- 1Hhaider5 Research Group, Bronx, NY, United States

- 2Department of Neurosurgery, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, United States

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Spectrum Health, Grand Rapids, MI, United States

- 4Department of Neurosurgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, United States

- 5Department of Neurology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

- 6Department of Neurosurgery, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

Machine learning (ML) approaches have emerged as promising tools for improving seizure-onset zone (SOZ) prediction in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE). This systematic review aimed to evaluate the application and performance of ML approaches for SOZ prediction in patients with DRE. A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Epistemonikos databases for studies employing ML algorithms for SOZ prediction in patients with DRE. The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies version 2 (QUADAS-2) tool was adopted to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of included studies. Data on patient demographics, data acquisition methods, ML algorithms, and performance metrics were extracted and systematically synthesized. Out of a total of 38 studies, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria, encompassing 352 patients (mean age: 28 years, 34% female population). The studies employed various ML techniques, including traditional methods such as support vector machines and advanced deep learning architectures. Performance metrics varied widely across studies, with some approaches achieving accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity values above 90%. Deep learning models generally outperformed traditional methods, particularly in handling complex, multimodal data. Notably, personalized models demonstrated superior performance in reducing localization error and spatial dispersion. However, heterogeneity in data acquisition methods, patient populations, and reporting standards complicated direct comparisons between studies. This review highlighted the potential of ML approaches, particularly deep learning and personalized models, to enhance SOZ prediction accuracy in patients with DRE. However, several challenges were identified, including the need for standardized data collection protocols, larger prospective studies, and improved model interpretability. The findings underscore the importance of considering network-level changes in epilepsy when developing ML models for SOZ prediction. Although ML approaches show promise for improving surgical planning and outcomes in DRE, their clinical utility, particularly in complex epilepsy cases, requires further investigation. Addressing these challenges will be crucial in realizing the full potential of ML in enhancing epilepsy care.

1 Introduction

Epilepsy affects more than 65 million people worldwide, and drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) occurs in roughly 30% of cases (1, 2). DRE, which is defined as the failure to achieve long-term seizure freedom despite adequate trials of two appropriately chosen and tolerated antiepileptic drugregimens, represents a significant clinical challenge with profound impacts on quality of life, morbidity, and mortality (2, 3). The condition is associated with increased healthcare utilization and costs, reduced employment opportunities, and substantial psychosocial burden, and increased healthcare costs (4).

1.1 Clinical pathophysiology and evaluation overview of seizure-onset zones

For patients with DRE, surgical intervention often represents the most promising therapeutic option, with successful outcomes heavily dependent on accurate identification and complete resection of the seizure-onset zone (SOZ) (5). The SOZ, which is defined as the area of cortex from which clinical seizures originate, serves as the primary target for surgical intervention (6). Seizure pathophysiology in DRE varies by origin. Temporal lobe epilepsy, particularly involving mesial structures, is the most common focal epilepsy type and is often associated with hippocampal sclerosis (7). Neocortical epilepsies may arise from various regions, including frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, frequently associated with cortical dysplasias, tumors, or post-traumatic lesions (8–10). Some patients present with multifocal origins, making surgical planning particularly challenging (11).

Clinical manifestations of seizures depend on the location of the SOZ and seizure propagation pathways. Patients may experience sensory or experiential auras (olfactory, visual, déjà vu), automatisms (lip smacking, hand fumbling), altered consciousness, and various motor manifestations ranging from subtle posturing to generalized tonic–clonic activity (12, 13). These clinical features provide important clues about seizure localization but are insufficient for precise surgical planning (14).

Current diagnostic approaches for SOZ localization employ multiple complementary modalities (15). Scalp electroencephalography (EEG) provides temporal information about seizure activity but has limited spatial resolution and reduced sensitivity to deep brain structures (16, 17). Invasive recordings through stereo electroencephalography (SEEG) (depth electrodes) or electrocorticography (ECoG) (subdural grids and strips) offer superior spatial resolution but involve surgical risks and sample only limited brain regions (18). Furthermore, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify epileptogenic lesions but fails to reveal any lesion in up to 30% of the cases (19). Additionally, functional neuroimaging techniques include magnetoencephalography (MEG) (measuring magnetic fields generated by neuronal activity), positron emission tomography (identifying hypometabolic regions), and functional MRI (mapping brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow) (20–22). Despite such multimodal approaches, traditional visual analysis of these diagnostic modalities is time-consuming, requires substantial expertise, and can be subject to inter-reader variability (23). Moreover, the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of epileptic networks often make precise SOZ localization challenging, potentially leading to suboptimal surgical outcomes (24).

1.2 Machine learning applications in seizure-onset zone prediction

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising tool for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of SOZ prediction (25). Recent advances in ML algorithms, particularly deep learning architectures, have demonstrated a remarkable ability to detect subtle patterns and relationships in complex neurophysiological data (26). These computational approaches offer the potential for automated, objective, and potentially more accurate SOZ identification than traditional methods (25).

ML methods explored in the context of epilepsy management range from traditional supervised learning approaches to advanced deep learning architectures (27). Traditional methods include support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and logistic regression (LR), which typically rely on manually extracted features from neurophysiological data (28). Deep learning approaches, such as convolutional neural network (CNN) and recurrent neural network (RNN), can automatically learn hierarchical features from raw data, potentially capturing complex spatiotemporal patterns characteristic of epileptic activity (29). The application of ML across different diagnostic modalities offers unique advantages. EEG-based ML models leverage the high temporal resolution of electrophysiological recordings to detect transient epileptiform patterns (30–34). SEEG-based approaches benefit from direct recordings of deep brain structures with reduced artifact contamination (35). Moreover, MRI-based models can identify subtle structural abnormalities not apparent on visual inspection (36, 37). Multimodal approaches aim to integrate complementary information across modalities, potentially overcoming the limitations of single-modality analysis (38).

Various ML applications in epilepsy have shown encouraging results, from automated seizure detection to the prediction of surgical outcomes (39). Specifically, in SOZ prediction, ML approaches have demonstrated the ability to integrate multiple data modalities and extract relevant features that might not be apparent through conventional analysis (40). Despite these advances, several critical gaps remain in our understanding of ML applications for SOZ prediction in DRE. The relative performance of different ML approaches has not been systematically evaluated across diverse patient populations. The optimal combination of input features and algorithmic architectures also remains unclear. Moreover, the clinical validation and implementation of these methods in real-world settings require further investigation. A comprehensive systematic review of ML approaches for SOZ prediction is, therefore, timely and necessary to guide both technical development and clinical application. Such analysis could inform the development of more accurate and reliable SOZ prediction methods, potentially improving surgical outcomes and ultimately the lives of patients with DRE.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

The systematic review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (41), with a prospectively developed study protocol (PSP) guiding the objectives, search strategy, and planned analyses. As this was a systematic review of primary studies, ethical approval was not required. We aimed to explore the application of ML for predicting SOZ in patients with DRE. Moreover, we also aimed to compare the performance metric values of the ML algorithms used. The literature search, study selection, methodological quality assessment, and synthesis of results were undertaken by AHB and authenticated by AS.

The literature search was carried out through PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), and Epistemonikos in accordance with the PSP. The reference lists of the included studies were also searched for relevant publications. The search strategy included the terms “seizure-onset zone,” “electroencephalography” [MeSH Terms], and “machine learning” [MeSH Terms]. A detailed version of the strategy is provided in the Supplementary material.

2.2 Study selection

The cohort of eligible articles was reviewed by evaluating the abstracts and full texts, as required. Studies were included if they met the predetermined inclusion criteria: (1) studies that adopted ML algorithms for predicting the SOZ in patients with DRE; (2) original research articles published in peer-reviewed journals; and (3) published from database inception until August 19, 2024. Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not use ML algorithms for SOZ prediction; (2) focused on patient populations other than patients with DRE or included mixed patient populations where epilepsy data could not be separately extracted; (3) lacked methodological descriptions or contained insufficient data to assess the ML approach; or (4) were review articles, editorials, conference abstracts, or letters to the editor. The updated PRISMA flow diagram was adopted to represent the study selection process transparently.

Manual extraction of the required data, in accordance with the predetermined “Characteristics of studies” table, was carried out. The extracted variables included the author and year, study design, and datasets used. The number of patients, along with age and percentage of the female population, were also extracted. Moreover, the methods of data acquisition, algorithmic models used, and the reported performance metrics values were also collected.

2.3 Quality assessment and risk of bias

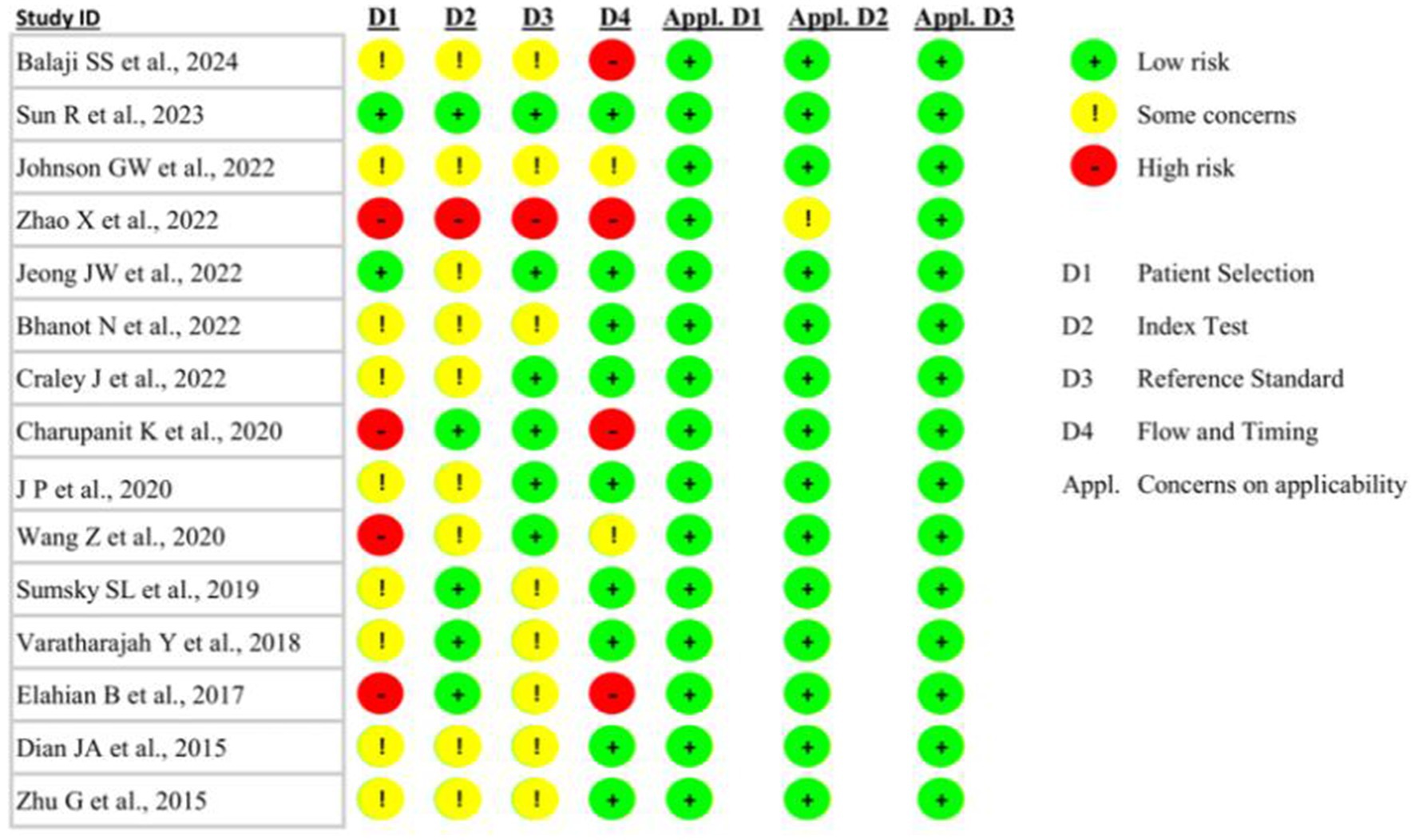

Using the Cochrane Review Manager (version 5.4.1), the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies version 2 (QUADAS-2) tool was adopted to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies (42). The QUADAS-2 analysis enabled the assessment of the overall risk of bias, which was stratified into four domains: (1) description of methods of patient selection (patient selection); (2) conduction and interpretation of the index test (index test); (3) description of the reference standard (reference standard); (4) description of the patients excluded from test induction and of the interval, as well as any interventions, between index tests and the reference standard (flow and timing) (42).

2.4 Statistical analysis

An exploratory data analysis was performed. The categorical variables were expressed as percentages of the total. The MedCalc statistical software (v. 20.215) was used to perform the analyses.

3 Results

A systematic search of PubMed/MEDLINE, CDSR, and Epistemonikos identified 38 articles. After screening abstracts and full texts, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Table 1) (43–57). The details of the excluded studies are provided in the Supplementary material, and the reasons for exclusion are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies exploring machine learning for predicting seizure-onset zone(s) in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart illustrating the search, selection, and inclusion of studies exploring machine learning for predicting seizure-onset zone(s) in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

3.1 General patient demographics and characteristics of studies

All included studies were retrospective, published between 2015 and 2024, and included a total of 352 patients (mean age 28 ± 10.7 years; 34% female population) (44–50, 53–56). Most studies were conducted in the United States (60%, n = 9) (43–45, 47, 49, 50, 53–55). In addition, 73% (n = 11) of the studies did not report the specific surgical intervention type at the individual patient level (43, 47–49, 51–57), whereas 27% (n = 4) of the studies included only Engel/ILAE class I patients (43, 44, 47, 52) and 20% (n = 3) of the studies did not report postoperative outcomes (48, 49, 57). Neurostimulation was reported in only 13% (n = 2) of the studies (45, 50).

3.2 Quality assessment and risk of bias

Upon implementing the QUADAS-2 tool to assess the risk of bias in the methodology and applicability of the included studies, 13% (n = 2) of the studies were found to have a low risk of bias in the patient selection domain (44, 47) (Figure 2). The study by Zhao et al. had a high risk of bias across all four domains (46), whereas 27% (n = 4) of the studies were found to have a high risk of bias in the “Flow and Timing” domain, specifically regarding whether all patients received the same reference standard and whether there was an appropriate interval between the index test and reference standard (43, 46, 50, 55) (Figure 2). With the exception of a single study, which exhibited an unclear concern for the applicability of the diagnostic test under evaluation (the “index test”) (46), all other studies were found to have a low risk of concern across all three applicability domains (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies—version 2 (QUADAS-2) analysis of the included studies exploring machine learning for predicting seizure-onset zone(s) in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

3.3 Datasets and methods of data acquisition

Only 20% (n = 3) of the studies adopted publicly available datasets (43, 51, 57) (Table 1). Overall, 80% (n = 12) of the studies used private datasets, and 40% (n = 6) of the studies shared their dataset as an in-manuscript table (45, 46, 48, 50, 53, 55). EEG was found to be the most common source of data acquisition, adopted by 87% (n = 13) of the studies (43, 44, 46–51, 53–57). Moreover, SEEG was adopted by 20% (n = 3) of the studies (43, 45, 52), whereas ECoG (43, 55) and MEG (44, 48) were adopted by 13% (n = 2) of the studies each (Table 1).

3.4 Algorithmic models

The included studies investigated a wide range of ML approaches, from conventional supervised learning methods to sophisticated deep learning (DL) architectures for predicting the SOZ in patients with DRE (Table 2).

Table 2. Algorithmic architecture and prediction performance reported by studies exploring machine learning for predicting seizure-onset zone(s) in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

3.4.1 Traditional machine learning methods

SVMs were widely applied and showed strong performance (43, 53, 54, 56). Root mean square (RMS) and adaptive discriminant analysis (ADA) algorithms were the primary focus of the study by Charupanit et al. (50). An LR with phase-locking value (PLV) properties was used by Elahian et al. (55).

3.4.2 Neural network-based approaches

A modified multiscale-1D-ResNet CNN was utilized by Johnson et al. to analyze the SEEG data (45). Zhao et al. investigated one-dimensional CNNs with specific loss functions [class-balanced (CB) focal loss, cross-entropy (CE)], and various data augmentation methods [EEGAug, synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE), adaptive synthetic (ADASYN)] (46). Prasanna et al. incorporated entropy measurements and the fast Walsh–Hadamard transform (FWHT) approach to train an artificial neural network (ANN) classifier (51). Cross-frequency coupling (CFC) and mutual information (MI) comodulograms were implemented in the design of the CNN by Wang et al. (52).

3.4.3 Advanced and hybrid models

Effective connectivity (EC) metrics were utilized by Balaji et al. to integrate SVM with graph feature-based models and multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) (43). With both generic and personalized variants, Sun et al. introduced the DeepSIF framework, which leveraged deep neural networks trained on neural mass models (44). The RUSBoost algorithm with varied characteristics, including short-term prediction error (STPE), generalized STPE (GSTPE), and short-term mean (STM), was employed by Bhanot et al. (48).

3.4.4 Comparative studies

Several algorithms, including multiscale residual neural network (msResNet), ResNet, CNN, MLP, k-nearest neighbors (KNN), RF, and LR, were compared by Jeong et al. (47). SZTrack (a CNN–RNN hybrid), CNN–bidirectional long short-term memory (BLSTM), temporal graph convolutional network (TGCN), deep graph convolutional network (GCN), shallow GCN, Wei-CNN, and CNN-2D9 were among the DL models that Craley et al. presented a thorough comparison of (49). Zhu et al. conducted a comparative study of K-means, SVM, and multiscale K-means (MSK-means) algorithms with directed phase envelope (DPE) (57).

3.5 Prediction performance

3.5.1 Traditional machine learning methods

Traditional ML methods achieved strong but variable results (Table 2). High sensitivity was observed by Charupanit et al. for their classification methods. Using the receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis, the anomalous high-frequency activity (aHFA) amplitude demonstrated a mean sensitivity of 93.7% for individual subject categorization, whereas the conventional high-frequency oscillation (cHFO) amplitude attained a slightly higher mean sensitivity of 94.1% (50). The cHFO rate metric mean sensitivity was 84.9%, which was still remarkable. Impressive area under the curve (AUC) values were reported by the study for both group-level and individual subject classifications. Individual subject classification yielded mean AUCs of 0.960 (aHFA amplitude), 0.948 (cHFO amplitude), and 0.905 (cHFO rate). Group-level, channel-based ROC analysis showed similar AUC values: 0.956 (cHFO rate), 0.952 (aHFA amplitude), and 0.911 (cHFO amplitude). These high AUC values indicated strong discriminative potential in differentiating between non-SOZ and SOZ channels, especially for amplitude-based measures (50). Varatharajah et al. reported their combined biomarker approach to have a specificity of approximately 75%, based on a threshold selection false-positive rate (FPR) of 25% (54). The non-linear SVM model with the radial basis function (RBF) kernel yielded an AUC of 0.79, far surpassing both the linear SVM (AUC: 0.57) and unsupervised techniques (AUC: 0.56–0.62). Under a 10-fold cross-validation (CV), the combined biomarker method maintained this AUC of 0.79, while the phase-amplitude coupling biomarker alone achieved an AUC of 0.74. Interestingly, compared to individual biomarkers, the combined biomarkers increased or maintained AUC for over 65% of patients, indicating the consistency of this strategy across a range of patient populations (54).

Additionally, a rank-based SVM algorithm for SOZ prediction was proposed by Sumsky et al. The proposed approach achieved a remarkable AUC of 0.94 across all patients (53). Class I patients performed especially well, with AUC values ranging from 0.86 to 0.94, whereas class >I patients reached AUC values between 0.71 and 0.90. Notably, both the rate-based SVM and the rank-based LR models were considerably outperformed by the rank-based SVM (p < 0.005) (53). In window-based analysis, the approach performed well, consistently maintaining an average AUC of 0.94 for 30-min windows, consistently above 0.90.

When applied to seizure-free patients, Elahian et al. found that their model had an overall accuracy of 83% (55). Additionally, they reported that their approach had a high sensitivity for locating SOZ electrodes in the resected area for patients who were seizure-free. With a low FPR of 3.7, 96% (52 out of 54) of the algorithmically determined SOZ (aSOZ) electrodes for these patients were located inside the resected region. Additionally, in seizure-free individuals, the algorithm demonstrated a 59.6% sensitivity in identifying visually recognized SOZ (vSOZ) electrodes as aSOZ (55). Dian et al. reported the combined low-frequency oscillation (LFO) + high-frequency oscillation (HFO) classifier outperforming the individual LFO- and HFO-based classifiers in terms of sensitivity and specificity (56).

By contrast, Zhu et al. employed an MSK-means classifier in conjunction with their directed phase lag entropy (DPLE) measure to attain even greater accuracy (57). Their best classification performance values, utilizing a large dataset of 4,500 × 50 dimensional DPLE characteristics, demonstrated a maximum accuracy of 93% (57).

3.5.2 Neural network-based approaches

Neural networks, particularly DL models, have yielded promising results (Table 2). These techniques, which range from CNNs to more intricate structures such as ResNet, have shown encouraging outcomes. Johnson et al. reported that their DL model classified SOZ with a sensitivity of 78.1% (95% CI 67.8–88.4%) and a specificity of 74.6% (95% CI 68.7–80.5%) (45). A Youden Index (YI) of 52.7 (95% CI 43.7–61.8) was determined by the study, showing a performance that was balanced between sensitivity and specificity. This index did not vary throughout the course of the various time periods; for example, the YI for the 0–350 ms window was 52.5 (95% CI 42.1–62.9). With a 91.5% (95% CI 89.7–93.3%) sensitivity for ipsilateral SOZ prediction, the model exhibited especially high sensitivity for unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Performance differed for various forms of epilepsy: neocortical temporal SOZs achieved a sensitivity of 64.4%, whereas bilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy showed sensitivities of 68.9 and 67.9% for left and right mesial temporal SOZs, respectively (45).

A variety of data augmentation techniques were investigated by Zhao et al. reporting a range of patient performance indicators (46). Their accuracy ranged roughly from 85 to 99% and demonstrated the potential of data augmentation techniques in improving model performance. The data augmentation techniques (EEGAug, SMOTE, ADASYN) yielded a broad range of recall values across the patients, falling in the range of 30–90% (46). Although sensitivity significantly varied among individuals, specificity remained consistently high, ranging from 90 to 99%. The observed variation in sensitivity and accuracy among patients implies that the efficacy of these techniques might depend on the unique attributes of each patient or the quality of the data (46).

The results for the msResNet model, which demonstrated remarkable accuracy in both the model and validation cohorts, were reported by Jeong et al. (47). Using 5-fold CV, the model cohort achieved 96 and 99% accuracy on the test set and training set, respectively. In that sample, the model exhibited high sensitivity, scoring 92% for lesional MRI patients and 91% for non-lesional MRI patients. The accuracy was 94% for non-lesional MRI patients and 97% for patients with lesional MRI (47). The performance was reduced in the validation group, with a balanced accuracy of 75% for patients with lesional MRI and 67% for non-lesional MRI patients. However, in this sample, sensitivity dropped to 56% for non-lesional MRI patients and 64% for lesional MRI patients, suggesting a potential challenge in generalizability (47). Additionally, the msResNet model exhibited excellent specificity for both MRI modalities and cohorts. Specificity in the model cohort was very good, with values of 98% for lesional MRI patients and 96% for non-lesional MRI patients. The specificity remained robust at 85% for lesional MRI patients and 78% for non-lesional MRI patients even in the validation sample, where overall performance declined, demonstrating the model’s high capacity to accurately detect non-SOZ areas (47). Additionally, the study provided AUC values for their suggested MRI marker (μi) in conjunction with iEEG signals (47). This combination increased AUC from 0.56–0.62 (iEEG alone) to 0.64–0.65 (non-lesional MRI group), which represents a 5–15% improvement. Nevertheless, the combination did not show improvement in the lesional MRI group; the AUC for both iEEG + μi.7 and iEEG alone remained at 0.70–0.77 (47). Furthermore, it was reported that the msResNet model outperformed MLP, CNN, and ResNet18, as well as other ML approaches, with gains in overall accuracy of up to 47% for lesional MRI instances and up to 16% for non-lesional MRI cases (47). Moreover, Prasanna et al. demonstrated good accuracy using an ANN classifier with features based on entropy (51). They obtained an accuracy of 92.80% on the University of Bonn (UOB) dataset and 99.50% on the Bern–Barcelona (BB) dataset. Sensitivity values of 91% for the UOB dataset and 99.7% for the BB dataset were reported. High specificity values of 94.6 and 99.36% for the corresponding datasets accompanied these results (51). Various entropy measurements were combined into five features to obtain the optimum performance. These findings indicate that entropy-based characteristics may be used with CNNs to achieve precise SOZ prediction (51).

Further exploring the potential of neural networks, Wang et al. suggested a CNN pipeline for SOZ prediction that employed the MI comodulogram (52). Their method provided 79% specificity and 81% sensitivity. The study reported that the suggested CNN pipeline exhibited an average AUC of 0.88, which was superior to the average AUC of 0.67 obtained by the standard CFC strength-based classification technique, which had lower sensitivity (61%) and specificity (66%) (52). The five-layer fully connected network (AUC: 0.88) substantially outperformed a single-layer network (AUC: 0.54), further demonstrating the significance of network architecture in the study. These findings demonstrate how cutting-edge CNN architectures and novel feature representations may enhance the precision of SOZ prediction (52).

3.5.3 Advanced and hybrid models

The field of SOZ prediction has advanced significantly as a result of the development of complex and hybrid models (Table 2). These innovative methods integrated methodologies from ML, signal processing, and information theory. By leveraging approaches including MI quantification, directed information (DI) analysis, and frequency-domain feature extraction, these models offered enhanced capabilities for interpreting the intricate patterns of epileptic activity. Furthermore, the development of customized DL architectures represents a significant advance toward patient-specific analysis. It has been found that advanced and hybrid models, which include MI, DI, and frequency-domain characteristics, perform exceptionally well in tasks related to localizing seizures. High-performance metrics were reported by Balaji et al. for their three EC measure-based approaches (43). Using an MLP classifier with 10% sparsity, the DI-based features obtained 92.12% accuracy, with 85.3% sensitivity and 92.8% specificity. Using an SVM with an RBF kernel at 90% sparsity, the Mutual Information-Guided Granger Causality Index (MI-GCI)-based features demonstrated the greatest specificity of 96.32% and the highest sensitivity of 89.74%. The maximum accuracy was reported at 95.72% (43). With an accuracy of 94.10% using an SVM with an RBF kernel at 10% sparsity, the frequency-domain convergent cross-mapping (FD-CCM)-based features also performed well; they reached a sensitivity of 92.3% and a specificity of 94.25%. The study notably revealed remarkable AUC values for each of the three measures: the AUC for features based on DI was 0.89, that of MI-GCI-based features was 0.9, and that of FD-CCM-based features was the highest at 0.93 (43).

Further advancing the field of hybrid models, Sun et al. presented a customized DL method for SOZ prediction (44). When compared to the generic DeepSIF (GDeepSIF), their personalized DeepSIF (PDeepSIF) model exhibited better sensitivity metrics. With a sublobar sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 99%, PDeepSIF outperformed GDeepSIF, which achieved only a sublobar sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 97%. Alongside this sensitivity improvement, there was a notable rise in the sublobar concordance rate, which increased from 83 to 93% (44). Adopting PDeepSIF was reported to significantly reduce both localization error (LE) and spatial dispersion (SD). PDeepSIF achieved 15.78 ± 5.53 mm for LE, whereas GDeepSIF achieved 24.86 ± 10.40 mm. With an SD of 8.19 ± 8.14 mm, PDeepSIF significantly outperformed GDeepSIF, which had a score of 21.90 ± 19.03 mm (44). Furthermore, PDeepSIF outperformed traditional methods such as LCMV, sLORETA, and CMEM in both metrics. Conventional techniques yielded LE of 25.94 ± 7.07 mm (LCMV), 22.89 ± 6.14 mm (sLORETA), and 31.35 ± 15.86 mm (CMEM). Moreover, conventional techniques showed much higher SD values than PDeepSIF: 33.27 ± 16.19 mm (LCMV), 29.10 ± 14.66 mm (sLORETA), and 29.15 ± 18.66 mm (CMEM) (44). These findings, which exhibited better accuracy and precision than both generic models and traditional techniques, demonstrate the promise of individualized DL approaches in improving SOZ prediction performance.

Similarly, Bhanot et al. achieved remarkable findings, obtaining 93.4% accuracy in whole-head SOZ prediction (48). Their model exhibited 93% specificity and 93% sensitivity. The study produced outstanding AUC values, demonstrating significant discriminative ability of the algorithm even with strongly skewed data, with an AUC of 0.97 for whole-head SOZ prediction and a minimum AUC of 0.95 across all areas for epileptogenic lobe localization (48). Along with the high AUC scores, these balanced sensitivity and specificity values indicated robust performance in differentiating between the ictal and interictal phases. Furthermore, they demonstrated high accuracy in region-specific classifications of epileptogenic lobe localization, underscoring the potential of sophisticated models for accurate SOZ prediction. Moreover, Craley et al. evaluated their SZTrack model on two datasets (49). SZTrack obtained a sensitivity of 83.5% at the seizure level for SOZ prediction on the JHH dataset, which was marginally less than the best-performing baseline (CNN-BLSTM) at 91.9%. The sensitivity for SOZ prediction dropped to 63.9% on the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UWM) dataset, which was used to assess generalization, although it was still higher than the CNN-BLSTM baseline (52.3%) (49). For lateralization, SZTrack outperformed other baselines with a maximum average accuracy of 82.6%, and it achieved an average accuracy of 58.7% in lobe classification, which was slightly lower than 60.5% for the top-performing TGCN. Notably, in 58.8% of patients in the JHH dataset, the model correctly recognized both the hemisphere and the lobe; in the remaining cases, the model correctly identified either the hemisphere or the lobe (49). With promising generalization capabilities, the results demonstrated the potential of SZTrack in SOZ prediction.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overview of machine learning approaches for seizure-onset zone prediction

This systematic review evaluated 15 studies investigating ML approaches for SOZ prediction in patients with DRE. The findings demonstrated considerable heterogeneity in methodological approaches and performance metrics. The wide variety of methods illustrated both the complexity of the problem and the continuous quest for the best prediction models in this field. Although the usage of classical approaches continued to demonstrate their usefulness in some circumstances, the trend toward DL and hybrid models indicates a move toward capturing more complex patterns in the data. Traditional ML methods, particularly SVM-based approaches, exhibited consistent performance with AUC values ranging from 0.79 to 0.94 (Table 2). Among these, rank-based methods demonstrated particular promise. Sumsky et al. reported that their rank-based SVM algorithm achieved superior AUC values, especially for class I patients (53). These findings suggest that rank-based methods have the potential to increase the accuracy of SOZ prediction. This insight is particularly valuable, as it may help in developing more refined models for patients with a higher likelihood of surgical success (58).

However, it is important to note that although traditional ML methods have shown good performance, the trend in recent years has been toward more complex models. Neural network-based techniques, especially DL models such as CNNs and ResNets, have emerged as effective tools, frequently surpassing conventional approaches (59). High AUC, sensitivity, and accuracy scores have been demonstrated by these models; some studies have reported performance values for these measures that are higher than 0.9 (Table 2). The resilience of DL models has been shown in their notable consistency in performance across various types of epilepsy and temporal scales (60). Furthermore, advanced and hybrid models that integrate concepts from information theory, signal processing, and ML have demonstrated significant promise (61). Methods incorporating MI, DI, and frequency-domain characteristics have shown high values for AUC, sensitivity, and accuracy, frequently above 0.9 (Table 2).

Moreover, studies have also shown that individualized DL architectures are a promising approach, demonstrating notable improvements in SD, accuracy, and localization errors compared with generic models and conventional approaches (Table 2). The evidence as a whole indicates that advanced neural network-based techniques and hybrid models that incorporate novel feature representations and patient-specific architectures hold the greatest promise for precise and reliable SOZ prediction in patients with DRE, even though reported performance varied across studies and methodologies. Notably, personalized approaches, such as PDeepSIF, demonstrated marked improvements over generic models, particularly in reducing localization error and spatial dispersion (Table 2).

4.2 Comparative performance analysis of algorithmic modeling approaches

The high-performance metrics reported by Balaji et al. for their EC measure-based approaches are particularly noteworthy (43). These methods demonstrated strong discriminative power in differentiating between SOZ and non-SOZ electrodes. The combination of high AUC values with good sensitivity and specificity metrics suggests that EC-based features may be particularly effective for SOZ prediction. This finding underscores the potential of incorporating connectivity measures into ML models for epilepsy, as they may capture important network-level information relevant to seizure onset (62). However, it is important to note that these results were obtained from a specific dataset and context, and further validation in diverse patient populations and epilepsy types is necessary to establish the generalizability of these approaches.

The comparative analysis of ML approaches revealed several important patterns. DL architectures generally outperformed traditional ML methods, particularly in handling complex, multimodal data (Table 2). However, this superior performance often came at the cost of increased computational complexity and reduced interpretability (63). Performance metrics varied significantly across studies, with sensitivity varying from 56 to 99.7% and specificity from 74.6 to 99.36% (Table 2). This variability could be potentially influenced by clinical heterogeneity driven by several factors, including but not limited to dataset size, data acquisition methods, feature selection approaches, and patient characteristics (64). Notably, studies utilizing SEEG data typically achieved higher accuracy than those using standard EEG, suggesting the importance of data quality and spatial resolution (65).

4.3 Clinical translation challenges

Our findings both reinforced and expanded upon the findings of the previous reviews in this field. Although earlier studies have demonstrated the potential of ML in epilepsy management (39, 66), our review specifically highlighted the evolution toward more sophisticated, hybrid approaches that combine multiple data modalities and learning architectures. The superior performance of personalized models, particularly in reducing localization error, represents a novel insight not previously emphasized in the literature. However, our findings regarding the impact of data quality and quantity on model performance align with previous observations in the context of medical ML applications (67).

These findings have substantial clinical implications but face implementation challenges. Despite promising accuracy improvements, integrating ML approaches into clinical workflows requires careful consideration of several factors. The requirement for high-quality, standardized data acquisition poses logistical and resource challenges. Moreover, dataset imbalance represents a significant technical hurdle (68), as SOZ regions typically constitute a small fraction of recorded channels and brain volume, potentially biasing algorithms toward high specificity at the expense of sensitivity. Furthermore, the interpretability of complex ML models, particularly deep neural networks, remains limited, creating a “black box” problem that may reduce clinician trust and adoption. The need for computational expertise and infrastructure may also limit adoption in clinical settings, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of implementing these systems, particularly more complex DL architectures, warrants careful evaluation against contemporary standard practices, considering not only software and hardware requirements but also personnel training, maintenance costs, and potential savings from improved surgical outcomes. Generalizability across diverse healthcare settings with varying resources and expertise also remains a critical concern for widespread clinical implementation.

Furthermore, an important consideration in evaluating the clinical utility of SOZ prediction methods is the long-term postoperative course and seizure recurrence patterns. Although some patients may experience immediate and sustained seizure freedom following surgical intervention, a subgroup of patients may experience seizure recurrence after a variable interval ranging from months to years (69). In such cases, the recurrent seizures may have an identical or similar semiology, suggesting that the initial intervention did not effectively treat the SOZ due to insufficient or inaccurate localization (70). Additionally, some patients may have multiple SOZs, leading to the recurrence of seizures with a different semiology after the initial intervention (71). These observations highlight the importance of accurate and comprehensive SOZ localization. Furthermore, it is important to note that the included studies varied in their length of postoperative follow-up, with 87% (n = 13) of studies not specifying the length of follow-up (43, 44, 46–49, 51–57) (Table 1). Given the potential for seizure recurrence over longer periods, studies with longer follow-up intervals, such as Zhao et al. may provide more reliable insights into the long-term clinical utility of the investigated SOZ prediction methods (46).

4.4 Methodological considerations and ground truth challenges

The heterogeneity in data acquisition methods across included studies introduces potential biases and complicates direct comparisons of results. This variability, combined with selection biases in patient populations and inconsistent reporting protocols, underscores the urgent need for standardized data collection and processing methods (72). Moreover, the divergence in the definition and validation of outcome measures was recognized as a critical challenge in evaluating ML approaches for SOZ prediction. To address these limitations, we recommend the development of standardized benchmarking protocols, including common performance metrics and validation datasets, to facilitate meaningful comparisons across studies and enhance clinical applicability (73).

A fundamental challenge in evaluating ML approaches for SOZ prediction is the definition and reliability of “ground truth” labels adopted for algorithmic model training and validation. Clinically determined SOZ labels are inherently subject to interobserver variability, limitations in sampling coverage, and interpretative biases. This creates a circular problem: ML models trained on potentially imperfect clinical labels may perpetuate rather than overcome existing limitations in SOZ identification. The ultimate validation metric should, thus, be long-term seizure freedom following surgical resection of the algorithm-identified regions, as this represents the true clinical goal of SOZ prediction. However, only 27% (n = 4) of studies explicitly included Engel/ILAE class I patients in their analysis, and 87% (n = 13) of studies did not specify follow-up duration. This highlights a critical gap between technical performance metrics and clinically meaningful outcomes. We, therefore, suggest that seizure freedom for at least 2 years should be considered the gold standard for validating ML predictions, as early surgical success may not translate to sustained seizure control (69, 74). Moreover, successful surgical outcomes may result not only from accurate SOZ localization but also from the disconnection of seizure circuits through peri-SOZ white matter resection (75, 76). This distinction is important when evaluating ML performance, as algorithms trained solely on SOZ identification may not capture the full complexity of successful surgical intervention.

4.5 Network-level considerations in seizure-onset zone prediction

It should also be noted that the role of neural networks in epilepsy extends beyond the immediate SOZ, involving complex interactions across distributed brain regions that may be crucial for both seizure generation and propagation (77, 78). Epilepsy can lead to widespread alterations in both structural and functional connectivity, affecting multiple brain networks, including the default mode, salience, and attention networks (79, 80). These network-level changes may persist even after successful surgical intervention, highlighting the dynamic nature of epilepsy-related brain plasticity (81). In temporal lobe epilepsy, for instance, studies have demonstrated alterations in hippocampal-cortical networks that extend well beyond the temporal lobe, with implications for cognitive function and surgical outcomes (82, 83). Post-surgical network reorganization has been observed, with some patients showing normalization of previously disrupted networks, while others demonstrate persistent alterations that may contribute to seizure recurrence (81, 84). Understanding these network-level changes is particularly relevant for ML approaches to SOZ prediction, as successful surgical outcomes depend on both the accurate identification of the epileptogenic zone and an understanding of its relationship with broader network dynamics (85). This network perspective is especially crucial in complex epilepsies, where multiple nodes within a network may contribute to seizure generation and propagation (86). Future ML approaches will, therefore, benefit from incorporating these network-level considerations, potentially through the integration of functional connectivity metrics and longitudinal network analysis in their predictive models (87, 88).

4.6 Future research directions

Future research directions should address several other key areas. Larger, prospective studies are needed to validate the performance of promising ML approaches, particularly personalized models. The standardization of data acquisition and preprocessing methods would facilitate more meaningful comparisons between approaches. Investigation of model interpretability and validation of ML-derived predictions against surgical outcomes are crucial. Technical developments should focus on improving computational efficiency, reducing the need for extensive preprocessing, and developing more robust approaches for handling limited and ‘noisy’ data. Evaluating multiple ML algorithms on a uniform, well-curated dataset with standardized performance metrics and long-term (≥1–2 years) seizure freedom validation would provide insights into their relative strengths and limitations, helping establish evidence-based guidelines for clinical algorithm selection.

To facilitate clinical integration, a structured implementation framework is proposed. Prospective multicenter validation studies should include both academic epilepsy centers and community hospitals to reflect diverse clinical environments. Developing explainable artificial intelligence techniques specific to SOZ prediction is also essential for fostering clinician trust, potentially through visualization tools that highlight regions of interest in a clinically interpretable manner. Moreover, practical implementation requires user-friendly software interfaces that seamlessly integrate with existing clinical workflows and electronic health records, presenting ML predictions alongside traditional clinical data (Figure 3). Furthermore, establishing clear regulatory pathways for ML-based decision support tools will ensure appropriate validation standards and facilitate adoption in epilepsy surgery planning.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework outlining the pipeline for optimized seizure-onset zone(s) prediction using machine learning in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Future studies should also focus on direct comparisons between ML-enhanced non-invasive methods and current invasive standards of care. If ML approaches can demonstrate comparable or superior accuracy using non-invasive data, this could represent a significant advancement in presurgical evaluation for epilepsy, potentially reducing the need for invasive procedures in some patients. However, until such superiority is conclusively demonstrated, the results of these predominantly EEG-based ML studies should be interpreted cautiously in the context of current clinical practice. Future research should also prioritize the development and validation of ML models specifically designed to assist in SOZ prediction for complex clinical cases with more than one potential epileptogenic zone, as this is where the potential clinical impact could be most significant. EC-based methods should be explored in such complex epilepsy cases and compared to other advanced ML techniques in larger, prospective studies.

Beyond conventional approaches, several innovative directions also warrant exploration. Federated learning represents a promising paradigm that could enable collaborative model development across multiple epilepsy centers without transferring sensitive patient data, addressing both privacy concerns and the challenge of limited dataset sizes at individual institutions. The integration of multimodal data beyond neurophysiological recordings, including genomics, proteomics, and detailed neuropsychological profiles, could enhance algorithmic model performance by capturing and better accounting for the biological mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Furthermore, ML approaches could expand beyond SOZ prediction for predicting outcomes stratified for different intervention types such as resection, ablation, and neurostimulation, potentially enabling treatment selection. Moreover, novel self-supervised learning techniques might reduce reliance on labeled data, addressing the ground truth challenges inherent in SOZ determination. In addition to this, the development of adaptive ML systems that incorporate post-surgical outcomes and network reorganization data could lead to continuously improving algorithmic models that account for the dynamic nature of epileptic networks over time.

Advanced multimodal fusion techniques deserve particular attention, focusing on developing sophisticated methods that synchronize and integrate data across temporal and spatial scales, such as combining high-temporal-resolution EEG with high-spatial-resolution imaging. Wearable and minimally invasive devices coupled with ML algorithms represent another promising frontier, potentially enabling continuous monitoring of seizure dynamics in real-world settings and providing unprecedented longitudinal data for model refinement. Patient-specific forecasting models that predict not only SOZ location but also seizure probability and management response could potentially transform epilepsy management by enabling dynamic management adjustments based on individual seizure patterns and neural network states. Additionally, developing ML approaches that distinguish between the SOZ and symptomatogenic zone could further provide more comprehensive guidance for surgical planning, potentially improving both seizure control and functional outcomes.

4.7 Limitations

This systematic review has several methodological strengths, including comprehensive database searching, rigorous inclusion criteria, and systematic quality assessment using QUADAS-2. However, important limitations must be acknowledged. The heterogeneity in reporting standards and performance metrics complicates direct comparisons between studies. Dataset heterogeneity was also substantial, with variations in patient demographics, epilepsy types, and recording parameters across included studies. The predominance of retrospective designs and relatively small patient cohorts in many studies may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The mean sample size was only 23 patients, with many studies including fewer than 15 subjects, increasing the risk of overfitting and limiting statistical power. Additionally, publication bias favoring positive results cannot be excluded. This bias may be particularly pronounced in ML research, where negative results or underperforming models are substantially less likely to be published. In addition to these, the preponderance of EEG-based studies in this systematic review raises an important question about the selective potential of ML approaches to enhance non-invasive SOZ prediction methods only. Although these non-invasive techniques offer advantages in terms of patient comfort and reduced procedural risks, their ability to match or exceed the precision of intracranial monitoring remains a critical area of investigation (89).

The high adoption rate of EEG in ML studies may reflect its widespread availability and ease of data collection, rather than its superiority for SOZ prediction. Furthermore, a significant limitation identified in our review was the potentially limited clinical utility of many of the studied ML approaches for patients with more complex or difficult-to-diagnose types of epilepsy. Although several studies reported high-performance metrics, these were often in the context of more straightforward cases, such as unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. For instance, Johnson GW et al. reported high sensitivity (91.5%) for ipsilateral SOZ prediction in unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, but considerably lower sensitivity for neocortical temporal epilepsy (64.4%) and bilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (68.9 and 67.9% for left and right, respectively) (45). This pattern suggests that current ML approaches may not adequately address the challenges posed by more complex epilepsy types, which are often the cases where accurate SOZ localization is most crucial and challenging in clinical practice.

Furthermore, the scarcity of reported data prevented an analysis from being conducted to explore surgical intervention type, postoperative Engel class outcome subgroups, neurostimulation type, and neurostimulation outcomes as possible confounders to SOZ prediction performance. Moreover, substantial heterogeneity in data collection protocols and limited adoption of non-EEG methods for the collection of data prohibited a comparison of SOZ prediction performance from being made in the context of non-invasive versus invasive methods for data collection. Exploration of the probable superiority of SEEG-based data collection over subdural grids and strips, considering the superior spatial coverage of the former, could also not be undertaken.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review systematically synthesized the application of ML for SOZ prediction in patients with DRE and demonstrated that ML approaches, particularly DL architectures and personalized models, offer promising solutions for SOZ prediction. Traditional ML methods showed reliable performance, while advanced neural networks achieved superior accuracy in many cases, with some models reaching accuracy rates above 90%. The emergence of hybrid and personalized approaches represents a significant advancement, potentially offering more precise and patient-specific SOZ prediction. These developments have important clinical implications, as improved prediction accuracy could enhance surgical planning and potentially lead to better outcomes in epilepsy surgery. However, successful clinical implementation will require addressing challenges in data standardization, computational infrastructure, and clinical workflow integration. As ML technologies continue to evolve, future developments focusing on larger-scale validation, improved interpretability, and streamlined clinical integration will be crucial in realizing the full potential of these approaches for SOZ prediction in particular and epilepsy care in general.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

AB: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. MB: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. RB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation. SP: Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AS: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Trinka AI web application was used for copy-editing and sentence structure optimization. Napkin AI web application was adopted to develop Figure 3.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1687144/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Milligan, TA. Epilepsy: a clinical overview. Am J Med. (2021) 134:840–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.01.038

2. Guery, D, and Rheims, S. Clinical Management of Drug Resistant Epilepsy: a review on current strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:2229–42. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S256699

3. Jehi, L. Advances in therapy for refractory epilepsy. Annu Rev Med. (2024) 76:389–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050522-034458

4. Ben-Menachem, E, Schmitz, B, Kälviäinen, R, Thomas, RH, and Klein, P. The burden of chronic drug-refractory focal onset epilepsy: can it be prevented? Epilepsy Behav. (2023) 148:109435. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109435

5. Sabzvari, T, Aflahe Iqbal, M, Ranganatha, A, Daher, JC, Freire, I, Shamsi, SMF, et al. A comprehensive review of recent trends in surgical approaches for epilepsy management. Cureus. (2024) 16:e71715. doi: 10.7759/cureus.71715

6. Miller, KJ, and Fine, AL. Decision-making in stereotactic epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. (2022) 63:2782–801. doi: 10.1111/epi.17381

7. Dos Santos Silva, RP, Lima Angelo, ICB, De Medeiros Dantas, GC, De Souza, JM, Pinheiro Pessoa, JRC, Lopes, LG, et al. Pattern of abnormalities on gray matter in patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis: an updated meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2024) 245:108473. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2024.108473

8. Almacellas Barbanoj, A, Graham, RT, Maffei, B, Carpenter, JC, Leite, M, Hoke, J, et al. Anti-seizure gene therapy for focal cortical dysplasia. Brain J Neurol. (2024) 147:542–53. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad387

9. Maschio, M, Perversi, F, and Maialetti, A. Brain tumor-related epilepsy: an overview on neuropsychological, behavioral, and quality of life issues and assessment methodology. Front Neurol. (2024) 15:1480900. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1480900

10. Zhong, J, Lan, Y, Sun, L, Zhao, Z, Liu, X, Shi, J, et al. Global prevalence of post-traumatic epilepsy in traumatic brain injury patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (1997-2024). Neuroscience. (2025) 584:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2025.07.008

11. Zhong, C, Yang, K, Wang, N, Yang, L, Yang, Z, Xu, L, et al. Advancements in surgical therapies for drug-resistant epilepsy: a paradigm shift towards precision care. Neurol Ther. (2025) 14:467–90. doi: 10.1007/s40120-025-00710-4

12. Fine, A, and Nickels, K. Age-related semiology changes over time. Epilepsy Behav. (2025) 163:110185. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2024.110185

13. Oane, I, Barborica, A, and Mîndruţă, II. Ictal semiology in temporo-frontal epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epileptic Disord. (2025) 27:171–86. doi: 10.1002/epd2.20328

14. Khoo, A, Alim-Marvasti, A, de Tisi, J, Diehl, B, Walker, MC, Miserocchi, A, et al. Value of semiology in predicting epileptogenic zone and surgical outcome following frontal lobe epilepsy surgery. Seizure. (2023) 106:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2023.01.019

15. Balaji, SS, and Parhi, KK. Seizure onset zone identification from iEEG: a review. IEEE Access. (2022) 10:62535–47. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3182716

16. Casale, MJ, Marcuse, LV, Young, JJ, Jette, N, Panov, FE, Bender, HA, et al. The sensitivity of scalp EEG at detecting seizures-a simultaneous scalp and stereo EEG study. J Clin Neurophysiol. (2022) 39:78–84. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000739

17. Baumgartner, C, Baumgartner, J, Duarte, C, Lang, C, Lisy, T, and Koren, JP. Role of specific interictal and ictal EEG onset patterns. Epilepsy Behav. (2025) 164:110298. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2025.110298

18. Wu, S, Issa, NP, Rose, SL, Haider, HA, Nordli, DR Jr, Towle, VL, et al. Depth versus surface: a critical review of subdural and depth electrodes in intracranial electroencephalographic studies. Epilepsia. (2024) 65:1868–78. doi: 10.1111/epi.18002

19. Lemmens, MJDK, van Lanen, RHGJ, Uher, D, Colon, AJ, Hoeberigs, MC, Hoogland, G, et al. Ex vivo ultra-high field magnetic resonance imaging of human epileptogenic specimens from primarily the temporal lobe: a systematic review. Neuroradiology. (2025) 67:875–93. doi: 10.1007/s00234-024-03474-0

20. Kreidenhuber, R, Poppert, KN, Mauritz, M, Hamer, HM, Delev, D, Schnell, O, et al. MEG in MRI-negative patients with focal epilepsy. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:5746. doi: 10.3390/jcm13195746

21. Wu, H, Liao, K, Tan, Z, Zeng, C, Wu, B, Zhou, Z, et al. A PET-based radiomics nomogram for individualized predictions of seizure outcomes after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Seizure. (2024) 119:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2024.04.021

22. Boerwinkle, VL, Nowlen, MA, Vazquez, JE, Arhin, MA, Reuther, WR, Cediel, EG, et al. Resting-state fMRI seizure onset localization meta-analysis: comparing rs-fMRI to other modalities including surgical outcomes. Front Neuroimaging. (2024) 3:1481858. doi: 10.3389/fnimg.2024.1481858

23. Pan, R, Yang, C, Li, Z, Ren, J, and Duan, Y. Magnetoencephalography-based approaches to epilepsy classification. Front Neurosci. (2023) 17:1183391. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1183391

24. Samanta, D. Recent developments in stereo electroencephalography monitoring for epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. (2022) 135:108914. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2022.108914

25. Al-Hajjar, ALN, and Al-Qurabat, AKM. An overview of machine learning methods in enabling IoMT-based epileptic seizure detection. J Supercomput. (2023) 2023:1–48. doi: 10.1007/s11227-023-05299-9

26. Xu, X, Li, J, Zhu, Z, Zhao, L, Wang, H, Song, C, et al. A comprehensive review on synergy of multi-modal data and AI technologies in medical diagnosis. Bioengineering. (2024) 11:219. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11030219

27. Bai, L, Litscher, G, and Li, X. Epileptic seizure detection using machine learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci. (2025) 15:634. doi: 10.3390/brainsci15060634

28. Saeidi, M, Karwowski, W, Farahani, FV, Fiok, K, Taiar, R, Hancock, PA, et al. Neural decoding of EEG signals with machine learning: a systematic review. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:1525. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11111525

29. Wang, X, Wang, Y, Liu, D, Wang, Y, and Wang, Z. Automated recognition of epilepsy from EEG signals using a combining space-time algorithm of CNN-LSTM. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:14876. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-41537-z

30. Mallick, S, and Baths, V. Novel deep learning framework for detection of epileptic seizures using EEG signals. Front Comput Neurosci. (2024) 18:1340251. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2024.1340251

31. Sheikh, SR, McKee, ZA, Ghosn, S, Jeong, KS, Kattan, M, Burgess, RC, et al. Machine learning algorithm for predicting seizure control after temporal lobe resection using peri-ictal electroencephalography. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:21771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-72249-7

32. Pilet, J, Beardsley, SA, Carlson, C, Anderson, CT, Ustine, C, Lew, S, et al. Predicting seizure onset zones from interictal intracranial EEG using functional connectivity and machine learning. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:17801. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-02679-4

33. Daida, A, Zhang, Y, Kanai, S, Staba, R, Roychowdhury, V, and Nariai, H. AI-based localization of the epileptogenic zone using intracranial EEG. Epilepsia Open. (2025) 1–18. doi: 10.1002/epi4.70130

34. Mora, S, Turrisi, R, Chiarella, L, Consales, A, Tassi, L, Mai, R, et al. NLP-based tools for localization of the epileptogenic zone in patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:2349. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-51846-6

35. Raghu, A, Nidhin, CP, Sivabharathi, VS, Menon, PR, Sheela, P, Ajai, R, et al. Machine learning-based localization of the epileptogenic zone using high-frequency oscillations from SEEG: a real-world approach. J Clin Neurosci. (2025) 135:111177. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111177

36. Berger, M, Licandro, R, Nenning, KH, Langs, G, and Bonelli, SB. Artificial intelligence applied to epilepsy imaging: current status and future perspectives. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2025) 181:420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2025.03.006

37. Rehab, N, Siwar, Y, and Mourad, Z. Machine learning for epilepsy: a comprehensive exploration of novel EEG and MRI techniques for seizure diagnosis. J Med Biol Eng. (2024) 44:317–36. doi: 10.1007/s40846-024-00874-8

38. Qu, R, Ji, X, Wang, S, Wang, Z, Wang, L, Yang, X, et al. An integrated Multi-Channel deep neural network for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy identification using multi-modal medical data. Bioeng Basel Switz. (2023) 10:1234. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering10101234

39. Kerr, WT, and McFarlane, KN. Machine learning and artificial intelligence applications to epilepsy: a review for the practicing epileptologist. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2023) 23:869–79. doi: 10.1007/s11910-023-01318-7

40. Tajmirriahi, M, and Rabbani, H. A review of EEG-based localization of epileptic seizure foci: common points with multimodal fusion of brain data. J Med Signals Sens. (2024) 14:19. doi: 10.4103/jmss.jmss_11_24

41. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

42. Whiting, PF, Rutjes, AWS, Westwood, ME, Rutjes, AW, Mallett, S, Deeks, JJ, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009

43. Balaji, SS, and Parhi, KK. Seizure onset zone (SOZ) identification using effective brain connectivity of epileptogenic networks. J Neural Eng. (2024) 21:036053. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/ad5938

44. Sun, R, Zhang, W, Bagić, A, and He, B. Deep learning based source imaging provides strong sublobar localization of epileptogenic zone from MEG interictal spikes. NeuroImage. (2023) 281:120366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120366

45. Johnson, GW, Cai, LY, Doss, DJ, Jiang, JW, Negi, AS, Narasimhan, S, et al. Localizing seizure onset zones in surgical epilepsy with neurostimulation deep learning. J Neurosurg. (2023) 138:1002–7. doi: 10.3171/2022.8.JNS221321

46. Zhao, X, Sole-Casals, J, Sugano, H, and Tanaka, T. Seizure onset zone classification based on imbalanced iEEG with data augmentation. J Neural Eng. (2022) 19:065001. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aca04f

47. Jeong, JW, Lee, MH, Kuroda, N, Sakakura, K, O'Hara, N, Juhasz, C, et al. Multi-scale deep learning of clinically acquired multi-modal MRI improves the localization of seizure onset zone in children with drug-resistant epilepsy. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. (2022) 26:5529–39. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2022.3196330

48. Bhanot, N, Mariyappa, N, Anitha, H, Bhargava, GK, Velmurugan, J, and Sinha, S. Seizure detection and epileptogenic zone localisation on heavily skewed MEG data using RUSBoost machine learning technique. Int J Neurosci. (2022) 132:963–74. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1858828

49. Craley, J, Jouny, C, Johnson, E, Hsu, D, Ahmed, R, and Venkataraman, A. Automated seizure activity tracking and onset zone localization from scalp EEG using deep neural networks. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0264537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264537

50. Charupanit, K, Sen-Gupta, I, Lin, JJ, and Lopour, BA. Amplitude of high frequency oscillations as a biomarker of the seizure onset zone. Clin Neurophysiol. (2020) 131:2542–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.07.021

51. Prasanna, J, MSP, S, Mohammed, MA, Maashi, MS, Garcia-Zapirain, B, Sairamya, NJ, et al. Detection of focal and non-focal electroencephalogram signals using fast Walsh-Hadamard transform and artificial neural network. Sensors. (2020) 20:4952. doi: 10.3390/s20174952

52. Wang, Z, and Li, C. Classifying cross-frequency coupling pattern in epileptogenic tissues by convolutional neural network In: 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE (2020). 3440–3.

53. Sumsky, SL, and Santaniello, S. Decision support system for seizure onset zone localization based on channel ranking and high-frequency EEG activity. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. (2019) 23:1535–45. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2018.2867875

54. Varatharajah, Y, Berry, B, Cimbalnik, J, Kremen, V, van Gompel, J, Stead, M, et al. Integrating artificial intelligence with real-time intracranial EEG monitoring to automate interictal identification of seizure onset zones in focal epilepsy. J Neural Eng. (2018) 15:046035. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aac960

55. Elahian, B, Yeasin, M, Mudigoudar, B, Wheless, JW, and Babajani-Feremi, A. Identifying seizure onset zone from electrocorticographic recordings: a machine learning approach based on phase locking value. Seizure. (2017) 51:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.07.010

56. Dian, JA, Colic, S, Chinvarun, Y, Carlen, PL, and Bardakjian, BL. Identification of brain regions of interest for epilepsy surgery planning using support vector machines. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. (2015) 2015:6590–3. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319903

57. Zhu, G, Li, Y, Wen, PP, and Wang, S. Classifying epileptic EEG signals with delay permutation entropy and multi-scale K-means. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2015) 823:143–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10984-8_8

58. Woolfe, M, Prime, D, Gillinder, L, Rowlands, D, O’keefe, S, and Dionisio, S. Automatic detection of the epileptogenic zone: an application of the fingerprint of epilepsy. J Neurosci Methods. (2019) 325:108347. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2019.108347

59. Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D, Armin, MA, Hayder, Z, Garcia-Cairasco, N, Petersson, L, Fookes, C, et al. Deep learning approaches for seizure video analysis: a review. Epilepsy Behav. (2024) 154:109735. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2024.109735

60. Gabeff, V, Teijeiro, T, Zapater, M, Cammoun, L, Rheims, S, Ryvlin, P, et al. Interpreting deep learning models for epileptic seizure detection on EEG signals. Artif Intell Med. (2021) 117:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2021.102084

61. Sharma, N, Sharma, M, Singhal, A, Vyas, R, Malik, H, Afthanorhan, A, et al. Recent trends in EEG-based motor imagery signal analysis and recognition: a comprehensive review. IEEE Access. (2023) 11:80518–42. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3299497

62. Larivière, S, Bernasconi, A, Bernasconi, N, and Bernhardt, BC. Connectome biomarkers of drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2021) 62:6–24. doi: 10.1111/epi.16753

63. Zou, Z, Chen, B, Xiao, D, Tang, F, and Li, X. Accuracy of machine learning in detecting pediatric epileptic seizures: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2024) 26:e55986. doi: 10.2196/55986

64. Sone, D, and Beheshti, I. Clinical application of machine learning models for brain imaging in epilepsy: a review. Front Neurosci. (2021) 15:684825. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.684825

65. Gupta, K, Grover, P, and Abel, TJ. Current conceptual understanding of the epileptogenic network from Stereoelectroencephalography-based connectivity inferences. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:569699. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.569699

66. Smolyansky, ED, Hakeem, H, Ge, Z, Chen, Z, and Kwan, P. Machine learning models for decision support in epilepsy management: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 123:108273. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108273

67. Sirocchi, C, Bogliolo, A, and Montagna, S. Medical-informed machine learning: integrating prior knowledge into medical decision systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2024) 24:186. doi: 10.1186/s12911-024-02582-4

68. Hrtonova, V, Jaber, K, Nejedly, P, Blackwood, ER, Klimes, P, and Frauscher, B. The class imbalance problem in automatic localization of the epileptogenic zone for epilepsy surgery: a systematic review. J Neural Eng. (2025) 22:ade28c. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/ade28c

69. Petrik, S, San Antonio-Arce, V, Steinhoff, BJ, Syrbe, S, Bast, T, Scheiwe, C, et al. Epilepsy surgery: late seizure recurrence after initial complete seizure freedom. Epilepsia. (2021) 62:1092–104. doi: 10.1111/epi.16893

70. Gonzalez-Martinez, J, Bulacio, J, Alexopoulos, A, Jehi, L, Bingaman, W, and Najm, I. Stereoelectroencephalography in the “difficult to localize” refractory focal epilepsy: early experience from a north American epilepsy center. Epilepsia. (2013) 54:323–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03672.x

71. Aung, T, and Chauvel, P. Chapter 6 - what is seizure onset? Interictal, preictal/ictal patterns, and the epileptogenic zone In: P Chauvel, A McGonigal, GM McKhann II, and J González-Martínez, editors. Fundamentals of stereoelectroencephalography. St. Louis, MO United States: Elsevier (2025). 67–84.

72. Lhatoo, SD, Bernasconi, N, Blumcke, I, Braun, K, Buchhalter, J, Denaxas, S, et al. Big data in epilepsy: clinical and research considerations. Report from the epilepsy big data task force of the international league against epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:1869–83. doi: 10.1111/epi.16633

73. Kerr, WT, McFarlane, KN, and Figueiredo Pucci, G. The present and future of seizure detection, prediction, and forecasting with machine learning, including the future impact on clinical trials. Front Neurol. (2024) 15:1425490. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1425490

74. Harris, WB, Brunette-Clement, T, Wang, A, Phillips, HW, von Der Brelie, C, Weil, AG, et al. Long-term outcomes of pediatric epilepsy surgery: individual participant data and study level meta-analyses. Seizure. (2022) 101:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2022.08.010

75. Li, X, Zhang, H, Lai, H, Wang, J, Wang, W, and Yang, X. High-frequency oscillations and epileptogenic network. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2022) 20:1687–703. doi: 10.2174/1570159X19666210908165641

76. Hines, K, and Wu, C. Epilepsy networks and their surgical relevance. Brain Sci. (2023) 14:31. doi: 10.3390/brainsci14010031

77. Yang, C, Liu, Z, Wang, Q, Wang, Q, Liu, Z, and Luan, G. Epilepsy as a dynamical disorder orchestrated by epileptogenic zone: a review. Nonlinear DYN. (2021) 104:1901–16. doi: 10.1007/s11071-021-06420-4

78. Yaffe, RB, Borger, P, Megevand, P, Groppe, DM, Kramer, MA, Chu, CJ, et al. Physiology of functional and effective networks in epilepsy. Clin Neurophysiol. (2015) 126:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.09.009

79. Zhou, X, Zhang, Z, Yu, L, Fan, B, Wang, M, Jiang, B, et al. Disturbance of functional and effective connectivity of the salience network involved in attention deficits in right temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 124:108308. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108308

80. Wei, HL, An, J, Zeng, LL, Shen, H, Qiu, SJ, and Hu, DW. Altered functional connectivity among default, attention, and control networks in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2015) 46:118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.031

81. Sainburg, LE, Englot, DJ, and Morgan, VL. The impact of resective epilepsy surgery on the brain network: evidence from post-surgical imaging. Brain. (2025) 148:awaf026. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaf026

82. Cabalo, DG, DeKraker, J, Royer, J, Xie, K, Tavakol, S, Rodríguez-Cruces, R, et al. Differential reorganization of episodic and semantic memory systems in epilepsy-related mesiotemporal pathology. Brain J Neurol. (2024) 147:3918–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awae197

83. Englot, DJ, Konrad, PE, and Morgan, VL. Regional and global connectivity disturbances in focal epilepsy, related neurocognitive sequelae, and potential mechanistic underpinnings. Epilepsia. (2016) 57:1546–57. doi: 10.1111/epi.13510

84. Li, W, Jiang, Y, Qin, Y, Li, X, Lei, D, Zhang, H, et al. Altered resting state networks before and after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Brain Topogr. (2022) 35:692–701. doi: 10.1007/s10548-022-00912-1

85. Cao, M, Vogrin, SJ, Peterson, ADH, Woods, W, Cook, MJ, and Plummer, C. Dynamical network models from EEG and MEG for epilepsy surgery-a quantitative approach. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:837893. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.837893

86. Royer, J, Bernhardt, BC, Larivière, S, Gleichgerrcht, E, Vorderwülbecke, BJ, Vulliémoz, S, et al. Epilepsy and brain network hubs. Epilepsia. (2022) 63:537–50. doi: 10.1111/epi.17171

87. Akbarian, B, Sainburg, LE, Janson, A, Johnson, G, Doss, DJ, Rogers, BP, et al. Association between postsurgical functional connectivity and seizure outcome in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. (2024) 103:e209816. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209816

88. Gerster, M, Taher, H, Škoch, A, Hlinka, J, Guye, M, Bartolomei, F, et al. Patient-specific network connectivity combined with a next generation neural mass model to test clinical hypothesis of seizure propagation. Front Syst Neurosci. (2021) 15:675272. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2021.675272

Keywords: epilepsy, drug-resistant epilepsy, seizure-onset zone, machine learning, localization error

Citation: Bangash AH, Bercu MM, Byrne RW, Pavuluri S and Salehi A (2025) Application of machine learning approaches to predict seizure-onset zones in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: a systematic review. Front. Neurol. 16:1687144. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1687144

Edited by:

Andrea Bianconi, University of Genoa, ItalyReviewed by:

Amirmasoud Ahmadi, Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence, GermanyRehab Naily, Gabes University, Tunisia

Copyright © 2025 Bangash, Bercu, Byrne, Pavuluri and Salehi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Haider Bangash, YWxoYWlkZXJAbW9udGVmaW9yZS5vcmc=; Afshin Salehi, YXNhbGVoaUB1bm1jLmVkdQ==

Ali Haider Bangash