Abstract

Anosognosia, or unawareness of disease, is a common clinical feature in neurodegenerative dementias. Frequently reported as an early symptom, its presence has been associated with faster dementia progression and greater cognitive impairment. Similarly, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) encompass non-cognitive behavioral and psychiatric disturbances that commonly affect individuals with dementia. Both aosognosia and NPS are clinically relevant in neurodegenerative diseases due to their significant implications in disease management and caregiver burden. In this narrative review, we examined studies investigating the direct relationship between anosognosia and NPS across different neurodegenerative dementias, including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and α-synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB). A total of 46 studies were identified, the majority of which focused on AD. Despite considerable heterogeneity in participant selection, assessed domains, and measures of anosognosia and NPS investigated, consistent association emerged between anosognosia and global NPS scores as well as individual symptoms. Across studies, the most common finding was a negative association between anosognosia and depression and a positive association between anosognosia and apathy. Possible underlying mechanisms and shared neuroanatomical substrates of these findings are discussed. The review provides a deepened insight into key symptoms with critical implications for dementia research, clinical management, and caregiving strategies.

1 Introduction

Anosognosia, also referred to as loss of insight, unawareness, or impaired self-awareness, is defined as the lack of recognition for a wide range of neurological and neuropsychological disturbances (1, 2). It is frequent in neurodegenerative dementias and can differentially affect the cognitive, behavioral, or functional impairments occurring in these diseases (3). It is estimated to affect from 20% to as many as 80% of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia (2, 4, 5), with higher proportions observed when milder forms of unawareness are considered (6). Such variability is likely related to differences in assessment methods and disease severity examined across cohorts. Although precise prevalence estimates stratified by method or stage are still lacking, anosognosia is widely recognized as a relevant symptom across the whole dementia continuum. It generally worsens with dementia progression, suggesting an association with disease severity (7, 8), although some studies have reported mixed results (9, 10), or no change (11–14). Recent studies have shown that the disorder can already manifest in the predementia stages, such as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (15), or even years before symptom onset in AD mutation carriers (16). Notably, unawareness of cognitive deficits has been identified as a predictor of disease progression along the dementia continuum, from cognitively normal status to MCI and, ultimately, to AD dementia (8, 17). Accordingly, it has been proposed that reduced awareness and underreporting of cognitive deficits may serve as an early clinical marker of dementia, more specific than Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD), supporting the usefulness of monitoring awareness in the clinical setting (18).

While anosognosia has been primarily studied in AD, it is also recognized as a significant feature of other neurodegenerative diseases. It is frequently reported in the Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) spectrum, where it can affect up to 75% of cases and represents a hallmark feature of the behavioral variant (bvFTD) (19). Despite having been removed from the current clinical criteria (20, 21), loss of insight is again reported as a supportive feature in proposed research criteria for prodromal FTD (22). Furthermore, anosognosia has also been documented in individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) exhibiting cognitive or behavioral disturbances, even in the absence of a full ALS-FTD diagnosis (23). Some studies have also reported anosognosia in α-synucleinopathies, including both Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD). In DLB, unawareness of cognitive decline has been observed, though its exact prevalence remains unclear, and its presence may be influenced by AD co-pathology (24). In PD, anosognosia has been documented mostly in subjects with cognitive impairment (i.e., PD-MCI and PD dementia - PDD) and has been shown to worsen over time (25). Additionally, impaired awareness for motor symptoms has been reported in PD (26).

The presence of anosognosia in dementia has profound implications for patient care, as it can reduce adherence to treatment, impair the ability to recognize potentially harmful situations, and hinder compensatory strategies (2). These risks are even more critical in young-onset dementias, where patients are more likely to remain employed, make autonomous decisions, and care for their families (6). Overall, reduced awareness has been linked to greater caregiver burden and lower quality of life (2, 27), underscoring the need for a deeper understanding of this symptom to improve patient management.

Different methods have been used to measure anosognosia, which are commonly classified into three broad approaches (28). A first method, commonly referred to as clinician rating, is based on the judgment of the clinician who rates the patient’s level of awareness along an ordinal scale, following structured or unstructured interviews with the patient and the caregiver(s). The second method, patient-informant discrepancy, is based on the calculation of discrepancy scores of questionnaires completed by the patient and their caregiver, that asks identical questions about the patient’s functions (29). The Anosognosia Questionnaire-Dementia (AQ-D) (30) and the Everyday Cognition (ECog) scale (31) are examples of questionnaires used with this purpose. Most commonly used questionnaires also categorize different domains of anosognosia, as loss of insight may concern not only cognitive deficits but also behavioral disturbances, personality changes and loss of social cognition. Discrepancy scores can be treated as a continuum from full awareness to complete anosognosia, or cut-off values can be defined to classify subjects as aware or unaware. Clinician ratings and patient-informant discrepancies are frequently used in clinical settings to assess anosognosia in an offline way (32). The third method, performance discrepancy, compares the patient’s actual (objective) performance on a given neuropsychological test with their self-estimated performance. Variants of this approach have traditionally been used to assess metacognition in healthy subjects but are increasingly applied to measure online and immediate awareness in patients with dementia (33–36). At present, there is no consensus on the most accurate method to detect and characterize anosognosia, resulting in the use of different instruments across studies, sometimes also in combination. In the present review, we therefore consider the literature broadly, without focusing on a single method.

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between anosognosia and cognitive features, consistently finding that greater unawareness is associated with poorer performance on memory and/or executive function tests (5, 29, 37, 38). In contrast, the association between anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), including potential causal links and underlying neurobiological mechanisms, remains controversial and less clearly defined. NPS encompass a wide range of non-cognitive behavioral and psychiatric manifestations (39), including but not limited to depression, apathy, affective dysregulation, impulsivity, psychotic symptoms, and, less commonly, sleep and appetite disturbances. These symptoms frequently arise in dementia, from prodromal to advanced stages (40), with prevalence rates reaching up to 97% across the dementia spectrum (41). Their expression can vary across different forms of dementia, with depression, hallucinations, and delusions being more typical of AD and DLB, whereas disinhibition and compulsions more frequent in FTD (42–44). The implications of NPS are profound, as they can lead to increased caregiver burden and reduced quality of life (45–47). They have also been associated with faster progression of cognitive decline in affected individuals and worse disease prognosis (48, 49). NPS are primarily reported by caregivers and are commonly assessed using various questionnaires, among which one of the most common is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (50). Understanding their expression is therefore crucial to inform both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions aimed at improving overall patient care and alleviating caregiver burden (51).

This narrative review aims to consolidate recent evidence on the interplay between anosognosia and NPS, identify gaps in current knowledge, and highlight potential directions for future research to inform both the scientific understanding and clinical management of these pivotal aspects of dementia.

2 Methods

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were selected based on predefined inclusion criteria: (i) studies focusing on the relationship between awareness and neuropsychiatric symptoms; (ii) studies focusing on neurodegenerative dementias, including AD, FTD, and α-synucleinopathies (i.e., PD, DLB); (iii) studies available in English and with full-text access. Reviews and meta-analyses were not directly included but were examined for relevant references. Additionally, relevant publications were identified and added through manual screening of the bibliographies of full-text articles. Studies were excluded if they assessed anosognosia and/or NPS in isolation without investigating their relationship, or if the study population was not sufficiently described or classified to allow reliable inferences. We also excluded animal-based studies, case reports, and clinical trials, as well as non-original publication (editorials and letters in response to previous articles), conference abstracts, and proceedings.

2.2 Search strategy

We performed a literature search of the MEDLINE/PubMed and Web of Science databases to identify eligible published articles from their inception to May 2, 2024. In order to capture the extent of the literature, a range of search terms were used in various combinations. The terms “awareness,” “anosognosia,” “unawareness,” and “self-insight” were used to capture the principal topic of anosognosia, while “dementia” and “neurodegenerative” to denote the group of diseases of interest. Finally, “neuropsychiatric,” “behavioral,” “behavioral,” “depression,” “apathy,” and “psychosis” were added to capture the association with NPS. We filtered the research by excluding reviews, animal studies, and articles not published in English. Retrieved articles were imported into the Rayyan Intelligent Systematic Review Tool, to remove duplicates. Articles were first screened by titles and abstracts, then the full texts of selected studies were evaluated, excluding non-eligible articles as per established criteria. Any uncertainty in the selection was discussed with the senior authors (MT, GZ, PV) until a consensus was reached.

3 Results

The database search identified a total of 2,264 articles. We first excluded duplicates, as well as studies published in non-English languages or those without available abstract/full text. Titles and abstracts of the remaining 803 studies were reviewed, and 729 more articles were excluded based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Seventy-four articles underwent full-text review, and a final total of 46 studies were deemed eligible (Figure 1). Among the included articles, 40 studies examined the relationship between anosognosia and NPS in AD, 7 in PD, and 2 in FTD and related syndromes. No studies specifically focused on DLB. Table 1 provides a summary of all included studies, detailing participant characteristics, median age (when available), the domains of NPS investigated, NPS and awareness assessment tools, and key findings. To improve the consistency of reported findings, in this review we grouped NPS into six broad domains that emerged from the included studies and reflect clinical plausibility: (i) depression; (ii) apathy; (iii) affective dysregulation symptoms (i.e., mania, euphoria, pathological laughing, irritability); (iv) impulse dyscontrol symptoms (i.e., disinhibition, agitation, aberrant motor behavior, inattention, tension); (v) psychotic symptoms (i.e., hallucinations, delusions); and (vi) sleep and appetite disturbances. Although this grouping is not based on a universally established consensus, it provides a systematic framework to examine heterogeneous findings across studies. In the included studies, some authors specifically investigated anosognosia with respect to a particular cognitive or behavioral domain (e.g., unawareness of memory loss, unawareness of behavioral disturbances). In these cases, we explicitly report the domain-specific form of anosognosia. Otherwise, the term “anosognosia” is used alone to denote a generalized lack of disease awareness.

Figure 1

Flowchart of study selection process.

Table 1

| Study | Participants (median age, years) | Domains of NPS | NPS assessment | Awareness assessment | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanzio et al. (83) | 29 AD (75) | Apathy impulse dyscontrol | AES DS | AQ-D | Higher apathy and disinhibition in unaware relative to aware subjects. |

| Castrillo Sanz et al. (4) | 127 AD (80) | Global NPS | NPI-Q | CIRS | High NPI-Q score predicts the presence of anosognosia. |

| Castro et al. (87) | 52 PD (60.7) | Global NPS depression | NPI HADS BDI | Subjective complaints | Higher depression and NPS in subjects with subjective cognitive complaints. |

| Chen et al. (66) | 55 AD (76.6) | Depression apathy | CSDD AES | GRAD Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Lower depression in subjects with anosognosia; higher apathy in subjects with anosognosia; higher depression predicts lower anosognosia. |

| Cines et al. (76) | 104 AD (77.5) | Depression | GDS | ARS | Lower depression predicts anosognosia; higher anosognosia predicts lower depression. |

| Clare et al. (58) | 12 AD (71) | Global NPS depression | CAPE HADS | MARS | Positive correlation between anosognosia and global CAPE score; negative correlation between anosognosia and subjects’ depression; positive correlation between anosognosia and caregivers’ depression. |

| Conde-Sala et al. (52) | 164 AD (77.6) | Global NPS depression apathy impulse dyscontrol affective dysregulation appetite | NPI GDS | AQ-D | Higher NPI score in subjects with high AQ-D score relative to low AQ-D score; lower GDS score in subjects with high AQ-D score relative to low AQ-D score; higher apathy, agitation, disinhibition, AMB, irritability, and appetite scores in subjects with high AQ-D score relative to low AQ-D score; in the high AQ-D score group, positive correlation between anosognosia and agitation, disinhibition, AMB, irritability, euphoria, appetite and negative correlation between anosognosia and depression; higher NPI and lower GDS scores predict severe anosognosia. |

| Derouesné et al. (69) | 88 AD (73.2) | Depression apathy | ZD, ZA PBQ | Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Negative correlation between anosognosia and anxiety; positive correlation between anosognosia and apathy. |

| Gilleen et al. (67) | 27 AD (82.4) | Depression | BDI-II | SUMD SAI-E MARS PCRS DEX | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression. |

| Horning et al. (77) | 107 AD (82.4) | Depression apathy | NRS AES | NRS (Insight) | Higher anosognosia predicts lower depression and anxiety and higher apathy, after controlling for global cognition. |

| Jacus (63) | 20 AD, 20 MCI (80.5, 78.5) | Depression apathy | BDI-II STAI AES | PCRS SCQ | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression and anxiety; positive correlation between anosognosia and apathy; higher presence of low depression score and high apathy score among subjects with high anosognosia score. |

| Kashiwa et al. (7) | 84 AD (75.5) | Depression impulse dyscontrol | NPI GDS | Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression; positive correlation between anosognosia and disinhibition score. |

| Kelleher et al. (73) | 75 MCI (57 AD) (76.4) | Depression | NPI ADS | AD8 discrepancy | Higher depression and anxiety in subjects with preserved insight relative to subjects without preserved insight; higher depression and anxiety predict lower insight. |

| Lacerda et al. (57) | 89 AD (78) | Global NPS depression | NPI CSDD | ASPIDD | Positive correlation between anosognosia and NPI score and depression. |

| Lehrner et al. (74) | 280 SCD (64) 181 naMCI (67) 137 aMCI (70) 43 AD (74) 28 PD (67) 58 PD-naMCI (69) 29 PD-aMCI (69) 211 controls (66) | Depression | BDI | Complaint-performance discrepancy | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression in aMCI, naMCI, SCD, PD, PD-naMCI, and controls. No significant association in AD and PD-aMCI. |

| Lopez et al. (78) | 181 AD (71.4) | Depression psychosis | Psychiatric assessment | Clinician rating | No association. |

| Mak et al. (79) | 36 AD, 21 MCI (72.6, 69.2) | Depression apathy | GDS AES | AQ-D | Higher apathy predicts anosognosia (AQ-D total and IF only). |

| Marino et al. (88) | 58 PD (not available) | Depression | GDS | PDQ-39 (perceived cognition) | Positive correlation between perceived cognition and depression. |

| Migliorelli et al. (30) | 73 AD (72.9) | Depression affective dysregulation | HAM-D BMS PLACS | AQ-D | Lower dysthymia in subjects with anosognosia; higher mania and pathological laughing score in subjects with anosognosia. |

| Mikos et al. (91) | 37 PD (69) | Apathy | AES | Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Correlation between higher apathy and both greater under- and over-reporting. |

| Nakaaki et al. (64) | 42 AD (71.4) | Depression | Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression in AD | SMQ (discrepancy score) | Higher discrepancy score in subjects without depression relative to subjects with depression. |

| O’Keeffe et al. (36) | 14 FTD, 11 CBD, 10 PSP (not available) | Depression | HADS MET | Composite score for metacognitive awareness, online emergent awareness, online anticipatory awareness | Negative correlation between online anticipatory awareness and depression; positive correlation between metacognitive awareness and empathy. |

| Oba et al. (65) | 118 AD, 47 MCI (79.5, 76.2) | Depression | GDS | Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Lower depression predicts anosognosia. |

| Orfei et al. (89) | 197 PD, 141 MCI-PD, 47 PPD (62.6, 68.6, 73.4) | Depression | BDI | AQ-D | Negative correlation between depression and anosognosia (AQ-D total and IF only). |

| Reed et al. (81) | 57 AD | Depression | Clinician rating | Clinician rating | No association. |

| Satler and Tomaz (53) | 21 AD (78.6) | Global NPS depression | NPI CSDD | AQ-D | Higher NPI score predicts higher anosognosia (AQ-D IF). |

| Sato et al. (59) | 143 AD (72.1) | Global NPS | NPI | AQ-D | Higher NPI score predicts higher anosognosia (AQ-D BEH). |

| Seltzer et al. (71) | 36 AD (74.6) | Depression Affective Dysregulation | CSDD Subject and informant ratings | Subject-informant discrepancy scores | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression (caregiver rating); positive correlation between anosognosia and irritability (caregiver rating). |

| Sevush and Leve (72) | 128 AD (69.2) | Depression | Subject and informant ratings | Clinician rating | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression. |

| Smith et al. (68) | 23 AD (75.3) | Depression | GDS | AII | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression. |

| Sousa et al. (13) | 69 AD (76.8) | Apathy impulse dyscontrol | NPI CSDD | ASPIDD | Positive correlation between anosognosia and apathy and agitation scores. |

| Spalletta et al. (54) | 103 AD, 52 a-MCI, 54 md-MCI (76.3, 71.4, 71.2) | Global NPS apathy impulse dyscontrol affective dysregulation | NPI | AQ-D | Positive correlation between anosognosia (i.e., AQ-D total, AQ-D IF, AQ-D BEH) and NPI score, apathy, agitation, and AMB; positive correlation between anosognosia (i.e., AQ-D total, AQ-D BEH) and irritability. |

| Starkstein et al. (82) | 170 AD (70.5) | Depression apathy affective dysregulation psychosis | HAM-D AS BMS PLACS DPS | AQ-D | Higher psychosis and apathy and lower depression predict anosognosia for cognitive deficits; higher mania and pathological laughing score predict anosognosia for behavioral problems. |

| Starkstein et al. (90) | 33 AD, 33 PDD (70.3, 71) | Depression | HAM-D | AQ-D | Higher depression in PDD relative to AD; higher anosognosia in AD relative to PD. |

| Starkstein et al. (80) | 750 AD (71.6) | Depression impulse dyscontrol | HAM-D DS | AQ-D | Positive correlation between anosognosia and disinhibition. |

| Starkstein et al. (84) | 77 AD (71.5) | Apathy | AS | AQ-D | Anosognosia at baseline predicts higher apathy score at follow-up. |

| Tondelli et al. (6) | 91 EOD, 57 LOD (64.9, 78.6) | Global NPS apathy | NPI | CIRS | Early anosognosia predicts NPI score in all subjects and EOD subgroup; positive correlation between anosognosia and apathy score; anosognosia predicts apathy score in EOD subgroup. |

| Troisi et al. (70) | 42 AD (76.2) | Depression | HAM | HAM-I | Higher depression (psychic subscore, not somatic subscore) in subjects with higher awareness. |

| Turró-Garriga et al. (85) | 177 AD (77.8) | Impulse dyscontrol psychosis | NPI | AQ-D | Disinhibition score predicts persistence of anosognosia between baseline and follow-up; delusion score predicts incidence of anosognosia at follow-up. |

| van Vliet et al. (75) | 142 YOAD, 126 LOAD (61.6, 79.1) | Depression | NPI | GRAD | Negative correlation between anosognosia and depression, more in YOAD than in LOAD. |

| Verhülsdonk et al. (55) | 47 AD (76.5) | Global NPS depression | NPI GDS NOSGER | AQ-D | Positive correlation between anosognosia and NPI score; positive correlation between anosognosia and depression reported by informants (NPI-depression score, NOSGER mood), no correlation between anosognosia and depression reported by subjects. |

| Vogel et al. (56) | 321 AD (76.2) | Global NPS depression | NPI-Q CSDD | ARS MDR | Higher NPI-Q score (total severity score and distress score) in subjects with no insight relative to subjects with full insight classified through ARS; positive correlation between NPI-Q score and MDR score. |

| Wang et al. (61) | 237 MCI (132 A+) (73) | Global NPS apathy impulse dyscontrol affective dysregulation psychosis | NPI | ECog | Higher NPI total score, agitation and disinhibition scores in unaware subjects; earlier onset of NPS (i.e., apathy, agitation, disinhibition, AMB, irritability, delusion, and hallucination) in unaware subjects relative to aware ones. |

| Yoo et al. (86) | 340 PD (67.2) | Global NPS depression | NPI BDI | Complaint-performance discrepancy | Higher NPI total score in subjects with cognitive underestimation; lower depression in subjects with anosognosia. |

| Yoon et al. (60) | 616 early onset AD (62.6) | Global NPS impulse dyscontrol psychosis sleep, appetite | NPI | Clinician rating | Higher NPI score in subjects with anosognosia compared to subjects without anosognosia, only for CDR 0.5–1; higher agitation, AMB, delusion, hallucination, sleep, and appetite scores in subjects with anosognosia. |

| Zilli and Damasceno, (62) | 21 AD (72.4) | Global NPS depression | NPI CSDD | SCQ DIS | No association. |

Key findings of identified studies.

Studies are presented in alphabetical order according to first authors’ names. AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; AD8: Eight-item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia; ADS: Anxiety Depression Scale; AES: Apathy Evaluation Scale; AII: Assessment of Impaired Insight; AMB: Aberrant Motor Behavior; AQ-D: Anosognosia Questionnaire for Dementia (IF: Intellectual Functions; BEH: Behavior); ARS: Anosognosia Rating Scale; AS: Apathy Scale; ASPIDD: Anosognosia Scale for Psychosis and Inhibitory Dysregulation in Dementia; A+: amyloid positive; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory – II version; BMS: Bech Mania Scale; CAPE: Behavior Problems Checklist of the Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly; CBD: Corticobasal Degeneration; CIRS: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DEX: Dysexecutive Questionnaire; DIS: Denial of Illness Scale; DPS: Dementia Psychosis Scale; DS: Disinhibition scale; ECog: Everyday Cognition Scale; EOD: Early-Onset Dementia; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; GRAD: Guidelines for the Rating of Awareness Deficits; HAM: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D: depression item; HAM-I: insight item); HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LOAD: Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease; LOD: Late-Onset Dementia; MARS: Memory Awareness Rating Scale; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment (a-MCI: amnesic MCI; na-MCI: non-amnesic MCI; md-MCI: multidomain-MCI); MDR: Memory Discrepancy Rating; MET: Measure of Empathic Tendency; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPI-Q: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; NPS: Neuropsychiatric symptoms; NOSGER: Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients; NRS: Neurobehavioral Rating Scale; PBQ: Psychobehavioural Questionnaire; PCRS: Patient Competency Rating Scale; PD: Parkinson’s Disease; PDD: Parkinson’s Disease Dementia; PDQ-39: Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39; PLACS: Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale; PSP: Progressive Supranuclear Palsy; SAI-E: Scale for Assessment of Insight-Extended; SCD: Subjective Cognitive Decline; SCQ: Self-Consciousness Questionnaire; SMQ: Short Memory Questionnaire; STAI: State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; SUMD: Scale for the Unawareness of Mental Disorder; YOAD: Young-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease; ZA: Zung Self-Rating Scales for Apathy; ZD: Zung Self-Rating Scales for Depression.

3.1 Anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease

3.1.1 Global measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms

The literature exploring the relationship between anosognosia and NPS in AD is extensive and relatively well established.

First, a positive correlation between anosognosia—measured either as a continuous variable or as a categorical presence/absence using the AQ-D—and the NPI total score has been consistently reported (52–55). The same association has been observed when anosognosia was assessed using alternative instruments, such as the Anosognosia Rating Scale Memory Discrepancy Rating (4), the Cognitive Insight Rating Scale (56), the Anosognosia Scale for Psychosis and Inhibitory Dysregulation in Dementia (57) and the Memory Awareness Rating Scale (58). Notably, Sato et al. (59) found in a large group of subjects (n = 143 AD) that this relationship was specific to anosognosia for behavioral complaints (i.e., AQ-D BEH), whereas anosognosia for cognitive deficits (i.e., AQ-D IF) was not significantly associated with NPS.

In early-onset AD, Yoon et al. (60) reported an association between anosognosia and NPS only in individuals with MCI or mild dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, CDR = 0,5 or 1), but not in more advanced stages (CDR = 2), suggesting that as dementia progresses, NPS may emerge independently of anosognosia. In addition, Tondelli et al. (6), compared early-onset (EOD) and late-onset dementia (LOD), and found a significant positive correlation between anosognosia and NPS only in EOD. Further supporting this pattern, a longitudinal study in MCI populations showed that individuals with anosognosia had higher NPI global scores at baseline and experienced an earlier onset of NPS over time compared to subjects with preserved awareness (61).

In contrast, Zilli and Damasceno did not observe this association when measuring anosognosia with Self-Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ) and Denial of Illness Scale (DIS) in a small cohort of subjects (n = 21 AD) (62).

3.1.2 Depression

When examining specific neuropsychiatric symptoms, most studies have reported an inverse correlation between anosognosia and depressive symptoms. In other words, individuals who are more aware of their deficits tend to experience more depressive symptoms than those who are unaware (7, 52, 63–72). This relationship has been observed not only in AD dementia but also in MCI and SCD individuals, regardless of amyloid status (73, 74), and has been shown to be stronger in young-onset AD dementia relative to late-onset AD (75). Cines et al. (76) demonstrated that depression can both predict and be predicted by anosognosia in a cross-sectional design on 104 AD individuals. Furthermore, a longitudinal study by Horning et al. (77), found that the levels of awareness at baseline in a sample of 107 AD predicted subsequent development of depressive mood and anxiety, even after controlling for global cognition.

Three of these studies analyzed the concept of depression along with anxiety, which is frequently interpreted as a symptom accompanying depression, and found that increased anosognosia was associated with lower anxiety (63, 73, 77). One study by Derouesné et al. (69) has reported an association between anosognosia with anxiety and not with depression.

It is also important to note that anosognosia can also manifest as lack of awareness of depressive symptoms, a phenomenon referred to as affective anosognosia. For example, two studies reported a positive correlation between anosognosia and depression only when depressive symptoms were assessed by an informant, not by the patient (55, 58). The authors suggested that unaware individuals may appear less depressed simply because they under-recognize and under-report their own depressive symptoms (55).

In contrast, seven studies failed to find an association between anosognosia and depression (53, 56, 62, 78–81). For instance, Lopez et al. (78) relied on psychiatric assessments and clinician ratings rather than standardized questionnaires for measuring NPS and anosognosia. Migliorelli et al. (30) only demonstrated a significant association between increased anosognosia and lower dysthymia, instead of depression.

Only a few studies have reported an inverse association, such that anosognosia was positively correlated with depression (55, 57, 58). More specifically, Lacerda et colleagues (57) showed a positive correlation between anosognosia and both awareness for emotional state and social functioning, whereas two other studies reported this positive correlation only when depression was measured through caregivers (55, 58). Finally, some authors proposed a differential model in which depressive symptoms are negatively related to unawareness for cognitive deficits (i.e., AQ-D IF), but not to unawareness of behavioral symptoms (66, 82). This interpretation underscores the multifaceted nature of anosognosia, suggesting that different domains of unawareness may have distinct relationships with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms.

3.1.3 Apathy

Another significant association is the one between increased levels of anosognosia and greater apathy, observed both in MCI and dementia stages (13, 52, 54, 63, 66, 69, 79, 83, 84). Similarly to depression, apathy appeared to be more strongly associated with anosognosia for cognitive deficits (i.e., AQ-D IF) than with anosognosia for behavioral disturbances (79, 82). Moreover, this association remained significant even after controlling for global cognition (77). Longitudinal studies have also demonstrated that both apathy and anosognosia tend to worsen over time, and that baseline anosognosia predicts an earlier onset and greater severity of apathy at follow-up (61, 84).

When distinguishing between EOD and LOD, including but not limited to AD, the positive association between anosognosia and apathy has been documented only in EOD subjects (6).

3.1.4 Affective dysregulation symptoms

A more limited number of studies have investigated the association between anosognosia and affective dysregulation symptoms, including mania, euphoria, pathological laughing, and irritability. These studies have consistently reported higher scores for these symptoms in individuals with anosognosia compared to those who were aware of their deficits (30, 52, 54, 71, 82), not only in the dementia stages but also in MCI individuals (61). More specifically, Starkstein et al. (82) observed that this association was significant for mania and pathological laughing scores only when considering anosognosia for behavioral disturbances (i.e., AQ-D BEH), rather than anosognosia for cognitive deficits.

3.1.5 Impulse dyscontrol symptoms

Impulse dyscontrol symptoms, including disinhibition, agitation, aberrant motor behavior (AMB), inattention, and tension, have been found to be positively correlated with anosognosia (7, 13, 52, 54, 60, 80, 83, 85), and this association has also been observed in individuals with MCI (61). Moreover, longitudinal evidence has suggested that baseline levels of agitation and AMB may predict the later emergence of anosognosia (54).

3.1.6 Psychotic symptoms

The presence of psychotic symptoms, namely delusions and hallucinations, has also been linked to anosognosia (60, 61, 82, 85). In a longitudinal study, delusional symptoms at baseline were found to predict the persistence of anosognosia at follow-up (85). Conversely, in individuals with MCI, baseline anosognosia was associated with an earlier onset of both delusion and hallucination over time (61). However, one study with a small sample size failed to confirm this association (78).

3.1.7 Sleep and appetite disturbances

Finally, few studies reported an association between higher levels of anosognosia and greater disruption in sleep habits and patterns (60), as well as appetite disturbances (52, 60). These findings suggest that anosognosia may be linked to broader homeostatic and circadian regulatory impairments, although further research is needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

3.2 Anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in frontotemporal dementia

Despite being regarded as a core symptom of FTD, particularly its behavioral variant (bvFTD), anosognosia and its association with neuropsychiatric symptoms have been less extensively explored in this form of dementia. O’Koeffe et al. (36) distinguished three different facets of awareness (namely metacognitive, emergent, and anticipatory awareness) in subjects with FTD, Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD) and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP). They found that FTD individuals exhibited significantly higher levels of anosognosia compared to both other patient groups and controls, and that anticipatory anosognosia (i.e., the inability to predict difficulties in performing a task because one’s own deficits) was negatively correlated with depression while metacognitive awareness (i.e., the declarative knowledge about one’s own abilities) was positively correlated with empathy. The study of Tondelli et al. (6), which investigated differences between EOD and LOD and also included 28 FTD subjects, demonstrated that anosognosia was more frequent in bvFTD, as well as in the behavioral/dysexecutive variant of AD. This study also found that only apathy was positively associated with anosognosia, independent from age and clinical diagnosis. Specifically, higher levels of unawareness at baseline were linked to the subsequent development of apathy.

3.3 Anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in α-synucleinopathies

Similar to FTD, the investigation of anosognosia and NPS in α-synucleinopathies remains scarce. A few studies on PD demonstrated that individuals with PD who exhibited greater anosognosia for cognitive difficulties had lower scores on depression scales, consistent with findings in AD (74, 86). In particular, Lehrner et al. (74) showed this association in PD without cognitive impairments and in PD with non-amnesic MCI (not in the small group of PD with amnesic MCI). However, in contrast to AD, higher NPI global scores were observed in individuals with cognitive underestimation (i.e., the tendency to overestimate cognitive difficulties, as opposed to anosognosia) (86). Two additional studies, although not directly measuring anosognosia, reported increased depressive symptoms in PD subjects who expressed greater subjective concerns regarding their cognitive performance (87, 88). Concurrently, Orfei et al. (89) observed a negative association between anosognosia for cognitive impairment (i.e., AQ-D IF) and depression in both PD-MCI and PD without cognitive complaints, though this association was not observed in PDD, despite increasing levels of anosognosia in PD-MCI and PDD, respectively. Starkstein et al. (90) found that, while not directly assessing the relationship between anosognosia and depression in AD and PDD individuals, AD subjects exhibited increased levels of anosognosia and decreased levels of depression, while PDD subjects showed increased levels of depression and decreased levels of anosognosia.

Regarding the relationship with apathy, Mikos et al. (91) documented that PD subjects with inaccurate self-reporting of emotional expressivity—whether over-reporting or under-reporting—had increased levels of apathy, which supports the emotion hypothesis of anosognosia, suggesting that apathy diminished concern about deficits, which in turn leads to inaccurate self-reporting.

No studies have directly examined the association between anosognosia and NPS specifically in DLB. However, it is worth noting that some of the articles discussed in Section 3.1 included individuals with MCI, particularly multi-domain MCI, regardless of amyloid status. Therefore, potential diagnoses other than AD, such as DLB, may be relevant in those cohorts. Specifically, these studies confirmed increased levels of depression and anxiety in individuals with decreased anosognosia (73) and higher NPI total score, agitation, and disinhibition in subjects with greater anosognosia (61). Additionally, Tondelli et al. (6) reported a positive correlation between anosognosia and apathy score in a cohort of EOD, including 12 individuals with DLB.

4 Discussion

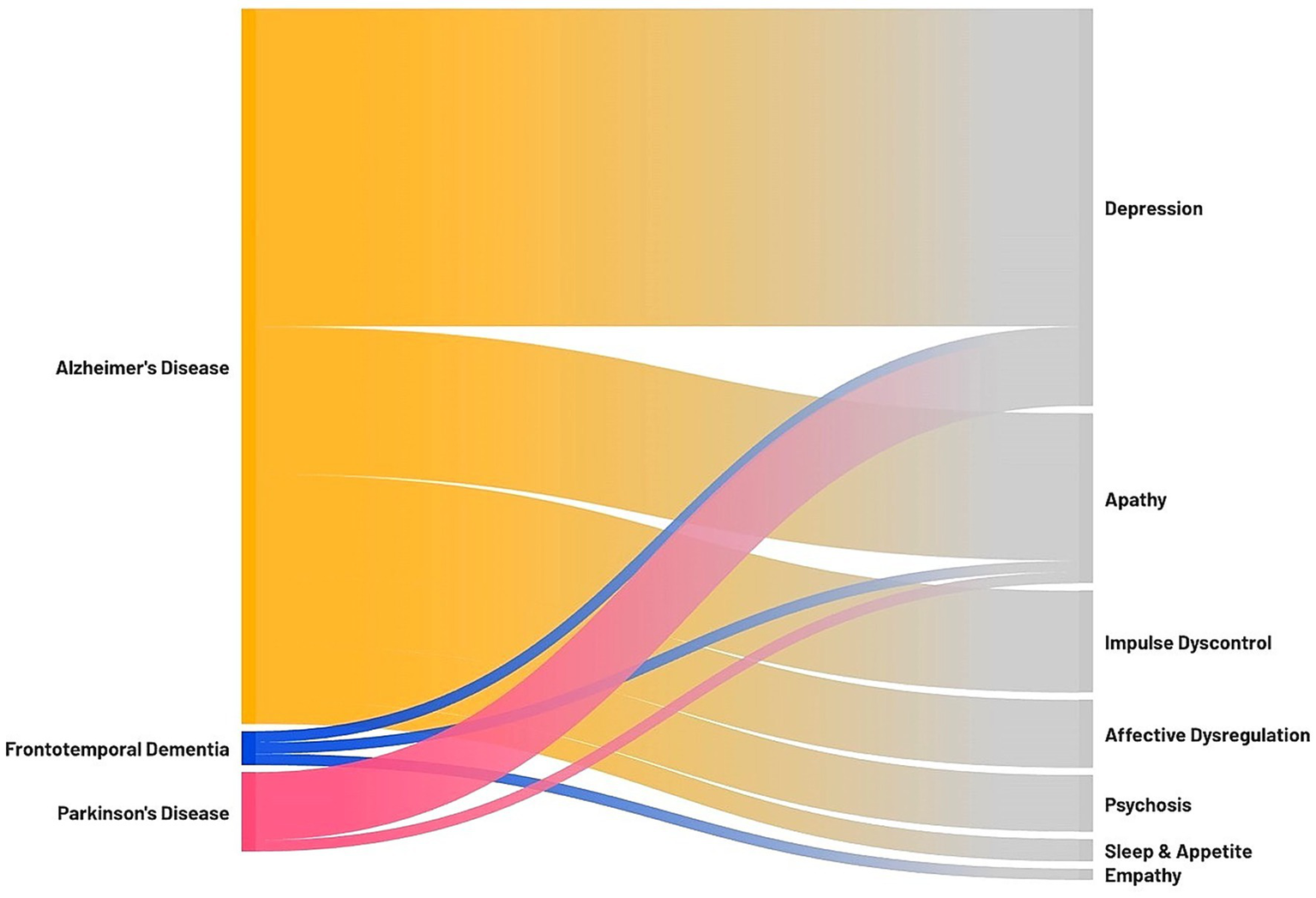

This narrative review provides an overview of the current evidence on the association between anosognosia and NPS, two common and critical symptoms in neurodegenerative dementias, which substantially impact patient management and quality of life. The findings highlight a complex interplay between these two clinical features, with significant variability depending mostly on the specific domains of anosognosia and NPS under investigation, as well as the neurodegenerative condition examined. The Sankey diagram reported in Figure 2 summarizes the findings of this review, illustrating which associations between NPS and anosognosia have been investigated in each neurodegenerative disease.

Figure 2

Sankey diagram illustrating the association between anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative dementias. On the left, the neurodegenerative diseases investigated in the review with significant findings; on the right, the neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with anosognosia. The thickness of each connection represents the number of studies focusing on a specific association (i.e., the association between anosognosia and depression was assessed in 28 studies on AD, 1 study on FTD, and 6 studies on PD; the association between anosognosia and apathy was assessed in 13 studies on AD, 1 study on FTD, and 1 study on PD; the association between anosognosia and impulse dyscontrol symptoms was assessed in 9 studies on AD; the association between anosognosia and affective dysregulation symptoms was assessed in 6 studies on AD; the association between anosognosia and psychosis was assessed in 5 studies on AD; the association between anosognosia and sleep and appetite was assessed in 2 studies on AD; the association between anosognosia and empathy was assessed in 1 study on FTD).

The most substantial body of literature concerns AD, where anosognosia was initially characterized and has since been the subject of extensive investigation. In AD, a consistent positive association has been observed between anosognosia and global scores of NPS, pointing to a potential causal link and a shared neurobiological substrate underlying their co-occurrence (54, 61). Conversely, in FTD, studies exploring the relationship between anosognosia and NPS remain scarce and are even absent in the linguistic variants of FTD. The existing articles suggest a higher prevalence of NPS in unaware subjects (6, 36), but their limited number and the heterogeneity of the included patient populations prevent definitive conclusions. Importantly, it could also be debated whether the lack of awareness of behavioral symptoms in FTD represents true anosognosia or rather stems from the loss of social manner and decorum that characterize these patients, as part of a broader disinhibition syndrome. In other words, individuals with FTD may appear unaware of their behavior, yet they might be indifferent to it because of the absence of recognition regarding the social inappropriateness of their actions. Similarly, evidence regarding α-synucleinopathies remains scarce and inconclusive. Two studies report, in contrast to AD, higher NPS in PD individuals with cognitive underestimation or subjective complaints (86, 87), while in DLB dedicated studies focusing exclusively on the association between anosognosia and NPS are lacking.

Notably, more informative findings arise from studies that analyze specific NPS domains individually, with particular emphasis on depression and apathy. In AD, the relationship between anosognosia and depression appears to be robustly inverse, with greater awareness of cognitive decline associated with increased depressive symptoms (7, 52, 65, 66, 77, 82). Despite more limited evidence, the same association is suggested in FTD (36) and PD individuals (74, 86–90). Two main hypotheses have been proposed to explain this association. One posits that a depressed mood—characterized by a gloomy perspective on the future and pessimistic ideation about current condition, may lead to a cognitive negative bias, resulting in underestimation of one’s abilities (92). The alternative hypothesis suggests that reduced awareness of one’s deficits may act as a psychological defense mechanism, protecting individuals from emotional distress (92). In essence, the first hypothesis frames depression as a determinant of increased awareness, while the second conceptualizes anosognosia as a protective factor against depression. Interestingly, some studies have reported a negative association between anosognosia and dysthymia, but not with major depressive disorder. This finding has led to the suggestion that major depression may reflect a more biologically driven mood disorder, whereas dysthymia could represent a more reactive emotional response to cognitive decline – particularly in individuals with preserved awareness (71). Additionally, the possibility of affective anosognosia, or a lack of awareness regarding one’s own depressive symptoms, must be considered. In such cases, patients may underreport symptoms, contributing to discrepancies in the observed associations (31). Finally, anosognosia is increasingly recognized as a multidimensional construct, with distinct domains potentially relating differently to NPS. For example, Starkstein et al. (58) proposed that only unawareness of cognitive deficits is associated with depressive symptoms, suggesting that domain-specific distinctions in anosognosia may clarify inconsistent findings. Moreover, empirical evidence indicates that different dimensions of anosognosia are not necessarily interrelated. For instance, unawareness of having a disease has been shown to correlate with anosognosia for apathy, but not with unawareness of depressive symptoms (72). These nuances underscore the need for a more refined conceptual and methodological approach in future research.

In the domain of apathy, anosognosia has been consistently associated with increased apathy severity in both AD (52, 54, 61, 69, 77, 83, 84) and FTD (6). In regard to PD individuals, the association with increased apathy has been shown both for over- and under-reporting of emotional expressivity, suggesting that apathy determines a general reduced concern about one’s own deficits (91). To explain this association, it has been proposed that apathy may contribute to anosognosia through mechanisms such as affective blunting and diminished performance monitoring, whereby cognitive errors lose emotional salience and fail to trigger self-awareness processes (92, 93). Conversely, from a metacognitive perspective, anosognosia may exacerbate apathy by impairing self-reflection and reducing the capacity for goal-directed behavior and motivation, processes that are reliant on intact metacognitive functioning (94). Starkstein et al. (61) further proposed a longitudinal model in which anosognosia and apathy represent distinct but sequential manifestations of progressive frontal lobe dysfunction. According to this framework, anosognosia may emerge early as an initial response to frontal damage, while apathy may develop later as frontal degeneration becomes more widespread. Interestingly, both apathy and anosognosia have been associated to frontal regions: apathy has been related to dorsal lateral and medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (95, 96), while ACC has been involved in the error monitoring processes, which are fundamental for the recognition of one’s cognitive deficits. Thus, ACC dysfunction could be a shared biological hallmark of both apathy and anosognosia (92). Notably, discrepancies in the severity and impact of apathy have been reported across patient subgroups, such as in comparisons between EOD and LOD. Some studies suggest that EOD may be associated with more pronounced apathy, potentially due to the disruption of work, family, and social roles, which may heighten demotivation and disengagement (3).

The literature on other NPS, including affective dysregulation, impulse dyscontrol disorders, and psychosis, is more sparse. However, available evidence suggests a positive association with anosognosia. In particular, unawareness of behavioral symptoms may be a key factor in the emergence of affective dysregulation symptoms (82). The relationship between anosognosia and impulse dyscontrol symptoms supports the involvement of frontal circuits in both phenomena, since frontal regions such as the ACC and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and their connections have been implicated in agitation, AMB, and disinhibition (7, 97, 98) as well as in anosognosia (99) suggesting a common neuroanatomical basis to explain their co-occurrence. Additionally, reduced connectivity in the Default Mode Network (DMN), a brain network involved in self-referential processing, has been associated with both anosognosia (100) and NPS (101), particularly hyperactivity symptoms. A recent review further points to the amygdala and limbic system as crucial hubs in this network, given their role in emotional regulation and behavioral control. The amygdala appears highly vulnerable to neurodegeneration, and its disconnection from OFC and frontal cortices may contribute to disinhibition, impulsivity, and agitation. These converging results suggest a crucial role for the disruption of interconnected frontal and limbic circuits and their interactions with the DMN (102). Finally, a bidirectional relationship between anosognosia and psychosis has been shown, suggesting that deficits in reality monitoring – a cognitive function essential for distinguishing internally generated thoughts from external realit—may underlie both anosognosia and psychotic symptoms (60).

Some limitations should be highlighted and may explain part of the inconsistency across studies. First, there is considerable methodological variability in the assessment of both anosognosia and NPS, particularly in relation to depressive symptoms. Anosognosia extends beyond cognitive deficits to include unawareness for behavioral disturbances, personality changes, and deficits in social cognition. However, the operationalization of this construct is not homogeneous, and appropriate standardized instruments are still needed to capture this complexity. Similarly, the tools used to assess NPS vary widely across studies, contributing to inconsistencies in reported associations. A second limitation concerns sample heterogeneity, including small sample sizes, differences in patient selection, and variability in disease severity (e.g., MCI versus dementia). In particular, many studies on AD relied on clinical criteria without biomarker confirmation, or MCI cohorts without verified underlying AD pathology, thereby introducing additional variability. Finally, the included studies display substantial heterogeneity in design, diagnostic criteria, measurement tools, and sample characteristics. This variability was not systematically controlled for or coded through a formal quality assessment framework (e.g., risk of bias/quality chart), given the narrative design of the present review. This further constrains the interpretability of pooled findings and underscores the need for standardized methodological approaches in future work.

5 Conclusion

This narrative review highlights the complex interplay between anosognosia and NPS across neurodegenerative dementias. While the association with global NPS, depression, and apathy in AD is well-documented, evidence in FTD and α-synucleinopathies, as well as data regarding impulse dyscontrol symptoms, affective dysregulation, and psychosis remains limited and inconclusive. Patient selection criteria and methodological heterogeneity in assessing both anosognosia and NPS represent a major challenge, contributing to variability in findings. Standardized and multidimensional approaches, which extend beyond anosognosia for cognitive deficits to include behavioral and social domains, are needed to clarify the underlying neurobiological mechanisms linking anosognosia to NPS. A better understanding of this relationship is critically needed as it has potential implications for early diagnosis, personalized intervention strategies, and may help improve both patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life in neurodegenerative dementias.

Statements

Author contributions

CG: Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft. PV: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. GZ: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. PV was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, R01 AG061083. MT and GZ are funded by the European Union ERC, UnaWireD, project number 101042625.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the colleagues from the Cognitive Neurology Unit in Modena for the continuous and enriching exchange of ideas, which has greatly contributed to the development of this review. We are also deeply grateful to the patients and their families, whose experiences and perspectives inspire and guide our work.

Conflict of interest

GZ has received speaker honoraria from Ely Lilly.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

References

1.

Prigatano GP . Anosognosia: clinical and ethical considerations. Curr Opin Neurol. (2009) 22:606–11. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328332a1e7

2.

Kaszniak A Edmonds E . Anosognosia and Alzheimer’s disease: behavioral studies In: The study of anosognosia, Ed. Prigatano, George P. (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press) (2010) 189–228.

3.

Ecklund-Johnson E Torres I . Unawareness of deficits in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: operational definitions and empirical findings. Neuropsychol Rev. (2005) 15:147–66. doi: 10.1007/s11065-005-9026-7

4.

Castrillo Sanz A Andrés Calvo M Repiso Gento I Izquierdo Delgado E Gutierrez Ríos R Rodríguez Herrero R et al . Anosognosia in Alzheimer disease: prevalence, associated factors, and influence on disease progression. Neurologia. (2016) 31:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2015.03.006

5.

Orfei MD Varsi AE Blundo C Celia E Casini AR Caltagirone C et al . Anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease: frequency and neuropsychological correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2010) 18:1133–40. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c50

6.

Tondelli M Galli C Vinceti G Fiondella L Salemme S Carbone C et al . Anosognosia in early- and late-onset dementia and its association with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Front Psych. (2021) 12:658934. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.658934

7.

Kashiwa Y Kitabayashi Y Narumoto J Nakamura K Ueda H Fukui K . Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: association with patient characteristics, psychiatric symptoms and cognitive deficits. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2005) 59:697–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01439.x

8.

Hanseeuw BJ Scott MR Sikkes SAM Properzi M Gatchel JR Salmon E et al . Evolution of anosognosia in alzheimer’s disease and its relationship to amyloid. Ann Neurol. (2020) 87:267–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.25649

9.

McDaniel KD Edland SD Heyman A . Relationship between level of insight and severity of dementia in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (1995) 9:101–4. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199509020-00007

10.

Akai T Hanyu H Sakurai H Sato T Iwamoto T . Longitudinal patterns of unawareness of memory deficits in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2009) 9:16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00512.x

11.

Clare L Wilson BA . Longitudinal assessment of awareness in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease using comparable questionnaire-based and performance-based measures: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health. (2006) 10:156–65. doi: 10.1080/13607860500311888

12.

Clare L Nelis SM Martyr A Whitaker CJ Marková IS Roth I et al . Longitudinal trajectories of awareness in early-stage dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2012) 26:140–7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31822c55c4

13.

Sousa MFB Santos RL Nogueira ML Belfort T Rosa RDL Torres B et al . Awareness of disease is different for cognitive and functional aspects in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a one-year observation study. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2015) 43:905–13. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140342

14.

Vogel A Waldorff FB Waldemar G . Longitudinal changes in awareness over 36 months in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. (2015) 27:95–102. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001562

15.

Vannini P Amariglio R Hanseeuw B Johnson KA McLaren DG Chhatwal J et al . Memory self-awareness in the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. (2017) 99:343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.04.002

16.

Vannini P Hanseeuw BJ Gatchel JR Sikkes SAM Alzate D Zuluaga Y et al . Trajectory of unawareness of memory decline in individuals with autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2027472. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27472

17.

Gerretsen P Chung JK Shah P Plitman E Iwata Y Caravaggio F et al . Anosognosia is an independent predictor of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with reduced brain metabolism. J Clin Psychiatry. (2017) 78:e1187–96. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11367

18.

Cacciamani F Tandetnik C Gagliardi G Bertin H Habert MO Hampel H et al . Low cognitive awareness, but not complaint, is a good marker of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2017) 59:753–62. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170399

19.

Muñoz-Neira C Tedde A Coulthard E Thai NJ Pennington C . Neural correlates of altered insight in frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Neuroimage Clin. (2019) 24:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102066

20.

Rascovsky K Hodges JR Knopman D Mendez MF Kramer JH Neuhaus J et al . Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. (2011) 134:2456–77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179

21.

Evers K Kilander L Lindau M . Insight in frontotemporal dementia: conceptual analysis and empirical evaluation of the consensus criterion “loss of insight” in frontotemporal dementia. Brain Cogn. (2007) 63:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.07.001

22.

Barker MS Gottesman RT Manoochehri M Chapman S Appleby BS Brushaber D et al . Proposed research criteria for prodromal behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. (2022) 145:1079–97. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab365

23.

Salah AB Pradat PF Villain M Balcerac A Pradat-Diehl P Salachas F et al . Anosognosia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a cross-sectional study of 85 individuals and their relatives. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2021) 64:101440. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.08.004

24.

Calil V Sudo FK Santiago-Bravo G Lima MA Mattos P . Anosognosia in dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2021) 79:334–42. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x-anp-2020-0247

25.

Maier F Greuel A Hoock M Kaur R Tahmasian M Schwartz F et al . Impaired self-awareness of cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease relates to cingulate cortex dysfunction. Psychol Med. (2023) 53:1244–53. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002725

26.

Maier F Williamson KL Tahmasian M Rochhausen L Ellereit AL Prigatano GP et al . Behavioural and neuroimaging correlates of impaired self-awareness of hypo- and hyperkinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Cortex. (2016) 82:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.05.019

27.

Conde-Sala JL Turró-Garriga O Piñán-Hernández S Portellano-Ortiz C Viñas-Diez V Gascón-Bayarri J et al . Effects of anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms on the quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-month follow-up study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2016) 31:109–19. doi: 10.1002/gps.4298

28.

Clare L Marková IS Roth I Morris RG . Awareness in Alzheimer’s disease and associated dementias: theoretical framework and clinical implications. Aging Ment Health. (2011) 15:936–44. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.583630

29.

Hannesdottir K Morris RG . Primary and secondary anosognosia for memory impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. (2007) 43:1020–30. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70698-1

30.

Migliorelli R Tesón A Sabe L Petracca G Petracchi M Leiguarda R et al . Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: a study of associated factors. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (1995) 7:338–44. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.3.338

31.

Farias ST Mungas D Reed BR Cahn-Weiner D Jagust W Baynes K et al . The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. (2008) 22:531–44. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531

32.

Sunderaraman P Cosentino S . Integrating the constructs of Anosognosia and metacognition: a review of recent findings in dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2017) 17:27. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0734-1

33.

Martyr A Nelis SM Clare L . Predictors of perceived functional ability in early-stage dementia: self-ratings, informant ratings and discrepancy scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2014) 29:852–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.4071

34.

Andrade K Guieysse T Medani T Koechlin E Pantazis D Dubois B . The dual-path hypothesis for the emergence of anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1239057. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1239057

35.

Mimmack KJ Gagliardi GP Marshall GA Vannini P Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Measurement of dimensions of self-awareness of memory function and their association with clinical progression in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e239964. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9964

36.

O’Keeffe FM Murray B Coen RF Dockree PM Bellgrove MA Garavan H et al . Loss of insight in frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. (2007) 130:753–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl367

37.

Michon A Deweer B Pillon B Agid Y Dubois B . Relation of anosognosia to frontal lobe dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1994) 57:805–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.7.805

38.

Salmon E Perani D Herholz K Marique P Kalbe E Holthoff V et al . Neural correlates of anosognosia for cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. (2006) 27:588–97. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20203

39.

Ruthirakuhan M Guan DX Mortby M Gatchel J Babulal GM . Updates and future perspectives on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2025) 21:e70079. doi: 10.1002/alz.70079

40.

Zhao QF Tan L Wang HF Jiang T Tan MS Tan L et al . The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2016) 190:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069

41.

Pless A Ware D Saggu S Rehman H Morgan J Wang Q . Understanding neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: challenges and advances in diagnosis and treatment. Front Neurosci. (2023) 17:1263771. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1263771

42.

Wright LM Donaghy PC Burn DJ Taylor JP O’Brien JT Yarnall AJ et al . Brain network connectivity underlying neuropsychiatric symptoms in prodromal Lewy body dementia. Neurobiol Aging. (2025) 151:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2025.04.007

43.

Morrow CB Kamath V Dickerson BC Eldaief M Rezaii N Wong B et al . Neuropsychiatric symptoms cluster and fluctuate over time in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2025) 79:327–35. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13810

44.

Zhu CW Schneider LS Elder GA Soleimani L Grossman HT Aloysi A et al . Neuropsychiatric symptom profile in Alzheimer’s disease and their relationship with functional decline. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2024) 32:1402–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2024.06.005

45.

Wadsworth LP Lorius N Donovan NJ Locascio JJ Rentz DM Johnson KA et al . Neuropsychiatric symptoms and global functional impairment along the Alzheimer’s continuum. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2012) 34:96–111. doi: 10.1159/000342119

46.

Delfino LL Komatsu RS Komatsu C Neri AL Cachioni M . Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with family caregiver burden and depression. Dement Neuropsychol. (2021) 15:128–35. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642021dn15-010014

47.

Mank A van Maurik IS Rijnhart JJM Rhodius-Meester HFM Visser LNC Lemstra AW et al . Determinants of informal care time, distress, depression, and quality of life in care partners along the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2023) 15:e12418. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12418

48.

Ruthirakuhan M Ismail Z Herrmann N Gallagher D Lanctôt KL . Mild behavioral impairment is associated with progression to Alzheimer’s disease: a clinicopathological study. Alzheimers Dement. (2022) 18:2199–208. doi: 10.1002/alz.12519

49.

Vossius C Bergh S Selbæk G Benth JŠ Myhre J Aakhus E . Mortality in nursing home residents stratified according to subtype of dementia: a longitudinal study over three years. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22:282. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02994-9

50.

Cummings JL . The neuropsychiatric inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. (1997) 48:S10–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.5_Suppl_6.10S

51.

Caspar S Davis ED Douziech A Scott DR . Nonpharmacological management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: what works, in what circumstances, and why?Innov Aging. (2017) 1:igy 001. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy001

52.

Conde-Sala JL Reñé-Ramírez R Turró-Garriga O Gascón-Bayarri J Juncadella-Puig M Moreno-Cordón L et al . Clinical differences in patients with Alzheimer’s disease according to the presence or absence of anosognosia: implications for perceived quality of life. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2013) 33:1105–16. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121360

53.

Satler C Tomaz C . Cognitive anosognosia and behavioral changes in probable Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dement Neuropsychol. (2013) 7:197–205. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642013DN70200010

54.

Spalletta G Girardi P Caltagirone C Orfei MD . Anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms and disorders in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2012) 29:761–72. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111886

55.

Verhülsdonk S Quack R Höft B Lange-Asschenfeldt C Supprian T . Anosognosia and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2013) 57:282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.03.012

56.

Vogel A Waldorff FB Waldemar G . Impaired awareness of deficits and neuropsychiatric symptoms in early Alzheimer’s disease: the Danish Alzheimer intervention study (DAISY). J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2010) 22:93–9. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.1.93

57.

Lacerda IB Santos RL Neto JPS Dourado MCN . Factors related to different objects of awareness in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2017) 31:335–42. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000210

58.

Clare L Wilson BA Carter G Roth I Hodges JR . Awareness in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to outcome of cognitive rehabilitation. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (2004) 26:215–26. doi: 10.1076/jcen.26.2.215.28088

59.

Sato J Nakaaki S Murata Y Shinagawa Y Matsui T Hongo J et al . Two dimensions of anosognosia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Anosognosia questionnaire for dementia (AQ-D). Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2007) 61:672–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01734.x

60.

Yoon B Shim YS Hong YJ Choi SH Park HK Park SA et al . Anosognosia and its relation to psychiatric symptoms in early-onset Alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2017) 30:170–7. doi: 10.1177/0891988717700508

61.

Wang S Mimmack K Cacciamani F Elnemais Fawzy M Munro C Gatchel J et al . Anosognosia is associated with increased prevalence and faster development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci. (2024) 16:1335878. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1335878

62.

BBC Z Damasceno BP . Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: a neuropsychological approach. Dement Neuropsychol. (2007) 1:81–8. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642008DN10100013

63.

Jacus JP . Awareness, apathy, and depression in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain Behav. (2017) 7:e00661. doi: 10.1002/brb3.661

64.

Nakaaki S Murata Y Sato J Shinagawa Y Hongo J Tatsumi H et al . Impact of depression on insight into memory capacity in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2008) 22:369–74. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181820f58

65.

Oba H Matsuoka T Imai A Fujimoto H Kato Y Shibata K et al . Interaction between memory impairment and depressive symptoms can exacerbate anosognosia: a comparison of Alzheimer’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Ment Health. (2019) 23:595–601. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1442411

66.

Chen YL Chen HM Huang MF Yeh YC Yen CF Chen CS . Clinical correlates of unawareness of deficits among patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. (2014) 29:533–9. doi: 10.1177/1533317514523484

67.

Gilleen J Greenwood K Archer N Lovestone S David AS . The role of premorbid personality and cognitive factors in awareness of illness, memory, and behavioural functioning in Alzheimer’s disease. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. (2012) 17:227–45. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2011.588007

68.

Smith SM Jenkinson M Woolrich MW Beckmann CF Behrens TEJ Johansen-Berg H et al . Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. (2004) 23:S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051

69.

Derouesné C Thibault S Lagha-Pierucci S Baudouin-Madec V Ancri D Lacomblez L . Decreased awareness of cognitive deficits in patients with mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (1999) 14:1019–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199912)14:12<1019::AID-GPS61>3.0.CO;2-F

70.

Troisi A Pasini A Gori G Sorbi T Baroni A Ciani N . Clinical predictors of somatic and psychological symptoms of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (1996) 11:23–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199601)11:1<>3.0.CO;2-4

71.

Seltzer B Vasterling JJ Hale MA Khurana R . Unawareness of memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to mood and other disease variables. Cogn Behav Neurol. (1995) 8:176.

72.

Sevush S Leve N . Denial of memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. (1993) 150:748–51. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.748

73.

Kelleher M Tolea MI Galvin JE . Anosognosia increases caregiver burden in mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2016) 31:799–808. doi: 10.1002/gps.4394

74.

Lehrner J Kogler S Lamm C Moser D Klug S Pusswald G et al . Awareness of memory deficits in subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. (2015) 27:357–66. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002245

75.

van Vliet D de Vugt ME Köhler S Aalten P Bakker C Pijnenburg YAL et al . Awareness and its association with affective symptoms in young-onset and late-onset Alzheimer disease: a prospective study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2013) 27:265. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31826cffa5

76.

Cines S Farrell M Steffener J Sullo L Huey E Karlawish J et al . Examining the pathways between self-awareness and well-being in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2015) 23:1297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.005

77.

Horning SM Melrose R Sultzer D . Insight in Alzheimer’s disease and its relation to psychiatric and behavioral disturbances. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2014) 29:77–84. doi: 10.1002/gps.3972

78.

Lopez OL Becker JT Somsak D Dew MA DeKosky ST . Awareness of cognitive deficits and anosognosia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. (1994) 34:277–82. doi: 10.1159/000117056

79.

Mak E Chin R Ng LT Yeo D Hameed S . Clinical associations of anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2015) 30:1207–14. doi: 10.1002/gps.4275

80.

Starkstein SE Jorge R Mizrahi R Robinson RG . A diagnostic formulation for anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2006) 77:719–25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.085373

81.

Reed BR Jagust WJ Coulter L . Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (1993) 15:231–44. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402560

82.

Starkstein SE Sabe L Chemerinski E Jason L Leiguarda R . Two domains of anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1996) 61:485–90. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.5.485

83.

Amanzio M Torta DME Sacco K Cauda F D’Agata F Duca S et al . Unawareness of deficits in Alzheimer’s disease: role of the cingulate cortex. Brain. (2011) 134:1061–76. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr020

84.

Starkstein SE Brockman S Bruce D Petracca G . Anosognosia is a significant predictor of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2010) 22:378–83. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.4.378

85.

Turró-Garriga O Garre-Olmo J Calvó-Perxas L Reñé-Ramírez R Gascón-Bayarri J Conde-Sala JL . Course and determinants of Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: a 12-month follow-up. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2016) 51:357–66. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150706

86.

Yoo HS Chung SJ Lee YH Ye BS Sohn YH Lee PH . Cognitive anosognosia is associated with frontal dysfunction and lower depression in Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:951–8. doi: 10.1111/ene.14188

87.

Castro PCF Aquino CC Felício AC Doná F Medeiros LMI Silva SMCA et al . Presence or absence of cognitive complaints in Parkinson’s disease: mood disorder or anosognosia?Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2016) 74:439–44. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20160060

88.

Marino SE Meador KJ Loring DW Okun MS Fernandez HH Fessler AJ et al . Subjective perception of cognition is related to mood and not performance. Epilepsy Behav. (2009) 14:459–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.12.007

89.

Orfei MD Assogna F Pellicano C Pontieri FE Caltagirone C Pierantozzi M et al . Anosognosia for cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson’s disease with mild dementia and mild cognitive impairment: frequency and neuropsychological/neuropsychiatric correlates. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2018) 54:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.04.015

90.

Starkstein SE Sabe L Petracca G Chemerinski E Kuzis G Merello M et al . Neuropsychological and psychiatric differences between Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1996) 61:381–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.4.381

91.

Mikos AE Springer US Nisenzon AN Kellison IL Fernandez HH Okun MS et al . Awareness of expressivity deficits in non-demented Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropsychol. (2009) 23:805–17. doi: 10.1080/13854040802572434

92.

Mograbi DC Morris RG . On the relation among mood, apathy, and anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2014) 20:2–7. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001276

93.

Tagai K Nagata T Shinagawa S Shigeta M . Anosognosia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: current perspectives. Psychogeriatrics. (2020) 20:345–52. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12507

94.

Luther L Bonfils KA Firmin RL Buck KD Choi J Dimaggio G et al . Metacognition is necessary for the emergence of motivation in people with schizophrenia Spectrum disorders: a necessary condition analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2017) 205:960–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000753

95.

Apostolova LG Akopyan GG Partiali N Steiner CA Dutton RA Hayashi KM et al . Structural correlates of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2007) 24:91–7. doi: 10.1159/000103914

96.

Levy R Dubois B . Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cereb Cortex. (2006) 16:916–28. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043

97.

Nagata T Shinagawa S Ochiai Y Kada H Kasahara H Nukariya K et al . Relationship of frontal lobe dysfunction and aberrant motor behaviors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. (2010) 22:463–9. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991323

98.

Tekin S Mega MS Masterman DM Chow T Garakian J Vinters HV et al . Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. (2001) 49:355–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.72

99.

Bertrand E van Duinkerken E Laks J Dourado MCN Bernardes G Landeira-Fernandez J et al . Structural gray and white matter correlates of awareness in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2021) 81:1321–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201246

100.

Antoine N Bahri MA Bastin C Collette F Phillips C Balteau E et al . Anosognosia and default mode subnetwork dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. (2019) 40:5330–40. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24775

101.

Lee JS Kim JH Lee SK . The relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and default-mode network connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Investig. (2020) 17:662–6. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0009

102.

Negro G Rossi M Imbimbo C Gatti A Magi A Appollonio IM et al . Investigating neuropathological correlates of hyperactive and psychotic symptoms in dementia: a systematic review. Front Dement. (2025) 4:1513644. doi: 10.3389/frdem.2025.1513644

Summary

Keywords

anosognosia, unawareness, neuropsychiatric symptoms, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia

Citation

Gallingani C, Tondelli M, Vannini P and Zamboni G (2025) The association between anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative dementias: a narrative review. Front. Neurol. 16:1649627. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1649627

Received

18 June 2025

Accepted

10 September 2025

Published

26 September 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Gabriella Bottini, University of Pavia, Italy

Reviewed by

Giulia Negro, San Gerardo Hospital, Italy

Sandra Invernizzi, University of Mons, Belgium

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Gallingani, Tondelli, Vannini and Zamboni.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manuela Tondelli, manuela.tondelli@unimore.it

Disclaimer