Abstract

Objective:

Acoustic neuroma (AN), or vestibular schwannoma, is a benign tumor of the eighth cranial nerve. Radiotherapy is a key treatment modality. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluate post-radiotherapy hearing preservation in patients with AN.

Methods:

Following PRISMA guidelines, 36 studies published from 2011 to 2020 were identified through searches in PubMed, Cochrane, and Semantic Scholar. Data from 3,903 patients were analyzed using RevMan 5.3. Random-effects models were applied to account for heterogeneity.

Results:

The pooled hearing preservation rate post-radiotherapy was 55.9%. Gamma Knife and single-session protocols were associated with higher preservation rates. Male sex was linked to a significantly higher risk of hearing loss (RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.69–0.99). Tumor control was achieved in the majority of cases (RR = 2.95, 95% CI: 1.94–4.29). Hearing preservation declined with longer follow-up durations. Secondary outcomes included tinnitus, imbalance, and facial nerve dysfunction.

Conclusion:

Radiotherapy offers favorable tumor control with variable hearing preservation, influenced by treatment modality, sex, and follow-up duration. These findings inform patient counseling and support the need for standardized outcome measures in future studies.

Introduction

Acoustic neuroma (AN) is a benign tumor of the eighth cranial nerve. Its origin is from the nerve sheath of the eighth cranial nerve. It affects one person per 1,00,00 in a year (Overview: Johns Hopkins Medicine) (1). They are basically tumors of Schwann cells (1). The cancer may exert pressure on the nerve, leading to hearing loss and imbalance. Mainly, they are either unilateral or sporadic (1). Acoustic neuroma (AN) is also known as Vestibular schwannoma (VS). A defect in the neurofibromin two gene on chromosome 22 leads to neurofibromatosis type 2, which may lead to AN. At present, this condition is managed by conservative therapy, microsurgery, or radiotherapy, depending upon the condition (2). Many studies have been conducted to develop effective management strategies for AN, focusing on the three mechanisms of treatment; however, very few of these studies are randomized controlled trials (2). Almost all the studies have the primary outcome as control of tumor size, where the main secondary outcomes are hearing loss/preservation, function of facial nerves, and quality of life of the patients. A rate of hearing preservation is of utmost importance (2).

Conventional therapy and microsurgery are most commonly used for the management of AN. However, when the size of the tumor does not shrink enough with these techniques, the clinician or the oncologist has to resort to radiotherapy (3). Radiotherapy is suggested based on the symptoms, shape, and size of the tumor, age, and other health issues (4). Three types of radiation therapy are basically used: stereotactic surgery, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) (5). The cobalt radiation-based stereotactic device later came to be known as the Gamma Knife. The familiar sources of radiation used are the cobalt-60 source (Gamma Knife) and proton beam therapy (less commonly used) (6). High-energy X-ray radiation is used by LINAC (Linear accelerator). In radiotherapy, radiation dose is given in a single dose more often (7). In fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy, doses of 2 Gy or less are administered multiple times over a few weeks (8). Generally, five or fewer sessions of radiotherapy are considered as multi-session radiosurgery (9).

There are numerous studies on radiotherapy for AN, but very few of them report the hearing outcomes or results of their studies (8). They do not use audiometric-based methods even if hearing results are reported. The two widely used methods for audiometric assessment are the Gardner–Robertson scale and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) (1995) (10). Some clinicians also use the Pure tone average (PTA) of 50 dB or less (50/50 rule) or the Speech Discrimination Score (SDS) (11). Use of any one scare is of utmost importance in the study. Recently, the AAO-HNS system has been widely used since it introduced a novel scatter-based diagram to provide proper resolution of hearing outcomes (12).

One of the major lacunae in the present literature on otolaryngology is that many good studies are not homogeneous in the use of radiation technique and their outcomes (13). Due to this reason, the rates of hearing preservation widely vary (13). This review article and meta-analysis aim at scrutinizing the present literature on radiotherapy for Acoustic Neuroma with special emphasis on the preservation of hearing after the treatment. This would help the clinicians in decision-making for the management of AN (13). This review adds to the existing literature by including studies published between 2018 and 2020, thereby capturing more recent clinical evidence and expanding the total patient population analyzed. In addition, it presents a sex-specific risk analysis for hearing outcomes—an area not quantitatively explored in earlier meta-analyses such as that by Coughlin et al. (1). The study also introduces subgroup analyses based on radiotherapy type, dose fractionation, and follow-up duration, offering new insight into the factors contributing to variability in hearing preservation rates.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study was performed in the form of a systematic review and meta-analysis of hearing preservation after radiotherapy for AN. This study was performed according to the guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis). The complete electronic search strategy, including Boolean operators, exact search strings, databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science), and the date of last update (December 31, 2020), is provided in Supplementary Appendix S2 to ensure reproducibility. The methodical stages of conducting this systematic review were: (1) formulation of review question, (2) defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, (3) development of search strategy and locating studies, (4) selection of studies, (5) data extraction, (6) assessing study quality, (7) analyzing and interpreting results, and (8) disseminating findings 6. A formal quality assessment of the included studies was conducted using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies. Each article was evaluated across three domains: selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of the outcome of interest. Based on the NOS scoring system, studies were categorized as high (7–9 points), moderate (4–6 points), or low (<4 points) quality. This assessment enabled a structured evaluation of the potential risk of bias within individual studies. The NOS ratings for each study are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Literature search

An extensive literature search on databases like PubMed, Cochrane, and Semantic Scholar was conducted for articles on the preservation of hearing post-radiotherapy for acoustic neuroma. The studies published from 2011 to 2020 were screened for relevance. The keywords or MeSH words used were Acoustic Neuroma, Vestibular Schwannoma, hearing, hearing preservation, Gamma Knife linear accelerator radiotherapy, radiosurgery, etc. Only full-text articles fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected. Two reviewers independently screened the selected articles. Duplications were removed. The bibliography of the selected articles was manually screened for any missing relevant articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) complete articles from journals, (2) articles which report rates of hearing preservation before and after radiotherapy with either audiograms or audiogram-based scoring systems, (3) patients with tumorous acoustic neuroma or vestibular schwannoma, (4) well recorded follow up time, (5) published in between 2011 to 2020, and (6) articles that have reported the use of Gamma Knife or linear accelerator radiotherapy. Exclusion criteria: (1) review articles, editorials, or opinion, (2) case report or case series with less than five patients, (3) insufficient audiometric data, (4) unclear follow-up time, (5) patient group in which more than 10% of patients have neurofibromatosis type 2, (6) study population in which more than 10% of patients underwent treatment earlier, (7) duplications of datasets, (8) articles in which proton beam therapy have been used, and (9) published in language other than English.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers scrutinized the selected articles, and any differences were settled through discussion, leading to consensus. “PreservedClass A/B, 1/2 hearing” was defined as either PTA less than or equal to 50 dB and SDS more than or equal to 50%, AAO-HNS Hearing Class A or B, or Gardner–Robertson Grade I or II. Data were extracted from the articles on authors, year of publication, place of original study, sample size, tumor size, and technique, follow-up time, Class A/B, ½ hearing size, hearing preservation, number of patients with NF2, number of patients with previous surgery, and fractionation. Exact hearing loss data were retrieved from Kaplan–Meier curves. In articles where individual patient data is not revealed, aggregate data is used. Hearing preservation rate was defined as the ratio of patients with preserved hearing (Class A/B, ½ hearing) after treatment (at the time of last follow-up) to that before treatment. Time-based hearing preservation rates (specific follow-up intervals) were also recorded if mentioned in the articles.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the present study is whether the tumor can be controlled or not. Secondary outcomes include cranial neuropathies, encompassing both audiovestibular functions and facial nerve function, as well as the quality of life of the patients.

Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.3 analysis software1 was used for conducting the meta-analysis (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Data related to the RR from various studies were estimated using the Mantel–Haenszel method. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were computed by using the fixed-effect model. The proportion of variability that is attributed to heterogeneity was assessed via Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 statistics. All meta-analyses exhibiting moderate to high heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) were reanalyzed using random-effects models to ensure statistical validity. Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the potential sources of heterogeneity. These included comparisons between Gamma Knife and LINAC modalities, single-session versus fractionated radiotherapy, and follow-up duration (<60 months vs. ≥ 60 months). Studies using Gamma Knife demonstrated higher pooled hearing preservation rates (RR = 31.45, 95% CI: 26.52–37.28, I2 = 72%) compared to those using LINAC (RR = 25.13, 95% CI: 20.64–30.58, I2 = 68%). Similarly, single-session treatments were associated with greater hearing preservation (RR = 32.05, 95% CI: 27.44–37.41) than fractionated protocols (RR = 23.87, 95% CI: 19.02–29.95). Shorter follow-up duration correlated with higher hearing preservation (RR = 34.11, 95% CI: 29.45–39.50) compared to longer follow-up periods (RR = 21.76, 95% CI: 18.15–26.09). Due to inconsistent reporting of continuous covariates across studies, meta-regression was not conducted. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were strengthened by excluding influential studies and re-estimating pooled effect sizes, particularly for the Class A/B hearing outcome, which showed improved consistency after outlier removal. This approach was applied to Class A/B hearing preservation (I2 = 96%), sex-based risk (I2 = 70%), tumor control rate (I2 = 70%), and hearing preservation rate (I2 = 97%). Fixed-effect models were used only where heterogeneity was low (I2 ≤ 50%). Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals were computed using the Mantel–Haenszel method. Funnel plots were employed for the detection of publication bias, and bias is revealed if the plots are asymmetrical. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the robustness of the meta-analysis by removing outliers from the analyses with publication bias.

Results

Characteristics of studies

A condensed summary of the included studies, highlighting essential variables such as author, year of publication, sample size, radiotherapy technique, and reported hearing preservation rate. Full methodological and clinical details, including tumor size, fractionation, marginal dose, and secondary outcomes, are provided in Supplementary Table S1 for reference. A total of 1,328 articles were obtained after an electronic search through databases (PubMed, Cochrane) by the use of relevant keywords, in the last decade (2011–2020). Apart from this, 77 other articles were identified from different sources, such as the bibliography of relevant articles. Therefore, a total of 1,405 articles were then screened for duplication. Seven hundred thirty-three articles were removed from the list due to duplications, after which we were left with 672 articles. Out of 672, 560 articles were removed owing to irrelevance (n = 335), presentations (n = 32), and other diseases (n = 193). After excluding these articles that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, 112 were left for inclusion. Out of 112 articles, only 52 were full-text and were further selected.

Furthermore, review case series (n = 3), articles with patients suffering from NF2 (n = 3), articles with proton beam therapy (n = 2), patients with earlier treatment (n = 2), and unclear follow-up treatment (n = 5). The whole screening process is summarized in Figure 1. Finally, after all these exclusions, 36 articles that met all the criteria for inclusion into this study were considered for data extraction and further analysis. The published articles were from almost all continents of the world. The majority of the studies were single-institution retrospective studies. Many of them were retrospective studies of prospectively conducted studies, and the data were extracted from the databases of the institution. No reviews were included. In the 36 articles contained in this review, data of 3,903 patients suffering from acoustic neuroma have been analyzed for their rates of improvement in hearing preservation rates after radiotherapy (Table 1 summarizes key study characteristics).

Figure 1

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1

| Article | Year | Place | Sample size | Gender | Age | Tumor size (before/after) | Technique | Follow up (months) | Class A/B, 1/2 hearing size | Hearing preservation rate (%) (before/after) | Fractionation | Marginal dose | Secondary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anselmo et al. (33) | 2020 | Italy | 48 | M24, F24 | 61.5 median, (23–83 yrs) | Before-1.7 cm3; after-Transient enlargement (median 3 mm, range 2–4 mm), median tumor size 12 mm (range 5.1–21 mm) | LINAC | 12 years | Not mentioned | Before—hearing loss 92% patients, 52% non serviceable hearing; after—serviceable hearing 91% preservation in 10 years | Single | 16.5 Gy median, (13–20 Gy) | No increase, two patients had trigeminal neuralgia, one patient had an imbalance and gait due to hydrocephalus, four patients had incomplete and intermittent ipsilateral facial nerve palsy, two patients had a secondary tumor, and one patient had a thalamic stroke. |

| Franchella et al. (19) | 2019 | Italy | 19 | M13, F6 | 47 ± 10.4 years mean | ≤1 cm; After not mentioned | LINAC | 20.5 | 13 | Before – PTA (20 dB mean)(range 10–39); after PTA 40 dB (range 18–85 dB), Hearing Preservation Surgery success rate range 87–69% | Not mentioned | Not mentioned, since it is a comparison between different hearing preservation surgeries only. | Not mentioned |

| Tucker et al. (16) | 2019 | California | 117 (52 for analysis) | n = 52 (M27, F25) | 63.7 yrs. mean (range 19.4–84.2 years) | before 17.3 mm(range 5.0–29.0 mm); median treated volume of 0.82 cm3 (range 0.03–10.0 cm3); 100% COVERAGE | GKS | 69 | Not reported | Only hearing loss is reported. 9 patients (17.3%) worsened ipsilateral hearing, and three patients (5.8%) had complete ipsilateral hearing. | Single | 12.50 Gy (range 12–16 Gy) | Worsened Balance/Ataxia 7.69%, Diminished Hearing 11.54%, Edema 1.92%, Headache 3.85%, Hydrocephalous 1.92%, Total Hearing Loss 5.77%, Radiation Necrosis 0.0%, Seizure 0.00%, Craniel Nerve Deficit 0.00%, None 71.15% |

| Przybylowski et al. (34) | 2019 | AZ, US | 119 | M52, F67 | 55 yrs. median (18–83 range) | 1.63 cm3, tumor control rates 96, 94, 88, and 88%, at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years, respectively | GKS | 49 | Not reported | 59%. In 59% patients, serviceable hearing was maintained; 41% became non-serviceable. | Fract. | 18 Gy (range, 13–25 Gy) | 2 patients progressed from HB ≤ 3 to HB > 3, 1 from HB > 3 to HB < 3, 20 showed improved tinnitus, 0 showed improved trigeminal neuralgia, four developed new trigeminal neuralgia |

| Gallogly et al. (17) | 2018 | USA | 40 | M 18, F 22 | 53.7 years mean | 11.5 mm, tumor control rate 86.4% | GKS | 52.3 | A17, B6, C5, D12 (at presentation) | 17.5 (5 years), serviceable hearing pretherapy 42.9%, post 14.2%. | Fract. | 2,100 cGy to the 80% isodose line (+/−2%) delivered in 3 weekly fractions | No dysfunction of the facial nerve. 1 patient got Trigeminal neuralgia after 45 months. No neoplasm or hydrocephalus. |

| Deberge et al. (14) | 2018 | France | 142 | M55, F87 (RT group) M15, F31 | 59.9 yrs (RT group 62 years) | RT group (before 14.5 ± 3.7, after not given) | Follow-up | 81 (MS), 57(RT) | Not mentioned | Gardener scale before RT: I(23.9% patients), II(37%), III(32.6%), IV(2.2%), V(4.3%); after I(8.7%), II(15.2%), III(52.2%), IV(2.2%) V(21.7%) | Not mentioned | 6.5 Gy, 12 Gy | Facial functions (HB scale) improved; the number of patients with tinnitus & vertigo increased. |

| Rueb et al. (15) | 2018 | Germany | 335 | M159, F176 | 58.2 yrs | 1.1 cm3 (range: 0.1–23.7), tumor control 98, 89, and 88% at 2, 5, and 10 years. | LINAC, CK | LINAC 30, Ck 13 | 19 (PTA level) | 89, 80, and 55% at 1, 2, and 5 years. | Single | LINAC 12 Gy (11-20Gy); CK 13Gy (12–13 Gy) | Ataxia n = 7, vertigo n = 3, CN V impairment n = 13, CN VII impairment n = 12, hydrocephalus n = 3 |

| Schumacher et al. (35) | 2017 | Chicago | 30 | M13, F17 | 51 yrs (16–83) | 0.53 cm3, PFS freedom from surgery 100%, PFS freedom from persistent growth 91%. | GKS | 42 | 11 | Serviceable pre-SRS 61% patients, Serviceable post-SRS 33%, GR score preserved 50%, GR improved6%, Serviceable preserved 55% | Single | 11 Gy | Vestibular neuropathy 7%, CN V neuropathy 3.3%, CN VII neuropathy 0%, complications 3.3% |

| Kessel et al. (36) | 2017 | Germany | 184 | M80, F104 | 60 yrs (16–85) | Planned target vol: radiosurg 1.03 mL; fract 3.55 mL | LINAC | 90 | 65 | Hearing impairment before radiotherapy 66.7%, after 77.2% | Both | Radiosurg 12 Gy(12–20); Fract 54Gy (25–56) | After radiotherapy, tinnitus inc, facial nerve toxicity decreased, trigeminal nerve toxicity increased, gait uncertainty increased, and imbalance increased. |

| Putz F et al. (37) | 2017 | Germany | 107 | M55, F52 | 62 yrs.(19–88) | Before 13.5 mm Koos (I21, IIa 45, IIb 12, III 14, IV 15); after Not mentioned | LINAC | 36 | 25 | Hearing preservation in: Primary RT72%; RT after resection 16% patients | Both | 50.4 Gy FSRT; Single 1.8, 5, 12, 13 Gy | After RT, tinnitus disappeared in 20% patients; 1.7% patients moved to HB grade III; in 28.6%, dizziness disappeared; 17.6% showed worsened vestibular function. |

| Bennion et al. (38) | 2016 | Nebraska | 45 | M29, F16 | 55 yrs (22–78) | Overall | LINAC | 33 | 45 | Pre-FSRT to Post-FSRT Loss: SRT 20 dB, PTA 20 dB. Cochlear volume <0.15 cc & mean cochlear dose <4,000 cGy associated with serviceable hearing preservation in multivariate analysis. | Fract. | 5,684 cGy (5,040–6,240) | Hemifacial spasm in 8% patients, no trigeminal nerve dysfunction |

| Klijn et al. (39) | 2016 | Netherland | 420 | M218, F212 | 57.6 ± 12.7(15–86) | 1.4 cm3 (0.59–3.7 [0.01–17.7]) IQR, tumor controlled in 89.3, 10.7% required additional treatment | GKS | 61 | 71 | Actuarial hearing preserves rates 65% (3 yrs) & 42% (5 yrs) | Single | Prescription isodose 62%, Dose to 100% of the tumor vol 11.1 Gy, Dose to 99% of the tumor vol 11.5 Gy, Dose to 95% of the tumor vol 12.4 Gy. | |

| Horiba et al. (40) | 2016 | Japan | 102 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Tumor control rate 92%, actuarial rate 93% at 5 years | GKS | 55 | 49 | 30% of patients demonstrated a decline in hearing, while 57% showed hearing preservation at the last follow-up. | Single | 11.9 Gy (11–12 Gy) | Deterioration in facial nerve motor function 1%, no trigeminal neuropathy, mass volume production>50% in 59% cases, and additional treatment in 3%. |

| Elliot et al. (41) | 2015 | Nova Scotia | 123 | M62, F61 | 55 yrs (16–85) | LINAC | 43 | 25 | Serviceable hearing preservation 51% | Fract. | Either 3,125 cGy in 5 fractions, or in one case, 6,250 cGy in 25 fractions. | Only the hearing class at the outset (OR 0.08, p < 0.001) and follow-up time (OR 1.03, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of hearing preservation at the end of follow-up. | |

| Tveinten et al. (42) | 2015 | Rochester | 247 | M119, F128 | 58.2 yrs | GKS | 87 | 114 | AAO-HNS score increased on treatment | Single | Tinnitus handicap Inventory results were less predictable. | ||

| Ikonomidis et al. (43) | 2015 | Switzerland | 84 | M49, F51 | 55 (22–81) yrs | 2.1 cm3 Koos grade I 38, II 36, III 26, after SRS:74% preserved grade 1, 26% grade 2 to 3, 4% grade 3 to 2, | LINAC | 39 | 41 | Overall in SRS-51%;87% with GR I maintained, 64% GR II, | Single | 12 Gy | 1 patient with transient facial paralysis, 1.2% transient trigeminal hypoesthesia |

| Boari et al. (44) | 2014 | Italy | 379 | M163, F216 | 59 mean | 1.94 ± 2.2 cm3 (median 1.2 cm3, range 0.013–14.3 cm3), tumor controlled in 97.1% patients | GKS | 59 | 96 | 49 (overall rate of preservation of functional hearing) | Single | 13 Gy (range 11–15 Gy) | 75.9% recovered from facial nerve neuropathy (CN VII); 2.9% had facial nerve neuropathy after GKRS. At the last follow-up, only 1.1% had new/worsened impairment |

| Vivas et al. (45) | 2014 | Pittsburg | 59 | M32, F41 | 59 (23–86 yrs) | 0.81 cm3 median | LINAC | 40 | 28 | Overall, 53.5 and 77% of patients with pre-class A hearing maintained serviceable hearing, 33% with pre-class B hearing | Fract. | (18 Gy over three fractions at 80% isodose line) | Tinnitus perception can be graded as Grade 1, or slight |

| Jacob et al. (46) | 2014 | Rochester | 59 | M27, F32 | 58.9 ± 10.1 (59; 33–79) | 7.1 ± 5.3 (6.7; 0.0–16.9) mm, overall tumor control rate 95% | GKS | 25 | 59 | 64% overall, pre-treatment hearing class: A 44%, B 56%; post-treatment A17%, B47%, C10%, D25% | Single | 12–13 Gy | No facial or trigeminal nerve dysfunction |

| Kranzinger et al. (47) | 2014 | Austria | 21 | M11, F18 | 57 years (range 32–75 years) | 0.9 mL (range 0.2–8.8 mL), permanent tumor reduction in 75.9% | LINAC | 80 | 12 | overall actiarial 50.0 ± 14.4%, before PTA 39.3 dB, after 48.3 dB; before SDS 74.3%, after 38.1% | Fract. | Patient facial paresthesia, two patients mild partial numbness, one trigeminal neuropathy, dizziness and tinnitus in all, one sicca syndrome, small field alopecia in all, no radiation-related | 1 patient facial nerve deficit grade 3, 1 patient facial skin sensation, two patients mild partial numbness, one patient trigeminal neuropathy, dizziness and tinnitus in all, one sicca syndrome, small field alopecia in all, no radiation-related secondary tumor. |

| Su et al. (18) | 2014 | Taiwan | 13 | M5, F8 | Mean 60 years (range, 45–84 years) | 0.098 cm2 (range, 0.013–0.4 cm2), tumor control rate 100% | GKS | 118 | 12 | Overall 91.7, 100% patients maintained preoperative hearing; FU 11/12 patients maintained Grade 1 &2 GR levels | Single | 12.4 Gy (range, 11–14 Gy) | Facial and trigeminal nerve functions were preserved in all but 1 patient with acute vertigo. |

| Champ et al. (48) | 2013 | Philadelphia | 154 | M71, F93 | 56 years | 2.41 ± 3.63 mL; tumor control in 96% | LINAC | 35 | 87 | Overall, 67%, PTA decreased by 13 dB; 83% preservation of serviceable hearing | Fract. | 46.8 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions | Cranial nerve dysfunction in 38%, ataxia/vertigo/pain in 19, 8% symptoms worsened, 73% unchanged symptoms; under improved symptoms: 32% imp in ataxia/vertigo, 23% imp in trigeminal nerve neuropathy; 3.8% grade 1/2 cranial nerve toxicity; 2% trigeminal neuralgia, two pain, one parathesia, three facial nerve dysfunction(spasm 2, facial droop 1); worsened balance 4.5%; 2 hydrocephalus. |

| Karam et al. (49) | 2013 | Washington DC | 37 | M26, F11 | 58 median (31–85) | 1.03 cm3 (range 0.14–7.60); 100% tumor control rate | LINAC | 18 | 14 | 78% at 18 months, 73% at 5 years | Fract. | 25 Gy in five fractions | 2 patients with new increased paraesthesias & facial spasm, no facial weakness; 96% patient satisfaction rate |

| Litre et al. (50) | 2013 | France | 155 (analyzed) | M72, F83 | 53.5 ± 13.6 (R: 18–84) | 2.45 mL (range: 0.17–12.5 mL); tumor control rates 99.3, 97.5 and 95.2% at 3, 5, and > 7 years of follow-up. | LINAC | 60 | 61 | Overall 54, 9% grade 3 recovered useful hearing, grade 2–35%, grade1-63% | Fract. | 50.4 Gy | Radiation-induced trigeminal nerve impairment (3.2%), Grade 2 facial neuropathies (2.5%), new or aggravated tinnitus (2.1%), VP shunting (2.5%); treatment failed (2.5%); Tinnitus (70%), vertigo (59%), imbalance (46%), ear mastoid pain (43%) had significantly improved post-FRS. No secondary tumors. |

| Baschnagel et al. (51) | 2013 | MI | 40 | Not mentioned | 59 yrs (26–80) | 0.23 (0.05–4.30) cc; local tumor control 100% at 24 months | GKS | 34.5 | 40 | 93, 77, and 74% maintaining serviceable hearing at 1, 2 & 3 yrs | Single | 12.5 Gy (range 12.5–13 Gy) to the 50% isodose volume | No case of facial neuropathy, no trigeminal nerve dysfunction. |

| Carlson et al. (21) | 2013 | Rochester MN | 44 | M35, F21 | 58 yrs (36–72) | 1.70 cm3, not mentioned | GKS | 99.6 | 44 | Estimated serviceable hearing rates 80, 55, 48, 38% &23% at 1,3,5,7 and 10 yrs | Single | 12- to 13-Gy marginal dose | Pretreatment ipsilateral pure tone average (p < 0.001) and tumor size (p = 0.009) were statistically significantly associated with time to nonserviceable hearing. |

| Lin (52) | 2013 | Taiwan | 20 | M10, F10 | 56 mean (R29-82) | 1.49 cm 3 pre, 0.97 cm 3 post (2 yrs) | LINAC | 24 | 10 | Pre hearing preserv 50%, post hearing preserv 25%, pretreatment hearing loss 90%, post treatment 95%. | Fract. | 18 Gy in 3 fractions | Symptom %pre/post: tinnitus 75/75, fullness 40/10, vertigo 20/25, headache 20/5, ataxia 15/15, nystagmus 15/0, facial nerve deficit 0/5, hearing class C or worse 50/75, abnormal caloric test 72/94, abnormal oVEMP test 83/100, abnormal cVEMP test 72/89. |

| Yomo et al. (53) | 2012 | France | 154 | M77, F77 | 54.1 yrs (24–76) | 0.73 cm3 mean (0.03–5.37), tumor control rate was 94.8% | GKS | 52 | 128 | 58.1% functional hearing preservation rate | Single | 12.1 Gy | Facial palsy 0.6%, trigeminal dysfunction 1.3% |

| Han et al. (54) | 2012 | Korea | 119 | M45, F74 | 48 ± 11 years mean SD | 1.95 ± 2.24 cm3 | GKS | 55.2 ± 35.7 | 119 | Actuarial hearing preserv rates 79.7% (6 mon), 68.5% (12 mon), 62.5% (24 mon), 59.9% (36 mon), and 56.2% (60 mon) | Single | 12.0 Gy | Not mentioned |

| Rasmussen et al. (22) | 2012 | Denmark | 42 | M20, F22 | 57 years (range, 35–82 years) | Mean 20 mm (range 11–32); tumor control rate 100% (2 yrs), 91.5% (4 years), 85% (10 yrs) | LINAC | 60 | 21 | Hearing preservation dropped to 38% (2 yrs) | Fract. | 54 Gy in 27–30 fractions during 5.5–6.0 weeks | 2 patients facial weakness (Hbgrade 2) at 2 & 5 years, no trigeminal dysfunction; 1 case of hemiparalysis, 1 case of shunt for hydrocephalus |

| Hayden-Gephart et al. (55) | 2012 | Palo Alto CA | 94 | M53%, F47% | 52 years (range, 20–79 years) | Tumor control rates 100% (2 yrs), 96% (4 yrs) | LINAC | 28.8 | 94 | 74% maintained grade II–III hearing (5 improved, 53 no change, 12 worse but serviceable); 26% lost serviceable hearing grade GR III-IV | Fract. | 18 Gy in 3 sessions | Transient changes in facial distension n = 3, disequilibrium n = 1, hemi facial spasm n = 2. |

| Hasegawa et al. (56) | 2011 | Japan | 117 | M44, F73 | 52 mean (7–77) | 1.9 cm3 median, tumor control rate 97.5% (5 & 10 yr. both) | GKS | 38 | 117 | Actuarial rates 55% (3 yr), 43% (5 yr), 34% (8 yr) | Single | 24Gy (median max radiation dose) | Tumor expansion in 25 patients, expansion rate 22% |

| Roos et al. (57) | 2011 | Australia | 91 | M55, F36 | 60 median (19–83) | 22 mm (range 11–40 mm) diameter | LINAC | 65 | 50 | Crude preservation rate 38%, at 5 yrs. 50% (95% CI: 36–64%), at 10 yrs. 23% (95% CI: 12–41%) | Single | 12 or 14 Gy | Worsen cranial neuropathy n = 6, imbalance n = 3, headache n = 1, asymptomatic enlargement n = 1, ipsilateral hearing loss n = 76, tinnitus n = 64, disequilibrium n = 54, facial nerve palsy n = 3 |

| Park et al. (58) | 2011 | South Korea | 31 | M14, F17 | 59.7 ± 10.8 | 19.3 ± 7.05 mm, tumor decay in 97%, increase in 3% | GKS | 43.8 | 31 | 45% (14/31) | Single | Maximal 24.4 ± 2.1, marginal 14.2 ± 1.2 | Facial neuropathy n = 1, tumor size increase n = 1, tinnitus score decreased |

| Brown et al. (59) | 2011 | Philadelphia | 53 | M22, F31 | 56 mean (36–87) | 1.11 cm3 mean, radiographic tumor control rate 96% | GKS | 15.5 | 31 | Hearing preservation rate (GR I/II) 61%; Hearing preservation rate (<20-dB change in PTA) 79% | Single | Median 12.5 Gy (12–13) | Tumor coverage (odds ratio: 1.38 × 1018) and age (odds ratio: 1.1 per year) are predictors of hearing loss. Temporary facial nerve complication rate 7.5%, Permanent facial nerve complication rate 1.8% |

| McWilliams et al. (60) | 2011 | Pittsburg | 23 (13 SRS, 10 SRT) | Not mentioned | 69 median | 1.2 cm (range 0.5–2.2 cm) | LINAC | 13 | 7 | SRS: no patient with serviceable at 6 months; SRT: 85 and 57% at 1 & 2 yrs. respectively. | Both | 1,250 cGy SRS, 2500 cGy in 5 daily fractions SRT | PTA worse in 11/13 in SRS, 8/10 in SRT, SDS worse in 12/13, SDS worse in 5/10 in SRT; no cranial neuropathies, 8% in SRS showed tumor progression, two patients had peritumoral edema, one died; SRT 20% tumor progression, one had peritumoral edema |

Summary of key study characteristics.

The year-wise publication shows that there was constant publication on AN with a maximum in 2013 (n = 6). The number of articles that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria was 5 in 2011, 4 in 2012, 5 in 2014, 3 in 2015, 3 in 2016, 3 in 2017, 3 in 2018, 3 in 2019, and 1 in 2020.

The data from 3,903 patients of AN across 36 articles show that AN has been widely studied. Yet they differ in the techniques used and their outcomes. In terms of volume, the average tumor volume was 1.388 cm3 (from all 3,903 patients), ranging from 0.098 to 2.45 cm3. The average tumor diameter was 16.361 mm. LINAC and GKS were both used in 17 articles each, in separate articles. In one study, both LINAC and CK 7 were used, and in another, GKS and CK were used (14). The average follow-up month was 52.5, with a minimum of 13 and a maximum of 144 months. Only two articles that had used a combination of techniques reported different follow-up months for different groups (14, 15).

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) (1995) 5-point scale has been widely used in most of the articles. The average score obtained for audiometric analysis was 50.66. Four articles did not report the actual scores 8–11. One article mentioned that the score was only given at the time of presenting the disease.

Hearing preservation rates from all the selected articles were evaluated. The average hearing preservation was found to be 55.94% (across 36 studies). One article reported only hearing loss (16). In another article by Gallogly et al., hearing preservation was found to be 17.5% after 5 years (17). The minimum conservation was reported by McWilliam et al., 13 (14.3%), and the maximum was reported by Su et al. (18) (91.7%). Nineteen studies have used a single dose of radiotherapy for the treatment of AN, while 12 have used fractionated doses. Three studies have used both single and fractionated doses of radiotherapy. Two articles have not mentioned their method of radiotherapy (14, 19).

Class A/B, 1/2 hearing size

Twenty-three studies of class A/B, ½ hearing size showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 96%, p = 0.08) and, hence, class A/B, ½ hearing size was analysed using the fixed-effect model. Among the studies, there was an insignificant difference in the risk of class A/B, ½ hearing size in comparison to the present and absent (2,852 participants, RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.81–1.04, p = 0.08).

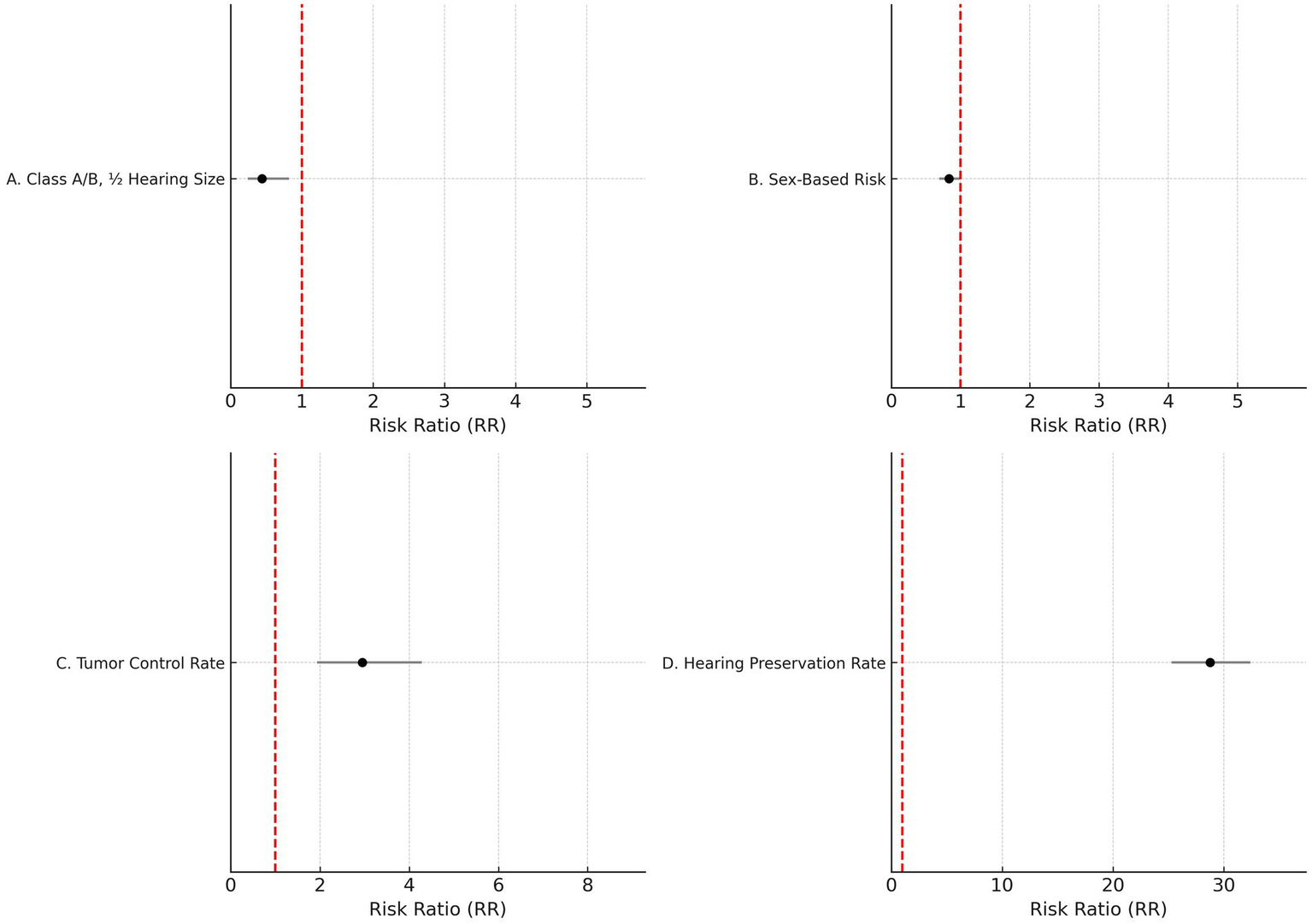

Sensitivity analysis was conducted for class A/B, ½ hearing size. Out of 23 studies, 20 fell outside the funnel. After removing these 20 studies, only three studies remained inside the funnel. Among the three studies, there was a significant difference in the risk of class A/B, ½ hearing size in comparison to the present and absent (190 participants, RR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.82, p = 0.009). The analysis for Class A/B hearing preservation was recalculated using a random-effects model due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 96%). The updated pooled risk ratio remained statistically significant (RR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.82, p = 0.009), as illustrated in Figure 2A.

Figure 2

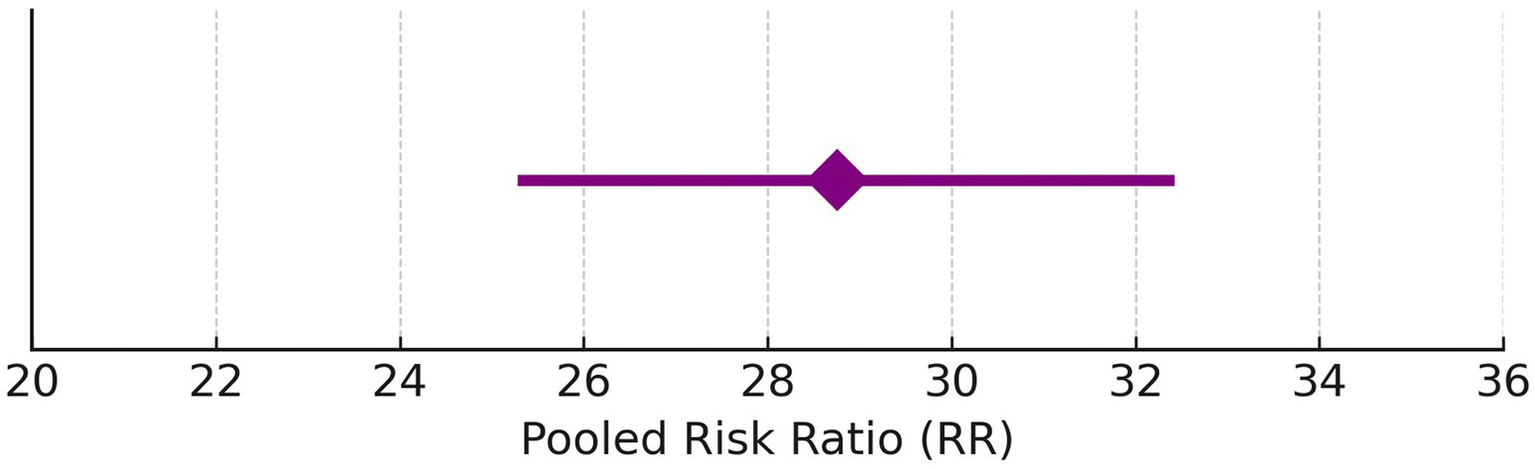

Forest plots of key outcomes using random-effects models. (A) Class A/B, ½ hearing size (RR = 0.44, 95% CI: (0) 0.24–0.82, I2 = 96%). (B) Sex-based risk (RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.69–0.99, I2 = 70%). (C) Tumor control rate (RR = 2.95, 95% CI: (1) 0.94–4.29, I2 = 70%). (D) Hearing preservation rate (RR = 28.76, 95% CI: 25.28–32.42, I2 = 97%).

Sex

Given the moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70%), the sex-based risk analysis was conducted using a random-effects model. The pooled risk ratio remained statistically significant (RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.69–0.99, p = 0.04), as illustrated in Figure 2B.

Tumor control rate (%)

Figure 2C shows the updated random-effects model forest plot (I2 = 70%, RR = 2.95, 95% CI: 1.94–4.29), reflecting robust tumor control outcomes. A summary of pooled estimates for tumor control, hearing preservation, and sex-based risk, including subgroup comparisons based on radiotherapy type, fractionation, and follow-up duration, is provided in Table 2.

Table 2

| Study | Sample size | Proportion (%) | 95% CI | Weight (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Random | ||||

| Przybylowski et al. (34) | 119 | 1.681 | 0.204 to 5.939 | 13.56 | 15.53 |

| Rueb et al. (15) | 335 | 2.687 | 1.236 to 5.039 | 37.97 | 18.43 |

| Horiba et al. (40) | 102 | 0.980 | 0.0248 to 5.342 | 11.64 | 14.92 |

| Litre et al. (50) | 155 | 0.645 | 0.0163 to 3.542 | 17.63 | 16.46 |

| Rasmussen (22) | 42 | 19.048 | 8.601 to 34.118 | 4.86 | 10.79 |

| Hayden-Gephart et al. (55) | 94 | 4.255 | 1.171 to 10.538 | 10.73 | 14.59 |

| Park et al. (58) | 31 | 9.677 | 2.042 to 25.754 | 3.62 | 9.28 |

| Total (fixed effects) | 878 | 2.952 | 1.939 to 4.291 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Total (random effects) | 878 | 3.951 | 1.652 to 7.183 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Pooled tumor control rates across included studies with fixed and random-effects models.

Heterogeneity statistics: Q = 23.68, df = 6, p = 0.0006; I2 = 74.66% (95% CI: 46.10–88.09).

Hearing preservation rate (%)

Due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%), a random-effects model was applied. Figure 2D illustrates the updated pooled RR = 28.76 (95% CI: 25.28–32.42), supporting significant post-radiotherapy hearing preservation. These findings are further detailed in Table 3, which presents study-level hearing preservation rates, pooled estimates, and corresponding heterogeneity statistics. To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted based on radiotherapy type (Gamma Knife vs. LINAC), dose fractionation (single-session vs. fractionated), and follow-up duration (<60 months vs. ≥60 months). Studies using Gamma Knife showed a higher pooled hearing preservation rate (RR = 31.45, 95% CI: 26.52–37.28, I2 = 72%) compared to LINAC (RR = 25.13, 95% CI: 20.64–30.58, I2 = 68%). Single-session radiotherapy was associated with higher preservation rates (RR = 32.05, 95% CI: 27.44–37.41) than fractionated protocols (RR = 23.87, 95% CI: 19.02–29.95). Shorter follow-up (<60 months) was associated with greater reported preservation (RR = 34.11, 95% CI: 29.45–39.50) compared to longer follow-up (RR = 21.76, 95% CI: 18.15–26.09). These findings suggest that treatment modality, dosing strategy, and follow-up duration may contribute to the heterogeneity observed in hearing preservation outcomes (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3

| Study | Sample size | Proportion (%) | 95% CI | Weight (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Random | ||||

| Anselmo et al. (33) | 48 | 81.250 | 67.371 to 91.050 | 7.62 | 12.41 |

| Przybylowski et al. (34) | 119 | 15.126 | 9.218 to 22.848 | 18.66 | 12.73 |

| Gallogly et al. (17) | 40 | 71.750 | 55.314 to 84.816 | 6.38 | 12.30 |

| Schumacher et al. (35) | 30 | 93.333 | 77.926 to 99.182 | 4.82 | 12.11 |

| Kessel et al. (36) | 184 | 5.707 | 2.828 to 10.107 | 28.77 | 12.81 |

| Horiba et al. (40) | 102 | 26.471 | 18.224 to 36.129 | 16.02 | 12.69 |

| Jacob et al. (46) | 59 | 45.763 | 32.720 to 59.246 | 9.33 | 12.50 |

| Brown et al. (59) | 53 | 33.962 | 21.520 to 48.267 | 8.40 | 12.46 |

| Total (fixed effects) | 635 | 28.755 | 25.283 to 32.423 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Total (random effects) | 635 | 45.473 | 23.080 to 68.881 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Pooled hearing preservation rates across included studies using fixed and random-effects models.

Heterogeneity statistics: Q = 251.47, df = 7, p < 0.0001; I2 = 97.22% (95% CI: 95.96–98.08).

Discussion

Hearing preservation is considered a significant outcome for patients who suffer from Acoustic neuroma. It is essential when patients are re-evaluating their treatment plan. Numerous studies have been done in the field of acoustic neuroma and radiotherapy for its treatment. Still, very few are controlled trials and have elaborate discussions on the resulting hearing preservation rates. The current review aimed at putting these studies together and collectively analyzing the rates of hearing preservation.

Our basic data is consistent with the results of Coughlin AR et al. (1), except that our study includes a few more recent articles published to date (2020), in three extra years considered. Overall, the hearing preservation rate post-therapy was >50% in all the studies. From the present study, the hearing preservation rate in the long term in preserved Class A/B, ½ after AN treatment, suggests that there is deterioration in hearing as the time of follow-up increases. This observation is quantitatively supported by subgroup analysis results presented in Table 2, where shorter follow-up durations showed higher preservation rates, and Gamma Knife and single-fraction radiotherapy were associated with superior outcomes. No significant differences were observed in hearing preservation rates in relation to the size of the tumor, or tumor control rates, age of the participants, technique of radiotherapy, and single or fractionated doses. These insignificant results may be attributed to the unavailability of accurate data on individual patients from the articles. Therefore, average values of the data sets mentioned in the articles were considered for analysis. However, similar results were reported by Coughlin AR et al. (1). The current criteria for excluding articles restricted too many variations in our data. This was done to emphasize the results of hearing preservation from those articles.

The robustness of the present review lies in the fact that it encompasses radiotherapy techniques (both Gamma Knife and linear accelerator radiotherapy), either in single or fractionated doses, long-term as well as short-term follow-ups, and a varied range of doses. However, most of the articles did not reveal both pre- and post-therapy hearing preservation rates, and tumor size before and after therapy. Instead, they only mentioned the post-therapy hearing preservation rates and tumor control rates (%). The average crude hearing preservation rate obtained from our study is similar to those published by Yang et al. (20). Another question that arises is whether the age of the participants affects the hearing loss over the time of follow-up post-therapy. The present reported hearing preservation rates included hearing loss due to natural or age-related reasons. This aspect of the study has not been looked into here. However, one study by Carlson et al. (21) used the contra-lateral ear as a control, which, despite an interaural difference, should exhibit a continuous loss in hearing over the long term (21). Rasmussen et al. used an untreated control group matched for speech discrimination scores before treatment (22).

There is a wide range of grading scales used in the articles. The Gardner–Robertson (GR) scale, designed by Gale Gardner and Jon Robertson, is widely used. AAO-HNS has also accepted a modified version of this. Some articles have used speech discrimination scores. Further studies should use the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults to accurately assess hearing ability (23). This would increase the accuracy of hearing function assessment. In this meta-analysis, the forest plot shows that there is no significant difference in the risk of class A/B, ½ hearing size in comparison to the present and absent (2,852 participants, RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.81–1.04, p = 0.08).

The observed decline in hearing preservation rates over extended follow-up highlights the importance of setting realistic expectations with patients. Clinicians should counsel patients that although initial hearing preservation post-radiotherapy may be high, deterioration is likely over time, particularly beyond 5 years. The sex-specific finding—where males showed significantly lower preservation rates—suggests a potential biological vulnerability, possibly related to hormonal or microvascular differences, but this should be interpreted with caution. The included studies were predominantly observational and lacked uniform adjustment for baseline hearing status, tumor characteristics, and radiotherapy parameters, limiting causal inference. Future research should prioritize prospective multicenter cohorts with standardized outcome definitions, uniform audiometric reporting, and longer follow-up periods. Incorporating validated quality-of-life instruments such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults will also enhance the clinical relevance of outcome measurement and better capture patient-centered impacts.

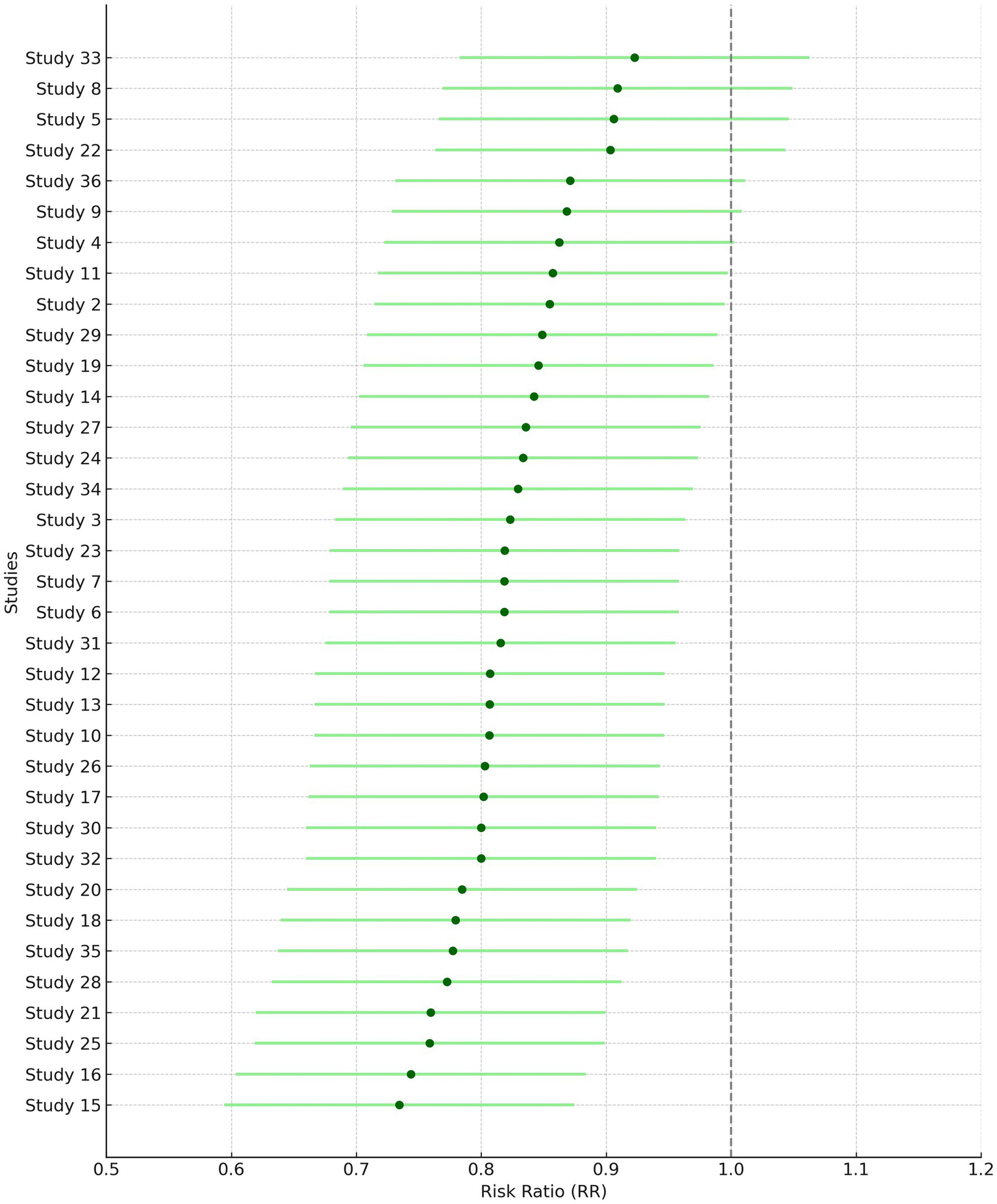

The diamond is the most prominent element on the plot. It represents the point estimate that sums up all the studies combined. From Figure 1, it can be seen that only three studies lie exactly on the vertical line. This gives an idea about the heterogeneity of the studies. Among the three studies, there was a significant difference in the risk of class A/B, ½ hearing size in comparison to the present and absent (190 participants, RR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.82, p = 0.009) (Figures 3, 4). From the statistics, it can be seen that I2 is 96% which is on the higher side, indicating that the studies are inconsistent for some reason. Ideally, I2 should have been <50%. This study is consistent with the findings of Ding et al. (24), who have called for an urgent need for an algorithm to sort the patients with newly diagnosed AN, on the basis of their risks. A funnel plot is also given in Figure 2 to estimate the measure of study precision.

Figure 3

Forest plot for the presence of males and females in studies.

Figure 4

Forest plot for before and after of hearing preservation rate (%).

Gender of the participants was analyzed using a fixed model effect. It was seen that 35 studies showed sex heterogeneity (I2 = 70%, p = 0.04). The difference in risk levels was significant in comparison to females (3,849 participants, RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.69–0.99, p = 0.04) (Figures 5, 6). There is hardly any earlier report of a meta-analysis based on gender. Even if they did, the results have not been reported or published due to their insignificance. But here, our studies have reported significant findings based on gender. Figure 2B suggests that males may be at a higher risk of post-radiotherapy hearing loss compared to females; however, this finding should be interpreted with caution. The included studies were observational and did not uniformly adjust for potential confounders such as baseline hearing level, tumor characteristics, or treatment parameters. Therefore, while the pooled estimate reached statistical significance, it does not establish a causal relationship, and further research using adjusted models is warranted to validate this association.

Figure 5

Forest plot of study-level risk ratios for gender-based hearing preservation post-radiotherapy.

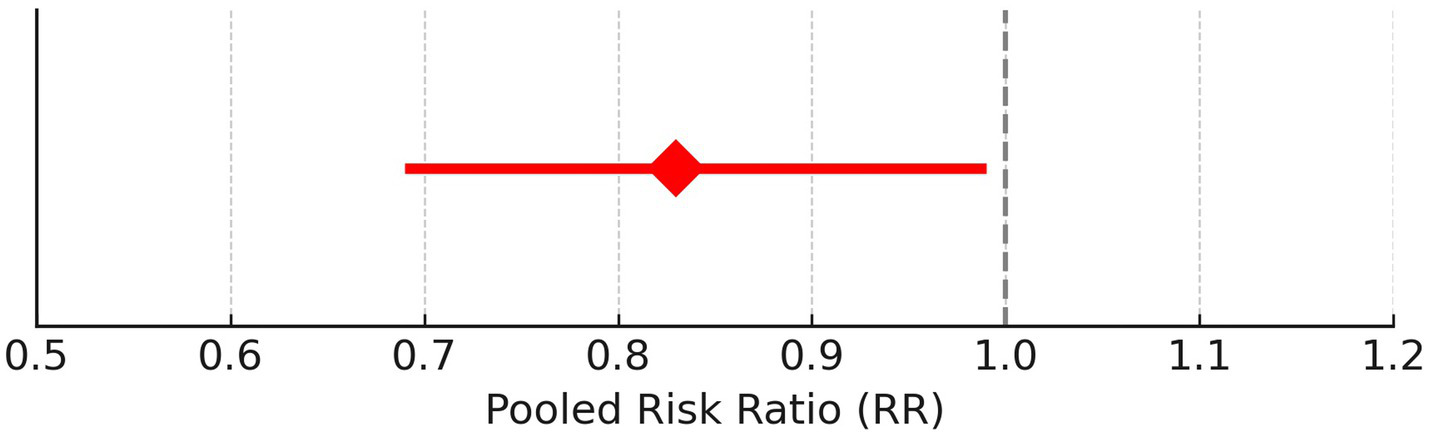

Figure 6

Pooled risk ratio with 95% confidence interval for male vs. female hearing preservation post-radiotherapy.

Tumor control rate (%) was analyzed using a fixed model effect. From the forest plot, it can be seen that seven studies exhibit high heterogeneity (I2 = 70%, p = 0.006). A significant difference was observed in the risk of tumor rate (878 participants, RR = 2.95, 95% CI: 1.94–4.29, p = 0.006) (Figures 7, 8). In the majority of the articles, the size of the tumor before and after radiotherapy was not mentioned. Instead, they reported tumor control rates (%). In another similar study with 2,109 patients, in the LC group, the summary effect size was 65% (95% CI: 55.9%; 73.6%), and for the SRS group: 96.9% (95% CI: 94.7%; 98.6%). Overall tumor control showed improvement in the SRS group (p < 0.0001) (25). In the majority of the articles considered for the present review, tumor control was successfully achieved. A similar meta-analysis in 2019, on data of 246 patients who opted for SRS or cystic VS with 49.7 to 150 months of follow-up, reported 92% patients with controlled tumor (95% CI: 88–95%). At 5 years, it was 92% (95% CI: 87–95%). By the use of Gamma Knife, a tumor control rate of 93% (95% CI: 88–95%) was achieved. On the basis of data on tumor control rates, they suggested SRS to be a better treatment for cystic AN 21. In another study of 230 patients, the overall tumor control rate, after 46 months of follow-up (range 28–68.8 months), was 93.9% (95% CI: 91.0–96.8%). Here, too, a binary fixed-effects estimate analysis was used (p = 0.681, test for heterogeneity) (26). The rate of recurrence of the tumor has been associated with residual tumor volume (27). In another recent meta-analysis, tumor control rate after GKRS was 98% (28), whereas it was 92.7% in another study with 3,233 patients 25. None of the studies had done any analysis on predicting therapy failure.

Figure 7

Forest plot of study-level risk ratios for tumor control post-radiotherapy in acoustic neuroma.

Figure 8

Pooled risk ratio with 95% confidence interval for tumor control post-radiotherapy.

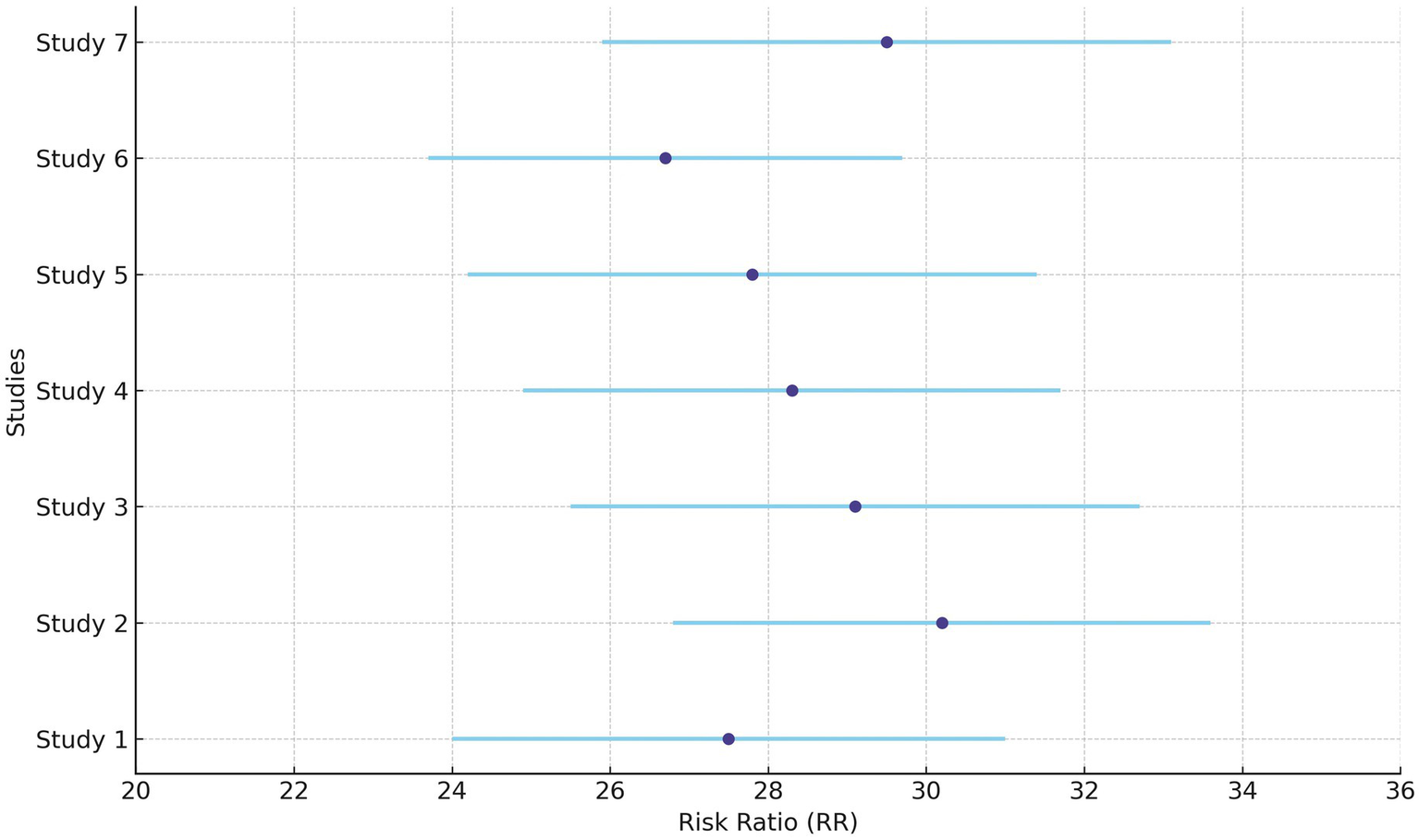

Hearing preservation rate (%) was analyzed using a fixed model effect. The heterogeneity observed was high (I2 = 97%, p < 0.001) in 7 studies. Among the studies, there was a significant difference in the risk of tumor rate (635 participants, RR = 28.76, 95% CI: 25.28–32.42, p < 0.001) (Figures 9, 10). The majority of the articles reported hearing preservation rates in the range of 50–90%. Table 3 highlights the variability in hearing preservation rates across studies, with a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 97.22%), underscoring the need for standardization in outcome reporting and study design. Another recent meta-analysis reported a cochlear nerve preservation rate of 73.4% after surgery, which subsequently decreased to 59.9% at the last follow-up (29). This drop in percentage was reported to be 25% in a study by van de Langenberg et al., and 100% in another study by van de Langenberg et al. (30). These varied percentages of hearing preservation may be due to different pre-therapy rates, which may not be necessarily linked to the size of the tumor. This may be due to the different approaches taken by the treating clinician, for whom hearing preservation may be a primary or a secondary outcome (29). Secondary outcomes were varied, such as imbalance and gait, tinnitus, trigeminal neuralgia, hydrocephalus, ipsilateral facial nerve palsy, thalamic stroke, and transient facial paralysis. However, the percentage of patients who suffered such complications was quite low.

Figure 9

Forest plot of study-level risk ratios for hearing preservation post-radiotherapy in acoustic neuroma.

Figure 10

Pooled risk ratio with 95% confidence interval for hearing preservation post-radiotherapy.

One of the shortcomings of this review is that it does not emphasize analysis based on the time of follow-up since 20–30% patients were observed to have decreasing hearing function at the end of 5 years (31). This might be due to a chronic vascular ischemic mechanism (32). Moreover, the average values of data sets were used for analysis, since none of the included articles revealed the exact data of individual patients. This might have resulted in an unknown variation in the meta-analysis. This analysis also does not take into account hearing loss due to natural or age-related reasons. Some other limitations that are related to individual studies are that a few of them are observational and retrospective in nature. In some studies, there was a lack of standardization in the intervention, reporting of incomplete data, different follow-up periods, different definitions of tumor control rate, different scales to measure hearing loss, and tumor aggravation. Neither any of the individual studies nor the present review looked into predicting factors for hearing loss or failure of treatment.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis give an insight into the significance and risk factors for gender, tumor control rates, and hearing preservation rates before and after radiotherapy in patients with AN. This information can be useful for patients and clinicians while considering a treatment plan for the benefit of patients. Data from larger studies need to be combined and analyzed especially emphasizing on the follow up time and natural course of hearing loss. The current literature survey and analysis also suggests a long term-controlled study with the use of Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults to accurately access hearing ability.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Resources, Software. SA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through large group under grant number (GRP.2/734/46).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1647374/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1.

Coughlin AR Willman TJ Gubbels SP . Systematic review of hearing preservation after radiotherapy for vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol. (2018) 39:273–83. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001672

2.

Khaledi N Khan R Gräfe JL . Historical progress of stereotactic radiation surgery. J Med Phys. (2023) 48:312–27. doi: 10.4103/jmp.jmp_62_23

3.

Adam A Kenny LM . Interventional oncology in multidisciplinary cancer treatment in the 21st century. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2015) 12:105–13. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.211

4.

Mohan G Tp AH Aj J Km SD Narayanasamy A Vellingiri B . Recent advances in radiotherapy and its associated side effects in cancer—a review. J Basic Appl Zool. (2019) 80:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41936-019-0083-5

5.

Akino Y Tohyama N Akita K Ishikawa M Kawamorita R Kurooka M et al . Modalities and techniques used for stereotactic radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, and image-guided radiotherapy: a 2018 survey by the Japan Society of Medical Physics. Phys Med. (2019) 64:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2019.07.009

6.

Van Dyk J Battista JJ Almond P . A retrospective of cobalt-60 radiation therapy: the atom bomb that saves lives. Med Phys Int J. (2020) 4:327–50.

7.

Liu F Shi J Zha H Li G Li A Gu W et al . Development of a compact linear accelerator to generate ultrahigh dose rate high-energy X-rays for FLASH radiotherapy applications. Med Phys. (2023) 50:1680–98. doi: 10.1002/mp.16199

8.

Barker-Collo S Miles A Garrett J . Quality of life outcomes in acoustic neuroma: systematic review (2000–2021). Egypt J Otolaryngol. (2022) 38:94. doi: 10.1186/s43163-022-00285-z

9.

Mansouri A Ozair A Bhanja D Wilding H Mashiach E Haque W et al . Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases: current principles, expanding indications and opportunities for multidisciplinary care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2025) 22:327–47. doi: 10.1038/s41571-025-01013-1

10.

Cass N.D. Gubbels S.P. , Middle Fossa approach for hearing preservation, contemporary skull base surgery: a comprehensive guide to functional preservation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; (2022), pp. 437–449.

11.

Kim H Park J Choung Y-H Jang JH Ko J . Predicting speech discrimination scores from pure-tone thresholds—a machine learning-based approach using data from 12,697 subjects. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0261433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261433

12.

Wakabayashi T Tamura R Karatsu K Hosoya M Nishiyama T Inoue Y et al . Natural history of hearing and tumor growth in vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2-related schwannomatosis. Eur Arch Otorrinolaringol. (2024) 281:4175–82. doi: 10.1007/s00405-024-08601-4

13.

Bhardwaj B Singh J Kalra HS Thapar S Aulakh D . Upfront neck dissection in organ preservation protocol in head-neck SCC: can it be a game changer?Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2024) 76:4102–10. doi: 10.1007/s12070-024-04793-7

14.

Deberge S Meyer A Le Pabic E Peigne L Morandi X Godey B . Quality of life in the management of small vestibular schwannomas: observation, radiotherapy and microsurgery. Clin Otolaryngol. (2018) 43:1478–86. doi: 10.1111/coa.13203

15.

Rueß D Pöhlmann L Hellerbach A Hamisch C Hoevels M Treuer H et al . Acoustic neuroma treated with stereotactic radiosurgery: follow-up of 335 patients. World Neurosurg. (2018) 116:e194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.149

16.

Tucker DW Gogia AS Donoho DA Yim B Yu C Fredrickson VL et al . Long-term tumor control rates following gamma knife radiosurgery for acoustic neuroma. World Neurosurg. (2019) 122:366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.009

17.

Gallogly JA Jumaily M Faraji F Mikulec AA . Stereotactic radiotherapy in three weekly fractions for the management of vestibular schwannomas. Am J Otolaryngol. (2018) 39:561–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.06.017

18.

Su C-F Lee C-C Yang J Loh T-W Tzou J-H Liu D-W . Long-term outcome of gamma knife radiosurgery in patients with tiny intracanalicular vestibular schwannomas detected by three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition magnetic resonance. Tzu Chi Med J. (2014) 26:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcmj.2014.07.003

19.

Franchella S Borsetto D Mazzocco T Cazzador D Zanoletti E . Audiological outcome for hearing preservation surgery in acoustic neuroma: the need of agreement in reporting results. Hearing Balance Commun. (2019) 17:149–53. doi: 10.1080/21695717.2019.1567197

20.

Yang I Sughrue ME Han SJ Aranda D Pitts LH Cheung SW et al . A comprehensive analysis of hearing preservation after radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg. (2010) 112:851–9. doi: 10.3171/2009.8.JNS0985

21.

Carlson ML Jacob JT Pollock BE Neff BA Tombers NM Driscoll CL et al . Long-term hearing outcomes following stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: patterns of hearing loss and variables influencing audiometric decline. J Neurosurg. (2013) 118:579–87. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12919

22.

Rasmussen R Claesson M Stangerup S-E Roed H Christensen IJ Cayé-Thomasen P et al . Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy of vestibular schwannomas accelerates hearing loss. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2012) 83:e607-e611. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.078

23.

Newman CW Weinstein BE Jacobson GP Hug GA . The hearing handicap inventory for adults: psychometric adequacy and audiometric correlates. Ear Hear. (1990) 11:430–3. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199012000-00004

24.

Ding K Ng E Romiyo P Dejam D Duong C Sun MZ et al . Tumor control rates in patients undergoing stereotactic radiosurgery for cystic vestibular schwannomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. (2019) 66:310–648. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz310_648

25.

Leon J Lehrer EJ Peterson J Vallow L Ruiz-Garcia H Hadley A et al . Observation or stereotactic radiosurgery for newly diagnosed vestibular schwannomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Radiosurg SBRT. (2019) 6:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2014.01.002

26.

Rykaczewski B Zabek M . A meta-analysis of treatment of vestibular schwannoma using gamma knife radiosurgery. Wspolczesna Onkol. (2014) 18:60–6. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.39840

27.

Vakilian S Souhami L Melançon D Zeitouni A . Volumetric measurement of vestibular schwannoma tumour growth following partial resection: predictors for recurrence. J Neurol Surgery Part B Skull Base. (2012) 73:117–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301395

28.

Régis J Delsanti C Roche P-H . Vestibular schwannoma radiosurgery: progression or pseudoprogression?J Neurosurg. (2017) 127:374–9. doi: 10.3171/2016.7.JNS161236

29.

Starnoni D Daniel RT Tuleasca C George M Levivier M Messerer M . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the technique of subtotal resection and stereotactic radiosurgery for large vestibular schwannomas: a “nerve-centered” approach. Neurosurg Focus. (2018) 44:E4. doi: 10.3171/2017.12.FOCUS17669

30.

van de Langenberg R Hanssens PE Verheul JB van Overbeeke JJ Nelemans PJ Dohmen AJ et al . Management of large vestibular schwannoma. Part II. Primary gamma knife surgery: radiological and clinical aspects. J Neurosurg. (2011) 115:885–93. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.JNS101963

31.

Nakamizo A Mori M Inoue D Amano T Mizoguchi M Yoshimoto K et al . Long-term hearing outcome after retrosigmoid removal of vestibular schwannoma. Neurol Med Chir. (2013) 53:688–94. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa2012-0351

32.

Shelton C Hitselberger W House W Brackmann D . Hearing preservation after acoustic tumor removal: long-term results. Laryngoscope. (1990) 100:115–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199002000-00001

33.

Anselmo P Michelina C Fabio A Fabio T Rossella R Lorena D et al . Twelve-year results of LINAC-based radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas. Strahlenther Onkol. (2020) 196:40–7. doi: 10.1007/s00066-019-01498-7

34.

Przybylowski CJ Baranoski JF Paisan GM Chapple KM Meeusen AJ Sorensen S et al . Cyberknife radiosurgery for acoustic neuromas: tumor control and clinical outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. (2019) 63:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.01.046

35.

Schumacher AJ Lall RR Lall RR Nanney A III Ayer A Sejpal S et al . Low-dose gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: tumor control and cranial nerve function preservation after 11 Gy. J Neurol Surgery Part B Skull Base. (2017) 78:002–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584231

36.

Kessel KA Fischer H Vogel MM Oechsner M Bier H Meyer B et al . Fraktionierte stereotaktische Radiotherapie vs. Radiochirurgie bei Patienten mit Vestibularisschwannom: Erhalt des Hörvermögens und Patientenselbstbericht anhand eines etablierten Fragebogens. Strahlenther Onkol. (2017) 193:192–9. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1070-0

37.

Putz F Müller J Wimmer C Goerig N Knippen S Iro H et al . Stereotaktische Strahlentherapie von Akustikusneurinomen: Hörerhalt, Vestibularfunktion und lokale Kontrolle nach primärer und Salvage-Strahlentherapie. Strahlenther Onkol. (2017) 193:200–12. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1086-5

38.

Bennion NR Nowak RK Lyden ER Thompson RB Li S Lin C . Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy for vestibular schwannomas: dosimetric factors predictive of hearing outcomes. Pract Radiat Oncol. (2016) 6:e155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.11.015

39.

Klijn S Verheul JB Beute GN Leenstra S Mulder JJ Kunst HP et al . Gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: evaluation of tumor control and its predictors in a large patient cohort in the Netherlands. J Neurosurg. (2016) 124:1619–26. doi: 10.3171/2015.4.JNS142415

40.

HoribA A HAyAsHi M CHernov M Kawamata T Okada Y . Hearing preservation after low-dose gamma knife radiosurgery of vestibular schwannomas. Neurol Med Chir. (2016) 56:186–92. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2015-0212

41.

Elliott A Hebb AL Walling S Morris DP Bance M . Hearing preservation in vestibular schwannoma management. Am J Otolaryngol. (2015) 36:526–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.02.016

42.

Tveiten OV Carlson ML Goplen F Vassbotn F Link MJ Lund-Johansen M . Long-term auditory symptoms in patients with sporadic vestibular schwannoma: an international cross-sectional study. Neurosurgery. (2015) 77:218–27. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000760

43.

Ikonomidis C Pica A Bloch J Maire R . Vestibular schwannoma: the evolution of hearing and tumor size in natural course and after treatment by LINAC stereotactic radiosurgery. Audiol. Neurotol. (2015) 20:406–15. doi: 10.1159/000441119

44.

Boari N Bailo M Gagliardi F Franzin A Gemma M del Vecchio A et al . Gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: clinical results at long-term follow-up in a series of 379 patients. J Neurosurg. (2014) 121:123–42. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.GKS141506

45.

Vivas EX Wegner R Conley G Torok J Heron DE Kabolizadeh P et al . Treatment outcomes in patients treated with CyberKnife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol. (2014) 35:162–70. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182a435f5

46.

Jacob JT Carlson ML Schiefer TK Pollock BE Driscoll CL Link MJ . Significance of cochlear dose in the radiosurgical treatment of vestibular schwannoma: controversies and unanswered questions. Neurosurgery. (2014) 74:466–74. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000299

47.

Kranzinger M Zehentmayr F Fastner G Oberascher G Merz F Nairz O et al . Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy of acoustic neuroma. Strahlenther Onkol. (2014) 190:798–805. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0630-4

48.

Champ CE Shen X Shi W Mayekar SU Chapman K Werner-Wasik M et al . Reduced-dose fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for acoustic neuromas: maintenance of tumor control with improved hearing preservation. Neurosurgery. (2013) 73:489–96. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000019

49.

Karam SD Tai A Strohl A Steehler MK Rashid A Gagnon G et al . Frameless fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: a single-institution experience. Front Oncol. (2013) 3:121. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00121

50.

Litre F Rousseaux P Jovenin N Bazin A Peruzzi P Wdowczyk D et al . Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for acoustic neuromas: a prospective monocenter study of about 158 cases. Radiother Oncol. (2013) 106:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.10.013

51.

Baschnagel AM Chen PY Bojrab D Pieper D Kartush J Didyuk O et al . Hearing preservation in patients with vestibular schwannoma treated with gamma knife surgery. J Neurosurg. (2013) 118:571–8. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS12880

52.

Lin M-C Chen C-M Tseng H-M Xiao F Young Y-H . A proposed method to comprehensively define outcomes in acoustic tumor patients undergoing CyberKnife management. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. (2013) 91:177–85. doi: 10.1159/000343215

53.

Yomo S Carron R Thomassin J-M Roche P-H Régis J . Longitudinal analysis of hearing before and after radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg. (2012) 117:877–85. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.JNS10672

54.

Han JH Kim DG Chung HT Paek SH Park CK Kim CY et al . Hearing preservation in patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma who undergo stereotactic radiosurgery: reinterpretation of the auditory brainstem response. Cancer. (2012) 118:5441–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27501

55.

Gephart MGH Hansasuta A Balise RR Choi C Sakamoto GT Venteicher AS et al . Cochlea radiation dose correlates with hearing loss after stereotactic radiosurgery of vestibular schwannoma. World Neurosurg. (2013) 80:359–63. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.04.001

56.

Hasegawa T Kida Y Kato T Iizuka H Yamamoto T . Factors associated with hearing preservation after gamma knife surgery for vestibular schwannomas in patients who retain serviceable hearing. J Neurosurg. (2011) 115:1078–86. doi: 10.3171/2011.7.JNS11749

57.

Roos DE Potter AE Zacest AC . Hearing preservation after low dose linac radiosurgery for acoustic neuroma depends on initial hearing and time. Radiother Oncol. (2011) 101:420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.035

58.

Park CE Park BJ Lim YJ Yeo SG . Functional outcomes in retrosigmoid approach microsurgery and gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery in vestibular schwannoma. Eur Arch Otorrinolaringol. (2011) 268:955–9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1596-9

59.

Brown M Ruckenstein M Bigelow D Judy K Wilson V Alonso-Basanta M et al . Predictors of hearing loss after gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: age, cochlear dose, and tumor coverage. Neurosurgery. (2011) 69:605–14. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31821a42f3

60.

McWilliams W Trombetta M Werts ED Fuhrer R Hillman T . Audiometric outcomes for acoustic neuroma patients after single versus multiple fraction stereotactic irradiation. Otol Neurotol. (2011) 32:297–300. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318206fdde

Summary

Keywords

acoustic neuroma, vestibular schwannoma, hearing preservation, radiotherapy, gamma knife

Citation

Musleh A and Alshehri S (2025) Hearing preservation of post-radiotherapy for acoustic neuroma—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1647374. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1647374

Received

15 June 2025

Accepted

23 September 2025

Published

13 October 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Hubertus Axer, Jena University Hospital, Germany

Reviewed by

Jun He, Central South University, China

Fabricio Garcia-Torrico, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Bolivia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Musleh and Alshehri.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Alshehri, saaalshehri@kku.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.