- 1Department of Neurology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing, China

- 2Department of Neurology, Zhejiang Province People’s Hospital Haining Hospital, Jiaxing, China

- 3Jiaxing University Master Degree Cultivation Base, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China

- 4Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing, China

Delirium is a common and severe complication following acute cerebral ischemic stroke reperfusion, affecting cognitive and motor recovery and associated with poor long-term outcomes, prolonged hospitalization, increased readmission, and higher mortality. Identifying risk factors, understanding the pathogenesis (especially reperfusion injury), and implementing early intervention are crucial. However, the complex etiology and limited efficacy of drug treatments make early detection and management challenging. Recent studies have identified factors such as age, NIHSS score, pre-stroke cognition, and post-reperfusion inflammation, along with biomarkers, as predictors of delirium. Family involvement and environmental optimization may also reduce risk. This review summarizes current evidence on risk factors, pathogenesis, biomarkers, and interventions to improve early identification, reduce disability, and improve prognosis.

Introduction

Delirium is a frequently encountered acute or subacute neuropsychiatric syndrome in clinical settings, presenting with symptoms such as confusion, inattention, disorganized or incoherent thinking, and perceptual abnormalities that can vary significantly within a short timeframe. The latest International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition (ICD-11), published by the World Health Organization, defines delirium as a syndrome characterized by the acute or subacute onset of attention disturbance (e.g., a reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) and consciousness disturbance (e.g., impaired orientation to the environment). These symptoms, which often fluctuate within 24 h, are frequently accompanied by other cognitive deficits, including impairments in memory, language, visuospatial abilities, or perception. Delirium is commonly observed in hospitalized elderly patients and ICU patients. A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies reported a prevalence of 23.6% and incidence of 13.5% of delirium in hospitalized elderly individuals (1). In ICU patients aged 65 years or older, approximately 70% experience delirium (2). However, post-stroke delirium occurs at a rate of 18–30%, significantly impacting patient outcomes (3, 4).

With China’s aging population steadily increasing, stroke has emerged as a major public health concern, significantly affecting people’s health. Ischemic cerebral infarction, the most prevalent type of stroke, accounts for 69.6 to 70.8% of all strokes in China. Early reperfusion therapy (including intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular intervention) has proven to be the most effective treatment for ischemic stroke, but approximately 50% of patients still have a poor prognosis. Studies have shown that approximately 49.7% of patients with acute ischemic stroke who received reperfusion therapy develop delirium within the first 8 days of hospitalization (5). Recent studies on the relationship between reperfusion therapy and delirium have increased, primarily focusing on whether reperfusion therapy reduces delirium risk by improving brain ischemia, or potentially increases delirium incidence due to treatment itself (e.g., surgical stress). Research by Czyzycki et al. suggests that reperfusion therapy (including thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy) may have potential in preventing delirium by improving brain injury. However, the effect is influenced by pre-stroke cognitive status, with lower delirium rates observed in those without cognitive decline prior to the stroke (6). On the other hand, some studies have found a significant association between mechanical thrombectomy and postoperative delirium, particularly in elderly patients, which may be related to surgical trauma and perioperative management factors (7, 8).

The relationship between reperfusion and delirium is still unclear, and current interventions are limited. There is a lack of comprehensive research on delirium after acute cerebral ischemic stroke reperfusion in China, which is inconsistent with the large number of stroke patients in the country. This review integrates the latest domestic and international studies to summarize the potential pathogenesis, risk factors, biomarkers, and interventions for delirium following reperfusion in acute stroke, aiming to improve early identification, timely intervention, and overall prognosis.

Methods

This narrative review was conducted based on a comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library for relevant English-language articles published up to June 2025. The search used key words such as “acute stroke reperfusion therapy,” “delirium.” The Boolean combinations of search terms were (acute ischemic stroke OR acute cerebral infarction OR acute stroke) AND (reperfusion therapy OR intravenous thrombolysis OR mechanical thrombectomy) AND (delirium OR cognitive dysfunction OR altered mental status) NOT (pediatric stroke OR case reports). The research types included randomized controlled trials, observational studies and authoritative guidelines. The inclusion criteria were the studies include the occurrence of delirium during reperfusion therapy (intravenous thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy) for acute ischemic stroke, as well as the incidence, pathogenesis, assessment methods and treatment approaches of post-stroke reperfusion delirium. The exclusion criteria were pediatric stroke and case reports. Based on a clear research scope, studies focusing on acute ischemic stroke reperfusion therapy and exploring delirium risk factors, assessment tools, or management strategies were prioritized. The review emphasized high-quality, methodologically rigorous evidence, critically evaluating existing views and identifying gaps in the pathogenesis and management of delirium after reperfusion. It also suggested future research directions, including imaging and biological markers for delirium identification.

Pathogenesis of delirium after acute stroke

Although delirium arises from diverse etiologies, its clinical manifestations are often similar, implying a shared underlying pathogenesis. However, the precise mechanisms of delirium remain incompletely understood. Most scholars believe that the occurrence of delirium after acute stroke reperfusion therapy may be related to multiple pathophysiological mechanisms. The primary hypotheses are as follows:

Neuroinflammatory cascade reaction hypothesis

Although reperfusion therapy can restore cerebral blood flow, the local inflammatory response caused by ischemic brain injury may lead to blood–brain barrier damage, triggering neuroinflammation. The inflammatory response occurs throughout the ischemic injury process and is one of the possible mechanisms leading to delirium after reperfusion therapy. Increased inflammatory response in circulation is positively correlated with the development of delirium. Some inflammatory biomarkers (such as inflammatory factors NFL, IL-6/8 /10/1β and TNF-α) have been identified as risk factors for delirium in elderly individuals (9, 10). Increasing evidence suggests that glial cell dysfunction is associated with delirium (11). Research by Witcher KG et al. found that microglia, as key mediators of chronic inflammation, not only respond to and mediate inflammatory signals, causing brain tissue damage and blood–brain barrier disruption, but also influence neuronal responses to traumatic brain injury (12). A study by Liu J et al. found that midbrain astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF) may reduce the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of mice induced by surgery, thereby inhibiting surgery-induced inflammation, microglia activation, and M1 polarization, protecting mice from delirium-like behavioral disorders (13). However, a decrease in anti-inflammatory factors may exacerbate neuroinflammatory-related systemic damage.

To summarize, Ischemia–reperfusion injury activates microglia and astrocytes, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory factors like IL-1β and TNF-α, leading to neuroinflammation. This inflammation damages neurons, disrupts the blood–brain barrier, and enhances immune cell infiltration, further amplifying the inflammatory response (14). It also impairs cholinergic function and promotes glutamate excitotoxicity, disrupting neural circuits and contributing to delirium.

Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity hypothesis

Compared to other organs, the brain has weaker antioxidant defenses, making it more vulnerable to oxidative damage. During brain ischemia, reduced oxygen supply leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic disturbances (decreased ATP), and ion pump failure, causing elevated intracellular calcium levels and promoting free radical production. Reperfusion rapidly restores oxygen, converting it into reactive oxygen species (ROS) like superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. These ROS react with intracellular lipids, proteins, and DNA, causing cell membrane rupture, protein denaturation, and DNA damage, leading to brain cell death and blood–brain barrier disruption, which in turn exacerbates brain injury. Increased barrier permeability allows plasma proteins like fibrinogen to leak into the brain, triggering microglial activation and a neurotoxic environment (15). Blood products from hemorrhagic transformation (e.g., iron ions) induce oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis, especially in the cortex, raising delirium risk (16). Microcirculatory disorders after reperfusion cause local hypoxia, worsening mitochondrial dysfunction and energy failure. However, Research by Sun et al. found that remote ischemic preconditioning reduces oxidative stress and inflammation through the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, improving neurological function (17).

Abnormal cerebral perfusion and neurotransmitter imbalance hypothesis

Reperfusion therapy restores blood flow but can cause brain perfusion imbalance, impairing vascular autoregulation and leading to blood flow fluctuations, disrupting neuronal metabolism and neurotransmitter balance. Reperfusion therapy may disrupt neurotransmitters in the brain, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, norepinephrine, Glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid, aspartate and serotonin and this imbalance is considered a key mechanism for post-stroke delirium (18). Animal studies have shown that interference with multiple neurotransmitter systems can produce features of delirium (19). Acetylcholine (ACh) receptor antagonists cause widespread EEG slowing, most notably an increased δ wave frequency (1–3 Hz) and decreased α wave frequency (8–12 Hz), which is associated with delirium (20). Research by Massoudi N found that cholinesterase inhibitors are beneficial in improving post-stroke delirium symptoms (21). Acute cholinergic dysfunction can trigger delirium and may largely contribute to delirium symptoms, although this effect is most likely to occur in patients (or animals) with pre-existing cholinergic vulnerability (22). Antipsychotic medications, primarily acting through the blockade of D2 dopamine receptors, have long been used in the treatment of delirium. However, numerous prevention and treatment trials have failed to demonstrate the benefits of various antipsychotics (including haloperidol, olanzapine, or quetiapine) in preventing or treating delirium in multiple settings (23, 24), the hyperdopaminergic theory of delirium has been significantly weakened. Therefore, while dopaminergic status may influence the psychomotor state during delirium, it is unlikely to play a mechanistic role at the syndrome level. Histamine affects arousal by activating projections from the hypothalamus to the prefrontal cortex (PFC), limbic system, and basal ganglia. Several studies have highlighted the importance of histamine in wakefulness and alertness (25). Although clinical studies have not specifically focused on delirium, first-generation antihistamines (H1 receptor antagonists) have been widely described as having sedative effects, reducing the brain’s arousal state, while delirium is a known adverse effect of both H1 and H2 receptor antagonists (26). Norepinephrine has a profound impact on prefrontal cortex (PFC) activity. Norepinephrine neurons in the locus coeruleus are silent during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep but exhibit significant phasic firing during wakeful alertness. In contrast, under stress, activation of the amygdala stimulates the locus coeruleus, triggering high-toned norepinephrine activity, which leads to poor attention performance (27). In this scenario, cognitive and behavioral functions shift from the prefrontal cortex’s thoughtful “top-down” regulation to more reflexive, emotion-driven responses driven by the amygdala (e.g., fear and threat). Therefore, both excessive and insufficient norepinephrine activity can impair prefrontal cortex function (28), and it can be speculated that these different states of arousal may contribute to the high and low activity states seen in delirium.

Neural network disconnection hypothesis

The effect of neurotransmitters on brain states depends on the neural anatomical networks they act upon. Research by Morandi A et al. showed that loss of integrity in the corpus callosum between the hemispheres is associated with prolonged delirium duration (29). Diffusion tensor imaging revealed abnormalities in regions such as the hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum (as well as related white matter tracts: fiber bundles, fornix, internal capsule, and corpus callosum), with these abnormalities linked to the incidence and severity of delirium (30). Although most research on cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury focuses on cortical tissue, studies have shown that in the Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, hippocampal neurons are also damaged as neurological function worsens. Gao et al. reported that synaptic connection strength and protein expression are inhibited, with impaired synaptic plasticity being a key mechanism of reperfusion injury (31).

Reperfusion-specific injury mechanism hypothesis

Mechanical thrombectomy may cause endothelial damage and plaque detachment, leading to embolism or reocclusion. Repeated ischemia–reperfusion worsens oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage, triggering neuronal necrosis (32). Anesthetics like propofol may impair cortical function, worsening postoperative delirium (33).

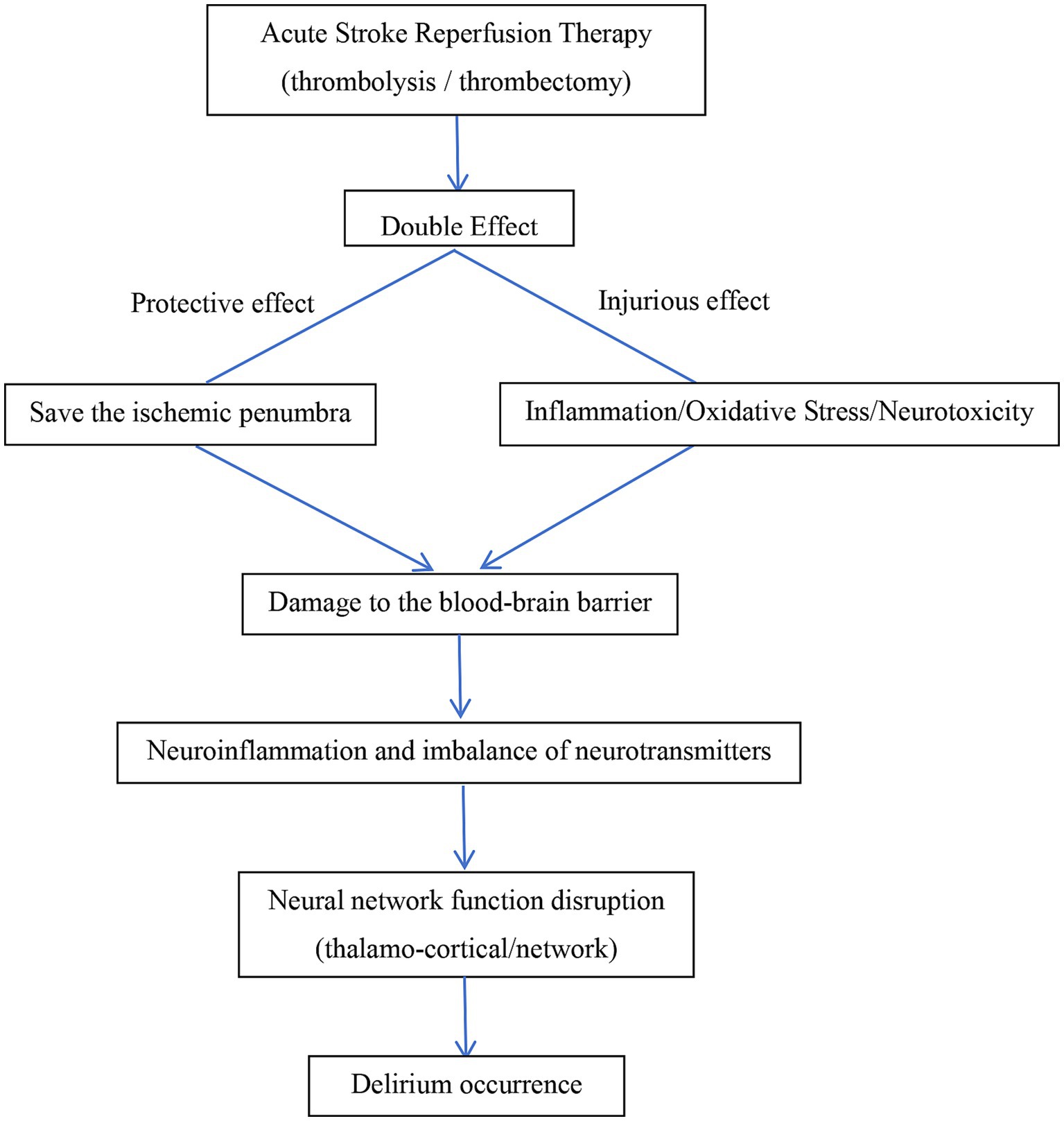

In summary, the occurrence of delirium after reperfusion is the result of multiple mechanisms working together. Key factors include perfusion imbalance and reperfusion-specific damage leading to neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, and blood–brain barrier disruption. These ultimately cause neurotransmitter regulation and neural network connectivity impairments, resulting in system integration failure and delirium symptoms. Future research should focus on precise therapeutic strategies targeting inflammatory pathways and blood–brain barrier protection. The possible pathological mechanisms of delirium occurrence after acute stroke reperfusion therapy are shown in Figure 1.

Risk factors for delirium after acute stroke reperfusion therapy

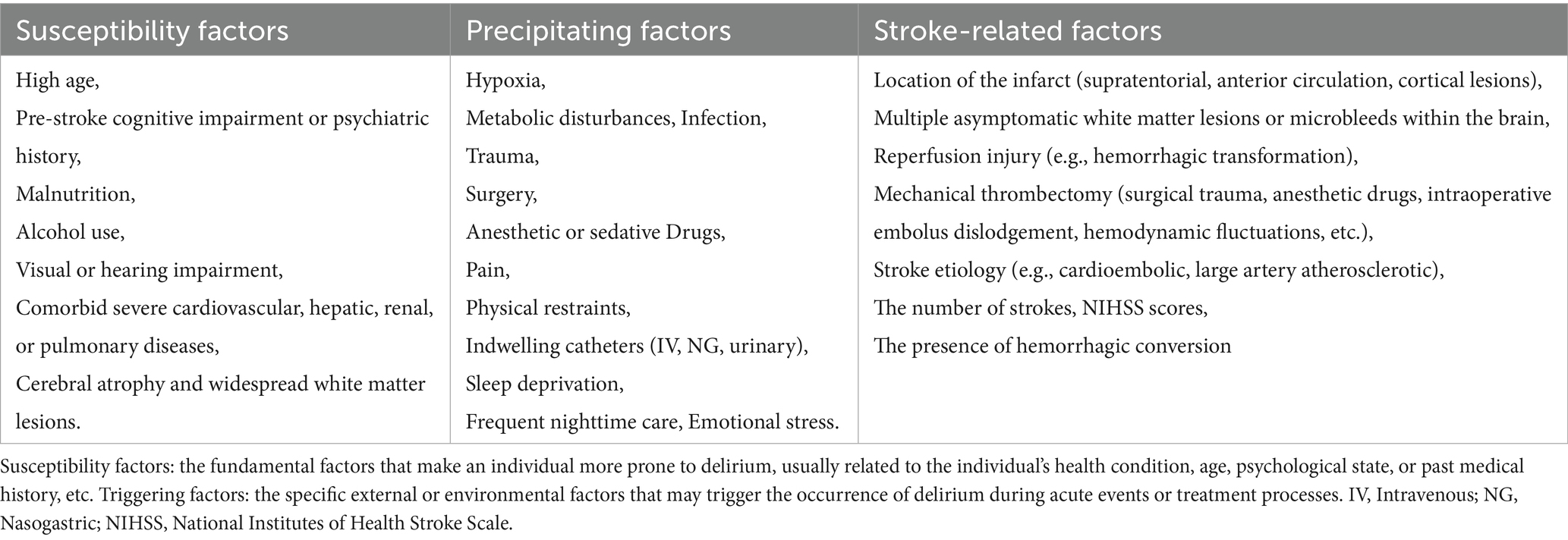

Most scholars, both domestically and internationally, agree that the onset of delirium is caused by a combination of factors, including both predisposing and precipitating risk factors. Predisposing factors include advanced age, cognitive impairment, comorbidities such as cardiovascular or renal diseases, a history of mental disorders, alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and visual or hearing impairments (34, 35). Neuroimaging studies have also demonstrated that patients with brain atrophy or white matter lesions are at a higher risk of developing delirium (36). Precipitating factors encompass traumatic brain injury, stroke, hypoxia, metabolic disorders, infections, trauma, surgery, anesthesia, pain, physical restraints, and emotional distress. Additionally, some studies have shown that certain medications, such as opioids and sedative-hypnotics, may increase the incidence of delirium (37). However, family involvement can significantly reduce the occurrence of delirium in critically ill patients (38).

In addition to the factors mentioned above, the location, size, number, and severity of strokes may also influence the occurrence of acute post-stroke delirium. Infarction in key areas (such as the left middle frontal gyrus, left angular gyrus, left basal ganglia, and left anterior thalamus) and certain conduction tracts (such as the right corticospinal tract, left posterior inferior cerebellar tract, left arcuate fasciculus, and left basal ganglia peripheral white matter), as well as asymptomatic cerebrovascular diseases (such as white matter lesions and microbleeds), are risk factors for delirium after stroke. Right hemisphere infarction is a risk factor for spatial neglect, which in turn is associated with delirium after stroke (39, 40). Patients with supratentorial, anterior circulation, or cortical lesions, higher NIHSS scores, cardioembolic or large artery atherosclerotic etiologies, intracranial hemorrhage, or larger/more extensive infarcts are more likely to develop delirium (41–43).

Reperfusion therapy (e.g., thrombolysis) is linked to a reduced risk of delirium, while the effect of mechanical thrombectomy is inconsistent and depends on patient characteristics. Delirium is associated with worse outcomes (e.g., mortality and disability) in reperfusion patients, though therapy may reduce delirium by improving brain perfusion (44). Successful reperfusion may also help reduce delirium-related complications (45). The impact of reperfusion therapy varies based on factors like timing, age, and comorbidities, requiring individualized evaluation of its benefits for delirium.

The possible risk factors for the occurrence of delirium after reperfusion therapy for acute stroke, including susceptibility factors, inducing factors and stroke-related factors were showed in Table 1.

In conclusion, reperfusion therapy has a complex bidirectional effect on delirium. On one hand, timely and effective reperfusion can restore blood flow, limit ischemic penumbra expansion, improve neurological outcomes, and reduce delirium incidence by enhancing brain plasticity. On the other hand, reperfusion can trigger inflammatory responses and oxidative stress, leading to reperfusion injury and worsening brain dysfunction. Invasive procedures like thrombectomy may also increase delirium risk through anesthesia, hemodynamic fluctuations, and microemboli. Therefore, clinical practice must strike a dynamic balance between maximizing the benefits of reperfusion and minimizing the risk of delirium. This requires optimizing the timing and strategy of reperfusion, enhancing perioperative monitoring, precisely controlling blood flow parameters, and identifying high-risk individuals, thereby improving neurological recovery while reducing the occurrence of delirium.

Assessment tools for delirium after acute stroke

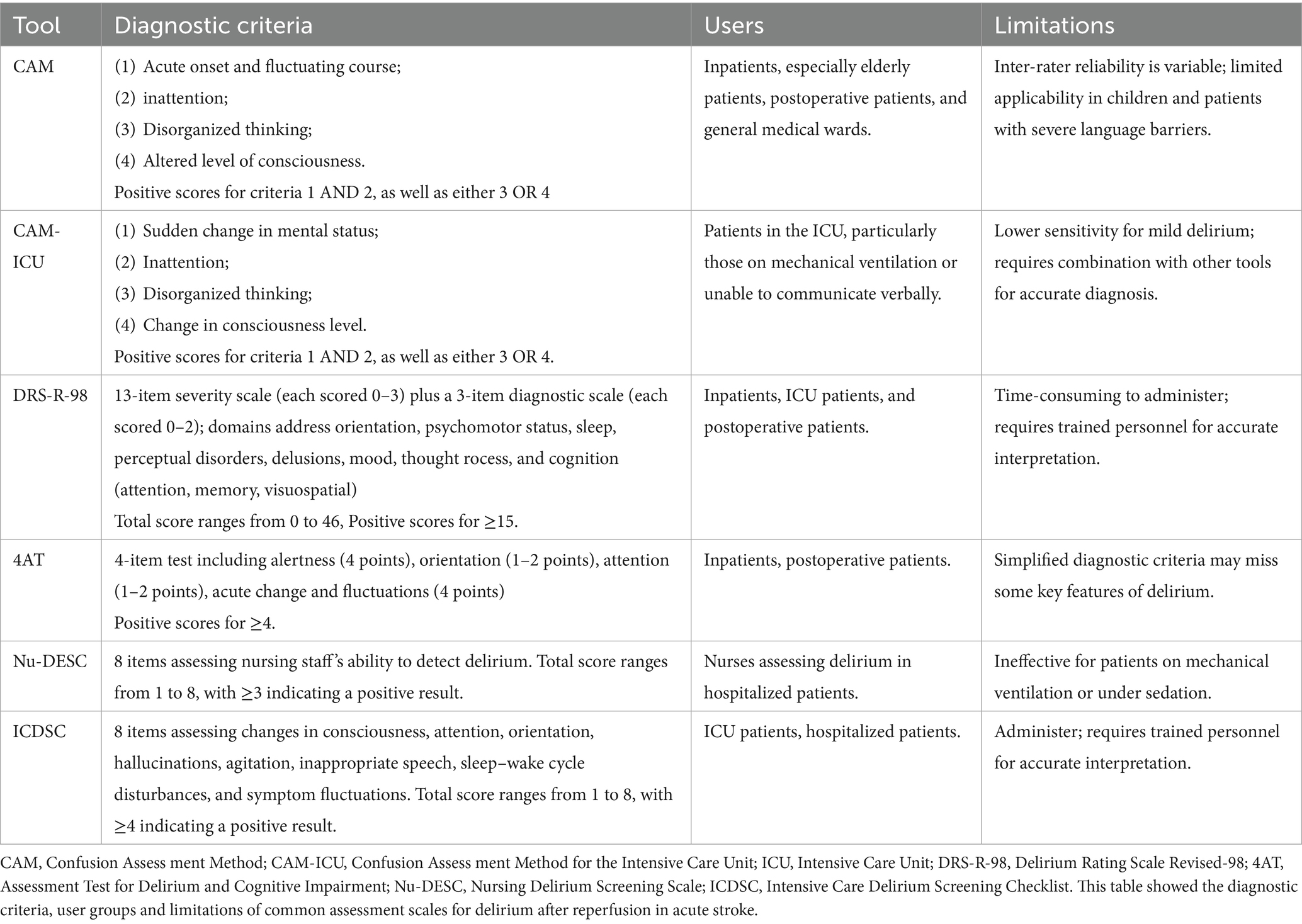

Symptoms such as speech disturbances and apathy in patients with acute stroke reperfusion therapy can be easily mistaken for delirium symptoms, complicating the screening and diagnosis process. Consequently, utilizing appropriate assessment tools is crucial for detecting delirium after acute stroke reperfusion therapy. Among the commonly used delirium screening and assessment tools is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), which is widely regarded as the most effective screening tool both domestically and internationally (46). CAM has been translated into over 20 languages. It assesses four features of delirium: (1) Acute onset and fluctuating changes in mental state; (2) Difficulty concentrating; (3) Disorganized thinking; (4) Altered level of consciousness. To meet the diagnostic criteria, the patient must exhibit both (1) and (2), along with at least one of (3) or (4) CAM has been adapted into other scales through extensive clinical application. For example, the Chinese version of the 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for CAM-defined Delirium (3D-CAM), translated and revised by Gao et al. in 2018, simplifies the assessment of the four CAM features, significantly reducing the time required for evaluation. The study also assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the 3D-CAM, which were found to be 94.73 and 97.92%, respectively (47). However, this scale has a limitation, which is that it cannot be used for patients in deep sedation or coma. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU), modified by Ely et al., is primarily used to assess delirium in patients admitted in ICU and is appropriate for situations where patients cannot cooperate verbally (48). It is convenient, quick, and accurate, and is frequently regarded as the diagnostic “gold standard” by ICU healthcare professionals.

In 2014, Bellelli et al. introduced a new delirium assessment tool, the 4A Test (4 “A”s Test, 4AT) (49). This scale assesses four key aspects: alertness, orientation, attention, and acute changes or fluctuations in mental status. It is simple and easy to use, enabling clinical staff to administer it without the need for specialized training. A score of ≥ 4 suggests the potential presence of delirium, with or without cognitive impairment; a score of 1 to 3 indicates possible cognitive impairment; and a score of 0 suggests no delirium or severe cognitive impairment. The scale’s sensitivity is 90%, and its specificity is 94%, as validated by Lai YH et al. (50). Huang et al. were the first to translate the Delirium Rating Scale, revised in 1998 (DRS-R-98), into Chinese (51). This scale consists of 16 items and typically takes around 30 min to complete. It covers multiple areas, including sleep, hallucinations, emotions, attention, and visuospatial abilities. The scale has been validated with a sensitivity of 89.3% and a specificity of 96.8%, and it is now widely used in clinical practice.

The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) is a nurse-administered delirium screening tool suitable for hospitalized patients, with a sensitivity of 29–95% and a specificity of 69–90%. However, it is not applicable to patients with endotracheal intubation (52). The Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) is a delirium screening tool specifically designed for ICU patients, applicable to both hospitalized and ICU settings, with a sensitivity of 74–99% and a specificity of 64–82%. However, it requires longer scoring time and higher training for non-specialists (53). The diagnostic criteria, user groups and limitations of common assessment scales for delirium after reperfusion in acute stroke were presented in Table 2.

Due to limitations in scale usage, such as patients’ consciousness and assessors’ subjective judgment, recent studies suggest using CT or MRI neuroimaging to assess post-stroke reperfusion delirium. The following markers have demonstrated certain value in prospective studies and have shown good reproducibility and feasibility in the stroke unit.

MTA score

The Pathological hippocampal Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy (MTA) score on CT, by quantifying the pathological changes (atrophy, low-density lesions, etc.) in the hippocampal region, assists in predicting the risk of delirium (54). This score demonstrated good reproducibility in a multicenter study, was simple to operate, and was suitable for routine application in stroke units.

Fazekas score

The Fazekas score for pathological leukoaraiosis on cranial MRI is used to assess the severity of brain white matter lesions. Studies have shown that a higher Fazekas score is significantly associated with the occurrence of post-reperfusion delirium (55). This score demonstrates certain stability across different devices and scanning parameters, and is widely used in clinical practice. It can be regarded as a routine indicator for assessing the risk of post-stroke reperfusion delirium.

ASL

The Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) can non-invasively assess cerebral blood flow perfusion and detect the areas of low perfusion in the brain after reperfusion. Multiple prospective studies have confirmed that the abnormal cerebral blood flow shown by ASL is closely related to the occurrence of delirium (56). Its advantages lie in the fact that no contrast agent is required, it is highly safe, and it can be easily implemented on the multimodal imaging platform of the stroke unit, with good repeatability.

DTI

The Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) can reflect the integrity and direction of nerve fibers and is used to assess nerve network damage. The research has found that patients with post-reperfusion delirium exhibit abnormal diffusion of white matter fiber tracts (57). With the advancement of technology, the application of DTI in stroke units has gradually become widespread, and its results have high reproducibility.

SWI

The Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI) is sensitive to microbleeds, vascular malformations, and other minute lesions, and can detect potential microbleeds or vascular abnormalities after reperfusion. These lesions may be related to the mechanism of delirium (58). SWI can produce stable imaging on MRI devices of different magnetic field strengths, with high image resolution, which helps stroke units accurately identify high-risk individuals.

The above biomarkers suggest that neurofunctional imaging and other imaging techniques may be an important direction for the future development of delirium assessment.

Biomarkers associated with delirium after acute stroke reperfusion

Some biomarkers can predict the risk of delirium after stroke, such as inflammatory factors: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6/8/10/1β, and TNF-α (59–61); neurofilament light chain (NFL) (62); and neuroglial cells, including astrocytes, microglia, and neuroglial activation factors (e.g., S100β) (63); and neuroprotective factors such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (64, 65). Bai Y et al. found that the brain’s response to transcranial magnetic stimulation electroencephalography (TMS-EEG) can identify high-risk patients for delirium after stroke (66).

Treatment of delirium after acute stroke reperfusion therapy

The pathogenesis of post-stroke reperfusion delirium involves multiple pathological mechanisms, with numerous triggering and risk factors. Currently, there are no unified guidelines for the treatment, both domestically and internationally.

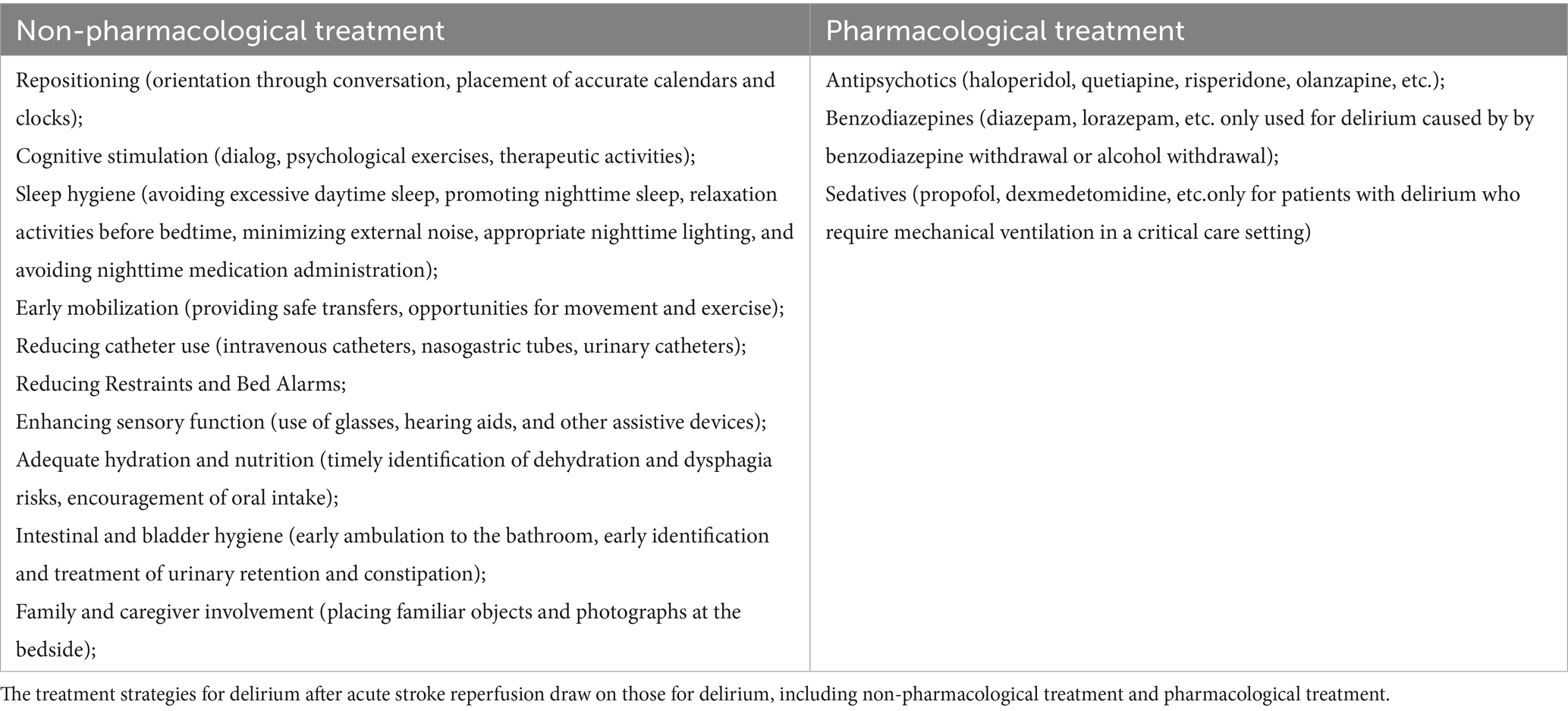

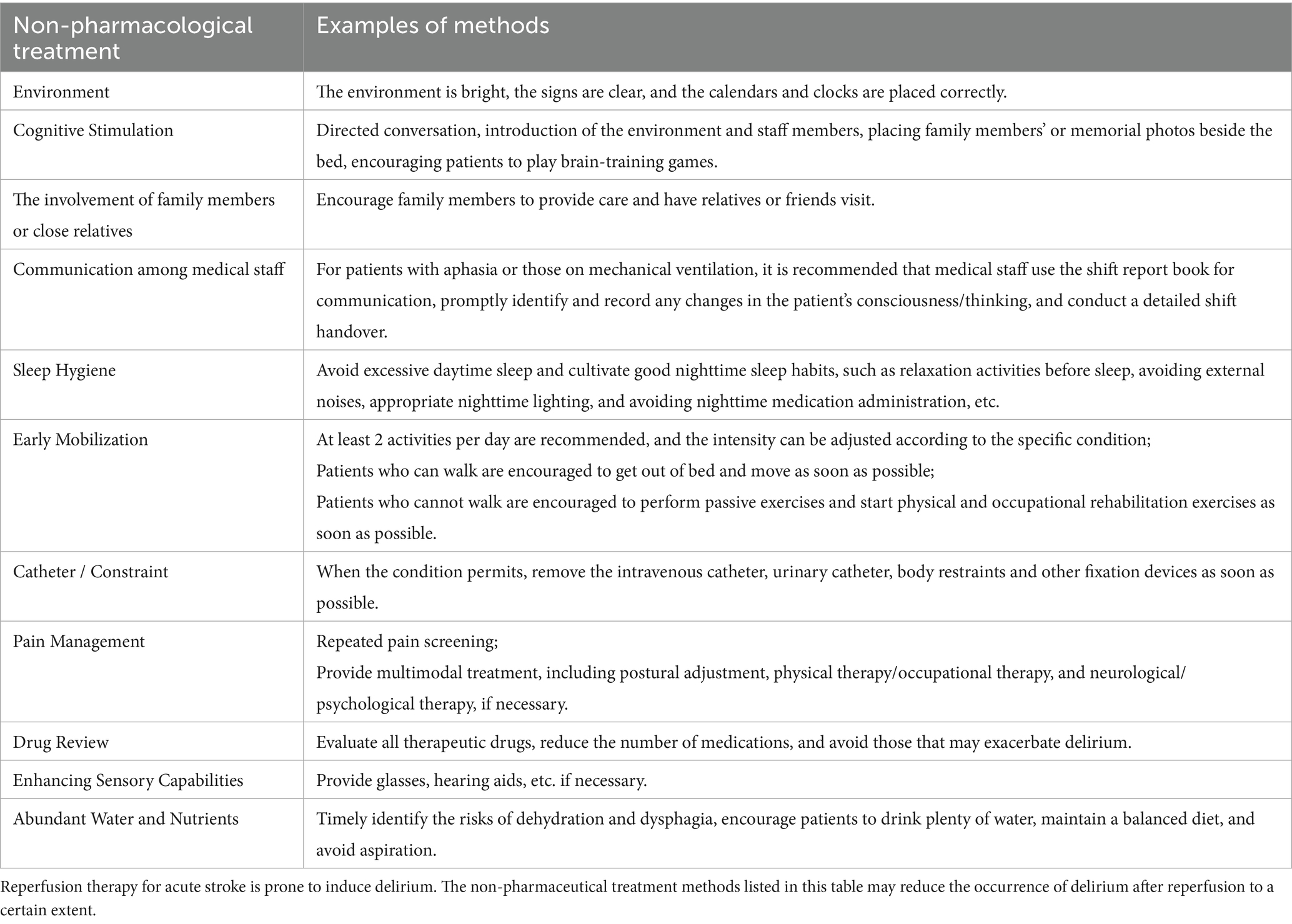

Several systematic reviews have evaluated the treatment of delirium in hospitalized patients, concluding that antipsychotic medications do not significantly affect the severity of delirium, symptom relief, or mortality and should not be the primary treatment approach (67–69). Thus, the prevailing opinion among domestic experts is that post-stroke reperfusion delirium treatment should focus primarily on addressing precipitating factors, with non-pharmacological interventions being prioritized. Antipsychotic medications may be used to treat delirium with behavioral and emotional disturbances when it causes significant distress, poses a safety risk, or interferes with essential treatments, and non-drug therapies fail. Recommended drugs include haloperidol, quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, starting at low doses and gradually increasing based on improvement and side effects, with treatment lasting 1–2 weeks. Medication can be tapered after delirium resolves for 2 days. During the medication period, it is necessary to monitor for extrapyramidal adverse reactions, electrocardiogram, changes in QT interval and changes in consciousness level. Table 3 showed the treatment strategies for delirium occurrence after reperfusion therapy for acute stroke, including non-pharmacological treatment and pharmacological treatment. Research on delirium treatment/prevention in acute stroke patients receiving reperfusion therapy is limited. This article provides recommendations for non-pharmacological prevention strategies based on existing literature (70). Non-pharmaceutical treatments and specific operations were presented in Table 4.

In summary, the difficulty in identifying delirium after acute stroke reperfusion can be attributed to the following factors:

1. Insufficient understanding of post-stroke delirium, leading to the perception that elderly patients’ drowsiness or confusion after illness is a normal phenomenon;

2. Delirium is often mistaken for a symptom of stroke, rather than recognized as a distinct clinical entity;

3. Inadequate familiarity with delirium screening tools, resulting in low diagnostic rates;

4. Delirium is frequently overlooked during discharge, transfer, or follow-up;

5. Poor communication among nursing staff when dealing with patients experiencing mental confusion, delaying the recognition of changes in consciousness or cognition.

Conclusion

Delirium is a common and serious complication after acute stroke reperfusion therapy. Its symptoms overlap with stroke symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Traditional scales have limitations, such as the patient’s consciousness state and the subjectivity of the assessor. Some neuroimaging and serum biomarkers now serve as effective tools for early detection of delirium after stroke reperfusion. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, evidence suggests links to neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and neurotransmitter imbalance. Despite poor prognosis, no effective treatment exists, and behavioral interventions are critical for prevention. Future research is needed to develop better strategies for this condition. Standardized treatment in stroke units is key to prevention. Future research is needed to clarify its pathogenesis and improve prevention and treatment.

Author contributions

Y-NH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. X-YF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. X-DY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. X-LZ: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The Public Welfare Research Program of Jiaxing (No. 2024AD30092).

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to all the people who have given us help on our article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

REM, Rapid Eye Movement; CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; 3D-CAM, 3 min Delirium Confusion Assessment Method; CAM-ICU, Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit; 4AT, 4 “A”s Test; Nu-DESC, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale; ICDSC, Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist; MTA, Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy; ASL, Arterial Spin Labeling; SWI, Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging; DTI, Diffusion Tensor Imaging; MCAO, Middle cerebral artery occlusion.

References

1. Wu, CR, Chang, KM, Tranyor, V, and Chiu, H-Y. Global incidence and prevalence of delirium and its risk factors in medically hospitalized older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2025) 162:104959. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104959

2. Alaterre, C, Fazilleau, C, Cayot-Constantin, S, Chanques, G, Kacer, S, Constantin, JM, et al. Monitoring delirium in the intensive care unit: diagnostic accuracy of the CAM-ICU tool when performed by certified nursing assistants - a prospective multicenter study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2023) 79:103487. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103487

3. Ye, F, Ho, MH, and Lee, JJ. Prevalence of post-stroke delirium in acute settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2024) 154:104750. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104750

4. Mukminin, MA, Yeh, TH, Lin, HC, Rohmah, I, and Chiu, HY. Global prevalence and risk factors of delirium among patients following acute stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2025) 34:108221. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.108221

5. Sahakyan, G, Orduyan, M, Adamyan, A, Koshtoyan, K, Hovhannisyan, G, Karapetyan, A, et al. Unaddressed palliative care needs of ischemic stroke patients treated with reperfusion therapies after age 80. BMC Palliat Care. (2025) 24:130. doi: 10.1186/s12904-025-01773-8

6. Czyzycki, M, Pera, J, and Dziedzic, T. Reperfusion therapy and risk of post-stroke delirium. Neurol Res. (2025) 47:1–6. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2024.2403484

7. Sachdev, A, Torrez, D, Sun, S, Michapoulos, G, Rigler, NC, Feldner, AL, et al. Postprocedural delirium following mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective study. Front Anesthesiol. (2024) 3:3. doi: 10.3389/fanes.2024.1351698

8. Rollo, E, Monforte, M, Brunetti, V, di Iorio, R, Fulignati, L, de Scisciolo, M, et al. Stroke-related delirium in patients undergoing revascularization treatments: a retrospective, observational study. J Neurol Sci. (2023) 455:122419. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2023.122419

9. Mosharaf, MP, Alam, K, Gow, J, and Mahumud, RA. Cytokines and inflammatory biomarkers and their association with post-operative delirium: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:7830. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-82992-6

10. Kruize, Z, van Campen, I, Vermunt, L, Geerse, O, Stoffels, J, Teunissen, C, et al. Delirium pathophysiology in cancer: neurofilament light chain biomarker - narrative review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. (2025) 15:319–25. doi: 10.1136/spcare-2024-004781

11. Heffernan, ÁB, Steinruecke, M, Dempsey, G, Chandran, S, Selvaraj, BT, Jiwaji, Z, et al. Role of glia in delirium: proposed mechanisms and translational implications. Mol Psychiatry. (2025) 30:1138–47. doi: 10.1038/s41380-024-02801-4

12. Witcher, KG, Bray, CE, Chunchai, T, Zhao, F, O'Neil, SM, Gordillo, AJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury causes chronic cortical inflammation and neuronal dysfunction mediated by microglia. J Neurosci. (2021) 41:1597–616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2469-20.2020

13. Liu, J, Shen, Q, Zhang, H, Xiao, X, lv, C, Chu, Y, et al. The potential protective effect of mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor on post-operative delirium via inhibiting inflammation and microglia activation. J Inflamm Res. (2021) 14:2781–91. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S316560

14. Litvinenko, I, Khlystov, Y, Tsygan, N, Litvinenko, IV, Khlystov, YV, Tsygan, NV, et al. Delirium in acute ischemic stroke: risk factors, sequelae, and pathogenetic treatment. Ann Clin Exp Neurol. (2025) 19:14–20. doi: 10.17816/acen.1276

15. Cai, YT, Xing, HR, and Hao, MH. Research progress on microvascular injury after reperfused ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction assessed by CMR imaging. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. (2022) 50:1237–42. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20220403-00240

16. Lyu, Y, Ren, XK, Guo, CC, Li, ZF, and Zheng, JP. Benzo(a)pyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol-9,10-epoxide induces ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells through redox imbalance. J Toxicol Sci. (2022) 47:519–29. doi: 10.2131/jts.47.519

17. Sun, YY, Zhu, HJ, Zhao, RY, Zhou, SY, Wang, MQ, Yang, Y, et al. Remote ischemic conditioning attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in MCAO mice. Redox Biol. (2023) 66:102852. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102852

18. Farasat, S, Dorsch, JJ, Pearce, AK, Moore, AA, Martin, JL, Malhotra, A, et al. Sleep and Delirium in Older Adults. Curr Sleep Med Rep. (2020) 6:136–48. doi: 10.1007/s40675-020-00174-y

19. Hall, RJ, Watne, LO, Cunningham, E, Zetterberg, H, Shenkin, SD, Wyller, TB, et al. CSF biomarkers in delirium: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2018) 33:1479–500. doi: 10.1002/gps.4720

20. Itil, T, and Fink, M. Anticholinergic drug-induced delirium: experimental modification, quantitative EEG and behavioral correlations. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1966) 143:492–507. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196612000-00005

21. Marschallinger, J, Iram, T, Zardeneta, M, Lee, SE, Lehallier, B, Haney, MS, et al. Author correction: lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat Neurosci. (2020) 23:1308. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0682-y

22. Field, RH, Gossen, A, and Cunningham, C. Prior pathology in the basal forebrain cholinergic system predisposes to inflammation-induced working memory deficits: reconciling inflammatory and cholinergic hypotheses of delirium. J Neurosci. (2012) 32:6288–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4673-11.2012

23. Enser, RB. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1901272

24. van den Boogaard, M, Slooter, AJC, Brüggemann, RJM, Schoonhoven, L, Beishuizen, A, Vermeijden, JW, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2018) 319:680–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0160

25. Scammell, TE, Jackson, AC, Franks, NP, Wisden, W, and Dauvilliers, Y. Histamine: neural circuits and new medications. Sleep. (2019) 42:1–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy183

26. Chazot, PL, Johnston, L, Mcauley, E, and Bonner, S. Histamine and delirium: current opinion. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:299. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00299

27. Aston-Jones, G, and Cohen, JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2005) 28:403–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709

28. Woo, E, Sansing, LH, Arnsten, AFT, and Datta, D. Chronic stress weakens connectivity in the prefrontal cortex: architectural and molecular changes. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). (2021) 5:24705470211029254. doi: 10.1177/24705470211029254

29. Morandi, A, Rogers, BP, Gunther, ML, Merkle, K, Pandharipande, P, Girard, TD, et al. The relationship between delirium duration, white matter integrity, and cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors as determined by diffusion tensor imaging: the VISIONS prospective cohort magnetic resonance imaging study*. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:2182–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250acdc

30. Cavallari, M, Dai, W, and Guttmann, CR. Neural substrates of vulnerability to postsurgical delirium as revealed by presurgical diffusion MRI. Brain. (2016) 139:1282–94. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww010

31. Gao, B, Zhou, S, Sun, C, Cheng, D, Zhang, Y, Li, X, et al. Brain endothelial cell-derived exosomes induce neuroplasticity in rats with ischemia/reperfusion injury. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2020) 11:2201–13. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00089

32. Yang, M, Liu, B, Chen, B, Shen, Y, and Liu, G. Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: mechanisms and promising therapies. Front Pharmacol. (2025) 16:1613464. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1613464

33. Shi, M, Chen, J, Liu, T, Dai, W, Zhou, Z, Chen, L, et al. Protective effects of Remimazolam on cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats by inhibiting of NLRP3 Inflammasome-dependent Pyroptosis. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2022) 16:413–23. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S344240

34. Bramley, P, McArthur, K, Blayney, A, and McCullagh, I. Risk factors for postoperative delirium: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 93:106063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106063

35. Velayati, A, Vahdat Shariatpanahi, M, Shahbazi, E, and Vahdat Shariatpanahi, Z. Association between preoperative nutritional status and postoperative delirium in individuals with coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective cohort study. Nutrition. (2019) 66:227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2019.06.006

36. Nitchingham, A, Kumar, V, Shenkin, S, Ferguson, KJ, and Caplan, GA. A systematic review of neuroimaging in delirium: predictors, correlates and consequences. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2018) 33:1458–78. doi: 10.1002/gps.4724

37. van Gelder, TG, van Diem-Zaal, IJ, Dijkstra-Kersten, SMA, de Mul, N, Lalmohamed, A, and Slooter, AJC. The risk of delirium after sedation with propofol or midazolam in intensive care unit patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2024) 90:1471–9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.16031

38. Li, J, Fan, Y, Luo, R, Wang, Y, Yin, N, Qi, W, et al. Family involvement in preventing delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2025) 161:104937. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104937

39. Ott, J, Oh-Park, M, and Boukrina, O. Association of delirium and spatial neglect in patients with right-hemisphere stroke. PM R. (2023) 15:1075–82. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12922

40. Boukrina, O, Kowalczyk, M, Koush, Y, Kong, Y, and Barrett, AM. Brain network dysfunction in Poststroke delirium and spatial neglect: an fMRI study. Stroke. (2022) 53:930–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035733

41. Rhee, JY, Colman, MA, and Mendu, M. Associations between stroke localization and delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. (2021) 31:106270. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.106270

42. Fleischmann, R, Andrasch, T, Warwas, S, Kunz, R, Gross, S, Witt, C, et al. Predictors of post-stroke delirium incidence and duration: results of a prospective observational study using high-frequency delirium screening. Int J Stroke. (2023) 18:278–84. doi: 10.1177/17474930221109353

43. Bilek, AJ, and Richardson, D. Post-stroke delirium and challenges for the rehabilitation setting: a narrative review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2023) 32:107149. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107149

44. Zhang, GB, Lv, JM, Yu, WJ, Li, HY, Wu, L, Zhang, SL, et al. The associations of post-stroke delirium with outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. (2024) 22:470. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03689-1

45. Gong, X, Jin, S, Zhou, Y, Lai, L, and Wang, W. Impact of delirium on acute stroke outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. (2024) 45:1897–911. doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-07287-6

46. de la Cruz, M, Fan, J, Yennu, S, Tanco, K, Shin, SH, Wu, J, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. (2015) 23:2427–33. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2610-3

47. Inouye, SK, van Dyck, CH, Alessi, CA, Balkin, S, Siegal, AP, and Horwitz, RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. (1990) 113:941–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941

48. Ely, EW, Inouye, SK, Bernard, GR, Gordon, S, Francis, J, May, L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. (2001) 286:2703–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703

49. Bellelli, G, Morandi, A, Davis, DH, Mazzola, P, Turco, R, Gentile, S, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. (2014) 43:496–502. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu021

50. Lai, YH, Lin, CJ, Su, IC, Huang, SW, Hsiao, CC, Jao, YL, et al. Clinical utility and performance of the traditional Chinese version of the 4-as test for delirium due to traumatic brain injury. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. (2025) 66:130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2024.12.005

51. Huang, MC, Lee, CH, Lai, YC, Kao, YF, Lin, HY, and Chen, CH. Chinese version of the delirium rating scale-Revised-98: reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. (2009) 50:81–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.05.011

52. Jeong, E, Park, J, and Lee, J. Diagnostic test accuracy of the nursing delirium screening scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:2510–21. doi: 10.1111/jan.14482

53. Schellhorn, T, Zucknick, M, Askim, T, Munthe-Kaas, R, Ihle-Hansen, H, Seljeseth, YM, et al. Pre-stroke cognitive impairment is associated with vascular imaging pathology: a prospective observational study. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:362. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02327-2

54. Lauriola, M, D'Onofrio, G, la Torre, A, Ciccone, F, Germano, C, Cascavilla, L, et al. CT-detected MTA score related to disability and behavior in older people with cognitive impairment. Biomedicine. (2022) 10:1381. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10061381

55. Clancy, U, Cheng, Y, Jardine, C, Doubal, F, MacLullich, AMJ, and Wardlaw, JM. Small vessel disease contributions to acute delirium: a pilot feasibility MRI study. Age Ageing. (2025) 54:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaf099

56. Kalantari, S, Soltani, M, Maghbooli, M, Khoshe Mehr, FS, Kalantari, Z, Borji, S, et al. Cerebral blood flow alterations measured by ASL-MRI as a predictor of vascular dementia in small vessel ischemic disease. Radiologia (Engl Ed). (2025) 67:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rxeng.2024.03.013

57. Chao, X, Wang, J, Dong, Y, Fang, Y, Yin, D, Wen, J, et al. Neuroimaging of neuropsychological disturbances following ischaemic stroke (CONNECT): a prospective cohort study protocol. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e077799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077799

58. Lammers-Lietz, F, Borchers, F, Feinkohl, I, Hetzer, S, Kanar, C, Konietschke, F, et al. An exploratory research report on brain mineralization in postoperative delirium and cognitive decline. Eur J Neurosci. (2024) 59:2646–64. doi: 10.1111/ejn.16282

59. Sarejloo, S, Shojaei, N, Lucke-Wold, B, Zelmanovich, R, and Khanzadeh, S. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio as prognostic predictors for delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:58. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-01997-2

60. Klimiec-Moskal, E, Slowik, A, and Dziedzic, T. Serum C-reactive protein adds predictive information for post-stroke delirium: the PROPOLIS study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2023) 147:536–42. doi: 10.1111/acps.13489

61. Klimiec-Moskal, E, Piechota, M, Pera, J, Weglarczyk, K, Slowik, A, Siedlar, M, et al. The specific ex vivo released cytokine profile is associated with ischemic stroke outcome and improves its prediction. J Neuroinflammation. (2020) 17:7. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1691-1

62. Ferrara, MC, Lozano-Vicario, L, and Arosio, B. Neurofilament-light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein as blood-based delirium risk markers: a multicohort study. Aging Dis. (2025) 17:1–12. doi: 10.14336/AD.2025.0107

63. Ishii, T, Wang, T, and Shibata, K. Glial contribution to the pathogenesis of post-operative delirium revealed by multi-omic analysis of brain tissue from neurosurgery patients. bioRxiv. (2025) 03.13:643155. doi: 10.1101/2025.03.13.643155

64. Górna, S, Podgórski, T, Kleka, P, and Domaszewska, K. Effects of different intensities of endurance training on Neurotrophin levels and functional and cognitive outcomes in post-Ischaemic stroke adults: a randomised clinical trial. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:2810. doi: 10.3390/ijms26062810

65. Yang, H, Wu, Q, and Zheng, J. Expression and clinical significance of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, insulin-like growth factor 1, and beta-2 microglobulin in cognitive dysfunction after ischemic stroke in the elderly. Neuroreport. (2025) 36:127–34. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000002128

66. Bai, Y, Belardinelli, P, Thoennes, C, Blum, C, Baur, D, Laichinger, K, et al. Cortical reactivity to transcranial magnetic stimulation predicts risk of post-stroke delirium. Clin Neurophysiol. (2023) 148:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2022.11.017

67. Nikooie, R, Neufeld, KJ, Oh, ES, Wilson, LM, Zhang, A, Robinson, KA, et al. Antipsychotics for treating delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 171:485–95. doi: 10.7326/M19-1860

68. Davis, D, Searle, SD, and Tsui, A. The Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network: risk reduction and management of delirium. Age Ageing. (2019) 48:485–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz036

69. Lin, P, Zhang, J, Shi, F, and Liang, ZA. Can haloperidol prophylaxis reduce the incidence of delirium in critically ill patients in intensive care units? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. (2020) 49:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.01.010

70. Kneihsl, M, Berger, N, Sumerauer, S, Asenbaum-Nan, S, Höger, FS, Gattringer, T, et al. Management of delirium in acute stroke patients: a position paper by the Austrian stroke society on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2024) 17:17562864241258788. doi: 10.1177/17562864241258788

Keywords: delirium after acute stroke reperfusion, risk factors, pathogenesis, biomarkers, intervention

Citation: Hao Y-N, Feng X-Y, Wu F, Yang X-D and Zhang X-L (2025) Current perspectives on the early identification and management of delirium after acute stroke reperfusion therapy. Front. Neurol. 16:1664070. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1664070

Edited by:

Stefano Ministrini, University of Zurich, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Giuliano Cassataro, Institute Foundation G.Giglio, ItalyLudovica Anna Cimini, University of Perugia, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Hao, Feng, Wu, Yang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-Ling Zhang, emhhb3hpYW9saW5nenpAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Xiao-Dan Yang, eGlhb2Rhbnlhbmd5eGRAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Ya-Nan Hao1†

Ya-Nan Hao1† Xiao-Ling Zhang

Xiao-Ling Zhang