Abstract

Objective:

The study aimed to explore the correlation between the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) and acute ischemic stroke in youth.

Methods:

A retrospective study was conducted. A total of 90 patients aged 18–45 years with acute ischemic stroke were included in the youth cerebral infarction (YCI) group, and 50 patients within the same age bracket without stroke or intracranial atherosclerosis, who were hospitalized during the same period, were included in the control group. Clinical information, blood biochemical indicators, and imaging data of the participants were analyzed. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the independent association between the SIRI and YCI. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis was performed on YCI patients. The subgroup classification included (i) infarct volume grouping; (ii) intracranial artery stenosis grouping; (iii) the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification grouping; (iv) infarct distribution grouping; and (v) vasculopathy grouping.

Results:

The SIRI values were higher in the YCI group compared to the control group (p = 0.005). After adjusting for confounding factors, multivariate logistic regression confirmed that the SIRI is an independent factor associated with YCI (OR = 1.692,95% CI:1.045–2.739, p = 0.032). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showed that the optimal cutoff value for the SIRI as a predictor of YCI was 0.83*10^9/L, with corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 77.8 and 50%, respectively. The AUC was 0.643, with a 95%CI of 0.54–0.74 and a p-value of = 0.005. The subgroup analysis results were as follows: (i) There was no statistically significant difference in the SIRI values among the infarct volume groups (p = 0.633). (ii) The SIRI values in the severe stenosis group were higher than those in the non-stenosis and mild-to-moderate stenosis groups (p < 0.001). Binary logistic regression analysis showed that the SIRI was an independent associated factor for severe stenosis (original OR = 3.346,95% CI = 1.761–6.359, p < 0.001; corrected OR = 5.278,95% CI = 2.317–12.022, p < 0.001). (iii) The SIRI values in the large-vessel atherothromboembolic (LAA) group were higher than those in the small-vessel disease (SVD) group (p = 0.003). (iv) There was no statistically significant difference in the SIRI values between the infarct distribution groups (p = 0.572). (v) There was no statistically significant difference in the SIRI values between the vasculopathy groups (p = 0.345).

Conclusion:

The SIRI is independently associated with YCI and is significantly linked to severe intracranial arterial stenosis and the LAA subtype.

Introduction

Although the incidence of ischemic stroke increases with age, it affects a substantial proportion of young individuals, accounting for 10–20% of patients aged 18–45 years. Stroke in young adults is particularly concerning due to its association with a high risk of disability, recurrence, and mortality (1–3), posing a significant socioeconomic burden. The etiology of ischemic stroke in this population is more diverse than in older adults (2). While atherosclerosis remains the most common cause (4), other factors such as immune disorders, infections, and related vascular injuries also play significant roles (5). Inflammation serves as a critical pathological basis for atherosclerosis (6), where specific inflammatory biomarkers and underlying inflammatory processes contribute to plaque rupture and arterial thrombotic events (7).

Recently, the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) has been proposed as a novel, integrated indicator of systemic inflammation. Calculated from neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts, the SIRI is defined by the formula SIRI = neutrophils×monocytes/lymphocytes. It has proven effective in reflecting inflammatory status and predicting the prognosis and risk of various conditions, including sepsis and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (8, 9). Compared to traditional single-parameter inflammatory markers, the SIRI integrates three distinct cellular pathways involved in inflammation and immunity, offering a more comprehensive assessment of the body’s inflammatory state (7, 10).

Evidence suggests that in older hypertensive patients, higher SIRI levels are associated with an increased cumulative incidence of total stroke, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke. Elevated SIRI scores have been significantly linked to overall stroke risk and its subtypes, demonstrating superior predictive value compared to other inflammatory indices, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and systemic immune-inflammatory index (SII) (11).

While the etiology and progression of ischemic stroke in young adults are closely linked to inflammation (12, 13), the specific relationship between the SIRI and young-onset ischemic stroke remains unclear. Furthermore, existing research has primarily focused on older populations, emphasizing the association between the SIRI levels and stroke risk (11). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate SIRI levels in young patients with acute ischemic stroke and explore their correlation with key clinical features, including infarct volume and distribution, intracranial artery stenosis, etiological classification, and types of vascular injury.

Data and methods

Research object

Patients aged 18 to 45 years with first-onset acute cerebral infarction who were hospitalized in the Department of Neurology at the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University from 1 January 2022 to 31 October 2023 were selected as participants for the study. Additionally, non-acute cerebral infarction patients within the same age group and without intracranial atherosclerosis, who were hospitalized during the same period, were selected as control subjects.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age between18 and 45 years, with no restriction on sex; (ii) patients with first-onset acute cerebral infarction within 7 days of symptom onset, meeting the diagnostic criteria of the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke 2018 and presenting neurological localization signs confirmed by cranial CT or cranial MRI examination.

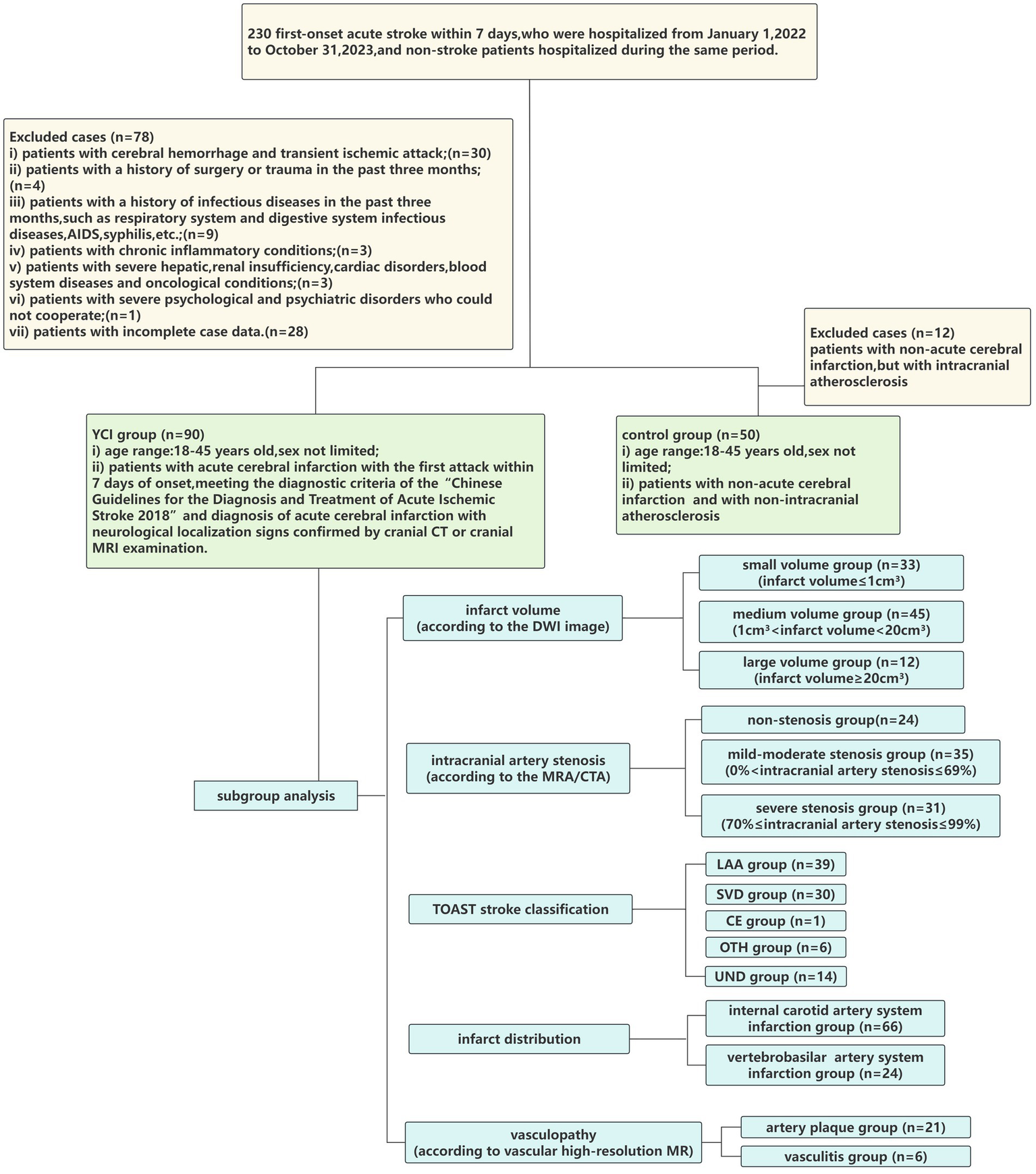

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients with cerebral hemorrhage or transient ischemic attack; (ii) patients with a history of surgery or trauma within the past 3 months; (iii) patients with a history of infectious diseases within the past 3 months, such as respiratory and digestive system infections, AIDS, and syphilis; (iv) patients with chronic inflammatory conditions; (v) patients with severe hepatic, renal insufficiency, cardiac disorders, blood system diseases, or oncological conditions; (vi) patients with severe psychological and psychiatric disorders who could not cooperate; and (vii) patients with incomplete case data. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study cohort.

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (registration number 2024-R663). The data were anonymized; therefore, informed consent was not required. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to present its findings.

Clinical data collection

General patient data, such as name, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking history, and risk factors related to cerebral infarction (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, immune system disease, and sleep disturbances), and imaging data (infarct volume, degree of intracranial artery stenosis, etiological classification, lesion distribution, and vascular high-resolution MR results), were collected.

On the second day after admission, laboratory indicators were collected from the patients, including homocysteine (HCY), uric acid (UA), creatinine (Cr), SIRI, and blood lipid levels (total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and lipoprotein a (Lp-a)). The above blood indicators were measured by the Laboratory Department of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University using fully automated blood cell analyzers and biochemical analyzers.

Grouping and observation projects

The research participants were divided into the youth cerebral infarction (YCI) group and the control group.

YCI group: A total of 90 hospitalized patients who met the inclusion criteria and did not meet any exclusion criteria were included.

Control group: A total of 50 patients of the same age group, hospitalized during the same period, who were confirmed to have no acute cerebral infarction by cranial CT or cranial MRI, had no intracranial arteriosclerosis as confirmed by MRA/CTA, and met none of the exclusion criteria, were included.

Further subgroup analysis was performed on the YCI group. The patients were divided into several subgroups according to infarct volume, intracranial artery stenosis, etiological classification, infarct distribution, and vasculopathy. The subgroup classifications included the following: (i) small-volume group (infarct volume≤1cm3), medium-volume group (1cm3 < infarct volume<20 cm3), and large-volume group (infarct volume≥20cm3) (according to the DWI image, infarct volume was calculated on DWI sequences by a trained radiologist who manually outlined the hyperintense infarct area on each slice. The total infarct volume was then computed by summing the areas across all slices and multiplying by the slice thickness); (ii) the non-stenosis group, the mild-to-moderate stenosis group (0% < intracranial artery stenosis≤69%), and the severe stenosis group (70% ≤ intracranial artery stenosis≤99%) (according to the MRA/CTA/Vascular high-resolution MR results); (iii) the large-vessel atherothromboembolic (LAA) group, cardioembolic (CE) group, small-vessel disease (SVD) group, stroke of other determined etiology (OTH) group, and stroke of undetermined etiology (UND) group (according to the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification); (iv) the internal carotid artery system infarction group and the vertebrobasilar artery system infarction group; and (v) the artery plaque group and vasculitis group (according to the vascular high-resolution MR result).

The baseline characteristics of the YCI group and the control group were analyzed and compared. We used binary logistic regression to evaluate whether the SIRI is independently associated with YCI, and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed. Additionally, the SIRI values were compared across the different subgroups of YCI patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 29.0 software. Continuous variables that conformed to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A t-test was used to compare intergroup differences, and analysis of variance was used to compare differences among multiple groups. Continuous variables that did not conform to a normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range). The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare intergroup differences, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare differences among multiple groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). A chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare intergroup differences. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with acute ischemic stroke in youth. For the logistic regression model, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit of the model, and a p-value of >0.05 indicated a good model fit. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to evaluate multicollinearity among independent variables, and a VIF value of <5 was considered to indicate the absence of serious multicollinearity. The ROC curve was used to evaluate the discriminative capacity of the SIRI for YCI. The optimal test cutoff point was determined by calculating Youden’s index. To evaluate the incremental discriminative value of the SIRI beyond conventional risk factors (age, smoking, hypertension, and HCY), logistic regression models with and without the SIRI were compared using the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) and net reclassification improvement (NRI). All comparisons were two-tailed, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size consideration

As a retrospective case–control study, all eligible patients available during the study period were included, resulting in a sample size of 90 patients in the youth cerebral infarction (YCI) group and 50 in the control group. A post hoc power analysis for the main effect was performed using G*Power version 3.1, applying a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. The analysis revealed an observed statistical power of 90.41% for the association between the SIRI and YCI. In the subgroup analysis of the YCI patients with severe intracranial arterial stenosis, the observed statistical power for the association with the SIRI was 98.53%.

Results

Basic information of the YCI group versus the control group and the results of multivariable logistic regression analysis

Compared to the control group, the YCI group had statistically significant differences in smoking history and hypertension history (p = 0.008 and p = 0.002, respectively), whereas there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding age, sex, BMI, drinking history, diabetes history, hyperlipidemia history, immune system disease history, and sleep disturbances (p = 0.845, p = 0.475, p = 0.62, p = 0.729, p = 0.113, p = 0.841, p = 0.418, and p = 1.000, respectively). HCY and SIRI values were higher (p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively), whereas HDL-C values were lower in the YCI group compared to the control group (p = 0.009). The data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Parameters | YCI group (n = 90) | Control group (n = 50) | t/z/x2 value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.5 (34.75–41) | 38 (33–43) | −0.196 | 0.845 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 73/13 | 38/12 | 0.511 | 0.475 |

| Smoking history (n %) | 42 (46.7) | 12 (24) | 6.97 | 0.008* |

| Drinking history (n %) | 24 (26.7) | 12 (24) | 0.12 | 0.729 |

| Hypertension (n %) | 44 (48.9) | 11 (22) | 9.74 | 0.002* |

| Diabetes (n %) | 16 (17.8) | 4 (8) | 2.51 | 0.113 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n %) | 15 (16.7) | 9 (18) | 0.04 | 0.841 |

| Immune system disease (n %) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (8) | 0.655 | 0.418 |

| Sleep disturbances (n %) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| HCY | 15.71 (11.47–34.32) | 11.04 (8.72–13.03) | –4.895 | <0.001* |

| Cr | 72.22 ± 13.74 | 73.39 ± 11.61 | –0.512 | 0.61 |

| UA | 383.64 ± 110.02 | 356.2 ± 99.33 | 1.463 | 0.15 |

| SIRI | 1.27 (0.85–2.07) | 0.84 (0.61–1.5) | –2.794 | 0.005* |

| TC | 4.51 ± 1.01 | 4.76 ± 0.84 | –1.477 | 0.142 |

| TG | 1.52 (1.16–2.66) | 1.35 (0.94–2.29) | –1.518 | 0.129 |

| HDL-C | 1.04 ± 0.23 | 1.15 ± 0.24 | –2.656 | 0.009* |

| LDL-C | 2.92 ± 0.93 | 3.13 ± 0.74 | –1.406 | 0.162 |

| Lp-a | 10.31 (5.51–28.31) | 10.44 (3.23–21.6) | –0.909 | 0.363 |

| BMI | 26.67 ± 4.02 | 26.32 ± 3.91 | 0.497 | 0.62 |

Comparison of baseline characteristics and laboratory parameters between the YCI group and the control group

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (Q1–Q3) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. *p<0.05 has statistical significance. HCY, homocysteine; Cr, creatinine; UA, uric acid; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; TC, cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp-a, lipoprotein a; BMI, body mass index.

In the comparison between the YCI group and the control group, a p-value of <0.05 was analyzed as a significant univariable. After adjusting for potential confounders (smoking, hypertension, homocysteine, and HDL-C), the multivariate logistic regression model demonstrated that smoking (p = 0.043), hypertension (p = 0.028), homocysteine (p = 0.006), and SIRI (p = 0.032) were independently associated with cerebral infarction in young adults. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Index | B value | Standard error | Wald Chi square value | p value |

OR

(95%CI value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRI | 0.526 | 0.246 | 4.582 | 0.032* | 1.692 (1.045-2.739) |

| HDL-C | 1.821 | 0.943 | 3.731 | 0.053 | 0.162 (0.026-1.027) |

| HCY | 0.064 | 0.023 | 7.510 | 0.006* | 1.066 (1.018-1.116) |

| Smoking History | 0.900 | 0.445 | 4.086 | 0.043* | 2.459 (1.028-5.884) |

| Hypertension | 0.975 | 0.445 | 4.802 | 0.028* | 2.652 (1.109-6.343) |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of SIRI as a predictor of YCI

Data are presented as mean±SD or median(Q1–Q3) for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables. *p<0.05 has statistical significance. SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HCY, homocysteine.

The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated that the model fits well (p = 0.803). Collinearity diagnostics indicated that the model does not have serious multicollinearity issues (the VIF of all independent variables was <5).

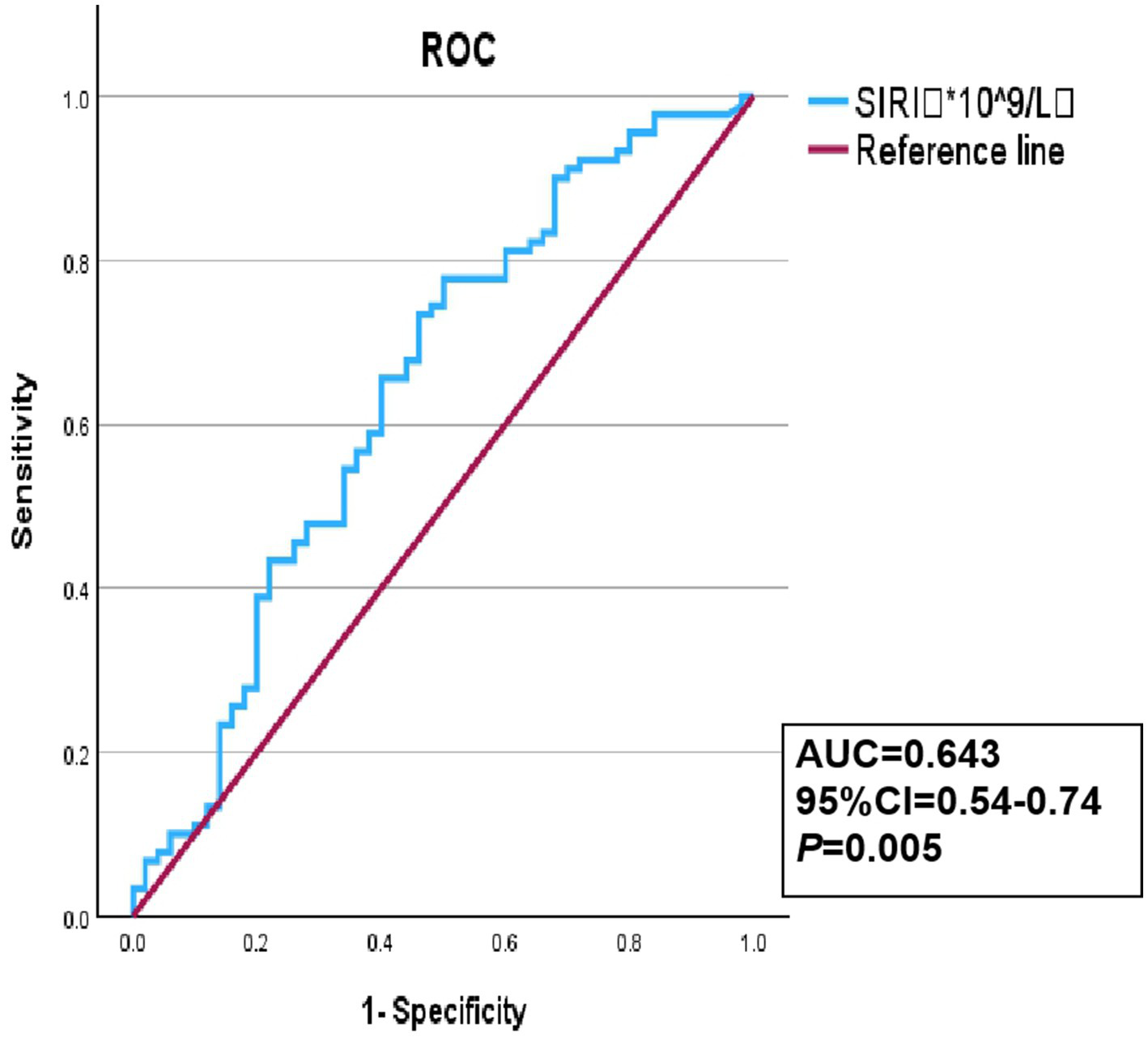

The ROC curve was used to evaluate the discriminative capacity of the SIRI for YCI. The results showed that the optimal cutoff value of the SIRI as a discriminative indicator for YCI was 0.83*10^9/L, with a corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 77.8 and 50%, respectively. The AUC was 0.643, with a 95%CI of 0.54–0.74 and a p-value of 0.005, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the SIRI discriminative ability for YCI.

To evaluate whether the SIRI adds incremental discriminative value beyond established clinical risk factors (age, smoking, hypertension, and HCY), we constructed a baseline clinical model. The AUC of the clinical model was 0.752 (95% CI:0.67–0.83). After adding the SIRI, the AUC increased to 0.768 (95% CI:0.69–0.85). The integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) was 0.021 (p = 0.042), and the net reclassification improvement (NRI) was 0.182 (p = 0.038), indicating a modest but significant improvement in reclassification and discrimination, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Metrics | Traditional model (HCY+Smoke+Hypertension) | Traditional model + SIRI (HCY+Smoke+Hypertension+SIRI) | Improvement | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index (95% CI) | 0.712 | 0.756 | 0.044 (0.005–0.083) | 0.029* |

| NRI (95% CI) | – | – | 0.324 (0.112–0.536) | 0.003* |

| IDI (95% CI) | – | – | 0.048 (0.016–0.080) | 0.003* |

Improvement in predictive performance with addition of SIRI to traditional risk factors.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median(Q1-Q3) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. *p < 0.05 has statistical significance.

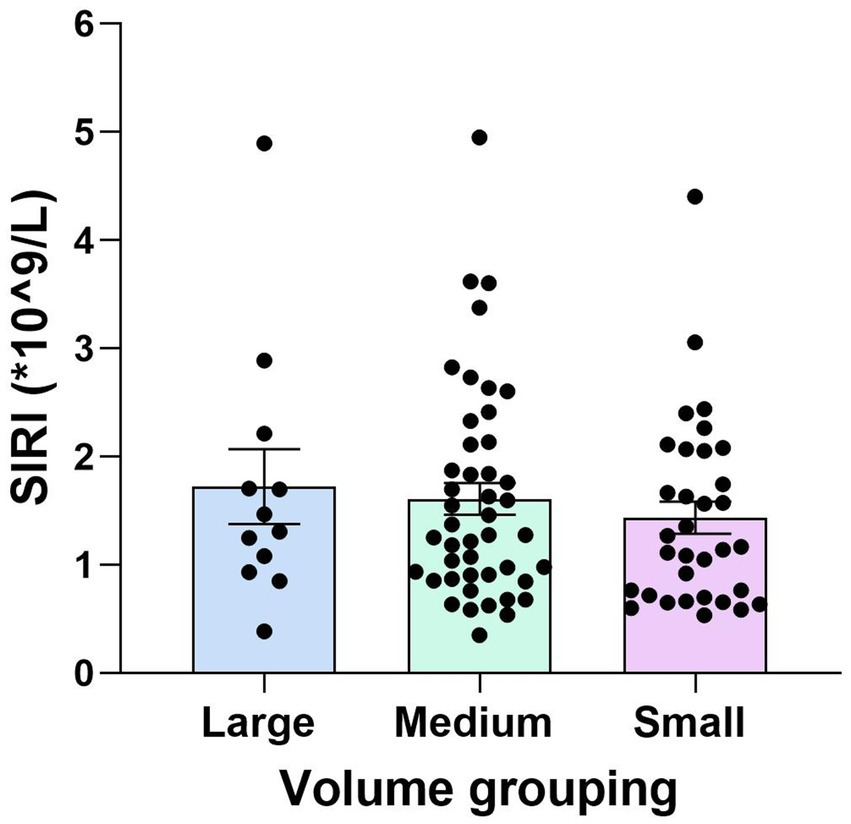

Correlation analysis between SIRI values and infarct volume in YCI patients

Further analysis was performed on the YCI patients. The patients were divided into subgroups based on infarct volume: the large-volume group (12 patients, 13.3%), the medium-volume group (45 patients, 50%), and the small-volume group (33 patients, 36.7%). The SIRI values for the large-volume group were higher than those for the medium-volume group, and the SIRI values for the medium-volume group were higher than those for the small-volume group. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the three groups (p = 0.633), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Comparison of the SIRI values among the large-, medium-, and small-volume groups in YCI. There was no statistically significant difference in the SIRI values among all the different volume groups (p = 0.633).

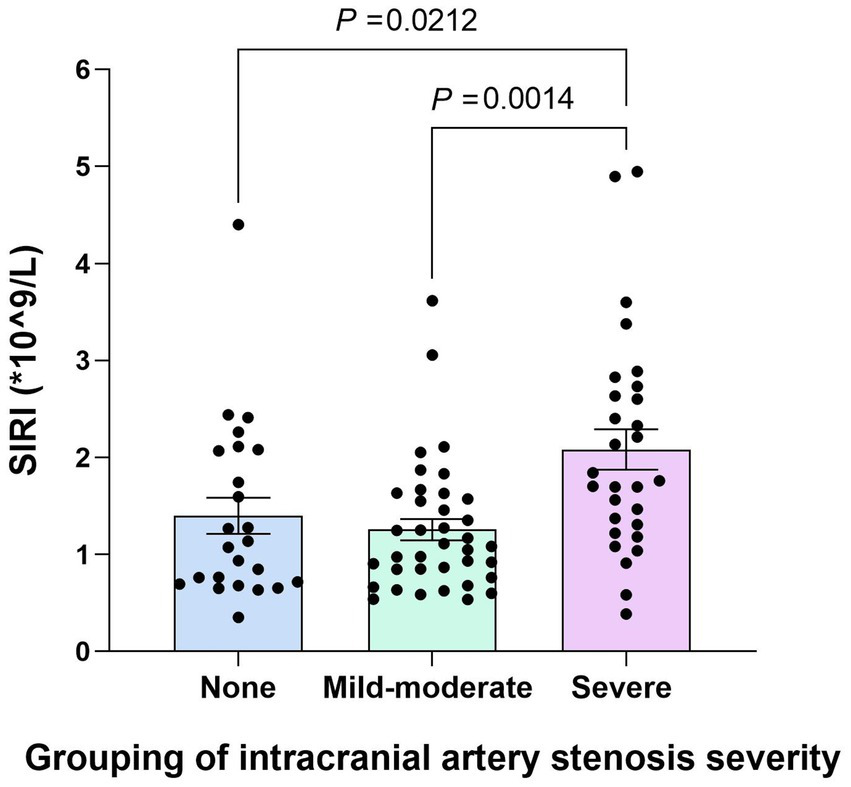

Correlation analysis between SIRI values and intracranial arterial stenosis in YCI patients

The subgroups of the YCI patients according to intracranial arterial stenosis were as follows: the non-stenosis group (24 patients, 26.7%), the mild-to-moderate stenosis group (35 patients, 38.9%), and the severe stenosis group (31 patients, 34.4%). The SIRI values in the severe stenosis group were higher than those in the non-stenosis and mild-to-moderate stenosis groups (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001), and there was no statistically significant difference between the non-stenosis group and the mild-to-moderate stenosis group (p = 0.385), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Comparison of the SIRI values among the non-stenosis group, the mild-to-moderate stenosis group, and the severe stenosis group. The SIRI values in the severe stenosis group were higher than those in the non-stenosis and mild–moderate stenosis groups (p < 0.001), and there was no statistically significant difference between the non-stenosis group and the mild–moderate stenosis group (p = 0.385).

Further analysis was conducted to assess whether the SIRI was independently associated with severe stenosis. The non-stenosis group and the mild-to-moderate stenosis group were combined into a single group called the non-severe stenosis group and compared with the severe stenosis group. The SIRI values in the severe stenosis group were higher than those in the non-severe stenosis group (p < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding factors, such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and HCY, multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that the SIRI was independently associated with severe stenosis (original OR = 3.346, 95% CI = 1.761–6.359, p < 0.001; corrected OR = 5.278, 95% CI = 2.317–12.022, p < 0.001). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated that the model fits well (p = 0.805). Collinearity diagnostics indicated that the model does not have serious multicollinearity issues (the VIF of all independent variables was <5), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4

| Index | Original OR (95% CI) | p value | Correction OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRI | 3.346 (1.761–6.359) | <0.001* | 5.278 (2.317–12.022) | <0.001* |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of SIRI as a risk factor for severe stenosis of intracranial arteries.

*Data are presented as mean±SD or median(Q1-Q3) for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables. p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences.

SIRI, Systemic inflammatory response index.

Correlation analysis between SIRI values and the TOAST classification in YCI patients

The YCI patients were divided into subgroups according to the TOAST classification. There were 39 patients (43.3%)in the LAA group, 30 patients (33.3%)in the SVD group,1 patient (1.1%) in the CE group,6 patients (6.7%) in the OTH group, and 14 patients (15.6%) in the UND group. The CE group, OTH group, and UND group were not statistically analyzed due to the small number of cases. The SIRI values in the LAA group were higher than those in the SVD group (p = 0.03), as shown in Table 5.

Table 5

| Group | n | SIRI (*10^9/L) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAA group | 39 | 1.63(1.04-2.40) | 0.03* |

| SVD group | 30 | 1.12(0.69-1.82) |

Comparison of SIRI values and etiological classification

Data are presented as mean±SD or median(Q1-Q3) for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables. *p < 0.05 has statistical significance. SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Correlation analysis between SIRI values and infarct distribution in YCI patients

The YCI patients were grouped based on infarct distribution in either the internal carotid artery system or the vertebrobasilar artery system. There were 66 patients (73.3%) in the internal carotid artery system infarction group and 24 patients (26.7%) in the vertebrobasilar artery system infarction group. There was no statistically significant difference in the SIRI values between the different infarct distribution groups (p = 0.572), as shown in Table 6.

Table 6

| Group | n | SIRI (*10^9/L) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal carotid artery system infarction group | 66 | 1.33 (0.90–1.92) | 0.572 |

| Vertebrobasilar artery system infarction group | 24 | 1.15 (0.67–2.11) |

Comparison of SIRI values and lesion distribution.

Data are presented as mean±SD or median(Q1-Q3) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. There is no statistically significant difference when p > 0.05. SIRI, Systemic inflammatory response index.

Correlation analysis between SIRI values and vasculopathy in YCI

A total of 27 patients in the YCI group underwent vascular high-resolution MR, and the vascular damage types were used as the basis for subgrouping. There were 21 patients (77.8%) in the arterial plaque group and 6 patients (22.2%) in the vasculitis group. The SIRI levels in the arterial plaque group were higher than those in the vasculitis group. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.345), as shown in Table 7.

Table 7

| Group | n | SIRI (*10^9/L) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial plaque group | 21 | 1.25 (0.89–1.84) | 0.345 |

| Vasculitis group | 6 | 0.92 (0.73–2.03) |

Comparison of SIRI values and vasculopathy.

Data are presented as mean±SD or median(Q1-Q3) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. There is no statistically significant difference when p > 0.05. SIRI, Systemic inflammatory response index.

Discussion

Inflammatory biomarkers have received increasing attention in recent years. As inflammatory indicators, the NLR, PLR, LMR, and red blood cell distribution width (RDW) have all been reported to predict stroke prognosis (14–16). The SIRI is an emerging inflammatory marker that is a more comprehensive chronic low-grade inflammation marker based on monocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts. It has been proven to effectively reflect the inflammatory state and predict the prognosis of many diseases, such as cancer and coronary artery disease (17–22). The majority of previous studies have shown that the SIRI is associated with the severity, prognosis, and related complications of ischemic stroke (23–25). Another study showed that the SIRI can predict the functional status of patients with critical acute ischemic stroke at discharge (26). In addition, studies have explored the relationship between dyslipidemia, PLR, and ischemic stroke in young adults (3, 4). However, research on the relationship between the SIRI and acute ischemic stroke in young people is still lacking. This study investigated the SIRI in YCI and its correlations with infarct volume, lesion distribution, intracranial arterial stenosis, etiological subtypes, and the nature of vascular pathology. Our findings revealed significantly elevated SIRI levels in these patients. Even after adjusting for confounding factors such as smoking, hypertension, and homocysteine levels, the SIRI remained an independent correlated factor of YCI, suggesting it is a significant associated factor. Furthermore, the SIRI demonstrated utility in distinguishing between the large-artery atherosclerosis and small-artery occlusion subtypes. A high SIRI level was also indicative of a greater likelihood of severe intracranial arterial stenosis.

The link between the SIRI and YCI may stem from both the acute-phase inflammation post-infarction and the chronic inflammation associated with conditions such as atherosclerosis. Therefore, the SIRI serves as an integrated measure of this total inflammatory burden.

The acute phase of cerebral infarction involves key pathological processes including blood–brain barrier disruption, oxidative stress, and inflammation (27). The inflammatory cascade, orchestrated by complex interactions among various cells, plays a pivotal role in influencing infarct progression, resolution, and subsequent tissue repair and remodeling (28). Cerebral infarction triggers the release of inflammatory mediators from injured brain tissue, leading to the systemic release of neutrophils/monocytes and lymphocyte apoptosis/dysfunction. The infiltrating myeloid cells initiate a neuroinflammatory cascade within the brain, increasing capillary permeability and promoting thrombosis. Meanwhile, the loss of lymphocyte function results in impaired immune defense and overall immune imbalance (29). The SIRI is a composite index derived from neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts (SIRI = neutrophils*monocytes/lymphocytes) (10). This integrative nature of the immune response directly explains the elevated serum SIRI levels observed in the young patients with cerebral infarction.

The independent association between the SIRI and YCI indicates that the systemic inflammatory response, as revealed by the SIRI, constitutes an important component of the pathophysiology of this condition. The ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the SIRI possesses a certain discriminative ability to distinguish young individuals with acute cerebral infarction from those without infarction. Its relatively high sensitivity suggests that SIRI can effectively identify the majority of YCI patients, particularly those with an inflammatory component. Consequently, in clinical practice, an abnormally elevated SIRI value could be regarded as a “warning signal,” indicating the need for more comprehensive cerebrovascular assessment and inflammatory risk management. The moderate specificity of the SIRI in distinguishing YCI may be attributed to its nature as a non-specific systemic inflammatory marker. Elevated SIRI levels could result from mild, subclinical inflammatory conditions that are common among young adults, which are difficult to completely exclude despite strict study criteria. Furthermore, the etiology of stroke in young adults is highly heterogeneous; not all cases are strongly linked to systemic inflammation, which also affects the specificity of the SIRI.

However, after adding the SIRI to the traditional clinical model (including smoking, hypertension, and homocysteine), improvements in the C-index, NRI, and IDI were observed. This underscores the value of the SIRI as a discriminative indicator. The SIRI captures an independent aspect of disease pathophysiology, the inflammatory response, which cannot be fully reflected by homocysteine, smoking, or hypertension alone. Future prospective, longitudinal studies that measure the SIRI in healthy populations and track their stroke outcomes are warranted to clarify its potential as a true predictive risk factor.

Chronic systemic inflammation mediates the development of atherosclerosis, which is itself a major cause of cerebral infarction (30, 31).In the progression of atherosclerosis, neutrophils amplify inflammatory responses and induce endothelial injury through the release of reactive oxygen species and neutrophil extracellular traps; monocytes, as precursors of macrophages, infiltrate the vascular wall and engulf lipids to form foam cells, constituting the core of atherosclerotic plaques; and lymphocyte apoptosis impairs protective immunoregulatory capacity, thereby exacerbating inflammatory damage (32). Studies have shown that patients with carotid plaques exhibit higher serum SIRI levels, indicating that the SIRI holds predictive or indirect assessment value for atherosclerosis (31). This conclusion is consistent with the findings of the present study. Therefore, the SIRI reflects the inflammatory burden that promotes atherosclerosis. This mechanism explains why YCI patients with the large-artery atherosclerosis subtype exhibited higher SIRI levels and why the SIRI emerged as an independent correlate of severe intracranial arterial stenosis. The clinical relevance of our finding lies in the close association between the SIRI and a specific subtype of YCI, which may help identify patients with more intense inflammation and a greater atherosclerotic burden. In practice, the SIRI could assist clinicians in rapidly recognizing patients who might benefit from aggressive anti-inflammatory and lipid-lowering therapy.

However, it should be noted that the comparison between LAA and SVD was conducted in a subset of participants, in which the CE, OTH, and UND subtypes were not statistically analyzed due to the small number of cases. Therefore, although the finding is statistically significant and biologically plausible, it should be regarded as exploratory and warrants further validation in larger cohorts that encompass all etiological subtypes.

Currently, there are no reports on the correlation between the SIRI and infarct volume/distribution/vascular damage type. We found that the SIRI showed no statistically significant differences with cerebral infarction volume, anterior and posterior circulation infarction distribution, or artery plaques and vasculitis. The reasons may be as follows: (i) The SIRI reflects the inflammatory status of the body but has no specificity for certain types of vessel damage. (ii) Due to the small sample size of the infarct volume group and the vascular lesion group, the lack of statistical difference in the SIRI values between these two subgroups cannot be interpreted as having no association; it may instead reflect insufficient sample size to detect an association. Therefore, it should not be regarded as a definitive negative result or no biological association. The original intention behind conducting this analysis was to utilize these valuable data for a preliminary exploratory study, representing initial results. Future research should expand the sample size for verification. Therefore, further studies are needed to improve and explore the SIRI in YCI.

Limitations and future directions

This study has some limitations. First, although multifactorial adjustments were made, there were still unmeasurable confounders, such as diet, genetics, socioeconomic status, and the use of anti-inflammatory medications. Future research employing methods less susceptible to confounding—such as Mendelian randomization studies to assess causality or prospective cohorts designed to comprehensively collect data on complex lifestyle and environmental factors—is crucial to validate and extend our findings. Second, only the baseline level of the SIRI was calculated, and the impact of dynamic changes in the SIRI on YCI was not observed. Therefore, it is unclear whether the variation in SIRI over time will affect its value, warranting further study in the future. Third, this study was a single-center retrospective study. Although we implemented strict standards and rigorous statistical adjustments, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by selection bias and the characteristics of the local patient population. These findings should be validated using large, multicenter prospective cohorts to ensure their reliability and applicability. Finally, while our sample size demonstrates sufficient statistical power for the primary association, it remains relatively limited, particularly for the subgroup analyses (such as volumetric groups and vasculopathy types). The negative findings in these subgroups should be interpreted with caution, as they may stem from limited statistical power rather than a true absence of association, and are best considered exploratory. Larger-scale longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the predictive value of the SIRI in stroke risk assessment over time.

Conclusion

Our retrospective study demonstrated that an elevated SIRI level is an independent correlate of acute ischemic stroke in young adults. Strikingly, the SIRI was specifically linked to severe intracranial arterial stenosis and the large-artery atherosclerotic subtype, indicating its clinical utility in pinpointing patients with more pronounced inflammatory atherosclerosis. These findings underscore the potential of the SIRI and emphasize the need for confirmation through future large-scale prospective studies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Registration number: 2024-R663). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HQ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. PW: Writing – review & editing, Validation. YG: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing, Software. HA: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. WG: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YatW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YaW: Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. YY: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Construction of Provincial Excellent Characteristic Disciplines of Hebei Medical University (grant no. 2022LCTD-B22), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province, the Precision Medicine Joint Fund Cultivation Project (grant no. H2022206305), and the Geriatric Disease Prevention Project of Hebei Province (grant no. 361004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Xinying W Zhilei K Yongchao W Yuelin Z Yan W . Application of prognostic nutritional index in the predicting of prognosis in young adults with acute ischemic stroke. World Neurosurg. (2023) 178:e292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.07.045

2.

Xia Y Liu H Zhu R . Risk factors for stroke recurrence in young patients with first-ever ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. (2023) 11:6122–31. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6122

3.

Wen H Wang N Lv M Yang Y Liu H . The early predictive value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio to hemorrhagic transformation of young acute ischemic stroke. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News). (2023) 17:267–72. doi: 10.2478/abm-2023-0069

4.

Ciplak S Adiguzel A Deniz YZ Aba M Ozturk U . The role of the low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as an atherogenic risk factor in young adults with ischemic stroke: a case—control study. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1180. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13081180

5.

Editorial OOAB . The value of platelet/lymphocyte ratio in young patient with acute ischemic stroke. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News). (2023) 17:249. doi: 10.2478/abm-2023-0067

6.

Xu Q Wu Q Chen L Li H Tian X Xia X et al . Monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio predicts clinical outcomes after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2023) 29:1953–64. doi: 10.1111/cns.14152

7.

Zhou Y Zhang Y Cui M Zhang Y Shang X . Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Brain Behav. (2022) 12:e2619. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2619

8.

Xu T Song S Zhu K Yang Y Wu C Wang N et al . Systemic inflammatory response index improves prognostic predictive value in intensive care unit patients with sepsis. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:1908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-81860-7

9.

Shen D Cai X Hu J Song S Zhu Q Ma H et al . Inflammatory indices and mafld prevalence in hypertensive patients: a large-scale cross-sectional analysis from China. J Inflamm Res. (2025) 18:1623–38. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S503648

10.

Huang YW Zhang Y Feng C An YH Li ZP Yin XS . Systemic inflammation response index as a clinical outcome evaluating tool and prognostic indicator for hospitalized stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. (2023) 28:474. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01446-3

11.

Cai X Song S Hu J Wang L Shen D Zhu Q et al . Systemic inflammation response index as a predictor of stroke risk in elderly patients with hypertension: a cohort study. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:4821–32. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S433190

12.

Liu J Yuan J Zhao J Zhang L Wang Q Wang G . Serum metabolomic patterns in young patients with ischemic stroke: a case study. Metabolomics. (2021) 17:24. doi: 10.1007/s11306-021-01774-7

13.

Fullerton HJ DeVeber GA Hills NK Dowling MM Fox CK Mackay MT et al . Inflammatory biomarkers in childhood arterial ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2016) 47:2221–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013719

14.

Gong P Liu Y Gong Y Chen G Zhang X Wang S et al . The association of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio with post-thrombolysis early neurological outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:51. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02090-6

15.

Fakhari MS Poorsaadat L Almasi-Hashiani A Ebrahimi-Monfared M . Inflammatory markers and functional outcome score in different subgroups of ischaemic stroke: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Neurol Open. (2024) 6:e556. doi: 10.1136/bmjno-2023-000556

16.

Ke L Zhang H Long K Peng Z Huang Y Ma X et al . Risk factors and prediction models for recurrent acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective analysis. PeerJ. (2024) 12:e18605. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18605

17.

Chen L Chen Y Zhang L Xue Y Zhang S Li X et al . In gastric cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy systemic inflammation response index is a useful prognostic indicator. Pathol Oncol Res. (2021) 27:811. doi: 10.3389/pore.2021.1609811

18.

Kamposioras K Papaxoinis G Dawood M Appleyard J Collinson F Lamarca A et al . Markers of tumor inflammation as prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving first-line folfirinox chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. (2022) 61:351. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.19547351.v1

19.

Wang TC An TZ Li JX Pang PF . Systemic inflammation response index is a prognostic risk factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing tace. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. (2021) 14:2589–600. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S316740

20.

Urbanowicz T Michalak M Komosa A Olasinska-Wisniewska A Filipiak KJ Tykarski A et al . Predictive value of systemic inflammatory response index (siri) for complex coronary artery disease occurrence in patients presenting with angina equivalent symptoms. Cardiol J. (2023) 31:583–95. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2023.0033

21.

Li Q Ma X Shao Q Yang Z Wang Y Gao F et al . Prognostic impact of multiple lymphocyte-based inflammatory indices in acute coronary syndrome patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.811790

22.

Li J He D Yu J Chen S Wu Q Cheng Z et al . Dynamic status of sii and siri alters the risk of cardiovascular diseases: evidence from kailuan cohort study. J Inflamm Res. (2022) 15:5945–57. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S378309

23.

Zhang Y Xing Z Zhou K Jiang S . The predictive role of systemic inflammation response index (siri) in the prognosis of stroke patients. Clin Interv Aging. (2021) 16:1997–2007. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S339221

24.

Li J Luo H Chen Y Wu B Han M Jia W et al . Comparison of the predictive value of inflammatory biomarkers for the risk of stroke-associated pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clin Interv Aging. (2023) 18:1477–90. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S425393

25.

Zhu F Wang Z Song J Ji Y . Correlation analysis of inflammatory markers with the short-term prognosis of acute ischaemic stroke. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:17772. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66279-4

26.

Arslan K Sahin AS . Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index and systemic inflammatory response index on functional status and mortality in patients with critical acute ischemic stroke. Tohoku J Exp Med. (2025) 265:91–7. doi: 10.1620/tjem.2024.J094

27.

Chu M Luo Y Wang D Liu Y Wang D Wang Y et al . Systemic inflammation response index predicts 3-month outcome in patients with mild acute ischemic stroke receiving intravenous thrombolysis. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1095668. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1095668

28.

Zhang YX Shen ZY Jia YC Guo X Guo XS Xing Y et al . The association of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and systemic inflammation response index with short-term functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:3619–30. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S418106

29.

Lattanzi S Norata D Divani AA Di Napoli M Broggi S Rocchi C et al . Systemic inflammatory response index and futile recanalization in patients with ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular treatment. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:1164. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11091164

30.

Wu X Huang L Huang Z Lu L Luo B Cai W et al . The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis plaque instability. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:915216. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.915126

31.

Chen Q Che M Shen W Shao L Yu H Zhou J . Comparison of the early warning effects of novel inflammatory markers siri, nlr, and lmr in the inhibition of carotid atherosclerosis by testosterone in middle-aged and elderly han chinese men in the real world: a small sample clinical observational study. Am J Mens Health. (2023) 17:1106350686. doi: 10.1177/15579883231171462

32.

Wang CJ Pang CY Huan Y Cheng YF Wang H Deng BB et al . Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio affects prognosis in laa-type stroke patients. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e10948. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10948

Summary

Keywords

inflammation, infarct volume, systemic inflammatory response index, youth acute ischemic stroke, intracranial artery stenosis

Citation

Wang H, Qiao H, Zhang X, Wu P, Gao Y, Liu X, An H, Ge W, Song M, Wang Y, Wen Y and Yang Y (2025) Association between the systemic inflammatory response index and acute ischemic stroke in young people. Front. Neurol. 16:1644963. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1644963

Received

07 July 2025

Accepted

21 October 2025

Published

19 November 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Xintian Cai, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Peng Ren, Shandong Provincial Hospital, China

Shuaiwei Song, Tongji University, China

Ökkeş Zortuk, TC Saglik Bakanligi Bandirma Egitim ve Arastirma Hastanesi, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wang, Qiao, Zhang, Wu, Gao, Liu, An, Ge, Song, Wang, Wen and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Yang, vpnyx@hebmu.edu.cn; Ya Wen, wenya2046@hebmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.