Wan F Xu L Bezerianos A Wang H . Fusing frequency-domain features and brain connectivity features for cross-subject emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. (2022) 71:1–15. doi: 10.1109/TIM.2022.3168927,

38.

Wang H Liu X Li J Xu T Bezerianos A Sun Y et al . Driving fatigue recognition with functional connectivity based on phase synchronization. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst. (2021) 13:668–78. doi: 10.1109/TCDS.2020.2985539

39.

Liu X Li T Tang C Xu T Chen P Bezerianos A et al . Emotion recognition and dynamic functional connectivity analysis based on EEG. IEEE Access. (2019) 7:143293–302. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2945059

40.

Montembeault M Chapleau M Jarret J Boukadi M Laforce R Jr Wilson MA et al . Differential language network functional connectivity alterations in Alzheimer's disease and the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Cortex. (2019) 117:284–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.03.018,

41.

Gao S Chu Y Shi S Peng Y Dai S Wang Y . A standardization research of the aphasia battery of Chinese. Chin Ment Health J. (1992) 6:125–8.

42.

Yan CG Wang XD Zuo XN Zang YF . DPABI: Data Processing & Analysis for (resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics. (2016) 14:339–51. doi: 10.1007/s12021-016-9299-4,

43.

Weber S Hausmann M Kane P Weis S . The relationship between language ability and brain activity across language processes and modalities. Neuropsychologia. (2020) 146:107536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107536,

44.

Baldassarre A Metcalf NV Shulman GL Corbetta M . Brain networks' functional connectivity separates aphasic deficits in stroke. Neurology. (2019) 92:e125–35. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006738,

45.

Baldassarre A Ramsey L Rengachary J Zinn K Siegel JS Metcalf NV et al . Dissociated functional connectivity profiles for motor and attention deficits in acute right-hemisphere stroke. Brain. (2016) 139:2024–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww107,

46.

Alyahya RSW Halai AD Conroy P Lambon Ralph MA . A unified model of post-stroke language deficits including discourse production and their neural correlates. Brain. (2020) 143:1541–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa074,

47.

Hickok G Poeppel D . Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. (2004) 92:67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011,

48.

Nasios G Dardiotis E Messinis L . From Broca and Wernicke to the neuromodulation era: insights of brain language networks for neurorehabilitation. Behav Neurol. (2019) 2019:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2019/9894571,

49.

Friederici AD . The cortical language circuit: from auditory perception to sentence comprehension. Trends Cogn Sci. (2012) 16:262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.001,

50.

Tao Y Tsapkini K Rapp B . Inter-hemispheric synchronicity and symmetry: the functional connectivity consequences of stroke and neurodegenerative disease. NeuroImage Clin. (2022) 36:103263. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103263,

51.

Guo J Biswal BB Han S Li J Yang S Yang M et al . Altered dynamics of brain segregation and integration in poststroke aphasia. Hum Brain Mapp. (2019) 40:3398–409. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24605,

52.

Chu R Meltzer JA Bitan T . Interhemispheric interactions during sentence comprehension in patients with aphasia. Cortex. (2018) 109:74–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2018.08.022,

53.

Thiel A Zumbansen A . The pathophysiology of post-stroke aphasia: a network approach. Restor Neurol Neurosci. (2016) 34:507–18. doi: 10.3233/RNN-150632,

54.

Siegel JS Ramsey LE Snyder AZ Metcalf NV Chacko RV Weinberger K et al . Disruptions of network connectivity predict impairment in multiple behavioral domains after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E4367–76. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521083113,

55.

Hartwigsen G Bzdok D Klein M Wawrzyniak M Stockert A Wrede K et al . Rapid short-term reorganization in the language network. eLife. (2017) 6:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25964,

56.

Stockert A Wawrzyniak M Klingbeil J Wrede K Kummerer D Hartwigsen G et al . Dynamics of language reorganization after left temporo-parietal and frontal stroke. Brain. (2020) 143:844–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa023,

57.

Nenert R Allendorfer JB Martin AM Banks C Vannest J Holland SK et al . Longitudinal fMRI study of language recovery after a left hemispheric ischemic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. (2018) 36:359–85. doi: 10.3233/RNN-170767,

58.

Saur D Lange R Baumgaertner A Schraknepper V Willmes K Rijntjes M et al . Dynamics of language reorganization after stroke. Brain. (2006) 129:1371–84. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl090,

59.

Fridriksson J Yourganov G Bonilha L Basilakos A Den Ouden DB Rorden C . Revealing the dual streams of speech processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:15108–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614038114,

60.

Fridriksson J Richardson JD Fillmore P Cai B . Left hemisphere plasticity and aphasia recovery. NeuroImage. (2012) 60:854–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.057,

61.

Zhu D Chang J Freeman S Tan Z Xiao J Gao Y et al . Changes of functional connectivity in the left frontoparietal network following aphasic stroke. Front Behav Neurosci. (2014) 8:167. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00167,

Summary

Keywords

intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity, resting-state functional magnetic resonance, language network, post-stroke aphasia, subacute

Citation

Xie X, Zhan Y, Zhang M, Wang K and Hu P (2025) Relationship between intrahemispheric and interhemispheric connectivity of the language network and language improvement in subacute post-stroke aphasia. Front. Neurol. 16:1634902. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1634902

Received

25 May 2025

Accepted

05 September 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Manuela Tondelli, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy

Reviewed by

Zulay R. Lugo, Central University of Venezuela, Venezuela

Hongtao Wang, Wuyi University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xie, Zhan, Zhang, Wang and Hu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaohui Xie, xiexiaohui0318@126.com; Kai Wang, wangkai1964@126.com; Panpan Hu, hpppanda9@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.